ABSTRACT

This paper examines an unusual type of ‘cultural theme park’, one that is not based on simulating existing cultural diversity or historical places, but based in some senses on a ‘double simulation’. The theme park is based on an historical painting assumed to represent the North Song Dynasty period in Kaifeng, China; however, it is a representation that historians argue may never have existed. Utilising on-site interviews and participant observation, this paper traces the connections between the classic painting (清明上河图) and the actual historical landscape of Bianjing (the first simulation), and in so doing, unravels the links between the painting and the theme park (the second simulation) and the simulacra that are envisioned to form within the spaces of the theme park as a result of the interplay of simulations during theme park visits. The simulations and intended simulacra are ‘consumed’ to various degrees, suggesting that the representations of Kaifeng's historical past and culture have been impactful and (in)authenticity has not been an issue. Moreover, the theme park has served to entertain and, in some cases, inspire through playful appropriations of Kaifeng's past and culture. The resultant simulacra and its double simulations (in simulating both the real Bianjing and the neo-real landscape painting) contrast and simultaneously connect with rampant replications of the Occident in contemporary Chinese residential landscapes, townships and themed spaces.

摘要

本文探讨了一种特殊类型的文化主题公园。这种文化主题公园并不是建立在模仿现有多元文化或者历史场所的基础上, 而是建立在二元模仿的基础上 (既模仿清明上河图画作, 又模仿真实的汴京景观) 。该主题公园以历史名画⟪清明上河图⟫为蓝本, 该画作被认为是再现了位于中国开封的北宋王朝。但是, 这种对北宋王朝的再现, 历史学家认为, 可能从来就没有存在过。本文利用现场访谈与参与观察追踪了经典的⟪清明上河图⟫与汴京真实历史景观 (第一次模仿) 的联系, 揭示了画作、主题公园以及模仿物之间的联系。模仿物是游客游览主题公园期间由于不同模仿的相互作用而在主题公园空间范围内想象而成的。这些模仿以及人为的模仿物不同程度上被“消费”, 这表明, 开封的历史与文化受到了影响。历史的 (非) 真实还尚未形成一个议题。另外, 通过对开封历史与文化的戏谑性利用, 主题公园起到一种娱乐和激发灵感的的作用。最后, 本文比较了并且把主题公园衍生的模仿物及其二次模仿与当前中国对西方住宅景观、城镇和主题空间猖獗的模仿关联起来。

Introduction

Since the opening of Disneyland in 1955 in California, theme park consumption has become a favourite mode of mass entertainment in modern society (Clavé, Citation2007; Formica & Olsen, Citation1998; Milman, Citation1991; Milman, Citation2001; Park, Reisigner, & Park, Citation2009). Besides the role as a space for leisure, the historical foundation and the workings of the theme park as a cultural creation should not be underestimated. Borrowing words from Clavé (Citation2007, p. 5), there is at present, ‘a whole world of theme parks beyond Disney’. Cultural theme parks, a type of tourist attraction that paints a holistic picture of regional culture or represents a specific historical event (Hofstaedter, Citation2008; Yeoh & Teo, Citation1996), commonly facilitate cultural promotion, strengthen the cultural interest of visitors and stimulate place image redefinition (Clavé, Citation2007; Moscardo & Pearce, Citation1986). Many authors globally have argued that the rise of these types of theme parks were meant to foster national identity and create ready-made sites for foreign visitors to experience the diversity of a particular country (Hitchcock, Citation1998; Muzaini, Citation2016). In this paper, we want to explore an unusual type of ‘cultural theme park’, one that is not based on simulating existing cultural diversity or historical places, but rather one that, in some senses, represents a ‘double simulation’. The theme park is based on an historical painting, assumed to represent the North Song Dynasty period in Kaifeng, China; however, it is a representation that historians argue may never have existed. Although the theme park is said to represent the painting, it also represents notions of North Song history that are disseminated through popular culture (television and Martial Arts Chivalry or wuxia-genre novels).

A long history underpins themed leisure spaces in China. These begin in the form of cultural gardens and courtyards of painstakingly manicured botanical species (Ren, Citation2007). Originally monopolies of Chinese emperors, imperial gardens replicating foreign and sovereign lands were a means of projecting power and authority (Bosker, Citation2013, p. 31). The emperor's monopoly of themed spaces was broken in the Six Dynasties period (220–589 CE) when a new type of garden – the natural garden – was created. Situated in the residences of high-ranking officials, wealthy traders and landowners and the Chinese literati, these scaled-down replications of the natural landscape (for example, using rocks or hills to symbolise legendary peaks) defined a sophisticated lifestyle of the Chinese elite (Bosker, Citation2013, p. 33). The early focus on replicating, miniaturising and ‘owning’ natural flora, fauna and the logics of their spatial arrangements (as configured in a ‘landscape’) shifted to an obsession in the mimicry of architecture and townscapes from Europe and North America (Bosker, Citation2013). Apartments, condominiums and even entire townships borrowed and copied defining elements from the Occident, giving rise to the emergence of residential townships such as the Swedish-themed Luodian Town in Shanghai and Scenic England in Kunshan (Bosker, Citation2013). Alongside such a themed residential area development was the rise of theme parks (or zhuti gongyuan re) based on the replication and miniaturising of the world for the then travel visa-challenged Chinese citizenry of the late 1990s (Oakes, Citation1998, p. 50). As the Chinese middle-class were denied easy entry into many of the world's top attractions, late 1990s Chinese theme parks shrunk the world and placed them at the doorsteps of China's rising middle-class urbanites in the country's richest cities: Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. Alongside such mainstream developments, a compendium of niche and idiosyncratic theme parks exists as well, reflecting unique circumstances or peculiar interests of their owners or builders. For example, Shenzhen's Minsk World is a military theme park atop a decommissioned Soviet aircraft carrier; its wine bottle-shaped buildings, Wuliangye Yibin's (China's biggest rice wine maker) factory and visitor centre can be described as an ‘Alice in Alcoholic Wonderland theme park’. Cultural theme parks reproducing China's past in general and theme parks deriving from a three-dimensional (3D) realisation and manifestation of ‘flat’ iconic paintings have been a smaller and less-studied phenomenon.

The painting, known as ‘The Riverscape on Qingming Festival’ (清明上河图hereafter, ‘the painting’) which we discuss in this paper, depicts Bianjing, the historical centre of the Middle Kingdom's seat of power, culture and commerce during the North Song Dynasty, the historical site of which is located in what is today the prefecture of Kaifeng. Housed in the Beijing Palace Museum, it is widely regarded as one of the great masterpieces of Song painting. Constructed as a handscroll measuring 25.5 centimetres in height and 5.25 metres in length on silk and painted in light ink, it is an intricate figure painting and outstanding portrait of a city, marked by an enchanting landscape (Johnson, Citation1996). Bianjing is also the historical setting for stories about the North Song magistrate, Bao Zheng or more commonly known as Baogong who was a Chinese official during the reign of Emperor Renzong in the Song Dynasty. Bao had demonstrated extreme honesty and courage during his twenty-five years of civil service and was respected in China as a symbol of justice. His remarkable exploits included sentencing his own uncle and punishing powerful families. These incidents were subsequently recreated and retold in a variety of literary and dramatic mediums including wuxia (martial arts chivalry) found in genre novels, television series, films and traditional Chinese operas. They were also retold through the cultural theme park examined in this paper.

In writing this paper, we draw on participant observation and on-site interviews to trace the connections between the painting and popular everyday notions of North Song Dynasty culture and history as they are understood through the cultural and historical theme park, the Qingming Riverside Landscape Garden (清明上河园) inspired by the painting in the Kaifeng Prefecture. We examine the ways in which these simulations and signs are received and consumed by Chinese visitors and the implications of these processes for understanding simulation and theming in contemporary Chinese society. Conceptually, we draw on postmodern ideas of simulation and replication and relate and contextualise these within Chinese philosophical approaches to understanding copy and mimicry. Specifically, we build on Bosker's (Citation2013) understandings of simulation, simulacra and simulacrascapes in the fast-emerging themed residential landscapes in contemporary China. To Bosker (Citation2013), these themed landscapes serve as simulated perfections of reality (landscapes as simulacra or simulacrascapes) and are products of idealisations of nature and culture which aim not at forming accurate replications of reality but at creating landscapes that are desired by both the people constructing them and the people perceived to be consumers of such landscapes. The simulacra are better than real as exemplified in the desired architectural features of England in Kunshan's Scenic England augmented by modern comforts of air-conditioning, Chinese language road signs and other Chinese customisation. We argue here that Kaifeng's North Song Dynasty theme park is a historically displaced simulacra and an intended hyper-reality for the consumption of contemporary Chinese visitors – one which has appropriated the past for contemporary leisure and has playfully displaced and customised the past for modern Chinese tourists. In this sense, it is a perfect and perfected cultural space which contrasts and connects with China's architectural mimicry in her residential landscapes. While there is an appropriation and customisation of Occidental (chiefly Western European and North American) landscape elements to cater to Chinese upper–middle-class taste, here it comprises a selective revival of a Chinese dynastic past for common Chinese leisure and amusement.

We also argue that there is not one but two levels of simulation or ‘double simulation’ happening in this cultural theme park: first, the simulation of the actual riverscape in the iconic historical painting, and second, the simulation and manifestation of the painted landscape on the grounds of the theme park in modern day Kaifeng. There has not been a consensus academically with regards to the extent the painting accurately depicts and replicates the riverscape of Bianjing and the authenticity of the dating of the painting (that is, the actual date on which it was painted and hence its level of datedness and historicity). Nevertheless the painting was found to be accepted and enjoyed by visitors during their tour of the cultural theme park. The simulation of the landscape depicted in the ‘flat’ painting into real 3D space was also found to have gone unchallenged by Chinese visitors. Popular cultural elements from wuxia and TV were also integrated into the process. The customisation that was undertaken to allow the space to function as a tourist, amusement and leisure space through the setting up of visitor facilities and the generous use of popular cultural elements were found to be not only non-intrusive but also were appreciated for the ways in which they improved and perfected the cultural space and the visitor experience.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we discuss existing conceptualisations and debates concerning cultural theme parks, hyper-reality, simulacrum and simulation. Following that, we outline and discuss our methodological approach. In the first discussion section, we examine and discuss the first simulation – from reality to painting – and the debates over its authenticity. The following section discusses the second simulation from painting to theme park and the ways in which visitors engage with the theme park. The third section discusses how the two simulations interplay in visitor performances and how such double simulations perfect a cultural tourism space for visitors. We conclude by reflecting on these ideas in relation to theme park developments and themed spaces in contemporary China.

Cultural theme parks, hyper-reality, simulacrum and simulation

The concept of authenticity is a well-researched one in tourism research in general (see for example, McCannell, Citation1973; Bruner, Citation2001) and in China tourism research in particular (see for example, Wang, Citation1997; Xie & Wall, Citation2002). McCannell (Citation1973) and Bruner (Citation2001) had given the tourism academia a structural analysis of how authenticity can be performed spatially – via a front- and a back-stage and how authenticity functioned in more multiple cultural reproductions, respectively. Such insights had travelled into research in China tourism. For instance, research on the link between authenticity and tourism in China have yielded useful insights concerning visitors' understandings and experiences of landscapes of calligraphy (Zhou, Zhang, & Edelheim, Citation2013), visitors' evaluations of the (in)authenticity of Hainan Island attractions (Xie & Wall, Citation2002), a traditional ritual practitioner's reflections of the authenticity of his embodied performance in a Naxi Wedding Courtyard in Lijiang, China (Zhu, Citation2012) and how Beijing's traditional vernacular architecture can help satisfy tourists' greater demands for authenticity (Wang, Citation1997). While these strands of research have helped shed light on the importance of cultural forms and the ways these are produced and reproduced and lend weight to arguments for the conservation of historic objects and traditional rituals and forms, these authenticity-based research tended to suggest a duality of experiences comprising of a deep authentic experience and a superficial and inauthentic one. Key postmodernist thinkers have argued against oversimplification of realities via such dualistic framings and pointed to the rewards of engaging with the complexities, multiplicities and fluidities in the worlds of cultural reproductions. In the case of China, the work of Ryan and Gu (Citation2010) demonstrated the relevance of multiple and fluid interpretations of authenticity and culture in visitor experiences.

From a postmodern perspective, a theme park, like the contemporary world it is situated in, is viewed as replete with hyper-real objects, symbols and spaces (Edvardsson, Enquist, & Johnston, Citation2005; Steiner, Citation2010; Venkatesh, Citation1999). Hyper-reality can be understood as the phenomenon in which the artefact appears to be more real than the real thing (Berthon & Katsikeas, Citation1998). Studies associated with hyper-reality have echoed theories initiated by Eco (Citation1986) and Baudrillard (Citation1994, p. 2007). Using the journey to art museums in America for analysis, Eco (Citation1986, p. 8) illustrated instances of how experiences of the ‘real’ can be achieved through the imagination and enjoyment attained from what he calls ‘fabricated fakes’. ‘The logical distinction between the Real World and Possible Worlds has been undermined’, as concluded by Eco (Citation1986, p. 14), as the art museums have blurred the boundaries between game and illusion, and historical reality and fantasy. This, Eco explains, is achieved by indulging visitors with ‘fakes’. As explained by Steiner (Citation2010), hyper-realisation in accordance with Eco's ideas, is the situation when a copy becomes more real than its archetype, and arises because the copy presented appeals to people's perception, demand and imagination. For Baudrillard (Citation1994), hyper-reality operates in the forms of simulation and simulacra. In Baudrillard's world of simulation and simulacra, the contradictions between true and false, reality and imaginary, originality and representation are eradicated. The imaginary landscape of Disneyland, according to Baudrillard (Citation1994: 13), is neither true nor false, but provides a fantastic miniature of larger American society. Simulation is ‘the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyper-real’ (Baudrillard Citation1994: 7). Hyper-reality is experienced in the mental processes and everyday life of human beings constructed by imaginations, ingenuities, fantasies and pragmatic needs, including tourist experiences in an artificial cultural park (Baudrillard, Citation2001; Berthon & Katsikeas, Citation1998; Darley, Citation2003; Edvardsson et al., Citation2005; Steiner, Citation2010; Venkatesh, Citation1999).

Specifically within the area of tourism, numerous studies have resonated with the postmodern perspectives of Eco (Citation1986) and Baudrillard (Citation1994, Citation2001). For instance, Pretes (Citation1995) assessed the touristic value of Lapland's Santa Claus in Finland and found it to have enabled tourists' consumption of the intangible concepts of ‘Santa Claus’ and Christmas. Santa Claus is an image without originals; yet the contrived spectacled theme of Santa Claus attracts tourists and successfully advertises Lapland as the hometown of Santa Claus. Using the example of the Australian cultural park, Tjapukai, Edelheim (Citation2010, p. 255) analyses the staged realities of reproduced aboriginal culture presented and consumed in the park and concludes that the hyper-reality of the music, dance and craft performances on show at tourism places are ‘increasingly a part of modern tourism’. Similarly, Steiner (Citation2010) argued that the hyper-realisation of tourism spaces is a trend for future heritage tourism and destination development based on current projects such as the Medinat Hammamet, Burj Al Arab and The Palm Islands in the Middle East and North African countries. In his study of casino landscapes in Macau, Simpson (Citation2009) argued that the themed spaces of Macao casinos, including one based on Greek Mythology, are postmodern products in the age of simulation, which function as indices for movement, experience and consumption. In ecotourism, Reichel, Uriely, and Shani (Citation2008) showed how tourists favoured experiencing a combination of simulated attractions and nature-based sites in Negev Desert and that the artificial simulations are complementary rather than contradictory to nature in a postmodern tourist experience.

Bruner (Citation1994) provides a critique that while these cases and postmodern insights highlight that themed spaces are not superficial non-places, such approaches retain the real versus copy dichotomy and tends to be evaluative. He tries to draw attention to a constructivist paradigm in his review of the work of the postmodernists and argues that culture has always been in circulation. A postmodernist framework examining the relationship between originals and copies and the role of the hyper-real, however, is also relevant to China (Bosker Citation2013). According to Fong (Citation1962, p. 103), the Chinese use discrete terms to differentiate four key forms of forgeries: ‘mu’ (摹), to trace; ‘lin’ (临) to copy; ‘fang’ (仿) to imitate; and ‘tsao’ (造), to invent. Tracing (摹) is about creating an exact replica of the original. In the case of paintings, this includes the exact replication of the use of paper, ink and framing and a duplication of what exactly is depicted. Copying (临) is a looser endeavour compared to tracing and the copier replicates less of what exactly is drawn and more about the techniques and style of the original painter. An imitation (仿) relates more to an adaptation of the original painter's techniques and style and an invention relates to the often decontextualised reproductions of motifs inspired by certain originals. While Bosker's (Citation2013) analysis of contemporary Chinese residential landscape renders it to be the more developed duplication, the case of the theme park of our analysis leans closer to free-handed and looser ‘copying’. Such a genealogy of Chinese copies and simulation lends weight to an adoption of postmodern conceptualisations of duplication and originals.

Methodology

This research is based on qualitative field research conducted by one of the authors of this paper. The field research is organised around the different ways in which visitors make sense of their experiences in the theme park, how they appropriate the painting and its past and how they relate (or not) to the re-appropriations of the past constructed by the management of the theme park. Field research was conducted in the summer of 2014 and began with one of the researchers spending two days walking around and sensing the theme park in order to gain a fundamental knowledge of its ‘place-making practices’ (Pink Citation2009, p. 29). Attention was paid to the architectural elements of the theme park, such as the Rainbow Bridge across the Bian River, Sun Yang Zheng Shop, and the City Gate Wall and the live performances. One of the researchers observed visitors' interactions and their consumption of souvenirs and programmes that charged additional fees, such as the ancient costume-playing and rides on horse-drawn carriages. Particular attention was paid to the ways in which the visitors refer (or not refer) to the painting and elements of the past and other key elements of their experiences including whether they felt they were learning, playing, relaxing, escaping, realising/transforming themselves and/or seeking solidarity or conforming to group norms. This first initial on-site observation served to provide basic knowledge about the theme park and its visitors. Media reports were also accessed to help contextualise the study.

Following that, extended participant observation and narrative interviews to explore the imaginations, perceptions and experiences associated with hyper-reality in the theme park were conducted. Twenty participants of different ages, educational levels and social backgrounds were intentionally selected from one of the authors' known contacts. Such a selection is intended to allow for a higher level of trust between the researcher and the respondent as the credibility of qualitative data collection centres largely on the trust and rapport forged between the researcher and his or her informants (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2006, p. 200). In doing so, we were able to gather a deeper and more intimate understanding of respondent experiences in the theme park. During the participant observation process, the research participants were followed and observed closely on a one-on-one basis so as to examine and record their consumption patterns, conversations, interactions and actions in the different sites and experiential programmes. Building on the trust and rapport already forged, researchers following the research participants closely became a less intrusive endeavour. Familiarity with the participants also allowed for accurate and valid observations of their interpretations of interactions, happenings and encounters during their time spent in the theme park. Fieldnotes were written in an ethnographic way and consisted of details on what was observed, differentiating them from notes on what the fieldworker thought and the broader connections to theory (Wolfinger, Citation2002). To investigate their thoughts and experiences more deeply, an open-ended narrative interview with each participant was conducted after observing and walking with them around the theme park. The open-ended interview started with: can you tell me about your experience in the theme park? Throughout the interview, the participants were asked to elaborate on their experience. The central idea was to allow interviewees to speak freely and openly and to prevent the researcher's preconceived notions from interfering with the data collection process. Data collected were audio-recorded, transcribed and then subjected to thematic analysis (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001). The major themes uncovered were: painting as simulation, double simulation, escape/relaxation/play, theme park as simulation, cultural learning and appreciation. In terms of representation in writing, pseudonyms were used for all the research participants interviewed for this paper.

The painting and the riverscape: simulating historical Bianjing

Here, we consider the varying ways in which the painting has been seen to have simulated landscapes of Bianjing's past. There are two dominant thoughts on the ways in which the painting simulates Bianjing and they vary on the extent to which the painting is an accurate replication and reproduction of reality then and the time period during which the painting was created (Murray, Citation1997).

The first dominant thought highlights the painting as a realistic portrayal of reality. This view emphasises the painting as comprising a historically accurate river and urbanscape depicting ancient Kaifeng (then Bianjing) during the North Song era and the much celebrated Qingming festival. A key supporter of such a view is historical geographer Linda Johnson. Comparing and matching elements observed in the painting against the geographical, hydrological and architectural features of the Northern Song capital, Bianliang, Johnson (Citation1996, p. 100) asserts that the painting was produced during Emperor Song Huizong's reign and that it depicted the Northern Song capital during the Qingming festival of the third lunar month. She concludes that the painting portrays the region in and around Zheng Gate in the west wall of the city, including a suburban area extending to and going beyond Heng Bridge. Yet the painting has been argued more recently to be a figment of the painter, Zhang's imagination (see for example, Hansen Citation1996) and, like Baudrillard's assertion of Disneyland as a fantastic miniature of America, the painting serves to form an idealised generic Chinese city rather than an accurate copy of Bianjing. One key proponent of this argument is Valerie Hansen (Citation1996) who asserts that the scroll was painted in private during the early Southern Song Dynasty. In both views, the authorship is attributed to the Song Dynasty painter, Zhang Zeduan.

Although debates on the painting's exact age and the precise temporal period which the painter, Zhang Zeduan aims to depict have yet to be settled by historians (Hansen, Citation1996; Zhang, Citation2008), the painting has played a key role for visitors in the imagination and understanding of historical Bianjing. For instance, Zhao remarked how the potentially historically unrooted painting simulated via a stone relief at the entrance () facilitated his enjoyment of the theme park:

The painting formulated my first impression of ancient Kaifeng … The big relief of the painting near the entrance and the narration of the tour guide aroused my interest in the elements of the painting … To me, the painting is an interesting and comprehensive Bianjing condensed into a painting scroll. (Zhao, male, 22, student majoring in art design)

Indeed for Zhao, the painting was experienced as an ‘interesting’ and ‘comprehensive’ depiction of Bianjing. Although the academic debates have yet to be reconciled, visitors to the theme park appeared convinced during the fieldwork that the painting depicts and simulates a real Bianjing. It also appears that the painting has become iconic to the extent that replicating it on its own is a worthy endeavour because whether or not it is a reproduction of an actual historical landscape and the exact time period in which it was painted would and will not be of importance to visitors.

The theme park and the painting: simulating the painting

Contemporary Kaifeng is a prefecture-level city administrated by Henan Province, China with a population of approximately five million urban residents. Previously one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of 600,000 to 700,000 during China's North Song Dynasty in eleventh century, modern-day Kaifeng does not rank amongst the top cities in China in the country's contemporary ranking of its urban centres. One of the Nine Ancient Capitals of China alongside Xi'an, Luoyang, Nanjing, Beijing, Hangzhou, Anyang, Zhengzhou, Datong, Kaifeng's tourism industry today relies on culturally themed spaces reconstructed from readings and interpretations of historical and other sources as much as historical buildings that are no longer in existence.

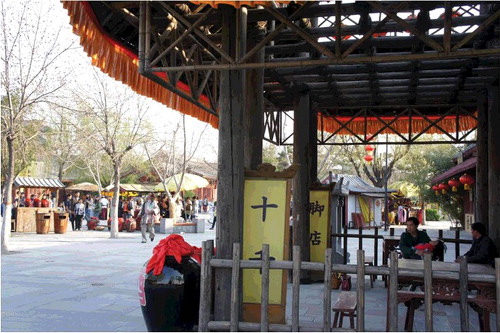

Opening in 1998, the ‘Millennium City Park’ as it is known locally, is a 400,000 square-metre theme park actualising and materialising what was believed to be lively, prosperous scenes of Kaifeng during China's North Song Dynasty when the city peaked in its importance. Folk-custom cultures and legendary tales of the North Song Dynasty packaged and presented to the visitor illustrate the ability of the painting and the theme park to transport visitors back a thousand years and into ancient Bianjing (一朝步入画卷, 一日梦回千年). Live action performances such as Chinese martial arts' feats (ying qigong, 硬气功), the Legendary Patriotic General Yuefei Slaying Traitor Chaigui (岳飞枪挑小梁王) and interactive experiential programmes such as the Marriage of Landlord Wang's Daughter (王员外家招亲) are integrated into the ancient North Song Dynasty-style architectural elements of the theme park. A 3D movie show and a large-scale on-water performance have orientated and introduced visitors to the legendary painting and the colourful history of the North Song Dynasty.

As a successful and effective copy and simulation, the prosperous Bianjing projected and simulated in the painting, has arguably become important on its own. The narratives have revealed that the inner contents and aesthetic values of the painting have preceded the history of Kaifeng in its significance for visitors. In the words of Song:

I knew from the tourist brochure that this theme park is reproduced from the painting. I took a panoramic picture to compare it with what I see in the painting. (Song, female, 49, teacher)

Song's narrative pointed to the use of the painting as a model for reality. Yet, if indeed, the painting is the product of its creator's imagination rather than a historically-referenced piece of work – a simulation, then Song's referencing of her tourist photography is an interesting act in furthering the simulation and duplication of the painting. Such further reproductions can be found in avid embroidery hobbyist, Li's desires to copy embroidered versions of the painting () for a purpose unrelated to appreciating or preserving Bianjing's cultures and heritage:

When I heard the name of the park, I was interested to visit. I'm an embroidery fan, and I wanted to stitch the painting for quite a long time, but that procedure is too complex, I gave up too many times. I expected this visit could provide me with new inspiration to continue striving for a self-embroidered version of the painting. I am not disappointed; see these I bought from the souvenir shops. Bianxiu is an amazing traditional product, I can learn from this product to improve my embroidery skills. I want to practise carefully on these Bianxiu, and hopefully my own embroideries will look nicer as gifts. (Li, female, 52, tax officer)

Reproduced and stitched Bianjing souvenirs based on the painting, like reconstructed models in museums, helped focus Li's leisure and tourism experience within the park. The same could be said about Tong who enjoyed the costume-play she got to indulge in and which she felt helped transport her, not into North Song Bianjing, but into the painting itself:

This trip was nice, but I expect it could be better. I experienced ancient Kaifeng in the park, dressing in ancient style suit, sitting in the horse-drawn carriage, I came to know what life of the Bianjing people in the North Song Dynasty was like. All the workers in the park wear North Song-style costumes and the architectures in the park were reproduced from ancient Bianjing. I was quite pleased to see that I could have an authentic North Song experience there. I'm really satisfied with the service of costume renting … wearing the costumes, I could forget myself as a modern person. And when I walked around dressing up like that, I felt like I'm a part of the painting. I bought the sugar figurine and sugar painting, but I was actually not interested in eating them. I watched some TV series before and remembered that the sugar figurine was a part of ancient life, and so I pretended to be an ancient character experiencing ancient street life. I took the horse-drawn carriage, just to experience, but otherwise I would have preferred to walk and explore this park on my own pace, on foot. (Tong, female, 25, government clerk)

Last but not least, the painting has also fomented not one but two theme parks (the other being Song Cheng in Hangzhou). The idealised prosperous riverscape of North Song popularised by the painting has rarely been scrutinised for historical accuracy by the theme park's visitors. In this sense, the idealised and ‘improved’ landscapes and the role they play in the visitor experience relates to hyper-real and better-than-real experiences reported elsewhere (see for example, Baudrillard Citation2001; Berthon & Katsikeas, Citation1998; Darley, Citation2003; Edvardsson et al., Citation2005; Steiner, Citation2010; Venkatesh, Citation1999). Moreover, the painting became a reference point for how the ‘real’ North Song Bianjing should look. Responding to the promotional theme, ‘Engaging with the painting brings back scenes of a 1000 years’ (一朝步入画卷, 一日梦回千年), the attractions in the theme park, from the facilities to the workers, and from the still architectures to the live action shows, are decorated in North Song styles in reference to the painting to display what was seen as unique in Bianjing culture. Notwithstanding the commercial profit annually obtained, the success of the theme park is also arguably based on the extent to which its theme is accepted by its visitors (Ryan & Collins, Citation2008).

Participant observation and the narrative interviews conducted revealed the various ways in which the simulated ancient Kaifeng are consumed, negotiated and resisted. While acknowledging subtle differences, Jiang pointed to the generally high quality of the reproduction from the painting to the theme park:

There are some differences between the theme park and the original contents of the painting, but the typical part of the painting can be found in the park. (Jiang, female, 32, government clerk)

By ‘typical parts’, Jiang referred to the key elements in the painting that were easy to remember and identify, such as the Hongqiao (虹桥) Bridge across Bian River (汴河, the centre of the painting), Sun Yang Zheng Shop (孙杨正店, a shop depicted in a painting that produces and sells wine), Sun Yang Jiao Shop (孙杨脚店, a shop painted in painting that only sells but does not produce wine) () and the city gate wall. These architectural elements in the theme park, as the material ramification of the painting, have projected the grand and peaceful scenes of Bianjing to the visitor and such reproductions have, as the previous visitor narratives have shown, played an important and positive role in the theme park experience.

The inter-play between the two simulations: appropriating ancient Kaifeng as play

In this section, we discuss the ways in which the painting and the theme park are aligned in the playful appropriation of the past in visitors' recreation and how this alignment and appropriation were performed through the arsenal of recreated architectures, period costume-plays and various cultural and ‘action’ shows. We describe and discuss how such North Song fantasies were built on the dreamy foundations of Chinese folklores, legends and nationally produced television series and how such experiences with the theme park as a fantastic landscape have prompted heritage tourism motivations in some of the participants interviewed.

Visitors to the painting-inspired theme park were often open to the idea of learning about the past of a place via a simulated site. For instance, Wang takes a more evaluative approach to the theme park's perceived levels of authenticity. Yet, while acknowledging his critical attitude towards contrived sites, Wang proceeded to reveal how the theme park still provides ‘an impression’ of the historical city:

I am not quite interested in visiting an artificial site … but this theme park does provide me with an overview of Kaifeng city's ancient past. (Yan, female, 46, teacher)

Thus, one can argue that visitors sharing Yan's attitude to and interpretations of the theme park were not too concerned with grounding the authenticity of the site on a single proven historically-accurate moment but instead appeared open to making sense of ancient Bianjing through simulated themed spaces that make efforts at referencing and citing the past. Sometimes, such citing and referencing of the past may indeed be drawn from a rather different trajectory and source – Chinese popular culture and television. While some visitors and tourists at other cultural attractions may draw on different and even contrasting layers of the past as appealing reference points (Ong, Minca, & Felder, Citation2015), Han's reference point lies in the legendary hero of Chinese folklore, Bao Gong (包公), whose exploits have been serialised in decades of Chinese television:

As soon as I heard the name Kaifeng, Bao Qing Tian in Kaifeng came to my mind … the Bao Gong impersonator here was not professional, but still the performance reminded me of life in Kaifeng. I felt I must go to see the real site. (Han, male, 22, student, majoring in Technology)

Reputed as the most incorruptible government officer over centuries, Bao Gong's (or Bao Qing Tian's包青天) name and his legendary stories have been irreplaceable and have become the most renowned elements in Kaifeng history. Bao Gong was not included or visible in painting; however, since the narrative stringing the painting and its elements together were commonly regarded as the typical streetscape of Bianjing, the adoption of the folkloric character of Bao Gong was seen to be compatible with the theme of the site.

Mentioned earlier, Tong who rented a period costume and wore it all the way through the trip found her satisfaction in costume playing. Moreover, the ride in the horse-drawn carriage was derived from her feeling of being involved in the painting and ancient lifestyle which the theme park facilitated. She co-created the experience combining reality, self-performance and imagination. Her experience of ancient Kaifeng bears little resemblance to any authentic presentation of originals, but instead closely bonds to her own perception of being in existence amongst the symbolic ancient elements. ‘Artificiality’ does not equate to ‘fake’ at this point since the logical distinction between historical truths and fantastic spectaculars created from legendary tales was blurred through their indulgence in the themed attractions. In her self-created world, the simulated sites were accepted as projections of the North Song Dynasty since they are the objects matching her perception and imagination.

Such an appreciation of costumed performances and the ambience of the theme park were echoed by Han:

I was a bit dreamy at that time. I was wearing a Song suit, walking on the street and encountering jugglers, the sugar making man, the shops, and suddenly the war broke out … I would not have such a vivid feeling and experience even by watching the scene on TV, or through a visit of a Song artefact-laden museum. (Han, male, 22, student, majoring in Technology)

Han attended the large-scale performance, the Great Song Dynasty-Reminiscences of the Eastern Capital (大宋东京梦华), a night-time performance staged on a lake. The visitor expressed his preference for watching this performance more than visiting scattered museums and heritage sites in Kaifeng. Integrating contents of the painting, inherited folk customs of Kaifeng and renowned stories and Song poetries, this performance produced a convincing and enjoyable performance – a credible projection where the performed Kaifeng appealed to the temporal framings and sense-making of the theme park on behalf of the visitors and the show's audiences. Owing to the fact that the original architectures from the North Song Dynasty had already been ruined and buried over centuries, it was perceived by the participants to be reasonable to view attractions in the theme park as simulations, citing and referencing a distant past. The theme park is thus not an imitation of the painting, but an encapsulation of the desirable qualities of an idealised and projected Kaifeng culture that uses an array of modern-day pyrotechnics and LED illumination during the night performance.

The experience in the theme park was also related to a broader sense of escape and leisure for some of the participants. In the words of Liang, who knows ‘nothing’ about the theme of the park:

Not a bad trip, I tried new things outside my normal life. It was my first horse-drawn carriage experience and it was an experience I would not have in my everyday life as a police officer … I knew nothing about the theme, about the painting or Kaifeng so the guiding and the narration from the driver of the carriage was most useful. I was delighted at escaping from my mundane routine and to leave my duties and obligations behind. Besides the horse-drawn carriage, I also enjoyed the archery, ancient football and boat ride activities even though these were not unique to this theme park and that I had tried them elsewhere. (Liang, male, 49, policeman)

For Liang, visiting the theme park was leisure par excellence as he got to get away from the routine of his job as a police officer to engage in playful or relaxing acts of horse carriage rides, listening to the tales of the carriage driver, watching the live costumed performances, playing ‘ancient football’ and archery and taking the boat rides in the artificial canals.

Post-visit thoughts and the narratives which emerged after leaving the theme parks centred on two dominant aspects: ‘refreshing new knowledge’ and ‘investigating Kaifeng’. The self-expressed experiences indicated that themed attractions might facilitate tourist motivations for seeking more about the ‘reality’ of Kaifeng. First, visitors found the information they gathered from their visit to the theme park to be ‘refreshing new knowledge’:

Unlike now, life in ancient Kaifeng must have been affluent, fair and peaceful. Qingmingshanghetu is a magnificent painting depicting the whole scene of Bianjing, not just palace life in my previous knowledge … I deepened my understanding about what Zhang Zeduan (the artist) painted. For me, the painting is no longer a boring object I tried to learn about, memorise and recite in an exam … I listened to the tour guide and now I can tell stories about the painting and the North Song Dynasty to my child. (Wang, female, 49, business owner)

As a theme park representing historic time periods that visitors might not be all that aware of, knowledge obtained during the visit is an enduring achievement for the visitors (see also Reichel et al. (Citation2008) and Ryan & Collins (Citation2008) for accounts of how postmodern tourism experiences can complement knowledge acquisition). While travelling, new refreshing knowledge can be acquired by visiting, participating and consuming activities in the theme park. A visit to the theme park also motivated further travels. For instance, Tong, Zhao, Yan and Song revealed that:

I will spend more days in Kaifeng to explore its history and customs. (Tong, female, 25 government clerk)

I will return to Kaifeng in the near future. (Zhao, male, 22, student)

I got more curious about heritage sites in Kaifeng and I want to visit other cultural sites in Kaifeng city. (Yan, female, 46, teacher)

I will go to the newly opened Xiao Song City to taste traditional Kaifeng food and watch more folk-custom shows there. (Song, female, 49, teacher)

The wish to investigate and to get to know the city the theme park is based on is amongst the post-trip themes foregrounded. Perceiving scenes and programmes in the park as an aggregation of traditional Kaifeng culture, visitors have expressed their post-visit intention for exploring Kaifeng by visiting other tourist sites, purchasing souvenirs and tasting local foods (see Ong & du Cros, Citation2012 for a case of how while exhibits at World Expositions are ‘unreal’, they nonetheless motivate travels to the places they simulated). The simulated attractions have unlocked the curiosities of visitors on Kaifeng culture by identifying the city's past to the visitors. At this stage, the theme park engenders a double commodification through the visitations; while the tourists purchase for entrance, experiential programmes and souvenirs in the theme park, the place image of Kaifeng is also consumed. The experiences in the theme park have facilitated the visitors' enduring mental processes of rethinking and reaffirming the local history and culture, including the traditional customs, arts, literature and lifestyles of ancient and modern residents, as well as the economic upswings and downturns of the North Song Dynasty.

As a consequence, new tourism attractions in Kaifeng, such as the Ancient Kaifeng Government (the reproduction of Bao Gong's Court and workplace开封府) and the Xiao Song City (newly opened at the end of 2013, which mainly sells traditional Kaifeng food小宋城) emerged to cater to visitors' plans. The common stereotypes and the media-shaped portrayal of the city as a place full of poor and uneducated people and rife with crime and served by an outmoded transportation system would have suggested that such motivations to visit the city would be unlikely had the participants not visited the theme park (Kong, du Cros, & Ong, Citation2015; Ong & du Cros, Citation2012).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined the coming together of idealised historical images from an iconic historical painting and popular everyday notions of Chinese North Song Dynasty history in the contemporary leisure consumption of Chinese visitors in a culture- and history-based theme park in Kaifeng Prefecture in China. We have also uncovered the ways in which Chinese visitors engage with and understand culture as it is simulated in various ways in the park through an investigation of how these simulations and signs are received by Chinese visitors.

Specifically, we argue that a double simulation occurred in the case of the theme park. In terms of the production of space, the first simulation occurred when the painting simulated the actual landscapes of North Song Dynasty Bianjing. The second simulation occurred when the theme park studied simulated the riverscape painted. We have sought, in this paper, to uncover the ways in which such double simulation has been consumed and negotiated by visitors. In Baudrillard's (Citation2001, [originally 1983]) language and according to the experience of visitors to the park, this has meant the engagement in a pretence that we have had the real thing twice – first, to have had sightseen the real and actual North Song era Bianjing (implying an ability to time travel to see past cultures) and second, to have had both the landscapes idealised in the painting and the ability to travel into the artistic spaces of the iconic painting. In doing so, we have demonstrated the work and the experience of the theme park – the production and consumption of the themed experience. This is a process that has been engaged in and experienced as a ‘hyper-reality’ where binaries, including what was supposed to be the ‘real’ (the actual spaces of Bianjing) and the ‘neo-real’ (the painting and the popular cultural elements), melt together seamlessly and referentials are playfully used and sometimes ignored (Baudrillard, Citation2001 [originally 1983]).

The historical (in)accuracy of the painting in simulating the real Bianjing riverscape during Qingming Festival, and of the park in constructing and replicating the painting's elements in three dimensions were not a concern in the visitors' experience of the park. Depictions of Bianjing (ancient Kaifeng) and the park's integration of various wuxia (martial arts) genre and television-based popular culture and amusement were found to have been considered authentic and compelling by visitors and some have been motivated to visit the actual contemporary city represented by the theme park (despite often negative media portrayals of that city). The theme park has been found to entertain and in some cases inspire through playful appropriations of Kaifeng's past and culture. To the visitors interviewed, the theme park and painting were taken as ‘real’, much like in Baudrillard's (Citation2001, p. 169) Borges allegorical tale in which a map is so exact in that it replicates the scale of the city and fully constructed in spite of being ruined and later rediscovered as ‘real’ (Baudrillard, Citation2001 [originally 1983], p. 169). This implies a liminal tourism situation where referentials appeared to have melted together or ‘liquidated’ (Baudrillard, Citation2001, p. 170). The consequent simulacra (theme park) and its double simulations (in simulating both the real Bianjing and the neo-real landscape painting) contrast and connect with the rampant replications of the Occident in contemporary Chinese residential landscapes, townships and themed spaces similar to the ever-growing numbers of replica English and Dutch towns, fantasy tea cup-lands and other imaginative every day and tourism spaces.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Maribeth Erb for comments on early versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chin-Ee Ong

Chin-Ee Ong is a cultural geographer who works on the burgeoning and dynamic interface between tourism and urban governance. His work has focused largely on the rapidly growing Chinese and Asian tourist segments and their associated home and destination cities and societies. He was also part of a team that developed and delivered a series of specialist guide programme for World Heritage sites for UNESCO Asia-Pacific between 2006 and 2011.

Ge Jin

Ge Jin is a qualitative research executive at research consultancy firm Ipsos in China. This research was undertaken when Ge was a graduate student in Wageningen University's Masters of Leisure, Tourism and Environment programme. Her research interests focus on cultural and theme park tourism in China and Asia.

References

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405.

- Baudrillard, J. (2001, originally 1983). Simulacra and simulations. In M. Poster ( Ed.), Jean Baudrillard: Selected writings (pp. 169–188). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Baudrillard, J. 1994. Simulacra and simulation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Berthon, P., & Katsikeas, C. (1998). Essai: Weaving postmodernism. Internet Research, 8(2), 149–155.

- Bosker, B. (2013). Original copies: Architectural mimicry in contemporary China. Honolulu and Hong Kong: University of Hawai'i Press and Hong Kong University Press.

- Bruner, E. (1994). Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: A critique of postmodernism. American Anthropologist, 96(2), 397–415.

- Bruner, E. (2001). The Maasai and the Lion King: Authenticity, nationalism, and globalization in African tourism. The American Ethnologist, 28(4), 881–908.

- Clavé, S. A. (2007). The global theme park industry. Wallingford, CT: CABI.

- Darley, A. (2003). Simulating natural history: Walking with dinosaurs as hyper-real edutainment. Science as Culture, 12(2), 227–256.

- Eco, U. (1986). Travels in hyper reality: Essays. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co.

- Edelheim, J. R. (2010). To experience the “real” Australia – A liminal authentic cultural experience. In C. Ryan & M. Aicken ( Eds.), Indigenous tourism (pp. 247–261). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Edvardsson, B., Enquist, B., & Johnston, R. (2005). Co-creating customer value through hyperreality in the prepurchase service experience. Journal of Service Research, 8(2), 149–161.

- Fong, W. (1962). The problem of forgeries in Chinese paintings, part one. Artibus Asiae, 25(2/3), 217–234.

- Formica, S., & Olsen, M. D. (1998). Trends in the amusement park industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 10(7), 297–308.

- Hansen, V. (1996). Mystery of the Qingming scroll and its subject: The case against Kaifeng. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 26, 183–200.

- Hitchcock, M. (1998). Tourism, Taman Mini, and national identity. Indonesia and the Malay World, 26(75), 124–135.

- Hofstaedter, G. (2008). Representing culture in Malaysian cultural theme parks: tensions and contradictions. Anthropological Forum, 18(2), 139–160.

- Johnson, L. (1996). The place of “Qingming Shanghe Tu” in the historical geography of Song Dynasty Dongjing. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 26, 145–182.

- Kong, W. H. F., du Cros, H., & Ong, C. E. (2015). Tourism destination image development: A lesson from Macau. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 1(4), 299–316.

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Sociological Review, 17, 589–603.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (2006). Designing qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Milman, A. (1991). The role of theme parks as a leisure activity for local communities. Journal of Travel Research, 29(3), 11–16.

- Milman, A. (2001). The future of the theme park and attraction industry: A management perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 40(2), 139–147.

- Moscardo, G. M., & Pearce, P. L. (1986). Historic theme parks: An Australian experience in authenticity. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(3), 467–479.

- Murray, J. (1997). Water under a bridge: Further thoughts on the “Qingming” scroll. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 27, 99–107.

- Muzaini, H. (2016). Informal heritage-making at the Sarawak cultural village, East Malaysia. Tourism Geographies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14616688.2016.1160951

- Oakes, T. (1998). Tourism and modernity in China. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ong, C. E., & du Cros, H. (2012). Projecting postcolonial conditions at Shanghai Expo, China: Floppy ears, lofty dreams and Macao's immutable mobiles, China. Urban Studies, 49(13), 2937–2953.

- Ong, C. E., Minca, C., & Felder, M. (2015). The historic hotel as ‘quasi-freedom Machine’: Negotiating utopian visions and dark histories at Amsterdam's Lloyd Hotel and ‘Cultural Embassy’. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 10(2), 167–183.

- Park, K. S., Reisigner, Y., & Park, C. S. (2009). Visitors' motivation for attending theme parks in Orlando, Florida. Event Management, 13, 83–101.

- Pink, S. (2009). Doing sensory ethnography. London: Sage.

- Pretes, M. (1995). Postmodern tourism: The Santa Claus industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 1–15.

- Reichel, A., Uriely, N., & Shani, A. (2008). Ecotourism and simulated attractions: Tourists' attitudes towards integrated sites in a desert area. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(1), 23–41.

- Ren, H. (2007). The landscape of power: Imagineering consumer behavior at China's theme parks. In S. A. Lukas (Ed.), The themed space: Locating culture, nation, and self (pp. 97–112). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Ryan, C., & Gu, H. (2010). Constructionism and culture in research: Understandings of the fourth Buddhist festival, Wutaishan, China. Tourism Management, 31(2), 167–178.

- Ryan, C. and Collins, A. (2008). Entertaining international visitors – the hybrid nature of tourism shows. Tourism Recreation Research, 33(2), 143–149.

- Simpson, T. (2009). Materialist pedagogy: The function of themed environments in post-socialist consumption in Macao. Tourist Studies, 9(1), 60–80.

- Steiner, C. (2010). From heritage to hyper-reality? Tourism destination development in the Middle East between Petra and the Palm. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 8(4), 240–253.

- Venkatesh, A. (1999). Postmodernism perspectives for macromarketing: An inquiry into the global information and sign economy. Journal of Macromarketing, 19(2), 153–169.

- Wang, N. (1997). Vernacular house as an attraction: Illustration from hutong tourism in Beijing. Tourism Management, 18(8), 573–580.

- Wolfinger, N. (2002). On writing fieldnotes: Collection strategies and background expectancies. Qualitative Research, 2(1), 85–95.

- Xie, P. F. & Wall, G. (2002). Visitors' perceptions of authenticity at cultural attractions in Hainan, China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4(5), 353–366.

- Yeoh, B. S., & Teo, P. (1996). From Tiger Balm Gardens to Dragon World: Philanthropy and profit in the making of Singapore's first cultural theme park. Geografiska Annaler. Series B. Human Geography, 27–42.

- Zhang, X. (2008). A summary of the past 20-year studies on the painting Qingmingshanghetu [近二十年清明上河图研究述评]. Journal of Historical Science, 11, 117–124.

- Zhou, Q., Zhang, J. & Edelheim (2013). Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumer-based model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic landscape. Tourism Management, 36, 99–112.

- Zhu, Y. (2012). Performing heritage: Rethinking authenticity in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(3), 1495–1513.