ABSTRACT

This paper introduces a case where the SDGs have been integrated into the tender of an environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the construction of a new metro in Copenhagen, Denmark. The case gives insight into the impact that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can have on three phases of the EIA, namely i. pre-tender, ii. tender, and iii. post-tender process. By using the theoretical framework, ‘spaces for practice’ and action research, the study uses instances of collaboration between actors to understand how an EIA process responds to the introduction of new demands through the EIA tender. The study shows that incorporating SDGs as a part of the EIA tender can be a way of introducing innovations and new methodological approaches to EIA practice and reorienting conventional practices to provide greater opportunity for actor engagement, coordination, and negotiation, with the potential to drive EIA in more goal-orientated directions. In addition, the new spaces for stakeholder interactions have provided opportunities for collaborating on a commonly agreed approach towards SDG-integration, determining the appropriate scope of SDG relevance, and negotiating the role that SDGs should have in the forthcoming EIA process for the Copenhagen Metro project.

Introduction

A growing discourse on the need for sustainable development has not failed to put pressure on tender requirements. Ensuring that sustainability is an integrated part of the tenders between contracting authorities and their clients in environmental impact assessment (EIA), and other types of impact assessment (IA), is no exception to this trend. The EIA process consists of two tender opportunities: the first being the tender for conducting the EIA itself (hereon referred to as the EIA tender), and the second being the tender for the construction of the project that proceeds the completion of the EIA (hereon referred to as the procurement tender). These tender opportunities are illustrated in . The EIA tenders are the contracts for the EIA process and outlines the requirements for the commissioned consultant, such as a preliminary scope of relevant environmental factors for assessment. On the other hand, the procurement tender describes the requirements for the bidding contractor in terms of the implementation of the project itself based on the EIA project approval, e.g. choice of material, mitigation measures, and other project design properties.

Figure 1. An EIA consists of two tendering opportunities, the first for selecting a consultant to commission for conducting the EIA, and the second for selecting a contractor to construct/implement the project.

Independent of EIA, research on sustainability and tendering processes are generally centered around green public procurement, placing emphasis on the sustainable supply of products and services and of construction contracts (Varnäs et al. Citation2009; Braulio-Gonzalo and Bovea Citation2020). Several papers encourage implementing sustainability criteria into tenders (Alhola Citation2012; Parikka-Alhola & Nissinen Citation2012; Tambach and Visscher Citation2012; Montalbán-Domingo et al. Citation2018; Krieger and Zipperer Citation2022) and advocate for using these to award points to tenders in bidding (Braulio-Gonzalo and Bovea Citation2020). Some also propose green procurement as an opportunity for innovation and creativity (Sidwell et al. Citation2001; Ghisetti Citation2017; Eikelboom et al. Citation2018; Braulio-Gonzalo and Bovea Citation2020; Ntsondé and Aggeri Citation2021), but also question the extent to which they live up to this postulation (Cheng et al. Citation2018; Krieger and Zipperer Citation2022).

In EIA-tailored literature, there is a similar focus on the procurement tender, directed at tendering contracts for the construction and implementation of projects after its impacts have been assessed and the EIA report has been written. Uttam (Citation2014, p. 23) postulates that even if the procurement tender follows the completion of EIA, then EIA as a process can still formulate and integrate ‘ … environmental requirements in the tendering process’, thereby strengthening coordination between EIA and the green procurement of the resulting project (Uttam et al. Citation2012). Varnäs et al. (Citation2009) suggest that the procurement tender can help ensure that measures taken to reduce environmental impacts are followed up in the construction phase.

But what if employing sustainability requirements in the EIA originated early enough to be a central aim of the tender for the EIA process itself? Uttam (Citation2014) recognizes the benefits of linking procurement to the project planning and design phase of EIA, but even this discussion neglects that the initial EIA tender, which commissions consultants to bid on the EIA, may play a part in further integrating sustainability into the core of the EIA process itself. This paper directs attention to the potentials of integrating sustainability directly in the EIA tender, the hypothesis being that setting sustainability requirements in the early tender ignites new opportunities for innovation within the proceeding EIA process. Doing so would presumably shift innovative engagement away from contractors and towards relevant authorities, developers, and commissioned consultants involved in the EIA and create new innovative ‘spaces’ that are obligatorily rooted in regards for sustainability already from the EIA’s origin. Such a pursuit would require collaboration across practitioner groups, initially requiring project developers and authorities to agree upon the prominence of sustainability in the tender sent out to bidding consultants, and thereafter, requiring the collaboration between developers, authorities, and consultants to properly prescribe this to the process. Research on the influence of the individual in tendering processes (Eikelboom et al. Citation2018) draws parallels to EIA-centered literature on the influence of practitioners’ values and norms (Morrison-Saunders and Bailey Citation2009; Isaksson et al. Citation2009; Zhang et al. Citation2018) and motivations (Ravn Boess Citation2023) on the environmental assessment (EA) process being conducted.

In order to contextualize the concept of sustainability, this study turns to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the UN in 2015. A prominent discourse surrounding EA in general is the desire to shift practice to be more objective-led (Banhalmi-Zakar et al. Citation2018; Partidario Citation2020), which has directed attention to the SDGs in bringing the more strategic perspectives into the process (Kørnøv et al. Citation2020; González del Campo et al. Citation2020), expanding the comprehensiveness of the EA scope (Hacking Citation2019; Kørnøv et al. Citation2020; Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2020; Ravn Boess et al. Citation2021) and using them in the assessment of impacts (Castor et al. Citation2020; Kørnøv et al. Citation2020; Ravn Boess et al. Citation2021). González del Campo et al. (Citation2020) and Kørnøv et al. (Citation2020) suggest that SDGs can help to make EA more comprehensive and strengthen its weight amongst decision-makers, but also that EIA and SEA are tools well suited for assessing performance on the SDGs, monitoring progress, and guaranteeing that SDG integration is more holistic. Similar implications are supported by Hacking (Citation2019) who presents the concept of ‘stretching’ the ‘traditional EIA’ towards sustainability assessment (SA) (p. 6). Yet, bringing the SDGs from the global UN levels at which they were created to the local levels of project development is not without challenges. Firstly, the goals need to be ‘localized’ in order to provide value to local levels of governance (Fenton and Gustafsson Citation2017), which requires understanding the ‘… roles and responsibilities of actors … at the local levels’ (Fenton and Gustafsson Citation2017, p. 131) and that IA practice is ‘… “geared up” accordingly’ (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2020, p. 4) ‘… as an important vehicle for facilitating achievement of the SDGs’ (Morrison-Saunders et al. Citation2020, p. 1). But extending EIA to resemble SA also pulls into question a concern of tradeoffs between environmental, social, and economic factors, and how to preserve the environmental focus that EIA was initially established to have (Fischer Citation2020). And while these are not the primary concerns this research sets out to address, they become critical attention points for any attempts to work the SDGs into local contexts as well as an indication that their impact, whether positive or negative, on practice is still largely unexplored and unknown.

And it is precisely experimentation that some scholarly authors advocate for (see for example Kørnøv et al. Citation2020; Partidario Citation2020; Ravn Boess and González del Campo Citation2023; Ravn Boess Citation2024). In this pursuit for experimentation, Fischer (Citation2020) calls for a ‘… need to be adapted to the specific situation of application’ (p. 269) in order to provide value for IA practice. As Ravn Boess et al. (Citation2021) shows, concrete efforts to bring SDGs into EA are emerging and their various ways in which they can have an influence on EA are unfolding. But despite an emerging correlation between tendering and meeting the SDGs recognized by some firms (i.e. Nordic Co-operation Citation2021; Horton Citation2021), SDG integration in EIA tenders has not become common tendency in the field today. It should, however, be mentioned that the authors do not claim that examples of SDGs in EA-tenders cannot be found, merely that it is not standard practice.

This research has therefore been an attempt at bringing the SDGs in direct contact with EIA practice to gain insight into the opportunities for innovation they provide EIA when utilized as early as in the development of the tender, but also to better grasp what is required of various EIA actors to operationalize the goals. The empirical data comes from a single-case study of an EIA process for the development of a new metro (M5) in Copenhagen, Denmark. The case study has been a direct collaboration with the project developer of M5, namely Copenhagen Metro (CPH Metro). More specifically, this paper explores how integrating SDGs into the EIA-process tender proposed by the commissioning developer invites for new and innovative ways of thinking and engaging between EIA practitioners. Moreover, it provides a new approach for integrating the SDGs into EIA processes, whose methodological application and influence on EA practice is said to need conceptual clarification (Kørnøv et al. Citation2020). By applying the theoretical framework, ‘spaces for practice’, this research gains insight into the role of the tender to facilitate new ‘spaces for action’ in the EIA process, while also gathering insight into the motivation of project developers, authorities, and consultants in working with the SDGs and reworking the EIA process.

Case context and prior work with the SDGs

The case study is a newly proposed metro (M5) in Copenhagen, Denmark. M5 will serve existing urban areas as well as new districts and will also help relieve congestion on other metro lines in the city. Furthermore, M5 is expected to contribute to sustainable urban development in new districts of Copenhagen. The project falls under the scope of the EIA Directive due to its size and impacts (Directive 2014/52/EU, Directive 2011/92/EU). The relevant actors are representatives from the following organizations:

Copenhagen Metro (CPH Metro) – developers

Copenhagen Municipality (CPH Mun.) – authorities

COWI – commissioned consultants

The Danish Centre for Environmental Assessment (DCEA) from Aalborg University (AAU) – researchers

It should be noted that focusing on EA practitioners (developers, consultants, and authorities) as well as researchers, excludes insight from other perhaps influential stakeholder groups, such as the public, NGOs, and national political bodies. However, the practitioners and researchers were determined those most relevant for the study, considering the timing of the M5 case and that these actors are most typically involved at this stage of CPH Metro’s EIA tendering process.

The EIA process commenced mid 2022. The tendering process for M5 was initiated as a dialogue tender, meaning that the tender and bid are negotiable following their submission. divides the EIA tendering process into three phases, i. pre-tender, ii. tender, and iii. post-tender, which is then followed by the implementation and procurement process of the metro project itself.

Figure 2. An illustration of the components of the EIA tendering process, covering the three phases, i. pre-tender phase, ii. tender phase, and iii. post-tender phase.

At the time of writing this paper, the EIA for the project was in the process of being conducted by the commissioned consultants. CPH Metro, COWI and researchers from DCEA had been, since October 2020, collaborating in a research and innovation project, DREAMS, Digitally supported Environmental Assessment for the SDGs. The DREAMS project was a 3-year project (2020–2023) whose overall mission was to ‘promote progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by digitally transforming the way society accesses and communicates information about environmental impacts of projects and plans in order to enable the best decisions towards green transition in a transparent and inclusive democratic process’. This article specifically focuses on the research conducted for the incorporation of the SDGs in EA, distinguishing it from the digitalization aspect of the project. Research from the project includes, but is not limited to, providing guidance documents on assessing health impacts (Gulis Citation2023) and on climate assessments in a Danish practice (Lyhne et al. Citation2023), as well as shedding more light on how EA practitioners view SDG integration (Ravn Boess and González del Campo Citation2023), how the SDGs can contribute to filling gaps within EIA scoping practices (Ravn Boess et al. Citation2021) and the function that SDGs have in current EA practice (Ravn Boess et al. Citation2021).

Particularly two initiatives from the DREAMS project became foundational steps that had laid the preliminary grounds for identifying relevant SDGs for the M5 tender, prior to initiating the case study. Firstly, DREAMS project partners (DCEA, CPH Metro, Rambøll, COWI), including the authors of this paper, established a comprehensive overview of which SDG targets would be considered relevant in Danish EA contexts, the results of which are presented in a report (Ravn Boess et al. Citation2023). This initiative narrowed the 169 SDG targets that were developed on the UN level down to 57 deemed relevant for EA practitioners to consider when conducting EAs. These 57 targets served as grounds for the M5 project, recognizing that not all 57 targets would be relevant for M5 let alone metro projects more generally, and that they would require yet another reiteration to identify those most relevant for the specific case context. Secondly, CPH Metro and DCEA had been working to identify which SDGs would be relevant for CPH Metro to include in the assessment of their metro projects going forward. As a preliminary step in this process, the authors revisited an old EIA from 2008 (Metroselskabet I/S Frederiksberg Municipality Copenhagen Municipality Citation2008) and mapped relevant SDG targets according to the impacts identified in the non-technical summary of the report. This exercise was done to ensure that the contents of the non-technical summary and identified impacts would not be compromised if restructuring in terms of SDG impacts. This provided CPH Metro with a list of relevant SDG targets, now more targeted at metro projects in general, and while the intention was that this list could also serve as grounds for M5, M5 was also expected to contribute new insights to this list and extend understandings of how SDGs relate to metro projects more generally. At the beginning of the case study, iterative meetings between CPH Metro and DCEA were held to determine a comprehensive list of SDG targets relevant for M5, using both resources as guides.

Action research, collaboration, and methods

The chosen research design for the work shared in the article is action research which is defined by Reason and Bradbury (2011, p. 2) as ‘a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities.’, emphasizing initiation from a perspective of collaborative change with others. Action orientation is an extension of the project within which the research has been embedded, namely, the DREAMS project. The project was based on an expansive ecosystem of 15 societal actors, deliberately involving a diverse array of entities crucial to EA. Of the 15 societal actors in the project, CPH Metro, COWI and DCEA are those directly involved in this case study (CPH Mun. is involved in the case but was not a partner in the DREAMS project). This strategic design is rooted in the fundamental premise that transformative shifts towards enhanced sustainability transpire through the dynamic processes of transdisciplinary knowledge production and purposeful implementation. Challenges associated with action research are the threats of confirmation bias (as addressed by McSweeney Citation2021) and unequal power distributions with the role duality that researchers partake when both engaged in their own research topics and facilitating the action research opportunities (as addressed by Holian and Coghlan Citation2013). For this reason, this research is also characterized by reflexivity, as described by Kågström et al. (Citation2023), where discussions between EA practitioners and the researchers helped to create collaborative relationships and invited actors into the research process as contributors for empirical data collection, but also into the interpretation of these outcomes.

The engagement in collaborative relationships builds upon the understanding of collaboration within the field of EA as proposed by Kågström et al. (Citation2023), ‘the working together of researchers and practitioners in an interactive and complementary process to achieve the common goal of sustainable development through environmental assessment’ (Kågström et al. Citation2023, p. 1), which has implied a knowledge production characterized by mode 3 with high interdependency between researcher and societal stakeholders as well as high autonomy (Kørnøv et al. Citation2011). The engagement of EIA practitioners, including CPH Metro, the EIA consultant COWI, and CPH Mun., is thus paramount in the research process. Their perspectives and experiences have been integrated in the study. Notably, CPH Metro played a pivotal role in the research, transcending the conventional role of a stakeholder and participated actively in a collaborative, co-researcher capacity. unfolds the primary activities within the research process highlighting the substantive involvement of the developer (Copenhagen Metro) and the research entity (DCEA), underscoring a joint collaborative endeavor.

By engaging in a collaborative action research design, we aimed to produce knowledge useful to people in EIA practice, with the wider purpose of contributing to the SDGs through the integration of SDGs in EIA processes. In that way, the research also responds to the call in the special issue of EIA Review for further collaboration between researchers and practitioners in EA as a means for tackling sustainability challenges (Kågström et al. Citation2023).

The research has mainly centered around researcher, developer, and consultant narratives, meaning that the authority perspectives that have been incorporated are more indirectly gathered than the perspectives of other actors who were confronted more directly. We nevertheless claim that having collaborated with and consulted actors present at interactions with authorities, namely CPH Mun., for the M5 project has filled gaps of knowledge to an acceptable extent. Authority perspectives resonate throughout the paper as how the other involved actors have interpreted authority motivations, interests, and reactions through the key interactions presented. Therefore, authority perspectives have been present, albeit filtered through researcher, developer, and consultant observations and interpretations. This also means that internal authority interactions have not been recorded and any outcomes of such interactions, other than apparent shifts in attitude, are excluded from this paper. These perspectives remain for future research.

In the following, we describe the activities and related research methods. The description is structured according to the three phases of the process: i. pre-tender phase, ii. tender phase, and iii. post-tender phase. It should be mentioned that the EIA-process is, at the time of this paper, still ongoing. This last phase therefore builds on experiences from the process so far and the interactions proposed following the workshop are projections from COWI and CPH Metro in terms of what is planned to happen before completion.

Pre-tender phase

The case study, strategically chosen, presented an opportunity for discovering new ways of working with the SDGs within EIA and gaining insight into what can and cannot be done. In this inaugural phase of the research, the primary objective was to explore the broader integration of SDGs into EIA and thereafter, specifying this to the context of M5. Building upon this work, DCEA researchers offered and outlined a process for contributing expertise to the M5 EIA-tendering process as a segment of the DREAMS project. This resulted in the collaborative development of a scoping document for the M5 project, incorporating the SDGs. This scoping document was based on three sources. Firstly, CPH Metro had developed an initial scoping draft for M5 prior to the selection of the EIA as a case study, where relevant EIA factors were identified without relation to the SDGs. Secondly, the list of relevant SDGs derived from the non-technical summary of a historic EIA report (Metroselskabet I/S Frederiksberg Municipality Copenhagen Municipality Citation2008), as described in section 2, became a resource for M5. Lastly, CPH Metro used the list of 57 SDG targets determined relevant for a broader EA practice as a starting point, and in reviewing these, identified those they determined relevant for metro projects based on their experiences from conducting EIAs of other metro projects. The results were combined and provided a list of preliminary SDG targets that may be considered relevant for metro projects.

The list was thereafter qualified in meetings between CPH Metro and DCEA researchers to determine which targets would be relevant for the specific case study. This opened for discussions regarding how to ensure that the legislative requirements are fulfilled through SDG targets. The meetings also touched upon how comprehensive the scoping document should be, for instance, how many ‘new’ topics should be addressed that historically speaking have not been addressed in CPH Metro’s EIAs. As a result, a cross-reference, outlining how the selected SDG targets overlap with conventional EIA factors was made. Systematic notes from these discussions make up the primary empirical data for the pre-tender phase, recording the methods applied, challenges associated with these, as well as notes on the motivation and demotivation of the individuals and how these evolve overtime. The results of these discussions are presented in the results section of this paper.

Tender phase

The tender phase involved CPH Metro and the winning consultant, COWI, and was not been conducted as a part of the research process. The process was what CPH Metro defines as a negotiation tender, meaning that the tender text that is publicly announced is not the final text and can be negotiated through a ‘dialogue phase’ with the bidding consultants. Following the public announcement of the EIA tender, CPH Metro reviewed the M5 bids from the different consultancy firms and initiated prequalification and negotiation meetings with the consultants. In the prequalification round, COWI was asked whether they had any previous EIA examples with integrated SDGs. Next, COWI presented their competencies for meeting the requirements of the tender and answered questions on how they would be able to work with SDGs in the EIA regarding, for instance, whether the EIA could be structured according to the SDGs or whether COWI deemed it best that the EIA was structured more traditionally according to the EA factors. Following this early ‘dialogue phase’, CPH Metro edited the tender text, and this finalized tender text then became grounds for COWI’s bid. COWI hosted internal meetings and workshops centered around the development of the bid and how to integrate the SDGs. CPH Metro then internally evaluated the bids and selected the winning consultancy. The empirical data for this phase was collected through meetings between researchers from DCEA and the developers, CPH Metro, which recalled the attitudes and results of the ‘dialogue phase’ between developers and consultants. Additionally, the events of developing the bid were discussed during an interview between a DCEA researcher and the COWI project manager.

Post-tender phase

The post-tender phase, the stage commenced subsequent to the selection and contracting of the EIA consultant, COWI, encompasses two main activities. The first involved a facilitated workshop aimed at determining the optimal and agreeable mode of SDG integration within the EIA framework for the M5 project. The second entailed an interview with the COWI project manager overseeing the EIA process.

The participants at the workshop were representatives from CPH Metro (both those involved with the EIA process, but also one representative from their sustainability department), CPH Mun., COWI, and the two researchers from DCEA operating as facilitators. In the organization of the workshop, the researchers (the academic authors) played a pivotal role, taking charge of the conceptualization of the workshop, organizational aspects, presented content, and facilitating the entire session. The workshop was structured in the following manner:

1. Presentation phase

Introduction of the overarching DREAMS project

Inspirational presentation, elucidating various levels of SDG integration within EIA.

Illustration of different purposes and practical examples (collected through previous research) to stimulate thoughtful engagement.

2. SDG dialogue

Presentation of two distinctive models for SDG, each proposing alternative approaches.

Group work sessions dedicated to delving into the presented models.

Iterative discussions aimed at finalizing proposal for the subsequent course of action.

The two alternative models presented different perspectives on the interdependency between EIA and SDGs, the role of SDGs in EIA scoping, the methodology for SDG assessment, and the communication strategies surrounding the SDG assessment. This structured workshop approach ensured a comprehensive exploration of varied dimensions and fostered collaborative deliberation among participants. It is crucial to underscore, that despite the researchers guiding the discussion, the discourse itself was not led by the researchers. Instead, the researchers took notes from the discussions and recorded observations especially oriented at the motivation and attitudes of the participants and the actions they argued for conducting.

After the workshop, a follow-up interview was conducted by a DCEA researcher of a consultant for COWI that had also been present at the workshop. The interview was semi-structured (Kvale and Brinkman Citation2015) and had the primary purpose of understanding how consultants had reacted to the SDGs being incorporated into the EIA tender, what processes this had initiated internally at COWI and how the SDGs had been included in COWI’s bid. The interview was also conducted to gain insight into the process of SDG integration since the workshop, but because only a few weeks had passed from the workshop to the interview, this was limited. The interview was recorded, transcribed and thereafter coded for motivation for SDG integration of the consultant while composing the EIA bid for M5, the opportunities that the project manager believed the workshop to have presented, the actions performed since the workshop, and the challenges experienced as a result.

Theoretical foundations in ‘spaces for practice’

This paper explores how the introduction of new requirements in the tender of an EIA can facilitate a change in the EIA process and create new opportunities for practitioners to meet and negotiate a practice. This is a fundamental cornerstone of the theoretical framework, ‘spaces for practice’, which guides the theoretical considerations in this paper (Ravn Boess Citation2023). The theory helps to map the relations between an individual’s motivations and actions, as well as how they are influenced when individuals interact. The theory recognizes EIA as consisting of multiple actors (such as consultants, developers, planners, and authorities), each conducting an individual EIA practice. Each of these individuals have a ‘space’ for developing their motivations, called ‘spaces for motivation’, and spaces in which the EIA itself is conducted, called ‘spaces for action’. These two spaces reciprocally influence one another; motivation determines the actions that are conducted, and experiences gained from conducting actions influences an individual’s motivations. Action can be conducted either on an individual accord or through an interaction with others, respectively ‘discretionary spaces’ and ‘interactional spaces. ‘Discretionary action’ is performed by the individual, thus action that the individual practitioner is empowered to fulfill on their own accord and does not require the negotiation and approval of others. This ‘discretionary action’ can be as concrete as the assessment of impacts and writing the EA report but can be as abstract as deciding upon which arguments will be brought to into i.e. ‘interactional spaces’. These ‘interactional spaces’ (a concept inspired by Kågström (Citation2016)) are spaces in which two or more practitioners meet, discuss, and negotiate EA practice.

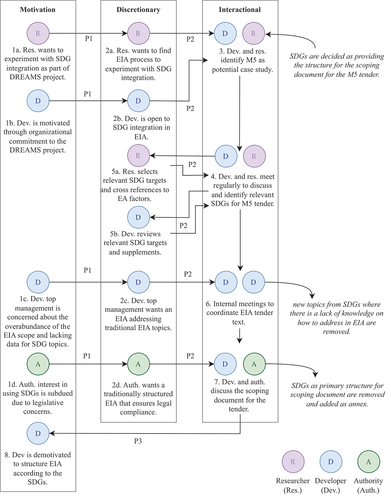

There exist inexplicable interrelations between these spaces, as shown in , which Ravn Boess (Citation2023) describes as relational pathways. Briefly told, motivation determines ‘discretionary action’, while actions performed in discretionary spaces can likewise influence an individual’s motivation (P1). Each individual practitioner brings action performed in ‘discretionary spaces’ into ‘interactional spaces’, where they are confronted by others (P2). The resulting negotiations can then go on to influence, e.g. collective actions, the ‘discretionary action’ performed by involved individuals (P2), and/or the motivation of the individuals partaking in the interaction (P3). Perceptions and actions that comprise these spaces can be enriched by newly introduced opportunities and can be restricted by limitations. In ‘spaces for motivation’ these are mostly perceived, while in ‘spaces for action’, they stem from experiences with, e.g. confrontations with other actors or experimentation with new methods. In this paper, the focus is mainly on the opportunities and limitations granted in interactional spaces where individuals meet to negotiate a practice. These are also depicted in .

Figure 4. A depiction of relational pathways between spaces for practice, as provided in Ravn Boess (Citation2023, p. 7).

This paper builds on an assumption that interactions between actors are crucial for and determinant of the EA process, echoing existing academic works addressing the importance of interactions in EA in producing better outcomes. Weaver et al. (Citation2008) reference collaboration between practitioners as a way to better improve the effectiveness of EIA, referring here to the EIA’s pursuit for more sustainable outcomes. They recognize the ability of professional bodies in promoting better communication and collaboration, just as they recognize the individual responsibility in not waiting ‘… for legislative reform to improve EIA practices’ (Weaver et al. Citation2008, p. 96). Morrison-Saunders and Bailey (Citation2009) find that a greater clarification of stakeholder roles, especially between regulators and consultants, can address potential tensions arising ‘… from differences in values, expectations and motivations for participating in EIA’ (p. 290). To this, they mention the potential of workshops and roundtable meetings to as means for ‘… sharing lessons learned and working on ways to improve EIA practices’ and highlight EIA practitioners’ willingness to engage in such practices (Morrison-Saunders and Bailey Citation2009, p. 293). Other works highlight interactions of stakeholders with researchers to close a gap between research and an impact in practice and the importance of researchers for joint learning and organizing platforms for collaboration and innovation (Kågström et al. Citation2023). Although not mentioned explicitly in the theoretical framework, creating new ‘spaces for practice’ would be categorized as an innovative pursuit within EA practice to facilitate interactions between actors. This study therefore analyses interactions and maps them, starting with the development of the EIA tender and finishing with the EIA process itself. It uses these interactions to understand the facilitation of new approaches to practice and the benefit of innovation and cocreation.

Results

The interest in working with SDGs in the EIA process began with the potentials discovered through the DREAMS innovation and research project, and using M5 as a case became an integrated part of this research. The findings illustrate the EIA tender’s role in the creation of new spaces for communication and collaboration between actors. These are centered around innovation for bringing the SDGs into the respective EIA for M5. First, this section describes the process from the tender to the EIA process by describing the interactions between actors and how the understandings of individuals have changed along the way. Afterwards, perspectives in terms of the theoretical framework, ‘spaces for practice’, are presented, delving into opportunities for innovation that the EIA tender has encouraged.

Interactions between actors in M5 tender/bid development and EIA process

Some of the interactions are unique to this EIA and are not characteristic of typical EIA processes that CPH Metro conducts. Some of these spaces would, in fact, not have been conducted had the M5 not been considered a case for SDG integration. Other interactional spaces, such as those involving the coordination between actors, are a standard practice, but were reported to have placed a heavier focus on sustainability and the SDGs than usual. The interactions are further elaborated in , which shows what actors were involved as well as the purpose of the interaction and the main outcomes. The purpose of the interactions is written in terms of SDG-integration, meaning that we recognize that interactions may have had other purposes that are not related to SDG integration in M5 but are not the focus of this paper.

Table 1. A description of the participants, and purpose of the key interactions between actors in the M5 case study.

‘Spaces for practice’

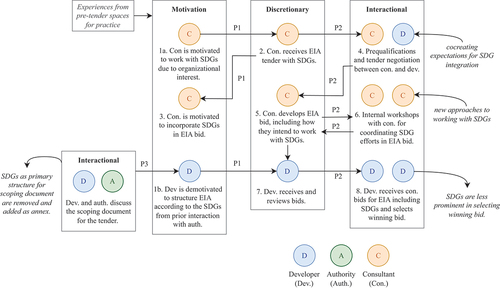

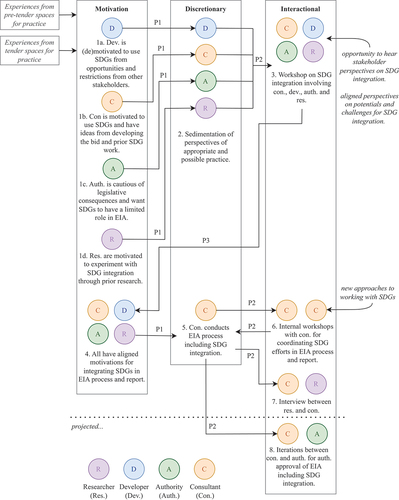

As outlined in , the case study consisted of several instances calling for collaboration amongst the individuals involved. These collaborations are characterized by bringing actor perspectives, motivations, and interests together and allow for opportunities to coordinate, confront, or complement these perspectives. In this way, they become ‘interactional spaces’ that invite for reorientation of and innovation for practice but can just as well allow for individuals to negotiate against new practices and maintain a status quo. This section delves into more detail of the interactions outlined in and demonstrate how an integration of the SDGs in the EIA tender create new spaces for actors to meet and coordinate their practice. The analysis recognizes the three ‘spaces’ from the theory, illustrated as ‘tracks’ in and . The first is ‘motivation’, outlining the motivation of the individuals. The second is ‘discretionary’, describing the actions conducted by the individual, ranging from the development of new approaches for SDG integration to clarifying which perspectives the individual will bring into interactions with other actors. Last is ‘interactional’, describing those instances where actors meet and negotiate practice.

Figure 5. The navigation between ‘spaces for practice’ in the pre-tender phase of the M5 EIA tendering process, involving developers, researchers, and authorities.

Figure 6. The navigation between ‘spaces for practice’ in the tender phase of the M5 EIA tendering process, involving consultants and developers.

Figure 7. The navigation between ‘spaces for practice’ in the post-tender phase of the M5 EIA tendering process, involving developers, consultants, authorities, and researchers.

Pre-tender phase

The navigation between spaces in the pre-tender phase is illustrated in . It involves first and foremost CPH Metro, both those working with the EIA and top management. Moreover, researchers from DCEA are involved as well as authorities, namely CPH Mun. The case study began with meetings between DCEA researchers and CPH Metro, in which ambitions and visions for SDG integration were discussed. These meetings can be seen as the first interactional space (3.) that initiates the case study. There were 7 meetings spanning from August 2022 to June 2023. In these meetings, the participants brought with them a motivation to work with the SDGs (1a. and 1b.), cultivated through an involvement in the DREAMS project. The ‘discretionary spaces’ of the researcher (2a.) and the developer (2b.) became a space for determining the interests that they bring into the interactions with one another. During these interactions (3. and 4.), CPH Metro expressed an interest in restructuring the EIA-tender such that the SDGs, rather than the environmental factors, provided the determining structure for the EIA and its tender. The meetings continued throughout the entire development of the M5 tender and gave an opportunity for the researchers to follow the changes occurring within the tender when involving other actors in the process, such as CPH Mun. Determining which SDGs, on a target level, may be relevant for the M5 project was an iterative effort between DCEA and CPH Metro. First, the DCEA researcher selected relevant targets in a ‘discretionary space’ (5a.), to be jointly reviewed in a joint meeting (4.), thereafter reviewed and revised by a representative from CPH Metro in their ‘discretionary space’ (5b.), and lastly, agreed upon in another meeting (4.). These identified SDG targets were intended as a focal point of the EIA tender, effectively setting the stage for an EIA structured around the SDGs. In order to preemptively address a concern that the individuals from CPH Metro expected top management to have, namely a concern of legislative compliance, a cross reference of the selected SDGs and the environmental factors was developed to demonstrate the inherent overlap and that none of the legislatively mandated environmental factors would be compromised through the new structure.

The development of the EIA tender also required CPH Metro to have internal meetings within the organization itself (6.), coordinating visions and gaining approval from top management. The discussion focused on the potential benefits of aligning the EIA with the SDGs. At the meetings, concerns were raised that the scope of the EIA could increase particularly in areas where no prior EIA experience exists (i.e. addressing SDG target 1.2 on how a new Metro may influence poverty levels in other countries by creating new employment opportunities to foreign workers). On the one hand, there is the risk of expanding the scope of an already comprehensive EIA with new topics that lack sufficient knowledge to back them up. On the other hand, these new topics inspired by the SDGs can be argued crucial for transforming the EIA into a sustainability assessment of the project. It was decided to preserve the focus on the topics that would traditionally be considered significant and, as such, not include topics for which there was an inherent lack of knowledge. The internal meetings within CPH Metro thereby revisited the relevant SDGs previously selected by developer and researchers and removed those determined to go ‘beyond’ the more traditional scope. CPH Metro top management had nevertheless approved the restructuring of the EIA tender to follow structure of the now refined list of relevant SDG targets. This demonstrates how differing motivations from within the same organization introduces new priorities and perspectives on practice.

Before the EIA tender could be finalized, it was confronted with the perspectives of CPH Mun. In interactions between developers and authorities, CPH Metro presented the visions coordinated in meetings with researchers and the scope of SDGs finalized by CPH Metro. Having established which SDGs were relevant to work with and having removed those that exceeded the traditional EIA scope, the main point up for discussion with CPH Mun. was structuring the EIA tender according to the SDGs. At the meetings (7.), it became clear that the municipality felt obliged to adhere to the traditional structure of the EIA as set out in the legislation, mainly to ensure that the legal requirements were being met. While EIA legislation claims that ‘sustainability … should constitute important elements in assessment and decision-making processes’ (Directive 2014/52/EU, L 124/2) and that relevant ‘environmental protection objectives established at Union or Member State level’ (Directive 2014/52/EU, L 124/17) should be addressed, then the specifications regarding how and the extent to which these should be accounted for remains up to interpretation. The developer reported that the municipality could not see the benefit of restructuring the EIA and found it to unnecessarily complicate the tender process. There was also a reluctance to engage in a scheme that would require extra work on the part of the municipality and would require new approaches that were, in practice, untried. Another concern was an uncertainty as to what consequences this may have in terms of legislative compliance; would it be difficult to identify the legislatively required environmental factors and thereby bring about a risk of forgetting or overlooking certain environmental factors. And lastly, there was a concern regarding the conflicts that may emerge in public hearings, redirecting focus of public engagement with little knowledge as to what the consequences may be. As a result, it was agreed that the EIA should be structured traditionally according to EIA factors rather than the SDGs, but the authority agreed to having sections in the chapters on each of the environmental issues, describing the result of the assessment in terms of the SDGs. As a result of this interaction, the individuals from CPH Metro that were originally motivated to experiment with new and innovative approaches to SDG integration were now demotivated to carry this through in the M5 tender (8.).

Tender phase

The navigation between spaces in the tender phase is illustrated in . It involves CPH Metro as developers and COWI as the consultant. The process of developing the bid in response to the EIA tender is mainly a study on how COWI, as the commissioned consultant responded to SDGs being a part of the M5 tender and how CPH Metro selected the winning bid. The insight into COWIs experiences and internal proceedings stems from the interview conducted with one of the consultants commissioned for the M5 EIA. According to the interviewed consultant, SDG integration is not a new topic at COWI and has been integrated into other EAs, meaning that the motivation (1a.) to work with the SDGs was already present before bidding on the M5 EIA. Receiving a tender centered around the SDGs (2.) further sedimented that motivation to incorporate SDGs in the M5 bid (3.). Initially, the consultancy met with CPH Metro in prequalification and tender negotiation meetings (4.). As mentioned in the interview, they were given an opportunity to provide input to the first draft of the tender and present their intentions with SDG integration. At this time, SDGs were still a prominent feature of the EIA tender, as the final decision to place SDGs as an annex to the tender was made after the consultants had made their initial bid.

According to the consultant, a significant portion of these early discussions were about how the EIA could assess sustainability and the extent to which it could be structured according to the SDGs. The consultant claimed that sustainability and the SDGs were granted more room throughout the EIA than usual because the developer was actively engaged in sustainability and directly addressed it in relation to the tender. The interviewee said, ‘It has definitely put it [sustainability] very high on the agenda, also here at COWI. When a big client suddenly requires it, then you simply need to buckle down’. By inviting the consultant into an ‘interactional space’ for negotiating the conditions of the tender prior to its final sedimentation was, at least for the interviewed consultant, a new approach to practice, and a benefit for the consultancy in terms of cocreating the expectations set in the tender. It also created a stronger sense of ownership of the forthcoming EIA process and the competencies needed to fulfill the tender requirements.

The consultant also described how the EIA process required more internal coordination at COWI to meet the demands of SDG integration set in the EIA-tender. Upon receiving the EIA-tender, the consultants began conducting the EIA in ‘discretionary spaces’ (5.), but also began coordinating internal workshops with the purpose of clarifying how COWI could address sustainability and the SDGs in their bid. In lieu of the theoretical framework, these internal meetings can be assigned as an ‘interactional space’ (6.) in which the individuals consultants begin negotiating and defining the work that they, as representatives of the consultancy, can conduct. According to the consultant, this process resulted in a bid that veered from traditional practices. Lastly, as described by CPH Metro, CPH Metro received and evaluated the submitted bids in the individual’s ‘discretionary spaces’ (7.) and selected the winning consultant as a collaborative and internal effort (8.). As a result of the meeting with CPH Mun. in the pre-tender phase, where SDGs were underprioritized according to original ambitions and were no longer a central part of the EIA structure, the motivation of CPH Metro to work with SDGs had diminished (1.b). The weight of sustainability and the SDGs in selecting the winning bid was subdued. The developer has since constituted that the approach to sustainability and SDG-integration was not a determining factor for the selection of the winning consultant.

Post-tender phase

The post-tender phase is where the EIA itself is being conducted. The ‘spaces for practice’ and the navigation between them are illustrated in . This phase involves all actors, namely CPH Metro as developers, COWI as the consultant, CPH Mun. as authorities and DCEA as researchers. Upon initiating the EIA process, a workshop (3.) was held with the purpose of discussing and determining what role the SDGs should have in the upcoming EIA. All actors brought with them different motivations (1a., 1b., 1c. and 1d.), that are influenced by their prior experiences in pre-tender and tender ‘spaces for practice’. CPH Metro (1a.) were influenced by prior interactions with DCEA researchers, CPH Mun. and COWI, initially characterized by a high motivation from meetings with motivated researchers, followed by reservations brought forth by authority skepticism, and lastly encouraged by the opportunities proposed by motivated consultants. The COWI consultants (1b.) brought with them the approaches proposed in the EIA tender for M5 and results from their internal workshops and meetings from developing the M5 bid. Motivation of the researchers (1d.) was characterized by prior research results, either advocating for or against SDG integration, and understandings of different methodological approaches. And lastly, individuals from CPH Mun. (1c.) were influenced by the prior meeting with the CPH Metro, at which the municipality had decided to remove the SDGs as part of the EIA tender. While these initial meetings had exhibited unwillingness to working with SDGs and an explicit rejection of engaging in new and otherwise unexplored approaches to practice, the mere participation of the authorities in the workshop nevertheless demonstrated a curiosity for engaging in dialogues across actors and a desire for being present in the negotiations.

These motivations and how they become perceptions of appropriate and possible practice are sedimented in ‘discretionary spaces’ (2.), such as experiences from prior work with SDGs, both in terms of what the individual practitioner has been involved in, but also in terms of the organizational culture surrounding SDG integration, i.e. company discourse, willingness, and traditionally practiced approaches, that define which perspectives the actors bring into the workshop (3.). In the interview, the COWI consultant claimed the workshop to have been a coordinated opportunity for hearing other’s perspectives on SDG integration and align initiatives for the role of SDGs in the M5 EIA process. According to observations from the workshop, CPH Mun. emphasized from the onset of the workshop that they did not wish to stifle development of new and more sustainable EIA practices, indicating that the position of the authority had shifted since the meetings with CPH Metro in the pre-tender meetings. The alignment of perspectives results in the adjustment of motivations (4.) in which the workshop participants have common notions of how the SDGs will be integrated into the remaining EIA process, as well as how it will be included in the EIA report.

From there, the consultants began conducting the EIA and corresponding SDG integration (5.). The interviewed consultant said they coordinated internal workshops in order to determine how the SDGs should be integrated into the EIA itself, which is a new approach to their EIA practice. Through the interview, the consultant also expressed a curiosity in terms of how the authority will respond to the new additions to the EIA, expecting that especially the representatives that were not present at the workshop would still not be entirely open to the integration of SDGs. To this, the consultant said, ‘how we write it and how they [the municipality] respond to it’ is essentially a ‘trial-run’. The iterations between consultants and the authorities (8.) were merely projected at the time of the interview and had not taken place yet. They will nevertheless constitute another ‘interactional space’ for actors to meet and respond to SDG integration, when that time comes.

Discussion

The discussion begins with a synthesis of the results and demonstrating the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the influence of and between ‘spaces for practice’. This section then goes on to discuss the findings that point towards innovation and approaches to practice in relation to the growing attention granted to the SDGs in EA practice.

Influence of ‘spaces for practice’

As the theory suggests, ‘interactional spaces’, where individuals meet, are for negotiating a practice and are opportunities for influencing involved actors. At least in this particular case study, because motivations of the researchers and developers were relatively aligned from the start, the initial meetings between the two became more of an opportunity to clarify uncertainties regarding how and to what extent the SDGs should be integrated in the EIA. They became crucial spaces for establishing developer motivation and the perceptions that would make it into the M5 tender. They thereby also became premises for the consultant’s bid. As the consultant interview revealed, motivation to work with sustainability and the SDGs is not new – it has persisted and developed throughout the individuals for some time. But because motivation of developers at CPH Metro to work with the SDGs had been established early in the process as a part of the EIA-tender, the motivation of the consultants to carry this through in practice was not stifled, but rather encouraged to materialize as an actualized practice.

On the other hand, motivations of the authority and developers were less aligned, making the space one characterized by confrontation, and as such, a readjustment of especially developer motivation. This case showed the developer’s ability to use their discretion to suggest to the authorities a scoping of relevant environmental factors and a new approach to the structure of the tender, but it also demonstrated the inherent dependency their discretion has on the attitudes of the authorities and the challenges that emerge as a result of discrepancies. As such, M5 showed the importance of including all relevant actors in not only the outcome of innovation and new approaches to practice, but also in the process itself. In this case, the process happened too isolated from and too rapidly for the authorities’ interest and support to keep up with new innovation. Concerns over the consequences of SDG integration also suggests the priority for authorities to maintain control over the EIA process, including, to some extent, the outcome and public opinion. This emphasizes the inherent unwillingness authorities might have in straying too far from traditional practices, especially in circumstances where consequences remain untried, and may complicate efforts for increased focus on sustainability throughout EIA. An aspect of this draws parallels to Stoeglehner et al. (Citation2009) who consider the concept of ‘ownership’ as crucial for effectiveness (albeit for SEA). If projecting similar assumptions onto EIA, this invites for speculations that having included authorities in the preliminary meetings between developers and researchers, where motivations, purposes for SDG integrations and visions between the actors were created and aligned, may have increased the authorities’ perception of ownership in the process, and as a result, the support for new approaches. The workshop was at the very least more successful in getting authorities on board as it invited authorities into initial negotiations for SDGs in the forthcoming EIA process at the very onset of the EIA.

As such, the workshop acted as a new interactional space in which developer, authority, consultant, and researchers could negotiate plans for the M5 EIA. It created a physical room for meeting face-to-face and for sharing, addressing, and managing concerns and potentials for SDG integration. Each participant (consultants, developers, authorities, and researchers) brought with them ideas and perceived practices, which, if referring to the theory, stem from their own ‘discretionary spaces’. By proposing a space dedicated for innovation, the workshop essentially allowed practitioners to detach themselves from a traditional EA practice and encourage new mindsets and ideas to emerge. This statement proposes two things. Firstly, it defines the entire process as an experimentation, eliciting COWI free reigns to try new approaches and learn from how these approaches are received by other actors – perhaps strengthened by support from the developers as established through the workshop. Secondly, it signifies the importance of presence in the ‘interactional spaces’, such as the workshop, in aligning visions, and suggests that those not present at the workshop have bypassed an opportunity to coordinate and negotiate wishes for SDG-integration. This both means that their understandings are absent from the negotiations in the ‘interactional space’, but it also means that they have not been granted the same opportunities for understanding the perspectives of the other participants. Thus, as the interviewed consultant implies, the motivations and perspectives of practice of those not in attendance in the newly proposed ‘interactional spaces’ have most likely remained unchanged. These findings from M5 also show the important role that research can have within EA processes as a facilitator of new approaches. The research-based facilitation of the workshop enhanced the process by grounding discussions in research results, fostering critical thinking and broadening the scope of potentials for exploring SDG integration. How the intervention of research will manifest itself in the final outcome of the M5 EIA is a matter of future research when the EIA process is at its close. But through the results presented in this paper, it can be concluded that research has opened for new motivations to be brought into ‘spaces for action’ and has been an active facilitator of an ‘interactional space’ that proved crucial in shaping pursuits for SDG integration in the EIA.

Thus, the ‘interactional spaces’ were designated spaces for breaking conventional practices. Spaces specifically targeted the clarification of SDG integration in the M5 EIA process had presumably not been created had it not been for perceived opportunities having enriched practitioners’ motivation in preceding spaces. Thus, new spaces for interactions between consultants were invented and with no/limited prior experiences to build upon, they are inherently innovative by construction; the approaches to SDG integration must be created to meet a developer demand. The interactions between actors in the development of the tender have thus, effectively permitted, and perhaps necessitated, the creation of new ‘interactional spaces’ later in the process.

Furthering debates on SDG integration

The study also provides a case study for grounding the SDGs in a local context, as advocated for by Fenton and Gustafsson (Citation2017) and Ravn Boess et al. (Citation2021). In doing so, it also brings attention to the possibility of using the EIA tender as a way to work with the SDGs, which, until now, has remained largely absent from scholarly literature on the SDGs in EA. The M5 case study demonstrates how the tender can be an opportunity for an early consideration of what SDGs are relevant for the specific EIA and allows for drawing more general conclusions on what SDGs may be relevant when considering a specific project type, in this case metro infrastructure. By inviting the SDGs into EIA practice, different actors (researchers, developers, top management, authorities and consultants) were brought together and given an opportunity to contribute to the selection of relevant SDG targets and determining the role they should play in the remainder of the EIA process. M5 has shed light on some of the debates that arise when linking SDGs to scoping practices especially concerning the role of SDGs in supplementing the EIA scope with new topics, and thus nuances suggestions made by Ravn Boess et al. (Citation2021) and Hacking (Citation2019). This work has presumably laid a foundation for CPH Metro in any future experimentation with SDG integration by providing a list of relevant SDG targets and has also equipped all actors with a better understanding of potential approaches to their integration.

The M5 case study also contributes insight into how motivations for SDG integration get translated into practice, which builds upon the motivational study conducted in Ravn Boess and González Del Campo (Citation2023); what was presented there as perceived opportunities and challenges is now confronted by the realities of practice. The motivational study, focused on consultant perspectives, saw a general interest in working with SDGs, but also prescribed their successful integration as depending on a present developer demand. And as seen in this research, it is precisely this developer demand that permits, or at the very least, eases, consultant innovation concerning elements that lie beyond EIA legislative requirements. The responsibility that consultants placed upon themselves in encouraging and conducting SDG integration (Ravn Boess and González Del Campo Citation2023) is now displaced amongst a wider array of actors. The workshop effectively removed method development for SDG integration from the sole domain of consultants and distributed to all participants.

This research also suggests that an SDG integration produces associated costs in terms of time and requires additional resources to execute, a concern also highlighted by consultants in Ravn Boess and González Del Campo (Citation2023). The interviewed consultant pointed out the implications of extra cost of resources, primarily in terms of human resources and know-how, required to meet new demands already associated with this M5 case. But the need for such costs can be assumed to diminish as the practice concretizes and new methods evolve. For instance, integrating the SDGs does not necessarily contradict a lean and focused EIA report – as more experience is gained with SDGs in EIA, a clearer picture of which topics are relevant to assess will emerge, allowing for the same level of simplicity as a traditionally structured and well scoped EIA. And as motivation becomes more aligned between actors and SDG integration less disputed, less time and resources will go into coordinating and negotiating the practice in the future.

Lastly, the M5 case study shows the challenge practice still faces if aiming to be more objective-led as otherwise encouraged by Partidario (Citation2020) and Banhalmi-Zakar et al. (Citation2018). The initial ambitions of developers and researchers started with wanting to structure the EIA according to the SDGs (an ambition that resembles radical integration according to the framework provided in Kørnøv et al. (Citation2020)) but ended with a more conservative integration model where the SDGs become elements in, rather than determinants for, the analysis of impacts. The role that concerns of legislative compliance has in readjusting actors’ motivations cannot be ignored, relaying also tendencies expressed in Ravn Boess and González Del Campo (Citation2023).

Conclusion

This paper is an exploration of how an integration of SDGs into an EIA tender for a new metro development project (M5) in Copenhagen, Denmark provides opportunities for facilitating new spaces for engagement between involved actors and, as a result, changes the tender and EIA process. M5 has shed light on some of the debates that arise when actors in the EIA tender process are confronted with new innovations, especially on how developer motivation can drive innovation, how support from authorities is imperative but not a given, and how dialogue across actors can reorient motivations. The case study has assigned the EIA tender as an opportunity for expanding EIA boundaries to go beyond traditional practices. It does so by inviting so-called ‘interactional spaces’ into the EIA process which allows for new engagements centered around SDG integration and that call for new ways of thinking and methods for implementation. This research identified challenges in gaining authority approval for SDG integration and has identified this as a primary hurdle in the case study. But it has also found benefits in these interactions through the establishment and reorientation of actor motivations, allowing practitioners to introduce new ambitions to other practitioners, and tailoring these motivations towards consensual ambitions of the EIA in question. Based on consultations of relevant actors, this had the added benefit of facilitating better understandings of other individuals’ perspectives and priorities, which otherwise would have been unaddressed. Through such, even authorities, who have the reputation of valuing EIA as a legislative check list when it comes to granting project approval and exhibited initial skepticism, could reorient themselves towards developer motivation to venture out into new possibilities for EIA. Bringing new approaches, such as the SDGs, into the EIA tender has solidified it as a developer demand and has, thus, eased consultants’ opportunities to experiment with approaches and methodologies more freely. This has resulted in more internal meetings and workshops conducted at the consultancy, both in terms of SDG integration in the EIA bid, but also in the forthcoming EIA process following commission.

The study is notably characterized by inviting researchers into the EIA process in an explorative setting rooted to an actualized EIA practice. Establishing the EIA process as an experimental element allowed easier access for researchers to actively engage in the proceedings, deliberately disseminate research to practice and for mutual exchange between theoretical findings and applied realities. Some of this refers to better understanding how actors in an EIA process interact and the value that can be captured from confrontations, especially ones that begin uprooting traditional EIA practice. Others pertain more directly to extending understandings of how the SDGs relate to an EIA practice, unfolding in particular, the potential role that the tender may have in their operationalization. While this research cannot conclude on whether innovation has shifted from contractors to actors involved in the EIA, then it has shown that rethinking EIA approaches can emerge from i. the engagement of research and practice through action research, ii. the introduction of new motivations as early as pre-tender phases of EIA, and iii. the utilization of SDGs to guide new objectives for EIA.

With this, the purpose of this study was to scrutinize the tender and the activities it enables, and not to determine whether the integration of SDGs into the EIA tender does in fact lead to a more sustainability-oriented EIA. This should be left for further research, for when the final EIA report is published and the M5 project is implemented. As such, it would be enriching for both theory and practice to follow up on the impact that SDG-integration has granted the EIA – have additional procedural elements made for a better EIA? And if so, do the costs in terms of time and resources outweigh potentials for a more sustainable metro project? And what role have the SDGs played in this regard? This reveals another avenue for further exploration, namely, to delve more specifically into the mechanics of SDG integration, and delve into the potentials of the internationally recognized sustainability framework for facilitating change – are these findings impacted by being a case of SDG integration, or is it merely the introduction of new initiatives into the EIA tender that pave the way for innovative approaches to practice?

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to participants from Copenhagen Metro, Copenhagen Municipality and COWI for their active participation and input. An earlier version of this manuscript has been published as an article contribution for the first author’s PhD thesis (Ravn Boess Citation2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alhola K. 2012. Environmental criteria in public procurement: focus on tender documents. Helsinki: Finnish Environment Institute.

- Banhalmi-Zakar Z, Gronow C, Wilkinson L, Jenkins B, Pope J, Squires G, Witt K, Williams G, Jon W. 2018. Evolution or revolution: where next for impactassessment? Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 36(6):506–515. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2018.1516846.

- Braulio-Gonzalo M, Bovea MD. 2020. Relationship between green public procurement criteria and sustainability assessment tools applied to office buildings. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 81:106310. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2019.106310.

- Castor J, Bacha K, Fuso Nerini F. 2020. SDGs in action: A novel framework for assessing energy projects against the sustainable development goals. Energy Res Social Sci. 68:101556. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101556.

- Cheng W, Appolloni A, D’Amato A, Zhu Q. 2018. Green public procurement, missing concepts and future trends – a critical review. J Cleaner Prod. 176:770–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.027.

- Eikelboom ME, Gelderman C, Semeijn J. 2018. Sustainable innovation in public procurement: the decisive role of the individual. J Public Procure. 18(3):190–201. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-09-2018-012.

- Fenton P, Gustafsson S. 2017. Moving from high-level words to local action—governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Curr Opin Sust. 26-27(26):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.07.009.

- Fischer TB. 2020. Editorial - embedding the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in IAPA’s remit. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 38(4):269–271. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2020.1772474.

- Ghisetti C. 2017. Demand-pull and environmental innovations: Estimating the effects of innovative public procurement. Technol Forecast Soc. 125:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.020.

- González Del Campo A, Gazzola P, Onyango V. 2020. The mutualism of strategic environmental assessment and sustainable development goals. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 82:106383–106389. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106383.

- Gulis G. 2023. Health in environmental assessment. Guidance on how to improve assessment of impacts on human health in a danish context. Denmark: University of Southern Denmark.

- Hacking T. 2019. The SDGs and the sustainability assessment of private-sector projects: theoretical conceptualisation and comparison with current practice using the case study of the Asian development Bank. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 37(1):2–16. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2018.1477469.

- Holian R, Coghlan D. 2013. Ethical issues and role duality in insider action research: challenges for action research degree programmes. Syst Pract Action Res. 26(5):399–415. doi: 10.1007/s11213-012-9256-6.

- Horton. 2021. How to apply the UN’s sustainable development goals in a tender procedure. [accessed 2023 July 6]. https://en.horten.dk/publications/articles/articles2021/how-to-apply-the-uns-sustainable-development-goals-in-a-tender-procedure.

- Isaksson K, Richardson T, Olsson K. 2009. From consultation to deliberation? Tracing deliberative norms in EIA frameworks in Swedish roads planning. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(5):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2009.01.007.

- Kågström M. 2016. Between ‘best’ and ‘good enough’: How consultants guide quality in environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 60:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2016.05.003.

- Kågström M, Faith-Ell C, Longueville A. 2023. Exploring researcher’ roles in collaborative spaces supporting learning in environmental assessment in Sweden. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 99:106990. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106990.

- Kørnøv L, Lyhne I, Davila JG. 2020. Linking the UN SDGs and environmental assessment: Towards a conceptual framework. Environ Impact Assess Revi. 85:106463–106469. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106463.

- Kørnøv L, Lyhne I, Vammen LS, Hansen AM. 2011. Change agents in the Field of Strategic Environmental Assessment: What does it involve and what potentials does it have for research and practice?. Jou Env Assmt Pol Mgmt. 13(02):203–228. doi: 10.1142/S1464333211003857.

- Krieger B, Zipperer V. 2022. Does green public procurement trigger environmental innovations? Res Policy. 51(6):104516. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2022.104516.

- Kvale S, Brinkman S. 2015. Interview: Det kvalitative forskningsinterview som håndværk Vol. 3. Copenhagen, Denmark: Hans Reitzals Forlag.

- Lyhne I, Kørnøv L, Munk LH, Kristensen KS, Wael SM. 2023. Væsentlighed af klimapåvirkninger. Tilgange til at vurdere væsentlighed af drivhusgasudledninger i miljøvurderinger. Aalborg, Denmark: Aalborg Universitet.

- McSweeney B. 2021. Fooling ourselves and others: confirmation bias and the trustworthiness of qualitative research – part 1 (the threats). JOCM. 34(5):1063–1075. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-04-2021-0117.

- Metroselskabet I/S Frederiksberg Municipality Copenhagen Municipality. 2008. Cityringen. VVM-redegørelse og miljørapport. (Schweitzer Kbh).

- Montalbán-Domingo L, García-Segura T, Sanz MA, Pellicer E. 2018. Social sustainability criteria in public-work procurement: An international perspective. J Cleaner Prod. 198:1355–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.083.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Bailey M. 2009. Appraising the role of relationships between regulators and consultants for effective EIA. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 29(5):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2009.01.006.

- Morrison-Saunders A, Sánchez LE, Retief F, Sinclair J, Doelle M, Jones M, Wessels J, Pope J. 2020. Gearing up impact assessment as a vehicle for achieving the UN sustainable development goals. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 38(2):113–117. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2019.1677089.

- Nordic Co-operation. 2021. Sustainable public procurement is an effective way to achieve global goals. [accessed 2023 July 6]. https://www.norden.org/en/news/sustainable-public-procurement-effective-way-achieve-global-goals.

- Ntsondé J, Aggeri F. 2021. Stimulating innovation and creating new markets – the potential of circular public procurement. J Cleaner Prod. 308:127303. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127303.

- Parikka-Alhola K, Nissinen A. 2012. Environmental impacts and the most economically advantageous tender in public procurement. Jour Pub Procur. 12(1):43–80. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-12-01-2012-B002.

- Partidario MR. 2020. Transforming the capacity of impact assessment to address persistent global problems. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 38(2):146–150. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2020.1724005.

- Ravn Boess E. 2023. Practitioners’ pursuit of change: A theoretical framework. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 98:106928. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2022.106928.

- Ravn Boess E. 2024. Sustainable development goals in environmental assessment: abilities to change and practice and pursue a greater sustainability focus. Aalborg Denmark: Aalborg University Open Publishing. ISSN: 2446-1628.

- Ravn Boess E, González del Campo A. 2023. Motivating a change in environmental assessment practice: Consultant perspectives on SDG integration. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 101:107105. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107105.

- Ravn Boess E, Kørnøv L, Coutant AE, Jensen JU, Jantzen E, Kjellerup U, Partidário MR. 2023. UN sustainable development goals in environmental assessment practice: a danish standard. Aalborg, Denmark: The Danish Centre for Environmental Assessment. Aalborg University.

- Ravn Boess E, Kørnøv L, Lyhne I, Partidário MR. 2021. Integrating SDGs in environmental assessment: Unfolding SDG functions in emerging practices. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 90:106632. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106632.

- Ravn Boess E, Lyhne I, Davila JG, Jantzen E, Kjellerup U, Kørnøv L. 2021. Using sustainable development goals to develop EIA scoping practices: The case of Denmark. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 39(6):463–477. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2021.1930832.

- Sidwell AC, Budiawan D, Ma T. 2001. The significance of the tendering contract on the opportunities for clients to encourage contractor-led innovation. Constr Innovation. 1(2):107–116. doi: 10.1191/147141701701571652.

- Stoeglehner G, Brown AL, Kørnøv BL. 2009. SEA and planning: ‘ownership’ of strategic environmental assessment by the planners is the key to its effectiveness. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(2):111–120. doi: 10.3152/146155109X438742.

- Tambach M, Visscher H. 2012. Towards energy-neutral new housing developments. Municipal climate governance in the Netherlands. Eur Plan Stud. 20(1):111–130. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.638492.

- Uttam K. 2014. Seeking sustainability in the construction sector: opportunities within impact assessment and sustainable public procurement. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-144885.

- Uttam K, Faith-Ell C, Balfors B. 2012. EIA and green procurement: Opportunities for strengthening their coordination. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 33(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2011.10.007.

- Varnäs A, Balfors B, Faith-Ell C. 2009. Environmental consideration in procurement of construction contracts: current practice, problems and opportunities in green procurement in the Swedish construction industry. J Cleaner Prod. 17(13):1214–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.04.001.

- Varnäs A, Faith-Ell C, Balfors B. 2009. Linking environmental impact assessment, environmental management systems and green procurement in construction projects: lessons from the City Tunnel Project in Malmö, Sweden. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 27(1):69–76. doi: 10.3152/146155109X410869.

- Weaver A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Lochner P. 2008. Contributing to sustainability as an environmental impact assessment practitioner. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 26(2):91–98. doi: 10.3152/146155108X316423.

- Zhang J, Kørnøv L, Christensen P. 2018. The discretionary power of the environmental assessment practitioner. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 72:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2018.04.008.