Abstract

This article examines social disadvantage in tourist sites through the lens of labour geography by focusing on the residential trajectories of a sample of workers in Barcelona (N = 8,651) over a decade (2008–2019). Contrasting with the common view that tourism growth brings prosperity to local communities, it suggests instead that buoyant destinations may be prone to leaving their workforces behind. Path analysis modelling reveals that tourism sector workers are at a higher risk of residential displacement. Our analysis unearths stratifications in such results, pointing to different tactics to cope with housing market pressure depending on sex, age, and nationality. Residential displacement and the self-imposed devaluation of housing conditions are introduced in this paper as key avenues leading to social exclusion. In this sense, we contribute to the concern of critical tourism geographies with the inequality and disadvantage ingrained in tourist space production, bridging to the domain of labour geography and social mobility. The city of Barcelona offers a template for other urban contexts that have been reliant on tourism as a major driver of economic growth in recent decades. Following the call for closer attention to labour in the debate on transitions to sustainability in tourism, our results hint at future research avenues that extend their interpretation.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the relation between precarious labour and precarious housing, contributing new evidence on one of the emerging wicked problems in tourism development and more broadly in urban studies: the capacity of workers to afford to live close to their place of employment. We therefore address a key issue in the field of tourism geographies, that of the production of social inequalities through a critical analysis of the social production of tourist space and its evolution. The bulk of our empirical work is based on panel data tracking the residential trajectories of 8,651 workers who lived in the municipality of Barcelona between 2008 and 2013. The specific objective was to explore whether residential changes in the subsequent six years (2013–2019) could have been motivated by the precarious nature of the jobs held by workers employed in tourism-related occupations, as opposed to a residual group of workers in other sectors. Our findings reveal that low wages, temporality, and the discontinuity of work are associated with a greater likelihood of moving to a new residence outside Barcelona, and that all these indicators mediate the relationship between being employed in tourism and leaving the city. The model outputs also point to significant differences in these results according to sex, age, and nationality, hinting at the different material and cultural forms of coping with housing unaffordability that can be scripted in the workers’ biographies and life-courses.

As such, this piece of research challenges one of the main assumptions in tourism development, that is, its actual capacity to contribute to the diffused prosperity of destination communities. While the regional economics literature suggests that, at a macro-level, tourism development does work in the sense of providing greater territorial cohesion (Llorca-Rodríguez et al., Citation2021), the local effects in terms of social inclusion and redistribution are more ambiguous. The geographies of disadvantage and social conflict triggered by tourism growth have been scrutinized by a myriad of authors (for a comprehensive review of epistemological approaches and topics of concern, see respectively; Mura & Wijesinghe, Citation2021; Novy & Colomb, Citation2019), suggesting that, at least in mature destinations, tourism struggles to be an effective growth strategy.

In this regard, a focus on Barcelona is pertinent for different reasons. The Catalan capital is a celebrated example of urban regeneration with a specific focus on culture, events, and the design of public space. This transformation, for which the ‘Olympic’ reforms at the turn of the 1980s have been a key catalyst (Marshall, Citation2004), has favoured Barcelona’s transition to a post-industrial economy and a thriving tourist destination. However, this success story is not free from contradictions. Critical readings hint at the neoliberal turn in urban policy and governance that has allegedly taken over the regeneration agenda (Arbaci & Tapada-Berteli, Citation2012). In this light, it could be argued that the accelerated conversion of Barcelona into a global tourist hub has determined a reorientation of its urban economy towards the material and economic capacities of international tourists and other privileged temporary populations at the expense of its residents (Novy & Colomb, Citation2019). In a framework of intensified negotiation for urban space and commons (a landscape that has come to be called ‘overtourism’), certain pathways of social exclusion have gained ground (Goodwin, Citation2019). Among these, are the mounting precarisation of increasing numbers of workers in tourism services and the growing unaffordability of the housing market, which in this paper we analyse in synchrony. In a city that is highly dependent on tourism labour (it represents 8.6 percent of the city’s employment), and where the supply of social housing is historically poor (Barnett et al., Citation2020), residential displacement under the pressure of the visitor economy has become a matter of concern in both social and political debates (Russo & Scarnato, Citation2018). In this regard, Barcelona’s storyline is not substantially different from that of other cities which have relied on tourism growth to accompany their post-industrial transition or even their economic recovery after the global financial slump of 2007 (Clancy, Citation2022; Tulumello & Allegretti, Citation2021).

Theoretical framework

Precarious work and precarious housing

As reported by Bobek et al. (Citation2021, p. 2), ‘housing pathways are often explored in the context of choice, linking individuals’ housing mobility to different stages of their life cycle’. Indeed, there is consistent evidence in the literature of the influence of life courses on residential choice. Family formation and parenthood, educational mobility, occupational opportunities, and retirement are all factors that have been found to contribute to housing transitions (Herbers et al., Citation2014). However, when the choice is delayed by a protracted state of precarious employment, the so-called ‘housing career’ (i.e. leaving the parental home, renting accommodation, and finally home ownership) is interrupted (Clark et al., Citation2003). One of the most tangible results is that young people tend to leave parental homes later: in Spain, for instance, the average age for leaving home was around 30 in 2020, three years later than the European average (Eurostat, Citation2021).

Despite its pervasiveness in present-day working lives, defining ‘precarity’ is quite challenging. A baseline definition would refer to non-standard or atypical employment relations (Bobek et al., Citation2018), as opposed to fixed-term and stable contracts. Scholars have highlighted three constitutive components of precarious work: the limited duration of employment relations (temporal and short-time contracts), the vulnerability of workers’ rights (low negotiating power in the labour market), and low wages (Barbier, Citation2011), all of which have been noted to be on the rise in Western Europe since the progressive liberalisation of labour regulations in the 1980s (Rodgers, Citation1989). At the same time, precarity pervades multiple spheres of life beyond labour conditions, which is why Campbell and Price (Citation2016) argued in favour of an enhanced conceptualization to differentiate between: precariousness in employment, roughly aligned with the three components mentioned above; precarious work, as a measure of the (poor) quality of jobs; and precarious workers, who are not just employed in precarious occupations, but also suffer from the negative consequences of protracted precarity on health and inter-personal relationships (Julià et al., Citation2017).

As for the specific consequences of long-term precarity on residential choices, the previous literature points to a ‘double precarity marked by insecure employment and insecure housing’ (Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016, p. 47). Low incomes, coupled with increasing rents, often imply that precarious workers spend larger shares of their salaries to cover housing costs. As reported by Clair et al. (Citation2016), this has especially been the case since the recession in 2007, with 3.5 million people in Europe being in arrears on their housing payments between 2008 and 2010. The widening gap between housing costs and salaries has led to widespread housing insecurity (Borg, Citation2015). Overall, a review of the literature suggests two possible outcomes of precarious work on housing: unwanted displacement, due to the unaffordability of housing costs, or even as a consequence of an eviction (Desmond, Citation2015); and residential immobility as a condition of enduring disadvantage associated with housing facilities of poor quality and the impossibility of moving somewhere better (Salazar, Citation2020). However, residential immobility can also emerge as a strategy to counterbalance precarity in employment, as it favours the creation of networks of information and support. In this regard, immobility, just like mobility, is not necessarily a passive state but rather an active process through which precarious workers adapt to changing labour market conditions (Preece, 2017). Along the same lines, Zampoukos (Citation2018) uses a relational approach to examine personal life-course trajectories, contesting the linear character of labour mobility, and bringing to the fore instead the (constrained) agency of workers in specific social and spatial contexts, their highly intersectional nature, and their enmeshment with other forms of immobility, such as migration or being ‘stuck in place’.

Precarity in tourism work

Before COVID-19, the travel and tourism sector contributed 10.4 percent to the global GDP and provided 330 million jobs (World Travel & Tourism Council, Citation2019). In Spain, the weight of this sector in national GDP was even higher (14.4 percent), with 2.8 million jobs (14.4 percent of total employment) in 2019. Nonetheless, job quality in the tourism sector is often called into question because of its inherently temporary and irregular nature (Walmsley et al., Citation2021). Outsourcing, as a standard practice of the flexibilization of contractual relationships in tourism and hospitality, is also considered a significant driver of precarity, falling out of the scope of traditional unionised representation (Jordhus-Lier, Citation2014). The greater risk of precarity of women in tourism-related employment is discussed by Bolton (Citation2009) and Wolkowitz (Citation2006), while a more intersectional approach, focusing on migrants’ higher exposure to poor working conditions, is provided by Cañada (Citation2018) and Nuti (Citation2018).

Despite rising concerns about precarity in tourism work, Baum et al. (Citation2016) have warned about the lack of critical examinations of tourism employment in current debates on sustainable tourism. Likewise, according to Bianchi (Citation2009), any reference to sustainability in tourism employment is awkward, as it fits into the framework of ‘an aggressive economic liberalism’ (p. 493), while Robinson et al. (2018) argue that tourism work is unsustainable by definition, as it reproduces and deepens social inequalities. It is also suggested that such inequalities have a marked spatial dimension, as the production of tourist space involves the voluntary or exclusionary displacement of resident populations, or else a self-imposed degradation of housing conditions to cope with the rising price of rents (Cocola-Gant, Citation2019). Considering that a substantial share of such incumbent populations, especially in historical city centres, are directly or indirectly employed in tourism, a distinct geography of social disadvantage emerges, stemming from the disadvantaged position of precarious workers in the face of the dynamics of place imposed by the visitor economy.

As for Barcelona, a review of the literature shows that precarious work predominates in Barcelona’s tourism and hospitality sector (Bolíbar et al., Citation2020), intersecting with widening gender inequalities (Martínez-Gayo & Martínez-Quintana, Citation2020). According to Cañada (Citation2017), one possible explanation for the poor working conditions in this sector is that cities like the Catalan capital attract remarkable contingents of migrant workers from developing economies, who are prepared to accept any job in the formal or informal labour markets. This, in turn, may be exacerbating the deterioration of employment conditions for all workers, at least in the short term (Dustmann et al., Citation2017). Yet, research on the impact of labour precarity on the residential trajectories of tourism workers, and thus on the resulting avenues of social exclusion that are ingrained in the geography of tourist destinations, is a much less trodden path. Prior analyses have revealed a significant relationship between tourism pressure and housing unaffordability (Biagi et al., Citation2012; García-López et al., 2020), whereas precarious housing conditions enmeshed in occupational seasonality and the related regulations have been explored by Terry (Citation2017).

Data and methods

Data source and sample

This study is based on data from the Continuous Sample of Working Lives, hereinafter referred to as CSWL (Ministerio de Inclusión & Seguridad Social y Migraciones, Citation2020), a random sample of all individuals who had some connection (contribution or pension) with the social security system at any time in the year of reference. We accessed data from three different editions (2008, 2013, and 2019) in order to implement a longitudinal (panel) analysis. Our analysis focuses on a subset of workers selected in accordance with two criteria:

Their workplaces were in the municipality of Barcelona in 2019, without implying that they could have not complemented this job with others in a different location. Descriptive statistics indicate that, on average, 91.7 percent of the total days worked by workers in our sample for this reference year were in Barcelona.

The place of residence was Barcelona in both 2008 and 2013, giving them the status of long-term residents.

In line with these specifications, the sample (N = 8,651) was best suited for a study of patterns of residential displacement between 2013 and 2019, with a focus on long-term residents who were still working in Barcelona in the last year of our longitudinal series. In light of these two sampling criteria, moving out of the city will most likely imply an increase in the time spent commuting to work, thus adding an additional layer of complexity to labour routines.

Hypothesis and main outcome variable in the proposed model

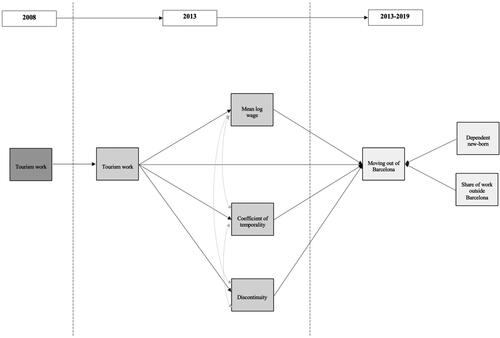

The longitudinal model is presented in . The main hypothesis is that working in tourism-related occupations is associated with low salaries and temporary and discontinuous jobs, which in turn might entail negative effects on other life domains, for example, residential stability. Due to the precarious nature of their jobs, we anticipated that tourism workers might be more exposed to the need to move out of Barcelona than other workers, as their labour conditions are incompatible with the cost of living in the city. This assumption is supported by official figures (Ruiz-Almar et al., Citation2022) revealing that, in 2019, the average cost of buying a newly constructed house in Barcelona was 39.8 percent higher compared to surrounding municipalities. Likewise, there was a 13.8 percent difference between the average monthly rent in Barcelona (979 euros) and the rest of its metropolitan area (844 euros). Therefore, those who moved out of the city would assume, on average, lower housing costs.

The main outcome variable in our model is a dichotomous variable in which a value of 1 is assigned to workers who resided in Barcelona in 2013 but then moved to a different location between 2013 and 2019, as opposed to a value of 0 identifying workers in a different situation (i.e. residents in Barcelona in both years, or moving into Barcelona from another location).

Measures of tourism work and precarity

The pre-processing of the raw dataset allowed us to extract the number of days worked by each employee in the sample, broken down by year of reference and occupational sector. The CSWL classifies occupational sectors according to the Spanish National Classification of Economic Activities (CNAE-09). The operationalization of our variable of tourism work includes a cluster of the occupational sub-sectors listed in . The cumulative number of days worked in tourism-related occupations was calculated, as well as their percentage of the total number of days worked in 2008 and 2013 respectively.

Table 1. Occupational sectors included in our definition of tourism work.

To test the role of labour precarity as a determinant of residential choices, three variables are defined. First, the mean log wage in 2013 refers to the logarithmic function of the total earnings accumulated by employees during this year. Second, the coefficient of temporality is calculated as the number of days in temporary jobs divided by the total number of days worked in 2013. Third, the variable discontinuity is measured as the number of sign-ups in the social security system in 2013. In the Spanish labour market, each new contractual relationship has to be recorded in the social security system. Therefore, the higher the number of sign-ups, the greater the labour discontinuity of the worker within the market. As a result, labour precarity in our model retraces the following three facets: the financial resources available to workers, the degree of temporality of their occupations, and their irregular trajectory in the labour market (Bobek et al., Citation2018).

Control variables

The hypothesized relationship between the share of work in tourism-related sectors and the occurrence of moving out of the city was controlled for the possible influence of having a new-born child and the share of days worked in Barcelona as opposed to other locations. The first variable refers to workers who, in the 2019 edition of the CSWL, have one or more dependent new-born children compared to what was registered in the previous 2013 edition. To an extent, therefore, this is a measure of a change in the household composition that may affect the decision to move to a different place (Coulter et al., Citation2016). As for the share of work outside Barcelona, this is defined as the percentage of days worked in workplaces located beyond the municipal boundary of the city, assuming any increase in this percentage between 2013 and 2019 to be a good reason to move out and live closer to one’s main workplace.

Model specification

A cross-lagged panel model was estimated using the Mplus software, version 8.5. The consistency of our hypothesis was tested within the framework of a multi-group strategy to explore differences according to sex (1 = men; 2 = women), age (1 = young workers aged 23–35, plus a residual group 2 = aged 36+), and nationality (1 = Spanish nationals; 2 = non-nationals). Coefficients were estimated using the diagonal weighted least squares approach (estimator = WLSMV), which is the recommended estimator choice with categorical outcomes. Robustness checks (available upon request) were run with Bayesian estimations to derive robust estimates of standard errors and confidence intervals.

In above, single-headed arrows are a graphical representation of the regression functions between the variables. Given our focus on those workers who were long-term residents in Barcelona in 2013, the possible relationship between being employed in tourism work in 2008 and occupational situations six years later was explored. This was a way to test the association between enduring employment in tourism-related occupations and decisions to move out of Barcelona before 2019. Accordingly, a positive and direct relationship between the share of work in the tourism sector in 2013 and the likelihood of moving out of the city is anticipated. Being employed or not in tourism-related sectors was also assumed to exert an indirect effect on the main outcome variable. To this end, the model encompasses three mediator variables, the mean log wage, the coefficient of temporality, and the discontinuity of employment. These variables allowed us to verify whether the decision to move out depends on these three facets of labour precarity after controlling for a proxy of life events (having a new-born child) or any possible change in the location of the workplace.

Results

Working conditions in tourism-related sectors in Barcelona

A first outline of the competing employment conditions of tourism and non-tourism workers is presented in , along with the results of an independent-samples t-test. To this end, the variable of tourism work was dichotomized to separate those workers who have been employed for a percentage of their time in tourism-related sectors from those who did not. The results of the t-test point to a significantly greater precarity of workers employed in tourism-related sectors.

Table 2. Degree of precarity of tourism vs. non-tourism workers.

The percentage of tourism workers who moved out of the city between 2013–2019 was 9.2 percent, compared to 7.2 percent of the rest of the sample, a statistically significant difference according to the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test at a p-value of .01. They account for 18 percent of those who decided to leave the city, but only 15.4 percent of the total sample. provides a breakdown by the grouping variables of sex, age, and nationality.

Table 3. Description of the main outcome variable – Moving out of Barcelona, 2013–2019.

Model output

Standardized model outputs are included in . In line with the multi-group strategy, results are presented separately by sex, age group, and nationality. As reported in the last three rows of the table, fit indices indicate a satisfactory fit.

Table 4. Model output, STDYX standardization.

A few consistent results emerge. First, the autoregressive function linking the variables of tourism work in 2008 and 2013 is statistically significant at a p-value of .001 in all the models estimated. The interpretation of this finding suggests that, regardless of possible differences in terms of sex, age, or nationality, those who held a job in tourism-related sectors in 2008 also did so six years later. In all cases, without exception, higher shares of work in the tourism sector in 2013 mean lower salaries than the average for the same year. Tourism work is associated with higher values of the coefficient of temporality and with greater discontinuity of employment. The exception is the statistically significant and negative sign in the relationships between tourism work and one of the variables linked to precarity in our model (discontinuity) among non-national workers (β = –.057; p ≤ .01). Despite the need for further investigation, this result might indicate that, for non-nationals, working in the tourism sector represents a way to access the local labour market, and then move on to other sectors that guarantee more stable employment. However, the model corroborates the hypothesis that this entails negative consequences in terms of wages and salaries for non-nationals as well (β = –.093; p ≤ .01).

Overall, earning low salaries in 2013 is associated with greater odds of having to move out of the city during the years that followed (2013–2019). It is only among the youngest cohorts and the non-nationals that the effect of the mean log wage on the dependent variable is not statistically significant, although the sign of the relationship is still negative. The discontinuity at work increases the chances of moving out, but only for females (β = .067; p ≤ .01), adults (β = .036; p ≤ .05), and non-national workers (β = .035; p ≤ .05). In the case of males, younger workers, and non-nationals, discontinuity is correlated negatively with the outcome variable. The relationship is not statistically significant in these cases, but again the hypothesis can be made that under certain circumstances a high volume of sign-ups in the social security system can represent a strategy of ‘survival’ in the labour market, especially for the most vulnerable workers.

The model shows quite clearly that the decision to move out of Barcelona is strongly affected by life events, such as having a baby, but less so by changes in the share of work conducted outside the city. However, for the latter variable, the sign of the relationship is in the expected direction, indicating that, should the workers increase their share of work far from Barcelona, the likelihood of their moving out of the city would increase. Also, its weight within the model is most likely reduced by one of our sampling selection criteria, namely holding a job in Barcelona in 2019.

In 2013 the variable tourism work exerts a significant and direct effect on residential mobility among female workers (β = .071; p ≤ .01) and Spanish national workers (β = .049; p ≤ .05). In both cases, the indirect relationship between having been employed in tourism-related activities in 2008 and moving out is significant. More generally, when the mediator variables are included in the equation, negative outcomes for residential stability increase substantially. A closer look at the indirect paths to the outcome variable, coloured in grey in , reveals that for females, adults, and national workers, low salaries and high levels of discontinuity in work significantly mediate the relationship between the variables tourism work in 2013 and moving out of Barcelona between 2013 and 2019. This suggests that, if working in tourism-related sectors is associated with lower salaries and greater discontinuity of employment, which is often the case according to the model output, then the possibility of having to move out of the city rises significantly. On the other hand, the role of the coefficient of temporality within the model has proved to be not so relevant after all.

Discussion

Our findings show that working in tourism-related occupations in Barcelona is correlated with greater odds of being exposed to precarity, defined as a combination of low wages, high temporality, and labour discontinuity. In line with Robinson et al. (2018), employment in tourism was found to be associated with a prolonged situation of disadvantage. Those workers in our sample who were employed in this sector in 2008 continued to be employed five years later, with the same poor working conditions. This may suggest that aspirations for upwards social mobility in the context of a diverse economy such as that of Barcelona could be structurally stifled when residential precarity is brought into the picture. The combination of low wages and being employed in tourism emerges as a consistent predictor of decisions to move out, possibly due to the rising gap between salaries and housing costs, and with a corresponding loss of purchasing power in the housing market (Desmond, Citation2015; Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016). For females, adults, and national workers, labour discontinuity represents an additional layer of precarity that significantly affected their residential choices between 2013 and 2019. However, the model indicates that female workers are those who suffer most from the negative consequences of their discontinuous presence in the labour market, which is in line with the conclusions of Martínez-Gayo and Martínez-Quintana (Citation2020), and the persistent feminization of domestic and family duties in Spanish society. Unlike in Terry’s account (2017) of housing precarity for seasonal workers, such effects are not necessarily related to work regulations or the extreme temporality of seasonal work, but rather to structural vulnerability in the face of a transforming urban housing market, whereas the scarcity of affordable residential options in the proximity of work locations could be translated into other dimensions of precarity in life and health.

At first sight, models with the groups of youngest and non-national workers seem less informative, as they barely identify indicators associated with residential mobility, although the descriptive statistics in reveal that they were more likely to have moved out of the city between 2013–2019 compared to adults and Spanish nationals. A few considerations can help to make sense of these results. First, residential mobility among these two sub-groups may be the result of mechanisms that are not captured by our model. McCollum and Trevena (Citation2021) emphasize how the residential mobilities of ethnic minorities follow distinctive patterns compared to those of non-migrants, as internal migration is often an extension of a broader process of resettlement starting at the time the migrant leaves the country of origin. Second, it may well also be the case that social and housing exclusion is manifested in the form of immobility, which can be related to insights from the literature on the late residential emancipation of young people (Eurostat, Citation2021) and on residential stability as a strategy to cope with vulnerable labour conditions (Preece, 2017). Finally, tourism work is often a choice of convenience aligned with the life trajectories of the youngest and non-national workers, for instance, providing a first job in the labour market, in line with Zampoukos (Citation2018).

As for the limitations of the analysis, our statistical approach, based on a longitudinal model and the temporal ordering of its variables, reduces the potential biases due to reverse causality in a cross-sectional analysis. However, our definition of residential mobility in the sense of a change of residence out of the city is necessarily limited, as it underestimates intra-municipal changes of residence. More precise geographical accounts of this phenomenon were not feasible with the currently available data, though changes of residence implying relocation outside the municipal boundary could be seen as a particularly harsh consequence of labour precarity compared to residential movements within a shorter distance. This is especially true in the context of the present study, given that the individuals within our sample were still working in the city in 2019, and therefore those who moved out have most likely increased the time they spend commuting to work, with all the possible negative consequences this could entail (Premji, 2018). A second limitation in our analysis is constituted by the exclusion of informal and undeclared work, which affects a non-negligible proportion of workers employed in the visitor economy (Williams & Horodnic, Citation2020). This prompts the use of alternative sources of data and methods to arrive at a more comprehensive picture of labour conditions among workers in tourism-related occupations. Also, the operationalization of our category of tourism workers is likely to have exceeded the boundaries of the visitor economy, as some of its services are also accessed by non-visitors. As for this, future studies should look more closely at possible differences in terms of labour conditions and residential mobilities by groups of workers in different subsectors.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations underlined above, the research reported in this paper contributes key insights to the tourism geographies literature, especially on debates on tourism development and socio-spatial exclusions. At the same time, they relate to the labour geography field, as they track the peculiar space-time dynamics of the tourism workforce as opposed to workers employed in different sectors, and the interplay between tourism work, precarity, and residential mobility. Bridging these two areas of research, as advocated by Ioannides and Zampoukos (2018), we brought to the fore the inherently unequal geographies that are ingrained in the production of tourist space, and more specifically in the transformations experienced in the urban housing market.

In this sense, the main contribution of our study for the tourism geographies field may well be that tourism-intensive urban areas, in which a highly competitive tourist market drives the devaluation and precarisation of labour (Russo & Segre, Citation2009; Church & Frost, Citation2004), are likely to experience various forms of social exclusion. These have a distinct spatial dimension, mirroring the growth and intensification of tourist activity, and related with residential options in the face of an unaffordable housing market. In Barcelona, our results inform of workers being pushed at the margins, both in literal terms, being displaced to residential locations farther away from work centres, or figuratively, having to rely on immobilisation tactics, which may involve a self-imposed downgrading of residential conditions. In either case, the geography of tourism growth in the city becomes inextricable from the shifting social geography of disadvantage, dependence and marginalisation, gaining ground at the expenses of the promise of upwards social mobility and cohesion.

To the extent that the insights from the example of Barcelona can be generalised, these urban dynamics may well be a structural dimension of social change for European cities. As we pointed out in the introduction, and as is confirmed by the literature (e.g. Tulumello et al., Citation2020), the landscape of Barcelona is not substantially different from that of many other cities and regions that bought into neoliberal urban planning to sustain their recovery from the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. The related social disadvantage is not only a matter of inquiry per se, but should become a primary concern for future policy efforts within broader agendas of transition to sustainable tourism and mobility in a post-carbon economy.

This question also deserves closer attention in light of possible reconfigurations of the spatialities of precarious labour in the post-pandemic era (Alexandri & Janoschka, Citation2020). The tourism sector was badly hit during the COVID-19 emergency, causing a significant number of workers and their households to lose their means of subsistence either temporarily or permanently. Mid- and long-term impacts on the housing pathways of these workers are still uncertain, but our results ensure decent work and dignity in employment is key to preventing the negative effects of precarity in other spheres of personal and collective life. Although we did not excavate the theoretical implications of labour exclusion on destination development, this is possibly an object for future research within the framework of tourism and the geography of evolutionary economics (Brouder, Citation2019), whereby policy innovations tackling precarious labour and affordable housing may represent a path-shaping mechanism towards sustainable post-COVID alternatives (Brouder, Citation2020; Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is part of project SMARTDEST – Cities as Mobility Hubs: Tackling Social Exclusion Through ‘Smart’ Citizen Engagement (2020–2022), which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 RIA program under Grant Agreement no. 870753. This publication is part of the R+D+i project ADAPTOUR (contract number PID2020-112525RB-I00) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033..

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the Spanish Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Riccardo Valente

Riccardo Valente specializes in the analysis of socio-spatial deprivation at the smallest geographical levels, mostly from a quantitative perspective. He was awarded a PhD summa cum laude by the University of Barcelona in January 2016 for a dissertation on crime and inequality in Barcelona. His work has been published in top-journals and he has been involved in dozens international conferences. He acted as the scientific coordinator of the Horizon 2020 MARGIN project (ref. 653004) between 2015 and 2017 on behalf of the University of Barcelona. He currently holds a post-doctoral position at the Department of Geography, Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

Benito Zaragozí

Benito Zaragozí is professor of Geography at the Department of Geography of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili. He is also a member of the GRATET research group and he has made research stays in centers in the US, Italy and Spain. Dr. Zaragozí participates in international journals with a high impact index, as author and reviewer. In his studies, he addresses various geographic problems, exploring novel approaches to Geographic Information Technologies and Sciences (TIG and GIScience). These papers emphasize scientific reproducibility through the use of Free and Open Source Software, reproducible workflows, and Open Data.

Antonio Paolo Russo

Antonio Paolo Russo is Professor of Urban Geography and Serra Húnter Fellow with the Department of Geography, Universitat Rovira i Virgili. He is the coordinator of the PhD program in Tourism and Leisure of the Faculty of Tourism and Geography, and lectures in under- and postgraduate courses on destination management and cultural tourism. Dr. Russo is author of more than 40 publications in academic journals and books. He is member of the research group GRATET and advisor for local governments and international institutions. Currently, he leads the H2020 project ‘SMARTDEST’ tackling tourism mobilities and social exclusion.

References

- Alexandri, G., & Janoschka, M. (2020). ‘Post-pandemic’ transnational gentrifications: A critical outlook. Urban Studies, 57(15), 3202–3214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020946453

- Arbaci, S., & Tapada-Berteli, T. (2012). Social inequality and urban regeneration in Barcelona city centre: Reconsidering success. European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(3), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776412441110

- Barbier, J. C. (2011). Employment precariousness in a European cross-national perspective. A sociological review of thirty years of research [CES Working Papers]. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00654370

- Barnett, S., Ganzerla, S., Couti, P., & Moland, S. (2020). European Pillar of Social Rights Cities delivering social rights. Access to affordable and social housing and support to homeless people. Eurocities.

- Baum, T., Cheung, C., Kong, H., Kralj, A., Mooney, S., Nguyễn Thị Thanh, H., Ramachandran, S., Dropulić Ružić, M., & Siow, M. (2016). Sustainability and the tourism and hospitality workforce: A thematic analysis. Sustainability, 8(8), 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080809

- Biagi, B., Lambiri, D., & Faggian, A. (2012). The effect of tourism on the housing market. In M. Uysal, R.R. Perdue, & M.J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research (pp. 635–652). Springer.

- Bianchi, R. (2009). The ‘critical turn’ in tourism studies: A radical critique. Tourism Geographies, 11(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903262653

- Bobek, A., Pembroke, S., & Wickham, J. (2018). Living with uncertainty. Social implications of precarious work. Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

- Bobek, A., Pembroke, S., & Wickham, J. (2021). Living in precarious housing: Non-standard employment and housing careers of young professionals in Ireland. Housing Studies, 36(9), 1364–1387. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1769037

- Bolíbar, M., Galí, I., Jódar, P., & Vidal, S. (2020). Precariedad laboral en Barcelona: un relato sobre la inseguridad. Resultados de la Encuesta a los Parados y Precarios de Barcelona 2017-2018. UPF.

- Bolton, S. C. (2009). The lady vanishes: Women’s work and affective labour. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 3(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWOE.2009.025400

- Borg, I. (2015). Housing deprivation in Europe: On the role of rental tenure types. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2014.969443

- Brouder, P. (2019). Towards a geographical political economy of tourism. In Müller, D. K. (Ed.), A research agenda for tourism geographies (pp. 71–78). Edward Elgar.

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Campbell, I., & Price, R. (2016). Precarious work and precarious workers: Towards an improved conceptualisation. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 27(3), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304616652074

- Cañada, E. (2017). Un turismo sostenido por la precariedad laboral. Papeles de Relaciones Ecosociales y Cambio Global, 140, 65–73.

- Cañada, E. (2018). Too precarious to be inclusive? Hotel maid employment in Spain. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1437765

- Church, A., & Frost, M. (2004). Tourism, the global city and the labour market in London. Tourism Geographies, 6(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461668042000208462

- Clair, A., Reeves, A., Loopstra, R., McKee, M., Dorling, D., & Stuckler, D. (2016). The impact of the housing crisis on self-reported health in Europe: Multilevel longitudinal modelling of 27 EU countries. European Journal of Public Health, 26(5), 788–793. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw071

- Clancy, M. (2022). Tourism, financialization, and short-term rentals: The political economy of Dublin’s housing crisis. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(20), 3363–3380. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1786027

- Clark, W. A., Deurloo, M. C., & Dieleman, F. M. (2003). Housing careers in the United States, 1968–93: Modelling the sequencing of housing states. Urban Studies, 40(1), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220080211

- Cocola-Gant, A. (2019). Gentrification and displacement: Urban inequality in cities of late capitalism. In Schwanen, T. and R. Van Kempen (Eds.), Handbook of urban geography (pp. 297–310). Edward Elgar.

- Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Findlay, A. (2016). Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 352–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515575417

- Desmond, M. (2015). Unaffordable America: Poverty, housing, and eviction. Fast focus. Institute for Research on Poverty, 22, 1–6.

- Desmond, M., & Gershenson, C. (2016). Housing and employment insecurity among the working poor. Social Problems, 63(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spv025

- Dustmann, C., Schönberg, U., & Stuhler, J. (2017). Labor supply shocks, native wages, and the adjustment of local employment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1), 435–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw032

- Eurostat (2021). Estimated average age of young people leaving the parental household by sex [Data set]. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/yth_demo_030/default/table?lang=en

- Goodwin, H. (2019). Barcelona - crowding out the locals: A model for tourism management. In Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (Eds.), Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions (pp. 125–138). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Herbers, D. J., Mulder, C. H., & Modenes, J. A. (2014). Moving out of home ownership in later life: The influence of the family and housing careers. Housing Studies, 29(7), 910–936. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2014.923090

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Jordan, L. P. (2017). Introduction: Understanding migrants’ economic precarity in global cities. Urban Geography, 38(10), 1455–1458. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1376406

- Jordhus-Lier, D. C. (2014). Fragmentation revisited: Flexibility, differentiation and solidarity in hotels. In Jordhus-Lier, D. and Underthun, A. (Eds), A hospitable world? Organising work and workers in hotels and tourist resorts (pp. 39–51). Routledge.

- Julià, M., Vanroelen, C., Bosmans, K., Van Aerden, K., & Benach, J. (2017). Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. International journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 47(3), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731417707491

- Llorca-Rodríguez, C. M., Chica-Olmo, J., & Casas-Jurado, A. C. (2021). The effects of tourism on EU regional cohesion: A comparative spatial cross-regressive assessment of economic growth and convergence by level of development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(8), 1319–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1835930

- Marshall, T. (2004). Transforming Barcelona: The renewal of a European metropolis. Routledge.

- Martínez-Gayo, G., & Martínez-Quintana, V. (2020). Precariedad laboral en el turismo español bajo la perspectiva de género. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 18(4), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2020.18.046

- McCollum, D., & Trevena, P. (2021). Protracted precarities: The residential mobilities of Poles in Scotland. Population, Space and Place, 27(4), e2438. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2438

- Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. (2020). Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales. Guía del contenido. https://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/320b09c6-dc33-42be-b532-08880e618742/MCVLGuia20201007.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- Mura, P., & Wijesinghe, S. N. (2021). Critical theories in tourism–a systematic literature review. Tourism Geographies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.1925733

- Novy, J., & Colomb, C. (2019). Urban tourism as a source of contention and social mobilisations: A critical review. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1577293

- Nuti, A. (2018). Temporary labor migration within the EU as structural injustice. Ethics & International Affairs, 32(2), 203–225. https://doi.org/10.1017/S089267941800031X

- Preece, J. F. (2018). Immobility and insecure labour markets: An active response to precarious employment. Urban Studies, 55(8), 1783–1799. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017736258

- Premji, S. (2017). Precarious employment and difficult daily commutes. Relations industrielles, 72(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1039591ar

- Robinson, R., Martins, A., Solnet, D., & Baum, T. (2019). Sustaining precarity: Critically examining tourism and employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 1008–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1538230

- Rodgers, G. (1989). Precarious work in Western Europe: The state of the debate. In Rodgers, G. & Rodgers, J. (Eds), Precarious jobs in labour market regulation: the growth of atypical employment in Western Europe (pp. 1–16). ILO-International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Ruiz-Almar, E., Aparicio-Moreno, R., & Serrano-Martí, M. (2022). L’habitatge a l’AMB. https://www.amb.cat/es/web/territori/urbanisme/estudis-territorials/detall/-/estuditerritorial/evolucion-del-sector-de-la-vivienda-en-el-area-metropolitana-de-barcelona/431358/11656

- Russo, A. P., & Scarnato, A. (2018). “Barcelona in common”: A new urban regime for the 21st-century tourist city? Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(4), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1373023

- Russo, A. P., & Segre, G. (2009). Destination models and property regimes: An exploration. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.04.002

- Salazar, N. (2020). On imagination and imaginaries, mobility and immobility: Seeing the forest for the trees. Culture & Psychology, 26(4), 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X20936927

- Terry, W. (2017). Precarity and guest work in U.S. tourism: J-1 and H-2B visa programs. Tourism Geographies, 20(1), 1–22.

- Tulumello, S., & Allegretti, G. (2021). Articulating urban change in Southern Europe: Gentrification, touristification and financialisation in Mouraria, Lisbon. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420963381

- Tulumello, S., Cotella, G., & Othengrafen, F. (2020). Spatial planning and territorial governance in Southern Europe between economic crisis and austerity policies. International Planning Studies, 25(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1701422

- Valente, R., Russo, A. P., Vermeulen, S., & Milone, F. L. (2022). Tourism pressure as a driver of social inequalities: A BSEM estimation of housing instability in European urban areas. European Urban and Regional Studies, 29(3), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764221078729

- Walmsley, A., Koens, K., & Milano, C. (2021). Overtourism and employment outcomes for the tourism worker: Impacts to labour markets. Tourism Review, 76,1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2020-0343

- Williams, C. C., & Horodnic, I. A. (2020). Tackling undeclared work in the tourism sector. https://effat.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/6A-EU-UDW-Platform-Report-Tackling-undeclared-work-in-the-tourism-sector-2020-1.pdf

- Wolkowitz, C. (2006). Bodies at work. Sage.

- World Travel & Tourism Council. (2019). Economic impact report. https://wttcweb.on.uat.co/Research/Economic-Impact

- Zampoukos, K. (2018). Hospitality workers and the relational spaces of labor (im)mobility. Tourism Geographies, 20(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331259