ABSTRACT

We consider the adequacy of the legislative and administrative provisions for environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) in Uganda. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) legislation was enacted in Uganda in 1995. Although it was intended that social impacts would also be considered, the nomenclature, organizational culture and practice of EIA has given an over-emphasis to biophysical issues, with social issues being under considered. Lack of explicit instructions about how to assess social impacts and the positioning of ESIA too late in the project cycle limit the ability of social issues to be properly considered. From document analysis, an on-line survey, in-depth interviews, reflexive practice, and a literature review, we found that there was inadequate public participation, poor follow-up, low levels of capacity in all stakeholders, and political interference in the project approval process. To improve the effectiveness of ESIA in Uganda and other developing countries, we make recommendations to address the challenges facing ESIA practice.

1. Introduction

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA) have been around for over half a century and are now applied in most countries around the world, often in the form of Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) (Wood Citation2003; Dendena and Corsi Citation2015; Vanclay Citation2020). However, whether EIA and ESIA are serving their purposes as a tool that identifies the potential environmental and social impacts of a proposed development, assesses different options prior to a planning decision, and ensures better development outcomes is debatable (Morgan Citation2012; Joseph et al. Citation2015; Khosravi et al. Citation2019; Ijabadeniyi and Vanclay Citation2020). Although ESIA is seen by some commentators as playing a key role in making projects environmentally and socially acceptable (Arts et al. Citation2012; Momtaz and Kabir Citation2013), its effectiveness has been debated for many decades (Sadler Citation1996; Cashmore et al. Citation2004, Citation2010; Ahmadvand et al. Citation2009; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013, Citation2020; Hanna et al. Citation2014; Loomis and Dziedzic Citation2018). By looking at the use of ESIA in Uganda, we consider how the effectiveness of ESIA might be enhanced, especially in a developing country context.

The EIA/ESIA concept has evolved from its origins in the USA in the late 1960s (Morgan Citation2012; Vanclay Citation2015, Citation2020). By the early 1990s, over 40 countries had implemented EIA legislation (Ortolano and Shepherd Citation1995), and ESIA has since become generally required in all developing countries because development banks require ESIAs for projects they are considering to finance (Vanclay and Hanna Citation2019). SIA began in the 1970s alongside EIA (Esteves et al. Citation2012). Originally, SIA was conceived as a regulatory tool like EIA, although only few jurisdictions formally required it (Vanclay Citation2020). Over time, however, SIA become normal practice in most companies, albeit in the form of social performance management or due diligence, and is now demanded by all reputable financial institutions (Vanclay and Hanna Citation2019). Thus, ESIA is an established international requirement. As at October 2021, there were over 9,500 hits in Google Scholar for the search term ‘environmental and social impact assessment’.

In developing countries, use of ESIA has typically been in response to the funding requirements of development finance institutions, although most developing countries do have EIA legislation (George et al. Citation2020). Although the stated ESIA procedures are generally similar around the world, the quality of application of the process varies greatly (Kolhoff et al. Citation2009; Suwanteep et al. Citation2016). In Uganda, EIA became formally established with the National Environmental Act 1995 (Uganda Citation1995), and was replaced by the National Environment Act 2019 (Uganda Citation2019), which gave greater attention to social and other emerging issues. However, there is still a lack of information in the Ugandan legislation and generally regarding the specific requirements, positioning and role of ESIA in project implementation. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the Ugandan ESIA system and make recommendations for improvement that will likely be useful to all developing countries.

2. ESIA in Uganda

Uganda was a colony of the United Kingdom up until 1962. Between 1962 and 1986, there was much political turmoil. Yoweri Museveni – who was re-elected President for the fifth time in January 2021 – seized power in 1986, which led to a period of relative political stability, allowing the country to develop, although amidst many concerns (Ogwang et al. Citation2019; Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2021a, Citation2021b). In 1991, the Government of Uganda implemented the National Environment Action Plan, a participatory process to improve environmental governance (Kahangirwe Citation2011). This plan led to the development of the National Environmental Act 1995 (now replaced by the National Environment Act 2019). The 1995 Act required EIA for most proposed projects and it established the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) as the agency responsible for overseeing all aspects of the environment, including the review of ESIAs conducted for projects (Ecaat Citation2004; Kahangirwe Citation2011). EIA Regulations (NEMA Citation1998) were prepared by NEMA and were revised in 2020 (NEMA Citation2020).

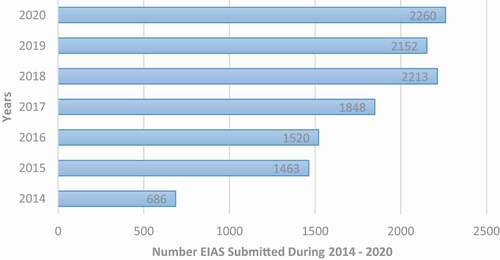

In the National Environment Act 2019, Schedule 5 listed the projects for which ESIA was mandatory, while Schedule 4 listed the types of project for which a ‘project brief’ (rather than a full ESIA) could be submitted to NEMA and to an appropriate ‘Lead Agency’. A Lead Agency refers to the ministry, department, agency or local government in which certain specific functions of control or management of some segment of the environment are vested (for example water, health, transport energy). The EIA Regulations also required that any major changes or extensions to existing projects also be subject to an ESIA process, especially if landtake is required or there was to be a significant change in technology. With Uganda having a growing economy and strong demand for development (Kahangirwe Citation2012; Ogwang et al. Citation2018; Ogwang and Vanclay Citation2021b), the number of projects having ESIAs submitted for approval has increased considerably over recent years (see ).

The prescribed stages in an EIA process differ between jurisdictions but generally include screening, scoping, assessment, reporting, review, decision making, and follow-up (Wood Citation2003; Therivel and Wood Citation2018). The Ugandan legislation requires that all project types listed in Schedules 4 and 5 of the National Environment Act undergo a preliminary assessment (screening) to determine whether a full ESIA is required. Not all development projects will necessarily cause adverse effects to the environment, and hence not all proposed projects will have to undergo the entire ESIA process. presents the ESIA process in Uganda, as specified in the EIA guidelines (NEMA Citation1997).

The EIA guidelines (NEMA Citation1997) grouped the steps into three key phases: screening; production of the environmental impact statement; and decision-making (see ). In Uganda, screening is a preliminary assessment undertaken by the proponent to determine if a proposed project or activity will or will not likely have a significant impact on the environment and to consider whether there are mitigation measures for any adverse impacts that can readily be applied. If there are likely to be significant impacts and mitigation measures cannot be identified, then a detailed environmental impact study must be conducted. The screening step in Uganda differs from normal international procedure in that: there is no requirement to submit screening reports to any agency; there is no review of these decisions by the environment agency (e.g. NEMA); and there is no official record of such decisions.

The second phase (environmental impact study) deals with the identification of possible impacts. It expects public consultation, especially with the communities likely to be affected by the proposed project. It involves compiling a detailed description of the existing environment and activities of local residents. Stakeholder involvement is crucial, as it gives those who will be affected an opportunity to present evidence about the potential consequences of the project and to provide input about how to minimize impacts.

The third phase is the decision-making stage, in which a decision to approve or reject a proposed project is made by NEMA and any approval conditions are determined. Officially, a proponent would only be allowed to proceed with implementing a project after such an approval decision is made. In , the line at the bottom of the schema, ‘action by developer’, is intended to imply the conditions that might be imposed on project approval and other actions such as monitoring. The EIA Regulations (NEMA Citation2020) normally require that developers carry out an evaluation or audit of their project to ensure that issues identified in the ESIA report are satisfactorily addressed. As specified in Regulation 46 and Section 122(2) of the 2019 Act, monitoring of projects is essential, as this ensures that promised mitigation measures and approval conditions are complied with.

Despite all this detail in the National Environment Act, the EIA Regulations and the Guidelines, there are many shortcomings in the ESIA process in Uganda (Ecaat Citation2004; Kahangirwe Citation2011; George et al. Citation2020), hence the need to assess the Ugandan ESIA system and make recommendations to improve ESIA practice.

3. Methodology

To establish criteria by which to assess the ESIA system in Uganda, reviews of EIA in different countries around the world were considered (including Wood Citation2003; Ecaat Citation2004; Nadeem and Hameed Citation2008; Ahmadvand et al. Citation2009; Dominik et al. Citation2010; Kahangirwe Citation2011; Momtaz and Kabir Citation2013; Kamijo and Huang Citation2016; Aung Citation2017; George et al. Citation2020). This revealed that a wide range of criteria has been used, varying according to the objectives of each research team. From our literature search, we developed a set of criteria grouped under four themes: adequacy of legislative provisions; administrative arrangements; the ESIA process; and the role of the environment agency (NEMA) in facilitating project implementation (see ). We assessed the Ugandan ESIA system against our criteria by using data collected from a literature review, document analysis, an on-line survey, and interviews undertaken between July 2020 and March 2021. indicates which sources of data were used to consider each criterion. Essentially, comprises the questionnaire that was used in the survey and interviews, with the individual questions covering the assessment criteria and some open-ended questions. The survey/questionnaire was pre-tested with a small group of close professional contacts (approximately one from each target group), and was fine-tuned prior to being finalised.

Table 1. Questionnaire to assess the ESIA system of Uganda and data sources

A document analysis was conducted of all documents relevant to the Ugandan ESIA system, including legislation, regulations, and guidelines. All published literature about the Ugandan ESIA system was reviewed, primarily identified by using the Google search engine. Furthermore, the literature on the effectiveness of EIA systems around the world was also reviewed, primarily using Scopus.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020, when the research was conducted, it was thought it would be difficult to organise interviews. Therefore, an online survey of people involved in the Ugandan ESIA system was established. Starting in July 2020, potential participants were sent an invitation to complete an online survey using Google Forms. The list of names of potential respondents was compiled by various means including: personal contacts; environmental practitioners (EPs) publicly listed on the NEMA website; relevant key staff of lead agencies and NEMA (which could be established from their websites or by our personal knowledge); Ugandan academics teaching ESIA at University level (both personal contacts but also identifiable from the literature review); and representatives of NGOs (identifiable by their public profile, for example by having provided input into ESIA processes). Over a period of nine months, a total of about 80 people were sent invitations to complete the survey. One follow-up email was sent several weeks later to those who had not yet responded. A target of 50 completions had been set, and active recruiting stopped when this target was reached. The ultimate composition of the people who participated in the research included: 27 environmental practitioners (EPs); 6 proponents; 4 NEMA staff; 4 lead agency staff; 5 academics, and 4 representatives of NGOs.

In the email invitation to participate, people were given the option to have an interview instead of completing the online survey. In Uganda, most people do not have reliable strong internet access from home, making completion of the online survey tedious. Consequently, 35 of the 50 participants indicated that they preferred to be interviewed (using WhatsApp, Zoom or in person at their choice). The content of the interview was substantially similar to the online survey in terms of the questions asked, but the answers given in interviews were more detailed than in the online survey. The interview also enabled some additional probing questions to be asked.

The interviews were not audio-recorded as this would not be acceptable in the Ugandan context. However, all principles of informed consent and ethical social research were observed (Vanclay et al. Citation2013). A questionnaire (effectively the online survey form) was used for each interview, with the lead author annotating the responses to each question on the form. This information was later coded and transferred to an Excel spreadsheet. Where it was noticed that there was missing or unclear information (for an interview or online survey completion), the lead author re-contacted the participant to clarify what was meant.

It should also be noted that the lead author of this paper is an experienced environmental practitioner in Uganda. Although the research in this paper is primarily based on the interviews with other practitioners, some observations in the paper derive from the lead author’s personal experience in writing ESIA reports and auditing the implementation of ESIAs in Uganda.

4. Assessment of Uganda’s ESIA system

This section presents our findings, structured by the criteria themes used in : adequacy of legislative provisions for ESIA; administrative arrangements for ESIA; components of the ESIA process; and the role of NEMA in facilitating project implementation. In addition, some general comments that arose from the open-ended questions are also discussed.

4.1. Adequacy of legislative provisions for ESIA

Most respondents (92%) agreed that Uganda had a clear legal basis for ESIA, although two people (4%) thought that the regulations were not adequate, primarily because they do not cover all issues relevant to ESIA. Another two people (4%) neither agreed nor disagreed because they were not particularly familiar with the legal framework. Although the legislation was regarded as being adequate, many respondents stated it only required proponents to prepare an ESIA report and submit it to NEMA – and that significant inadequacies were: there was no checking of details in the reports; and there was no follow-up or compliance mechanism to ensure that promised mitigation measures were implemented and working effectively. Some respondents noted that Section 157 of the National Environment Act (2019) provides for a fine or imprisonment to be imposed if a proponent commenced a project without approval. However, as the fines are relatively low, and no one is ever imprisoned, many proponents commence construction of projects before having formal approval and sometimes without doing an ESIA, fully accepting that they might have to pay a fine. Most of the proponents who were interviewed claimed to have commenced projects before approval had been given, usually receiving approval later, with no fine or conviction being imposed. Thus, it seems that ESIA is implemented only to fulfil legal obligations and does not inform project design.

4.2. Administrative arrangements for ESIA

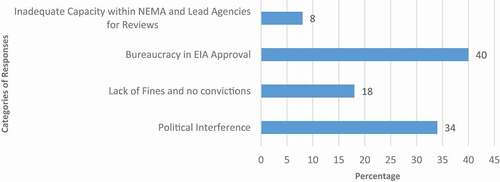

Respondents were asked to nominate reasons why project implementation commenced without ESIA approval. The reasons given were grouped into categories. As illustrated in , 40% of respondents (mostly proponents and EPs) indicated that the ESIA approval process was bureaucratic and took too long (sometimes taking years). Therefore, it was common for proponents to begin their projects while the ESIA process was still underway. Some 34% of respondents mentioned that political pressure was the reason why proponents (especially public sector proponents, i.e. government bodies) started projects before ESIA approval had been given.

Some 18% of respondents (mostly from NEMA and Lead Agencies) indicated that, due to the lack of prosecutions against proponents who started projects without an ESIA, a culture of non-compliance had developed. Proponents commenced projects without approval simply because they knew they could get away with it. Most interviewees indicated that, although NEMA was meant to be a regulator and to review reports, NEMA staff only used the information provided by proponents and did not verify it, for example by doing site inspections. In some cases, false information had been provided by proponents. Given that there was no verification of information, this had resulted in projects being approved, even though they were located in protected areas or in wetlands, which was completely in contravention of the regulations. Given the lack of funding to NEMA and the large number of projects on the go, NEMA staff were often overstretched, which has resulted in delays to approval processes, making ESIA unpopular with developers. This situation has also led to the view that it is acceptable for projects to proceed without approval. Four respondents (mostly EPs) said that inadequate capacity within NEMA and the Lead Agencies was the reason why proponents began projects without having approval, stating that staff from these institutions lacked the resources to conduct field inspections, making it easy for proponents to ignore the requirements.

Some EPs had poor understanding of the legal requirements and procedures around ESIA. Many EPs were still learning about ESIA rather than being skilled, experienced practitioners. This has been noted elsewhere, including in countries with mature ESIA systems (Jha-Thakur and Fischer Citation2016). For ESIA to work effectively, appropriate skills and training are needed for all stakeholders, including staff working for government departments, developers, EPs, NGOs and academics (Jha-Thakur et al. Citation2009).

It could be argued that there is a misunderstanding surrounding ESIA, with some advocates seeing it as a ‘magic wand’ that can be applied to all environmental management problems, even though there may be other, more-appropriate options and/or without realising that ESIA does not always provide a clear answer to inform decision making. Some EPs have not realised that ESIA is simply one of many environmental management tools and that its contribution should be seen as being complementary to other policy instruments, including laws, policies, standards and regulations. With the increase in the number of EPs, and a widespread lack of training in the environmental and social aspects of projects, communication between NEMA and developers has been severely curtailed, and has often been delegated or relegated to EPs, who themselves are often not very aware of the issues, and who generally have a vested interest in getting more consulting work. Due to its lack of resources, typically developers have not been able to access the free advisory services NEMA is supposed to provide. This has meant that developers have paid consultants for advice, including to conduct ESIAs for projects that may not have actually required them. Altogether, this has led to much dissatisfaction with the ESIA process. Furthermore, ESIA has been commercialised and traded for financial gain rather than be implemented effectively to achieve its original intended purpose.

The main issues relating to the operation of the legal system that emerged from the interviews were: the lack of visibility of environmental lawyers; limited access to information; the need for a specific environmental court that has knowledge and experience in dealing with environmental law matters; the lack of training and expertise of the judiciary in terms of environmental law matters; judicial bias in favour of protecting company investments rather than the public interest; bribery and other forms of corruption; dissatisfaction with judicial review (appeal) processes; lack of public awareness of environmental rights or avenues for redress; the general lack of interest by the public in environmental law matters; the difficulties community groups have in finding the funding needed to take legal action and a fear of having to pay court costs and perhaps the costs of the defending party should they lose a legal challenge; and a general lack of public support for community groups in Uganda. Overall, the inadequacy of the legal system limited the effectiveness of the ESIA system (Twinomugisha Citation2007; George et al. Citation2020). Clearly, there needs to be capacity building of the judiciary, especially in relation to environmental matters.

4.3. Components of the ESIA process

4.3.1 Screening

In international ESIA understanding, the relevant environment agency would be expected to maintain a record of screening decisions for all projects. Despite the regulations and guidelines (see ), in Uganda there was no established practice of NEMA maintaining a record of screening decisions. One respondent stated that developers did not undertake a rigorous screening process and there was no procedure for screening decisions being submitted or recorded anywhere. We have no evidence of NEMA having issued any certificate of exemption from EIA based on a submitted screening report.

To avoid having to undertake a full ESIA process, proponents often understated the likely impacts or size of their project. Conversely, especially when there was donor funding for an ESIA, the opposite sometimes happened, with EPs exaggerating issues to ensure that an ESIA would be triggered – thus generating extra work for themselves. Most respondents indicated that, generally, only projects implemented with donor oversight had adequate screening.

Neither the National Environment Act nor the EIA Regulations contained a screening checklist with clear advice about whether or not an ESIA was required. Instead, the National Environment Act states that a screening checklist should be provided by the lead agencies in consultation with NEMA, but this has not yet been done. In current practice, EPs in consultation with the proponent make their own determinations about screening, without any formal review of these screening decisions by NEMA or other entity. Some interviewees indicated that, in the National Environment Act (2019), some specified thresholds that are meant to trigger ESIAs were inappropriate. Furthermore, when no thresholds were set for particular issues, screening decisions were likely to result in no ESIA being triggered.

4.3.2. Scoping

Scoping is the process of identifying the key environmental and social issues to be analysed in the ESIA. It is an important step, as indicated by 94% of respondents. However, some interviewees indicated that scoping was sometimes manipulated towards the interests of the proponent. Most respondents indicated that there should be more specific guidelines about how scoping is done and written up. With the ESIA guidelines (NEMA Citation1997) not having been up-dated, the scoping stage is underdeveloped in the Ugandan procedures, including that only minimal public participation is expected at this stage. The few proponents who were interviewed were not aware of scoping and did not see any reason why stakeholders should be consulted early in the ESIA process. International best practice clearly states that the lack of participation at this stage limits the issues that will be considered, making ESIA ineffective (Vanclay et al. Citation2015).

4.3.3. Assessment of alternatives

Consideration of alternatives was mentioned in the National Environment Act 2019, but not in the 1995 Act. Although the 2019 Act requires that technical and spatial alternatives be considered, most respondents commented that only one option, the preferred alternative, was usually considered. Respondents were asked about the reasons for not considering alternatives. Eleven respondents stated that ESIA was conducted at a late stage in project planning when most design details have been finalised and there was no opportunity to consider alternatives. Some 82% of respondents indicated that, even if projects had alternatives, selection of the preferred option was based purely on economic considerations. EPs indicated that they simply accepted the option nominated by the engineering team, rarely questioning the project specifications. Many respondents mentioned that political considerations predetermined the location of most projects and that no alternatives were considered.

4.3.4. Public participation

Several respondents considered that public participation activities were done only for the purpose of generating attendance records, and that the views of consulted stakeholders were usually disregarded. Some 72% of respondents indicated that the stakeholders invited to participate in ESIA processes were selected because of their support for the proposed project and their relationship with the proponent rather than being representative of the affected people. Although Regulation 22 of the EIA Regulations (NEMA Citation2020) indicates that NEMA may hold a public hearing, very few projects have ever had public hearings, as stated by 92% of respondents. Some interviewees indicated that the culture of top-down decision-making in Uganda limited the effective inclusion of public participation in ESIA process. However, some interviewees stated that public participation was carried out for projects in which people were being resettled.

The lack of public participation is a weak aspect of Uganda’s ESIA system. Despite the importance of public participation to ESIA (Glucker et al. Citation2013), there is limited information that applies to a developing country context. The public participation provisions in ESIA legislation are influenced by each country’s culture of decision making, and public participation tends to be less valued in countries where the political culture is less democratic (Purnama Citation2003). In many developing countries, top-down governance tends to limit the extent of public participation in ESIA (Dienel et al. Citation2017). However, if local community expectations are not met, this could lead to grievances and opposition against the project partners (Hanna et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, freedom of information is a fundamental human right (Dokeniya Citation2014; van der Ploeg and Vanclay Citation2017) and increasing access to environmental information furthers sustainable development, democracy, a healthy environment, and good governance (ECLAC Citation2018). For projects to truly get a social licence to operate, communities need to have more autonomy and decision-making power, including the ability to determine their own future (Hanna and Vanclay Citation2013).

4.3.5. ESIA follow-up

An effective ESIA system has proper implementation of mitigation measures and monitoring procedures (Marshall et al. Citation2005; Momtaz and Kabir Citation2013). However, 96% of respondents stated that mitigation measures were not being implemented by most projects. This was attributed to proponents simply wanting to obtain a Certificate of Approval from NEMA, rather than any real commitment to environmental management. The certificates assist proponents in accessing funding from financial institutions and donors, which is a strong driver for ESIAs to be done. However, monitoring and follow-up procedures were absent. All respondents confirmed this and claimed that the lack of fines and inspection meant that developers refrained from conducting monitoring. The lack of follow-up inspections by NEMA was due to their limited capacity and resources.

There is a need to evaluate whether the implementation of projects fulfils the predictions and recommendations made in ESIAs. However, a challenge remains in encouraging developers to use the ESIA reports to inform the implementation of their projects. Unfortunately, it often was the case that during project implementation some developers (or their project managers) did not even know the location of the ESIA report for their project, let alone make any reference to any of its contents or recommendations. Under such circumstances, ESIA obviously does not influence the project. This situation is further complicated when developers exploit the weak enforcement capacity to ignore some recommendations. These findings indicate that ESIA practice in Uganda is largely preoccupied with the preparation of ESIA reports, despite the fact that the ultimate effectiveness of an ESIA system depends on the effective implementation of mitigation measures and follow-up (Marshall et al. Citation2005; Gachechiladze-Bozhesku and Fischer Citation2012; Momtaz and Kabir Citation2013).

4.4. Role of NEMA in facilitating project implementation

In consultation with lead agencies, NEMA is responsible for managing the review of ESIA reports, deciding on the acceptability of ESIA reports, and issuing ESIA Approval Certificates. Our research suggests that, even with the establishment of four NEMA regional offices across Uganda in 2018, the ESIA approval process is still centralised. In 2004, NEMA had only 4 staff, as at 2021 NEMA had approximately 28 staff at the national level, and 2 to 3 staff at each of the 4 regional offices. The various lead agencies each have environment experts who have responsibility for reviewing ESIA reports and conducting site inspections. Most respondents (92%) indicated that, given the increasing number of proposals being considered, NEMA and the lead agencies were still understaffed. Furthermore, some interviewees indicated that many staff in NEMA and the lead agencies were not sufficiently qualified, and 68% of respondents highlighted the need for more training. Other weakness mentioned included: delays in review processes; a lack of resources to conduct site visits; and corruption and bribery. The interviews suggested that the ESIA process was not properly positioned within the project implementation cycle, since most proponents conduct ESIA only after they have concluded the design stage, and consequently ESIA does not inform project design. Furthermore, the ESIA process was not in harmony with other project licensing requirements, and often the ESIA process ends up delaying project implementation, although this is partly related to the fact that proponents left undertaking ESIA to a late stage.

Delays to approvals by NEMA and the Lead Agencies were perceived to affect project implementation, especially in situations where the Approval Certificate was needed to access finance. The law does not set timelines for the approval process, although timelines are mentioned in the ESIA guidelines, which are not legally binding. Some proponents deceptively use ESIA as a mechanism to obtain formal approval for their projects that violate other regulations, for example for projects that are located in wetlands or in buffer zones of protected areas. This subterfuge can only occur with the complicity of EPs and a lack of review of ESIAs. Unfortunately, this misuse of ESIA potentially creates doubt about the integrity of the ESIA system amongst the public.

4.5. Influence of politicians and influential persons

As has been observed elsewhere (Bragagnolo et al. Citation2017; Fonseca and Rodrigues Citation2017; Williams and Dupuy Citation2017; Enríquez-de-salamanca Citation2018), ESIA has been under attack, and is prone to corruption and the undue influence of influential persons. In Uganda, there was concern by some interviewees that the good intentions of ESIA were being thwarted by poor implementation, corruption, and interference in the process. It was thought that some politicians and other key identities considered ESIA to be time consuming, bureaucratic, and a barrier to development. A few interviewees indicated that some people in various sections of government wanted to streamline the project approval process by removing the requirement for ESIA, or at least to make ESIA a simpler, faster and cheaper process. We believe that such change is motivated by dubious motives, and would be inappropriate in the absence of full understanding of the purpose of ESIA and a proper assessment of its effectiveness and reasons for inefficiency.

For various reasons, NEMA has had limited ability in controlling politically-influential proponents. NEMA is only partially independent in that the President directly appoints the Director of NEMA. The circuits of power and influence within Uganda mean that NEMA has been hampered in its ability to regulate projects. While this situation is common to all developing countries, these weaknesses in institutional arrangements also exist in advanced economies (Paliwal and Srivastava Citation2012). A major reason for this weakness is that most politicians and developers have not appreciated the value of ESIA as a planning tool for them. Developers tend to only fulfil legal requirements rather than see ESIA as effectively contributing to their project planning and operation. ESIA is often done by developers only at the last minute in order to meet legal requirements or other demands, such as in order to secure loans. Consequently, there is persistent separation of ESIA from the project planning and implementation processes. Until ESIA can demonstrate value to all stakeholders and is properly implemented and regulated, with effective compliance monitoring, there will always be temptations on developers to shortcut the process.

5. Overall evaluation of the ESIA system in Uganda

The ESIA system in Uganda is still developing and suffers from the deficiencies that are common across developing countries everywhere. summarizes our assessment regarding the performance of the ESIA system in Uganda. ‘Fully achieved’ was assigned when there was evidence to conclude that the criterion had been met. ‘Partially achieved’ was given when there was some support, but some inadequacies. ‘Not achieved’ was given when there was clear evidence that the criterion has not been met.

Table 2. Performance of ESIA practice in Uganda

6. Conclusion and recommendations

ESIA practice in Uganda is still developing and many issues restrict its effectiveness. The changes to the ESIA system in the last few years (for example updating the National Environment Act and EIA Regulations) are improvements and the National Environment Management Authority is now well mandated by law to oversee ESIA. Despite this progress, regulatory oversight of ESIA practice in Uganda is far from being good practice, particularly with respect to the legislation is not being observed by all actors, and NEMA not being properly funded and having a shortage of qualified staff. Furthermore, the system is ineffective, with proponents complaining about delays, and many proponents (public sector and private sector) finding ways to bypass the requirement to do ESIA. In general, ESIA processes are deficient in terms of: the quality of information and decisions made in the screening step; the adequacy of public participation throughout the process; and lack of consideration of alternatives in the ESIA. Although the Ugandan ESIA system allows for public participation, ensuring that it is done genuinely and effectively, and encouraging the public to meaningfully contribute, are problematic. The limited extent and forms of participation, and the late stage of participation activities when they are undertaken, means that the public’s views are not being considered in the design of projects. Another major problem is the lack of post ESIA follow-up, and therefore considerable doubt about whether proposed mitigation measures and any regulatory approval conditions are being effectively implemented.

Given all the inadequacies of the ESIA system in Uganda, the following recommendations can be made. It is likely that many of these recommendations will apply to other countries, especially to those in a developing country context.

6.1. Resourcing

The funding to the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) needs to be increased so that it can become equipped with adequately trained staff and have an adequate budget to perform its functions.

Adequate training of NEMA staff must be provided so that they are competent to do the expected tasks.

6.2. Policy and legal framework

There is need for NEMA to improve its policies and procedures, particularly around ESIA follow-up.

To provide effective review of the adequacy of submitted ESIAs, a truly independent body needs to be established.

There is a need for NEMA to revise the EIA Regulations to strengthen the penalties applicable to proponents who commence project implementation before ESIA approval has been given – and to actually prosecute such offenders. There is need to determine appropriate penalties that will deter misconduct.

Consider making ESIA approval certificates temporary (or at least subject to annual renewal), with renewal of approval contingent upon satisfactory annual environmental audits.

6.3. Operational aspects

To achieve effective, substantive contribution from public participation during ESIA processes, public participation needs to be improved throughout the entire project cycle. Efforts should be made to increase the public’s access to information, including by: promoting the use of digital platforms; removing restrictions on access to ESIA documents; publishing details of new projects and ESIA processes on NEMA’s website; and by developing formal guidelines for the conduct of public participation.

Effective inspections of project sites must be regularly conducted by NEMA and/or appropriate Lead Agencies to ensure the accuracy of the information in ESIAs prior to project approval, and to ensure compliance by proponents of ESIA regulations and permit conditions.

There should be capacity building of the judiciary to enhance their ability to handle environmental law cases. If the volume of cases demands it, it may be necessary to establish environmental courts at the regional level.

6.4. The broader context

There should be increased political commitment to environmental protection and a greater appreciation of the interdependence of environment, economy and society.

There is need to build the capacity of civil society organizations, especially their access to scientific capacity and collaborations with universities and research institutions. This will enhance their capacity to provide independent scientific information for evidence-based debate and to contribute to decision-making during public hearings or other avenues for public participation. There should be an explicit legal basis to promote and support the effective role of CSOs in ESIA processes.

International development agencies and international financial institutions each have their own ESIA standards, which often mean that hybrid ESIAs are needed to meet the varying requirements. It would be highly desirable if there would be greater harmonisation of these requirements, or if the multiple partners in a project could agree on which standards to apply with respect to a specific project.

A problem with international agencies is that there is a strong oversight up to project approval stage, but there is a lack of compliance checking post-funding. Implementing a process of compliance monitoring would force proponents to properly implement promised mitigation measures and any conditions of approval. This is especially important for public sector projects because it is very difficult for national environment agencies to prosecute government proponents.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the environmental practitioners, academics, and staff from government agencies, developers, and civil society organizations for responding to the on-line survey and participating in the in-depth interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmadvand M, Karami E, Zamani G, Vanclay F. 2009. Evaluating the use of social impact assessment in the context of agricultural development projects in Iran. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(6):399–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2009.03.002.

- Arts J, Runhaar H, Fischer T, Jha-Thakur U, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14(4):1250025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333212500251.

- Aung T. 2017. Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system and implementation in Myanmar: its significance in oil and gas industry. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 66:24–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.05.005.

- Bragagnolo C, Carvalho Lemos C, Ladle R, Pellin A. 2017. Streamlining or sidestepping? Political pressure to revise environmental licensing and EIA in Brazil. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 65:86–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.04.010.

- Cashmore M, Gwilliam R, Morgan R, Cobb D, Bond A. 2004. The interminable issue of effectiveness: substantive purposes, outcomes and research challenges in the advancement of environmental impact assessment theory. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 22(4):295–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/147154604781765860.

- Cashmore M, Richardson T, Hilding-Ryedvik T, Emmelin L. 2010. Evaluating the effectiveness of impact assessment instruments: theorising the nature and implications of their political constitution. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30(6):371–379. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2010.01.004.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.05.006.

- Chanchitpricha C, Bond A. 2020. Evolution or revolution? Reflecting on IA effectiveness in Thailand. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(2):156–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1664821.

- Dendena B, Corsi S. 2015. The environmental and social impact assessment: a further step towards an integrated assessment process. J Clean Prod. 108(Part A):965–977. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.110.

- Dienel H, Shirazi L, Schroder M, Schmithals J, editor. 2017. Citizens’ participation in urban planning and development in Iran. New York: Routledge.

- Dokeniya A. 2014. The right to information as tool for community empowerment. World Bank Legal Rev. 5:599–614.

- Dominik R, Willibald L, Seleshi A, Eline B. 2010. Evaluation of the environmental policy and impact assessment process in Ethiopia. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 28(1):29–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155110X488844.

- Ecaat J. 2004. A review of the application of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Uganda: a report prepared for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Kampala: National Environment Management Authority. [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://www.nape.or.ug/publications/reports/35-report-eia-uganda/file.

- ECLAC. 2018. Access to information, participation and justice in environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean: towards achievement of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (LC/TS.2017/83). Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/43302/1/S1701020_en.pdf.

- Enríquez-de-salamanca A. 2018. Stakeholders’ manipulation of environmental impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:10–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.10.003.

- Esteves AM, Franks D, Vanclay F. 2012. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):34–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.660356.

- Fonseca A, Rodrigues S. 2017. The attractive concept of simplicity in environmental impact assessment: perceptions of outcomes in south eastern Brazil. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 67:101–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.09.001.

- Gachechiladze-Bozhesku M, Fischer T. 2012. Benefits of and barriers to SEA follow-up. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 32(4):22–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2011.11.006.

- George T, Karatu K, Andama Edward A. 2020. An evaluation of the environmental impact assessment practice in Uganda: challenges and opportunities for achieving sustainable development. Heliyon. 6(9):E04758. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04758.

- Glucker A, Driessen P, Kolhoff A, Runhaar H. 2013. Public participation in environmental impact assessment: why, who and how? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:104–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.06.003.

- Hanna P, Vanclay F. 2013. Human rights, Indigenous peoples and the concept of free, prior and informed consent. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 31(2):146–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.780373.

- Hanna P, Vanclay F, Langdon EJ, Arts J. 2014. Improving the effectiveness of impact assessment pertaining to Indigenous peoples in the Brazilian environmental licensing procedure. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 46:58–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.01.005.

- Hanna P, Vanclay F, Langdon EJ, Arts J. 2016. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest action to large projects. Extr Ind Soc. 3(1):217–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2015.10.006.

- Ijabadeniyi A, Vanclay F. 2020. Socially-tolerated practices in environmental and social impact assessment reporting: discourses, displacement, and impoverishment. Land. 9(2):33. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land9020033.

- Jha-Thakur U, Fischer TB. 2016. 25 years of the UK EIA system: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 61:19–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2016.06.005.

- Jha-Thakur U, Gazzola P, Peel D, Fischer T, Kidd S. 2009. Effectiveness of strategic environmental assessment: the significance of learning. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 27(2):133–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155109X454302.

- Joseph C, Gunton T, Rutherford M. 2015. Good practices for environmental assessment. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 33(4):238–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2015.1063811.

- Kahangirwe P. 2011. Evaluation of environmental impact assessment practice in Western Uganda. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 29(1):79–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155111X12913679730719.

- Kahangirwe P. 2012. Linking environmental assessment and rapid urbanization in Kampala City. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(2):111–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.660353.

- Kamijo T, Huang G. 2016. Improving the quality of environmental impacts assessment reports: effectiveness of alternatives analysis and public involvement in JICA supported projects. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 34(2):143–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2016.1176402.

- Khosravi F, Jha-Thakur U, Fischer T. 2019. Evaluation of the environmental impact assessment system in Iran. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 74:63–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2018.10.005.

- Kolhoff A, Runhaar H, Driessen P. 2009. The contribution of capacities and context to EIA system performance and effectiveness in developing countries: towards a better understanding. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 27(4):271–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155109X479459.

- Loomis J, Dziedzic M. 2018. Evaluating EIA systems’ effectiveness: a state of the art. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 68:29–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.10.005.

- Marshall R, Arts J, Morrison-Saunders A. 2005. International principles for best practice EIA follow-up. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 23(3):175–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/147154605781765490.

- Momtaz S, Kabir S. 2013. Evaluating environmental and social impact assessment in developing countries. Waltham: Elsevier.

- Morgan R. 2012. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 30(1):5–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2012.661557.

- Nadeem O, Hameed R. 2008. Evaluation of environmental impact assessment system in Pakistan. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 28(8):562–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2008.02.003.

- NEMA. 1997. Guidelines for environmental impact assessment in Uganda. Kampala (Uganda):National Environment Management Authority.

- NEMA. 1998. The environmental impact assessment regulation, S.I. no. 13/1998. Entebbe (Uganda): National Environment Management Authority. [accessed 2021 May 30]. http://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/eia_egulations.pdf.

- NEMA. 2020. National environment (Environmental and social assessment) regulations, 2020. Kampala (Uganda): National Environment Management Authority. [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/National%20Environment%20(Environmental%20and%20Social%20Assessment)%20Regulations%20S.I.%20No.%20143%20of%202020.pdf.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F. 2021a. Cut-off and forgotten: livelihood disruption, social impacts and food insecurity arising from the East African crude oil pipeline. Energy Res Social Sci. 74:101970. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.101970.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F. 2021b. Resource financed infrastructure: thoughts on four Chinese-financed projects in Uganda. Sustainability. 13(6):3259. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063259.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F, van den Assem A. 2018. Impacts of the oil boom on the lives of people living in the Albertine Graben region of Uganda. Extr Ind Soc. 5(1):98–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2017.12.015.

- Ogwang T, Vanclay F, van den Assem A. 2019. Rent-seeking practices, local resource curse, and social conflict in Uganda’s emerging oil economy. Land. 8(4):53. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land8040053.

- Ortolano L, Shepherd A. 1995. Environmental impact assessment: challenges and opportunities. Impact Assess. 13(1):3–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07349165.1995.9726076.

- Paliwal R, Srivastava L. 2012. Adequacy of the follow-up process in India and barriers to its effective implementation. J Environ Plann Manage. 55(2):191–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2011.588063.

- Purnama D. 2003. Reform of the EIA process in Indonesia: improving the role of public involvement. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(4):415–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-9255(03)00046-5.

- Sadler B. 1996. Environmental assessment in a changing world: evaluating practice to improve performance. international study of the effectiveness of environmental assessment: final report. Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency and the International Association for Impact Assessment. [accessed 2021 May 30] https://unece.org/DAM/env/eia/documents/StudyEffectivenessEA.pdf.

- Suwanteep K, Murayama T, Nishikizawa S. 2016. Environmental impact assessment system in Thailand and its comparison with those in China and Japan. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 58:12–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2016.02.001.

- Therivel R, Wood G, editors. 2018. Methods of environmental and social impact assessment. 4th ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Twinomugisha B. 2007. Some reflections on judicial protection of the right to a clean and healthy environment in Uganda. Law. Environ Dev J. 3(3):244–258.

- Uganda. 1995. The National Environmental Act, cap 153. [accessed 2021 May 30]. http://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/national_environment_act.pdf.

- Uganda. 2019. The National Environment Act, 2019. [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://nema.go.ug/sites/all/themes/nema/docs/National%20Environment%20Act,%20No.%205%20of%202019.pdf.

- van der Ploeg L, Vanclay F. 2017. A tool for improving the management of social and human rights risks at project sites: the human rights sphere. J Clean Prod. 142(Part 4):4072–4084. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.028.

- Vanclay F. 2015. Changes in the impact assessment family 2003–2014: implications for considering achievements, gaps and future directions. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 17(1):1550003. doi:https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333215500039.

- Vanclay F. 2020. Reflections on social impact assessment in the 21st century. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(2):126–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1685807.

- Vanclay F, Baines J, Taylor CN. 2013. Principles for ethical research involving humans: ethical professional practice in impact assessment part I. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 31(4):243–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.850307.

- Vanclay F, Esteves AM, Aucamp I, Franks D. 2015. Social impact assessment: guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects. Fargo (ND): International Association for Impact Assessment. [accessed 2021 May 30]. https://www.iaia.org/uploads/pdf/SIA_Guidance_Document_IAIA.pdf.

- Vanclay F, Hanna P. 2019. Conceptualising company response to community protest: principles to achieve a social license to operate. Land. 8(6):101. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land8060101.

- Williams A, Dupuy K. 2017. Deciding over nature: corruption and environmental impact assessments. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 65:118–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.05.002.

- Wood C. 2003. Environmental impact assessment: a comparative review. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Prentice Hall.