ABSTRACT

The degree of robustness of environmental management program in the EIA reports of 56 green-field and 28 brown-field environmentally approved projects was found to be low, revealing that it is not considered seriously by the EIA consultants and the decision-makers. EMPg, akin to EIA follow-up, specific to a project at a given location, is the most important output of the EIA process especially for the developing countries where priority is on the economic development by way of development projects and the EIA process has inherent weaknesses. A meticulously prepared, implemented, operationalized, monitored, periodically audited and continually improved EMPg in different life-cycle phases of a project could possibly offset limitations of the EIA process. Considering lack of guidelines available on the development of EMPg, elaborate guidelines are proposed. EMPg could be prepared as a separate document to facilitate development of project manual. TOR for brown-field projects need a totally different approach. Amending the currently followed EIA process and introducing an additional stage of mandatory approval of EMPg, and third party audit would improve its robustness.

1. Introduction

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a process for taking account of the potential environmental consequences of a proposed action during the planning, design, decision-making and implementation stages of that action. EIA follow-up should be an integral part of this process, and in its simplest conception, follow-up seeks to understand EIA outcomes (Morrison-Saunders and Arts Citation2004). The term ‘follow-up’ is used as an umbrella term for various EIA activities, viz. monitoring, evaluation, management and communication of the environmental performance of a project or plan (Arts et al. Citation2001, Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2007), and is necessary to (a) ensure that the terms and conditions of approval are met; (b) monitor the impacts of development and the effectiveness of mitigation measures; (c) conduct environmental audit and monitoring for sustainable environmental management; (d) enhance control, management, knowledge and acceptance-legitimization of a project (Arts et al. Citation1999); and (e) strengthen future EIA applications and mitigation measures (IAIA Citation1999). Thus, EIA follow-up is essentially a post-project activity and EIA follow-up process includes a range of activities designed during the environmental approval stage of a project (Jha-Thakur et al. Citation2009). Environmental Management Plan (EMP) terminology, akin to design of EIA follow-up (Jha-Thakur et al. Citation2009), is used in the Indian EIA process (MOEF Citation2006) and a wide range of guidelines for EIA (ADB Citation2003, WB Citation1999a, UNEP Citation2002, Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014), and also in literature (Brew and Lee Citation1996, George Citation2000, Tinker et al. Citation2005).

EMP is an integral and important component of an EIA report, an action plan (Floroiu Citation2012) consisting of a set of mitigation, monitoring, and institutional measures required during implementation and operation of a project to eliminate, offset or reduce adverse environmental and social impacts to acceptable levels (WB Citation1999b). It is essentially a road-map that describes how the key elements, viz. mitigation measures, implementation and monitoring program, cost estimates (Floroiu Citation2012), resource requirements, and institutional arrangements are incorporated to provide assurance that the project proponent will implement environmental management measures simultaneously with the project (DEAT Citation2004a, ADB Citation2012, MOEF Citation2012) so that negative effects on the biophysical and socio-economic environments get eliminated or minimized and benefits to all parties are maximized in the most cost-effective manner (CBD Citation2005). The management policy and mechanism of policy implementation, performance requirement and reporting (Abbot Point Citation2005) are clearly spelt out, legal requirements for the project are defined and regulatory permits and licenses are identified (Aquasure Citation2011) in EMP. It forms a more systematic and explicit document to be used by the planning authorities in formulating environmental approval conditions (Brew and Lee Citation1996).

Environmental management planning is a result-oriented process (Loksha Citation2008), which is integrated with project planning, design, construction, operation and decommissioning phases (Kiss Citation2013). The management actions are clearly defined to take into account different scenarios in each phase of the project life-cycle (Lochner Citation2005, Magnox North Citation2009). EIA team leader (Rathi Citation2017) compiles the reports prepared by different functional professionals, collates and integrates into a comprehensive EMP in consultation with them. Thereafter concurrence and commitment (Rathi Citation2016) of the project proponent is obtained on the suggested EMP. EMP needs to facilitate the project organization in internalizing the externalities arising out of the developmental activities that would otherwise become a social cost (EIA Newsletter Citation1996).

There is no standard format for EMP (Floroiu Citation2012) and it needs to be devised to fit the circumstances in which it is being developed to meet specific requirements (WB Citation1999a, CSIR Citation2002, DEAT, Citation2004a). EMP checklist (ADB Citation2011), template of monitoring program (Baby Citation2011), and institutional arrangement and responsibilities (ADB Citation2017) are available. EMP includes complaint and notifiable incident procedure, communication and liaison with local residents, and environmental restoration between pre- and post-consent stages (BMG Citation2015).

The value and importance of integrating EIA (Perdicoulis et al. Citation2012, Hollands and Palframan Citation2014) with wider environmental management system through EMP monitoring and review is illustrated using project life-cycle model (DEAT Citation2004b). Regular reviews and environmental audits (DEAT Citation2004c) identify the existing and potential environmental problems and determine the action needed to comply with the legal requirements and for achieving quantitative and auditable performance targets and outcomes (EPA Citation1995; Citation2013). EMP, integral part of project operation manual (IEMA Citation2008, Citation2015, Citation2016), is essential to achieving environmentally sound design by incorporatingprevention and control, compensatory and remedial measures(USAID Citation2005), in forming the basis for consultation and negotiation of outcomes, and tool for promoting accountability (Shah Citation2009). It should act as a ‘live’ document allowing it to be updated with the availability of new information/ details and also at subsequent development phases. The monitoring indicators for each category at each stage of the project and resettlement action plan (AfDB Citation2001) are included for verifying implementation of mitigation measures and outcomes (effectiveness). Preparation of EMP should ensure that the suggested mitigation measures are feasible, practical, affordable and likely to be successful (Kiss Citation2013).

A ‘plan’ consisting of a set of objectives to be achieved in a longer time-frame and setting context for programs could be conceptual, philosophical and/ or abstract to some extent whereas a ‘program’, describing the action points and mechanism of implementation facilitates the project proponent during implementation of the project. Thus, ‘Environmental Management Program’ (EMPg) terminology (Rathi Citation2017) is followed in place of EMP generally adopted in EIA reports. EMP terminology is used in the manuscript while referring to the literature and EMPg otherwise. The objectives of this study are describing the elements of EMPg at length to facilitate systematic development of EMPg in an EIA report, and evaluating the robustness––quality and completeness of EMPg in EIA reports of the projects which were granted environmental clearance (MOEF Citation2014).

2. Environmental management program

EMPg is considered integral to the conceptual approach to the preparation of EIA report (Rathi Citation2017) since mere suggesting mitigation measures without a mechanism of implementation and monitoring is not adequate. EMP is very specific (WB Citation1999a, Kiss Citation2013) to the EIA report of a project and contains site-specific plan to ensure that the necessary measures are identified and implemented to mitigate environmental effects and comply with the legislations. The extent of scope, coverage and detailing of EMPg in an EIA report depends upon the terms of reference (TOR), project sector, type and scale of the project, site and its environmental settings, phases involved in the project life-cycle, construction methodology, schedule and duration, concerns of the local population, etc. For example, EMPg for a given coal-based thermal power project proposed in say, coastal area, arid zone or the vicinity of orchards will be different. Further, EMPg for a large green-field dam, irrigation, integrated steel, petroleum refinery, petrochemical complex, coal based thermal power project, etc. will be very exhaustive compared to that for a small dam, secondary steel and a brown-field project proposed in an industrial area. For an EMPg to be effective, it should be realistic, targeted, funded, implemented, and considered early in the project life-cycle to incorporate preventive measures.

Parkes et al. (Citation2001) attributed slow utilization of EMPs in the developing countries to, among others, lack of guidelines on the compilation and implementation of EMPs. Considering this, the elements of a typical EMPg for development projects are discussed at length to serve as guidelines for developing EMPg systematically.

2.1. Environmental management program for green-field projects

The prime objective of EMPg, which is prepared separately for each phase of project life-cycle, viz. pre-construction, construction, operation and post-operation, is to suggest a road map that will ensure managing environmental impacts within the acceptable limits in addition to environmental enhancement. The road map essentially includes (a) establishing administrative systems and procedures, which will ensure incorporation and implementation of mitigation measures right from the conceptual stage of the project; (b) operationalization and maintenance of the implemented measures; (c) addressing residual impacts (Rathi Citation2017) and additional impacts generally encountered during start-ups, shut-downs and process upsets in case of manufacturing and energy generation projects (Rathi Citation2016); (d) environmental monitoring, compliance to the applicable environmental regulations, evaluating effectiveness of the mitigation measures provided, determining deviations from predicted impacts (Choudhury Citation2014) and improving environmental performance; (e) identification and implementation of environmental enhancement measures; (f) auditing of EMPg (DEAT Citation2004c) and incorporating revisions from time to time to improve effectiveness; g) management review; h) internal as well as external reporting (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014), etc. An elaborate, comprehensive and updated EMPg facilitates an organization in its smooth functioning, establishing environmental management system and setting environmental performance standards. Stakeholders’ interaction and communication (Lochner Citation2005) is also an important component of EMPg. A typical EMPg consists of the following elements:

2.1.1. Administrative frame-work

A well-defined administrative frame-work in the form of Environmental Management Cell (EMC) (Rathi Citation2016), referred as Environmental Management Office (ADB Citation2003) and Institutional arrangement (WB Citation1999a) is specified with clarity on the roles and responsibilities (Marshall Citation2005) at each hierarchical level and the procedures. EMC, consisting of environmental professionals, laboratory technicians and administrative personnel including public relation professionals is entrusted with the overall responsibility of EMPg, right from the project conceptual stage. The composition of EMC depends upon the type and scale of the project and varies over the project life-cycle phases. EMC ensures (a) that EMPg components get recognized and incorporated in design and detailed engineering of the project, implemented and remain operational along with the project; (b) preparation of guidelines for contractors and sub-contractors on the matters related to EMPg; (c) development of environmental monitoring indicators and environmental performance indicators (Lochner Citation2005); (d) evaluation of efficacy and adequacy of the mitigation measures provided, and additional control measures; (e) monitoring of resource use and pollution load generation; (f) facilitating top management in framing environmental policy and developing structured environmental management process in the organization leading to environmental management system (EPA Citation2013) in due course of time; (g) advising operation team on environmental implications of operational (product and process) variations; (h) internal and external reporting; (i) periodic audit and management review for improving environmental performance; (j) updating of EMPg, etc. It is a good practice for EMC to be functionally independent of operation cell and responsible directly to the top management (Rathi Citation2016).

2.1.2. Environmental impact management program (EIMPg)

EIMPg summarizes significant environmental impacts assessed and corresponding mitigation measures (Floroiu Citation2012) suggested separately for each life-cycle phase, describes how mitigation measures will be implemented along with the project within the allocated resources, and responsibilities assigned for implementation and supervision. It describes preparation and incorporation of standard operating procedures for control measures in the operating manual, and training of operating personnel for control systems. It takes into account the scenarios of normal operation, abnormal situation, and emergency/ accidental situation in each life-cycle phase (Lochner Citation2005, Magnox North Citation2009). Contingency program (Rathi Citation2016) for restoration of floral species affected by accidental emissions and discharges, compensation for affected crops, population and property, remediation of soil and water bodies affected by accidental spills and discharges, etc., are also included. The mechanisms of periodic audit, performance evaluation, management review, communication with external stakeholders, public awareness, grievance redressal, and updation of EIMPg to ensure that it remains effective, adaptive to new and changing circumstances and responsive to emerging needs are spelt out clearly.

On getting environmental approval, program for compliance with the approval conditions is incorporated in EIMPg. Another major revision is done on completion of the detailed design and engineering of the project. While equipment design and engineering consider permissible limits specified in the environmental approval conditions, residual impacts are determined from limitations of the technology, design, equipment and process control and instrumentation. EIMPg incorporates best engineering and environmental practices. It is dynamic and flexible, considering (a) that initial EIMPg was prepared at an early stage of the project life-cycle when project design and details might not have been finalized; (b) deviations in the design and implementation, (c) malfunctioning of equipment and instruments; (d) variations in the quality of feedstock, other inputs, fuel, and operating features like throughput and product-mix; (e) predicted impacts at variance with the actual ones, rendering the suggested mitigation measures ineffective or inadequate; (f) climatic changes affecting the local meteorology and predicted impacts undergoing changes spatially as well as temporally; (g) developments taking place in the proximity of the project site; (h) applicable regulations becoming more stringent or new legislations coming into force, etc. The frequency and extent of reviews of EIMPg will depend upon the project life-cycle phase. For example, EIMPg of infrastructural projects like highways and ports will be reviewed more frequently during construction phase whereas mining, manufacturing and energy projects will be reviewed more frequently during operation phase. A typical EIMPg describes the following programs:

Pre-construction phase––management of impacts arising from activities like land surveys, seismic surveys, prospecting of mineral resources, hydrocarbons and water, site development, mobilization of resources, relocation of common resources and utilities, change in land use, etc., to ensure protection of ecological, archaeological and cultural heritage resources.

Construction phase––management of:

Construction and building materials and water––sourcing, stockpiling/ storage, handling and transportation; extraction of water from the identified sources (surface or underground) and transportation to the site; borrow areas; barricading the activities like removal/ extraction of materials, mining/ quarrying, crushing of rubbles/ stones, etc., for protection of sensitive habitats; material handling and storage; scheduling of activities considering flowering seasons of plants, breeding period of fauna and nesting period of avifauna; progressive landscaping after extraction. A holistic approach is taken even when sources of construction materials and water fall beyond the study area or contractors arrange these, etc.

Transport and traffic––identification of transportation routes for material transportation in closed/ covered vehicle; paving/ asphalting/ upgrading the identified road stretches; preparation of guidelines for contractors with regard to timings, speed, honking, handling and storages at the site; monitoring mechanism for ambient air quality, noise and dust nuisance, and the practices employed by contractors; public grievance redressal mechanism, etc.

Training programs for contract and sub-contract personnel on the topics like environmental awareness (Lochner Citation2005) and protection, impact mitigation measures, environmental monitoring, occupational safety and health, good operating practices, etc.

Ecology––quantification of loss of vegetation and the dependent fauna due to site development and construction-related activities in the core zone and compensatory mechanism; scheduling of construction activities considering breeding period of sensitive and rare fauna, flowering season of flora and cropping; isolation and protection of habitats; protection of aquatic/ marine/ coastal biota from discharge of turbid wastewater from on-shore and off-shore activities, etc.

Sediment transport––erosion control; protection of natural drainage, river banks and shorelines; control of diffuse pollution of drainage system and water bodies, etc.

Air quality and noise––emission control from vehicles, earth moving equipment, construction power generation and batch mixing plant; fugitive emissions from storage and handling of construction materials, construction activities, etc.

Storm water management and treatment of wastewater and sewage

Solid waste––quantification of solid waste generation from excavation, demolition and construction, and its reuse; used packaging; domestic waste from labor camps, canteens, sewage, house-hold, etc.; identification of low-lying areas for landfilling of inert solid waste; identification and quantification of hazardous wastes like used lubricating oils from material handling equipment, pumps and compressors, diesel generating sets and workshops, oils, paints, spilled fuel, etc.; identification of authorized vendors for disposal, etc.

Post-construction phase––rehabilitation of the project site, demolished labor camps and other temporary structures and borrow areas to restore the drainage pattern; ecological restoration; use of excavated soil; levelling and landscaping, etc.

Operation phase––overseeing and documentation of the programs undertaken by the operation and logistics cells:

Air quality––integration of air emission control devices with the project operations; alarms and interlocks for tripping equipment in case of failure of a control device; control of fugitive emissions from storage, stockpiling, handling and transportation; odor control; periodic evaluation of effectiveness of control measures employed, etc.

Noise and vibration––attenuation of noise and vibration generated from various activities; protection, maintenance and measurement of effectiveness of noise barriers installed and trenches provided, etc.

Water and wastewater––health of water resources; segregation of wastewater streams, treatment (separately or at a central facility) and disposal of treated wastewater from guard pond to the approved receiving body; health of receiving body; recycling of wastewater into the respective treatment unit(s) in case of non-conformance; recycling/ reuse of the treated wastewater, etc.

Solid waste––identification and segregation of wastes, viz. industrial hazardous, industrial non-hazardous, domestic and e-waste from different sources; temporary storage; transportation for disposal to approved vendors/ disposal sites, etc.

Occupational health––identification of hazardous substances used/ generated; noise, temperature and concentration levels of dust and smoke in the work environment and potential health hazards; health of working personnel and those exposed; automation in operations to reduce physical presence of personnel at hazardous work stations; rotation of personnel to minimize continuous exposure; good work environment practices; good housekeeping, etc. (Even though an EIA report deals with environmental impacts on ambient (external/ out-door) environment, it is a good practice to include occupational health (MOEF Citation2012) related aspects, especially for the projects involving hazardous and harmful substances, and dust generation activities.)

Safety and emergency response––work place safety practices and safety audits; handling and storage of hazardous substances; operationalization of emergency response program––onsite and offsite including systems and hardware, mock-drills, training, mutual aid system, etc.

Transport and traffic––transportation network avoiding wildlife migration routes, and development/ reinforcement of physical infrastructure to facilitate smooth transport; guidelines for transport contractors on speed, closed/ covered vehicles, transport timings, vehicle condition, etc.; training of drivers and helpers; provision of parking, fueling and maintenance of vehicles, and basic amenities for transport personnel, etc.

Post-operation phase––reclamation, rehabilitation, restoration, landscaping, etc. of the site and project affected areas on completion of operation phase, especially for mining, hydrocarbon exploration and production, and waste management facilities.

2.1.3. Environmental monitoring program

Environmental monitoring and auditing provide concrete evidence of environmental consequences of the EIA activities (Morrison-Saunders and Arts Citation2004). The program describes how performance evaluation of the mitigation measures employed in different life-cycle phases will be carried out, and compliance to the applicable regulations will be ensured. The documented procedure, prepared separately for each life-cycle phase, describes (a) constitution of environmental monitoring group within EMC and its roles and responsibilities (Floroiu Citation2012); (b) monitoring parameters, locations, periodicity, methodology, sample preservation and transportation; (c) monitoring of ecological and social indicators, rehabilitation and resettlement program (AfDB Citation2001) for project affected persons, social development and community welfare programs, land use/ land cover and drainage pattern, etc.; (d) capital requirement for the required infrastructural facilities, equipment and instruments, and recurring expenses; (e) documentation of monitoring, data representation and reporting, etc. Implementation of good laboratory practices in accordance with the laboratory accreditation requirements; mechanism of providing feedback to operation cell on monitoring observations and deviations from specified standards for taking timely corrective action, and issuing advisory to operation cell and the management on weather forecasts on events like cyclones, heat waves, cold waves, heavy rainfall, etc., are also described.

Environmental monitoring, carried out regularly in operation phase helps in (a) assessing residual as well as cumulative impacts; (b) evaluating adequacy and efficacy of the mitigation measures employed; (c) understanding deviations from the predicted emissions and discharges; (d) validating the assumptions made for source emissions and discharges for impact predictions; (e) confirming applicability and suitability of the prediction tool(s) employed; (f) measuring pollution inventory being released into the environment; (g) providing additional/ supplementary measures for continual improvements; (h) reporting to internal and external stakeholders; (i) sustainability reporting (GRI Citation1997); (j) audits and scrutiny in future; (k) resource conservation and other pro-active actions; (l) improving the environmental monitoring program; (m) improving transparency and establishing credibility of the organization by making available the information in public domain; (n) serving as secondary data for establishing baseline conditions for future projects, carrying capacity studies, regional environmental assessment, and strategic environmental assessment, etc.

2.1.4. Environmental compliance management program

Environmental compliance with the applicable regulatory regime at federal, state and local levels all the time is the bottom-line for carrying out any activity. The program includes (a) how statutory requirements, applicable regulations and Orders of the Courts are ascertained and kept updated; (b) putting in place a robust and transparent system (Marshall Citation2005) to give confidence to the management, regulatory agencies, neighboring public and other stakeholders; (c) strengthening monitoring by introducing additional/ new facilities, real time online measurements and advanced control systems for critical parameters; (d) framing policy on waste management hierarchy; (e) coordination mechanism with the process control and plant laboratories, and operation cell for capturing variations in inputs, capacity, product-mix, processes, production plan, etc., and issuing alerts to them for taking corrective actions before permissible discharge limits get approached; (f) bench-marking and adopting best environmental practices; (g) internal and external reporting mechanism for situations of near misses and non-compliance, and program for corrective (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014) and preventive actions; h) upgrading skills of the working personnel on a continual basis, etc.

2.1.5. Environmental and social enhancement programs

Typical environmental and social enhancement programs include programs for:

Top soil management––quantification of top soil to be removed from excavation, methodology of its removal, handling, storage and preservation, and use in a specified time-frame.

Green belt development––width of green belt all around inner periphery of the project site boundaries, species and number of trees and shrubs to be planted, mapping of plantation layout, plantation schedule, precautionary and protection measures, monitoring mechanism for growth and survival rate, replantation, etc. (The road-side and median plantation within the project boundaries do not fit into the basic concept of green belt though it adds to greening.)

Rain water harvesting and water conservation––estimation of catchment area and water quantity which can be harvested, storage of collected rain water in surface reservoirs or underground storage tanks for direct use or recharge into ground water regime; roof top water collection based on project-specific considerations; water conservation measures; minimizing losses due to seepage, leakage and evaporation, etc.

On-going resource conservation framework––energy efficient buildings and lightings, tapping non-conventional sources of energy, targeted efforts on waste minimization (Rathi Citation2009), cleaner production, minimizing consumption of natural resources––feedstock, other inputs and utilities, reduction of carbon footprint, inherent safety, best practices, good housekeeping, etc.

Proficiency improvement––continual education on the basis of training need assessment and environmental performance objectives of the organization.

Ecological enhancement––development and maintenance of artificial habitats, afforestation, greening of project site and other areas, landscaping, etc.

Community welfare––activities identified in social need assessment report and those committed by the project proponent; meeting aspiration of local population on education, health care and skills enhancement; activities under corporate social responsibility (CSR) that will make difference to the community, etc.

Stakeholders interaction and communication (Lochner Citation2005)––addressing apprehensions and grievances of local population; training programs on environmental awareness, visits of stakeholders to the project site; coordinating mock drills as per the disaster management program; good communication and liaising with external stakeholders, ensuring transparency in impact management practices and compensation-related matters, etc.

2.2. Environmental management program for brown-field projects

For expansion, diversification and modernization project proposals, due-diligence of the on-going EMPg for the operating project(s) is described for its (a) status, adequacy and effectiveness of administrative framework; (b) compliance with the applicable regulations; (c) standard operating and control procedures; (d) ecological, social and environmental performance indicators; (e) audits, management reviews and follow-up actions; (f) environmental and social enhancement; (g) communication with internal and external stakeholders; h) certification under QMS 9001, EMS 14001, OHSAS 18001, etc. This helps in bringing out shortcomings in the operational EMPg. Considering the shortcomings and EIA of the proposed project(s), supplementary EMPg is prepared using the guidelines described in Section 2.1 in such a way that it gets integrated (Rathi Citation2016) with the on-going EMPg. The integrated and comprehensive EMPg covers the existing as well as the proposed projects while ensuring that the existing facilities and manpower get utilized to the maximum extent.

3. Evaluation of robustness of EMPg––an Indian case study

EMP review criteria are given by Lochner (Citation2005). In this study, rigorous evaluation of EMPs in the EIA reports of green-field as well as brown-field projects is attempted with the help of the proposed criteria.

Methodology

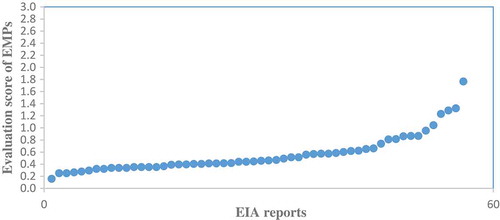

25% of the EIA reports were selected randomly from 225 EIA reports of green-field projects other than township and construction projects, which were granted environmental clearance in India (MOEF Citation2014) in the period October 2016 to March 2018. Like-wise, 10% of the EIA reports were selected randomly from 277 EIA reports of brown-field projects. summarizes project sectors of these EIA reports. The criteria for evaluating the robustness of EMPs of green-field projects and brown-field projects are proposed in and , respectively. The evaluation of each criterion is done in the scale 0–3; 0 being non-inclusion of the criterion in EMP, 1 inadequate, 2 reasonably adequate and 3 adequate inclusion. The respective tables show distribution of EMPs of 56 EIA reports of green-field projects, prepared by 44 consultants, and 28 EIA reports of brown-field projects, prepared by as many consultants against each criterion. The robustness of an EMP is determined by aggregating the scores of each criterion and taking mean, without assigning any weightages for the sake of simplicity. The robustness is considered on the basis of the mean score: 3––being high, 2–3––fairly high, 1–2––low, and <1––very low.

(B) Findings

Table 1. Project sectors evaluated.

Table 2. Evaluation of robustness of environmental management program for green-field projects.

Table 3. Evaluation of robustness of environmental management program for brown-field projects.

The major findings of evaluation of the EMPs are summarized in and for green-field and brown-field projects, respectively.

Box 1. Findings of the evaluation of EMPgs of green-field projects.

Box 2. Findings of the evaluation of EMPgs of brown-field projects.

3.1. Green-field projects

The general findings are as follows: (a) significant impacts and corresponding mitigation measures are not summarized and mitigation measures are not targeted; (b) mitigation measures are prescriptive and there is inconsistency in the language used in a given report, e.g. phrases like ‘must be organized’, ‘shall be given’, ‘shall do’, ‘will be institutionalized’, ‘should be ensured’, ‘may be sought’, ‘has done’, ‘we have’, ‘where possible’, ‘as required’, etc., are used instead of phrases ‘will’ and ‘must’, and avoiding ambiguous terminology (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014); (c) construction phase is considered to be of transient in nature and prevailing for a short duration (without mentioning the duration) even for large projects where it could be of the order of 3 years, e.g. large thermal power projects and dams; (d) demineralized water plant and cooling towers are classified as pollution control equipment; (e) mitigation measures in operation-phase of large industrial area projects are confused with those of individual projects; (f) capital budget for CSR-related activities is mentioned for social enhancement when such activities are mandated from profits earned by an organization; (g) theoretical aspects of safety and disaster management are described in a separate chapter without bringing out operational aspects in EMP; (h) theoretical aspects of rainwater harvesting and general aspects of green belt are dwelt at length, without being site and project specific; (i) environmental monitoring is considered as ‘post-project’ monitoring, etc.

The evaluation shows mean, median and most commonly occurring scores as 0.56, 0.46 and 0.41, respectively, revealing that the degree of robustness of EMPs in general is very low. From it may be observed that five EMPs of green-field projects displayed some degree of robustness. These EMPs were part of the EIA reports of two projects of expressway seeking multilateral funding and one each of industrial area, port and coal mining. The EMPs of manufacturing and energy sector projects had very low robustness.

Table 4. Summary of robust EMPs.

3.2. Brown-field projects

General observations are as follows: (a) conceptual aspects are described in almost all the EMPs without taking cognizance of the operational EMP as evident from the phrases used, e.g. ‘emergency plan should be prepared in advance’, ‘proper storage tanks should be designed’, and ‘full-fledged firefighting will be provided’ for expansion of petroleum refinery, LPG storage, hydrocarbon pipelines and industrial area projects, giving a wrong impression that such facilities did not exist in the operating projects; (b) several EMPs of large manufacturing sector projects mention ‘full-fledged environment department should be set up’, ‘safety audit must be done’, ‘green belt development will be done’, ‘project proponent’s project team will review EMP prior to start of expansion’, ‘it will be ensured that safety management system is in place’, ‘project proponent will carry out management review and evaluate management system’, etc., without any reference to the existing systems, layout and infrastructural facilities; (c) cost- capital and recurring of the proposed EMP is mentioned without giving any details of the actual expenditure incurred in previous years; (d) CSR activities, green belt, fire-fighting facilities, wastewater treatment plant, occupational health and safety with exhaustive list of personal protective equipment, etc., are dwelt at length without linking these to the proposed project(s). EMPs for expansion of thermal power plants, however, reported the quantities of fly ash generated and utilized from the operating plants. One EMP summarized existing monitoring program while proposing monitoring program for the expansion project but without any discussion on its adequacy and effectiveness.

4. Discussion

It was observed in a previous study (Rathi Citation2017) that the quality of EMPgs was far from satisfactory, and focus in EIA reports was skewed towards baseline data generation, and impact assessment and mitigation measures. Jha-Thakur et al. (Citation2009) reported that follow-up design stage in India had its drawbacks, and more effort and thought should be put to overcoming drawbacks. The Indian regulatory frame-work on EIA process (MOEF Citation2006) specifies that EMP in an EIA report describes the administrative aspects for ensuring that mitigative measures are implemented and their effectiveness is monitored after approval of the EIA, and environmental monitoring program describes technical aspects of monitoring the effectiveness of mitigation measures including methodologies, frequency, location, data analysis, reporting schedules, emergency procedures, detailed budget and procurement schedules. However, it is observed that all the EIA reports did not strictly adhere to these requirements and still got approved. The findings of this study that EMP, a key component of EIA process did not receive the attention it deserves from the consultants as well as the decision-making authority are in agreement with the studies referred above.

EMP chapter in all the EIA reports evaluated in the case study is found to begin with the conceptual, generic and theoretical description of purpose and objectives of EMP, viz. pollution prevention, prevention of hazards, minimization of consumption of resources, minimization of generation of pollutants, performance evaluation and sustainable development, etc. But the subsequent description is not concise (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014) and does not describe how the stated purpose and objectives are proposed to be achieved. The findings of this study that the EMPs are too generic, and guidelines for contractors are not prepared are in agreement with those reported by Floroiu (Citation2012), and Kiss (Citation2013) who reviewed 10 projects in three countries.

The organization as a whole is considered responsible for establishing, implementing and maintaining EMP without specifying administrative structure with hierarchy within the organization and assigning responsibilities (Floroiu Citation2012; Kiss Citation2013) at different levels. The periodic audit of EMP, management review of environmental compliance management, environmental performance, and ecological, social and environmental enhancement, suggested by Morrison-Saunders et al. (Citation2007) are not described. The flexibility in EMP by way of its revision (Lochner Citation2005) from time to time and mechanism of continual improvements is not evident. Best environmental management practices advocate environmental management as integral to the overall manufacturing management. However, standard pollution control systems like electrostatic precipitators, which are integral to the coal-based thermal power projects and are operated by the operation cell, are classified as pollution control systems while presenting capital and recurring budget. Like wise, good engineering practices are not distinguished from mitigation measures (Kiss Citation2013). Green belt and road-side and median plantation are wrongly termed as mitigation measures for ecology.

EMPs for expansion and diversification projects proposed in the same complex are suggested without carrying out due diligence of the operational programs and systems, environmental compliances, and environmental performance. In the absence of due diligence of monitoring and auditing programs, concrete evidence of environmental consequences of the EIA activities (Morrison-Saunders and Arts Citation2004) cannot be obtained, and shortcomings and limitations of the operational EMPs cannot be ascertained for bridging the gaps. Thus, standalone EMPs suggested for brown-field projects are mere formalities and do not serve any purpose because the suggested statements could never be turned into any action. Other finding could not be validated as no studies on EMPs of brown-field projects are found in literature.

George (Citation2000) and Ira et al. (Citation2000) had identified that the developing countries had been slow to use and implement EMPs. This state of affairs continues to be so as observed from the findings of this study that only 8.9% of the EMPs evaluated had some degree of robustness. Considering that EMP forms a more systematic and explicit document to be used by planning authorities in formulating environmental approval conditions and obligations of project proponent for ensuring mitigation implementation (Brew and Lee Citation1996, Tinker et al. Citation2005), it is very important that it is complete and of good quality. More so, because quality of EMP preparation has a strong impact on the quality of environmental compliance on the ground (Loksha Citation2008). Considering that Sadler (Citation1996) identified monitoring and follow-up as one of the four key areas for improving the EIA process, EMPs having low robustness will continue to be a weak link in the EIA process in India, necessitating immediate concerted efforts at different levels and policy interventions.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The environmental management program is specific to a project at a given location, not a generic one applicable to any project at any location as observed in several EMPs in EIA reports evaluated. reveals that the quality of EMPs in the EIA reports of green-field projects is far from satisfactory. However, the EMPs in EIA reports prepared for World Bank funding are found to be better than those seeking environmental approvals, suggesting that one of the determinants of the quality is the seriousness of the decision-making agency. The EIA consultants generally follow their own templates for developing EMP irrespective of type and scale of the project. To facilitate systematic development of EMPg for green-field as well as brown-field development projects, the elements of a typical EMPg are described at length.

EMPg is extremely important, more so in developing countries where EIA process is weak, and development projects of infrastructural, energy, and manufacturing sectors are undertaken for employment generation and improving living standards of the masses. Considering weaknesses in EIA process (Sadler Citation1996, Rathi Citation2017), a meticulously prepared, implemented, operationalized, monitored, periodically audited and continually improved EMPg, though appearing as a reactive measure, could possibly offset limitations of EIA process to a large extent. The quality of EMPg has a strong correlation with the quality of baseline data, impact assessment, and concise mitigation and monitoring measures. A robust EMPg encompassing the suggested elements is expected be balanced, objective and concise (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2014), affordable, auditable, budgeted, comprehensive, considered for preventive measures, cost efficient, feasible, flexible, implementable in a given time-frame and within allocated resources, likely to be successful, practical, realistic, simple to use, targeted, tool for promoting accountability and updatable (Lochner Citation2005).

It may be conceded that EMPg may not be complete and detailed one for green-field projects because at that stage of project life-cycle preliminary information forms the basis of preparing EIA report for seeking environmental approval. In view of this limitation, a broad frame-work covering all the required elements needs to be presented in an EMPg with the experience of consultant and project proponent, especially for the projects employing known technologies. It could be further developed and fine-tuned after obtaining conditional environmental approval and on the completion of detailed design and engineering of the project. This practice is not being followed as brought out by Floroiu (Citation2012) also. For infrastructural projects like highways, railways, energy and water resources, however, EIA report is prepared on the basis of the information available in the detailed project report, prepared after conducting detailed design and engineering of the project for seeking multilateral funding. Thus a complete and detailed EMPg could be prepared.

Once environmental approval is obtained, EIA report may be required for reference purpose only whereas EMPg document, an important part of the project’s operation manual (Loksha Citation2008) has the shelf-life as long as that of the project. In view of this, EMPg could as well be prepared as a separate document right from the EIA preparation stage to facilitate development of project manual over project life-cycle phases, and also to reassure stakeholders on the implementation of environmental approval conditions (Marshall Citation2005) and other elements. On the basis of back to back assurance from the EIA consultant, project proponent needs to give a formal commitment on implementing EMPg along with the project, maintaining it through project life-cycle, and making adequate provisions for the required resources. While undergoing public scrutiny, such a commitment ensures accountability of the project proponent in the implementation of EMPg in the committed time-frame and maintaining it, and helps in getting public acceptance to the project. The project proponent may broaden scope of work for EIA report preparation given to a consultant to include implementation, operationalization and maintenance of EMPg within the allocated resources for a certain period of time to increase accountability of the consultant (Rathi Citation2016). Such practices will also help incorporating the learnings (Rathi Citation2017) from ex-post evaluation of environmental assessment (Nicolaisen et al. Citation2016) besides ex-ante assessments, leading to robust EMPgs and improved quality EIA reports, and thereby improved decision-making processes in future.

TOR for brown-field projects need to include detailed review of various elements of the EMPg being practiced for the operating projects to facilitate preparation of additional and supplementary programs, duly integrated with the ongoing ones.

The Indian regulatory regime follows a two-step EIA process (MOEF Citation2006) in which competent authorities appraise TOR and EIA reports of the proposed projects. Considering EMPgs of low robustness and the importance of follow-up in EIA process, it may be advisable to add a third step in the currently administered EIA process whereby EMPgs get appraised before the environmentally approved projects commence construction in case of infrastructural projects and operation for other projects. The modified process will ensure that an EMPg, among others, takes into account detailed design and engineering of the project, and incorporates programs necessitated from the environmental approval conditions and other obligations. A seriously prepared EMPg, facilitating its implementation, monitoring and auditing, will help achieving the basic objectives of EIA (Sadler Citation1996), viz. protection of productivity and capacity of natural systems and the ecological processes which maintain their functions; promotion of sustainable development; and optimization of resource use and management opportunities. Mandatory third party audits of EMPgs of the operating projects will further help strengthening the EIA process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Abbot Point. 2005. Draft voluntary environmental assessment coal terminal X110 expansion. [accessed 2017 Dec 8].

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank. 2003. Environmental assessment guidelines. Manila: Office of Environment, ADB.

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank. 2011. Afghanistan regional airports rehabilitation project. Manila: Office of Environment, ADB; [accessed 2018 Feb 26].

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank. 2012. Environment safeguards: a good practice sourcebook draft working document. Manila: Office of Environment, ADB.

- [ADB] Asian Development Bank. 2017. Updated EMP Mekong (Vietnam) sub-region corridor towns development project. Manila: Office of Environment, ADB; [accessed 2018 Feb 26].

- [AfDB] African Development Bank Group. 2001. Guidelines environmental and social assessment procedures basics. Abidjan: Compliance & Safeguards Division (ORQR.3), AfDBG; [accessed 2018 Feb 26].

- Aquasure. 2011. D&C environment management plan of Victorian desalination project. [accessed 2018 Feb 25].

- Arts J, Caldwell P, Morrison-Saunders A. 2001. Environmental impact assessment follow-up: good practice and future directions. Findings from a workshop at IAIA 2000 conference. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 19(3):175–185.

- Arts J, Nooteboom S. 1999. Environmental impact assessment monitoring and auditing. In: Petts J, editor. Handbook of environmental impact assessment volume 1. Cornwall: Blackwell Science; p. 229–251.

- Baby S. 2011. Approach in developing environmental management plan. Proceedings of 2nd international conference on environmental engineering and applications IPCBEE; vol. 17. Singapore: IACSIT Press.

- [BMG] Banks Mining Group. 2015. Highthorn surface mine EMP draft. [accessed 2017 Dec 8]. http://www.banksgroup.co.uk/core/uploads/Appendix-15-Draft-Environmental-Management-Plan-1.pdf.

- Brew D, Lee N. 1996. Reviewing the quality of donor agency environmental assessment guidelines. Project Appraisal. 11(2):79–84.

- [CBD] Convention on Biological Diversity. 2005. Biodiversity in impact assessment. Information document version 5. Montreal: Secretariat of CBD.

- Choudhury N. 2014. Environment in an emerging economy: the case of environmental impact assessment follow-up in India. In: Nuesser M, editor. Large dams: contested environments between hydro-power and social resistance. Dordrecht Heidelberg: Springer; p. 101–124.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2014. Environmental management plan guidelines. Canberra: Department of Environment.

- [CSIR] Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (S Africa). 2002. Guidelines for standardized environmental management plans. Pretoria: DWAF, Directorate Social and Ecological Services. CSIR Report No.: ENV-P-C 2002-032.

- [DEAT] Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (S Africa). 2004a. Environmental management plans. Pretoria: DEAT. Integrated environmental management information series 12.

- [DEAT] Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (S Africa). 2004b. Linking EIAs and environmental management systems. Pretoria: DEAT. Integrated environmental management information series 20.

- [DEAT] Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (S Africa). 2004c. Environmental auditing. Pretoria: DEAT. Integrated environmental management information series 14.

- EIA Newsletter. 1996. Monitoring, environmental management plans and post-project analysis. Manchester: EIA Centre, University of Manchester.

- [EPA] Environment Protection Authority (Australia). 1995. Environmental management systems, best practice environmental management in mining. Canberra: Department of the Environment.

- [EPA] Environment Protection Authority (Australia). 2013. Environmental guidelines for preparation of an environment management plan. Canberra: Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate.

- Floroiu R. 2012. Environmental (and social) impact assessment instruments: presentation in World Bank safeguard workshop training held in May-June 2012. [accessed 2018 Mar 15].

- George C. 2000. Environmental monitoring, management and auditing. In: Lee N, George C, editors. Environmental assessment in developing and transitional countries: principles, methods and practice. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

- [GRI] Global Reporting Initiative. 1997. Sustainability reporting. [accessed 2018 Jan 13].

- Hollands R, Palframan L. 2014. EIA and EMS integration: not wasting the opportunity. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 32(1):43–54.

- [IAIA] International Association for Impact Assessment. 1999. Principles of environmental impact assessment best practice. [Fargo]: IAIA and IEA. [accessed 2018 Mar 4].

- [IEMA] Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. 2008. Environmental management plans. In: Practitioner. Vol. 12. [Lincoln]: IEMA.

- [IEMA] Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. 2015. EIA guide to shaping quality development. [Lincoln]: IEMA.

- [IEMA] Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. 2016. Environmental impact assessment guide to delivering quality development. [Lincoln]: IEMA.

- Ira SJT, Reid SE, Spinks AC, Blaine LA. 2000. Environmental management programs for civil engineering construction activities. Proceedings of the conference of IAIA––South African affiliate; Goudini; p. 164–175.

- Jha-Thakur U, Fischer TB, Rajvanshi A. 2009. Reviewing design stage of environmental impact assessment follow-up: looking at the open cast coal mines in India. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 27(1):33–44.

- Kiss A. 2013. Environmental safeguard instruments: presentation in World Bank safeguards training workshop held in May 2013. [accessed 2018 Aug 9]. http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01419/web/images/envsafeg.ppt.

- Lochner P. 2005. Guideline for environmental management plans. Cape Town: Department of Environmental Affairs & Development Planning. CSIR Report No ENV-S-C 2005-053 H.

- Loksha VB. 2008. Environmental management planning: an integrated results-oriented process––discussion material for Moldova safeguards training workshop held in Oct 2008. [accessed 2018 Mar 7].

- Magnox North Ltd. 2009. Environmental management plan, Oldbury power station. Oldbury Naite: Magnox North Ltd.; p. 39. [accessed 2018 Feb 26]. BS35 1RQ (2).

- Marshall R. 2005. Environmental impact assessment follow-up and its benefits for industry. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(3):191–196.

- [MOEF] Ministry of Environment and Forests. 2006. Environmental impact assessment notification. New Delhi: MOEF.

- [MOEF] Ministry of Environment and Forests. 2012. Environmental management plan. [accessed 2017 Dec 8].

- [MOEF] Ministry of Environment and Forests. 2014. Online submission & monitoring of environmental clearances. [accessed 2018 Apr 6].

- Morrison-Saunders A, Arts J. 2004. Exploring the dimensions of EIA follow-up. Presented at: IAIA’04 Impact assessment for industrial development whose business is it? 24th annual meeting of IAIA; Apr; Vancouver; p. 24–30.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Marshall R, Arts J 2007. EIA follow-up international best practice principles. Fargo: IAIA. Special publication series No. 6.

- Nicolaisen M, Fischer TB. 2016. Editorial in special issue on ex-post evaluation of environmental assessment. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 18(1):1601001 (4 p).

- Parkes L, Solomons M, Spinks A, Luger M. 2001. Are EMPs facilitating environmentally responsible development, or just window dressing? Proceedings of the IAIAsa Conference in White River, IAIA ––South African Affiliate; p. 223–224.

- Perdicoulis A, Durning B, Palframan L. 2012. Furthering EIA ––towards a seamless connection between EIA and EMS. [Cheltenham]: Edward Elgar.

- Rathi AKA. 2009. Hazardous waste management. In: Anand S, editor. Current trends in engineering practice. Vol. II. New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House; p. 527–548.

- Rathi AKA. 2016. Environmental impact assessment: a practical guide for professional practice. Ahmedabad: Akar Unlimited.

- Rathi AKA. 2017. Evaluation of project-level environmental impact assessment and SWOT analysis of EIA process in India. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 67:31–39.

- Sadler B. 1996. Environmental assessment in a changing world: evaluating practice to improve performance. Ottawa: IAIA and Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. Final report of the international study of effectiveness of environmental assessment.

- Shah A. 2009. Environmental management plan. [accessed 2017 Dec 8].

- Tinker L, Cobb D, Bond A, Cashmore M. 2005. Impact mitigation in environmental impact assessment: paper promises or the basis of consent conditions? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(4):265–280.

- [UNEP] United Nations Environment Program. 2002. Environmental impact assessment training resource manual. 2nd ed. Geneva: Division of Technology, Industry and Economics, UNEP.

- [USAID] U.S. Agency for International Development. 2005. ENCAP EA-ESD course: basic concepts for EIA environmental mitigation and monitoring. [accessed 2017 Dec 8].

- [WB] World Bank. 1999a. Environmental management plans. Washington (DC): Environment Department, WB. Environmental assessment sourcebook update no. 25.

- WB, World Bank. 1999b. Environmental management plan. OP 4.01, Annex C. [accessed 2018 Mar 7].