ABSTRACT

Fourteen years since the implementation of the European SEA Directive, the effectiveness of the English system of Local Plan sustainability appraisals/strategic environmental assessments (SA/SEAs) is analysed, based on 15 case studies, five interviews, and questionnaires of 11 planners. Substantively, SA/SEA leads to fine-tuning of plan policy wording and a more robust choice of development sites, but to only limited wider influence on the plan. Normatively, there seems to be a direct conflict between the requirement that Local Plans must provide enough housing for ‘objectively assessed need’, and environmental protection. From a pluralist perspective SA/SEA reports are very long, and although the statutory consultees often comment on them, the public do so only infrequently. It is in the transactive dimension that the largest changes have taken place: both consultants and planners have had to do more with less. This does not yet seem to have negatively affected the other effectiveness dimensions, but may not be sustainable over time.

1. Introduction

Local Plans in England are typically 15- to 20-year plans that set out the strategic priorities for development of local authority areas. They cover housing and employment development, related infrastructure and community facilities, and protection for the local environment. Local Plans are prepared by local planning officers, in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders including the public; approved by local politicians; and tested by an independent inspector who checks the plan’s ‘soundness’ at a formal public examination, and who may recommend additional changes before the plan is adopted.

Local Plans in England require not only strategic environmental assessment (SEA) under the Environmental Assessment of Plans and Programmes Regulations 2004, but also sustainability appraisal (SA) under the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004. The two processes are carried out jointly, with the SEA subsumed within the broader SA process which also considers social and economic issues. This is not the case for other types of plans to which only SEA applies. Part of the ‘soundness’ of Local Plans comprises whether an adequate SA/SEA has been carried out. Roughly two-thirds of all SEAs carried out in England are for Local Plans.

England’s SA/SEA process and its effectiveness have already been extensively studied (Fischer and Onyango Citation2012), although mostly before 2010. Since 2010, as discussed below, the plan-making context has changed dramatically for the worse. This article considers the effectiveness of SA/SEA of Local Plans in this new, more challenging, context. After an introduction to the past literature on SA/SEA effectiveness in England, this paper reviews how effective SA/SEAs of English Local Plans currently are in terms of the substantive, normative, pluralist, and transactive dimensions. It concludes with suggestions for improving SEA effectiveness in England. The situation in Wales, and particularly in Scotland and Northern Ireland, is different, and these so-called devolved administrations are not covered here.

2. Literature review

SA/SEA practice, and research into SEA effectiveness, in England can be split into three broad tranches. The first tranche was from 1993, when the (then) Department of Environment published guidance on environmental appraisal of development plans (DoE Citation1993), until the implementation of the SEA Directive in 2004. During this time, many planners carried out a rudimentary form of environmental appraisal of their plans, some of the first of their kind in the world. From 2004 until about 2010, the second tranche could be described as the golden days of SA/SEA. There were early SA/SEA pilots, SA/SEA guidance was published (e.g. ODPM et al. 2005; PAS Citation2006, Citation2008), and innovative SA/SEA approaches—topic-based (in contrast to task-based) assessments, GIS overlay mapping, consultant guidance etc.—were trialed.

Then the global recession hit and the Conservatives came into power in 2010. Since then there has been no update to the 2005 guidance except for an advice note voluntarily prepared by the Royal Town Planning Institute to fill the gap (RTPI Citation2018). The UK government has run an ‘austerity budget’ which has meant that local authority planning department budgets have been cut by almost 53% in real terms (NAO Citation2018) with more cuts to come (LGA Citation2018). A government commission has proposed a severe roll-back of SA/SEA activity (LPEG Citation2016). Several high-profile successful legal challenges to SA/SEAs (Therivel Citation2013) have put intense pressure on planning authorities to avoid the same. Research into SA/SEA in the UK seems to have paralleled this, with much research taking place until 2010, and a noticeable slow-down since then.

In substantive terms, during the first tranche, surveys of planners found that the (then) local development plans were being increasingly changed in response to appraisal findings, from about 50% of plans in 1995 to about 70% in 2002 (Therivel Citation1995, Citation1998; Therivel and Minas Citation2002). The implementation of the SEA Directive, with its greater emphasis on an evidence base, consideration of alternatives, and monitoring, led to further improvements in the substantive effectiveness of SA/SEA. By 2008, the proportion of plans being changed as a result of SA/SEA had increased to 70–80% (Therivel et al. Citation2009; Sherston Citation2008; Ezzet Citation2016).

However most of the changes continued to be relatively minor—the addition or removal of plan policies, and changes to development sites—rather than more significant changes to alternatives or to the entire approach of the plan (Curran et al. Citation1998; Sherston Citation2008). A government-commissioned study on SA/SEA effectiveness had similar conclusions:

“SA/SEA generally plays a ‘fine-tuning’ rather than a ‘plan-shaping’ role… many appraisals tend to take plan policies at face value rather than questioning the extent to which they will be implemented on the ground” (CLG Citation2010, p. 5–6).

In normative terms, a review of 45 SA/SEAs of core strategies—the successor to local development plans—analysed what the SA/SEA reports said about the impacts of the core strategies (Therivel et al. Citation2009). This concluded that SA/SEAs were not ‘leading to a high level of protection of the environment’; they were partly ‘promoting sustainable development’; and they were partly ‘contributing to the integration of environmental considerations into the preparation and adoption of plans’. In Ezzet’s (Citation2016) survey of planners, 43% agreed that SA/SEA changed or influenced institutional norms or management practices.

Comparatively little research has been carried out on the pluralist effectiveness of the English SA/SEA process. The research that does exist suggests that public participation in SA/SEA has been generally limited (Short et al. Citation2004; Therivel and Walsh Citation2005; CLG Citation2010), with possibly a faint trend towards improving public participation over time.

In transactive terms, before the SEA Directive was implemented, about 60% of planners felt that environmental/sustainability appraisal was an effective use of resources. There was a clear correlation between the number of person-days spent on the appraisal and the level of changes to the plan resulting from the appraisal (Therivel and Minas Citation2002). This trend continued after the SEA Directive was implemented (Short et al. Citation2004; Therivel and Walsh Citation2005; CLG Citation2010). However in 2016 an expert group to government charged with speeding up and simplifying the local plan-making process called SA/SEA ‘one of the most time consuming aspects of plan making’ (LPEG Citation2016, p.5) and proposed ‘a more proportionate approach’ (LPEG Citation2016, p.35) of tougher SEA screening, and less emphasis on SA/SEA being iterative and considering alternatives. In contrast, a 2016 survey of planners with 35 respondents found that 71% felt that the benefits of SA/SEA outweigh its costs (Ezzet Citation2016).

The procedural effectiveness of English SA/SEAs—the quality of the SA/SEA reports—has also been studied. For instance, a review of SA/SEAs for 117 Core Strategies (Fischer Citation2010) found that the earlier stages of SA were carried out better than the later stages. Eight years later, Fischer and Yu (Citation2018) recorded similar findings for 15 neighbourhood plan SA/SEAs. Contextual/procedural factors such as an early start, good consideration of alternatives, the use of consultants as ‘critical friends’, and guidance were all found to help produce good quality SA/SEAs for neighbourhood plans (Fischer and Yu Citation2018).

The ‘Brexit’ process is adding an entirely new layer of uncertainty to SA/SEA effectiveness in England (Fischer et al. Citation2018). Initial indications are that not much will change legally in the short term. However, in the event of a ‘no deal’ parting of the ways, or in the longer term, government may move to limit or scrap SEA requirements (Bond et al. Citation2016).

3. Methodology

The aim of this study was to test whether previous trends in SA/SEA effectiveness continue to hold, and to suggest ways of improving effectiveness. The methodology involved a review of the documentation for 15 SA/SEAs of Local Plans, interviews of associated consultants and planners, and a questionnaire of planners.

3.1. SA/SEA document analysis

The SA/SEA reports for 15 Local Plans that had been adopted most recently at the time of writing (July 2018, see ) were analysed. The plans were identified from a Planning Inspectorate timetable of Local Plan progress (Gov.uk Citation2018).

Table 1. Local plans reviewed, and availability of associated SA/SEA documents.

Of the 15 plans, 10 had SA/SEAs carried out by consultants: four by one consultancy, two by another, and the remaining four by different consultancies. Four of the SA/SEAs had been carried out in-house, and one partly in-house and partly by consultant. SA/SEA reports were available on the local authority website for 14 of the 15 plans, and the final one was sent upon request.

In the European Union, the post-plan adoption ‘SEA statement’ should be a veritable font of useful data on substantive and pluralist effectiveness, since the SEA Directive requires the compilation and dissemination of:

‘a statement summarising how environmental considerations have been integrated into the plan or programme and how the environmental report prepared pursuant to Article 5, the opinions expressed pursuant to Article 6 and the results of consultations entered into pursuant to Article 7 have been taken into account in accordance with Article 8 and the reasons for choosing the plan or programme as adopted, in the light of the other reasonable alternatives dealt with’ (Article 9.1(b)).

SA/SEA statements were available for 11 of the 15 plans. Where easily available, other related documents, including the comments made by statutory consultees and the public to the plan and SA/SEA, were also reviewed.

The substantive SEA effectiveness dimension is about the extent to which a plan is changed as a result of its SEA. These changes include improved environmental or socio-economic conditions compared to what otherwise would have taken place, and other improvements to the plan resulting from the SEA (e.g. clearer wording, more defendable). For this article, the analysis of substantive effectiveness focused on what alternatives and mitigation measures were considered in the SA/SEA reports, and their integration into the plan as captured by the post-adoption SEA statements.

The normative SEA effectiveness dimension considers whether the SEA process achieves its ideal, normative goals, which could include compliance of the plan with the agency’s mandate, regulations or higher-level policy commitments; reflection of the values in the policy context; sustainable development, or environmental protection; environmental justice; and resilience. Fully testing this could be very complex. Instead, this article considers whether the SA/SEAs explicitly tested the plan against four environmental sustainability targets:

Achievement of the targets set in the European Water Framework Directive regarding the quality of surface and ground waters (House of Commons Citation2018).

Achievement of favourable status of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (a national level nature conservation designation) and/or net biodiversity gain (Defra Citation2011; HM Government Citation2018).

Reduction of inequalities, measured by changes in the Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Resilience, as defined by Slootweg and Jones (Citation2011), as this will be an important way of coping with changes such as Brexit, economic shocks and climate change.

The SA/SEA reports were analysed in terms of 1. whether the framework used to appraise the various components of the plan—the ‘SA/SEA framework’—included reference to these four issues and 2. whether the SA/SEA report tested the plan’s final overall/cumulative assessment in terms of these issues.

It is also difficult to determine pluralist effectiveness without directly interviewing members of the public. Here an indirect indication of effectiveness is used by considering the responses of planners to consultation comments.

The transactive SEA effectiveness dimension focuses on the time and cost inputs versus the wider benefits of SA/SEA. It is difficult to consider this dimension in detail, since it would require ex-post analyses of the long-term costs and benefits of SA/SEAs, as well as their shorter-term costs and benefits. This research simply considers the length of reports—on the assumption that longer reports are more expensive to prepare, and take more time to read and comment on—and the general cost of Local Plan SA/SEAs.

3.2. Interviews and questionnaires

All of the SA/SEA authors were asked if they would be willing to be interviewed. Interviews were carried out with four consultants and one planner who, between them, had carried out nine of the 15 SA/SEAs reviewed.

Two SA/SEA effectiveness questionnairesFootnote1 were also distributed at a workshop for planners at which the (then) recently-published SEA advice note (RTPI Citation2018) was presented. Eleven practicing local authority planners from south east England responded (n = 7 for a closed-answer questionnaire, n = 4 for an open-answer questionnaire). They have no links to the case studies discussed above, but their comments are provided here as another view on SA/SEA effectiveness in England. Although London and the south east of England are more economically buoyant, and arguably subject to more development pressure, than elsewhere in England (Harari Citation2018), there is no reason to suppose that planners from the south east of England have views that are substantially different from planners elsewhere in England.

summarises what issues were considered in the document reviews, interviews and questionnaires to test the various types of SEA effectiveness.

Table 2. Issues considered to test different types of SEA effectiveness.

4. Substantive effectiveness

This section considers the substantive effectiveness documented in the SEA reports’ consideration of alternatives and mitigation measures, the post-adoption SEA statement, and interviews and questionnaires.

4.1. Alternatives in the SA/SEA reports

In the wake of several successful high-profile SEA-related legal challenges involving alternatives,Footnote2 the discussion of alternatives in English SA/SEA reports now tends to be quite good. Typically, it involves an identification of reasonable alternatives (possibly with a discussion of why other alternatives are not reasonable), then an assessment and comparison of alternatives using an SA/SEA framework, sometimes followed by a discussion of why the preferred alternatives are preferred. The rather artificial plan-wide alternatives (‘a more social plan, a more economic plan etc.’) and retrofitted alternatives that were often seen ten years ago (CLG Citation2010) have been eschewed in favour of ‘within-plan’ alternatives that better reflect the actual issues considered by planners. There is also no longer an indication of planning authorities ‘generating alternatives for every conceivable issue’ or making up alternatives for the purposes of SA/SEA (CLG Citation2010, Smith et al. Citation2011).

The process of developing a Local Plan tends to take several years, with multiple iterations or early reviews of the plan, often in response to a rapidly-changing policy environment (Lichfields Citation2017). In their discussion of alternatives, the final SA/SEA reports often referred back to previous SA/SEA reports and rounds of alternatives appraisals, including some that had been carried out almost ten years previously. Some of those reports were no longer publicly available, and so could not be reviewed. As such, the rest of this discussion is a worst-case scenario, with other options possibly also having been appraised by some local authorities.

shows the four types of alternatives considered most frequently in Local Plan SA/SEAs: the number of new homes that the plan should deliver, broadly where housing and economic growth should take place, specific development sites to accommodate housing and employment growth, and alternatives associated with individual plan policies such as those on affordable housing or provision of green infrastructure. The SA/SEA reports often told a clear ‘story’ where alternatives were narrowed down: first how much development was needed, then broadly where it should go, and then specifically where it should go. In particular, the sifting process from a long list of possible development sites to a short list of preferred sites was typically explained very well.

In one case, the SA/SEA report only described, but did not assess and compare, some alternatives considered during the plan-making process. The planning inspector was clearly unimpressed with this, and required the local authority to prepare an addendum on alternatives.

That said, it is difficult to know just how influential these assessments are in practice (as opposed to just documenting what is happening anyway), given that planners are constantly considering different ways of preparing their plan. As one of the SA/SEA reports says:

“It is… difficult to distinguish the influence of the SA relative to other influencing factors, but the key message is that the Council, informed by the SA, national policy and evidence, has sought to select the most sustainable options available to them for accommodating the growth identified as being needed by the city” (Coventry CC Citation2016, p.20).

4.2. Mitigation measures in the SA/SEA reports

The SA/SEA reports were also analysed in terms of whether they proposed mitigation measures, whether there was any documentation of the planning team response to the mitigation measures, and whether the planning team implemented the proposed mitigation measures. There was often more than one SA/SEA report (say an interim SA/SEA, a submission SA/SEA and a plan modification SA/SEA); in these cases, where they were straightforwardly available, all of these documents were analysed.

Mitigation measures were proposed in 13 of the 15 sets of SA/SEA reports: seven included detailed proposals for mitigation, five included some form of proposed mitigation, one only referred back to existing plan policies as mitigation, and in two cases it was not possible to find any proposed mitigation measures. However only three SA/SEAs were clear about whether/how the proposed mitigation was included in the final plan, with four more stating that the proposed mitigation had been taken into account by the planning team (or similar) but not explaining how: see .

Figure 2. Consideration of mitigation in SA/SEA reports.

* minimal: SA/SEA report refers only to other plan policies as mitigation, does not seem to try to consider whether other mitigation is needed, or says that mitigation has been considered but gives no evidence to support this.

Some of the proposed mitigation measures were vague or brief in the extreme, for instance referring only generally to ‘mitigation provided by other plan policies’ (Hull City Council Citation2016). In other cases, the planning officers clearly dismissed the proposed mitigation The best examples included tables showing significant effects, proposed mitigation or enhancement, and officer comments (i.e. whether the mitigation was included in the plan or not). For instance:

“Proposed mitigation: Revise the policy wording to seek to protect and enhance of heritage assets within the District in the first instance. Reference to particularly important heritage assets may be helpful here.

Officer comment: Amend bullet point eight as follows: It protects and/or enhances the built and historic environment and it does not result in substantial harm to, or loss of designated heritage assets….” (Derbyshire Dales DC Citation2016, p. 405).

All of the mitigation measures listed in the SA/SEAs were minor changes of wording rather than fundamental changes of direction. There seemed to be no clear link between who carried out the SA/SEA—whether in-house or by consultants—and the amount and quality of proposed mitigation, or the implementation of the mitigation.

4.3. Post-adoption SEA statements

Information about substantive effectiveness should be central to post-adoption SEA statements: they should indicate how policies have been amended, and what new policies have been included in the plan to integrate environmental considerations and act as mitigation. However, in practice the statements were weak on this. Four SEA statements were not on the local authority website. Most focused heavily on the SA/SEA methodology used, rather than providing ‘content’ information like what alternatives were considered and what changes were made to the plan. Most of the SEA statements said that the SEA led to changes to policy wording; many said that the SEA helped in the choice of sites for development; and some said that the SEA helped planners to identify more sustainable options for their plan (). However, this was typically in the form of generic statements, rather than providing clear examples of what had been done or clarifying that the proposed changes had actually been integrated into the plan, for instance:

“The SA identified options for consideration and, through the detailed appraisal of options and draft policies, identified environmental and wider sustainability implications and was ultimately a key influence on the policy decisions made in the [plan]… the SA was able to recommend the most sustainable options, propose mitigation measures and refine policy wording…” (Adur DC Citation2017, p. 5).

That said, four SEA statements did show how the plan was changed in response to the SA findings, two with tables showing the suggested mitigation and planning officers’ responses to the suggestions. However, again, all of the documented changes were limited to fine-tuning policy wording rather than leading to significant changes in plan direction.

4.4. Interviews and questionnaires

The interviews of consultants/planners concurred with the above findings, as shown at . The questionnaire of planners also suggests that SA/SEAs have some, but limited, effect on the plan: six out of seven respondents agreed that planners use the SA/SEA information to develop, review or discuss the plan during decision-making.

Box 1. Examples of interview findings about substantive effectiveness.

In terms of specific changes made to the plan as a result of SA/SEA, one respondent noted that a ‘new settlement’ option was explored to see whether mitigation measures could make it score better for inclusion in the plan, but then discarded; two respondents said that mitigation measures were included for individual sites; and others said that SA/SEA informed the site selection process and led to changes in policy wording. However, in two cases site allocation policies were largely unchanged ‘as they were more political’.

5. Normative effectiveness

5.1. SA/SEA report analysis

As discussed in the methodology section, the SA/SEA reports were reviewed to determine whether they tested the plan against targets on water quality, biodiversity, deprivation and resilience. shows the results of this analysis. The consideration of biodiversity was the best, with about half of the SA/SEA reports including a fairly detailed analysis of the plan’s impacts on this subject. Resilience fared the worst, with only five discussing it at all, and then only in the climate change sense. Examples of inclusion of the topic in the SA/SEA framework included:

Appraisal question: “Will the policy or proposal reduce water pollution from urban runoff, sewer flooding or other sources by promoting sustainable urban drainage (SUDS) measures and ‘water sensitive urban design’?” Associated indicator: “Environment Agency monitoring relating to chemical, biological and morphological indicators for the purposes of assessing the [River X and Y Brook] against EU Water Framework Directive Targets. (To achieve objectives by 2021)” (LB Sutton Citation2016, p. 79)

Appraisal question: “Will [the alternative or policy] help to reduce deprivation and ensure no group of people are disadvantaged?” (Hartlepool BC Citation2017, p. 8).

Examples of impact analyses dealing with these issues included:

“The available evidence, including the [relevant Water Resource Management Plan] and [Water Cycle Study], indicates that there are existing and future constraints with regard to water resources. In line with the Detailed WCS, it is recommended that as a minimum Local Plan Policy X should require developers to demonstrate that water consumption in the development will be managed at a level of 110 litres per person per day” (Telford & Wrekin Council Citation2016, p. 178).

‘Given that the wards in and to the south of the town centre are among the 20% most deprived in London, focusing growth in X is likely to result in positive effects in terms of reducing poverty and social exclusion” (LB Redbridge Citation2016a, p. 33).

5.2. Interviews and questionnaires

The consultant/planner interview responses took a broader view, generally considering whether sustainable development was achievable through Local Plans and SA/SEA: see .

Box 2. Examples of interview findings about normative effectiveness.

The closed-answer questionnaire of planners (n = 3, 4 or 5) asked how effective SA/SEAs were in promoting and achieving various dimensions of sustainability. Generally planners felt that SA/SEA is effective in terms of environmental protection (average 4.25 out of 5, with 1 denoting strong disagreement and 5 denoting strong agreement) and balancing social, economic and environmental factors (4.13), but ineffective in reducing deprivation and promoting equity between generations (2).

6. Pluralist effectiveness

6.1. SA/SEA report analysis

The extent to which SA/SEA reports documented consultation findings and planners’ responses to the consultation was analysed. indicates that good consultation on the scoping report and SA/SEA report happened in roughly five cases out of 14, sometimes in reports not clearly associated with the SA/SEA (e.g. separate consultation reports). Interestingly, different local authorities tended to do well for the scoping and the SA/SEA report consultations. In nearly half of cases, there was no reference in the SA/SEA documentation to consultation other than to say that it had happened.

Figure 5. Consideration of consultation responses in SA/SEA reports and other easily-available documents.

The SA/SEA reports documented some views about plans that were clearly strongly conflicting and had not been ironed out through the SA/SEA process. However generally, the comments by statutory consultees seem to have been given substantial weight. A typical good response to consultation was:

“Historic England: [Site X] has potential to cause harm to [a historic building], its designated landscape and [a Grade 1 church]. The impacts are not recognised in the SA. An area of ridge and furrow will be lost to the south of the site.

Council response: In the absence of a detailed assessment of effects upon heritage assets, the appraisal concentrated on strategic effects, which were predicted to be insignificant. A more detailed assessment has now been carried out, which identified potential effects on the setting of [the historic building]. These effects have been identified in the SA” (NW Leicestershire, p. 255).

There were also examples of good responses to individual residents, for instance:

“[Name of individual]: All tall building plans should be put on hold or cancelled…. Proper enforcement of the rules governing people in multiple-occupancy homes and illegal sheds should be priority…”

[Council response]: The Plan seeks to distribute growth in a sustainable manner as demonstrated through the Sustainability Appraisal… Policy [X] introduces criteria on converting larger homes to [homes in multiple occupation], and Policy [Y] reiterates that the Planning Service will work with other Council bodies to tackle the issue of beds in sheds…” (LB Redbridge Citation2016b, p. 13).

6.2. Interviews and questionnaires

The interviews of consultants/planners, instead, gave a rather depressing picture of the effectiveness of SA/SEA in involving the public ().

Box 3. Examples of interview findings about pluralist effectiveness.

The questionnaire of planners asked about how good SA/SEAs are at eliciting public participation, and how the public uses the SA/SEA information. The results (n = 6) suggest that, SA/SEA does a reasonable job of conveying information to the public (average response 4.2 out of 5), but does little to encourage or support a two-way discourse (2.8). It is particularly bad at empowering marginalised groups (1.8).

7. Transactive effectiveness

7.1. SA/SEA report analysis

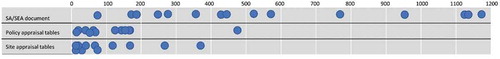

In the 15 case studies, the SA/SEA reports that were submitted for examination alongside the plan—this is the ‘official’ SA/SEA report that should fulfil all the legal requirements of the SEA Directive—ranged from 74 to 1132 pages long, with an average length of 355 pages—see . Three were over 1000 pages long. In most cases, earlier versions of SA/SEA reports (‘issues and options’ and/or draft SA/SEA reports) were referred to or listed in the examination documents, suggesting an even longer and more complex approach. Where the earlier information was not directly available, a rapid web-search was made for them: if these additional documents are also included, then the SA/SEA documents range from 206 to 1178 pages, with an average of 512 pages. It is quite possible that the rapid search did not uncover other, additional SA/SEA documents.

Looking at why these reports are so long, some of the submission reports duplicate parts of the other previous reports, so increasing the report length. In some cases the plans themselves are long, with many policies and proposed development sites. The tables that appraise the impacts of the plan policies against the SA/SEA framework take up a considerable proportion: where they exist, in 12 of the 15 SA/SEA reports, they range from 16 to 482 pages, with an average of 126 pages. The tables that appraise the impacts of development sites, in 11 of the SA/SEA reports, range from three to 379 pages, with an average of 107 pages. Just the analysis of the ‘policy context’—how the plan links with other plans and programmes—where it was available in eight SA/SEA context-setting scoping reports, takes between four and 63 pages, with an average of 36 pages. It is unlikely that anyone except affected developers and local residents will read any of this except for the assessments of the sites that affect them.

Some of the length—especially for the site appraisals—can also be explained by local authorities’ concern about legal challenge. The most likely form of legal challenge is from developers whose sites have not been included in the plan, so local authorities want a robust argument for why they have chosen and rejected sites. Some of the length can also be attributed to the many changes in English planning legislation and requirements over the past ten years. One SA/SEA document explains:

“[T]he evolution of the preparation of the [Local Plan] has been a long and challenging process, not least because it has straddled major changes in Government administrations and planning legislation and policy. For example, at the start of the process, there was a suite of national planning guidance documents and an emerging regional plan for the [wider region]. By the end of the process, the suite of national planning guidance had been swept away to be replaced by a single streamlined [national planning framework], and the [regional plan] had been revoked.” (Coventry City Council Citation2016, p. 20)

The Royal Town Planning Institute’s advice note on SEA (RTPI Citation2018) suggests ways to shorten the SEA, including less emphasis on the policy context, and testing the need for baseline data by asking what difference that information will make to the plan. This may help to streamline the SA/SEA process in the future.

7.2. Interviews and questionnaires

The consultant/planner interviews asked what the typical cost of an SA/SEA for a Local Plan is, and whether the benefits of SA/SEA outweigh the costs: see .

Box 4. Examples of interview findings about transactive effectiveness.

The questionnaire asked what, in the respondent’s view, the balance is between benefits and costs of SA/SEA. The answer was an almost perfect balance of views—see . The more detailed responses can be summarised by one pithy comment: ‘Bad ones lengthen [the planning process]. Good ones shorten.’

Figure 7. Questionnaire responses (n = 7) about costs v. benefits of Local Plan SA/SEAs.

* Four respondents did not answer this question.

When asked to conclude their interviews or questionnaires with open-answer suggestions for how SA/SEA effectiveness could be improved, budget issues interestingly did not arise. The parentheses below show the number of times this point was made:

Planners and politicians should not have pre-determined ideas; there should be no political interference in plan-making (4)

Ensure close collaboration between the SA/SEA team and the plan-making team, and make sure that plan-makers understand the value of SA/SEA (3)

Focus the assessment on key issues rather than aiming for comprehensiveness; keep it simple (3)

Capable individuals should carry out the SA/SEA and there should be time to do it effectively (3)

Start the SA/SEA early in plan-making, and integrate the two processes from the beginning (3)

Understand the environmental characteristics of the plan area (2)

Engage early with stakeholders (1)

The SA/SEA alternatives should be small enough in number and distinct enough so that a local newspaper would want to publish them: the ‘local paper test of reasonableness’ (1)

Consider all reasonable alternatives (thoroughly) and use that information to inform the plan (1)

Use the SA/SEA as a way of communicating the plan-making process and making it more transparent (1)

8. Discussion

The findings of this research suggest that, for most dimensions of SEA effectiveness in England, little has changed since about 2010. SA/SEA seems to be partly effective substantively, possibly more so than a decade ago. The analysis of alternatives is generally significantly improved, with alternatives better reflecting the choices actually being made by planners. At least some tweaking of the plan through SA/SEA mitigation is being made, roughly as frequently as a decade ago. SA/SEA helps to ensure that the selection of development sites is done in the full knowledge of their environmental, social and economic effects, even if the final reasons for selection are political. However, none of the case study plans were significantly changed as a result of the SA/SEA, possibly because planners already need to show that their plans support sustainable development.

Consistently with previous studies, this research suggests that English Local Plan SA/SEAs are not very normatively effective. There seems to be a direct conflict between the requirement that Local Plans must provide enough housing for ‘objectively assessed need’, and environmental protection. The former is a legal requirement; the latter seems to be treated as an attractive secondary aim which is routinely overridden by necessities of the former. Interestingly, although housing provision is a way of providing for the needs of future generations (intergenerational equity), the questionnaire results suggest that intergenerational equity as a whole is poorly considered in SA/SEA. Few SA/SEAs even mention sustainability targets set by international and national legislation, much less formally test the plan against them. As one of the questionnaire respondents added, ‘[planners] tend to focus on doing the best possible rather than ensuring truly sustainable development.’

From a pluralist perspective, on the whole, planners and consultants seem to make a reasonable effort to consult statutory consultees and the public about the plan and its SA/SEA. However, the SA/SEA documents are large and technical, the public find it difficult to get excited about the planning process, and marginalised groups are particularly hard to get involved. The SA/SEA documentation does not often list the resulting comments or how they have been taken into account. Statutory consultees, instead, seem to get involved much better, possibly because they understand the planning and SA/SEA processes and their importance. Their views also seem to be taken on board more in the plan, possibly because they have a more formal role in the plan-making as well as the SA/SEA process. Again, this is consistent with the previous literature.

It is in the transactive effectiveness dimension that there have probably been the most changes. The length of SA/SEA reports was already being decried almost ten years ago (CLG Citation2010), and this does not seem to have improved. The cost of SA/SEAs does not seem to have risen much—the CLG (Citation2010) report cites a range of £25,000–60,000, which is very similar to the costs quoted at . However, between 2010/11 and 2017/18, government funding for local authorities fell by 49%, and local authority Footnote1spending on planning and development fell by 53% in real terms (NAO Citation2018). At the same time, plans were legally challenged multiple times on grounds of their SA/SEA, both successfully and unsuccessfullyFootnote2. The successful challenges resulted in plans, or parts of plans, being quashed. Planners have become more aware of the risks of not carrying out a legally-compliant SA/SEA. They have thus had to prioritise the SA/SEA process—and keep producing over-long SA/SEA reports—at a time when their resources have been slashed.

Possibly because of this there has been a noticeable shift towards having the SA/SEA carried out by consultants rather than in-house. SA/SEA is a relatively self-contained process that can easily be passed to consultants. Consultants can help to ensure the legal robustness of the SA/SEA, and can called on to defend the SA/SEA at public inquiry. In 2005, just over half of local authorities were carrying out SA/SEAs in-house, and only 19% had delegated the work completely to consultants (Therivel and Walsh Citation2005). Instead, for the 15 SA/SEAs reviewed for this study, two-thirds were carried out solely by consultants, four (27%) were carried out in-house, and one was prepared jointly.

However, neither the halving of resources nor the externalization of SA/SEA to consultants seems to have significantly affected the other dimensions of SA/SEA effectiveness: in other words, both consultants and planners seem to have become adept at doing more with less. Consultants are now having to cope with better public ‘enforcement’ of the legal SA/SEA requirements, and with more risk-averse planners, on roughly the same budgets. Planners are having to prepare plans and their SA/SEAs on roughly half the previous budget.

This is not to say that the situation is sustainable. The current situation for planners has been described as being the worst in decades and ‘in crisis’ (The Planner, Citation2016, Citation2018), with planners facing negative press, ongoing changes in legislation, and reductions in their powers as well as dwindling resources (Planning Resource Citation2016). Another victim of this pressure has been SA/SEA research. Whereas response rates to surveys of local authorities in 1994–2001 ranged between 46% and 68% (Therivel and Minas Citation2002), Ezzet (Citation2016) struggled to get a 15% response rate despite reminder emails and phone calls. For this research, only one in four planners (25%) responded to a request for an interview.

Interestingly, the suggestions most frequently made for improving SA/SEA effectiveness related to the context within which SA/SEAs are carried out: there should be less political interference, politicians and planners should better understand the value of SA/SEA, capable individuals should carry out the SA/SEA, and the SA/SEA should be started early and be integrated with the plan-making process. This could be a combination of longing for the good old pre-austerity days, and cynicism about the government’s and local politicians’ expectations of planners.

9. Conclusions

England has had, by now, 14 years of SA/SEA practice. SA/SEA of English Local Plans continues to be broadly substantively effective in that it leads to plan changes. However, it seems unable to truly achieve sustainable development, nor to actively involve the public. Arguably the largest change in effectiveness in the last eight years has been a significant increase in transactive effectiveness: doing more with less. And despite the pressures that planners and consultants operate under, the questionnaires and interviews suggest that they still think that the benefits of SA/SEA (marginally) outweigh its costs. SA/SEAs seem to be perceived as a good way of ensuring the robustness as well as the sustainability of a plan; of ‘telling the story’ of a plan for consultation purposes; and of helping to protect the plan from future critique by planning inspectors or from legal challenge.

Of course, all of England’s SEA/SA processes may be blown sky-high with Brexit. But for now, in the calm before the storm, overall SA/SEA in England continues to be at least partly effective.

[ODPM] Office of the Deputy Prime Minister), Scottish Executive, Welsh Assembly Government, Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland. 2005. A practical guide to the strategic environmental assessment directive. London:ODPM.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all the interviewees and questionnaire respondents, and the two reviewers of this article.

Notes

1. One closed question questionnaire (n=7) and an open question questionnaire (n=4).

2. St Albans City & District Council v. Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government [2009] EWHC 1280 (Admin), www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2009/1280.html; Save Historic Newmarket, [2011] EWHC 606 (Admin), www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2011/606.html/; Heard v. Broadland District Council and others (‘Greater Norwich’), [2012] EWHC 344 (Admin), http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2012/344.html.

References

- Adur District Council. 2017. Adur local plan 2017. sustainability appraisal post-adoption statement; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.adur-worthing.gov.uk/media/media,147020,en.pdf.

- Bond AJ, Fundingsland M, Tromans S. 2016. Environmental impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment in the UK after leaving the European Union. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 34(3):271–274.

- [CLG] Communities and Local Government. 2010. Towards a more efficient and effective use of strategic environmental assessment and sustainability in spatial planning: summary. London:CLG.

- Coventry City Council. 2016. Sustainability appraisal/strategic environmental assessment: coventry local plan: proposed submission. Coventry:Coventry City Council.

- Curran JM, Wood JM, Hilton M. 1998. Environmental appraisal of UK development plans: current practice and future directions. Environ Planning B. 25:411–433.

- Defra. 2011. Biodiversity 2020: a strategy for England’s wildlife and ecosystem services; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69446/pb13583-biodiversity-strategy-2020-111111.pdf.

- Derbyshire Dales District Council. 2016. Derbyshire dales local plan – Draft plan sustainability appraisal report; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.derbyshiredales.gov.uk/images/documents/L/Local%20Plan%20Examination%20Library/SD04%20SA%20Report%20Submission%20December%202016.pdf.

- [DoE] Department of Environment. 1993. Environmental appraisal of development plans: A good practice guide. London:Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Ezzet O. 2016. The costs & benefits of strategic environmental assessment in local planning [MSc dissertation]. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University.

- Fischer TB. 2010. Reviewing the quality of strategic environmental assessment reports for English spatial plan core strategies. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:62–69.

- Fischer TB, Glasson J, Jha-Thakur U, Therivel R, Howard R, Fothergill J, Sykes O. 2018. Implications for Brexit for environmental assessment in the United Kingdom – results from a 1-day workshop at the University of Liverpool. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 36(4):371–377.

- Fischer TB, Onyango V. 2012. Strategic environmental assessment-related research project and journal articles: an overview of the past 20 years. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 30(4):253–263.

- Fischer TB, Yu X. 2018. Sustainability appraisal in neighbourhood planning in England. J Environ Planning Mgmt.

- Gov.uk. 2018. Local plans progress – 30 June 2018; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/724369/LPA_Strategic_Plan_Progress_-_30_June_2018.GOV.UK.pdf.

- Harari D. 2018. Regional and local economic growth statistics. Briefing Paper no. 05795. London: House of Commons Library.

- Hartlepool Borough Council. 2017. Local plan sustainability appraisal addendum; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.hartlepool.gov.uk/downloads/file/4442/sustainabililty_appraisal_addendum_-_july_2017.

- HM Government. 2018. A green future: our 25 year plan to improve the environment; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693158/25-year-environment-plan.pdf.

- House of Commons. 2018. Water quality. Briefing paper CBP 7246; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7246/CBP-7246.pdf.

- Hull City Council. 2016. Hull local plan public consultation document sustainability appraisal report; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. http://hullcc-consult.limehouse.co.uk/file/4334352.

- [LB] London Borough of Redbridge. 2016a. Sustainability appraisal (SA) of the Redbridge local plan; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.redbridge.gov.uk/media/3037/lbr-111-redbridge-local-plan-sa-report-july-2016.pdf.

- [LGA] Local Government Assocation. 2018. Local services face further £1.3 billion government funding cut in 2019/20; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.local.gov.uk/about/news/local-services-face-further-ps13-billion-government-funding-cut-201920.

- Lichfields. 2017. Planned and deliver: local plan-making under the NPPF: a five-year progress report; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. https://lichfields.uk/media/3000/cl15281-local-plans-review-insight_mar-2017_screen.pdf.

- [LPEG] Local Plans Expert Group. 2016. Local plans: report to the communities secretary and to the minister of housing and planning; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/508345/Local-plans-report-to-governement.pdf.

- [NAO] National Audit Office. 2018. Financial sustainability of local authorities; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.nao.org.uk/press-release/financial-sustainability-of-local-authorities-2018/.

- PAS. 2008. Local development frameworks: options generation and appraisal. London:PAS.

- [PAS] Planning Advisory Service. 2006. LDF learning and dissermination project: making sustainability appraisal manageable and influential. London: PAS.

- The Planner. 2018. Local authority planning needs everyone’s support; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.theplanner.co.uk/opinion/local-authority-planning-needs-everyones-support.

- Planner T. 2016. Planning under pressure; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.theplanner.co.uk/features/planning-under-pressure-0.

- Planning Resource. 2016. The 2016 careers and salary survey; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1414271/2016-careers-salary-survey.

- Redbridge LB. 2016b. Redbridge local plan regulation 19 representations; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.redbridge.gov.uk/media/3313/lbr-1011-redbridge-local-plan-reg-19-representations.pdf.

- [RTPI] Royal Town Planning Institute. 2018. Strategic environmental assessment. Improving the effectiveness and efficiency of SEA/SA for land use plans; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.rtpi.org.uk/knowledge/practice/sea/.

- Sherston T. 2008. The effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment as a helpful development plan making tool [MSc dissertation]. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University.

- Short M, Jones C, Carter C, Baker M, Wood C. 2004. Current practice in the strategic environmental assessment of development plans in England. Reg Stud. 38:177–190.

- Slootweg R, Jones M. 2011. Resilience thinking improves SEA: a discussion paper. Impact Ass Project Appraisal. 29(4):263–276.

- Smith S, Fessey M, White A. 2011. Generating reasonable alternatives: lessons from UK spatial planning practice. Prague: International Association for Impact Assessment conference.

- Sutton LB. 2016. Sustainability appraisal of draft local plan 2016–2031: proposed submission consultation (regulation 19); [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/0B5l397zoXtVQaGp6NFVfdF9UVjQ.

- Telford & Wrekin Council. 2016. Telford & Wrekin local plan submission version integrated appraisal; [accessed 2019 Feb 16]. www.telford.gov.uk/download/downloads/id/4362/a3_twlp_integrated_appraisal_-_submission_version.pdf.

- Therivel R. 1995. Environmental appraisal of development plans: current status. Plan Pract Res. 10(2):223–234.

- Therivel R. 1998. Strategic environmental assessment of development plans in Great Britain. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 18:39–57.

- Therivel R. 2013. Use of sustainability appraisal by English inspectors and judges. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 38:26–34.

- Therivel R, Christian G, Craig C, Grinham R, Mackins D, Smith J, Sneller T, Turner R, Walker D, Yamane M. 2009. Sustainability-focused impact assessment: English experiences. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):155–168.

- Therivel R, Minas P. 2002. Measuring SEA effectiveness: ensuring effective sustainability appraisal. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 20:81–91.

- Therivel R, Walsh F. 2005. The strategic environmental assessment directive in the UK: 1 year onwards. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26:663–675.