ABSTRACT

This paper investigates whether the Thai impact assessment (IA) system should develop through revolution or evolution. A timeline of the Thai IA system is mapped to show its development to date. Aspects of effectiveness (i.e. procedural, substantive, transactive, and legitimacy) are then used as the benchmark against which to evaluate past IA practice in terms of strengths, limitations and challenges. IA practice is analysed both in terms of the people within the IA system and the IA system itself, as both are considered key elements in making IA work. The findings suggest that the ongoing evolution of the IA system has continued to improve its procedural, substantive and transactive effectiveness; therefore, suggesting that continuing evolution is sufficient to deliver these dimensions of effectiveness. However, the findings also indicate that it is the people in the IA system that influence practice and arbitrate legitimacy. Developing the system over time has not significantly improved legitimacy, leading to the conclusion that gaining legitimacy in the IA process might need some elements of revolution.

1. Introduction

When addressing whether an impact assessment (IA) system should develop through revolution or evolution (based on the theme of the IAIA19 conference and this IAPA special issue), it is worthwhile considering how these terms are understood. The IAIA19 conference theme highlighted that IA was initially restricted to project-level ‘environmental impact assessment (EIA)’ prior to evolving into various forms, e.g. strategic environmental assessment (SEA), social impact assessment (SIA), health impact assessment (HIA), and sustainability assessment (SA). Banhalmi-Zakar et al. (Citation2018) explained that ‘evolution involves iterative processes of practicing, reflecting and changing practices to adapt to new situations and conditions’ (p. 5); and highlighted that ‘a revolutionary approach seeks to turn current thinking of IA ‘on its head’ through a complete overhaul of IA’s processes as well as its aims’ (p.6). Based on this explanation, in this paper, we regard IA evolution as including expansion into different components (like social and health), and also the addition of regulatory detail to develop capacity. Revolution, on the other hand, is something more radical which does not already exist as common practice elsewhere. This suggests that the decision on whether to pursue evolution or revolution for IA practice should be carefully made and, in doing so, two simple elements are key: the IA system; and the people within the IA system.

Wood (Citation2003) highlighted that each ‘EIA system is unique and each is the product of a particular set of legal, administrative and political circumstances …’ (p. 13). IA systems are supposed to make decision-makers more aware of environmental changes and consequences which may arise from proposed actions (Glasson and Therivel Citation2019). Whilst in practice IA has been criticised for having limited influence on decision-making, it has been argued that once mitigation measures are implemented, the quality and outcomes of decisions are likely to be improved as a result (Jay et al. Citation2007). This clearly indicates that the effectiveness of the IA system is driven by the people within the system, and that the context can influence the outcomes of relevant actions. The people who get involved in development planning and IA processes, i.e. stakeholders, can be project developers, affected parties, regulators, and facilitators (consultants) (Glasson and Therivel Citation2019, p. 68). The key factors controlling the effectiveness of the IA system through these stakeholders’ actions could include political will, authority competence, and stakeholders’ awareness and their voice (Wood Citation2003; Arts et al. Citation2012; van Doren et al. Citation2013; Lyhne et al. Citation2017).

In considering how best to develop IA systems into the future, the specific challenges being faced in the 21st century must be taken into consideration at all levels, from strategic to local scale. Retief et al. (Citation2016) investigated global megatrends in a changing world and synthesised six categories, i.e., ‘i) demographics, ii) urbanisation, iii) technological innovation, iv) power shifts, v) resource scarcity and vi) climate change’ (p. 52). Thailand also faces these challenges. For example, environmental issues such as climate change (i.e. floods, increasing temperatures, rising sea level), water resource management, water pollution, air quality control, resource depletion, and increasing waste generation (Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP) Citation2015a, Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) Citation2014). However, challenges that IA practitioners tend to face through the advent of these megatrends are identified as ‘i) complexity and uncertainty, ii) efficiency, iii) significance, and iv) communication and participation’ (Retief et al. Citation2016, p. 52); such that appropriately evolved IA methods and expected outcomes, which fit with the rapid changes are required.

Bond and Pope (Citation2012) highlighted that ‘ … evolving considerations of effectiveness matter for the practice of impact assessment, as legislation and guidance evolve based on research which is framed based on considerations of effectiveness’ (p.2). As such, assessing the effectiveness of IA can reflect a deeper understanding of how IAs are taken into account, understood, conducted, and implemented. This could help in investigating what changes or actions are required to make IA work today and in the future.

The aim of this paper is to answer the questions raised by the call for the IAPA special issue on ‘Evolution or Revolution: Where next for impact assessment?’ In doing so, Thailand is used as a case study, charting the development of IA starting from the adoption of EIA for project development in the country (which we can consider to be a revolution in establishing IA), through the evolution of IA practice in the country over the past four decades. It is timely to reflect on the direction of IA in the country and, through the exploration of effectiveness as a benchmarking tool, to identify changes which need to be pursued into the future. As such, this paper addresses the history of IA in the Thai context to map the evolution and/or revolution to date, thereby allowing a reflection of which has delivered an approach to IA that is effective, or whether further evolution and/or revolution is needed to deliver an effective system into the future.

2. Methodology

This research was conducted using a qualitative approach involving a literature review, encompassing reviews of legislation, guidance documents, Government reports and past evaluations (related to IA practice in Thailand, which have been published as presented in , (for example, Baird and Frankel Citation2015; Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015)). The past evaluations encompass data collections based on documentary analysis for measuring SEA effectiveness (Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019) and documentary analysis coupled with stakeholder interviews for investigating the effectiveness of HIA and environmental and health impact assessment (EHIA) (Chanchitpricha Citation2012; Fakkum Citation2013; Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018).

Table 1. Legislative regulations, relevant guidelines and evaluation of IA practice in Thailand.

In order to reflect on past practice, in this paper, we examined the effectiveness of Thai IA practice based on the recent conceptualisations of effectiveness (Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019), associated with a timeline of the evolution of Thai practice.

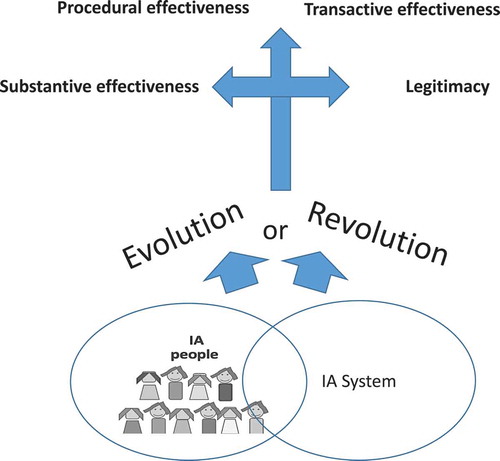

Aspects of effectiveness applied to the investigation are delineated from the international study of the effectiveness of environmental assessment (Sadler Citation1996), which identified procedural, substantive, and transactive dimensions of effectiveness. This conceptualisation of effectiveness was refined by Pope et al. (Citation2018) and Chanchitpricha et al. (Citation2019) to include ‘legitimacy’ as a fourth dimension comprising sub-criteria focusing on organisational and knowledge legitimacy (Bond et al. Citation2016; Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019). These aspects of IA effectiveness are all related to the IA system and the people within the context where IA practice is implemented as demonstrated in .

Table 2. The aspects of effectiveness and their components.

The concept of this investigation is presented in in terms of how the aspects of IA effectiveness can help to reflect the two key elements; people within the IA system and the IA system itself involved with IA practice. Desirable or undesirable outcomes gained from IA practice, based on the effectiveness criteria, could help to identify strengths, limitations, and challenges such that the desired changes can be highlighted.

To justify whether (and how) the IA practice is effective or not, we investigated overall performance of IAs as applied in the Thai context to date (i.e. mandatory EIA, mandatory EHIA, non-mandatory HIA, and non-mandatory SEA). We did this by deciding whether the IA practice as a whole achieved each criterion using the following assessment approach: ‘Yes’ means that it did fully achieve the effectiveness criterion; ‘Partially’ achieved means that it partially achieved the effectiveness criterion; and ‘No’ means that it did not achieve the effectiveness criterion. A question mark, ‘?’, means that there is not enough evidence to justify whether the effectiveness criterion is met. This duplicates the approach adopted in our recent work (Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019 based on Wood (Citation2003) and Theophilou et al. (Citation2012)).

3. History of the impact assessment (IA) system in Thailand

The first experience of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) practice in Thailand was gained by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) on a discretionary basis in 1972, for the development of the Srinagarind Dam project (Shepherd and Ortolano Citation1997; Swangjang Citation2018). It was a revolution in terms of its application to project development at the time. It was observed that ‘mutually reinforcing support for EIA from both internal and external development agency, political entrepreneurship by agency staff that are concerned about the environment, and the transformation of power relationships within the agency by environmental professionals’ were the key to the institutionalisation of EIA in EGAT (Shepherd and Ortolano Citation1997, p. 354). IA practice has subsequently evolved since that initial revolution.

The evolution of the IA system in Thailand can be outlined based on three main aspects: mandatory requirement for EIAs and Environmental and Health Impact Assessment (EHIA); the development of other forms of IA to support public participation within EIA (i.e. social impact assessment (SIA) (ONEP Citation2006), and health impact assessment (HIA); and the development of SEA on a discretionary basis (Office of the Prime Minister Citation2018) (see ).

Table 3. Evolution of impact assessments in Thailand.

EIA was initially introduced as a statutory process in Thailand in 1975 when the National Environment Board (NEB) was authorised to provide justification and comments on project development which may cause adverse environmental impacts (according to the first enactment of the Enhancement and Conservation of National Quality Act (NEQA) B.E.2518); the statutory requirement for EIA was subsequently increased to 35 project-types (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2012), and then to 36 project-types in 2015 (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2015b); however, later on this ministerial notification was annulled in November 2015 such that 35 project-types would require EIA (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2015c). By 2007, the significance of health impacts associated with project development became clear and was included in section 67 of the Thai constitution B.E.2550, and the National Health Act B.E.2550. This led to the requirement for environmental and health impact assessment (EHIA) to be conducted for 11 project-types (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2010), and was then increased to 12 project-types in 2015 by transferring one of the project-types requiring EIA to the list of project-types requiring EHIA (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2015a, Citation2015c).

NEQA was revised in 1992 (B.E.2535) to improve the Act, which included assigning three key authorities to oversee the national environmental policy, planning, protection and management; as well as to promote public participation in resolving environmental problems (i.e. Office of Natural resources and Environmental Policy and planning (ONEP), Pollution Control Department (PCD), and Department of Environmental Quality Promotion (DEQP)). More recently, in connection with the changing political context within the country, the new Thai Constitution was enacted through B.E. 2560 based on the outcome of a national referendum (Thai Constitution Citation2017). The NEQA was subsequently revised (to deliver NEQA (no. 2) B.E.2561 which came into force in 2018), whereby the whole EIA legislative content as appeared in the former version of the Act (chapter 4: environmental impact assessment) was restructured and replaced with new content. This included provisions on, for example: fines and punishment measures; a shorter time-frame for the IA process; an open track for SEA to be taken into account (where SEA might need to be conducted under future laws or regulations) (ONEP Citation2018). However, at the time of writing this paper, no SEA regulation has been adopted (Prince of Songkla University Citation2018; Yusook Citation2018). Based on the NEQA (no.2), relevant ministerial notifications have been revised so that the newly adopted ministerial notifications led to the termination of 11 former EIA-related ministerial notifications (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2019a), and a further 5 EHIA-related ministerial notifications were repealed (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Citation2019b). Therefore, at the time of writing, regarding the amendment of details within the former old ministerial notifications, 35 project types are subject to EIA and 12 subject to EHIA. The Act also requires that public participation in the IA process has to follow the ONEP guideline as attached in the regulation (Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP) Citation2019). Although this sounds like a revolution, we consider it to represent IA evolution as it primarily represents expansion into (or retraction from) different components, and also the addition of regulatory detail to develop capacity. We note that changes to legislation are a frequent occurrence in Thailand, responding to different political contexts including, for example, changing governments, and changing situations in the country (for example, Thai Constitution Citation2007, Citation2017; The Prime Minister Citation2018).

Thus, it is clear that IA legislation, and the political context, are the key driving forces influencing IA implementation, any kind of changes in IA practice and its evolution in the Thai context (Chanchitpricha Citation2012; Sandang and Poboon Citation2018).

4. Reflections on the IA system effectiveness based on the findings from past evaluations

The overall picture of IA effectiveness in Thailand is based on the findings of previous studies by the authors (Chanchitpricha Citation2012; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018; Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019), as well as other relevant IA system evaluations (Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015; Swangjang Citation2018). presents the IA effectiveness framework along with the strengths and limitations of practice. The IAs considered encompass mandatory EIA, mandatory EHIA, non-mandatory HIA, and non-mandatory SEA, in the Thai context. It is clearly suggested that non-mandatory IAs tend to have less evidence supporting their capacity in achieving substantive effectiveness and legitimacy. This implies that IA legislation could be a key to improving the substantive effectiveness and legitimacy of practice. These tallies with Biermann and Gupta (Citation2011) who argued that ‘legal norms and requirements’ are the key to delivering the ‘quality of being legitimate’ (p. 2858).

Table 4. Overall picture of IA effectiveness in the Thai context (according to the current findings of effectiveness assessment).

For mandatory EIA and EHIA, reflects an IA system that is partially or fully effective considering all four dimensions of effectiveness (procedural, substantive, transactive, and legitimacy – except knowledge spectrum).

4.1. Procedural effectiveness

The findings suggest that procedural effectiveness is delivered through the provision of EIA/EHIA legislation providing a framework for: project screening; EIA/EHIA procedures; the IA review process and subsequent approval; broad guidelines for the scope of assessments; environmental quality standards; methodologies as technical guidelines; an impact mitigation framework; and monitoring plan (The Prime Minister Citation1992; ONEP Citation2013). Theoretically, this allows relevant institutional roles to be identified and should lead to collaboration amongst them. Zhang et al. (Citation2013) highlighted that ‘mandatory requirement with predefined role and responsibility’ (p. 155) is one of the factors that directly influences the effectiveness of IA. However, it appears that mandatory IA practice in Thailand (i.e. EIA & EHIA) as investigated in this paper meets the procedural effectiveness criteria only partially. This is because insufficient attempts are made by project proponents to create collaborations between different groups of IA people (Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015). In addition, it was highlighted that guidelines on IA practice and public participation in the IA process should be clear and appropriate to apply in real practice (e.g. Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018). Montaño and Fischer (Citation2019) argued that the ‘institutional and normative context’ can’t be overlooked in providing up-to-date guidance for SEA/IA practice to help improve its effectiveness.

For non-mandatory SEA, although broad guidance on SEA (ONEP Citation2009) has been provided in Thailand, it is noted that guidance in the absence of a ‘tradition of compliance’ is unlikely to support and ensure effective outcomes within SEA practice (Montaño and Fischer, Citation2019). As such, as presented in , the lack of a legal requirement to implement SEA in Thailand is considered a barrier in promoting the SEA outcomes and its effectiveness.

In terms of public participation in the IA process, for Thai EIA and EHIA practice, this has to be arranged as required by regulations, and the IA findings have to be communicated to involved stakeholders (ONEP Citation2006; Public Service Centre: Office of the Permanent Secretary Citation2009). Nevertheless, some stakeholders reflected that there are challenges associated with closing the gap between practice and the intended outcomes based on legislation (based on stakeholder interviews as conducted by Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015). For example, effective public participation practice may require more time than is specified in legal regulations (Phromlah Citation2018). It was underlined that public participation guidelines as suggested via the IA legislation was considered as the minimum requirement, as such, IA practitioners should prioritise ‘social context’ as a key to identify stakeholders in real practice (Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018). These findings lead to the reflection that impact assessment in Thailand has not yet achieved procedural effectiveness fully (see ).

In addition, concerning EIA practice, Wangwongwattana et al. (Citation2015) noted that, in comparison to the international standards as established through the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Performance Standards (PS) (International Finance Corporation (IFC) Citation2012), the ‘climate change mitigation and adaptation’ issue has not yet been clearly included in Thailand’s impact assessment system. Swangjang (Citation2018) also highlighted that the integration of ecosystem service (ES) within the EIA system has been limited. This is a future challenge when considering the development of IA knowledge and practice in a context where the issues of ‘resource scarcity’ and ‘climate change’ have become a global megatrend (Retief et al. Citation2016). Kim and Wolf (Citation2014) emphasise that a ‘sustainable future’ can be promoted by enhancing IA practice’. As such, it is essential to consider climate change mitigation and adaptation as part of IA practice.

4.2. Substantive effectiveness

Mandatory IAs tend to be partially or fully substantively effective, highlighting the level of achievement of IA practice in relation to the substantive effectiveness sub-criteria (i.e. incorporation of proposed changes, informed decision-making, close collaborations, parallel development, early start, and institutional & other benefits). Non-mandatory HIA did not fully achieve substantive effectiveness as decision-makers did not officially get involved, or informed about the process (Chanchitpricha Citation2012). This suggests the influence of legislation on the roles and actions of governmental authorities and regulators is important for IA practice in the Thai context. Although Morrison-Saunders and Bailey (Citation2009) considered that ‘individual activities of regulators can make a difference to the implementation of policy and processes such as EIA’ (p. 285), the regulatory framework and legislation are the key guide for the activities of governmental authorities and regulators in the Thai context (Chanchitpricha Citation2012; Sandang and Poboon Citation2018). Non-mandatory SEA tends to be partially effective based on the substantive effectiveness sub-criteria, e.g., informed decision-making, close collaboration, parallel development, early start and institutional and other benefits (also see strengths and limitations in ). According to Chanchitpricha et al. (Citation2019), although they are non-mandatory, the SEAs that have been conducted were sponsored by government authorities (or relevant regulators) (i.e. 12 SEAs out of 14). However, there is no clear evidence to demonstrate fully that findings from the SEAs conducted were taken into account (Wirutskulshai et al. Citation2011; Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019).

As such, effectiveness in this regard is likely to depend on the existence of a regulatory framework for implementing IA in the decision-making process (Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018), and the lack of effectiveness for discretionary IA procedures demonstrates the importance of legislation (Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019).

4.3. Transactive effectiveness

Transactive effectiveness reflects the extent to which IA processes are worthwhile, and the findings show that they are partially effective in terms of cost, time, skills and allocated roles. In terms of skills and allocated roles in IA practice, project proponents rely on hiring licensed consultants to undertake IA work, e.g., for scoping, impact assessment, public participation, and monitoring. Nevertheless, referring to the reviewed cases, the mandatory IAs (EIA, EHIA) and non-mandatory IAs (HIA, SEA), as conducted by the professionals in this field are considered to meet this criterion partially (Chanchitpricha Citation2012; Wangwongwattana et al. Citation2015; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018; Chanchitpricha et al. Citation2019). On the other hand, the availability of human resources is clearly lacking, for example, each ONEP expert deals (on average) with 13–20 EIAs per year (). However, not all of the staff are qualified and have expertise in considering the submitted EIAs. This is supported by Fakkum (Citation2013) who found that the overload of responsibilities on staff members affected the efficiency of the EIA approval and monitoring process; and there is a lack of health experts working under ONEP available to check submitted EHIAs prior to assigning to ONEP IA expert panels. Tools or methods, tailored for a particular IA context, are a crucial resource in assisting IA practitioners to deliver effective IA practice (Zhang et al. Citation2013). Therefore, research is required to create or to adapt suitable tools or methods compatible with the IA system and the people working within the system.

Table 5. Number of ONEP human resource available and EIA reports as submitted to ONEP during 2011–2014.

4.4. Legitimacy

Concerning the legitimacy aspect (the extent to which the IA process delivers outcomes which stakeholders consider to be fair, and which delivers acceptable outcomes)(see ), mandatory IAs (EIA and EHIA) tend to partially meet legitimacy expectations. The findings suggest that the mandatory IAs partially achieve institutional legitimacy (openness, transparency & equity, distribution of powers and responsibilities regarding IA practice) and some elements of knowledge legitimacy (i.e. accuracy, integration, and diffusion). Institutional and knowledge legitimacy can be perceived through the outcomes of mandatory EIA and EHIA because the involvement of stakeholders was evident in the IA practice, and information related to approved mandatory EIA can be accessed via an online database (i.e. Smart EIA 4 Thai – URL: http://eia.onep.go.th/index.php) and mobile application (i.e. Smart EIA), as provided by ONEP. For mandatory EHIA, the reports as approved by ONEP’s expert panels can be accessed via the websites of the regulator or project developers (Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2018), however, not for the full range of the EHIAs. These attempts as provided by key actors and authorities are expected to ensure that the IA practice is disclosed to the public, and could cast light on openness, transparency, and equity within the IA process as well as knowledge diffusion of the IA findings to some extent.

In terms of balanced powers among relevant authorities, the legislation (NEQA B.E. 2535 as enforced when the reviewed IAs in this paper were conducted) is considered as a guide for authorised ministries and institutions to operate and balance their powers in the Thai context. Nevertheless, at a local level where IAs are conducted, further investigation is required to justify legitimacy. Derakhshan et al. (Citation2019) noted that the perception of ‘high power for government authorities’ (p.84) could make local individuals suppress their opposed views or dissatisfactions. This could be an example reflecting the links to power and legitimacy, as highlighted by Cashmore and Richardson (Citation2013): ‘… power cannot be somehow removed from EA policy or practices. There is no possibility of creating power-free EA processes, where issues of power are handled in formal political processes’. As such, this suggests that the way to deal with the ‘power distribution issue’ in IA practice is to ensure that the power is balanced among relevant stakeholders equitably.

Meanwhile, there is no evidence to suggest that formal and informal knowledge is integrated into the IA process, meaning that they fail to achieve legitimacy in terms of the knowledge spectrum. This omission has continued over a number of decades of practice, which leads us to suggest that some radical change is needed to address this legitimacy failing.

For non-mandatory IAs (HIA and SEAs), it is unclear whether legitimacy based on the distribution of power in the IA system, and knowledge integration are achieved. It appears that voluntary HIA, as conducted by researchers and community members, e.g., the Potash mining HIA case (Pengkam et al. Citation2006) has the potential to achieve the integration of both formal and informal knowledge in IA processes (knowledge spectrum). Also, the findings were accessible for the assessment (for example, as conducted by Chanchitpricha (Citation2012)) inferring partial achievement of the legitimacy criterion on knowledge diffusion. Considering non-mandatory SEA, the legitimacy seems to be unclear in terms of its outcomes in this context. However, it is noted that these conclusions are based on a limited number of studies having been conducted in terms of assessing the effectiveness of IAs in the Thai context so far.

As demonstrated in , the limitations and challenges to IA legitimacy encompass trust issues, which are related to openness, transparency and equity. The issues that can arise through the enforcement of the latest version of EIA regulations as revised in NEQA no.2 (B.E. 2561) include: a lack of trust in EIA findings; costs of IAs are typically not being disclosed; feedback by the EIA review expert panel not yet being widely disclosed to relevant actors; concerns and conflicts related to limiting rights of the affected people. In addition, ineffective communication in IA practice may lead to challenges in communicating knowledge, which is related to knowledge legitimacy in terms of knowledge integration and knowledge diffusion.

It is recognised that documentary analysis alone could not provide a clear conclusion on the level of legitimacy. Further investigation based on other approaches e.g. focus group and interviews of key informants involved with the IA process, can potentially deliver a deeper understanding of the legitimacy of IA practice.

5. What is next for IA practice?

Rapid global change (global megatrends) is a significant issue when considering how environmental practice (EA) should develop in the future (Retief et al. Citation2016). Thailand has demonstrated a clear determination that sustainable development, and dealing with the consequences of global change, e.g. climate change, should be integrated with the national strategic policy and plans (Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP) Citation2015b). While Thailand has submitted its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Official letter no. 1006.3/11812 as issued on 1 October 2015), in terms of reducing greenhouse gases, it is considered essential that climate change issues should be taken into account in the newly updated impact assessment process in the future.

It is clear that IA practices have been embedded as tools for decision-making towards sustainability in the Thai context. The limitations and challenges highlighted in , imply that both the people within the IA system and the IA system itself are the key elements in making IA practice serve society either for better or for worse. As such, building resilience to change at all levels needs to be taken into account. Hotimsky et al. (Citation2006) highlighted that enhancing institutional resilience could underpin the creation of ‘novel policies’ to deal with the chronic problems of resource scarcity. In addition, a deeper investigation of the resources invested in IA practice (transactive effectiveness) could help to improve the IA system as driven by appropriately skilled human resources. This could also help to improve the legitimacy of IA in terms of transparency and openness. In addition, in order to gain a higher level of legitimacy, effective communications in the IA process are required to mitigate trust and conflict issues. For example, Sinclair et al. (Citation2017) suggested that integrating effective e-governance and social media in IA processes could help to provide meaningful public participation, and this could help decision-makers to hear the public voice via modern technology.

This research indicates that the lessons learned and the experience gained throughout the evolution of IA in Thailand has improved its effectiveness. In order to ensure that IA has improved after each evolutionary step, it is crucial to assess the effectiveness of IA practice to benchmark practice. As such, the existing IA system, knowledge gained and capacity built to date should continue to evolve rather than undergo revolution. However, people in the IA system of a particular context influence practice. As such, gaining legitimacy in the IA process might need some elements of revolution. This could include building literacy and capacity of effective communication using digital media to prevent or mitigate conflicts which may arise from ineffective and/or misleading communication.

According to the findings of this paper, we would require more investigation on how to radically improve organisational legitimacy and knowledge legitimacy so that legitimacy is gained as part of the outcomes of IA practice.

References

- Arts J, Runhaar HAC, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, Van Laerhoven F, Driessen PPJ, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14:40.

- Baird M, Frankel R. 2015. Mekong EIA briefing: environmental impact assessment comparative analysis in lower Mekong couuntries. Washington, D.C.:PACT.

- Banhalmi-Zakar Z, Gronow C, Wilkinson L, Jenkins B, Pope J, Squires G, Witt K, Williams G, Womersley J. 2018. Evolution or revolution: where next for impact assessment? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 36:506–515.

- Biermann F, Gupta A. 2011. Accountability and legitimacy in earth system governance: A research framework. Ecological Economics. 70:1856–1864.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2016. A game theory perspective on environmental assessment: what games are played and what does this tell us about decision making rationality and Legitimacy? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 57:187–194.

- Bond A, Pope J. 2012. The state of the art of impact assessment in 2012. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 30:1–4.

- Cashmore M, Richardson T. 2013. Power and environmental assessment: introduction to the special issue. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 39:1–4.

- Chanchitpricha C 2012. Effectiveness of Health Impact Assessment (HIA) in Thailand: a case study of a Potash mine HIA in Udon Thani Norwich: University of East Anglia.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2018. Investigating the effectiveness of mandatory integration of health impact assessment within environmental impact assessment (EIA): a case study of Thailand. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 36:16–31.

- Chanchitpricha C, Morrison-Saunders A, Bond A. 2019. Investigating the effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment in Thailand. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 37:356–368. 10.1080/1461551720191595941.

- Derakhsham R, Mancini M, Turner JR. 2019. Community’s evaluation of organisational legitimacy: formation and reconsideration. Int J Project Manage. 37:73–86.

- Fakkum S. 2013. Environmental and health impact assessment system in Thailand [Independent study]. Bangkok, Thailand: National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA).

- Glasson J, Therivel R. 2019. Introduction to environmental impact assessment. 5th ed. London: Routledge.

- Hotimsky S, Cobb R, Bond A. 2006. Contracts or scripts? A critical review of the application of institutional theories to the study of environmental change. Ecol Soc, 11:41.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). 2012. IFC performance standards on environmental and social sustainability. Washington:IFC, World Bank Group.

- Jay S, Jones C, Slinn P, Wood C. 2007. Environmental impact assessment: retrospect and prospect. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27:287–300.

- Kim M, Wolf C. 2014. The impact assessment we want. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 32:19–20.

- Lyhne I, van Laerhoven F, Cashmore M, Runhaar H. 2017. Theorising EIA effectiveness: A contribution based on the Danish system. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 62:240–249.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2010. Notification of ministry of natural resources and environment Re: specification of project types, scales, and regulations for activities which may cause severe effects on health, environment and natural resources B.E.2553, 31 August 2010 (in Thai). In: Thai government gazette. Vol. 127. Special Part 104d. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 34–35. Repealed in January 2019.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2012. Natural resources and environment ministerial notification Re: specification of project types, scales, regulations and guidelines in the preparation of environmental impact assessment. In: Thai government gazette. Vol. 129. special part 97d. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 1–2. Repealed in January 2019.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2015a. Natural resources and environment ministerial notification Re: specification of project types, scales, and regulations which may cause severe effects on health, environment and natural resources B.E.2553 No.2. In: Thai government gazette. Vol. 132. Part 300d. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 5. Repealed in January 2019.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2015b. Natural resources and environment ministerial notification re: specification of project types, scales, regulations and guidelines in the preparation of environmental impact assessment No.6 (B.E.2557). In: Thai government gazette. Vol. 132. special part 11d Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 13. R epealed in November 2015.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2015c. Natural resources and environment ministerial notification re: specification of project types, scales, regulations and guidelines in the preparation of environmental impact assessment No.8 (B.E.2558). In: Thai government gazette. Vol. 132. special part 300d. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 6. Repealed in January 2019.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2019a. Ministerial notification of the ministry of natural resources and environment re: specifications of projects or actions which are subject to conduct environmental impact assessment (EIA); and principles, methods and requirement in the preparation of environmental impact statement (in Thai). In: Thai Government gazette no 136 special section 3d published on 4 January 2019. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 1–11.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2019b. Ministerial notification of the ministry of natural resources and environment re: specifications of projects or actions which may cause severe effects on environmental quality, health, and quality of life of affected people in community; and such projects or actions are subject to conduct Environmental and Health Impact Assessment (EHIA). In: Thai Government gazette no136 special section 3d; published on 4 January 2019. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 12–18.

- Montano M, Fischer TB. 2019. Towards a more effective approach to the development and maintenance of SEA guidance. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 37:97–106.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Bailey M. 2009. Appraising the role of relationship between regulators and consultants for effective EIA. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29:284–294.

- NESDB supports SEA concept & guideline (in Thai) Bangkok. [Online]. [Accessed 2018 October] http://www.nesdb.go.th/mobile_detail.php?cid=7&nid=6777

- Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP). 2007. Guideline for health impact assessment in EIA report in Thailand (in Thai). Bangkok:ONEP.

- Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP). 2013. Guideline for health impact assessment in EIA report in Thailand (in Thai). Bangkok: ONEP.

- Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP). 2015a. Climate change master plan B.E. 2558-2593 (in Thai). Bangkok: ONEP, MONRE.

- Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP). 2015b. Thailand’s intended national determined contribution. Bangkok. Thaland: ONEP.

- Office of Natural Resources and Environment Policy and Planning (ONEP). 2019. Notification of ONEP re: public participation guideline in the preparation process of environmental impact statement (in Thai). Thai Government gazett no 136 special section 36d. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 31.

- Office of the Prime Minister. 2018. Prime minister office notification re: the announcement of the national reform plan (in Thai). Thai Government gazette no 135 section 24a. Bangkok, Thailand: Cabinet and Royal Gazette Publishing Office (CGPO). p. 1–2, 1–469.

- ONEP. 2006. Guideline of public participation and social impact assessment in environmental impact assessment process (in Thai). Bangkok:ONEP.

- ONEP. 2009. Strategic enironmental assessment: SEA (in Thai): office of natural resources and environment policy and planning (ONEP).

- ONEP. 2018. How EIA is better in NEQA no.2 B.E.2561? (infographic sheet in Thai). Bangkok: ONEP [Online]. [Accessed 2019Apr].

- Pengkam S, Chaiyarak B, Jinwong A, Siriwatanapaiboon S, Kamkongsak L, Yothawichit S, Kamchiangta A. 2006. Health impact assessment of Potash mining project at Udon Thani province (Research Report in Thai). Nonthaburi, Thailand: Health Systems Research Institute.

- Phromlah W. 2018. Public participation: how can we make it work for the environmental impact assessment system in Thailand? Asia Pac J Environ Law. 21:126–146.

- Pope J, Bond A, Cameron C, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2018. Are current effectiveness criteria fit for purpose? Using a controversial strategic assessment as a test case. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 70:34–44.

- Prince of Songkla University. 2018. Sustainable development and environmental impact assessment. Faculty of Law. Bangkokbiznews. http://www.bangkokbiznews.com/blog/detail/644609.

- Public Service Centre: Office of the Permanent Secretary. 2009. Public participation guideline upon The regulation of the Prime Minister Office on public consultation B.E. 2548 (in Thai). Bangkok: The Secretariate of the Cabinet Printing Office.

- Retief F, Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, King N. 2016. Global megatrends and their implications for environmental assessment practice. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:52–60.

- Sadler B. 1996. International study of the effectiveness of environmental assessment. Final report. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

- Sandang C, Poboon C. 2018. Strategic environmental assessment in Thailand (in Thai). J Community Dev Res (Hum Social Sci). 11:90–100.

- Shepherd A, Ortolano L. 1997. Organizational change and environmental impact assessment at the electricity generating authority of Thailand: 1972-1988. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 17:329–356.

- Sinclair AJ, Peirson-Smith TJ, Boerchers M. 2017. Environmental assessments in the internet age: the role of e-governance and social media in creating platforms for meaningful participation. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 35:148–157.

- Swangjang K. 2018. Comparative review of EIA in the association of Southeast Asian Nations. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 72:33–42.

- Thai Constitution. 2007. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E.2550 (2007). No 124, Section 47; issued on 24th August 2007. – Repealed in 2014 (except Chapter 2 of the Constitution).

- Thai Constitution. 2017. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand B.E.2560 (2017). No 134, section 40a Thailand The Thai Government Gazette. p. 1–90.

- Thailand Board of Investment (BOI). 2014. Thailand board of investment guide on environmental regulations. Bangkok:BOI.

- The Prime Minister. 1992. The enhancement and conservation of national environmental quality act (NEQA) B.E.2535. Bangkok:Thailand.

- The Prime Minister. 2018. The enhancement and conservation of national environmental quality act (NEQA) (no.2) B.E. 2561. Thai Government gazette, no 135, special section 27a, published on 19 April 2018 Bangkok, Thailand.

- Theophilou V, Bond A, Cashmore M. 2012. Application of SEA Directive to EU structural funds: Perspectives on effectiveness. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 30:136–144.

- van Doren D, Driessen PPJ, Schijf B, Runhaar HAC. 2013. Evaluating the substantive effectiveness of SEA: towards a better understanding. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 38:120–130.

- Wangwongwattana S, Sano D, King PN. 2015. Assessing environmental impact assessment (EIA) in Thailand: implementation challenges and opportunities for sustainable development planning (working paper). Hayama, Japan: Institute of Global Environmental Strategies.

- Wirutskulshai U, Sajor E, Coowanitwong N. 2011. Importance of context in adoption and progress in application of strategic environmental assessment: experience of Thailand. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31:352–359.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: a comparative review. Edinburgh: Prentice Hall.

- World Bank. 2006. Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations and Strategic Environmental Assessment Requirements [Online]. Washington (DC): Environment and Social Development Department (East Asia and Pacific Region). [Accessed 2015]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/949001468167952773/pdf/408730PAPER0EI1onal1review01PUBLIC1.pdf.

- Yusook S 2018. Part 1: the roles of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) (in Thai). The seminar on SEA and water resource management in Thailand, 26 June 2018. Bangkok: The Berkeley Hotel. [Online]. http://wwwonepgoth/eia/กฎหมายที่เกี่ยวข้อง/sea/.

- Zhang J, Kornov L, Christensen P. 2013. Critical factors for EIA implementation: literature review and research options. J Environ Manage. 114:148–157.