ABSTRACT

Bringing together literature from music education, posthumanism, sound studies and ethnomusicology, this article considers what sound ‘does’ in music education spaces. Within posthumanism, the role of sound, as a manifestation of material-human entanglements, is under-theorised. This article, diffractively plays with the literature and evidence from a PhD project and a listening walk with pre-service music teachers, allowing the reverberations (as the continued effects and affects of bringing these materials into contact with each other), to spark generative thinking about how sound in music education is conceived. In doing so, the article presents three reverberations that challenge humanist conceptions of sound/music in education. The first considers all sound (human and non-human) as voice, which is transindividual (Chadwick in Flint [2022]. “More-than-Human Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Listening to the Leafblower.” Qualitative Research 22 (4): 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794121999028) , the second considers the role of sound as an invitation to ‘world-with’ (Barad [2007]. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press) and the third reverberation explores sound as affect (Gallagher [2016]. “Sound as Affect: Difference, Power and Spatiality.” Emotion, Space and Society 20:42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.02.004). In thinking with these generative reverberations, this article is a provocation to explore how a posthuman reconceptualisation of sound in music education can help us re-state the importance of music as a curriculum subject.

Introduction

Music classrooms are noisy, sound-full places and therefore, the role of sound within music education may seem like a moot point, an accepted truth, an essential and therefore unquestionable element of practice. Yet, there are continuing tensions between on the one hand epistemologies of ‘knowing about’ and ‘knowing that’, which maintain individualised knowing and the Cartesian dualism of mind-body (Denmead Citation2015), and on the other, understandings of knowledge that embrace the role of the sensorium and the entangled creation of knowledge with others (including non-humans) (Taylor and Hughes Citation2016). This creates an uneasy relationship for sound in educational institutions, where its role within pedagogy, its role with bodies (human and non-human) and what it ‘does’ within learning is under-theorised. As a result, the role of sound in classrooms can be downplayed (BBC Citation2012) or conceptualised as a ‘tool’ through which knowledge about or knowledge can be reinforced (Cooke Citation2021). In doing so, whether sound is present or not, can be perceived as immaterial, where the learning can proceed without sound, through language and text, and where the sound is incorporated it is separate and abstracted from the learner. This leads to fundamental questions about the justification of sound work within the curriculum.

Drawing on my PhD and ongoing writings about posthumanism, this paper will argue, that re-hearing the role of sound through posthumanism, allows us to reconsider the role sound has, what it ‘does’ in music education spaces and implications for this on reconceptualising our sound pedagogies. Sound, as something in motion, is physically diffracted through our bodies and environments, creating vibrating and reverberating with bodies (whether human or non-human) (Burnard, Colucci-Gray, and Cooke Citation2022). This article, written as a series of reverberations, sets sound in motion, through a series of diffractions with literature and my research evidence. Diffraction is a physical concept of waves (sound, light or water), spreading outwards, meeting ‘interferences’ which may be generative, and creating patterns of difference as a result. For posthumanist writers, diffractive methodologies are ones of reading texts and experiences through one another, allowing interferences in these meetings to make patterns of difference appear and to produce creative and unexpected outcomes. Therefore, by diffractively playing with and reading literature and PhD experiences through each other, I deliberately set out to hear, notice and explore the patterns of difference, both effect – what happens – and affect – what is felt, that are created by these diffractive meetings. These patterns, I argue are reverberations, where thinking continues to spread and move through practices, bodies and spaces.

Throughout the article, the term sound is used, recognising the entangled thinking with sound studies and ethnomusicology, as well as education and posthumanist literature around this area. However, music, as part of the broader ‘sound world’ is specifically mentioned in relation to the educational contexts in discussion. Therefore, the role of sound and music is under consideration within these arguments.

Sound in music education: a humanist phenomena?

Arguably, talk (or maybe a lack of talk as silence) may be considered the foremost pedagogical sound that inhabits our educational spaces. This emphasis on the linguistic, and the long lineage of educational theory from which it arises, has led to much research about the power of dialogic pedagogies, which has significantly shaped the educational landscape (Kim and Wilkinson Citation2019), where the emphasis is on talk between humans as the most significant currency for learning. Even within music classrooms, the importance of human-voiced learning (oral or written) can be seen to have equal if not more importance than musical sound. In a 2012 Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) report, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) lamented the situation within English music education with the headline School Music lessons: Not enough music (BBC Citation2012). Arguably the recent education policy landscape across the UK and beyond continues to challenge teachers to justify the role of sound within classrooms, where the emphasis on the efficiency of the learning process to reach standardised measures used for accountability, and an emphasis on stateable, transmissible knowledge that is easily assessed, continues to influence pedagogical decisions (see Bath et al. Citation2020). However, the insecurities around the position of sound in the curriculum aren’t only a result of recent policy changes, but have a long lineage from Enlightenment epistemology, with its emphasis on rationalised, cognitive thought, where sound is perceived as a ‘tool’ to be ‘used’ to aid cognitive understanding (see Cooke Citation2021). This long-standing way of thinking about sound in relation to knowledge, learners and teachers – with individual humans at the centre of concern – has defined how sound and therefore music is conceptualised within education.

This can be outlined in relation to several interlinking facets, the first of which is where sound is used as a demonstration of individual learning. As with all enlightenment humanist thinking, where the focus is on individuals as ‘contained’ within non-porous, bounded ‘bodies’, sound, even in collaborative music making is often reduced to individual contributions or individual understandings of what occurred to gain understanding of individualised progress and knowledge for assessment purposes. As a result, emphasis is placed on the individual’s ability, the human ability, to ‘control’ what sounds are made, where they come from and what they are used to demonstrate. A second interlinked facet is the role of sound as a representation of something that is underpinned by a verbal explanation or meaning. This links to how aesthetic listening (Spruce Citation2016) and expectations for verbalised responding (Cooke Citation2022), are practised in music education, where there are assumptions about what is perceived as ‘correct’, ‘true’ or ‘fact’. This practice creates a hard boundary that separates the sound from the listener’s own experiences, ideas and responses. The sound and what it means is thought to exist prior to the student or teacher engaging with it. This assumption of there being a sound that is ‘correct’, and that is ‘out there’ as a fixed entity, also applies to some forms of Western art music performance and composition (a third facet). As Hill notes, ‘standard modes of ensemble music-making … focus[ed] on a prescribed, even “right” sound, rather than offering opportunities for rich, divergent sound exploration’ (Hill Citation2018, 54).

All of these interlinked facets exemplify the reification of music as an aesthetic object within education which leads, Regelski argues, to the maintenance of works of music as ‘self-referential … [as] an autonomous “expression” of the composers “inner life” that is isolated, cerebralised and reified as the absolute (and absolutely Good) formal and expressive meanings claimed to be “in” a score’ (Regelski Citation2020, 32). Abramo (Citation2014) links this reification of sound too dominant educational practices, where the ‘[knowledge] banking concept of music education’, where reified factual, transmissible knowledge can be ‘banked’ into the cognitive memory, leads to a focus on ‘the uniform meaning of music and musical works … composers’ and famous performers’ intent and music theory’s unchanging labels and signifiers’ (Abramo Citation2014, 92–93). This focus on a fixed product, something that is abstracted from self, re-emphasises sound and therefore music as a solely humanist endeavour (of the control and intent of the creator, and the absorption of the correct analysis or response by the learner). In doing so sound becomes (or remains) artificially detached from the environment and material-human processes of creation.

Sound and the posthumanist turn

Posthumanism, arising from a ‘constellation’ of theoretical and philosophical perspectives (Taylor and Hughes Citation2016), focuses attention on de-centring the human as a bounded individual, separated from other humans and material and environmental others. Instead, posthumanism challenges us to acknowledge the entangled nature of human and non-human relations, where we are constantly becoming with and making with all our material and human partners, in processes of ‘worlding together’ (Haraway Citation2016, 58). This entanglement of humans with more-than-human, challenges existing positions of human control, dominance and power and also epistemological understandings of subject and object as being separable. In this way, posthumanism shifts our gaze (Hultman and Taguchi Citation2010), and arguably our auditory attention, to re-see and re-hear the nature and importance of material and human, relationships within music classrooms, which arguably includes sonic relationships.

While there isn’t significant literature on posthumanism and music education, those who have begun to explore this area grapple with what sound (and silence) does within this posthumanist frame (Burnard, Osgood, and Elwick Citation2019; Cooke Citation2021; Pitt Citation2023). As noted by Pitt (Citation2023) ‘Musical utterances, expressions and movements are constituted by, and entwine with material, human, acoustics, and the environment’, recognising the entangled and situated nature of sound. My own PhD thesis argues that we need to ‘reconsider the role of sound not as a representation or record of action’ (which I argue is often how sound is conceptualised in humanist-focused music education) but as an ‘active participant’ with us as we become-with and make-with the world (Cooke Citation2021, 225), what Haraway describes as worlding-with (Haraway Citation2016, 58), in which nothing makes itself.

Acknowledging sound as an ‘active’ participant, pushes us to ask questions such as how do we develop (pre-service) music teachers’ sensorial attentiveness to what sound does and what it offers in music education spaces? However, there is an inherent tension when thinking about sound and posthumanist writings. Sound is neither a human body (which posthumanism argues we need to pivot away from valuing over all other bodies in an entanglement) nor a non-human material, which often provides the rebalancing focus of posthumanist writings. Instead, sound, and therefore music, is a manifestation of material-human enactments as ‘the intra-actions of sound waves diffracted through bodies and materials’ (Burnard, Colucci-Gray, and Cooke Citation2022, 191). Here the ‘intra’ denotes the way in which bodies (human and non-human) are mutually affected and affecting, where human and material, together creating sound, each become-with the making.

Arguably, the sound is the very manifestation of this intra-dependency, where it literally sounds the particular material-discursive act of the entanglement, which Goh terms ‘sounding situated knowledges’ (Goh Citation2017, 283). Sound does not exist ‘prior’ or ‘separated’ from the material – human enactment. It is only explainable through consideration of the discursive intra-actions between place, body, material and sound at that moment – in the enactment. However, to describe the sound as a consequence, can make it feel quite a passive participant in material-discursive enactment, where it is just something that happens as a result of the action. For Gershon (Citation2013), sound is more than a consequence, it is, he argues, ‘theoretically and materially consequential’ where ‘if everything vibrates, then everything – literally every object, ecology, feeling, idea, ideal, process, experience, event – has the potential to affect and be affected by another aspect of everything’ (Gershon Citation2013, 258 my emphasis). It is this notion of vibrations, where everything is constantly moving, which has garnered attention in posthumanist thinking, most notably from Jane Bennett’s notion of ‘Vibrant Matter’ (Bennett Citation2010), in which vibrancy, as vibrations, is central to her argument that matter is lively, agitated, full of potential to act and therefore we need to develop ‘a cultivated, patient, sensory attentiveness to nonhuman forces’ (xiv) in order to respond.

For Bennett and Gershon, the sound is always performative – it is ‘doing’. What it does as it travels across spaces, meets bodies and affects what happens in the classroom is consequential in what knowing is developed. It matters. Therefore, it is unsurprising that beyond music education, sound is increasingly explored by posthumanist writers and thinkers in studies exploring the role of sound in educational spaces (see Burnard, Osgood, and Elwick Citation2019; Davies and Renshaw Citation2019; Dermikos Citation2020; Gallagher Citation2011; Citation2016), sound as methodologically significant (see Flint Citation2022; Wargo Citation2019), sound and bodies, including the more-than-human (see Cereso Citation2014, Vallee Citation2022) or debates around sonic materialism or intersections between sound and posthumanist thinking (see Campbell Citation2020). There are also numerous studies that intersect more briefly with posthumanist thinking, from sound studies, anthropology and ethnomusicology which expand the debates around sound and posthumanism (see Allen and Titon Citation2023; Feld Citation2017; James Citation2019).

The intersections of this literatures from posthumanism, and other studies that focus on sound and its role, illuminate significant potential for generative thinking around sound and therefore, music within music education spaces. It asks us to re-hear the role of sound in learning, challenging assumptions about who or what is involved in sound creation, how students (and teachers) become with sound in our classrooms and what a sound pedagogy might involve.

Setting sound in motion: methodology

This article brings together evidence from my PhD project (Cooke Citation2021), in which a group of pre-service music teachers explored the idea of teaching as an improvisatory act, with pedagogical experiences of a ‘sound walk’ with pre-service music teachers (Colucci-Gray and Cooke Citation2019). The analysis that follows is the first occasion that these two sets of evidence, along with literature from sound studies, ethnomusicology and posthumanist sound articles, have been brought together to specifically explore the posthumanist turn in relation to sound in music education. Therefore, what happens next is a performative ‘diffracting’ and re-reading of this evidence through each other to illuminate possibilities for attending to sound differently.

Diffractive practices have become synonymous with posthumanist thinking following Haraway’s metaphorical (Citation2004) and Barad’s physical (Citation2007) theorising about the potential of thinking with diffractive waves as a methodological and pedagogical stance (Murris and Bozalek Citation2019). Such practices dismantle the subject/object divide, describing instead how all bodies (human and non-human) are entangled in constantly moving intra-active relationships which ‘open up and rework the agential conditions of possibility’ (Barad in Dolphiin and van du Turin Citation2012, 52). It is these diffractive practices of opening up and reworking, by reading insights, experiences and literature through each other (ref) which underpins the methodology of this article.

While much of the posthumanist literature works with ideas of diffraction related to water waves, there is scope for generative methodological thinking when considering diffractions of sound waves. To that end, what follows in this article is a series of reverberations created between the sound and posthumanist literature, research experiences and professional experiences in teacher education and music education. Reverberation can be defined as the prolongation of sound, which methodologically speaks to the returning (or re-tuning) of existing project materials with a new auditory attention. By re-hearing the role of sound in my work with pre-service music teachers, I attend to how the sound of my previous work continues to reverberate with and through my thinking. Reverberation can also be defined as a continuing effect, as a repercussion, which speaks to the way bringing together the literature around sound with my research experiences creates ‘productive disconcertions’ (Murris and Bozalek Citation2019) to set in motion thinking with the sound that makes difference. These reverberations each generate a response, patterns of effect and affect, which act as a provocation to think and write. This is not to act as a ‘fixed’ authoritative reading of the reverberations, but as one personal perspective which may lead you to make others think with it. Each is accompanied by an image or written ‘sketch’ of the action (written in italics), not to ‘capture’ and ‘bound’ what is discussed, which goes far beyond these artefacts, but to act as an ‘invitation into’ the analytical discussions.

Reverberations 1: re-hearing voice in music education

Voice in education literature is often conceptualised as human, singular and linguistic. Attention to voice has shifted over time, from a teacher as a transmitter, to more dialogic, learner-voice focused pedagogies; however, as Sfard notes, ‘the confidence in the benefits of talk seems unshaken’ (Sfard Citation2019, 89). However, such attention to the learner’s dialogue has created tensions in music education spaces, where this emphasis on linguistic sound has challenged the value of ‘music-led’, music-centred’ pedagogies. Posthumanism asks us to re-hear voice both as human and more-than-human, where ‘everything vibrates’ (Gershon Citation2013, 258) and consequently, every ‘thing’ is sound (whether perceptible or not). Posthumanism also challenges the notion of contained singular beings, and instead invites us to consider a ‘body as threshold’ (Springgay Citation2008) that is enacted in assemblages (Deleuze and Guattari Citation2003) with other bodies. In this view of humans, ‘voice’ is therefore not the product of one singular body, but instead is an enactment in between bodies, environments and materials (Mazzei Citation2013). In this posthumanist re-hearing of sound as more-than-human and ‘transindividual’ (Chadwich in Flint Citation2022) where sound is always the entanglement of time/space/place/bodies, sound within any situation can be re-heard as part of a polyphony of ‘intra-animating’ voices (Cooke Citation2021). Through such an intra-animation, humans and non-humans together enact a physical momentum (everything is vibrating) and collaborative power (through intra-actions with bodies to make things happen). Polyphony, while having a distinct musical meaning, is also a term used by Bakhtin (see Bakhtin Citation1981; Citation1984) to describe the notion of decentring authorial control, allowing all voices and perspectives to be equally valued. If everything is in motion, and all voices are equally valued, this creates what Braidotti might consider ‘potentia’ (Braidotti Citation2013), a form of empowerment. In this sense, polyphony has the resultant effect of empowering the momentum of humans and non-humans to continue to create something new or different, rather than relying on ‘stuck’ habits of what is heard, valuing certain sounds over others or replicating what already exists.

What follows is a re-hearing of a sequence of evidence from a PhD project workshop (in which we explored free improvisation activities), diffracted through and with Mazzei’s (Citation2013) notion of ‘voice without organs’, in which she argues for voice as ‘an entanglement of desires, intensities, and flows, a [Voice without Organs] that is made and unmade in the process that we call research and analysis’ (735) in which sound emanates ‘in an enactment among researcher-data-participants-theory-analysis’ (732).

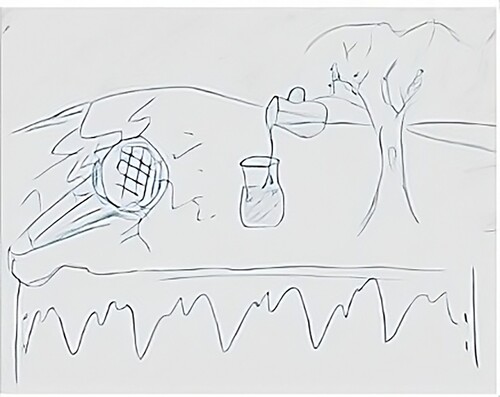

In diffractively re-hearing this sequence with Mazzei’s words, I pay attention to the intra-animating making and unmaking of voices of this moment ().

Figure 3. ‘A’ imitates dropping the keys, by pretending to drop the cymbal, but doesn’t let herself.

Analysing this sequence diffracted through the posthumanist sound literature, the ‘intra-animating’ (Cooke Citation2021) polyphonic voices of the sequence challenge me to pay attention differently – to attune differently. Here, the voices are not spoken with the mouth, or even sung, but I see-hear-feel the voices in this sequence as they re-perform with me while I re-listen to this sequence.

The voices of key-cymbal entanglement continue to sound in my head as I type, feeling the tension of their initial coming together, but also the grating metallic reverberation they left in motion. This was a tension, not expressed in words, or just in the sound created, but in the way the sound intra-animated (set in motion) all the bodies in the room. The intensities of the moment, called for all to voice the moment together, no-one (object or body) in that room weren’t part of expressing what was occurring.

Some voices resonated with the cymbal (the snare on the snare drum rattled), one member of the group who leant into the cymbal sound by playing the guiro to accompany the exploration. Sometimes the ‘potentia’ (Braidotti Citation2013) of the sound to intra-animated led to disturbances, interferences. Throughout the few seconds the keys and cymbal were ‘in play’, what counted as instrument, what was considered right or wrong, what was thought of as music / sound / noise were all made and unmade and made again. This soundful disturbance resulted in ‘A’ mimicking dropping a cymbal on the floor, but not quite allowing her to do so – maintaining what was classed as instrument and accepted practices of care towards it as a result. These weren’t notions expressed verbally and individually, but they were voiced collectively, as bodies reverberated to the shock and surprise of the situation.

Rewatching this video sequence, brings my attention to the materialdialogic pedagogies in play. Re-hearing voice as ‘transindividual’ (Chadwick in Flint Citation2022), as sound / body / material reverberations, is to see how materialdialogue, as an encounter between all in the entanglement, is essential in music education spaces. There was a collectively voiced challenge to the very essence of what was known, in this music education space, where the discursivity of bodies and materials created reverberations of different knowing.

To think with sound as voice, and its resonances and reverberations as voice is to provide a frame to express the importance of what sound ‘does’ in a music education space. It intra-animates, it creates moments of unlearning/relearning, it challenges expectations and assumptions, and leads us to understand how sound can, in its motion with and through us, make us differently.

Reverberations 2: sounding invitations to world-with

While sound is a manifestation of human-material entanglements, seemingly slipping between the descriptive power of the posthumanist literature of bodies and materials, evidence from my projects re-hears the role of sound not as a demonstration of cognitive learning, or as a site only for skill development, but instead as an invitation. To invite, meaning to request attention, participation or presence, is to speak to how sound acts, and what it does, within a space. It is an invitation that is constantly on the move, spreading, reaching, touching and encountering, not as a bounded object, but as a connection to others (human and non-human). This connecting of bodies, through sound, is, therefore, an invitation not only to pay attention to the sound in and of itself (as a reified object) but as an invitation to ‘world with’ (Haraway Citation2016, 17), where we become through intertwined sonic relational processes. As Murris argues, worlding-with problematises the idea of learning happening within someone, whereas posthumanism makes the argument that knowing and learning happen in the space between bodies, environments and materials (Murris Citation2016, 5). She, therefore, argues that as the knowing happens in between, which requires an embodied, felt response, we should reframe thinking as trans-corporeal and therefore, use the term ‘bodymind’ (Murris Citation2016, 7).

What follows is a re-examination of an image made from the audio recording of a ‘listening walk’ I did with pre-service music teachers. The walk was around campus, where I as the teacher stood back, and let the teachers and the sounds they encountered guide where we went, creating images in response to an audio recording of our walk. This experience is diffracted through and with Feld’s notion of ‘acoustemology’ (bringing together sound and epistemology) which he defines as ‘investigating sounding and listening as a knowing-in-action; a knowing-with and knowing-through the audible’ (Feld Citation2017, 85). Feld, an eminent ethnomusicologist, anthropologist and linguist, argues that acoustemology considers sound as a relational way of knowing, where it is situational, mutual and ecological. He argues that viewing sound in this way changes how we consider the spaces for sonic knowing, as ‘“polyphonic,” “dialogic” and “unfinalizable”’ (Feld Citation2017, 86). To (re)hear the sound as relational, as a connective force between us and what we are entangled with, is to think about the role of this ‘sonic knowing’ in music education spaces.

In diffractively playing with the image with Feld’s notion of acoustemology, I pay attention to how sound-voice-material intra-actions invite a situated, connectivity with all bodies (human and non-human) within music education spaces ().

Figure 4. Drawing from the audio recording of a ‘listening walk’ (Colucci-Gray and Cooke Citation2019).

The sounds encountered on the walk, and then represented in this image, speaks to the auditory ‘knowing-in-action’ (acoustemology) that was experienced with the full bodily senses of the drawer. The sound is not only individual ‘snips’ of different sounds shown spread out in time as they were experienced (as might be the case in a graphic score), they weren’t experienced or conceived of as a musical or sound ‘work’ (Goehr Citation1994). This reminds me of Goehr’s argument about musical works that;

Works cannot, in any straightforward sense, be physical, mental, or ideal objects. They do not exist as concrete, physical objects; they do not exist as private ideas existing in the mind of a composer, a performer, or a listener; neither do they exist in the eternally existing world of ideal, uncreated forms. They are not identical, furthermore, to any one of their performances. Performances take place in real time; their parts succeed one another. (Goehr Citation1994, 3)

There is a notable difference between the considerations of sound as ‘works’, as objects, in music, and the drawing created by this pre-service music teacher in response to sounds in the world as entangled, overlapping and as creating a ‘whole’. The image speaks to the way that materials (e.g. the microphone, and the jug), place (e.g. the hills, water and trees) and the bodies involved in listening are a ‘momentary configuration of space, time and place’ (Flint Citation2022, 523). Interestingly, the rhythmic soundwave at the bottom of the page is a response to the sound of feet walking during the recording, where the collaboration between human and non-human in creating sounds is acknowledged. Here the resonances between the human bodies with the material and environmental are drawn into relationship with each other, where sound provides the opportunity for ‘collaboration with the natural world’ (Allen, Titon, and von Glahn Citation2014, 12). This is a connectivity which clearly demands attention to how human and more-than-human sounds are intra-acting, where the human sounds are conceived as ‘worlding with’ as a contribution, a part of the sound world, as an active participant in what is being created. In undertaking this listening walk, noting how we felt, how we responded and how we drew responses, was to allow auditory knowing-in-action to influence, inform, create different understandings of the relationship between sound, music, listening, hearing, and our bodily responses.

To re-hear sound as an invitation for our learners to ‘world-with’, to learn with and know with the connectivities and relationships between humans and non-humans, is to reconsider the role of sound in our classrooms. This reverberation takes sound beyond a transactional tool, where we take something or learn something from sound as an abstracted object or work, towards the notion of sound as a way of ‘bringing us into relationship with’, to audibly ‘know-in-action’ and to ‘learn in the in between’ of bodies, materials and environments.

Reverberation 3: attentionality to sound as affect

In considering how sound is used as a tool for learning in music education (as a sound demonstration of cognitive knowledge or a site for skill development), is to question the relationship between sound and the entanglement in which it occurs, including the bodies with which the sound is set in motion. When it is used as something separated from environment and self, the sound is contained, where its reaching and affecting of/with bodies is downplayed. While the role of the body in music education has increasingly featured in thinking about pedagogies (see Bowman and Powell Citation2007; De Nora Citation2000; van der Schyff Citation2015), arguably this has been done mostly from a humanist standpoint and often has limited discussion of the role of sound (waves) on and with the bodies in our learning spaces.

Literature from sound studies, ethnomusicology, posthumanist studies and others, often refers to Cereso’s key article ‘(Re)Educating the senses’ (Cereso Citation2014). In doing so, attention is given to the vibratory affect of sound meeting with bodies, whereas Cereso argues, we need to ‘retrain our bodies to be more aware, alert and attuned to sonic events in all of their complexity’ (Cereso Citation2014, 103). At the core of Cereso’s argument is that the vibratory nature of sound, which inevitably affects more than just the ears, but the whole-body sensorium, involves a ‘synthetic convergence of sight, sound and touch … it can be seen, heard and felt’ (Cereso Citation2014, 104). As Dewey (Citation1933) notes, ‘sounds come from outside the body, but sound itself is near, intimate; it is an excitation of the organism; we feel the clash of vibrations throughout our whole body’ (246). Re-hearing resonances between sound and matter, which may resonate, echo, amplify or indeed interrupt, therefore, create an affect on how their intra-actions are heard or felt. Posthumanism, following writings from de Spinoza (Citation1994) and Deleuze and Guattari (Citation2003), considers affect, not only as an internally felt emotion, something that is within, but as any capacity to affect or be affected, through encounters in the world. Through these encounters, Gallagher argues, ‘any kind of body imping[es] on another body in some way that augments or diminishes the affected body’s capacities to act’ (Gallagher Citation2016, 43). In this way, the effect of sound isn’t merely a connective, a line of sound waves travelling between separated and bounded bodies, but is actively changing their nature, their abilities and capacities to act.

This way of thinking about the nature of sound, how it travels, mingles and affects, is to turn our attention to what sound ‘does’ within a space, not merely, what it contains or demonstrates. As noted by Gallagher (Citation2016), analysis of sound as an affect, ‘decentre[s] the human, positioning it as just one kind of body amongst many through which sound propagates … ’, attuning us to how sound waves move ‘through and between [all human and non-human] bodies’ (Citation2016, 43). As Dermikos (Citation2020) models in her paper about ‘fleshy frequencies’ in the primary classroom, this asks us to see/feel/hear how the sound (waves) ‘activates students’ feelings/emotions, while connecting, changing and moving bodies of all kinds’. In doing so, Dernikos, argues that affect (and therefore sound) can be expressed vocally and also manifests in non-vocal ways (e.g. through gesture). This is crucial in reconsidering how we understand what sound ‘does’ within music education spaces, where we, as learners and teachers, need to see/hear/feel what is audible, to understand how the sound has ‘acted’ upon us.

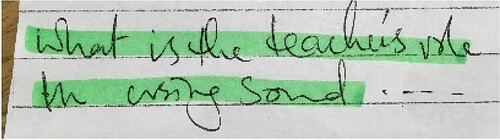

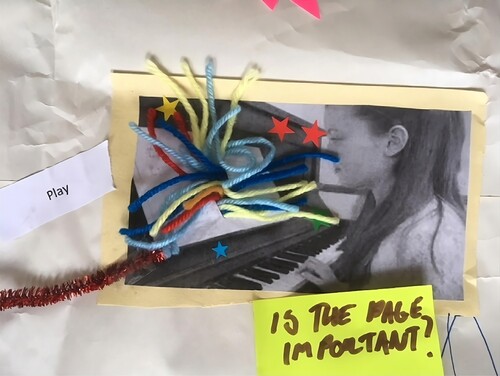

What follows is a diffraction of these ideas with a note left for me after one of the PhD workshops by a pre-service music teacher and a collage image created during one of the workshops. Each diffractively acts upon and with each other, as well as with the notion of sound as an affect ( and ).

Figure 5. What is the teacher’s role in using the sound. Note left after one of the PhD workshops by a music teacher.

Figure 6. Collaged picture created during a PhD workshop. Initial responses towards this picture, prior to the collaging session had described it using phrases like ‘sitting for so long’, ‘bashing things out’ ‘desperately trying to reach the standard’ (referring to needing piano skills to get into the music education course).

Diffractively playing with ‘sound as affect’ with these two images, brings me to consider the tensions between them, between insecurity around the role of sound for the teacher in the first image, and in the second, prior to the collaging, the view of there being a ‘standard’, and implied ‘correct’, sound that needed to be produced or achieved in order to meet externally set expectations. This tension between ‘why and what sound’ and ‘correct and standardised’ sound, speaks to how sound as affect can be productive in providing a different perspective on what sounds ‘do’ in our spaces. Without verbalising that this was the teacher’s intention, the collaged image, for me expresses the movement, the reaching of the sound. I am intrigued that the movement is from the page, not from the piano, where it almost speaks to the ‘potentia’ (Braidotti Citation2013) contained and released from the composed material. In doing so it downplays the entanglement of the sound with the piano, where maybe the instrument is illustrated as merely a ‘tool’ to produce the affective. It also speaks to me of the difference between the unadulterated image as failing to reveal the full affect of making the music that results. This is evident in the responses to the image prior to the collage process.

This notion of the ‘hidden affect’ in images of music education, brings me circling back to the question about the teacher’s role in using sound, realising that this too, is not easily portrayed. I begin to wonder with the idea of disintegrating the boundaries between sound as affecting learners / teachers / materials. Sound as affect doesn’t discriminate. All bodies within a music education space are affected and respond (whether sonically or physically) to the vibration movements. Does this shift the question, from what is the teachers ‘uses’ of sound, to how are teachers’ partners in creating and responding to sound within the classroom? In her article about the methodological significance of sound in research, Flint (Citation2022) argues that

What we attune to, the resonances we listen to, how we listen, not only shapes our perceptions of places and spaces, but shapes our engagements with those spaces and places, shaping them in the process. What we attune to matters, because it shapes how we are responsible to places and spaces, our relations of becoming together. (Flint Citation2022, 537)

Taking Flint’s argument, as teachers, what we attune to, how we listen will therefore shape how we consider what is occurring in our classrooms, but also shape how we then intra-act in that entanglement as teachers. In other words, attuning, paying attention, using all of our sensorial bodies, is to hear/see/feel what sound is doing. Cereso (Citation2014) argues this very point, stating in reference to composers that they must understand audiences as embodied, and consisting of ‘sensing, nerve-filled, responsive bodies’ (Cereso Citation2014, 115). Cereso’s argument surely equally applies to our classrooms. Reconceptualising the space as one full of sensing bodies, including the teacher, is to reconsider how we help all of us be more attentive to ‘sonic doings’, ‘affects of sound’ and sound possibilities through sonic play and experimentation. In doing so, we move away from the tensions of ‘correct or standardised’ sounds in the pre-collage image, and questions about ‘who’ is involved in sound practices and for what purpose as imagined in the first image.

To pay attention to sound as a ‘doing’ as an affect is to shift attention to how we as teachers facilitate the types of entanglements (of sounds with bodies, materials and ideas) that support musical understanding. As Cereso argues (Citation2014), this may involve creating tasks in the classroom which deliberately set out to heighten attention to what sound is doing as it reaches, spreads, resonates and reverberates with and through our bodies. From a posthumanist stance, this is also to heighten attention to the intra-actions between sound and material bodies.

Reverberating implications for practice and research

In this article, I have illustrated how posthumanist thinking challenges conceptions of sound, and therefore music, within our classrooms. In diffractively playing with literature from posthumanism, ethnomusicology and sound studies, with my PhD workshop materials and an image from a listening walk with pre-service music teachers, I have argued that reconceptualising sound with posthumanism creates a generative space for imagining and doing music education pedagogy differently. The reverberations individually and collectively shift our attention from what sounds are (how they can be used to demonstrate something, or what they contain to be heard, or how they can be used to achieve something pre-planned or standardised) to what they do (as an affect, as an invitation to world-with, and as an entanglement of voices, both humans and non-humans).

The potential implications for educators of these arguments are wide-reaching, and generative for new ideas and practices. Firstly, in rehearing ‘voice’ as encompassing human and non-human sounds, and the way that these ‘intra-animate’ each other, this article opens space to rearticulate what we may mean by dialogic pedagogy in music education spaces. It also asks us to consider how sound can fundamentally ‘make us differently’ whereby it challenges, exposes, reaffirms and sometimes makes us ‘unlearn’ what we thought we knew. This difference-making equally applies to teachers as it does to learners, where we need to acknowledge more explicitly the affective role sound has on our bodies as well as those who attend our classes. Thirdly, to re-hear sound as an invitation is to consider how we as teachers facilitate entanglements of sound, bodies and matter that create invitations to explore and learn in ways that are valuable and meaningful to our students. These invitations aren’t contained – where it is the bringing together of bounded individuals and materials into a neutral space, but it is an invitation to ‘world-with’ where in these entanglements we create worlds, we create our world, and we become with each other. As argued by Feld, this involves a sonic ‘knowing-in-action’, challenging us to create conditions in our learning spaces where such sonic knowing can feature. For Cereso (Citation2014), such conditions are created through sonic play and experimentation, a sentiment echoed by Cage in his writings on ‘purposeless play’ and ‘purposeful purposelessness’ (Cage in Hill Citation2018). Cereso argues that such play and experimentation with sounds heightens our attention to the affect of sound on and with our bodies, while posthumanism broadens this concern to considering the affect of sound on all bodies (including the non-human).

Music education is uniquely placed to explore and contribute to emerging posthumanist literature on the role of sound, whereby further theorisation can be generated on the unique place sound work/play has in music education. This is a shift from justifications of sound as a ‘tool’ to be ‘used’ for linguistic and cognitive learning, to sound as an essential and defining mode within music education, where ‘intra-animation’ with materials and environments and attention to sonic affect, are vital in our collective future making. In doing so, the opportunity is there not only to fully realise the potential of sound as part of posthumanist entanglements to explain and explore the way we world-together but also to contribute significantly to thinking about diffractive methodologies, where we move beyond thinking with water waves and the metaphorical symbolism that occurs as a result, to an inclusion of sound wave language, imagery and thinking.

Ethical statement

Consent for all images has been given, and institutional ethical approval gained

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Carolyn Cooke

Carolyn Cooke is a senior lecturer at the Open University, UK. With a background in music education and teacher education, Carolyn completed her PhD ‘Troubling’ music education; playing, (re)making and researching differently’ in 2020. She actively writes and presents in the areas of STEAM education, transdisciplinarity, performativity in research, Appreciative Inquiry and posthumanism.

References

- Abramo, J. 2014. “Music Education That Resonates: An Epistemology and Pedagogy of Sound.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 22 (1): 78–95. https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.22.1.78

- Allen, A., and J. T. Titon, eds. 2023. Sounds, Ecologies, Musics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Allen, A., J. T. Titon, and D. von Glahn. 2014. “Sustainability and Sound: Ecomusicology Inside and Outside the Academy.” Music and Politics 8 (2): 2–26. https://doi.org/10.3998/mp.9460447.0008.205.

- Bakhtin, M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination. Edited by M. Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Edited and translated by Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bath, N., A. Daubney, D. Mackrill, and G. Spruce. 2020. “The Declining Place of Music Education in Schools in England.” Children and Society 34 (5): 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12386

- BBC. 2012. “School Music Lessons: Not Enough Music, Says Ofsted.” March 2. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-17226187.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bowman, W., and K. Powell. 2007. “The Body in a State of Music.” In International Handbook of Research in Arts Education, edited by Liora Bresler, 1087–1106. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Burnard, P., L. Colucci-Gray, and C. Cooke. 2022. “Transdisciplinarity: Revisioning How Science and Arts Together Can Enact Democratizing Creative Educational Experiences.” Review of Research in Education 46 (1): 166–197. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X221084323

- Burnard, P., J. Osgood, and A. Elwick. 2019. “Sounding Spaces (spacetimemattering) in Museums: Feminist New Materialism and New Directions in Early Years Music Education Research.” Poster Presented at the Research in Music Education (RIME) Conference, Bath.

- Campbell, I. 2020. “Sound’s Matter: ‘Deleuzian Sound Studies’ and the Problem of Sonic Materialism.” Contemporary Music Review 39 (5): 618–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2020.1852804

- Cereso, S. 2014. “(Re)educating the Senses: Multimodal Listening, Bodily Learning, and the Composition of Sonic Experiences.” College English 77 (2): 102–123. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201426145

- Colucci-Gray, L., and C. Cooke. 2019. “Knowledge to Knowing: Promoting Response-Ability Within Music and Science Teacher Education.” In Posthumanism and Higher Education: Reimagining Pedagogy, Practice and Research, edited by Carol Taylor and Annoushka Bayley, 165–187. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cooke, C. 2021. “‘Troubling’ Music Education: Playing, (Re-)making and Researching Differently.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh.

- Cooke, C. 2022. “Making-with in Music Education.” Curriculum and Pedagogical Inquiry 14 (1): 101–116. https://doi.org/10.18733/cpi29652

- Davies, K., and P. Renshaw. 2019. “Who’s Talking? (And What Does It Mean For Us?): Provocations from Beyond Humanist Dialogic Pedagogies.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education, edited by N. Mercer, R. Wegerif, and Louis Major, 38–49. London: Routledge.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 2003. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. 5th ed. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Denmead, T. 2015. “For the lust of not knowing : Lessons from artists for educational ethnography.” In Beyond methods: Lessons from the arts to qualitative research, edited by L. Bresler. Malmo: Malmo Academy of Music.

- De Nora, T., ed. 2000. “Music and the Body.” In Music in Everyday Life, 75–109. Cambridge-Obeikan.

- Dermikos, B. P. 2020. “Tuning ‘into’ Fleshy Frequenices: A Posthuman Mapping of Affect, Sound and De/Colonized Literacies with/in a Primary Classroom.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 20 (1): 134–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798420914125

- de Spinoza, B. 1994. A Spinoza Reader: The Ethics and Other Works. Translated by Edwin. M. Curley. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Dewey, J. 1933. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath and Company.

- Dolphiin, R., and Iris van du Turin. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies. Michigan: Open Humanities Press. University of Michigan.

- Feld, S. 2017. “On Post-Ethnomusicology Alternatives: Acoustemology.” In Perspectives on a 21st Century Comparative Musicology: Ethnomusicology or Transcultural Musicology?, edited by F. Giannattasio and Giovanni Giuriata, 82–97. Udine: Nota.

- Flint, M. A. 2022. “More-than-Human Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Listening to the Leafblower.” Qualitative Research 22 (4): 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794121999028

- Gallagher, M. 2011. “Sound, Space and Power in a Primary School.” Social and Cultural Geography 12 (1): 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.542481

- Gallagher, M. 2016. “Sound as Affect: Difference, Power and Spatiality.” Emotion, Space and Society 20:42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.02.004

- Gershon, W. S. 2013. “Vibrational Affect: Sound Theory and Practice in Qualitative Research.” Cultural Studies – Critical Methodologies 13 (4): 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708613488067

- Goehr, L. 1994. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Online ed. Oxford: Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198235410.001.0001.

- Goh, A. 2017. “Sounding Situated Knowledges: Echo in Archaeoacoustics.” Parallax 23 (3): 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2017.1339968

- Haraway, D. 2004. “The Promise of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate Others.” In The Haraway Reader, edited by Donna Haraway, 63–124. New York: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hill, S. C. 2018. “A ‘Sound’ Approach: John Cage and Music Education.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 26 (1): 46–62. https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.26.1.04

- Hultman, K., and Lenz Taguchi. 2010. “Challenging Anthropocentric Analysis of Visual Data: A Relational Materialist Methodological Approach to Educational Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 23 (5): 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.500628

- James, R. 2019. The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism and Biopolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Kim, M.-Y., and I. A. G. Wilkinson. 2019. “What is Dialogic Teaching? Constructing, Deconstructing and Reconstructing a Pedagogy of Classroom Talk.” Learning, Culture and Social Interactions 21:70–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.02.003

- Mazzei, L. A. 2013. “A Voice Without Organs: Interviewing in Posthumanist Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788761

- Murris, K. 2016. The Posthuman Child: Educational transformation through philosophy with picturebooks. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Murris, K., and V. Bozalek. 2019. “Diffracting Diffractive Readings of Texts as Methodology: Some Propositions.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (14): 1504–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1570843

- Pitt, J. 2023. “A Posthuman Paradigm for Early Childhood Music: Musical Play as Mycelial Embodied Polyphony.” Paper Presentation, Research in Music Education (RIME) Conference, April 2023.

- Regelski, T. 2020. “Tractate on Critical Theory and Praxis: Implications for Professionalizing Music Education.” Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 19 (1): 6–53. https://doi.org/10.22176/act19.1.6

- Sfard, A. 2019. “Learning, Discursive Faultiness and Dialogic Engagement.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education, edited by N. Mercer, R. Wegerif, and Louis Major, 38–49. London: Routledge.

- Springgay, S. 2008. Body Knowledge and Curriculum: Pedagogies of Touch in Youth and Visual Cultures. New York: Peter Lang.

- Spruce, G. 2016. “Listening and responding and the ideology of aesthetic listening.” In Learning to Teach Music in the Secondary School, edited by C. Cooke, K. Evans, G. Spruce, and C. Philpott. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Taylor, C. A., and C. Hughes. 2016. Posthuman Research Practices in Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vallee, M. 2022. “Sound and Critical Posthumanism.” In Palgrave Handbook of Critical Posthumanism, edited by S. Herbrechter, Ivan Callus, Manuela Rossinni, Marija Grech, Megan de Bruin-Mole, and Christopher John Muller, 519–536. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- van der Schyff, D. 2015. “Praxial Music Education and the Ontological Perspective: An Enactivist Response to Music Matters 2.” Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education 14 (3): 75–105.

- Wargo, J. M. 2019. “Be(com)ing ‘In-Resonance-With’ Research: Improvising a Postintentional Phenomenology Through Sound and Sonic Composition.” Qualitative Inquiry 26 (5): 440–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418819612.