ABSTRACT

Guidelines and instructions for Environmental Impact Assessment and Strategic Environmental Assessment (together referred to as EA here) are developed to improve the quality of legal requirements’ implementation and to support EA procedure accomplishment. However, to date, it has not been checked whether they are useful for practitioners. Therefore, the aim of the study underlying this paper was to verify, based on the experience of Polish EA experts, whether guidelines and instructions are useful in their everyday work. A qualitative study comprising of a questionnaire survey and interviews tested whether (1) EA practitioners know and use the Polish and EU guidelines, (2) how EA practitioners evaluate the validity and usefulness of such instructions, and (3) in which areas there is a lack of instructions and guidelines. The results show a low level of knowledge of national and EU handbooks. Those guidelines focusing on legal procedures, road investments and designing animal passageways are considered to be the most useful. Moreover, practitioners indicate that EU guidelines should be translated into Polish. Most important for practitioners is the linking of guidelines with the EA procedure, so that they can become a platform for dialogue of all stakeholders.

Introduction

The effective use of environmental assessment (EA) procedures, especially strategic environmental assessment and environmental impact assessment (SEA and EIA) is pivotal for the conservation of natural resources, and thus for people being able to live in a qualitatively good environment. At the same time, principles of sustainable development are implemented through EA (Fischer Citation1999; Morgan Citation2012; Runhaar et al. Citation2013; Nowak Citation2014). EA of a planned investment or development is a demanding process. Its effectiveness depends on numerous factors, including human factors such as knowledge, experience, and the commitment of experts who perform the assessment (Lackowski et al. Citation2004; SKOŚ Citation2013). Other factors include the availability and suitability of data (Lei and Hilton Citation2013). The World Bank (Citation2012) reported that poor EIA documents are the products of poorly trained EIA practitioners. To a large extent, the effectiveness also depends on the investor, and on the public administration issuing an environmental decision (Middle and Middle Citation2010).

The implementation of EA is supported by the Directorate-General for the Environment of the European Commission on the European Union (EU) level and by the General Directorate for Environmental Protection in Poland through the preparation of instructions and guidelines concerning EA. On the websites of those institutions the materials are published that are intended to simplify the implementation of the EIA and SEA Directives and the domestic law for practitioners and other users of EA.Footnote1

The purpose of the research underlying this paper was to study whether (1) Polish EA practitioners know and use EU and Polish guidelines, and (2) how Polish EA practitioners evaluate their validity and usefulness. In addition, a third aim was (3) to identify the areas in which there is a lack of instructions and guidelines available to EA practitioners. In this study, the word ‘useful’ was understood in accordance with the Polish Language Dictionary, as ‘helpful in something’, and the term EA refers to both EIA and SEA procedures (Nicolaisen and Fischer Citation2016).

The first part of the paper describes the state of the art of the research concerning the effectiveness of EA, the use of guidelines and instructions as a support when conducting EA, as well as the importance of these guidelines for EA practitioners. This is followed by a section on research methodology. Thereafter, the outcomes of the research including the identification of areas in which practitioners require assistance are presented. This is followed by a conclusions section, which provides an overview of possible ways to improve the EA support system.

Effectiveness of EA

The assessment of EA effectiveness has been the subject of previous studies (Fischer Citation2002, Citation2007; Cashmore et al. Citation2009; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013; Rozema and Bond Citation2015; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). Changes over time in the understanding of EA have also been discussed (Morgan Citation2012; Drayson et al. Citation2017). According to Chanchitpricha and Bond (Citation2013), EA is based on procedural, substantive, transactive and normative pillars. Each of these four pillars covers a different scope of the assessment procedure. Procedural effectiveness addresses the question of ‘What procedures/principles were used in practice?’ and checks the results gathered from practice. The assessment of substantive effectiveness looks at ‘What objectives were met?’ and checks if they were met at all. Transactive effectiveness deals with ‘How were the resources managed to support objectives?’ and evaluates the resource management system. Finally, normative effectiveness checks ‘What normative goals were reached?’, and the output of this assessment is reflected in a better understanding of them. Recently, an additional fifth component was proposed, a so-called multidimensional effectiveness assessment, which links the four basic pillars (Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). Depending on the scope of the research, different effectiveness assessments can be analysed, both separately (van Doren et al. Citation2013) or in a cumulative way, by integrated environmental decision-making (Theophilou et al. Citation2010).

EA is a common tool used across the EU. However, its implementation varies in the different member states as implementation depends on specific national conditions. Such conditions include, for instance, the structure and quality of public bodies responsible for the procedure and the availability of national legislation (Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; Retief Citation2007a; Retief, Citation2007b; Buuren and Nooteboom Citation2009; Stoeglehner Citation2014; Heinma and Põder Citation2010; Runhaar et al. Citation2013; Zvijáková et al. Citation2014; Phylip-Jones and Fischer Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to verify whether aspects of ineffectiveness are generic (encountered in multiple countries) or if they are merely national issues, such as insufficient information to stakeholders (Balram et al. Citation2003; Rozema and Bond Citation2015; Ludovico and Fabietti Citation2018). Moreover, the effectiveness of the EA system is strongly linked to governance mechanisms (Arts et al. Citation2012; Lyhne et al. Citation2017).

Guidelines and instructions for the implementation of EA

Effectiveness can be supported by guidelines and instructions for practitioners (Hickie and Wade Citation1998). How EA is supported by guidelines is, therefore, a valid research question.

To date, the problems associated with using guidelines and instructions in EA have not been widely researched. Over 15 years ago, Balfors and Schmidtbauer (Citation2002) concluded that EA guidelines should be considered a positive development as they promote further application of EA in regional planning. A global trend in urgency of developing guidelines was observed since then by, for example, De Montis (Citation2013), resulting in including environmental sustainability in local planning process (De Montis et al. Citation2014b). However, EA guidelines are often poorly prepared or they are not prevalent in EU member states (De Montis et al. Citation2014b). It has been suggested that EA guidelines should contain, among other things, an outline of the complete legislative framework, description of participation strategies, advice on the comparison and assessment of alternatives, suggestions on the establishment and maintenance of efficient monitoring systems, checklists for assessing EA quality and drafting of an EA report, as well as suggestions of a general framework for the drafting of an EA report (De Montis et al. Citation2016). An important question arising is how often existing EA guidelines are used by practitioners and are they perceived to be helpful?

The legal background of guidelines and instructions for EA

The usefulness of EA guidelines is to a large extent dependent on judicial compliance, which in Poland is the application of EU environmental law. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) stressed the need for a shared (common) understanding by all member states of the concepts used in the directives concerning EA being an instrument with a normative character. Hence, achieving the abovementioned pillars of assessment requires also common understanding of terms used in the EA Directives. Especially normative effectiveness understood as the maximisation of the benefits of the EU’s environmental legislation (recognised as one of the objectives of the 7th Action Programme Living Well within the Limits of our Planet (European Parliament Citation2012) needs, among others, cooperation with experts. The European Commission recognises those need pointing out that professional networks and expert groups are systematically involved, in particular, in developing – among others – guidance documents. (A Europe of Results Citation2007). The normative effectiveness of assessment lays not only upon the use of guidelines and instructions created by the experts, but also documents drawn up as part of the case-law of the CJEU and the authentic interpretation made by EU institutions. Guidelines and instructions can be a collection of best practices, whereas the role of case-law of the CJEU and of EC guidelines is different in nature, because case-law of the CJEU is an extra element governing the application of law in EU member states. It lays down the interpretation of EU law concepts, and the court’s activity ‘ensures that in the interpretation and application of the Treaties the law is observed’ in accordance to art. 19 of the Treaty on European Union. On the other hand, the role of the guidelines formulated by the European Commission with regard to the authentic interpretation of its own (co-)made regulations can be viewed against the backdrop of the judgement in case C-322/88 regarding the interpretation method of all acts from the European Commission as a so-called ‘soft law’. In this case, the CJEU found that although recommendations are measures that are not binding even to those whom they concern, they cannot be seen as producing no legal effect. Hence, national courts are required to take the recommendations into account when adjudicating disputes, especially when recommendations affect the interpretation of national measures adopted as part of their implementation or when they are complementary to binding EU laws (Grimaldi Citation1989). This statement clearly calls for a more profound familiarity with guidelines and instructions signed by the European Commission among the assessors and law enforcement bodies.

Methodology

A qualitative research approach was chosen for this study, including surveys and subsequent interviews with professional stakeholders.

Study design

The assessment of understanding and usefulness of instructions and guidelines concerned publications from web pages of the European Commission and the General Directorate for Environmental Protection in Poland. Both are credible sources on information for EA practitioners in Poland. The assessment was applied to all 14 EU and 20 Polish publications placed on web pages of European Commission,Footnote2,Footnote3 and the General Directorate for Environmental Protection in Poland.Footnote4 Subsequently, the authors use publication codes presented in (Polish publications) and (EU publications).

Table 1. The list of instructions and guidelines published in Polish that are included in the research on their understanding and usefulness within EA (full title and source in Appendix 1).

Table 2. The list of EU instructions and guidelines included in the research on their understanding and usefulness within EA (full title and source in Appendix 1).

Study participants and ethics

The study covered only experts experienced in the preparation of EAs. Participants were selected by suitable sampling approach. The request to join the research was sent exclusively to companies and experts that practice EA. In Poland there are no statistics kept on the market of EA experts. Their number was estimated on the basis of a telephone interview with six randomly selected experts. Against this backdrop, it was alleged that there are approximately 100–150 companies dealing with EA, with an average of 3–5 experts working in each company, which results in a rough estimation of 300 to 750 experts in Poland. Next, during the screening of webpages, the list of EA concerning companies and experts was made. This list included 120 addresses of companies and 20 Polish EA experts. These were invited to take part in research.

The online survey was completed by 42 persons. The response rate to the questionnaire was around 30%. The research, therefore, covers between 6 and 12% of the statistical population. Most experts have a university qualification in environmental protection (14 persons) or environmental engineering (10 persons) as well as spatial management (8 persons); 6 have two degrees. Almost half have more than 10 years of work experience; over a quarter have been into EA for over six years, and only two persons are just gaining experience in the field (less than two years). Three-quarter of the surveyed experts use guidelines and instructions. Half of them declared experience in managing EIA projects and procedures. Most of the participants were employed in private consulting companies or in scientific and research institutions. The surveyed also declared that they were working as independent experts (five persons).

Additional individual interviews were conducted with selected experts (3 females and 1 male), who had over 10 years of experience and were in charge of the complete EA process, and who agreed to take part in the survey .

Table 3. Profiles of individual interview participants.

The companies and experts were sent an e-mail which explained the research purpose and requested to complete the questionnaire. The Association of Environmental Assessment ConsultantsFootnote5 was also requested to spread the survey among specialists. The participation in the survey was voluntary, and submitting a response was taken as informed consent. Informed consent was not sought from the professionals, as the return of the questionnaire implied consent. Anonymity was ensured, as participants were not required to provide their names or the names of their institutions. The questionnaire included information about the possibility to contact the principal investigator, if a participant had any questions or doubts. Four respondents contacted the principal investigator for more detailed information.

Data collection

The research was conducted with the use of a questionnaire (Appendix No. 2) which was prepared using Google Forms and was made available online through the Google platform. The questionnaire was online from 10th to 25th of January 2018. The survey was conducted in Polish and the estimated time of completing equalled about 15 min.

The questionnaire consisted of 11 closed questions written in Polish (see Appendix 2). The first part (questions 1–5) applied to respondents characteristics (education, professional experience, areas of specific expertise), the subsequent part (questions 6–9) included the assessment of guidelines and instructions and the last part allowed experts to state their needs in the scope of guidelines development. The collection of expert opinions via a survey concerning the usefulness of environmental factors, has previously been successfully conducted by, for example Dahlitz and Morrison-Saunders (Citation2014) and De Montis (Citation2014a, Citation2016), who studied the implementation of SEA for landscape and master planning. The research survey was prepared in accordance with the recommendations on conducting surveys (Babbie Citation2015; Krok Citation2015; Matejum Citation2016). Questions asked allowed to check the familiarity of participants with particular guidelines and also to provide an assessment of the understanding and usefulness of each publication.

At first, participants were asked to indicate if they were familiar with a given publication (questionnaire included full title and front cover image). The next question assessed whether the content of the publications was up-to-date. For the rating, a 3-point Linkert scale was used (1 – up to date, 2 – partly outdated, 3 – outdated). The validity evaluation is of great importance for the further assessment of the usefulness of publications. In the next step participants were asked about their rating of guidelines’ usefulness. The answers were given within 4-point Osgood scale, where 1 stood for useless and 4 for useful.

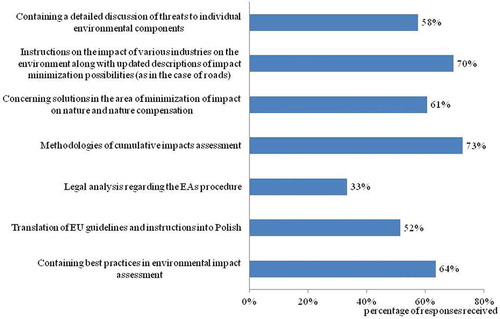

The last section of the survey dealt with the recognising of the expert’s needs and recommendations. As some EU guidelines are not yet translated into Polish, the questionnaire also inquired whether the use of the publications in English caused any difficulties to the participants. In the last part of the survey, the respondents could give their recommendations regarding EA guidelines and instructions in general. First, they were asked if the system of supporting EA through guidelines and instructions should be developed. Thereafter, they were requested to indicate what studies (instructions) were missing. Question number 10, regarding the areas in which guidelines should be further improved, was semi-open. The participants were allowed to choose from the various multiple choice options .

Table 4. Which guidelines should be further improved? – Question 10.

The second stage of data collection concerned individual interviews. Participants were informed about the purpose of the survey, which lasted about 90 min, and was conducted in person in the company office (two participants) or via telephone (two participants). During the interviews notes were made. The interview was semi-structured and it included main topics as well as additional questions . Results acquired from the interviews were used as supplementary information during the interpretation of survey outcome.

Table 5. Questions asked during the individual interviews.

Data analysis

Google Forms is featured with an integrated functionality allowing data to be exported to Microsoft Excel. The datasets were analysed in Excel, then explored and visualised in the Tableau intelligence system (Szewrański et al. Citation2017). The analysis covered the recognition of the experts’ awareness of particular publications. Next, the knowledge of thematic publications was checked among experts from individual specialties. Participants were divided into groups of experts in (1) environmental protection and biodiversity, (2) climate change impact and adaptation and (3) experts acting as coordinators. These fields of expertise were chosen, because coordinators should have a better understanding of procedural guidelines, and biodiversity and climate change are topics currently essential to EU policy (Borras et al. Citation2015; Skjærseth Citation2018).

Results

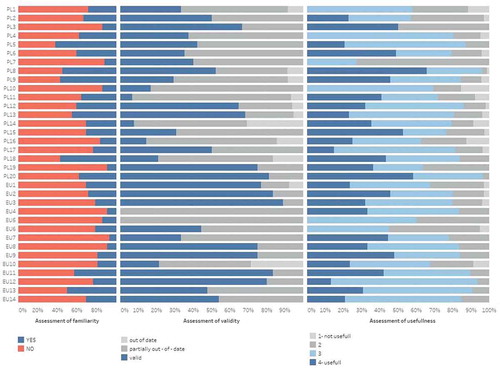

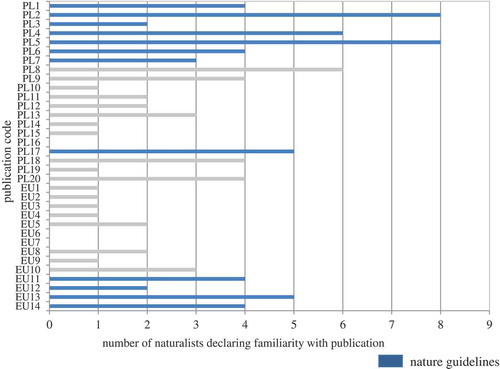

In the following section the results of the survey are presented. First, the familiarity with guidelines and instructions is dealt with, followed by analyses of the validity and usefulness, concluding with recommendations by the participants. The second part includes outcome from interviews with experts. The assessment of familiarity, validity and usefulness of guidelines is shown in . Validity and usefulness were only assessed by participants who declared their familiarity with publications (blue colour in the first column).

Figure 1. Assessment of familiarity, validity and usefulness of Polish (PL1-PL20) and EU (EU1-EU14) guidebooks.

Familiarity with guidelines and instructions

The question about familiarity with a particular publication had acted as an ordering tool in order to subsequently ask questions only on guidelines practitioners were familiar with.

Environmental experts were not familiar with all of the 20 Polish and 14 EU publications selected for the study . The Polish reports were slightly better known. Most of the participants (62%) were familiar with PL5. PL9 and PL18 were both known by 57% of the respondents. Half of the respondents were familiar with PL13. The least-known publications were: PL3, PL7, PL10, PL16 and PL19 (known to 10–20% of the participants).

The survey revealed even less familiarity with the corresponding EU publications. Only the EU13 was known to half of the respondents. About 43% of them also declared familiarity with the EU11. These documents are available in Polish, and were also made available on the website of the General Directorate for Environmental Protection. 30% of the respondents were familiar with the EU14 and only 20% knew the guidance document EU6; both are available in Polish.

Generally speaking, knowledge of the guidelines amongst EIA practitioners in Poland is poor . At the same time, more than 75% of the respondents declared that they used guidelines and instructions in their professional practice .

Over half of the respondents confirmed that non-Polish (mostly English) EU publications are an obstacle . Only 10–30% of the participants expressed the need of access to EU guidelines and instructions in Polish .

Figure 4. Declared knowledge of the guidelines concerning climate and climate change adaptation by climate experts (16 persons).

The guidelines and instructions cover different areas and topics. Analysis results show that natural scientists, climate experts and EA coordinators tend to have a good understanding of guidelines from their fields of interest.

shows natural scientists’ knowledge of individual publications. Blue colour indicates nature-themed publications. It is Naturalists are more familiar with this set of publications than other experts. They also ranked the usability of publication PL5 On Managing Natura (Citation2000) in the assessment of environmental impact relatively high (6 from 7 experts familiar with this publication considered it useful). They admitted to having poor knowledge of EU publications, with the exception of those that have nature-themed content (about half of the experts). Similar results were obtained in the areas of climate change impact and adaptation to climate change . Guidelines were well-known to experts working in these areas.

Figure 5. Declared knowledge of the guidelines by experts in fauna, flora, biodiversity and protected areas (9 persons) (nature-themed guidelines).

Some of the guidelines address administrative procedures and legal analyses (PL9, PL11, PL14, PL15, EU1-EU6 and EU9). Such publications should be particularly known to EA coordinators. However, it was found that these showed poor knowledge of the listed documents. A total of 15 out of 22 coordinators said they knew report PL9. This may be attributed to the fact that experts preparing EA reports focus only on their part of the project only.

Validity and usefulness

The majority of Polish instructions were rated as partially outdated (14 publications) by over half of the respondents. The documents PL19 and PL20 were assessed as being most valid. Only a few Polish guidelines were assessed as useful (3 and/or 4 points). The respondents considered PL8 (Designing passageways for animals) and PL20 (Assessment of flowing waters) as the most useful in EA, while report PL19 (Technological guidelines of transport infrastructure) was rated as the least useful.

Among EU guidelines, high validity is attached to EU1, EU2, EU3, EU11 and EU12 (EU11 and EU12 are also available in Polish). None of EU publications was found to be outdated. The EA experts found EU12 (Integrating Climate Change and Biodiversity) as being the most useful, along with the EU guidelines that were translated into Polish: EU13 (Assessment of plan and projects affecting Managing Natura Citation2000) and EU14 (Managing Natura Citation2000 sites. The provisions of Article 6).

In the case of several publications, only a limited familiarity with the content was reported. Yet, experts who were more aware of those guidelines rated their usefulness positively. Publications known only to a few experts, but assessed as useful, are PL2 (Managing of wetlands birds), PL3 (Bat species in Poland) and PL20 (Assessment of flowing waters).

Expert recommendations on future development of EIA support

Nearly 80% of the respondents were of the opinion that the existing guidelines and instructions do not fully support the EA process in Poland. The experts participating in the research () expressed the need of developing instructions discussing impact of various industries on the environment that would contain relevant descriptions of impact minimisation (including natural compensation) (70% of respondents). Moreover, experts pointed to a lack of instructions containing detailed characteristics of threats to individual environmental components, such as air, soil, nature, human health, water, landscape and others (57%). It is also important to disseminate best practices in the field of EA (raised by half of the respondents). Over 72% of respondents pointed to the necessity of developing guidelines dealing with the methodology of assessing cumulative impacts. Single practitioners also articulated the need of updating existing guidelines in order to prepare legal analyses within EA and to offer case study descriptions of model EA procedures for local investments in Poland. Even the experts who stated that they did not use available guidelines recognised the need to create and improve them.

Individual ratings by EA practitioners – interview results

Three experts pointed at the need to create new guidelines for procedural support and detailed instructions for how to assess various specific activities on the environment (). A great deal of emphasis was placed on guidelines’ quality. It was also suggested that guidelines are of particular high value when they become a starting point for dialogue between investor and authority which issues an environmental decision. One expert noticed that constraints of EA are provided within legislation, but that generic guidelines are ‘of no use’, as each case requires an individual approach.

Table 6. Results of expert interviews (own elaboration).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that EA practitioners in Poland have little knowledge on the guidelines that are available to them. This low level of expert familiarity with publications was expected, though. The results of the survey can also be used for further research into why Polish experts do not use EA guidelines, even though access to these materials is easy and free of charge. This study is the first of its kind, and no similar research currently exists elsewhere. Because of that, there is no possibility of conducting a comparative discussion on how EA practitioners abroad use and perceive the available guidelines, which may also be linked to being able to speak and understand foreign languages. The limited knowledge of EU guidelines is connected with identified difficulties concerning the use of English or potentially other language publications. During the interviews, experts emphasised that the cost of making translations should not be a problem in Poland. In their view, EU guidelines that are recommended by the European Commission should also be published in Polish. Insufficient knowledge of existing guidelines could also arise from the fact that publications available in Poland have not been linked to the impact assessment system in a sense that their use is not recommended by the authorities responsible for the EA procedures and for deciding on the scope of reports and forecasts. This seems to contradict the fact that these publications are drawn up by public bodies. It seems that when competent authorities pointed to the use of publications in impact studies during the scoping procedure, this could have had a positive influence on both, the quality of the studies and the long-term quality of guidelines. This is also confirmed by the positive assessment of the usefulness of guidelines with regards to explaining legal regulations and proceedings (PL9, PL14). This is particularly the case when it comes to recommending research methods by authorities. Indeed, the use of guidelines and instructions is not required by, or similar to, law. Nevertheless, nothing should prevent competent authorities from recommending such research methods that they deem to be useful. The scientific community develops methods supporting EA (Kazak et al. Citation2017; Szafranko Citation2017). However, including such methods in guidelines and recommending them to EA authorities promotes their application and contributes to the improvement of the experts’ output quality. It appears that guidelines that can become the basis for dialogue between investors and authorities issuing the environmental decision report, and that are respected by all participants, are likely to be particularly useful.

Survey and interview results clearly show that there is a need for developing detailed guidelines that support EIA for various types of projects. Practitioners also suggest that guidelines should provide advice on how to minimise negative impacts. This is consistent with recommendations regarding the construction of guidelines formulated by De Montis et al. (Citation2016).

Researchers from all over the world are working on establishing methods for EIA of different types of projects. For example Rasheed et al. (Citation2017) laid down guidelines concerning a case of a fishing port in a semi-enclosed water body, and Karlson et al. (Citation2014) pointed to the necessity of preparing guidelines for road ecology, including standards indicating acceptable levels of impact on ecological processes. We suggest that there is a need also intensify endeavours in Poland and at the level of the EU.

It is clear that guidelines and instructions cannot be imposed as the only possible way of doing things. EA experts remain responsible for the selection of the most relevant methods and analyses. However, there is also a need for guidelines to be updated regularly. This was suggested by most experts.

When analysing the survey results, it should be noted that the contents of a given publication is linked, to a certain extent, to the number of issues experts face in their analyses and during administrative proceedings. A good example is the high familiarity with and knowledge of publications on EA concerning Managing Natura (Citation2000) (PL5) and water (PL20) or the high scores for instructions on transport (PL18), and especially the construction of crossings for animals (PL8). These are the best-known guidebooks, and, in addition, the PL8 publication is considered as one of most useful in practice. A high level of detail and numerous case studies made this guidebook very popular among EA experts. There is an obvious conclusion that it may be an example of a properly designed guideline, which may be used as a source of inspiration for making new or updated guidelines.

On the other hand, publications on the construction of animal crossings are found to be very useful both, at the stage of developing recommendations on project’s impact minimisation and in cooperation with designers. This example demonstrates that from the EIA practitioner’s point of view guidelines and instructions are needed that can deliver a direct application in the process of EA, whether in the assessment of specific impacts or at the procedural stage.

It should also be noted that many publications offer general knowledge, which is often copied or transferred to and from other similar documents. The methodologies described there are often far from real practice (for instance, they fail to take account of access to data or provide a very short time to perform the assessment) and, consequently, discourage the use of such instructions. One of the experts indicated that the handbook available on the market mostly focuses on the validation of impacts by suggesting the manner of their presentation, while for practitioners the most burning problem is the assessment or how to propose adequate measures to minimise identified impacts. The development of instructions for specific industries or sets of impacts is more challenging and certainly much more costly. However, the results of the current study showed that specialist publications containing proposals of solutions (for instance, PL2 (Monitoring of wetland birds), PL8 (Designing passageways for animals), PL18 (Good practices for preparing environmental analyses for roads), PL12 (Mitigation climate change), PL13 (Preparing investments considering climate changes) and PL20 (Assessment of flowing waters)) are seen as useful in EA. Moreover, the guidelines known to a few experts only (PL2 (Monitoring of wetland birds) and PL20 (Assessment of flowing waters) are ranked as useful, too. It can be concluded that the enhancement of knowledge on those publications could lead to improvement of EA analyses quality.

Besides, it is not unreasonable to consider the establishment of a European system of environmental standards (as is the case with construction standards) that would put together the various methods of studying and assessing environmental impacts. The authorities could refer to specific standards, which would oblige contractors to comply with them. Such a system would reorganise and standardise the approach to analysis and would ultimately have a positive impact on the quality of studies as it would require a precise, specific, and well-defined analysis. Similar conclusions were made by Baresi et al. (Citation2017), who indicated that the use of methodologies and data management could be better addressed in legislation and guidelines. This, however, can only be implemented at the EU level by creating universal standards while allowing individual member states to design their own national standards adapted to the specific nature or characteristics of the region.

To sum up, practitioners often emphasise those guidelines regarding procedural aspects as useful, meaning that these guidelines should be validated and developed further. Similar conclusions were made by Schijf (Citation2011), who suggested that specific EA guidelines are needed, since legal and procedural requirements differ from one administration to another. The Polish practitioners represented in this research underlined that guidelines should be detailed, constructed to tackle specific problems, geared up with assessment methodology and possible ways of minimising the negative impacts. Similar suggestions were also made by Noble et al. (Citation2012) whose results indicate that more detailed operational guidance is needed at the practitioner level on how to make sound methodological choices and how to select the best available methods for the SEA tier and context at hand.

Conclusions and future work

The understanding and usefulness of Polish and EU guidelines was evaluated by Polish EA experts. Views concerning their expectations of the support of the EA process though publications acting as guidebooks were also collected. It was found that Polish EA practitioners are willing to use guidelines, as long as these guidelines meet the following requirements:

Guidelines should solve specific problems without repeating well-known and obvious information, and should focus on detailed solutions that are helpful in minimising negative impacts;

Guidelines should recommend methods for impact assessment, providing information on availability and source of required spatial and environmental datasets;

EU Guidelines should be translated into Polish, because of difficulties with the use of the English (or other) language in publications;

Guidelines should be respected by all participants of EA procedure, in order to become a basis for dialogue between the investor and authority stating the environmental conditions for given investment or implementation of strategic document.

The main conclusion of this study is that the knowledge of guidelines, as well as their practical usefulness will increase if they act as a compact and reliable basis for cooperation between all participants of EA procedures. The creation of a stronger link between guidelines and the EA system should be stimulated, for instance, by recommendation of their use. Polish national law on EA requires from authorities to indicate the scope of reports and methodologies. Authorities can point to guidelines and instructions which should be used during environmental assessment procedures. If such solution would be brought to life, it would require the change in guidelines designing approach. However, it is to be noted that the implementation of this could bring unwanted implications, such as indication of methods which could be advantageous for one of EA participants. Furthermore, ideally, guidelines should be addressed to particular groups of experts, which means that the substantive scope of a guideline should be of high level.

There is a need for further research in order to identify the cause of the poor awareness level among EA practitioners. This low level could result from the fact that the use of guidelines is not obligatory and experts already have sufficient professional knowledge to conduct efficient impact assessments. It should also be studied if there is a possibility of creating guidelines that could be recommended for use by all participants of the EA procedure. It ought to be taken under consideration on how to prevent the preferred solutions or monopolised services, in what teams work on such guidelines in order to keep them unbiased. In addition, it should be checked whether guidelines (especially national guidelines) are still up to date with recent scientific progress. The beginning of a discussion on the creation of useful guidelines is an important step towards the improvement of the effectiveness of EA.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. They also wish to thank practitioners who participated in the survey and individual interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Notes

1. The list of guidelines included in the research is in and (shortened), full title and source in Appendix 1.

5. The Association of Environmental Assessment Consultants gathers experts in environmental impact assessment. They are lawyers, environmental engineers, biologists, hydrologists and representatives of other sectors involved in the EA process. The main goal of the association is to work towards the improvement of the quality of EA. Currently, the organisation associates about 50 people (http://www.skos.org.pl/index.php).

References

- A Europe of Results 2007. Communication from the Commission - A Europe of Results – Applying Community Law/COM/2007/0502 final */, 52007DC0502.

- Arts J, Runhaar HAC, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Vincent Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in The Netherlands and the UK. J Env Assmt Pol Mgmt. 14(4):1250025.

- Babbie E. 2015. The basics of social research. Boston: Cengage Learning.

- Balfors B, Schmidtbauer J. 2002. Swedish guidelines for strategic environmental assessment for EU structural funds. Eur Environ. 12(1):35–48.

- Balram S, Dragicevic S, Meredith T. 2003. Achieving effectiveness in stakeholder participation using the GIS-based collaborative spatial Delphi methodology. J Env Assmt Pol Mgmt. 5(3):365–394.

- Baresi U, Karen J, Vella KJ, Neil G, Sipe NG. 2017. Bridging the divide between theory and guidance in strategic environmental assessment: a path for Italian regions. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 62:14–24.

- Borrass L, Sotirov M, Winkel G. 2015. Policy change and Europeanization: implementing the European Union’s habitats directive in Germany and the United Kingdom environmental politics. Environmental Politics. 24(5): 3 September 2015, 788–809. doi:10.1080/09644016.2015.1027056

- Cashmore M, Bond A, Sadler B. 2009. Introduction: the effectiveness of impact assessment instruments. Imp Assmt Project Appr. 27(2):91–93.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 43:65–72.

- Dahlitz V, Morrison-Saunders A. 2014. Assessing the utility of environmental factors and objectives in environmental impact assessment practice: Western Australian insights. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 33(2):142–147.

- De Montis A. 2013. Implementing strategic environmental assessment of spatial planning tools. A study on the Italian provinces. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 41:53–63.

- De Montis A, Ledda A, Caschili S. 2016. Overcoming implementation barriers: a method for designing strategic environmental assessment guidelines. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 61:78–87.

- De Montis A, Ledda A, Caschili S, Ganciu A, Barra M. 2014a. SEA effectiveness for landscape and master planning: an investigation in Sardinia. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 47:1–13.

- De Montis A, Ledda S, Caschili A, Ganciu M, Barra G, Cocco A. 2014b. Sea guidelines. A comparative analysis: first outcomes. J Land Use Mobility Environ Spec Issue. 321–330. http://www.jop.unina.it/index.php/tema/article/view/2484/2510.

- Drayson K, Wood G, Thompson S. 2017. An evaluation of ecological impact assessment procedural effectiveness over time. Env Sci Pol. 70:54–66.

- European Commission 2016, Legal Enforcement, Compliance promotion accessed 2018 Feb 8]. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/legal/law/compliance.htm

- European Parliament. 2012. Decision No 1386/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the council of 20 November 2013 on a general union environment action programme to 2020 ‘Living well, within the limits of our planet’. OJ L 354/171 32013D1386.

- Fischer TB. 1999. The consideration of sustainability aspects within transport infrastructure related policies, plans and programmes. J Environ Plann Manag. 42(2):189–219.

- Fischer TB. 2002. Strategic environmental assessment in transport and land-use planning. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB. 2007. Theory and practice of strategic environmental assessment – towards a more systematic approach. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB, Gazzola P. 2006. SEA effectiveness criteria equally valid in all countries? The case of Italy. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 26(4):396–409.

- Grimaldi 1989 Judgment of 13 December 1989, Grimaldi, C-322/88, ECLI:EU:C:1989:646, paragraph 3

- Heinma K, Põder T. 2010. Effectiveness of environmental impact assessment system in Estonia. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 30(4):272–277.

- Hickie D, Wade M. 1998. Development of guidelines for improving the effectiveness of environmental assessment. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 18(3):267–287.

- Karlson M, Mörtberg U, Balfors B. 2014. Road ecology in environmental impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 48: [2014 Sept]. 10–19.

- Kazak J, van Hoof J, Szewranski S. 2017. Challenges in the wind turbines location process in Central Europe – the use of spatial decision support systems. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 76:425–433.

- Krok E. 2015. Budowa kwestionariusza ankietowego a wyniki badań [The Structure of a Questionnaire and Research Results]. Studia Informatica [In Polish]. 37:37–55.

- Lackowski A, Lenart W, Wiszniewska B, Szydłowski M. 2004. Metodyka oceny oddziaływania na środowisko jako całość w procesie wydawania pozwolenia zintegrowanego. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Środowiska. http://www.ekoportal.gov.pl/fileadmin/Ekoportal/Pozwolenia_zintegrowane/poradniki_branzowe/opracowania/5._Metodyka_oceny_oddzialywania_na_srodowisko_jako_calosc_w_procesie_wydawania_pozwolenia_zintegrowanego.pdf,) in polish

- Lei L, Hilton B. 2013. A spatially intelligent public participation system for the environmental impact assessment process. ISPRS Int J Geo-Inf. 2:480–506.

- Loomis JJ, Dziedzic M. 2018. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness: a state of the art. Env Impt Assmt Rev. 68:29–37.

- Ludovico D, Fabietti V. 2018. Strategic environmental assessment, key issues of its effectiveness. Env Impt Assmt Rev. 68:19–28.

- Lyhne I, van Laerhoven F, Cashmore M, Runhaar HAC. 2017. Theorising EIA effectiveness: a contribution based on the Danish system. Env Impt Assmt Rev. 62:240–249.

- Managing Natura 2000. In: The provisions of article 6 of the habitats directive 92/43/CEE. European Communities: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; p. 2000.

- Matejun M. 2016. Metodyka badań ankietowych w naukach o zarządzaniu - ujęcie modelowe. In: Lisiński M, Ziębicki B, editors. Współczesne problemy rozwoju metodologii zarządzania. [Methodology of Survey Studies in Management Sciences: A Model Approach. In Lisiński M., Ziębicki B., eds. Contemporary Challenges of the Development of Management Methodology] [in Polish]. Cracow: Fundacja Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie; p. 341–354.

- Middle G, Middle I. 2010. The inefficiency of environmental impact assessment: reality or myth? Imp Assmt Project Appr. 28(2):159–168.

- Morgan RK. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Imp Assmt Project Appr. 30(1):5–14.

- Nicolaisen M, Fischer TB. 2016. Editorial: special issue on ex-post evaluation of environmental assessment. J Environ Assess Policy Manag. 18(01): 2016 Mar. doi:10.1142/S1464333216010018

- Noble BF, Gunn J, Martin J. 2012. Survey of current methods and guidance for strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(3):139–147.

- Nowak MJ. 2014. Strategiczna ocena oddziaływania na środowisko jako instrument zarządzania środowiskiem w wybranych polskich gminach (Strategic evaluation of the impact on envirnoment as an instrument in envirnoment managing in selected polish municipalities). Ekonomia i Środowisko [in polish]. 1(48):125–140.

- Phylip-Jones JFischer TB. 2015. Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) for wind energy planning: Lessons from the United Kingdom and Germany. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 50:203–212.

- Rasheed M, Mian S, Almasri M, Aubrey D. 2017. Guidelines for EIA of a fishing port in a semi-enclosed water body. Fresenius Environ Bull. 26(7):4504–4516.

- Retief F. 2007a. A quality and effectiveness review protocol for Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in developing countries. J Env Assmt Pol Mgmt. 9(4):443–471.

- Retief F. 2007b. Effectiveness of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) in South Africa. J Env Assmt Pol Mgmt. 9(1):83–101.

- Rozema JG, Bond AJ. 2015. Framing effectiveness in impact assessment: discourse accommodation in controversial infrastructure development. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 50:66–73.

- Runhaar H, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Arts J. 2013. Environmental assessment in The Netherlands: effectively governing environmental protection? A discourse analysis. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 39:13–25.

- [SKOŚ 2013] The Association of Environmental Assessment Consultants 2013. Report from the seminar (in Polish). http://www.skos.org.pl/pdf/sprawozdanie.pdf

- Schijf B. 2011. Developing SEA Guidance. In: Sadler B, Dusik J, Fischer TB, Partidário MR, Verheem R, Aschemann R, editors. Handbook of strategic environmental assessment. London and Washington (DC): Earthscan Publications Ltd; p. 487–500.

- Skjærseth JB. 2018. Implementing EU climate and energy policies in Poland: policy feedback and reform. Env Polit. 27(3):498–518.

- Stoeglehner G. 2014. Enhancing SEA effectiveness: lessons learnt from Austrian experiences in spatial planning. Imp Assmt Project Appr. 28(3):217–231.

- Szafranko E. 2017. Application of multi-criterial analytical methods for ranking environmental criteria in an assessment of a development project. J Ecol Eng. 18(5):151–159.

- Szewrański S, Kazak J, Sylla M, Świąder M. 2017. Spatial data analysis with the use of ArcGIS and Tableau systems. Lecture Notes Geoinf Cart. F3:337–349.

- The World Bank. 2012. Guidance notes on tools for pollution management. In: Getting to Green: a sourcebook of pollution management policy tools for growth and competitiveness. The World Bank Group. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ENVIRONMENT/Resources/Getting_to_Green_web.pdf

- Theophilou V, Bond A, Cashmore M. 2010. Application of the SEA directive to EU structural funds: perspectives on effectiveness. Env Imp Assmt Rev. 30(2):136–144.

- van Buuren A, Nooteboom S. 2009. Evaluating strategic environmental assessment in The Netherlands: content, process and procedure as indissoluble criteria for effectiveness. Imp Assmt Project Appr. 27(2):145–154.

- van Doren D, Driessen PPJ, Schijf B, Runhaar HAC. 2013. Evaluating the substantive effectiveness of SEA: towards a better understanding. Env Impt Assmt Rev. 38:120–130.

- Zvijáková L, Zeleňáková M, Purcz P. 2014. Evaluation of environmental impact assessment effectiveness in Slovakia. Imp Assmt Project Appr. 32(2):150–161.

Appendix 1.

List of the evaluated guidelines and instructions

PL – Polish guidelines and guidebooks, published by the General Directorate of Environmental Protection and other sector institutions (in polish)

EU – EU guidelines and guidebooks published on the website of the European Commission

Appendix 2.

Survey: Study on usefulness of guidelines and handbooks concerning Environmental Impact Assessment

Part I – General questions

Question 1: What is your educational qualification? (multiple choice)

●Biology

●Geography

●Environmental protection

●Environmental engineering/water engineering and management

●Forestry, agriculture

●Geology/mining

●Land management/spatial planning

●Other…

Question 2: Do you act as a team leader?

●Yes

●No

Question 3: In what institution do you work? (multiple choice)

●Private consulting company

●As independent expert

●Research and development unit (university, institute)

●Other…

Question 4: What is your specialisation? (multiple choice)

●Flora, fauna, environmental protection

●Surface water, groundwater

●Noise

●Soil, land surface, natural resources

●Monuments and infrastructure

●People (health)

●Air

●Electromagnetic radiation

●Waste management

●Climate and climate change adaptation

●Landscape

●Other…

Question 5: For how many years you prepare Environmental Impact Assessment? (reports/forecasts)

●Less than 2 years

●2–5 years

●6–10 years

●More than 10 years

Question 6: Do you use guidelines/handbooks concerning Environmental Impact Assessment/Strategic EIA?

●Yes

●No

Part II – Next questions relate to guidelines and handbooks supporting Environmental Impact Assessment process that are recommended by General Environmental Protection Authority and other Polish institutions.

Question 7.1: Do you know this publication? (Publication title and front cover image)

●Yes

●No

Access to following questions is determined by given answer. If ‘Yes’:

Question 7.1a: How do you assess the validity of the publication content?

●Actual

●Partially outdated

●Outdated

Question 7.1b: How do you assess the usefulness of this publication during EIA or SEIA? (scale 1–4, where 1 – useless, 4 – useful)

●1

●2

●3

●4

Question 7 was duplicated 20 times with consideration of all publications listed in Appendix No.1 (PL1-PL20)

Part III – Next questions relate to guidelines and handbooks supporting Environmental Impact Assessment process that are recommended by European Commission

Question 8.1: Do you know this publication? (Publication title and front cover image)

●Yes

●No

Access to following questions is determined by given answer. If ‘Yes’:

Question 8.1a: How do you assess the validity of the publication content?

●Actual

●Partially outdated

●Outdated

Question 8.1b: How do you assess the usefulness of this publication during EIA or SEIA? (scale 1–4, where 1 – useless, 4 – useful)

●1

●2

●3

●4

Question 8 was duplicated 14 times with consideration of all publications listed in Appendix No.1 (EU1-EU14)

Question 9: Is the English language of guidelines and publications an obstacle during your work with them?

●Yes

●No

Part IV – Recommendations

Question 10: Do you think that existing guidelines and handbooks are sufficient enough to support conducting of impact assessment on environment for planned project or draft plan/program?

●Yes (I think, that there is no need of introducing additional guidelines and handbooks)

●No (I think, that the market of environmental impact assessments need a support through creation of new guidelines and handbooks)

Question 11: What kind of guidelines/handbooks is missing? (multiple choice)

●Including detailed discussion of threats for particular environment components

●Handbooks concerning impact of various industries on environment with constantly updated discussion on possibilities for mitigation of this impact (similar as the one concerning roads)

●Concerning solutions from the scope of minimising impact on environment and environmental compensation

●Methodology for conducting cumulative impact assessment

●Legal analyses concerning Environmental Impact Assessment procedure

●EU guidelines and handbooks translated to Polish language

●Including best practices in the field of environmental impact assessment

●Other…

Thank you for taking the time to complete the survey. The results from research conducted with use of this questionnaire will be sent to you via e-mail and will become a part of research paper presenting recommendations related to making of guidelines and handbooks.