1. Introduction

“How can we effectively address persisting challenges, in particular with regards to the effectiveness of IA instruments?” (Fischer & Bice, Citation2019, call for contributions to the special issue).

In this commentary, we return to the interminable issue of effectiveness (after Cashmore et al. Citation2004) in addressing the question posed by the editors on how the Environmental Assessment (EAFootnote1) community might address persisting challenges and enhance effectiveness. The editors’ note that increasingly Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is viewed as ‘seriously lagging behind its potential’. On the one hand, SEA is hardly exceptional in this respect as many environmental governance tools have failed to perform as expected (Pattberg and Widerberg Citation2015). Nevertheless, hard questions should be asked about any policy tool that is ‘seriously lagging behind its potential’ in an era where the need for radical societal transformations are high on scientific and political agendas.

We argue that new that new ways of organising the ‘knowledge systems’ (after Cornell et al. Citation2013) underpinning the relationship between knowing and acting are likely to be a key driver of advances in this field. This leads us to focus in this commentary on innovation, the production of salient, legitimate and actionable knowledge, and renewal of the so-called science-policy interface. A central claim we make is that is that there has been a lack of innovation in the EA community’s understanding of the practical measures for making SEA effective and that the conceptual and evidential support for often-proposed practical measures is typically partial. We ground this claim empirically by briefly examining examples of the policy recommendations made in three SEA evaluation studies that were conducted for European SEA systems. It is argued that ‘received wisdom’ on practical measures required to make EA effective has changed remarkably little since the early 1980s, despite important theoretical, conceptual and empirical developments having taken place during this period of time. We conclude by considering how a renewal of the science-policy interface, combined with a willingness to experiment, may provide an important stimulus to the emergence of innovative thinking and actionable knowledge.

2. What makes EA effective? Examples of SEA policy recommendations

To exemplify what we argue is a lack of innovation in addressing issues concerning effectiveness, we review the policy recommendations proposed in small number of evaluation studies. These policy recommendations reflect perceptions of how to enhance the performance of real-world practices; thus, they provide a window into multiple dimensions of the way in which knowledge systems and science-policy interfaces are enacted. Policy recommendations also provide a lens through which to interrogate, amongst other things, actors’ understandings of the concept of effectiveness; the beliefs of those commissioning and undertaking evaluation research concerning how the science-policy interface should be organised; and, for examining the historical development of thinking on what makes EA effective.

Three evaluation studies were purposefully selected (i.e. not randomly chosen) for investigation based on a literature search for, and our knowledge of, examples of large-scale SEA evaluation studies. We have been involved in two of these studies in various capacities, including as a member of the scientific panel (study 1, Cashmore) and as participants in questionnaire surveys and focus groups (study 2, Cashmore and Smutny). The studies examine European SEA systems and, therefore, explicate understandings of how to make SEA effective that are strongly grounded in this socio-political and historical context.

The first study is a national review of SEA practices that was commissioned by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. The intention of the project was to map existing practices in Sweden, and internationally, and propose recommendations for strengthening Swedish policy and practice (Balfors et al. Citation2018). The final report for this study was published at the start of 2018. The second study addresses the implementation of EU SEA legislation across all Member States. The stated purpose of this project was to provide the European Commission (EC) with information on progress with the practical implementation of the legislation and on the challenges encountered by Member States. It was not an explicit aim of this study to formulate policy recommendations, but the authors, nevertheless, chose to include suggestions for improvements. This study was published in 2016. The third study is another evaluation of the application and effectiveness of SEA legislation commissioned by the EC. This study was conducted relatively soon (i.e. a 5 year evaluation) after EU-wide provisions for SEA were introduced. The final report was published in 2009.

The nature of the main policy recommendations proposed in each of the three evaluation research case studies are summarised in . Our principal observation on the policy recommendations summarised in is that there is a fairly high level of similarity, firstly, in the policy recommendations being proposed within these studies and, secondly, with proposals made at earlier points in time in the EA literature. For example, there are numerous examples of recommendations for quality reviews by independent panels (e.g. O’Riordan and Sewell Citation1981), the compilation of databases of various sorts (e.g. Hollick Citation1981), capacity development (e.g. Beanlands and Duinker Citation1984), and guidance (e.g. Bisset, Citation1984) in EIA literature published in the 1980s. Such policy measures thus appear central to the EA community’s understanding of effective practices. Furthermore, these policy measures appear to have maintained this status as accepted ‘solutions’ despite many theoretical and conceptual premises of EA having fundamentally altered over time. We can formulate that observation in another way: on the basis of the proposals summarised in , there appear to have been few substantive innovations in the types of policy recommendations being proposed over the last 40 years.

Table 1. Examples of the policy recommendation made in three studies of SEA systems.

3. Questioning ‘received wisdoms’

Our observation that there is a fairly high level of similarity amongst policy recommendations that are intended to promote effective SEA practices is not necessarily problematic in itself. It might suggest that the appropriate solutions to ineffective practices are well-recognised and accepted: i.e. that we know how to make SEA operate effectively and the problematic issue is the so-called ‘implementation gap’ (i.e. policy and practices diverge from theory/best practices). And yet, there is reason to question this presumption. Critically, the various assumptions underpinning notions of effective EA have been subjected to limited conceptually rigorous or empirically systematic testing. Consequently, there is a paucity of robust evidence to support implicit claims or assumptions about the efficacy of many of the policy recommendations listed in . Such recommendations appear to have acquired the status of received wisdom amongst the EA community without strong conceptual or empirical support. This observation raises a plethora of questions about why this is the case.

There are increasingly grounds for questioning the efficacy of many of these policy recommendations. Let us take as an example what appears to be received wisdom on certain quality control measures. The use of expert panels to determine the scope of an EA and to review reports, and the accreditation of skilled practitioners, appear logical in socio-political contexts where expertise is highly valued. But do such measures axiomatically enhance effectiveness? And, just as importantly, for whom and in what ways do they improve effectiveness?

Exploratory research on stakeholders' perceptions of the effectiveness of national EA systems in Denmark and the Netherlands has suggested the relationship between quality control and effectiveness may be more complicated than is commonly accepted (see Lyhne et al. Citation2016). Fairly demanding quality control measures are employed in the Netherlands, as has been popularised by Chris Wood’s description of the Dutch system, at that point in time, as a ‘Rolls Royce’ amongst EA systems (Wood Citation2003). Quality control provisions in Denmark no doubt appear minimalistic under Chris Wood’s analytical lens, but they foreground – expediently or otherwise – the role of an engaged polity in policing government and private enterprise. Intriguingly, the survey results from this study indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between the opinions of government officials and practitioners in the two countries on the issues of the credibility of EA reports, the level of environmental integration achieved through EA, and the influence of EA on decision-making (Lyhne et al. Citation2016). There are many potential explanations for these observations and they are certainly not a basis for rejecting received wisdom about the value of the Dutch approach to quality control. Nevertheless, they serve to highlight the need for critical conceptual and robust empirical enquiry on the issue of effectiveness.

If we consider accreditation schemes for certifying who can practice EA (a suggestion in Study 1), we have found this to be a particularly popular quality control option amongst policy makers, notably, in a European context, in Eastern European and Balkan countries. In such regions, accreditation has often been viewed as the primary measure for quality control. And yet there is a lack of evidence that such measures contribute to effectiveness, or perhaps on the institutional contexts under which they contribute. Our experiences (tacit knowledge) indicate that such systems have proven problematic in a number of contexts: e.g. Czechia, Croatia and China (and see Wang et al. Citation2003). Market-driven accreditation schemes in the UK, on the other hand, are an alternative model that appear to offer some advantages in particular contexts (Bond et al. Citation2017), but they remain at the periphery of our policy armoury.

Our argument that there has been limited conceptually rigorous or empirically robust testing of policy recommendations leads us to question why more attention has not been given to generating evidence of what works in, what is now, a well-established policy field? As Sue Owens and colleagues noted in 2004:

‘We are tempted to observe that a great deal has been written about the virtues of different approaches to appraisal but rather less has been done to test the various claims through meticulous empirical work. Developments in both theory and practice are likely to flow from such research.’ (Owens et al. Citation2004, p. 1953)

There are evidently practical challenges in undertaking empirical research on effectiveness, but there are also a series of well-developed approaches to analysing policy implementation (e.g. Vedung Citation1997). It is telling, we suggest, that the EA community collectively does not appear to have prioritised the generation of rigorous evidence to support policy.

4. Reconstituting EA science-policy interfaces

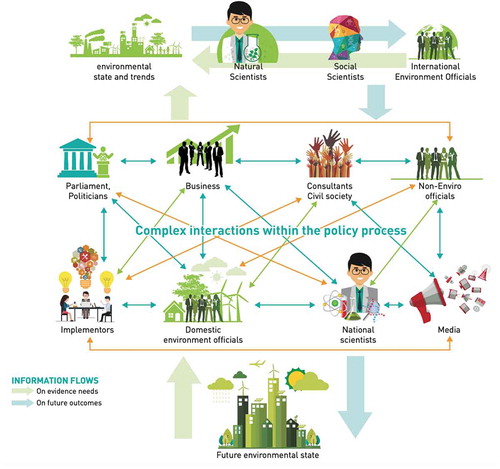

In a much cited interpretation, van den Hove (Citation2007, p. 815) defines science-policy interfaces as ‘social processes which encompass relations between scientists and other actors in the policy process, and which allow for exchanges, co-evolution, and joint construction of knowledge with the aim of enriching decision-making’. As indicates, such interfaces are generally understood to be more encompassing than historically was the case, particularly in terms of the range of actors engaged, the complexity of policy-making processes, and in interpretations of valid and useful ways of generating knowledge (Watson Citation2012).

Figure 1. A representation of the science-policy interface.

Source: (UNEP Citation2017)

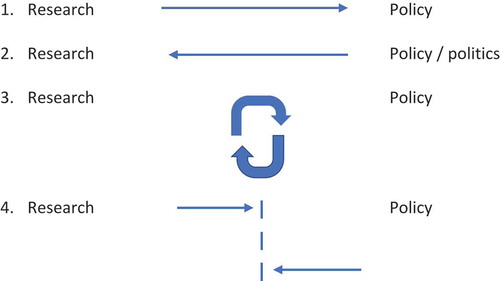

A profound renewal of science-policy interfaces within the EA field could form an important driver of innovation. We anticipate these changes as mirroring some of the new approaches to developing knowledge for policy action on global environmental issues, often conducted under the mantra of sustainability science (Kates Citation2001). The envisaged renewal would include a focus upon actionable knowledge and a renegotiation of the contract between science for EA and society. There is a rich and vibrant literature on knowledge utilisation in policy making that we believe the EA community could productively engage with in reflecting on renewing the science-policy interface. In a recent summary of this literature, Boswell and Smith (Citation2017) delineate four main models of the relationship between science and policy (see ). These models range from a situation in which science (or knowledge production more generally) is believed to instrumentally affect policy (model 1) to one in which there are no direct relations between science and policy (model 4). Forms of joint problem solving – including the much-vaunted notion of co-producing knowledge (model 3) – are frequently referenced in evaluation research as something of a gold standard. Although the notion of coproduction is variously interpreted (van der Hel Citation2016), it has gained considerable traction internationally (De Pryck and Wanneau Citation2017). It has, for instance, become a core operating principle of numerous global environmental programmes, such as Future Earth and the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Figure 1. Science-policy relations.

Notes: The figure depicts four models of research-policy relations: 1. Research informs policy; 2. Policy and politics shape research; 3. Research and policy are coproduced; and 4. Research and policy are autonomous domains.Source: adapted from (Boswell and Smith Citation2017)

The three case studies discussed in this letter certainly claim to have involved a variety of actors in formulating the evaluation findings and recommendations, including through: questionnaires, focus groups, interviews, workshops and conferences. However, based on our knowledge of these evaluation studies, we question whether they truly extended beyond an instrumental model of knowledge production and utilisation (i.e. model 1 in ). Indeed, the design and content of the final reports for the case example evaluation studies largely re-enact an instrumental model of speaking ‘truth’ to ‘power’. For example, in study 1, the authors propose a ‘smorgasbord’ of recommendations – that is, a metaphorical buffet of options from which policy-makers may pick and mix. No prioritisation of these options is provided in this case, nor in either of the other two evaluation studies. Nor are the policy recommendations examined in terms of compatibility, practicability, or political acceptability in the Swedish context. As we noted, it was not an explicit goal of the second evaluation study to formulate policy recommendations; the terms of reference focused on the generating and synthesising knowledge for transmission to the policy community. All of the evaluation studies appear to be constituted based on presumption that the presented findings and (where relevant) recommendations were to be considered further outside of scientific or evidential evaluation; that is to say, a strong divide between knowledge production and utilisation is reconstituted through the reports.

The core elements of successful co-design of transdisciplinary knowledge production are well-documented (Cornell et al. Citation2013), but they do not appear to have been enacted in these case examples. This suggests to us that a purposeful policing of the boundary between science and knowledge, on the one hand, and policy and politics, on the other hand, may be taking place through these case studies. The Swedish smorgasbord, as a form of boundary maintenance, may be indicative, we suggest, of the relative comfort that either or both the science and policy communities find in the traditional instrumental model of knowledge utilisation. The absence of demand for policy recommendations in the second case study may reflect a belief that in the context of the EU political system, the relationship between knowledge and policy is highly complex. Nevertheless, it also enacts an apparent apathy to changing the relationship between science and politics, which is the ultimate goal of co-production (Kates Citation2001).

The language of experimentation (or somewhat similar concepts like ‘hacking’ (Chandler Citation2018)) has increasing dominated discussions on urban governance in recent years. We speculate that small scale experimentation with innovative policy approaches would be valuable in generating actionable knowledge on effectiveness, in part by encouraging more meaningful collaboration between science and policy communities. Experimentation is not straightforward in a situation where procedural expectations are codified in legislation and case law; as per one interpretation of coproduction knowledge and governance are mutually constituted, meaning that it is inherently difficult to introduce radical innovations. Yet we view experimentation as a key measure for introducing the forms of creativity, and also accountability and humility, that can result in salient and actionable knowledge. Within this context, some of us have argued that it might be appropriate to simplify legislation in certain jurisdictional contexts (Musil and Smutný Citation2019), as this could lead to greater flexibility in decisions about how to achieve the substantive goals of EA in individual cases.

5. Final comments

In this commentary, we have articulated our shared concern over what we perceive to be a lack of substantive innovations in discussions about how to make SEA effective. We contrast this lack of innovation against the urgency of politically and practically addressing multiple sustainability crises. Policy recommendations on how to make SEA work more effectively have been used to substantiate our claim concerning a lack of innovation. We emphasise that such a claim is not particularly novel, but we feel it is important to emphasise it, once again, within the context of this special issue on the future of EA tools.

As a community, we need to prioritise the creation of institutions for generating truly coproduced, problem-driven knowledge on effectiveness. There are many examples (good and bad) of such institutions, from those with a global remit (e.g. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the Intergovernmental Science- Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, and the Future Earth platforms) through to smaller scale examples at the national and local scales. Needless to say, the problem of enhancing exchanges of salient and actionable knowledge across science-policy interfaces is not limited to EA; it is arguably one aspect of the new forms of governance that must underpin sustainability transformations (Miller and Wyborn Citation2018). Given this, we strongly concur with Chaffin et al. (Citation2016, p. 401), who note that ‘new drivers that displace entrenched forms of environmental governance and provide space for innovation’ may be needed.

Notes

1. We use the term EA to cover both so-called Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). We use the editors’ comments on SEA in the call for submission to the special issue (Impact Assessment for the 21st century – what future?) and evaluation research on SEA as a platform to open-up discussion points that are often equally applicable to both forms of EA. Thus, we use both the terms SEA and EA in this letter.

References

- Balfors B, Antonson H, Faith-Ell C, Finnveden G, Gunnarsson-Östling U, Hörnberg C, … Wärnbäck A (2018). Strategisk miljöbedömning för hållbar samhällsplanering Slutrapport från forskningsprogrammet SPEAK [Eng. Strategic environmental assessment for sustainable planning: final report from the SPEAK research program]. Stockholm. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Documents/publikationer6400/978-91-620-6810-3.pdf?pid=21969.

- Beanlands GE, Duinker PN. 1984. An ecological framework for environmental impact assessment. J Environ Manage. 18:267–277.

- Bisset R. 1984. Post-development audits to investigate the accuracy of environmental impact predictions. ZfU. 4:463–484.

- Bond A, Fischer TB, Fothergill J. 2017. Progressing quality control in environmental impact assessment beyond legislative compliance: an evaluation of the IEMA EIA quality mark certification scheme. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 63:160–171. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2016.12.001

- Boswell C, Smith K. 2017. Rethinking policy “impact”: four models of research-policy relations. Palgrave Commun. 3(1). doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0042-z

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 22(4):295–310. doi:10.3152/147154604781765860.

- Chaffin BC, Garmestani AS, Gunderson LH, Benson MH, Angeler DG, Arnold CA (Tony), … Allen CR. 2016. Transformative environmental governance. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 41(1):399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085817.

- Chandler D. 2018. Ontopolitics in the anthropocene: an introduction to mapping, sensing and hacking. London: Routledge.

- Cornell S, Berkhout F, Tuinstra W, Tàbara JD, Chabay I, de Wit B, … van Kerkhoff L. 2013. Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environ Sci Policy. 28:60–70. doi:10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2012.11.008

- De Pryck K, Wanneau K. 2017. (Anti)-boundary work in global environmental change research and assessment. Environ Sci Policy. 77:203–210. doi:10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2017.03.012

- European Commission. (2009). Study concerning the report on the application and effectiveness of the SEA Directive (2001/42/EC). doi:10.2779/725510

- European Commission. (2016). Study concerning the preparation of the report on the application and effectiveness of the SEA Directive (Directive 2001/42/EC). Luxembourg. doi:10.2779/725510

- Fischer T, Bice S. (2019) Impact Assessment for the 21st century – what future? Call for contributitons to the special issue.

- Hollick M. 1981. Environmental impact assessment as a planning tool. J Environ Manage. 12:79–90.

- Kates RW. 2001. Sustainability science. Science. 292(5517):641–642. doi:10.1126/science.1059386.

- Lyhne I, Cashmore M, Runhaar H, van Laerhoven F. 2016. Quality control for environmental policy appraisal tools: an empirical investigation of relations between quality, quality control and effectiveness. J Environ Policy Plann. 18(1):121–140. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1053438.

- Miller CA, Wyborn C. 2018. Co-production in global sustainability: histories and theories. Environ Sci Policy. doi:10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2018.01.016

- Musil M, Smutný M. 2019. Effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment in the Czech Republic. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 37(3–4):199–209. doi:10.1080/14615517.2019.1578482.

- O’Riordan T, Sewell WRD. 1981. From project appraisal to policy review. In: O’Riordan T, Sewell WRD, editors. Project appraisal and policy review. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons; p. 1–28.

- Owens S, Rayner T, Bina O. 2004. New agendas for appraisal: reflections on theory, practice, and research. Environ Planning A. 36(11):1943–1959. doi:10.1068/a36281.

- Pattberg P, Widerberg O. 2015. Theorising global environmental governance: key findings and future questions. Millennium J Int Stud. 43(2):684–705.

- UNEP. 2017. Strengthening the science-policy interface: A gap analysis. Nairobi: United Nations Environment. http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm.

- van den Hove S. 2007. A rationale for science – policy interfaces. Futures. 39:807–826. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2006.12.004

- van der Hel S. 2016. New science for global sustainability? The institutionalisation of knowledge co-production in future earth. Environ Sci Policy. 61:165–175. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2016.03.012

- Vedung E. 1997. Public policy and program evaluation. London: Routledge.

- Wang Y, Morgan RKRK, Cashmore M. 2003. Environmental impact assessment of projects in the People’s Republic of China: new law, old problems. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(5):543–579. doi:10.1016/S0195-9255(03)00071-4.

- Watson RT. 2012. The science – policy interface: the role of scientific assessments — UK national ecosystem assessment. Proc Royal Soc A. 468(March):3265–3281. doi:10.1098/rspa.2012.0163.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: A comparative review. 2nd ed. Harlow: Prentice Hill.