ABSTRACT

Imaginaries of touristic otherness have traditionally been closely related to geographical distance and travel far away from the everyday. But in today's context of sustainable tourism, a moral and behavioral shift may be expected, toward traveling near home. Distance may actually become a disadvantage and proximity a new commodity. This implies a need to disentangle subjective understandings of both distance and proximity in relation to perceived attractiveness of and touristic behavior in places near home. Thus, it is aimed to shed light on how ‘proximity tourism’ is constructed, endorsed and appreciated (or not).

An online survey (N = 913) was administered to residents of the Dutch province of Friesland, exploring their attitudes toward their home province as tourism destination and representations of proximity and distance in relation to preferred vacation destinations. We grouped respondents into four categories, reflecting destination preferences: (1) proximate, (2) distant, (3) intermediate and (4) mixed. These groups were differentiated and characterized using quantitative and qualitative analyses. The ‘proximate’ and ‘distant’ preference groups, respectively, were most and least engaged in proximity tourism. However, the perceptions of proximity and distance expressed by the ‘intermediate’ and ‘mixed’ preference groups were associated in a nonlinear way with appreciation of the home region as a tourism destination. Additionally, respondents used proximity and distance in various ways as push, pull, keep and repel factors motivating their destination preferences.

Interpretations of both proximity and distance were thus important in determining engagement in proximity tourism and, in turn, the potential for proximity tourism development in the region. This implies that such development will require a balanced consideration of the relative, temporally sensitive ways that people negotiate distance and proximity in their perceptions of being at home and away. Our results advance the discussion about imaginaries of travel, distance and proximity, and their impact on regional tourism.

抽象

旅游者对他者感的想象传统上与地理距离和远离日常生活的旅行密切相关,但是在当今可持续旅游背景下,可能期望人们在道义和行为上转变到近家旅行。远方实际上可能成为一种劣势而(邻)近家(乡)可能成为一种新的机会,这暗示有必要理清与近家旅游吸引力和旅游行为有关的远近因素的主观理解。因此本文旨在阐释(不)建构、认可与重视近家旅游的过程。本文对荷兰弗里斯兰省居民进行了在线调查(样本量为913),探讨他们把本省作为旅游目的地的态度以及远近因素在度假目的地偏好方面的表现。根据他们的目的地偏好,我们把被试分成四类: (1)近距离旅游者,(2)远距离旅游者,(3)中间距离旅游者和(4)混合型旅游者。运用定量和定性方法区分了这些群体并且概括了他们的特征。近距离和远距离偏好群体各自是参加近家旅游最多和最少的群体。但是中间距离和混合型旅游偏好群体对远近因素的感知与把家乡地区作为旅游目的地的认识存在非线性的关系。另外,受访者在旅游目的地偏好激发方面以各种方式运用远近的概念,比如推力因素、拉力因素、保持因素和抵制因素。因此,在决定近家旅游参与,进而发展近家旅游的潜力时对远近因素的解读非常重要。本研究暗示,发展近家旅游需要全面地考虑人们对近家旅游或外出旅游认知时以相对地、权变的方式协商远近因素。我们的结果有助于推动旅行、远近因素以及它们对区域旅游影响的讨论。

Introduction

Tourism is imbued with imaginaries of escaping the mundanity of everyday life and engaging with otherness (Salazar, Citation2012). This dynamic has received extensive attention in tourism scholarship and is arguably hegemonic in the social discourse about and the meanings attributed to the phenomenon of tourism (in Western societies and quickly spreading beyond). By stressing economically attractive international destinations and overnight stays, the tourism industry (still) conveys a narrative of going abroad (i.e. international travel and crossing nation-state borders) and exploring unfamiliar territories. Yet, looking closer, a more nuanced picture emerges. Most people spend vacations relatively near home, within their countries of residence (UNWTO, Citation2008). Also, while the exotic is not always physically distant, otherness is not always sought; it is sometimes even consciously avoided (Mikkelsen & Cohen, Citation2015).

The subjectivity of distance and proximity plays an important role in the spatial distribution of tourists, destinations and touristic activities. Distance and proximity not only represent physical parameters, but the subjectivities attached to them influence which places travelers appreciate as attractive and which are perceived as unattractive to visit. This is particularly informative in the context of the ‘competitive identity’ of destinations (Anholt, Citation2007). Not only may too-distant destinations be arguably less attractive, but too-proximate destinations might also be seen as unfavorable. Places near home may seem too familiar and mundane to serve the needs associated with being on vacation.

However, various scholars maintain that tourism without long travel distances is necessary, given the limited supplies of fossil fuels and negative effects in terms of transport costs and carbon footprints (Becken & Hay, Citation2007; Dubois, Peeters, Ceron, & Gössling, Citation2011; Peeters & Dubois, Citation2010). Hall (Citation2009) called for a ‘steady state tourism’ paradigm with less emphasis on growth or gross domestic product (GDP), and more attention to qualitative development and a balance between (ecological) costs and (economic) benefits. Among other things, this implies less emphasis on long-haul travel. It seems unlikely, though, that people will refrain from travel for environmental reasons, as that contradicts the hedonic value of touristic behavior. Moreover, Larsen and Guiver (Citation2013) found that people develop a need for distance, in which travel is functional, as the journey itself becomes important in order to experience difference and ‘get away from it all.’

Conversely, and despite (or thanks to) few places remaining unaffected by the powerful effects of commodification (Cole, Citation2007), a broader social counter-dynamic may emerge characterized by revived attractiveness and importance of local production and consumption (e.g. in food choices) (Feagan, Citation2007; Haven-Tang & Jones, Citation2005). In line with this tendency, tourism scholarship has increasingly refocused on the benefits of the mundane, the familiar and the proximate, through which everyday life and tourism intermingle (Franklin & Crang, Citation2001; Pearce, Citation2012). For example, Mikkelsen and Cohen (Citation2015, p. 20) argued that tourism studies should now also turn to ‘everyday contexts where tourism and the mundane intersect, and to the diversity of experience within them.’ Canavan (Citation2013) noted, however, that many studies on domestic tourism lack sensitivity to microlevel processes, due to which a ‘detailed understanding of and nuances within domestic tourism may go unremarked, unexplained, and unaddressed’ (Canavan, Citation2013, p. 340). Many aspects of what can be called proximity tourism (Díaz Soria & Llurdés Coit, Citation2013) are therefore still relatively little understood, though its most extreme form – the ‘staycation’ in which people spend their vacation at home – has received some attention (Alexander, Lee, & Kim, Citation2011). This concept of vacation near home has been arguably triggered by the economic crisis that emerged in the first decade of this century. Still, much is left to be discovered about whether and to what extent familiar and physically proximate places can be or become attractive tourism destinations. Similarly, we might question whether proximity tourism could be prompted or promoted by a drive to behave responsibility by acting locally near home (as opposed to acting locally far away), enhancing one's own regional economy, local culture and social networks.

Therefore, there is a need to disentangle the ways that subjectivities of distance and proximity affect the image and attractiveness of destinations that are physically close to home. This paper aims to do just that, guided by the following research questions:

RQ1:

How do people with varying preferences for vacation destination proximity differ in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes toward proximity tourism and intraregional tourism behavior?

RQ2:

How are proximity and distance represented in motivations for engaging (or not engaging) in proximity tourism among people with various preferences for vacation destination proximity?

The paper is structured as follows. First, a theoretical argument is presented for the relevance of subjective perceptions of proximity and distance for understanding tourist motivations, destination attractiveness and tourism behavior. After providing details on the research context, methodology and sample, the quantitative and qualitative results are presented. Quantitative data provide insight on the relationship between preferences for proximity or distance in vacation destinations and sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes towards proximity tourism and intraregional touristic behavior (RQ1). Qualitative data focus on people's motivations for spending a vacation within their province of residence or somewhere more distant, and the different ways that people understand and use proximity and distance to justify their choices (RQ2). Based on these results, implications for both the academic study of tourism and tourism practice are presented and discussed.

Literature review

Distance and proximity in a tourism context

Given the importance of travel in tourism, it is no surprise that distance between people's everyday dwelling and their vacation destination has received much attention. While objective measures of physical distance (e.g. Euclidian distance) are a popular way to conceptualize spatial differences, for example, in transport models (Peeters & Dubois, Citation2010) or analyses of destination accessibility (Celata, Citation2007), these approaches typically neglect the contextual and relational aspects of distance. Yet, the subjectivity of distance and proximity is an important factor in destination choice, tourist behavior and tourist experiences, and it determines how physical distance is translated into actual experiences and place narratives.

Helpful in linking the objective and subjective aspects of distance and proximity are Larsen and Guiver's (Citation2015) three ‘layers’ of distance. The first layer is objectively measured spatial separation. The second layer involves the relational aspects between objects across space; it is through this layer that physical separation becomes relevant. In the third layer, relationships across physical space are contextualized, hereby suggesting meanings of relationships between places and allowing people to interpret distance and proximity in various ways. It is particularly through these relational second and third layers that distance becomes meaningful and is experienced.

Importantly, the way these contextualizations are represented in people's experiences can take different, interrelated forms (Larsen & Guiver, Citation2013). First, distance is a resource and interpreted in terms of the time and financial cost of traversing physical divides. Second, the fact of distance is experienced, for example, in the sensation of moving or perception of changing scenery and climate (Jeuring & Peters, Citation2013). Moreover, traveling can induce a sense of liminality and ‘in-betweenness’ (Olwig, Citation2005). Third, ordinal interpretations are discerned (e.g. a place being perceived as ‘near’ or ‘far’) (Larsen & Guiver, Citation2013). These are often relative too, for example, with one destination perceived as ‘farther away’ than another. Fourth, a zonal sense is inherent to being ‘here’, or ‘not here’, highlighting the importance of spatial separation (e.g. between home and away) without any particular geographical reference.

Such representations profoundly impact how people engage in touristic behavior and encounter the (un)familiar other, which is not just physically, but also culturally proximate or distant (Kastenholz, Citation2010; Ryan, Citation2002). There appears to be an optimal level of cultural proximity in terms of positive destination image (Kastenholz, Citation2010). This was substantiated by a study in the Netherlands on the images Dutch residents held of the country's different regions (Rijnks & Strijker, Citation2013). People living near the Veenkoloniën region, for instance, were less positive about the region than both residents of the region and people living farther away, suggesting a means of ‘othering’ from places and groups that seem too nearby.

In the context of tourism, interactions between place and self are likely complicated by the different roles associated with being a tourist and a resident. Such roles may be maintained and magnified by stereotypes and imaginaries aimed at attracting incoming tourists, while not taking into account the perceptions of local visitors. This was highlighted by a study in Israel that found people vacationing in their home country were forced to negotiate between different self-identities (Singh & Krakover, Citation2015). These tourists, though acknowledging being engaged in touristic activities, resisted being labeled tourists. Culturally embedded aspects thus likely play a role in the extent that people appreciate their home environment as attractive for tourism and the ways that perceptions of place, purpose and identity interact.

Distance, proximity and travel motivations

Perceptions of difference, cultural proximity and otherness are closely related to people's motivations for traveling across distances and escaping everyday mundanity. The motivations for going on a vacation, while varying between people, are less widespread than the ways people can meet their vacation needs and the destinations they can visit. Meeting and experiencing the Other in various touristic activities is well studied and is a major trigger for tourism travel, even though much tourism is constructed around routines and normative conventions (Edensor, Citation2013). Moreover, some tourists appear to go on a vacation to create an environment in which familiarity and routine play an important role (e.g. Mikkelsen & Cohen, Citation2015). More generally, it has been theorized that people prefer a comfortable balance between familiarity and unfamiliarity (Cohen, Citation1979; Edensor, Citation2007), with certain destinations and activities falling within people's bandwidth of unfamiliarity (Spierings & Van Der Velde, Citation2008) and others not.

Thus, there is a delicate interaction between perceptions of a place being suitable for tourism purposes or for everyday purposes. Some people travel far to arrive in a place where they expect to meet their needs, while others prefer to stay at or close to home. Important motivational forces affecting mobility are push and pull factors (Prayag & Ryan, Citation2010), ‘denoting perceptions of physical-functional and socio-cultural differences between places at home or “here” and on the other side or “there”’ (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012, p. 10).

Push factors are associated with a current dwelling (i.e. home) that is perceived to be unattractive, while pull factors pertain to a perceived relative attractiveness of another place (i.e. a tourism destination). Additionally, keep and repel factors (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012) are motives for immobility, respectively, pertaining to the perceived attractiveness of ‘here’ and the perceived unattractiveness of ‘there’ (). Various push, pull, keep and repel factors not only affect the comparisons people make between home and a tourism destination, they also underlie comparisons between destinations. Likewise, such motivational factors affect whether people see places in the proximity of their home as potentially attractive to spend a vacation, either for themselves or for others.

Figure 1. Motivational forces for (im)mobility (based on Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012).

Similar relational interpretations of distance and proximity have been proposed in a number of studies, across a variety of tourism contexts. For example in cross-border shopping trips people engage with both the familiar and the unfamiliar in close geographical proximity (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012; Szytniewski & Spierings, Citation2014). The (often only imaginary) state borders enhance experiences of unfamiliarity through experiences, information and self- in a complex dynamic across time and space. The extensive scholarship on second-home tourism points to a tendency to mix touristic needs and activities with everyday life environments (Marjavaara, Citation2008; Mottiar & Quinn, Citation2003; Müller, Citation2011). The second-home tourism contexts highlights how tourist experiences are possible physically very close to home, while at the same time demonstrating the importance of building place attachment and a sense of familiarity through tourism, at places other than one's main residence (Wildish, Kearns, & Collins, Citation2016). In sum, subjectivities of proximity and distance are central to one of the main paradoxes of tourism. Proximity and distance are both polarizing and relational, they attract and oppose, comfort and alienate, motivate and constrain, affecting touristic experiences and behavior in myriad ways.

Though individually expressed, people's experiences and behaviors are shaped by social dynamics, reinforced by tourism imaginaries (Salazar, Citation2012). Sometimes these are pushed to the limits by tourism marketing (Jeuring, Citation2015; Pike & Page, Citation2014; Ren & Blichfeldt, Citation2011; Warnaby & Medway, Citation2013), in which socio-spatial identifiers such as nations and regions are used to discern between self and other, between home and away. Uneven capitalization of push and pull factors (i.e. the attractiveness of relatively distant visitors) at the expense of keep and repel factors (i.e. the attractiveness of relatively proximate visitors) may undermine the wellbeing of the more local, familiar stakeholders, particularly residents. Such an imbalance is evident in some destination marketing (Jeuring, Citation2015), but is often also directly experienced, for example, in the increased pressure tourism exerts on cities (Kavaratzis & Ashworth, Citation2007; Neuts & Nijkamp, Citation2012).

In light of the abovementioned negative externalities associated with touristic travel across physical distances, it has never been more justified than now to wonder how familiar, usual environments might be revalued (Díaz Soria & Llurdés Coit, Citation2013) and what strategies could be developed to enhance tourism near home (Gren & Huijbens, Citation2015). In this vein, the nonlinear dynamics between physical and subjective proximity and distance in tourism is a topic meriting further scrutiny, to better understand why some people spend their vacation close to home, while others do not. An initial step is to seek insight into how people come to see their familiar, proximate environment as attractive for tourism and how this relates to preferences for spatially separate destinations.

Methodology

Study area

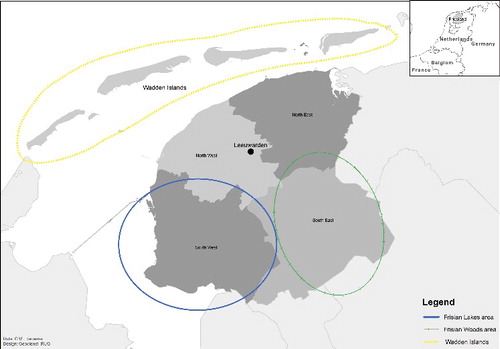

Our study centered on the Province of Friesland in the northern Netherlands. Its population numbers some 650,000 and the largest city is the provincial capital of Leeuwarden, which had 107,800 inhabitants in 2015. The province is known for its strong regional identity, and even has its own officially recognized language. Main touristic attractions are the region's many natural freshwater lakes and the islands along the northern coast and the Wadden Sea World Heritage Area. More inland, Friesland's mostly rural territory is characterized by interspersed forested and agricultural landscapes ().

Tourism in Friesland is mostly seasonal and peaks between June and August. Popular vacation pursuits include watersports and cycling, with camping grounds and caravan parks providing accommodation for many. Both long vacations and daytrips to the Wadden Islands are popular, and culturally oriented visitors seek out museums and pay visits to the ‘Eleven Cities’, a group of historical towns that obtained their city rights between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Increasing numbers of festivals and events are also being organized, with many taking place between April and September.

In regional destination marketing, a clear distinction is made between the Wadden Islands and the Frisian mainland. Similarly, tourism policy is increasingly being executed on a subprovincial level, discerning five intraprovincial regions: the Wadden Islands and the mainland subregions of South-West, South-East, North-West and North-East Friesland (). Tourism plays an increasingly important role in the regional economy (Jeuring, Citation2015). These subunits aside, the province remains our primary spatial unit of analysis, as Friesland as a whole embodies key meaningful sociocultural aspects of identity (Betten, Citation2013). At the same time, it is an important territorial unit in the context of the Dutch nation-state (Duijvendak, Citation2008; Haartsen, Groote, & Huigen, Citation2000).

Sample and procedure

Residents of the Province of Friesland registered as respondents with Partoer, a socioeconomic research organization, were invited to fill out an online survey. A convenience sampling approach was used, as registration with the panel and participation in this specific survey were voluntary. While this could result in overrepresentation of people intrinsically motivated to fill out this survey, or to communicate their opinion on regional issues more generally, we deemed the convenience sample suitable for our conceptual analysis of relations between destination attractiveness, proximity preferences and proximity tourism behavior. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted keeping in mind the limitations of this approach.

A total of 913 usable surveys (71 percent response rate) were collected. Some 49 percent of the sample was men, 51 percent was women. Most respondents were older ages, with more than half being 50 years or older and 12 percent being younger than age 40. Some 67 percent of the respondents were married, 23 percent had never been married and 10 percent was divorced or widowed.

The survey provided items for comparing the relative attractiveness of destinations within the province (the intraregional level) and for comparing Friesland with elsewhere in the Netherlands and abroad (the interregional level). The interregional options involved greater physical distance between home and away, thus implying a greater need for mobility and travel. Respondents were asked to allocate 100 points among three interregional options, with higher numbers of points indicating a stronger preference for that destination. Four patterns of attributing points were discerned. In line with these, we categorized respondents into four groups reflecting particular preferences of geographical proximity between home and vacation destination. This resulted in four proximity preference groups: (1) proximate, preferring to spend a vacation relatively close to home; (2) distant, preferring to spend a vacation relatively far from home; (3) intermediate, preferring to spend a vacation relatively close to home, but not too close; (4) mixed, preferring a variety with some vacations far away and some close to home. presents details on group categorization.

Table 1. Conditions for grouping respondents based on relative preference for proximity of vacation destinations.

We used our categorization into the proximity preference groups to compare respondents’ touristic attitudes toward and touristic behaviors in their province of residence. Moreover, a number of sociodemographic indicators were measured, allowing us to construct basic socioeconomic profiles of the proximity preference groups. Attitudinal items explored respondents’ perceptions of the touristic attractiveness of Friesland as destination for themselves (‘What is your overall image of Friesland as tourism destination?’) and for the five subregions (respondents were asked to allocate 100 points among the subregions indicating their relative attractiveness as a tourism destination). Next to self-oriented attitudes, their sense of the province's attractiveness to others as a destination was also measured. This was done at the provincial level (‘Friesland is an attractive destination for its residents/for people from other parts of the Netherlands/for people from abroad’) and for the five subregions (‘To what extent would you recommend each subregion to family and friends as an attractive destination to spend a vacation?’). Normative attitudes to proximity tourism were measured in terms of perceived benefits of engaging in proximity tourism (e.g. ‘When I visit touristic attractions in Friesland, I am supporting the local economy’).

Intraregional tourist behavior pertained to overnight stays and other recreational behavior within the province. For the former, the survey asked, for example, ‘In the last five years, have you spent a main vacation in Friesland?’ For the latter, a list of Friesland's most popular touristic attractions was presented on which respondents were asked to check off those they had visited (see Appendix A). Future intraregional vacation intentions were measured using one item: ‘Do you plan to spend a main vacation in Friesland within the coming two years?’ Answer categories were ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘maybe.’

This item was followed by an open-ended question prompting respondents to provide motives for their intention. Answers varied from short phrases to full sentences. Based on the stepwise procedure outlined by Boeije (Citation2009), our analysis of these responses involved several rounds of reading, rereading and coding, to arrive at the abstract level of categories. The coding rounds focused first primarily on identifying references to four motivational drivers of mobility (or immobility) (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012): push and pull factors to travel outside Friesland (instead of choosing a vacation within the province) and keep and repel factors for staying close to home (i.e. prefer a vacation in Friesland or prefer to stay at home). See also . The second step in the coding rounds was to analyze representations of distance and proximity in the responses, according to the four typologies suggested by Larsen and Guiver (Citation2013) (distance as a resource, as an experience, as an ordinal aspect and in a zonal sense). Our analysis, however, extended the application of these categories by applying them not only to distance but also to representations of proximity. The statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23) was used for the quantitative analyses and Atlas.ti was used to code the qualitative responses.

Results

This section has two parts. The first presents our quantitative analysis of preferences for and attitudes toward proximity tourism across the four proximity preference groups. These findings provide insight into the sociodemographic characteristics, perceived attractiveness of Friesland as tourism destination for self and for others, perceptions of social benefits from engaging in proximity tourism in Friesland and past and future intraregional touristic behavior. The second part reports on our qualitative analysis of motivations for preferences to spend a vacation near home (or spending it far away). These findings center on the different representations of distance and proximity used by the four proximity preference groups, as well as the types of distance and proximity typically used in motivations for either staying close to home or traveling afar.

Preferences for and attitudes toward proximity tourism

Sociodemographic indicators of preference groups

We used chi-square tests to compare the groups regarding gender, income, household type and age (). The proximate preference group contained more lower income households, older respondents and people with low to medium education levels. The distant preference group typically had higher household incomes and higher education levels. Also, this group contained relatively few people in the oldest age category. The group with intermediate preferences resembled the proximate group, except that it contained relatively more medium to high household incomes, a larger share of people in the 31–50 age category and a lower share of those in the 51–65 age category. Finally, people in the mixed group had high household incomes and often higher education levels. Age patterns were similar to the distant preference group, although the youngest and oldest groups were slightly better represented here. No significant results were obtained when distinguishing between gender and between household types (not reported in ).

Table 2. Income, age and education level per preference group.

Perceived attractiveness for self

Regarding overall destination image, while on average respondents were rather positive about Friesland as a tourism destination (M = 7.90, SD = 1.28), significant differences were found between the preference groups. Most positive by far were people in the proximate preference group, while those in the distant preference group had a much less positive overall image of Friesland (). This suggests that preferences for proximity and distance played an important role in destination image formation.

Table 3. Overall destination image and intraregional vacation preferences: mean score differences between preference groups.

However, this overall image was blurred at the intraregional level, comparing the five subregions (the Wadden Islands and North-West, South-West, South-East and North-East Friesland) (). Respondents appeared to agree overall that the Wadden Islands was the most attractive subregion, followed by the South-West (lake area) and the South-East (wooded area). North-West and North-East Friesland trailed behind at a distance. Interestingly, each of the different preference groups tended to favor a specific subregion. South-West Friesland was most appreciated by the mixed and proximate preference groups. North-East Friesland was most popular among the proximate preference group. Similarly, though not substantiated by significant p-values, the Wadden Islands tended to be the favorite among the distant preference group, while South-East Friesland was relatively more appreciated by those with intermediate preferences.

Perceived attractiveness to others

While destination image and attractiveness often rest on personal preferences, another telling indicator is the expectation that (similar) others would appreciate a particular destination. Two measures were addressed in this regard. First, respondents were asked to what extent Friesland overall was an attractive tourism destination for three different groups: residents of the province, residents of the Netherlands and visitors from abroad. The second measure focused on the Frisian subregions, asking respondents how strongly they would recommend a particular subregion to family and friends as a possible destination for their vacation.

All groups considered Friesland more attractive as a destination for Dutch and foreign tourists than for tourists residing in the province (). However, the preference groups differed significantly in their perceptions of the province's attractiveness to tourists from within Friesland. The proximate group was very positive, while the intermediate and, particularly, the distant preference groups were much less so. People in the mixed preference group fell between these opposites. The ambivalent appreciation they expressed of both nearby and distant destinations thus appeared to carry over to their expectations of Friesland's attractiveness to others.

Table 4. Perceived destination attractiveness for potential visitor groups, recommended subregions of Friesland, perceived benefits of proximity tourism: mean score differences between preference groups.

In line with people's preferences among the subregions for their own vacations, the Wadden Islands and South-West Friesland were highest recommended (). So, people appeared to recommend to others what they liked themselves. Yet, recommendation scores varied significantly between the preference groups (except for those preferring the South-West). The less ‘popular’ regions (North-West and North-East), in particular, were relatively unlikely to be recommended by the distant preference group. Also, the South-East was recommended relatively highly by the intermediate preference group, and less so by the distant and mixed preference groups. Finally, the Wadden Islands was less highly recommended by the intermediate preference group.

Perceived benefits of proximity tourism

Benefits of Frisian residents spending time and money through tourism within their home province included three aspects: economic benefits, the value of increasing personal knowledge about one's everyday living environment and improved social cohesion within the province. Responses on benefit statements thus reflect normative attitudes toward proximity tourism, to the extent that it is seen as a social responsibility to support and explore ‘the homeland.’

Supporting the regional economy and increasing regional knowledge were considered overall potential benefits of proximity tourism. However, people in the intermediate preference group were significantly less convinced of the potential benefits for the regional economy, than those in the proximate preference group (). Preference groups also differed significantly in their views on whether increased social cohesion could result from spending time as tourist within Friesland. While the mixed group and, particularly, the proximate group saw this as a potential benefit, those in the intermediate and distant groups had a neutral stance.

Behavioral aspects of proximity tourism

Respondents were asked whether they had spent a main vacation in Friesland during the past five years, and also if they had spent other vacations (i.e. outside of their main vacation) in the province. Vacation intention was measured by asking people whether they planned to spend a main vacation within Friesland in the coming two years.

Chi-square tests () provided insight into past and future intraregional tourist behavior and intentions among the four preference groups. It became clear that preferences for proximity or distance in tourism destinations were strongly related to both previous destination choice and intention. Over two-thirds of people in the proximate preference group had indeed spent at least one main vacation within the province. Many respondents in both the distant and intermediate groups had not spent a vacation near home. For vacations other than main vacations the relationship was weaker. Interestingly, the distant and mixed preference groups spent other vacations (next to or instead of their main vacation) within the province relatively often. This could indicate that people in these groups were financially more advantaged, but also that they had more control over the way they took and spent leisure time. In terms of intraregional vacation intentions, the pattern was more or less similar to the previous main vacation choice. Particularly interesting here was the relatively small proportion of people in the intermediate group who intended to spend their main vacation within the province. This group, together with the mixed preference group contained the largest number of respondents who were still unsure whether they would spend a main vacation in Friesland ().

Table 5. Vacation history and intention per preference group.

In addition to overnight stays, respondents were asked about daytrips to touristic attractions in Friesland. Overall, respondents expressed only moderate agreement with the statement, ‘I visit touristic attractions in Friesland on a regular basis’ (M = 3.54, SD = 1.03). However, significant differences were found between preference groups (F(909,3) = 4.93, p = 0.002). The mixed (M = 3.70, SD = 0.95) and proximate preference groups (M = 3.74, SD = 1.05) indicated visiting near-home attractions significantly more often than those who preferred more distant vacation destinations (M = 3.46, SD = 1.04).

Furthermore, the survey provided respondents a list of major regional touristic attractions (based on a list from Tripadvisor.com, see Appendix A). They were asked to check off the attractions they had visited at least once. On average, respondents had visited over half of the 22 listed attractions (M = 12.36, SD = 4.21). However, those in the mixed preference group (M = 13.03, SD = 3.67) had visited significantly more attractions than people in the intermediate group (M = 11.59, SD = 4.07; F(909,3) = 2.87, p = 0.04), while the differences found between the other groups were not significant.

Motivations for proximity tourism

We now turn to our qualitative analysis of the representations of proximity and distance identified in the statements respondents gave to explain their intention to engage (or not to engage) in proximity tourism. We categorized motivations in terms of push and pull factors for travel across greater distances (i.e. prefer to spend a vacation outside of Friesland) and keep and repel factors for stays in the proximity of home (i.e. prefer a vacation within Friesland). The motivations were categorized according to the ways that notions of distance or proximity were conveyed (distance as a resource, as an experience, as an ordinal aspect and in a zonal sense). Combining these two categorizations provided in-depth insight on the link between ideas about distance/proximity and motivations underlying destination choices. First, a number of overall findings are outlined, after which the results are discussed per preference group. To compare the types of qualitative responses given by respondents in the different preference groups, categorizations obtained in Atlas.ti were imported into the SPPS file.

Overall findings

In the motivations expressed for intraregional vacation intentions, 220 references to distance and 311 references to proximity were categorized according to type of motive and type of distance/proximity (). Three key findings emerged, pertaining to all four preference groups. First, distance was primarily used in terms of experiences. Such experiences included the spatial qualities found when away from home (e.g. weather, mountains), encounters with different cultures or a more general sense of otherness. Second, proximity was primarily used in terms of resources. For example, respondents emphasized the convenience of near-home destinations or the short travel times involved. Thus, distance and proximity seemed to serve different purposes in the motivations expressed. Third, temporal aspects reflecting either proximity or distance were often used, seemingly allowing for flexibility in the way people engaged with spatial proximity and distance. These frequently provided room for adaptation and variation throughout the year or life course. For example, temporal flexibility allowed people to alternate between short trips near home and longer vacations farther away. Similarly, being in a certain life phase (young or old, with or without children) was mentioned as a reason for traveling to distant destinations or staying near home, either now or in the future.

Table 6. Typical representations of distance and proximity in motivations for (not) planning a vacation in Friesland, per preference group.

Temporal distance was also reflected in the motivations expressed by people who did not know yet for sure if they would be spending a vacation near home; the moment to decide where to go on vacation had not yet arrived. Obviously, these general results were found to various degrees within the four preference groups. Variation was particularly evident in the extent that motivations reflected push, pull, keep and repel factors. The sections below discuss per preference group the distinct ways that proximity and distance were represented by each.

Proximate preference group's motivations

Given their preference for proximity, it is no surprise that most people in this group intended to spend a main vacation near home. In explaining this preference, proximity was used exclusively as a keep factor, underlining the perceived positive qualities of proximity. These included proximity as a resource, particularly the short travel time due to the destination being ‘close to home,’ or in terms of accessibility, as traveling was ‘not easy’ with young children or in reference to respondents’ being less mobile or ill. Furthermore, various instances of proximity as experience were found. Importantly, people acknowledged opportunities for encountering otherness nearby, stating for example, that in Friesland there were ‘many things still to discover’ and expressing interest in ‘getting to know the province better.’

People used ordinal aspects of distance too, stating that the weather was ‘better than at home’ or ‘sunnier compared to the rest of the Netherlands,’ particularly when speaking of the Wadden Islands. The weather, thus, was an important comparative aspect, even on such a small geographical scale. Similar sentiments were found in the use of distance as keep factor: while being close to home, people expressed a sense of ‘being far away,’ ‘in another world.’ These ways of talking about proximity and distance substantiate a decoupling of experiential distance from physical separation between home and away. Furthermore, some used distance as a repel factor in terms of travel time, with ‘making long trips’ cast in unattractive terms. Finally, some respondents had no intention of spending a vacation in Friesland or anywhere else, as they stated they ‘never go on vacation.’ They used distance as a keep factor, positioning themselves away from touristic activities altogether.

Distant preference group's motivations

In contrast to the proximate preference group, the distant group typically used proximity in reference to push factors. This became particularly clear when proximity was understood as a resource, for example, stating that proximate touristic attractions were easily accessible (perhaps too easily) and could be visited either ‘throughout the rest of the year’ or ‘at some other point in the future.’ Proximity as experience was also employed as a push factor in terms of familiarity, with people indicating, for example, ‘knowing the province already.’ Many respondents noted they ‘already live’ in Friesland, implying that a spatial distinction between Friesland and their vacation destination was a self-evident, logical reality: home is here, therefore, my vacation will be anywhere but here. Choosing to spend a vacation in Friesland would contradict the idea of being on vacation. Importantly, proximate spatial qualities associated with Friesland were another strong push factor. This pertained to the weather, in particular, which was described as ‘too unpredictable,’ ‘lacking sunshine’ and ‘too cold.’

However, not everybody expressed such strong links between the familiar, accessible home and their preference for distant vacation destinations. Some stated that, because they lived in Friesland, a sense of being on vacation was available and proximate to them throughout the year. Therefore they did not ‘feel the need to go on a vacation,’ thus using experiential proximity as a keep factor. Finally, financial resources were a keep factor for people with distant preferences, forcing them to stay (near) home. Proximity tourism thus became an alternative when destinations far away were also financially distant, a reasoning found particularly among people who were still unsure about their vacation plans.

Distance was often referred to in this group, primarily in the context of pull factors. Not surprisingly, people preferring distance were attracted to distant places, but indeed often because those places were associated with experiential otherness. Strong associations were found between physical distance and relative, experiential distance. These were reflected in references to ordinal aspects or to distance in a zonal sense. For example, main vacations were associated with ‘getting away,’ ‘going abroad’ and ‘traveling afar,’ without necessarily specifying where and why. When people did specify, they noted spatial qualities, such as a mountainous environment, but the weather -again- featured prominently as well. Distant places were cast as different because they were ‘sunny and warm’ or provided a ‘stable climate,’ compared to Friesland. Distance as experience was reflected in a desire to ‘encounter other cultures’ or ‘discover new places,’ hereby exemplifying the conventional ideas of the mundane home and the exotic away.

Intermediate preference group's motivations

Few in the intermediate preference group intended to spend their vacation in Friesland, although a substantial share was still unsure. People in this group used distance more or less similarly to those with a preference for distance. As a pull factor, distance was associated with attractive differences to be experienced in other places than near home. Proximity appeared to be a strong push factor among this group. People were motivated to ‘get away from the daily routine.’ Temporal aspects were relatively little used in motivations for destination preferences. However, this group, most of all, described their main vacation as an opportunity to escape. At the same time, a relatively large proportion appeared to be financially constrained, which limited their vacation options, associated with expressions of proximity as a resource in terms of keep factors. However, an intermediate preference for distance also brought an interest in otherness nearby. Thus, some similarities were found between this group and the proximate preference group, as the discovery of new places near home was mentioned as attractive keep factor (although only by people unsure of their vacation plans). Importantly, keep motivations in this group referred to social proximity in a number of instances, that is, appreciation of having family and friends nearby.

Mixed preference group's motivations

In the group with mixed preferences, proximity was used in a little less than two-third of the instances, while just over one-third pertained to distance. Vacation intentions varied widely in this group, and expressions of proximity and distance were therefore rather varied as well. The ways this group used distance aligned with those of the distant and intermediate preference groups. At the same time, this group used proximity somewhat similarly to the group preferring proximity. Thus, this group appeared to appreciate the best of both. Proximity was used to convey keep factors: appreciation of the opportunity to experience difference near home. Accessibility was considered an opportunity, for the future and to rediscover their familiar environment in new ways.

Nonetheless, everyday familiarity remained a push factor for a main vacation abroad. Also, this group appeared to be flexible in allocating time, as they tended to differentiate between near-home daytrips throughout the year and main vacations abroad. The relatively large group that was still unsure expressed proximity as a keep factor in terms of ‘short travel time,’ possibly increasing the likelihood of spending a vacation near home. However, indecision was also motivated by decision moments still being in the distant future.

Conclusion and discussion

Our study sought insight on people's appreciation of their region of residence as a tourism destination. We employed an online survey administered to a convenience sample of residents of Friesland, The Netherlands (N = 913). Our explicit interest was the role played by perceptions of proximity and distance in determining the attractiveness of vacation destinations and touristic behavior near home. We discerned four preference groups regarding proximity of vacation destinations: (1) proximate, (2) distant, (3) intermediate and (4) mixed. These groups were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, perceptions of the attractiveness of vacation destinations within the home region and intraregional touristic behavior (RQ1). We also analyzed respondents’ motivations for engaging (or not engaging) in proximity tourism (RQ2).

Based on the preference group profiles a number of key characteristics were discerned. Respondents indicating a preference for a proximate vacation typically had lower sociodemographic status and higher age. They also had a positive image of their home province as tourism destination and considered Friesland an attractive destination not only for incoming tourists, but also for people living in Friesland. This was expressed in positive attitudes toward the benefits of proximity tourism, and a higher number of past and intended main vacations spent within the home region. Proximate preferences were motivated by representations of proximity as a convenient resource and by expressions of distance as an experience of otherness that could also be found near home.

In contrast, people indicating a preference for distant destinations were relatively younger, had higher household incomes and higher education levels. Having less positive perceptions of their home region as a tourism destination, they differentiated between the attractiveness of Friesland to incoming tourists and its unattractiveness to residents of Friesland. Potential local benefits resulting from intraregional tourism were little recognized, and this group hardly participated in intraregional touristic activities. This group expressed its preference for distance in terms of being pushed away, associating proximity with familiarity and bad weather. Respondents indicated being pulled toward distant places, for specific experiences of cultural or environmental otherness or for less specific ordinal aspects or distance in a zonal sense, to just escape and get away from it all.

These two profiles were mediated by people in the intermediate and mixed preference groups. The sociodemographic profile of the intermediate preference group was similar to that of the proximate preference group. These both, moreover, somewhat paralleled the distant preference group regarding perceived benefits of near-home tourism, a lower overall image of the home province as a tourism destination and ways of using distance in destination preference motivations. Yet, the intermediate preference group was unique in its appreciation of South-East Friesland, its lower engagement in intraregional tourism between main vacations and its use of social proximity as a keep factor for spending a main vacation in Friesland. On the other hand, the mixed preference group was somewhat similar to the proximate preference group in participation in intraregional tourism, while its sociodemographic profile matched that of the distant preference group. Expressions of distance by the mixed group were similar to those in the group preferring distant destinations, while proximity was expressed in terms similar to the proximity preference group. Finally, the mixed preference group distinguished itself in both appreciating and visiting proximate and distant destinations. Thus, the four group profiles – representing varying preferences for proximity and distance – were associated in a nonlinear way with appreciation of the home region as a tourism destination.

Overall we can conclude that preferences for proximity and distance formed a useful basis for studying attitudes towards proximity tourism. Our study has contributed to a better understanding of the often neglected perspective of residents as tourists in their home environment. Based on these findings, a number of themes can be highlighted for better understanding the mechanisms people use to negotiate between home and away.

First, the complex and varied perceptions among residents of the tourism potential of their home region represents a challenge to scholars and tourism stakeholders. Indeed, perceptual and behavioral barriers may inhibit appreciation of otherness and differences found near home, as these are often hidden under a surface of familiarity. We found this to be particularly true among people who strongly associated geographical distance with their vacation needs. Yet, a too-overt focus on otherness could neglect the significance of familiarity in tourism. We found familiar and comfortable social environments to be important to many proximity tourists in Friesland, in line with findings on camping tourists elsewhere (Blichfeldt, Citation2004; Collins & Kearns, Citation2010; Mikkelsen & Cohen, Citation2015) and second-home tourists (Müller, Citation2006). Thus, tourism policy should be sensitive to the importance of mundane activities in tourism, doing nothing as a way to ‘vacate’ (Blichfeldt & Mikkelsen, Citation2013) and the often strong attachments tourists develop to the destinations they visit. Similarly, travel is still a luxury for some, and limited temporal and financial resources might translate into mobility constraints, often related to personal and life-course circumstances (e.g. couples with young children, older people with small pension incomes and physical limitations imposed by old age). Access to geographically proximate tourism resources will therefore remain an important consideration across all sociodemographic groups, and local residents should be a key target group in developing regional tourism, as well as in policymaking regarding citizen wellbeing. Similarly, a disproportionate focus among policymakers and tourism marketing organizations on relatively rich, incoming tourists risks stimulating social divisions and resident opposition to regional tourism, as it arguably may make places less attractive to the people residing nearby. A less rigid distinction between residents and tourists – though this is a persistent dichotomy in both tourism research and tourism policy (Jeuring, Citation2015) – is therefore encouraged.

A second contribution of this study is to advance understanding of representations of proximity and distance in motivations and preferences for tourism destinations. Our results confirm the conceptual usefulness of the keep and repel factors (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012), in addition to the conventional push and pull factors, for understanding the motivations underlying tourism mobility. Indeed, the different roles of proximity and distance in the four motivation types confirm the importance of relative comparisons in destination choices. Choosing among destinations is an interactive comparative process in which attractiveness and unattractiveness are relative. The factors viewed as attractive and unattractive depend on people's personal preferences, embedded in place and time. Our respondents used different representations of proximity and distance as relative anchor points for positioning themselves with regard to their vacation preferences.

An example of such comparison is the way our respondents used the weather and climate in their reasoning. Distant destinations were represented as having stable and warm weather, while bad, unpredictable weather was associated with proximity, home and the everyday. Other studies have found weather conditions at the destination to significantly impact the tourist experience (Jeuring & Peters, Citation2013) and destination image (Becken & Wilson, Citation2013). Among our respondents, too, comparisons between home and away often appeared to be based on perceptions of the weather. Given the temperate, variable climate of Friesland, which is typical of North-West Europe, future research could further scrutinize how the weather affects (potential) proximity tourists in this region. Locals might, if the weather is nice, choose to remain in the region instead of, or in addition to, conventional (mass) tourism farther away.

Moreover, the role of proximity and distance in vacation motivations is not entirely spatial. We found the use of distance and proximity as push, pull, keep and repel factors was embedded in a temporal context, diminishing the often polarizing influence of spatial distinctions between home and away. What people find attractive or unattractive, familiar or unfamiliar varies over time, both in the short term of an annual vacation escape and in the longer term of the overall life course. In our study, this was exemplified by the distinction respondents made between their main vacations and the opportunity to explore places near home during the rest of the year. The need to escape the everyday could also be understood as an opportunity to balance associations of unattractive familiarity nearby with attractive unfamiliarity far away (Spierings & van der Velde, Citation2012). In this light, tourism destinations might focus less on their competitive identity (Anholt, Citation2007) and more on a complementary identity. To this end, we suggest increased attention for temporal dynamics in tourism research on destination choice and tourist behavior.

Third, our findings support the existence of the attitude-behavior gap identified in other studies (Hibbert, Dickinson, Gössling, & Curtin, Citation2013): despite a positive attitude toward Friesland as a touristic destination, vacationing was associated with physical distance between home and destination, and people tended to formulate both their preferences and their destination choices accordingly. Positive attitudes thus were frequently not translated into actual intraregional touristic behavior. This remains an important topic for tourism research, particularly as large carbon footprints are increasingly criticized and transport costs are expected to rise significantly. Proximity tourism as an alternative might then reflect behavioral responsibility for both the local and the global environment (Gren & Huijbens, Citation2015).

Fourth, proximity tourism could offer an opportunity for tourism marketing, destination branding and regional development as a whole, to redefine the target audience of touristic attractiveness and how tourism contributes to the wellbeing of residents. Social and normative aspects of identity are particularly influential here (Hibbert et al., Citation2013), as traveling abroad enjoys a status of affluence. Nevertheless, increasing initiatives illustrate a revaluation of the local and familiar in the context of near-home touristic experiences, thus renegotiating the discourse of home and away and decoupling geographical distance from experienced otherness. An excellent example in this regard is the provision of guided city tours aimed at local residents (Díaz Soria & Llurdés Coit, Citation2013; Rabotić, Citation2008). Some regional tourism marketing organizations have acknowledged the value of proximity. For example, in early 2016, the Dutch Province of Flevoland introduced an ‘Adventurous Nearby’ campaign to raise awareness among residents of the touristic value of their home surroundings.

Finally, while Hibbert et al. (Citation2013) proposed opportunities for ‘counter-identities’ to overcome the constraints of environmentally sustainable travel, the same logic could be applied to traveling closer to home, for example, building on the notion of a rediscovery of the self through tourism. Presenting familiar places from a new angle enables people to reconstruct their own identities and those of the places they inhabit. Furthermore, framing proximity tourism as a type of citizenship behavior might encourage people to spend vacations near home, to engage with everyday environments in different ways and to develop regional pride and awareness. Eventually, such awareness could induce regional ambassadorship activities, such as word-of-mouth behavior. A good example in this regard is Melbourne, Australia, with its ‘Discover Your Own Backyard’ campaign. Another is the recent resident-focused marketing campaign of the Belgian Province of Limburg, building on the idea that locally committed citizens should explore their home region. We expect the momentum of this dynamic to increase in the coming years and hope this study provides input for further innovative tourism development, aimed at raising awareness and appreciation of familiar, near-home environments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and Dirk Strijker for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. This work is part of the research programme of University Campus Fryslân (UCF), which is financed by the Province of Fryslân.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jelmer Hendrik Gerard Jeuring

Jelmer Hendrik Gerard Jeuring is a Ph.D. researcher at the Cultural Geography Department of the Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. His research focuses on tourism and socio-spatial identities in the Dutch province of Fryslân. Particularly, in his Ph.D. research aspects of ‘proximity tourism’ are explored, where people engage in touristic activities nearby of within their places of residence. Jelmer has an MSc in social psychology and an MSc in leisure, tourism and environment. He has previously published also on topics around the role of weather and climate in tourism.

Tialda Haartsen

Tialda Haartsen is an assistant professor in Cultural Geography, at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences of the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. Her research focuses on the consequences of population decline in rural areas, but she has a special interest in how rural and regional images influence the spatial choice behavior of internal migrants and tourists.

References

- Alexander, A. C., Lee, K. H., & Kim, D.-Y. (2011). Determinants of visitor's overnight stay in local food festivals: An exploration of staycation concept and its relation to the origin of visitors. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Graduate Education & Graduate Student Conference in Hospitality & Tourism, Houston, TX.

- Anholt, S. (2007). Competitive identity: The new brand management for nations, cities and regions. Journal of Brand Management, 14(6), 474–475.

- Becken, S., & Hay, J. (2007). Tourism and climate change: Risks and opportunities. Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Becken, S., & Wilson, J. (2013). The impacts of weather on tourist travel. Tourism Geographies, 15(4), 620–639. doi:10.1080/14616688.2012.762541

- Betten, E. (2013). De Fries. Op zoek naar de Friese identiteit. Leeuwarden: Wijdemeer.

- Blichfeldt, B. S. (2004). Why do some Tourists choose to spend their Vacation Close to home. Esbjerg: Syddansk Universitet.

- Blichfeldt, B. S., & Mikkelsen, M. V. (2013). Vacability and sociability as touristic attraction. Tourist Studies, 13(3), 235–250. doi:10.1177/1468797613498160

- Boeije, H. (2009). Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Canavan, B. (2013). The extent and role of domestic tourism in a small island: The case of the Isle of Man. Journal of Travel Research, 52(3), 340–352.

- Celata, F. (2007). Geographic marginality, transport accessibility and tourism development. In A. Celant (Ed.), Global tourism and regional competitiveness (pp. 37–46). Bologna: Patron.

- Cohen, E. (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13(2), 179–201. doi:10.1177/003803857901300203

- Cole, S. (2007). Beyond authenticity and commodification. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 943–960.

- Collins, D., & Kearns, R. (2010). ‘Pulling up the Tent Pegs?’ The significance and changing status of coastal campgrounds in New Zealand. Tourism Geographies, 12(1), 53–76. doi:10.1080/14616680903493647

- Dubois, G., Peeters, P., Ceron, J. P., & Gössling, S. (2011). The future tourism mobility of the world population: Emission growth versus climate policy. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 45(10), 1031–1042. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2009.11.004

- Duijvendak, M. (2008). Ligamenten van de staat? Over regionale identiteit en de taaiheid van de provincie. BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review, 123(3), 342–353.

- Díaz Soria, I., & Llurdés Coit, J. (2013). Thoughts about proximity tourism as a strategy for local development. Cuadernos de Turismo, 32, 65–88.

- Edensor, T. (2007). Mundane mobilities, performances and spaces of tourism. Social & Cultural Geography, 8(2), 199–215.

- Feagan, R. (2007). The place of food: Mapping out the ‘local'in local food systems. Progress in Human Geography, 31(1), 23–42.

- Franklin, A., & Crang, M. (2001). The trouble with tourism and travel theory. Tourist Studies, 1(1), 5–22.

- Gren, M., & Huijbens, E. H. (2015). Tourism and the Anthropocene. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Haartsen, T., Groote, P., & Huigen, P. P. (2000). Claiming rural identities: Dynamics, contexts, policies. Assen: Uitgeverij Van Gorcum.

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Degrowing Tourism: Décroissance, Sustainable Consumption and Steady-State Tourism. Anatolia, 20(1), 46–61. doi:10.1080/13032917.2009.10518894

- Haven-Tang, C., & Jones, E. (2005). Using local food and drink to differentiate tourism destinations through a sense of place. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology, 4(4), 69–86.

- Hibbert, J. F., Dickinson, J. E., Gössling, S., & Curtin, S. (2013). Identity and tourism mobility: An exploration of the attitude–behaviour gap. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(7), 999–1016.

- Jeuring, J. H. G. (2015). Discursive contradictions in regional tourism marketing strategies: The case of Fryslân, The Netherlands. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. Advance online publication. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.06.002

- Jeuring, J. H. G., & Peters, K. B. M. (2013). The influence of the weather on tourist experiences: Analysing travel blog narratives. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19(3), 209–219.

- Kastenholz, E. (2010). ‘Cultural proximity’ as a determinant of destination image. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 16(4), 313–322. doi:10.1177/1356766710380883

- Kavaratzis, M., & Ashworth, G. J. (2007). Partners in coffeeshops, canals and commerce: Marketing the city of Amsterdam. Cities, 24(1), 16–25.

- Larsen, G. R. (2015). Distant at your leisure: Consuming distance as a leisure experience. In S. Gammon & S. Elkington (Eds.), Landscapes of leisure: Space, place and identities (pp. 192–201). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Larsen, G. R., & Guiver, J. W. (2013). Understanding tourists’ perceptions of distance: A key to reducing the environmental impacts of tourism mobility. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(7), 968–981.

- Marjavaara, R. (2008). Second home tourism: The root to displacement in Sweden? (PhD thesis). Umeå University, Umeå.

- Mikkelsen, M. V., & Cohen, S. A. (2015). Freedom in mundane mobilities: Caravanning in Denmark. Tourism Geographies, 17(5), 663–681. doi:10.1080/14616688.2015.1084528.

- Mottiar, Z., & Quinn, B. (2003). Shaping leisure/tourism places-the role of holiday home owners: A case study of Courtown, Co. Wexford, Ireland. Leisure Studies, 22(2), 109–127.

- Müller, D. K. (2006). The attractiveness of second home areas in Sweden: A quantitative analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(4–5), 335–350.

- Müller, D. K. (2011). The internationalization of rural municipalities: Norwegian Second Home Owners in Northern Bohuslän, Sweden. Tourism Planning & Development, 8(4), 433–445.

- Neuts, B., & Nijkamp, P. (2012). Tourist crowding perception and acceptability in cities: An applied modelling study on Bruges. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(4), 2133–2153.

- Olwig, K. R. (2005). Liminality, seasonality and landscape. Landscape Research, 30(2), 259–271. doi:10.1080/01426390500044473

- Pearce, P. L. (2012). The experience of visiting home and familiar places. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 1024–1047. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.11.018

- Peeters, P., & Dubois, G. (2010). Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 447–457. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.09.003

- Pike, S., & Page, S. J. (2014). Destination marketing organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202–227. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.09.009

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2010). The relationship between the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors of a tourist destination: The role of nationality – an analytical qualitative research approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(2), 121–143.

- Rabotić, B. (2008). Tourist guides as cultural heritage interpreters: Belgrade experience with municipality-sponsored guided walks for local residents. Paper presented at the International Tourism Conference, Alanya: Cultural & Event Tourism.

- Ren, C., & Blichfeldt, B. S. (2011). One clear image? Challenging simplicity in place branding. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(4), 416–434.

- Rijnks, R. H., & Strijker, D. (2013). Spatial effects on the image and identity of a rural area. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36(0), 103–111.

- Ryan, C. (2002). Tourism and cultural proximity: Examples from New Zealand. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 952–971.

- Salazar, N. B. (2012). Tourism imaginaries: A conceptual approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 863–882.

- Singh, S., & Krakover, S. (2015). Homeland entitlement: Perspectives of Israeli domestic tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 54(2), 222–233.

- Spierings, B., & Van Der Velde, M. (2008). Shopping, borders and unfamiliarity: Consumer mobility in Europe. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 99(4), 497–505.

- Spierings, B., & van der Velde, M. (2012). Cross-border differences and unfamiliarity: Shopping mobility in the Dutch-German Rhine-Waal Euroregion. European Planning Studies, 21(1), 5–23.

- Szytniewski, B., & Spierings, B. (2014). Encounters with otherness: Implications of (Un) familiarity for daily life in borderlands. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 29(3), 339–351.

- UNWTO. (2008). World tourism barometer 2008 (Vol. 6). Madrid: Author.

- Warnaby, G., & Medway, D. (2013). What about the ‘place’ in place marketing? Marketing Theory, 13(3), 345–363. doi:10.1177/1470593113492992

- Wildish, B., Kearns, R., & Collins, D. (2016). At home away from home: Visitor accommodation and place attachment. Annals of Leisure Research, 19(1), 117–133. doi:10.1080/11745398.2015.1037324

Appendix A.

Popular tourist attractions and activitities in Friesland