ABSTRACT

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) is an important tool for making informed decisions about development projects to avoid or mitigate potential adverse impacts on the environment. Guidelines are prepared all over the world to facilitate consultants and stakeholders to meet the objectives of EIA and to prepare quality EIA reports. The Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency prepared environmental impact assessment guidelines for this purpose in 1997. However, the major issue is that, even after two decades, the guidelines have not been reviewed. This paper presents the outcome of research conducted on the contents and quality of the guidelines for the preparation of EIA reports. The methodology encompasses an extensive review of the literature as well as available guidelines and interviews with the selected consultants, using semi-structured interview schedules. Although the quality of current guidelines overall is found to be good, the likelihood they are followed is connected with them being updated regularly, taking on board opinion of EIA consultants and other stakeholders.

1. Introduction

Guidelines pertaining to various aspects of environmental impact assessment (EIA) have been widely prepared and have proliferated much within recent years (Kamijo and Huang Citation2017; Rebelo and Guerreiro Citation2017). Guidelines can be helpful to EIA process managers in assessing how far environmental assessment requirements are met by project proponents in EIA reports (Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013; Pavlyuk et al. Citation2017). Equally, guidelines can facilitate EIA consultants in preparation of EIA reports up to the mark or demonstrating good practice so as to satisfy officially endorsed environmental assessment requirements. Chanchitpricha and Bond (Citation2013) further argued that guidelines generally provide essential requirements that can possibly influence the quality of EIA. While doing comparative review of EIA across several jurisdictions, Wood (Citation1999) noted that EIA guidelines proved to be a valuable aid both, for those responsible for preparing EIA reports as well as for those reviewing them and making decisions. Pavlyuk et al. (Citation2017, p.15) in their study on the consideration and disclosure of uncertainties in EIA process in Canada, stated that:

Guidelines do not carry the same authority as regulations, but they can be used by EA reviewers, interest groups, or lobbyists to pressure proponents and practitioners to demonstrate good practice, and to challenge the EA process when certain practice-based expectations are not met.

However, use or implementation of guidelines has been a matter of concern for a long time. Two decades ago, Spooner (Citation1998) argued that the use of guidelines varied from one country to another, amongst institutions at different stages of impact assessment practice besides varying cultural, political, ecological and socio-economic contexts. This was based on a perception survey of user groups, comprising policy and decision makers, advisers, field officers and consultants. Where guidelines existed, often there was either lack of interest in their use or the consultants used them only occasionally. Guidelines were side-lined where these were neither mandatory nor practiced institutionally. The perceived roles of guidelines were often constrained by the context in which they were expected to be used and hence the ‘enabling environment’ had more influence on performance of impact assessment than the quality of the guidelines.

Based on a review of donor agency environmental assessment guidelines, Brew and Lee (Citation1996) concluded that the successful implementation of guidelines was dependent on the quality of their contents together with specific measures to determine their usefulness in practice. The latter requires establishing the official status of guidelines, arrangements for agency training and other staff in the use of guidelines, and provisions to monitor the quality of EIA practice and take remedial actions where needed.

Nonetheless, Waldeck et al. (Citation2003) found that guidance materials influenced the practice of consultants and they perceived these to be effective in enhancing the overall outcomes of the EIA process. The authors concluded that despite many shortfalls in EIA guidance materials identified by consultants, the perception of guidance materials as regulations or minimum standards, rather than documents purely offering advice, enhanced the quality of EIA in Western Australia. Despite the availability of guidelines with EIA process managers, as one of the tools to deliver better impact assessment all over the world, the guidelines are hardly subjected to any sort of evaluation and analysis regarding their quality, although exceptions are there (see for instance Waldeck et al. Citation2003; Spooner Citation1998; Brew and Lee Citation1996). Waldeck et al. (Citation2003) claimed that by the time of their research, there had been no studies aimed at determining the role of EIA guidance materials in achieving the fundamental objective of improving the quality of environmental assessment, and to strengthen the practice of EIA in general. Recently, Fischer and Yu (Citation2018) found the use of guidance material to be one of the key factors influencing the quality of sustainability appraisals.

Although the literature on evaluation of effectiveness of EIA systems in some developing countries, e.g. Egypt, Turkey, Tunisia, India and Syria, includes discussion pertaining to guidelines or at least reference to guidelines (Ahmad and Wood Citation2002; Momtaz Citation2002; Paliwal Citation2006; Haydar and Pediaditi Citation2010), in-depth studies focusing on the usefulness of EIA guidelines are almost non-existent. This paper presents the outcome of research conducted on the contents and quality of the guidelines with respect to facilitating the preparation of EIA reports. Based on the views of EIA consultants in Pakistan, various deficiencies in the guidelines have been identified. The findings of this research shall contribute to the as yet thin body of literature on this aspect and could be useful for the countries with similar socio-economic context. The next section elucidates the methodology adopted for this research. A critical review of the legal provisions and guidelines for EIA in Pakistan is then presented. It is followed by the results and discussion based on interviews of selected consultants and relevant literature. The last section presents conclusions and recommendations.

2. Methodology

To set the context, international literature pertaining to the coverage, quality and effectiveness of environmental assessment guidelines is reviewed. The legal provisions for EIA and Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency (Pak-EPA)’s guidelines for preparation and review of environmental reports along with sectoral guidelines for major roads are then reviewed and discussed to highlight the general characteristics, strengths and weaknesses. To validate the outcome of this review, views of EIA consultants were sought, using a semi-structured interview schedule. It consisted of various sections pertaining to the following aspects of the guidelines: utility, quality, expectations and review of EIA report. Perceptions about contents of the guidelines for preparation and review of an EIA report and the guidelines for major roads were also sought. The consultants were also asked to identify key omissions within the guidelines, impediments to implementation and need for revision. It is pertinent to mention here that the closed ended questions were designed, keeping in view the usage of guidelines in preparation of EIA report, its influence on decision making and operational stages of the projects, as suggested in the relevant literature (Spooner Citation1998; Waldeck et al. Citation2003; Pavlyuk et al. Citation2017). Keeping such questions as open ended would have led to diversified views and it would not be possible to consolidate them and calculate percentages of responses. However, the responding consultants were also asked to give reasons if they agreed/disagreed with some option or specific requirements of the guidelines were stringent or inadequate. The very reasons have been used for discussion/interpretation of results of the relevant question/section.

As far as the selection of interviewees is concerned, 70 EIA consulting firms were identified with help of EPA officials and national directory of environmental consulting firms in Pakistan. Profiles of these firms revealed that these were engaged in preparing EIA reports of different types of development projects. To conduct interviews of those who had experience of doing EIA of road sector projects, 35 EIA consultants were contacted in 2014 and 2018 using purposive sampling technique. In such situation, purposive sampling helps selecting the samples that are based on specific interests of the population and objective of the study (Hesse-Biber Citation2010). Face-to-face interviews with 11 consultants were initially conducted during 2014. Their views were updated in 2018. To augment the sample size, another 11 consultants were interviewed during this year, thus raising the total number of respondents to 22. The rest of the identified consultants did not respond.

3. EIA legislation and guidelines in Pakistan

EIA is a legal requirement for various projects in Pakistan. It has been subjected to several changes over the years. Its history begins with the Pakistan Environmental Protection Ordinance 1983. On 1 July 1994, EIA was made compulsory for all the new projects likely to cause adverse environmental impacts. The said Ordinance was converted into the Pakistan Environmental Protection Act in 1997 (GoP Citation1997). During the same year, the next major initiative was the documentation of policy and procedures for filing, review and approval of environmental assessments, including detailed guidelines. The package of guidelines was mainly associated with the following aspects:

Major roads

New townships

Industrial estates

Sewerage schemes

Public consultation

Water supply projects

Municipal waste disposal

Sensitive and critical areas

Major thermal power stations

Oil and gas exploration and production

National environmental quality standards

Major chemical and manufacturing plants

Preparation and review of environmental reports

The guidelines were meant to be helpful for all relevant stakeholders. Yet, these were unable to provide a legal basis for review of EIA reports, public hearing, decision making, steps of inspection and monitoring during the construction and operation phases of projects. Hence, these were later followed by Pak-EPA Review of EIA/ initial environmental examination (IEE) Regulations, 2000 (Nadeem and Hameed Citation2008; Nizami et al. Citation2011; Saeed et al. Citation2012). The Regulations categorically state that where guidelines have been issued, an IEE/EIA shall be prepared, to the extent that is practicable in accordance with the guidelines and the proponent shall justify any departure from the same. According to a review of these Regulations, this provision is vague, leaving room for different interpretations (Khawaja and Nabeela Citation2014, p.12).

3.1 Guidelines for the preparation and review of environmental reports

The general guidelines for the preparation and review of environmental report were prepared by Australian consultants in 1997, considering the relevant local laws, planning and environmental standards of the Pakistani Government, World Bank, IUCN and Asian Development Bank. More significantly, the UNEP Training Resource Manual and New South Wales EIS Guidelines, 1997 were also referred to.

The 46 pages long guidelines for the preparation and review of environmental reports (IEE and EIA) have been divided into eight sections including: introduction, commencing environmental assessment, assessing impacts, mitigation and impacts management, reporting, review and decision making, monitoring and auditing as well as project management. In addition to the list of references, two appendices presenting global, cross-sectoral and cultural issues in environmental assessment and an example of a network showing impacts linkages have been included. The guidelines also suggest some of the most frequently used methods of impact assessment namely: matrices, checklists and networks.

It is pertinent that the guidelines emphasize the need for integrated environmental assessment. Close cooperation between Environmental Assessment team and those working on other aspects of pre-feasibility and feasibility studies has also been suggested as being especially important, as indicated by the quote below:

Considering the strategic context is essential when selecting options for the proposal. Strategic mechanisms such as policies and plans which illustrate how the proposal has been developed, should be discussed in the Environmental Report so that the information is available and relevant. Any existing relevant cumulative or strategic environmental studies should be considered when formulating a proposal. Existing air and water studies, state of the environment reports and local and regional studies should be taken into consideration as applicable. (GoP Citation1997a, p.5)

The guidelines further suggest that the scope of an IEE or EIA should be determined, following the sectoral guidelines pertaining to the project, including checklist of potential impacts and mitigation measures on the analogy of ADB’s rapid environmental assessment checklist. The guidelines clearly spell out possible uses and steps in scoping. Roles of stakeholders in the scoping process, types of possible alternatives of project and detailed description of site selection principles are the other salient features of the guidelines. As far as impact assessment, mitigation and management are concerned, the guidelines elucidate with examples the various types of environmental and socio-economic impacts along with methods of impact identification viz. matrices, networks, overlays and geographic information systems, expert systems etc. (GoP Citation1997a; ADB Citation2003).

The guidelines also suggest the purpose of review and introduce a set of criteria for reviewing the quality of an EIA report. The purpose of the review is as follows:

To ensure compliance with TOR.

The objectives of the projects, baseline environmental conditions, possible alternatives, potential impacts, mitigation measures and monitoring arrangements are provided.

The provided information is accurate and technically adequate.

The environmental assessment was conducted appropriately, and taking into account the views of all parties concerned.

The information included in the report is reliable and understandable by the decision makers and the public.

The criteria for reviewing EIA reports include the following:

the executive summary should present significant and cumulative impacts, mitigation measures and monitoring arrangement.

the project description should be complete including all the aspects which can affect the environment.

project alternatives should be described.

baseline conditions should be adequately described in an easily understandable manner also indicating the quality of data.

significant impacts should be predicted and evaluated.

potential impacts that were expected at scoping stage but not found at this stage should be indicated.

mitigation measures should be proposed to minimize adverse impacts and enhancing benefits of the project.

environmental management plan (EMP) including arrangements for implementing mitigation measures should be proposed.

cost of implementing the proposed EMP and monitoring program should be estimated and included in the project budget.

local people should be involved during the EIA process and their concerns should be included in the report suggesting how those will be addressed.

the EIA report should be written with clarity, free of jargon and explaining technical issues in terms that are understandable to a nontechnical reader (Nadeem and Hameed Citation2006; p56; GoP Citation1997a, p32).

Some authors suggested that these criteria were subjective in nature, leading to a review of EIA as ‘an eye wash’ (Nadeem and Hameed Citation2008; Saeed et al. Citation2012) since the stated purpose of review uses phrases, like sufficient, correct, technically sound, relevant and reliable, to judge the quality of information provided in the EIA report. The quality indicators are more general than specific. While evaluating the EIA systems in Gulf Cooperation Council States, Al-Azri et al. (Citation2014) also observed that nonexistence of review criteria or guidelines was causing subjectivity in the review of EIAs, whereas internationally, EIA quality review criteria/packages have been suggested by different researchers and organizations. Those mainly include: Lee and Colley (Citation1990), Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA Citation2001) and the Impact Assessment Unit at Oxford Brooks University (CEC Citation2003; Glasson et al. Citation2012). Out of these, the review criteria by (Lee and Colley Citation1990), though rather old, are widely used (often in slightly adapted format) and tested in developed and developing countries (Retief Citation2007; Landim and Sánchez Citation2012; Phylip-Jones and Tb Citation2013; Kamijo and Huang Citation2017; Fischer and Yu Citation2018).

3.2 Sectoral guidelines for environmental reports – major roads

Roads constitute primary position for the movement of people and goods in Pakistan. The guidelines have been exclusively provided for major roads. Major roads within the scope of the guidelines comprise of motorways, roads lying within rural areas and major urban arterial roads. These mainly present sector overview, negative impacts and mitigation measures, management and monitoring, separate checklist for small and medium size road construction and expansion in urban areas, forest road construction and matters to be considered in initial site assessment. The list of negative impacts and suggested mitigation measures is quite comprehensive, including 17 different types of impacts on various environmental receptors and physical aspects. Some of the impacts which are not usually considered or given due consideration in the EIA reports of major roads in Pakistan have also been emphasized in the guidelines, for instance, change of land use, landscape and visual aspects, heritage, hazards, economic issues and cumulative impacts (GoP Citation1997b).

Additionally, the guidelines cover several other matters related to road facilities such as carrying out of works within the right of way, ensuring access to adjoining properties during road construction, specific traffic management issues, places of immense significance, such as administration buildings, booths, truck weighing facilities, service areas and construction maintenance compounds. The guidelines do not cover upgradation or major improvement of the existing and small new roads. Rather, these suggest that in case of roads that are of intermediate size, environmental report may need to be prepared depending upon significance of the impacts (Kamil and Khan Citation2014). Overall, the guidelines assist the proponent to include key environmental issues and mitigation measures whilst giving due consideration to the best suited alternative.

4. Results and discussion

This section presents the responses of the interviewed consultants. The responding consultants possessed three to 40 years of experience of doing EIAs of local, provincial and national level development projects (see ). In addition to the Pakistani guidelines, most of them were well conversant with environmental assessment guidelines of the World Bank, ADB, USAID, KFW Development Bank, JICA and WHO environmental quality standards.

Table 1. Gender and experience of interviewees.

4.1 Usage and role of guidelines in preparing EIA reports

A considerable proportion (59%) of the interviewees believed that the guidelines were generally followed by the consultants as far as possible (). Furthermore, 41% believed that the guidelines were followed only occasionally by consultants. This means that sometimes a significant proportion of consultants compromise on the procedure suggested in the guidelines. All interviewees, however, agreed that the guidelines are not ignored but followed to a varying extent. Similarly, most of the interviewees (86%) agreed that general EIA as well as road sector guidelines made a difference in improving the quality of EIA reports. Previous studies conducted in developed countries also found that the published guidelines may have a positive impact on the quality and level of scientific studies included in the EIA report (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2001). However, the same study also found that availability of time, financial resources, public pressure and expectations of regulating environmental agencies were other factors that influence the quality of EIA reports.

Table 2. Views on the usage, role and effectiveness of guidelines (% of respondents).

Almost all the respondents (95%) agreed that EIA report prepared after completely following the requirements of the guidelines for preparation and review of EIA report would contribute towards better management of environmental impacts of projects during operational stages. However, with regard to road and other sector guidelines this aspect is bit weaker and many respondents said they were unsure.

4.2 Good aspects of the guidelines and possible expectations from them

Many interviewees (60%) were of the view that the general as well as road sector guidelines provide basic frameworks, are comprehensive and address all aspects. These also suggest alternatives and maintaining a public hearing record. Overall, these act as key for conducting a successful EIA study by anticipating potential impacts of a project and reflect the important concerns of key stakeholders (see ) . The guidelines for other sectors, e.g. new townships, industrial estates, sewerage schemes etc. were duly considered as project specific, providing generic terms of reference of what should be addressed at the minimum.

Box 1: Good aspects of various guidelines.

Despite pointing out several positive aspects of the guidelines, most of the respondents agreed with possible expectations from them (see ). On the one hand, this is a good sign showing their willingness to follow good aspects of the guidelines. On the other hand, deficiencies were found in EIA reports prepared by most of the consultants (Shah et al. Citation2010; Nadeem and Fischer, Citation2011; Kamil and Khan Citation2014).

Table 3. Possible expectations from the general and sectoral guidelines (% of respondents).

Expectations mainly included: advocacy of best practices, respect for master plan provisions and consideration of cumulative impacts, requirements of other agencies of the government and international agreements/conventions pertaining to environmental protection. It needs to be stressed here that these expectations were expressed in workshops held in Islamabad in connection with the National Impact Assessment Program (Fischer and Nadeem Citation2014). Some of these were also identified by other authors (Spooner Citation1998; Waldeck et al. Citation2003; Pavlyuk et al. Citation2017).

As far as the guidelines for major roads and other sectors are concerned, a majority of consultants expected detailed discussion on sector specific social issues and impacts. Overall, they wanted guidelines that included a more specific format and contents of EIA reports. From the very nature of expectations, it appears that this is not a mere wish list but reflects the experience of consultants and difficulties faced while preparing and getting approval of EIA reports (see and ). These also point towards the fact that there is still a lot of room for improvement.

Box 2: Key omissions in various guidelines.

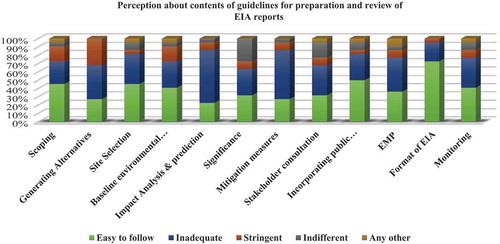

4.3 Perception on contents of guidelines for preparation and review of EIA reports

reflects a mixed trend of the perception of interviewed consultants about contents of the subject guidelines. Those who considered the contents of impact analysis and prediction along with mitigation measures inadequate were 64% and 59%, respectively. Nearly half of the consultants held the view that the requirements of scoping, site selection, baseline environmental conditions, incorporating public concerns and format of EIA were easy to follow

Figure 1. Perception about contents of guidelines for preparation and review of EIA reports.

Source: Interviews with EIA consultants in Pakistan

Explanation of categories:

Easy to follow: Feel no difficulty while fulfilling the requirements given in the guidelines.

Inadequate: Some aspects are missing or these requirements are not self-explanatory.

Stringent: Difficult to fulfil the requirements given in the guidelines, since these are very strict. Indifferent: The respondent was uncertain or did not respond to this question.

Any other: There were other reasons (e.g. practically did not follow the requirements of scoping).

4.4 Perception of contents of the guidelines for major roads

It was also attempted to seek views of consultants on some specific but important requirements, given in the sectoral guidelines for major roads projects (see ). Unfortunately, this trend suggests significant inadequacies regarding several aspects, including potential social and environmental impacts to be considered in EIA, requirements for EMPs and environmental budgeting and audit. For instance, the guidelines for EIA reports of major roads do not suggest considering loss in household income and effects on social life due to health impacts. Moreover, these do not suggest considering social, economic and environmental impacts of scheduling construction activities during office time as well as hours of peak traffic flow. Emphasis on use of non-renewable resources for the construction and operation phases is also missing in the guidelines. Though the guidelines do not ask for monitoring the impacts of road projects on biodiversity, these are given much significance in the EIA regimes elsewhere (Geneletti Citation2003; Loro et al. Citation2014; Igondova et al. Citation2016). This necessitates revisiting the contents of these guidelines after seeking input from consultants, academia, concerned officials and other stakeholders.

Table 4. Perception about contents of guidelines for major roads (% of respondents).

4.5 Key omissions and impediments in following the guidelines

To further clarify the perceptions about contents and requirements of the general as well as sectoral guidelines, it was deemed necessary to ask about the key omissions in them. Although some of the respondents categorically stated that there were no omissions, others provided very useful insights. Those generally pertained to a variety of projects, impacts to be specified, and improving post decision follow-up monitoring mechanisms suggested both in the general as well as road sector guidelines. The key omissions are highlighted in .

In addition to key omissions, the consultants were asked whether they ever faced any other significant impediments regarding the usage of any of the guidelines. A considerable proportion (55%) of respondents stated that lack of sharing information about similar projects (analogous impacts) and general/non-specific nature of guidelines were the impediments they had to face more frequently. The rest of the respondents (45%) said they did not face any impediments regarding the usage of guidelines. Nevertheless, environmental protection agencies in Pakistan are facing several challenges in implementation of the laws and ensuring that the guidelines are followed by consultants. Implementation of ‘suggested practical guidelines’ is an issue not only facing the concerned agencies in developing countries but also in developed countries like the UK (Bassi et al. Citation2012; Panigrahi and Amirapu Citation2012). Nadeem and Hameed (Citation2006, Citation2008)) found that EIA of an individual industry project (e.g. paper and board mill) took on average 1.5-month time and the consultants charged 0.5–1 Million Rupees (US$ 4032 to 8064, taking 1US$ = Rs. 124). For large projects (e.g. 100-km long motorway or an industrial estate spread at an area of 300 ha), 1 year was required. Those consultants not well-renowned were charging even less than 0.05 million Rupees. Many proponents, due to time constraints, did not emphasize on the quality of EIA. They also identified inadequacies in many aspects of EIA. Project proponents did not allocate sufficient funds and time required for conducting EIA studies. Resultantly, consultants compromised on the quality by collecting baseline data from secondary sources, avoiding detailed consideration of alternatives and quantitative assessment methods. Moreover, independent review committees were almost non-existent.

It is important to also mention here that some of these issues have been resolved. For instance, many EIA consultants have got adequate experience now (see ) and use quantitative methods which can be seen in some of the reports of road sector projects. For example, the EIA report for the construction of road from Expo Centre to Ring Road Lahore project included weighted matrix to evaluate the magnitude and significance of various impacts during construction and operation phases of the project (NESPAK/LDA Citation2017).

4.6 Key factors in improving the quality of EIA reports

Interviewees were asked to suggest key factors that can play important roles in improving the quality of EIA report. Those are presented in . Some of the factors pertain to old issues already identified by the authors as key issues/impediments in improving the quality of EIA reports. For instance, non-availability of baseline data, stakeholders’ consultation and insufficient budgetary allocation for conducting EIA (for further details, see Nadeem and Hameed Citation2006, Citation2008). Other factors relate to the use of specific methods and techniques for impact assessment, precision of prediction and monitoring as well as adequate experience of consultants. These can help improving the quality of EIAs, since these are also linked with ‘control mechanisms and best practice guidelines’ which may include improved regulations, relevant expertise of EIA reviewers and accreditation of consultants (Kågström Citation2016).

Box 3: Key factors in improving the quality of EIA report.

4.7 Legal status and need for updating guidelines

Regarding the legal status and any need for updating guidelines, most of the interviewed consultants (73%) suggested that the guidelines should be made to be followed compulsorily (see ). This again shows a tendency among them to follow the guidelines. They also stated that it was possible only if guidelines are thoroughly revised in the light of their concerns. This will lead to better protection of the environment and help improve the quality of EIA reports. Very few of the respondents stated that these should be followed to the extent possible as the current practice advocates so. Also, the use of guidelines depends upon the nature of project and the educational capability of the person conducting EIA. The extent of follow-up also depends upon the financial resources and political conditions.

Table 5. Views on the legal status and need for updating the guidelines (% of respondents).

International practices suggest that following the guidelines is not mandatory but used by the regulators and reviewers to pressurise consultants (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2001; Pavlyuk et al. Citation2017). Moreover, it would not be possible to follow all aspects contained in the sectoral guidelines in case of every project, since the circumstances, project location, size and possible environmental and socio-economic as well as cumulative impacts may vary. Only parts of the guidelines (pertaining to contents of EIA reports) can be made mandatory, like the World Bank guidelines. This is also because most of the procedural aspects pertaining to public hearings, review of EIA report, EMPs, follow-up mechanism and submission of annual monitoring report have already been clearly spelled out in the PAK-EPA’s Review of IEE and EIA Regulations, 2000 and these are mandatory requirements (for further detail, see Pak-EPA Citation2000).

As far as revision of the guidelines is concerned, a vast majority of responding consultants (82%) suggested that the old guidelines should be updated/revised (see ). The very reasons of revision as given by the respondents included changes in social behaviours, environmental conditions and technologies. They were also of the view that consideration of project alternatives and resettlement issues needed to be given more coverage in some of the sectoral guidelines. This also has links with developing socio-economic criteria to evaluate the significance of resettlement issues. Its absence in the guidelines has been raised as an issue in other developing countries, e.g. Syria (Haydar and Pediaditi Citation2010). When asked how frequently the guidelines should be updated/revised, 59% of the respondents were of the view that these should be updated every 5 years. Others thought updating may take place as and when needed. Only 9% of the respondents thought these may be updated after 10 years.

According to a study conducted under the umbrella of Pakistan’s National Impact Assessment Program, the sectoral guidelines for environmental reports should be reviewed and amended/improved. Code of conduct and registration mechanisms for EIA consultant should also be formulated (Fischer and Nadeem Citation2014). It is worth appreciating that Environment Protection Department of the Government of Punjab has recently notified regulations for the registration of environmental consultants (EPDP Citation2017).

4.8 Review of EIA reports

A few years ago, EIA reports were firstly reviewed by the in-house team of concerned environmental protection agency (EPA) and important cases were sent to the relevant committee of experts for further review and comment (Nadeem and Hameed Citation2008). However, the consultants’ opinion was divided on the question on who should review EIA reports. Although half of the respondents stated that these should be reviewed by the officials of the concerned EPA, an equal proportion of respondents were of the view that there should be an advisory committee as a third party but the concerned officials should also be involved. They further suggested that the review committees should consist of urban and environmental planners, related engineers, economists, lawyers, academics and government officials. It is encouraging to note that different committees comprising independent experts have been formed to assist the EPAs in reviewing EIA reports of various sector projects. The members of these committees are urban and environmental planners, engineers, relevant experts and EPA officials (GoPb-EPA Citation2015, Citation2016). The co-author is also a member of one of the expert committees.

4.9 Views on the review criteria suggested in the guidelines

A set of review criteria has been suggested in the guidelines for preparation and review of environmental reports (see Section 3.1). Consultants’ views on the review criteria were also sought. Surprisingly again, half of the respondents considered the review criteria as adequate if these are followed in true spirit in the light of the site-specific conditions, and if these are based on the mandate of institutions and stakeholders. This perception of adequacy of the criteria is based on couple of ‘ifs’ which raises doubts on their usefulness in the present state. Perhaps that is why rest of the respondents considered the criteria as inadequate. The very reasons behind this opinion as suggested by the respondents were that the review was done by the EPA officials only, the criteria were not focused which often created ambiguity and that some aspects were missing, e.g. difference in format of IEE and EIA. However, 59% of the respondents also suggested that the review criteria should be revised, following international review criteria like that of the World Bank, to make these clear and to the point. More emphasis should be given on baseline conditions, impacts identification and proposed mitigation measures during construction.

5. Conclusions and recommendations

The use of guidelines for preparing EIA reports is increasingly being advocated internationally (Waldeck et al. Citation2003; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013; Pavlyuk et al. Citation2017). This study is first of its kind which establishes the quality of Pakistani EIA guidelines and the extent to which these are followed. The guidelines are generally of good quality and most part of these is being used by the consultants. The guidelines not only provide a basic framework for preparation of EIA reports but also better management of environmental impacts during operational stage of project. Thus, it can be concluded that the quality and compliance of EIA guideline in Pakistan is better than in many other countries, where consultants tend to sidestep them (Bassi et al. Citation2012; Panigrahi and Amirapu Citation2012).

Albeit, there are some deficiencies in the contents of the guidelines which compromise on their quality and thus of EIA reports. These mainly pertain to inadequate emphasis on the use of quantitative methods of assessment and consideration of alternatives as well as weaknesses in the suggested post decision follow-up monitoring mechanism. These inadequacies are also because the guidelines are very old and not revised periodically involving EIA consultants. Thus, the quality of EIA guidelines has direct relation with the tendency to follow them provided these are updated taking onboard the EIA consultants and other stakeholders.

Overcoming the deficiencies in the guidelines, as pointed out by the consultants, can not only contribute to improving quality of the guidelines but also of EIA reports. In this context, the EIA reports review criteria as suggested in the guidelines should also be revisited, because this can further motivate the consultants to follow the guidelines in letter and spirit. One way of identifying gaps in the review criteria and making it more objective, systematic and at par with international practices could be to carryout comparative review of the quality of EIA reports using the review criteria suggested in the guidelines (see Section 3.1), as well as the one most frequently used internationally.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge diligent efforts by Mr. Yasir Mahmood, Ms. Iqra Kamil and Ms. Afnan Mehfooz Khan for collecting the requisite data. We are also thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments. These greatly helped to improve the quality of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- ADB. 2003. Environmental assessment guidelines. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Ahmad B, Wood CM. 2002. A comparative evaluation of the EIA systems in Egypt, Turkey and Tunisia. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 22:213–234.

- Al-Azri NS, Al-Busaidi RO, Sulaiman H, Al-Azri AR. 2014. Comparative evaluation of EIA systems in the Gulf Cooperation Council States. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 32(2):136–149.

- Bassi A, Howard R, Geneletti D, Ferrari S. 2012. UK and Italian EIA systems: a comparative study on management practice and performance in the construction industry. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 34:1–11.

- Brew D, Lee N. 1996. Reviewing the quality of donor agency environmental assessment guidelines. Proj Appraisal. 11(2):79–84.

- CEC 2003. (Impacts Assessment Unit, Oxford Brookes University). Five years report to the European Parliament and the Council on the Application and Effectiveness of the EIA Directive.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:65–72.

- EPDP. 2017. The Punjab environmental protection (registration of environmental consultants) regulations, 2017. Lahore: Environment Protection Department, Government of the Punjab.

- Fischer TB, Nadeem O. 2014. Environmental impact assessment course curriculum for higher education institutions in Pakistan. Islamabad: IUCN Pakistan.

- Fischer TB, Yu X. 2018. Sustainability appraisal in neighbourhood planning in England. J Environ Planning Mgmt. doi:10.1080/09640568.2018.1454304

- Geneletti D. 2003. Biodiversity impact assessment of roads: an approach based on ecosystem rarity. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23:343–365.

- Glasson J, Therivel R, Chadwick A. 2012. Introduction to environmental impact assessment. 4th ed. London: Routledge.

- GoP. 1997. Pakistan Environmental Protection Act, 1997. Islamabad: Ministry of Environment, Government of Pakistan.

- GoP. 1997a. Guidelines for the preparation and review of environmental reports. Islamabad: Ministry of Environment, Government of Pakistan.

- GoP. 1997b. Sectoral guidelines for environmental reports-major roads. Islamabad: Ministry of Environment, Government of Pakistan.

- GoPb-EPA, 2015. Office order for constitution of committee of experts for review of IEE/EIA reports of energy, oil and gas, housing sectors etc. Lahore: Government of Punjab, Environment Protection Agency.

- GoPb-EPA, 2016. Office order for constitution of committee of experts for review of IEE/EIA reports of transportation and urban development sectors. Lahore: Government of Punjab, Environment Protection Agency.

- Haydar F, Pediaditi K. 2010. Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system in Syria. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:363–370.

- Hesse-Biber NS. 2010. Mixed methods research: merging theory with practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

- IEMA (Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment). 2001. EIS review criteria Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment, London

- Igondova E, Pavlickova K, Majzlan O. 2016. The ecological impact assessment of a proposed road development (the Slovak approach). Environ Impact Assess Rev. 59:43–54.

- Kågström M. 2016. Between ‘best’ and ‘good enough’: how consultants guide quality in environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 60:169–175.

- Kamijo T, Huang G. 2017. Focusing on the quality of EIS to solve the constraints on EIA systems in developing countries: a literature review. Tokyo: JICA Research Institute.

- Kamil I, Khan AM 2014. Usefulness of Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency guidelines for quality EIA reports. Unpublished Final Year Project Report. Lahore: University of Engineering & Technology.

- Khawaja SA, Nabeela NJ. 2014. Review of IEE and EIA regulations 2000. Islamabad: IUCN Pakistan.

- Landim NT, Sánchez E. 2012. The contents and scope of environmental impact statements: how do they evolve over time?. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 30(4):217–228.

- Lee N, Colley R. 1990. Reviewing the quality of environmental statements,” Occasional paper no. 24, EIA Centre. Manchester: University of Manchester 1990.

- Loro M, Arce RM, Ortega E, Martín B. 2014. Road-corridor planning in the EIA procedure in Spain. Review Case Studies Environ Impact Assess Rev. 44:11–21.

- Momtaz S. 2002. Environmental impact assessment in Bangladesh: a critical review. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 22:163–179.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Annandale D, Cappelluti J. 2001. Practitioner perspectives on what influences EIA quality. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 19(4):321–325.

- Nadeem O, Fischer TB. 2011. An evaluation framework for effective public participation in EIA in Pakistan. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31:36–47.

- Nadeem O, Hameed R. 2006. A critical review of the adequacy of EIA reports-evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences. 1(1):54–61.

- Nadeem O, Hameed R. 2008. Evaluation of EIA system in Pakistan. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28:562–571.

- NESPAK/LDA. 2017. EIA report for the construction of road from Expo Centre to Ring Road Lahore project.. Lahore: National Engineering Services Pakistan/Lahore Development Authority.

- Nizami AS, Molander S, Asam ZZ, Rafique R, Korres NE, Kiely G, Murphy JD. 2011. Comparative analysis using EIA for developed and developing countries: case studies of hydroelectric power plants in Pakistan. Norway Sweden Int J Sust Dev World. 18(2):134–142.

- Pak-EPA. 2000. Review of IEE and EIA regulations 2000. Islamabad: Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency.

- Paliwal R. 2006. EIA practice in India and its evaluation using SWOT analysis. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:492–510.

- Panigrahi JK, Amirapu S. 2012. An assessment of EIA system in India. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 35:23–36.

- Pavlyuk O, Noble BF, Blakley JAE, Jaeger JAG. 2017. Fragmentary provisions for uncertainty disclosure and consideration in EA legislation, regulations and guidelines and the need for improvement. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 66:14–23.

- Phylip-Jones J, Tb F. 2013. EIA for wind farms in the United Kingdom and Germany. Environ Assess Policy Mgmt. 15(2):1340008.

- Rebelo C, Guerreiro J. 2017. Comparative evaluation of the EIA systems in Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Angola, and the European Union. J. Prot. 8:603–636.

- Retief F. 2007. A quality and effectiveness review protocol for strategic environmental assessment (SEA) in developing countries. J Environ Assess Policy Mgmt. 9(4):443–471.

- Saeed R, Sattar A, Iqbal Z, Imran M, Nadeem R. 2012. Environmental impact assessment (EIA): an overlooked instrument for sustainable development in Pakistan. Environ Monit Assess. 184:1909–1919.

- Shah A, Salimullah K, Shah MH, Razaullah K, Irfan UJ. 2010. Environmental impact assessment (EIA) of infrastructure development projects in developing countries. OIDA Int J Sust Dev. 1(4):47–54.

- Spooner B 1998. Review of the quality of EIA guidelines, their use and circumnavigation. Environmental Planning Issues, No. 19. International Institute for Environment and Development. [accessed 2018 Jan 10] http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/7813IIED.pdf.

- Waldeck S, Morrison-Saunders A, Annandale D. 2003. Effectiveness of non-legal EIA guidance from the perspective of consultants in Western Australia. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 21(3):251–256.

- Wood C. 1999. Comparative evaluation of environmental impact assessment systems. In: Petts J, editor. Handbook of environmental impact assessment. Vol.2: environmental impact assessment in practice: impacts and limitations. Oxford: Blackwell Science; p. 10–34.