Abstract

Residents of Kampung Prawirotaman, Yogyakarta, Indonesia respond differently to night-time tourist activity. This historic batik kampung was transformed into an international tourist destination, sowing resident discontent over traffic, anti-social behaviour and noise. Conflict with religious values also features in this dynamic. Observations and in-depth interviews with residents, artists, and hotel/café owners in Prawirotaman and surrounding Islamic kampungs differentiated two phases of touristification. From the 1980s through the 1990s, batik factories were turned into lodgings primarily serving backpackers, and global practices co-existed with traditional culture. Prawirotaman became known as Kampung Bule, a neighbourhood for foreign tourists, reflecting optimism that tourism would define its identity. Then three consecutive crises (the 1998 Asian monetary crisis, the 2002 Bali bombing, and the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake) propelled Prawirotaman into the second touristification phase. Welcoming higher-end visitors brought rising prosperity, but residents became unhappy about the noise, traffic, and late-night drinking. This dynamic became more complex as residents of surrounding religious kampungs, Karangkajen and Jogokariyan, added their voices. Forming a mosque alliance, they instigated a massive crack-down on the sale of alcohol in restaurants and cafés during the New Year celebrations of 2018. This response to the impact of tourism in Prawirotaman suggests that the current level of discontent corresponds to the final stage of the ‘Irridex’ model in which the residents have become openly hostile toward tourism.

摘要

印度尼西亚日惹市甘榜(Kampung)普拉维罗塔曼 (Prawirotaman) 的居民对夜间旅游活动的反应不同。这个历史悠久的蜡染地甘榜(Kampong batik)被改造成一个国际旅游目的地, 引发了人们对交通、反社会行为和噪音的不满。与宗教价值观的冲突也是这种动态变化的特点。本文通过对普拉维罗塔曼和周围伊斯兰村落居民、艺术家和酒店/咖啡馆老板的观察和深入采访, 把该地区的旅游化区分了两个阶段。从20世纪80年代到90年代, 蜡染工厂变成了主要为背包客服务的宿营地, 全球惯例与传统文化并存。普拉维罗塔曼后来被称为乡村蓝调, 是一个面向外国游客的社区, 反映出以旅游业定义其身份的乐观态度。接下来的三次危机(1998年的货币危机, 2002年的巴利岛爆炸案和2006年的日惹地震)将普拉威陀曼推向了第二个旅游化阶段。欢迎高端游客带来了日益繁荣的经济, 但当地居民对噪音、交通和深夜的饮酒感到不满。随着周围宗教村落Karangkajen和Jogokariyan的居民加入他们的声音, 这种动态变得更加复杂。他们组成了一个清真寺联盟, 在2018年新年庆祝活动期间, 鼓动大规模打击餐馆和咖啡馆的酒精销售。当地社区对普拉维托曼旅游业影响的反应表明, 目前的不满程度与激怒指数模型的最后阶段相对应, 在这个阶段, 居民已经公开敌视旅游业。

1. Introduction

‘Now you can hear, the noise from that bar, it is starting to jedug-jedug (imitating the sound), and it is only 10:00 pm! This noise could go on until 3:00 in the morning and it is really disturbing.’ Walking in front of his house after an interview, Mr. X, who was born in Kampung Prawirotaman, is complaining about a recently opened bar. This part of Yogyakarta, famed for international tourism, was just declared one of the world’s top 50 coolest neighbourhoods (Manning et al., 2018).

Complaints from residents may reflect a broader discontent with the impact of tourism (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017; Sharpley, Citation2014). Their protests may be sparked by partying and alcohol consumption (Füller & Michel, Citation2014; Pixová & Sládek, Citation2017; Sommer & Helbrecht, Citation2017), anti-social behaviour (Hughes, Citation2018; Rouleau, Citation2017), and over-tourism (Milano et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2019). For example, tensions have risen in Barcelona’s Ciutat Vella between citizens, policy-makers, and visitors concerning intoxication, noise, illegal property rental, and overcrowding in public spaces at night (Rouleau, Citation2017). Despite attempts of policy-makers to encourage balanced night-time activities (balanced as in meeting the needs of visitors and residents) neighbourhood movements still take action against the effects of tourism.

The issue takes on another dimension in an Indonesian setting, because drinking is forbidden in Islam (Michalak & Trocki, Citation2006), the dominant religion. This prohibition plays an important role in the discontent in Kampung Prawirotaman, as reflected in a massive crack-down on the sale of alcohol in cafés and restaurants during January 2018. The story was covered by two Dutch media outlets, NOS and de Volkskrant – the majority of tourists visiting the area are from the Netherlands (BPS, Citation2018) – which suggested that difficulty finding beer in the area could possibly reduce the number of foreign tourists (Maas, Citation2018; Oosterwechel, Citation2018). It is widely suspected that the incident was led by a conservative religious group, not least because the area is bounded by two Islamic kampungs, Karangkajen and Jogokariyan. Religious conservatism has been growing since 2004, following the successful national election campaign of an Islamic party (Mietzner & Muhtadi, Citation2018).

By highlighting voices of different types of residents and by including residents who live in adjacent neighbourhoods, this paper examines different reactions to Prawirotaman’s growing night-time tourism. The perspective is time-sensitive, as we acknowledge that the range of complaints might change. Doxey’s ‘irritation index’ (Irridex) models residents’ attitudes toward tourism (Pavlić & Portolan, Citation2016). Applying the Irridex (Doxey, Citation1975), we argue that discontent has reached the final stage, antagonism: residents have become openly hostile toward tourism.

First, we review the literature on complaints at tourist destinations and then outline our research methods. Next, we describe Yogyakarta’s kampungs, focusing on Prawirotaman. In the results section we treat residents’ complaints; in the concluding section, we deliberate on how these voices might influence the future of Prawirotaman.

2. Global phenomenon, local responses: voices of residents in tourist areas

Tourism has long contributed significantly to employment and economic development (Lee & Chang, Citation2008). At various destinations, however, its impact on communities has induced backlash (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017). Whilst this paper examines a phenomenon new to Yogyakarta, researchers have studied local responses to tourism for some time (Dodds & Butler, Citation2019; Sharpley, Citation2014).

Various motivations for hostility have been identified in the literature: gentrification and touristification (Cheshire et al., Citation2019; Gravari-Barbas & Guinand, Citation2017; Olt et al., Citation2019; Sequera & Nofre, Citation2018); increased traffic (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017; Vianello, Citation2016); higher house prices and displaced residents (Ioannides et al., Citation2019; Mermet, Citation2017; Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018); party and alcohol tourism (Füller & Michel, Citation2014; Pixová & Sládek, Citation2017; Sommer & Helbrecht, Citation2017); anti-social behaviour (Hughes, Citation2018; Rouleau, Citation2017); and over-tourism (Hospers, Citation2019; Milano et al., Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2019). Such issues had a major impact in Berlin, where residents and community groups complained of ‘troublesome’ tourists (Novy, Citation2016).

However, complaints on religious grounds have not been widely analysed (Poria et al., Citation2003). In Muslim communities, some residents fear that tourism could challenge Islamic values and culture (Sanad et al., Citation2010), whilst others see its possible benefits. Such responses have been described in Iran (Zamani-Farahani & Musa, Citation2012) and the Maldives (Shakeela & Weaver, Citation2018). In two small Iranian towns, Muslim residents support tourism, as it has improved their facilities, infrastructure, cultural activities, and quality of life. Currently, tourism there is primarily domestic, and visitors share the residents’ cultural and religious values. However, people in the Maldives reacted very differently. On Fuvahulah Island, which has relatively few visitors, residents viewed tourism as an ‘evil’ from which their community should be insulated, whereas residents of Huraa Island (with more tourism) viewed the ‘evil’ as manageable. These differences were influenced by the levels of tourism to which each community was exposed, as well as by the perceived dictates of conservative Islam practised locally.

Resident response can change over time (Sharpley, Citation2014). One model for understanding its dynamics distinguishes four stages of resident irritation and is aptly named Irridex (Doxey, Citation1975). In the initial ‘euphoric’ stage, tourists are considered valuable and desirable. Then ‘apathy’ sets in and residents tend to ignore their presence. In the third stage, ‘annoyance’, the cultural differences between residents and tourists are highlighted, resulting in discomfort and (growing) hostility. Finally, in the ‘antagonistic’ stage, residents become openly hostile and seek to discourage tourism. Despite critique that the Irridex model is unidirectional (Wall & Mathieson, Citation2006) and thus fails to explain variations amongst residents (Zhang et al., Citation2006), it is widely applied to understand relationships between the evolution of tourism and the voices of residents (Mason & Cheyne, Citation2000; Nunkoo et al., Citation2013; Sirakaya et al., Citation2002).

Two strategies may emerge, the first being local resident action (Bereskin, Citation2016; Nofre et al., Citation2018). ‘Local’ implies that only directly affected inhabitants are involved, as seen in Barcelona, Spain where residents of La Barceloneta raised a giant anti-tourism banner (Nofre et al., Citation2018). The second, networked action, is usually coordinated (Hughes, Citation2018; Novy, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2019). This is seen in Budapest, Hungary where several issues – over-tourism, the Olympics bid, development projects, an unregulated night-time economy – prompted community-based organisation, working through social media, circulating petitions and staging city-wide protests (Smith et al., Citation2019).

Yogyakarta is a good site for research into resident response: Prawirotaman has experienced tourism for decades and various issues have recently emerged. With this paper, we aim to add to the current literature on the subject by offering insight into governance in a predominantly Islamic and non-Western context.

3. Methods

The residents’ voices were studied by observation and in-depth interviews. First, to understand their day- and night-time activities we conducted static, dynamic, and non-participatory observations for three weeks during summer 2018. Static observation covered the general appearance of the kampung, including the lodges and cafés along with the goods and services they offer, whereas dynamic observation concerned evening and night-time ‘vibrancy’. To understand the position of the community, we attended a series of resident meetings in preparation of the five-year plan for the kampung. The first meeting was attended by approximately 25 people from the immediate vicinity; the second and third only by the five representatives appointed during the first meeting to finalise the planning document.

Then we conducted in-depth interviews with three groups (see ). Prawirotaman’s demographic data from 2019 identifies the top three occupations: 21.57% students; 18.85% private workers; and 18.8% unemployed. Less than 5% had an occupation directly related to tourism and over 80% had no relation to tourism. First, we met with seven residents whose work was related to tourism, including guesthouse or travel-agency owners and workers, but also residents who benefit indirectly by renting land or buildings to businesses such as cafés and restaurants. These latter, indirect beneficiaries usually have another occupation – renting as side-income. Second, we met with 13 residents with occupations unrelated to tourism – civil servants, private-sector employees, and artists. To expand access to this group, we talked informally to 10 residents during a celebration of the Islamic New Year (in neighbourhood 26) about their day- and night-time experiences and made notes on their comments about tourism in Prawirotaman. Third, to understand the voices from surrounding kampungs which do not have relations with tourism, we interviewed five residents of Karangkajen and Jogokariyan – kampungs with a strong Islamic identity – and three of Kampung Brontokusuman, adjacent to Prawirotaman. We conducted four interviews with police officers and government officials to broaden our perspective.

Table 1. Interviewed residents.

4. Living in Kampung Prawirotaman

4.1. Kampungs in Yogyakarta: urban neighbourhoods

In Indonesia, an urban kampung is a settlement which defines communities, often with strong social cohesion, and existing within a specific and unique context (Hawkins, Citation1996; Rahmi et al., Citation2001; Setiawan, Citation1998; Sullivan, Citation1986, Citation1992). Raharjo (Citation2010) discusses the difficulties of defining urban kampungs, emphasising their constantly evolving physical and social fabric; Sullivan (Citation1980) describes them as chaotically arranged permanent, semi-permanent, and temporary settlements. (Note that rather than ‘kampong’, the original spelling ‘kampung’ is used here; see: Guinness, Citation2009; Rahmi et al., Citation2001; Sullivan, Citation1980, Citation1992)

A notable characteristic of Indonesian kampungs is their social cohesion, achieved through rukun (social harmony) and gotong-royong (voluntary work; Rahmi et al., Citation2001). Both concepts are manifest in collective activities (Beard & Dasgupta, Citation2006) such as ronda, kerja bakti/gotong-royong, and pitulasan. Ronda is a night-watch patrol starting around 9 or 10 p.m. and finishing around three or four in the morning at a station called a pos kamling (security post). Kerja bakti/gotong-royong operates on a weekly basis, with the community cleaning their neighbourhood. On specific occasions, this voluntary effort can serve a specific goal like construction of a pavement or street. For instance, collective action is a feature of pitulasan, an annual celebration of Indonesian independence on August 17 featuring contests, entertainments, parades, and festivals.

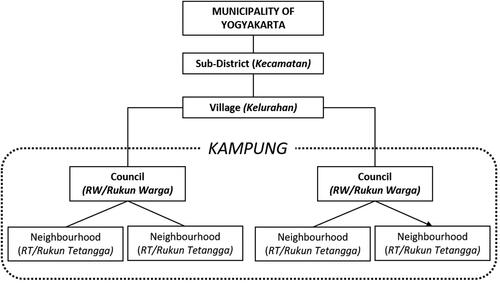

Despite their long history, kampungs have not consistently been recognised by the central government. Having been recognised across multiple periods – from traditional times of Indonesia as a sovereign state to the colonial eras of the Dutch and the Japanese (Geertz, Citation1960) – their status was withdrawn in 1983 when kampungs were re-structured into a larger units named councils (Rukun Warga, RW) and smaller units called neighbourhoods (Rukun Tetangga, RT; Guinness, Citation2009). The distinction between neighbourhood (RT) and council (RW) was established under the regulation of the Ministry of Home Affairs No. 7/1983. However, the regulation was revoked in 1999, after which regulation no. 22/1999 concerning the decentralisation of local governments was implemented.

This administrative change diluted the identity of kampungs in several cities, for example in Jakarta and Surabaya, by making them less cohesive and more individualistic (Nas & Boender, Citation2003; Sihombing, Citation2004). In Yogyakarta, because of its strong culture and identity (Setiawan, Citation1998; Sullivan, Citation1980), the kampung’s spirit of working together persisted, both in terms of the RT and the RW. Since the city’s beginnings in 1755, kampungs were occupied by princes and nobles (45 kampungs), palace servants (38), and palace soldiers (14) (Sumintarsih & Adrianto, Citation2014). Grounded in these strong identities, Yogyakarta’s kampungs developed unique characteristics. Prawirotaman, for instance, traditionally housed palace soldiers and subsequently specialised in batik (artisanal wax-dyed fabric).

Since new regulations were imposed on local autonomy in 1999, several regions in Indonesia have sought to reinstate the status of kampung. In the case of Yogyakarta, Mayoral Decree No. 72/2018 re-recognised kampungs, which now consist of several councils (see ); in total, there are 170 kampungs in the municipality. Furthermore, the mayor obliged each kampung to choose an identifying theme, for example ‘child-friendly’ or ‘tourism-based’.

4.2. From batik to lodging: initial phase of touristification

The settlement of Prawirotaman lies three kilometres south of Yogyakarta’s Kraton Palace. Located at Brontokusuman Village, Mergangsan Sub-District, statistical data for 2018 shows 10,848 inhabitants in the settlement, of which 91.9% are Muslims; 3.7% Christians; 4.1% Catholics; 0.1% Hindus; and 0.2% Buddhists. Initially, the land was given by the sultan to honour Prawiratama soldiers who were part of the sultan’s troops (Kawamura, Citation2004; Khotifah, Citation2013; Sumintarsih & Adrianto, Citation2014). In the 1920s, the kampung became popular as a centre for batik, a traditional Javanese cloth, and by the 1950s there were 38 established brands in the area (Kawamura, Citation2004).

In the 1960s, the artisanal batik industry was in crisis; the central government stopped subsidising the producers and the industry struggled to compete with printed batik (Kawamura, Citation2004; Sumintarsih & Adrianto, Citation2014). Starting in the 1970s, some factories converted their buildings to rent rooms to foreign tourists, mainly backpackers (Prabawa, Citation2010). The three pioneers of this business (the Werdoyoprawiro, Suroporawiro, and Mangunprawiro families; Rusdi, Citation2009) leveraged their industrial contacts to access potential markets abroad. However, tourists were mostly drawn directly from the airport and train stations.

These factory conversions made Prawirotaman popular with international tourists and the area came to be known as Kampung ‘Bule’ (‘white people’). Guesthouses on the main street encroached on the alleys. Other supporting facilities were also established – currency exchanges, tourist agencies, restaurants, and cafés. The term café refers to bars selling alcoholic drinks but also to establishments selling non-alcoholic beverages. These developments were adopted in economic infrastructure growth plans during the 1980s, as well as in Yogyakarta’s vision on tourism and education. Worthy of mention is the first café that sold alcohol in the area: Made Café, established in 1994, is still operating.

I established the business in 1994, but it did not open until 1995 or 1996… At that time, it was still quiet here, but I really enjoyed the situation. Probably because I was still young at that time. But for me, the guests were also enjoyable. Like European guests, they felt like family and usually stayed for more than three days. (Mrs. M, café owner, type 1, interview August 2018)

The development of tourist businesses has induced three changes in Kampung Prawirotaman. Firstly, ronda – the community night-watch patrols – have become less relevant, since the hotels and guesthouses now provide their own security guards, who also secure the surrounding buildings. ‘With the lodges, there must be a night security guard. Minimal, there is a security guard, who is always walking around. We feel the impact of this. Even if there is no community watch, there is a guard’ (Mr. A, type 2, neighbourhood leader, interview August 2018).

Secondly, whilst it was difficult for other kampungs to collect funds for community-related activities (Guinness, Citation2009), it was easier in Prawirotaman – not least because of their willingness to ask for help from the tourism businesses in the area. For example, they collected millions of rupiahs for the annual independence parade of pitulasan: ‘Yesterday, when we had a parade for Indonesian independence, we gathered more than twenty million rupiahs from the hotels and guesthouses. It [the ease of collecting the funds] has happened for decades’ (Mr. F, type 2, neighbourhood leader, interview September 2018). The financial benefits of tourism thus indirectly accrue to the community. These first two changes are considered both positive and negative by the residents. On the one hand, tourism has contributed to safety, mainly at night-time; on the other hand, it has eroded an important collective activity, the community night-watch.

Lastly, throughout this initial period, residents began to acknowledge the existence of foreign tourists and their habits, such as drinking alcohol:

Back when I was in primary school, I already understood what a tourist was. Children in Prawirotaman are familiar with tourists, [especially if] they are foreigners. If we are just silent, they will not react. It has been a habit here. … For them [foreign tourists], beer is just like cola, they do not get drunk with it. (Mr. H, type 2, secretary of the council, interview August 2018)

Some of residents also started to speak English as a third language, alongside Javanese and Indonesian. ‘Many residents could speak fluently in English, because of the tourists’ (Mr. AY, type 2, neighbourhood leader, interview August 2018).

However, Prawirotaman’s shift from a batik- to a tourism-based economy was not mirrored in Karangkajen, an adjacent kampung, where any shift toward tourism was resisted because the residents wanted to keep their identity as a Muslim kampung. During this period, they converted their batik factories into regular houses, although some factories did convert their buildings into boarding houses serving students and workers. ‘If we talk about Karangkajen, we try to preserve its status as a Muslim enclave. That is why, if, in Prawirotaman, the number of hotels has mushroomed, in here, it is different’ (Mr. J, type 3, interview September 2018).

The prosperity brought by tourism suffered three major setbacks from 1998 to 2006 (Prabawa, Citation2010). The first was the global monetary crisis which made Indonesia’s currency significantly weaker. Being dependent on foreign currency, it is unsurprising that lodging businesses struggled through these critical years. Then, just as they were beginning to recover, the second crisis hit – the Bali bombings. Although the incidents occurred in Bali in 2002 and 2004, their negative connotations posed a severe challenge to tourism throughout the region. The third and most critical event was the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake, measuring 5.9 on the Richter scale and causing the collapse of most buildings in Prawirotaman, which lies very near the epicentre. Throughout the period 1998–2005, no new lodges and hotels were built in the area (Rusdi, Citation2009) as the focus shifted toward diversification, for example, opening tourist agencies and souvenir shops (Prabawa, Citation2010).

Apart from those crises, the tourism business has been challenged by inheritance issues (Sumintarsih & Adrianto, Citation2014). The third and fourth generation began to claim their rights to ownership of land and buildings – sometimes ending up in administrative courts. Many owners attempted to avoid conflict by selling their properties and dividing the money. This attracted a new breed of capital holders: ‘[…] ownership of the P hotel is now being disputed by the heirs. However, I heard that a person from Semarang or Klaten [in Central Java Province] had now bought it’ (Mr. P, sub-district official, interview August 2018).

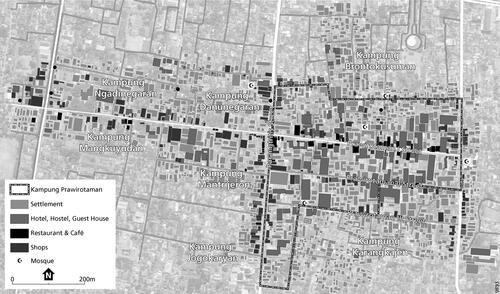

Responding to this series of crises, the tourism businesses including hotels, cafés, and restaurants, gathered under their collective action group, P4Y. They initiated an annual Prawirotaman Fest, seeking to expand beyond lodging services. The first event, held in 2013, featured local culture and dances (Purwandono, Citation2016). To date, there are 89 hotels and 58 cafés and restaurants in Prawirotaman – which consists of three councils (RW 7, 8, and 9) and also encompasses the areas to the west of the kampung: Danunegaran, Ngadinegaran, Mangkuyudan, and Mantrijeron (see ).

4.3. Contemporary Prawirotaman: welcoming newcomers – high-end hotels and cafés

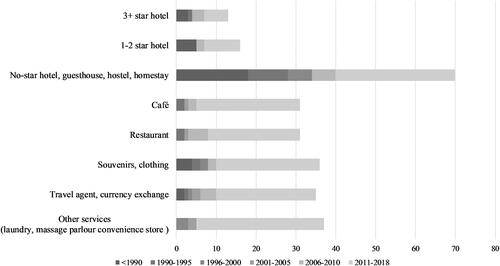

Many hotels, cafés, and restaurants were established after the triple crises, as well as souvenir shops, travel agencies, and massage and laundry facilities (see and ). Hotels tend to purchase and own the land upon which they stand, whereas most other services rent both the land and the building. Although our survey was unable to ascertain who owns such businesses, our interview with the sub-district official revealed that most of them are from elsewhere. ‘Oh, many of them are not coming from here [Yogyakarta], only a few are local. For example, [X] is from Malang [East Java], then many of them are renting, only a few bought the land’ (Mr. P, sub-district official, interview August 2018).

Figure 3. Building use and year of starting in Prawirotaman. (Source: Sub-district data 2018, interview with sub-district official).

Table 2. Building use and year of starting in Prawirotaman.

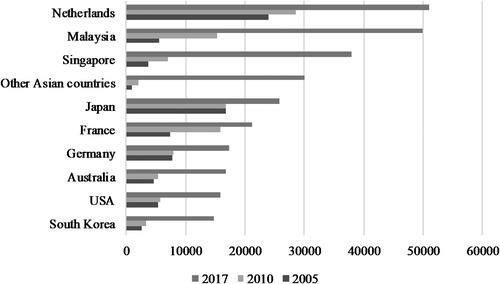

The development of lodging correlates with the growth of foreign tourism in Yogyakarta (see and ) which, by 2017, was double that in 2005, a year before the 2006 earthquake hit. Tourists from the Netherlands, Malaysia, and Singapore constitute the three largest groups of visitors to the area. Looking more closely, their profile has changed since the 1990s, trending toward younger tourists travelling in groups.

Last week I had a group of young people from the Netherlands and now I have a group from Sweden. It’s now more common that the tourists are like this (Mr. B, type 1, guesthouse owner, interview August 2018).

Also, there are differences in their length of stay and habits. Previously, a tourist might stay over a week, now two or three days, and there was more opportunity to talk, as short-stay tourists are less inclined to chat.

Figure 4. Top 10 foreign tourist origins in Yogyakarta based on hotel occupancy. (Source: Tourism Statistics 2005, 2010, and 2017).

Table 3. Top 10 foreign tourist origins in Yogyakarta based on hotel occupancy.

5. Arguments, complaints, and responses

5.1. Arguments and complaints

Most of the new places opening up are cafés and bars that sell alcohol. Accordingly, the area is called ‘Yogyakarta’s Legian’, referring to Legian street in Kuta on Bali, a famous alcohol-fuelled nightlife area that attracts many tourists. Previously, the area only had hotels and restaurants that also sold alcohol. However, as more cafés opened, two related activities emerged: live music and late-night drinking, both offered at open-door cafés, mostly in Parangtritis Street and Prawirotaman I Street. The live music scene starts gradually at sunset, around 6 p.m.; by 8, when darkness falls, the music picks up. On weekdays it stops around midnight but can continue until 3 a.m. on the weekend. These activities often also occupy the pavement fronting the bars and cafés. Although some hotels also offer alcohol, the combination of alcohol consumption and live music in a café setting creates a new form of night-time activity in the area. These new activities have attracted non-tourist visitors such as students and drinkers who simply want to ‘hang out’ in Prawirotaman, as several campus buildings are located nearby.

I really like this situation when it is crowded. My business needs more people so I like to meet and create a network. I like to work by myself and only focus on this [café] business. So, I will develop this business more. (Mrs. M, café owner, type 1, interview August 2018)

Although benefitting from tourism, not all homestay hosts and hotel owners approve of the current development. A resident who owns several hotels and homestays in the area complained about noise at night. He emphasised that those cafés are built without proper insulation and therefore produce a lot of noise and disturb his guests.

[Those cafés] get so crowded. They turn their lamp off and their windows open. So, they produce a lot of noise. I own a homestay beside the [mentioning a café] and it is so loud. […]. They actually write a statement letter to surrounding neighbour that they will not disturb. But, in fact, they still make it [noise]. [To apologise] they gave food for their neighbours. But after that, they do it again. (Mr. H, type 1, hotel owner, interview September 2018).

Among the residents who did not work in the tourism business (type 2), four complaints were common. First, those living near cafés complained about the noise. Designed as open buildings without adequate sound insulation, these problems persist well into the early morning:

Yeah, the music is so loud. The café has actually been there for a long time and there has never been a problem like this. The problem is with the new ones, and they put their music so loud. It is really crowded with consumers. In the beginning, they only played the music three times a week but now it is almost every day. […] I also need to put a no parking sign in front of my house so that my car can enter. If not, there will be numerous cars parked there. (Mrs. D, type 3, interview September 2018).

Also, several residents complained about the inconvenience of living near the newly built hotels. A local artist (type 3) was concerned not only about screaming tourists but also the noise from electricity generators:

It is difficult to concentrate to paint in here, more so, when the hotel is fully occupied, and the parking lot is full of cars. Also, when the power from the public electricity company is off, they start their own electricity generator. The noise from the generator is so noisy, I could not concentrate. (Mr. S, painter, type 3, interview September 2018)

Conversing informally whilst making our observations in the area, other residents (type 3) spoke of water and sun-shading issues (research note, September 2018). They complained that the newly built hotel took water from the well, raising concerns about potential water scarcity. Also, since hotels consist of several floors, they block the surrounding houses from sunshine.

Second, residents complained about traffic during the peak times – weekends and summer holidays – as some cafés blocked access to several houses and an alley. Several owners then put no-parking signs in front of their houses (see ). In an attempt to solve the traffic problems, two main streets were designated one-way. Furthermore, an agreement between the community in neighbourhood no. 26 requires tourism businesses to have their own parking places.

Third, following the success of the Prawirotaman Fest, a joint initiative of tourist businesses and residents, several residents of type 2, who are considered community figures, doubted the social benefit of the festival. It seemed only to benefit the business association. Since then, communication between the parties has deteriorated:

They looked as if they stood above us [as a boss in a hierarchy]. They use us as their public relation. […] So, when the tourism business in P4Y had an activity, they asked us [as a community] to mobilise our residents. For example, when they have a festival, they will ask us to close the street. It should not be that kind of command. (Mr. S, neighbourhood leader, type 2, interview September 2018)

Another issue emerged in neighbourhood 22 following the opening of a new café. To oversee growth in tourism, the neighbourhood created its own monitoring mechanism. When a new business is about to start construction, a community leader invites the owners to introduce themselves in a community meeting:

It is only a verbal agreement, if they want to open their business here, I asked them to talk in our monthly community meeting, I ask them to explain their aim and intention [of doing business] in front of our residents. They directly talk to residents. Residents are the witness. (Mr. A, neighbourhood leader, type 2, interview September 2018)

Despite the mechanism to oversee new businesses, a problem still arose; the owner refused to appear at the community meeting. Once construction was completed and the café opened, they began playing loud music, leading to protests. One of the neighbouring businesses is a guesthouse, and the guests say they cannot sleep.

After a series of complaints, the leader of the neighbourhood approached the owner and the manager, which resulted in a written undertaking not to play music after midnight. However, the owner ignored it; the situation came to a head after Eid al-Fitri, an important Islamic event. As residents walked to the mosque for morning prayers, they saw the owner of the café having intercourse out front. After prayers, they confronted the owner with what they had seen, asking him to take responsibility for the vulgarity they had witnessed, but he escaped through the café’s rear exit. Unsurprisingly, this incident created acrimony between the residents and the café:

We have others like [mentions two names]. They offer a place to eat within the concept of semi-café . The consumer can eat and gather there, then drink [alcohol] only as an aside. However, this café is different. He created this café, designed to drink with music. Bring beer with music. Look at the state in which it is, and this is indeed a different place, not for eating. (Mr. Y, neighbourhood leader, type 2, interview 22 September 2018)

Complaints like these – about noise, partying, and alcohol tourism (Füller & Michel, Citation2014; Pixová & Sládek, Citation2017; Sommer & Helbrecht, Citation2017), traffic (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017; Vianello, Citation2016), commercialisation (Colomb & Novy, Citation2017) as well as tourists’ behaviour (Hughes, Citation2018; Rouleau, Citation2017) – are common elsewhere. However, in Prawirotaman, residents were not only upset about the tourists but also about the businesses. The residents’ sleep is disrupted by the design of open-door cafés and the loud music that emanates from within. Regarding traffic, residents indicated that tourism businesses should be required to have their own parking places. In terms of communication and mutual benefit, community figures cited inadequate attention to the needs of residents. Lastly, the anti-social behaviour of the café owners was an aggravation. Although the residents had equipped themselves with a monitoring mechanism, it has no legally binding status and can thus easily be circumvented or ignored.

5.2. Mobilisation of protests

5.2.1. Protesting in silence

Although residents of type 2 do not benefit individually from tourism, as a community they do benefit indirectly – for example, during the pitulasan ceremony. For reasons cited above, they chose to protest in silence. This approach was inspired by a series of kampung meetings held to decide on a five-year plan and the theme for the kampung. This dual agenda had to be submitted to the mayor’s office within two weeks, so two meetings were arranged. The first was moderated by a municipal official and attended by more than 25 representatives of the community but none of tourism businesses. At the beginning, the official explained the urgency of the five-year plan and expanded on the 28 themes offered by the government. He then tried to designate Prawirotaman as a tourism kampung by emphasising its popularity as kampung bule. However, the attendees preferred the child-friendly theme because they felt that the area had no tourist attraction and no significant contribution from tourism. A resident seated beside me whispered that this is also part of their revenge on the tourism businesses (research note, September 2018). At the end of the meeting they decided to form a smaller group, this time consisting of five important kampung representatives, to decide on the five-year plan and determine the kampung’s theme.

We also joined the follow-up meeting with the smaller group when people spoke more freely. Those attending opposed the theme of tourism, citing the same reasons as before. They also discussed the minimal contribution tourism businesses made to their kampung – a contribution which they felt had been decreasing over the years. Several days later, however, we received a message confirming that they needed to follow the suggestion from the government – a ‘win–win solution’. They then agreed on the theme ‘tourism, child-friendly and culturally hospitable kampung’.

5.2.2. Creating alliances

Several distant neighbours from the surrounding kampungs (type 3) reacted differently to tourism-related issues, as indicated by an incident (concerning alcohol) that took place during the New Year celebrations of 2018. That incident can be traced back to an alliance between mosques. The alliance was led by a resident from Brontokusuman – a kampung to the north – who is prominent in an Islamic political party. The first meeting was held in Prawirotaman mosque and was announced as a regular monthly recitation. The residents were surprised to discover that the meeting was a presentation over the development of cafés in the area, including several pictures showing inappropriately dressed waitresses and alcohol consumption. The presenter then proposed the formation of a mosque alliance and asked that it be based in Prawirotaman mosque to show that the movement was also being supported by the residents. However, some attendees objected, so the coordination was designated to a mosque in Brontokusuman – along with the office of the head of the alliance, Mr. H. He stated that mosques in the surrounding kampungs should actively push to control the growth of cafés:

In essence, a mosque alliance at that time arose because of the concerns of several parties related to the latest developments in Prawirotaman. Including the development of the cafés, finally, we have to investigate what happened. […] this rapid development has indeed occurred in the last five years. So, first, around five years ago, unless I am mistaken, it was not much. In these five years, then the increase is quite rapid so that the total number of cafés in the Prawirotaman and Mantrijeron areas reached 17. (Mr. H, interview August 2018)

Apparently, a resident of Kampung Karangkajen is also a member of an advisory board:

Oh, here I am the advisor. Yes, they [the committee of this mosque alliance] often meet with me. Oh, yes, Mr. H [the name of the leader of the alliance]. He also often comes here. That is what advisors should do. …. During public meetings I will let them to do [organise] by themselves. I attend the closed meetings, I usually participate. And, it must be said that I do not represent the mosque. (Mr. J, interview September 2018)

After forming the alliance, the coalition took three important steps. First, they tried to make contact with the newly elected vice-mayor’s office to voice their concerns about alcohol consumption and also about the vulgar behaviour of the waitresses of several cafés. With the help of one of the political parties, they pushed the vice-mayor to take action. The crack-down on the sale of alcohol occurred at the peak of the 2018 New Year celebrations. Although actioned by Satpol PP (a government agency), we suspect that the report came from the mosque alliance. As a result, hundreds of alcoholic drinks were confiscated by Satpol PP (see Aditya, Citation2018; Hanafi, Citation2018).

Second, following the crack-down, the alliance hung several banners protesting the sale of alcohol in the area (see ). The banners, reading ‘Stop Cafés Selling Beer and Alcohol in Muslim Majority Areas’, were initially found throughout Prawirotaman, as confirmed by the head of the Islamic Alliance: ‘Oh, there used to be plenty of them, along the street. We put them also in strategic spaces but they are now gone or have been removed. Also, because it is a long time ago, some are broken’ (Mr. H, interview August 2018). Currently, the only one left is in front of a mosque near Prawirotaman.

Third, a month after the incidents, this alliance asked cafés to remove the beer logos on their shops. The proprietors then displayed the logos and signs inside to prevent future raids but also to avoid the anger of conservatives. In addition, the leader of this mosque alliance said he had a plan to confront the café business in Prawirotaman by establishing a ‘halal’ café which would not serve alcohol, pointing to an example in Kampung Jogokariyan.

In response to those incidents, the cafés then formed a group called Entrepreneurs of Cafés and Restaurants in Special Area. This group supported their interests elsewhere too, for instance in Sosrowijayan, where a concentration of cafés selling alcohol was also threatened by this mosque alliance. This group was led by a café owner who had a connection with provincial and urban politics, while the secretary was a key figure in Prawirotaman. After organising several meetings, they attempted to calm the situation by asking the provincial government to stop the raids. As a result, from February to September 2018, there were no raids in the area.

Generally speaking, there has always been dissent between people who drink alcohol and people who consider drinking haram. However, in 2018, the disapproval was more explicit, mainly for two reasons. The first is political; since 2004, the number of conservatives has grown following the successful campaign of an Islamic party (Mietzner & Muhtadi, Citation2018). This party was an invisible presence behind the mosque alliance, facilitating contact with the office of the vice-mayor. Second, there has been a general trend amongst Islamic Indonesians to be ‘better’ Muslims, called hijrah (Ali et al., Citation2019; Hasan, Citation2019). This movement operated through the interplay between Islamic da’wa (preaching), popular culture and the growing use of information technology.

6. Discussion and conclusion: a Kampung for residents and tourists?

While Prawirotaman has long attracted visitors, its popularity has recently spiked, along with its level of development. Traditionally the kampung has adapted to accommodate international tourists, a process known as touristification, blending the needs of residents with those of vacationers. Initially, though regretting the disappearance of several community activities, residents emphasised the benefits such as the ease of collecting funds for community activities and their skill in interacting with international visitors.

However, the process has been accelerating, with more high-end hotels, cafés, and restaurants as well as new activities such as open-door alcohol consumption and loud music and new types of visitors. Previously, there were only backpackers; now visitors come en-masse – high-end tourists, students, and drinkers who simply want to ‘hang out’. In response, residents now complain about the noise, late-night drinking, and vulgar scenes. Discontent is also rising in the surrounding kampungs, the religious identity of which heavily influences their rejection of tourist business, resulting in the alcohol raids of 2018 and the removal of signs promoting beer.

There are two conclusions that we would draw on the basis of observations in Prawirotaman. First, we found that residents’ complaints change over time and are context-dependent. Doxey’s (Citation1975) Irridex describes how irritation about tourism develops over time. The first phase of Prawirotaman’s touristification fits in with the first two stages of this index. During the euphoric stage, residents felt they had benefitted. They entered the second stage – apathy – once they became accustomed to the presence of tourists. Meanwhile, the second phase of touristification exhibited signs of the impending third and fourth Irridex stages – eventually the sheer number of visitors would evoke annoyance. The area is now in the final stage, antagonism, and hostile feelings are being expressed about tourism. Looking closely at responses at this stage, we found distinctions between residents. Those who benefit directly, such as café owners, are the main supporters of nightlife. They profit from it so they have less incentive to complain, yet several hotel owners remarked that the noise disturbs some guests. Other residents expressed multiple concerns – noise, traffic, and an imbalance in the perceived benefits. Moreover, inhabitants of adjacent kampungs expressed their displeasure by raising religious issues, feeling that some of the activities that take place in Prawirotaman disrupt exercise of their religious beliefs.

Second, we found an association between the antagonism stage of the Irridex and the complaints of distant inhabitants and religious leaders as well as with heightened tensions among direct residents. Those in the direct vicinity who are not benefitting from tourism businesses tend to protest in silence; for example, some post no-parking signs outside garages and raise their concerns at community meetings. Their subdued response suggests tolerance of the negative effects of tourism. Even though they do not profit directly from tourism, they do indirectly benefit as a community, for example by receiving annual funding for pitulasan. As tourism brings no benefits to the distant inhabitants, neither as individuals nor as a community, they are more likely to challenge its presence. To mobilise protest, they formed an alliance with the mosque and a political party and also contacted the vice-mayor. Their discontent was manifest during the alcohol raids of the 2018 New Year celebration and when they mounted banners condemning the sale of alcohol.

To conclude, Prawirotaman is living proof that a city in the global south can work out interventions that ‘look beyond the local place, to implications around the world’ (Massey, Citation2007, p. 205). The residents are attending to the global tourism competition (Beaverstock et al., Citation1999, Citation2002) by providing lodging services for international tourists. But as a kampung, they are still rooted in their own context (Triandis, Citation1989) and conscious of their neighbours’ stricter adherence to religious norms. The voices of residents could change again if the tourism business were to develop a format that would be acceptable to locals and other stakeholders. If so, Prawirotaman might become a more harmonious environment.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Iwan Suharyanto

Iwan Suharyanto is a PhD candidate in the Department of Human Geography and Urban Planning at Utrecht University, the Netherlands and a lecturer in the Department of Architecture and Planning at Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. His research focuses on night-time economy and urban management.

Irina van Aalst

Irina van Aalst is an Urban Geographer at Utrecht University and program director of the Master Human Geography. She publishes on urban public spaces and surveillance, youth, and nightlife districts.

Ilse van Liempt

Ilse van Liempt is Assistant Professor in Urban Geography at Utrecht University. She publishes on migration, public space, gender, and the night.

Annelies Zoomers

Annelies Zoomers is a Professor at the International Development Studies at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. She has published extensively on sustainable livelihoods and poverty alleviation, the global land rush and international migration.

References

- Aditya, I. (2018, January 27). Razia Cafe Kawasan Prawirotaman, Ratusan Botol Miras Diamankan (Raid on Cafe at Prawirotaman, Hundreds of Alcohol to be Secured). Kedaulatan Rakyat. https://krjogja.com/web/news/read/56265/Razia_Cafe_Kawasan_Prawirotaman_Ratusan_Botol_Miras_Diamankan

- Ali, H., Purwandi, L., Nugroho, H., Halim, T., & Firdaus, K. (2019). Indonesia Moslem Report 2019: “The Challenges of Indonesia Moderate Moslems". Jakarta. https://alvara-strategic.com/indonesia-muslim-report-2019/

- Beard, V. A., & Dasgupta, A. (2006). Collective action and community-driven development in rural and urban Indonesia. Urban Studies, 43(9), 1451–1468. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600749944

- Beaverstock, J. V., Doel, M. A., Hubbard, P. J., & Taylor, P. J. (2002). Attending to the world: Competition, cooperation and connectivity in the World City network. Global Networks, 2(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00031

- Beaverstock, J. V., Smith, R. G., & Taylor, P. J. (1999). A roster of world cities. Cities, 16(6), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(99)00042-6

- Bereskin, E. (2016). Tourism provision as protest in ‘post-conflict’ Belfast. In C. Colomb & J. Novy (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (pp. 166–184). Routledge.

- BPS. (2018). Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Province in figures. BPS-Statistics of D.I. Yogyakarta Province. https://yogyakarta.bps.go.id/publication/2018/08/16/ec8403f8694d2ff343d36d88/provinsi-daerah-istimewa-yogyakarta-dalam-angka-2018.html

- Cheshire, L., Fitzgerald, R., & Liu, Y. (2019). Neighbourhood change and neighbour complaints: How gentrification and densification influence the prevalence of problems between neighbours. Urban Studies, 56(6), 1093–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018771453

- Colomb, C., & Novy, J. (2017). Urban tourism and its discontents: An introduction. In C. Colomb & J. Novy (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (1–30). Routledge.

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (2019). The phenomena of overtourism: A review. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(4), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-06-2019-0090

- Doxey, G. V. (1975). A causation theory of visitor–resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. Travel and Tourism Research Associations. Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings, 8 September 1975 (pp. 195–198).

- Füller, H., & Michel, B. (2014). “Stop being a tourist!" New dynamics of urban tourism in Berlin–Kreuzberg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12124

- Geertz, C. (1960). The religion of Java. University of Chicago Press.

- Gravari-Barbas, M., & Guinand, S. (2017). Tourism and gentrification in contemporary metropolises: International perspectives. Taylor & Francis.

- Guinness, P. (2009). Kampung, Islam and State in Urban Java. NUS Press.

- Hanafi, R. (2018, 4 January 2018). Razia Kafe di Prawirotaman Yogya, Petugas Sita Ribuan Botol Miras [Raids in Prawirotaman's Café, Officer Took Thousands of Alcohol]. Detik. https://news.detik.com/berita-jawa-tengah/d-3798000/razia-kafe-di-prawirotaman-yogya-petugas-sita-ribuan-botol-miras

- Hasan, H. (2019). Contemporary religious movement in Indonesia: A study of Hijrah festival in Jakarta in 2018. Journal of Indonesian Islam, 13(1), 230–265. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2019.13.1.230-265

- Hawkins, M. (1996). Is Rukun dead? Ethnographic interpretations of social change and Javanese culture. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 7(1), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.1996.tb00329.x

- Hospers, G.-J. (2019). Overtourism in European cities: From challenges to coping strategies. ifo Institute-Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich: CESifo Forum.

- Hughes, N. (2018). ‘Tourists go home’: Anti-tourism industry protest in Barcelona. Social Movement Studies, 17(4), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1468244

- Ioannides, D., Röslmaier, M., & van der Zee, E. (2019). Airbnb as an instigator of "tourism bubble" expansion in Utrecht's Lombok neighbourhood. Tourism Geographies, 21(5), 822–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1454505

- Kawamura, C. I. (2004). Peralihan Usaha dan Perubahan Sosial di Prawirotaman, Yogyakarta 1950–1990-an [The shifting business and social changes in Prawirotaman, Yogyakarta 1950–1990s] [Unpublished bachelor thesis]. Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Khotifah. (2013). Perubahan Sosial Dan Ekonomi Kampung Prawirataman, Yogyakarta 1920–1975 [Social and economic changes in Kampung Prawirotaman, Yogyakarta 1920–1975] [Unpublished bachelor thesis]. Universitas Sanata Dharma.

- Lee, C.-C., & Chang, C.-P. (2008). Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tourism Management, 29(1), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.02.013

- Maas, M. (2018, 6 February). Hoe razzia's een einde maakten aan het drankgelag in Yogyakarta. de Volkskrant. https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/hoe-razzia-s-een-einde-maakten-aan-het-drankgelag-in-yogyakarta∼b603a780/?referer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

- Manning, J., Wertheimer, K., & Time Out editors. (2018). The 50 coolest neighbourhoods in the world. https://www.timeout.com/coolest-neighbourhoods-in-the-world

- Mason, P., & Cheyne, J. (2000). Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00084-5

- Massey, D. (2007). World city. Polity.

- Mermet, A.-C. (2017). Airbnb and tourism gentrification: Critical insights from the exploratory analysis of the "Airbnb syndrome" in Reykjavik. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises (pp. 52–74). Routledge.

- Michalak, L., & Trocki, K. (2006). Alcohol and Islam: An overview. Contemporary Drug Problems, 33(4), 523–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145090603300401

- Mietzner, M., & Muhtadi, B. (2018). Explaining the 2016 Islamist mobilisation in Indonesia: Religious intolerance, militant groups and the politics of accommodation. Asian Studies Review, 42(3), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1473335

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and tourismphobia: A journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tourism Planning & Development, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1599604

- Nas, P. J., & Boender, W. (2003). The Indonesian city in urban theory. In P. J. Nas (Ed.), The Indonesian town revisited (Vol. 1, pp. 3–16). LIT Verlag.

- Nofre, J., Giordano, E., Eldridge, A., Martins, J. C., & Sequera, J. (2018). Tourism, nightlife and planning: Challenges and opportunities for community liveability in La Barceloneta. Tourism Geographies, 20(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1375972

- Novy, J. (2016). The selling (out) of Berlin and the de-and re-politicization of urban tourism in Europe’s "capital of cool. In C. Colomb & J. Novy (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (pp. 52–72). Routledge.

- Nunkoo, R., Smith, S. L. J., & Ramkissoon, H. (2013). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: a longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.673621

- Olt, G., Smith, M. K., Csizmady, A., & Sziva, I. (2019). Gentrification, tourism and the night-time economy in Budapest's district VII: The role of regulation in a post-socialist context. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 11(3), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1604531

- Oosterwechel, M. (2018). Geen Bier hier: De drooglegging van Yogyakarta [No beer here: The prohibition in Yogyakarta]. NOS. https://nos.nl/artikel/2215661-geen-bier-hier-de-drooglegging-van-yogyakarta.html

- Pavlić, I., & Portolan, A. (2016). Irritation index. In J. Jafari & H. Xiao (Eds.), Encyclopedia of tourism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01384-8_564.

- Pixová, M., & Sládek, J. (2017). Touristification and awakening civil society in post-socialist Prague. In C. Colomb & J. Novy (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (pp. 87–103). Routledge.

- Poria, Y., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2003). Tourism, religion and religiosity: A holy mess. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(4), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667960

- Prabawa, T. S. (2010). The tourism industry under crisis: The struggle of small tourism enterprises in Yogyakarta (Indonesia) [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Purwandono, A. (2016, 23 July). Minggu, Perwakilan 20 Negara Saksikan Kirab Prawirotaman [Sunday, representatives of 20 countries follow the Prawirotaman Fest]. Kedaulatan Rakyat. https://krjogja.com/web/news/read/3655/Minggu_Perwakilan_20_Negara_Saksikan_Kirab_Prawirotaman

- Raharjo, W. (2010). Speculative Settlements: Built form/tenure ambiguity in Kampung development [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. The University of Melbourne.

- Rahmi, D. H., Wibisono, B. H., & Setiawan, B. (2001). Rukun and Gotong Royong: Managing public places in an Indonesian kampung. In Public places in Asia Pacific cities (pp. 119–134). Springer.

- Rouleau, J. (2017). Every (nocturnal) tourist leaves a trace: Urban tourism, nighttime landscape, and public places in Ciutat Vella, Barcelona. Imaginations Journal, 7(2), 58–71.

- Rusdi, H. (2009). Hubungan Perubahan Fungsi Kawasan dengan Perubahan Pemanfaatan Lahan: Studi Kasus Kawasan Prawirotaman Kota Yogyakarta [The relation between the changing function of an area with land use development: A case study at Prawirotaman Yogyakarta] [Unpublished bachelor thesis]. Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Sanad, H. S., Kassem, A. M., & Scott, N. (2010). Tourism and Islamic law. In N. Scott & J. Jafari (Eds.), Tourism in the Muslim world (pp. 17–30). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Setiawan, B. (1998). Local dynamics in informal settlement development: A case study of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. University of British Columbia.

- Sequera, J., & Nofre, J. (2018). Shaken, not stirred: New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrification. City, 22(5–6), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2018.1548819

- Shakeela, A., & Weaver, D. (2018). “Managed evils” of hedonistic tourism in the Maldives: Islamic social representations and their mediation of local social exchange. Annals of Tourism Research, 71, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.04.003

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Sihombing, A. (2004). The transformation of Kampungkota: Symbiosis between Kampung and Kota – A case study from Jakarta. International Housing Conference in Hong Kong, Housing in the 21st Century: Challenges and Commitments.

- Sirakaya, E., Teye, V., & Sönmez, S. (2002). Understanding Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in the Central Region of Ghana. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750204100109

- Smith, M. K., Sziva, I. P., & Olt, G. (2019). Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156832019.1595705 https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1595705

- Sommer, C., & Helbrecht, I. (2017). Seeing like a tourist city: How administrative constructions of conflictive urban tourism shape its future. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-07-2017-0037

- Sullivan, J. (1980). Back alley neighbourhood: Kampung as urban community in Yogyakarta. Center of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University.

- Sullivan, J. (1986). Kampung and state: The role of government in the development of urban community in Yogyakarta. Indonesia, 41, 63–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/3351036

- Sullivan, J. (1992). Local government and community in Java: An urban case-study. Oxford University Press.

- Sumintarsih, & Adrianto, A. (2014). Dinamika Kampung Kota Prawirotaman dalam Perspektif Sejarah dan Budaya [The dynamics of urban Kampung Prawirotaman from the perspective of history and culture]. Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya.

- Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 96(3), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.506

- Vianello, M. (2016). The no Grandi Navi campaign: Protests against cruise tourism in Venice. In C. Colomb & J. Novy (Eds.), Protest and resistance in the tourist city (pp. 185–204). Routledge.

- Wachsmuth, D., & Weisler, A. (2018). Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(6), 1147–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18778038

- Wall, G., & Mathieson, A. (2006). Tourism: Change, impacts, and opportunities. Pearson Education.

- Zamani-Farahani, H., & Musa, G. (2012). The relationship between Islamic religiosity and residents’ perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tourism Management, 33(4), 802–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.003

- Zhang, J., Inbakaran, R. J., & Jackson, M. S. (2006). Understanding community attitudes towards tourism and host–guest interaction in the urban–rural border region. Tourism Geographies, 8(2), 182–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600585455