ABSTRACT

EIA is increasingly being questioned as a decision-making instrument of choice for decision makers. In addressing these concerns, the paper aims to re-think the fundamentals of EIA through the identification of key assumptions underlying EIA evaluation. This aim was achieved through the application of the theory of change (ToC) method to the South African EIA system, which resulted in the identification of 19 key underlying assumptions. Going forward we recommend the testing of these assumptions towards a better understanding of the fundamental nature and purpose of EIA as a policy implementation instrument.

The importance of assumptions for evaluation

Over the past 50 years EIA systems have been globally adopted with almost all countries having some form of EIA (Morgan Citation2012; Yang Citation2019). However, in recent times there has been renewed questions being asked around whether EIA remains fit for purpose in a rapidly changing world (Retief et al. Citation2016). The most recent IAIA international conference theme entitled, ‘Evolution or revolution’, further reflects this urgent need for a critical evaluation of the fundamentals EIA, if it is going to remain the instrument of choice for decision makers into the future. A vast body of literature exists on EIA evaluation, conceptualised around different concepts such as quality, efficiency, effectiveness and efficacy, follow-up, cost, etc. (Sadler Citation1996; Cashmore et al. Citation2004; Retief Citation2010; Morgan Citation2012; Bond et al. Citation2018; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). All these evaluation studies have merit and contributed in their own way towards improving our understanding of different aspects of EIA. However, there seems to be scant reflection on the importance and role of assumptions in EIA evaluation. The aim of this paper is to rethink the fundamentals of EIA through the identification of key assumptions for evaluation. To this end, it is important to first explain the relevance of assumptions for evaluation by reflecting on the concepts of ‘critical thinking’ and ‘evaluative thinking’.

Critical thinking is defined as ‘The process of actively and skilfully conceptualising, applying, analysing, synthesising, and evaluating information to reach an answer or conclusion’ (Foundation for Critical Thinking Citation2019). To be adept and skilled in critical thinking, requires that we are able to take our thinking apart systematically, so as to analyse each part, and to assess it for validity (Paul and Elder Citation2002). Critical thinking is motivated by an attitude of inquisitiveness and belief in the value of evidence as basis for validity. It involves the following critical elements (also sometimes called the elements of logical reasoning), namely: identification of assumptions, posing of thoughtful questions, pursuing deeper understanding through reflection and perspective-taking. Although all these elements are important, the identification of assumptions is considered essential to test critical thinking because they represent those assumed truths that underpin the supposed logic or reasoning (Archibald et al. Citation2016). Various authors have made the explicit link between critical thinking and evaluation by simply applying these elements to evaluations, having termed it ‘evaluative thinking’ (see, for example, Schawnd Citation2015; Archibald et al. Citation2016). Simply put, evaluative thinking requires the elements of critical thinking (or logical reasoning). Within the context of EIA evaluation, it is important to distinguish between thinking evaluatively and doing an evaluation. These two concepts are not necessarily synonymous (Schawnd Citation2015). EIA evaluation could arguably be done without critical thinking and per definition evaluative thinking, commonly in the form of a mere tick the box conformance exercise. The authors support the pursuit of EIA evaluation through evaluative thinking. Evaluative thinking is motivated by an attitude of inquisitiveness and belief in the value of evidence. It involves the identification of assumptions, posing thoughtful questions, pursuing deeper understanding through reflection and perspective-taking, whilst making informed decisions in preparation for action (Archibald et al. Citation2016). This brings into sharp focus the importance of inter alia assumptions.

Unexamined and unjustified assumptions are the Achilles’ heel of critical thinking and evaluation (Archibald et al. Citation2016). Assumptions imbue evaluation, they can strengthen or pose a risk to its validity. The extent to which an assumption serves to strengthen or weaken validity depends on the extent to which it is explicated. Nkwake (Citation2013) provides a lucid understanding of the nature of underlying assumptions by reviewing the notion of assumptions in general and their role in the generation of knowledge. Recognising the limited research and literature relating to underlying assumptions of EIA, we refer to the roots of assumptions in scientific enquiry, highlighting the fact that assumptions have been and still are a vital part of the evolution of knowledge (Lucas Citation1975; McChesney Citation1986; Van der Sluijs Citation2017). The act of fact seeking, which is in essence the goal of science, proceeds on countless assumptions that always need to be verified (Hartse et al. Citation1984). These assumptions may also be presented as beliefs, belief systems, or theoretical paradigms, or they may not be articulated at all. If these assumptions are articulated, the pursuers of knowledge then gather evidence in light of these assumptions (Nkwake Citation2013). When people question their fundamental assumptions and beliefs, whether they are tacit or explicit, and evidence shows that an assumption or belief is faulty, a new theory or belief statement emerges, hence a paradigm shift.

The argument put forward in this paper, and which underlies the research aim, is that any EIA evaluation should apply evaluative thinking to determine and interrogate the underlying assumptions for the evaluation. We suspect this is rarely done in EIA evaluations. Ultimately, if the underlying assumptions are found to be wanting, then the beliefs on which the EIA system is based are faulty and in extreme cases, a paradigm shift is warranted. Such paradigm shifts would challenge foundational notions of the nature of EIA and what it should achieve. Although they may be perceived as negative, these paradigm shifts are integral to the development of knowledge. A failure to address flawed assumptions could thus result in the perpetuance of false beliefs and an ineffective EIA system. It is against this background that we continue in the following section by describing Theory of Change (ToC) as a preferred method to identify key assumptions for future application in EIA system evaluation. The ToC methodology is then applied to a selected case study country and key assumptions are identified. We conclude the paper with a call for further EIA system evaluation against these assumptions.

A preferred method for identifying key assumptions – Theory of Change (ToC)

In line with our research aim, we had to identify an evaluation method that relies fundamentally on the identification of assumptions and thereby supports evaluative thinking. Numerous EIA system review studies have been conducted over the years, especially within the European Union context (see, for example, Glasson Citation1999; Arts et al. Citation2012; Runhaar and Fischer Citation2012; Jha-Thakur and Fischer Citation2016; Jones and Fischer Citation2016; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). These studies mainly focussed on outcomes and used different conceptual dimensions of the concept of effectiveness (such as procedural, transactive, substantive, normative, etc.). The most common methods used include documentation analysis, surveys and interviews. Importantly, none of these studies applied methods that explicitly require the identification of assumptions as basis for the evaluation, and therefore were less applicable to our particular aim. However, various more general policy evaluation studies and methods exist which rely on the identification of assumptions, of which ToC is recognised as a best practice evaluation method (Weiss Citation1995; Jane Davidson Citation2004; Stein and Valters Citation2012). The concept of ToC was originally introduced in the field of evaluation in the 1990s. Recent years have seen a significant increase in the use of ToC, especially in the field of monitoring and evaluation of public policy and programme implementation (Mason and Barnes Citation2007; Rogers Citation2008; Brouselle and Champagne Citation2011; DPME Citation2011; McConnell Citation2019). Moreover, development programmes have also applied ToC, with many international agencies considering ToC as a best practice evaluation method (USAID Citation2015b). We could find no literature where ToC has been applied explicitly to EIA evaluation. However, Allen et al. (Citation2017) applied ToC to online decision support systems within the New Zealand agricultural and environmental management context. The aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of these decision support systems, which suggest some relevance to EIA as being a decision support instrument.

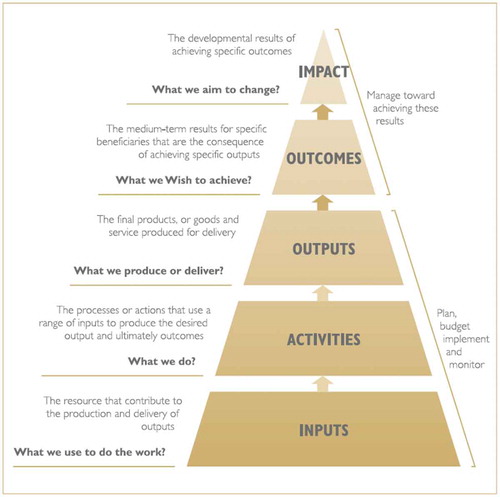

ToC needs to be understood as a process that relies on practitioner and stakeholder involvement in evaluation and reflection. Ultimately the ToC method produces a conceptual framework and a related causal narrative to guide evaluation. The causal narrative is explained and structured around a sequence of different so-called evaluation components, namely: inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts (Weiss Citation1995; Connell and Kubisch Citation1998; Thornton et al. Citation2017). In some instances, a design component is also included which deals with the contextual design of the policy or programme (DPME Citation2011). These components are typically illustrated and explained in the form of a pyramid, namely the ‘results based pyramid’ shown in . Applying the ToC method to EIA system evaluation would require adapting and contextualising the following generic questions, namely: what we use to do the work (inputs)? What we do (activities)? What we produce or deliver (output)? What we wish to achieve (outcome)? What we aim to change (impact)?

Figure 1. Results-based pyramid (DMPE, Citation2011).

In order to test the application of ToC to EIA system evaluation, we applied the method to a specifically selected country as described in the following section.

Applying ToC to identify key assumptions – South Africa as a case study

South Africa is considered an ideal country to test the application of ToC for two main reasons. Firstly, the country has a well-established EIA system with more than two decades of mandatory EIA practice. The EIA system is also well researched with a meaningful body of evaluation literature (see, for example, Sandham and Pretorius Citation2007; Sandham et.al. Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2010, Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Retief Citation2010; Hallat et al. Citation2015; Kidd et al. Citation2018; Swanepoel et al. Citation2019). Secondly, ToC is the method formally prescribed by the South African government for policy evaluation and monitoring (DPME Citation2011). The results presented here formed part of a formal EIA system review based on the ToC method. However, as a contribution to knowledge, this paper is only concerned with ToC as a means to identify key assumptions for evaluation. The testing of these assumptions will form part of future research and system evaluation as explained in the concluding section. In applying the ToC method to the South African EIA system the following five steps were followed:

Step 1 – South African Specialist Workshop: The initial version of the ToC conceptual framework and narrative was developed based on the outcome of a specialist workshop with five specifically identified specialist on EIA in South Africa. Between them, the specialists were all professional EIA practitioners with cumulative/combined EIA practice experience of more than 100 years. They were tasked to apply the results-based pyramid structure to the South African EIA system based purely on their professional opinion and experience.

Step 2 – Regulator workshop: The conceptual framework and narrative developed by the specialists were next presented to a regulator workshop for refinement and to obtain a regulator perspective. Invited to the regulator workshop were representatives from the 11 environmental authorities (nine provinces as well as the national Department of Environmental Affairs and the National Department of Mineral Resources) as well as the DPME.

Step 3: Stakeholder Workshops: The version developed by the specialists and agreed on by the regulators was next presented at a broader one-day stakeholder workshop. The stakeholder groups invited included a very broad range of representative civil society organisations, non-governmental organisations and environmental practitioners. The invitations were administered by the DPME and the invitees were identified by the 11 environmental regulators (9 provinces and the DEA and DMR), based on their experience and records of stakeholders actively involved in the EIA system. The aim of the workshop was to provide an opportunity for different stakeholders outside of government to also provide inputs. Ultimately two such workshops were held at different locations to ensure maximum opportunity to participate. The workshops were well attended with more than 50 representatives from diverse stakeholder groups.

Step 4: International Specialist Inputs: To ensure broader validity and to gauge international generalisability, workshops were held with international EIA specialists from four different countries in Central and Eastern Europe, namely Estonia, Sweden, United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The ToC conceptual framework and narrative were also presented at the IAIA international conference in 2018 and at a research working group in Australia in 2019. The later included representatives from Australia, Canada and Brazil. All comments were captured and the conceptual framework and narrative refined. We are therefore confident that the outcome is generalisable and has meaningful relevance beyond the South African context.

Step 5: Refinement and finalization: A final ToC specialist workshop was held to reflect on all comments received from the regulator workshop, stakeholder workshop as well as the international engagement. The ToC conceptual framework and narrative presented here was then refined and finalised based on the above inputs.

ToC results – key assumptions underpinning the South African EIA system

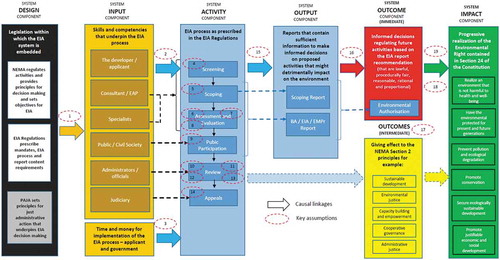

This section explains the ToC conceptual framework illustrated in as well as the causal narrative and related key assumptions. The content of the framework is the outcome of the steps set out above. In essence, the ToC framework is an exploded view of our understanding of how the EIA system in South Africa works. It addresses the causal logic between the design, inputs, activities, output, outcome and impact evaluation components from the ‘results based pyramid’ in . Ultimately it provides an illustration of the causal logic between different evaluation components (i.e. design, inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts) and underpins the ToC narrative and logical framework to be discussed in detail below.

The ToC narrative is framed against the different system components, i.e. design and inputs; activities and outputs as well as outcomes and impacts. The fundamentals of the South African EIA system turned out to be essentially similar to the generic international understanding of how EIA systems function (IAIA Citation1999; Wood Citation1999, Citation2003; Morgan Citation2012; Kidd et al. Citation2018). This was also confirmed during the international specialists’ workshops. We contend that the ToC narrative described in this paper is therefore not controversial or contentious but rather merely describes the agreed causal logic of how the EIA system in South Africa works, with a particular emphasis on the assumptions that underpin our understanding.

The ToC narrative in essence suggests the following causal logic statement: The South African EIA system is embedded in legislation (design component), relies on a certain level of skill and competence (input component) to administer and implement a process (activity component), that produces sufficient information captured in an EIA report (output component), to inform decision-making (outcome component), on the authorisation or refusal of future activities that might have a detrimental effect on the environment, towards progressively giving effect to the environmental right contained in Section 24 of the Constitution (impact component).

The following sections expand further on the above causal logic statement. The narrative of the causal logic reflected in should be read from left to right, starting with a discussion of the design and input components. The ‘key assumptions’ numbered 1 to 19 are indicated in and are explained in more detail in the following sections. We recommend to the reader to first read the following sections and then relate that back to . Moreover, to deal with the causal relationship between different components they are discussed sequentially.

Design and input components

Design and input components deal with the resources that contribute to the delivery of the activities and output component (Weiss Citation1995; Connell and Kubisch Citation1998; DMPE, Citation2011; Thornton et al. Citation2017). In this case, the design and input components relate to the design of and inputs to the South African EIA system as reflected and prescribed in EIA legislation as well as skill and competency requirements. Ultimately the system is embedded in legislation and implemented through certain skills and competencies. An understanding of the design and input components is used as the basis against which to conceptualise the ToC and to determine the underlying assumptions.

The EIA system design happened over the course of two decades. Before 1997, EIA in South Africa was conducted on a voluntary basis, mainly in line with international understandings adopted from the United States. During this pre-legislation period no formal EIA system existed, because there was no administration or regulatory requirements in place. The period between 1997 and 2006 could be seen as a transitional period for the EIA system when the mandate for EIA was changed from the first dispensation legislation (i.e. Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989) to be aligned with the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 (NEMA). This paper and the ToC narrative reflect specifically on the period post 2006, or on the so-called NEMA EIA system/regime.

The preamble to NEMA shows that the NEMA EIA system was explicitly designed to give effect to the environmental right contained in Section 24 of the South African Constitution – as will also be highlighted below in relation to the system impact component. To this end, EIA as a policy implementation instrument is seen as a ‘reasonable measure’ to give effect to the environmental right. As a framework Act, NEMA provides for the setting of sustainability principles for decision-making and against which decisions must be justified; promulgation of regulations for command and control instruments such as EIA to regulate future activities; and the setting of objectives for EIA.

For implementation, NEMA relies on policy implementation instruments and the promulgation of regulations by the regulator. The first NEMA EIA Regulations were promulgated in 2006 and have since been revised four times, in 2010, 2014 and 2017. The EIA regulations prescribe mandates and responsibilities for different role players; procedures to be followed; report content requirements; specific activities to be regulated and provides for the issuing of environmental authorisations (i.e. command and control approach).

However, because EIA is also essentially an administrative action (It involves a series of decisions being taken to either accept or reject applications) it is also strongly governed through administrative justice and more specifically Section 33 of the South African Constitution and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act 3 of 2000 (PAJA). In order to promote environmental justice, PAJA provides for principles of just administrative action or decision-making, namely lawfulness, procedural fairness and reasonableness.

In view of the above the EIA system design in South Africa is therefore established, prescribed and embedded in legislation which explicitly governs decision-making related to the environmental right (NEMA and EIA Regulations) and implicitly to just administrative action, namely, PAJA. The main inputs to the EIA system are specific skills and competencies. The logic that underpins this is that in order to make informed decisions, information is required which is derived from different role players with different skills and competencies, as prescribed within the legal framework for EIA in South Africa. These role players are the following and their roles are prescribed in the EIA legislation:

Consultant/Environmental Assessment Practitioner (EAP) providing project management and integrative thinking skills and competencies as defined in NEMA and the South African Qualification Authority’s qualification standard for Environmental Assessment Practice (SAQA ID 61831).

Specialists providing scientific skills and competencies. These inputs are typically considered as the scientific basis for decision-making.

Public/Civil Society providing inputs based on values, experience and local knowledge. These inputs are typically considered as evidence for decision-making.

Administrators/officials providing administrative and review skills and competencies. This typically requires integrated thinking and understanding of issues.

Judiciary providing judicial skills, oversight and interpretation of legislation.

The developer/applicant providing an understanding of the particular development and/or sector.

The EIA system relies on inputs related to time and money. In this regard, the main direct financial burden in the South African system lies with the applicant who pays for the appointment of the EAP and conducting of the EIA. The cost input in terms of EIA administration and review is borne by government. Application of the ToC approach to the South African system relies on the following key assumptions in relation to the design and input components.

Assumption 1: A Command and Control based approach geared towards regulating future activities is an effective way to give effect to the environmental right of all South Africans.

Assumption 2: Sufficient skills and competencies exist to implement the EIA system.

Assumption 3: The benefits of doing EIA outweigh the costs.

Activity and output components

The activity component deals with the process or actions that use the inputs to produce the outputs (Weiss Citation1995; Connell and Kubisch Citation1998; DMPE, Citation2011; Thornton et al. Citation2017). In this case, the activity component is related to activities comprising the EIA process. The output component represents the final ‘products’ which EIA delivers in the form of the EIA reports (i.e. Scoping, Basic Assessment, EIA, Environmental Management Programme or EMPr) used to inform authorisation decision-making by the regulator. The causal narrative argues a causal link between the activities related to the EIA process and the eventual quality of the EIA report. The activities within the South African EIA system reflect the international best practice operational principles and are prescribed as procedural phases in the EIA Regulations. These phases are linked to prescribed regulated timeframes. Broadly speaking they include:

Screening: The aim of screening is to determine if an EIA is required, and if so, the process to be followed. The Regulations prescribe that screening be done by the EAP appointed by the applicant. It involves the screening of the proposed development against published lists of activities published in the EIA Regulations.

Scoping: Scoping is prescribed by NEMA as a specific procedural step and requires the EAP to identify key issues to be addressed in the assessment phase. Public participation is an important action during scoping.

Assessment and evaluation: NEMA defines the actions of assessment and evaluation slightly differently, with assessment being more objective and science-based while evaluation recognises the subjective and value-driven nature of assessment. The South African EIA Regulations define objectives for the environmental assessment process. Ultimately the assessment and evaluation activity needs to identify significant impacts and communicate the finding in an EIA report to inform decision-making. Typically, the assessment includes activities such as site visits and consideration of specialist inputs.

Public participation: This activity is mandated through specific sections in NEMA as well as the EIA Regulations. The comments received during the public participation process must be recorded and responded to by the EAP and reflected in the final EIA reports.

Review: This activity is done by the EIA administrators/officials against prescribed decision-making criteria contained in NEMA and PAJA. There are primarily four documents (outputs) that get reviewed depending on the process triggered during screening, namely, Scoping Report, Basic Assessment Report (BA), EIA Report and the Environmental Management Programme (EMPr). The outcome of the review should be reflected in the eventual decision/authorisation.

Appeal: This activity is triggered post decision-making and is regulated by Appeal Regulations. It requires a reconsideration of the decision by the appeal authority and may result in a revised decision.

The outputs of the EIA process are expected to be good quality reports that contain sufficient information to make informed decisions on proposed activities that might detrimentally impact on the environment. Therefore, the causal logic suggests that the EIA system primarily produces good quality reports as the main output or ‘product’. The type of report is dependent of the process triggered during screening.

Key assumptions that underpin the activity and output components of the South African EIA system are that:

Assumption 4: Non-discretionary list-based screening effectively triggers the need for EIA.

Assumption 5: It is possible to identify and agree on key issues during scoping.

Assumption 6: It is possible to determine and agree on significance during assessment and evaluation.

Assumption 7: EIA is a scientific exercise where EAPs and specialists are rational and unbiased.

Assumption 8: Impacts can be accurately predicted.

Assumption 9: The public is willing and sufficiently capacitated to participate and to do so in good faith.

Assumption 10: Reviewers read reports.

Assumption 11: Reviewers understand the content of reports.

Assumption 12: Reviewers are rational, impartial, unbiased and objective.

Assumption 13: Reviewers share the same value system.

Assumption 14: Appeal Authorities are objective and impartial.

Assumption 15: An efficient process, as determined by the prescribed timeframes, will produce good quality reports.

Assumption 16: Good quality reports will lead to informed decisions.

Outcome and impact components

The outcome component reflects the results of achieving certain outputs (Weiss Citation1995; Connell and Kubisch Citation1998; DMPE, Citation2011; Thornton et al. Citation2017). In this case, the outcome component is represented by the decision as reflected in the environmental authorisation. The impact component represents the results of achieving certain outcomes (DMPE, Citation2011). In this case, the impact component relates to the extent to which EIA is giving effect to the progressive realisation of the environmental right contained in Section 24 of the South African Constitution.

The main immediate outcome of EIA is a decision informed by the content of the EIA report. Although decision-making happens incrementally throughout the EIA process, the final outcome is a single decision authorising or refusing future activities. It could therefore be argued that the immediate outcome of the EIA system is numerous authorisations or refusal decisions on listed activities related to individual projects. The decision is communicated through an environmental authorisation that explains the rationale and justification for the decision. The decision outcome is governed by set criteria against which the decision must be taken as stipulated in inter alia NEMA as well as PAJA which determines that decisions must be lawful, procedurally fair and reasonable (Kotze and Van der Walt Citation2003).

The EIA literature has highlighted numerous intermediate outcomes such as changes in values, promotion of transparency in decision-making, capacity building and empowerment, promotion of administrative justice, as well as knowledge generation and better understanding of impacts (Morgan Citation2012; Pope et al. Citation2013). Ultimately it may be argued that these intermediate outcomes are accurately reflected in the foundational principles of NEMA. Therefore, giving effect to the NEMA represents the intermediate outcomes of EIA. This makes sense since NEMA must underpin EIA decision-making toward progressive realisation of Section 24 of the South African Constitution (Kidd Citation2011; Kidd et al. Citation2018), which states:

“Everyone has the right –

to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being; and

to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures that –

prevent pollution and ecological degradation;

promote conservation; and

secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development.”

The following assumptions underpin the causal logic of having EIA as a policy implementation instrument, especially assumption 19, which goes to the heart of what EIA in South Africa is about:

Assumption 17: Decisions are underpinned by prescribed decision making principles.

Assumption 18: Decisions are lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair.

Assumption 19: Informed decisions regulating future activities, that are lawful, reasonable and procedurally fair, will lead to progressive realisation of the Section 24 environmental right.

The discussion above shows how the application of the ToC approach to the south African EIA system helps to identify key assumptions underpinning the different components of the system. The assumptions identified are specific to the South African EIA system and it is acknowledged that other EIA systems, depending on their design and expectations, may produce different assumptions. For example, the assumptions listed above related to screening would not be applicable to systems where a discretionary-based approach is adopted. Moreover, in systems where review panels are used, the assumptions around the review activity might be different. However, such a comparative analysis with other contexts can only be done once ToC has been applied more widely.

Conclusion and recommendations

In this paper, we introduced the concept of evaluative thinking, which relies on the identification and evaluation of key assumptions. When applying evaluative thinking, assumptions provide the basis for EIA evaluation. Ultimately, if the underlying assumptions are flawed, then the fundamental understandings on which the EIA system is based could be questioned and new understandings may emerge. Therefore, as a first step towards applying evaluative thinking to EIA, the paper aimed to identify key assumptions to be considered in the evaluation of EIA. To this end, the ToC method was offered to distil key assumptions underpinning EIA. The application of the ToC method to the South African EIA system produced a conceptual framework around different evaluation components, namely: design, inputs, outputs, outcome, and impact components as well as identifying 19 underlying key assumptions.

Although the latter assumptions were identified specifically for the South African EIA system, we contend that they have broad international validity and relevance, and that the application of the ToC method to other EIA systems would reasonably herald similar results. Following on from this research it is now important to test these assumptions, so as to understand how these assumptions might influence our fundamental understanding of how EIA works. Existing literature already suggest that some of the identified assumptions could be questioned. For example, assumption 8, assuming a high level of accuracy in prediction (Holling Citation1978; Retief et al. Citation2016) as well as assumptions 10 to 13 which deal with the role of reviewers and assumptions around rationality, impartiality and values could similarly be questioned (Owens et al. Citation2004; Kornov and Thissen Citation2000). It is therefore concerning that system design still seemed to based on flawed assumptions. The testing of these assumptions will also assist and feed into more theoretical debates around those models already developed by, for example, the information processing model by Bartlet and Kurian (Citation1999) and the technical rational model referred to by Owens et al. (Citation2004). In this paper, we are arguing in support of a re-think of the fundamental nature and understandings of EIA as a policy implementation instrument. By critically reflecting on the underlying assumptions we can purposefully take EIA forward as an instrument of choice for decision makers into the 21st century.

References

- Allen W, Cruz J, Warburton B. 2017. How decisions support systems can benefit from a theory of change approach. Environ Manage. 59(6):956–965.

- Archibald T, Sharrock G, Buckley J, Cook N. 2016. Assumptions, conjectures, and other miracles: the application of evaluative thinking to theory of change models in community development. Eval Programme Plann. 59:119–127.

- Arts J, Runhaar H, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance – a comparison of the Netherlands and the UK. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14(4): 1250025–1-40.

- Bartlet R, Kurian P. 1999. The theory of environmental impact assessment: implicit models of policy making. Policy Politics. 24(4):415–433.

- Bond A, Retief F, Cave B, Fundingsland-Tetlow M, Duinker PN, Verheem R, Brown AL. 2018. ‘A contribution to the conceptualisation of quality in impact assessment’. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:49–58.

- Brouselle A, Champagne F. 2011. Programme theory evaluation. Logic Anal Eval Programme Plann. 34:69–78.

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 22(4):295–310.

- Connell J, Kubisch A. 1998. Applying a theory of change approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives: progress, prospects and problems. In: Fulbright-Anderson K, Kubisch A, Connell J, editors. New approaches to evaluating community initiatives, Vol. 2, Theory, measurement, and analysis. Washington (DC): Aspen Institute; p. 1–10.

- DPME. 2011. National Evaluation Policy Framework. Pretoria: National Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation.

- Foundation for Critical Thinking. 2019. Defining critical thinking; [accessed 2019 Jul 11]. https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

- Glasson J. 1999. The first 10 years of UK EIA system: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Plann Theory Pract. 14(3):363–375.

- Hallat T, Retief F, Sandham L. 2015. ‘A critical evaluation of the quality of biodiversity inputs to EIA in areas with high biodiversity value – experience from the Cape Floristic Region, South Africa. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 17(3):1–26.

- Hartse JC, Woodward VA, Burke CL. 1984. Examining our assumptions: A transactional view of literarcy and learning. Res Teach English. 18(1):84–108.

- Holling CS. 1978. Adaptive environmental assessment and management. New Jersey: Blackburn Press.

- IAIA. 1999. International EIA best practice principles. Fargo:International Association for Impact Assessment, IAIA.

- Jane Davidson E. 2004. Evaluation methodology basics: the nuts and bolts. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage publications.

- Jha-Thakur U, Fischer TB. 2016. 25 years of the UK EIA system: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:19–26.

- Jones R, Fischer TB. 2016. EIA Follow-Up in the UK – a 2015 update. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 18(1):1650006 (1–22).

- Kidd M. 2011. Environmental Law. Cape Town: Juta.

- Kidd M, Retief F, Alberts R. 2018. Integrated environmental assessment and management. In: King N, Strydom H, Retief F, editors. Environmental management in South Africa. 3rd ed. Cape Town: Juta; p 213–275.

- Kornov L, Thissen W. 2000. Rationality in decision- and policy-making: implications for strategic environmental assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 18(3):191–200.

- Kotze L.J, Van der Walt A.J. 2003. 'Just Administrative Action and the issue of unreasonable delay in the environmental impact assessment process: A South African perspective'. South African Journal of Environmental Law and Policy. 10(1):39–61.

- Loomis JJ, Dziedzic M. 2018. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness. A state of the art. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:29–37.

- Lucas AM. 1975. Hidden assumptions in measures of ‘knowledge about science and scientists’. Sci Educ. 59(4):481–485.

- Mason P, Barnes M. 2007. Constructing theories of change. Evaluation. 13(2):151–170.

- McChesney FS. 1986. Assumptions, empirical evidence and social science method. Yale Law J. 96(2):339–341.

- McConnell J. 2019. Adoption for adaption: A theory-based approach for monitoring a complex policy initiative. Eval Programme Plann. 73:214–233.

- Morgan RK. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):5–14.

- Nkwake AM. 2013. Working with assumptions in international development program evaluation. New York: Springer.

- Owens S, Rayner T, Bina O. 2004. New agendas for appraisal: reflections on theory, practice, and research. Environ Plann A. 36(11):1943–1959.

- Paul RW, Elder L. 2002. Critical thinking: tools for taking charge of your professional and personal life. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Financial Times Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-064760–8.

- Pope J, Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2013. 'Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment. Setting the research agenda', Environ Impact Assess Rev. 41:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.01.008

- Retief F. 2010. The evolution of environmental assessment debates – critical perspectives from South Africa. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 12(4):1–23.

- Retief F, Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, King N. 2016. Global megatrends and their implications for Environmental Assessment (EA) practice. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:52–60.

- Rogers P,J. 2008. Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation. 14(1):29–48.

- Runhaar H, Fischer TB. 2012. Special issue on 25 years of EIA in the EU. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14(4):1202002 (5 pages).

- Sadler B. 1996. International Study of the Effectiveness of Environmental Assessment Final Report - Environmental Assessment in a Changing World: Evaluating Practice to Improve Performance. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada. p. 248.

- Sandham L, Carrol T, Retief F. 2010. The contribution of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) to decision making for biological pest control in South Africa – the case of Lantana camara. Biol Control. 55:141–149.

- Sandham L, Hoffman A, Retief F. 2008b. Reflections on the quality of mining EIA reports in South-Africa. J South Afr Inst Min Metall. 108:701–706.

- Sandham L, Moloto M, Retief F. 2008a. The quality of environmental impact assessment reports for projects with the potential of affecting wetlands. Water SA. 34(2):155–162.

- Sandham L, Van der Vyver F, Retief F. 2013b. Performance of environmental impact assessment in the explosives manufacturing industry in South Africa. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 15(3):1–18.

- Sandham L, Van Heerden A, Jones C, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2013a. Does enhanced regulation improve EIA report quality? Lessons from South Africa. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 38:155–162.

- Sandham LA, Pretorius HM. 2007. A review of environmental impact report quality in the North West Province of South Africa. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28(4–5):229–240.

- Schawnd T. 2015. Evaluation foundations revisited: cultivating a life of mind for practice. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press.

- Stein D, Valters C. 2012. Understanding “Theory of Change” in international development: a review of existing knowledge. Paper prepared for The Asia Foundation and the Justice and Security Research Programme at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Swanepoel F, Retief F.P, Bond A, Pope J, Morison-Saunders A, Hauptfleisch, M andFundingsland M. 2019. Explanations for the quality of biodiversity inputs to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in areas with high biodiversity value. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 21(2):1–30. doi:10.1142/S1464333219500091.

- Thornton PK, Schuetz T, Forch W, Cramer L, Abreu D, Vermeulen S, Campbell BM. 2017. Responding to global change: A theory of change approach to making agricultural research for development outcome-based. Agric Syst. 152:145–153.

- USAID. 2015b. Technical references for FFP development food assistance projects Bureau of Democracy, conflict and humanitarian assistance office of food for peace.

- Van der Sluijs J. 2017. Uncertainty, assumptions and value commitemnts in the knowledge base of complex environmental problems. In: Pereira AG, Vaz SG, Tognetti S, editors. Interfaces between science and society. 1st ed. London: Routledge; p. 67–87.

- Weiss CH. 1995. Applying a theory of change approach to the evaluation of comprehensive community initiaitves: progress, prospects, and problems. In: Fullbright-Anderson K, Kubisch AC, Connell JP, editors. New approaches to evaluating community initiatives: concepts, methods and contexts. (Vol. 1). Washington D.C.: The Aspen institute; p. 65–92.

- Wood C. 1999. Pastiche or postiche? Environmental impact assessment in South Africa. South Afr Geog J. 81:52–59.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: a comparative review. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Yang T. 2019. The emergence of the environmental impact assessment duty as a global legal norm and general principles of law. Hastings Law J. 70(2):525–572.