ABSTRACT

With increased political polarisation and the emergence of populist governments around the world – many of which erode regulatory requirements such as EIA – there is an urgent need to be able to identify and explain the potential benefits of EIA for government. The aim of this paper is to explore the benefits of EIA for government as perceived by EIA regulators. A semi-structured questionnaire was administered to 175 representatives from the South African EIA regulator. The questionnaire asked the respondents to indicate what they perceive to be potential and realised EIA benefits for government. They were also asked how they recommend the gap between potential and realised benefits might be closed. The results show that the main perceived benefits of EIA to government relate to short-term, project-specific benefits such as the protection of local biodiversity, public participation, legal compliance and enforcement, as well as certain immediate economic benefits. The promotion of sustainable development is not considered a realistically achievable benefit for EIA. It is recommended that for EIA to clearly define and achieve its potential benefits for government, it needs to rediscover and embrace its roots as a project level instrument aimed at dealing with biophysical impacts and environmental protection.

1. Introduction

EIA is recognised as a key policy implementation instrument generally understood to assist governments in considering environmental consequences before decisions are made or actions taken (Jay et al. Citation2007; Arts et al. Citation2012; Morgan Citation2012; Drayson et al. Citation2017). Since the introduction of the instrument more than 50 years ago, EIA has increasingly gained popularity and has now been implemented in all countries worldwide (Morgan Citation2012; Bond et al. Citation2020). Even though EIA has been widely adopted and implemented, it has long since been acknowledged that different role players view the potential benefits of EIA differently, and therefore a plurality of views exist (Petts Citation1999; Cape et al. Citation2018). These role players typically include government decision-makers (or regulators), proponents (or developers), impact assessment consultants (or environmental assessment practitioners – EAPs) and the public (or interested and affected parties – IAPs). For example, different role players such as proponents sometimes consider impact assessment to be a time-consuming and regulatory hurdle, while others such as the affected public consider EIA essential to ensure transparency in decision-making and to provide an opportunity for their voices to be heard (Petts Citation1999; Pope et al. Citation2013). Therefore, dealing with the pluralistic nature of EIA is a particular challenge highlighted in the EIA literature (Peterson Citation2010; Bond et al. Citation2013), which is often further complicated by the fact that individuals within groupings of role players might further also have differing views (Fischer and He Citation2009).

The recent spread of populist governments around the world in countries such the United States, Brazil, Italy, and the Philippines has coincided with an increase in anti-regulatory rhetoric, especially around environmental regulation or so-called green tape, with some governments actively cutting back on impact assessment requirements altogether (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2014). The aforementioned might be partly ascribed to a failure in clearly identifying and articulating the benefits of EIA for different role players, in particular, governments (Bond et al. Citation2014; Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2015). Therefore, gaining a better understanding of the potential benefits of EIA for government is particularly important at this point in time. When considering the benefits of EIA for government, one needs to be mindful of the pluralistic nature of different role players’ perspectives. In this paper, we argue that although the views of proponents, consultants, and the public are relevant, it is particularly important to gain a better understanding of the perceived benefits of EIA for government, from the regulators themselves. Regulators are defined as government officials responsible for EIA review and decision-making. This would provide a kind of introspective view by those ultimately responsible for EIA decision-making. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore the benefits of EIA for government as perceived by EIA regulators.

Research dealing with the benefits of EIA is typically conducted within particular contexts. A key challenge for the methodological design of the research is, therefore, to identify a context which would be reasonably generalisable, so that the research results have broader relevance to an international audience. Generalisation is treated here as analytical generalisation where the findings are compared to benefits discussed in the literature, and so doing contributing to a better understanding of the benefits of EIA. For our purposes and in line with the research aim, such a context should ideally represent i) a well-established EIA system with ii) a broad environmental mandate (that includes sustainability consideration). It is assumed that the well-established system would ensure sufficient institutional and regulatory competency and that the broad mandate would ensure wide-ranging benefit expectations by regulators (including sustainability). South Africa was considered an ideal context since it has a well-established EIA system, with voluntary practice since the 1970 s and mandatory practice since the 1990s (Retief et al. Citation2007; Retief Citation2010; Kidd et al. Citation2018). Moreover, the South African EIA system has a broad EIA mandate that includes sustainable development, as conceptualised in the National Framework for Sustainable Development (NFSD). Admittedly there are many countries in the world that could potentially have been considered for the research. However, the authors were presented with a unique opportunity to access regulators within the South African context as part of a broader training and capacity building project. Moreover, the authors have many years of experience within the South African EIA context and were therefore well positioned to conduct the research (Martínez-Mesa et al. Citation2016).

The next section provides a brief description of the benefits of EIA conceptualised around a specific understanding of sustainable development. The research methodology is explained in Section 3, followed by an account of the data analysis and research results in Section 4. The paper concludes by highlighting what is perceived to be the main benefits of EIA for government by regulators.

2. Conceptualising the benefits of EIA

Numerous studies have been conducted dealing with questions such as, ‘is EIA working as intended?’ and/or ‘what is EIA achieving?’. These studies are typically framed around terminology such as effectiveness, success, follow-up, value, expectations, and objectives (Sadler Citation1996; Morgan Citation2012; Pope et al. Citation2013). Although studies have been done on the benefits of assessment tools such as SEA (Fischer Citation1999; Nooteboom Citation2000), the term benefit is not used that often in the EIA literature, and we could find no specific study that dealt with benefits for government, or perceived benefits by regulators. ‘Benefit’ is defined by the Oxford English dictionary as an advantage or profit gained from something and therefore thinking about benefits aligns well with the thinking that underpins typical effectiveness and/or follow-up studies. Hence, we see our research on benefits as also making a potential contribution to the broader debates around EIA effectiveness. The one notable study which dealt specifically with comparative views by different role players on the assumed EIA objectives is by Petts (Citation1999). The study found that so-called ‘decision authorities’ (or regulators for our purpose) assume for example the following EIA objectives, namely: conflict resolution so as to reduce appeals; streamline implementation processes; contribute to professional knowledge; introduce additional information and knowledge to the decision process; provide an additional check on project proponents; enhance confidence of politicians to take a decision; and inform and educate people about the development/planning process.

In order to build on the work by Petts (Citation1999), and accommodate in our data gathering and analysis as broad a range of perceived EIA benefits (for government by regulators) as possible, we decided on a conceptualisation of benefits around the concept of sustainable development. This decision is also supported by the following:

EIA is considered a key policy implementation instrument through which sustainability considerations and outcomes should be promoted in decision-making (Hacking and Guthrie Citation2008; Bond et al. Citation2012). The benefit of EIA for promoting sustainable development is therefore well established in the literature, although there are differing views on how exactly this could be achieved (Devuyst Citation2000; Wilkins Citation2003; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018).

Since the publication of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a total of 193 governments have committed to the promotion of sustainable development in their respective countries (Hacking Citation2018). It can be argued that the EIA system is one of the instruments at government’s disposal to assist them in achieving this mammoth task. It is then also not surprising that, as observed by Jay et al. (Citation2007), the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development are increasingly being adopted as the fundamental goals of EIA, although the attainment of these goals through EIA remains a challenge (Morrison-Saunders and Retief Citation2012).

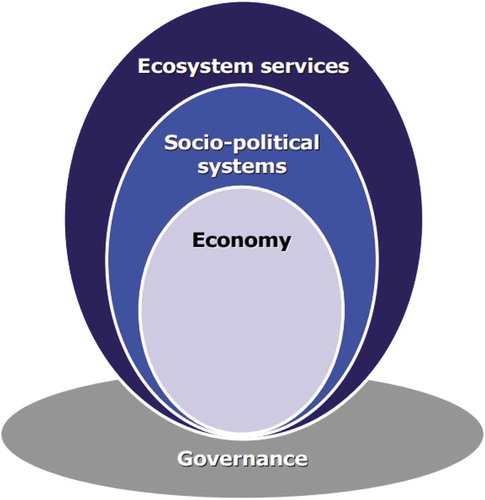

In South Africa, the concept of sustainable development is prioritised and promoted through various legislative provisions (also those underpinning the EIA system). Moreover, sustainable development has been defined and conceptualised in the NFSD (Citation2008) as comprising the integration of four systems, namely: i) ecosystem-services system, ii) the sociopolitical system, iii) the economic system and iv) the governance system. In this conceptualisation of sustainable development both the sociopolitical and economic systems are nested and/or embedded in, and dependent on, the ecosystem-services system (which includes all biophysical features underlying ecosystem services), while all three rely and balance on strong governance arrangements. This is also more generally referred to as the ‘nested egg’ model for sustainable development, as illustrated in . We recognise that there are many other conceptualisations of sustainable development (see, e.g. Pope et al. Citation2016), but for this paper, we chose the nested egg model because it formally aligns with the expectations of the South African EIA system. Moreover, regulatory decision-making processes in South Africa, which include EIA, is expected to give effect to the conceptual understanding of sustainable development contained in the NFSD.

Figure 1. The nested-egg model for sustainable development (NFSD Citation2008).

The main EIA benefits related to the four systems identified from the literature are summarised in .

Table 1. Benefits of EIA as discussed in the literature.

This brief summary highlights some of the main benefits of EIA associated with the different systems of the nested egg sustainable development model. It is fully acknowledged that the list is far from exhaustive and that the different benefits are also all interrelated in some way (which is also precisely what the nested egg model denotes). Moreover, the mentioned benefits can also not specifically be ascribed as benefits for government, nor benefits identified by regulators. This would require a purposefully designed methodology in line with the research aim, which is what we describe in the next section.

3. Methodological design

In order to address the aim of the research, a qualitative research method was applied, in the form of semi-structured questionnaires completed by officials working for the EIA regulator in South Africa. The questionnaires were administered anonymously and used open-ended questions through which personal views and opinions could be expressed, while some degree of structure was retained (as recommend by Creswell Citation2014). The following three questions were included in the semi-structured questionnaire posed to the respondents, namely

Question 1 (Q1): In your opinion, what are the potential benefits of EIA for government?

Question 2 (Q2): In your experience, what are the actual realised benefits of EIA for government?

Question 3 (Q3): In your opinion, what must happen in order to bridge the gap between potential and realised benefits successfully (if a gap exists)?

Ultimately, questionnaires were completed by 175 respondents, which represents almost a third of the total of approximately 600 EIA government officials employed by the South African EIA regulator. The sample of 175 officials is further considered to be statistically representative of the population of approximately 600 at the 95% confidence interval. The questionnaires were administered and completed during compulsory week-long EIA training workshops offered in three locations in 2017, namely: Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth, and Durban. The following five steps were followed:

Completion of questionnaires: Questionnaires were handed out during the first day of the training and respondents had to complete them by hand. Specific time allocation of 45 minutes was allowed for the completion of the questionnaire. It was recognised that some of the responses might be prone to bias since the questions basically required the respondents to indirectly evaluate their own performance as regulators (Holbrook et al. Citation2003). An effort was made to address this potential bias by administrating the questionnaire on an anonymous basis prior to the training event and encouraging respondents to provide honest, considered responses.

Transcribing of responses: All responses were transcribed verbatim to an MS Word format and then transferred to the ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software for content analysis and coding. ATLAS.ti is a widely used qualitative data management and analysis software suitable for the type of data analysis required for this research.

Coding: Coding is the systematic process of assigning a label or code to a relevant piece of data. In this case, phrases/words mentioned by respondents were used to structure the data and develop codes (after Friese Citation2014; Saldaňa Citation2015).

Specialist workshops: Codes were continually interpreted and refined through specialist workshops with a combined timeframe of around 3 days. These workshops involved five seasoned EIA specialists and academics with more than 50 years of combined experience. A total of 12 codes were eventually identified through this process. The possibility of misinterpretation of responses due to the fact that the data were not collected in a face-to-face interview was also addressed through the specialist workshops where joint consideration and interpretation could be provided to the responses (as also recommended by Cranny and Doherty Citation1988).

Linking and classifying codes to the conceptual nested egg model: Each of the 12 codes were then linked by the specialists to one of the systems that make up the nested egg model. In one case, a code could be linked to all four of the systems and was subsequently treated as an ‘overarching’ code. The responses across different codes and questions were finally classified into six classes based on the frequency of mentions, as shown in .

Table 2. Classification of responses.

4. Results and discussion

The 12 benefit codes descriptions and the frequency at which they were raised by respondents are summarised in . Frequencies are classified as very high (VH), high (H), medium (M), low (L), very low (VL), and none (N), as explained in . The main results for each system will now be discussed.

Table 3. Summary of response frequency classification against identified codes.

4.1 The benefits of EIA in relation to ecosystem services

Protection of biodiversity and sensitive environmental features was the only benefit code linked to the ecosystem services system. As shown in , a high percentage of responses (45–60%) cited the protection of biodiversity and sensitive environmental features as a perceived potential benefit of EIA for government. Words such as ‘conserve’, ‘protect’, and ‘preserve’ were also often used by respondents to describe the potential benefit of EIA for government. Although most respondents argued that EIA could contribute to the achievement of sustainable development goals ‘by making sure that the environment is protected’ through the enforcement of ‘strict measures … for a development’, some respondents stated that EIA could also assist government in ‘preserving the environment for future generations’. It was also noted in some responses that EIA can potentially promote government’s ‘understanding of the environment’ through the gathering of new information, and through new insights gained from specialist studies. It was further argued that this new information could assist government in ‘identifying “no-go” areas’ where no development should be allowed.

In terms of realised benefits, the protection of biodiversity and sensitive environmental features also received a high-frequency classification. Many respondents felt that EIA is succeeding in assisting government with ‘the preservation of sensitive habitats and species, and their associated ecosystem goods and services’. The aforementioned is perceived to be achieved through EIAs' ability to minimise the potential impacts of activities and its ability to steer developments away from sensitive environmental features towards areas with less sensitive features and ‘where the impacts on these features would be less’ and the ‘carrying capacity of the environment would not be exceeded’. In this sense, EIA, akin to its name, has the ability to assist government (especially those responsible for EIA review and decision-making) in the informed review of assessed impacts (both positive and negative) of proposed developments on the receiving environment, and proposing mitigation measures where applicable, aligning with the general benefits discussed by authors such as Oosterhuis (Citation2007) and Bond et al. (Citation2014). The notion that EIA can promote governments’ understanding of the environment was also confirmed as a realised benefit, as it was acknowledged by some participants that EIA not only generates new information but also confirms existing information through ground-truthing conducted as part of specialist studies.

None of the respondents provided insights into the bridging of the gap between potential and realised benefits in relation to ecosystem services. This might be because most respondents held the view that EIA was already achieving these potential benefits and that no real gap existed, although this was not explicitly communicated in any of the responses. It, therefore, seems evident from the responses that EIA is perceived by a significant percentage of EIA officials employed by the regulators, to contribute to the protection of the biophysical environment and its associated ecosystem services.

4.2 The benefits of EIA in relation to the sociopolitical system

Two codes could be linked to the sociopolitical system, namely: giving effect to the environmental right and environmental education, capacity building and awareness. A relatively average percentage of responses (30–45%) stated that EIA has the potential to assist Government in achieving its mandate of giving effect to the environmental right as stipulated in Section 24 of the Constitution of South Africa. The environmental right stipulates that all South African citizens have the right

to an environment that is not harmful to their health or wellbeing; and to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures that … secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development. (South Africa Citation1996)

Furthermore, very few respondents (<15%) viewed this mandate as being realised through EIA, and no mention was made as to how this gap might be bridged. It seems that the expectation that EIA can give effect to this right is considered less important and even unrealistic which then also explain why EIA is not perceived as achieving this benefit. It was, however, noted by some that EIA promotes the idea of ‘people-centered governance’ by ‘ensuring that the rights and views of citizens are heard’ during development processes. It this sense, EIA is seen as a mechanism through which the public can ‘communicate their social and economic needs to government’. EIA finally also contributes to a better understanding of the socioeconomic context of an area and the manner and extent to which it might be impacted by proposed activities.

Another benefit of EIA that was mentioned, albeit with a very low frequency (<15%), was that of environmental education, capacity building and awareness. It was argued by some that EIA provides Government with the opportunity ‘to promote environmental education around environmental laws in the country’ and also to ‘raise awareness on environmental issues’. Although both the potential and realisation of this benefit received a very low frequency, it received a very high frequency in terms of suggestions on how the gap could be bridged (>60%). This discrepancy could be because most of the suggestions made relate to the improvement of the EIA system and its implementation through the use of mechanisms such as education, capacity building, and the raising of awareness, i.e., as a means to an end. It was stated that ‘Everyone – developers and community members – must be well educated on the importance of the environment and made aware of the impacts that developments might have on it’. It was argued by many that it is government’s responsibility to raise awareness and educate people on these issues through the development of ‘proper awareness and education programs’. It was further stated that government should invest in its Environmental Officers by ensuring that they have adequate training and that the necessary capacity exists to ensure the enforcement of EIA.

4.3 The benefits of EIA in relation to the economic system

The only benefit that could clearly be linked to the economic system was promotes sustainable economic development. A high percentage of respondents (45–60%) stated that EIA has the potential to promote sustainable economic development, especially through job creation. Although many of the job opportunities discussed by respondents could be linked to the development project rather than the EIA process itself, it was argued that the EIA process has the ability to ensure that projects employ at least some locally sourced labour for both part-time and full-time employment. Interestingly enough, no mention was made towards the long-term economic sustainability in terms of the operational and post decommissioning phases of projects, which suggest quite a short-term outlook by regulators in terms of job creation. However, the ability of EIA to ‘ensure that developments are carefully planned and the risk of externalised costs reduced’, essentially acting as an early warning system through which unfeasible and possibly costly projects could be flagged and altered, or possibly even cancelled, was mentioned by some as a potential benefit. It was argued that these costs are eventually borne by the public and ultimately by government and that EIA can potentially help manage this risk. It was also stated by some respondents that EIA can be regarded as a potential source of revenue for government as ‘government is generating income through EIA application fees’. However, in terms of broader economic development, this contribution would seem negligible.

In terms of realised benefits, an average percentage of respondents (30–45%) agreed that EIA does contribute to economic development and that many of the potential benefits discussed above are in fact being realised through EIA. Government income generated through EIA and job creation was cited as the most important of these realised benefits. Some respondents, however, also pointed out certain ways in which EIA could potentially be hampering sustainable economic development. EIA timeframes and its effect on development projects were cited as a potential issue and a ‘reduction of EIA timeframes and streamlining the EIA process’ was called for.

4.4 The benefits of EIA in relation to governance

The majority of codes (seven) were linked to the governance system, which could be expected as EIA is fundamentally a governance instrument and the questionnaires tested the perceptions of government officials about EIA benefits to government. The five most discussed governance benefit codes were legal compliance and enforcement, dealing with positive and negative impacts, transparency and accountability in decision-making, public participation process and cooperative governance. These five codes will be discussed in more detail, and the other codes reflected on briefly.

A very high frequency of respondents (>60%) stated that EIA has the potential to promote legal compliance and enforcement, a benefit that has also been widely discussed in the literature (Marshall Citation2005; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013; Wessels et al. Citation2015; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). Respondents were of the view that EIA ‘empowers government to regulate development’ and can potentially ‘ensure that developments are lawful and not compromising to the environment’. It was, however, noted by an average percentage (30–44%) of respondents that this benefit is not being fully achieved for various reasons such as government does not have adequate capacity to effectively enforce compliance of legal provisions and conditions and to conduct the necessary monitoring. It was further noted that conditions set by government are often not practically feasible, further complicating their enforcement. In terms of the regulating of activities, respondents argued that the ‘refusal of environmental authorisations should, when applicable, be promoted and not avoided’ while ‘stronger penalties should be awarded in cases of non-compliance’.

In terms of dealing with positive and negative impacts, a high percentage of the respondents (45–60%) were of the view that ‘EIA is the most effective tool that the government can use to identify and assess impacts’. The ability of EIA to identify and assess potential impacts and propose possible mitigation measures and design alternatives, in cases where they cannot be avoided, were seen as key potential benefits. It was also argued by some respondents that apart from managing negative impacts, EIA also has the ability to ‘enhance the positive impacts’ of development, i.e. optimising and enhancing developments. A low frequency of responses (15–29%), however, suggested that these benefits were not always adequately achieved in practice, implying that there is either uncertainty in the system or uncertainty amongst regulators as to how it should be achieved.

A high frequency of responses (45–60%) acknowledged the potential of EIA to promote transparency and accountability in decision-making, through well-informed, and fair decision-making that is in the best interest of society (Oosterhuis Citation2007; Lastarnau et al. Citation2011; Morgan Citation2012; Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2014). The fact that all documentation related to a decision should be available in the public domain was viewed to support transparency and accountability in decision-making. It was argued that through transparency and accountability, EIA also ‘increases public confidence and support in government’ in general. It was, however, noted that relatively few responses (15–29%) viewed transparent and accountable decision-making as a realised benefit of EIA.

Contributing to transparency and accountability in decision-making is the public participation process associated with EIA, which received an average frequency of responses (30–44%) as a potential benefit of EIA. It was contended that the EIA process promotes the concept of ‘people-centred governance – ensuring that the rights and views of citizens are heard’. It was also noted that the process ensures that government is made aware of potential issues affecting local communities and that their concerns are heard. The EIA process further encourages affected parties to engage and become involved in their community, i.e. it promotes an active civil society. It was the experience of many of the respondents, however, that ‘the turnout at public participation meetings are usually very low’, which negatively affected the process. Another concern was the manner in which public participation was facilitated, and some respondents stated that public engagement was not appropriate and/or adequate.

Another potential perceived benefit of EIA mentioned by a low frequency of responses (15–29%) was that of cooperative governance. As this was not regarded as a realised benefit (very low response), respondents called for better alignment between the different spheres of Government with some respondents also calling for alignment of legislation and the development of a consolidated environmental management system. Although this exists in principle, it seems as if it is not being realised in practice, resulting in a de jure vs de facto situation, and suggesting a failure to implement by governments. The need for better and more collaboration between different government departments was mentioned at an average frequency (30–44%), suggesting possible frustration amongst officials in this regard.

It was further noted that EIA could assist in giving effect to policy and planning although it was raised at low frequency (15–29%), and therefore not regarded as a key potential or realised benefit. Ideally, strategic plans and policies should be considered during the EIA process and their objectives and guidelines adhered to. In this manner, EIA will assist in the implementation of these plans and policies. A final benefit of EIA in relation to governance mentioned by a very low frequency of responses (>15%) was EIAs ability to assist government in dealing with trade-offs. Although some respondents argued that ‘EIA ensures that a balance is struck between the environment and development’, the very low frequency at which trade-offs were discussed suggests that it is not seen as an important potential benefit of EIA for government.

4.5 Overarching benefits

Due to the strong link between EIA and the aim of sustainable development, it was expected that many respondents would view EIA’s potential contribution towards sustainable development as a key perceived benefit. Because the concept of sustainable development incorporates all four systems discussed up to now, the sustainable development code is treated as an overarching benefit. A high frequency of responses (45–60%) stated that EIA could assist government in its task of achieving sustainable development, although very few provided any detail on how this would transpire. One participant did, however, state that ‘through the EIA process, government is able to guide development and ensure adherence to the prescribed rules to ensure sustainable development’. How exactly sustainable development was understood by participants, and the extent to which their understanding related to the nested egg model, could, however, not be determined from the data. Although many respondents considered this to be a potential benefit of EIA, few (15–29%) actually acknowledged it as a realised benefit. It could be argued that this outcome is similar to the outcome for the giving effect to the environmental right code discussed earlier, i.e., an unrealistic expectation of EIA.

5. Conclusion

This paper explores the benefits of EIA for government as perceived by EIA regulators. These benefits are conceptualised against the nested egg model of sustainable development. Although the research was conducted within the South African context, we would argue that the results contribute to a broader understanding of the benefits of EIA for government. The following key learning points are distilled from the research results, namely:

The research results show that regulators support the perceived potential benefits that EIA should achieve the realisation of Section 24 environmental right and promote sustainable development within the South African context. However, it is acknowledged that EIA does not currently realise these benefits. This could be explained by the perceived unimportance of other key benefits, such as dealing with trade-offs, the realisation of cooperative governance, and giving effect to policy and planning. The latter benefits represent critical prerequisites for the promotion of sustainable development.

In terms of potential benefits, respondents specifically indicated realisation of short-term, project-level benefits for government, such as the protection of biodiversity, public participation, legal compliance, and enforcement, as well as certain immediate economic benefits associated with EIA. These perceived benefits align with benefits discussed in the literature () and reflect what EIA as a project-level policy implementation instrument can reasonably be expected to deliver.

The research results suggest that the regulator is of the view that the contribution EIA can make in terms of broader sustainable development seems far less than what is typically prescribed and expected from a legal and policy perspective. The regulator seems to rather support EIA as an instrument for the avoidance of biophysical impacts and environmental protection (which the regulators perceive as being achieved). This goes against the general trend in the EIA literature which recommends an extended sustainability mandate.

In conclusion, the perceived realised benefits of EIA for government seem to reflect back to the origins of EIA, acknowledging the project level nature of EIA and a relatively narrow mandate in support of environmental protection. Therefore, although an expectation has been created around delivering on sustainable development and environmental rights, regulators seem less optimistic in terms of the ability of EIA to deliver on these. Therefore, although the extended sustainability mandate seems novel, it might be overly ambitious and even misdirected. Maybe the potential benefits of EIA for government need to be reconsidered and realigned with its more practical and focussed historical roots. Having a more clearly defined purpose might make it easier to demonstrate the benefits of EIA for government, and also show that these benefits are being achieved. Regardless, future research should continue to explore the benefits of EIA within different contexts and from different perspectives. This will be important to expand our understanding on the benefits of EIA in general.

References

- Arts J, Runhaar HA, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, Laerhoven FV, Driessen PP, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Man. 14(4):1–40.

- Baker DC, McLelland JN. 2003. Evaluating the effectiveness of British Columbia’s environmental assessment process for first nations’ participation in mining development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(5):581–603. doi:10.1016/S0195-9255(03)00093-3.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R. 2013. Chapter 8: framework for comparing and evaluating sustainability assessment practice. In: Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Howitt R, editors. Sustainability assessment: pluralism, practice and progress. London: Taylor and Francis; p. 117–131.

- Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Pope J. 2012. Sustainability assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):53–62.

- Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F, Gunn J. 2014. Impact assessment: eroding benefits through streamlining? Environ Impact Assess. 45:46–53. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.12.002

- Bond A, Pope J, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A, Fundingsland M, Hauptfleisch M. 2020. Explaining the political nature of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): a neo-Gramscian perspective’. J Clean Prod. 244:1–10.

- Canelas L. 1989. First environmental impact assessment of a highway in Portugal: repercussions of the European economic community directive. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 9:391–397.

- Cape L, Retief F, Lochner P, Bond A, Fischer T. 2018. Exploring pluralism – different stakeholder views of the expected and realised value of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Environ Impact Assess Rev. 69:32–41.

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 22(4):295–310. doi:10.3152/147154604781765860.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess. 43:65–72. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2013.05.006

- Christensen P, Kørnøv L, Nielsen EH. 2005. EIA as regulation: does it work? J Environ Plann Man. 48(3):393–412. doi:10.1080/09640560500067491.

- Cranny CJ, Doherty ME. 1988. Importance ratings in job analysis: note on the misinterpretation of factor analyses. J Appl Psychol. 73(2):320.

- Creswell JW. 2014. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Devuyst D. 2000. Linking impact assessment and sustainable development at the local level: the introduction of sustainability assessment systems. Sustainable Dev. 8(2):67–78.

- Drayson K, Wood G, Thompson S. 2017. An evaluation of ecological impact assessment procedural effectiveness over time. Environ Sci Policy. 70:54–66.

- Fischer TB. 1999. Benefits from SEA application - a comparative review of North West England, Noord-Holland and EVR Brandenburg-Berlin. EIA Rev. 19(2):143–173.

- Fischer TB, He X. 2009. Differences in perceptions of effective strategic environmental assessment application in the UK and China. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 11(4):471–485.

- Friese S. 2014. Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS. Sage. ti. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Garner JF, O’Riordan T. 1982. Environmental impact assessment in the context of economic recession. Geogr J. 148(3):343–355.

- Glasson J, Therivel R, Chadwick A. 2013. Introduction to environmental impact assessment. Oxan: Routledge.

- Hacking T. 2018. The SDGs and the sustainability assessment of private sector projects: theoretical conceptualisation and comparison with current practice using the case study of the Asian development bank. Impact Assess Project. 37(1):2–16.

- Hacking T, Guthrie PM. 2008. A framework for clarifying the meaning of triple bottom-line, integrated, and sustainability assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28(2–3):73–89.

- Holbrook AL, Green MC, Krosnick JA. 2003. Telephone versus face-to-face interviewing of national probability samples with long questionnaires: comparisons of respondent satisficing and social desirability response bias. Public Opin Q. 67(1):79–125.

- Jay S, Jones C, Slinn P, Wood C. 2007. Environmental impact assessment: retrospect and prospect. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 27(4):287–300.

- Kidd M, Retief F, Alberts R. 2018. Integrated environmental impact assessment and management. In: King N, Strydom H, Retief F, editors. Environmental management in South Africa. 3rd ed. Cape Town: Juta Publishing; p. 1213–1357.

- Klaffl I, Haslinger N, Haslinger P 2006. UVP-Evaluation. Evaluation der Umweltverträglich-keitsprüfung in Österreich. Report REP-0036, Umweltbunde-samt, Vienna. http://www.umweltbundesamt.at/filead-min/site/publikationen/REP0036.pdf

- Lastarnau C, Oyarzún J, Maturana H, Soto G, Señore M, Soto M, Rötting TS, Amezaga JM, Oyarzún R. 2011. Stakeholder participation within the public environmental system in Chile: major gaps between theory and practice. Environ Manag. 92(10):2470–2478.

- Loomis JJ, Dziedzic M. 2018. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness: A state of the art. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:29–37. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2017.10.005

- Marshall R. 2005. Environmental impact assessment follow-up and its benefits for industry.Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 23(3):191–196. doi:10.3152/147154605781765571.

- Martínez-Mesa J, González-Chica DA, Duquia RP, Bonamigo RR, Bastos JL. 2016. Sampling: how to select participants in my research study? Anais Brasileiros De Dermatologia. 91(3):326–330.

- Morgan R. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project. 30(1):5–14.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Bond A, Pope J, Retief F. 2015. Demonstrating the benefits of impact assessment for proponents. Impact Assess Project. 33(2):108–115. doi:10.1080/14615517.2014.981049.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Pope J, Gunn JA, Bond A, Retief F. 2014. Strengthening impact assessment: a call for integration and focus. Impact Assess Project. 32(1):2–8.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2012. Walking the sustainability assessment talk — progressing the practice of environmental impact assessment (EIA). Environ Impact Assess Rev. 36:34–41. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2012.04.001

- NFSD. 2008 July. A national framework for sustainable development in South Africa

- Nooteboom S. 2000. Environmental assessments of strategic decisions and project decisions: interactions and benefits. Impact Assess Project. 18(2):151–160.

- O’Riordan T. 1982. Environmental issues. Prog Geog. 6(3):409–424.

- Oosterhuis F 2007. Costs and benefits of the EIA directive. [accessed 2020 Feb 26]. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eia/pdf/Costs and benefits of the EIA Directive.pdf

- Ortolano L, Shepherd A. 1995. Environmental impact assessment: challenges and opportunities. Impact Assess. 13(1):3–30. doi:10.1080/07349165.1995.9726076.

- Peterson K. 2010. Quality of environmental impact statements and variability of scrutiny by reviewers. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30:169–176.

- Petts J. 1999. Public participation and environmental impact assessment. In: Petts J, editor. Handbook of environmental impact assessment - Vol.1 environmental impact assessment: process, methods and potential. Oxford: Blackwell Science; p. 145–177.

- Piper JM. 2000. Cumulative effects assessment on the middle humber: barriers overcome, benefits derived. J Environ Plann Man. 43(3):369–387. doi:10.1080/09640560050010400.

- Pope J, Bond A, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2013. Advancing the theory and practice of impact assessment: setting the research agenda. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 41:1–9.

- Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Huge J, Bond A. 2016. Reconceptualising sustainability assessment. EIA Rev. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2016.11.002

- Radnai A, Mondok Z. 2000. Environmental impact assessment implementation in Hungary. In: Bellinger E, George C, Lee N, Paduret A, editors. Environmental assessment in countries in transition. Budapest: CEU Press; p. 57–62.

- Retief F. 2010. The evolution of environmental assessment debates: critical perspectives from South Africa. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 12(4):375–397.

- Retief F, Chabalala B. 2009. The cost of environmental impact assessment (EIA) in South Africa. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 11:51–68. doi:10.1142/S1464333209003257

- Retief F, Jones C, Jay S. 2007. The status and extent of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) practice in South Africa – 1996–2003. South Afr Geog J. 89(1):44–54.

- Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A, Geneletti D, Pope J. 2013. Exploring the psychology of trade-off decision-making in environmental impact assessment. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 31(1):13–23. doi:10.1080/14615517.2013.768007.

- Sadler B 1996. International Study of the Effectiveness of Environmental Assessment Final Report - Environmental Assessment in a Changing World: Evaluating Practice to Improve Performance. (Minister of Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa).

- Saldaña J. 2015. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- South Africa. 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, act 108 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Press.

- Stinchcombe K, Gibson RB. 2001. Strategic environmental assessment as a means of pursuing sustainability: ten advantages and ten challenges. J Environ Assess Policy Manag. 3(3):343–372. doi:10.1142/S1464333201000741.

- Wang H, Bai H, Jia L, He X. 2012. Measurement indicators and an evaluation approach for assessing strategic environmental assessment effectiveness. Ecol Indic. 23:413–420. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.04.021

- Wessels JA, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2015. Appraising the value of independent EIA follow-up verifiers. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:178–189. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2014.10.004

- Wilkins H. 2003. The need for subjectivity in EIA: discourse as a tool for sustainable development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(4):401–414.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: a comparative review. 2nd ed. Harlow (UK): Pearson.

- Wood C, Jones JE. 1997. The effect of environmental assessment on UK local planning authority decisions. Urban Stud. 34:1237–1257. doi:10.1080/0042098975619

- Wood G, Glasson J, Becker J. 2006. EIA scoping in England and Wales: practitioner approaches, perspectives and constraints. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26(3):221–241. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2005.02.001.