ABSTRACT

We explore whether local planning culture influences the effectiveness of heritage impact assessment (HIA) and we discuss the legitimacy of ICOMOS, the international advisory body to UNESCO on cultural heritage. We examined the HIA processes for two proposed infrastructure projects that potentially could affect the Defence Line of Amsterdam World Heritage site in the Netherlands. We interviewed key stakeholders involved in decision-making about these projects, and found that the Dutch planning culture positively influenced the effectiveness of the HIA processes. The interviewees predominantly discussed the substantive and transactive effectiveness of the HIA processes in that they praised the practitioner for facilitating a clear, inclusive and transparent process and having a solution-oriented mindset, which is common practice in the Dutch planning culture. However, in contrast to the Dutch planning culture, the role of ICOMOS was perceived as opaque and a ‘black box’, although this did not decrease its legitimacy among the key stakeholders.

1 Introduction

The way cultural World Heritage sites are managed and the legitimacy of ICOMOS (the advisory body to UNESCO on cultural heritage matters) have been criticized over the last decades (Affolder Citation2007; Patiwael et al. Citation2019, Citation2020). This criticism has become especially apparent in controversies about the acceptability of spatial developments in World Heritage sites that threaten the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of these sites, for example: (1) the construction of a bridge in the Dresden Elbe Valley (Gaillard and Rodwell Citation2015); (2) a proposed expressway near Stonehenge (Fielden Citation2019); and (3) a redevelopment scheme partially located in the Maritime Mercantile City of Liverpool (Patiwael et al. Citation2020).

ICOMOS (Citation2011) introduced its Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) framework as a tool to assist in managing World Heritage sites. National governments are now required to conduct an HIA for each proposed spatial development project that potentially could negatively affect the OUV of a World Heritage site. After completion of an HIA, ICOMOS reviews the report and management plans for the World Heritage site, making it the international competent authority in the context of HIA.

The purpose of this paper is to explore whether the local planning culture can influence the effectiveness of an HIA process, and we also discuss the legitimacy of ICOMOS. We analysed two proposed infrastructure projects – the construction of a link road, and the construction of a train depot – that were planned within the ‘Defence Line of Amsterdam’ (Stelling van Amsterdam), a World Heritage area in the Netherlands since 1996 (UNESCO Citation2021). Independent HIAs were conducted for these projects by Land-id, a small Netherlands-based consulting firm (Land-id Citation2015a, Citation2015b). These HIAs were considered by ICOMOS (Citation2015) to be examples of good practice, although the decision-making about these projects was lengthy and complex. We analysed the decision-making processes and interviewed the key institutional stakeholders.

2 Understanding effectiveness, legitimacy and planning culture

2.1 Effectiveness

In general, effectiveness is the extent of success in achieving specified goals. In considering the effectiveness of impact assessments, many things are intertwined, including the purpose; the process used; the adequacy of resources (e.g. time, cost); the various stakeholders and their varying expectations; the values of the decision makers; and the extent of learning from the process (Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013). The effectiveness of impact assessment is highly subjective (Cashmore et al. Citation2008), context dependent (O’Faircheallaigh Citation2009; Arts et al. Citation2012), and multidimensional (Rozema and Bond Citation2015).

Effectiveness is generally considered to have four dimensions: (1) procedural, which refers to compliance with applicable institutional procedures and legislation; (2) substantive, which refers to the degree to which an impact assessment mitigates negative impacts, enhances outcomes, and influences decision-making; (3) transactive, which refers to level of satisfaction with the expertise of the people involved and time/cost efficiency; and (4) normative, which refers to the degree to which there are outcomes that go beyond the immediate scope of the present HIA and project (Baker and McLelland Citation2003; Chanchitpricha and Bond Citation2013; Rozema and Bond Citation2015; Pope et al. Citation2018).

These four dimensions are reflected in empirical research about HIA. For example, Kloos (Citation2017) argued that HIA was most effective when: (1) it was commissioned and conducted early in the decision-making process; (2) it was used as a solution-oriented tool rather than as a preventive tool; and (3) it was conducted in a participatory way. Patiwael et al. (Citation2020) stressed the importance of transparency and participation of local stakeholders. Ashrafi et al. (Citation2021) argued that effectiveness is influenced by (1) methodology; (2) applicable legislation; (3) the extent of multi-sectoral collaboration; and (4) the adequacy of communication and capacity-building. They also stressed the importance of conducting an HIA early in the planning process.

2.2 Legitimacy

Legitimacy is generally defined as the extent to which something is fair, reasonable and acceptable (Jijelava and Vanclay Citation2017). In the context of government decision-making, Bodansky (Citation1999, p.601) defined legitimacy as ‘the justification of authority’, which has sociological (i.e. popular attitudes about authority) and normative (i.e. a claim of authority being justified in some objective sense) dimensions.

The legitimacy of international organizations such as ICOMOS can also be considered in terms of: (1) input legitimacy (i.e. the quality of the inputs into their decision-making processes, including the extent of participation); (2) throughput legitimacy (i.e. the quality of the actual decision-making processes); and (3) output legitimacy (i.e. the extent to which the decisions are considered legitimate or acceptable by the stakeholders and, for example, contribute to solving problems) (Schmidt Citation2013; Strebel et al. Citation2019; Patiwael et al. Citation2020). However, the internal governance processes of international organizations are often seen as being ‘black boxes’, which is why throughput legitimacy focuses on accountability, efficacy, inclusiveness, openness and transparency (Schmidt Citation2013).

Empirical research about the success of participatory initiatives in increasing throughput legitimacy suggests that the introduction of participatory mechanisms has been problematic. For example, Doberstein and Millar (Citation2014) found that throughput legitimacy can positively affect the input and output legitimacy of institutions, but when compromised their legitimacy is negatively affected. Iusmen and Boswell (Citation2017) argue that participatory mechanisms are not a quick fix and often require parallel strategies to improve the perceived legitimacy of organizations.

2.3 Planning culture

Given their context dependency, we argue that the effectiveness of an HIA process and the legitimacy of ICOMOS are influenced by the local spatial planning culture. Spatial planning is influenced by cultural factors (Sanyal Citation2005; Othengrafen Citation2010; de Vries Citation2015; Valler and Phelps Citation2018). This results in different approaches to spatial planning across locations, due to the differences in practices, knowledge, beliefs, norms and values among spatial planning professionals (Othengrafen Citation2010). Local culture affects the organizational structure of spatial planning, resulting in different styles of project management (Hurn Citation2007; Ochieng and Price Citation2009; de Bony Citation2010). This creates different approaches to communication (Ochieng and Price Citation2009), negotiation (Hurn Citation2007), and leadership (de Bony Citation2010).

In response to these differences, the concept of ‘planning culture’ has emerged, and is defined by Sanyal (Citation2005, p.xxi) as ‘the collective ethos and dominant attitudes of planners regarding the appropriate role of the state, market forces and civil society in influencing social outcomes’. In other words, planning culture is the paradigm or worldview of the planning profession in a particular place, and it influences cognitive frames, planning practice, and planning outcomes (Taylor Citation2013; Stead et al. Citation2015; Valler and Phelps Citation2018). Defining planning culture in terms of ‘cognitive framing’ suggests that its role may be somewhat hidden or subdued, but nevertheless is still influential for effectiveness and the extent to which an HIA report and its handling by ICOMOS are regarded as legitimate.

3 The planning culture of the Dutch planning profession

Dutch decision-making culture is arguably characterized by cooperation, consultation and consensus building (Visser and Hemerijck Citation1997; de Bony Citation2010; Breukel Citation2018). Decisions are typically not made in a hierarchical system that must be followed, rather they are negotiated towards a consensus that all key institutional stakeholders agree on. Dutch decision-making tends to be a process of negotiating solutions rather than only deciding from a set of predetermined options. This style of working towards consensus assumes the equal standing of all persons in the process (van Lente Citation1997) and their in-principle right to disagree (de Bony Citation2010). A characteristic of the Dutch decision-making culture is the frequent informal contact between participants (Gerrits et al. Citation2012). While this may sound inclusive, in practice it has often resulted in lengthy negotiation processes centred around formal procedures and meetings. It also has the tendency to result in outcomes accepted by the key stakeholders involved in the process, but, due to the compromises made to achieve consensus, might be unacceptable to people who were not included.

The Dutch decision-making culture is evident in the Dutch planning culture, which is often regarded as mature and exemplary (Faludi and van de Valk Citation1994; Buitelaar and Bregman Citation2016). The planning culture has been participatory with the public being invited to comment on spatial plans throughout the decision-making process (Driessen et al. Citation2001; Woltjer Citation2002). Known as ‘inspraak’, this form of community involvement is embedded in spatial planning legislation in the Netherlands (Arts et al. Citation2016).

Around 2000, the Dutch planning culture shifted towards a more area-oriented development approach in which local stakeholders gained more importance, and the key concepts at the time (e.g. participation, social inclusion, transparency, openness) were incorporated into the decision-making process (Hajer and Zonneveld Citation2000; Louw et al. Citation2003; van Straalen et al. Citation2016). With the 2012 introduction of the Vision on Infrastructure and Spatial Development (Structuurvisie Infrastructuur en Ruimte), decentralization was combined with deregulation (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Ruimte Citation2012), and Dutch planning culture began to focus on trust and shared responsibility (Warsen et al. Citation2019). Stimulating economic development gained importance in Dutch national spatial planning, while other national interests (e.g. spatial quality) seemed to have lost importance (Zonneveld and Evers Citation2014).

Requiring impact assessments has been common practice in Dutch spatial planning (Runhaar et al. Citation2013) and heritage protection has traditionally been integrated in the EIA framework. Dutch EIA practice was considered as being extensive and advanced, because it had a strong legal foundation, went beyond the standards set by the EU, and had a specific focus on the development and assessment of alternatives to the proposed project (Arts et al. Citation2012). Arts et al. (Citation2012) researched what Dutch EIA practitioners considered most important in EIA effectiveness and found an emphasis on four contextual elements that stood out from other nations: (1) legal requirements; (2) quality of EIA; (3) transparency; and (4) environmental attitudes of proponents and competent authorities. Openness and stakeholder participation were also seen as important. We argue that these contextual elements reflect the general characteristics of Dutch planning culture. Similar to Dutch planning culture, Dutch EIA practice underwent a shift in 2010 to increase its time and cost efficiency by simplifying regulations and reducing safeguards. Participatory mechanisms became more flexible and more power was given to competent authorities, but this resulted in an overall decrease in Dutch EIA quality (Arts et al. Citation2012). For example, while consultation is an accepted and valued part of the Dutch impact assessment process (Runhaar et al. Citation2013), there have been examples of infrastructure projects where the impact assessment process and local stakeholder involvement did not meet international standards (Mottee et al. Citation2020).

Dutch decision-making culture and the planning culture influence the way heritage is managed in the Netherlands. At present, the protection of World Heritage sites is regulated by the Heritage Act (Erfgoedwet) of 2016 and by the Spatial Planning Act (Wet Ruimtelijke Ordening) of 2006. Three parties are involved in the management of Dutch cultural World Heritage sites: (1) the site holder (i.e. the management entity for a particular site); (2) the national government, especially through the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, OCW); and (3) the Cultural Heritage Agency (Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed, RCE), an executive body of OCW. The site holder is the individual owner, organization or government body directly responsible for safeguarding a particular site; the national government is responsible for the Dutch World Heritage policy in general; and the RCE functions as a ‘focal point’ (i.e. the liaison with UNESCO) and is responsible for the creation and coordination of World Heritage site management plans (RCE Citation2020b). HIA was introduced into the management of Dutch cultural World Heritage sites in 2011, when the ICOMOS guidelines were endorsed. While there is no specific legal requirement to conduct an HIA in Dutch heritage legislation, site holders and the RCE can demand an HIA to be conducted before a proposal would be considered further.

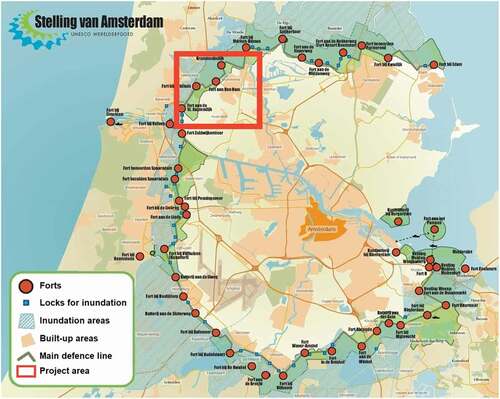

4 Infrastructure projects in the defence line of Amsterdam World Heritage site

The Defence Line of Amsterdam is a circular network of 45 forts along a 135 km perimeter around the city of Amsterdam that was built between 1883 and 1920 (see ). The site was inscribed on the World Heritage register in 1996 for its ‘important place in the development of military engineering worldwide’ and as an example of an ‘extensive integrated European defence system of the modern period’ as well as of ‘the unique way in which the Dutch genius for hydraulic engineering has been incorporated into the defences of the nation’s capital city’ (UNESCO Citation2021, online). The Defence Line was based on the idea that temporarily flooding the land surrounding Amsterdam, making it an Island, would make it easier to defend. By flooding the fields with 50 cm of water, enemy foot soldiers would be slowed down, while it would still be too shallow for boats to cross (van Rotterdam Citation2015). The site consists of the interconnected ring of fortifications together with the open areas that were to be flooded (called ‘inundation fields’) (UNESCO Citation2021).

Figure 1. Map of the Defence Line of Amsterdam. Source: Stelling van Amsterdam (Citation2021).

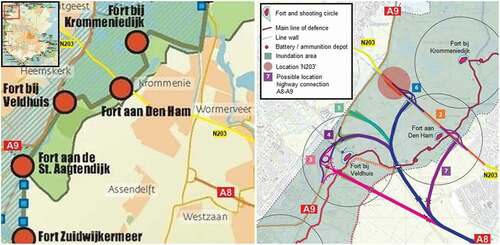

4.1 Case 1: the link road A8-A9

In 2014, the Province of North Holland considered the construction of a link road between the A8 and A9 highways as an option to address the increasing traffic to the north of Amsterdam while improving the liveability of nearby villages (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu Citation2013; Provincie Noord Holland Citation2014). The Netherlands Commission for Environmental Assessment (NCEA) was asked for advice and seven possible locations were identified (see ) after considering technical issues as well as the impact on noise, ecology, air, soil and water quality, traffic flows and ‘special qualities’ (e.g. landscape features and heritage values). Because all seven locations were within the World Heritage site, an analysis of the impacts on the OUV was evidently needed. The consultancy firm, Land-id, was commissioned to conduct the HIA in 2015.

Figure 2. Map of the proposed infrastructure projects in the Defence Line of Amsterdam. Adjusted from (Land-id Citation2015a; Stelling van Amsterdam Citation2021).

The HIA report (Land-id Citation2015a) indicated that the seven options would incur negative impacts on the OUV to various degrees (see ). The report was sent to ICOMOS who preferred Alternative 7, which was mostly located outside of the Defence Line (ICOMOS Citation2015). However, in July 2016, the Provincial Executive of North Holland argued that Alternative 7 would not solve the problems of traffic congestion and health-related issues, and reduced the active options to three: the ‘Zero-Plus Alternative’ (Alternative 2), the ‘Golf Course Alternative’ (Alternative 3) and the ‘Heemskerk Alternative’ (Alternative 5). The Provincial Executive then asked ICOMOS to visit the site to reconsider the remaining options. ICOMOS agreed to this visit and sent a Spanish expert in cultural landscape conservation and management to the area in November 2017. Based on this visit, ICOMOS concluded that ‘at the current time, there is no [remaining] alternative that can be supported’ (ICOMOS Citation2017, p.4). This resulted in a stalemate. At the time of writing (mid 2021), the decision-making process about the link road is still ongoing, but the Provincial Executive has deemed the Golf Course Alternative to be the preferred alternative and is exploring how to realize this with minimal impact on the World Heritage site.

Table 1. Assessment of the impact of the 7 alternatives for the link road on heritage values (based on Land-id Citation2015a)

4.2 Case 2: the train depot near Uitgeest

In anticipation of increased future rail demand in the Province of North Holland, in 2010 the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure developed a plan for high-frequency rail transport between Amsterdam and Alkmaar that would utilize the existing railway network without new tracks being required. To cater for this higher frequency, a train depot would be needed along this section so that several trains could be parked overnight and for maintenance to be conducted. ProRail, the agency responsible for the Dutch national railway infrastructure, was tasked by the Ministry with planning and developing the new rail depot.

ProRail conducted a location study, which included several public participation meetings, resulting in eight options. These locations were then compared for: (1) railway logistics and sustainability; (2) environmental impact; (3) compatibility with existing spatial structure (ruimtelijke inpassing) and cultural heritage; and (4) cost effectiveness (ProRail Citation2014). In January 2015, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment and five municipalities (Beverwijk, Castricum, Heemskerk, Uitgeest and Velsen) decided that the preferred location for the depot would be ‘location N203’ (see ). The Province of North Holland agreed, but only on the condition that the project would not have too many negative impacts on the OUV of the Defence Line of Amsterdam. The parties agreed that an HIA would be conducted by Land-id, the Dutch consultancy firm that was conducting the HIA for the link road.

Three public meetings were organized to enable public input into the HIA process. The HIA report concluded that the train depot would have a moderate negative impact on the OUV, predominantly caused by the reduced integrity of the open landscape (Land-id Citation2015b). Land-id proposed several mitigation measures to decrease this negative impact. The HIA report was sent to ICOMOS for their review in October 2015. Their response was that:

For the train depot, if there is absolutely no other location to construct it out of the WH property, the visual impact must be the least possible, taking into account the very visual aspect of moving stocks at the depot: a depot of short or medium length along the existing line is preferable with the addition of visual fences (dikes, line of trees); this may be negatively qualified as “camouflage” but it seems not possible to carry out the project in [any] other way (ICOMOS Citation2015, p.6).

Considering the decision-making process that led to location N203 being selected, ProRail interpreted the ICOMOS statement as being approval of their plans and started finalizing the project design including the mitigation measures suggested by the HIA and ICOMOS (RCE Citation2020a). However, local resistance to the project increased over time (De Uitgeester Citation2019; Ton Citation2019), and consequently the project stalled. Eventually in January 2019, the Ministry of Infrastructure announced that a train depot was no longer needed at location N203 because a depot would be constructed at a location outside the World Heritage site (ProRail Citation2019). The stated rationale for this change was the high cost of construction at location N203.

5 Methodology

To consider the effectiveness of the HIA processes, we used a qualitative case study approach, which included document analysis, a media analysis of the cases, and semi-structured interviews with the key stakeholders. The two projects were selected because the HIAs for these projects were praised by ICOMOS (Citation2015):

The HIA is undoubtedly well done in technical terms and it offers a good example of the implementation of the ICOMOS recommendations for studying Outstanding Universal Value and integrity-authenticity, with a real effort to propose a large number of possible solutions. … ICOMOS notes with satisfaction the State Party’s efforts to try to design adapted solutions to maintain and to express all the dimensions of the property’s Outstanding Universal Value (ICOMOS Citation2015, p. 3–4).

Although there were separate HIAs, the two projects were intertwined in that they were done by the same consultancy firm (Land-id), were under assessment around the same time (2014–2015), and each HIA considered the possible cumulative impacts of the projects. The latter was also praised by ICOMOS (Citation2015, p.3): ‘Combined impacts [of the link road] with the Train Depot project have also properly been studied and a conclusion providing the degree of effect of the different possibilities appears well established’. Based on these comments, we considered both HIAs as examples of best practice.

In 2017 and 2018, six people who were directly involved in the HIA process of one or both projects were interviewed (see ). The interviewees were identified by contacting the key organizations, which then nominated the specific people who had worked on the projects. We decided against interviewing the HIA practitioner because our research focuses on effectiveness as seen by the key stakeholders.

Table 2. Overview of interviewees

The interviews were conducted face-to-face and all were audio recorded with permission of the interviewees. Informed consent was given by the interviewees prior to the interviews and other aspects of ethical social research were followed (Vanclay et al. Citation2013). An interview guide was used, which included general themes about World Heritage management, followed by specific questions about the HIA process and its role in decision-making. The interviews were conducted and were transcribed in Dutch. For this paper, some selected excerpts were translated from Dutch into English by the authors. This translation was difficult because of the use of some culturally specific statements, but we did our best to find appropriate equivalent English expressions.

A coding scheme was developed (see ) based on the characteristics of Dutch planning culture, the four dimensions of impact assessment effectiveness (procedural, substantive, transactive, and normative), and the three dimensions of legitimacy (input, throughput and output). Effectiveness directly related to the two HIAs that were conducted, and legitimacy referred to ICOMOS. The HIA report and subsequent data gathering by ICOMOS was seen as being input legitimacy, the decision-making process by ICOMOS was seen as being throughput legitimacy, and the official response of ICOMOS was seen as being output legitimacy.

Table 3. Coding scheme

With only six interview transcripts, the coding could be efficiently done using Microsoft Word. The interviews were analysed by grouping the coded quotes for each code. The connections between the coding families were analysed to find links between planning culture and HIA effectiveness and the legitimacy of ICOMOS.

6 Results

6.1 Planning culture

All interviewees expressed a desire to reach consensus in the decision-making processes of the infrastructure projects. In dealing with heritage protection in spatial development, P5 stated that, rather than decisions being imposed: ‘I always think that, yes actually, you need to sit down and talk to find a solution together’. When discussing the application of the ICOMOS HIA framework in the Netherlands, P3 argued that this was perhaps best practice because the starting point was a commitment to achieving consensus, not only in terms of the process to be followed, but also in terms of a commitment to abide by the outcome of the process. P4 described how a desire to reach consensus was implemented in relation to the train depot throughout the whole HIA process:

We just had ample consultations with the key stakeholders. So when we got the final report, it met the expectations … of all stakeholders. That is always important with these kinds of assessments, that you do not happily and naively make a beautiful report that nobody understands or nobody knows where it came from.

Several interviewees referred to the solution-oriented focus in the Dutch planning culture. Some mentioned experiences with other projects involving heritage management. For example, P3 described the planned widening of a canal that would destroy historical military structures (specifically ‘casemates’):

What can you do? Will they disappear? Do you move them a little bit to the side? But then you are falsifying history. Or do you move them, but explain that there have been modifications? [In this case,] the latter option was chosen.

This example shows that, rather than obstructing the project, the RCE was actively involved in finding solutions that would minimize the loss of heritage values while still allowing the project to be realized. Referring to the link road, P3 said: ‘we kept on searching for a solution, which makes this [the HIA process] good practice’. P4 also described this search for solutions in relation to the train depot: ‘The main thing we do is to consider [in kaart brengen] as much as possible to see whether we can turn it into a feasible project’.

Public support in relation to the projects was only discussed by the proponents (and not by the other stakeholders). Both P4 and P6 discussed the ‘not in my backyard’ (NIMBY) phenomenon in relation to their projects. P6 stated that ‘obviously NIMBY played a role in the link road A8-A9’. In both projects, public participation meetings were held before the location of the project was decided. As P4 described:

there was much resistance … Nobody wanted it [the train depot]. So the “not in my backyard” idea … made us get into conversation with the local inhabitants – who asked very critical questions – and [got us into conversation] with the municipality and the Province. … [Because of this communication] in no time, we suddenly had eight possible locations [for the train depot].

All interviewees mentioned the egalitarian nature of Dutch spatial planning. Dealing with different, possibly conflicting, interests is an accepted and normal part of spatial planning in the Netherlands. For example, P4 stated that

it is fine that there is resistance and that there are different interests … that is our daily job. … For every square meter of the Netherlands, there are many different interests, so you always need to provide some sort of mix.

Or, in the words of P3: ‘here you have the essence of spatial planning …: the weighing-up of interests’. P6 added that ‘of course it is up to the authorities to decide what they want to do and how they want to handle the recommendations’.

6.2 HIA effectiveness

The interviewees discussed the procedural effectiveness of the HIA processes predominantly in terms of timeliness. P3 stated that a nation has a duty to report certain spatial planning initiatives to ICOMOS before irreversible decisions are made and argued that:

In general, we [the Netherlands] … report early [in the process]. And then we also try to already conduct an HIA somewhere around this [early] stage. … This applied to the A8-A9 link road, to be very early in the process to steer the entire decision making process.

P6 described the implementation of HIA after the scoping stage in the decision-making process for the link road, which had seven feasible alternatives:

We then funneled-down in two stages. The first funneling … went from seven to three. We are now working on the funneling from three to one. … The HIA played a role in the funneling from seven to three … a significant role.

In contrast, the HIA for the train depot was conducted after the location had been decided. P4 questioned this timing, arguing that it should have been conducted earlier in the process when there still were eight feasible locations: ‘If ICOMOS had just said at that moment “yes, there are eight locations, but one [i.e. the N203 location] is not possible”, then seven locations would have remained [to be considered further]’.

The interviewees discussed the substantive effects of the HIAs, although the decision-making processes for both projects were not yet completed at the time of the interviews. The proponents of each project commented on how the HIA process helped them understand the heritage values and their importance. Initially, P4 was critical about the transparency and clarity of the OUV of the Defence Line of Amsterdam as described by UNESCO, but argued that the HIA had been very effective in creating greater clarity about this. P5 confirmed this by arguing that HIA ‘better articulates the values … at least then you know what you are talking about’. P6 stressed the influence of the HIA in the decision-making process for the link road.

The interviewees only discussed transactive effectiveness of the HIA process in relation to the expertise of the HIA practitioner, whom they unanimously praised for the way: the HIA process was guided, the effective inclusion of all key stakeholders, and for the quality of the HIA report. As stated by P1: ‘I had the feeling that they [Land-id] collated all the interests very well, and that they could listen very well to all parties around the table’. P4 stated that ‘We had very long discussions about some important words and phrasings that were very well guided by Land-id’. P1 emphasized the importance of Land-id as an independent facilitator of these discussions, stating that

obviously some stakeholders preferred to see some items weighted higher than they actually were, but they [Land-id] were very firm in saying “no, this is how we see it and it is our report” … They did not let themselves be controlled by the proponent.

Land-id was also praised by the project proponents for providing clear and tangible explanations of the heritage values of the Defence Line of Amsterdam. For example, P4 stated that Land-id

simply described the integrity and authenticity and the three core values in a very clear way. … [The HIA report] was a clear and readable document containing … criteria that the world of spatial planning and the world of heritage protection understand. It brought those worlds together.

Normative effectiveness played a minor role in the comments of the interviewees. They discussed awareness of the HIA framework in the Netherlands and how these two HIAs set the standard for how it should be implemented. These two case studies raised awareness about the role ICOMOS could play in decision-making processes about spatial development projects that involve World Heritage sites. As described by P6: ‘It [the HIA process] raised awareness. Maybe not the HIA [report] itself, but definitely the advice of ICOMOS that eventually followed it’.

6.3: Legitimacy

The interviewees were generally positive about the input legitimacy of ICOMOS’s decision-making. P1 explained: ‘These [HIA reports] were the first for us. However, I was familiar with the consultancy agency, Land-id, … and I think that they do rigorous work. So I believe they have done very well’. P4 agreed:

Land-id is a good consultancy agency. We had an official advisory group that included the municipality, the province and the ministries. … They put much time and energy into that HIA report resulting in a good final product that was aligned with all parties.

P6 was also positive about the report: ‘I dare say that good research was conducted’.

In the context of throughput legitimacy, several interviewees referred to ICOMOS as being a ‘black box’. For example, P2 argued: ‘It is very opaque. You do not know beforehand what to expect. That makes it very difficult’. P4 stated that the HIA report ‘was mailed to Paris and then we had to wait until something came out of that black box’. And P6: ‘While our process was open and transparent, the process of ICOMOS is closed and a black box. That makes it very difficult to get the gist of it and to actually track down what they mean with their advice’. P4 condemned the limited opportunities to discuss the plans with ICOMOS directly: ‘we had very limited influence in terms of exchanging [ideas]. We requested repeatedly for them [ICOMOS] to drop by or for us to visit them. Can’t we show you our plans? That was impossible’. P4 then expressed doubts about the process: ‘if you just put it into the system [gooi het over de schutting] to ICOMOS without any explanation … then you just have to hope that they will understand everything exactly as we intended’.

A specific aspect of ICOMOS’s process that was seen as especially opaque was the peer reviewing system used after an initial site inspection report is submitted by an expert following a site visit. P1 explained that the expert writes the essence of ICOMOS’s response, but then ICOMOS arranges for two peer reviews of the draft report, which may result in the final advice being somewhat different to what was initially recommended. P6 considered that this procedure was not supported by all proponents: ‘What I find very difficult as a project manager is that those peer reviewers have not visited the location and, therefore, they do not know the finer points of the things to be considered’. P1 acknowledged that ‘for the people who work in spatial planning, ICOMOS is very opaque. … You do not know who you are confronting and there are no legally binding deadlines, but you need to involve them’.

The interviewees seemed mixed in their views on output legitimacy, i.e. the legitimacy of ICOMOS’s advice. For example, in contrast to P6, P1 praised ICOMOS’s procedure, especially the use of peer reviewers: ‘It is not an advice based on one person. It is an advice from ICOMOS’. P2 stated that ‘it was a thorough report’. P4 argued: ‘it helped us in overcoming a hurdle: Is it [the train depot] possible at this location’. P4 also acknowledged that ‘there are obviously boundaries to what can be allowed’, but was critical about ICOMOS’s response:

What is the real benefit of threatening [to delist the site]? Are you thinking with us or thinking against us? Is your only trump card to [threaten to] take away the [World Heritage] status? Or can you also provide something positive about what could be good ways to redevelop [the projects]?

P5 had a similar sentiment: ‘If ICOMOS only says “No, that is not allowed”, then that is not very helpful’. P4 provided an example of contradictory advice by ICOMOS that negatively impacted its output legitimacy:

In the [ICOMOS response], they state that they do not find [the train depot] to be a good idea, but if there is no other option, then we can build the train depot [on the condition that] we camouflage it. That is what the response literally says: “put some trees around it”! That astounded me about the advice. I thought: “trees?, that does not fit … [especially] if you talk about openness [of the landscape]”.

There was also confusion about the ICOMOS advice among the stakeholders of the link road. As explained by P1:

Does the ICOMOS advice mean: look at those two [possible locations] that you have left … and see if you can do something for the OUV with a better or different integration that would make it acceptable. [But] that is not what it literally says. … [However,] we think that this is what ICOMOS means. So that is a question we will ask ICOMOS to clarify.

In the end, as phrased by P6: ‘It is predominantly the advice by ICOMOS that caused dissatisfaction’.

The mixed feelings of the interviewees about the output legitimacy of ICOMOS affected their views about the substantive effectiveness of the HIA report. P4 stated that ‘we did not get a very clear idea about how we could actually implement’ the recommendations. P3 stressed the importance of the HIA assisting in getting heritage protection included in the decision-making process, even though it might be difficult to balance development with heritage protection. P3 suggested that the Province of North Holland potentially reached the point several times at which they might have given up on trying to reach consensus and would just construct the road, but they did not do that: ‘They kept holding to the importance of World Heritage’. Although most interviewees seemed positive about the substantive effect of the HIA process, some were not convinced that it came to a satisfactory result. For example, P6 argued that, although the link road plan was not acceptable to ICOMOS, he thought that the Province will push ahead with it anyway: ‘there is some tension there that cannot be solved by means of an HIA’.

7 Discussion

The interviewees seemed generally positive about the HIA process. The four dimensions of impact assessment effectiveness (procedural, substantive, transactive, and normative) were discussed to various degrees by the interviewees. However, procedural effectiveness was not discussed much by the interviewees. The project proponents did consider the HIA process to be novel, because it was one of the first times HIA has been applied in the Netherlands and the first time each proponent went through an HIA process. Despite this novelty, the requirement of having to conduct an HIA was not an issue. This perhaps can be explained by EIA being common in the Netherlands (Runhaar et al. Citation2013).

The interviewees were mixed in their views about the timing of the HIA procedure in the decision-making process. HIA was considered to be more effective when conducted early in the process, before a final decision about the project siting had been made. While this early timing was the case for the link road, it experienced a more challenging decision-making process – with ICOMOS finding all possible locations unacceptable – than the train depot, in which the HIA process was conducted after the location had been decided.

The substantive effectiveness of the HIA process was acknowledged by all interviewees as there were tangible effects of the HIA on the decision-making for both projects. The HIA directly influenced the location of the link road and directly influenced the design and layout of the train depot. Most interviewees discussed the transactive effectiveness of the HIA process by focusing on the quality of the practitioner. The practitioner was praised for providing clear explanations about the importance of heritage values and how the projects would impact those values. The practitioner was also praised for facilitating a process that provided all key stakeholders with opportunities to express their concerns and viewpoints. This supports the claim by Kloos (Citation2017) and Patiwael et al. (Citation2020) that these aspects of the HIA process are essential to its effectiveness. It also follows the contextual elements found by Arts et al. (Citation2012) that were deemed important among Dutch EIA practitioners for EIA effectiveness. Normative effectiveness about the HIA process was not mentioned much by the interviewees, but they did describe the increased awareness among decision makers in the Netherlands about the role ICOMOS plays in the decision-making about infrastructure projects in World Heritage sites.

Obviously, a Dutch HIA practitioner from a Dutch consultancy agency would be used to working in the Dutch planning culture and would be mindful of the characteristics of this culture in their approach to the HIA process. The interviewees regarded the HIA process as being effective because it was undertaken in a manner consistent with the characteristics of Dutch planning culture: i.e. focusing on consensus and cooperation; being solution-oriented; and giving everyone an equal chance to make comments. While the proponents disagreed with some conclusions in the HIA report, they felt included in the process that reached these conclusions and felt that their viewpoints were sufficiently considered. This resulted in the final HIA report being supported by all key stakeholders.

The interviewees had mixed views on the role ICOMOS played in the decision-making process of both projects as they were positive about ICOMOS’s input legitimacy, negative about ICOMOS’s throughput legitimacy, and mixed about ICOMOS’s output legitimacy. The HIA reports were not questioned, but the interviewees found the decision-making process of ICOMOS opaque and referred to it as a ‘black box’. Lack of direct, face-to-face communication was considered problematic. It seems that the top-down, authoritarian approach used by ICOMOS clashed with the egalitarian nature of the Dutch planning culture. The stakeholders were not used to an organization coming to the conclusion that no options were acceptable without providing ways to negotiate towards an acceptable option. Some interviewees also criticised the official response of ICOMOS for being incongruous in the case of the train depot and for not being solution-oriented and unclear in both cases. Classifying ICOMOS as ‘black box’ is a sentiment found in other HIA processes (Patiwael et al. Citation2020), but unlike these other cases (e.g. Dresden and Liverpool), this did not result in a reduction in the perception of ICOMOS’s authority. The stakeholders kept trying to find a solution with ICOMOS rather than putting ICOMOS’s advice aside and going their own way. This might be explained by the general confidence in the Netherlands in international organizations, and the desire for consensus in Dutch planning culture.

Our research indicates that the HIA process does not function as a quick fix to green-light a project. The Dutch planning culture influenced the effectiveness of the HIAs and the legitimacy of ICOMOS as it created certain expectations (e.g. reaching consensus about how the projects could be realized) among the key stakeholders that were not met. The question remains whether a more transparent and open decision-making process would benefit ICOMOS or whether it would reduce ICOMOS’s authority. ICOMOS strives for the protection of World Heritage sites and, by adhering to an authoritarian decision-making style, it might have a stronger grip on stopping projects that negatively influence heritage values. However, by providing no tangible solutions, ICOMOS could lose its legitimacy among the proponents of spatial development projects and decision makers, which could result in projects being realized regardless of ICOMOS’s judgment and/or potential input into acceptable mitigation measures.

8 Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to explore whether planning culture affects the effectiveness of Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) and the legitimacy of ICOMOS. Our findings suggest that planning culture does influence the effectiveness of the HIA framework. In our Dutch cases, the planning culture positively influenced the HIA process. This highlights the importance of HIA practitioners being familiar with the local planning culture. In the cases we analysed, the HIA practitioner functioned as a facilitator in an open and transparent process, which allowed for cooperation and consensus, and provided mitigation measures with a solution-oriented focus, all of which are elements of the Dutch planning culture. This, in turn, positively influenced the effectiveness of the HIA reports, because all key stakeholders supported the findings of these reports and considered the HIA process to be useful and effective.

Our findings also suggest that local planning culture can negatively influence the legitimacy of ICOMOS if their decision-making style differs markedly from the local planning culture. The authoritarian and opaque decision-making structure of ICOMOS reduced its throughput and, to a lesser degree, output legitimacy among the key stakeholders. The difference in planning culture seemed to increase frustration among the key stakeholders towards ICOMOS, but did not seem to jeopardize the legitimacy of ICOMOS overall.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Affolder N. 2007. Mining and the World Heritage convention: democratic legitimacy and treaty compliance. Pace Environ Law Rev. 24(1):35–66.

- Arts J, Filarski R, Jeekel H, Toussaint B. Editors. 2016. Builders and planners: a history of land-use and infrastructure planning in the Netherlands. Delft (the Netherlands): Eburon.

- Arts J, Runhaar HAC, Fischer TB, Jha-Thakur U, van Laerhoven F, Driessen PPJ, Onyango V. 2012. The effectiveness of EIA as an instrument for environmental governance: reflecting on 25 years of EIA practice in the Netherlands and the UK. J Environ Assess Policy Manage. 14(4):1–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333212500251.

- Ashrafi B, Kloos M, Neugebauer C. 2021. Heritage impact assessment, beyond an assessment tool: a comparative analysis of urban development impact on visual integrity in four UNESCO World Heritage properties. J Cult Heritage. 47:199–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2020.08.002.

- Baker DC, McLelland JN. 2003. Evaluating the effectiveness of British Columbia’s environmental assessment process for first nations’ participation in mining development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 23(5):581–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-9255(03)00093-3.

- Bodansky D. 1999. The legitimacy of international governance: a coming challenge for international environmental law?. Am J Int Law. 93(3):596–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2555262.

- Breukel E. 2018. Dutch business culture and etiquette; egalitarian, individualistic, direct. Intercultural Communication. [Accessed 2020 Nov 05]. https://intercultural.nl/dutch-business-culture-and-etiquette/europe/e-breukel.

- Buitelaar E, Bregman A. 2016. Dutch land development institutions in the face of crisis: trembling pillars in the planners’ paradise. Eur Plann Stud. 24(7):1281–1294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1168785.

- Cashmore M, Bond A, Cobb D. 2008. The role and functioning of environmental assessment: theoretical reflections upon an empirical investigation of causation. J Environ Manage. 88(4):1233–1248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.06.005.

- Chanchitpricha C, and Bond A. 2013. Conceptualising the effectiveness of impact assessment processes. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 43:65–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.05.006.

- de Bony J. 2010. Project management and national culture: a Dutch-French case study. Int J Project Manage. 28(2):173–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.09.002.

- De Uitgeester. 2019. Terugblik ‘Heet Hangijzer’ opstelterrein NS in Uitgeest. [Accessed 2020 May 20]. https://www.uitgeester.nl/nieuws/algemeen/31389/terugblik-heet-hangijzer-opstelterrein-ns-in-uitgeest.

- de Vries J. 2015. Planning and culture unfolded: the cases of Flanders and the Netherlands. Eur Plann Stud. 23(11):2148–2164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1018406.

- Doberstein C, Millar H. 2014. Balancing a house of cards: throughput legitimacy in Canadian Governance Networks. Can J Polit Sci. 47(2):259–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423914000420.

- Driessen PPJ, Glasbergen P, Verdaas C. 2001. Interactive policy-making: a model of management for public works. Eur J Oper Res. 128(2):322–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(00)00075-8.

- Faludi A, van de Valk A. 1994. Rule and Order: dutch planning doctrine in the Twentieth Century. Dordrecht (the Netherlands): Kluwer Academic.

- Fielden K. 2019. Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites WHS still under threat of road construction. In: World Heritage Watch. World Heritage watch report 2019. Berlin (Germany): World Heritage Watch; p. 138–141.

- Gaillard B, Rodwell D. 2015. A failure of process? Comprehending the issues fostering heritage conflict in Dresden Elbe Valley and Liverpool: maritime Mercantile City World Heritage Sites. Hist Environ. 6(1):16–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750515Z.00000000066.

- Gerrits L, Rauws W, de Roo G. 2012. Dutch spatial planning policies in transition. Plann Theor Pract. 13(2):336–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.669992.

- Hajer M, Zonneveld W. 2000. Spatial planning in the network society: rethinking the principles of planning in the Netherlands. Eur Plann Stud. 8(3):337–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/713666411.

- Hurn BJ. 2007. The influence of culture on international business negotiations. Ind Commer Training. 39(7):354–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850710829058.

- ICOMOS. 2011. Guidance on heritage impact assessments for cultural World Heritage properties. Paris (France): ICOMOS. Accessed on 16 April 2021. https://www.icomos.org/world_heritage/HIA_20110201.pdf

- ICOMOS. 2015. Technical review: defence Line of Amsterdam. Paris (France): ICOMOS. Accessed on 16 April 2021. https://www.commissiemer.nl/projectdocumenten/00002453.pdf

- ICOMOS. 2017. ICOMOS advisory mission report: defence Line of Amsterdam. Paris (France): ICOMOS. Accessed on 16 April 2021. https://api1.ibabs.eu/publicdownload.aspx?site=noordholland&id=1100048374

- Iusmen I, Boswell J. 2017. The dilemmas of pursuing ‘throughput legitimacy’ through participatory mechanisms. West Eur Polit. 40(2):459–478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1206380.

- Jijelava D, Vanclay F. 2017. Legitimacy, credibility and trust as the key components of a Social Licence to Operate: an analysis of BP’s projects in Georgia. J Clean Prod. 140(Part 3):1077–1086. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.070.

- Kloos M. 2017. Heritage Impact Assessment as a tool to open up perspectives for sustainability: three case studies related to discussions concerning the visual integrity of World Heritage Cultural and Urban Landscapes. In: Albert M, editor. Perceptions of sustainability in Heritage Studies. Göttingen (Germany): De Gruyter; p. 215–227.

- Land-id. 2015a. Stelling van Amsterdam: heritage Impact assessment verbinding A8-A9. Arnhem (the Netherlands): Land-id.

- Land-id. 2015b. Stelling van Amsterdam: heritage Impact Assessment opstelterrein nabij Uitgeest. Arnhem (the Netherlands): Land-id.

- Louw E, van der Krabben E, Priemus H. 2003. Spatial development policy: changing roles for local and regional authorities in the Netherlands. Land Use Policy. 20(4):357–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00059-0.

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu. 2012. Structuurvisie infrastructuur en ruimte: nederland concurrerend, bereikbaar, leefbaar en veilig. Den Haag (the Netherlands): Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu.

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu. 2013. MIRT-onderzoek Noordkant Amsterdam (MONA): eindrapport. Den Haag (the Netherlands): Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu.

- Mottee LK, Arts J, Vanclay F, Miller F, Howitt R. 2020. Metro infrastructure planning in Amsterdam: how are social issues managed in the absence of environmental and social impact assessment?. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(4):320–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2020.1741918.

- O’Faircheallaigh C. 2009. Effectiveness in social impact assessment: aboriginal peoples and resource development in Australia. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 27(2):95–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155109X438715.

- Ochieng EG, Price ADF. 2009. Managing cross-cultural communication in multicultural construction project teams: the case of Kenya and UK. Int J Project Manage. 28(5):449–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.08.001.

- Othengrafen F. 2010. Spatial planning as expression of culturised planning practices: the examples of Helsinki, Finland and Athens, Greece. Town Plan Rev. 81(1):83–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2009.25.

- Patiwael PR, Groote P, Vanclay F. 2019. Improving heritage impact assessment: an analytical critique of the ICOMOS guidelines. Int J Heritage Stud. 25(4):333–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1477057.

- Patiwael PR, Groote P, Vanclay F. 2020. The influence of framing on the legitimacy of impact assessment: examining the heritage impact assessments conducted for the Liverpool Waters project. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(4):308–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2020.1734402.

- Pope J, Bond A, Cameron C, Retief F, Morrison-Saunders A. 2018. Are current effectiveness criteria fit for purpose? Using a controversial strategic assessment as a test case. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 70:34–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2018.01.004.

- ProRail. 2014. Information document: location choice train depot sprinters with Uitgeest as final destination. [Informatiedocument: locatiekeuze opstelterrein sprinters met eindstation Uitgeest]. Utrecht (the Netherlands): ProRail.

- ProRail. 2019. Geen opstelterrein voor Uitgeest. [Accessed 2020 May 20]. https://www.prorail.nl/overheden/nieuws/geen-opstelterrein-voor-uitgeest?.

- Provincie Noord Holland. 2014. Planstudie Verbinding A8-A9: notitie Reikwijdte en Detailniveau. Haarlem (the Netherlands): Provincie Noord Holland.

- RCE. 2020a. Behoedzaam ontwikkelen in de Stelling van Amsterdam: goedkeuring voor geoptimaliseerde oplossing. [Accessed 2020 May 20]. https://praktijkvoorbeelden.cultureelerfgoed.nl/praktijkvoorbeelden/behoedzaam-ontwikkelen-de-stelling-van-amsterdam/goedkeuring-voor.

- RCE. 2020b. Wie zijn betrokken bij het Nederlands Werelderfgoed?. [Accessed 2020 May 26]. https://www.cultureelerfgoed.nl/onderwerpen/werelderfgoed/wie-zijn-betrokken-bij-het-nederlands-werelderfgoed.

- Rozema JG, Bond AJ. 2015. Framing effectiveness in impact assessment: discourse accommodation in controversial infrastructure development. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 50:66–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2014.08.001.

- Runhaar H, van Laerhoven F, Driessen P, Arts J. 2013. Environmental assessment in the Netherlands: effectively governing environmental protection? A discourse analysis. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 39:13–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2012.05.003.

- Sanyal B. 2005. Preface. In: Sanyal B, editor. Comparative planning cultures. New York (USA): Routledge; xix–xxiv.

- Schmidt VA. 2013. Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: input, output and ‘Throughput’. Polit Stud. 61(1):2–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x.

- Stead D, de Vries J, Tasan-Kok T. 2015. Planning cultures and histories: influences on the evolution of planning systems and spatial development patterns. Eur Plann Stud. 23(11):2127–2132. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1016402.

- Stelling van Amsterdam. 2021. Stelling van Amsterdam: UNESCO Werelderfgoed. [Accessed 2021 Apr 15]. https://www.stellingvanamsterdam.nl/nl/historie/stelling-van-amsterdam.

- Strebel MA, Kübler D, Marcinkowski F. 2019. The importance of input and output legitimacy in democratic governance: evidence from a population-based survey experiment in four West European countries. Eur J Polit Res. 58(2):488–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12293.

- Taylor Z. 2013. Rethinking planning culture: a new institutionalist approach. Town Plann Rev. 84(6):683–702. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2013.36.

- Ton Y. 2019. Opstelterrein Uitgeest toch niet nodig voor hoogfrequent spoorvervoer. SpoorPro: Vakblad voor de Spoorsector. Rotterdam (the Netherlands). [Accessed 2020 May 20]. https://www.spoorpro.nl/materieel/2019/02/05/opstelterrein-uitgeest-toch-niet-nodig-voor-hoogfrequent-spoorvervoer/?gdpr=accept.

- UNESCO. 2021. Defence Line of Amsterdam. Paris (France): UNESCO. [Accessed 2021 Apr 16]. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/759.

- Valler D, Phelps NA. 2018. Faming the future: on local planning cultures and legacies. Plann Theor Pract. 19(5):698–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1537448.

- van Lente G. 1997. De groep, de kunst met groepen te werken. Utrecht (the Netherlands): Het Spectrum.

- van Rotterdam M. 2015. Werelderfgoed van Nederland: UNESCO - Monumenten van nu en de toekomst. Utrecht (the Netherlands): Uitgeverij Lias.

- van Straalen FM, van den Brink A, van Tatenhove J. 2016. Integration and decentralization: the evolution of Dutch regional land policy. Int Plann Stud. 21(2):148–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2015.1115338.

- Vanclay F, Baines JT, Taylor CN. 2013. Principles for ethical research involving humans: ethical professional practice in impact assessment part I. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 31(4):243–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.850307.

- Visser J, Hemerijck A. 1997. A Dutch Miracle: job Growth, welfare reform and corporatism in the Netherlands. Amsterdam (the Netherlands): Amsterdam University Press.

- Warsen R, Greve C, Klijn EH, Koppenjan JFM, Siemiatycki M. 2019. How do professionals perceive the governance of public-private partnerships? Evidence from Canada, the Netherlands and Denmark. Public Adm. 98(1):124–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12626.

- Woltjer J. 2002. The ‘public support machine’: notions of the function of participatory planning by Dutch infrastructure planners. Plann Pract Res. 17(4):437–453. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450216358.

- Zonneveld WAM, Evers D. 2014. Dutch national spatial planning at the end of an era. In: Reimer M, Getimis P, Blotevogel H, editors. Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe: a comparative perspective on continuity and changes. New York (USA): Routledge; p. 61–82.