Abstract

Critical research concerning ecotourism has revealed the activity’s socio-economic impacts, including low-wage employment-based dependencies for many rural communities. While these dynamics are important, a crucial aspect of the ecotourism industry that falls outside this conventional sort of dependency is land use dynamics, specifically land use change, sales and entrepreneurship. We examine these dynamics in Corbett Tiger Reserve, India, where promotion of (eco)tourism since the 1990s has influenced significant changes in local land use. These changes were initially facilitated by outsiders buying land and setting up hotels and resorts in villages adjoining the Reserve. Empirical research reveals that while this initial boom of outsiders buying land has waned, land owning villagers are now setting up tourism enterprises on their own land, thereby diversifying land use from agriculture to tourism. Critical agrarian research has shown that material and symbolic factors influence farmers’ decision-making regarding land use change. An agrarian studies perspective thus facilitates a nuanced understanding of tourism-related land use diversification and change. By bringing agrarian and ecotourism studies approaches together here, we contribute to both by emphasising the importance of (eco)tourism in agrarian change and of attention to land use change in ecotourism studies to understand how rural people negotiate and navigate (eco)tourism in relation to land use. We also contribute to tourism geographies more broadly by highlighting how land use decision-making shapes local spaces in the course of ecotourism development. We draw attention to the broader processes of and impacts of ecotourism that shift generational rural land use influenced by changing values of land outside a protected area. Rendering land touristifiable deepens villagers’ dependence on the market and alienates them from their land. Ecotourism commodifies nature, and we show that this commodification extends to rural land outside of ecotourism zones per se.

Introduction

Ecotourism is widely promoted as a win-win solution for resource conservation and local people dependent on those resources (Honey, Citation2008). In many cases, however, ecotourism development instead exacerbates structural violence, unequal power relations and negative ecological impacts contradicting its ‘eco’ framing (Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2017; Lasso & Dahles, Citation2021; Stronza & Gordillo, Citation2008). Critical research has thus questioned the sustainability of (eco)tourism initiatives, specifically where they are promoted as supporting social development for local people (Scheyvens & Russell, Citation2012).

Research in critical agrarian and rural studies has illustrated the ways that land use is altered or diversified with the introduction of neoliberal policies, while reinforcing social differentiation (Andreas et al., Citation2020; Ferguson, Citation2013; Gray & Dowd-Uribe, Citation2013). This research indicates that material and symbolic factors influence farmers’ decision-making regarding land use change. Thus far, however, agrarian research has not substantially addressed the role of ecotourism in such dynamics. This is despite the fact that tourism continues to be widely promoted in rural areas, especially in the global south, and particularly in former colonies (Duffy, Citation2008; Fletcher, Citation2014). On the other hand, tourism research has acknowledged, to an extent, the influence of tourism on land use decisions and patterns (Scheyvens & Russell, Citation2012). However, integration of an agrarian studies perspective to develop a nuanced understanding of tourism-related land use diversification and change has been less apparent. In this analysis, we bring these two research approaches together to emphasise the importance of ecotourism in agrarian change, on the one hand, and understand how rural people negotiate and navigate land use diversification and change in relation to ecotourism development, on the other.

It is particularly important to examine land use change in the context of ecotourism in rural areas given that ecotourism is presumed to have minimal impact on landscape (TIES, Citation2019). Our study of these processes focuses on two villages close to Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR) in the Uttarakhand state, north India. A large proportion of people living around CTR are dependent on tourism in the form of wage labour or employment, contributing to significant change in the socio-economic landscape. While these dynamics are important, the focus of this paper is on an aspect of the ecotourism industry that falls outside this conventional sort of dependency and that has been largely overlooked in the critical literature thus far: land use dynamics, specifically related to land use change, sales and entrepreneurship on individually held land.

Inspired by Tania Li’s influential paper ‘Rendering Land Investible’ (2017), we term our analysis of these dynamics as ‘rendering land touristifiable’. Li (Citation2017) explores the temporal aspects of the process by which land becomes a commodity capable of purchase, sale, and production for global markets. In building on Li’s analysis, our study is centred on the question: what are the (eco)tourism and rural dynamics that render land touristifiable, and with what consequences for rural livelihoods?

To bring attention to the rural realities that influence the process of rendering land touristifiable, our analysis focuses primarily on local residents who have managed to successfully insert themselves into the tourism development process. These remain a minority at present, as not everyone has the capital to shift their land use, and many have instead sold their land and left villages, thus rendering land tourisitifiable through their absence. We believe this focus on forms of local agency in the context of larger structural pressures is crucial to understand the impacts of an activity that introduces significant changes in local lives and livelihoods in the name of biodiversity conservation.

In the following section, we outline research on (eco)tourism, its impacts on land, as well as research from agrarian studies that focuses on land use and diversification. We then describe the historical context of our study as well as the qualitative ethnographic research via which it was conducted. Following this, we describe the study’s findings from the two villages around CTR. Through an examination of the different tourism enterprises and land use, we show that many villagers retain ownership of their land even while dependencies on the market deepen. Ecotourism commodifies nature, and we show that this commodification extends to rural land outside of ecotourism zones per se.

Land use dynamics in agrarian and (eco)tourism studies

Land is particularly contentious and political; it is where socio-cultural relations, state policies, and market values come together and confront one another. The material and symbolic relationship of local people with land often stands in opposition to states’ and market actors’ views of land as a ‘commodity, [where] its specificity [is] replaced by universals’ (Nirmal, Citation2016, p. 242). Symbolic connection with land includes indigenous identities that are tied to specific landscapes and the spiritual entities understood to reside therein, on which communities’ social systems and livelihoods depend (Sahu, Citation2008). Meanwhile, the economic value or legal status attributed to land has material implications, such as ownership titles or the ability to practice agriculture. Formal or legal frameworks tend to define land in a singular way that does not capture people’s multifaceted relationships with land in different contexts (Li, Citation2014). At the same time, state processes of using land for the purpose of specific investments, such as conservation or development programmes, may be pursued through assembling a range of factors like technologies, discourses and biophysical entities (Li, Citation2017). Thus, land becomes a space wherein multiple processes and meanings intersect with different uses. As a result, there is a mosaic of factors influencing land use; including livelihood dependence, ancestral ties and market value. Social factors include land use across generations which reveal how each generation engages with state and non-state actors (Hall et al., Citation2015). This is also tied to the temporality of land use, for instance, during a market-influx period or after market-influx (Li, Citation2014, Citation2017). In relation to markets, agrarian research has focused on questions of labour, land grabbing and accumulation of land in rural spaces (Hall et al., Citation2015; Scoones et al., Citation2012). Market-based conservation initiatives such as ecotourism also impact the social and physical landscape, as elaborated below. While the impact of tourism has been examined as one form of land grabbing, so far this has only been developed to a limited extent (by for instance, Rocheleau, Citation2015).

By contrast, a substantial body of research has explored ecotourism as a significant factor in shaping social and economic rural landscapes (e.g. Bury, Citation2008; Ojeda, Citation2012). This is rooted in the understanding of ecotourism as a market-based instrument, and one important form of neoliberalisation of nature (West & Carrier, Citation2004). Duffy (Citation2008) indeed, argues that ecotourism does not simply exemplify neoliberalism but is in fact one of the main ways that neoliberal economics and ideology are spread, particularly to rural areas of the Global South. Concrete impacts of ecotourism include evictions, restricted access to natural resources, low wage employment and intensification of existing inequalities (Lasso & Dahles, Citation2021; Ojeda, Citation2012). Livelihoods shift towards tourism-oriented businesses, and for villagers without enough capital, tourism becomes the only form of income thereby reducing their ability to adapt to fluctuations in the tourism market (Bury, Citation2008; Lasso & Dahles, Citation2021). Existing research thus offers important insights concerning the sustainability of livelihood shifts towards tourism through employment or wage labour.

While this research demonstrates that local livelihoods are often affected in the process of ecotourism development, however, there remains limited analysis of how the process influences local land use, and decision-making concerning this land use, in particular (Fletcher, Citation2009; West & Carrier, Citation2004). Yet, land use changes, such as diversion of land from agriculture to tourism, can be understood as one of ecotourism’s most significant impacts. Land use can be altered or reshaped with entry of private tourism stakeholders from outside the village or community (Gardner, Citation2012). The impact of ecotourism on land-use also reveals that local people often end up having to align themselves to neoliberal or market logics to cater to tourists (West & Carrier, Citation2004). Conservation initiatives including ecotourism development promoted in new contexts create new dynamics related to the value of land, as when private lands become more profitable, and community lands are not valued (Brockington et al., Citation2008; Cabezas, Citation2008; Zimmerer, Citation2006).

Land sales inevitably become part of the expansion of the ecotourism market, and this is reflected in the amount of capital brought in from outside the local context (Duffy, Citation2002). Tourism offers an opportunity to sell agriculture land that is unproductive, shifting land use dynamics. Foreigners often end up buying large tracts of land, resulting in further increase in land prices that create barriers for local people to set up their own ecotourism enterprises (Fletcher, Citation2012). Yet, some villagers are also able to use ecotourism as an opportunity to access land rights through joint venture partnerships with outsiders (Gardner, Citation2012). Such partnerships also take the form of arrangements where ecolodges are built on community commons through partnerships with private actors and NGOs (Lamers et al., Citation2014). In non-communal land settings, it is landowners who often benefit more than the landless from tourism development through lease partnerships (Scheyvens & Russell, Citation2012).

The above research demonstrates arrangements within (eco)tourism development that impact land use and related dynamics, particularly through public-private partnership. But, land use changes are also responses to broader processes of rural life shaped by agrarian policies, or lack thereof, and socio-cultural factors tied to mobility. In some cases, engagement with the market can provide benefits that national development plans otherwise do not provide (Gardner, Citation2012). Research has also demonstrated more direct ties between agrarian issues and tourism development. For instance, Münster and Münster (Citation2012) examined growth of tourism as driven by an agrarian crises and new modes of farming in south India, wherein a change in agrarian policies, leading to capitalist agriculture, created a climate that encouraged rural people to invest in tourism (Münster and Münster, Citation2012). Similarly, Gascón (2016) describes how growth of residential tourism in the Ecuadorian Andes amplified the exchange value of land relative to its use value and hence caused a move away from agriculture as the main livelihood pursuit.

Thus, changing values of land resulting from tourism development can create shifts towards tourism-based livelihood dependencies. Communities threatened by neoliberal initiatives ‘also see market reforms and market relationships as offering possibilities for political-economic and cultural gains’ (Gardner, Citation2012, p. 380). Drawing from such dynamics, agrarian and rural research has focussed on the multiple ways that land is used, in addition to and beyond agriculture (Ferguson, Citation2013; Gray & Dowd-Uribe, Citation2013). However, this body of research has been less focussed on land use diversification in the context of rural (eco)tourism in particular.

In the following analysis, we examine the impacts of ecotourism on land use in villages around Corbett Tiger Reserve. We draw attention to the broader processes of and impacts of (eco)tourism that shift generational rural land use, and thereby the socio-ecological configuration of rural landscapes. Ecotourism is a complex, and often extractive process, one which leads to local involvement, but also creates market dependences. We also recognise that forms of market engagement contribute to symbolic and material meaning for villagers, particularly in relation to socio-economic mobility. Our aim is to illuminate the key influencing factors that render rural land touristifiable.

Methodology

This research is grounded in critical theory, drawing in particular from a post-structuralist political ecology (PE) perspective. PE critically analyses nature-society relationships through the lens of power relations and political economic structures (Robbins, Citation2012). A post-structuralist perspective maintains that social life is influenced by structures both discursive and material, but that most people are at least partially aware of the structures and able to resist or negotiate them in order to exert agency and engage in counter-conduct (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2017). Employing this conceptual approach, the ethnographic research for this study was conducted by the first and second authors from August 2018 to August 2019. Data collection was wholly qualitative, entailing semi-structured and active interviews as well as ongoing participant observation. Active interviews are similar to everyday conversations and allow for questions to tap into understanding of social reality through factual and emotional accounts (Hathaway & Atkinson, 2003). As the majority of informants objected to audio recording, data collected in this manner were primarily recorded in field notes, with verbatim quotations inscribed immediately and more substantial notes elaborated after the interview. However, one participant of the study was willing to be recorded, and his interview was subsequently transcribed. Participant observation entailed living in one of the villages under study and participating in activities such as farming, celebrations and weddings. Observations from this experience were also recorded in field notes. Data were analysed through inductive coding to identify the prevalent or dominant themes that emerged from interviews and interactions (Bernard, Citation2006). Secondary data were also collected through reviewing government reports, articles and academic literature.

Fieldwork for the overarching research project was conducted in six villages around the south-eastern boundary of CTR to examine local responses to and engagement with Corbett tourism. As a component of this larger project, this study draws on 23 interviews each lasting between 20 and 60 min with researchers, residents of two study villages and tourism entrepreneurs, in order to understand the range of impact of tourism development. Respondents were identified through referral and purposive sampling (Bernard, Citation2006). The aim was to interview participants who were involved in tourism through land use, in addition to the traditional livelihoods including subsistence agriculture, small-scale livestock rearing, wage employment and leasing land (). As noted in , this includes villagers whose livelihoods shifted from farming and other work, and those whose primary livelihood shifted but hold family farm land where other members of the family practice agriculture. Agriculture practice is ancestral for those who continue to be associated with it, and therefore former livelihoods remain as agriculture.

Table 1. Livelihood, land and age characteristics of interview respondents.

Prior informed consent for participation and taking interview notes was obtained verbally, because written forms raised suspicion as did the use of recording devices for most participants. Participants’ anonymity was assured in advance as this ensured their comfort in participating; therefore, all research participants are presented anonymously here. While the university hosting the research does not require formal ethical clearance, the research was conducted in conformance with the ethics code of the American Anthropological Association.Footnote1

These two focus villages were selected for this study because of the significant contrast in tourism-related land use change that occurred in either. In one, Teran, significant land use change has taken place, especially with the arrival of outsiders’ tourism businesses. This village thus represents the tourism boom in the landscape. By contrast, in the other, Kumer, the land use change has been slower and is ongoing, such that villagers are becoming entrepreneurs on their own land. This village thus exhibits a greater role for local residents in the tourism development process. Comparison between the two sites usefully highlights the range of different forms of land use change tourism development influences and the factors responsible for these different trajectories.

Context: The Corbett Tiger Reserve

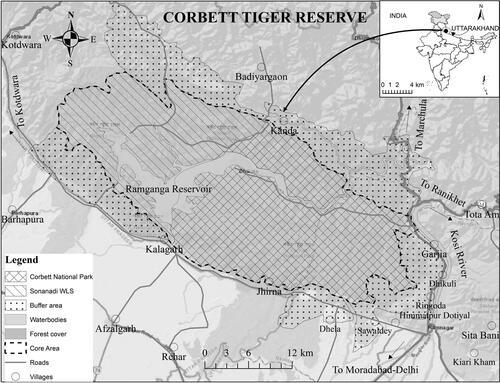

The Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR) located in Uttarakhand state of north India, covers 1288.31 sq. km and is divided into core and buffer areas. The south-eastern boundary of the reserve is towards the plain region of the state, leading to a higher density of village settlements compared to other boundary areas.

Figure 1. Corbett Tiger Reserve. Created by: Ecoinformatics Lab, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment (ATREE).

Uttarakhand has had a history of political and economic struggle intertwined with its natural resources. A historical perspective is important for understanding what people do with land; their actions and decision-making are based on knowledge and interpretations which contribute to ‘political points and even changes in policy or practice’ (Peluso, Citation2012, p. 80). Pre-colonial as well as colonial regimes in the region benefitted from forest-based enterprises (Rangan, Citation2000). Therefore, enterprises involving natural resources are not new in the region, yet their nature and form have changed over time.

Uttarakhand became an independent state in 2000 after a prolonged movement for statehood. This movement was rooted in demands for development and economic opportunities in the hill regions and the perceived inability of a government in the lowlands to grasp the needs of people living in the hills (Rangan, Citation2004). Private sector investment was encouraged in the new State through infrastructure projects including tourism (Rangan, Citation2004). While industries and investment from outside contributed to growth within the state, uneven development between the hill and plains continued (Mukherjee, Citation2012). This historical perspective helps to explain people’s involvement in tourism in terms of lack of other livelihood options.

Early 1990s saw the introduction of ecotourism in CTR by the Forest Department, who offered tour guide training to villagers. In 2012, the NTCA promoted ecotourism as a way to support both local communities and conservation. While ecotourism is promoted as a tiger conservation strategy, mainstream tourism forms continue to be dominant in Corbett. A study found that only 20 out of 79 tourist establishments attracted tourists interested in nature-based activities; the rest cater primarily to families, corporate or event-based tourism (Waste Warriors, Citation2015). Large resort chains have adopted elements of ‘ecotourism’ such as nature walks or safaris which are popular. According to a CTR official, there is a growing number of Indian tourists who opt for safaris, and a reduction of foreign tourists.

Our study includes villagers who work as safari guides, and are now creating their own enterprises. This aligns with the promotion of ecotourism as primarily ‘community based and community driven’ (NTCA, Citation2012, p. 106). Of the two study villages: Teran and Kumer, Teran is located close to a safari gate and has been dominated by tourist establishments for years. Here, the infrastructure and changes in land use began with the entry of outsiders almost two decades ago. By contrast, Kumer is located away from a safari gate and until recent years had remained less impacted by tourism infrastructure. These two villages represent the temporal and spatial difference in the shifts of land use, exemplifying different phases of the historical and ongoing land use change described below in the following section.

Results

After the initial ecotourism promotion, the mid 1990s saw the beginning of large resort establishment around Corbett. CTR has eight gates for safaris, four of which are located in the south eastern part of the reserve. Villagers claim that since state formation in 2000, governance, and especially land related issues, were not dealt with appropriately by the State as outsiders were allowed to buy land without any restrictions. This observation is in line with the encouragement of private sector investment in the newly formed state. In 2004 the Uttarakhand forest department created a tourism zone within CTR boundaries to promote conservation (Mazoomdar, Citation2012b). Outside these boundaries the administrative authority permitted the construction of hotels with open access to use of stone and sand from the nearby Kosi river bed (Mazoomdar, Citation2012b). Corruption and negligent administration by the forest department and local government led to land acquisition in villages by outsiders (Mazoomdar, Citation2012b).

Teran: Impacts of tourism on land and post market influx

Teran is located close to a safari gate and the local town that is a main hub for public transport. There are approximately 400 families in Teran spread over 88 ha. According to one respondent, these include families living as tenants. The exact number of such tenants was not known as they form a transient population. Many households rent out part of their homes or build a room on their land, and tenants in these houses are usually from the hill regions, settled in the village for employment related to tourism. Villagers state that there are over 50 tourism establishments here and about 70% of the village population is directly dependent on tourism. Out of 416 official workers, only 23 are agriculture cultivators as per the last government census (Census of India, Citation2011). The rest work outside the village, in the forest department or have leased part of their land to tourism related enterprises. These enterprises include souvenir shops, restaurants or small snack shops, safari and guide booking agencies, or renting out a room to the taxi drivers who bring tourists by road.

There are different ways in which tourism enterprises are organised in villagers’ homes and land. Some of the land owners live behind the shops away from the road, and often hold enough land to also have a small fruit orchard, subsistence vegetable farms or sometimes a combination of both. Recently, a villager who owned a school has leased the school property for a tourism enterprise. The few villagers who have not used their land for tourism purposes continue to farm but with increasing difficulty due to crop damage caused by wildlife. For many, the changes that have occurred are seen as a step towards better lifestyles.

A farmer who owns a tea shop complained that the lack of limits on tourism development continued to negatively impact the landscape: ‘There is a lot of noise and garbage now, and our ability to take livestock to graze has become restricted’. While navigating issues relating to tourism, this villager rents out a small room in his home for the drivers of tourists’ vehicles for extra seasonal income. He continues to farm, and sells produce from his fruit orchard. He claims that his family would be ready to sell their land if there was a financial need. While many villagers are critical of the type of unchecked tourism that has impacted the village, their livelihoods are tied to this tourism. Citing the growing competition and changing culture in the village, those who could afford to have left the village to seek work elsewhere. Views towards Corbett specific tourism are critical, even for a young villager who has grown up seeing tourism in his village:

I have seen the reduction in value of money while growing up. Here, the money came too easily, too fast. My father started this guesthouse and I studied hotel management for four years. I saw scope in that field. My sister and I help with this guesthouse, but I work [outside] mainly. I don’t like it here. There are too many cars, traffic, and always packed with tourists.

Speaking about his experience in tourism, a respondent recounts that he was exposed to the tourism business while growing up. His father sold their farming land to a hotel in 1994:

After selling the land, we didn’t benefit much because we didn’t receive the full amount of money. My father kept some land for our home, so we lived by the hotel, and my father worked as an employee in that hotel. My souvenir business is what I developed myself, and I have taken this shop on lease to keep my business going.

Kumer: Local entrepreneurship and land sales

Kumer is located at about 10 km distance from a CTR safari gate. It is adjacent to an emerging forest safari route but farther away from main roads. There are approximately 125 families in the village. These families own tracts of land for agriculture, and some have been selling or leasing out their land for what eventually become tourism enterprises. Farming continues here but with difficulties from wildlife incursions into fields. The families who do not own tracts of agricultural land work as agriculture labourers for land owning families, or find employment in the local marketplace or in tourism. Out of a total of 217 workers in Kumer, a majority (135) are agriculture cultivators (Census of India, Citation2011).

According to the village head, about 60% of the villagers do not want more hotels in the village; they see Teran as a cautionary tale of how tourism could take over a landscape. If financial need arises outmigration and land sales remain an option for many. As compared to Teran, there are fewer hotels and resorts in Kumer, even after the tourism boom. Up until 2012, there were three tourism establishments in this village, and the employment of very few villagers was tied to tourism. As of 2019, there were eight hotels, and seven more under construction, in a village area of 99.32 ha (Census of India, Citation2011). Some of those who sell their land move out of the village to buy larger pieces of land in other parts of the region or houses in towns and cities. One tourist establishment is co-owned and run by villagers and set up on their own land. A second tourism establishment owned by a villager is in the process of being set up on their own land and land additionally leased from a neighbouring villager.

While desire for economic mobility prompts the sale of land, familial ties to land play a role in making it difficult to sell land. These contradictory approaches to land indicate strong material as well as symbolic connections to land. One villager explained the material and symbolic factors that they navigate when making decisions regarding land sale or land use diversification:

What we are today is because of our forefather’s farming practice. In spite of the troubles we continue to farm because all that we have right now is from the land-from agriculture. But if a person needs money, he is in a desperate situation he has to sell his land, and additionally he gets agriculture land rates so it’s not a great situation. But compared to other villages [closer to CTR gates] [this village] is in a better state. Development and destruction are part of the same problem, we just need to balance the ratio of both since it is inevitable that both will take place.

Describing the categorisation of land, an upper-class villager developing his own tourism enterprise, pointed out that,

No one buys land for agriculture now. Whoever farms, is also troubled now. We put in lakhs of rupees in farming but we don’t get much in return. But we continue because it is our traditional practice… Now, if in the future, I have faced a problem and need 40 or 50 lakhs [rupees], my only option is to sell my land.

The amount of 40–50 lakhs (52–65,000 USD approximately) is quite high and reflects the high market value of land around Corbett generally. It reflects this villager’s ability and ambition to set up his enterprise and further achieve economic mobility.

The financial needs for families are centred around access to education, debt payment, access to infrastructure facilities like health care, transport and working closer to home rather than out-migrating, which has been a common phenomenon in Uttarakhand. Other socio-cultural factors that prompt selling or leasing out sections of family land include weddings. Hosting a wedding in itself has also influenced land sales, especially for daughters’ weddings. Some express disappointment in this trend that emphasises a show of wealth parallel to the trend of ‘destination weddings’ taking place around CTR. Despite concern over the rise of land sales there is little that other villagers can do to stop anyone from selling their land. Concerning the rise in the material show of weddings, one couple expressed:

The family had to sell part of their land because they had to get their daughters married. It is after all, their personal matter, and they will have their own reasons to sell land. How can we stop them?

Table 2. Forms of land use change by interview respondents in Teran and Kumer.

I have worked in tourism since 2008. I saw that through Goibibo or Makemytrip [online travel agency platforms] customers call and see what each hotel charges and what packages they have. So there is a lot of competition and it will get tough. I will be an addition in to what five people are already doing. After converting part of my agriculture land into commercial land, I am working on building an adventure park. I have also taken part of my neighbour’s land on lease for this park.

In line with such local entrepreneurship, there are five homestays, and one locally owned and managed eco-camp.

Discussion

Partly as a consequence of the introduction of ecotourism, villagers around CTR have been changing land use, through selling or leasing land, land as a form of income and livelihood diversification. Livelihoods entailing small-scale agriculture and livestock keeping have been diminishing over the years. Land use change or diversification is often directly from agriculture to development of tourism establishments such as camps or hotels. These shifts in land use indicate that the (eco)tourism market contributes to changing land values, and consequently incentivises land use diversification. In this process, (eco)tourism market renders land touristifiable. Related factors such as challenges in farming, and access to infrastructure and desire for economic mobility also contribute to land use change or diversification.

(Eco)tourism development is now about a generation old, and has created dependencies that are not sustainable. Villagers point out that they suffer due to sudden closure of tourism operations or during the low tourist season. These aspects are typical of ecotourism as it commodifies nature and creates wage or employment dependencies (Fletcher & Neves, Citation2012). Simultaneously, villagers state that it is the only form of work they can access due to their skills and low returns from agriculture.

Both villages, Teran and Kumer, illustrate the impacts of land use change, reflected temporally and spatially. In Teran, many villagers sold their land for tourism to gain economically in the 2000s which resulted in a rapid change in the landscape with a majority of agricultural land sold (Rastogi et al., Citation2015). The impacts of sale of land and post-market influx dynamics experienced by villagers is evident here. In the early 2000s, many villagers saw the growing tourism market as an opportunity to sell part or all of their land and earn money overnight (Bindra, Citation2010). Some of the biggest properties around Corbett are owned by influential outsiders (Mazoomdar, Citation2012b). The surge of investment by outsiders led to the changing landscape in the village. Villagers growing up with an exposure to the tourism market became interested in setting up their own enterprises. The initial tourism boom has impacted current land use and created conditions that determine future investment in land (Li, Citation2017). Teran also represents for many an example of how tourism infrastructure led by outsiders can negatively impact the landscape. As Li points out, ‘Booms and busts are not just cycles, they are historical events that initiate novel trajectories that should be tracked across time’ (Li, 2017, p. 2). The significant and fairly rapid acquisition of land in Corbett drew negative attention in the media (Bindra, Citation2010; Mazoomdar, Citation2012a, Citation2012b) and led to a policy report on the impacts of tourism on the landscape (Bindra, Citation2010).

With a reduction in outsider involvement in land, villagers with capital are setting up enterprises or leasing land. In Kumer, the number of hotels is relatively lower than in Teran and villagers are wary about the extent of tourism development. There are, however, discrepancies in the extent of tourism-based enterprise and land use change. Villagers sell land or shift land use for financial and economic mobility. Those who own land and are of a higher class have been able to set up tourist establishments, or plan large scale ones, such as an adventure park. Kumer is located further from a safari gate as compared to Teran and up until the time of the study the rate of land sale and land use change were relatively lower than in Teran.

Entrepreneurship on one’s own land has meant that these villagers have been able to retain ownership of their own land and have moved away from working as employees in outsiders’ hotels and resorts. Material and symbolic factors influencing these decisions include: wildlife damage to crops, aspirations to economic mobility, financial debt and ability to work close to home rather than outmigration. The ability to retain land is advantageous and while not always explicit, some villagers have been able to gain livelihood options or use tourism as a means of economic mobility. Yet as they themselves express, this is still within the context of limited options and opportunities and constraints of broader market dynamics. The possibility of retaining land and gaining higher returns than agriculture has meant that tourism becomes the more attractive livelihood option within a limited horizon for a select few landowners.

Land remains a highly valuable asset for those who retain it and lease it, and appears to give owners more flexibility in deciding what they do with the land. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in particular caused a loss of business for all tourist enterprises around Corbett. According to the second author’s observation in Teran, after the first and second wave of COVID-19, villagers who worked in bigger cities were returning as they lost their jobs due to the lockdowns. While it was not possible to gather empirical data on impacts of the pandemic, this study paves way for a future examination of the relationship between land use and ecotourism in relation to COVID-19 both for residents of and those returning to the villages.

Conclusion

Ecotourism is known to impact social-economic dynamics by creating employment-based dependencies in a landscape. This article has focussed on a different form of dependency: land use change and diversification in the rural context around Corbett Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand. The purpose of focussing on land use change is to provide insights on the growing influence of tourism and the factors that contribute to villagers’ involvement in the industry. Around CTR, in addition to selling land, land owning villagers are looking to tourism not for employment in hotels, but to set up enterprises or lease out their own land. This is in a context where land has largely been used for agriculture. The history of Uttarakhand State formation and rural migration helps situate the ongoing calls for better access to development and infrastructure, which influences what people do with their land.

In developing this analysis, the study integrates insights from agrarian and tourism studies, and in particular, contributes to redressing the relative dearth of research on dynamics of land use change within tourism studies. By bringing perspectives from agrarian studies into conversation with (eco)tourism research, we contribute to both fields by emphasising the importance of (eco)tourism in agrarian change and of attention to land use change in ecotourism studies to understand how rural people negotiate and navigate (eco)tourism in relation to land use. In the process, we also contribute to tourism geographies more broadly by offering a conceptual framework for understanding how land use decision-making shapes local spaces in the course of ecotourism development.

Decision making regarding land use, or sale, is driven by the need to diversify livelihood from agriculture which, for many, continues to give minimal productive returns. Livelihood diversification is triggered by wildlife-caused damage to crops, debt payments, education, weddings and aspirations for economic mobility. The deepening dependence on the market contributes to villagers’ alienation from their land in ways that agriculture did not, and creates greater vulnerability to national and global tourism trends. The affective connection to land through ancestral inheritance also influences decision-making regarding land sale. The changes in land are thus situated within both material and symbolic registers. Additionally, the historical, ongoing lived-experiences of aspirational and tourism-based changes influences people’s land use.

These broader historical and ongoing processes connect to a strand of agrarian research that explores the multiple ways that rural populations use land and how land use is thereby diversified. This study calls for future research on (eco)tourism to focus on the ways tourism development processes affect patterns of land use and local stakeholders’ decision-making concerning use of their land. Understanding land use change or diversification via tourism could provide insights concerning questions of the sustainability of tourism-based work generally. Further research in this area has potential to shape ecotourism and rural development policies that respect connection to land and counter market pressures that cause alienation and dependency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Revati Pandya

Revati Pandya is a PhD candidate, Wageningen University, Netherlands. In her current research, Revati is examining local responses to (eco)tourism through a political ecology lens. She also works on conservation and community rights issues with organisations in India. [email protected].

Hari Shankar Dev

Hari Shankar Dev is a Naturalist and Guide, Corbett Tiger Reserve. Hari is from Ramnagar, Uttarakhand. His training and work experience spans research in wildlife conservation, sustainable livelihood intervention, sustainable waste management, ecotourism and education in and around the Corbett area. [email protected].

Nitin D. Rai

Nitin D Rai is an independent researcher. Nitin uses a political ecology approach to understand the implications of state conservation policy and practice for people and landscapes. Nitin conducts most of his fieldwork in the Biligiri Rangaswamy Temple Tiger Reserve where he has explored issues ranging from historical patterns of forest use, cultural relationship to landscape, and the consequences of accumulation by conservation. [email protected].

Robert Fletcher

Robert Fletcher is an associate professor, Wageningen University, Netherlands. His research interests include conservation, development, tourism, climate change, globalization, and resistance and social movements. He uses a political ecology approach to explore how culturally-specific understandings of human-nonhuman relations and political economic structures intersect to inform patterns of natural resource use and conflict. [email protected].

Notes

1 See http://www.aaanet.org/issues/policy-advocacy/upload/AAA-Ethics-Code-2009.pdf. (Accessed on August 1, 2021).

References

- Andreas, J., Kale, S. K., Levien, M., & Zhang, Q. F. (2020). Rural land dispossession in China and India. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(6), 1109–1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1826452

- Bernard, R. H. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches ( 4th ed.). Altamira Press, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Bindra, P. S. (2010). Report on impact of tourism on tigers and other wildlife in Corbett Tiger Reserve. 16. A study for Ministry of Tourism. Government of India.

- Brockington, D., Duffy, R., & Igoe, J. (2008). Nature unbound: Conservation, capitalism and the future of protected areas. Earthscan Publications UK and USA.

- Büscher, B., & Fletcher, R. (2017). Destructive creation: Capital accumulation and the structural violence of tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 651–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1159214

- Bury, J. (2008). New geographies of tourism in Peru: Nature-based tourism and conservation in the Cordillera Huayhuash. Tourism Geographies, 10(3), 312–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802236311

- Cabezas, A. L. (2008). Tropical blues. Tourism and Social Exclusion in the Dominican Republic Latin American Perspectives, 35(3), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X08315765

- Census of India. (2011). District census handbook, Nainital. Directorate of Census Operations, Uttarakhand.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2017). Handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Duffy, R. (2002). A trip too far: Ecotourism, politics and exploitation. Earthscan Publications Ltd.

- Duffy, R. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: Global networks and ecotourism development in Madagasgar. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(3), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154124

- Ferguson, J. (2013). How to do things with land: A distributive perspective on rural livelihoods in Southern Africa. Journal of Agrarian Change, 13(1), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2012.00363.x

- Fletcher, R. (2009). Ecotourism discourse: Challenging the stakeholders theory. Journal of Ecotourism, 8(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902767245

- Fletcher, R. (2012). Using the master’s tools? Neoliberal conservation and the evasion of inequality. Development and Change, 43(1), 295–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01751.x

- Fletcher, R. (2014). Romancing the wild: Cultural dimensions of ecotourism. Duke University Press.

- Fletcher, R., & Neves, K. (2012). Contradictions in tourism: The promise and pitfalls of ecotourism as a manifold capitalist fix. Environment and Society, 3( 60-77). https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2012.030105

- Gardner, B. (2012). Tourism and the politics of the global land grab in Tanzania: Markets, appropriation and recognition. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 377–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.666973

- Gascón, J. (2016). Residential tourism and depeasantisation in the Ecuadorian Andes. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(4), 868–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1052964

- Gray, L., & Dowd-Uribe, B. (2013). A political ecology of socio-economic differentiation: Debt, inputs and liberalization reforms in southwestern Burkina Faso. Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(4), 683–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.824425

- Hall, R., Edelman, M., Borras, S. M., Scoones, I., White, B., & Wolford, W. (2015). Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions’ from below. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1036746

- Hathaway, A. D., & Atkinson, M. (2003). Active interview tactics in research on public deviants: Exploring the two-cop personas. Field Methods, 15(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X03015002004

- Honey, M. (2008). Ecotourism and sustainable development: Who owns paradise? Island Press.

- Joshi, D. (2018, April 22). In homestay policy, Uttarakhand eyes jobs in hills to check forced migration. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/dehradun/in-homestay-policy-uttarakhand-eyes-jobs-in-hills-to-check-forced-migration/story-FuW6id5whL1dUwMjTZbLhL.html

- Lamers, M., Nthiga, R., van der Duim, R., & van Wijk, J. (2014). Tourism-conservation enterprises as a land-use strategy in Kenya. Tourism Geographies, 16(3), 474–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.806583

- Lasso, A. H., & Dahles, H. (2021). A community perspective on local ecotourism development: Lessons from Komodo National Park. Tourism Geographies, 23, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1953123

- Li, T. (2014). What is land? Assembling a resource for global investment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39(4), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12065

- Li, T. M. (2017). Rendering land investible: Five notes on time. Geoforum, 82, 276–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.04.004

- Mazoomdar, J. (2012a, May 4). Corbett. Now, On sale. Mazoomdar. https://mazoomdaar.blogspot.com/search?q=Corbett

- Mazoomdar, J. (2012b, December 22). A township inside Corbett. Mazoomdar. https://mazoomdaar.blogspot.com/search?q=Corbett

- Mukherjee, P. (2012). Globality and imagined futures: A brief history of Uttarakhand’s development dreams. In B. Brar & P. Mukherjee (Eds.), Facing globality: Politics of resistance, relocation and reinvention in India (201-233). Oxford University Press.

- Münster, D., & Münster, U. (2012). Consuming the forest in an environment of crisis: Nature tourism, forest conservation and neoliberal agriculture in South India: The neoliberalization of nature, South India. Development and Change, 43(1), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01754.x

- Nirmal, P. (2016). Being and knowing differently in living worlds: Rooted networks and relational webs in indigenous geographies. In W. Harcourt (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of gender and development (pp. 232–250). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-38273-3_16

- NTCA. (2012, October 15). Gazette notification. National Tiger Conservation Authority.

- Ojeda, D. (2012). Green pretexts: Ecotourism, neoliberal conservation and land grabbing in Tayrona National Natural Park, Colombia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.658777

- Peluso, N. L. (2012). What’s nature got to do with it? A situated historical perspective on socio-natural commodities. Development and Change, 43(1), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01755.x

- Rangan, H. (2000). State economic politics and changing regional landscapes in the Uttarakhand Himalaya, 1818-1947. In A. Agrawal & K. Sivaramakrishnan (Eds.), Agrarian environments: Resources, representations, and rule in India (23-46). Duke University Press.

- Rangan, H. (2004). From Chipko to Uttaranchal: The environment of protest and development in the Indian Himalaya. In R. Peet & M. Watts (Eds.), Liberation ecologies: Environment, development, social movements (2nd ed., 338-357). Routledge.

- Rastogi, A., Hickey, G. M., Anand, A., Badola, R., & Hussain, S. A. (2015). Wildlife-tourism, local communities and tiger conservation: A village-level study in Corbett Tiger Reserve, India. Forest Policy and Economics, 61, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.04.007

- Robbins, P. (2012). Political ecology: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell Publication.

- Rocheleau, D. (2015). Networked, rooted and territorial: Green grabbing and resistance in Chiapas. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 695–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.993622

- Sahu, G. (2008). Mining in the Niyamgiri hills and tribal rights. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(15) 19–21.

- Scheyvens, R., & Russell, M. (2012). Tourism, land tenure and poverty alleviation in Fiji. Tourism Geographies, 14(1), 1–25.

- Scoones, I. A. N., Marongwe, N., Mavedzenge, B., Murimbarimba, F., Mahenehene, J., & Sukume, C. (2012). Livelihoods after land reform in Zimbabwe: Understanding processes of rural differentiation. Journal of Agrarian Change, 12(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2012.00358.x

- Stronza, A., & Gordillo, J. (2008). Community views of ecotourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(2), 448–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.01.002

- TIES. (2019). What is ecotourism? The International Ecotourism Society. https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/

- Uttarakhand Tourism Development Board (UTDB). (2020). Homestay policy: DeenDayal Upadhyay Griha Awaas Homestay Policy. https://uttarakhandtourism.gov.in/homestay-policy/

- Waste Warriors. (2015). Detailed survey of hotels, inns and lodges-waste and water disposal area: Corbett landscape. Report for Uttarakhand Environment Protection and Pollution Control Board

- West, P., & Carrier, J. G. (2004). Ecotourism and authenticity: Getting away from it all? Current Anthropology, 45(4), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1086/422082

- Zimmerer, K. S. (2006). Cultural ecology: At the interface with political ecology—The new geographies of environmental conservation and globalization. Progress in Human Geography, 30(1), 63–78.