Abstract

External tourism development organizations are frequently utilized by the various levels of the Chinese government to develop tourism and boost local economies. However, this often occurs with limited community participation. We explore the role of institutional arrangements in how people within host communities are empowered and disempowered in such situations by looking into the experiences of Fenghuang Ancient Town and two Miao villages in Hunan Province, China. In-depth interviews, participant and non-participant observation, and document analysis were undertaken. Certain community members were empowered by tourism development, especially financially. However, top-down decision-making, local elite systems, cultural habits and responses to these challenges enabled power inequality. This inequality occurred between government, tourism developer and communities, and within the communities. Only through devolution of power can social impacts from tourism development be improved but, even then, local power imbalances may influence the equity of tourism-related outcomes.

摘要

国各级政府经常引入当地社区以外的旅游开发组织, 发展旅游业, 振兴当地经济。这种做法在拥有独特文化或风景, 但缺少成功旅游目的地所需的人力和经济资本、旅游相关技能和经验的贫困民族地区尤其普遍。在这些情况下, 旅游安排由政府和外部旅游开发商共同组织, 尽管政府部门对旅游发展有不同形式制度干预, 但当地社区通常只进行有限的参与。本文以湖南凤凰古镇和两个苗族村落(早岗和老家)为例, 运用深度访谈、参与和非参与观察以及文件分析, 探讨了制度安排在旅游赋予居民权力和剥夺居民权力过程中的作用。我们发现, 即使东道国社区的某些成员在某种程度上获得了旅游发展的赋权, 尤其是在经济方面的赋权, 但旅游业也有剥夺社区权利等负面的社会影响。问题在于:(1)制度安排中存在裙带关系和偏袒; (2)东道国社区内许多人参与不足, 议价能力有限; (3)当地社区的社会凝聚力较低。这种情况不仅加剧了政府、旅游开发商和社区之间的权力不平衡, 也加剧了社区成员之间的权力不平衡。只有通过将权力从政府和外部开发商有效地下放到当地少数民族人民身上, 才能赋予当地社区权力, 但即便如此, 地方层面的权力关系也可能影响旅游相关结果的公平性。本文通过讨论旅游发展中产生的赋权与失权的对立过程, 为将旅游作为一种发展战略的社区提供建议。

1. Introduction

Around the world, tourism is employed by governments as a development strategy to reduce poverty and promote regional development (McCombes et al., Citation2015; Stoffelen et al., Citation2020). In China, to reduce poverty in ethnic villages that are characterized by unique cultures or scenery, the various levels of government are increasingly turning to ethnic or cultural tourism, changing these rural villages into tourist attractions for urban residents who desire to escape the hustle of their daily life (Yang et al., Citation2006). Agriculture had previously been the economic basis of these ethnic villages, which often struggled with poor facilities and limited accessibility. It was difficult for villagers to develop tourism by themselves due to their lack of experience, skills and funding. Therefore, the various levels of the Chinese government have been bringing in external tourism organizations to develop and run tourism in rural villages. Given that attracting external capital is one criterion by which the performance of government officials is evaluated (Chen et al., Citation2020), typically the government officials take the side of the tourism developer rather than protect the interests of the local community (Li, Citation2006). In some cases, the involvement of external tourism developers can lead to community empowerment (Chen et al., Citation2017). However, other cases show that local communities are marginalized in decision-making and/or lose control over local resources (Han et al., Citation2014; Weng & Peng, Citation2014). As tourism is generally organized in a top-down manner, especially when an external lead partner is brought in, an unbalanced relationship usually exists between the tourism developer, the villagers, and local elites (Yang & Wall, Citation2008).

The purpose of this paper is to assess how different institutional arrangements between government, tourism developer, and villagers in ethnic tourism areas in China influence the processes of empowerment and disempowerment of and within local communities. We understand institutional arrangements to be the formal rules, regulations and governance relations that shape tourism development processes, as well as the informal dynamics that influence how different people and groups within society perceive, respond to, and are (dis)empowered by the formal decision-making structures (Badola et al., Citation2018). With our focus on institutional arrangements, we contribute to the tourism literature by zooming in on what happens in Chinese ethnic tourism areas, and by discussing the various institutional pathways that mediate the power structures between government, tourism developer, and people within local communities.

This paper takes one Ancient Town and two Miao villages in Hunan Province, China, as case studies. The Miao minority group has its own culture, language, festivals, costumes and religious beliefs (Henderson et al., Citation2009; Shi et al., Citation2019). The Miao, especially in rural areas, tend to maintain a relatively traditional life, and therefore tend to experience long-term poverty (Su & Sun, Citation2020). Tourism development will create change, potentially bringing economic development, but will also bring changes to their society and culture. We trace how formal and informal arrangements and dynamics shape ethnic tourism development in these places and establish power imbalances between different stakeholder groups, including within the communities themselves.

2. Empowerment and disempowerment in a tourism context

The concept of empowerment appears in many disciplines, but is especially prevalent in development studies (Craig & Mayo, Citation1995). Various scholars have considered the role of power in discussions around empowerment. As commonly understood, power is the ability – i.e. the skills and resources – of an actor (e.g., person, social group or local community) to make decisions and determine their own affairs, regardless of the actions of other actors (Sofield, Citation2003). From an institutional perspective, power only comes into play when the relative position of an actor in a network of actors influences whether their skills and resources will be used (Jacobsen & Cohen, Citation1986). In this sense, powerlessness denotes the inability of someone to get access to and mobilize resources or decision-making. A common but basic definition of empowerment relates to the capacity of ‘people, organizations, and communities to gain mastery over their affairs’ (Rappaport, Citation1987, p.122). Scheyvens (Citation2002) added the institutional perspective on power to this definition by arguing that empowerment is about the process of creating change in the power balance between actors, for example shifting from the powerful to the powerless, and from the dominant to the dependent.

The multidimensional character of empowerment processes in tourism has been widely documented. Scheyvens (Citation1999) concluded that empowerment should be economic, psychological, social, and political. Economic empowerment in tourism refers to situations where there are lasting economic gains in the community from tourism, while economic disempowerment happens when most of the benefits flow outside the tourism destination. Psychological empowerment occurs when the self-esteem, pride and confidence of the residents of the host community are improved because of the validation from tourists, which endows the community members with a sense of significance. When community members are plagued by the feelings of confusion, disillusionment and frustration, tourism turns out to disempower the community. Social empowerment occurs when tourism enhances local community cohesion and community development activities are established. Political empowerment in tourism means that local community concerns about tourism development are heard and the people themselves become part of the decision-making process, which, in line with the definition of power given above, requires an appropriate power structure and effective agencies that enable community members to express their opinions. The various dimensions of empowerment are intertwined (O’Hara & Clement, Citation2018; Scheyvens, Citation1999, Citation2000).

It is generally argued that sustainable tourism development can only occur when there is widespread empowerment within communities (Park & Kim, Citation2016; Sofield, Citation2003; Stoffelen et al., Citation2020). There is evidence that tourism can contribute to the empowerment of and within local communities (Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Cole, Citation2006; Schmidt & Uriely, Citation2019; Timothy, Citation2007). For example, Su et al. (Citation2020) used the Hui minority in China to illustrate that, not only did tourism empower Hui women economically, it also promoted political, social, psychological and educational empowerment.

Within the tourism literature, community participation is generally considered to be an effective pathway to achieve empowerment within the community (Butler, Citation2017; Dolezal & Novelli, Citation2020; Li, Citation2006; Sofield, Citation2003). However, there are several obstacles to realizing meaningful participation. Xu et al. (Citation2019) argued that institutional change was needed to improve decision-making and community participation in order to increase the equitability of benefits associated with tourism; something which is not straightforward. Furthermore, apart from residents’ relative position in the decision-making network, their lack of interest, awareness, confidence, and disparities in skills limit the inclusiveness of the participation processes (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017; Stoffelen et al., Citation2020). Consequently, although an objective of tourism might be to empower the local community as a whole, it sometimes fails to do this (Schmidt & Uriely, Citation2019). While Tosun (Citation2006) suggested that NGOs may be helpful in empowering and engaging communities in tourism development, others (e.g. Stone, Citation2015) have found that NGO interventions can lead to dependency and the (perceived) domination of outsider priorities. Moreover, unskilled community leaders, a lack of knowledge, and limited economic resources can result in a disempowered community, even if individuals have a strong will to participate in tourism ventures (Ramos & Prideaux, Citation2014). Consequently, within the empowerment debate, care should be taken to not consider communities as cohesive units. Within-community power relations may be at the basis of inequitable outcomes of certain development projects (Prenzel & Vanclay, Citation2014). Finally, disempowered individuals still have agency to react and respond, which can be manifested through minor friction or fierce conflict (Hanna et al., Citation2016; Sofield, Citation2003). Previous research in Miao villages in China has revealed that villagers often utilize daily resistance tactics such as sabotage, roadblocks and squatting, especially when they feel disempowered (Feng, Citation2015).

In historic Chinese villages, the failure to realize community empowerment has mainly been because of the lack of effectiveness of mechanisms to protect the public interest, as well as the unequal power relationship between Village Committees and villagers; hence, also power imbalances within the community (Weng & Peng, Citation2014). Furthermore, villagers and tourism developers may end up in conflict because of a lack of clarity in rural areas who has the right to change land uses (Lo et al., Citation2019; Michaud, Citation2009). The process of attracting investment and investment-based performance assessment, together with weak supervision, have regularly resulted in the failure to achieve original good intentions (Han et al., Citation2014). The lack of economic resources and social support by residents, as well as the strong networks of the political and economic elites, restrict the participation of local people in tourism activities. However, in recent years, villagers in China have generally been gaining more control over their own affairs, for example now having the ability to vote for a Village Head (Xu et al., Citation2014).

As is evident from our literature review, the processes by which tourism contributes to the empowerment and disempowerment of host communities has been much discussed, including in a Chinese context. However, this paper gives greater consideration to the specific institutional arrangements by which communities are empowered and disempowered, in particular regarding the connections between the government and external tourism developers.

3. Description of study area and methodology

3.1. Background information

To compare the processes leading to empowerment and disempowerment in Chinese ethnic villages under different institutional arrangements, we chose a multiple case study design. We selected one Ancient Town (Fenghuang) and two villages (Zaogang and Laojia) in Hunan Province, China, as the study cases. All three cases used to be poor agricultural villages, and tourism has created significant impacts. In each situation, tourism was largely organized in a top-down manner, with local communities excluded from decision-making. However, different forms of institutional intervention were applied in each village.

The three locations are all in the Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Fenghuang County, Hunan Province. This mountainous region is economically disadvantaged. The residents are mostly from the Tujia or Miao ethnic minorities, which constitute 77% of the local population.

Fenghuang Ancient Town is located within the Municipality of Tuo River Town, where the county government is located. Although Fenghuang Ancient Town is renowned as one of the most beautiful small towns in China with a fascinating ethnic architecture (Yu, Citation2015), before the government brought in an external private tourism developer in 2001, tourism only developed slowly. As a result of the joint promotion by the local government and the external tourism developer, tourists have now flocked to Fenghuang Ancient Town, making it a popular national tourism destination (Statistical Communiqué of Fenghuang County, Citation2019).

Zaogang and Laojia are less popular than Fenghuang. Because there is no overnight accommodation available in these two villages, tourists stay in the Ancient Town and, depending on the visitors’ wishes, participate in day tours in the surrounding area. Zaogang and Laojia are located within Shanjiang Town, about 20 kilometers from Tuo River Town. Tourism started in Zaogang in 2006, and in Laojia in 2011. Subsequently, the government purchased 51% of the shares of the private company and founded the Ming City Tourism Corporation (MCTC) as a joint-stock company. Both Zaogang and Laojia are currently under the management of the MCTC. The type of activities on offer and the general setting are similar in Zaogang and in Laojia, with natural scenic views, stage performances, and the traditional Miao style of architecture.

3.2. Methodology

We used a qualitative research approach to consider the role of institutional arrangements in the empowerment and disempowerment of local inhabitants. Qualitative methodology is suited to assessing the experiences, behaviors and opinions of people in complex cultural environments (Hay, Citation2000). We examined local residents’ experiences of their involvement in tourism activities, the reasons they were restricted from participating in decision-making, and the roles the government and external tourism developers played in the process.

From January to March 2019, the lead author collected data, mostly in the form of face-to-face in-depth interviews, which were undertaken in Mandarin, although sometimes with local dialect in the answers. In total, 36 people were interviewed: 8 residents from Fenghuang Ancient Town; 11 villagers from Zaogang and 9 villagers from Laojia who engaged in tourism to some extent; 5 government officials; and 3 tourism company staff. The interviews lasted from 40 to 120 minutes and were audio recorded. The resident informants were contacted through random sampling. We directly approached government officials and company staff using available online contact details and, subsequently, through snowball sampling. Data saturation occurred during the final interviews. Informed consent and the principles of ethical social research were followed (Vanclay et al., Citation2013), although most interviewees were reluctant to sign informed consent forms.

Participant and non-participant observation were conducted. The lead author participated in a travel group to see how package tours were organized and took extensive walks in the three locations to observe the layout of each village and the daily life of local people. The lead author also assisted some villagers in their business in order to observe how they ran tourism activities and interacted with tourists. Field notes were taken on a daily basis. Finally, all relevant government documents concerning tourism planning, regulation and policies, as well as basic information about the Miao villages (population, household number, history, economic and governance structure) were collected and reviewed.

The recorded interview data were transcribed and thematically analyzed using a multi-step coding process. We followed the coding process developed by Stoffelen (Citation2019) for disentangling multidimensional tourism datasets. First, we descriptively coded the interview transcripts and policy documents. At this stage, the descriptive coding tree was still unstructured. In the next step, we compared the descriptive codes and re-ordered, merged and deleted codes to create structured ‘pattern codes’. Finally, we compared the resulting pattern coding scheme with a provisional coding tree that we defined using the literature review of empowerment and disempowerment in Chinese tourism communities. With this comparison, we created a final hierarchical coding tree and re-coded the data, leading to the results presented below.

4. Results

4.1. Economic empowerment and disempowerment

Before tourism, local people in Fenghuang Ancient Town mainly engaged in farming, notably rice, tea, tobacco, poultry and livestock. In order to boost the local economy, in 2001 the county government leased the management rights to nine existing tourist attractions in Fenghuang Ancient Town to the Yellow Dragon Cave Corporation (YDCC) for a 50 year period. After YDCC started to promote tourism, the number of tourists grew rapidly from under 1 million per year in 2002 to over 12 million in 2019. Local people worked in the tourism industry in various ways, for example, as performance actors, boat operators, or by running small businesses, from which they earned more income than as a farmer.

After the increase in tourists in Fenghuang Ancient Town, outsiders flooded in. Many local people who owned a house in the Ancient Town rented it to outsiders or renovated it in order to run a tourism-related business by themselves. Most respondents indicated that they preferred the former option because of their lack of experience and skill in running a business. One resident noted:

‘It is safe to rent the house to the outsiders and collect money every year. If we run the guesthouse by ourselves, we have to invest a great deal of money for refurbishment and we do not have the knowledge or experience to operate a business. [If we did that] we would run a great risk of losing money’.

In 2013, the county government and YDCC together developed a new ticketing policy for visitors to Fenghuang Ancient Town. Before this policy, YDCC only charged tourists for visiting specific tourist attractions within the town. The new policy established an overall entrance fee of 148 yuan (approximately USD $23) for entering the Ancient Town. The new charge caused a dramatic decline in the number of tourists, and many local residents suffered severe reduction in income. In order to protest about the policy, some local people banded together and went on strike, although this had little effect. However, for various not-entirely-clear reasons, the policy was abandoned in 2016. Even though the policy was abandoned, many residents remained skeptical about government interference.

Given the commercial success of Fenghuang Ancient Town, after around 2003 various private company owners started to invest in other Miao villages around the Ancient Town, charging tourists for visiting. However, the government considered that the operation of too many privately-owned ethnic tourism companies would cause chaos in the market, excessive competition, and would lead to increased complaints from tourists. One government official in the Tourism Bureau of the County Government stated:

‘The involvement of too many private companies caused management problems and the number of complaints from tourists increased sharply. This was detrimental to the reputation of the local tourism industry’.

MCTC was also responsible for improving the infrastructure in the villages such as constructing roads, parking lots and performance stages. It paid the same flat annual operation fee (8000 yuan, approximately USD $1200) to Zaogang (923 inhabitants) as to Laojia (346 inhabitants), something the respondents in the villages thought to be unfair. In addition to this annual operation fee, the villages obtain tourism income from the (limited) employment opportunities provided by the MCTC and business opportunities servicing tourists. Overall, in terms of economic consequences, the three villages were both empowered and disempowered at the same time. Economic benefits were not equally distributed within the communities, thus creating some internal conflict.

4.2. Participation in tourism operations

Considering the intensity of tourism activities in Fenghuang Ancient Town, respondents indicated that they had sufficient opportunities to become involved in the tourism economy. In contrast, although tourism development brought an overall increase in income to the people in Laojia and Zaogang, there were difficulties in participating in tourism activities. The MCTC only upgraded one main road into each village. Tourists typically limited their visiting stops to places along the road, limiting the ability of villagers to participate in the tourism economy (see Adiyia et al., Citation2015 for similar tourism enclave-related issues regarding cultural tourism in Uganda). Residents whose houses were inside the village could set up stalls along the main road if they wanted to sell items to tourists. Although this was a common practice, the MCTC claimed this created clutter and chaos, and stopped villagers from doing this, and thus most villagers were forced to quit their roadside stalls.

Group visits account for the majority of tourists who visit Zaogang and Laojia. During such tours, tourist procurement of products is largely controlled by the tour guides who tend to have arrangements with certain shops. A few shop owners in Zaogang and Laojia succeeded in making a deal with the tour guides, but they have to pay a large proportion of their profit, up to 40%, as a kickback. The majority of local businesses are small scale and do not have any connection with the tour guides. Therefore, it is difficult for them to sell products to tourists and thus benefit from tourism.

4.3. Participation in decision-making

Fenghuang Ancient Town is divided into several neighborhoods, each with its own Residents’ Committee. As the Ancient Town is managed by several of these committees, it has always been difficult to achieve consensus. Although the Residents’ Committees are meant to be independent organizations that are intended to guarantee grassroots democracy, they maintain a close relationship with the government at all levels, and often fail to defend the interests of local residents when there is a conflict with the government. One resident complained:

‘I think that the Residents’ Committee doesn’t really stand for our interests. We try to express our ideas [to them], but we don’t feel that our views are valued.’

‘We think that we can’t rely on the Residents’ Committee or the government. We don’t ask for help from them unless we have no choice. It’s more realistic to rely on ourselves to deal with our problems’.

One role of the Village Committees was to pass community opinions on to the government and the MCTC. Although villagers can go to the Village Committee to explain their issues, in most cases not much would happen. One villager revealed:

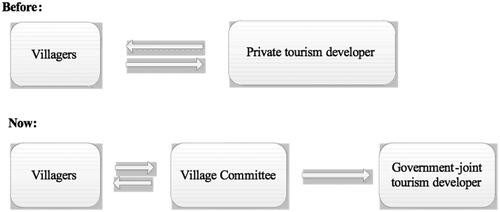

‘Before the government joint-stock company took over tourism arrangements, we could go directly to the private company and tell them what we thought. The private company valued our culture and wanted to contribute to our village. At that time, the process of addressing our concerns was streamlined. However, now we have to go to the Village Committee first if we have any confusion or problems. Sometimes we think the Village Committee doesn’t really listen to us. They’re on the same side as the joint-stock company’.

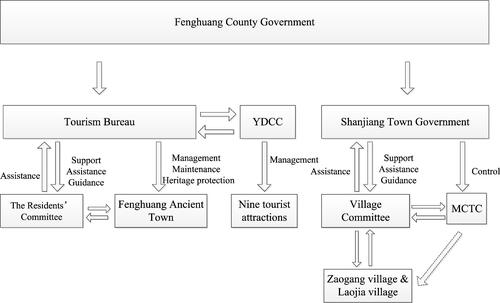

Village Committees typically comprise five people. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Secretary is at the top of the power structure, followed by the Head of the Village Committee, and three other people, each of whom is responsible for a different area of administration. A recent reform combined the CCP Secretary and the Head of Village Committee, making them the same person. Therefore, the CCP Secretary has a paramount position in each village. Membership of a Village Committee was not normally remunerated. Members had to work as well as perform their committee tasks. Nowadays, committee members tend to receive a small government allowance, and the offices of the Village Committee are provided by the county-level government. To some extent, this support strengthens the connection between the Village Committee and the government (see ).

An example of the lack of influence of the villagers can be seen in the relocation of performances from Zaogang to Laojia. The previous private company had built an outdoor stage and organized performances in Zaogang, becoming a key tourism attraction there. After the MCTC took over the tourism activities, it relocated the performances to Laojia, where it built a new outdoor stage. This resulted in a decline of income from tourism in Zaogang. The villagers in Zaogang went to the Village Committee several times to try to get the stage performances back. However, the MCTC insisted that the stage performances remain in Laojia:

The reason that we would like to put the stage performance in Laojia Village is that the Miao style houses are in good condition and villagers are cooperative.

4.4. Psychological empowerment and disempowerment

Tourism development brought about different levels of psychological empowerment and disempowerment between people in the three locations. Respondents in Fenghuang Ancient Town indicated that they became more confident because of increasing income and living standards. One resident summarized:

We now make much more money than before, when we could only make a living by farming. Now, life is better and more prosperous.

The respondents in Zaogang lacked confidence in initiating new projects by themselves. In addition to hosting stage performances, some villagers used to charge tourists for boat trips, which was quite profitable. However, the MCTC and government claimed it was not safe for villagers to provide such tours. A year or two after the company’s arrival in the village the MCTC took over all boating operations by restricting local people from competing. An MCTC respondent explained:

It isn’t safe for the villagers to run the boating. They don’t buy insurance for the tourists. If anything happens, the government has to take the responsibility. Serious accidents in the scenic spot would have very severe consequences. Not only would the town government be blamed by the upper-level government, the reputation of the village would also be ruined, which would be catastrophic for future tourism development.

As Laojia was the place where the government and MCTC gave emphasis, it had more resources than the other villages. Respondents there were more optimistic about the future and believed their life will become better with more tourism. They stated that the MCTC had told them it will invest in building more guesthouses in the near future and there will be more tourists.

4.5. The socio-cultural roots of tourism-related disadvantages of the host community

The involvement of external developers has promoted tourism development in the Miao villages. Although there are signs of empowerment, the top-down organization of tourism and the way this system has been formally and informally institutionalized within the local communities has led to a disadvantaged position of many ethnic people within the study areas. We identified three underlying reasons for this: coercion, nepotism and favoritism; limited participation; and low levels of social cohesion.

4.5.1. Coercion, nepotism and favoritism

The interviews indicated that nepotism is pervasive among the Village Committees, township government and MCTC. Therefore, these organizations can use their administrative power to achieve their objectives without having to pay attention to villager concerns. This was obvious in various situations in which there were evident conflicts of interest among the stakeholders in key positions. For instance, the inaugural Secretary of CCP in Shanjiang Town used to be the Head of the MCTC. The Head of Zaogang Village Committee simultaneously worked at a managerial level in MCTC.

These structures and the following observations show that the top-down tourism governance system also influences local-level power relations, in both formal and informal ways. Several respondents in Zaogang and Laojia indicated that the Village Committees try to persuade villagers to consider the MCTC’s perspective whenever there is a conflict with MCTC. We found anecdotal information that, if this persuasion did not work, the Village Committee would attempt to gain the support of other villagers against those who were not willing to accept MCTC’s position. In the Miao Villages, the performance of traditional rituals is an important part of village life, especially for weddings and funerals. To hold a successful wedding or funeral, people need assistance from other villagers in the performance of these rituals. Some respondents indicated that the Village Committees had threatened ‘difficult’ villagers, suggesting that no one would help them in the rituals if they persisted in their opposition. In most cases, the uncooperative residents would back down because of a fear of being isolated. When asked about how they would deal with villagers who did not cooperate, a CCP Secretary of a Village Committee claimed:

‘If [the villagers] don’t take the collective benefit into account and continue to cause trouble to the whole village, then we can also refuse to provide any assistance when they need help next time’.

4.5.2. The lack of participation

Top-down talkfests organized by the Village Committee are the basic participation format in local villages (Weng & Peng, Citation2014). The talkfests are not very inclusive, as each household can only nominate one person to attend. Normally, the male family members attend. Women tend not to have an awareness of participation and they generally think the talkfests are only intended for men, reconfirming existing issues of gender inequality. In terms of the effectiveness of the talkfests, most respondents harbored an attitude of disappointment. On the one hand, most villagers thought that the talkfests were just a form of tokenism through which their problems with MCTC cannot really be addressed. On the other hand, most villagers felt that it would be difficult to arrive at a common opinion with so many people speaking at the talkfests. Agreement is hardly ever reached, and our interviewees indicated limited desire to participate in future discussions.

4.5.3. Low level of social cohesion

The Village Committees are the only organizations in Zaogang and Laojia. There is no NGO presence in either location. The lack of NGOs in China is common (Bao & Sun, Citation2007), in contrast to many other countries where NGOs play a critical role in supporting communities to deal with development issues and cope with emergencies (Busscher et al., Citation2019). Therefore, when the Village Committee fails to speak up for the villagers, there are no other bodies that will collect their concerns and represent their interests. Although there are some tourism sector associations (such as the Hoteliers Association in Fenghuang Ancient Town), their functions are limited to conveying new regulations and policy directives from the government and representing the self-employed business owners’ ideas. These tourism associations only included a small number of local residents. Many people were not aware of the existence of these associations. One resident mentioned:

‘The association is an assistant of the government. … Its function is limited to conveying information’.

5. Discussion: comparing the influence of institutional arrangements on disempowerment across the case study areas

When combining our observations, it appears that the top-down, formal decision-making structure is not the only source of the disempowerment within the study areas. It is the interrelation between top-down governance structures, local elites that advocate the views of formal decision-making organizations, and local habits, perceptions and cultural practices that fix power imbalances within (and between) the study areas. Despite the economic empowerment of some individuals, the political disempowerment in all three places also resulted in psychological disempowerment, and most local residents showed general apathy towards tourism activities.

We summarize the institutional arrangements of the three study sites in . In Fenghuang Ancient Town, three characteristics can be identified: (1) the lease of the nine tourist attractions from the Fenghuang County government to the YDCC; (2) the separation of tourist sites and residential areas; and (3) the partnership between government and the YDCC. The private lease structure of the publicly owned tourist attractions is a rather unique institutional form compared to similar ethnic tourism destinations in neighboring provinces in China. Under these arrangements, tourism development clearly accelerated and the residents in Fenghuang Ancient Town operate their own tourism businesses or work as tourism staff mostly independently of the government and the YDCC. When asked about the existence of the YDCC, many respondents indicated that they were not aware of the existence of this company at all. Some guesthouse owners did establish a partnership with the YDCC, for example, selling tickets (on commission) to tourists for the stage performances organized by YDCC. Despite the relative freedom of residents to join the tourism economy, the current institutional arrangements direct power to the YDCC-government partnership, without significant input from residents regarding the larger tourism development trajectory in the Ancient Town. Consequently, although the county government does not participate in the commercial operation of tourism in Fenghuang Ancient Town, the pre-existing economic and political inequality was not altered by the growth of tourism.

Table 1. The institutional arrangements in the three case areas.

The government took more control in Zaogang and Laojia than in Fenghuang Ancient Town, in both formal and informal ways. When Zaogang and Laojia were being developed as tourism destinations by the private company, the government only intervened when disagreements occurred. When MCTC replaced the private company, considerable top-down control was asserted over all tourism activities in the villages; a situation that was formally and informally facilitated by local elite structures and cultural practices. Although Zaogang and Laojia shared similar institutional arrangements, both in a political and socio-cultural sense (), they received different levels of preference from MCTC, which influenced the level and nature of tourism development in each village and the opportunities of local actors to benefit from tourism activities. In fact, while the establishment of community-level participatory platforms to connect individual actors to powerful tourism development companies has been noted as efficient pathways to provide social and spatial inclusivity and empowerment in western contexts (see e.g. Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016), the opposite occurred in Zaogang and Laojia. In this sense, our study shows in detail not only how different elements of empowerment are intertwined (O’Hara & Clement, Citation2018; Scheyvens, Citation1999, Citation2000), but also why as a pathway to empowerment (Cole, Citation2006; Sofield, Citation2003) community participation is more complex and institutionally shaped than often assumed.

6. Conclusion

Our research took an Ancient Town and two Miao villages in Hunan, China, as case studies to examine how different institutional arrangements between government, tourism developer, and local communities in ethnic tourism areas influence the empowerment and disempowerment of the villagers in those places. In the case study areas, many stakeholders experienced various forms of disempowerment created by the institutional arrangements. These arrangements consist of formal rules, regulations and governance relations that shape tourism development processes, and the informal dynamics that influence how different people within society perceive and respond to the challenges associated with top-down tourism development. In the economically-disadvantaged villages, residents faced the difficult situation that external investments were welcome, but coincided with handing over decision-making control to an external authority.

The socio-economic constraints of the Miao villages – including poor accessibility and a lack of tourism experience and business acumen among residents – resulted in reliance on external capital to develop tourism in these places. However, the external government-joint tourism company that brought the needed capital injection was predominantly concerned with a maximization of return rather than with the interests of local residents. Even in the case of Fenghuang Ancient Town, which avoided the institutional situation of the two villages that had to transfer control to an external, government-steered tourism developer, the decision-making power of community members was limited due to the close partnership between the government and the tourism development organization. Consequently, tourism-related impacts for community members were neither collective nor equally distributed.

In theory, the Residents’ Committees in towns like Fenghuang and Village Committees in rural villages like Zaogang and Laojia should guarantee grassroots democracy. However, in our study area, the rigid power structure, which was riddled with nepotism and favoritism, hindered communities from being effectively engaged.

The low level of social cohesion further hindered collective power to develop from the bottom up. Miao villages used to be based on agriculture, with kinship as the main driver of social relations. As a legacy of this, the respondents in the studied villages continued to prioritize their own family’s welfare over collective action. In this context, it proved difficult to mobilize a local critical mass to challenge existing institutional arrangements. The poor effectiveness of the village talkfests is indicative of this. The notions that power can only be performed when actors have the necessary skills and resources and that their relative position in a social network influences whether their skills and resources will be used (Jacobsen & Cohen, Citation1986; Sofield, Citation2003) become visible through our observations above. Our study showed how the limited mobilization of local actors to challenge their relative position in the decision-making network followed from the actions of powerful actors within the network who applied both overt and covert pressure but also from locally engrained cultural habits, mistrust and perceptions within the communities. This combination made the otherwise noted as efficient empowerment practice of using community-level participatory platforms to connect local actors to tourism development organizations (see Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016) ineffective in our study areas.

Although previous studies have explored how Chinese local communities can be disempowered by tourism development (e.g., Feng, Citation2012; Han et al., Citation2014; Weng & Peng, Citation2014), the role of institutional arrangements in this process remained underexplored. Our study showed how power imbalances in ethnic tourism development are systemic and rooted in both politics and cultural structures. Instead of simply blaming top-down decision-making for disempowerment within local communities, as happens regularly within the tourism literature, we found that it was the interrelation between these top-down structures, local elite systems, and cultural habits and responses to these challenges that fixated power inequality in the studied areas. The awareness of these interrelations between formal and informal regulation, and between political and cultural institutionalization of power, is particularly relevant for studies of (ethnic) tourism empowerment in rural China, considering the rapid development that is happening in many places. There are also often clear tensions as to who drives these changes, on which level and with which (cultural, economic and political) perspectives.

Additionally, since tourism in Chinese ethnic destinations is predominantly organized in a top-down manner and most decisions are made behind closed doors, future works should focus on the decision-making process itself. Moreover, considering the size and ethnic diversity of rural China, future studies should explore the variety of local institutional arrangements that influence tourism-related empowerment and disempowerment in diverse locations.

To avoid disempowerment in ethnic communities, the devolution of power should be on the agenda (Zielinski et al., Citation2020), something that can only be achieved when organizations, policymakers and tourism enterprises put the interests of local actors first (McCombes et al., Citation2015). Considering the profit nature of the tourism sector, there seems to be a fundamental challenge in achieving the devolution of power and the prioritization of local interests (Stoffelen et al., Citation2020), especially in institutional contexts that are characterized by top-down control. Despite these structural issues to achieving community empowerment through tourism, the agency of community members should not be disregarded. Their bargaining power and rights consciousness should be cultivated as pathways that potentially will lead to empowerment (Weng & Peng, Citation2014), particularly since the devolution of power will not automatically solve local-level power relations and elite systems that may influence the equity of tourism-related outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bei Tian

Bei Tian is a PhD candidate of cultural geography at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences at the University of Groningen. Her research interest is in ethnic tourism, empowerment and community resilience.

Arie Stoffelen

Arie Stoffelen is assistant professor of cultural geography and tourism geography at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences at the University of Groningen. His research interests centre on sustainable regional development processes from the lens of tourism development, and the interface between (tourism) mobilities, border-crossings and geopolitics.

Frank Vanclay is professor of cultural geography at the Faculty of Spatial Sciences at the University of Groningen. He has a long standing interest in social impact assessment and in the social impacts of tourism.

References

- Adiyia, B., Stoffelen, A., Jennes, B., Vanneste, D., & Ahebwa, W. M. (2015). Analysing governance in tourism value chains to reshape the tourist bubble in developing countries: The case of cultural tourism in Uganda. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1027211

- Badola, R., Hussain, S. A., Dobriyal, P., Manral, U., Barthwal, S., Rastogi, A., & Kaur Gill, A. (2018). Institutional arrangements for managing tourism in the Indian Himalayan protected areas. Tourism Management, 66, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.020

- Bao, J., & Sun, J. (2007). Differences in community participation in tourism development between China and the West. Chinese Sociology & Anthropology, 39(3), 9–27.

- Busscher, N., Vanclay, F., & Parra, C. (2019). Reflections on how state-civil society collaborations play out in the context of land grabbing in Argentina. Land, 8(8), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8080116

- Butler, G. (2017). Fostering community empowerment and capacity building through tourism: Perspectives from Dullstroom, South Africa. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 15(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2015.1133631

- Chen, F., Xu, H., & Lew, A. A. (2020). Livelihood resilience in tourism communities: The role of human agency. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(4), 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1694029

- Chen, Z., Li, L., & Li, T. (2017). The organizational evolution, systematic construction and empowerment of Langde Miao’s community tourism. Tourism Management, 58, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.03.012

- Choi, H. C., & Murray, I. (2010). Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903524852

- Cole, S. (2006). Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(6), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost607.0

- Craig, G., & Mayo, M. (Eds.). (1995). Community Empowerment: A Reader in Participation and Development. Zed Books.

- Dolezal, C., & Novelli, M. (2020). Power in community-based tourism: Empowerment and partnership in Bali. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–19. (online first).

- Fang, J., & Hong, J. Y. (2020). Domestic migrants’ responsiveness to electoral mobilization under authoritarianism: Evidence from China’s grassroots elections. Electoral Studies, 66, 102170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102170

- Feng, X. (2012). Who are the “hosts”?: Village tours in Fenghuang County. Human Organization, 71(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.71.4.f738385u0206j866

- Feng, X. (2015). Protesting power: Everyday resistance in a touristic Chinese Miao village. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 13(3), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2014.944190

- Han, G., Wu, P., Huang, Y., & Yang, Z. (2014). Tourism development and the disempowerment of host residents: Types and formative mechanisms. Tourism Geographies, 16(5), 717–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.957718

- Hanna, P., Vanclay, F., Langdon, E. J., & Arts, J. (2016). Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest action to large projects. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(1), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2015.10.006

- Hay, I. (2000). Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford University Press.

- Henderson, J., Teck, G., Ng, D., & Si-Rong, T. (2009). Tourism in ethnic communities: Two Miao villages in China. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 15(6), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250903210811

- Jacobsen, C., & Cohen, A. (1986). The power of social collectivities: Towards an integrative conceptualization and operationalization. The British Journal of Sociology, 37(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/591054

- Li, F. M. S. (2006). Tourism development, empowerment and the Tibetan minority: Jiuzhaigou national nature reserve, China. In: A. Leask and A. Fyall (Eds.), Managing world heritage sites (pp. 226–238). Routledge.

- Lo, K., Li, J., Wang, M., Li, C., Li, S., & Li, Y. (2019). A comparative analysis of participating and non-participating households in pro-poor tourism in Southern Shaanxi. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(3), 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1490340

- McCombes, L., Vanclay, F., & Evers, Y. (2015). Putting Social Impact Assessment to the test as a method for implementing responsible tourism practice. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 55, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2015.07.002

- Michaud, J. (2009). Handling mountain minorities in China, Vietnam and Laos: From history to current concerns. Asian Ethnicity, 10(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631360802628442

- O’Hara, C., & Clement, F. (2018). Power as agency: A critical reflection on the measurement of women’s empowerment in the development sector. World Development, 106, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.002

- Park, E., & Kim, S. (2016). The potential of Cittaslow for sustainable tourism development: Enhancing local community’s empowerment. Tourism Planning & Development, 13(3), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1114015

- Prenzel, P., & Vanclay, F. (2014). How social impact assessment can contribute to conflict management. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 45, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.11.003

- Ramos, A. M., & Prideaux, B. (2014). Indigenous ecotourism in the Mayan rainforest of Palenque: Empowerment issues in sustainable development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(3), 461–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.828730

- Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(2), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00919275

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Ahmad, A. G., & Barghi, R. (2017). Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tourism Management, 58, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.016

- Scheyvens, R. (1999). Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Management, 20(2), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00069-7

- Scheyvens, R. (2000). Promoting women’s empowerment through involvement in ecotourism: Experiences from the Third World. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580008667360

- Scheyvens, R. (2002). Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Pearson Education.

- Schmidt, J., & Uriely, N. (2019). Tourism development and the empowerment of local communities: The case of Mitzpe Ramon, a peripheral town in the Israeli Negev Desert. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(6), 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1515952

- Shi, T., Wu, X. H., Wang, D. B., & Lei, Y. (2019). The Miao in China: A review of developments and achievements over seventy years. Hmong Studies Journal, 20, 1–23.

- Sofield, T. (Ed.). (2003). Empowerment for sustainable tourism development. Pergamon.

- Statistical Communiqué of Fenghuang County. (2019). 2019 On the Economic and Social Development. http://www.fhzf.gov.cn/zfsj/tjgb/202005/t20200525_1679456.html

- Stoffelen, A. (2019). Disentangling the tourism sector’s fragmentation: A hands-on coding/post-coding guide for interview and policy document analysis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(18), 2197–2210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1441268

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2016). Institutional (dis)integration and regional development implications of whisky tourism in Speyside, Scotland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1062416

- Stoffelen, A., Adiyia, B., Vanneste, D., & Kotze, N. (2020). Post-apartheid local sustainable development through tourism: An analysis of policy perceptions among ‘responsible’ tourism stakeholders around Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(3), 414–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1679821

- Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309

- Su, J., & Sun, J. (2020). Spatial changes of ethnic communities during tourism development: A case study of Basha Miao minority community. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 18(3), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1679159

- Su, M. M., Wall, G., Ma, J., Notarianni, M., & Wang, S. (2020). Empowerment of women through cultural tourism: Perspectives of Hui minority embroiderers in Ningxia, China. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, (online first), 1–22.

- Timothy, D. (2007). Empowerment and stakeholder participation in tourism destination communities. In A. Church & T. Coles (Eds.), Tourism, power and space (pp. 199–216). Routledge.

- Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27(3), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- Vanclay, F., Baines, J., & Taylor, C. N. (2013). Principles for ethical research involving humans: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part I. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 31(4), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2013.850307

- Weng, S., & Peng, H. (2014). Tourism development, rights consciousness and the empowerment of Chinese historical village communities. Tourism Geographies, 16(5), 772–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.955873

- Xu, H., Jiang, F., Wall, G., & Wang, Y. (2019). The evolving path of community participation in tourism in China. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8), 1239–1258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1612904

- Xu, H., Zhang, C., & Lew, A. A. (2014). Tourism geography research in China: Institutional perspectives on community tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 16(5), 711–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.963663

- Yang, L., & Wall, G. (2008). Ethnic tourism and entrepreneurship: Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Tourism Geographies, 10(4), 522–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802434130

- Yang, L., Wall, G., & Smith, S. (2006). Ethnic tourism development: Chinese Government perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 751–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.06.005

- Yu, H. (2015). A vernacular way of “safeguarding” intangible heritage: The fall and rise of rituals in Gouliang Miao village. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(10), 1016–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1048813

- Zielinski, S., Kim, S. I., Botero, C., & Yanes, A. (2020). Factors that facilitate and inhibit community-based tourism initiatives in developing countries. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(6), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1543254