ABSTRACT

The objective of this paper is to analyze a tiering scoping approach developed to identify critical multidimensional sustainability issues and impacts of a large infrastructure project: the land transport project linking northern Brazil with a new port on Guyana’s coast. The Inter-American Development Bank awarded a technical assignment to develop the terms of reference of a country environmental assessment, a strategic environmental and social assessment and an environmental and social impact assessment of the project(s). The complexity of the issues at stake lead to the design of a tiered assessment process supported by wide-ranging participative sessions involving 170 individuals from Guyana and Brazil and from diverse sectors. The process identified ex ante conditionalities, critical factors for decision-making and valued socioenvironmental and governance components. Such complex and determinant planning initiatives for the future of a country need to be supported by comprehensive, well-sequenced scoping processes.

Introduction

Over the past 50 years, impact assessment has been affirmed on a global scale as an important tool to support decision making. Thirty years ago, Caldwell (Citation1988) commented that environmental impact assessment (EIA) was more than a technical process: it was foremost an informing and testing of policy. Since its origin EIA has developed and changed, influenced by the changing needs of decision-makers and the decision-making process, and by the experience of practice (Morgan Citation1998). Initially focused on assessing the environmental impacts of projects (air and water quality, noise, nature conservation, among others environmental factors), the focus gradually spread to other dimensions such as social and health impacts or, more recently, climate change or human rights impacts. Impact assessment is no longer limited to identifying the socioenvironmental effects of a project to contribute to the perception and selection of the best project to promote in a given territorial context. The thematic of analysis in impact assessment was extended, in a transition from the natural and exact sciences to the social and political sciences; it also spread to more strategic decision-making scales and therefore challenged the multiscalarity, multidimensional and multiactor contributions to system analysis and transformation. Impact assessment is now seen as a tool to design and implement better policies, plans, programs and projects (Partidário et al. Citation2012).

The objective of this paper is to analyze a tiering scoping approach developed to identify critical sustainability issues and impacts of a large infrastructure project: the land transport project linking northern Brazil with a new port on Guyana’s coast. The decision for the development of the new port and the transport link to Brazil is not yet defined. At the initial phase of the impact assessment process different modal options for the land link are still at stake: road, rail or intermodal solutions. Additionally, the location of the port has yet to be decided with reasonable alternatives in three river systems: Essequibo, Berbice and Demerara.

There has been a long history of discussions and studies relating to the improvement of the current 450-km-long road that connects the North of Guyana with the North of Brazil. Present road bisects a Rainforest Reserve in Guyana as well as indigenous communities that depend on the forest. Recently, the Government of Guyana (GoG) requested the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) assistance for a Technical Cooperation aimed at providing technical support to conduct the necessary studies for the preparation of a future operation to consolidate a land transport link with Brazil and the development of a deep-water port in Guyana. The principal objective of this Technical Cooperation was to conduct a scoping exercise that lead to the preparation of the terms of reference (ToRs) for the preparation of a country environmental assessment (CEA), a strategic environmental and social assessment (SESA) and an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) of the project(s).

This paper discusses how the complexity of the issues at stake lead to the design of a tiered assessment process to construct an integrated vision of the CEA, SESA and ESIA. It further debates how each tier should correspond to a specific spatial, institutional and temporal scale in order to address the complexity of planning and decision-making within which transformative change must occur. The tiering and comprehensive approach developed can contribute to support planning transitions and multidimensional decision-making processes for the sustainable development of the country that involves large sectors of the society such as transport, industry, economy, natural resources, environment, education or tourism.

Conclusions point that such complex and determinant planning initiatives for the future of a country need to be supported by comprehensive and participative scoping processes and well-sequenced approaches toward the CEA, SESA and ESIA in order to inform the design, construction and operation of a large infrastructure project.

Tiering in environmental assessment

Early in the development of the environmental assessment (EA) concept, the idea of tiering in the assessment at different planning levels was put forward as a key element. Tiering means preparing a sequence of EAs at different planning levels and linking them from more strategic level to more operational and project level assessments. Tiering means going from many to fewer issues, from more vague to more specific and from multimodal to unimodal.

A tiered approach minimizes the problem of EIA being only a ‘snapshot in time’. If well-resolved tiering provides the right tool to address the complexity of planning and decision-making, within which EAs must operate (Nooteboom Citation2000). Sequential assessments and their interactions mechanisms in theory and practice have been highly discussed in the literature (Thérivel and Partidário Citation1996; Nooteboom Citation2000; Fischer Citation2006a; Fischer and Onyango Citation2012; Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017). Tiering approaches facilitate strategic thinking when large infrastructure projects are to be developed thus enabling more effective short-term policies and facilitate strategic innovations on longer-term thinking toward sustainability (Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017). However, real-world planning practice often does not conform to such neat models and subsequently, transport planning might not necessarily happen in a stringently tiered manner, and project ideas may be developed, for example, based on an ad hoc basis or in a more bottom-up manner (Arts and Tomlinson Citation2005).

Tiering aims at ensuring that there are links not only from the strategic level to the concrete project level but also vice versa (Hildén et al. Citation2004). Hildén noted that tiering is not a simple top-down structure and that it is not always obvious, as the time lags between different tiers may be substantial. When a policy, plan or program precedes and influences a project decision, the policy, plan or program and the project decision are then, in effect, ‘tiered’. However, this works not only in a strict top-down manner, but also as a ‘bottom-up’ effect, in which lower-tier strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) and project EAs can lead to an improved awareness of the limitations of prevailing policies, plans and programs (Kirchhoff et al. Citation2011). This is particularly relevant in transboundary transport infrastructure development because transport planning is a long-term activity and that projects evolve over a number of years. Therefore, several tiers operate simultaneously with partly overlapping time horizons and with different degrees of policy orientation (Hildén et al. Citation2004).

The adoption of SEA evidenced these tiering needs. SEA practices significantly expanded after the 2000s by the adoption of the European SEA Directive and due to the promotion of SEA by the World Bank and similar agencies in international development cooperation (Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017). Some of these international institutions refer to SEA as SESA. They called for an integration of substantive aspects (e.g. economic, social and environmental), for an integration of different stakeholders (e.g. decision-makers, planners, affected communities) and for an integration of different instruments and tools (e.g. environmental management systems or landscape planning). Scholarly thinking on SEA has evolved considerably since then and has emphasized both the advantages and the dangers of tiered approaches (summarized in ).

Table 1. Tiered approaches to environmental assessment. Citation1996; Nooteboom Citation2000; Fischer Citation2006a; Nobel and Nwanekezie, Citation2017).

Effective tiering implies building bridges between different decision tiers and it can lead to institutional strengthening and better interorganizational cooperation (Fischer and Onyango Citation2012). Fischer (Citation2006b) developed a systems-based SEA framework for transport planning designed as a hierarchical system consisting of five main assessment tiers:

policy-related SEA

network-plan-related SEA

corridor-plan-related SEA

(investment) program-related SEA

Project-related EIA

Nevertheless, some of the criticisms toward SEA processes, regarding their excessive focus on the content and assessment processes while disregarding governance structures and policy-making processes (Partidário Citation2015; Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017), reinforce the need for and the advantages of developing strategic level assessments. Noble and Nwanekezie mention that ‘several scholars are now advocating for a shift in thinking about SEA, and for an advancement in current SEA practice toward a policy, institutional, integrated and strategic-oriented approach—one that provides for a better understanding of the complex institutional arena and governance conditions of strategic decision processes; ensues the creation and implementation of strategic actions that lead to more informed, and influential policies, plans and programs and development decisions’ (Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017, p. 166).

Although tiering is an intrinsic notion in SEA literature and practice, in recent years it has been ‘notable by its absence’ remaining an unresolved concern: ‘if SEA of any approach is to be influential in influencing decisions and actions, the notion and practice of tiering in SEA, particularly the institutional arrangements needed to ensure effectively tiered processes, needs to be revisited by the scholarly community’ (Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017, p. 171).

Realizing the full potential of tiering approaches requires a more strategic process than what is currently evident in practice and needs to be directed to understand the complex institutional arena and governance conditions of decision processes (Partidário Citation2015; Noble and Nwanekezie Citation2017) and this is what the approach described and analyzed in this paper intends to do.

Materials and methods

The transportation sector of Guyana remains critical for the economic and social advancement of its economy and population. In recent times, Brazil has indicated a desire to expand their business frontiers into Guyana through joint ventures in the areas of ethanol production, soya and assistance to Guyana with its renewable energy drive as it works toward becoming a low carbon resilient economy within the Green Economy Framework. But many of these initiatives hinge on the need for an efficient and well-maintained land link between the two countries and adequate port facilities in Guyana.

It is within the above context that the GoG is keen to establish an efficient and functioning transportation link between the Brazilian States of Roraima, Pará and Amazonas and the town of Linden, within the heartland of Guyana. Furthermore, these Brazilian States are land locked with no direct access to ocean going shipping ports, and uses Atlantic ports in Brazil via the Amazon River and Venezuela.

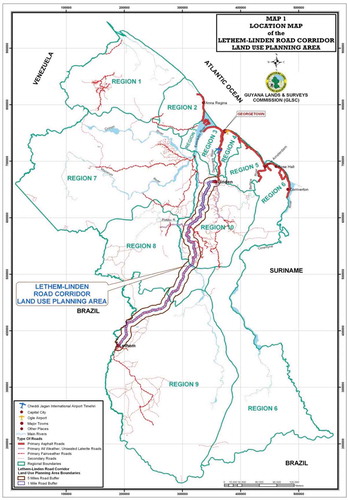

The current route from Linden to Lethem—on the Brazilian border—spans approximately 453.7 km (see ) and is made primarily out of gravel, so the road becomes very dusty during the dry season, and some sections become difficult to navigate and impassable during the rainy season. The entire length of the road from Brazil to Georgetown is 558 km and the section from Linden to Georgetown is a paved asphaltic surface. Furthermore, many of the bridges that support the current road are in need of repair and would require more durable structures being erected (SNC Lavalin International Citation2010).

Recognizing that this road artery cannot support the anticipated trade flow between the two countries, the GoG and the Government of Brazil (GoB) are proposing to conduct a feasibility study on establishing a land link to join the northern states of Brazil through the Guianas and facilitate shipping access from port(s) in Guyana.

The deep-water port in Guyana will handle four types of cargo: containers, general cargo, dry bulk and liquid bulk. Based on cargo forecasts and specific routing behavior, the traffic potential for the Guyana deep-water port has been derived in a recently published market study (HPC Citation2016). According to this study total cargo traffic potential will increase from 3.6 million tons in 2015 to 12 million tons in 2043, recording an average annual growth rate of 4.4%.

The solutions proposed for the deep-water port in previous studies must be revisited with the aim of identifying alternative feasible locations/options. Ideally, there are three alternative port layout configurations in three different rivers: Essequibo, Demerara and Berbice. For each of these alternative options, it will be necessary to identify and design the existing or future corridor to reach the Linden-Lethem land link corridor. Moreover, at the present stage of the process, no decision has been made on the transportation mode to be used for the land transport link, i.e. road or railway; type of surface if a road, i.e. flexible or rigid structure; or exact location for the land link, i.e. current corridor or changed alignment.

The complexity of the social and environmental issues at stake in the development of the Guyana-Brazil Land Transport Link and Deep Water Port project (thereafter named as Guyana-Brazil project) led to the design of a tiered assessment process by the Institute of Environment and Development (IDAD) based in Portugal and Development Policy and Management Consultants (DPMC) of Guyana. The methodology adopted to this scoping exercise was broader than usual and included the identification of ex ante conditionalities needed for project success, of critical factors for decision-making and of valued socioenvironmental components as well as the discussion on the governance conditions of the assessment process.

This process was supported by a compact and wide-ranging participative process with 22 sessions involving 170 individuals from Guyana and Brazil. A diverse group of stakeholders representing the different social actors projected to be affected and interested in this initiative was consulted. All of them displayed globally positive expectations regarding the importance and the various opportunities raised by this project even when identifying risks and challenges.

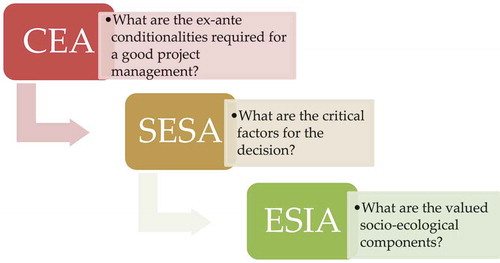

The tiering approach was constructed by an integrated vision of the processes involved in the CEA, the SEA and the ESIA, where each tier corresponds to a specific geographic and institutional scale. At each of the three assessment tiers it is fundamental to clearly define the objectives (), geographical boundaries and, finally, the stakeholders that need to be engaged.

Table 2. Objectives of the assessment tier.

The main strategic questions and sequential processes of the full scoping exercise are described in .

Results

Country environmental assessment

CEA reports (often called a country environmental analysis) usually provide a strategic assessment of the lending and technical assistance pipeline of a certain international financial institution. A CEA identifies priorities through a systematic review of environmental issues in natural resources management in the context of the country’s economic development and environmental institutions.

CEA objectives

The CEA of Guyana will allow reviewing of the relevant legislation, governance system and requirements of the country and regions where the project will be constructed. It is important to assess the governance framework to identify ‘who is who’ in policy, plan or program implementation, and what the respective responsibilities are. It will include various dimensions such as: the institutional responsibility for the decision (competences and responsibilities), the governance mechanisms and instruments available for institutional cooperation and the relevant actors that need to be engaged in a participative and collaborative process.

A CEA is significantly different form a large-scale and broad SEA (e.g. National Development Plan). Whereas such SEA would focus in the assessment of the best alternatives for development taking into account social, economic, political, cultural, health and byophisical considerations, the CEA aims mapping the structural ex ante conditionalities, i.e. the preconditions necessary for effective and efficient management of the project. This type of CEA resembles the ‘policy-related SEA’ with focus in visioning, objectives and policies setting proposed by Fischer (Citation2006b).

With this it will be possible to understand better the systemic obstacles and therefore to highlight priorities and appropriate timescales regarding different policy options and proposals for anticipatory measures.

Ex ante conditionalities

To evaluate the ex ante conditionalities required for a good project design, implementation and management, it is essential to identify critical structural conditions in a comprehensive and systematic manner.

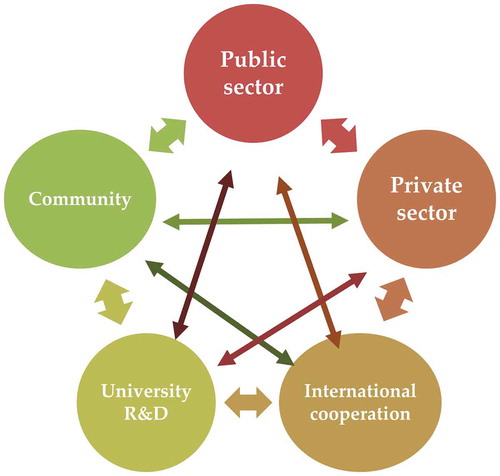

These conditions are determined by the five major societal pillars or group of actors identified in the case of Guyana (clustered in ). Understanding past and present roles, best practices and fragilities of these societal pillars in the country in an integrated way can minimize operational, management and financial risks of a large infrastructure project, such as the Guyana-Brazil project.

Considering the evaluation of several country reports for Guyana (UNDP Citation2010, Citation2017; IDB Citation2016), the assessment of the structural conditions associated with these five societal pillars, at different territorial scales, is critical for the project’s success.

The aim, therefore, should be to understand the governance context in order to minimize potential risks, to support the design of more appropriate strategies and actions and to effectively manage the direct and indirect impacts of the implementation of this project within a comprehensive sustainable development framework involving the most relevant stakeholders. Furthermore, an emphasis should be placed on connecting macroeconomic national goals with local and regional demands (FGV Citation2017). This critical first layer of assessment reflects precisely the concerns of Noble and Nwanekezie (Citation2017) raised above and intends to reinforce, in practice, a strategic-oriented approach toward the complex institutional arena and the governance conditions necessary for this large infrastructure project.

Strategic environmental and social assessment

The World Bank Group recognizes SEA, referred as Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) as a key tool to integrate environmental and social considerations into policies, plans and programs, particularly in sector decision-making and reform. SEA is a family of approaches that lie on a continuum. At one end, the focus is on impact analysis, at the other end, on institutional assessment. SEA incorporates environmental considerations across different levels of strategic decision-making: plan, program and policy. Under Guyana legislation, namely the Environmental Protection Act, SEA is not formally recognized.

SESA objectives

To guarantee the effectiveness of a SESA in Guyana the exercise must follow a strategic approach, which covers the key set of strategic issues relevant to the sustainable development of the region. Key strategic issues comprise the essential dimensions that the environmental and social assessment should address to understand the context, analyze the problems and establish relevant scales that allow a proper evaluation.

The SESA will combine two of the tiers suggested by Fischer (Citation2006a) encompassing the network-plan-related issues, establishing and evaluating intermodal network solutions mainly centered on the locations of the deep sea port and in the modal options still under appreciation, and the corridor-plan-related issues to asses the actual network needs in terms of transport corridors. This process can be enriched by identifying priority projects using multicriteria analysis or cost-benefit analysis.

Taking into account the geographical scale of the effects of the land link between Guyana and Brazil, SEA seems the suitable tier to identify and evaluate transboundary impacts. Bonvoisin and Horberry (Citation2005) refer that transboundary SEA effective application requires established cooperation mechanisms at regional level and that public involvement is crucial for identifying and addressing key issues. These authors concluded that one of the major barrier seems to be at political level: unwillingness to enter into transboundary agreements and difficulty of coordinating central and regional level responsibilities. Contrasts (economic, geographical, population, culture) between Guyana and Brazil might enhance these coordination difficulties emphasizing the need for direct interaction with Roraima State institutions. According to Marsden (Citation2011) building trust and goodwill regarding issues of common concern is a precondition to international cooperation, and applying procedures in an ad hoc manner initially is certainly better than not applying them at all, especially if lessons learnt from the process leads to acceptance and greater formality at a later stage.

The development of the SESA will also support the identification of project alternatives that should not be based solely on social and environmental criteria. Preliminary engineering studies are necessary to evaluate the technical feasibility of the alternative solutions, as well as to serve as the basis for the required economic data. In fact, the complete set of available and feasible alternatives has yet to be identified, discussed and assessed such as the macro and exact location of the port, how to access the port facility, or the final layout of the land transport link.

As such, the SESA should further contribute to the:

identification of critical areas for biodiversity and ecosystems, as well as, protected and/or conservation areas;

identification of available baseline surveys and investigations and/or surveys, and investigations that should be conducted, complemented and/or enhanced;

preparation and scoping of subsequent ESIA.

With the conclusion of the SESA, a first and crucial decision moment will occur: the selection of feasible alternatives that require further engineering studies. These alternatives will contribute to define the final layout of the overall solution to link a deep-water port in Guyana with its hinterland and Brazil. This layout will be assessed at project level through an ESIA. It may also enhance international cooperation, raising awareness of the key strategic issues in such cooperation, and so help avoid conflict (Cedeño Citation2008; Schrage and Bonvoisin Citation2008).

Key strategic issues

It is crucial to identify the key strategic issues that need to be assessed for a good decision-making process. The strategic issues should explicitly look at indirect and long-term effects and consider mitigation measures as an integral part of the design of the port and transport link.

To identify the key strategic issues for this umbrella program, a set of different steps were considered. The key strategic issues were the result of:

the views and concerns of the consulted stakeholders in both countries;

the analysis of key strategic documents that provided consistency with terms and international and national goals (e.g. IDB (Citation2012, Citation2016); MPG and UN Environment (Citation2017) Framework of the Guyana Green State Development Strategy and Financing Mechanisms);

the examination of the State of the Environment of Guyana (UNDP Citation2017);

The consideration of key socioeconomic and institutional issues of Guyana as well as the ones that resulted from important studies undertaken on the outcomes of similar projects in Brazil and South America (especially on vulnerable groups and ethnic minorities) (Redwood Citation2012; FGV Citation2017);

the opinions of the experts in environmental, social and institutional issues;

and, most importantly, the analysis of the implication of these strategic issues for sustainable development in Guyana, taking as guiding frameworks three core guidelines for sustainable transport infrastructure: the European Union definition of sustainable transportation (EU Citation2001), the World Bank Environmentally Sustainable Road Criteria (Montgomery et al. Citation2015) and the IAIA Principles for Sustainable Infrastructure (IAIA Citation2015);

the consideration of Guyana’s goal to complete the Linden to Mabura Hill road and a possible bridging of the Kurupukari River and the Brazil’s goals to develop a highway and other supporting infrastructure.

Thus, this process enabled a transparent, open, participative and scientifically based identification of a set of key issues relevant to the sustainable development of the region and to the structure of the technical analysis.

As a result of this exercise a set of five key strategic issues were identified (see ).

Figure 4. Key strategic issues for the strategic environmental and social assessment of the Guyana-Brazil project.

These issues aim to identify the aspects that the decision-making process must consider in the design of the development strategy and of the actions to be implemented, ensuring a strong focus on decision issues. Therefore, the technical analysis should be structured based on these key strategic issues.

Environmental and social impact assessment

According to the Inter-American Development (IDB) Bank’s safeguard policy ESIAs are prepared for projects with potentially substantial environmental and social impacts.

ESIA is a preventive instrument of social and environmental policy and land use planning that ensures that the likely environmental consequences of a particular investment project are analyzed and taken into account in its approval process.

Impact assessment regulation in Guyana requires that a developer of a road and a harbor shall apply to the Environmental Protection Agency for an environmental permit and shall submit with such application a summary of the project including information on: (i) the site, design and size of the project, (ii) possible effects on the environment, (iii) the duration of the projects and (iv) a nontechnical explanation of the projects. Every environmental impact assessment shall identify, describe and evaluate the direct and indirect effects of the proposed project on the environment including: human beings, flora and fauna and species habitats, soil, water, air and climatic factors, material assets, the cultural heritage and the landscape, natural resources including how much a particular resource is degraded or eliminated, and how quickly the natural system may deteriorate, the ecological balance and ecosystems and the interactions between the factors listed above.

ESIA objectives

The construction and operation of the land transport link and of the deep sea port have significant positive and negative impacts at a local and regional level, mainly in remote locations in developing countries where transport infrastructure is scarce. As indicated by Fischer (Citation2006b) this tier will focus on the analysis of current situation, optimization of the project design in terms of policy objectives and targets, the monitoring of actual developments and assessment of localized impacts.

At this tier, the main objective of this scoping exercise was to identify and assess the Valued Socioecosystem Components (VSEC). VSEC can be defined as an environmental or social element of an ecosystem that is identified as having scientific, ecological, social, cultural, economic, historical, archaeological or aesthetic importance. The value of an ecosystem component may be determined on the basis of cultural ideals or scientific concern. In practical terms, a VSEC is some component of the environment that has some ‘value’ (where value could be inherent or could be ascribed to it by an individual, a community and a society) and can be measured (either quantitatively or qualitatively).

Previous identification of VSEC ensures that the ESIA will deal with the critical project specific issues.

Valued socioecosystem components

VSEC have been identified in the scoping exercise, as the result of the mentioned methodological process, which resulted in five environmental and social components with special value:

Natural protected areas

Indigenous communities

Groundwater and drainage systems

River dredging

Urban development

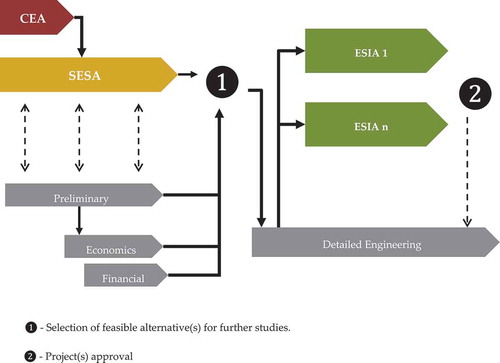

Discussion

that previously described the adopted tiering process, shows a link between the three levels of assessment as well as an apparent temporal sequence: the CEA first, followed by the SESA and finally the ESIA study. It is relevant to analyze and discuss this sequence because during the full assessment process there are some critical decision-making points that are not instantaneous. Decision making is time consuming and will introduce temporal gaps in the full assessment process. Also, as it was underlined in , if timeframes among tiers are not coordinated they may overlap or become outdated or disconnected.

Therefore, the tiering process should start with the preparation of the CEA. The CEA will focus on the recognition of all the governance conditionalities necessary for a good project management to be in place. It should focus on the decision-making system, the legal requirements and the power and competency of the responsible stakeholders, based on the identified five societal pillars. The country of focus for the CEA is Guyana. The CEA is independent from the other two tiers and can start autonomously but its outcome will give an important contribution to the SESA especially on governance-related issues.

At the present level of maturity of this initiative, the SESA will have the key role on the decision-making process. In fact, the complete set of available and feasible alternatives has yet to be identified, discussed and assessed: for instance the macro and exact location of the port, how to access the port facility, or the final layout of the land transport link (e.g. railway or road, if road new or upgrade of the existing infrastructure, rigid or flexible). These alternatives will be at the core of the strategic assessment and will support the strategic decision of the GoG.

Nevertheless, the decision will not be based solely on the SESA: preliminary engineering studies are necessary to evaluate the technical feasibility of the alternative solutions, as well as to serve as the basis for the required economic studies. Ideally, the preliminary design of the engineering solution is developed with a strong interaction with the SESA team. Finally, an additional financial study will probably be necessary to support decision making (see ).

This first decision moment (❶) is crucial for the definition of the final layout of the overall solution to link a deep-water port in Guyana with its hinterland and Brazil. Eventually, the decision might not be completely finalized and decision makers will resolve that a few alternatives (not only one) will be kept for further studies.

These decisions are complex and determinant for the future of land planning of Guyana. It is in its own nature a multidimensional decision involving large sectors of the society: transport, industry, economy, natural resources, environment and tourism. Often the inherent complexity of this type of decisions results in long decision-making processes (months to years). For an external observer, this time lag might look almost as a suspension of the decision-making process but practice shows that this apparent gap is needed to reach an informed and publicly accepted verdict. Concerns for renewed dialogue and cooperation with Brazil in such a transboundary large project help avoid conflict and facilitate decision-making processes in the field.

After the formal decision upon the final layout is made it is necessary to prepare detailed engineering projects. Finally, these projects will be scrutinized through an environmental and social impact assessment procedure.

As such, at this stage, there could be a single ESIA to assess the entire link project. However, probably several ESIA will be necessary, each one corresponding to a specific project. It is easy to foresee the need of at least two ESIA: one for the land transport link and another for the deep-water port. Eventually the transport link could be split into multiple subprojects: for instance the 450-km-long project could be split into approximately 100 km sections each with its own territorial and engineering specificities. Each of the ESIA will require the preparation of specific ToRs. In this case, the preparation of ToR for the ESIA prior to the decision upon the final layout of the link seems premature because there is a total lack of details about the technical project and of the territory needed to identify local impacts and benefits.

With the completion of the ESIA procedures comes the evaluation stage and the rejection or approval of the projects (❷). In case of final approval, the project might be reviewed to include environmental and social mitigation measures identified during the ESIA process.

Conclusions

There is an increasing appetite for a land transport link and deep-water port connecting south-western Guyana and northern Brazil. This has led to renewed dialogue and potential moves by the Governments of Guyana and Brazil to make this a reality. More importantly, the commissioning of these multiple studies aims to arrive at an informed consensus position with regards to the nature of the land transport link and the siting of the deep-water port. Consequently, scoping was focused on the identification of what is relevant and critical for an informed decision making of a transboundary, large and complex infrastructure project and proposed a tiered approach to allow for a sustainable development planning and decision-making process.

In conclusion, given the absence of tiering approaches in impact assessment literature and practice in recent years, this paper underlines the need to reinforce this practice and proposes a comprehensive and well-sequenced assessment process that needs to be taken toward completing the CEA, SESA and ESIA of this project. If they are to truly inform the design, construction and operation of a modern, efficient and state of the art land transport link and deep-water port, synergies will need to be established early and a well-coordinated approach adopted. The full potential of this tiering approach requires a strategic process. Anything less is likely to lead to a further round of elaborate studies, disjointed deliverables and reduced benefits of this significant project for both Guyana and Brazil.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arts J, Tomlinson P. 2005 Sept. EIA and SEA tiering: the missing link? Position Paper prepared for the meeting on SEA of the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA); Prague.

- Bonvoisin N, Horberry J. 2005. Transboundary SEA: position paper. IAIA Conference on International experience and perspectives in SEA; Sept 26–30; Prague.

- Caldwell L. 1988. Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA): origins, evolution, and future directions. Impact Assess. 6(3–4):75–83.

- Cedeño M. 2008. Assessment of transboundary environmental impacts in developing countries: the case of Central America. In: Bastmeijer C, Koivurova T, editors. Theory and practice of transboundary environmental impact assessment. Vol. 6. Boston (Ch): Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; p. 119–132.

- [EU] European Union Council of Ministers for Transport and Telecommunications. 2001. Strategy for integrating environment and sustainable development into the transport policy. Adopted at the 2340th meeting of the European Union’s Council of Ministers; Apr 4–5. Luxembourg.

- [FGV] Fundação Getúlio Vargas. 2017. Large-scale projects in the Amazon: lessons learned and guidelines, Fundação Getúlio Vargas. Centro de Estudos em Sustentabilidade (CES); [accessed 11 Feb 2019]. http://www.gvces.com.br/large-scale-projects-in-the-amazon-lessons-learned-and-guidelines?locale=en.

- Fischer TB. 2006a. Conference report: IAIA conference on ‘international experience and perspectives in SEA’. J Environ Assess Policy Manag. 8(4):495–504.

- Fischer TB. 2006b. Strategic environmental assessment and transport planning: towards a generic framework for evaluating practice and developing guidance. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 24(3):183–197. doi:10.3152/147154606781765183.

- Fischer TB, Onyango V. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment-related research projects and journal articles: an overview of the past 20 years. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(4):253–263. doi:10.1080/14615517.2012.740953.

- Hildén M, Furman E, Kaljone M. 2004 Jul. Views on planning and expectations of SEA: the case of transport planning. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 24(5):519–536.

- [HPC] Hamburg Port Consulting GmbH. 2016 Nov. Guyana-Brazil land transport link and deep water port - market study - final report; [accessed 2018 Jun 1]. https://finance.gov.gy/publications/guyana-brazil-land-transport-link-and-deep-water-port-market-study/.

- [IAIA] International Association for Impact Assessment. 2015 December. Draft principles for sustainable infrastructure approved at the closure of the IAIA special symposium on sustainable mega-infrastructures. Panama City (FL): International Association for Impact Assessment.

- [IDB] The Inter-American Development Bank. 2012. IDB country strategy with the cooperative republic of Guyana 2012–2016. Author.

- [IDB] The Inter-American Development Bank. 2016. Approach paper Guyana 2012–2016 country program evaluation [accessed 11 Feb 2019]. https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/7679/Approach-Paper-Country-Program-Evaluation-Guyana-2012-2016.pdf?sequence=1IDB(The Inter-American Development Bank). Country Program Evaluation: Guyana 2012-2016.

- Kirchhoff D, McCarthy D, Crandall D, Whitelaw G. 2011. Strategic environmental assessment and regional infrastructure planning: the case of York Region, Ontario, Canada. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 29(1):11–26. doi:10.3152/146155111X12913679730430.

- Marsden S. 2011. Assessment of transboundary environmental effects in the Pearl River Delta region: is there a role for strategic environmental assessment? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31(6):593–601. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2010.03.010.

- Montgomery R, Schirmer H Jr., Hirsch A. 2015. Improving environmental sustainability in road projects, environment and natural resources global practice discussion paper 6, February, 2015. Washington DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- Morgan RK. 1998. Environmental impact assessment: a methodological perspective. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- [MPG] Ministry of the Presidency of Guyana, UN Environment. 2017. Framework of the Guyana green state development strategy and financing mechanisms; [accessed 11 Feb 2019]. http://www.greengrowthknowledge.org/sites/default/files/Framework%20for%20Guyana%20Green%20State%20Development%20Strategy%2028-03-17.pdf.

- Noble B, Nwanekezie K. 2017. Conceptualizing strategic environmental assessment: principles, approaches and research directions. Environ Impact Assess Review. 62:165–173. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2016.03.005.

- Nooteboom S. 2000. Environmental assessments of strategic decisions and project decisions: interactions and benefits. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 18(2):151–160. doi:10.3152/147154600781767510.

- Partidário MR. 2015. A strategic advocacy role in SEA for sustainability. J Environ Assess Policy Manag. 17(1):1–8. doi:10.1142/S1464333215500155.

- Partidário MR, Den Broeder L, Croal P, Fuggle R, Ross W. 2012. Impact assessment. Int Assoc Impact Assess, FASTIPS. 1(April):2012.

- Redwood J. 2012. Managing the environmental and social impacts of major road investments in frontier regions: lessons from the Inter-American development bank’s experience/John Redwood. IDB Technical Note.449.

- Schrage W, Bonvoisin N. 2008. Transboundary impact assessment: frameworks, experiences and challenges. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 26(4):234–238. doi:10.3152/146155108X366004.

- SNC Lavalin International. 2010. Environmental and social impact assessment report. Unpublished Report.

- Thérivel R, Partidário MR. 1996. The practice of strategic environmental assessment. London (UK): Earthscan. eBook ISBN 9781134176144.

- [UNDP] United Nations Development Programme. 2010. Assessment of development results Guyana: evaluation of UNDP contribution; [accessed 11 Feb 2017]. http://www.oecd.org/countries/guyana/47861372.pdf.

- [UNDP] United Nations Development Programme. 2017. Guyana state of the environment (SoE) report 2016. United Nations Development Programme in collaboration with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) of Guyana.