Abstract

The development of the tourism industry in regional contexts has attracted significant interest from tourism geographers, in which the evolutionary economic geography (EEG) approach has been of interest over the last decade. Recent research on EEG has emphasised the role of institutions and particularly legitimacy in new path development, claiming that legitimacy is crucial for the development of emerging industries. Against this backdrop, this paper explores the role of legitimation and delegitimation in the development of the sharing economy in Innlandet, a tourism region in Norway. The article poses two research questions. How is the legitimacy of Airbnb expressed by key tourism stakeholders in a tourism region in Norway? Moreover, how can the shifting roles of legitimation and delegitimation among key stakeholders in the tourism industry inform the literature on new path development? These issues are explored in qualitative interviews with respondents from four key tourism stakeholder groups: consumers, Airbnb hosts, incumbent firms, and regional industry and policy actors. The findings reveal legitimacy issues mainly related to regulatory and normative ambiguities, described by biased regulations that result in economic leakages to other regions and countries and concerns about decreasing local value creation in the region. These findings indicate that the sharing economy lacks legitimacy among the stakeholders. The article concerns the role of legitimation and delegitimation in new path development processes, arguing that delegitimation prevents transformative changes and path development processes.

Introduction

The emergence and development of the tourism industry in regional contexts have attracted great interest in tourism geography studies (Brouder, Citation2017; Baekkelund, Citation2021), in which the evolutionary economic geography (EEG) approach has been of interest for the last decade (Brouder, Citation2020). The EEG literature examines long-term economic changes and why development differs across regions by stressing the importance of time, history, and pre-existing capabilities to understand regional development (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2006). Recent EEG research has highlighted the role of institutions, particularly legitimacy, in new path development. Legitimacy is considered to be particularly important for early path creation (Binz et al., Citation2016) and emerging industries (Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). Previous studies have tended to focus on successful path creation processes. Only a few studies have researched the role of delegitimation and how the loss of legitimation may lead to unsuccessful path development (e.g. Binz & Gong, Citation2021; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022).

In line with the seminal work of Suchman (Citation1995), this paper treats legitimacy as ‘a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’ (p. 574). Furthermore, legitimacy is viewed as an endogenous process in which negotiations and interactions between key stakeholders influence stakeholders’ perceptions of businesses (Uzunca et al., Citation2018).

The sharing economy is an innovation and megatrend transforming the tourism industry (Belezas & Daniel, Citation2022; Kuhzady et al., Citation2021). Several researchers (e.g. Belk, Citation2014; Schlagwein et al., Citation2019) have tried to conceptualise and define the sharing economy without identifying a standard definition. Scholars advocate that other terms, for example, ‘platform economy’ (Schor, Citation2015) or ‘access-based consumption’ (Bardhi & Eckhardt, Citation2012), are more appropriate for describing a phenomenon in which digital platforms intermediate peer exchanges. However, we treat the sharing economy as ‘consumers (or firms) granting each other temporary access to their under-utilised physical assets (‘idle capacity’), possibly for money’ (Meelen & Frenken, Citation2015). We also include services in our understanding of the sharing economy (Muñoz & Cohen, Citation2017). The sharing economy is described in the literature as an innovation that enables firms or individuals to launch new services or businesses and enter new markets (Belezas & Daniel, Citation2022), and this innovation has the potential to transform how individual actors behave (Kuhzady et al., Citation2021), to recalibrate the organisation of economic activity and to change the value creation (Kenney & Zysman, Citation2016). This definition and understanding of the sharing economy has strong similarities to the definition of innovation provided by Schumpeter (Citation1934), which treats innovation as new combinations that may result in new or better products, markets, production methods, suppliers and forms of organisation, and is also in line with how innovation is defined in EEG (e.g. Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018).

The term ‘sharing economy’ has a normative character and is valued as a positive and progressive achievement (Acquier et al., Citation2017). Despite positive rhetoric, the SE’s ‘dark side’ has received increasing attention (Frenken & Schor, Citation2017; Frenken et al., Citation2019). The normative character of the concept has raised discussions about the true nature of sharing and the misuse of the concept (Belk, Citation2014), for example, in discussions about the competition between Airbnb and traditional forms of accommodation (Leick et al., Citation2020; Strømmen-Bakhtiar & Vinogradov, Citation2019). The sharing economy is often described as a case of ‘sharewashing’, whereby ‘the language of sharing is used to promote new modes of selling’ (Light & Miskelly, Citation2015, p. 49), even though the business model more closely resembles that of traditional market firms (Muñoz & Cohen, Citation2018). Criticism of the sharing concept has challenged the SE’s legitimacy (Ackermann et al., Citation2021; Hwang, Citation2019; Newlands & Lutz, Citation2020). This criticism is related to the sharing economy’s characteristics such as taxes, regulations, labour, job security, consumer issues (Hwang, Citation2019) and its disruptive nature (Guttentag, Citation2015; Guttentag & Smith, Citation2017).

This paper is intended to contribute to the ongoing debate about the role of legitimacy, particularly delegitimation, in new path development in EEG (Binz & Gong, Citation2021; Gong et al., Citation2022; Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). Against this backdrop, this paper explores the role of legitimation and delegitimation in the diffusion of the sharing economy in Innlandet, a diverse tourism region in Norway, by conducting qualitative interviews with respondents from four key tourism stakeholders groups in the region: consumers, Airbnb hosts, incumbent firms, and regional industry and policy actors (Uzunca et al., Citation2018).

The article addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How is the legitimacy of Airbnb expressed by key tourism stakeholders in a tourism region in Norway?

RQ2: How can the shifting roles of legitimation and delegitimation among key stakeholders in the tourism industry inform the literature on new path development?

Theoretical background

Evolutionary economic geography and legitimacy

Evolutionary economic geography (EEG) is a theoretical framework aiming to understand long-term economic change and why it differs across regions (Boschma & Martin, Citation2010) by emphasising that development is rooted in the existing economic structure of regions and nations, including existing industrial structures, regional firms, local knowledge flows and regional branching (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018). ‘New path development’, defined as ‘the emergence and growth of new industries and economic activities in regions’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019, p. 114), is a key concept in economic geography. The concept describes several regional development processes, for example, path extension (continuation of an existing industrial path), path creation (the emergence of entirely new industries), path importation (attraction of established industries from outside the region), path upgrading (fundamental intra-path transformations that changes an existing regional path into a new direction) and path diversification (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019). The latter can be defined as ‘moves into a new industry based on related or unrelated knowledge combinations’ (Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019, p. 1636). EEG emphasises that new regional paths develop through either the formation of new ‘local’ firms, the transplantation of firms from other locations in new industries in the region, or the commencement of new activities by existing firms in new industries in the region (Isaksen & Jakobsen, Citation2017). Entrepreneurs, firms and other organisations play a key role in both processes. EEG treats new path development as an incremental, endogenous, technology-driven and business-led process, in which development is an outcome of previous development in the region (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018). This narrow understanding of regional development has been criticised (e.g. Hassink et al., Citation2019). Hence, recent studies have put more emphasis on the role of exogenous sources, particularly on the arrival of actors from outside the region and extra-regional knowledge linkages (e.g. Trippl et al., Citation2018), as well as on legitimacy (Binz & Gong, Citation2021; Gong et al., Citation2022; Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021) and the role of demand (Martin et al., Citation2019).

Binz et al. (Citation2016) argue that four key processes are particularly influential for path development: knowledge creation, market formation, financial investment, and legitimacy. The latter process has recently received increased attention in EEG. Legitimacy in its social environment is crucial for a firm’s survival and success (Brown, Citation2012; Suchman, Citation1995). It is an essential resource for attracting other critical resources and can be enhanced by the strategic actions of new ventures (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002).

Legitimacy is often described as having three aspects: regulative, normative and cognitive (Scott 1995a, as cited in Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). New products and processes will be confronted with scepticism if they do not align with the regulative, normative and cognitive institutions of a given place. Regulative legitimacy must be acquired early in a venture’s existence and concerns how new ventures function and expand according to the existing rules, regulations, and expectations created by the government or other influential actors (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002). Normative legitimacy describes how new firms address the norms and values established in the environment, and cognitive legitimacy is created when new ventures ‘address collectively accepted practices, knowledge, and ideas’ (Vestrum et al., Citation2017, p. 1724), including both taken-for-granted assumptions and more specialised, explicit and codified knowledge (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Citation2002).

Despite the relative lack of emphasis on legitimation, particularly on delegitimation, their roles have recently been investigated in a few studies in different industries (Gong et al., Citation2022). Jolly and Hansen (Citation2022) researched legitimacy spillovers from contextual structures in the Swedish biogas industry. They suggest that the development of a regional industry’s legitimacy is influenced by spillovers from related industries, policy activism and spillovers from other regions. The authors argue that spillover effects may contribute to the loss of legitimacy. Furthermore, Binz and Gong (Citation2021) conducted a case study comparing system-building and institutional work processes between industries that are new to the world (NTW) and new to the region (NTR). NTW industries were described as radically new industries in an early stage of their global life cycles, only locally validated, with limited spatial diffusion and dependent on loose institutional support structures. NTW industries often encounter scepticism as they challenge established practices and disrupt institutions. Such industries must be constructed and legitimised ‘from scratch’ (Gong et al., Citation2022). In contrast, NTR industries are more mature and have successfully diversified into multiple regional contexts and developed deeply institutionalised support structures. Thus, NTR industries can profit from industries established in other regions in legitimacy processes. Hence, NTR and NTW industries face different challenges in legitimacy processes because the ‘liabilities of newness’ differ between industries being NTW and NTR (Binz & Gong, Citation2021).

The sharing economy in the tourism industry

The sharing economy is often described as an urban phenomenon because dense urban geography, short distances and high population densities create circumstances that ‘enable sharing economy firms to flourish’ (Davidson & Infranca, Citation2015, p. 218). Even though the sharing economy is significantly less effective in the suburbs (Thebault-Spieker et al., Citation2017), is it not limited to large cities (Adamiak, Citation2019). However, there is less knowledge about the sharing economy outside metropolitan regions and the USA (Agarwal & Steinmetz, Citation2019; Thebault-Spieker et al., Citation2017). Researchers are also calling for more research on the sharing economy in the tourism industry (Ackermann et al., Citation2021; Kuhzady et al., Citation2021), which is one of the industries most affected by the sharing economy.

The sharing economy has resulted in disruptive changes in the tourism industry, and the literature demonstrates that the sharing economy’s legitimacy is being contested. Studies have identified legitimacy issues related to regulatory, legal, taxation and labour issues, as well as consumer concerns, social inequality and political, economic and societal impact, such as disruption to traditional industries (Hwang, Citation2019). Moreover, Ackermann et al. (Citation2021) found that legitimacy issues inform tourists’ decisions as they compare sharing economy services to traditional forms of accommodation and that a lack of legitimacy negatively impacts behavioural intentions.

Airbnb is one of the sharing businesses that dominate global markets and is the primary cause of the worldwide growth of the SE. It is an example of an exogenous source and an actor that has arrived from outside the region (Trippl et al., Citation2018). The platform has recently been researched in several different contexts and countries. Guttentag (Citation2015) describes Airbnb’s disruptive potential in the traditional accommodation sector, underlining the importance of understanding its disruptive effect, and Guttentag and Smith (Citation2017) show that guests are substituting Airbnb rentals with mid-range hotels. Furthermore, Zach et al. (Citation2020) found that lodging firms need to act fast in order to compete with disruptive innovations such as Airbnb, emphasising that incumbent firms need to allocate more resources to respond quickly. Research from a tourist destination in south-eastern Norway shows that Airbnb rentals had a negative impact on traditional forms of accommodation, indicating that Airbnb is regarded as a substitute (Leick et al., Citation2020). Strømmen-Bakhtiar et al. (Citation2020) also show that home rentals create periods where there are ‘ghost towns’ in a remote Norwegian municipality, which makes it challenging for local inhabitants to enter the real estate market. Research from other contexts supports these findings. Benítez-Aurioles (Citation2019) found that the expansion of Airbnb in Barcelona has negatively affected hotel occupancy and economic returns in all hotel categories, and Airbnb’s entry into the Texas hotel market had ‘a quantifiable negative impact on local hotel room revenue’ (Zervas et al., Citation2017, p. 704). This unintended development has implications for policymakers and has necessitated the development of new governance strategies (Vith et al., Citation2019). The need to regulate sharing economy companies has been acknowledged globally, and various restrictions and regulations have been introduced (Vinogradov et al., Citation2020). However, research also shows that hotels in Norway had more guests in regions in which Airbnb expanded rapidly compared with regions with lower Airbnb activity (Strømmen-Bakhtiar & Vinogradov, Citation2019), and Leick et al. (Citation2021) found that the demand for traditional forms of accommodation is positively influenced by Airbnb demand in the long term. Their findings indicate that growth in Airbnb spurs growth in the established tourism industry at smaller destinations. Finally, Strømmen-Bakhtiar et al. (Citation2020) showed that Airbnb could positively influence peripheral municipalities by increasing local tourism, stimulating the restoration of traditional houses and increasing mobility.

Methods

Innlandet county as a study region

Innlandet county is located in south-eastern Norway and has evident peripheral characteristics. The region has a growing elderly population and a low birth rate. Innlandet covers a large area, has many public sector employees, and has an industrial structure dominated by agriculture, manufacturing and tourism. The tourism industry is a priority in the region and is essential for ensuring employment, settlement and other local political objectives in parts of the region (Sandberg et al., Citation2020). In 2018, Innlandet had three million commercial guest nights (hotels, mountain lodges, camping grounds and cabins), as well as accommodation on platforms such as Airbnb. The accommodation sector constitutes 27.1% of the total value creation in the tourism industry in Innlandet county (Norwegian Hospitality Association, Citation2020). In addition, the region has approximately 85,000 second homes, which is the highest number in Norway.

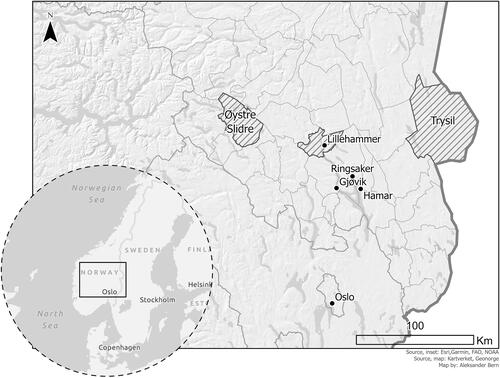

This study was mainly conducted on three tourist destinations in the region: Øystre Slidre, Lillehammer, and Trysil (). These municipalities are vital tourist destinations in Innlandet, located in the western (Øystre Slidre), central (Lillehammer) and eastern (Trysil) parts of the region. Øystre Slidre is located 900 metres above sea level, close to Jotunheimen National Park. Beitostølen is the best-known tourist destination in Øystre Slidre. Lillehammer is a renowned winter sports destination, and the town became famous for organising ‘the best Olympic Winter Games ever’ in 1994 (e.g. Caple, Citation2014). Trysil is located close to the Swedish border and contains Trysilfjellet, the largest winter sports centre in Norway. Trysil has the highest number of second homes in Norway. Being in the same region, the three municipalities share formal institutions and political and economic conditions. They also share geographical characteristics: All of them are close to mountainous regions and are located only two to three hours’ drive from Oslo, the capital of Norway, as well as Norway’s main airport.

Airbnb in innlandet

The sharing economy platform investigated in this study is Airbnb. Airbnb is the most prominent example of the sharing economy in the researched region, which increased the likelihood that the stakeholders would be familiar with the platform. Airbnb was launched in Norway in 2010, with an intense period of growth from 2014 to 2016 (Airbnb, Citation2016). After years of growing interest in the Norwegian market, the Norwegian Tax Administration introduced new regulations in January 2020 that required Airbnb to report information on rental transactions during the financial year. In addition, the Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation introduced short-term rental legislation in January 2020, with different regulations according to the type of property offered (Airbnb, n.d.-a).

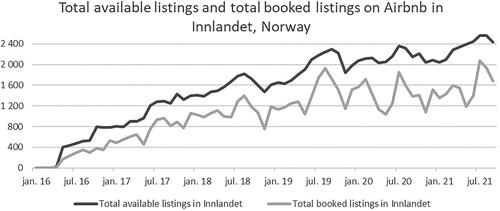

Data on Airbnb from AirdnaFootnote1 were analysed. The number of Airbnb listings and bookings in Innlandet are shown below in and . Airbnb grew substantially in Innlandet from 2016, reaching 2560 listings in July 2021 (). Despite this, we can see an evident decline in March 2020, September 2020 and March 2021, probably due to the three waves of COVID-19 in Norway.

Figure 2. Number of Airbnb listings and bookings in Innlandet, half-yearly data (January 2016–July 2021). Source: Airdna.

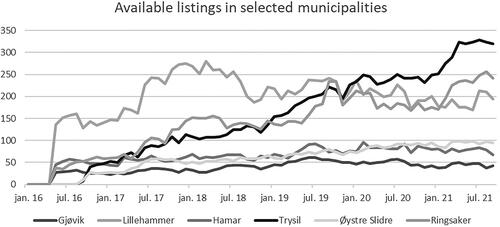

Figure 3. Number of Airbnb listings in selected municipalities in Innlandet county (January 2016–July 2021). Source: Airdna.

Airbnb has grown in the largest towns (Lillehammer, Hamar and Gjøvik) and in the peripheral municipalities (e.g. Trysil, Øystre Slidre and Ringsaker) in the county, probably because of tourism and the high number of second homes (). The platform mainly offered cabins (40%). Trysil has the highest number of units (17% of the total). From July 2020 to July 2022, 995 units and 1,538,192 room nights were available in Innlandet. Of these, 359,195 room nights were booked. Each unit's revenue was approximately EUR 8425 during the past 12 months (Capia, Citation2021).

Design, data collection and analysis

Twenty-four semi-structured interviews were held with key tourism stakeholders representing four groups (Uzunca et al., Citation2018): consumers, Airbnb hosts, incumbent firms and regional industry and policy actors (). The informants were recruited in various ways. For example, the consumers were recruited through a survey conducted by the CreaTur project (a Norwegian research project about the sharing economy in Innlandet county), and the hosts were recruited through their Airbnb listening. Common to all four groups was that many actors were contacted via email, but relatively few responded, even though follow-up emails were sent. This made it challenging to get a sufficient number of informants. Nevertheless, we are satisfied with the data material we generated.

Table 1. Key stakeholders interviewed (Source: Author).

The interviews were conducted in August, September and October in 2021. An interview guide was developed for each stakeholder group and used as a basis for the interviews. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic and resource constraints, most interviews were conducted online using Microsoft Teams (with the camera on). The interviews lasted an average of 30 minutes, and all were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. A six-phase analysis inspired by Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2012) thematic analysis was conducted, as such an analysis is suitable when investigating under-researched themes. We started by familiarising ourselves with the data, by generating codes, searching for and reviewing themes, as well as defining and naming themes, before ending with the final phase, which was the write-up. The three aspects of legitimacy (regulative, normative and cognitive) were used as the analytical framework for the analysis.

The role of legitimation and delegitimation in new path development

This paper started by posing two research questions. RQ1 is discussed in the next section by presenting the key themes that emerged in the analysis. The following section (The effects of legitimation and delegitimation on new path development) aims to answer RQ2 by building on the findings and discussions from RQ1.

Cognitive legitimacy

The data show that most stakeholders had positive feelings about Airbnb and the SE. All the stakeholders were familiar with the Airbnb brand, thereby strengthening Airbnb’s cognitive legitimacy. The consumers reported that choosing Airbnb or traditional forms of accommodation depended on the purpose of their trip; hotels were preferred when they were travelling with their partners, but Airbnb was preferred when travelling with their children, extended family or friends. Price and space were also decisive. However, a few consumers admitted that they were unfamiliar with Airbnb and had forgotten that Airbnb was an option when travelling:

I was travelling with my friends last weekend, but we didn’t know that [Norwegian tourist destination] was so popular. We knew there were a lot of people there, though we didn't know that everything was booked and occupied. But we didn’t check Airbnb. It's not something that my friends and I would usually do. We didn’t think about it all weekend, not even when we got home. Not before now (interview data, users).

Regulative legitimacy

Taxation and regulation are commonly discussed themes in the sharing economy (e.g. Agarwal & Steinmetz, Citation2019) and were also discussed in the interviews. Short-term accommodation has been more strictly regulated in Norway and other countries over the last five years, which has increased the regulative legitimacy of incumbent firms and stopped a black economy from emerging. The consumers described this as favourable because it makes Airbnb a safer and more professional option.

The stakeholders criticised Airbnb for benefitting from local tourist firms and DMMO investments in the region without contributing funds for public goods, marketing, or the country because Airbnb is headquartered abroad. Also, Airbnb does not report statistics to Statistics Norway (the National statistics office of Norway), making it challenging to calculate the number of guest nights in the region. Several respondents described that Airbnb does not contribute funds for public goods: ‘These platforms enter the market with a free pass. They have not invested in the market; we have invested!’ (interview data, incumbent firms). Incumbent firms demanded that there should be equal rules and conditions for taxation and value-added tax for all the different kinds of accommodation services to avoid the revenue stream flowing out of the region and country. Other stakeholders described the same issue: ‘Because these companies pay no tax on their profits to the Norwegian Tax Administration, nothing comes back; it [sharing economy] is not a good solution’ (interview data, regional industry and policy actors). The consumers echoed this view by questioning the sharing economy’s ethical perspectives and claiming that the sharing economy occupies in a grey zone between legal and illegal business, arguing that the sharing economy is sometimes part of a black economy in terms of taxation. These consumers feared that sharing economy businesses would oust traditional companies competing on other terms. These issues were described as one of the sharing economy’s main challenges, as they implied regulative legitimacy issues (Ackermann et al., Citation2021).

The distortion of competition was another key theme during the interviews. Regional industry and policy actors were concerned about the distortion of competition and described it as a challenge resulting from insufficient regulation, implying low regulative legitimacy. However, the government’s adjustments have made the sharing economy more acceptable. The tax system in Norway is considered legitimate, which gives Airbnb more legitimacy as part of a fair tax system. Nonetheless, Airbnb exacerbates distortion of competition:

Obviously, there is still a distortion of competition, but at least the authorities have made a conscious choice, meaning this is an ok regulation. I think it’s undoubtedly positive for Airbnb because it was somewhat little challenging to talk in positive terms about Airbnb when you knew the sharing economy was unregulated. There was a lot of tax evasion and so on (interview data, regional industry and policy actors).

The consumers and hosts questioned service fees. Hosts pay a service fee of 3% on each booking, and guests pay approximately 14.2% (Airbnb, n.d.-b). Service fees were described as a general social issue for digital platforms because they create economic leakages to foreign countries, which calls into question the regulative legitimacy of Airbnb. In contrast, most hosts described the service fee charged by Airbnb as reasonable, considering what they receive in terms of marketing and secure payment solutions and because hosts only pay when a booking is made and not for advertising. However, the hosts highlighted that fees raise costs for consumers and are seldom taxed in the country where the transaction takes place (Hwang, Citation2019), which they described as irritating and a regulatory issue. One of the hosts was very frustrated:

The weekly price I’ve set (…) increases by 17% … Airbnb didn’t inform me about this. People have to pay a lot to stay here. I don’t like it, nor the fact that it goes abroad. I would rather pay more tax here. I understand that they should profit from this … but they’re well paid. (interview data, hosts).

Given the disruptive potential of the sharing economy (Kuhzady et al., Citation2021) and loosely regulated worldwide institutional support structures (Hwang, Citation2019), we suggest that the sharing economy is in an early stage of its life cycle as a radical innovation which is new to the world (Binz & Gong, Citation2021), despite one of the first sharing economy companies being established as early as 2008 (Airbnb). In contrast to NTR industries, NTW industries cannot rely on previous development and successful establishment in other contexts, making it more challenging to achieve legitimacy. Binz and Gong (Citation2021) highlight that NTW industries depend on active system-building agency in terms of regulative frameworks to be legitimate. This study is aligned with the study of Binz and Gong (Citation2021) by demonstrating that regulative aspects challenge sharing economy legitimacy. The stakeholders have called for changes in regulations to create a balanced competitive environment and maintain the vibrancy of tourist destinations because the sharing economy could undermine the existing tourism industry and avoid the distortion of competition. In order to develop, the sharing economy needs substantial institutional and policy support.

Normative legitimacy

Several hosts admitted that they considered making their own contracts instead of using Airbnb because of Airbnb’s poor customer service and fees. This raises normative legitimacy issues because the hosts ignore the platform’s guidelines by not respecting its rules (Ackermann et al., Citation2021).

The stakeholders have seen examples from cities such as Barcelona and Venice, where house prices have increased in areas with a strong Airbnb presence: ‘We read a lot about places like Barcelona and Venice, where cultural sustainability has been under pressure. We’re not going to contribute to that’ (interview data, consumers). Moreover, the stakeholders described the increased presence of Airbnb, which makes it difficult for residents and students to find permanent residences. Airbnb tourists have taken over entire neighbourhoods, resulting in anti-tourist campaigns. Issues regarding house prices raise normative legitimacy problems, as established house prices can no longer be counted on (Ackermann et al., Citation2021). Descriptions of Airbnb problems in other settings, combined with the stakeholders’ own experiences, demonstrate that negative spillover effects from one context can reduce an emerging industry’s legitimacy in another (Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022).

Potential consumers viewed Airbnb as a balanced alternative to traditional forms of accommodation, but whether they perceived Airbnb as a competitor or a supplementary provider varied from one consumer to the next. Airbnb was described as a competitor in urban settings. In contrast, several of the stakeholders reported a more positive sentiment towards Airbnb in the countryside because Airbnb provided an opportunity in regions that had few accommodation providers, demonstrating that legitimacy depends on context (Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022):

I’m more positive towards Airbnb in the countryside because it doesn’t compete with other industries to the same extent. It offers people a homestay and experience of Norwegian culture while giving [the inhabitants] a supplementary income (interview data, consumers).

The stakeholders argued that Airbnb could offer another kind of experience, access to ‘hidden’ locations, and proximity to local knowledge and inhabitants. The regional industry and policy actors appeared to agree with the potential consumers’ views. They were more optimistic about the opportunities related to the sharing economy for rural tourism in sparsely populated areas. Airbnb can positively influence regional development in rural regions because consumers using Airbnb also use other services in the region, a finding that was also described by Battino and Lampreu (Citation2019).

The effects of legitimation and delegitimation on new path development

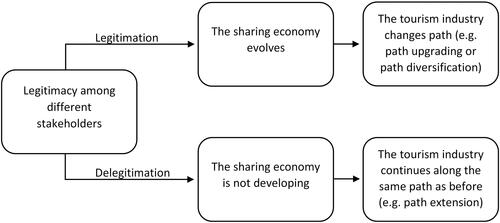

The analysis demonstrates that the sharing economy in Innlandet is characterised by issues concerning all three aspects of legitimacy, indicating that the sharing economy is characterised by delegitimation by most of the informants. Legitimacy is considered a key process for new path development, particularly for early path creation (Binz et al., Citation2016) and emerging industries (Heiberg et al., Citation2020; Jolly & Hansen, Citation2022; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). A lack of legitimacy (delegitimation) may prevent the development of new paths, and the tourism industry continues along the same path as before (path extension). Hence, there is less reason to believe that the sharing economy will make transformative changes in the regional tourism industry in Innlandet (). Conversely, the sharing economy would likely expand if it achieved legitimacy among key tourism stakeholders. An expanded sharing economy could challenge the region’s traditional tourism industry (also ), as we have seen in examples from other contexts (e.g. Barcelona and Venice). We do not argue that the sharing economy on its own can initiate an entirely new path through path creation. It is more likely that the sharing economy can initiate renewal processes in the existing tourism industry, for example, by implementation of new technologies or new business models that change the existing tourism industry into a new direction (path upgrading), or by diversifying the existing tourism industry, which for example can be triggered by incumbent firms moving into related industries through path diversification (Asheim et al., Citation2019).

Even though we argue that the region's sharing economy is characterised by delegitimation, Airbnb is currently growing ( and ). Hence, legitimacy among all stakeholders is not necessary for innovations to succeed. Stakeholders have different roles and influence on new path development. Previously, the literature on EEG has primarily focused on the role of firms (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018), but the role of demand has also recently been in focus (Martin et al., Citation2019). Martin et al. (Citation2019) describe the importance of the demand side by referring to examples from the literature on sharing economy in which local demand (e.g. for car-sharing services) has spurred the emergence of new services and infrastructure in a region (e.g. Cohen & Muñoz, Citation2016), and thus caused the importation of new paths (path importation). The sharing economy business model is triadic and comprises sharing platforms, resource owners (hosts) and resource users (consumers) (Curtis & Mont, Citation2020). We consider it less critical that the sharing economy achieve legitimacy among incumbent firms than among hosts and consumers, as the latter two groups constitute the demand side of the SE. Hence, in investigations of the SE’s legitimacy, we believe it is vital to emphasise the demand side, as the users drive the sharing economy forward. If hosts do not legitimise the SE, it will result in a lack of supply; if consumers delegitimise the SE, this will result in a lack of demand. We have seen that both consumers and hosts have raised questions concerning several aspects of the SE, which align with the points made by Binz et al. (Citation2016): emerging industries risk legitimacy issues and thus fail to create user acceptance. These findings contribute to a broader understanding of the role of legitimacy in new path development processes by taking individual actors into account and emphasising that stakeholders play different roles in new path development. Moreover, the article offers knowledge about the influence of legitimation, and particularly delegitimation, among stakeholders on the development of innovations in the tourism industry.

Conclusion

This paper started by posing two research questions. RQ1 asks how the legitimacy of Airbnb is expressed among key tourism stakeholders in a tourism region in Norway. All stakeholder groups critiqued various aspects of Airbnb, describing cognitive, regulative and normative legitimacy issues. The issues are mainly related to regulative and normative ambiguities arising from unfair regulations and conditions that result in economic leakage and concerns about reduced local value creation because of the SE. These findings indicate that the sharing economy is characterised by delegitimation among key regional stakeholders.

RQ2 asks how the shifting roles of legitimation and delegitimation among key stakeholders in the tourism industry inform the literature on new path development.

The legitimacy issues found in RQ1 describe the role of legitimation and delegitimation in new path development processes. Legitimacy promotes path development through a belief in local value creation, as well as economic, environmental and idealistic logic. In contrast, the delegitimation restrains development through calls for new regulations, tax claims and concerns about reduced local value creation. The findings demonstrate that the shifting roles of legitimation and delegitimation can inform the literature on new path development. The article’s main argument is about the role of delegitimation in new path development. The article contributes to the literature by arguing that delegitimation prevents transformative changes and new path development. If the sharing economy is considered legitimate by key tourism stakeholders, it will likely be strengthened. An expanded sharing economy could challenge the traditional tourism industry in the region over time, thereby changing the dynamics of the industry. However, it is not expected that the sharing economy on its own can create an entirely new path. New path development through, for example, path upgrading or path diversification is more likely to occur. These findings show that the sharing economy can open or close regional development processes differently, depending on legitimation and delegitimation. Moreover, stakeholders play different roles in new path development. We argue that the demand side has considerable influence in the sharing economy because demand drives the sharing economy forward. However, we assume that subversive growth, and thus new path development, require legitimacy among all stakeholders.

There has been little previous research on the role of delegitimation in new path development. Future studies on new path development must focus more on delegitimation to understand processes that encourage or prevent regional development. Moreover, legitimacy is culturally embedded, and further research is required in other regions and industries. Finally, the effects of legitimation and delegitimation on new path development should be quantitatively tested in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kristine Blekastad Sagheim

Kristine Blekastad Sagheim is a Ph.D. candidate at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research interests include regional development in rural regions, innovation, tourism, and sharing economy.

Notes

1 Airdna is an analytics firm specialising in short-term rentals. The data were received upon special request by the research team. Data from Homeaway/Vrbo are also included in the dataset from Airdna. The historical data for Norway provided by Airdna only date from 2016. Thus, the beginning of the sample may not include all actual listings.

2 The consumers were recruited from a survey conducted by CreaTur. They were not required to have been previous consumers of Airbnb. Thus, both direct and indirect experiences of the platform were described.

References

- Ackermann, C.-L., Matson-Barkat, S., & Truong, Y. (2021). A legitimacy perspective on sharing economy consumption in the accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(12),1947–1967. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1935789

- Acquier, A., Daudigeos, T., & Pinkse, J. (2017). Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006

- Adamiak, C. (2019). Current state and development of Airbnb accommodation offer in 167 countries. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1696758

- Agarwal, N., & Steinmetz, R. (2019). Sharing economy: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 16(06), 1930002–1930017. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877019300027

- Airbnb. (2016). Airbnb in Norway - An Overview (report in Norwegian). https://www.yumpu.com/no/document/read/55268779/airbnb-i-norge-et-overblikk

- Airbnb. (n.d.-a). Responsible hosting in Norway. https://www.airbnb.com/help/article/2477/responsible-hosting-in-norway?locale=en

- Airbnb. (n.d.-b). What are Airbnb service fees? https://www.airbnb.co.uk/help/article/1857/what-are-airbnb-service-fees?_set_bev_on_new_domain=1633955870_NWM5ZmU0ZDhkYzJm

- Asheim, B. T., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Advanced introduction to regional innovation systems. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2012). Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 881–898. https://doi.org/10.1086/666376

- Battino, S., & Lampreu, S. (2019). The role of the sharing economy for a sustainable and innovative development of rural areas: A case study in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability, 11(11), 3004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113004

- Belezas, F., & Daniel, A. D. (2022). Innovation in the sharing economy: A systematic literature review and research framework. Technovation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102509

- Belk, R. (2014). Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0. The Anthropologist, 18(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891518

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. (2019). Is Airbnb bad for hotels? Current Issues in Tourism, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1646226

- Binz, C., & Gong, H. (2021). Legitimation dynamics in industrial path development: New-to-the-world versus new-to-the-region industries. Regional Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861238

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2018). Evolutionary economic geography. In G. L. Clark, M. P. Feldman, M. S. Gertler, & D. Wójcik (Eds.), The new Oxford handbook of economic geography. (pp. 213–230). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755609.013.11

- Boschma, R., & Martin, R. (2010). The handbook of evolutionary economic geography. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849806497

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Brouder, P. (2017). Evolutionary economic geography: Reflections from a sustainable tourism perspective. Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1274774

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Brown, R. S. (2012). The role of legitimacy for the survival of new firms. Journal of Management & Organization, 18(3), 412–427. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2012.18.3.412

- Baekkelund, N. G. (2021). Change agency and reproductive agency in the course of industrial path evolution. Regional Studies, 55(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291

- Capia. (2021). Report Innlandet Airbnb July 2021 (in Norwegian). Capia.

- Caple, J. (2014). How Lillehammer set the standard. https://www.espn.com/olympics/winter/2014/story/_/id/10412036/2014-sochi-olympics-why-1994-lillehammer-olympics-were-best-winter-games-ever

- Cohen, B., & Muñoz, P. (2016). Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: Towards an integrated framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.133

- Curtis, S. K., & Mont, O. (2020). Sharing economy business models for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 266, 121519–121772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121519

- Davidson, N. M., & Infranca, J. J. (2015). The sharing economy as an urban phenomenon. Yale Law & Policy Review, 34, 215.

- Frenken, K., & Schor, J. (2017). Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003

- Frenken, K., Waes, A., Pelzer, P., Smink, M., & Est, R. (2019). Safeguarding public interests in the platform economy. Policy & Internet, 121(800), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.217

- Gong, H., Binz, C., Hassink, R., & Trippl, M. (2022). Emerging industries: Institutions, legitimacy and system-level agency. Regional Studies, 56(4), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2033199

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., & Trippl, M. (2018). Unrelated knowledge combinations: The unexplored potential for regional industrial path development. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy012

- Guttentag, D. (2015). Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(12), 1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

- Guttentag, D. A., & Smith, S. L. (2017). Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotels: Substitution and comparative performance expectations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.02.003

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Heiberg, J., Binz, C., & Truffer, B. (2020). The geography of technology legitimation: How multiscalar institutional dynamics matter for path creation in emerging industries. Economic Geography, 96(5), 470–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1842189

- Hwang, J. (2019). Managing the innovation legitimacy of the sharing economy. International Journal of Quality Innovation, 5(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40887-018-0026-0

- Isaksen, A., & Jakobsen, S.-E. (2017). New path development between innovation systems and individual actors. European Planning Studies, 25(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1268570

- Jolly, S., & Hansen, T. (2022). Industry legitimacy: Bright and dark phases in regional industry path development. Regional Studies, 56(4), 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861236

- Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2016). The rise of the platform economy. Issues in Science and Technology, 32(3), 61–69.

- Kuhzady, S., Olya, H., Farmaki, A., & Ertaş, Ç. (2021). Sharing economy in hospitality and tourism: A review and the future pathways. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(5), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1867281

- Leick, B., Eklund, M. A., & Kivedal, B. K. (2020). Digital entrepreneurs in the sharing economy: A case study on Airbnb and regional economic development in Norway. In A. Strømmen-Bakhtiar & E. Vinogradov (Eds.), The impact of the sharing economy on business and society. (pp. 69–88). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429293207-6

- Leick, B., Kivedal, B. K., Eklund, M. A., & Vinogradov, E. (2021). Exploring the relationship between Airbnb and traditional accommodation for regional variations of tourism markets. Tourism Economics, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816621990173

- Light, A., & Miskelly, C. (2015). Sharing economy vs sharing cultures? Designing for social, economic and environmental good. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal, 24, 49–62.

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- MacKinnon, D., Karlsen, A., Dawley, S., Steen, M., Afewerki, S., & Kenzhegaliyeva, A. (2021). Legitimation, institutions and regional path creation: A cross-national study of offshore wind. Regional Studies, 54(4), 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861239

- Martin, H., Martin, R., & Zukauskaite, E. (2019). The multiple roles of demand in new regional industrial path development: A conceptual analysis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(8), 1741–1757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19863438

- Meelen, T., & Frenken, K. (2015). Stop saying Uber is part of the sharing economy. https://www.fastcompany.com/3040863/stop-saying-uber-is-part-of-the-sharing-economy

- Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (2017). Mapping out the sharing economy: A configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.035

- Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (2018). A compass for navigating sharing economy business models. California Management Review, 61(1), 114–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125618795490

- Newlands, G., & Lutz, C. (2020). Fairness, legitimacy and the regulation of home-sharing platforms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(10), 3177–3197. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2019-0733

- Norwegian Hospitality Association. (2020). Numbers and facts about the tourism industry (in Norwegian). https://www.nhoreiseliv.no/tall-og-fakta/

- Sandberg, E., Bjelle, E. L., Kvellheim, A. K., Ekambaram, A., Vik, L., & Hatling, M. (2020). Analysis of Siva's incubators in the Innlandet region (in Norwegian). SINTEF. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2724243

- Schlagwein, D., Schoder, D., & Spindeldreher, K. (2019). Consolidated, systemic conceptualization and definition of the sharing economy. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(7), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24300

- Schor, J. (2015). The sharing economy: Reports from stage one.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard Univeristy Press.

- Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A., & Vinogradov, E. (2019). The effects of Airbnb on hotels in Norway. Society and Economy, 41(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2018.001

- Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A., Vinogradov, E., Kvarum, M. K., & Antonsen, K. R. (2020). Airbnb contribution to rural development: The case of a remote Norwegian municipality. International Journal of Innovation in the Digital Economy, 11(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJIDE.2020040103

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

- Thebault-Spieker, J., Terveen, L., & Hecht, B. (2017). Toward a geographic understanding of the sharing economy: Systemic biases in UberX and TaskRabbit. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 24(3), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/3058499

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Uzunca, B., Rigtering, J. P. C., & Ozcan, P. (2018). Sharing and shaping: A cross-country comparison of how sharing economy firms shape their institutional environment to gain legitimacy. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(3), 248–272. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0153

- Vestrum, I., Rasmussen, E., & Carter, S. (2017). How nascent community enterprises build legitimacy in internal and external environments. Regional Studies, 51(11), 1721–1734. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1220675

- Vinogradov, E., Leick, B., & Kivedal, B. K. (2020). An agent-based modelling approach to housing market regulations and Airbnb-induced tourism. Tourism Management, 77, 104004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104004

- Vith, S., Oberg, A., Höllerer, M. A., & Meyer, R. E. (2019). Envisioning the ‘sharing city’: Governance strategies for the sharing economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(4), 1023–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04242-4

- Zach, F. J., Nicolau, J. L., & Sharma, A. (2020). Disruptive innovation, innovation adoption and incumbent market value: The case of Airbnb. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102818

- Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. (2017). The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0204

- Zimmerman, M. A., & Zeitz, G. J. (2002). Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. The Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 414–431. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.7389921