ABSTRACT

In this paper we reflect on the interlinkages between social impact assessment and evaluation and, in particular, realist evaluation. To examine the connections between these fields of practice we draw on recent research in the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand, in which we linked social impact assessment and elements of realist evaluation in the study of rural and small-town regeneration. We use the research to identify a number of connections and to make suggestions regarding greater convergence of methods in social impact assessment and evaluation. We conclude by urging social impact assessment practitioners to use mixed methods, with a stronger emphasis on qualitative approaches, and especially to work with communities in an iterative way towards a conceptual basis for assessing and managing change and enhancing social wellbeing.

Introduction

There are significant and interesting connections between the practices of social impact assessment and evaluation. Social impact assessment analyses, monitors and manages the intended and unintended social consequences of interventions incorporating policies, plans, programmes and projects. This includes social change processes consequent upon these interventions (Taylor et al. Citation2004; Vanclay Citation2013). Evaluation, on the other hand, systematically, critically and creatively examines and reviews a plan, project, or programme against a set of criteria, usually associated with establishing improvements in social outcomes, often to establish organizational accountability or social value (Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit Citation2015) and also to evaluate the effectiveness of impact assessment processes (Alberts et al. Citation2020).

With their shared history in applied social sciences, social impact assessment and evaluation retain much in common. Applied social scientists commonly work across both fields. There are subsets of evaluation applied to different areas of social policy, including health and education. While much of this work is summative, some is formative, applied to the planning and design of policy and programmes. Practitioners of social impact assessment define this formative work as strategic assessment, considering the impacts and effectiveness of policies and programmes, while having an input into the development of new ones (Taylor and Mackay Citation2016a; Morgan and Taylor Citation2021). Furthermore, when social impact assessment practitioners take part in strategic environmental assessments this commonly includes evaluation of how policies have affected, and will in future affect, community outcomes and social wellbeing in the context of environmental and social sustainability (Aucamp et al. Citation2011; Aucamp and Woodborne Citation2020). Water management, for instance, is an example of this integrated approach, where social impact assessment has been used for policy formation to guide land and water management along with evaluation of previous management systems, while recommending ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the new policies and plans (Taylor and Mackay Citation2016a).

Our purpose in this paper is to examine linkages between the fields of evaluation and social impact assessment. Our starting point is to note the similarities in method, in particular between the ideas and methods of realist evaluation and iterative, adaptive, participatory social impact assessment. We will discuss potential methodological advances by drawing on research funded by the Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities: Ko ngā wā kaingā hei whakamahorahora New Zealand National Science Challenge. The research has examined regeneration projects and programmes in rural areas and towns in the South Island of Aotearoa New Zealand in which the tenets of realist evaluation and participatory social impact assessment were influential (Perkins et al. Citation2019). The research investigated a common problem in rural areas and small towns where decisions are made about the investment of effort and funds into initiatives and programmes without sufficient evidence about success factors, or about the impacts of resulting changes. The paper argues for renewed attention to the importance of local knowledge in social impact assessment alongside secondary data, through an iterative mixed-method approach (Baines et al. (Citation2013), and for the co-production of knowledge generated collaboratively by researchers and research participants.

Realist evaluation and social impact assessment

Our thinking about evaluation in relation to social impact assessment is influenced by the work of Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997), Pawson and Manzano-Santaella (Citation2012), Pawson (Citation2013), Kelly (Citation2019), the World Bank Group (Citation2019), and the Evaluation Standards for Aotearoa New Zealand (Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit Citation2015). In particular, we have found the tenets and practices of realist evaluation to be thought-provoking. This is a theory-driven method that ‘identifies and refines explanations of programme effectiveness’ (Pawson and Manzano-Santaella Citation2012). It rejects rigid and formulaic approaches to evaluation, and began with a desire to rehabilitate and re-energise evaluation, exhorting the ‘would-be evaluator [to] stop feigning certainty and instead celebrate the free, instinctive play of imagination within decision-making’ (Pawson and Tilley Citation1997, p. xii).

The realist evaluative approach thus asks essential questions about what works, why, and for whom. Two of its key features are the attempt to bridge the longstanding antagonisms in evaluation practice between reductionist and holistic viewpoints, and between qualitative and quantitative methods. Realist evaluators consider that it is important to qualitatively interpret the unfolding narrative of a programme – examining the meanings participants ascribe to their experiences. They also consider that it is crucial to measure the quantum of change created by a programme or intervention. Only by combining these two broad approaches can realist evaluation be employed to understand fully the effectiveness of a programme or other intervention.

As discussed by Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997), the tools used in realist evaluation share many of the characteristics of social science enquiry. Evaluators begin by framing theories about the programme to be evaluated ‘in terms of propositions about how mechanisms are fixed in contexts to produce outcomes’ (op cit. pp. 84–85). Once framed, they then engage in hypothesis making in which programmes are disaggregated so that the measures that can effect change are identified. The key question being asked here is: ‘What might work for whom in what circumstances?’ Each hypothesis is then tested with data collected and analysed using a plurality of relevant qualitative and quantitative methods. Once this work is completed it is possible to specify what about a programme works or doesn’t, and who, or who does not, benefit. Pawson and Manzano-Santaella (Citation2012 p. 181) describe realist evaluation as a multi-dimensional process looking to discover ‘rich outcome patterns’ through a series of intense interactions with stakeholders and affected people. New Zealand author Katherine Mansfield wrote about this philosophy of information gathering and analysis as ‘piecing together this and that, finding the pattern, solving the problem’ and it may be that this approach to complex issues is a particular feature of Aotearoa New Zealand culture and leadership (Kennedy Citation2009, p. 425).

Social impact assessment refers to the process of analysing, predicting, mitigating, monitoring, managing and evaluating the intended and unintended social consequences, both positive and negative, of planned interventions (policies, programmes, plans, projects) and the resulting social change processes. We draw in particular on Taylor et al. (Citation2004), Vanclay et al. (Citation2015) and Mackay and Taylor (Citation2020) for our understanding of the process and methods of social impact assessment. Their approach asks questions about how people and communities are affected by an intervention and specifically considers who is affected and how in order to mitigate or manage those effects and the consequences for social equity and social wellbeing. Social impact assessment combines iterative cycles of data gathering in a multi-method approach in phases of synthesis, deduction and induction to identify and manage the impacts of a plan, programme or project (Taylor et al. Citation2004, p. 95). This approach is in strong contrast to the common practice of social impact assessment as a formulaic, tick-box exercise focused on project approval rather than the complexities of social development (Aucamp and Woodborne Citation2020, p. 132).

In reviewing our application of realist evaluation and social impact assessment in the course of this research we observed significant connections between the methods of realist evaluation and social impact assessment and found a number of implications for future practice of social impact assessment. Most importantly, both benefit from qualitative methods and ‘intensely practical’ hypothesis generating work early in the assessment, particularly, in the case of social impact assessment, during scoping (Taylor et al. Citation2004, p. 98).

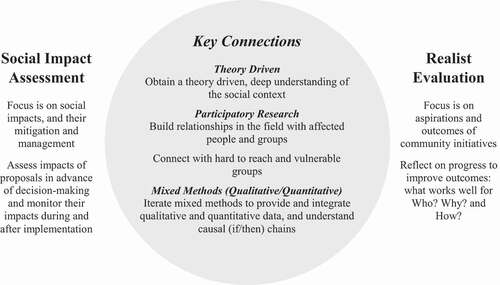

The connections between the two fields are summarised in () and include the need to take time and obtain a deep understanding of the social environment, and to build active relationships within the field of analysis. An iterative process of data gathering, synthesis and engagement that begins with thorough scoping will build an understanding of if-then causal chains of effect and a conceptually based understanding of change a priori and ex post.

Theory-driven

In recognising the methodological connections between social impact assessment and realist evaluation, as illustrated in , we found that both fields are relevant for analysis of locally-driven, regional or national level policy, plans and programmes, as they encourage a critical engagement with social theory to understand the multiple layers of social and environmental systems. While both social impact assessment and realist evaluation are theory-driven, they are eclectic in terms of that theory.

Social impact assessment and realist evaluation rely on the development of a series of inductive theoretical propositions, which Pawson and Manzano-Santaella (Citation2012) call ‘if-then’ propositions. These theoretical propositions about social change attempt to break the analysis of outcomes from an evaluated policy or programme into their ‘constituent and interconnected elements’ (Pawson and Manzano-Santaella Citation2012, p. 184). In social impact assessment these propositions require conceptualising and testing of impact chains, and how they intersect or form a web (Taylor et al. Citation2004 p., 64) so the assessment can develop a strong understanding of impacts, their causes, likelihood, significance and longer-term consequences for social wellbeing, including who is affected and how. International guidelines developed by IAIA for social impact assessment (Vanclay et al. Citation2015, p. 3) note that ‘social impacts are rarely singular cause-effect relationships.’ but more likely to be found in complex pathways between social, ecological, economic, health and cultural factors. Health impact assessors also recognise the complex pathways and determinates affecting the important social outcome of human health (Fischer and Cave Citation2018, ). Similarly, realist evaluation noticeably accounts for ‘networks of outcomes’ versus lists of ‘discrete outcomes’ (Pawson and Manzano-Santaella Citation2012, p. 181). As Middleton et al. (Citation2019) argue: outcomes in programmes comprising multiple agency partners that serve spatially dispersed communities are inevitably multi-dimensional and interlinked in complex ways. They can never be discrete.

Quantitative data

Realist evaluators and social impact assessors both take a practical stance with respect to survey methods and the collection of primary quantitative data. Survey research of a client group, or of affected people, provides a way of testing a working hypothesis and breaking data gathering into quantifiable variables. Burdge (Citation2004 pp. 42–44) lists 21 such social impact assessment variables based in the social science literature that in most instances refer to a phenomenon that can be measured either by secondary or primary data.

There is a tendency among social impact assessment practitioners, however, to over-emphasise the use of secondary quantitative information because of its utility in providing a quick description of the social baseline. They often use data collected from administrative sources to help to set the scene by creating a picture of the social context of an intervention, usually known as a social baseline. Once established, this baseline is used to plot and manage social change. While a useful place to begin in describing the social context before a change takes place, it is important that the data collected is at an appropriate spatial scale and an appropriate time frame (Vanclay et al. Citation2015, p. 44).

The theoretical propositions of change should assist in identifying suitable change variables and the scales and timeframes on which they will apply. Importantly, a realist approach treats the baseline as dynamic. Most relevant are those measures and descriptors that give a picture of conditions with and without, and before and after, an intervention (Burdge and Johnson Citation2004, p. 18). Such measures in the rural areas of our research, included, for example, the populations of small towns and settlements, employment in sectors such as agriculture, tourism and food processing, the presence of migrant workers and cultural groups, and work opportunities for youth and Māori

Qualitative data

While quantitative data is often relied upon to build a broad picture of change in a community, and to describe and test pathways of social change, social impact assessment practitioners and realist evaluators have central concerns about the ability of quantification to fully explain critical relationships. As Pawson and Manzano-Santaella (Citation2012, p. 80) point out: ‘statistically significant relationships don’t speak for themselves. They are capable of multiple explanations and sometimes contradictory explanations and sometimes perverse, artefactual explanations.’ As a result of this concern, realist evaluation and social impact assessment place considerable emphasis on the use of qualitative data as a way to gain an in-depth understanding of the context for a social change process and also as a way to induce a theoretical explanation of that change (Blumer Citation1969; Becker Citation1998; Lofland et al. Citation2006). It is often the qualitative data that help us to ask the right questions of the quantitative data and make the best use of time spent compiling any secondary statistics, rather than producing, as often happens, a jumble of descriptive tables with little relevance to the assessment problem.

With respect to qualitative methods, social impact assessment and realist evaluation practitioners rely heavily on semi structured interviews, participant observation and casual conversations. These are often recorded digitally, along with detailed note taking and photography as part of the ‘discovery’ of social settings and the exploration of casual relationships and outcomes (Baines et al. Citation2003; Lofland et al. Citation2006; Mackay et al. Citation2018). The use of qualitative methods in social impact assessment and realist evaluation means that there is often a close and sustained engagement with affected people and communities, a process that social impact assessment practitioners consider essential to protecting human rights and gaining a social licence to operate from all stakeholders (Bice and Moffat Citation2014; Vanclay Citation2020, p 127) with community-centred engagement the basis for good practice (Parsons Citation2020, p.279). Deep analysis with inclusion of local knowledge allows for thorough investigation of the nature of effects, who is affected and how, and the significance of those effects, in terms of likelihood and scale.

Participatory research

In emphasising the value of qualitative work, many practitioners of social impact assessment and realist evaluation describe their work as participatory. A participatory approach to social impact assessment and evaluation is a primary source of qualitative data. Taylor et al. (Citation2004 p 25–31) drew on the work of early authors in the field of social impact assessment, such as Tester and Mykes (Citation1981), to emphasise two predominant orientations to the practice of social impact assessment: participatory and technocratic. They proposed that there are potential gains from working between these orientations, combining more effective uses of participation methods alongside technical assessment. Social impact assessment practitioners still struggle to reconcile these two orientations and often look for ways to mesh participation better into impact assessments (Roberts Citation2003; Burdge Citation2004; Taylor et al. Citation2004, Citation2016; Andre et al. Citation2006; Vanclay et al. Citation2015; Parsons Citation2020). Realist evaluators, by comparison, emphasise participation more strongly, promoting the importance of respectful relationships between organisations and affected communities and recognising the imbalance of power evident in many planned interventions (Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit Citation2015). Participatory work relates closely to longitudinal approaches in both assessment and evaluation because it provides time to build relationships necessary to a participatory ethos and an ethical approach, taking time to listen, check and adapt (Baines et al. Citation2003, p. 258).

Longitudinal analysis

Longitudinal analysis is fundamental to social impact assessment and to realist evaluation in order to explore responses to social change, success factors and social outcomes over time. Social impact assessment practitioners in particular recognise that causal relationships are found in the interaction of bio-physical and social environments (Slootweg et al. Citation2001) necessitating a longitudinal understanding of change in many places (Taylor et al. Citation2003). In the early years of social impact assessment in Aotearoa New Zealand, a longer-term, community level of analysis was common (Taylor and Mackay Citation2016b). Negative effects or outcomes, such as an increasing level of social inequity in a community, often emerge in a longer time period than the ex post evaluation of one project or programme can reveal. They also often emerge at a larger scale than many social impact assessments address (Aucamp and Woodborne Citation2020).

An examination of regeneration in Waitaki District and Oamaru: What we did and found

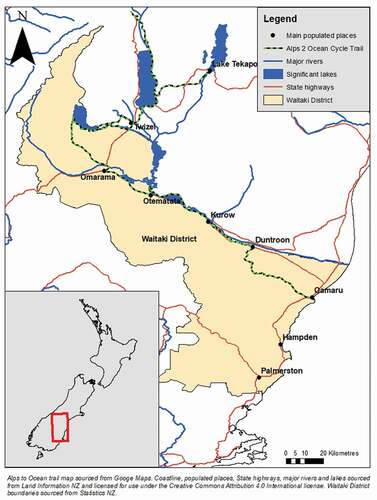

Our examination of the interplay between evaluation and assessment is based on research into regeneration attempts in the Waitaki District, New Zealand and its main settlement, Oamaru (). The research was part of the National Science Challenge – Building Better Homes Towns and Cities: Ko ngā wā kāinga hei Whakamāhorahora – focused on supporting success in regional settlements. The research asked how local regeneration initiatives are working to improve the economic, social and environmental performance of regional towns (Perkins et al. Citation2019). It investigated the drivers of success, and how regeneration initiatives are best designed and supported. Of particular interest in the research, were the issues of community capacity and the role of local councils, community groups and leaders in achieving integration of outcomes across numerous local initiatives (Mackay et al. Citation2018). In this respect the research was not a predictive analysis typical of many SIAs but an inductive, reflective analysis interested in the impacts and effectiveness of particular initiatives or sets of initiatives. Here we agree with Sairinen et al. (Citation2021), that research which investigates and reflects on SIA processes and methods can make an important contribution to SIA practice.

Regeneration, in broad terms, refers to ‘development that is taking place in cities and towns’ (Tallon Citation2013, p. 4) where the impetus for regeneration activity is a ‘desire to reconfigure the form and operation of cities [and small towns and districts] in response to a series of social, economic and environmental challenges’ (Ruming Citation2018, p. 3). Regeneration raises a complex set of issues with respect to the social, economic, cultural and environmental impacts of development and seeks to identify outcomes consistent with environmental and social sustainability. The drive for regeneration in the Waitaki District (population 22,000 in 2018) and its principal town of Oamaru (population 13,000 in 2018) came from a series of external events from the 1980s, including neoliberal economic policies that affected rural areas (Robertson et al. Citation2008), as well as natural events in the form of successive severe droughts. Some of the community initiatives we encountered had an extended period of gestation over this time period, especially those developed to repurpose heritage buildings and the town’s waterfront (Mackay et al. Citation2018).

Hybrid method

As a first step in the research, we adopted a longitudinal perspective, to build a theory-based understanding of community change. The research team was able to draw on knowledge developed since the 1980s in project social impact assessments and community studies to interpret the social context of the region longitudinally accross the whole Waitaki Valley (Taylor et al. Citation2008, Citation2020). A strong social-scientific theoretical base was essential to scoping the case-study, establishing the baseline and carrying out the ongoing analysis. Useful explanatory perspectives, including those to which the research team has contributed, included the concepts of: social-economic cycles in natural resource-based communities (Taylor et al. Citation2001); the global multifunctional countryside (Mackay et al. Citation2014; Perkins et al. Citation2015; Mackay and Perkins Citation2019); and regeneration of rural districts and small settlements (Perkins et al. Citation2019). These perspectives allowed us, as per the discussion of realist evaluation above, to propose how regeneration mechanisms were working themselves out in the Waitaki Valley and Oamaru to produce a range of networked outcomes.

Consistent with methods of social impact assessment, the research was scoped to characterise regeneration initiatives in Oamaru and the wider district, and the periods (and particular contexts) over which they developed. The key stakeholders in each initiative were also identified and interviewed using a semi-structured method. Secondary, archival data included historical records, documents, reports and studies, and local media coverage, which together helped us build a strong contextual picture of the social baseline and Oamaru’s main regeneration initiatives and their level of integration. Quantitative data also helped to provide a broad understanding of the social baseline, such as levels of employment (reflecting economic cycles), population demography (such as an increasingly ageing population) and ethnicity/length of residence (such as an increasing presence of migrant workers in agriculture and food processing). Census data were an important source of quantitative information for this baseline along with economic and employment statistics. Most of these data were organised into a spatial (GIS) framework, allowing for thematic mapping. Together, these sources helped to build the social baseline of the town and district.

We supplemented this social baseline with primary qualitative interviews and participant observation along with updated quantitative data, as the research progressed. This allowed us to understand the complex and shifting characteristics of the places under study and the processes of change underway such as changes in employment and demography. In-depth interviews were undertaken, with 25 local stakeholders who were involved in attempts to revitalise the town and district. In this method, story-telling by key people with a longitudinal perspective of change proved essential, consistent with the finding of Vanclay (Citation2013) in respect to Australian regional development. The majority of interviews were recorded and transcribed for detailed review along with written field notes and recorded observations. The researchers also met frequently with key organisations and groups and utilised participant observation through interactions that emphasised the co-production of knowledge, which facilitates and empowers the input of all participants into the research and pays particular attention to the contribution of local knowledge (Djenontin and Meadow Citation2018).

The evaluative questions that featured in the interviews with stakeholders who were involved in the attempts to revitalise the town, included: what are you trying to achieve, what were your aspirations, how did you go about it and what was the timeframe, who was involved, who supported you, including funding, what was achieved and how did you know what the outcomes were, and what problems were encountered? These questions were targeted at understanding project effectiveness and the degree to which regeneration had improved social outcomes. The impact assessment dimension of these interviews helped us to understand the impacts of particular initiatives and projects on people and communities. The questions asked here were: what were the social, economic and environmental impacts of your initiatives, how did you measure these, were impacts assessed a priori and did this assessment contribute to project design and implementation, and what ex post monitoring, mitigation or management has taken place? By asking these two sets of questions the research therefore utilised methods drawn both from realist evaluation and social impact assessment. Put simply, the evaluative dimension of the research asked the question: what makes regeneration successful, or not, in respect to the process of social change and the effectiveness of the approaches taken? The assessment dimension interpreted the impacts of regeneration on people and communities in terms of longer-term outcomes for social wellbeing.

Consistent with the importance of participatory approaches, we adopted throughout a co-production of knowledge perspective (Perkins et al. Citation2019). This meant that local knowledge and data sources gained during the assessment were iteratively presented to research participants as the project unfolded. This approach was designed to facilitate the input of all participants and paid particular attention to incorporating local knowledge and participant empowerment into practical applications through community strategies (Djenontin and Meadow Citation2018). We acknowledge here the ready involvement of the Waitaki District Mayor, Council members, Council staff, business operators and community leaders in sharing information with us, from data sets to anecdotes. These people represented a range of interests across economic development, hospitality and tourism, heritage conservation, social services, planning and environmental management.

Capacity in local data collecting and using social data seems an obvious pre-requisite to co-production of knowledge if the ‘co’ has any real meaning. Co-production of knowledge goes beyond limited concepts of engagement and requires building of relationships and the confidence of all parties to take part in research processes in a constructive and ethical way. In the Oamaru case, the research team continued to share data sets and knowledge and has refocused the research scope over time according to local needs. For example, housing affordability was identified as an issue for low-income, migrant workers living in the town and engaged in food processing. This housing issue became the subject of a formative (strategic) evaluation by a specially convened community task force. The researchers participated in the taskforce, helped to design a community housing survey by the group and co-produced data on demography, housing and the rental market (Taylor et al. Citation2020).

The regeneration initiatives

The hybrid method allowed us to identify and characterise three sets of regeneration initiatives, the aspirations of those involved in their development and their impacts and successes (Mackay et al. Citation2018).

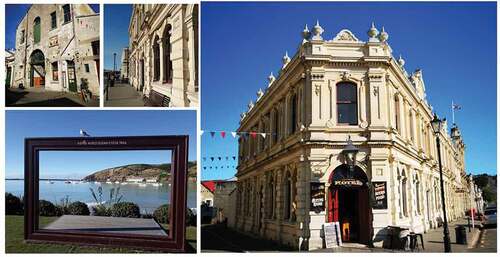

Oamaru victorian heritage and harbour precinct

The first regeneration initiative identified in our research was the Victorian heritage precinct incorporating Oamaru’s limestone buildings in the harbour area and along the main street (). Work on this precinct began in the difficult period of economic restructuring experienced in rural New Zealand during the 1980s and 1990s (Mackay et al. Citation2009). The built heritage aspect of the development included public facilities that led to business start-ups along the harbour front and in the heritage precinct, including a pub, cafes, artisan foods, crafts, antique shops and a craft brewery. It also included the successful development of a major little blue-penguin eco-tourist attraction and visitor facility since the 1990s. Distinct themes of Victoriana and steam punkFootnote1 emerged alongside the renovated buildings, including festivals and other community events. Stories about this extended period of economic, social and cultural regeneration were interwoven with life histories and work histories. They included people who migrated to Oamaru because of interests such as Victoriana and the attractions of an enhanced living environment. There were also those who returned to Oamaru, attracted by the historical and heritage associations, the availability of a combination of private restorations and community endeavours, and by attractive and affordable housing.

The research approach relied on in-depth interviews, participant observation, extensive document research and review of demographic and employment data. In summary, the emphasis in this part of the research was on a combination of evaluation and impact assessment. The methodological emphasis in the set of initiatives examined was on understanding the stories of community-led regeneration over an extended period and the people who participated through leadership and entrepreneurship. A key impact identified was the emergence of a number of outlets promoting food and beverages and local artisanship in heritage sites once sufficient momentum was achieved and encouraged entrepreneurial activity. A key evaluative lesson was the need to allow scope in heritage regeneration for diverse interests, local groups and organisational efforts to take part.

The Alps to Ocean cycle trail (A2O)

The second initiative was a regional cycle trail known as the Alps to Ocean or ‘A2O’ (Wilson Citation2016; Mackay and Taylor Citation2019), an excellent example of the multi-functional diversification of the New Zealand’s countryside. The trail starts in the Southern Alps at Aoraki-Mt Cook, transverses the length of the Waitaki catchment, and ends in the Oamaru Harbour heritage precinct (see ). The trail was initiated and organised by enthusiastic local leaders who worked with the Waitaki District Council, the Department of Conservation, Meridian Energy and local businesses. The A2O was in part funded by the National Cycleway Project Nga Haerenga – The New Zealand Cycle Trail (Bell Citation2018) and came to fruition over the last five years. The trail provided an opportunity for local leaders to plan and implement an economic and recreational regeneration project, in a much shorter timeline than the heritage-focussed local regeneration activities noted above. The cycle trail project has also stimulated numerous other individual projects and business start-ups such as the renovation and repurposing of two disused rural pubs, several outlets for local vineyards and small-scale accommodation. Interviews revealed strong interest in using the trail better as a link to the Oamaru heritage precinct, and as a means of promoting regional offerings of food and wine through a geo-gastronomy emphasis (Fitt Citation2020).

An understanding of this initiative again required an evaluative dimension, so gaining an understanding of how the cycle trail drew on community leadership and resources across the district for successful implementation, supported, in this case, by agencies of local and central government. The initiative was also assessed for its ex post impacts on local people and communities as a result of increasing visitor numbers along the trail, including employment and economic opportunities in small towns, providing a basis for ongoing monitoring and evaluation (Mackay and Taylor Citation2019). The method here emphasised a combination of in-depth interviews, community studies, secondary data and GIS analysis.

GeoPark

The third initiative is the Waitaki Whitestone GeoPark. The GeoPark began as a local and then district initiative, organised by enthusiasts who built a fossil display and information centre in the village of Duntroon (Mackay et al. Citation2018; Fitt Citation2020). The GeoPark is a district-wide set of local attractions and trails incorporating varied geology extending from the clay cliffs near Omarama to the Macraes gold mine near Palmerston (see the District in ). It is the outcome of long-standing efforts by farmers and residents to display and promote local geological and fossil features, and heritage sites (). Recently, attempts have been made to have the Park accredited by UNESCO and included in an international network of GeoParks, illustrating the further development of Woods (Citation2011) ‘global countryside’ (also see Mackay et al. Citation2014). This work was led by the Waitaki District Council in conjunction with partners such as the area’s Māori tribe, Ngāi Tahu. The A2O and Oamaru Harbour and Heritage Precinct will be part of the GeoPark (). While this regeneration initiative is led by the Council, it still depends heavily on the efforts of individuals and community groups to create initiatives such as information centres, interpreted sites and trails, and businesses that take advantage of the Park for the purpose of promotion to visitors.

Using the hybrid method, analysis of this initiative emphasised formative evaluation in the sense that the research investigated ways that key stakeholders and communities could work more effectively to coordinate their actions and adopt an integrated approach to development of the Geopark, well informed by a combination of qualitative and quantitative data. The impact focus was on the effects of increasing visitor numbers, particularly at sites that are vulnerable to effects on ecological, geological, heritage and cultural values, or with limited social carrying capacity. This involved ex post knowledge of effects, such as landowner observations of stress from visitor numbers at certain sites, and a priori predictions about the need to manage impacts if visitor numbers increase over time due to international accreditation.

Discussion: evaluating and assessing the regeneration initiatives

All three of these initiatives were to a significant degree judged successful by residents and other stakeholders. They did, however, reveal a number of impacts and issues, requiring mitigation and careful management through strategic approaches, such as the housing issues identified. Some of these issues involved longer-term chains of effects and change processes such as a shift in cultural diversity through an increase in migrant workers, in turn creating changing demands for types of housing. A frequent concern was about the pressure of increasing numbers of visitors, domestic and international, on the limited visitor infrastructure of the area – although the Covid19 pandemic has changed this situation, at least in the medium term, by disrupting flows of international visitors while increasing the numbers of domestic visitors. At the time of the research, participants raised longer-term issues of sustainable tourism, including the availability and suitability of accommodation, ecological and physical impacts at some sites such as noise, parking, visual impacts and waste, and the need to recruit suitably skilled labour at relatively low wage rates – often to jobs that attract immigrant workers on restricted visas. An evaluative issue commonly raised was the need to coordinate and support the efforts of disparate groups and businesses without burdening them with unnecessary regulation such as rules around access to geological or heritage features (Mackay et al. Citation2018; Fitt Citation2020).

Interestingly, neither a strong evaluation nor a strategic assessment framework was in place for any of the initiatives examined, beyond those associated with limited, site-specific consents. In particular, these regeneration initiatives lacked strategic assessment at a sectoral or programme level. The stakeholders who had initiated these initiatives had established, at least vaguely, a set of desired outcomes such as heritage protection or opportunities for new business, local employment and recreation. But there were no well-defined outcomes or evaluation criteria. The research also identified the need for a stronger focus on social outcomes in planning and managing change through district and regional plans.

Given the above issues, some stakeholders identified a need for monitoring and ongoing social impact management and evaluation of local community initiatives. This monitoring could be part of a formal social impact management plan (Holm et al. Citation2013) for particular projects or programmes, as part of implementing a proposal or to gather information relevant to current and future funding arrangements. It could also be ongoing monitoring by the local council as part of their obligations under current legislation to monitor outcomes related to the environment (e.g., potable and recreational water quality) and social wellbeing (e.g., employment creation, housing needs and social cohesion). This monitoring effort would be in addition to the limited monitoring already undertaken by tourism operations and organisations and Statistics New Zealand (e.g., visitor numbers) and by economic development agencies (e.g., employment) or environmental agencies (e.g., land use and water quality).

But when asked who could do and pay for localised analysis, no clear answer was provided. One important view was that there was a need to build community capacity in assessment and evaluation. This capacity building is consistent with the increasing emphasis of central government policy on collaborative and community driven approaches to local issues, including for environmental management, local employment generation and the provision of housing and social services. Most recently this evidence-based approach is found in community driven Covid19 pandemic responses in the district such as a small-scale survey of the needs of migrant workers (Pacific Islands households) conducted by a community group in Oamaru. It is also consistent with the New Zealand Treasury Living Standards Framework,Footnote2 which is designed to promote ‘thinking about policy impacts across the different dimensions of wellbeing.’ What is missing from this emphasis in government policy is the allocation of funds and other resources to support local capacity building in project and programme design and evaluation, as an essential part of deciding on levels of funding.

Our case study also highlighted the importance of benevolent social entrepreneurs in rural and small-town regeneration. These people use their own resources to generate and sustain community initiatives, including voluntary time to collect and analyse data. The skills, time and energy of these people and associated social enterprises are paramount to project and programme successes. Extending local capacity in assessment and evaluation is important because of the complex relationship between community capacity and resilience. The ability of communities to bounce back from adverse events (Lovell et al. Citation2018), as is currently taking place with Covid19 recovery, depends on a high level of local capacity and participation.

Conclusion

This paper reports an experimental approach to combining methods of realist evaluation and social impact assessment in order to strengthen a mixed method approach to social impact assessment. The approach emphasises strong community engagement and effective use of qualitative data as opposed to a formulaic, tick-box approach heavy with quantitative data. The approaches of social impact assessment and evaluation were applied in the research to better understand the outcomes of rural and small-town regeneration initiatives. The combination of methods ensured that there was a focus on evaluating the outcomes of regeneration initiatives, what worked, why and for whom, along with a focus on the impacts of those initiatives and how they should be identified, monitored and managed to enhance community outcomes.

The fields of social impact assessment and realist evaluation typically utilise methods that generate quantitative and qualitative data. They both benefit from qualitative methods and intensely practical hypothesis generating work to investigate chains of effects and longer-term change processes. We observed significant connections between realist evaluation and social impact assessment and found there are implications for future practice of social impact assessment.

A common feature of a hybrid approach using social impact assessment and realist evaluation methods is the use of quantitative and qualitative data to develop a deep understanding of social context and a conceptual basis to understand cause and effect relationships and broader processes of social change. Both practitioner groups emphasise how the voices of all parties need to be included in assessing the likelihood and significance of any impact or outcomes. This requires them to engage in qualitative field interviews, but most importantly demands critical reflection, that they sit back and ask why they are using particular methods, who with, the key questions asked and how they can tell the full story in a dynamic way.

The combined approach is compatible with the co-production of knowledge. This is about more than sharing data and experiences between researchers and research users. It is more than using local knowledge or involving local stakeholders. Co-production also requires building relationships alongside critical reflection on who has the capacity, resources and power to generate and use knowledge. This approach raises questions about the need to build local capacity to undertake research, assessment and evaluation, consistent with the call of Bice (Citation2020, p 106) for a greater emphasis on community-based social impact assessments that fully address community experiences of change in an increasingly complex world.

Our research has co-produced knowledge for use in our research communities, and in other rural areas and small towns interested in multi-dimensional regeneration. The combination of social impact assessment and realist evaluation allowed us to narrate stories about the outcomes, consequences and success of regeneration initiatives in the Waitaki District and town of Oamaru. The approach helped to develop ideas that communities can use in shaping the future of their rural regions and towns.

We hope this paper helps advance debates among social impact assessment practitioners about how the methods of assessment and realist evaluation can be combined. If done well, this hybrid model, with its strong participatory approach, will enable practitioners better to interpret community aspirations and initiatives, consider programme impacts and their mitigation and management, understand success, and ultimately help communities enhance their social and environmental wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities: Ko ngā wā kaingā hei whakamahorahora: New Zealand National Science Challenge and the collaboration of Ms Helen Algar QSM of Safer Waitaki. We also appreciate the helpful comments of the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Alberts RC, Retief FP, Roos C, Cilliers DP, Arakele M. 2020. Re-thinking the fundamentals of EIA through the identification of key assumptions for evaluation. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 38(3):205–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1676069.

- Andre P, Enserink B, Connor D, Croal P. 2006. Public participation best practice principles. USA: International Association for Impact Assessment. Special Publication Series No. 4.

- Aucamp I, Woodborne S. 2020. Can social impact assessment improve social well-being in a future where social inequality is rife? Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 38(2):132–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1676068.

- Aucamp I, Woodborne S, Perold J, Bron A, Aucamp S. 2011. Looking beyond impact assessment to social sustainability. In: Vanclay F, Esteves A, editors. New directions in social impact assessment: conceptual and methodological advances (chapter 3, pp. 38–58). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Baines J, McClintock W, Taylor CN, Buckenham B. 2003. Using local knowledge. In: Becker H, Vanclay F, editors. International handbook of social impact assessment, conceptual and methodological advances (chapter 3, pp. 26–41). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Chapter 3.

- Baines J, Taylor CN, Vanclay F. 2013. Social impact assessment and ethical research principles: ethical professional practice in impact assessment part 11. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 32(4):254–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.850306.

- Becker HS. 1998. Tricks of the trade: how to think about your research while you’re doing it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bell C. 2018. ‘Great Rides’ on New Zealand’s new national cycleway: pursuing mobility capital. Landscape Res. 43(3):400–409. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1316366.

- Bice S. 2020. The future of impact assessment: problems, solutions and recommendations. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal.38(2):104–108.doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1672443.

- Bice S, Moffat K. 2014. Social licence to operate and impact assessment. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 32(4):257–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2014.950122.

- Blumer H. 1969. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Burdge R. 2004. Participative and analytical impact assessment. Burdge R, Colleagues, editors. The concepts, process and methods of social impact assessment (chapter 8, pp. 113–128). Wisconsin: Social Ecology Press.

- Burdge R, Johnson S. 2004. The comparative social impact assessment model. Burdge R, Colleagues, editors. The concepts, process and methods of social impact assessment (chapter 2, pp. 15–29). Wisconsin: Social Ecology Press.

- Djenontin I, Meadow A. 2018. The art of co-production of knowledge in environmental sciences and management: lessons from international practice. Environ Manage. 61(6):885–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1028-3.

- Fischer TB, Cave B. 2018. Health in impact assessments – introduction to a special issue. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 36(1):1–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2017.1363976.

- Fitt H. 2020. Geogastronomy in the Waitaki Whitestone aspiring Geopark: a snapshot of sector perspectives on opportunities and challenges. LEAP Research Report 234, Lincoln University, New Zealand.

- Holm D, Ritchie L, Snyman K, Sunderland C. 2013. Social impact management: a review of current practice in Queensland, Australia. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 32(3):214–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.782704.

- Kelly A. 2019. Evaluation in rural communities. London: Routledge.

- Kennedy JC. 2009. Culture and leadership in New Zealand. In: Chhokar J, Brodbeck FC, House R, editors. Culture and leadership across the world: the globe book of in-depth studies of 25 societies (chapter 12, pp. 397–432). Mahwah (New Jersey): Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

- Lofland J, Snow D, Anderson L, Lofland LH. 2006. Analysing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont (CA.): Thomson Wadsworth.

- Lovell S, Gray A, Boucher S. 2018. Economic marginalization and community capacity: how does industry closure in a small town affect perceptions of place? J Rural Stud. 62:107–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.07.002.

- Mackay M, Perkins H. 2019. Making space for community in super-productivist rural settings. J Rural Stud. 68(8):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.012.

- Mackay M, Perkins HC, Espiner S. 2009. The study of rural change from a social scientific perspective: a literature review and annotated bibliography. New Zealand: Lincoln University.

- Mackay M, Perkins HC, Taylor CN. 2014. Producing and consuming the global multifunctional countryside: rural tourism in the South Island of New Zealand. In: Dashper K, editor. Rural tourism: an international perspective. (chapter 2. pp. 41–58). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Mackay M, Taylor CN. 2019. Changing gear: impacts of tourist activity around a new cycle trail – towards more sustainable outcomes. Paper prepared for the International Association for Impact Assessment Annual Meeting. Brisbane.

- Mackay M, Taylor CN. 2020. Understanding the social impacts of freshwater reform: a review of six limit setting social impact assessments. AgResearch Report RE450/2020/005 for New Zealand Ministry for the Environment. Christchurch (New Zealand): AgResearch Lincoln Research Centre.

- Mackay M, Taylor CN, Perkins HC. 2018. Planning for regeneration in the town of Oamaru. Lincoln Planning Review. 9(1–2):20–32.

- Middleton L, Rea H, Pledger M, Cumming J. 2019. A realist evaluation of local networks designed to achieve more integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 19(2):1–12. 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.4183.

- Morgan RK, Taylor CN. 2021. Environmental impact assessment in New Zealand. In: Fischer TB, Gonzalez A, editors. Handbook on strategic environmental assessment (chapter 21, pp. 330–346). United Kingdom: Edward Elgar.

- Parsons R. 2020. Forces for change in social impact assessment. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 38(4):278–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1692585.

- Pawson R. 2013. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. London: Sage.

- Pawson R, Manzano-Santaella A. 2012. A realist diagnostic workshop. Evaluation. 18(2):176–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389012440912.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. 1997. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage.

- Perkins HC, Mackay M, Espiner S. 2015. Putting pinot alongside merino in Central Otago, New Zealand: rural amenity and the making of the global countryside. Journal of Rural Studies 39. 39:85–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.03.010.

- Perkins HC, Mackay M, Levy D, Campbell M, Taylor N, Hills R, Johnston K. 2019. Revealing regional regeneration projects in three small towns in Aotearoa—New Zealand. N Z Geog. 75(3):140–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12239.

- Roberts R. 2003. Involving the public. In: Becker HA, Vanclay F, editors. The international handbook of social impact assessment: conceptual and methodological advances. USA: Edward Elgar; p. 258–277. Chapter 16.

- Robertson N, Perkins HC, Taylor CN. 2008. Multiple job holding: interpreting economic, labour market and social change in rural communities. Sociol Ruralis. 48(4):331–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00470.x.

- Ruming K. 2018. Urban regeneration in australia: Policies, processes and projects of contemporary urban change. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sairinen R, Sidorenko O, Tiainen H. 2021. A research framework for studying social impacts: application to the field of mining. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 86:1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106490.

- Slootweg R, Vanclay F, Van Schooten M. 2001. Function evaluation as a framework for the integration of social and environmental impact assessment. Impact Assessment & Project Appraisal. 19(1):19–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/147154601781767186.

- Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit (2015). Evaluation standards for aotearoa New Zealand. Accessed 20 February 2021 at: https://www.anzea.org.nz/app/uploads/2019/04/ANZEA-Superu-Evaluation-standards-final-020415.pdf

- Tallon A. 2013. Urban regeneration in the UK. London: Routledge.

- Taylor CN, Fitzgerald G, McClintock W. 2001. Resource communities in New Zealand: perspectives on community formation and change. In: Lawrence G, Higgins V, Lockie S, editors. Environment, society and natural resource management, theoretical perspectives from Australasia and the Americas. (pp. 137–155). Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar.

- Taylor CN, Goodrich C, Fitzgerald G, McClintock W. 2003. Undertaking longitudinal research. In: Becker H, Vanclay F, editors. Handbook of social impact assessment, conceptual and methodological advances (chapter 2. pp. 13–25). Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar.

- Taylor CN, Goodrich CG, Bryan CH. 2004. Social assessment: Theory, process and techniques. Third ed. Middleton (Wisconsin): Social Ecology Press.

- Taylor CN, Mackay M. 2016a. Practice issues for integrating strategic social assessment into the setting of environmental limits: insights from Canterbury, New Zealand. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 34(2):110–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2016.1147261.

- Taylor CN, Mackay M. 2016b. Social impact assessment in new zealand: legacy and change. New Zealand Sociol. 31(3):230–246.

- Taylor CN, Perkins HC, Maynard L. 2008. A longitudinal, catchment wide, research base for strategic and project social assessments. Paper prepared for the International Association for Impact Assessment Annual Meeting, Perth. 3-9 May.

- Taylor CN, Mackay M, Perkins HC. 2016. Social impact assessment for community resilience in the upper waitaki river catchment, New Zealand. Paper prepared for the International for Impact Assessment International Conference, Nagoya, Japan, May 2016.

- Taylor CN, Mackay M, Russell K. 2020. Searching for community wellbeing: population, work and housing in the town of Oamaru. Working paper 20-08a for Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities Thriving Regions, 36pgs. Christchurch: AgResearch/BBHTC.

- Tester FJ, Mykes W. 1981. Social impact assessment: theory, method and practice. Calgary: Detselig.

- Vanclay F. 2013. The potential application of qualitative evaluation methods in European regional development: reflections on the use of performance story reporting in Australian natural resource management. Reg Stud. 49(8):1326–1339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.837998.

- Vanclay F. 2020. Reflections on social impact assessment in the 21st century. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal. 38(2):126–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1685807.

- Vanclay F, Esteves AM, Franks DM. 2015. Social impact assessment: Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects. Fargo (USA): International Association for Impact Assessment.

- Wilson J. 2016. Alps 2 ocean cycle trail: user survey 2015-16. Technical Report, Land and Environment and People research Report Series, Lincoln University, New Zealand.

- Woods M. 2011. Rural. London and New York: Routledge.

- World Bank Group. 2019. World Bank Group evaluation principles. Washington, DC: World Bank, International Finance Corporation, Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency in collaboration with Independent Evaluation Group.