ABSTRACT

Whether or not reduction of natural capital should be a focus in assessing relocation policies is addressed by investigating a resettlement project for disaster prevention (also for poverty alleviation) in Baihe County in western China. Using multiple linear regression, the associations between livelihood assets (including natural capital) and the acceptance of relocation policies are examined. Two index systems are employed to measure resettlers’ livelihoods and policy acceptance. Livelihood assets are shown to have a positive relationship with resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies. Of the five indicators of livelihood assets, higher physical, social, human and financial capital correlate with increased policy acceptance, while natural capital does not. This suggests that reducing or losing natural resources does not necessarily increase the risk of impoverishment in the process of resettlement. Land-based resettlement could be an option but is not indispensable for the livelihood maintenance of resettlers.

Introduction

In previous studies, displacement and resettlement are shown to have many negative consequences. Many resettlements reduced resettlers’ natural resources and brought them more poverty (de Sherbinin et al. Citation2011; Bang and Few Citation2012; Vaz-Jones Citation2018). The mental health of some relocatees, especially older rural people, deteriorated due to their inability to adapt to new environments (Snodgrass et al. Citation2016). Their habits and lifestyles including diet, physical exercise, smoking, and drinking, were forced to change by relocation, which may have led to mental health problems (Hasegawa et al. Citation2016). Such displacements may also disrupt established social networks or cultural links, and therefore collapse the original social structure. It was reported that resettlers moving from rural to urban areas became marginalized due to their disadvantage in social capital (Bott et al., Citation2019; Bang and Few Citation2012), and some were discriminated against in their new communities (Murray Citation2010; Sridarran et al. Citation2018).

Natural capital is the basis of livelihood and production in rural areas (Patel & Mandhyan Citation2014); examples are farmland for farmers, grazing land for herders, forest land for orchard growers. Among the negative consequences of resettlement, landlessness is the first livelihood risk for resettlers, because it may damage the foundation of their production systems and expose them to risk of impoverishment when they lose their jobs (Cernea and Schmidt-Soltau Citation2006; Magembe-Mushi Citation2018; Wilson Citation2019). Moreover, due to lack or restriction of access to natural resources after relocation, some aspects of human well-being, such as obtaining food by harvesting wild plants or hunting wildlife, collecting natural materials or biofuels, enjoyment of nature, and serving tourists for money in reserves or protected areas, could be greatly diminished (Karanth et al. Citation2018; Naidoo et al. Citation2019).

Therefore, land-based resettlement and natural capital assessment have become important considerations for relocation projects. In assessing resettlers’ livelihoods, impoverishment risk, satisfaction, and change in natural capital are usually regarded as the key indicators. There is no doubt that any reduction of assets is harmful for resettlers, who tend to have low levels of satisfaction (e.g. Danquah et al. Citation2014; Li et al. Citation2018). As a result, reduction of natural capital caused by displacement and resettlement might decrease people’s satisfaction with the policies of relocation.

Mainstream models such as the sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) and the impoverishment risk and reconstruction (IRR) model, take natural capital as one of the most important assets in evaluating the quality of livelihoods, future impoverishment risk, satisfaction and happiness, and policy performance. SLF was developed by the UK’s DFID (Department for International Development) for the evaluation of livelihood quality in terms of natural, social, human, physical, and financial capital. This framework is used to evaluate whether rural households can achieve sustainable livelihoods with their resource bases (Scoone Citation1998; Apine et al. Citation2019), and is helpful in shifting the focus from development to poverty reduction (Mensah Citation2012). Some components of resettlement projects may create new poverty; as a result, SLF is widely used to assess livelihood challenges as well as the quality of relocation policies (Liu et al. Citation2018; Sina et al. Citation2019). IRR theory provides a framework for assessing risks and risk avoidance in resettlement. The primary risk that the IRR model addresses is landlessness, and this model favored a poverty-alleviation strategy of land-based resettlement (Cernea and McDowell Citation2000; Cernea Citation2000, Citation2007). However, the SLF and IRR models may not be appropriate because they don’t take into account trends in urbanization (a general definition of townization, urbanization, and metropolitanization, which includes farmers moving to small towns) and capitalization (Xiao et al. Citation2018).

Natural capital such as farmland, forest land, grazing land, and water supplies are usually reduced in the process of displacement and resettlement (Smyth et al. Citation2015). Therefore, natural products and farm revenues also decrease in this process. This has happened in many cases, such as the displacement for the Three Gorges Dam Project (Wilmsen Citation2018), the displacement for disaster prevention in southern Shaanxi province, China (Li et al. Citation2018), the resettlement programme in northwestern Vietnam (Bui and Schreinemachers Citation2011), as well as the resettlement in the Keta Sea Defense Project in Ghana (Danquah et al. Citation2014). Part of the reason is that finding land available for land-for-land replacement becomes increasingly difficult (Smyth et al. Citation2015), because of the worldwide trend towards urbanization (Zlotnik Citation2017). In addition, social and economic inequality result in violations of land rights in many forced displacements (Wayessa and Nygren Citation2016).

Different households have their own abilities to access different resources (Serrat Citation2017), so the resources that resettlers actually need may vary. Reduction of land size and related production may not necessarily result in worse livelihoods in resettlements. A report on a relocation project in Vietnam showed that the net income of resettlers did not change significantly after relocation, even though the farm revenues of the resettled households fell dramatically due to the loss of farmland, because they were partially compensated through land-use intensification (Bui and Schreinemachers Citation2011). Most relocations happen during the process of urbanization, which turns farmers into non-agricultural citizens by providing alternative compensation for their land reduction in the form of money or houses (Xiao et al. Citation2018; Wilmsen Citation2018). Moreover, farm labor is not paid well in some countries, and household income may increase after the surplus labor is released from farmland. Previous studies have shown that resettlers received most of their revenues from non-farm activities (Nguyen et al. Citation2017; Li et al. Citation2018). Many resettlers tried to migrate from rural areas to work in urban areas after relocation (Li et al. Citation2018).

Natural capital compensation commonly falls short of resettlers’ expectations (Smyth et al. Citation2015). In some cases, even though the resettlers felt good about the relocation and were confident in the future, they were still dissatisfied with the reduction in natural assets (Bao and Peng Citation2016; Li et al. Citation2018). In light of this inconsistency, the question remains as to whether natural capital is essential for the resettlers’ livelihood and the assessment of relocation policies. Little empirical evidence has been provided to challenge traditional thinking about land-based resettlements, and to test the applicability of widely-used livelihood models concerning natural capital in the face of trends towards urbanization and capitalization.

Study contexts and methods

Study area

Baihe County (Please refer to its location in the study of Xiao et al. (Citation2018)) has a total area of approximately 1,477 km2 and a population of 215,200. The primary crops in this area include wheat, maize, potato, rice, bean, and vegetables. The cultivation of papaya, oil peony, tea, and some traditional Chinese medicinal crops provides auxiliary revenues. Forest products are also a small part of family income in these rural areas, and farmers also raise pigs, buffaloes, sheep, and silkworms. There is a conflict between the traditional agricultural society and modern urbanization in Baihe County, and in order to look for well-paid jobs, many young people have migrated from rural to urban areas.

This mountainous county is seriously affected by natural disasters. The local government documented 281 geological hazard sites in the county, including 258 landslide sites, eleven debris flow sites, and twelve collapse sites in 2011. Moreover, its rural residents are relatively poor with only 616 USD per capita net income in 2010, far less than the national average of 1,080 USD. Even though they benefited from China’s economic growth (rural residents’ income rose to 1,408 USD in 2018), the poverty gap still needs to be filled (the national average is 2,066 USD). Therefore, when the government of Shaanxi province, which oversees Baihe County, decided to operate a large resettlement project for disaster prevention combined with poverty-alleviation in May 2011, Baihe County was deemed as the key area for the program.

Household survey

The data in this study are from a survey of resettlers from three towns – Songjia, Cangshang, and Lengshui – in Baihe County. These towns were selected from all twelve towns in the county, which are required to have large concentrated relocation communities, because collective relocation is the dominant pattern of resettlement. With the assistance of the local government, 605 households were surveyed using a classified random sampling method, and 596 samples were retained. The characteristics of the surveyed samples are shown in . The respondents were mainly from low-income families, and most of them were the primary labor force for their families and had not received much education.

Table 1. Characteristics of Respondents

Statistical methods

Research framework

To evaluate the role of natural capital compensation in displacement and resettlement, we designed the research framework shown in . which depicts resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies according to their livelihoods (including natural capital). Two index systems were employed: one for the assessment of livelihoods, and the other for the assessment of policy acceptance. Resettlers’ livelihoods were measured in terms of five capitals: natural, human, social, physical, and financial capital, based on the SLF model. Using consumer satisfaction theory, policy acceptance was measured in terms of the perception of compensation, supports, infrastructure, and safety of the relocation policies.

Our research framework was inspired by the work of Serrat (Citation2017), which demonstrated that policy-determining structures affect livelihoods. The present study explores how livelihood assets affect policy acceptance in the resettlement context. There are six theoretical assumptions shown as .

(1) More livelihood assets increase resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies;

(2) More natural capital increases resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies;

(3) More human capital increases resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies;

(4) More social capital increases resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies;

(5) More physical capital increases resettlers’ acceptance of relocation policies;

(6) More financial capital increases resettlers’ acceptance of relocationg policies.

Index system for livelihood assessment

SLF was employed to assess the livelihood assets of resettlers. The indicators for each type of capital were selected from the initial descriptions of SLF shown in . A five-point Likert scale was used to score the respondents’ feelings concerning each livelihood indicator after relocation, with the answers: 1 = extremely low, 2 low, 3 moderate, 4 high, and 5 extremely high.

Table 2. Index System for Livelihood Assessment

Index system for policy acceptance assessment

Based on the theory of consumer satisfaction, an index system for relocation policy acceptance was constructed from resettlers’ perceptions. Consumer satisfaction was introduced to evaluate performance in the private sector, and was quickly accepted by public sectors for assessment of public services or public policies (e.g. Johnson et al. Citation2002; Van Ryzin et al. Citation2004; Collins et al. Citation2019). It has also been employed to investigate resettlers’ perceptions of relocation policies (e.g. Danquah et al. Citation2014; Yu et al. Citation2016).

Part of the index system of policy acceptance concerns consumer satisfaction. Fornell et al. (Citation1996) found that consumer satisfaction was more quality-driven than value-driven or price-driven, but resettlers’ perceptions focus on all of these. Resettlers usually hope that the government will run high-quality services during their displacement and resettlement, and that they can live in a new place with good security, infrastructure, and environment. They care a lot about the compensation, especially the price of relocated houses. Also, their requirements for education, training, and employment should not be underestimated. Therefore, we designed indicators of policy acceptance with the three components shown in . The satisfaction level of the indicators was assessed by a five-point Likert scale with 1 = extremely low, 2 = low, 3 = moderate, 4 = high, and 5 = extremely high.

Table 3. Index System on Acceptance of Relocating Policy

In , Cronbach’s alphas for the three sub-scales of safety, preparation, and satisfaction are all above 0.7, and the value for the whole scale is 0.87, indicating that the scale has a high reliability. Moreover, all the standardized factor loadings are above 0.6, and their values for KMO are greater than 0.7. Bartlett’s test of sphericity also validates our factor analysis. The results show that the scale has good discriminatory and structural validity. Since the three factors contribute unevenly to acceptance, the indicators were weighted following the method of A. J. Kee. The weights for ‘Satisfaction’, ‘Preparation’ and ‘Safety’ are 0.5, 0.25 and 0.25 respectively, and the acceptance of relocation policy is calculated by summing.

Results

Evaluation of livelihood

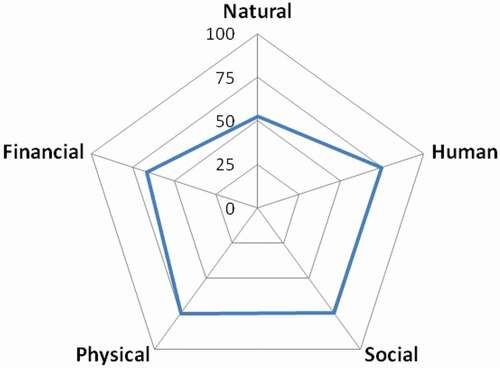

shows that the livelihoods of resettlers have improved in general but the distributions of the five components vary. The indicator value of natural capital, 53, is far less than the other four capitals – human, 75, social, 74, physical, 75, and financial, 66.

Figure 2. Livelihood Assets of the Resettlers Calculated by SLF

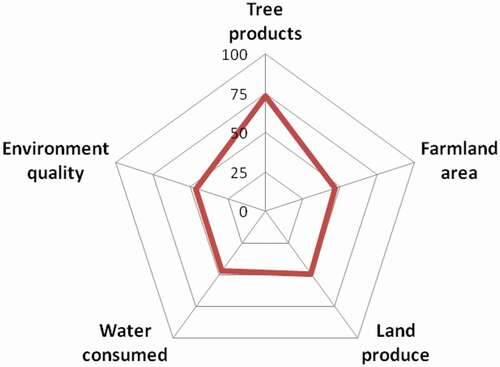

We found that the natural capital of the resettlers in Baihe County has been dramatically reduced. Taking farmland area for example, most respondents (63.2%) self-reported that their farmland areas were reduced after relocation, only 24.5% were not sure and 10.6% reported an increase. For the five specific indicators of natural capital (as shown in ), though the indicator value of tree products was 74, the indicators of farmland area, land produce, water consumed, and environmental quality had very low values, 47, 49, 47, and 46, respectively.

Figure 3. Natural Capital of the Resettlers Described by Five Indicators

Social capital was assessed by the indicators of kinship contacts, making friends, relations of trust, available support, and convenience of participating in community decision-making, which range from 72 to 75. There are no signs that resettlers became marginalized after relocation as has been claimed in previous studies. Our findings may be attributed to the resettlement modes in Baihe County. There are four available relocating modes in the project: (1) independently scattered relocation, (2) move to town or urban area and be relocated together, (3) rebuild new villages based on the original villages, and (4) merge or append original small villages to a bigger one. More than 72.44% of households chose the last two modes, so that they could retain most of their social networks, as well as their traditional way of life.

Both human capital and physical capital have good perceived values. The former was assessed using indicators of health, nutrition, education, pre-training opportunity, and working capacity, and range from 72 to 76. The latter was assessed by indicators of transport infrastructure, secure shelter and buildings, water supply and sanitation, tools and technology, and communication conditions and range from 73 to 77. Both are balanced and quite high. It seems that, relative to their original places, the public environment and services for the resettlers were improved after relocation.

Financial capital of the resettlers was assessed by indicators of savings (70), credit and debt (46), pensions (75), annual income (71), and cash compensation for housing (70). The financial conditions of the resettlers are not bad either, but the indicator of credit and debt is not as good as the others. This may be attributed to the lower credit and shortage of funds in China, which makes it more difficult for resettlers to borrow money.

Evaluation of policy acceptance

Acceptance of the relocation policies is shown in . Attitudes of the resettlers toward to the arrangements of the project varied, but the relocation policies were mainly welcomed.

Figure 4. Acceptance of Relocating Policy

With respect to safety, most respondents had positive perceptions of the changes regarding natural disasters, diseases, and public security cases after relocation (59. 5%, 59.1%, 66.4%), and the proportions with negative feelings about these are small (11.1%, 15.4%, and 10.5%). Regarding preparation, most respondents said that the facilities or conditions surrounding transportation, sanitation, communication, and bank loans were improved after relocation (64.5%, 71.5%, 69.3%, and 64.8%) compared to small fractions with contrary opinions (10.9%, 7.7%, 8.4% and 8.8%). In terms of satisfaction, most were satisfied with house relocation compensation, employment support and pre-job training, management quality of displacement and resettlement, and benefits for the masses (56.9%, 61.4%, 64.8% and 68.1%) compared with those being unsatisfied (12.5%, 11.1%, 11.1%, and 7.5%).

Livelihood and policy acceptance

Correlations among all the variables are shown in . Livelihood assets and its five sub-capitals were significantly correlated with policy acceptance. All had positive associations with acceptance except for natural capital, which was negative. Higher education, annual income and more collective relocation mode, were all positively correlated with acceptance of relocation policy.

Table 4. Correlations between Variables

The Durbin-Watson (DW) statistic was used to test the auto-correlation of the residuals, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to test whether the independent variables have a collinearity problem. DW has a value of 1.7 for the four models, which means that no auto-correlation is detected in the samples (as the value is between 0 and 4). The VIF values of the indicators are less than 4, which, for our sample size of 596, means collinearity is not a problem for our regression analysis.

We ran four linear regression models to explain policy acceptance as shown in . After controlling the demographic variables and relocation mode, the positive effect of livelihood assets on the acceptance of relocation policies was significant, as were those of the sub-capitals – physical, social, human and financial capital. However, natural capital was not significantly correlated with policy acceptance.

Table 5. Statistical Models and Regression Results

Conclusions and discussions

To address whether a reduction in natural capital is essential for resettlers’ livelihoods or relocation policy evaluation, this study assessed livelihood assets and policy acceptance and their relationship by investigating a resettlement project for disaster prevention (also for poverty alleviation) in Baihe County of western China. Our findings extend previous analyses of livelihood assets and policy acceptance of resettlers, and provide an important direction for effective assessment of relocation policy.

It has been suggested in previous studies that natural capital, especially land area, is usually reduced in the process of displacement and resettlement (Bui and Schreinemachers Citation2011; Danquah et al. Citation2014; Smyth et al. Citation2015; Wilmsen Citation2018), and that any reduction of assets is associated with low levels of satisfaction (e.g. Danquah et al. Citation2014; Li et al. Citation2018). Our study confirmed that the natural capital of the resettlers in Baihe County has been dramatically reduced. Among the five indicators of livelihood assets, the value of natural capital was the lowest. However, we also found that the resettlers had relatively good policy acceptance and mainly perceived advantages or benefits from the relocation policies. These findings suggest that most resettlers were satisfied with the relocation policies although their natural capital was reduced during resettlement.

One possible explanation is that the reduced natural capital was compensated by other benefits from the relocation. Reports from the local government partly support this explanation. 594 persons died from natural disasters in southern Shaanxi province during 2000–2010, while after 2011, when the resettlement project operated, the death rate per year decreased to 20%-30% of its original level (LODRP, Citation2015). Concerning poverty alleviation, the annual income of a resettler has risen from 610 USD in 2010 to 1,395 USD in 2015, and 410,000 people have already overcome poverty in Sangluo, Ankang, and Hanzhong cities, which are covered by the project and include Baihe County (Sasha Citation2017). Actually, some previous studies have found that resettlers felt good about their relocation and were confident in the future although they were dissatisfied with the reduction in natural capital (Bao and Peng Citation2016; Li et al. Citation2018).

Another possible explanation is that for some relocation projects, natural capital is not as important as expected in evaluating the quality of livelihoods or performance of the relocation policy. In this study, we found that livelihood assets and physical, social, human, and financial capital, which contribute to livelihood assets, were associated with higher acceptance of relocation policies. However, natural capital was not significantly correlated with policy acceptance. These results challenge traditional assessment models (e.g. SLF, IRR) which regard natural capital compensation as an indispensable indicator for resettlement. Natural capital may be a key indicator for the livelihood of resettlers in traditional society, because it is the basis of livelihood and production in rural areas (Patel & Mandhyan, Citation2014). However, this may be not the case while urbanization and capitalization are rapidly increasing. Reduction in natural capital does not inevitably cause poverty and unsustainable livelihoods but tends to be compensated by urban opportunities as well as new income sources.

Whether the loss of natural capital influence the resettlers’ livelihoods may depend on the types of resettlement. For displacement and resettlement related to urbanization, poverty alleviation, disaster prevention, or combinations of these, land-based resettlement has limited value for resettlers who are rebuliding their livelihoods. Thus, restricting compensation amounts to the area of land and the values of land products, which the resettlers owned before relocation (a kind of equal-amount assessment) is not essential in livelihood assessments. The loss of some natural assets is usually compensated with money, safe and valuable residences, better infrastructure and environment, more opportunities for well-paid jobs, better education, and other benefits, which are more beneficial for resettlers’ livelihood during periods of urbanization or capitalization. Land-based resettlement could be an option in rural areas, but it should not be regarded as an indispensable policy, and too much emphasis on natural assets may lead to underestimation of the success of a relocation policy.

Limitation

Many resettlers change their jobs from farmers to workers or staff. Their new jobs in the labor market rely heavily on the economic situation. When the economy goes down, natural resources (especially land) may protect the sustainable livelihoods of households. Therefore, a major limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data, which restricted us from examining the role of natural capital for resettlers’ livelihoods in different economic periods. Another data limitation is that our data come from a typically underdeveloped area of western China, which is enforcing resettlement for disaster prevention combined with poverty-alleviation. The extent to which our findings can be generalized to other relocation projects in China needs to be addressed by replicating the study in other areas.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Editor Thomas B Fische and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. Thanks especially to Dr. Zhu Zhengwei and his research team for assistance in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Apine E, Turner LM, Rodwell LD, Bhatta R. 2019. The application of the sustainable livelihood approach to small scale-fisheries: the case of mud crab Scylla serrata in South west India. Ocean Coast Manage. 170:17–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.12.024.

- Bang HN, Few R. 2012. Social risks and challenges in post-disaster resettlement: the case of Lake Nyos Cameroon. J Risk Res. 15:1141–1157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2012.705315.

- Bao H, Peng Y. 2016. Effect of land expropriation on land-lost farmers’ entrepreneurial action: A case study of Zhejiang Province. Habitat Int. 16(53):342–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.12.008.

- Bott LM, Ankel L, Braun B. 2019. Adaptive neighborhoods: the interrelation of urban form, social capital, and responses to coastal hazards in Jakarta. Geoforum. 106:202–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.016.

- Bui TMH, Schreinemachers P. 2011. Resettling farm households in northwestern Vietnam: livelihood change and adaptation. Int J Water Resour D. 27(4):769–785.

- Cernea MM. 2000. Risks, safeguards and reconstruction: A model for population displacement and resettlement. Econ Polit Wkly. 35:3659–3678.

- Cernea MM. 2007. IRR: an operational risks reduction model for population resettlement. Hydro Nepal J Water Energy Environ. 1:35–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.3126/hn.v1i0.883.

- Cernea MM, McDowell C. 2000. Risk and reconstruction: experiences of resettlers and refugees. Washington (DC): World Bank; p. 11–55.

- Cernea MM, Schmidt-Soltau K. 2006. Poverty risks and national parks: policy issues in conservation and resettlement. World Dev. 34:1808–1830. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.02.008.

- Collins BK, Kim HJ, Tao J. 2019. Managing for citizen satisfaction: is good not enough? J Pub Nonprof Aff. 5(1):21–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.20899/jpna.5.1.21-38.

- Danquah JA, Attippoe JA, Ankrah JS. 2014. Assessment of residential satisfaction in the resettlement towns of the Keta basin in Ghana. J Civ Eng Constr Estate Manage. 2(3):26–45.

- de Sherbinin A, Castro M, Gemenne F, Cernea MM, Adamo S, Fearnside PM, Krieger G, Lahmani S, Oliver-Smith A, Pankhurst A, et al. 2011. Preparing for resettlement associate with climate change. Science. 334(6055):456–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208821.

- Fornell C, Johnson MD, Anderson EW, Cha J, Bryant BE. 1996. The American customer satisfaction index: nature, purpose, and findings. J Mark. 60(4):7–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1251898.

- Hasegawa A, Ohira T, Maeda M, Yasumura S, Tanigawa K. 2016. Emergency responses and health consequences after the Fukushima accident; evacuation and relocation. Clin Oncol. 28(4):237–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2016.01.002.

- Johnson MD, Herrmann A, Gustafsson A. 2002. Comparing customer satisfaction across industries and countries. J Econ Psychol. 23(6):749–769. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(02)00137-X.

- Karanth KK, Kudalkar S, Jain S. 2018. Re-building communities: voluntary resettlement from wildlife reserves in India. Front Ecol Evol. 6:183. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00183.

- Li C, Li S, Feldman MW, Li J, Zheng H, Daily GC. 2018. The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of a major relocation and settlement program: a case in Shaanxi China. Ambio. 47:245–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0941-7.

- Liu W, Xu J, Li J. 2018. The influence of poverty alleviation resettlement on rural household livelihood vulnerability in the western mountainous areas, China. Sustainability. 10(8):2793. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082793.

- LODRP (Leader-group Office of Displacement and Resettlement Project in Southern Shannxi Province). 2015. Big displacement in Southern Shannxi: 410,000 poor population got rid of the poverty in the three cities of Souther Shannxi in the past 4 years. Shannxi Daily. Jul 6 accessed 2019 Oct 8. https://xian.qq.com/a/20150706/007827.htm. (in Chinese)

- Magembe-Mushi DL. 2018. Impoverishment risks in DIDR in Dar es Salaam City: the case of airport expansion project. Curr Urban Stud. 6(4):433. doi:https://doi.org/10.4236/cus.2018.64024.

- Mensah EJ. 2012. The sustainable livelihood framework: A reconstruction. Dev Rev–Byd Res. 1(1):7–24.

- Murray KE. 2010. Sudanese perspectives on resettlement in Australia. J Pac Rim Psychol. 4(1):30–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1375/prp.4.1.30.

- Naidoo R, Gerkey D, Hole D, Pfaff A, Ellis AM, Golden CD, Herrera D, Johnson K, Mulligan M, Ricketts TH. 2019. Evaluating the impacts of protected areas on human well-being across the developing world. Sci Adv. 5(4):eaav3006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav3006.

- Nguyen P, van Westen A, Zoomers A. 2017. Compulsory land acquisition for urban expansion: livelihood reconstruction after land loss in Hue’s peri-urban areas, Central Vietnam. Int Dev Plann Rev. 39:99–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2016.32.

- Patel S, Mandhyan R. 2014. Impoverishment assessment of slum dwellers after off-site and on-site resettlement: a case of Indore. C'wealth J Local Gov.15:104–127.

- Sasha. 2017. Set an example of resettlement for the whole country: A survey on displacement and resettlement (poverty alleviation) in Shaanxi Province. Shannxi Daily, Nov. 20 accessed 2019 Oct 8 http://esb3.sxdaily.com.cn/sxrb/20171120/mhtml/page_09_content_000.htm. (in Chinese)

- Scoone I 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: aframework for analysis. IDS Working Paper, 72. IDS, UK; accessed 2019 Jul 15 https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/3390.

- Serrat O. 2017. Knowledge solutions: tools, methods, and approaches to drive organizational performance. Singapore: Springer; p.21–26. accessed 2019 May 20. https://link.springer.com/chapter/ https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_5.

- Sina D, Chang-Richards AY, Wilkinson S, Potangaroa R. 2019. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 117:253–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.01.003.

- Smyth E, Steyn M, Esteves AM, Franks DM, Vaz K. 2015. Five ‘big’issues for land access, resettlement and livelihood restoration practice: findings of an international symposium. Impact Assess Proj A. 33(3):220–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2015.1037665.

- Snodgrass JG, Upadhyay C, Debnath D, Lacy MG. 2016. The mental health costs of human displacement: a natural experiment involving indigenous Indian conservation refugees. World Dev Perspect. 2:25–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2016.09.001.

- Sridarran P, Keraminiyage K, Fernando N. 2018. Acceptance to be the host of a resettlement programme: a literature review. Procedia Eng. 212:962–969. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.124.

- Van Ryzin GG, Muzzio D, Immerwahr S, Gulick L, Martinez E. 2004. Drivers and consequences of citizen satisfaction: an application of the American customer satisfaction index model to New York City. Pub Admin Rev. 64(3):331–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00377.x.

- Vaz-Jones L. 2018. Struggles over land, livelihood, and future possibilities: reframing displacement through feminist political ecology. Signs. 43:711–735. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/695317.

- Wayessa GO, Nygren A. 2016. Whose decisions, whose livelihoods? Resettlement and environmental justice in Ethiopia. Soc Nat Resour. 29(4):387–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1089612.

- Wilmsen B. 2018. Is land-based resettlement still appropriate for rural people in China? A longitudinal study of displacement at the Three Gorges Dam. Dev Change. 49:170–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12372.

- Wilson SA. 2019. Mining-induced displacement and resettlement: the case of rutile mining communities in Sierra Leone. J Sustain Min. 18(2):67–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsm.2019.03.001.

- Xiao Q, Liu H, Feldman M. 2018. Assessing livelihood reconstruction in resettlement program for disaster prevention at baihe county of china: extension of the Impoverishment Risks and Reconstruction (IRR) model. Sustainability. 10(8):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082913.

- Yu B, Xu L, Wang X. 2016. Ecological compensation for hydropower resettlement in a reservoir wetland based on welfare change in Tibet, China. Ecol Eng. 96:128–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.03.047.

- Zlotnik H. 2017. World urbanization: trends and prospects. In: Chapman T, Hugo G, editors. New forms of urbanization: beyond the urban-rural dichotomy. London: Routledge; p. 43–64.