ABSTRACT

Discussions on effectiveness have been around in impact assessment for many years, blending multiple perspectives. This paper is about the effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) in Portugal. The adopted framework was set by the editors of this special issue and this paper is contributing results obtained through a questionnaire shared with SEA professionals in Portugal, and also from discussions held in a workshop promoted by the Portuguese national authority on SEA. We have tried to understand the influence of SEA in development processes and the perception on SEA added-value to both environmental authorities and other relevant stakeholders in Portugal. Results are mixed and somehow reveal some confusion between expectations with what SEA aims to achieve, and with what it is actually delivering, which question its effectiveness, as expressed by some opinions that SEA ‘magic may be fading away’. However, other outcomes, such as the recognized need for better communication and increased capacity-building, support the conclusion that most SEA practice and experience in Portugal are yet far from SEA full capacity and potential.

1. Introduction

Effectiveness is the most covered topic of concern and research in impact assessment (IA) literature over the past years (Fisher and Onyango Citation2012). An exploratory search of ‘strategic environmental assessment’ (SEA) and ‘effectiveness’ in online scientific databases (ScienceDirect, Web of Knowledge, Scopus) for the publication period between 2000 and (24 July of) 2018 resulted in a total of 73 publications, with a systematic increase in publications every year, except for 2016 and 2017 (see ). In this sample, it appears that the predominant discourse on procedural effectiveness is taking place in Europe (see geographical distribution of papers in ).

The reasons for why effectiveness is a major topic of concern in IA for many years may be relatively easy to understand and accept. IA is a public instrument with the fundamental role of assuring that environmental concerns and priorities are well recognized and integrated in development decision-making. If IA is not effective, then it is a waste of public resources. However, making sure it is effective is less simple and obvious, because IA is complex, because its perception is context dependent, and also because there are various ‘measures’ of effectiveness, and not all are fully understood and acknowledged.

A vast number of frameworks have introduced effectiveness, including performance criteria (Fischer Citation2002; IAIA Citation2002), impact on decision-making (Runhaar and Driessen Citation2007), SEA effectiveness criteria (Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; van Buuren and Nooteboom Citation2009; Stoeglehner Citation2010; Wang et al. Citation2012; Van Doren et al. Citation2013), transformative potentialities (Cashmore et al. Citation2008), checklist for effectiveness (Theophilou et al. Citation2010; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013), successful strategic thinking (Partidário Citation2012), sustainability assessment effectiveness (Bond et al. Citation2015 revised in Pope et al. Citation2018), good SEA (Bidstrup and Hansen Citation2014), SEA efficacy (Acharibasam and Noble Citation2014), effective IA (Hanna and Noble Citation2015), or dimensions of IA quality (Bond et al. Citation2018). Even under different labels, it is consensual that the need to understand what is effectiveness and what is an effective IA instrument. Also consensual is that effectiveness is a context-influenced notion, with the context affecting effectiveness, but also how it is perceived (Bina Citation2008; Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; Runhaar and Driessen Citation2007; Elling Citation2009; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013).

This paper shares results of an analysis on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal in relation to its legal and practice context. Like all European member states, Portugal adopted national legislation on SEA in 2007, following Directive 2001/42. In the same year, and in parallel with the legal enactment of SEA, the Portuguese authority responsible for SEA (Portuguese Environment Agency – APA) adopted methodological guidance on good practice SEA. The purpose was to assist practice with a methodology that would explore the strategic potential in SEA, distinct from conventional IA with the effect-based assessment rationale, and beyond procedural verification and control.

While a systematic review of SEA practice is missing in Portugal, it appears, from results shared ahead, that the guidance has only had a limited influence in the dominant perception of SEA. Consequently, SEA outcomes in Portugal fall short of the constructive and positive role SEA can play in development processes, as promoted by the guidance. This context influences the perception on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal, as revealed in the analysis results shared in the following sections. The paper follows with a short outline on the practice of SEA in Portugal, based on available reviews. The method used to collect empirical evidence to support the analysis of the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal is presented, before results are shown and discussed, and conclusions drawn.

2. SEA in Portugal: evolution and state of play

The APA has been the responsible agency for the application of national requirements on SEA since the enactment of the Portuguese legislation 11 years ago. It is also APA’s responsibility to keep records of SEA practice and disclose information regarding SEA process and practices. The formal information available is however limited and the analysis of the evolving situation on SEA in Portugal needs to refer to multiple sources, much of which has been produced in an academic context.

The practice of SEA in Portugal was very slow before the establishment of its legal framework. Only a couple of SEA cases were developed before 2007, a fact that acknowledges Sheate et al.’s (Citation2001, p. 85) statement that most SEA generally occurs where there is a legal obligation that requires it. But the limited initial practice was however important to start experiments and discussions on how SEA could be designed to fit the national planning and development culture.

Portugal transposed the European Directive 2001/42/EC through the enactment of Decree-Law 232/2007, of 15 June, subsequently modified by Decree-Law 58/2011, of 4 May, in a way that fundamentally mirrors the Directive. Additional requirements on SEA for spatial planning have been established through specific spatial planning legislation since 2007, the latest update with Decree-Law 80/2015, of 14 May. This includes requirements for the presentation of information in environmental reports as well as institutional and public consultation to be conducted during the formulation and before the approval, and implementation, of spatial plans.

Efforts have been made by APA to influence the practice of SEA by publishing in 2007 a good practices guidance (Partidário Citation2007). While ensuring legal requirements, the guidance is non-procedural and therefore not intended to the verification of legal procedures. The objective of the guidance is to create capacities in using SEA as an instrument that can add value to decision-making, placing greater emphasis on the strategic role that SEA should play in helping to incorporate environmental concerns in development processes. The guidance places the start of any SEA at very early moments in the planning and programme development processes and stimulates its continuous role in facilitating more environmentally integrated planning and programming, oriented by sustainability objectives. This way SEA could play its role in reducing, or even avoiding, undesirable environmental effects of planning and programme proposals in a constructive, rather than in a controlling way. This 2007 guidance was subsequently revised in 2012 (Partidário Citation2012), following consultation with Portuguese environmental and planning authorities, to reinforce the strategic thinking in SEA, and the methodological guidance was adjusted accordingly.

Concerning the current state of play with SEA in Portugal, according to the national state of the environment report (REA Citation2018) between June 2007 and December 2017, about 690 SEA processes were initiated. However, APA only has registries for 262 published environmental statements (see temporal evolution of the environmental statements in ). Among the 262 processes that issued the environmental statement, about 84% are municipal planning instruments, 13% sectorial plans and programmes, and 3% operational programmes.

Figure 3. Environmental statements registered in APA between 2007 and 2017 (source: REA Citation2018).

Some studies have been made in Portugal along the years concerning the application of SEA. In 2010, a study was commissioned by APA to report on the developed practice of SEA between 2007 and 2009 (Partidário Citation2010). In 2011, within research developed for a master thesis, an analysis of actor’s perceptions with respect to the contribution of SEA to the planning process was conducted (Monteiro Citation2011). And in 2013, a review of 87 SEA environmental reports, through an analytical framework of 10 assessment criteria for successful SEA (based on Partidário Citation2012), was developed by the authors, with results presented in the 33rd Annual Conference of IAIA. Overall these studies showed that (a) as a common practice, SEA was used only with the final planning proposals (a consequence of late SEA); (b) almost none of the cases analysed considered institutional responsibilities or promoted effective and broad public participation and stakeholders’ engagement; and (c) SEA was perceived as a control instrument of legal compliance. These results suggest that the national SEA guidance orientations seem to be overlooked in practice.

More recently, in 2016, research was conducted with the purpose of assessing consistency with respect to the contents of SEA environmental reports for similar typologies of plans (Fidélis et al. Citation2016). Findings revealed that different plans of the same typology (river basin plans) that engaged a common set of stakeholders show profound differences in relation to the SEA ontological and terminology uses. According to the authors, this may possibly ‘hinder the understanding of the SEA process (…) and discredit its added value’ (Fidélis et al. Citation2016, p. 33), resulting in a stakeholder’s ‘apprehension of SEA’ (Fidélis et al. Citation2016, p. 32).

When looking at the current practice and experience with SEA in Portugal, it appears that the methodological orientations of the guidance are followed in its form but not in its philosophy. As it will be shown in subsequent sections, while some practice reveals the use and application of the spirit of the methodological guidance, in general only the terminology used in the guidance is adopted. SEA practice, as well as its institutional climate and culture, appears to remain influenced by conventional thinking of IA driven by a logic of effects assessment, as established through the regulatory requirements, with SEA often seen as a legal obligation to be complied with, and to be avoided whenever possible.

3. Method

The analysis of the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal followed a participatory approach based on the use of two methods: (A) inquiry by questionnaire and (B) conversational dialogue through a cooperative discussion on the state of SEA effectiveness in Portugal. This paper follows Cashmore and Axelsson’s (Citation2013) suggestion that SEA instruments are ‘social constructs’. This means that SEA-related actors are an active and dynamic part of the SEA context, which justifies the need to understand and explore the practitioners’ perspectives and opinions about the subject in analysis. Supported by this rationale, the participative methods used allow to uncover specific patterns of thinking that may characterize the Portuguese practice.

The paper explores the perspectives of Portuguese SEA-related actors with more emphasis from a non-procedural effectiveness. The effectiveness categorization laid out in the introductory paper of this Special Issue, in line with Bond et al. (Citation2015), was used as the groundwork for analysis of the actors’ perceptions. Each of the seven effectiveness categories – contextual, procedural, substantive, transactive, normative, pluralistic, and learning and knowledge – has been used when structuring the research methods, as shown in . The following sections explain the development of each method used.

Table 1. Effectiveness consideration in the research methods.

(A) Inquiry by questionnaire

To capture individual perceptions on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal, in a simple and expeditiously manner, an inquiry by questionnaire, constructed with an open- and closed-ended structure, was applied. Between 19 July and 14 September of 2018, the questionnaire was distributed online (with resource to an online platform) and disseminated with the support of the APA, the national authority for SEA. The sampling process was ‘purposive’ (Charles Citation1998) as it seeks to target individuals with an explicit relation with SEA – administration, consultants, plan and programme promoters, decision makers, researchers, etc. The questionnaire is organized around 18 questions including the respondents’ backgrounds and experiences with SEA, and general questions about SEA effectiveness (the full Questionnaire is included in Annex 1). The questionnaire was developed based on the outline framework provided by the Special Issue Guest Editors and then adjusted to better fit the Portuguese reality.

(B) Conversational dialogue

To observe and explore interactions and reactions between SEA-related actors in real-time context, a conversational dialogue was promoted on 7 September 2018, with the support of the APA. The invitation to participate in this session was sent to the same individuals targeted with the questionnaire. Among the 34 participants in this session, only a few (less than a quarter) had completed the questionnaire, which reduces the chances of overlap or duplication in opinions expressed. The flow of the dialogue was constructed around the questionnaire main thematizes. The session started with a short presentation on preliminary results of the questionnaire and was followed by two and a half hours of open discussion, supported by leading questions. During the session, concerns on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal were shared by all 34 participants.

4. Results achieved

In this section, the results with the application of the two different participatory methods used are separately presented. In the next section, a joint discussion of the results is conducted.

4.1. Questionnaire

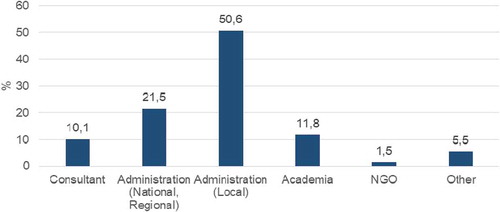

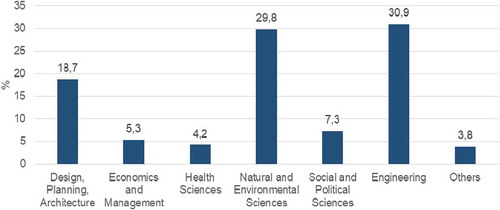

The questionnaire was disseminated, with the support of APA mailing contacts, to 590 people (including entities with environmental responsibilities, non-governmental organizations, municipalities, consultants, academics, and other entities of central administration). A total of 245 responses were received, of which only 122 were considered admissible for analysis, resulting in a response rate of almost 21%. We excluded responses considered insufficient, largely those that only responded to the initial personal background questions. In Annex II, the complete outline of the responses obtained can be found.

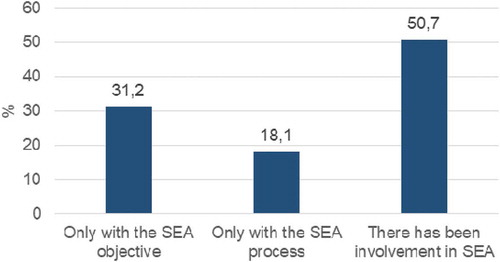

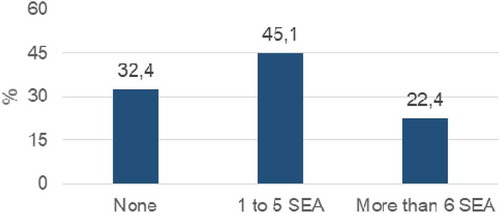

Results reflect at least 11 years of practice with SEA, since the enactment of legal requirements. But they also reflect very different experiences. The sample can be generally characterized by a majority of respondents from public bodies with a low level of experience with SEA, and a moderate familiarity with the SEA instrument. About 51% have been actively involved in SEA while the other 49% are only familiar with the objective or the process of SEA. Most respondents have been involved in less than five SEA (45%), and only about 22% in more than six SEA (see Annex II for results).

In addition, the fact that only 40% of the questionnaires disseminated were responded and of those only 50% were completed beyond the initial section of personal identification could be considered a proxy indicator to a moderate-to-low familiarity and experience with SEA in Portugal.

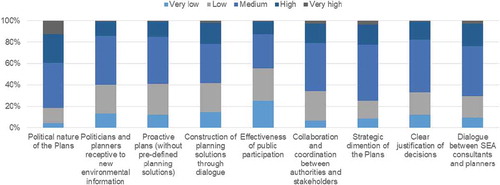

As shown in , about 40% of respondents consider that plans have a high to very high political nature and only 20% consider plans to be high to very high in strategic nature. This is consistent with the recognition that SEA works typically with reactive plans (only approximately 15% are considered to be proactive with no predefined planning solutions), constructed with a low practice of dialogues for the search of planning solutions (40% considered low to very low this practice of dialogue).

The decision-making culture is perceived to be relatively centralized and not very open to environmental information. Only 15% of the respondents consider that there is a clear justification of decisions, while politicians and planners are not really receptive to new environmental information (only 15% consider high to very high receptivity), even though about 25% admit a high to very high interaction between planners and SEA consultants through dialogues. Also, about 56% of the respondents consider that SEA is carried out in contexts where public participation processes are mostly ineffective ().

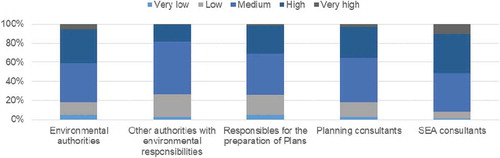

The technical capacity in place to work with the instrument of SEA (skills or ability with) is essential to understand the effectiveness and success of its application. Overall respondents consider that environmental authorities, planning consultants, and SEA consultants have high capacities to work with SEA, while a more modest ability can be observable in other authorities with environmental responsibilities, and also in authorities responsible for the preparation of the plans ().

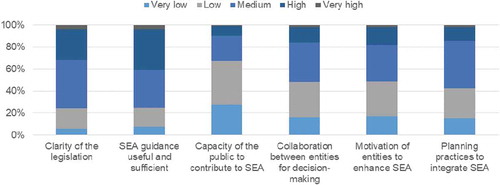

This perception is however quite different with respect to the institutional context (): while about 40% acknowledges the usefulness and sufficiency of the national guidance, the respondents recognize that national legislation needs improvement in the clarity of the regulatory procedures. Half or almost half of the respondents consider that there is a low to very low collaboration between entities involved in decision-making, as well as low to very low motivation of these entities to enhance SEA application. also reveals that about 67% of respondents recognize that the public has a low to very low capacity to contribute to SEA.

With respect to the expected role of SEA in the planning process, responses reveal that the integration of environmental issues in the plan is the most mentioned role (around 46% of respondents). However, others also refer to the role of SEA in helping to prioritize (15%), identify and assess strategic options (13%), increasing transparency (9%), helping to set a monitoring plan (7%), and providing clarity to the planning process (7%). Interestingly, about 13% of respondents consider that SEA does not make any changes to the plan.

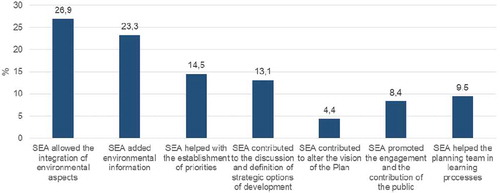

In relation to the influence SEA has on the development of plans and programmes, it appears actual changes made in the plan as a result of SEA are hard to know since both environmental reports and plans provide very little indication on the interactive process followed and changes adopted (see results available in Annex II). Nevertheless, when questioned about how SEA was seen to influence the elaboration of plans, the majority answered that SEA allowed the integration of environmental aspects in the plan (27%) or that SEA added environmental information to the plan (23.3%). A much smaller group (14.5%) referred to the SEA influence in establishing priorities or in contributing to define and discuss strategic options (about 13.1%). Even a smaller group see the influence of SEA in learning processes (9.5%) or in promoting public engagement (8.4%), while 4.4% recognize that SEA can contribute to change the vision of the plan.

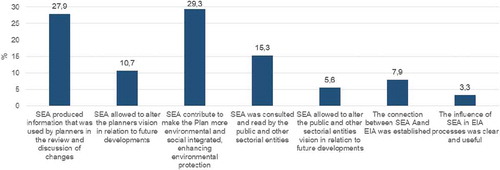

Similar questions were asked in relation to the influence SEA can have during the implementation of the plan. In this case, 29.3% recognized that SEA contributed to make the plan more environmentally and socially integrated while about 28% consider that the information produced by SEA is used by planners in the review and discussion of emergent changes. About 15.3% see SEA as influencing the opinions of the public and of other sectorial entities during the implementation of the plan. Much less recognize the capacity of SEA to change planners vision (10.7%) or the public and other sectors vision (5.6%) on future developments. Interestingly, only a minority see the connection between SEA and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) being established (7.9%) or having SEA influencing the EIA (3.3%).

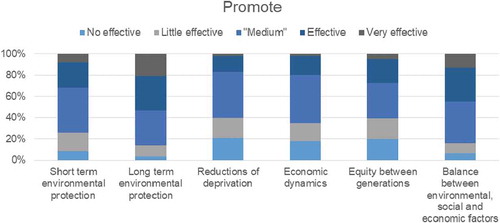

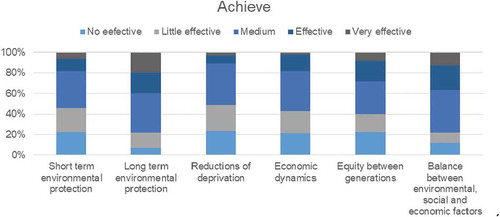

When comparing long- and short-term influence of SEA, the majority of respondents seem to consider SEA to be effective in promoting and achieving long-term environmental protection, as well as in balancing between environmental, social, and economic factors, but it proves to be unable to promote and achieve reductions in deprivation and equity between generations (see results in Annex II). While some respondents recognize that SEA can have a potential to promote short-term protection, about 46% considers that SEA is ineffective in actually achieving this.

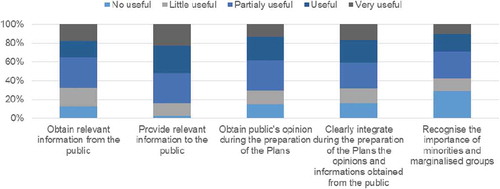

Portugal could be considered a country with relatively low public participation culture. As revealed, the public is perceived as a stakeholder with low capacities to participate in SEA processes. So, no surprise to verify that almost 60% of respondents considered public participation effectiveness low to very low (). SEA is clearly seen as an information provider, with more than 50% of respondents considering SEA useful in making relevant information available to the public. There is less clear positioning in terms of the role of SEA in obtaining information from the public (very high to high, medium, and low to very low each representing 1/3 of responses), while the situation gets better in relation to obtaining the opinion of the public (38.3% in high to very high) or in terms of incorporating both the opinion and information obtained from the public in the plan (31.1% high to very high). In addition, the opinion of minorities and marginalized groups are largely considered non-useful (29%).

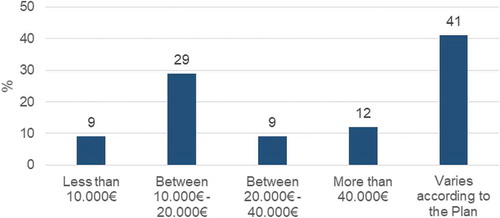

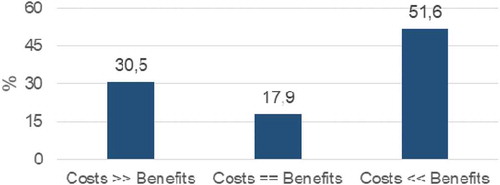

In relation to costs of SEA, about 41% of respondents consider the costs to vary according to the plan (possibly dependent on its scope of application, nature, strategic importance, etc.) and 29% suggest that doing an SEA can cost between 10,000€ and 20,000€. When comparing the benefits and the costs from the application of SEA, the majority of respondents (about 52%) are of the opinion that the application of SEA has more benefits that costs. However, it is worth mentioning that 30.5% consider that costs outweigh the benefits.

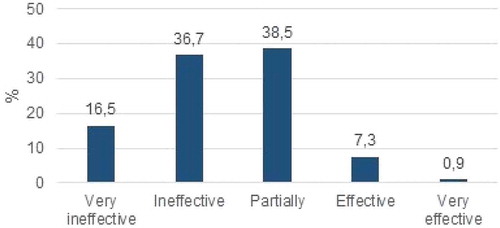

Finally, in response to a direct question on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal, respondents appear to consider that SEA is predominantly ineffective ().

Two open questions in the questionnaire reveal respondents’ perception, and opinion, in relation to what makes an SEA effective, or to what may impede an effective SEA. For nearly 30% of respondents, the most important criterion for an effective SEA includes the promotion of public participation and institutional cooperation and is also about SEA being contextualized and integrated with the decision-making process. The political willingness of decision makers and established power dynamics are, for 20% of respondents, other criteria for an effective SEA.

Through another open question, respondents were asked about which, in their opinion, are the most common impediments to an effective SEA. Interestingly, the political and cultural context of SEA, defined in relation to decision, planning, and power distribution, appears to be seen as an impeding factor for 29% of respondents. And about 23% identify that the legal compliance dependency of decision makers, authorities, and consultants can act as an impeding factor, together with the established institutional and technical capacities for SEA (in this case identified by 21% of respondents).

includes the top three responses to each question, providing a good illustration of the six top aspects perceived as influential of SEA effectiveness: public participation and institutional cooperation, integration in the decision-making, political willingness and power dynamics, political and cultural context, legal compliance attitude, and institutional and technical capacity for SEA. It is interesting to note the relevance of the political dimension as a condition for effectiveness (political willingness) and as an impediment to effectiveness (political context).

Table 2. Top three responses in open questions regarding SEA effectiveness in Portugal.

Examples of effective SEA processes were provided by respondents. The most mentioned include the cases of the SEA of the revision of the Sintra municipal master plan (public planning instrument of local nature) (CMSintra Citation2018), of river basin management plans (public sectorial instrument of regional nature) (APA, Citation2018), or of the development and investment plan of the electricity transport network (private sectorial plan of national nature) (REN, Citation2011).

Drawing on these opinions and the above results, the reasons and arguments around SEA effectiveness will be discussed in the next section.

4.2. Conversational dialogue

On 7 September 2018, a conversational dialogue took place in APA with 34 attendees from environmental authorities, national and regional administration, academia, SEA consultants, private entities, and municipalities. It was an open dialogue, structured around five themes: strategic nature of plans and planning processes, added value of SEA, public participation, proactivity of SEA, and capacity for SEA.

The dialogue started with a question asked to participants: ‘what is, for each of you, the added value of SEA’? Each participant was asked to provide one word or expression to answer the question and in real time a word cloud was created (), showing sustainability outcomes, changes, engagement, integration, and governance as the most important aspects considered as an added value of SEA in development processes.

The participants in the session recognized that in Portugal, as in many other countries in the world, plans subject to SEA are not very strategic in terms of their long-term view, adaptation, flexibility, and capacity to deal with emerging situations (Partidário Citation2012), although it is recognized that many have at least a strategicness potential. This lack of strategicness in plans is consistent with the questionnaire results and was seen as an important factor in influencing the outcomes of SEA, recognizing that strategic assessment capacity in SEA becomes limited by plans and programmes operational and technical nature. It was clearly stated that SEA is not properly applied when the assessment rationale is very similar to a big EIA, when aiming to find effects that can be mitigated, and where the long-term perspective and the consideration of alternative options of development are largely absent.

The perception is that SEA, in theory, has the potential to promote the development of more environmental- and sustainability-oriented plans and programmes. But, in general, this is not happening in the SEA practice in Portugal, part of the reasons given included that SEA starts very late in the planning process and is essentially separated from planning, missing the opportunity to create an added value. As discussed in the session, one probable cause for this to happen is the generalized perception of SEA as a compliance instrument mandated by law.

As previously mentioned, this happens because of the view of SEA as a regulatory procedure (instead of an orientation for long-term integration) contributing to ineffective SEA. Also, there is reduced cooperation between teams. The common practice is the insufficiency, or total absence, of cooperation and communication between the planning and the SEA teams. As one participant mentioned ‘the information produced in one side do not cross with the information of the other side’. The SEA and planning or programme development processes are independent, parallel but separate and take place, usually, without the teams having met.

The relationship between teams was considered essential to change mentalities, away from seeing SEA as an obligation only. A direct and continuous link between processes may help decision makers and planners to recognize the potential of SEA, to help with learning about the institutional capacities of SEA. Without the recognition of the benefits, SEA can bring to planning and to development processes; SEA is just a simple exercise of legal compliance.

It was further discussed that decision makers and planners have a low degree of openness to let SEA influence the plan. And, consequently, decision makers and planners avoid integrating stakeholders with different interests and expectations when using SEA. In addition, the Portuguese SEA legislation does not really promote public participation, only consultation, with very short deadlines and only on the environmental report, which inhibits collective thinking about future developments, and impedes dialogue – this is also a consequence of late SEA (one participant labelled it as the ‘stigma of closed processes’). Participants considered that public participation in SEA is ineffective for various reasons: (a) cultural mentalities, (b) reduced willingness of decision makers and planners to have open and transparent processes, (c) public feeling that their contributions will have little to no influence in final outcomes, or even (d) the low level of motivations and interests in anything that is not ‘on my backyard’.

It was agreed that effort must be placed in encouraging effective communication, adjusting information and language to the target audience. Also, that the public (and all the stakeholders) must feel that their participation is effectively useful is adequately considered and influences the development process – ‘people need to feel that their contribution had the desired effect by seeing their inputs reflected in final products’ was one of the comments.

One of the clear perceptions among participants in the session was that decision makers and planners are not ready to ‘think SEA’ and that they need capacity-building initiatives to be able to do better plans by acknowledging the importance of the SEA. The still predominant rational is of SEA as a ‘big EIA’. It was also argued that this mentality may be influencing public participation processes and outcomes. Public participation should be adapted and adequate to the type and scale of the instrument being used and assessed. One participant said that ‘speaking about capacity in SEA may be a discussion trapped in a vicious cycle’ and then explained – there are existing capacities for the current legal procedural driven practice, but not if the aim is to improve SEA to its full potential. If that potential is not being explored or implemented, then it will be difficult to recognize the need for SEA capacity-building. Environmental authorities and entities with environmental responsibility know about the ‘legal tool’, and about the current practices of the legal procedure, but knowledge about new ways of dealing with SEA, and about new scientific knowledge, is still not part of their scope of attention.

Overall participants in this session are of the opinion that SEA is (still) ineffective. There is the need to share good practices for replication, innovation in procedures and probably in the SEA national system, to work on capacity-building and on change of mentalities. Also, Portuguese SEA practice normally ‘ends’ with the publication of the environmental statement, a situation that needs to change by acknowledging the importance of follow-up to improve SEA effectiveness.

5. Discussion

Outcomes of both the questionnaire and the conversational dialogue reveal SEA effectiveness as an environmental information provider to the planning process. This SEA feature, in responses obtained, is usually linked to the influence of SEA in the plan elaboration and implementation, as well as to how SEA contributes to integrating environmental issues in decision-making. It appears therefore that, at least to some respondents, the integration of environmental issues in decision-making means to provide environmental information.

But in both the questionnaire and the conversational dialogue, SEA is overall considered ineffective in Portugal. Conditions for effectiveness and impediments to effectiveness were identified by respondents, based on an open question (results in ) that enabled a free reaction, even though of course somehow influenced by the dominant themes being addressed and discussed. Public participation and institutional cooperation, integration in decision-making and contextualization as well as political willingness and power dynamics were the top conditions identified as criteria for an effective SEA.

Considering most of these aspects were found insufficient, in both responses and dialogues, in the practice of SEA in Portugal, this leaves little doubt on where priority needs to be placed to improve the practice of SEA. Integration in decision-making could be seen as an exception, since respondents seem to link integration to adding environmental information, which they find to be effective (as in paragraph above). However, if we consider that integration in decision-making should also relate to the degree of openness to let SEA influence the plan, to the practice of dialogues and interactions between planners and SEA teams, and among entities involved in decision-making, to the low receptiveness to environmental information by decision makers and planners, that even appear to resist to the introduction of changes in the plan vision or proposed solutions, presumably more integrated, all of which are rated as low in results shared above, then perhaps integration of the environmental issues in decision-making in Portugal is not that effective after all.

In the same open question (results in ), respondents identified the political and cultural context of SEA, the legal compliance attitude, and the institutional and technical capacity for SEA as common difficulties that may impede an effective SEA. Interestingly, among reasons identified in the conversational dialogue on why public participation is ineffective, one is the lack of political willingness in having transparent decision processes, other is low practice of dialogues, which are entirely contextual and linked to the centralized nature of the decision culture. Conditions that do not stimulate dialogues may be inhibitors of collective thinking about future developments, limiting full and active engagement, which is essential provided the complexity of issues in SEA. No surprise then to see also references to the low motivation of entities involved in decision-making to become engaged, and get ownership, of SEA.

It is also interesting to note that the kind of plans that require SEA are mostly considered to be highly political in nature, but with a weak strategic dimension. This can be justified by the fact that plans appear to be driven by politicians’ short-term priorities, wishes, and opinions, however without really setting longer term development policies in a systematic and transparent way. Consequently, plans are mostly reactive, consistent with a relatively centralized decision-making culture, with insufficiently clear justification of decisions, and, as mentioned, not very open to environmental information and to establish interactions with stakeholders. This political and cultural context of SEA, too glued to legal requirements, with centralized decision-making and low power dynamics and distribution, become a pool of factors that impede SEA effectiveness.

While the role of SEA during the elaboration and implementation of plans is seen mostly in relation to adding information, other perspectives reveal an emerging yet different understanding of the role of SEA being recognized in Portugal. This is particularly expressed in SEA capacity to help to prioritize, identify, and assess strategic options, enabling monitoring and improving transparency, sometimes changing the vision of the plan or enabling learning processes of planners, consultants, authorities, and other stakeholders in linking SEA and development processes. This is interesting and can be interpreted as revealing the influence of the Portuguese good practice guidance in generating a different culture (Partidário Citation2007, Citation2012) in SEA development, since prioritization and identification and assessment of strategic options are core activities of SEA in the guidance, however not explicitly required in the legislation. But which are identified by respondents among the top three changes SEA could bring to a plan.

Around 13% of respondents considered however that SEA does not make any changes to the plan. This could be justified, at least in part, by the fact that actual changes made in the plan as a result of SEA are hard to notice by external observers, since both environmental reports and plans provide very little indication on the interactive process followed and changes adopted.

Interesting also to note, in results above shared, a recognition of existing technical capacity for SEA among environmental authorities, SEA and planning consultants, but less capacities among other intervenients in the SEA and planning processes. Yet, as commented in the conversational dialogue, the existing capacities are adequate for the kind of dominant conventional SEA practice currently taking place, but insufficient for an improvement of the several weaknesses already revealed. On the other hand, there may be a misunderstanding between being able to do an SEA or having sufficient technical capacity to conduct SEA. As one participant in the conversational dialogue emphasized, perhaps the technical capacity exists for running SEA as a legal tool but not really to use new ways of dealing with SEA, using new scientific knowledge.

Results achieved also show a perception of low institutional capacity for SEA. This may ultimately relate to the established institutional culture of complying with the legislation, starting late, insufficient dialogues, keeping separate and independent processes, thus missing opportunities to enable SEA to bring an added-value to decision-making. As participants in the conversational dialogue indicated, thinking SEA as a strategic instrument is still absent.

Finally, in relation to the influence of SEA in EIA processes, the majority see no connection or usefulness of SEA in relation to EIA. Why is this? Considering one of the oldest arguments for using SEA, and actually also a legal reason, is to enable better conditions for the development on projects’ EIA, this result should be troubling. But if we connect this result to the perception of SEA as a big EIA, with SEA remaining influenced by the conventional thinking of IA driven by a logic of effects assessment, and also the low capacity of SEA to change the public and other sectorial entities vision in relation to future developments, then we may question: is SEA actually doing what it should be supposed to do, being different from EIA, acting as a strategic instrument as its own name suggests? One possible answer is that, in practice, SEA is mirroring, and generally replacing, EIA, and consequently, EIA is not seen as a sequence to SEA. Perhaps obtained results suggest the general idea that there is no more need for EIA when you have an SEA!

For this and other reasons, the needs for more capacity building and improved communication were recognized in the conversational dialogue in order to stimulate the use of SEA as an instrument that provides strategic orientation into long-term developments.

provides a summary of the core outcomes on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal for each category of effectiveness being considered in this Special Issue. These categories assisted the preparation of the questionnaire and set the context for discussions in the conversational dialogue. The presentation of results and the discussion did not follow this division in separate sections for each effectiveness category. We found it hard to allocate many topics into single categories of effectiveness. For example, public participation can be seen as procedural (a step in the process), transactive (public capacity to provide inputs to SEA), normative (related to the social norms), pluralistic (the multiple values represented), knowledge and learning (sharing and mixing different knowledges), and of course, like almost any other aspect, it is contextual (context specific to organizational and decision culture). Nevertheless, attempts, at least, to provide a structured comparison with other experiences in the special issue, assuming the same interpretation of each effectiveness criteria is followed by all authors.

Table 3. Concluding analysis on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal.

6. Conclusions

A quick real-time perception exercise among participants in the conversational dialogue showed that sustainability outcomes, changes, engagement, integration, and governance are the top five aspects considered to be an added value of SEA in development processes. At least in theory, the notion of effective SEA in Portugal relates to the promotion of public participation and institutional cooperation and also to SEA being contextualized and integrated with the decision-making process, with the political willingness of decision makers and power sharing being important conditions for effective SEA.

But the analysis conducted on the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal reveals that, in reality, the above conditions lack behind what is needed. Outcomes achieved identify the political and cultural context of SEA, defined in relation to the decision and planning culture, and also the power distribution issues, as impeding an effective SEA. Likewise, the decision makers, authorities and consultants’ legal compliance dependency, and the established institutional and technical capacities for SEA were other fundamental arguments offered to justify the ineffectiveness of SEA in Portugal. There are existing capacities for the current legal procedural-driven practice but not for an improved strategic potential of SEA.

Worth noting is the consistency between the results obtained on the effectiveness of SEA through the questionnaire and the results obtained through the conversational dialogue. Three aspects stand out from both sets of results: the ineffectiveness of public participation and stakeholder’s engagement, the insufficient integration of SEA in decision-making (late start and parallel independent processes), and the planners and decision makers perception of SEA as a big EIA, mostly driven by regulatory compliance.

Interestingly, a contrasting notion of SEA appears to be revealed in the results obtained, distinguishing between the positive notion enabled by SEA full (theoretical) potential, and the negative notion made evident through its current real practice. SEA has been recognized to have the potential to promote the development of more environmental- and sustainability-oriented plans and programmes but, in general, that is not happening – in part because SEA starts very late in planning process and is essentially separated from planning, missing the opportunity to create an added value. In Portugal, there seems to exist a generalized perception of SEA as a regulatory procedure, a compliance instrument mandated by law.

The attempt to make SEA influential of the concept of planning and programme, both in relation to integrating environmental aspects as well as in relation to help a more sustainable development, requires major changes in mentalities, and the creation of an institutional culture for SEA. It also requires changes in the most frequently used tool-boxes, still dominantly driven by conventional IA. Unfortunately, the result of maintaining old school IA practices, based on logics of control of environmental effects, contributes to a persisting idea of SEA as a barrier that creates difficulties to development, seen as a waste of time and resources that really does not bring any added-value.

Changing this notion requires acceptance that SEA should not be limited to a biophysical environmental scope or to the assessment of effects, that SEA should be used as a companion instrument to encourage and foster more integrated and sustainability-driven development, to help planning processes building more integrated, interactive, and sustainable ways forward, recognizing multiple scales and values, with public participation fully assumed through active engagement, adapted and adequate to the type and scale of the SEA and planning instruments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Portuguese Environment Agency (APA – Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente) for their support in the dissemination of the questionnaire and organization of the conversational dialogue, as well as to all participants in both engagement moments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Acharibasam JB, Noble B. 2014. Assessing the impact of strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 32(3):177–187.

- APA (Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente). 2018. Planos de Gestão de Região Hidrográfica – 2.º Ciclo; [accessed 2018 Sept]. http://www.apambiente.pt/index.php?ref=16&subref=7&sub2ref=9&sub3ref=848.

- Bidstrup M, Hansen A. 2014. The paradox of strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 47:29–35.

- Bina O. 2008. Context and systems: thinking more broadly about effectiveness in strategic environmental assessment in China. Environ Manage. 42:717–733.

- Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A. 2015. Introducing the roots, evolution and effectiveness of sustainability assessment. In: Morrison SA, Pope J, Bond A, editors. Handbook of sustainability assessment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; p. 3–19.

- Bond A, Retief F, Cave B, Fundingsland M, Duinker PN, Verheem R, Brown AL. 2018. A contribution to the conceptualisation of quality in impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:49–58.

- Cashmore M, Axelsson A. 2013. The mediation of environmental assessment’s influence: what role for power? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 39:5–12.

- Cashmore M, Bond A, Cobb D. 2008. The role and functioning of environmental assessment: theoretical reflections upon an empirical investigation of causation. J Environ Manage. 88(4):1233–1248.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:66–72.

- Charles CM. 1998. Introduction to educational research. 3rd ed. New York: Longman.

- CM Sintra (Câmara Municipal de Sintra). 2018. Plano Diretor Municipal: Relatório Ambiental da Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica. Available from: https://cm-sintra.pt/index.php?option=com_content&Itemid=938&catid=181&id=6288&view=article.

- Elling B. 2009. Rationality and effectiveness: does EIA/SEA treat them as synonyms? Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):121–131.

- Fidélis T, Rosa AR, Albergaria R. 2016. Developing na analytical framework to assess the consistency of contents and terminology used by SEA reports for similar types of plans. J Environ Assess Policy Man. 18(4):1650024.

- Fischer TB. 2002. Strategic environmental assessment performance criteria – the same requirements for every assessment? J Environ Policy Man. 4(1):83–99.

- Fischer TB, Gazzola P. 2006. SEA effectiveness criteria – equally valid in all countries? The case of Italy. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26(4):396–409.

- Fisher TB, Onyango V. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment-related research projects and journal articles: an overview of the past 20 years. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(4):253–263.

- Hanna K, Noble B. 2015. Using a Delphi study to identify effectiveness criteria for environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 33(2):116–125.

- IAIA. 2002. IAIA SEA performance criteria, special publication series number 1. [accessed 2018 Dec 17]. http://iaia.org/uploads/pdf/sp1.pdf.

- Monteiro MB. 2011. Percepções sobre a contribuição da AAE nos processos de planeamento. Lisboa: Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa.

- Partidário MR. 2007. Guia de Boas Práticas para Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica – orientações Metodológicas. Amadora: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente.

- Partidário MR. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment better practice guide – methodological guidance for strategic thinking SEA. Lisboa: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente e Redes Energéticas Nacionais.

- Partidário MR, Nunes D, Lima J. 2010. Definição de Critérios e Avaliação de relatórios Ambientais. Amadora: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente.

- Pope J, Bond A, Cameron C, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2018. Are current effectiveness criteria fit to purpose? Using a controversial strategic assessment as a test case. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 70:34–44.

- REA. 2018. Relatório do Estado do Ambiente Portugal 2018. Amadora: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente, https://rea.apambiente.pt/.

- REN (Redes Energéticas Nacionais). 2011. Plano de Desenvolvimento e Investimento da Rede Nacional de Transporte de Electricidade 2012–2017 (2022): Relatório Ambiental da Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica. Available from: http://www.centrodeinformacao.ren.pt/PT/publicacoes/PlanoInvestimentoRNT/PDIRT%202012-2017%20(2022)/AAE%20Rel%20Ambiental%20PDIRT%202012-2017%20(2022)%20Jul2011.pdf.

- Runhaar H, Driessen PPJ. 2007. What makes strategic environmental assessment successful environmental assessment? The role of context in the contribution of SEA to decision-making. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 25(1):2–14.

- Sheate WR, Richardson J, Aschemann R, Palerm J, Steen U 2001. SEA and integration of the environment into strategic decision-making (3 Volumes). Final Report to the European Commission, DG XI, Contract No. B4-3040/99/136634/MAR/B4, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Luxembourg. Available from: http://ec.europe.eu/environment/eia/sea-support.htm.

- Stoeglehner G. 2010. Enhancing SEA effectiveness: lessons learnt from Austrian experiences in spatial planning. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 28(3):217–231.

- Theophilou V, Bond A, Cashmore M. 2010. Application of the SEA directive to EU structural funds: perspectives on effectiveness. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:136144.

- Van Buuren A, Nooteboom S. 2009. Evaluating strategic environmental assessment in The Netherlands: content, process and procedure as indissoluble criteria for effectiveness. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):145–154.

- Van Doren D, Driessen PPJ, Runhaar HAC. 2013. Evaluating the substantive effectiveness of SEA: towards a better understanding. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 38:120–130.

- Wang H, Bai H, Liu J, Xu H. 2012. Measurement indicators and an evaluation approach for assessing strategic environmental assessment effectiveness. Ecol Indic. 23:413–420.

Annex I

SEA effectiveness in Portugal

With the objective to contribute to an international publication on the effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment (SEA), this questionnaire intends to collect information among relevant stakeholders of SEA in Portugal. The questionnaire aims to understand the effectiveness of SEA in Portugal, specifically the influence of SEA in development processes and the value of SEA to environmental authorities and other interested actors, and includes questions not usually approached in other published reports in Portugal.

This questionnaire is anonymous and it will take approximately 15 min. The results will be analysed in an integrated way, this way ensuring confidentiality of the answers. There are no right or wrong answers, so we ask you to answer in an spontaneous way to the questions, based on your practical experience.

For any clarification, you may contact us in

[email protected] or [email protected]

Your participation is very important to us! Thank you in advance for your cooperation.

Maria do Rosário Partidário

Margarida B. Monteiro

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

My participation in this questionnaire confirms that

1. I read and understand the objective of the questionnaire.

2. It has given me the opportunity and means to raise questions about the investigation in which this questionnaire applies to and about my participation.

3. I agree to voluntary participate in this investigation.

QUESTIONNAIRE

1. Professional activity:

□ Consultant

□ Administration (national, regional)

□ Administration (local)

□ Academia

□ NGO

□ Other: ___________________________________________________________

2. Field of expertise:

□ Design, planning, and architecture

□ Economics and management

□ Health sciences

□ Natural and environmental sciences

□ Social and political sciences

□ Engineering

□ Other: ___________________________________________________________

3. How familiar you are with the SEA instrument?

□ Only with the SEA objective

□ Only with the SEA process

□ There has been involvement in SEA

4. What is your experience with SEA?

□ None

□ 1–5 SEA

□ More than 6 SEA

5. For the following statements, how do you describe the political context and decision-making culture of Portugal that frame SEA (score from 1 – very low to 5 – very high):

6. What have you observed as an influence of SEA:

6.1. During the elaboration of the plan (choose a maximum of three options):

6.2. During the implementation of the plan (choose a maximum of three options):

7. What do you consider to be the most relevant strategic changes that a SEA makes to a plan? Indicate a maximum of three changes:

8. Regarding public participation, how useful is SEA in (score from 1 – not useful to 5 – very useful):

9. Regarding technical capacity for SEA, what is for you the current situation for (score from 1 – very low capacity to 5 – very high capacity):

10. Regarding institutional capacity for SEA, what is for you the current situation for (score from 1 – very low capacity to 5 – very high capacity):

11. If you know, how much it costs one SEA (approximately):

________________________________________________________________________

12. What is, in your opinion, the balance between costs and benefits from the application of SEA:

□ Costs ≫ benefits

□ Costs = benefits

□ Costs ≪ benefits

13. How effective is SEA in promoting and achieving (score from 1 – not effective to 5 – very effective):

14. In general, how effective are SEA in Portugal?

15. In your opinion, what is the most important criteria for an effective SEA?

________________________________________________________________________

16. In your opinion, what is the most common difficulty that may impede an effective SEA?

________________________________________________________________________

17. Can you suggest a case that you consider to have an effective SEA?

________________________________________________________________________

18. Any comments or suggestions?

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for your participation!

ANNEX II

QUESTIONNAIRE RESULTS

1. Professional activity:

2. Field of expertise:

3. How familiar you are with the SEA instrument?

4. What is your experience with SEA?

5. For the following statements, how do you describe the political context and decision-making culture of Portugal that frame the SEA (score from 1 – very low to 5 – very high):

6. What have you observed as an influence of SEA:

6.1. During the elaboration of the plan (choose a maximum of three options):

6.2. During the implementation of the plan (choose a maximum of three options):

7. What do you consider to be the most relevant strategic changes that an SEA makes to a plan? Indicate a maximum of three changes1:

8. Regarding public participation, how useful is SEA in (score from 1 – not useful to 5 – very useful):

9. Regarding technical capacity for SEA, what is for you the current situation for (score from 1 – very low capacity to 5 – very high capacity):

10. Regarding institutional capacity for SEA, what is for you the current situation for (score from 1 – very low capacity to 5 – very high capacity):

11. If you know, how much it costs one SEA (approximately):

12. What is, in your opinion, the balance between costs and benefits from the application of SEA:

13. How effective is SEA in promoting and achieving (score from 1 – not effective to 5 – very effective):

14. In general, how effective are SEA in Portugal?

15. In your opinion, what is the most important criteria for an effective SEA2?

16. In your opinion, what is the most common difficulty that may impede an effective SEA3?