ABSTRACT

Bronze Age agriculture in Europe is marked by the adoption of new crops, such as broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), broad bean (Vicia faba) and gold-of-pleasure (Camelina sativa). Yet, at a regional level, it is sometimes unclear when, where and why these crops are adopted and whether they were all adopted at the same time. Croatia is one such region where archaeobotanical research is limited, making it difficult to discuss Bronze Age agriculture and diet in more detail. The discovery of a burnt-down house with crop stores at Kalnik-Igrišče provides a unique archaeobotanical assemblage and snapshot of late Bronze Age agriculture (1000–800 BC). From the carbonised plant remains discovered at Kalnik-Igrišče we see a dominance in the crops broomcorn millet, barley (Hordeum vulgare), free-threshing wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum/turgidum) and broad bean. Emmer (Triticum dicoccum), spelt (Triticum spelta), and lentil (Lens culinaris) were also found, suggesting they were probably minor crops, while spatial analysis indicates distinct crop storage areas within the building. Overall, these finds support the adoption and integration of these new crops within northern Croatia by the late Bronze Age, while highlighting implications for seasonal strategies, risk management, and cultural dietary choice.

Introduction

Bronze Age societies in Europe are typically characterised by increasing social complexity, technological progress, intensified use of natural resources, changes in agriculture, increased production, and the expansion of interregional trade networks. These conditions, together with increased social conflicts, are considered the main causes of increased political complexities in many parts of Europe (Harding Citation2000, Citation2002; Kristiansen and Larsson Citation2005; Earle and Kristiansen Citation2010). Such changes intensified during the late Bronze Age (c. 1350 BC–800 BC) when the Urnfield cultural tradition, distinguished by their cemeteries of cremated burials in urns, dominated much of Europe. Under this cultural group, many regional groups developed distinct characteristics, such as particular types of dress, different types of metal objects, pottery styles and ritual practices (e.g. Ložnjak Dizdar Citation2005; Karavanić Citation2009; Dizdar Citation2010). In the southern Carpathian Basin, a wide range of settlement types exist from isolated farmsteads to large fortified settlements, with some larger settlements containing traces of streets, houses and craft activity areas (e.g. Hänsel and Medović Citation1992; Teržan Citation1999; Kroll and Reed Citation2016). The relationship between these settlements is relatively unknown although some suggest that larger settlements became political centres, controlling food production, manufacture and trade, while smaller periphery settlements focused on supplying those centres with goods (Gogâltan Citation2008; Fischl et al. Citation2013).

The Bronze Age also sees the intensification and diversification of agricultural practices, with the development of new tools and production techniques, as well as an increase in wool production and intensified animal management (Kroll Citation1990; Medović Citation2002; Gyulai Citation2010; Bökönyi Citation1971; Sabatini, Bergerbrant, and Brandt Citation2019; Zavodny et al. Citation2019). In the river lowlands of northern Italy and the southern and western edges of the Pannonian plain (extending roughly between Vienna (Austria) in the northwest, Košice (Slovakia) in the northeast, Zagreb (Croatia) in the southwest, Novi Sad (Serbia) in the south and Satu Mare (Romania) in the east) the archaeobotanical evidence is relatively patchy (Benac Citation1951; Bandini Mazzanti, Mercuri, and Barbi Citation1996; Castelletti and Montella de Carlo Citation1998; Castelletti Citation1972; Costantini and Costantini Biasini Citation2007; Culiberg and Šercelj Citation1995; Follieri Citation1981; Giachi et al. Citation2010; Hänsel, Mihovilić, and Teržan Citation1997; Heiss Citation2008, Citation2010; Kroll and Borojević Citation1988; Kroll and Reed Citation2016; Mariotti Lippi et al. Citation2009; Medović Citation2002, Citation2012; Mercuri et al. Citation2006; Pals and Voorrips Citation1979; Rottoli Citation1997; Reed Citation2013; Schmidl and Oeggl Citation2005; Šoštarić Citation2001). A recent study by Filipović et al. (Citation2020) suggests that by the mid-fifteenth century BC, broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) was present in the middle Danube region—in the territory of modern-day Romania (Corneşti-Iarcuri), Hungary (Fajsz 18) and perhaps Croatia (Mačkovac-Crišnjevi). Similarly broad bean (Vicia faba), and the oil plant gold-of-pleasure (Camelina sativa) and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) are also not seen until the middle Bronze Age, at sites such as Feudvar in Serbia (Kroll and Reed Citation2016). How crop strategies differ between regions and how agriculture links with wider socio-economic developments is less understood in the Carpathian Basin. In northern Croatia, located at the south-western part of the Pannonian Plain, only seven sites have yielded archaeobotanical remains, and generally in low quantities, restricting interpretation (Reed Citation2016).

More recently, excavations at Kalnik-Igrišče () have uncovered large quantities of carbonised plant remains within the burned-down ruins of a late Bronze Age house. Plant remains, originating from a smaller part of the house, have already been processed and published and show a wide range of crops (Mareković et al. Citation2015; Karavanić, Kudelić, and Mareković Citation2015; Karavanić et al. Citation2017; Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019a). The excavations that followed (Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2017, Citation2019b) have revealed the outlines of the entire building and more archaeobotanical evidence. Since systematic excavations of Bronze Age settlements are still rare in this region, Kalnik-Igrišče provides a unique case study to explore local agricultural practices. This paper will, therefore, present the most recent archaeobotanical evidence from Kalnik-Igrišče and what this may say about agricultural production and consumption at the site. Furthermore, the excavations now enable the examination of the spatial distribution of the plant remains within the house area, including storage habits. Although preservation is patchy, we will also attempt to examine Kalnik-Igrišče within the wider Carpathian region to explore the interrelationship between society, food and environment at these late Bronze Age communities.

Figure 1. Location of the late Bronze Age site of Kalnik-Igrišče, Croatia (Image adapted from Ramspott Citation2017).

The Excavations at Kalnik-Igrišče

The Kalnik-Igrišče site is located within a forested area 500 metres above sea level on the southern slopes of the Kalnik hill, northern Croatia, in the south-western part of the Pannonian Plain. Its strategic position and location near abundant natural resources (i.e. fertile soil, water and raw materials) make it a good spot for a settlement. The site was discovered in the 1980s and the first systematic excavations were carried out between 1988 and 1990 (Majnarić-Pandžić Citation1998; Karavanić Citation2009, 18–19). The significance of this research lies in the discovery of a portion of a settlement from the early Urnfield period (), where smaller bronze objects were probably produced (Majnarić-Pandžić Citation1998). Based on the significance of this research, in 2006 new systematic archaeological excavations were initiated, and with short interruptions, continue to the present day.

The new excavation campaign conducted between 2006 and 2019 was carried out on the eastern edge of the terrace and revealed the remains of a multi-layered settlement, occupied during different periods (Copper Age, Bronze Age, late Iron Age, Roman and late Middle Ages). However, the most preserved remains were from an in situ burnt house dated to the late Urnfield period (Ha B2/3, ) located at the edge of a long and spacious natural terrace oriented to the south. The archaeological excavation revealed the remains of a square house that had a minimum of two levels, as a result of adaptation to the slanted terrain. The western, peripheral part of the house was explored during excavations conducted between 2008 and 2012, while the eastern and greater part of the same building was explored between 2016 and 2019 (). The house remains are 6.5 metres long and 5 metres wide and oriented east–west, as well as a slightly elevated second level that has the same dimensions. The house walls were built with deeply set wooden pillars and were supported at the ground level with a narrow drywall structure. Due to the lack of abundant daub remains, to indicate plaster on the walls, it is presumed that the walls and floor were made of wood.

Due to the house burning down the eastern part of the building is very well preserved to the point that finds form distinct functional areas and allowed organic remains to become well preserved through carbonisation. As a result, a large dataset has been collected relating to household organisation, including carbonised plant macro-fossils, wood remains, ceramic vessels, hearths, stone tools, animal bones, bronze items and other finds characteristic of the settlement area (Karavanić Citation2009; Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2017, Citation2019a; Karavanić, Kudelić, and Mareković Citation2015, Citation2017; Mareković et al. Citation2015; Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019b). The most numerous findings are dated to the last stage of the late Bronze Age or the end of the Urnfield culture (1000–800 BC). A large quantity of ceramic vessels were found, consisting of shallow and deep bowls and larger vessels, which would have been used for food preparation, serving, as well as solid or liquid storage (Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019a, 73–101). The pottery style indicates the Ha B phase of the late Urnfield culture and fits within the tradition of the Ruše cultural group in Slovenia (Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019a, 78).

Currently, only one part of the animal bones has been examined which were located just below the burned remains of the house. The bones were dominated by pig (MNI 10), followed by cattle (MNI 8) and ovicaprids (sheep and goat) (MNI 8), as well as the remains of a horse (Radović Citation2019, 167–180). Many of the bones were from older individuals with some evidence of butchering. It is suggested that pig and cattle were the primary meat source, with sheep being possibly utilised for wool.

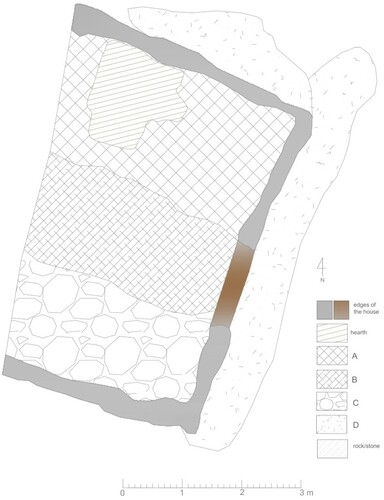

Materials

The carbonised plant remains presented here were collected from two late Bronze Age horizons/phases. Phase A dated to the very end of the Bronze Age or Ha B/Ha C stage by relative chronology (end of the eighth and the beginning of the ninth century BC). This phase is characterised as a working area where no aboveground residential structures were recorded, but hearths, with traces of activity closely related to bronze craft production, were identified (Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019a, 53–56). Phase B, underneath Phase A, were the remains of a well preserved burned late Bronze Age house dated to Ha B phase and most of the plant remains were found inside these ruins. Three distinct areas within the house were identified and named A, B and C, while two further areas located along the edge of the house were named zone D ( and ). The zones within the house are determined based on the distribution of different deposit composition and movable archaeological material.

Figure 4. Plan of the four zones in the eastern side of the Bronze Age house at Kalnik-Igrišče (Phase B).

Zone A: On the northern side of the building, in an area of approximately 5 m2, a complex hearth construction, made of clay and wood, was discovered. Above the hearth structure, several partially complete ceramic vessels were found, perhaps originally located above the hearth. Samples were collected from within the hearth, where clumps of glued plant residues were found. Beneath the hearth, a large deposit of carbonised plant remains (mainly cereals) were found together with burned organic material of unknown origin and layers of clay.Footnote1

Zone B: Directly south of the hearth zone, on an area of approximately 6 m2, samples were collected from a dark grey deposit that contained a wealth of burned organic material of unknown origin as well as small fragments of wood. In addition, a few small-sized ceramic fragments were found, and also one fully preserved cup.

Zone C: South of zone B was a deposit of fragmented and partially whole ceramic vessels. Together with the pottery, several stone objects and ceramic weaving equipment were also found. This area is approximately 3 m2 and represents the south-eastern edge of the house. Plants remains were collected together with the soil, while some larger seeds, like Vicia faba and the fruits, were collected separately by hand.

The eastern edge of the building was labelled as zone D; however, organic matter was less visible. It was noted during excavations that carbonised acorns were present along the inside edges of the building and were usually found in small clusters.

Methodology

During the 2016–2018 campaigns, archaeobotanical samples were collected from Phase A and B. Plant remains were handpicked while excavating Phase A, while bulk soil samples and handpicking were conducted within Phase B, the late Bronze Age house (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). The samples were then examined at the Faculty of Science, Department of Botany in Zagreb. At the lab, the bulk samples were dried and sieved using a 250 μm, 315 μm and 1.0 mm mesh. Material sieved to below 315 μm was discarded after initial screening revealed no plant remains. Where the dry screening method was not sufficient to separate the soil from the plant remains the samples were wet sieved under running water. Due to the large size of some of the samples, it was decided to only sort one-third by using a grid method to randomly select a representative fraction (see Polonijo Citation2019).

The carbonised plant remains were subsequently sorted and identified under a zoom stereo-microscope at a magnification of 7–45× with the help of reference literature/seed atlases (Cappers and Neef Citation2012; Neef et al. Citation2011; Heinisch Citation1995), as well as the modern carpological collection (under establishment) of the Botany Division. The nomenclature of scientific plant names follows for cultivars Zohary and Hopf (Citation2000) and for wild plants Flora Croatica Database (Nikolić Citation2018). Barley (Hordeum vulgare) was not differentiated between naked or hulled. Free-threshing tetraploid (Triticum turgidum/durum) and hexaploid (Triticum aestivum/compactum) wheat grains were not distinguished within the samples due to morphological similarities in the grains and the absence of diagnostic rachis fragments. Even though free-threshing tetraploid wheat has not been identified in Croatia within prehistoric contexts, we cannot rule it out. Whole grains were counted as one, two longitudinal fragments and embryos of grains were also counted as one. Glume bases were counted as one, while whole spikelet forks were counted as two glume bases. Cereal remains classed as fragments present had to be at least one-fourth of the original grain/seed, anything smaller was not counted. The fruit and weed seeds were counted as one, even when only a fragment was found, except where large seeds were broken and clearly represented the same parts of the same seed (e.g. Quercus sp.).

It is also worth noting that there are inherent biases in the data presented. First, samples that were handpicked will be biased towards larger seeded taxa. Second, a greater quantity and diversity of plant remains correspond with samples that were collected in bulk and sieved. Bulk samples were collected in areas that were visibly organic rich. Although this method can result in missed information, here the high preservation of the plant remains means that it is probably unlikely that the overall pattern would have changed significantly if more sieving had occurred during excavations. Handpicking also reduced the fragmentation of the plant remains during the post-excavation process.

Results

The results presented here derive from the analysis of 28 samples collected from Phase A, a late Bronze Age/early Iron Age work area (LB/IA) and 76 samples from Phase B, zones A–D within the late Bronze Age house structure. A total of 47 carbonised plant remains were present within Phase A, while approximately 29,900 seed remains were recovered from Phase B (Supplementary Table 1). Preservation of the plant remains within Phase B, zones A–D was generally very good, allowing a high level of identification. Seed density is also high in most of the water sieved samples from this area. A small number of carbonised plant remains from Phase A suggests they are secondary or tertiary deposits, as they are dispersed and are not located in a specific or defined area. These plant remains will, therefore, not be discussed any further within this paper.

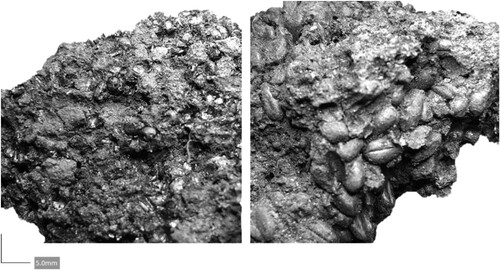

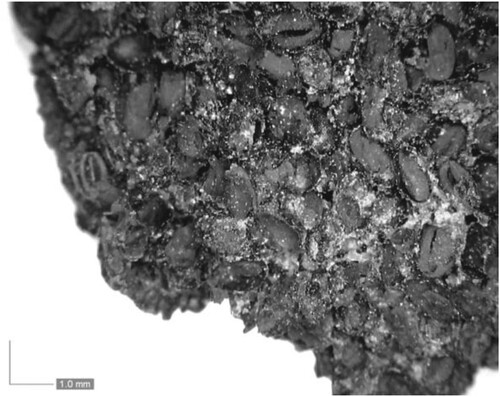

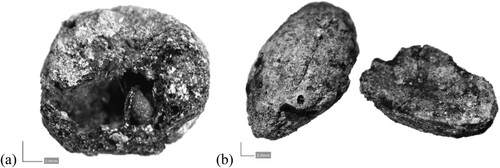

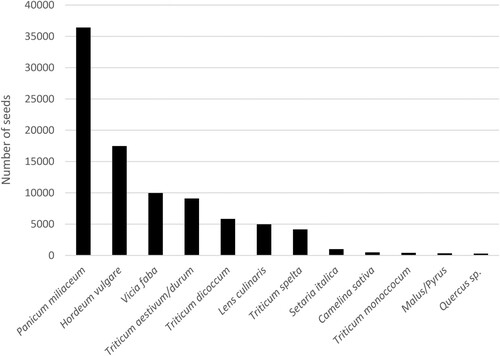

Overall, the Bronze Age house samples (Phase B) were dominated by broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), representing about 58% of the assemblage if we exclude all fragmented remains. This was followed by barley (Hordeum vulgare) and free-threshing wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum/turgidum), representing about 20% and 11% of the assemblage, respectively. Although not counted separately twisted barley grains were also noted, indicating the presence of the six-row variety. A large lump of broomcorn millet overlaying a layer of free-threshing wheat was also found in zone B and has been estimated to represent about 300 millet and about 200 free-threshing wheat grains (). Grains of emmer (Triticum dicoccum), einkorn (Triticum monococcum), spelt (Triticum spelta) and foxtail millet (Setaria italica) were also present but in much smaller quantities. Due to the overlap in morphologies, especially after charring , several cereal grains could not be distinguished between species, so over 1000 grains were classified as either cf. or grouped as free-threshing/spelt wheat. Over 2500 fragments of cereal grains were also recovered. Cereal chaff was rarely found with only one emmer and three einkorn glume bases being identified in zone A and B. Of the pulses, broad bean (Vicia faba) dominated the group with only a few lentils (Lens culinaris) and one pea (Pisum sativum) found in zone C. Interestingly a lump of the oil crop gold-of-pleasure was found in zone B and is estimated to represent about 500 seeds ().

Figure 5. Lump of carbonised broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), image to the left, fused to a layer of free-threshing wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum/turgidum), image to the right, from SU435/436, Sample 799 within zone A of the Bronze Age house at Kalnik-Igrišče.

Figure 6. Lump of carbonised Gold-of-Pleasure (Camelina sativa) from SU447, Sample 773 within zone B of the Bronze Age house at Kalnik-Igrišče.

Over 260 acorns were also recovered from within the house, along with nearly 100 whole and fragmented wild apple/pear (Malus/Pyrus) fruits (). In previous publications of the site, Malus sylvestris was identified; however, further research into wild pear and apple species showed that it is very difficult to distinguish between them, thus here we identify the fruits as apple/pear. A small number of other fruits were also identified, including three cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), and three blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) seeds. Only about eight species of wild or possible weed seeds were present in the samples. The most numerous was barnyard millet (Echinochloa crus-galli), which had over 840 seeds, while only a small number of other grasses were present, including possible oat (Avena sp.), ryegrass (Lolium sp.) and brome (Bromus sp.). No diagnostic oat florets were recovered and so it is unclear whether the grains identified are cultivated or wild, but it is likely at this time and with the low quantity recovered that they represent a weed within the main crops.

Figure 7. Carbonised remains of (a) an apple/pear (Malus/Pyrus) fruit, and (b) two acorn halves (Quercus sp.) recovered from within the Bronze Age house at Kalnik-Igrišče.

Spatial Distribution

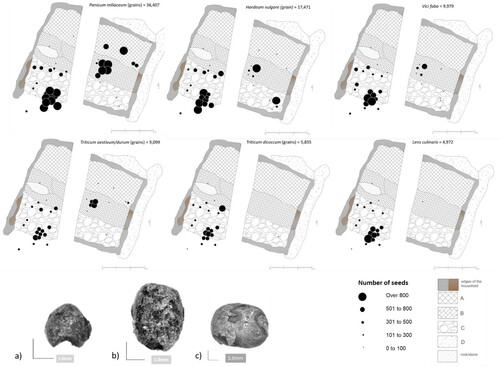

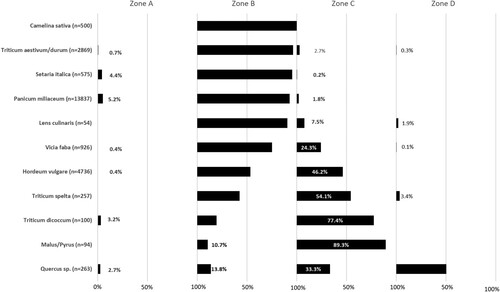

Examining the plant remains within each zone there is a clear difference in the quantity and range of remains found. Zone A, a hearth structure in the house, yielded about 3500 plant remains and these were dominated mostly by broomcorn millet and free-threshing wheat. Zone B, the area south of the hearth, had over 22,600 plant remains, again dominated by broomcorn millet and also barley, free-threshing wheat and broad bean. Over 92% of the broomcorn millet grains recovered were from this zone (). The lump of gold-of-pleasure seeds, the largest deposits of barnyard millet and over 90% of the foxtail millet and lentil were recovered from this zone. Zone C, an area south of zone B, only had about 3,565 plant remains and is dominated by over 2000 barley grains, as well as containing the highest percentage of emmer, acorns and apple/pear remains. Zone D, which represents the edges/walls of the house, has very few plant remains, but is dominated by acorn remains that the excavators noted were found in clusters along the buildings wall.

Figure 8. Percentage of the most abundant taxa (excluding wild/weed plant remains) within each zone of the Bronze Age house, Kalnik-Igrišče.

The previously published plant remains from the western side of the house (Karavanić Citation2008; Mareković Citation2013; Mareković et al. Citation2015; Karavanić, Kudelić, and Mareković Citation2015, Citation2017) have a comparable representation of crops to those found on the eastern side. The analysis of 69,116 carbonised plant macrofossils showed that 98% of the finds belonged to cultivated cereals and pulses. Similar to the eastern side broomcorn millet dominated the assemblage but on the western side there were more emmer, spelt and lentil recovered (Supplementary Table 1). If we combine both the western and eastern sides of the house we see that, unsurprisingly, broomcorn millet is the most abundant followed by barley, broad bean and free-threshing wheat ().

Figure 9. Overall number of carbonised plant remains per species (not including cf.) from the western and eastern part of the Bronze Age house at Kalnik-Igrišče.

If we roughly plot the most abundant crop species on a map of the excavated house at Kalnik-Igrišče we see two clusters emerge, one in the south western section and one in the middle eastern section in zone B (). There is also a less defined scatter of plant remains in the northeast where concentrations of broomcorn millet were found, including the lump of broomcorn millet and free-threshing wheat. In the middle of zone B the only evidence of gold-of-pleasure was found. Furthermore, emmer wheat and lentil seem to be largely absent from the eastern side of the house.

Discussion

Crop Production and Consumption at Kalnik-Igrišče

The burnt-down house at Kalnik-Igrišče provides a unique view of the last stage of occupation. From the carbonised plant remains we see dominance in the crops broomcorn millet, barley, free-threshing wheat and broad bean. Emmer, spelt, and lentil were also found in relatively high quantities in the western side of the house, suggesting they were also crops, although maybe in a more minor capacity. Evidence of cereal chaff was relatively infrequent with only 199 chaff fragments of emmer, einkorn and free-threshing wheat being recovered from the western side and 4 glume bases of emmer and einkorn in the eastern side. This, along with the absence of straw, culm and awn fragments and the relatively low weed remains, would suggest that the crops had been processed in another location and were stored within this house in a state ready to be processed for food (Hillman Citation1984; Jones Citation1984; Van der Veen Citation1992). Although there is a relatively high number of barnyard millet grains, these correspond with samples with high broomcorn millet remains and could be weeds within the summer annual (e.g. Schmidl and Oeggl Citation2005). For example, their similar size and shape to broomcorn millet may indicate that the inhabitants were not able to thoroughly clean the crop of these weeds. However, it cannot be ruled out that these grains could have also been grown/collected at the site (Bieniek Citation2002; Kroll Citation2017).

Inside the house, there were only a few fragments of stone that could have been used as a quern or work surfaces for grinding the cereals. It is, therefore, probable that the house was used more for storage and cooking, with the possibility that the hearth could also have been used to dry or semi-process some of the crops. Possible food residues have been seen on the inside of a small number of cooking pots (Karavanić and Kudelić Citation2019a, 96, Figure 6.19a). The food residues were preserved mainly as a carbonised crust, with a whitish deposit, distributed horizontally below the rim zone possibly indicating liquid or semi-liquid food (soups or porridge). Chemical analyses on the samples have not yet been performed, so the composition of the coating/precipitate is currently unknown. No other food remains are present at the site. Porridge-like foods have been regularly found at prehistoric sites. In particular, the late Bronze/early Iron Age hilltop site of Kush Kaya, situated in the Eastern Rhodope mountains, Romania, had remains of a possible millet-barley porridge found in situ within one of the dwellings (Popov, Marinova, and Hristova Citation2018).

The recognition of wild plants as food is notoriously problematic in the archaeological record (e.g. Dennell Citation1976; College and Conolly Citation2014; Wallace, Jones, and Charles Citation2019). However, at Kalnik-Igrišče the presence of whole wild apple/pear (Malus/Pyrus sp.) fruits and acorns (Quercus sp.) found regularly within the building and by the hearth suggest they represent food for the inhabitants, rather than as animal feed. Both the acorns and the wild apple/pears can be stored for long periods. Acorns, in particular, are nutritionally comparable to cereals and have been consumed in the form of bread, soups, porridge, or even as herbal coffee throughout history (Pliny N.H. 6–7; Moreno-Larrazabal et al. Citation2014; Sekeroglu, Ozkutlu, and Kilic Citation2017). At the Bronze Age Alpine sites of Hauterive-Champréveyres, Fiavé-Carera and Zug-Sumpf, ceramics with charred acorns peeled and covered by a mushy matrix inside were recovered (Jacquat Citation1989; Evans Citation1994; Karg and Haas Citation1996). However, acorns contain high concentrations (depending on the species) of tannic acid, which require the acorns to be either soaked in water, boiled or roasted (Šálková et al. Citation2011). Acorn roasting is believed to have occurred at the Bronze Age site of Moers-Hülsdonk, Germany (Knörzer Citation1972) where a large rectangular pit contained charred acorns, emmer, barley, oat (Avena sp.), apples (Malus sylvestris) and hazelnuts (Corylus avellana). Whether these activities occurred at Kalnik-Igrišče is unknown. Sporadic finds of cornelian cherry (Cornus mas) also suggest that they were collected from the local environment to supplement the diet. No other significant numbers of wild edible seeds are found within the house.

Food Storage at Kalnik

The storage of food is a significant step towards long-term food security allowing populations access to food for a longer period after harvesting and minimising the risks of famines. Storage is also a key element in the development of settlement patterns, social relations and the local economy (Jones et al. Citation1986; Halstead and O’Shea Citation1989; Forbes and Foxhall Citation1995; Bogaard et al. Citation2009; Winterhalder, Puleston, and Ross Citation2015). A great diversity of plant storage systems have been identified in prehistory including subterranean structures, clay bins and ceramic vessels (e.g. Urem-Kotsou Citation2017; Filipović, Obradović, and Tripković Citation2018). Ethnographic evidence also shows that containers of a perishable nature, such as baskets, wooden chests or animal skins, were regularly used, as well as simply storing crops in a heap on the floor (Halstead Citation2014, 158–159; Peña-Chocarro et al. Citation2015).

At Kalnik, the large deposits of in situ plant remains found within the house indicate stored crops. The spatial analysis shows that the crops, broomcorn millet, free-threshing wheat, barley and broad bean were mainly stored in the south-western part of the house as well as the central-east part of the house (zone B). As no ceramic vessels were found in that part of the building they were probably stored in wooden chests or textile bags. This is the case for other zones, where there is little evidence of pottery storage, but rather storage of crops in perishable containers. For example, the acorns in zone D were found in small clusters, suggesting that the acorns were stored in textile bags and hung on the walls. The hanging of other plants in textile bags is not excluded.

Characteristics of Late Bronze Age Agriculture in Croatia and the Surrounding Region

The carbonised plant remains discovered at Kalnik-Igrišče fit within our wider understanding of agricultural production present Europe during the end of the Bronze Age. We already know that agriculture arrived on the territory of Croatia ca. 6000 cal BC and involved the cultivation of predominantly einkorn, emmer, barley, pea, lentil, and flax (Linum usitatissimum) (Reed Citation2015; Gaastra, de Vareilles, and Vander Linden Citation2019). These main crops continue to dominate in southeast Europe until the Bronze Age (ca. 2400–800 cal BC) when clear changes are seen and new crop types, including broomcorn millet, spelt and broad bean, are cultivated (Akeret Citation2005; Stika and Heiss Citation2013; Gyulai Citation2014; Reed Citation2013, Citation2016). Free-threshing wheat is also more frequently found in larger quantities during the Bronze Age, especially in southeast Europe, although it has been noted as a crop earlier in northwest Europe (e.g. Kirleis, Klooß, and Kroll Citation2012). Within Serbia and Hungary, the identification of the oil plant gold-of-pleasure and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) by the late Bronze Age also indicates the introduction of these new cultivars into the region (Kroll Citation1990; Medović Citation2002; Gyulai Citation2010, 105).

Within the territory of modern-day Croatia the archaeobotanical evidence is rather sparse with only 10 sites having published archaeobotanical remains dating to the Bronze Age (). As seen in , few crop remains have been recovered from these sites. What they do show is the presence of broomcorn millet and broad bean, as well as singular grains of barley, free-threshing wheat and lentil. These are common species present within the wider European territory, but due to the limited number of samples, it is impossible to discuss in more detail crop husbandry practices or differences between sites or even the two different climatic micro-regions of Croatian territory (Mediterranean and continental).

Table 1. Bronze Age sites in Croatia that have archaeobotanical remains (excluding Kalnik-Igrišče).

Table 2. Number of plant remains per species per site dated to the Bronze Age in eastern Croatia. Note that all cf. identifications have been merged with each species.

If we look at the wider region of the Panonnian plain, sites such as Feudvar (Hänsel and Medović Citation1998; Kroll and Reed Citation2016) and Židovar (Medović Citation2002) located in northern Serbia, which also yield abundant plant remains, we see a similar representation of cereal species. From early Bronze Age layers at Feudvar the assemblage is dominated by emmer, barley and einkorn (Kroll and Borojević Citation1988; Kroll Citation1998, Citation2016). By the middle Bronze Age within the western trench, the presence of einkorn and barley remains relatively consistent as main crops, while emmer decreases slightly (Kroll Citation2016). Broomcorn millet is rare in early levels but increases by the middle Bronze Age, suggesting it begins to be grown, possibly as a minor crop (Kroll Citation2016, 104–105). Broad bean is rare and spelt and free-threshing wheat remain at low levels throughout the early/middle Bronze Age period. At Židovar, archaeobotanical remains were dominated by free-threshing wheat and einkorn (Medović Citation2002). Gold-of-pleasure is found more frequently in this region, however, this may simply be due to poor sampling in Croatia or preservation biases as oil-rich seeds are less likely to survive charring. It is not until the early Iron Age at the site of Kalakača in northern Serbia where we see archaeobotanical assemblages dominated by broomcorn millet, barley, and einkorn (Filipović Citation2015).

In the central Pannonian plain in the Hungarian territory, generally, broomcorn millet and broad bean are not found in any significant quantities during the Bronze Age (e.g. Bölcske-Vörösgyír, Tiszaalpár-Várdomb, Budapest, Albertfalva – Hunyadi J. u., and Pécs-Nagyárpád) (Gyulai Citation2010; Reed Citation2013, 161). Instead, many of the Bronze Age sites are largely dominated by einkorn and barley. Interestingly, broomcorn millet and broad bean become more frequent at sites dating to the end of the Bronze Age and early Iron Age (Gyulai Citation2010). This pattern is seen too in Austria where evidence of both broomcorn and foxtail millet stores at Himmelreich, Siebeneich and Ganglegg confirms the importance of millets as a crop in the Iron Age (Schmidl, Jacomet, and Oeggl Citation2007).

Very few sites exist that are comparable with Kalnik, i.e. a Bronze Age house burnt down with plant remains in-situ. Previously Mareković et al. (Citation2015) compared the Austrian site Kulm bei der Trofaiach dated to ninth to eighth century BC (Stika Citation2000), which is also a wooden house destroyed by fire within a hillside location, to Kalnik-Igrišče. Here the site is dominated by emmer, followed by rye brome (Bromus secalinus) then broomcorn millet and barley. It was suggested that evidence of emmer grains and chaff in a relatively clean deposit in the building indicated that the emmer grains were stored within their glumes (Stika Citation2000). Another site worth noting is middle Bronze Age Feudvar, where houses and streets were excavated and sampled for archaeobotanical remains (Kroll and Reed Citation2016). Although general spatial analyses were conducted it was inconclusive to what this meant for social organisation and storage strategies. The analysis of the weed species did, however, identify possible differences in crop husbandry regimes with barley being grown more extensively (large scale and low labour input), while einkorn and emmer may have been more intensively gardened (small scale and high labour input regime, with possible manuring) (Kroll and Reed Citation2016). Due to the low number of weed seeds recovered at Kalnik it is not possible to currently identify possible crop husbandry strategies, however, further analyses are currently underway to examine whether grain stable isotopes can identify different crop husbandry strategies at the site.

The recovery of such large numbers of whole wild apple/pear fruits and seeds from Kalnik-Igrišče is also unique for Bronze Age Europe, where only a handful of remains have been recovered from 19 other sites in Poland, Hungary, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands (Kroll Citation2010; Gyulai Citation2010; Castelletti Citation1996; Cornille, Antolin, and Garcia Citation2019; A. Cornille and F. Antolín pers comm.). Interestingly near Kalnik-Igrišče the Iron Age site of Kaptol also has evidence of wild apples within Halstatt burial mounds (Šoštarić et al. Citation2016). Acorns are similarly found sporadically across Europe at both Bronze and Iron Age sites (Deforce et al. Citation2009) as well as on the sites in Croatia (Borojević et al. Citation2008; Reed Citation2020).

The Rise of Broomcorn Millet, Free-Threshing Wheat and Broad Bean Cultivation in Southeast Europe During the Bronze Age

There are many factors involved in the decision to adopt or reject a new crop variety. These driving mechanisms may include environmental constraints and adaptive traits of the species, cultivation and processing technologies, nutritional and agronomic qualities, social relationships between source and receiving regions, and cultural associations of status, ritual, and culinary appeal. Jones et al. (Citation2011) discuss three drivers behind the adoption of certain crops: ecological opportunism, economic relations and cultural identity. They proposed that ecological drivers were probably the main catalysts during the Bronze Age, particularly with the advantages of fast-maturing crops (e.g. millet) and their possible use in agricultural strategies for risk-minimisation and multi-cropping. Mass migration (Allentoft et al. Citation2015) and climate change have both been linked to the changes seen during the Bronze Age. For example, in the Po Plain (Northern Italy) during the Bronze Age increased crop varieties, such as millet and barley, were noted during dry phases (Cremaschi et al. Citation2016). Millet is drought-tolerant and fast growing, resulting in its use as a summer crop in crop rotation systems in the past (e.g. Spurr Citation1983; Miller, Spengler, and Frachetti Citation2016). Recently Zavodny et al. (Citation2017) proposed that the marginal environment of the Lika region of Croatia, which is soil poor with long winters, prompted the adoption of millet by Iron Age farmers in order to stagger growing seasons with a greater range of crops and minimise risk. In addition, a study of human bone collagen from individuals across 33 archaeological sites in Poland and western Ukraine showed that individuals consuming millet generally appeared to be linked geographically to upland regions compared to lowland ones (Pospieszny et al. Citation2021). With these debates in mind why then did millet, broad bean and free-threshing wheat become main crops at Kalnik during the late Bronze Age?

Today the southern parts of the Kalnik hills are marked by vineyards and although still quite forested would have provided fertile soil for the cultivation of the crops identified at the Bronze Age house. No pollen cores can help us to determine whether any environmental fluctuations occurred, so we must assume that the fertile soils near Kalnik would have made it unlikely that millet was grown particularly as a ‘famine’ crop. Multi-cropping is noted in second-millennium BC texts from Mesopotamia, which detail an early harvest with autumn-sown barley and a later harvest with short-season spring-sown millet and oilseeds (Jones et al. Citation2011). However, at Kalnik the temperate European climate may have limited this method of multi-cropping as the cooler climate may have extended the autumn growing season. Instead, the increased millet cultivation could have coincided with increased populations and thus increased agricultural land under cultivation. If we think about labour requirements, the millet growing season would have been staggered with the autumn sown cereals, such as barley and wheat, and would not have increased labour pressures in the autumn. Free-threshing wheat, although particularly demanding requiring rich soils, is also less labour-intensive to process compared to the glume wheats such as emmer and spelt, due to the grain detaching from the glumes during threshing. This again would help with labour bottlenecks at harvest time. If we look at pulses, they were probably spring sown at Kalnik, although in the Roman period Pliny (N.H.18.137) wrote that broad beans could be grown in Italy three times per year: January, March and October. The tradition of lentil and pea cultivation in Croatia would have made the adoption of broad bean relatively simple and could have even been inter-cropped with millet reducing labour peaks, as well as providing nitrogen to the soil. Plough animals would have allowed a modest expansion in the scale of intensive farming, easing labour limitations (Isaakidou Citation2011). In addition, the transition from wooden tools to metal ones must have had a significant impact on the depth and efficiency of ploughing, allowing a wider range of crops to be grown. Thus, growing seasons of crops, as well as their suitability to different landscapes, might have been linked to the wide spectra of crops found during the Bronze Age.

One final area to discuss is taste and socio-economic factors that may have contributed to the high millet, free-threshing wheat and broad bean cultivation and consumption at Kalnik. Studies recently are exploring more and more the culinary motivations that could distinguish different cultural groups, regions or even settlements (Valamoti et al. Citation2019, Citation2021). In Croatia, once millet arrives in the middle Bronze Age, it is regularly found at settlements. For example, at the early Iron Age site of Sisak (central Croatia) millet and broad bean are two of the main crops identified (Reed Citation2020). Could millet and broad bean have been a preferred regional crop, possibly distinguishing them from other neighbouring communities? Another factor to consider is whether the increase in crop diversity and possibly production could be linked with increased trade in food crops (Šálková et al. Citation2019). For example, Effenberger (Citation2018) compared the cereal spectra from several regions in Northern Germany and Scandinavia, revealing differences and similarities which allowed for the reconstruction of multiple possible contact zones and various influences from adjacent cultures. She suggested that the rising diversity of crop plants in the late Bronze Age reflects increased trade and an accelerated assimilation of innovations and new technologies. Whether this is true of Kalnik and the local region is hard to say at present, due to the limited number of sites to examine, however, these are all factors that could have impacted local production at the site.

Conclusion

Evidence of farming and diet in Bronze Age Croatia is currently limited. The discovery of Kalnik-Igrišče has, therefore, allowed a more detailed examination of crop production and consumption practices of a late Bronze Age society in Croatia and how these fit within wider patterns seen in southeast and central Europe. The burnt house provides unique evidence of stored crops and shows the cultivation of broomcorn millet, barley, free-threshing wheat and broad bean during the late Bronze Age. Emmer, spelt, and lentil were also found in relatively high quantities in the western side of the house, suggesting they were also crops, although maybe in a more minor capacity. Spatial analyses show crop storage areas in the centre and in south-western corner of the building. The lack of evidence of storage containers or pits also suggests that perishable items were probably used as containers for the crops. The relatively clean state of the crops, i.e. few weed seeds and no chaff, and evidence of food residues on several pots suggest crop processing occurred outside this building, while cooking took place within.

The evidence from Kalnik-Igrišče provides a coherent picture of the subsistence change that occurred throughout southeast Europe by the end of the Bronze Age. New research on the introduction and adoption of millet is showing its arrival into Croatia by the middle Bronze Age (Filipović et al. Citation2020), but it is not until the late Bronze Age at Kalnik-Igrišče that we see clear evidence of its cultivation as a crop. In neighbouring northern Serbia, the site of Feudvar shows its cultivation as a minor crop by the middle Bronze Age (Kroll Citation2016). At this time, other crops are also seen more frequently including broad bean, free-threshing wheat and gold-of-pleasure and their adoption, as well as evidently changes in diet, are likely interwoven within the broader socio-economic changes seen in the late Bronze Age. Thus, could the adoption of these crops reflect changes in agricultural practice, such as a shift to more extensive agriculture, increased variability in cultivation, and/or cropping in newly established arable areas, such as those that were waterlogged in winter and only available for summer crops (e.g. millet). Economically these crops could have reduced labour costs, in terms of free-threshing wheat being easier to process than glume wheats, and could offer greater food security, in terms of millet which can grow over short periods in drought conditions. Thus, these changes in agricultural practice would have had far-reaching impacts on land use and local resource availability, risk management strategies, cultural dietary choice, socio-economic complexity, and engagement within a larger European system. More research is clearly needed to understand the mechanisms by which food and farming evolved within wider socio-economic changes.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (31.6 KB)Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lisa Lodwick, Ruth Pelling and Michael Wallace for their helpful advice and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kelly Reed

Dr Kelly Reed is an archaeobotanist whose research focuses predominantly on the reconstruction of past diet and subsistence strategies in southeast Europe from the Neolithic to the Late Middle Ages (6000 BC – 16th Century AD).

Andreja Kudelić

Dr Andreja Kudelić is an archaeologist at the Institute of archaeology. Her research focuses predominantly on the Bronze Age pottery traditions in the territory of Croatia. She also conducts archaeological excavations of complex sites, so her interest is focused on the formation processes of the archaeological record, especially the remains of late Bronze Age settlements.

Sara Essert

Dr Sara Essert is Assistant professor at Biology Department, Faculty of Science (University of Zagreb). Her main research is focused on prehistoric plant use in continental and the Mediterranean parts of Croatia. Her recent publications include work on properties of subfossil wood.

Laura Polonijo

Laura Polonijo after her bachelors in urban forestry and protection of the environment, finished a masters at the University of science, Zagreb. There she completed a thesis on the archaeobotanical research of the prehistoric site Kalnik-Igrišće. As an environmental scientist, she now works as lead operative in the agency for protection of environment in Croatia.

Snježana Vrdoljak

Dr Snježana Vrdoljak is an archaeologist whose main field of interest is the Late Bronze Age of Central Europe and northern Croatia. She is also a field archaeologist excavating some major Late Bronze Age settlements in continental Croatia from the period between 1300 and 800 BC. Her research focuses on pottery analysis as well as bronze casting activities within the Late Bronze Age communities in southern Pannonia plain.

Notes

1 In this paper, we analysed plant remains found on and near the hearth. The abundant cereal deposit under the hearth is still in the process of analysis, but preliminary findings suggest a large quantity of wheat and/or barley grains.

References

- Akeret, Ö. 2005. “Plant Remains from a Bell Beaker Site in Switzerland, and the Beginnings of Triticum spelta (Spelt) Cultivation in Europe.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14 (4): 279–286.

- Allentoft, M., M. Sikora, K. G. Sjögren, S. Rasmussen, M. Rasmussen, et al. 2015. “Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia.” Nature 522: 167–172.

- Bandini Mazzanti, M., A. M. Mercuri, and M. Barbi. 1996. “I semi/frutti dell’insediamento dell’ Eta del Bronzo die Monte Castellacio (76 m s.l.m., 44021′ N, 110 42′ E), Imola- Bologna.” In La collezione Scarabelli 2 Preistoria, edited by M. Pacciarelli, 175–180. Bologna: Imola.

- Benac, A. 1951. “O ishrani prehistoriskih stanovnika Bosne i Hercegovine.” Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja u Sarajevu 6: 272–279.

- Bieniek, A. 2002. “Archaebotanical Analysis of Some Early Neolithic Settlements in the Kujawy Region, Central Poland, with Potential Plant Gathering Activities Emphasised.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 11: 33–40.

- Bogaard, A., M. Charles, K. C. Twiss, F. Fairbairn, N. Yalman, D. Filipović, G. A. Demirergi, F. Ertug, N. Russell, and J. Henecke. 2009. “Private Pantries and Celebrated Surplus: Storing and Sharing Food at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Central Anatolia.” Antiquity 83: 649–668.

- Bökönyi, S. 1971. “The Development and History of Domestic Animals in Hungary: The Neolithic Through the Middle Ages.” American Anthropologist 73 (3): 640–674.

- Borojević, K., S. Forenbacher, T. Kaiser, and F. Berna. 2008. “Plant Use at Grapčeva Cave and in the Eastern Adriatic Neolithic.” Journal of Field Archaeology 33 (3): 279–303.

- Cappers, R. T. J., and R. Neef. 2012. Handbook of Plant Palaeoecology. Groningen: Barkhuis.

- Castelletti, L. 1972. “Contributo alle richerche paleobotaniche in Italia.” Rendiconti dell’istituto lombardo di scienze e lettere 106: 339–347.

- Castelletti, L. 1996. “Mele e pere selvatiche (Malus sylvestris e Pyrus sp.) carbonizzate.” In La grotta Sant’Angelo sulla Montagna dei Fiori (Teramo). Le testimonianze dal Neolitico all’Età del Bronzo ed il problema delle frequentazioni culturali in grotto, edited by T. di Fraia and R. Grifoni Cremonesi, 295–303. Pisa: Collana Studi Paletnologici.

- Castelletti, L., and S. Montella de Carlo. 1998. “L’uomo e le piante nella preistoria. L’analisi dei resti macroscopici vegetali.” In Archeologia in Piemonte – La preistoria, edited by L. Mercando and M. Venturino Gambari, 41–56. Torino: Museo Torino.

- College, S., and J. Conolly. 2014. “Wild Plant Use in European Neolithic Subsistence Economies: A Formal Assessment of Preservation Bias in Archaeobotanical Assemblages and the Implications for Understanding Changes in Plant Diet Breadth.” Quaternary Science Reviews 101: 193–206.

- Cornille, A., F. Antolin, E. Garcia, C. Vernesi, O. Brinkkemper, W. Kirleis, A. Schlumbaum, and I. Roldán-Ruiz. 2019. “A Multifaceted View on Apple Tree Domestication.” Trends in Plant Science 24 (8): 770–782. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.007.

- Costantini, L., and L. Costantini Biasini. 2007. ). “Economia agricola del Lazio a sud del Tevere tra Bronzo antico e Bronzo medio.” In Atti della XL Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano Preistoria e Protostoria, Strategie di insediamento fra Lazio e Campania in età preistorica e protostorica, Roma, Napoli, Pompei, 30.11–3.12.2005, 787–801.

- Cremaschi, M., A. M. Mercuri, P. Torri, A. Florenzano, C. Pizzi, M. Marchesini, and A. Zerboni. 2016. “Climate Change Versus Land Management in the Po Plain (northern Italy) During the Bronze Age: New Insights from the VP/VG Sequence of the Terramara Santa Rosa di Poviglio.” Quaternary Science Reviews 136: 153–172

- Culiberg, M., and A. Šercelj. 1995. “Anthracotomical and Palynological Research in the Palaeolithic Site Šandalja II (Istria, Croatia).” Razprave SAZU 36 (3): 49–57.

- Deforce, K., J. Bastiaens, H. Van Calster, and S. Vanhoutte. 2009. “Iron Age Acorns from Boezinge (Belgium): The Role of Acorn Consumption in Prehistory.” Arch Korr 39: 381–392.

- Dennell, R. W. 1976. “The Economic Importance of Plant Resources Represented on Archaeological Sites.” Journal of Archaeological Science 3: 229–247.

- Dizdar, M. 2010. “On Some Shapes of Fibulae from the Late La Tène Settlement of Virovitica – Kiškorija Sjever.” Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 27: 145–160.

- Earle, T., and K. Kristiansen. 2010. Organizing Bronze Age Societies: The Mediterranean, Central Europe, and Scandanavia Compared. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511779282

- Effenberger, H. 2018. “The Plant Economy of the Northern European Bronze Age – More Diversity through Increased Trade with Southern Regions.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 27: 65–74.

- Evans, J. 1994. “Organic Residues from Fiavé, Italy.” In Scavi archeologici nella zona palafitticola di Fiavé-Carera Parte 3, Campagne 1969-1976. Resti cultura materiale cera – mica, edited by R. Perini, 1095–1098. Trento: Patrimonio Sorico e Artistico del Trentino 12.

- Filipović, D. 2015. “‘Granaries’ of Early Iron Age Kalakača, Northern Serbia and the Issue of Archaeobotanical Taphonomy.” Bulgarian e-Journal of Archaeology 5: 99–115.

- Filipović, D., J. Meadows, M. Dal Corso, W. Kirleis, A. Alsleben, Ö. Akeret, F. Bittmann, et al. 2020. “New AMS 14C Dates Track the Arrival and Spread of Broomcorn Millet Cultivation and Agricultural Change in Prehistoric Europe.” Scientific Reports 10: 13698.

- Filipović, D., Đ Obradović, and B. Tripković. 2018. “Plant Storage in Neolithic Southeast Europe: Synthesis of the Archaeological and Archaeobotanical Evidence from Serbia.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 27: 31–44. doi:10.1007/s00334-017-0638-7.

- Fischl, K. P., V. Kiss, G. Kulcsár, and V. Szeverényi. 2013. “Transformations in the Carpathian Basin around 1600 B.C.” In 1600 – Kultureller Umbruch im Schatten des Thera-Ausbruchs?, edited by H. Meller, F. Bertemes, H.-R. Bork, and R. Risch, 355–371. Halle (Saale): Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte.

- Follieri, M. 1981. “Significato dei resti vegetali macroscopici rinvenuti nell’abitato del Bronzo finale di Sorgenti della Nova.” In Sorgenti della Nova, Una comunità protostorica e il suo territorio nell’ Etruria Meridionale, edited by N. Negroni Catacchio, 261–264. Roma: CNR.

- Forbes, H., and L. Foxhall. 1995. “Ethnoarchaeology and Storage in the Ancient Mediterranean Beyond Risk and Survival.” In Food in Antiquity, edited by J. Wilkins, D. Harvey, and M. Dobson, 69–86. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

- Gaastra, J. S., A. de Vareilles, and M. Vander Linden. 2019. “Bones and Seeds: An Integrated Approach to Understanding the Spread of Farming Across the Western Balkans.” Environmental Archaeology, doi:10.1080/14614103.2019.1578016.

- Giachi, G., Secci M. Mori, O. Pignatelli, P. Gambogi, and M. Mariotti Lippi. 2010. “The Prehistoric Pile-Dwelling Settlement of Stagno (Leghorn, Italy): Wood and Food Resource Exploitation.” Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 1260–1268.

- Gogâltan, F. 2008. “Fortificaţiile tell-urilor epocii bronzului din Bazinul Carpatic.” O privire generală. Analele Banatului 16: 81–100.

- Gyulai, F. 2010. Archaeobotany in Hungary – Seed, Fruit and Beverage Remains in the Carpathian Basin from Neolithic to the Late Middle Ages. Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapitvany.

- Gyulai, F. 2014. “The History of Broomcorn Millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) in the Carpathian-Basin in the Mirror of Archaeobotanical Remains II. From the Roman Age Until the Late Medieval Age.” Columella - Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences 1 (1): 39–47.

- Halstead, P. 2014. Two Oxen Ahead: Pre-Mechanised Farming in the Mediterranean. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Halstead, P., and J. O’Shea. 1989. “Introduction: Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty.” In Bad Years Economics. Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty, edited by P. Halstead and J. O’Shea, 1–7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hänsel, B., and P. Medović. 1992. “14C-Datierungen aus den früh- und mittelbronzezeitlichen Schichten der Siedlung von Feudvar bei Mošorin in der Vojvodina.” Germania 70: 251–257.

- Hänsel, B., and P. Medović. 1998. Feudvar I. Das Plateau von Titel und die Šajkaška. Archäologische und naturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zu einer Kulturlandschaft (Titelski plato i Šajkaška. Arheološki i prirodnjački prilozi o kulturnoj slici područja). Prähist Arch in Südosteuropa, 13.

- Hänsel, B., K. Mihovilić, and B. Teržan. 1997. “Monkodonja, utvrđeno protourbano naselje starijeg i srednjeg brončanog doba kod Rovinja u Istri.” Histria Arch 28: 37–107.

- Harding, A. F. 2000. European Societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harding, A. F. 2002. “The Bronze Age.” In European Prehistory: A Survey, edited by S. Milisauskas, 271–334. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Heinisch, O. 1995. Samenatlas der wichtigsten Futterpflanzen und ihrer Unkräuter. Berlin: Deutsche Akademie der Landwirtschaftswissenschaften zu Berlin.

- Heiss, A. G. 2008. Weizen, Linsen, Opferbrote – Archäobotanische Analysen bronze- und eisenzeitlicher Brandopferplätze im mittleren Alpenraum. Dissertation am Institut für Botanik der Universität Innsbruck, Südwestdeutscher Verlag für Hochschulschriften, Saarbrücken.

- Heiss, A. G. 2010. “Speisen, Holz und Räucherwerk. Die verkohlten Pflanzenreste aus dem jüngereisenzeitlichen Heiligtum von Ulten, St. Walburg, im Vergleich mit weiteren alpinen Brandopferplätzen.” In Alpine Brandopferplätze. Archäologische und Naturwissenschaftliche Untersuchungen/Roghi votivi alpini. Archeologia e scienze naturali, edited by H. Steiner, 787–825. Trento: Editrice Temi

- Hillman, G. 1984. “Interpretation of Archaeological Plant Remains: the Application of Ethnographic Models from Turkey.” In Plants and Ancient Man: Studies in Palaeoethnobotany, edited by W. Van Zeist, and W. A. Casparie, 1–41. Rotterdam: Balkema.

- Huntley, J. 1996. “The Plant Remains.” In The Changing Face of Dalmatia, edited by J. Chapman, R. Shiel, and Š Batović, 225. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Isaakidou, V. 2011. “Farming Regimes in Neolithic Europe: Gardening with Cows and Other Models.” In The Dynamics of Neolithisation in Europe: Studies in Honour of Andrew Sherratt, edited by A. Hadjikoumis, E. Robinson, and S. Viner-Daniels, 90–112. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Jacquat, C. 1989. Les plantes de l’âge du Bronze. Contribution à l’histoire de l’environnement et de l’alimentation. Archéologie Neuchâteloise, 8. Saint-Blaise: Editions du Ruau.

- Jones, G. 1984. “Interpretation of Archaeological Plant Remains: Ethnographic Models from Greece.” In Plants and Ancient Man: Studies in Palaeoethnobotany, edited by W. Van Zeist, and W. A. Casparie, 43–61. Rotterdam: Balkema.

- Jones, M. K., H. V. Hunt, E. Lightfoot, D. Lister, X. Liu, and G. Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute. 2011. “Food Globalization in Prehistory.” World Archaeology 43: 665–675.

- Jones, G., K. Wardle, P. Halstead, and D. Wardle. 1986. “Crop Storage at Assiros.” Scientific American 254: 96–103.

- Karavanić, S. 2008. “Istraživanje višeslojnog nalazišta Kalnik-Igrišće 2007 / Excavation of the Multi-Layer Kalnik-Igrišće Site in 2007.” Annales Instituti Archaeologici 4: 62–65.

- Karavanić, S. 2009. The Urnified Culture in Contintal Croatia, BAR International Series 2036. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Karavanić, S., and A. Kudelić. 2017. “Kalnik – Igrišče – rezultati arheoloških iskopavanja u 2016. Godini / Kalnik – Igrišče – results of archaeological excavations in 2016.” Annales Instituti Archaeologici 13: 84–87.

- Karavanić, S., and A. Kudelić. 2019a. Kalnik-Igrišče - naselje kasnog brončanog doba / Kalnik-Igrišče – Late Bronze Age Settlement. Zagreb: Institut za arheologiju.

- Karavanić, S., and A. Kudelić. 2019b. “Kalnik-Igrišče – rezultati arheoloških iskopavanja u 2017. i 2018. godini / Kalnik – Igrišče – results of archaeological excavations in 2017 and 2018.” Annales Instituti archaeologici 15: 167–172.

- Karavanić, S., A. Kudelić, and S. Mareković. 2015. “Brončanodobni tragovi prehrane na Kalniku-sačuvani u vatri.” Cris 1: 116–127.

- Karavanić, S., A. Kudelić, S. Mareković, and R. Šoštarić. 2017. Archaeobotanical finds from the burned house at Kalnik-Igrišče site. In The Late Urnfield Culture between the Eastern Alps and the Danube, Proceedings of the International Conference in Zagreb, November 7– 8, 2013, edited by D. Ložnjak Dizdar and M. Dizdar, 9, 67–76. Serta Instituti Archaeologici.

- Karg, S., and J. N. Haas. 1996. “Indizien für den Gebrauch von mitteleuropäischen Eicheln als prähistorische Nahrungs - ressource.” In Spuren der Jagd – die Jagd nach Spuren. (Tübinger Monographien für Urgeschichte), edited by I. Campen, 429–435. Tübingen: Mo Vince.

- Kirleis, W., S. Klooß, H. Kroll, and J. Müller 2012. “Crop Growing and Gathering in the Northern German Neolithic: A Review Supplemented by New Results.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 21: 221–242.

- Knörzer, K.-H. 1972. “Eine bronzezeitliche Grube mit ge –rösteten Eicheln von Moers-Hülsdonk.” Bonner Jahrbücher 172: 404–412.

- Kristiansen, K., and T. Larsson. 2005. The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations. University Press: Cambridge.

- Kroll, H. 1990. “Melde von Feudvar, Vojvodina. Ein Massenfund bestätigt Chenopodium als Nutzpflanze in der Vorgeschichte.” Prähistorische Zeitschrift 65: 46–48.

- Kroll, H. 1998. “Die Kultur- und Naturland- schaften des Titeler Plateaus im Spiegel der metall- zeitlichen Pflanzenreste von Feudvar - Biljni svet Teitelskog platoa u bronzanum i gvozdenom dobu - Palaeobotanička analiza biljnih ostataka praistorijskog naselja Feudvar.” In Feudvar 1. Das Plateau von Titel und die Šajkaška, Prähistorische Archäologie in Südosteuropa 13, edited by B. Hänsel and P. Medović, 305–317. Kiel: Verlag Oetker/Voges.

- Kroll, H. 2010. “Die Archäobotanik von Bruszczewo – Darstellung und Interpretation der Ergebnisse.” In Bruszczewo II: Ausgrabungen und Forschungen einer prähistorischen Siedlungskammer Großpolens, edited by J. Müller, J. Czebreszuk, and J. Kneisel, 250–287. Bonn: Verlag.

- Kroll, H. 2015. “Spuren prähistorischer Nutzpflanzen aus Monkodonja – Die Pflanzenfunde.” Utvrđeno naselje Monkodonja / Die befestige Siedlung von Monkodonja, 104–108. Pula: Arheološki muzej Istre.

- Kroll, H. 2016. “Die Pflanzenfunde von Feudvar.” In Die Archäobotanik. Feudvar III. Würzburger Studien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie 1, edited by H. Kroll and K. Reed, 37–194. Würzburg: Würzburg University Press.

- Kroll, H. 2017. “Ökologie? – Ökonomie! Zu den Beifunden der neolithischen Getreidewirtschaft.” In Kontrapunkte. Festschrift für Manfred Rösch. UPA 300, edited by J. Lechterbeck and E. Fischer, 159–163. Bonn: Verlag.

- Kroll, H., and K. Borojević. 1988. “Einkorn von Feudvar. Ein früher Beleg der Caucalidion-Getreideunkrautgesellschaft aus Feudvar, Jugoslawien.” Prähistorische Zeitschrift 63: 135–139.

- Kroll, H., and K. Reed. 2016. Die Archäobotanik. Feudvar III. Würzburger Studien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie 1. Würzburg: Würzburg University Press.

- Ložnjak Dizdar, D. 2005. “Die Besiedlung der Podravina in der älteren Phase der Urnenfelderkultur.” Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 22: 25–58.

- Majnarić-Pandžić, N. 1998. “Brončano i željezno doba.” In Prapovijest, edited by S. Dimitrijević, T. Težak-Gregl, and N. Majnarić-Pandžić, 159–219. Zagreb: Naprijed.

- Mareković, S. 2013. “Carbonized Plant Remains from the Late Bronze Age site Kalnik-Igrišče.” Doctoral thesis, University of Zagreb, Zagreb.

- Mareković, S., S. Karavanić, A. Kudelić, and R. Šoštarić. 2015. “The Botanical Macroremains from the Prehistoric Settlement Kalnik-Igrišče (NW Croatia) in the Context of Current Knowledge about Cultivation and Plant Consumption in Croatia and Neighbouring Countries during the Bronze Age.” Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 84 (2): 227–235.

- Mariotti Lippi, M., C. Bellini, M. Mori Secci, and T. Gonnelli. 2009. “Comparing Seed/Fruit and Pollen from a Middle Bronze Age pit in Florence (Italy).” Journal of Archaeological Science 36: 1135–1141.

- Medović, A. 2002. “Archäobotanische Untersuchungen in der metallzeitlichen Siedlung Židovar, Vojvodina/Jugoslawien.” Ein Vorbericht, Старинар (Starinar) 52: 181–190.

- Medović, A. 2012. “Late Bronze Age Plant Economy at the Early Iron Age Hill Fort Settlement Hisar.” Rad Muzeja Vojvodine 54: 105–118.

- Mercuri, A. M., C. A. Accorsi, M. B. Mazzanti, G. Bosi, A. Cardarelli, D. Labate, M. Marchesini, and G. T. Grandi. 2006. “Economy and Environment of Bronze Age Settlements – Terramaras – on the Po Plain (Northern Italy): First Results from the Archaeobotanical research at the Terramara di Montale.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 16 (1): 43–60.

- Miller, N. F., R. N. Spengler, and M. Frachetti. 2016. “Millet Cultivation Across Eurasia: Origins, Spread, and the Influence of Seasonal Climate.” The Holocene 26 (10): 1566–1575.

- Moreno-Larrazabal, A., E. Uribarri, X. Peñalver, and L. Zapata. 2014. “Fuelwood, Crops and Acorns from Iritegi Cave (Oñati, Basque Country).” Environmental Archaeology 19: 166–175.

- Neef, R., R. T. J. Cappers, and R. M. Bekker. 2011. Digital Atlas of Economic Plants in Archaeology. Groningen: Barkhuis.

- Nikolić, T. 2018. Flora Croatica Database. Zagreb: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science. Accessed January 2019. http://hirc.botanic.hr/fcd.

- Pals, J.-P., and A. Voorrips. 1979. “Seeds, Fruits and Characoals from Two Prehistoric Sites in Northern Italy.” Archaeo-Physika 8: 217–235.

- Peña-Chocarro, L., G. P. Jordà, J. M. Mateos, and L. Zapata. 2015. “Storage in Traditional Farming Communities of the Western Mediterranean: Ethnographic, Historical and Archaeological Data.” Environ Archaeol 20: 379–389.

- Polonijo, L. 2019. "Arheobotaničko istraživanje prapovijesnog lokaliteta Kalnik-Igrišče." Unpublished dissertation, Sveučilište u Zagrebu.

- Popov, H., E. Marinova, and I. Hristova. 2018. “Plant Food from the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Hilltop Site Kush Kaya, Eastern Rhodope Mountains, Bulgaria: Insights on the Cooking Practices.” In Social Dimensions of Food in the Prehistoric Balkans, edited by M. Ivanova, B. Athanassov, V. Petrova, D. Takorova, and P. W. Stockhammer, 263–277. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Pospieszny, Ł, P. Makarowicz, J. Lewis, J. Górski, H. Taras, P. Włodarczak, A. Szczepanek, et al. 2021. “Isotopic Evidence of Millet Consumption in the Middle Bronze Age of East-Central Europe.” Journal of Archaeological Science 126: 105292.

- Radović, S. 2019. “Animal Husbandry of the Late Bronze Age Community.” In Kalnik-Igrišče: Late Bronze Age settlement, edited by S. Karavanić and A. Kudelić, 167–180. Zagreb: Institut za arheologiju.

- Ramspott, F. 2017. “Croatia Country 3D Render Topographic Map Border.” https://pixels.com/featured/croatia-country-3d-rendertopographic-map-border-frank-ramspott.html.

- Reed, K. 2013. “Farmers in Transition: The Archaeobotanical Analysis of the Carpathian Basin from the Late Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age (5000–900 BC).” Doctoral thesis, University of Leicester.

- Reed, K. 2015. “From the Field to the Hearth: Plant Remains from Neolithic Croatia (ca. 6000–4000 cal bc).” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 24: 601–619.

- Reed, K. 2016. “Archaeobotany in Croatia: An Overview.” Journal of the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb 49 (1): 7–28.

- Reed, K. 2020. “The Production and Preparation of Food at the Iron Age Settlement in Sisak.” In Segestica and Siscia – a Settlement from the Beginning of the History, edited by I. Drnić, 55–62. Zagreb: Archaeological Museum in Zagreb.

- Rottoli, M. 1997. “I resti botanici.” In Castellaro del Vhò. Campagna di scavo 1995. Scavi delle civiche raccolte archeologiche de Milano, edited by P. Frontini, 141–158. Milano: Comune di Milano, Settore Cultura e Spettacolo, Raccolte archeologiche e Numismatiche.

- Sabatini, S., S. Bergerbrant, L. Ø. Brandt, A. Margaryan, and M. E. Allentoft. 2019. “Approaching Sheep Herds Origins and the Emergence of the Wool Economy in Continental Europe During the Bronze Age.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11: 4909–4925.

- Šálková, T., O. Chvojka, D. Hlásek, J. Jiřík, J. John, J. Novák, L. Kovačiková, and J. Beneš. 2019. “Crops Along the Trade Routes? Archaeobotany of the Bronze Age in the Region of South Bohemia (Czech Republic) in Context with Longer Distance Trade and Exchange Networks.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11: 5569–5590.

- Šálková, T., M. Divišováa, S. Kadochovác, J. Benešb, K. Delawskáa, E. Kadlčková, L. Němečková, K. Pokorná, V. Voska, and A. Žemličková 2011. “Acorns as a Food Resource. An Experiment with Acorn Preparation and Taste.” Interdisciplinaria archaeologica 2 (2): 133–141.

- Schmidl, A., S. Jacomet, and K. Oeggl. 2007. “Distribution Patterns of Cultivated Plants in the Eastern Alps (Central Europe) During Iron Age.” Journal of Archaeological Science 34: 243–254.

- Schmidl, A., and K. Oeggl. 2005. “Subsistence strategies of two Bronze Age hill-top settlements in the eastern Alps – Friaga/Bartholomäberg (Vorarlberg, Austria) and Ganglegg/Schluderns (South Tyrol, Italy).” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 14: 303–312.

- Sekeroglu, N., F. Ozkutlu, and E. Kilic. 2017. “Mineral Composition of Acorn Coffees.” Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research 51: 504–507.

- Smith, D., V. Gaffney, D. Grossman, A.J. Howard, A. Milošević, K. Ostir, T. Podobnikar, et al. 2006. “Assessing the Later Prehistoric Environmental Archaeology and Landscape Development of the Cetina Valley, Croatia.” Environmental Archaeology 11 (2): 171–186.

- Šoštarić, R. 2001. “Karbonizirani biljni ostaci iz prapovijesnog lokaliteta u Novoj Bukovici na položaju Sjenjak /Carbonized plant remains of the prehistoric locality in Nova Bukovica on the site Sjenjak.” Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 18: 79–82.

- Šoštarić, R. 2004. “Archaeobotanical Analysis of Findings from Torčec – Gradić Archaeological Site.” Podravina 3 (6): 107–115.

- Šoštarić, R., H. Potrebica, N. Šaić, and A. Barbir. 2016. “Prilog poznavanju halštatskih pogrebnih običaja – arheobotanički nalazi tumula 13 i 14 iz Kaptola kraj Požege.” Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 33: 307–315.

- Spurr, M. S. 1983. “The Cultivation of Millet in Roman Italy.” Papers of the British School at Rome 51: 1–15.

- Stika, H. P. 2000. “Pfanzenreste aus der Höhensiedlung der späten Urnenfelderzeit am Kulm bei Trofaiach.” Fundberichte Österreich 38: 163–168. Wien: BDA.

- Stika, H.-P., and A. G. Heiss. 2013. “Plant Cultivation in the Bronze Age.” In The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, edited by H. Fokkens and A. Harding, 348–369. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Teržan, B. 1999. “An Outline of the Urnfield Culture Period in Slovenia.” Artheološki vestnik 50: 97–143.

- Urem-Kotsou, D. 2017. “Storage of Food in the Neolithic Communities of Northern Greece.” World Archaeology, doi:10.1080/00438243.2016.1276853.

- Valamoti, S. M., E. Marinova, A. G. Heiss, I. Hristova, C. Petridou, T. Popova, S. Michou, et al. 2019. “Prehistoric Cereal Foods of Southeastern Europe: An Archaeobotanical Exploration.” Journal of Archaeological Science 104: 97–113.

- Valamoti, S. M., C. Petridou, M. Berihuete-Azorín, H.-P. Stika, L. Papadopoulou, and I. Mimi. 2021. “Deciphering Ancient ‘Recipes’ from Charred Cereal Fragments: An Integrated Methodological Approach Using Experimental, Ethnographic and Archaeological Evidence.” Journal of Archaeological Science 128: 105347.

- Van der Veen, M. 1992. Crop Husbandry Regimes: An Archaeobotanical Study of Farming in Northern England 1000 BC – AD 500. Sheffield: J.R. Collis Publications.

- Wallace, M., G. Jones, M. Charles, E. Forster, E. Stillman, V. Bonhomme, A. Livarda, et al. 2019. “Re-Analysis of Archaeobotanical Remains from Pre- and Early Agricultural Sites Provides no Evidence for a Narrowing of the Wild Plant Food Spectrum During the Origins of Agriculture in Southwest Asia.” Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 28: 449–463.

- Winterhalder, B., C. Puleston, and C. Ross. 2015. “Production Risk, Inter-Annual Food Storage by Households and Population-Level Consequences in Seasonal Prehistoric Agrarian Societies.” Environmental Archaeology 20: 337–348.

- Zavodny, E., B. Culleton, S. Mcclure, D. Kennett, and J. Balen. 2017. “Minimizing Risk on the Margins: Insights On Iron Age Agriculture from Stable Isotope Analyses in Central Croatia.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 48: 250–261

- Zavodny, E., S. McClure, M. Welker, B. J. Culleton, J. Balen, and D. Kennett. 2019. “Scaling Up: Stable Isotope Evidence for the Intensification of Animal Husbandry in Bronze-Iron Age Lika, Croatia.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 23: 1055–1065.

- Zohary, D., and M. Hopf. 2000. Domestication of Plants in the Old World-The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley. New York: Oxford University Press.