Abstract

The Margaret River region (Western Australia) is a popular international tourism destination. Since its emergence in the late 19th century, tourism in the Margaret River region (MRR) has interacted with a number of regional industries including timber, dairy, and wine. These interactions have changed from ‘supportive’ to ‘competing’ reflecting various changes in the market and the availability of common local assets such as forest, land, and public funding. While timber and dairy had an important influence on the evolution of tourism in the region, it was the emergence of wine that shifted tourism the most.

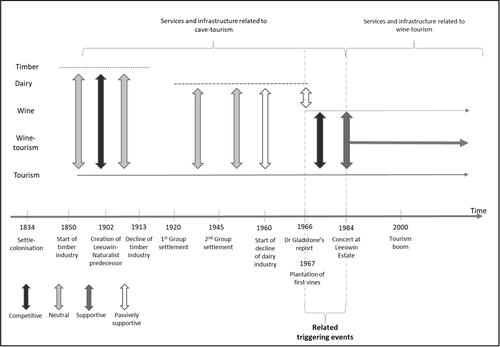

Using selected concepts of evolutionary economic geography (EEG), mainly path-dependence, path-reformation, interpath relations, and triggering events, this paper demonstrates how tourism has interacted with different other industries and how these interactions have shaped the MRR as a wine-tourist destination. The paper shows how two related triggering events contributed to the emergence of wine-tourism as a new path in the region – a process referred to as ‘path-blending’. In this respect, the paper provides empirical evidence that triggering events can result in multiple new paths and can also significantly shape the relations between new and existing regional paths. As such, the paper responds to the call for breaking away with the ‘single-path view’ in research on industrial evolution, and for more attention to the various relations between tourism and other sectors within a tourist destination.

Introduction

As a global phenomenon, tourism promotes the transformation of regions into places attractive to tourists, i.e. tourist destinations (Saarinen, Citation2004). Certainly, the transformation of tourist destinations has social, cultural, economic, and environmental regional implications (Brouder et al., Citation2016; CitationL’equipe MIT, 2002). As such, attention must be paid to how destinations transform over time and the mechanisms behind that transformation (Sanz-Ibáñez & Anton Clavé, Citation2014). To enhance the general understanding of how and why such transformation (or, shall we say, evolution?) occurs has been a key objective of multiple studies using various theoretical lenses—from Butler’s (Citation1980) tourism area life cycle (TALC) model to the recent adoption and popularisation of evolutionary economic geography (EEG) (Brouder, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013a). Indeed, various EEG concepts—mainly those related to path-dependence—have secured a strong place in the analysis of how tourist destinations evolve (e.g. Bramwell & Cox, Citation2009; Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013b; Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Halkier & James, Citation2017; Ma & Hassink, Citation2014; Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017; Yang et al., Citation2017). Yet, most empirical studies have neglected the interactions between tourism’s development and other economic paths within a region (see Breul et al., Citation2021; Stihl, Citation2022 for exceptions).

More recently, one of the aims of EEG inter alia has been to understand how emerging industries interact with pre-existing industries in the same region (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019). While research on those interactions is still incipient, early studies have made relevant insights into competitive and synergic interpath relationships between emerging and preexisting paths (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019), and the influence of place-specific factors on interpath relations (Frangenheim, Citation2022). Building on these developments, Breul et al. (Citation2021) and Stihl (Citation2022) address the emergence of tourism as a regional economic path and how it interacts with other preexisting sectors such as agriculture and mining. Building upon these studies, this paper aims to respond to the question what have been the interpath relations between tourism and other regional industries in the Margaret River region (MRR) since its emergence as a tourist destination in the late 19th century?

Drawing from semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis, this paper adopts EEG (particularly the notions of path-dependence, path-creation, path-expansion, and interpath relations), to analyse the evolution of the MRR (Western Australia) from a cave-focused destination to a popular international wine-tourism destination. Building on Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) and Breul et al. (Citation2021) frameworks, this paper identifies both competitive and synergic relationships between tourism and other regional industries (e.g. timber, dairy, and wine), discusses the influence of triggering events on the development of wine-tourism, and opens the debate about the long-term effects of path-expansion. It is shown that the close and continuous interaction between tourism and the wine industry in the Margaret River region has generated a distinctive, place-specific wine-tourism path that substantially differs from the pre-existing tourism and wine industries. The paper refers to this particular process as path-blending. In addition to path-blending as a theoretical contribution to the literature on interpath relations, the paper also suggest that path-dissolution has been an overlooked factor in Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) and Breul et al. (Citation2021) frameworks.

The remainder of this paper consists of six sections. The following two sections discuss the main body of theory that this paper utilises. While the first section presents relevant EEG concepts, including interpath relations, the second one discusses the concept of triggering events and their role in the evolution of tourist destinations. In order to set the scene, the following section briefly introduces the MRR. The next section explains our methodology. The penultimate section presents the research findings and discusses their relevance and implications. The final section offers conclusions.

Interpath relations in tourist destinations

The notion of interpath relations is one of the most recent developments within the EEG paradigm (Breul et al., Citation2021; Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019). Hence, before addressing this concept, this section will briefly discuss all key EEG concepts that are relevant for the understanding of interpath relations.

Path-dependence, path-creation, and path-dissolution have been extensively analysed in EEG studies (e.g. Boschma & Frenken, Citation2006; Martin, Citation2009; Martin & Sunley, Citation2012; Schienstock, Citation2007). Their applicability to the analysis of tourist destinations has also been recognised (Brouder, Citation2014b; Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013a). A useful approach to integrate these concepts is Martin and Sunley (Citation2006, p. 408) ‘path-as-process’ approach (see also Benner, Citation2022; Martin, Citation2009), which suggests that path-dependence, path-creation, and path-dissolution are often part of the same continuum where actors strive to initiate new regional path trajectories (for instance through diversification) in order to avoid being locked-in to configurations that are not optimal for their region’s future. Building on this view, Martin (Citation2009) proposed a path-dependence model of local industrial evolution wherein four phases are distinguished: preformation, path-creation, path-development, and path-dependence, with two possible scenarios of path-dependence—one leading to stasis (rigidification) or even decline (path-dissolution), and one fostering dynamic changes leading to path-renewal or new path-creation. Recognising that the evolution of a tourism destination is ‘a dynamic open path-dependent process by which products, sectors, and institutions co-evolve along unfolding trajectories’, Ma and Hassink (Citation2013, p. 98) applied Martin’s (Citation2009) model to tourism destination evolution, using the example of Gold Coast in Australia (see also Ma & Hassink, Citation2014, for the case of Guilin, China). As such, Ma and Hassink (Citation2013) model complements Butler’s (Citation1980) TALC theory by drawing more attention to the reasons behind the emergence or decline of tourism destinations.

While this model convincingly introduces the key notions of EEG—particularly path-dependence—into the evolution of tourist destinations, it should be also recognised that tourism, as other industries, does not emerge in isolation, but instead it interacts with other sectors within a region (Brouder et al., Citation2016). As Martin and Sunley (Citation2006) observed, each region is a complex configuration of firms, industries, and technologies, and each individual component may be following its own path-dependent trajectory. If sectors interact with each other and develop linkages (which is a fairly common scenario in a regional context), the region may exhibit a degree of ‘multiple related path-dependence’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006). Furthermore, if such linkages make two sectors complementary to each other and help them grow in a mutually-reinforcing way, such a condition is referred to as ‘path-interdependence’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2012, Citation2006). Building on the latter, concepts such as related and unrelated variety have emerged to conceptualise the relations between regional industries (Frenken et al., Citation2007; Neffke et al., Citation2011). Both concepts aim to explain the emergence, diversification, and exit of regional industries based on their technological and skill relatedness with preexisting industries (Hassink, Citation2010; Neffke et al., Citation2011). However, due to the fact that both concepts predominantly focus on endogenous factors at the firm level, they fall short of addressing path interactions (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Hassink et al., Citation2019).

As a result, Hassink et al. (Citation2019) proposed a fine-grain approach to interpath relations that considers both supportive and competing relationships between different paths. For instance, industries (whether emerging or established) may need to compete for scarce regional resources (e.g. skilled labour, private capital, or governmental support) and the relations between them may be therefore antagonistic, rather than supportive, as often portrayed. Building on this, Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) and Breul et al. (Citation2021) developed two frameworks that are pertinent to this paper. Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) focused on interpath relations between emerging regional paths in terms of access to markets and regional assets (e.g. knowledge, place-based values, labour, capital), showing that emerging industries may depend on similar or different markets, or similar or different (abundant or scarce) assets. This can lead to strong or weak interpath relations which can evolve over time due to changes in the industrial paths of the respective sectors, the availability of assets, or changing market dynamics (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020).

Breul et al. (Citation2021), in turn, paid attention to the influence that emerging paths can have on established ones. The influence of emerging paths on preexisting sectors can result in different types of path-reformation (i.e. negative path-development, path-expansion, and path-renewal) that can occur simultaneously (Breul et al., Citation2021). Negative path-development refers to the decline of an existing path due to the formation of a new one (e.g. competition for the same scarce resources). Path-expansion occurs when the formation of a new path leads to positive multiplier effects on the existing paths (e.g. creation of a complementary market). Path-renewal refers to the positive impact on the existing path due to the introduction of new related assets into the region and the formation of a new path (e.g. an emergence of a new related technology in the region). Finally, Breul et al. (Citation2021) also indicated that the formation of a new path may not influence the existing paths (no reformation). presents a summary of both frameworks. Importantly, all these concepts can be easily applied to tourism. For instance, Stihl (Citation2022) demonstrated how the emerging tourism path in Kiruna (Sweden) developed a (temporarily) competitive relationship with the established mining sector to the benefit of the local municipality. Indeed the competition for local labour triggered increasing investments on the region from both sectors. Breul et al. (Citation2021), in turn, showed how an emerging tourism path triggered parallel reformation process in the Zambezi region (Namibia). On the one hand tourism brought new knowledge and investment to, thus initiating path-expansion and path-renewal in the established agricultural sector. Whereas, on the other hand, negative path-development occurred as agriculture and tourism competed for the same scarce resource (land).

Table 1. Types of regional path-reformation as a result of emerging paths.

Finally, it is important to reflect on the role of agency of firms and non-firm actors (e.g. policy-makers or universities) in shaping interpath relations, (Boschma, Citation2017; Frangenheim et al., Citation2020; Stihl, Citation2022; Trippl et al., Citation2018). For instance, actors from industries supplying different markets but relying on the same abundant or scarce assets can mobilise their actions in three different ways: intensify the competition with the other path (such as through selective lobbies), establish supportive relations with the other path (such as by initiating collaborative actions), or attempt to dissolve the interaction with the other path (such as by means of relocating to a different region or creating new assets) (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020). While agency indeed plays a pivotal role in these processes, this paper suggests that interpath relations can also be influenced by various triggering events. These types of events are addressed in the next section.

Triggering events and tourism

Although EEG-informed studies have traditionally paid more attention to the role of geographically and historically embedded factors (e.g. pre-existing conditions, institutions or the agency of actors) in shaping regional paths, rather than those related to chance such as historical events or unintended consequences of agents’ actions that can only be noticed ex post (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Sydow et al., Citation2012), the concept of triggering events has recently gained much more prominence in the EEG literature. Triggering events, far from being be small and random (see David, Citation1985), are defined as decisive and powerful incidents and therefore capable of inducing single or multiple new paths of growth (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017; Sydow et al., Citation2012).

As such, while not preponderant, the concept of triggering events has also found a place in research on the evolution of tourist destinations. For instance, Laws and Prideaux (Citation2006, p. 6) define triggering events as ‘the origin of crisis’, whether produced by humans or natural forces. In this respect, triggering events are conceptualised as unexpected natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and global economic crises (Laws & Prideaux, Citation2006; Ritchie et al., Citation2014). However, although this definition has a negative connotation, triggering events can also have an immediate positive transformative impact on a destination (Baggio & Sainaghi, Citation2011), allowing or contributing to the emergence of new tourism-related paths. For instance, Ma and Hassink (Citation2014, Citation2013) tourist destination evolution model assumes that new paths of tourism development are shaped both by triggering events and initial conditions such as preexisting natural or cultural resources. In their analysis of the Guilin tourist destination endogenous triggering events were found to contribute to the internationalisation of the place. In turn, Gill and Williams (Citation2016) identified exogenous triggering events as important catalysts for change, and therefore, as enablers of path-creation. Their study infers that triggering events may require an enabling context to stimulate a change in the destination. Closely related to triggering events is Butler’s (Citation2014) notion of triggers. These triggers (such as political change, sudden resource shortages and economic unrest) have the potential to shift the destination towards a new path of development. More recent developments concerning triggering events can be found in the moments approach (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017). This approach proposes that triggering events are not necessarily spontaneous (Laws & Prideaux, Citation2006; Ritchie et al., Citation2014), but could also be selective in nature (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017). In other words, intentional decisions of key stakeholders such as endogenous regulatory policies or exogenous investment strategies can also be conceptualised as triggering events.

Overall, these studies suggest that triggering events, whether endogenous or exogenous or whether spontaneous or selective, can foster shifts in tourist destinations (either positive or negative) if the existing conditions facilitate them. Nonetheless, triggering events might not be noticed when they occur. While they may be seen as small, unrelated, and insignificant when they happen, their true effects may only be noticed once they are ‘rationalised by hindsight’ (i.e. in retrospective) (Baggio & Sainaghi, Citation2011, p. 844) by actors engaged with the path or by external observers (Sydow et al., Citation2012).

Further to the discussion of interpath relations, it is pertinent to analyse the role and nature of triggering events in the interactions between tourism and other industries. As the example of the MRR below shows, triggering events in tourism destinations might not necessarily be related to tourism, but, instead, they can originate from unrelated industries. Before this argument is developed further, the next section introduces the area of study in more detail.

The Margaret River region as a tourist destination

The Margaret River region (MRR) is a popular tourist destination that encompasses two non-metropolitan local government areas—The City of Busselton and The Shire of Augusta Margaret River (see ). As such, it overlaps with the so-called Margaret River wine region. The MRR lies 250 km south of Perth (approximately 3 hours by car) in the southwestern corner of Western Australia (WA) and has a population of 50,875 people according to the last census data (ABS, Citation2016). The region is known for its scenic natural environment (beaches, coastal plains, large eucalyptus forests, geological formations along the coast) and important archaeological sites of Wardandi Noongar (the traditional custodians whose Country includes the MRR) and European settlements, both of which account for the region’s cultural heritage (Jones et al., Citation2015, Citation2010; Sanders, Citation2006).

In the late 20th century the MRR also became an attractive destination for various new residents (Sanders, Citation2006). The region witnessed an impressive increase in population from 13,049 in 1981 to 31,911 in 2001, and it has since maintained a steady demographic growth (Sanders, Citation2006). Tourism in the MRR plays an important role as a regional economic driver and a source of direct and indirect employment for around 20% of the region’s population (MRBTA., Citation2019). It suffices to say, in 2018-2019 the MRR received 2.89 million domestic and international visitors (1.30 million day-trippers and 1.59 million overnight visitors). In turn, the Margaret River wine region, which accounts for 900 cellar doors, is one of the main high-quality wine exporters in Australia. As such, it is the most visited wine region in Australia for domestic travellers and one of the top three Australian wine regions for international visitors (MRWIA, Citation2020).

Methodology

The paper uses a qualitative single case study methodology (Yin, Citation2003) to follow the evolution of tourism in the MRR since the late 19th century, address its interactions with other regional industries, and identify the events that triggered the rise of wine-tourism. The case study utilised two methods of data collection: documentary analysis and semi-structured interviews. The former encompassed various publicly available sources including newspaper and magazine articles, institutional reports, and websites of tourism-related institutions and firms dating back to 1848 (only fourteen years after the first settlement in the MRR) (see Perth Gazette, Citation1848). The main databases included the National Library of Australia, ProQuest database, and Factiva, with the following searching codes used: ‘tourism’, ‘timber’, ‘dairy’, ‘caves’, ‘wine’, ‘wine-tourism’, ‘Margaret River’, and ‘Busselton’. All the documents were organised chronologically.

The second method encompassed 51 semi-structured interviews (with 54 tourism stakeholders within and outside the MRR) that were conducted online between February 2021 and June 2021, except for one that took place in February 2022 (). At the initial stage, respondents were selected according to the rule of purposive sampling (i.e. based on their historical knowledge of and professional involvement in the local tourism industry). However, at a later stage, the project also relied on the initial respondents’ recommendations, according to the snowballing rule (Valentine, Citation2005). Importantly, most of the respondents have resided in the MRR since the 1970s and have witnessed the MRR’s evolution since then.

Table 2. List of interviewees.

Interview questions focused on the events that shaped the MRR as a tourist destination in order to identify triggering events following Sydow’s (Citation2012) methodology (see also Sydow et al., Citation2018), and on the recent interrelations between the wine and tourism industries in the destination. All interviews were transcribed and coded in NVivo, using pre-established codes: triggering events, historical events, tourism drivers, and tourism challenges. The last two codes provided insights into the strong relationships between the wine and tourism industries.

From caves to wine: triggering wine-tourism in the Margaret River region

Tourism emerged in the MRR in the late 19th century and from the very beginning it developed an interaction with the timber industry that had been established previously (Sanders, Citation1999). Decades later, during the post-WWI and post-WWII periods, tourism interacted with the dairy industry. When the latter was declining in the 1960s, the wine industry emerged and soon began to interact with tourism giving rise to the popular wine-tourism destination which the MRR is today. This section is divided into three subsections, each of which addresses the interactions between tourism and one of the other industries separately in chronological order.

Tourism and timber (late 19th century–1910s)

According to Sanders (Citation2006), between the end of the 19th Century and the early 20th century tourism in the MRR was rather insignificant as it relied mostly on ‘visiting friends and relatives’ (VFR). The situation started changing with the discovery of caves under the surrounding forests (Rundle, Citation1996; Sanders, Citation1999). The caves received attention from locals and soon became an important tourism driver. For instance, as Battye (Citation1912, p. 5) described it, ‘those marvellous jewel houses, the southwest caves, are our [WA’s] glory and pride’. While caves played a central role in the MRR, the natural landscape, including tall native forests, beaches, and wildlife, also contributed to tourism development in the region, as acknowledged by several local newspapers of that time (see e.g. Truth, Citation1916). As interviewee 11 mentioned:

[The caves] were the starting point of the tourism in the region, and it is still part of the tourism attractions today. [They] have lost their leading role they had more than one hundred years ago (…) they are not that crucial anymore.

(Interview, February 2021)

In this period, tourism emerged in the context of settler colonialism where timber was a dominant industry. During the development of the timber industry interpath relations between timber and tourism evolved from neutral to competitive—a rather expected pattern according to Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020). Clearly, timber and tourism had different markets and could appear unrelated at first sight. However, as demonstrated by mining and tourism in Sweden (Stihl, Citation2022), interpath relations between tourism and extractive industries are not impossible. In this particular period, tourism in the MRR directly benefited from the assets (roads and routines) created by the timber industry that remained unaffected by tourism for a few decades. This relationship fell into the ‘no reformation’ category from Breul et al. (Citation2021) framework. However, as caves became an iconic element of the MRR and, importantly, of WA, they had to be protected by the government from the continuous growth of the timber industry and the extraction of surrounding forests through conservation policies. This led to competition for the same resource (forests) that over time became scarce or endangered. However, distributed agency among non-firm actors (e.g. WA government) neutralised and mitigated this competition, thus preventing a negative path-development of either tourism or timber. While the conservation policies did not attempt to affect the timber industry, it is possible to infer that the establishment of cave reserves eventually contributed to its dissolution in the MRR. This situation is similar to the Zambezi region (Namibia) where zoning policies in the late 1990s led to competitive interpath relations between agriculture and tourism affecting the development of the former (Breul et al., Citation2021). Importantly, it is possible to add to Breul et al.’s framework (2021) that emerging industries which do not share markets with established ones, but rely on the same scarce assets, can foster a negative path-development of the preexisting industry.

Tourism, dairy, and wine (1920s–1960s)

Despite the dissolution of the timber industry, tourism steadily continued to develop based on the increasing popularity of caves and forests. For instance, public-led accommodation, transport networks, and later also reservation systems were developed to bring visitors to the MRR, mainly from Perth (The West Australian, Citation1934). The region also soon became a favourite destination for honeymooners (Sanders, Citation1999). Nonetheless, tourism was affected by subsequent global events such as the Great War (WWI) and WWII (Sanders, Citation2006). In order to promote economic recovery in the region after both wars, the WA government carried out two important attempts to establish the dairy industry on the relatively cleared land left behind by the timber industry (Jones et al., Citation2015; Sanders, Citation2006). The first one (Group Settlement Scheme) took place between 1921 and 1930 and it brought many British families to establish dairy farming and agriculture. This scheme failed due to a lack of funding, resources, and experience amongst the farmers (Jones & Jones, Citation2020; Sanders, Citation2006). The second scheme, known as the War Service Land Settlement (1945–1960), aimed to provide cleared land to returned WWII soldiers to help them establish dairy farming. While this scheme suffered from similar problems as the previous one, it was also severely influenced by the increasing cost of labour and land related to the post-WWII economic boom. As a result, the dairy industry started gradually relocating to different regions, leaving behind hectares of affordable land and a sealed road network established through government support (Barrett, Citation1965; Sanders, Citation2006).

The available land, improved accessibility, and a period of economic growth facilitated the arrival of new people and industries to the region. For instance, visitors, mainly affluent people of the post-war youth culture, would drive from Perth for short stays or camping and ‘discover’ the region’s surfing potential (McDonald-Lee, Citation2016). In the next two decades, those surfers as well as members of the countercultural movement (hippies) moved to permanent places near surf beaches, taking advantage of the affordable old properties left behind by the post-war settlements related to dairy (Jones et al., Citation2019; Nicholls, Citation1966; Sanders, Citation2006). There was a noticeable difference between new residents and the remaining dairy farmers in the region. Interviewee 40 commented:

[S]urfers started coming to Margaret River intensively in the 70s. People (…) were surfing there in the 60s and 70s (…) Historically, there was a bit of a clash of cultures between the surfers who tended to be a little bit alternative in their approach to the lifestyle on one hand, and then the existing dairy farmers on the other who (…) have been there for a long time (…). And then there was the orange movement, which was sort of associated with free love and that sort of things and that upset quite a lot of the locals and the more conventional moralities.

(Interview, April 2021)

Initially, the interpath relation between dairy and tourism was neutral as they neither competed for assets or markets, nor actively supported each other. However, the relation between these two sectors was passively supportive. While in a different context the two industries might compete for the same scarce assets, which might result in a negative path-development of one of those industries (see Breul et al., Citation2021), the path-dissolution of the dairy industry turned a scarce asset (i.e. cleared land) into an abundant one that was subsequently taken advantage of by both the developing tourism industry and a completely new sector in the MRR—the wine industry.

The wine industry is one of the most important industries that emerged in this period after the dissolution of the dairy industry. Its development resulted from four contingent events: an increasing national demand for European-style wine; decreasing productivity of vineyards in the Swan Valley in Perth (WA); wine-related lobby groups; and the recommendations made by Dr Olmo (a visiting viticulturalist with the WA Vine Fruits Research Trust) (Forrestal & Jordan, Citation2017), although the latter did not include the MRR as a potential wine region due to its rainfall patterns. However, in 1966 Dr Gladstone, a WA government agronomist, produced a report describing the potential of the MRR based on the local knowledge he had due to his frequent trips to the region (Forrestal & Jordan, Citation2017). Following the report, he was invited by local farmers who were looking to diversify as dairy farming had already started declining (Forrestal & Jordan, Citation2017; Sanders, Citation2006; Thompson, Citation2015). Following Gladstone’s visit, the first vines were planted in 1967 and a new path in the region began. As described by respondent 15:

I started coming down here in the 60s, and I remember seeing Cullen Wines on caves road, but not many others (…) There were still paddocks with cows and everything. It [MRR] was a farming community. But then, all of a sudden, all the paddocks were being sold, cows were gone and vineyards everywhere.

(Interview, March 2021)

Tourism and wine (1970s–2010s)

From the very beginning, the wine industry in the MRR exhibited a strong quest for quality, which helped position local wineries among the best-ranked in Australia (Hanley, Citation1982). Although at the initial stage the wine industry found itself competing with tourism for governmental support and a primary role in the MRR’s development (Interviewee 9), the potential for growth that both sectors identified in mutual collaboration, helped minimise the number of tensions and proved to be a promising platform for joint future initiatives. Indeed, vineyards were much more complementary to the tourism sector than dairy farms had been before and some early positive interactions between both industries gradually started to emerge. From 1978 wineries began to open tourist facilities such as galleries, restaurants, and cellar-door under winemakers initiative (Brearley, Citation2022). However, the most important step towards the consolidation of wine-tourism took place in 1985 when the Leeuwin Estate brought the London Philharmonic Orchestra to the region (Hoad, Citation1984). Since that event played a major role in showcasing the region’s natural beauty, it is deemed to have gained the MRR international recognition and popularity. As Interviewee 38 indicated:

[I] believe that the icon event that still goes today is the Leeuwin Estate Winery concert (…) Up until that time [1980s], Margaret River was very well known domestically, but not so much internationally (…) The Leeuwin Estate concert, the first one (…) was a major international iconic event (…) the blending of what was probably the region’s first international event (…) in a fantastic backdrop with the wineries and the forest and those sorts of things (…) There’s obviously a few things that shaped the industry down there. That (…) concert was one of those.

(Interview, February 2021)

Over the 1980s, various combined wine-tourism ventures multiplied. While many vineyards directly diversified into tourism by opening chalets and restaurants on their premises, the linkages between the two industries were further strengthened by local wine tasting events, and organised coach tours to cellar doors (Dear, Citation1988; Vasse Felix, Citation2020). The development and diversification of wine and tourism in the region were further encouraged in the 1990s by the increasing internationalisation of both sectors (Canberra Times, Citation1994; Foster, Citation1990; Macklin, Citation1991). Various foreign investments in tourist resorts and wine companies (Petkanas et al., Citation1997), accompanied by an arrival of gourmet firms related to wine (Carthew, Citation1999; Foster, Citation1992), translated into even stronger linkages between wine and tourism. As a result, wine-tourism earned recognition as a unique entity capable of promoting and shaping the development of the region even more efficiently than the preceding forms of tourism (Ozich, Citation1998). Such growth led to a ‘tourism boom’ in the region, turning wine-tourism into one of the region’s economic drivers from 2000 onwards (Zekulich, Citation2004). As Interviewee 13 described it:

[Wine and tourism] have a pretty strong relationship. I think the wine industry in the MRR has brought a lot to the region (…) If you look at the local shire maybe 50 years ago, [the MRR] was one of the lowest socioeconomic shires in Australia. The wine industry has brought a lot of investment and a lot of prosperity to the region (…) It kind of put MRR on the map. (…) It has created jobs and opportunities.

(Interview, April 2021)

As such, tourism and wine have an evolving interaction. They initially targeted different markets and competed for the same scarce assets (e.g. public funding, legitimisation) that could have resulted in a negative path-development of one of them. Fortunately, the agency in both industries was oriented towards creating supportive relations. While the important role of various minor developments (cellar doors, galleries) should not be overlooked, the concert organised by a wine entrepreneur was the main event triggering massive changes in the region and encouraging a closer collaboration between tourism and wine. Although the original intention was to promote the wine market, the event brought both industries together, promoting the emergence of a complementary market for tourism and the wine industry (in particular cellar doors and restaurants in wineries). As such, this selective triggering event (see Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017) contributed to the emergence of wine-tourism which resulted in simultaneous path-expansion of the existing tourism sector and the still incipient wine industry. In this respect, Breul et al. (Citation2021) framework can be expanded by a scenario in which an interpath relation is influenced not only by an established industry but also by an emerging one. Indeed, since the tourism boom, wine-tourism has begun to evolve as a single path, although still largely dependent on both tourism and wine. As such, this paper suggests that wine-tourism is a new path in the MRR that resulted from the progressive blending of key components of the tourism and wine industries (infrastructure, actors, and related industries). This paper refers to this process as path-blending. summarises the various interpath relations of tourism with other regional industries.

Conclusions

The paper adopted the EEG concept of interpath relations (as well as its various sister concepts) to analyse the evolution of the Margaret River region as a tourist destination. Drawing from the frameworks proposed by Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) and Breul et al. (Citation2021) the paper offered empirical and theoretical developments that extend the applicability of EEG approaches to tourism evolution and the relations between tourism and other industries.

The paper related three relevant findings about the evolution of the MRR. First, by means of applying Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) framework, it evidenced the variegated interpath relations in the MRR between tourism and timber, tourism and dairy, and tourism and the wine industry. Those relationships have varied from competing to neutral and to supportive. Second, the paper reaffirmed the usefulness of distributed agency (see Boschma, Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2018) and interpath relations in identifying the agency of actors engaged in other, seemingly unrelated, industries as well as non-firm actors. For instance, the path-renewal of tourism was partially influenced by the relocation of the dairy industry. Third, since the paper covered the evolution of tourism in the MRR for almost 150 years, it helps recognise the long-term effects of interpath relations. For instance, the paper suggested that the competing interpath relation between timber and tourism led to the creation of conservation reserves that proved pivotal for the destination and began a pathway where extractive industries are spatially excluded from natural attractions. Consequently, this paper demonstrated that policy interventions in regional extractive industries influenced the development of tourism in the MRR.

The paper contributes to the existing theory of triggering events and interpath relations. Regarding the former, the paper showed that triggering events require an enabling context to influence a given path. Furthermore, based on the analysis above, it is possible to argue that triggering events might be dependent on previous triggering events and even take place in a logical sequence, as opposed to random chance events. Interpath relations as a framework allowed the research to go beyond the single-path view and identify the interrelations between various triggering events (i.e. the Leeuwin concert and subsequent high-profile musical events at wineries would not have been organised without the publishing of Dr Gladstone’s report a few years before). In terms of interpath relations, this paper adds path-dissolution to the range of scenarios anticipated by both sectors. As noted, the path-dissolution of the dairy industry left behind various assets that were subsequently acquired by the emerging wine industry. Finally, this paper suggests the possibility of a new form of path-development: path-blending. The continuously evolving interpath relations between tourism and wine resulted in wine-tourism as a new, integrated and consolidated regional path with a distinctive market, defined assets and actors, and a distinctive growth trajectory. As such, path-blending opens the debate on tourism evolution and the tendency of tourism to develop linkages with other industries (for instance tea-tourism, whisky-tourism, agri-tourism). Further research into path-blending will offer greater insights into how interpath relations shape destinations and the regional characteristics of tourism activities. For instance, the above analysis of tourism and wine path-blending indicates that future policies should consider the interpath relations between both industries. From this perspective, cross-sector mechanisms such as the recent eco-destination accreditation (see Shire of AMR, Citation2022) are appropriate as they incorporate sustainability principles into both the tourism and the emerging wine-tourism sectors.

Acknowledgments

To the Aberdeen – Curtin alliance, the interviewees, Dr Roy Jones, and Dr Petra Dumbell.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Flood Chavez

David Flood Chavez is a PhD candidate in human geography at the department of Geography and Environment at the University of Aberdeen, UK. His research is with the collaboration of Curtin University in Western Australia and is funded by the Aberdeen – Curtin Alliance. His work mainly focuses on sustainability transitions and evolutionary approaches on the evolution of tourist destinations as well as political ecology approaches on tourism in the Global South.

Piotr Niewiadomski

Dr Piotr Niewiadomski is an economic geographer interested in the worldwide development of the tourism production system, the global production networks of tourist firms, the impact of tourism on economic development in host destinations, and the emerging sustainability transition research on tourism development. His research mainly focuses on Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the context of post-communist restructuring in CEE after 1989. He is now Senior Lecturer in Human Geography in the School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, UK.

Tod Jones

Dr Tod Jones is a human geographer interested in cultural and political geographies in Australia and Indonesia, in particular bringing contemporary geography approaches to cultural economy and heritage issues. His current projects are on Indigenous heritage and urban planning, social movements and heritage, sustainable tourism, and applying a sustainable livelihoods approach to assess heritage initiatives. He is now an Associate Professor in Geography in the School of Design and Built Environment at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia.

References

- ABS. (2016). 2016 Census QuickStats: Augusta – Margaret River – Busselton. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/50101?opendocument

- Augusta - Margaret River Mail. (2013). 100 years of Margaret River: Timeline. Augusta - Margaret River Mail.

- Augusta - Margaret River Mail. (2018). Margaret River Wine Show. Augusta - Margaret River Mail.

- Baggio, R., & Sainaghi, R. (2011). Complex and chaotic tourism systems: Towards a quantitative approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 23(6), 840–861. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111111153501

- Barrett, A. R. (1965). History of the War Service Land Settlement Scheme. Western Australia. A.B. Davies, Govt. printer

- Battye, J. S. (1912). The Cyclopedia of Western Australia : An historical and commercial review, descriptive and biographical facts figures and illustrations : An epitome of progress. Cyclopedia Company by Hussey & Gillingham.

- Benner, M. (2022). Revisiting path-as-process: Agency in a discontinuity-development model. European Planning Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2061309

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R. A., & Frenken, K. (2006). Why is economic geography not an evolutionary science? Towards an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(3), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Bramwell, B., & Cox, V. (2009). Stage and path dependence approaches to the evolution of a national park tourism partnership. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802495782

- Brearley, M. (2022). Our Story . Gralyn Estate. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://gralyn.com.au/pages/our-story

- Breul, M., Hulke, C., & Kalvelage, L. (2021). Path formation and reformation: Studying the variegated consequences of path creation for regional development. Economic Geography, 97(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1922277

- Brouder, P. (2014a). Evolutionary economic geography: A new path for tourism studies? Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864323

- Brouder, P. (2014b). Evolutionary economic geography and tourism studies: Extant studies and future research directions. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 540–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.947314

- Brouder, P., Clavé, S. A., Gill, A., & Ioannides, D. (2016). Why is tourism not an evolutionary science? Understanding the past, present and future of destination evolution. In Brouder, P., Clavé, S.A., Gill, A., & Ioannides, D. (Eds.), Tourism Destination Evolution (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013a). Tourism evolution: On the synergies of tourism studies and evolutionary economic geography. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.001

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013b). Staying power: What influences micro-firm survival in tourism? Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.647326

- Butler, R. (2014). Coastal tourist resorts: History, development and models. Centros Turísticos Costeros: Historia, Desarrollo y Modelos, 9, 203–228. https://doi.org/10.5821/ace.9.25.3626

- Butler, R. w. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 24(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

- Canberra Times. (1994). Advertising. Canberra Times (ACT : 1926–1995).

- Carthew, N. (1999). Marron farm combines with tourism venture. Countryman.

- Caves Board. (1910). Ledger.

- David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. The American Economic Review, 75, 332–337.

- Dear, A. (1988). Advertisement. The Australian Financial Review.

- Forrestal, P., & Jordan, R. (2017). The way it was: A history of the early days of the Margaret River wine industry. ReadHowYouWant.com, Limited.

- Foster, M. (1990). Margaret River wines arrive to pamper. Canberra Times.

- Foster, M. (1992). Connoiseurs compliment local products - FOOD AND WINE. The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995) 14.

- Frangenheim, A. (2022). Regional preconditions to shape interpath relations across regions: Two cases from the Austrian food sector. European Planning Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2053661

- Frangenheim, A., Trippl, M., & Chlebna, C. (2020). Beyond the single path view: Interpath dynamics in regional contexts. Economic Geography, 96(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120296

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2001). Path creation as a process of mindful deviation. In R. Garud & P. Karnøe (Eds.), Path dependence and creation (pp. 1–38). Psychology Press.

- Gazette, P. (1848). Local Intelligence. Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News.

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2014). Mindful deviation in creating a governance path towards sustainability in resort destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925964

- Gill, A., & Williams, P. W. (2017). Contested pathways towards tourism-destination sustainability in Whistler, British Columbia: An evolutionary governance model. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism Destination Evolution (pp. 43–64). Routledge.

- Halkier, H., & James, L. (2017). Destination dynamics, path dependency and resilience: Regaining momentum in Danish coastal tourism destinations?. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 19–42). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315550749

- Hanley, J. (1982). Keeping their cool justifies the optimism. The Bulletin, 102, 88.

- Hassink, R. (2010). Locked in decline? On the role of regional lock-ins in old industrial areas. In R. A. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 450–468). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hoad, B. (1984). An unusual millionaire saves an orchestral tour. The Bulletin, 106, 97–98.

- Jones, R., Burke, G., & Stocker, L. (2019). Climate change, tourism and rural sustainability in the Margaret River wine region of Western Australia. In T. O’Rourke & M. Koščak (Eds.), Ethical and responsible tourism: Managing sustainability in local tourism destinations (pp. 265–273). Routledge.

- Jones, R., Diniz, A. M. A., Selwood, J., Brayshay, M., & Lacerda, E. (2015). Rural settlement schemes in the South West of Western Australia and Roraima State, Brazil: unsustainable rural systems? Carpathian Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 10, 125–132.

- Jones, R., & Jones, T. (2020). Antipodean aftershocks: Group settlement of Hebridean and non-Hebridean Britons in Western Australia following world war one. Northern Scotland, 11(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.3366/nor.2020.0221

- Jones, R., Wardell-Johnson, A., Gibberd, M., Pilgrim, A., Wardell-Johnson, G., Galbreath, J., Bizjak, S., Ward, D., Benjamin, K., & Carlsen, J. (2010). The impact of climate change on the Margaret River wine region: Developing adaptation and response strategies for the tourism industry. CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd.

- L’equipe MIT (Ed.). (2002). Tourismes 1. Lieux communs, Tourismes.

- Laws, E., & Prideaux, B. (2006). Crisis management: A suggested typology. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 19(2-3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v19n02_01

- Ma, M., & Hassink, R. (2013). An evolutionary perspective on tourism area development. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 89–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.004

- Ma, M., & Hassink, R. (2014). Path dependence and tourism area development: The case of Guilin, China. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 580–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925966

- Martin, R. (2009). Roepke lecture in economic geography—Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2012). The place of path dependence in an evolutionary perpsective on the economic landscape. In R. Boschma & R. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 62–92). Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

- Macklin, R. (1991). What occasion would warrant a ‘52 Grange? Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995) 24.

- McDonald-Lee, T. (2016). Three generations of surfing nomads. Horizons, June/July, 28–32.

- MRBTA. (2019). Margaret River Busselton Tourism Association Annual Report 2018–2019.

- MRWIA. (2020). Margaret River wine region overview. Western Australia.

- Murray, J. (2020). Marriott to operate new Margaret River spa and resort. Business News.

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Nicholls, P. C. (1966). Caves in the corner. Walkabout, 32, 39.

- Northam Advertiser. (1900). The Margaret River caves. Northam Advertiser.

- Ozich, V. (1998). Experts urge care in wine tourism growth. Countryman.

- Petkanas, C., Rapp, M., & Baldwin, I. (1997). The river Down Under. Travel & Leisure.

- Ritchie, B. W., Crotts, J. C., Zehrer, A., & Volsky, G. T. (2014). Understanding the effects of a tourism crisis: The impact of the BP oil spill on regional lodging demand. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513482775

- Rundle, G. E. (1996). History of conservation reserves in the south-west of Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 79, 225–240.

- Saarinen, J. (2004). Destinations in change’: The transformation process of tourist destinations. Tourist Studies, 4(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797604054381

- Sanders, D. (1999). Tourism and recreation in the forests of south-western Australia. In J. Dargavel & B. Libbis, (Eds.), Australia’s Ever-Changing Forests, Conference Proceedings of the National Conferences on Australian Forest History. Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University in association with Australian Forest History Society inc., Canberra.

- Sanders, D. (2006). From colonial outpost to popular tourism destination: An historical geography of the Leeuwin-Naturaliste Region 1829-2005. [PhD]. Murdoch University.

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C., & Anton Clavé, S. (2014). The evolution of destinations: Towards an evolutionary and relational economic geography approach. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925965

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C., Wilson, J., & Anton Clavé, S. (2017). Moments as catalysts for change in the evolutionary paths of tourism destinations. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 80–102). Routledge.

- Schienstock, G. (2007). From path dependency to path creation: Finland on its way to the knowledge-based economy. Current Sociology, 55(1), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392107070136

- Shire of AMR. (2022). Eco destination. Retrieved May 4, 2022, from https://www.amrshire.wa.gov.au/sustainability/eco-destination

- Stihl, L. (2022). Challenging the set mining path: Agency and diversification in the case of Kiruna. The Extractive Industries and Society, 101064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101064

- Sydow, J., Windeler, A., Müller-Seitz, G., & Lange, K. (2012). Path constitution analysis: A methodology for understanding path dependence and path creation. Business Research, 5(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03342736

- Sydow, J., Windeler, A., Müller-Seitz, G., & Lange, K. (2018). Path constitution analysis: A methodology for understanding path dependence and path creation. In A. Bryman & D. A. Buchanan (Eds.), Unconventional methodology in organization and management research (pp. 255–276). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198796978.003.0013

- The West Australian. (1934). Holiday Resorts. Western Australia.

- Thompson, M. (2015). Tourism in agricultural regions in Australia: Developing experiences from agricultural resources. [PhD]. James Cook University.

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Truth. (1916). Westralia’s Wonderland. Truth.

- Valentine, G. (2005). Tell me about…: using interviews as a research methodology. In R. Flowerdew & D. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography: A guide for students doing a research project. Routledge.

- Vasse Felix. (2020). Vasse Felix | About Us | Our History. Retrieved April 7, 2022, from https://www.vassefelix.com.au/About-Us/Our-History

- Wellington, A. (2003). Hideaways for hedonists. The West Australian.

- Yang, X., Zha, Y., Lu, L., & Yang, Y. (2017). An evolutionary economic geography perspective on types of operation development in West Lake, China. Chinese Geographical Science, 27(3), 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-017-0855-0

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods: (Applied Social Research Methods, Volume 5) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Zekulich, M. (2004). Tourism boom in wine areas. The West Australian.