Abstract

Borders have significant potential as tourist attractions, and there are many aspects of unique border locations capable of attracting people’s attention. One such attraction would be the tripoint, i.e. a place where the borders of three different countries meet physically at a single point. One of the newest such features in Europe – where the borders of Poland, Slovakia and Czechia meet in the Beskid Mountains – provides an example of far-reaching border-related changes in the EU, the creativity of local authorities as supported by EU funds, and the creation of a new transboundary meeting space with a strong integration-related identity. It also exemplifies the concept of a new tourist space beyond traditional tourist destinations. The development of tourism at tripoints is modelled ideographically. Spatio-temporal analysis with scalar dimensions shows the spatial relationships between tripoints and tourism development: the central point, the immediate vicinity, the proximal neighborhood (or local zone) and the regional zone. The tripoint examined here supports a proposal for a spatial planning model at tripoints in Europe.

摘要

国界作为旅游景点具有巨大的潜力, 独特的国界地点有许多方面能够吸引人们的注意。一个这样的吸引力是三国交界, 即三个不同国家的边界在一个单一的点物理上相汇的地方。波兰,斯洛伐克和捷克三国交汇的贝斯基德山(Beskid Mountains), 作为欧盟最新的一个特色, 提供了一个典范, 欧盟内陆国界的诸多变化, 地方当局在欧盟基金支持下所作出的创新, 创造了一个新的具有强烈一体化形象的跨国界交汇空间。它还体现了超越传统旅游目的地的新旅游空间的概念。本文从概念上对三国交界的旅游开发进行了建模。通过标量维度的时空分析, 揭示了中心点、邻近点、近邻点(或局部区域)和区域点与旅游开发的空间关系。这里研究的三国交界案例支持了欧洲在三国交界空间规划模型的提议。

Introduction

The development of tourism in borderlands is increasingly important. It has been facilitated by recent border openings and the changing role of borders since the widespread geopolitical and socio-economic transitions of the past quarter-century in many parts of the world. However, despite the growing number of studies concerning the relationships between borders and tourism or tourism development in borderlands, this topic continues to be understudied (Mayer et al., Citation2019).

Tourism is regularly seen as a catalyst for development, and as a creator of space and place. This reflects its tendency to shape and standardize identity narratives and the tangible spatial and intangible (symbolic) organization of border landscapes (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2011; Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017). Thanks to their geopolitical, historical or symbolic value, borders have significant potential as tourist attractions, and have many kinds of appeal to tourists (Timothy, Citation2001; Timothy et al., Citation2016). The public fascination inspired by certain unique locations has also been acknowledged by the tourism industry, and many specific localities have been transformed into tourist attractions that have achieved significance as international destinations (Birkeland, Citation2002; Jacobsen, Citation1997; Pretes, Citation1995). In recent years, several studies have recognized the significance of border walls, border remnants, international enclaves and border cultures as attractions and resources serving the development of tourism at the local and regional levels (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2011; Prokkola, Citation2007; Prokkola & Lois, Citation2016; Timothy, Citation2001). This includes unique locations, such as invisible geodetic lines (e.g. the equator or the Arctic Circle) or geographical extreme points (e.g. the easternmost point of the European Union), many of which have become tourist attractions (Jacobsen, Citation1997; Löytynoja, Citation2008; Timothy, Citation2001).

Many elements of unique border locations attract people’s attention (Timothy et al., Citation2016). One of these is the international tripoint. In this instance, the borders of three different countries meet physically at one point, on a very small geographical scale. One of the primary appeals of these curiosities therefore lies in unique locational attributes. These include the possibility of three borders being crossed and three countries visited over a short time and small space. Yet even at this micro-scale, tripoint borders may delimit different languages, political systems, histories and culinary traditions.

While much academic attention has been devoted to the role of borders in tourism since the 1990s, the specific subject of tripoints and their role in tourism has not been studied, even though these situations present additional opportunities and challenges not typically associated with ‘normal’ borderlines. This lack of research attention notwithstanding, there are more than 170 tripoints in the world, each with its own set of political histories, practical policies and potential for economic development. In Europe alone, there are 46 international tripoints, with 21 of these are located on the internal borders of the European Union and the Schengen Zone.

Many tripoints possess symbolic meanings both as special places located between three countries (with border markers, national flags, and monuments built in commemoration) and on a regional scale with the potential for transboundary cooperation (Kałuski, Citation2006, Sohn et al., Citation2009). In recent decades, several such locations have transformed into international tourist attractions. A few examples include the point where Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium meet near Vaals (Timothy et al., Citation2014); where Germany, France and Switzerland meet at Basel (Leimgruber, Citation1998; Reitel, Citation2013); at Schengen where Germany, France and Luxemburg come together (Sohn et al., Citation2009), and at Ours, where the meeting point of Belgium, Germany and Luxemburg is commemorated with the European Union park, recreational infrastructure, and historic border markers. Historically, one of the first documented tourism focuses on tripoints occurred at the meeting point of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Russian Empire and the German Empire in the mid-nineteenth century (Kałuski, Citation2006).

New tourist attractions have been created at several tripoints in Central and Eastern Europe, both on internal EU borders (e.g. near Bratislava where Austria, Slovakia and Hungary meet; near Zittau where Germany, Czechia and Poland meet), and on the external borders of the EU (e.g. the Poland, Lithuania and Russia tripoint). To illustrate the recent development of tourism on the basis of tripoint geographical curiosity, this paper examines one of the newest examples in Europe – located where the borders of Poland, Slovakia and Czechia meet in the Beskid Mountains. This tripoint came into existence with the disintegration of Czechoslovakia on January 1, 1993, when Slovakia and Czechia became separate countries (Więckowski et al., Citation2012). In 2004, Poland, Slovakia and Czechia all joined the European Union, transforming this tripoint into an intra-European Union border. In 2007, all three countries fully implemented the Schengen Agreement, which eliminated all border controls between them (Kurowska-Pysz, Citation2016; Więckowski, Citation2018).

Against this background, the work detailed here addresses the tourism-related characteristics of tripoints, a unique and relatively recently acknowledged tourist space not yet addressed in the literature. Utilizing a case study, the paper elucidates why tripoints matter for tourism from a socio-spatial perspective. The research questions are defined as follows:

Where and why are borders a basis for tourism development? What spatial forms do they take?

How are the border resources of tripoints transformed into tourism assets? Which elements are used in tourism, and how do they function in reality?

The tripoint as a symbolic place between abandonment and tourist attraction

International borders enclose the territory of a state and control the flows of people and goods. Currently, the transition processes of debordering is breaking down barriers and helping to overcome the negative aspects of a peripheral location (Mayer et al., Citation2019). Only recently have borders been perceived as a resource and legitimate location for developing tourism (Prokkola, Citation2007; Sohn, Citation2014). Increasingly, they are now venues serving the latter purpose, implying in this way an extension of tourism space (Prokkola, Citation2007; Stoffelen, Citation2018; Timothy et al., Citation2016). The creation of that space reflects wider political, economic and social processes. However, tourist destinations are structures generated by history that are experienced, represented and developed through different economic, political, social and cultural forces, and discursive practices (Saarinen, Citation2004).

In terms of supply - demand on the one hand, we find the curiosity of tourists seeking to explore new places and experiences away from traditional destinations, in this way developing niche tourisms and responding to overtourism. On the other hand, there is a desire on the part of local actors for the potential of resources, symbolisms and transboundary integration to be put to use. Notable among actors of this kind are those working to develop cross-border regional projects – who may mobilize borders as “place-making” instruments (Scott, Citation2012).

For tourism, international borders have traditionally represented barriers, destinations, transit spaces and determiners of tourism landscapes (Timothy, Citation2001; Timothy & Gelbman, Citation2015). There are many borderlands in which tourism is considered the most important economic sector (Timothy, Citation2001; Więckowski, Citation2010), and/or the sole opportunity for development. New tourist spaces are observable with changing border functions, and as tourism infrastructure is brought closer to state frontiers. As part of this, new transboundary patterns are arising (Mayer et al., Citation2019; Stoffelen, Citation2018). Borders and their policies influence the development of tourism, while simultaneously generating attraction for tourists (Timothy, Citation1995) and creating new possibilities for tourism innovation and cross-border cooperation (Blasco et al., Citation2014; Stoffelen, Citation2018; Weidenfeld, Citation2013).

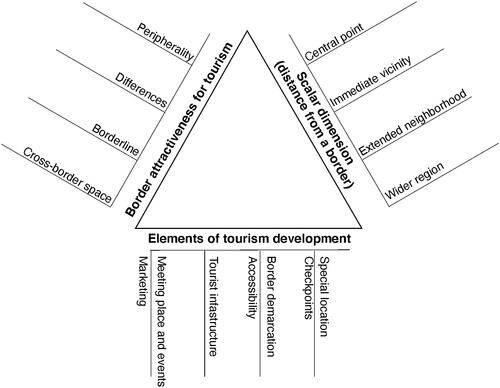

A synthesis of relevant border and tourism literature shows how the specific attractiveness of borderlands for tourism can be categorized into at least four overarching types, including by reference to peripherality, differences, borderlines and cross-border spaces. These settings underscore the author’s proposal and are helpful to analysis of the significance of tripoints and their use in the development of tourism.

Peripherality

The first attraction factor refers to a peripheral location near a state border which could be used for tourism whether borders are open or closed. A peripheral socio-economic and/or political position usually only enhances physical peripherality and is usually associated with low accessibility (Kolosov & Morachevskaya, Citation2020). On the one hand, a peripheral location could favour the development of tourism (e.g. Christaller, Citation1964; Timothy, Citation2001), and can be thought to possess high-quality natural and cultural resources (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2011; Meyer et al., Citation2019; Timothy, Citation2001; Timothy et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, as borderlands are geographically remote from mass markets, the low level of economic development may imply low-quality tourism infrastructure and services. Furthermore, the limited accessibility (denoting higher transportation and communication costs to and from the core areas and their markets) also ensures protracted journeys by tourists in reaching the destination (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2010; Więckowski et al., Citation2012).

There are many locations worldwide - and especially in Central and Eastern Europe - where borderlands are indeed rather peripheral from the socio-economic point of view (Kolosov & Morachevskaya, Citation2020). This has tended to increase their role as tourist destinations (Więckowski, Citation2010). Peripheral areas are mainly venues for recreational tourism, but are also gaining in importance when it comes to educational and cultural tourism.

Peripherally-located tripoints have not been of significant tourist interest, mainly on account of their relative inaccessibility. This would be a weaknesses inherent in the peripheral location of borderlands. Many tripoints remain poorly accessible (far from roads), owing to inhospitable environments (e.g. deserts and swamps), topographic barriers (e.g. mountains), and other physical features hard to navigate and thus inaccessible to ordinary tourists. In a sense, the contact location of three countries represents a ‘double periphery’, as they are distant from human settlements and peripheral on both the national and regional scale(s).

Differences (contrasts)

The second attraction factor entails specific activities that have developed in close proximity to international boundaries. This in turn reflects contrasting policy frameworks and economic systems between the bordered states in this sense manifesting particular functions of border (Raffestin, Citation1986; van Houtum & van Naerssen, Citation2002) – above all as “lines of difference” (Herrschel, Citation2011). Familiar activities spurred by cross-border differentness include shopping, gambling and prostitution, but also healthcare services (Timothy, Citation2001). In this sense, what is different on the other side attracts tourists because of product differences, lower prices, other services or the fact of products or services being better or non-existent (or limited) (Timothy, Citation2001; Van der Velde & Spierings, Citation2010; Więckowski, Citation2010). The most popular ways of capitalizing on such differences include through shopping tourism (Di Matteo & Di Matteo, Citation1996, Leimgruber, Citation2005; Szytniewski et al., Citation2017; Timothy & Butler, Citation1995; Van der Velde & Spierings, Citation2010), which also entails the purchase of alcohol, tobacco and gasoline (Rietveld et al., Citation2001; Banfi et al., Citation2005).

Tourist interest can also be fostered by cultural contrasts between the two sides of a border, or a specific border culture and identity that have developed over time (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2011). In many cases, borders represent an abrupt change in language, religion, political attitudes, cultural traditions, and social mores. National holidays on either side of a border are also obviously different, and business hours may vary. Such cultural differences wield considerable appeal for many would-be visitors who desire to experience the ‘otherness’ associated with being elsewhere.

Thus, part of the essence of tourism in the vicinity of a tripoint may reflect a state’s desire to differentiate itself from its neighbors. or boast of its own glory. That was, for example, the case historically – at the tripoint between the three historical Empires noted earlier. Today, the emphasizing of differences and demonstration of territoriality can also form part of a deliberate procedure, marked by the placing of different flags at the point of convergence, with differences in cultural heritage and national symbols in the general vicinity emphasized - and also utilized in marketing.

Borderlines

The third magnet for tourism represented by borders relates to the borderline itself. Frequently, these function as objects of tourist attention because of their geopolitical, historical or symbolic values and meanings. The very act of crossing borders may be a travel motivation, perhaps combined with the symbolic straddling or crossing of a line that marks the interface between different social, cultural and economic realms (Ioannides et al., Citation2006; Timothy, Citation2001). In most parts of the world, pillars, inscribed stones, or other symbols demarcate borders, to indicate the precise location at which two (or three) countries meet. Some tourists show an interest in seeing a border, touching it, straddling the markers, and taking classic selfies with border markers, welcome signs, or displays of flags and coats of arms.

According to Timothy et al. (Citation2016), precise borderlines exude most of their appeal in at least six ways: through interesting anomalies in the landscape (e.g. walls, fences, guard towers, gateways, and unique boundary markers); the potential to observe the “other side” across the line because it is interesting owing to opposing ideological systems or adversarial relations; attractions (e.g. golf courses or historic buildings) being partitioned by a border; natural or cultural areas (e.g. a beach or ancient ruins) being divided by a border; border-themed attractions (e.g. museums, fragments of a former border); and borders that are commemorated as historical markers. Additional perspectives may include borders as symbolic meeting places, cardinal directions or geometric curiosities (e.g. northernmost, easternmost), highest/lowest points, or tripoints.

Tripoints are in this sense symbolic places, and reaching them may be seen as an attraction. The opportunity to be in three countries at the same time represents an additional appeal. Many authorities and entrepreneurs operating in the vicinity of tripoints use this curiosity factor to enhance the location, by constructing bridges to connect international river banks, erecting larger monuments exactly where the borders meet, designing walking trails, and building picnic tables, barbecue areas and other leisure facilities, sculptures and public art; and installing interpretive signage that tells about the history and geography of the region.

Cross-border spaces

The fourth appeal of borders for tourism is their cross-border character. When borders undergo the process of debordering (opening), they may become cross-border spaces that are permeable, and a source of greater potential for cross-border integration (Herrschel, Citation2011). The main effects of these changes have been an increase in tourist flows, and the creation of new cross-border tourist spaces on both sides of a border (Mayer et al., Citation2019; Więckowski, Citation2018). Cross-border tourism helps create a regional identity and facilitates the development of tourist regions (Chaderopa, Citation2013; Izotov & Laine, Citation2013).

The European Union integration process has created more open borders, especially thanks to the Schengen Treaty, while political change has provided for a significant increase in international tourism (Williams & Balazs, Citation2002, p. 79). This is especially evident in border regions where political changes have provoked the cross-borderization of tourism (Więckowski, Citation2010), increasing transfrontier movement and cooperation (Kolosov & Więckowski, Citation2018; Mayer et al., Citation2019; Timothy & Saarinen, Citation2013). Various European Union structural funds operate in strong support of tourism development (Dołzbłasz, Citation2018; Studzieniecki & Meyer, Citation2017; Timothy & Saarinen, Citation2013). International boundaries have significant implications for this, especially in terms of planning, promotion, and taxation (Timothy, Citation2001). The most-recent research in this field is beginning to look more at cross-border governance and marketing (Blasco et al., Citation2014; Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017).

Where tripoints and the neighboring areas in three countries exist, geographic proximity increases possibilities for tourism by creating multinational cross-border spaces. On the one hand, this situation may slightly hinder governance, planning and marketing, which are usually more difficult than in cooperative relationships between two sides only. Thus, for example, only 7% of EU-funded projects are designated for trilateral cooperation in eastern Poland (Dołzbłasz, Citation2018). On the other hand, such a condition may also provide opportunities to increase the collaborative reach by creating tripartite agreements, via Euroregions or European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (e.g. Tritia). So far, much of what has transpired has revolved around nature conservation. The results of tripartite nature-protection efforts are to be seen in Africa (Ramutsindela, Citation2013), but also Eastern Europe – as the home of the world’s first trinational UNESCO Biosphere Reserve – the Eastern Carpathian BR established in 1998 around the tripoint of Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Why tripoints matter

The emerging importance of international tripoints in tourism is illustrated in three main ways. First there is the triple contrast of three countries at one locality. Elements that differentiate individual sides in the vicinity of the tripoint and offer a basis for tourists' interest are primarily language; religion; other cultural traditions, currency, rules and laws; cuisine; consumer products; holidays; and opening hours of shops, banks and other services. Likewise, three countries provide more contrasts than only two countries. In the face of dynamic processes of change and the disappearance of differences between sides, differentiated elements may remain stronger among three countries, and could offer additional elements for marketing purposes.

A second way in which tripoints are important in tourism reflects the strong symbolic significances associated with these places. This kind of development of a tripoint has it regarded as a meeting place with integrated symbols (for tourists, local, regional and national authorities), demonstrable neighborly friendship, and a completely new tourist space with the potential to create a new pole of growth by using the resource present in an otherwise-peripheral area. Demarcation indicators highlight the central point where three borders meet (with special monuments or markers unique to the place; in many locations border signs with number “1” are located at the tripoint) and delineated borderlines in each direction from the central point. There are more markers, interpretive signs and monuments than on regular borders between two countries.

Third, there are several ways in which tripoints possess significant potential as venues for collaborative tourism development and cross-border cooperation over a relatively small geographical area. First, synergies exist through the proximity of three countries together, such as spaces for cultural events and tourist-attraction development. Secondly, tripoint areas may be eligible for larger development grants (EU, national or local) than borders where only two countries meet. Thirdly, tripoints require unique management approaches, in that three countries - rather than just two - must learn to cooperate to avoid tripartite impasses in policies and decision-making. Finally, tourism in these unique situations helps utilize empty borderlands and isolated areas for the purpose of integration and development. It helps induce creation of local growth poles (Perroux, Citation1950) and complementary growth and specialization using EU funds for a shared vision and development needs.

Research methods

The research detailed here is based on the author’s conceptualization of tourism development at tripoints and in their vicinities, over many years of fieldwork. The study illustrates the genesis of the place-making processes, and success stories in Europe’s peripheral tripoints. A multi-perspective, case-study approach has been used to understand the potential of tripoints in the context of Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs).

The research was pursued in six stages. The first stage was a thorough review of the literature, with identification of key factors leading tourism in border areas, as well as the role of tripoints in these relationships. Second, a framework was developed to emphasize the specifics of tourism development at tripoints as an ideographic ‘triangle’ (). Elements related to border attractiveness for tourism were chosen on the basis of a literature review.

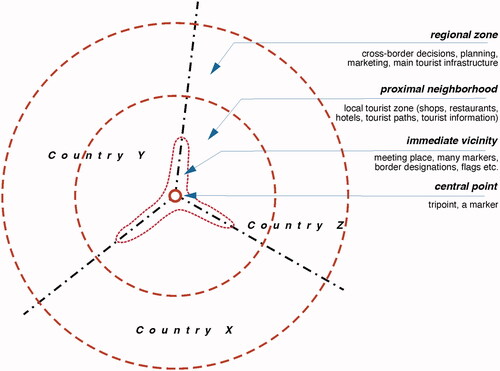

Drawing on the example of Timothy and Gelbman (Citation2015), who examined lodging’s spatial relationships with international borders a similar spatial framework is proposed as follows:

central point - exactly at the point where the borders of three countries meet,

immediate vicinity - up to several dozen meters, along each side of the three borders,

extended neighborhood - the closest extended area in each of the neighboring countries (presumably in the three units of local-government or county-level administration adjacent to the tripoint),

wider region - a broader and more distant area in which cooperation between two or three states usually occurs.

The third stage involved selecting an example of a new tripoint in the European Union on a border between the CEECs (in this case Tricatek in Beskidy – see explanation in the introduction and in the next section). The fourth stage included efforts to amass multi-annual data. Fieldwork took place in the relevant parts of Poland, Slovakia and Czechia over several years, during seven research trips made in April 1996, September 1999, May 2006, August 2009, May 2012, June 2018 and March 2019. Informal discussions and formal in-depth interviews were undertaken with local and regional authorities tourists (informal interviews/discussions with 45 tourists − 15 from each country – in 2018 and 2019) and local residents and entrepreneurs (in 2006, 2018 and 2019). Finally, analysis also extended to more than 30 guides, maps, brochures and webpages, more than 100 local newspapers and 10+ official policy documents from various associations, Euroregions, border regions, joint development projects and regional strategies.

The fifth phase of research entailed analysis of the materials collected to understand the development of use in tourism being made by the tripoint and its surrounding area. In this, the most important elements were as follows (see “Elements of tourism development” in ):

Special location, border changes and checkpoints – historical analysis of cartographic and written materials; information obtained from border guards; and map analysis of cross-border checkpoints.

Delimitation and demarcation. Analysis and mapping of all elements, including locations and distances.

Accessibility. Analysis of car-park locations, and distance in km and time to the main regional and capital cities.

Spatial analysis of tourism development and infrastructure. During fieldwork, inventories of tourism resources and opportunities were taken, and observations made of the development of tourist infrastructure and the behavior of tourists and the local population on visits and during transboundary events. Evidence of other tourism infrastructure was collected and analyzed (see ).

Marketing, meeting place and events. Basic analysis of the content of documents with a view to understanding the role of planning and the use of border resources in the area.

The last stage of research saw the development of the conceptual framework, which summarizes tourism development by reference to characteristics of the tripoint, i.e.:

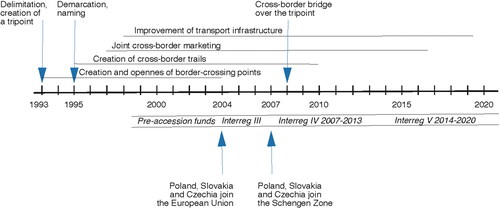

the axium of time (stages) (); (choice of key data and events);

spatio-temporal analysis with scalar dimensions ().

The appearance of a new tripoint in Europe

Special location and border changes

The borders established in Europe following the First and Second World Wars were in many cases located in places different than where they were before the Wars (Kolosov & Więckowski, Citation2018). The most notable shifts were in Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish-Czechoslovak border appeared after WWI, but changed again after WWII when the territory of Poland was ‘shifted’ westward, and its number of neighbors reduced to three (the USSR, East Germany and Czechoslovakia) (Eberhardt, Citation2017; Kolosov & Więckowski, Citation2018). The Polish-Czechoslovakian border was 1292 km long.

Following the collapse of communism in East Germany, the two Germanies were reunited in 1990, but the location of the Germany-Poland-Czechoslovakia tripoint remained unchanged. Further east, the disintegration of the USSR in 1991 resulted in the birth of 15 new sovereign states, including Ukraine. The eastern tripoint remained in the same position. However, with the division of Czechoslovakia into two new sovereign states (the Czech Republic (Czechia) and Slovakia) on January 1, 1993, a new tripoint appeared (Poland-Czech Republic-Slovakia). The actual Polish-Slovak border, and the eastern part of the Polish-Czech border run mainly along the watershed ridges of the Carpathians, the midstreams of rivers (e.g. the Dunajec and Poprad) or the bottoms of valleys/basins.

The Carpathian region is a center of friendly neighborly relations. Nature protection, tourism and transport dominate transfrontier cooperation between Poland, Czechia and Slovakia. The three countries joined the European Union in 2004, and in 2007 implemented the Schengen Agreement on the same day (December 21). This eliminated crossing procedures, which ushered in a new era of passport-free travel between the three countries. Although the location of this tripoint has remained the same for 27 years, it has undergone tremendous geopolitical change.

Delimitation and demarcation

The tripoint at the center of this study is located at the convergence point of three departments (Istebna, Poland; Čierne, Czechia; and Hrčava, Slovakia). It is in the Beskidy Mountains, at an altitude of 545 m above sea level. The delimitation of the new Czech-Slovak border revealed that the precise tripoint is located in a small stream. It was decided that a standard border marker would not be placed at this locality. Instead, a decorative stone obelisk stands near the exact meeting point of the three countries. In 1995, three identical columns were placed surrounding it, each of which stands 2.4 meters tall and each one in a different country, emblazoned with each country’s coat of arms and name. Time capsules were placed inside them containing various commemorative objects, such as documents, newspapers and coins. During the inauguration of the placement of the border stones and the border ‘park’ in 1995, the heads of the local authorities agreed to develop tourism around the tripoint. In later years, tables and picnic areas were built, signs erected, and interpretive information panels put up (). The activity was summed up by a representative of the Polish gmina of Istebna:

We straight away set about cooperating, and there were immediate results: the tripoint is an ideal place for meetings. There was a clear need to mark the border from three sides. We devised a joint map, and came out with guides. We are establishing a zone in which people can spend their free time in a nice way. It’s a chance for us to develop and attract tourists. (Local Authority, Poland, 1999).

Proximity and accessibility

The vicinity of the tripoint offers a good foundation for cross-border cooperation, including the organization of meetings, both for residents and tourists. The three languages are similar but different, which facilitates communication while still maintaining an aura of differentness, which appeals to locals and some out-of-town visitors. Linguistic differences are clearly visible even in the issue of geographical names. The stream where the tripoint is situated has three different names: Wawrzaczowy (in Polish), Kubankowski (in Czech), and Gorylów (in Slovak). The same applies to nearby border villages: Jaworzynka (Poland), Hrčava (Czechia) and Čierne (Slovakia). In addition, each of the three countries uses a different currency (the Polish złoty, the Czech korona and the Euro in Slovakia), but payments in any one of the currencies is accepted in the tripoint zone. Certain differences between countries were emphasized from the beginning as an important attraction. This applied mainly to cuisine and beverages, especially local beers. The tripoint area was promoted as a place where tourists could visit three countries simultaneously, with three currencies, three languages and three different beers to taste.

The tripoint is located a significant distance from major cities and the capitals of each state, emphasizing its peripheral location (2 h 40′ from Prague, 2 h 40′ from Bratislava, and 4 h 42′ from Warsaw). In the 1990s, it was essentially impossible to reach this point for legal and infrastructural reasons. In the 21st century, however, thanks to EU funds for peripheral regions, and transboundary cooperation, the infrastructure has improved dramatically, much reducing travel time to the tripoint from population centers (Więckowski et al., Citation2012). Following significant improvement in accessibility, especially in the vicinity of the tripoint, people can now reach the site by car (1 h 4′ from Ostrava, 1 h from Žilina and 1 h 36′ from Katowice).

Increasing the tourist attractiveness of the tripoint and improving access to it have facilitated the growth of tourist traffic. According to estimates by local tourist offices in the surrounding municipalities, the tripoint is visited annually by over 100,000 people. The largest footfall comes from neighboring provinces (about 70%). In addition, there are short-term movement patterns from neighboring municipalities, and numerous people come to have meetings on the borderline, though estimates for these activities are unavailable. The major tourist centers in the region are shown in .

From “nothing interesting” to tourist attraction and meeting place

Before the division of Czechoslovakia, the current tripoint area was only located on the Polish-Czechoslovak border. It was inaccessible and not considered attractive. Some places in surrounding regions were attractive for tourism but were dominated by domestic tourism in each country (Mika, Citation2008; Riley, Citation2000). Of itself, the appearance of a new border was not yet an important impetus for the development of tourism and recreation. It is only favorable conditions, local-authority enthusiasm and EU funds since that time that have influenced the organized development of leisurescapes at this border juncture.

Opened border checkpoints, new infrastructure and the potential for cross-border cooperation

At the beginning of recent transformations, the most important element was the possibility of crossing the border and the gradual improvement of accessibility and creation of new tourist routes. In 1993, after the formation of the tripoint, it was actually illegal to cross the border in its vicinity. The nearest border crossings were approximately 15-20 km distant from it (see Więckowski et al., Citation2012). However, in subsequent years, five new border crossings were opened.

The first period of cooperation was supported by bottom-up initiatives, which resulted in the formation of associations and organizations. In the 1990s, the lack of financial resources and weak capital of local entrepreneurs did not allow for greater investment and development. It was limited only to relatively cheap activities, such as the organization of meetings for tourists, authorities and residents, and the designation of simple tourist routes. In November 1999, the Association for the Development of Regional Cooperation of Olza - Euroregion Śląsk Cieszyński supported and implemented the first cross-border bicycle routes (e.g. one called the ’Meeting point of three borders’, which is 25 km long; another is 40 km long - ‘Around the tripoint in the wake of Gary Fisher’), as well as picnic tables, benches, cycle trails and information materials (Więckowski et al., Citation2012).

The inclusion of the area into the European Union (2004) and the possibility of applying for EU funds thus became a major stimulus for tourism development. In 2004, the Tripoint Development Programme started as a grassroots initiative between the three neighboring municipalities. It consists of local authorities, community groups and business associations from the three countries (in Poland - the Gmina of Istebna, county of Cieszyn and Olza Association for Regional Development and Cooperation; in Slovakia - the Kysucki Triangle: Čierne, Skalité and Svrčinovec; in Czechia - the Union of Jablunkov Communities, Hrčava and Bukovec). This established cooperation brings tangible effects. The basic road and tourist infrastructure, such as pedestrian paths, Nordic walking routes, bicycle routes, road paving and lighting and accompanying outdoor facilities (e.g. a tourist shelter, a roofed rest spot with a fireplace) was built during the INTERREG IIIA (2004–2006), INTERREG IVA (2007–2013) and INTERREG VA (2014–2020) phases. In 2007–2008, as part of cooperation between the Association of Municipalities of Jablunkov, Istebna and Čierne, the Polish and Slovak riverbanks along the tripoint were connected by an 18-meter wood bridge, while the depression on the Polish-Czech border was linked with a smaller bridge:

the place works well – there are many tourist trails and it’s possible to be in any of the three countries quickly, on foot or by bike. The new roads are now being built. (Regional Authority, Slovakia, 2012).

A souvenir shop with maps and regional cheese from Koniaków was built on the Polish side and another on the Czech side (with local products like cheese and beers). Later, a bar next to the tripoint (where local products, meals and beer from each of the three countries are served) and a ‘Tripoint guesthouse’ were established, this also making clear how the tripoint is used in branding and promotion. The owners of the Tripoint Inn (or pensjonat Trójstyk), situated 500 meters from the tripoint have an establishment that incorporates the border, and especially the tripoint itself, into its name and advertising. Admittedly, they were able to profit from the location as long ago as in the 1990s.

As can be imagined, a consequence of the installation of new infrastructure and tourism facilities is far-reaching change in the vicinity of the tripoint. The particular elements involved are shown in .

Marketing, a meeting place, events and future plans

The promotion of a new product has added to this cross-border region’s tourism assets. In a joint promotional effort, a single map in English, Czech and Polish was published, in contrast to the previous three different maps published individually by the Polish, Czech and Slovak sides. The new map contains descriptions of tourist attractions, routes, tracks and events. A common tri-national webpage has also been created, as well as many tourist brochures, booklets and leaflets. Transfrontier meetings have increased through various sports, cultural events, and other happenings, which highlight different dimensions of cross-border tourism. These are usually connected with the cooperative pursuit of projects or micro-projects funded by EU INTERREG IV and V’s cross-border cooperation programmes (through the Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion). Over more than a decade 20+ large events were organized:

The meetings are of ever-greater significance, and that includes the church masses. The Polish side now organizes masses for the three nations every year. (Local Authority, Czechia, 2018).

The tripoint is also promoted on an international scale and has been highlighted as a model of success (Więckowski et al., Citation2012). Tourists have similar opinions:

The place has its potential thanks to the out-of-the-ordinary location where the borders of Poland, Czechia and Slovakia meet. It can be thought of as a kind of special curiosity. It’s a super feeling to move from country to country, and kids in particular have fun with that. (Czech tourist, 2018).

The tripoint has assumed further significance in its region, given that it has become a recognizable attraction. The hotel owners have noted this fact:

It’s an interesting place we can send our guests to when they are looking for something unusual in the region (Hotel owner, Poland, 2019).

There are ongoing plans to build new infrastructure at the tripoint, including a three-country bridge that would connect all three states over the exact tripoint. The architectural design was completed in 2016. The EU’s new Financial Perspective for 2021–2027 would offer a new financial impulse, as based on sound analysis of the opportunities for – and objectives ascribed to – future cooperation.

The future development of the tripoint is now in need of a professional destination management plan, with four elements to be seen as most important. First, in the nearest future, the need is to draw up a new plan for the area’s development, with account taken of different concentric zones out from the actual tripoint itself (e.g. as proposed here), with tasks and specializations assigned to the three countries, and of course with new funding from the EU taken account of. Second, there is a need for the system of tourist trails to be planned anew (given that these ought to bear the specific nature of the border in mind, and in fact make better use of the actual borderline, as a natural place to run new trails). Third, there should be better marketing and well-coordinated promotion of this as a destination. Without these elements, the tripoint may cease to operate as a tourist product, all the more so as it is mainly significant in the context of a stay lasting a couple of hours. Fourth, it is recommended that there be constant (annual or at most 3-yearly) augmentation of the tourist attraction, so that new tourists can still be attracted, but former visitors also attracted back. Ideas that would fit this bill include those referred to, i.e. the three-way bridge meeting directly above the tripoint itself and the garden of Carpathian plants, as well as a joint viewing platform (of the kind present where The Netherlands, Germany and Belgium meet), a Museum of Borders and Integration, and an original play area for children with unique features of some kind.

The development of tourism at tripoints in general can be modeled ideographically to include the process of a tripoint transforming into a tourism asset or product ().

Discussion and conclusions

Border areas are laboratories of socio-economic development and international cooperation at a very local, yet international, scale. Because tourism plays a crucial role in borderlands (Timothy, Citation2001; Timothy et al., Citation2016), the first question in this research was “where and why do borders provide a basis for the development of tourism? What spatial forms do they take?”. The research question answered in this paper shows that borders have strong symbolic meanings and can function as tourist attractions. The opening of borders and the additional funding poured into them have created opportunities to cooperate and create new tourism spaces. Tripoints are simultaneously unique border attractions that reveal contrasts between the three sides. In understanding the spatial aspects of new tourist spaces surrounding tripoints, each zone is important and should engage in cooperation in line with the fact that a common central point is present. The tripoint examined here allows us to propose a spatial planning model for the area’s use in tourism ().

The central point has symbolic meaning and may be important in both closed- and open-border areas, with the point taking on the role of connecter or integrater. In the case of Beskidy, this is marked with a small stone, a nearby bridge and now a planned new three-way bridge, over the point connecting the immediate recreational spaces around the border point.

The immediate vicinity is a zone where trinationalism and individual nationalism abound simultaneously. The tripoint is commemorated with signs, intermingled with national emblems suggesting that, even though someone is standing in a trinational area, he/she is still also standing in country X, Y or Z. In the case of Beskidy, there are three monolithic stone markers surrounding the tripoint, as well as actual border markers, posts, flags, emblems, information boards and interpretive signs (most of all on the Slovakian side). In this space there are official border crossings or other possibilities to cross, tourist trails/routes, bridges, and some basic recreational infrastructure. This zone is a place for meetings and leisure activities, such as picnics, family outings, and organized events for the local population and tourists.

While the space is developed evenly on all three sides, the Czech side does for example have the small restaurant with the large shelter, while the Polish has a large space for meetings (the main venue for any events), a hotel that is building, and – on the Polish-Czech border itself – two sidewalks leading from the parking lot (one with steps and one for the disabled and cyclists). On the Slovakian side, there is small-scale infrastructure like shelters and a place to locate a grill.

The proximal neighborhood (or local zone) is a service precinct and access area to the tripoint. Access in this sense includes infrastructure and some transport connections, as well as parking lots and tourist routes. There are both accommodation and food facilities, as well as accompanying services, such as souvenir shops (especially those in the immediate vicinity of the tripoint – with cheeses and souvenirs, both on the Czech and Polish sides), tourist trails, shelters, and tourist information. On this spatial scale, a joint marketing area may be established. Municipalities in this area cooperate in marketing, branding and planning for border-related tourism; and create associations, or form part of larger units whose purpose is to promote tourism in the area, such as through the design and dispersal of promotional materials. The local zone also has the potential to obtain funding for small-scale cross-border developments, and it is thanks to this that infrastructure in the form of roads, trails and parking lots made their appearance. The key point is the possibility of the investment risk being divided by three.

The regional zone uses the main slogan of the meeting point of three countries to develop a tourism edge. It is within the region that planning, management and marketing are carried out. In the European Union, it may be subject to additional management under Euroregion legislation - the Beskidy and Cieszyn-Silesia Euroregions, and today also the Tritia European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (Kurowska-Pysz, Citation2016). The transboundary region forms a singular regional entity, where information (e.g. in guidebooks, maps, brochures and websites) is shared, and many cooperative efforts exist (e.g. in conservation, fire services and staff training). This broader region is also a tourist base and is closer to larger tourist markets, where accessing the tripoint can be part of the appeal of visiting. This area is characterized by larger tourist trails, auto routes, other attractions and higher-order infrastructure, such as railway stations or bus depots.

The second research question(s) “how are the border resources of tripoints transformed into tourism assets, which elements are used in tourism, and how do they function in reality?” led to the development of a conceptual understanding of the role of four overarching types of borderland attractivity where the development of tourism is concerned. Tripoints are a unique element of the general concept of borders and tourism, which can be considered to relate to peripherality, differences, the borderline and cross-border space.

Peripherality is very often ‘the initial state’ of border areas with their natural potential for tourism development (Christaller, Citation1964; Timothy, Citation2001). Peripherality from a development perspective means that many border environments remain natural or original, marginal cultural resources, which can lend tripoints an additional level of appeal. On the other hand, many tripoints (including the Beskid example) are located far from the center of the country, and from major cities, resulting in accessibility and transportation challenges. At the same time, the Beskidy tripoint exemplifies the way in which such a disadvantage might be overcome, and a local pole of growth put in place (Perroux, Citation1950), also in association with important symbolic significance for each country involved.

Differences between the three sides represent an incentive to travel, as ‘otherness’ prevails (Timothy, Citation2001). Sometimes these differences are used as unique selling propositions in marketing and branding, as in the case of the Beskids, in which the originality of three countries, three languages, three currencies and three beers is underlined. Maintaining and exploiting differences (especially to the benefit of shopping and culinary diversity) is essential in the first phases of tourism development (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2010).

The borderline with border markers, tripoint monuments, and additional elements such as eateries, information boards and flags together represent important elements of the totality of the tripoint tourismscape. For some people, the idea of setting foot in another country or straddling the borders of three countries at once while posing for a photo, is rather appealing (Ryden, Citation1993; Timothy, Citation2001). The borderline itself is a resource (Löytynoja, Citation2008; Sohn, Citation2014), as well as a type of heritage monument (Prokkola, Citation2010), that can provide a unique regional heritage narrative (Gelbman & Timothy, Citation2010; Timothy et al., Citation2016). Tripoints are a curiosity and a symbol of cooperation, in Europe at least. They may also serve as potentially attractive border localities, with one common point and three departing boundary lines fanning out from it – each with its own markings, histories and narrations.

Creating a common cross-border tourism space (Kałuski, Citation2006; Mayer et al., Citation2019), including border crossings and tourist trails, the use of EU funds, joint planning policies, marketing and the development of promotional materials, including websites, are of high importance. Tripoints provide opportunities to create a common tourism space and have the potential to facilitate cross-border planning, as was demonstrated in research by Blasco et al. (Citation2014), Timothy and Saarinen (Citation2013) and Dołzbłasz (Citation2018). The synergy effect ensures additional support for an area when it comes to attracting tourists – with more opportunities, attractions and resources where the generation of tourist products is concerned. ‘Soft’ region-building refers to a symbolic breaking-down of administrative obstacles, with mental borders dissolved and a shared mindset facilitated (Stoffelen, Citation2018).

Such cross-border potential of a tripoint is based around the overarching elements of peripheral location, as well as asymmetrical differences and the joint use of local resources (Sohn, Citation2014). These are factors to cooperation with the aim of creating a common tourist product that are visible in the case of tripoints. At the earliest phase of development, the border and its tripoints are not a tourist attraction. The Polish-Czechoslovakian border was a truly peripheral location. But in 1993, Czechoslovakia was divided and a tripoint was established. The border’s definition and delimitation, as the first two stages of border formation (Jones, Citation1945; Timothy, Citation2001) took place two years later. The tripoint spot was isolated and barely accessible, and it was virtually impossible to cross national borders away from official ports of entry.

In the process of demarcation, as the third step to border formation (Jones, Citation1945), a willingness to cooperate across the common borders appeared, and the idea of a new tourist attraction began to grow. The erection of obelisks around the triangular centerpoint was symbolic. The designation of the area as a recreational asset, naming (as an important element highlighted by Löytynoja, Citation2008), and the creation of tourist information and a webpage soon followed. The most important factor, however, was the opening of the border for crossing at any location along it, following on from the three countries’ implementation of the Schengen Agreement in 2007 (see Więckowski, Citation2018).

It was from these initial actions that longer-term actions followed, including the founding of tourist cycling and walking trails. Limited capital restricted the extent of what could be done in terms of physical tourism development, but the organization of events for tourists and local communities from all three countries constituted an inexpensive and key opportunity for tourism development. Tourists were attracted to the area on the basis of the “otherness” of the three states, especially as regards food products, beer and cuisine.

However, at the end of the 1990s, attempts were first made to create a common brand and image, and establish a transfrontier governance body that would facilitate planning, development and cooperation – as has been done in other parts of Europe (Stoffelen et al., Citation2017). The growing tourism potential related to tripoint borders, such as building guesthouses, car and hiking routes, joint marketing and planning (necessary to use funds from various EU programs), and additional infrastructure was made possible through EU funds, which recognized the potential for this peripheral manifestation of tourism (Więckowski et al., Citation2012), similar to other EU border regions (e.g. Blasco et al., Citation2014; Dołzbłasz, Citation2018).

Additionally, where governments embrace cooperation along their borders, tourism flows can be facilitated (Sofield, Citation2006). In the process of European integration, tripoints became more accessible and have therefore started to assume the role of distinctive tourist attractions; and later symbolic places or regions of European integration – sometimes with a stronger brand than the borders themselves (Kałuski, Citation2006). This is particularly evident at Germany’s tripoints – with The Netherlands and Belgium (Timothy et al., Citation2014), between Belgium and Luxembourg, and later between Luxembourg and France (Sohn et al., Citation2009) and Switzerland and France (Leimgruber, Citation1998; Reitel, Citation2013).

The author is aware that one case study is not enough of a basis for generalizations. Other special points on borders and tripoints in other regions should be researched to generate both general remarks and an answer regarding those border resources that are important and successful in tourism development. The paper confirms the need for further research and observation, especially over longer periods of time. Some researchers advocate more systematic research on border-related tourism in European contexts, with the aim of understanding better the unique management requirements of these tourism localities (Timothy et al., Citation2016; Mayer et al., Citation2019), along with the multi-scalar cross-border power dynamics operating in tourism and cross-border cooperation (Stoffelen, Citation2018; Stoffelen et al., Citation2017).

But the Beskidy tripoint at which the borders of Poland, Czechia and Slovakia meet (whose tourism slogan is ‘taste three beers in three countries’) offers a good example of more-profound border changes taking place in the EU, the creativity of local authorities supported by European funds, and the creation of new transboundary meeting space with a strong integration identity. It also exemplifies new tourist space away from traditional tourist destinations, as well as the development of a new kind of attraction. Tripoints as emerging tourist attractions have appeared in new marketing materials and have the potential to become unique border attractions at the regional and international levels. The future will tell whether tourists’ interest in tripoints is a temporary fad, a short-term opportunity to receive EU funds, or a more permanent trend.

Acknowledgments

The Author wishes to thank Professor Stefan Kałuski for the inspiration, Professor Dallen Timothy for his tremendous help and encouragement, and the anonymous Reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marek Więckowski

Marek Więckowski is the Professor at the Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization of the Polish Academy of Sciences. He is the Vice-Chairman of the Scientific Council at this institute and the editor-in-chief of the Geographia Polonica. He is a member of the IGU Commission for the Geography of Tourism, Recreation and Global Change (2012-2020). His field of research is political geography (borders, cross-border collaboration), tourism geography, transport geography (accessibility) and territorial marketing.

References

- Banfi, S., Filippini, M., & Hunt, L. C. (2005). Fuel tourism in border regions: The case of Switzerland. Energy Economics, 27(5), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2005.04.006

- Birkeland, I. J. (2002). Stories from the north. Travel as place-making in the context of modern holiday travel to North Cape, Norway. Institut for Sosiologi og Samfunnsgeografi, Universitetet i Oslo.

- Blasco, D., Guia, J., & Prats, L. (2014). Emergence of governance in cross-border destinations. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 159– 173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.09.002

- Chaderopa, C. (2013). Cross-border cooperation in transboundary conservation-development initiatives in southern Africa: The role of borders of the mind. Tourism Management, 39, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.04.003

- Christaller, W. (1964). Some considerations of tourism location in Europe: The peripheral regions- under developed countries-recreation areas. Papers of the Regional Science Association, 12(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01941243

- Di Matteo, L., & Di Matteo, R. (1996). An analysis of Canadian cross-border travel. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(1), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00038-0

- Dołzbłasz, S. (2018). A network approach to transborder cooperation studies as exemplified by Poland’s eastern border. Geographia Polonica, 91(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0091

- Eberhardt, P. (2017). Political and administrative boundaries of the German state in the 20th century. Geographia Polonica, 90(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0095

- Gelbman, A., & Timothy, D. J. (2010). From hostile boundaries to tourist attractions. Current Issues in Tourism, 13 (3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903033278

- Gelbman, A., & Timothy, D. J. (2011). Border complexity, tourism and international exclaves: A case study. Annals of Tourism Research, 38 (1), 110–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2010.06.002

- Herrschel, T. (2011). Borders in post-socialist Europe: Territory, scale, society. Ashgate.

- Ioannides, D., Nielsen, P., & Billing, P. (2006). Transboundary collaboration in tourism: The case of the Bothian Arc. Tourism Geographies, 8(2), 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600585380

- Izotov, A., & Laine, J. (2013). Constructing (un)familiarity: Role of tourism in identity and region building at the Finnish-Russian border. European Planning Studies, 21(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.716241

- Jacobsen, J. K. S. (1997). The making of an attraction: The case of North Cape. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80005-9

- Jones, S. B. (1945). Boundary making. Carnegie Endowment.

- Kałuski, S. (2006). Border tripoints as transborder cooperation regions in Central and Eastern Europe. In J. Kitowski (Ed.), Regional trans-border co-operation in countries of Central and Eastern Europe - a balance of achievements (Vol. 14, pp. 27–36). Geopolitical Studies.

- Kolosov, V., & Morachevskaya, K. (2020). The role of an open border in the development of peripheral border regions: The case of Russian-Belarusian borderland. Journal of Borderlands Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1806095

- Kolosov, V., & Więckowski, M. (2018). Border changes in Central and Eastern Europe: An introduction. Geographia Polonica, 91(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0106

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. (2016). Opportunities for cross-border entrepreneurship development in a cluster model exemplified by the Polish–Czech border region. Sustainability, 8(3), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030230

- Leimgruber, W. (1998). Defying political boundaries: Transborder tourism in a regional context. Visions in Leisure and Business, 17(3), 8–29.

- Leimgruber, W. (2005). Boundaries and transborder relations, or the hole in the prison wall. GeoJournal, 64(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-006-7185-6

- Löytynoja, T. (2008). The development of specific locations into tourist attractions: Cases from Northern Europe. Fennia, 186(1), 15–29.

- Mayer, M., Zbaraszewski, W., Pieńkowski, D., Gach, G., & Gernert, J. (2019). Barrier effects of the Polish-German border on tourism and recreation: The case of protected areas. An introduction. In Cross-border tourism in protected areas. Geographies of tourism and global change (pp. 1–17). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05961-3_1

- Mika, M. (2008). Tourism on the Polish–Czech–Slovak borderland in the light of contemporary development trends. In J. Wyrzykowski (Ed.), Conditions of the foreign tourist development in Central and Eastern Europe, Tourism in geographical environment (Vol. 10, pp. 325–334). Uniwersytet Wrocławski.

- Perroux, F. (1950). Economic space: Theory and applications. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/1881960

- Pretes, M. (1995). Postmodern tourism. The Santa Claus industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00026-O

- Prokkola, E.-K. (2007). Cross-border regionalization and tourism development at the Swedish-Finnish border: ‘Destination Arctic Circle’. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7 (2), 120–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250701226022

- Prokkola, E.-K. (2010). Borders in tourism: The transformation of the Swedish–Finnish border landscape. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500902990528

- Prokkola, E.-K., & Lois, M. (2016). Scalar politics of border heritage: An examination of the EU’s northern and southern border areas. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(sup1), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1244505

- Raffestin, C. (1986). Eléments pour une théorie de la frontière. Diogène, 134, 3–21.

- Ramutsindela, M. (2013). Experienced regions and borders: The challenge for transactional approaches. Regional Studies, 47(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2011.618121

- Reitel, B. (2013). Border temporality and space integration in the European transborder agglomeration of Basel. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 28(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2013.854657

- Rietveld, P., Bruinsma, F. R., & van Vuuren, D. J. (2001). Spatial graduation of fuel taxes: Consequences for crossborder and domestic fuelling. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 35(5), 433–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-8564(00)00002-1

- Riley, R. (2000). Embeddedness and the tourism industry in the Polish southern uplands: Social processes as an explanatory framework. European Urban and Regional Studies, 7(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977640000700301

- Ryden, K. C. (1993). Mapping the invisible landscape: Folklore, writing and the sense of place. University of Iowa Press.

- Saarinen, J. (2004). Destinations in change: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tourist Studies, 4(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604054381

- Scott, J. (2012). European politics of borders, border symbolism and cross-border cooperation. In T. Wilson & H. Donnan (Eds.), A companion to border studies (pp 83–99). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sofield, T. H. B. (2006). Border tourism and border communities: An overview. Tourism Geographies, 8(2), 102–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680600585489

- Sohn, C. (2014). The border as a resource in the global urban space: A contribution to the cross-border metropolis hypothesis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(5), 1697–1608. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12071

- Sohn, C., Reitel, B., & Walther, O. (2009). Cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: The case of Luxembourg, Basel, and Geneva. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(5), 922–939. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0893r

- Stoffelen, A. (2018). Tourism trails as tools for cross-border integration: A best practice case study of the Vennbahn Cycle Route. Annals of Tourism Research, 73, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.09.008

- Stoffelen, A., Ioannides, D., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Obstacles to achieving cross-border tourism governance: A multi-scalar approach focusing on the German-Czech borderlands. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.03.003

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Studzieniecki, T., & Meyer, B. (2017). The programming of tourism development in Polish cross-border areas during the 2007-2013 period. In 6th Central European Conference in Regional Science – CERS (pp. 506–516).

- Szytniewski, B. B., Spierings, B., & van der Velde, M. (2017). Socio-cultural proximity, daily life and shopping tourism in the Dutch–German border region. Tourism Geographies, 19(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1233289

- Timothy, D. J., & Gelbman, A. (2015). Tourist lodging, spatial relations, and the cultural heritage of borderlands. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 10(2), 202– 211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2014.985227

- Timothy, D. J. (1995). Political boundaries and tourism: Borders as tourist attractions. Tourism Management, 16(7), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00070-5

- Timothy, D. J. (2001). Tourism and political boundaries. Routledge.

- Timothy, D. J., & Butler, R. W. (1995). Cross-border shopping: A North American perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00052-T

- Timothy, D. J., Guia, J., & Berthet, N. (2014). Tourism as a catalyst for changing boundaries and territorial sovereignty at an international border. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.712098

- Timothy, D. J., & Saarinen, J. (2013). Cross-border cooperation and tourism in Europe. In C. Costa, E. Panyik, & D. Buhalis (Eds.), Trends in European tourism planning and organization. 64-74. Channel View Publications.

- Timothy, D. J., Saarinen, J., & Viken, A. (2016). Tourism issues and international borders in the Nordic Region. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(sup1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1244504

- Van der Velde, M., & Spierings, B. (2010). Consumer mobility and the communication of difference: Reflecting on cross-border shopping practices and experiences in the Dutch-German borderland. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 25(3–4), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2010.9695781

- van Houtum, H., & van Naerssen, T. (2002). Bordering, ordering and othering. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 93(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00189

- Weidenfeld, A. (2013). Tourism and cross border regional innovation systems. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.01.003

- Więckowski, M. (2010). Tourism development in the borderlands of Poland. Geographia Polonica, 83(2), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.2010.2.5

- Więckowski, M. (2018). From periphery and the doubled national trails to the cross-border thematic trails. New cross-border tourism in Poland. In D. Müller & M. Więckowski (Eds.), Tourism in transitions: Recovering decline, managing change (pp. 173–186). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64325-0_10

- Więckowski, M., Michniak, D., Bednarek-Szczepańska, M., Chrenka, B., Ira, V., Komornicki, T., Rosik, P., Stępniak, M., Székely, V., Śleszyński, P., Świątek, D., & Wiśniewski, R. (2012). Polish-Slovak borderland: Transport accessibility and tourism (Vol. 234). Prace Geograficzne, IGiPZ PAN.

- Williams, A., & Balazs, V. (2002). The Czech and Slovak republics: Conceptual issues in the economic analysis of tourism in transition. Tourism Management, 23(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(01)00061-9