ABSTRACT

A “Health in All” approach has been encouraged by India’s National Health Policy to address cross-sectoral health concerns. To illustrate how health concerns can be systematised in food system planning, we pursued a health impact assessment (HIA) of a watershed development (WSD) project in semi-arid Kolar district, India. The planned WSD project included measures for soil and water conservation, improving agricultural productivity, and enhancing livelihoods of landless and poor households. An HIA approach previously employed for an agricultural project in a tropical setting was adapted for the current HIA, to accommodate for (i) the project implementing agency being a non-profit and (ii) the HIA being conducted in-parallel with the baseline socioeconomic assessment . The HIA revealed that the WSD project might result in a range of positive (e.g. nutrition, sanitation and water quality) and negative health impacts (e.g. vector-borne diseases, pesticide exposure, drowning and zoonosis). HIA of these projects holds promise to influence health in remote drought-prone areas and build-up HIA capacity through application in non-controversial project environments.

Introduction

Most of India’s population relies on agriculture for livelihood (Government of India Citation2019) and nutrition (Headey et al. Citation2012; Kadiyala et al. Citation2014). Farmers in semi-arid areas depend on rainfall and groundwater for cultivation. In these areas, watershed development (WSD) projects have been implemented to support local livelihood, enhance ecological services (Kerr Citation2002) and adapt to climate change (IISc Citation2014). Official guidelines for WSD projects were re-issued in 2008 by the Government of India (Citation2011), focussing on soil and water conservation, ecological balance, local participatory planning and management, equity and livelihood. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are often the primary implementors of these projects, in partnership with the local government and communities.

Few retrospective studies from India indicated positive impacts of completed WSD projects on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), access to healthcare (Nerkar et al. Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2016), food security and nutrition (Pandit Citation2010; Pradyumna et al. Citation2020b). On the other hand, potential negative impacts on vector-borne diseases (VBDs) and pesticide exposure due to increase in surface waterbodies and agriculture, respectively, were also recently reported (Pradyumna et al. Citation2020b). Such concerns and opportunities should be addressed early on in the project planning.

Health impact assessment (HIA) is an interdisciplinary approach that applies different tools and methods to systematically judge the potential, and sometimes unintended, effects of a project, programme, policy or strategy on the health of a population and the distribution of those effects within the population (Quigley et al. Citation2006). HIA has been used in the context of agricultural projects (Knoblauch et al. Citation2014) and policies (Lock et al. Citation2003). In India, health assessments are included under the umbrella of environmental impact assessment (EIA). However, EIA is mandated only for some types of projects, such as large mining projects (Government of India Citation2006), but not for agricultural policies, programmes or projects. In addition, it was recognised that attention to health assessment was grossly inadequate in EIA in India (Cave et al. Citation2013; Pradyumna Citation2015). Also, while the need for nutrition-sensitive agriculture has received some attention in national policies (Ministry of Agriculture Citation2013; NITI; Aayog Citation2017) and in international reports (IFPRI Citation2015), several potential negative health impacts of food systems interventions have received less attention (Pradyumna et al. Citation2019). Hence, the need for health assessments has been recognised in India (Ahuja Citation2007; Cave et al. Citation2013; Dua and Acharya Citation2014), specifically also for agricultural projects (Pradyumna and Chelaton Citation2018). HIA would also align well with the ‘Health in All’ approach that has been encouraged in the National Health Policy (Government of India Citation2017).

WSD projects are a potential candidate for operationalising the ‘Health in All’ vision for rural areas in India. With well over 2 million km2 of land eligible for WSD projects (Government of India Citation2011), they touch millions of households across India. Importantly, due to the integral participatory approach and of diverse social and environmental activities in WSD projects, their potential to be an ‘umbrella for uniting developmental programmes’, including health, for villages in India was recognised (Technical Committee on Watershed Programmes in India Citation2006).

We present a case study of an HIA of a proposed WSD project in the semi-arid Kolar district in the southern part of India. We show the value of HIA in systematically and prospectively identifying potential impacts (negative and positive) for the planning of risk mitigation and health promotion measures, and discuss opportunities presented due to NGOs being the usual implementors of these projects. We hope that our case study will inspire future WSD projects to apply HIA at the planning stage and to provide opportunities for HIA capacity building in India.

Context for the HIA

MYRADA Kolar Project is a local NGO that has worked through partnerships with governmental departments, private philanthropies and local communities on agricultural and developmental projects. Their expertise, innovation and contribution to WSD practice have been recognised in the official guidelines by the Government of India (Citation2011).

A preceding study by the authors identified perceived health impacts of recently completed WSD projects implemented by the aforementioned NGO in various parts of Kolar district (Pradyumna et al. Citation2020b). Based on the findings, especially the few potential negative health impacts, the idea for conducting an HIA was proposed by the first author to the NGO management team for their next WSD project proposal. The NGO agreed to incorporate an HIA component in the feasibility studies of the WSD project as they appreciated the opportunity it would provide to identify and mitigate potential negative health impacts and further enhance positive health impacts of their project, through the proposed objectives of the HIA, which were:

to describe the baseline health conditions of the local population;

to identify potential health impacts of the proposed WSD project, including considerations of magnitude and significance; and

to make evidence-based recommendations towards mitigation of potential negative health impacts and promotion of health opportunities.

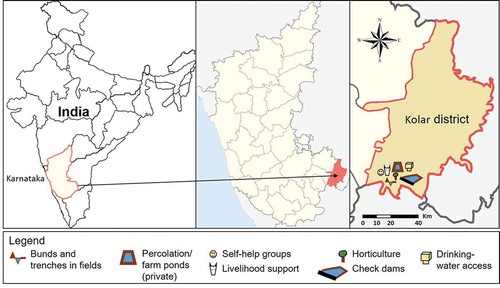

The proposed WSD project covers a cluster of four villages in Kolar district (henceforth called project villages) (see ). Agriculture is the main livelihood in the area and the district is classified as highly vulnerable to climate change (University of Agricultural Sciences – Bangalore Citation2011). The components of the proposed WSD project are summarised in Box 1. The HIA was initiated in March 2019 and the report was submitted in September 2019. A dissemination meeting with the project managers and assistants was conducted in January 2020.

HIA approach overview and innovations

The HIA followed the methodological approach put forth by Winkler et al. (Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012), which was specifically designed for, and validated in, tropical settings in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where there is a paucity of readily available data for supporting the HIA. Of note, the methodology has already been applied successfully to agricultural developments (Knoblauch et al. Citation2014; Winkler et al. Citation2014). Key steps in the HIA approach are briefly summarised in Box 2. In the following sub-chapters, methodological features considered particularly relevant for the given context, are described.

Involvement of project proponent in HIA

In a deviation from usual practice, the baseline health survey was administered to local people by staff of the NGO. Several reasons guided this decision: (i) the NGO already conducted the socio-economic assessment, and hence, it was logistically and financially efficient to add the baseline health data collection to these activities; (ii) the HIA had to be completed in a short period of time, and so the familiarity between NGO staff members and local people facilitated relatively quick data collection; and (iii) it was recognised as an opportunity for capacity building of NGO staff members on health and surveys (discussed later). This decision was acceptable because WSD projects are inherently welfare and empowerment oriented, rather than for the profit of a private entity.

Health census of all households

Another unusual feature was that the baseline health survey covered all households in the project villages because (i) the socioeconomic assessment was being conducted across all households and (ii) the total number of households was relatively small. A sample survey would have yielded imprecise estimates and added challenges in comparing project villages with comparison villages. The detailed methodology and findings of the baseline survey are available in Pradyumna et al. (Citation2021).

Managing data gaps

Several gaps were found in secondary health data, which were systematically assessed through approaches described by Winkler et al. (Citation2011). Resource limitations only allowed for some of the data gaps to be addressed through the baseline survey. Hence, a semi-quantitative risk assessment approach was employed here (adapted from the framework used before (Winkler et al. Citation2010)). The risk assessment approach proved particularly relevant and useful in the context of poor availability of secondary health data, which would be the case in most situations in India, especially if data are needed at village level or for diseases that are not part of the routine surveillance and reporting systems. The assessment for each environmental health area was done by the first author under the guidance of the other co-authors.

Salient findings from the HIA

Results of the scoping exercise

The geographic boundary for the HIA pertained to the four villages potentially impacted by the WSD project. In terms of temporal boundary, a seamless transition between the construction and operation was pre-defined in view of the WSD project to be implemented in a stepwise manner within and across villages between 2019 and 2024. The scoping review of secondary data and literature on Kolar district can be summarised as follows:

dengue and chikungunya outbreaks have occurred in the recent past (Balakrishnan et al. Citation2015);

in rural Kolar, in 2016, the prevalence of anaemia in women of reproductive age was 45.9% (IIPS Citation2016);

drowning in farm ponds were reported from neighbouring sub-districts in Kolar in 2019 (Kanathanda Citation2017);

dental fluorosis prevalence ranged between 1.9% and 13.1% in prior surveys (Shruthi and Anil Citation2018), and skeletal fluorosis was approximately 5% among adults in nearby sub-districts in 2012 (Shruthi et al. Citation2016);

among individuals aged 15–49 years, high blood pressure was recorded in 10.7% of women and 10.2% of men in Kolar district in 2016 (IIPS Citation2016); and

the reported groundwater fluoride levels for project villages was 3.1 mg/l (range 2.7–3.6 mg/l, as compared to the reference standard of 1.5 mg/l (Bureau of Indian Standards Citation2012)).

In addition, the group discussions with local people and an interview with a healthcare provider pointed to challenges of VBDs, water quality (fluoride contamination), agricultural injuries and access to healthcare (inadequate transport facilities) in the local area. summarises potential health impacts of concern identified during the scoping step. For each potential health impact, key health indicators for the HIA were defined, covering both determinants of health and health outcomes.

Table 1. Potential health impacts, pathways and proposed indicators of the planned WSD project in India

The baseline survey revealed several aspects regarding local population health. About one of seven households (13.8%) were woman-headed. Some households belonged to scheduled tribes (ST; 30.8%) or scheduled castes (SC; 7.7%). Agriculture was the main source of income (67.2%). One out of five households depended primarily on wage labour (19.5%). Most of the households owned less than 10,000 m2 (1 ha) of land (66.2%). Access to irrigation was available to 39.5% of households. Most households (57.9%) owned at least one type of livestock (15.4% among SC households). Almost 37% households had a member in self-help groups (SHGs) (7.7% for SC households). Most households (86.2%) owned some form of motorised transport. Most households used gas stoves for cooking (88.2%), though many also occasionally used firewood. Median distance for collecting water was 100 m (range: 0–1,000 m). Most households (90.3%) depend on groundwater for domestic use. More than half of the households (56.9%) did not use any method of purification. Most households owned a private toilet (92%). Soap was observed only at around half of the hand-wash facilities (48.7%). The proportion of households with individuals who were smoking, consumed alcohol or chewable tobacco were 15.9%, 13.8% and 23.6%, respectively. Spraying pesticides was done by individuals in 43.6% of households at least once a month. Most households (79.5%) opined that it was convenient to access healthcare, and all households opined that local healthcare was satisfactory. Over 20% of households reported having experienced food insecurity in the previous 2 years, and 26% having not consumed fruits during the previous month. Only 6.7% of the respondents were unable to mention any one iron-rich food. Two-third of the respondents (64.1%) had knowledge of at least one effect of exposure to high fluoride levels. The anthropometric survey revealed the prevalence of underweight and undernourishment (based on mid-upper arm circumference) among children below the age of 5 years as 26.5% and 14%, respectively, in the project villages.

Results from impact assessment

After defining the impacts and impact pathways for all environmental health areas, semi-quantitative risk assessment was applied (). Based on the impact assessment, the factors that emerged as the greatest concerns in the ‘without mitigation’ scenario were VBDs, accidental drowning and pesticide exposure. The factors presenting opportunities for positive health impacts were women’s empowerment, nutrition, access to healthcare and water quality.

Table 2. Summary of impact assessment of the planned WSD project

Recommendations towards risk mitigation and health promotion

Potential mitigation measures for the main health concerns are summarised in . Suggested measures primarily pertained to awareness building on specific health issues in collaboration with the local governmental department, keeping in mind the availability of resources. In addition, process monitoring and post-project impact evaluation of the HIA were also suggested to benefit learning from the experience.

Table 3. Key recommendations to project managers based on the HIA

Discussion

Novel aspects of this HIA case study

To our knowledge, this is the first reported HIA of a WSD project proposal, and hence, it makes a contribution to the sparse literature on HIA on food systems projects. In addition, this may be the first reported comprehensive HIA from India for any kind of project. These two factors have important implications for the practice of HIA in India (discussed later).

Some features of WSD projects contributed to an unusual context for the HIA. For instance, impact assessments are not routinely conducted on projects that are inherently oriented towards community wellbeing, and so this case study sheds light on how community development projects could incorporate health considerations in planning. Also, the size of the individual projects is small, covering only few villages (constituting a microwatershed). Hence, this is an example of an HIA conducted for a small project. Finally, project proponents are usually not directly involved in conducting the HIA, but in the current case, as profits and private investments were not factors, their participation was possible and was also fruitful.

Utility of HIA for the WSD project

Taken together, the predicted health risks of the proposed WSD project were relatively few and of low magnitude, but the HIA helped to systematically identify, acknowledge and plan towards addressing them. For instance, potential impacts on vector ecology, risk of accidental drowning and zoonotic diseases would not have been considered without the current HIA.

WSD project objectives are, in principle, inherently health promoting (e.g. water access, food security and income). Additionally, locally relevant opportunities for health promotion were also identified, for example, by specific recommendations on access to potable water to reduce exposure to fluoride and incorporating nutrition-enhancing activities. The HIA made the NGO aware that developmental projects have health implications, and this may render them more likely to be systematically addressed in future projects. The post-project evaluation will provide further insight on adoption of the recommendations and potential impacts on people’s health and wellbeing. Additional HIA case studies could also further inform the ‘must-have’ and ‘good-to-have’ aspects of a comprehensive HIA for WSD projects.

Opportunities and implications for practice

Capital-intensive projects, such as mining projects, are politically contentious (Kalshian Citation2007), which is a challenge for impact assessment practice. Corruption too was identified as a problem (Paliwal Citation2006) besides low capacity for HIA in India (Cave et al. Citation2013; Pradyumna Citation2015). WSD projects are non-controversial, and hence, offer a safe platform for capacity building and clarifying the utility of HIA in India. This is besides addressing health concerns in remote areas, and building capacity on health and health surveys among community development NGOs in often marginalised settings. Organisations with a primary objective of community development – such as governmental departments and NGOs – are in a good position to embrace HIA. These organisations and also WSD projects mainly have a social and environmental basis for their work. The present HIA case study demonstrates how the opportunity for community health enhancement can also be used as an additional strong argument for these projects, especially on critical outcomes such as nutrition and VBDs. It is worth mentioning that the HIA approach used here was found to be suitable for settings with inadequate secondary health data, such as would be seen in most rural parts of India.

Our findings and reflections are also relevant to HIA practice in other comparable geographical contexts such as other South Asian and sub-Saharan African countries. For example, there have been collaborative capacity-building arrangements for WSD between NGOs in India and organisations in Nepal, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Uganda (MYRADA Citation2020; WOTR Citation2020). Hence, lessons from the present case study have the opportunity to diffuse.

Limitations of the case study

Coverage of the baseline survey in these villages was universal, and therefore creates a representative picture of health in the community surrounding the WSD, but this would contribute to challenges while comparing with the comparison villages during evaluation. However, other comparative methods, as employed in a prior HIA of a biofuel project in Sierra Leone, could be used (Knoblauch et al. Citation2014). NGO workers implementing the health survey were from project villages and were hesitant in asking sensitive questions on alcohol consumption and hygiene practices, indicating the importance of a strong prior training and planning. As time and resources were limited, no biological samples were collected from the study population. This would require that the baseline survey was further supported by a health research and laboratory team. While this would lead to additional costs, it would also reduce any perceived conflict of interest in data collection. Also, time permitting, further exploration of relevant health concerns could have been undertaken, for instance, more detailed stakeholder perceptions of drowning risk in farm ponds. Finally, this HIA was proposed and conducted by the authors at no financial cost to the project-implementing NGO. Further insights on the effects of the HIA process will be gained over the next few years through an in-depth evaluation.

Conclusion

The HIA of a planned WSD project in India was conducted in a setting with limited secondary data. The process facilitated a deeper understanding of baseline health conditions, identifying potential project-related health risk (e.g. increase in vector-breeding sites) and opportunities for risk mitigation (e.g. fencing of farm ponds to prevent accidental drowning) and health promotion (e.g. raising awareness about locally available nutritious food sources) in the context of proposed activities. In addition, the exercise benefited the local NGO through capacity building on how to conduct a cross-sectional survey and run an HIA. An evaluation will shed further light on acceptability and adoption of the HIA process and recommendations.

To our knowledge, there are no other reported HIAs of WSD projects. Moreover, HIA have largely been neglected in impact assessment practice in India. There is a strong argument to consider HIA for WSD projects due to their geographic scope and to foster HIA practice in a non-controversial project environment. There is ample opportunity for governmental departments and NGOs to adopt and further validate the presented HIA approach in the context of future WSD projects to be implemented in rural areas of India and also other LMICs.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahuja A. 2007. Health impact assessment in project and policy formulation. Econ Polit Wkly. 42(35):3581–3587.

- Balakrishnan N, Katyal R, Mittal V, Chauhan LS. 2015. Prevalence of Aedes aegypti - the vector of dengue/chikungunya fevers in Bangalore City, Urban and Kolar districts of Karnataka state. J Commun Dis. 47(4):19–23.

- Bureau of Indian Standards. 2012. Indian standard drinking water - specification (second revision). IS 10500 : 2012.

- Cave B, Jha-Thakur U, Rao M, Labhasetwar P, Fischer TB. 2013. Health in impact assessment and emerging challenges in India. In: O’Mullane M, editor. Integrating health impact assessment with the policy process: lessons and experiences from around the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 140–152.

- Dua B, Acharya AS. 2014. Health impact assessment: need and future scope in India. Indian J Community Med. 39(2):76. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.132719.

- Government of India. 2006. Environmental impact assessment notification. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Government of India. 2011. Common guidelines for watershed development projects - 2008 (revised 2011). New Delhi: Government of India.

- Government of India. 2017. National health policy 2017. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Government of India. 2019. Agricultural statistics at a glance 2018. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Headey D, Chiu A, Kadiyala S. 2012. Agriculture’s role in the Indian enigma: help or hindrance to the crisis of undernutrition? Food Secur. 4(1):87–102. doi:10.1007/s12571-011-0161-0.

- IFPRI. 2015. Global Nutrition Report 2015: actions and accountability to advance nutrition and sustainable development. Washington (DC): International Food Policy Research Institute.

- IIPS. 2016. National family health survey-4: district fact sheet: Kolar, Karnataka. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences.

- IISc. 2014. Transitioning towards climate resilient development in Karnataka - summary for policy makers. Bengaluru: Indian Institute of Science.

- Kadiyala S, Harris J, Headey D, Yosef S, Gillespie S. 2014. Agriculture and nutrition in India: mapping evidence to pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1331(1):43–56. doi:10.1111/nyas.12477.

- Kalshian R. editor. 2007. Caterpillar and the mahua flower - tremors in India’s mining fields. New Delhi: Panos South Asia.

- Kanathanda M 2017. State’s drought ponds turn into death traps for kids, animals [Internet]. accessed 2020 May 24]: Bengaluru News:[about 2 screens]. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/states-drought-ponds-turn-into-death-traps-for-kids-animals/articleshow/61192066.cms

- Kerr J. 2002. Watershed development, environmental services, and poverty alleviation in India. World Dev. 30(8):1387–1400. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00042-6.

- Knoblauch AM, Hodges MH, Bah MS, Kamara HI, Kargbo A, Paye J, Turay H, Nyorkor ED, Divall MJ, Zhang Y, et al. 2014. Changing patterns of health in communities impacted by a bioenergy project in northern Sierra Leone. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 11(12):12997–13016. doi:10.3390/ijerph111212997.

- Lock K, Gabrijelcic-Blenkus M, Martuzzi M, Otorepec P, Wallace P, Dora C, Robertson A, Zakotnic JM. 2003. Health impact assessment of agriculture and food policies: lessons learnt from the Republic of Slovenia. Bull World Health Organ. 81(6):391–398.

- Ministry of Agriculture. 2013. Guidelines for the establishment of nutri-farms scheme. New Delhi: Government of India.

- MYRADA. 2020. Long term partnerships – MYRADA [Internet]. accessed 2020 Dec 9]. https://myrada.org/long-term-partnerships/

- Nerkar SS, Pathak A, Lundborg CS, Tamhankar AJ. 2015. Can integrated watershed management contribute to improvement of public health? A cross-sectional study from hilly tribal villages in India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 12(3):2653–2669. doi:10.3390/ijerph120302653.

- Nerkar SS, Tamhankar AJ, Johansson E, Lundborg CS. 2013. Improvement in health and empowerment of families as a result of watershed management in a tribal area in India - a qualitative study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 13:42. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-13-42.

- Nerkar SS, Tamhankar AJ, Johansson E, Lundborg CS. 2016. Impact of integrated watershed management on complex interlinked factors influencing health: perceptions of professional stakeholders in a hilly tribal area of India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 13(3):285. doi:10.3390/ijerph13030285.

- NITI Aayog. 2017. Nourishing India - national nutrition strategy. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Paliwal R. 2006. EIA practice in India and its evaluation using SWOT analysis. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 26(5):492–510. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2006.01.004.

- Pandit A. 2010. Watershed development inputs and social change. Watershed Organisation Trust: Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

- Pradyumna A. 2015. Health aspects of the environmental impact assessment process in India. Econ Polit Wkly. 50(8):57–64.

- Pradyumna A, Chelaton J. 2018. The endosulfan tragedy of Kasaragod: health and ethics in non-health sector programs. In: Mishra A, Subbiah K, editors. Ethics in public health practice in India. Singapore: Springer Singapore; pp. 85–104.

- Pradyumna A, Egal F, Utzinger J. 2019. Sustainable food systems, health and infectious diseases: concerns and opportunities. Acta Trop. 191:172–177. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.12.042.

- Pradyumna A, Mishra A, Utzinger J, Winkler MS. 2020. Perceived health impacts of watershed development projects in southern India – a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(10):3448. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103448.

- Pradyumna A. et al 2021. Health of farmers’ households prior to modification of the occupational environment through a watershed development project in Kolar, India. Indian J Occup Env Med. In press

- Quigley RL, den Broeder P, Furu P, Bond B, Cave B, Bos R. 2006. Health impact assessment international best practice principles. Fargo: International Association for Impact Assessment.

- Shruthi MN, Anil NS. 2018. A comparative study of dental fluorosis and non-skeletal manifestations of fluorosis in areas with different water fluoride concentrations in rural Kolar. J Fam Med Prim Care. 7(6):1222–1228. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_72_18.

- Shruthi MN, Santhuram A, Arun H, Kishore Kumar B. 2016. A comparative study of skeletal fluorosis among adults in two study areas of Bangarpet taluk, Kolar. Indian J Public Health. 60(3):203–209. doi:10.4103/0019-557X.189014.

- Technical Committee on Watershed Programmes in India. 2006. From hariyali to neeranchal - report of the Technical Committee on Watershed Programmes in India. New Delhi: Government of India.

- University of Agricultural Sciences - Bangalore. 2011. Impact on agricultural sector. In: BCCI-K, editor. Karnataka climate change action plan – final report submitted by the Bangalore Climate Change Initiative – Karnataka to the Government of Karnataka. Bengaluru: Bangalore Climate Change Initiative – Karnataka (BCCI-K). p.33-46.

- Winkler MS, Divall MJ, Krieger GR, Balge MZ, Singer BH, Utzinger J. 2010. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: advancing tools and methods. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30(1):52–61. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2009.05.005.

- Winkler MS, Divall MJ, Krieger GR, Balge MZ, Singer BH, Utzinger J. 2011. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: the centrality of scoping. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 31(3):310–319. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.01.003.

- Winkler MS, Divall MJ, Krieger GR, Schmidlin S, Magassouba ML, Knoblauch AM, Singer BH, Utzinger J. 2012. Assessing health impacts in complex eco-epidemiological settings in the humid tropics: modular baseline health surveys. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 33(1):15 –22. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2011.10.003.

- Winkler MS, Knoblauch AM, Righetti AA, Divall MJ, Koroma MM, Fofanah I, Turay H, Hodges MH, Utzinger J. 2014. Baseline health conditions in selected communities of northern Sierra Leone as revealed by the health impact assessment of a biofuel project. Int Health. 6(3):232–241. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihu031.

- WOTR. 2020. Fr. Hermann Bacher learning centre, Darewadi, Ahmednagar [Internet]. Pune (India): Watershed Organisation Trust; [accessed 2020 Dec 9]. https://wotr-website-publications.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/DLC_Brochure_2020.pdf