ABSTRACT

Empirical research dedicated to Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is mostly grounded on SEA systems guided by legal requirements, clearly stated procedures and systematic use of SEA to policy- and plan-making. Nevertheless, a considerable parcel of SEA practice is currently occurring in countries with no specific legislation or guidance to be followed, i.e. non-regulated SEA systems. Therefore, it is important to understand how SEA is performing in these countries and to establish whether related SEA systems are subject to the same premises and perspectives of effectiveness that have been reported in literature so far. The paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the state-of-practice in Brazil, based on best practice analysis of SEA reports and interviews, reporting empirical evidence regarding the use of SEA and its related timing, procedural performance and key players involved. Main findings reveal an isolated instrument, embroidered in a disperse and unclear framework, poorly coordinated and highly sensitive to circumstances. Provision of a structured system, indicating clear purposes of SEA, systematic procedures and stakeholder’s responsibilities are suggested as potentially relevant measures to balance current system’s flexibility, thus fostering SEA effectiveness.

1. Introduction

Despite different approaches guiding the use of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) to support the formulation of policies, plans and programmes (Sadler Citation2011), it seems to be consensual that to be effective and secure an adequate level of integration of environmental aspects in policy and plan-making, the SEA process must: (i) focus on the development of reasonable alternatives (Fischer Citation2007; Therivel Citation2010; Sadler Citation2011); (ii) be driven by evidence (Fischer Citation2007); (iii) adopt a baseline- or objectives-led approach (Therivel Citation2010); and (iv) be flexible and adaptable to specific contexts (Partidário Citation2010). Also, given the potentially significant influence on the use of land, resources and ecosystems, ‘SEA can be applied to positive purpose as a means of promoting environmentally sound and sustainable development, shifting from a “do least harm” to a “do most good” approach’ (Sadler Citation2011, p. 2).

SEA is undertaken in an increasing number of countries and organisations (Sadler Citation2011), spread in more than 60 countries (Tetlow and Hanusch Citation2012), including a diverse range of countries in which it is guided by legal requirements, clearly stated procedures, guidance and a systematic use in policy and plan-making (e.g. member states of European Union, Canada, Australia, Chile, China), and also a diverse range of countries in which it is applied without the support of a clearly structured SEA system (e.g. Brazil, Mexico, Angola, New Zealand).

SEA practice in non-regulated contexts has been expanding (Loayza Citation2012) and is often required (and oriented) by development agencies (Sánchez and Croal Citation2012; Tshibangu and Montaño Citation2016). However, this context (absence of a regulated SEA system) can stimulate the proliferation of different forms of SEA as its meaning, purposes, proceedings, benefits, etc. can be interpreted differently, leading to low effective assessments (Margato and Sánchez Citation2014).

SEA research, though, has been particularly focused on regulated SEA systems and a systematic use of SEA (Fischer and Onyango Citation2012), lacking empirical studies about SEA characteristics and performance in other contexts. Aiming to address this particular gap, this paper is focused on the SEA practice in a non-regulated context, its benefits and constraints, and lessons that could be learnt. The paper is based on evidence produced by empirical investigation regarding SEA performance in Brazil, an emerging economy whose experience with SEA relies on an ‘unregulated and experimental basis’ (Mota et al. Citation2014, p. 3).

The paper provides a comprehensive analysis of SEA practice in the country regarding the profile of SEAs elaborated, considering the type of strategic actions and sectors they have been applied to; the different players involved (who?); the main motivations for the use of SEA (why?); the SEA procedures (how?); and the benefits and constraints derived from its use (with what effect?). To this respect, 31 SEA reports (out of 38 SEAs identified until 2016) were analysed using different methods, complemented by semi-structured interviews with key actors involved in five SEAs.

The paper consists of six sections. After this introduction, a review of international literature regarding the flexibility of SEA systems and the implications to non-regulated SEA systems is presented. This is followed by the description of the methods that have supported the research and the presentation of the outcomes considering an overview of SEA practice in Brazil, based on three aspects: SEA motivation and contextual aspects; best practice gap analysis; and stakeholder perceptions. Finally, the results are discussed, and the paper concludes synthesising its main findings and contributions.

2. SEA flexibility and implications to non-regulated SEA systems

To a large extent, SEA theory has developed based on principles of project-EIA (Fischer Citation2007; Sadler Citation2011). SEA was therefore conceived both as an instrument as well as a systematic process that should interact with decision making process preferably since its very early stages (Partidário Citation1996; Brown and Therivel Citation2000; Therivel Citation2010).

Bond et al. (Citation2015) argue that this approach tends to assume that the comprehension of reality and consequent cause-effect relations can be enough to convince decision makers to act accordingly. This approach though has been largely criticised, given that planning and decision rationalities are limited by different factors (Fischer Citation2003). Thus, it has been argued that the traditional SEA approach (‘EIA-based SEA’) is unable to adequately encompass the complexity of planning and decision-making processes, especially because it ignores some important contextual aspects such as power relations and values involved in planning process (Kørnøv and Thissen Citation2000; Nitz and Brown Citation2001; Runhaar and Driessen Citation2007), as well as uncertainties and lack of information (Cherp et al. Citation2007; Bond et al. Citation2015).

To overcome these limitations, other approaches have been proposed along the years (e.g. Partidário Citation2012), emphasising that SEA should be more flexible and adaptable to the context (Hilding-Rydevik and Bjarnadóttir Citation2007). Moreover, it has been argued that in addition to assess the environmental effects of strategic decision making, SEA should play a role in persuading planners to think strategic actions in a more environmental friendly way (Bina Citation2007; Partidário Citation2015). In this sense, SEA is said to be based on communicative rationality (Fischer Citation2003), using participative and collaborative methodologies to promote the discussion of values and obtain consensus (Kørnøv and Thissen Citation2000; Bina Citation2007).

Currently there is no universal SEA approach, but instead a ‘family of instruments’ that varies within a spectrum from less to more strategic SEA, delimited on one end by ‘impact assessment-based SEA’ and on the other end by ‘strategy-based SEA’ (Dalal-Clayton and Sadler Citation2005; Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017). The first reflects the project-EIA tradition and is mostly aligned to rational theory; the second is characterised as a ‘process for driving institutional change’ and is more sensitive to the institutional environment and factors that influence decision-making contexts (Wallington et al. Citation2007; Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017).

Despite of different SEA approaches and concepts, there is a common understanding regarding the main principles that should drive its practice. In this sense, what differentiates the SEA approaches is the extent to which each principle is applied (Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017). For instance, the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA, Citation2002) indicates that a good-quality SEA process should be: (i) integrated – ensuring the assessment of all strategic decisions relevant to sustainable development, addressing relevant biophysical, social and economic aspects and tiered to relevant policies and projects; (ii) sustainability-led; focused on key issues of sustainable development and customised to each decision making process; (iii) accountable; (iv) participative, informing and involving the stakeholders and (v) iterative, providing the information early enough to influence decision making process.

(Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017, p. 3) also highlight four ‘foundational principles’ that capture the basic features of SEA: (i) SEA must be strategically focused, meaning being focused on asking the right questions and on influencing PPPs; (ii) SEA must explore strategic options, assessing what is needed to achieve a desirable future and its implications; (iii) SEA is nested in a larger system of decision-making processes with multiple and mutually influential tiers, and must influence them (Fischer Citation2006; Arts et al. Citation2011); (iv) SEA must be sensitive to the policy and decision-making context in which it is applied, which will influence on its approach and design (Hilding-Rydevik and Bjarnadóttir Citation2007).

The need for SEA to be sensitive and adaptable to the context has been generally recognised and often mentioned as a necessity to increase SEA’s capacity to influence decision making and induce changes in PPP making and decision-making routines (Bina Citation2007; Hilding-Rydevik and Bjarnadóttir Citation2007; Sánchez and Croal Citation2012; Partidário Citation2015). However, there is still an ongoing debate on how flexible SEA systems and procedures should be.

On one hand, it has been argued that SEA should not rely only on standard procedures. Instead, it should be flexible enough to be adjusted to the flow and dynamics of decision-making to adequately involve key actors and enable dialogues towards mutual understanding (Partidário Citation2015), which could be achieved by adopting a constructive approach (Lobos and Partidário Citation2014). On another hand, methodological flexibility is said to lead to significant challenges to SEA practice, as it is usually guided by generic guidelines that often result in practitioners’ and decision-makers’ doubts and criticism regarding SEA effectiveness (White and Noble Citation2012).

Furthermore, there are some evidence showing that a flexible SEA procedure is barely effective when decision-making processes are subject to a high level of influence by political interests. In these cases, flexible SEA procedures tend to legitimise non-accountable and non-transparent decision-making processes (Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; Gazzola Citation2008).

Also, considering that SEA training and capabilities are limited and the consideration of environmental issues in PPP making is not yet fully endorsed, it has been argued that systematic procedural requirements play a fundamental role to the maturity of SEA systems (Walker et al. Citation2016). In this sense, well defined procedures seem to enable SEA to provide valuable information and public participation (Montis Citation2013; Slunge and Tran Citation2014).

2.1. Non-regulated SEA systems

Herein an SEA system is understood as composed by a set of elements according to Therivel (Citation1993), e.g. SEA purposes and objectives, procedures, level of decisions in which SEA will be applied, stakeholders’ responsibilities and level of integration to decisions.

Formal and clearly regulated SEA systems constitute the most common context in which SEA is applied and also is more frequently reported in literature (Fischer and Onyango Citation2012). In these cases, SEA is usually mandatory for certain types of PPPs and systematically applied. For example, this is the case of all European Union member states following the SEA Directive 2001/42/EC.

By its turn, non-regulated SEA systems add a different perspective to SEA theory and practice. The lack of legally established objectives, procedures, screening criteria etc. is a peculiar feature of SEA worldwide, as verified in Loayza (Citation2012), McGimpsey and Morgan (Citation2013), Montaño et al. (Citation2014), Sánchez-Triana and Enriquez (Citation2007), Tshibangu and Montaño (Citation2016) and Victor and Agamuthu (Citation2014).

Although there is no consensus related to whether a mandatory SEA would perform better than non-mandatory (Ashe and Marsden Citation2011; Kelly et al. Citation2012; Morrison-Saunders and Pope Citation2013; João and McLauchlan Citation2014), a growing body of literature suggests that clear guidance, objectives and purpose contribute to enhance the performance of SEA systems in non-regulated contexts (Madrid et al. Citation2011; Montaño et al. Citation2014; Olagunju and Gunn Citation2014; Victor and Agamuthu Citation2014).

Moreover, favourable arguments to a regulated context include: the comprehension of formal regulations as a warrant to the ‘creation of room’ in plan-making to apply the instrument and therefore to pursue best practices based on explicit guidance and cumulated experience (Wirutskulshai et al. Citation2011; Montaño et al. Citation2014); the adaptation of SEA principles to context-specific needs and policy-making procedures (Madrid et al. Citation2011); the allocation of resources for SEA practice and performance evaluation (Wirutskulshai et al. Citation2011); the assurance that both SEA and plan outcomes will be implemented and monitored (Retief Citation2008); the need of a solid statutory framework to coordinate the SEA system and prevent that relevant issues are not properly taken into account (Kelly et al. Citation2012).

From a different perspective, it has been suggested that SEA implementation should not start with mandatory requirements, but should be gradually internalised by the country and the community of practitioners, allowing institutional capacity building and learning, stronger ownership of SEA and avoiding red tape (World Bank et al., Citation2011; Slunge and Loayza Citation2012; Mota et al. Citation2014). Nevertheless, the inherent limitation of legislation/regulation to influence other relevant aspects to SEA effectiveness such as stakeholders’ commitment, power structure and culture (Hansen et al. Citation2013; Martin and Morrison-Saunders Citation2015) and positive experiences reported in informal contexts (Kelly et al. Citation2012; Martin and Morrison-Saunders Citation2015) stimulate the debate regarding how much flexibility is enough in SEA systems, which is a relevant topic both to regulated and non-regulated contexts to discuss SEA design, implementation and revision.

3. Methodological procedures

This paper is focused on the implications of a non-regulated and flexible context to the effectiveness of a SEA system. In order to obtain more information about SEA applications in non-regulated contexts, the reader is referred to the works of González et al. (Citation2014), Jackson and Dixon (Citation2006), McGimpsey and Morgan (Citation2013), Montañez-Cartaxo (Citation2014), Montaño et al. (Citation2014), Oberling et al. (Citation2013), Retief (Citation2007, Citation2008), and Tshibangu and Montaño (Citation2016).

To provide a comprehensive analysis of the SEA practice in a non-regulated context, the case of Brazil was investigated considering three main aspects:

(i) the profile of SEA system based on the SEAs elaborated from 1994 to 2016;

(ii) procedural performance of SEAs elaborated from 1994 to 2016;

(iii) perceived benefits and constraints of SEA.

3.1. Profile of SEA system in Brazil

This stage has considered SEA reports finished until December, 2016, identified in literature and by direct research in databases of federal and state departments/ministries and agencies, multilateral development agencies (World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank) and consultancy firms.

31 SEA reports (out of 38 identified at that moment, or 82% of total) were fully accessed, thus allowing to classify the following aspects, pointed by Therivel (Citation1993) and Von Seht (Citation1999) as relevant issues of a SEA system:

the type of strategic action (plans, programmes and ‘structural projects’) and the sector of application;

the key players involved (who has required the SEA? who was the proponent of the strategic action? who has prepared the SEA report?); and

the main motivations/purposes for SEA elaboration.

3.2. SEA procedural performance

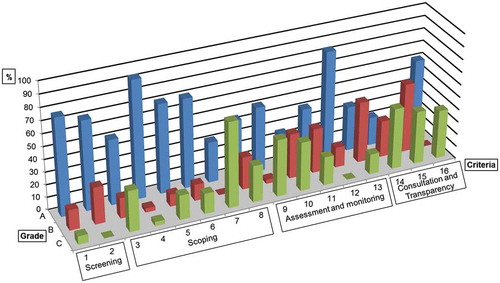

Based on previous quality review packages, a selected excerpt of the professional literature and SEA guidelines and international principles, 16 best practice criteria were defined and organised in a generic SEA procedural framework (). SEA reports were then submitted to content analysis following Krippendorff (Citation2003) that allowed the categorisation of the information according to the correspondence to each criterion. The compliance with best practice criteria was verified and graded applying a 3-level scoring system, similar to what was applied in previous work (Fischer Citation2010; Lemos et al. Citation2012; McGimpsey and Morgan Citation2013). To minimise bias, the score system was simplified to three clearly distinct levels (‘satisfactory’, ‘somewhat satisfactory’ and ‘not met’). The first six reports were reviewed twice, which helped to calibrate the reviewer’s perception.

Table 1. Procedural performance assessment: criteria and grades.

The grades’ frequency was calculated and plotted to each criterion (similar to Fischer Citation2010), thus allowing to be interpreted in terms of compliance to best-practice criteria. Considering some particularities of the SEA System in Brazil, two groups were analysed separately: (i) SEA reports prepared according to the same requirements; and (ii) SEA reports prepared according to the same guidance and methodological orientation. Both groups (Control Group #1 and #2) were then compared by contrast.

3.3. Perceived benefits and constraints related to SEA

The benefits of SEA vary from visible and sometimes measurable effects on decision making to less tangible effects and outcomes (Tetlow and Hanusch Citation2012). Also, factors such as timing and the integration to the planning processes are understood as constraints to the SEA process and, consequently, constraints to its potential benefits (Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Stoeglehner et al. Citation2009; Van Buuren and Nooteboom Citation2009; Gachechiladze-Bozhesku and Fischer Citation2012; Van Doren et al. Citation2013). Considering that, in order to provide a more comprehensive understanding of SEA system of Brazil, perceived benefits and constraints were analysed.

The identification of benefits from and constraints to SEA was supported by semi-structured interviews conducted with key actors, asked to comment about their experience in SEA processes, considering the following topics:

when SEA was initiated (timing);

the expected benefits from SEA elaboration;

the level of integration between SEA and planning teams;

SEA benefits and contributions for the planning process and decision making (e.g. provision of information, influence in final decision, transparency);

the extent to which planning process and decision making would be different without SEA.

The content of the interviews was analysed, exploring explicit content and implicit meanings (Franco Citation2007). Data gathered were thematically organised and interpreted following the approach adopted by Matthews and Ross (Citation2010) considering two broad themes – ‘perceived benefits’ and ‘perceived constraints’ – and categories and subcategories defined based on the interviews’ content.

Interviewees were selected opportunistically, trying to balance the profile of key actors involved in SEA preparation: proponents of strategic actions, institutions that requested SEA and consulting firms. In total, six actors were interviewed: a representative of a state department that was the proponent of a strategic action; representatives of two environmental agencies that required SEAs and a representative of the Public Prosecution’s Office that supported the requirement; and representatives of two consultancy firms (which were responsible for 30% of the SEA reports considered in this paper).

The interviewees have been involved in five different SEA processes, considered to be a fair sample compared to the 31 SEAs analysed. These have included four SEAs required by state government and one motivated by private investors. It is relevant, though, to clarify that the sample size was not intended to be representative. Rather, it supports an exploratory approach to identify benefits and constraints of SEA in this particular context.

4. Results

4.1. Profile of SEAs: contextual aspects and motivations

Regarding to the type of strategic action SEA was applied to, most of SEAs analysed in this paper were applied to programmes and structural projects, which denotes the prevalence of lower strategic levels (). Some controversial SEAs have been largely criticised due to their proximity to ‘large EIAs’ limited to the assessment of projects (Sánchez and Silva-Sánchez Citation2008; Silva et al. Citation2014). In this context, it was considered relevant to use the term ‘structural projects’ to describe the strategic action assessed in seven SEAs, referring to large infrastructure projects with potential to change the development of a region (MMA, Citation2002).

Regarding the sector in which they were applied, applications to energy and transport correspond to 68% of the universe of SEAs in the country ().

Interestingly, a characteristic of the Brazilian system (and perhaps a characteristic of non-regulated SEA systems in general) is that the proponent of the strategic action () is usually not the same agent that requires the preparation of the SEA ().

In fact, only five SEAs (13%) occurred following an initiative of the proponent of the strategic action. The others were motivated by different stakeholders, such as and federal/state government. Federal and state governments have demanded 14 SEAs (usually through environmental agencies), followed by Multilateral Developing Agencies (MDAs) with 9 SEAs. Government and MDAs acted jointly as the motivator of SEA in other four cases. Private initiative has motivated the occurrence of two SEAs.

Another characteristic of the SEA system in Brazil is that virtually all SEAs were prepared by consultancy firms (28 cases out of 31 analysed). In-house preparation has only happened in three situations (one of them with the support of a consultancy firm).

Regarding the motivations for the use of SEA, four main arguments were identified: (i) to support (facilitate) the environmental licensing of projects, anticipating relevant issues; (ii) to fill in the gaps of project-EIA, e.g. evaluating a group of projects instead of individual ones, considering a broader spatial and time scale and, also, cumulative impacts; (iii) to support the elaboration of development strategies to a region or a sector; (iv) to meet the safeguard policies of MDAs and to support a loan agreement.

These motivations match the perceived potential benefits of SEA elaboration in Brazil as identified by Margato and Sánchez (Citation2014) based in literature review, and reaffirm the revealed prevalence of using SEA with a closer proximity to the project level.

Synthetically, three main characteristics of SEA practice in Brazil can be observed:

the prevalence of project-type SEAs (the assessments are by at large applied to ‘structural projects’ and programmes);

the adoption of a reactive approach, once a frequent motivation for SEA was to overcome shortcomings identified during project EIA;

the influence of multilateral development agencies, in a considerable number of SEAs.

4.2. SEA procedural performance

The outcomes presented in reveal some aspects of Brazilian SEA system that may be related to the high level of flexibility of non-regulated contexts.

In particular, it is noted a reasonable proximity to best practice in different aspects of the SEA process, with 70% or more of SEA reports demonstrating the compliance to best practice criteria. In this case, it was verified a clear description of why SEA was needed (criterion 1) and a clear description of the state of the environment (criterion 4). Also, mitigation measures were satisfactorily presented (criterion 12) in 80% of cases. Moreover, the description of the purpose of the strategic action (criterion 2), the identification of key environmental issues (criterion 5) and a clear description of SEA purposes (criterion 6) were done well in 68% of cases.

On the other hand, the shortcomings are related to the establishment of sustainable objectives (criterion 7) and to the definition and use of indicators (criterion 8), thus revealing a relevant gap in the practice of SEA in Brazil that needs to be addressed. Besides, strategic alternatives (criterion 10) were satisfactorily developed only in 8 cases (out of 31) and public consultation and participation (criterion 15) showed to be practically non-existent during the preparation of the SEA report.

Curiously, despite the good performance in presenting mitigation measures (as previously mentioned), this is not accompanied by the subsequent definition of a monitoring strategy or follow-up scheme (criterion 13).

These aspects are quite similar to the performance of Brazilian EIAs applied to projects, in which the description of the environment and the development of mitigation measures are usually well done, but other aspects such as the evaluation of alternatives and public participation are comprehended as one of the most relevant project-EIA weaknesses (Glasson and Salvador Citation2000; Kirchhoff et al. Citation2007; Lima and Magrini Citation2010).

Some of the gaps found in Brazil are similar to what was previously reported for other SEA systems, which also include monitoring (Fischer Citation2010; Montis Citation2013), public participation (Partidário Citation2010; Montis Citation2013) and development of alternatives (Fischer Citation2010; Montis Citation2013; González et al. Citation2015). It suggests these aspects are still a challenge to SEA worldwide and may not constitute a singularity of non-regulated SEA systems.

A relevant aspect of the outcomes is related to the discrepancies of performance when taking each criterion individually. In other words, the number of reports that had met each criterion is highly variable – thus showing the practice in Brazil gives no sign of a standard quality, nor a basic level of quality.

Given the outcomes reported by Fischer et al. (Citation2011), Ireland EPA (Citation2012) and Partidário (Citation2010), respectively to SEA reports prepared in England, Ireland and Portugal, arguably a certain standard level of quality may be related to a systematic (and usually mandatory) use of SEA and related guidance. Therefore, substantial differences of approaches and procedures to conduct the assessments, as well as in the quality of reports, may be expected in non-regulated contexts, similar to what was already reported in the present paper.

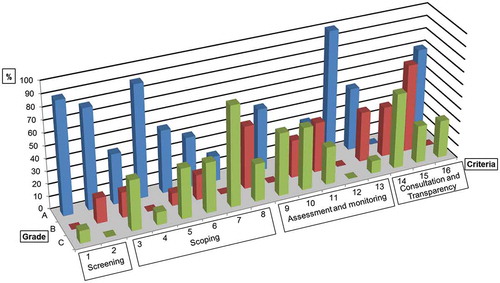

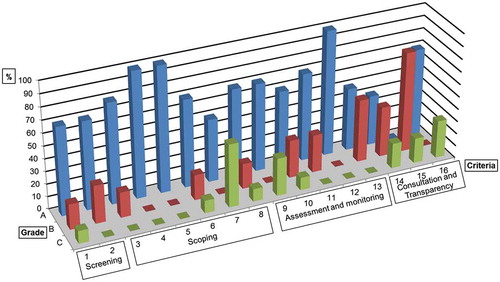

There is consensus in literature about the influence of contextual factors in SEA performance (Fischer and Gazzola Citation2006; Fischer Citation2007; Bina Citation2008; Jha-Thakur et al. Citation2009; Montis Citation2013). In fact, based on the analysis of SEA reports, two groups of SEAs have stood out and been analysed separately. The first group is constituted by 10 SEAs prepared according to the requirements of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and, therefore, needed to follow the bank’s specific guidelines. The second group includes 10 SEAs prepared by two different consultancy firms which have been trained and are quite experienced in both a particular approach and methodological guidance (Oberling et al. Citation2013; Silva et al. Citation2014).

and present the score frequency calculated for each criterion, respectively to the aforementioned groups. It is relevant to mention that only one case was repeated in both groups, which secures their mutual independency.

Figure 6. Procedural performance evaluation: scores frequency in Group #1 (SEAs prepared according to IDB’s requirements).

Figure 7. Procedural performance evaluation: scores frequency in Group #2 (same approach and methodological guidance).

There are clear differences in the outcomes from Groups #1 and #2. SEA reports prepared to respond to the safeguard policies of a financial institution (Group #1), and therefore prepared according to the bank’s guidelines, have repeated the same performance profile as obtained to the whole set of SEA reports, performing poorly to the criteria related to scoping, assessment and consultation. Conversely, SEA reports that were prepared by experienced consultancy firms following the same approach and guidance (Group #2) have performed well to those criteria, with a substantial decrease in the ‘C’ grade (i.e. issues that were not addressed at all). This may be partially reflecting contextual aspects related to the expertise of the actors involved in these SEAs, but also the positive aspects of the voluntary adoption of an international guideline – thus somehow filling the gap of a procedural guideline in the Brazilian context – similar to what was reported by Loayza (Citation2012), OECD (Citation2012), and Tetlow and Hanusch (Citation2012) referring to other ‘non-regulated’ SEA contexts.

Nevertheless, a common feature of both groups is the poor performance to ‘consultation and transparency’ criteria, mainly in terms of describing how other authorities and the public were engaged to the SEA process.

4.3. Perceived benefits and constraints

Interview results () indicate that perceived constraints mentioned by SEA practitioners are related to the planning context and the current SEA system, which seems to be hindering better-quality assessments. At the same time, perceived benefits are mainly related to the promotion of changes in planning routines. Interviews excerpts are presented in to illustrate the benefits and constraints identified.

Table 2. SEA benefits and constraints perceived by key-players.

Table 3. Interviews excerpts organized by themes, categories and subcategories.

According to the interviewees, SEA is credited to promote opportunities to enhance the communication between different sectors and stakeholders that otherwise would barely work together, to unify some concepts and purposes, gathering and sharing information, which are desirable characteristics of an instrument that is to be used as a platform to future decisions.

Nevertheless, despite these opportunities, there is no guarantee that the information and recommendations delivered would actually be adopted, as there is no mechanism in place to make it mandatory, nor any definition of responsibilities and accountability mechanisms like monitoring and follow-up.

In this context, the adoption of SEA’s recommendations ‘highly depends on the circumstances, especially on the people involved in plan – and decision-making processes, and the extent to which they embrace the instrument’ (Secretary of Environment). However, it may be difficult to embrace SEA in a non-mandatory context because of the lack of familiarity to SEA practice (even within environmental agencies and consultancy firms), and also because of the ‘transience of public administration, especially of decision makers’ (Secretary of Environment). Thus, even when the gap of knowledge is fulfilled (usually through practice), this knowledge is often put aside after a short period of time.

As mentioned by five interviewees, even the use of SEA itself is strongly dependent on the circumstances, as they were often an initiative of an individual (e.g. from a government agency or department) with previous knowledge about the instrument, who was already convinced that it could be helpful in that particular situation. According to a representative of a consultancy firm, ‘the merit is for these people, who had the vision to instigate a good discussion’. In this context, SEA needs to be known by a key stakeholder – empowered enough to influence the planning process – to find some room for SEA to be applied.

Concerning the moment in which the SEA started, four (out of five) SEAs mentioned by the interviewees initiated after a major decision was taken (related to the implementation of a structural project). These SEAs were referred by two interviewees as ‘SEAs of already-made decisions’, which were limited to deal with subsequent/complementary decisions, such as the definition of impact mitigation measures and recommendations regarding other public policies to ease the integration of new developments to the affected territory. As a consequence, alternatives have focused on the effects of strategic actions and not on the strategic action itself.

Interestingly, as could be seen in , the perceived SEA benefits are not directly related to the influence on the strategic action, thus explaining the low level of substantive effectiveness, but rather to the promotion of improved communication between sector and stakeholders and to the creation of different opportunities, which indicate the SEA capability to help overcoming some of the constraints related to planning context.

summarizes and exemplifies the perceived benefits and constraints identified.

5. Discussion

Although the number of SEAs prepared in Brazil (38 until 2016) can be assumed as irrelevant compared to other contexts where SEA is systematically applied (e.g. the 287 SEAs prepared in eight years in Ireland (Ireland EPA, Citation2012)), it is quite representative of a non-regulated context (e.g. Montaño et al. (Citation2014) have mentioned a total of 6 SEAs prepared in Angola, 13 in Mozambique, 13 in Mexico and 50 in South Africa to a similar period). Thus, the analysis of the practice in Brazil is relevant to understand the purposes and mechanisms involving the use of SEA in other non-regulated contexts.

Considering the evidence produced in this paper, we suggest that the practice of SEA in Brazil is influenced by a number of contextual components that includes: (i) the motives to be applied; (ii) the stakeholders involved; and (iii) the quality of reports, which reflects on SEA performance and effectiveness.

Broadly speaking, SEA was usually required to support project-level decision-making, as a reactive assessment which has started after main decisions were taken. This can explain, to a large extent, why the benefits reported by interviewees were basically related to the process rather than to the strategic action, as previously mentioned, thus corroborating what was reported by Montaño et al. (Citation2013) and Margato and Sánchez (Citation2014) regarding the substantial constraint of the strategic dimensions of SEA, as there is little (if any) room to influence on main decisions. Added to the low quality of SEA reports, this may be resulting in just ‘another loop in the usually long and time consuming road to project approval’ as Sánchez and Silva-Sánchez (Citation2008, pg. 522) have already referred to a particular SEA in Brazil.

The strategic dimension was also found a weakness in SEAs required by the Inter-American Bank, in which the main purpose reported was to comply with the bank’s requirements, thus reinforcing the relevance of the role that MDAs can play in non-regulated contexts (Loayza Citation2012; Tshibangu and Montaño Citation2016).

State and federal government (especially through environmental agencies) have requested a number of SEAs in Brazil, in a clear illustration of the bottom-up approach (from project-EIA to SEA). In these cases, both the necessity and opportunity to evaluate environmental impacts in a broader scale were identified during the design of projects and SEA was understood as the adequate instrument to be applied at that moment. None of the cases included SEA as part of a policy or even as an institutional routine – instead, the decision to use SEA in a particular situation was dependent of specific circumstances, institutional culture, political interests and even of the individuals involved in planning and decision-making processes. In this sense, each assessment represents an isolated process, which has also been reported as a characteristic of SEA in other non-regulated contexts as Mexico (Montañez-Cartaxo Citation2014) and Asian and African countries (Slunge and Loayza Citation2012).

Despite the lack of evidence related to the promotion of learning through the practice of SEA as described by Kidd et al. (Citation2011), the findings reveal interesting features in the Brazilian context, such as the cumulated experience of consultancies that were involved in SEA processes and, therefore, were able to consolidate the procedures and methods applied (as described, for example, by Silva et al. Citation2014).

On the other hand, constraints regarding learning through practice might be hindering SEA effectiveness, which reinforces the ‘unconsolidated’ aspect of the SEA system in Brazil, suggested by Montaño et al. (Citation2014, p. 13) as being strongly influenced by ‘non-mandatory SEAs, where objectives and procedures were unclear and where practice and resulting learning is limited and rather disperse’.

Thus, based on Brazilian practice, it is possible to argue that in the absence of a consolidated SEA system the use of SEA is generally attached to contextual factors and does not foster enough capacity building. Bond et al. (Citation2013) reported the difficult of impact assessment in general to promote ‘learning by doing’, which is related to the inability to promote critical reflections of previous practice. In this sense, the aforementioned authors reinforce the importance of follow-up to improve the learning process.

In summary, SEA practice in Brazil is defined by its low strategic dimension, supported by an unconsolidated system and isolated from the planning system, which tends to be perpetuated by the low capacity of learning. In this sense, improved practice seems to be constrained both by the planning context (e.g. characteristics of public administration, pressure to assess individual projects) and by the characteristics of the ‘SEA system’ that is being forged by practice. However, even with these constraints, some SEA benefits were perceived in practice, demonstrating the potential of SEA to stimulate improvements in the planning context, especially in terms of a better information flow and by supporting communication between stakeholders and institutions.

An alternative to deal with some constraints and the ‘unconsolidated’ aspect of the SEA system would be the establishment of a clear definition to the objectives, responsibilities and procedures for SEA through regulations and guidelines (Malvestio and Montaño Citation2013; Montaño et al. Citation2014; Mota et al. Citation2014), even though there are divergent opinions related to the effectiveness of establishing formal regulations for SEA and what would be the benefits related to informal practices (e.g. Kelly et al. Citation2012; Martin and Morrison-Saunders Citation2015).

Clearly, the situation in non-regulated contexts is significantly different and, based on the reported experience in Brazil, not enough to promote a consistent SEA system compared to regulated contexts. Anyway, even considering the fact that formal procedures are not enough to change mindsets and guarantee that SEA will lead to environmentally better decisions (Fischer Citation2006; Bond et al. Citation2013), the clear definition of methodological approaches and procedures are deemed as important aspects to support SEA to deal with the most relevant questions for the assessments (Bond et al. Citation2013) and to be consistent enough to stimulate the consideration of the main recommendations (Kelly et al. Citation2012).

6. Conclusions

In pursuing empirical evidence and a detailed account of SEA practice in a non-regulated context, this paper investigated the SEA practice in Brazil, identifying its main characteristics, as well as perceived benefits and constraints.

The results reinforce and advance previous knowledge about SEA in non-mandatory contexts, indicating that: (i) SEA practice has a weak strategic dimension; (ii) despite the absence of regulation, most SEAs were required by the government (usually through the environmental agency) or by a MDA, and the criteria to define whether SEA would be necessary depends on the circumstances; (iii) SEA is being used as an isolated instrument and dispersed among several institutions; (iv) SEA is highly influenced by specific circumstances and stakeholders involved in SEA processes; (v) the development of the SEA system is limited by a context of low learning capacity through practice and (vi) even with all the constraints, benefits related to communication, information and creation of opportunities were perceived.

Given the empirical evidence reported, it is to conclude that the combination of contextual aspects and a non-regulated SEA system in Brazil is hindering a more consistent application of the instrument and delaying both the organisation and the improvement of the system as a whole. As a result, screening and scoping are based on unclear criteria, with no standard procedures or guidance to SEA application and the capacity of learning through practice is low. In this sense, the practice of SEA is not promoting a significant contribution to the organisation and improvement of the Brazilian SEA system.

Based on our findings, we advocate the regulation of SEA as an alternative to fulfil some of the gaps reported, firstly promoting a common ground to the instrument, which most certainly reflects on the characteristics and the performance of SEA within the country. Nonetheless, further research of SEA practice in other non-regulated contexts is needed to better clarify the links to the unconsolidated and vulnerable aspects of the SEA system reported in this paper.

There is a range of possibilities related to the adaptation of SEA approaches to the Brazilian context, which still needs further investigation. However, this will inevitably include the development of a framework to guide and support the use of SEA in the country which considers the gaps reported in this paper regarding: (i) a clear definition of SEA objectives and its integration to the planning process; (ii) incentives to elaborate SEA in more strategic levels and with adequate timing and (iii) the definition of procedures, including the provision of adequate information and communication.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge FAPESP (Sao Paulo State’s Research Support Foundation) for the financial support provided (Processes n. 2017/00095-2 and 2011/05242-7).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arts J, Tomlinson P, Voogd H. 2011. Planning in tiers? Tiering as a way of linking SEA and EIA. In: Sadler B et al., editors. Handbook of strategic environmental assessment. London: Earthscan; p. 415–433.

- Ashe J, Marsden S. 2011. SEA in Australia. In: Sadler B et al., editors. Handbook of strategic environmental assessment. London: Earthscan; p. 21–35.

- Bina O. 2007. A critical review of the dominant lines of argumentation on the need for strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(7):585–606.

- Bina O. 2008. Context and systems: thinking more broadly about effectiveness in strategic environmental assessment in China. Environ Manage. 42:717–733.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Gunn JAE, Pope J, Retief F. 2015. Managing uncertainty, ambiguity and ignorance in impact assessment by embedding evolutionary resilience, participatory modelling and adaptive management. J Environ Manage. 151:97–104.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Stoeglehner G. 2013. Designing an effective sustainability assessment process. In: Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R, editors. Sustainability assessment: pluralism, practice and progress. Oxford: Routledge. p. 231–244.

- Brown AL, Therivel R. 2000. Principles to guide the development of strategic environmental assessment methodology. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 18(3):183–189.

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 22:295–310.

- [CEC] Commission of the European Communities. 2001. Directive 2001/42/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 27 June 2001 on the assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment. Off J Eur Commun L. 197:0030–37.

- Cherp A, Watt A, Vinichenko V. 2007. SEA and strategy formation theories: from three Ps to five Ps. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(7):624–644.

- Dalal-Clayton B, Sadler B. 2005. Strategic environmental assessment: a sourcebook and reference guide to international experience. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB. 2003. Strategic environmental assessment in post-modern times. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(2):155–170.

- Fischer TB. 2006. Strategic environmental assessment and transport planning: towards a generic framework for evaluating practice and developing guidance. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 24(3):183–197.

- Fischer TB. 2007. Theory and practice of strategic environmental assessment: towards a more systematic approach. London: Earthscan.

- Fischer TB. 2010. Reviewing the quality of strategic environmental assessment reports for English spatial plan core strategies. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:62–69. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.04.002.

- Fischer TB, Gazzola P. 2006. SEA effectiveness criteria – equally valid in all countries? The case of Italy. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:396–409.

- Fischer TB, Onyango V. 2012. SEA related research projects and journal articles: an overview of the past 20 years. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(4):253–263.

- Fischer TB, Potter K, Donaldson S, Scott T. 2011. Municipal waste management strategies, strategic environmental assessments and the consideration of climate change in England. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 13(4):541–565.

- Franco MLPB. 2007. Análise de conteúdo [Content Analysis]. Brasília: Liber.

- Gachechiladze-Bozhesku M, Fischer TB. 2012. Benefits of and barriers to SEA follow-up — theory and practice. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 34:22–30.

- Gazzola P. 2008. What appears to make SEA effective in different planning systems. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 10(1):1–24.

- Glasson J, Salvador NNB. 2000. EIA in Brazil: a procedures-practice gap. A comparative study with reference to the European Union, and especially the UK. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 20:191–225.

- González A, Therivel R, Fry J, Foley W. 2015. Advancing practice relating to SEA alternatives. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 53:52–63. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2015.04.003.

- González JCT, De La Torre MCA, Milán PM. 2014. Present status of the implementation of strategic environmental assessment in Mexico. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16:1450021.

- Hansen AM, Kørnøv L, Cashmore M, Richardson T. 2013. The significance of structural power in strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 39:37–45.

- Hilding-Rydevik T, Bjarnadóttir H. 2007. Context awareness and sensitivity in SEA implementation. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27:666–684.

- [IAIA] International Association for Impact Assessment. 2002. Strategic environmental assessment performance criteria. Spec Publ Ser. (1). [accessed 2018 Jun 04]. http://www.iaia.org/publicdocuments/special-publications/sp1.pdf.

- Ireland EPA (Ireland Environmental Protection Agency). 2012. Review of effectiveness of SEA in Ireland: key findings and recommendations. accessed 2018 Jan 16. http://www.epa.ie/pubs/advice/ea/reviewofeffectivenessofseainireland-mainreport.html.

- Jackson T, Dixon J. 2006. Applying strategic environmental assessment to land-use and resource-management plans in Scotland and New Zealand: a comparison. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 24:89–101.

- Jha-Thakur U, Gazzola P, Peel D, Fischer TB, Kidd S. 2009. Effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment - the significance of learning. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):133–144.

- João E, McLauchlan A. 2014. Would you do SEA if you didn’t have to? – reflections on acceptance or rejection of the SEA process. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 32(2):87–97. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.889265.

- Kelly AH, Jackson T, Williams P. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment: lessons for New South Wales, Australia, from Scottish practice. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30:75–84.

- Kidd S, Fischer T, Jha-Thakur U. 2011. Developing the learning potential of strategic environmental assessment in spatial planning. In: Rogerson R, Sadler S, Green A, Wong C, editors. Sustainable communities: skills and learning for place making. University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 53–68.

- Kirchhoff D, Montaño M, Ranieri VEL, Oliveira ISD, Doberstein B, Souza MP. 2007. Limitations and drawbacks of using Preliminary Environmental Reports (PERs) as an input to environmental licensing in São Paulo state: a case study on natural gas pipeline routing. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27:301–318.

- Kørnøv L, Thissen WAH. 2000. Rationality in decision- and policy-making: implications for strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 18(3):191–200.

- Krippendorff K. 2003. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. London: Sage.

- Lemos CC, Fischer TB, Souza MP. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment in tourism planning—extent of application and quality of documentation. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 35:1–10.

- Lima LH, Magrini A. 2010. The Brazilian audit tribunal’s role in improving the federal environmental licensing process. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30(2):108–115. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.08.005.

- Loayza F. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment in the World Bank: learning from recent experience and challenges. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Lobos V, Partidário MR. 2014. Theory versus practice in Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Environ Impact Assess Rev. 48:34–46.

- Madrid CK, Hickey GM, Bouchard MA. 2011. Strategic environmental assessment effectiveness and the initiative for the integration of regional infrastructure in South America (IIRSA): a multiple case review. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 13(4):515–540. doi:10.1142/S1464333211003997.

- Malvestio AC, Montaño M. 2013. Effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment applied to renewable energy in Brazil. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 15(2):1340007. doi:10.1142/S1464333213400073.

- Margato V, Sánchez LE. 2014. Quality and outcomes: a critical review of strategic environmental assessment in Brazil. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16(2):1–32. doi:10.1142/S1464333214500112.

- Martin L, Morrison-Saunders A. 2015. Determining the value and influence of informal strategic advice for environmental impact assessment: Western Australian perspectives. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 33:265–277.

- Matthews B, Ross L. 2010. Research methods: a practical guide for the social sciences. Edinburgh: Pearson.

- McGimpsey P, Morgan R. 2013. The application of strategic environmental assessment in a non-mandatory context: regional transport planning in New Zealand. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:56–64.

- [MMA] Ministério do Meio Ambiente [Ministry of Environment]. 2002. Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica [Strategic Environmental Assessment]. Brasília: MMA/SQA.

- Montañez-Cartaxo LE. 2014. Strategic environmental assessment in the Mexican electricity sector. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16(02):1450012. doi:10.1142/S1464333214500124.

- Montaño M, Malvestio AC, de Oppermann PA. 2013. Institutional learning by SEA practice in Brazil. UVP - Report. 27(4+5):201–206.

- Montaño M, Oppermann P, Malvestio AC, Souza MP. 2014. Current state of the SEA system in Brazil: a comparative study. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16(02):1450022. doi:10.1142/S1464333214500227.

- Montis A. 2013. Implementing strategic environmental assessment of spatial planning tools: a study on the Italian provinces. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 41:53–63. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.02.004.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Pope J. 2013. Learning by doing: sustainability assessment in Western Australia. In: Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R, editors. Sustainability assessment: pluralism, practice and progress. Oxford: Routledge. p. 149–166.

- Mota AC, La Rovere EL, Fonseca A. 2014. Industry-driven and civil society-driven strategic environmental assessments in the iron mining and smelting complex of Corumbá, Brazil. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16(2):1450010. doi:10.1142/S1464333214500100.

- Nitz T, Brown AL. 2001. SEA must learn how policy making works. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 3(3):329–342.

- Noble BF, Nwanekezie K. 2017. Conceptualizing strategic environmental assessment: principles, approaches and research directions. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 62:165–173.

- Oberling DF, La Rovere EL, Silva HVO. 2013. SEA making inroads in land-use planning in Brazil: the case of the extreme South of Bahia with forestry and biofuels. Land Use Policy. 35:341–358. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.06.012.

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2012. Strategic environmental assessment in development practice: a review of recent experience. OECD Publishing. [10 March 2013]. doi:10.1787/9789264166745-en.

- Olagunju A, Gunn JAE. 2014. First steps toward best practice SEA in a developing nation: lessons from the central Namib uranium rush SEA. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 1–12. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.941233.

- Partidário MR. 1996. Strategic environmental assessment: key issues emerging from recent practice. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 16:31–55.

- Partidário MR. 2010. Definição de Critérios e Avaliação de Relatórios Ambientais [Criteria definition and environmental reports assessment]. Lisbon: Portuguese Environmental Agency.

- Partidário MR. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment better practice guide - methodological guidance for strategic thinking in SEA. Lisbon: Portuguese Environment Agency and Redes Energéticas Nacionais (REN), SA.

- Partidário MR. 2015. Strategic advocacy role in SEA for sustainability. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 17(1):1550015–1550018.

- Polido A, Ramos TB. 2015. Towards effective scoping in strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. (June):1–13. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.993155.

- Retief F. 2006. The quality and effectiveness of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) as a decision-aiding tool for national park expansion — the greater Addo Elephant National Park case study. Koedoe. 49:103–122.

- Retief F. 2007. A performance evaluation of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) processes within the South African context. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(1):84–100. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2006.08.002.

- Retief F. 2008. The emperor’s new clothes — reflections on Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) practice in South Africa. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28:504–514.

- Runhaar H, Driessen PPJ. 2007. What makes strategic environmental assessment successful environmental assessment? The role of context in the contribution of SEA to decision-making. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 25:2–14.

- Sadler B. 2011. Taking stock of SEA. In: Sadler B et al., editors. Handbook of strategic environmental assessment. New York (NY): Earthscan; p. 621.

- Sánchez L, Croal P. 2012. Environmental impact assessment, from Rio-92 to Rio+ 20 and beyond. Ambiente e Sociedade. 15:41–54.

- Sánchez LE, Silva-Sánchez SS. 2008. Tiering strategic environmental assessment and project environmental impact assessment in highway planning in São Paulo, Brazil. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28(7):515–522. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2008.02.001.

- Sánchez-Triana E, Enriquez S. 2007. Using policy-based strategic environmental assessments in water supply and sanitation sector reforms: the cases of Argentina and Colombia. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 25:175–187.

- Silva HVO, Pires SHM, Oberling DF, La Rovere EL. 2014. Key recent experiences in the application of SEA in Brazil. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 16(2):1450009. doi:10.1142/S1464333214500094.

- Slunge D, Loayza F. 2012. Greening growth through strategic environmental assessment of sector reforms. Public Adm Dev. 32:245–261. doi:10.1002/pad.

- Slunge D, Tran TTH. 2014. Challenges to institutionalizing strategic environmental assessment: the case of Vietnam. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 48:53–61.

- Stoeglehner G, Brown AL, Kørnøv LB. 2009. SEA and planning: ‘ownership’ of strategic environmental assessment by the planners is the key to its effectiveness. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):111–120.

- Tetlow MF, Hanusch M. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(1):15–24. doi:10.1080/14615517.2012.666400.

- Therivel R. 1993. Systems of strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 13:145–168.

- Therivel R. 2010. Strategic environmental assessment in action. 2nd ed. London: Earthscan.

- Therivel R, Minas P. 2002. Measuring SEA effectiveness: ensuring effective sustainability appraisal. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 20:81–91.

- Tshibangu GM, Montaño M. 2016. Energy related strategic environmental assessment applied by multilateral development agencies — an analysis based on good practice criteria. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:27–37.

- UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe). 2003. The protocol on strategic environmental assessment. 2018 Jan 25. www.unece.org/env/eia/sea_protocol.htm.

- Van Buuren A, Nooteboom S. 2009. Evaluating strategic environmental assessment in The Netherlands: content, process and procedure as indissoluble criteria for effectiveness. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27:145–154.

- Van Doren D, Driessen PPJ, Schijf B, Runhaar HAC. 2013. Evaluating the substantive effectiveness of SEA: towards a better understanding. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 38:120–130.

- Victor D, Agamuthu P. 2014. Policy trends of strategic environmental assessment in Asia. Environ Sci Policy. 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2014.03.005.

- Von Seht H. 1999. Requirements of a comprehensive strategic environmental assessment system. Landsc Urban Plan. 45:1–14.

- Walker H, Spaling H, Sinclair AJ. 2016. Towards a home-grown approach to strategic environmental assessment: adapting practice and participation in Kenya. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 34(3):186–198.

- Wallington T, Bina O, Thissen W. 2007. Theorising strategic environmental assessment: fresh perspectives and future challenges. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(7):569–584.

- White L, Noble B. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment in the electricity sector: an application to electricity supply planning, Saskatchewan, Canada. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(4):284–295.

- Wirutskulshai U, Sajor E, Coowanitwong N. 2011. Importance of context in adoption and progress in application of strategic environmental assessment: experience of Thailand. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31(3):352–359. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.01.001.

- World Bank, University of Gothenburg, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Netherlands Commission for Environmental Assessment. 2011. Strategic environmental assessment in policy and sector reform: conceptual model and operational guidance. October. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-8559-3.