Abstract

This paper examines the role of public funding in transforming tourism pathways in sparsely populated Arctic destinations, comparing Northern Sweden and Finnish Lapland. Our theoretical framework considers destination path plasticity and moments of change through the lens of geographical political economy to understand patterns of uneven development. This perspective helps explain how regional development funding driven by multi-scalar political priorities and global markets set structural conditions for tourism. We present a spatial analysis of public funding between 2007 and 2021 for private firms and public projects, complemented by document analysis and expert interviews. We find that public funding in Finnish Lapland has largely reinforced ‘Arctification’ and export-driven tourism in a few locations. In Northern Sweden, it has focused more on redistributing resources to micro-businesses and broader socio-economic development in lagging regions, yet with limited impacts on changing dominant tourism pathways. Public projects improved knowledge creation and networking among public and private actors but were largely unable to consolidate emerging pathways in the long run. Overall, regional development funding supported incremental change around existing pathways and had limited transformative effects in response to shocks or disruptive moments due to the rigid nature of funding programmes.

Introduction

The ‘paths metaphor’ within evolutionary economic geography (EEG) has become a popular framework for explaining continuity and change in destination development (Brouder et al., Citation2017; Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Ma & Hassink, Citation2014). A range of path trajectory concepts have been used to examine interactions between agency, structure, history, and decisive moments of transformation in the dynamic evolution of destinations (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017). In addition to agency-focussed analyses of path-making by firms (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), the central role of political and socio-economic structures for destination evolution have also been emphasized (Carson & Carson, Citation2017). Particularly work on path plasticity provides a useful institutional lens to understand how destination stakeholders’ innovation activities interact with existing governance and policy configurations (Halkier & Therkelsen, Citation2013). Instead of focussing primarily on ‘change agency’, this perspective considers the vital role of ‘reproductive agency’, which induces phases of stability through consolidation and replication of economic paths (Bækkelund, Citation2021).

The specific junctures of pathway transformations have also attracted increasing attention. Such moments of change are theorized to be prompted by spontaneous trigger events (e.g. natural, terrorist, and economic crises) and selective ones, including anthropogenic policy alterations (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017). The latter include fiscal and regulatory interventions, which may have transformative effects on destination paths that are currently not well understood. Tourism research has paid little attention to the function of public funding, investments, or credit in the development of destination geographies, and this paper addresses this gap by examining the role of structural funding for pathway evolution in the specific context of Arctic tourism destinations.

Our analysis focuses on the cases of Finnish Lapland and Northern Sweden, including the counties of Norrbotten and Västerbotten. These regions are classified as northern sparsely populated areas (NSPAs) within the European Union (EU) and are part of the European Arctic. Tourism is frequently promoted as a means of regional and cross-border development and has grown strongly but spatially unevenly over the past decades, driven by an increasing trend of ‘Arctification’ (Bohn & Varnajot, Citation2021; Lundmark et al., Citation2020). Characteristic of this tourism path is the production of highly commodified nature-based activities rooted in a ‘cryospheric gaze’ upon northernmost Europe as an Arctic experience wilderness for international and wealthier travellers (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022). By adopting a spatial and longitudinal viewpoint, this study contributes to a better understanding of institutional accounts of moments of change (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017) and offers important insights into how public sector organisations, which are themselves influenced by political priorities and global market dynamics, shape destination pathways.

We draw on recent discussions within geographical political economy (GPE) to illustrate how analyses of destination evolution benefit from perspectives considering wider processes of capitalist production, circulation, consumption, and regulation, which co-evolve in space and time (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019; Sheppard, Citation2011). Hence, history and the legacies of past uneven development influence current path trajectories with respect to the availability of natural and human resources, social structures, investment capital, R&D facilities, good governance, and institutional thickness (Pike et al., Citation2016). Institutional and individual actors valorise these assets, reinforce or open up new economic paths, and thereby transform these pre-existing structural landscapes (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). From a GPE standpoint, public funding functions as an institutional instrument for spatial fixes through which the contradictions of capitalist accumulation can be temporally forestalled by ensuring the continuation of economic growth (Harvey, Citation2020).

Departing from this, we address the following research questions:

To what extent does funding reinforce or trigger changes in existing tourism pathways?

How do funding allocations reflect changes in pathways and development priorities following particular disruptive moments?

How do institutional practices alongside global processes of capital accumulation influence regional tourism funding strategies with respect to uneven development?

We first outline our theoretical framework and then discuss public (particularly EU) funding for tourism development. Following the methods and an introduction to historic tourism pathways in our case regions, we analyze the spatial distribution of tourism funding and identify its influence on destination evolution, both as an active trigger and a reactive response to disruptive moments. Emphasis is placed on agency-structure relationships in conjunction with political-economic priorities and capital accumulation practices for regional development.

Theoretical framework

Institutional environments, including (in)formal norms, rules, and structures governing human behavior, are decisive elements that pre-condition path trajectories of tourism regions (Mellon & Bramwell, Citation2018). Especially in remote and sparsely populated areas, respective research highlights the crucial role of institutional interventions for mitigating uneven or truncated regional development (Carson & Carson, Citation2017; Giordano, Citation2017). This also applies to NSPAs of Europe, including in Sweden and Finland, which have been facing distinct development constraints due to dispersed industry actors, long distance to markets, dependency on external investors, and limited access to human resources (Müller & Jansson, Citation2007). Within this distinctive geographical context, our theoretical framework considers the role of public funding from three integrated perspectives, namely path plasticity, moments of change, and uneven development.

While an increasing body of literature has focused on new path creation and radical innovation (see Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) for a comprehensive review), the concept of path plasticity may be better suited to explaining trajectories in regional tourism destinations where multiple development curves typically overlap and few individual paths can be reliably singled out as radical or ‘new’. Change processes in destinations or regions may therefore emerge as incremental alterations rather than sudden pathway transformations (Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017; Halkier & Therkelsen, Citation2013; James & Halkier, Citation2016; Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). Such ‘paths-as-process’ perspectives share a similar long-term and sequential view on adaptive path evolution (Martin, Citation2009), yet radical change agency, rather than exogenous events or institutional structures, is usually foregrounded as the main driver of path transformations (Benner, Citation2022). Path plasticity in turn emphasizes the stability and comprehensiveness of institutional and governance configurations, which set the framework for individual actors’ innovation capacity (Strambach, Citation2010). The strategic selectivity of institutions legitimizes some actors’ mindful path creation while limiting access to resources and power for others (Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013; Stihl, Citation2022). Hence, institutions at different scales create ‘opportunity spaces’ not only for innovative entrepreneurs who forge new paths but also for actors who extend existing paths (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Bækkelund (Citation2021) underscores that replicative entrepreneurship and consolidative place-based leadership are crucial for stabilizing emerging destination pathways. Following this, our first research question focuses on whether public funding seems to reinforce existing pathways in an incremental way or trigger more radical transformations. Through expert interviews, we identify the particular opportunity spaces and their underpinning rationale that institutions provide through funding for tourism entrepreneurs and project networks. By mapping fund allocation, we trace the spatial outcomes of institutional leadership and support for change and reproductive agency.

The second component of our framework considers ‘trigger events’, including exogenous shocks or endogenous policy alterations, as critical moments of change within path-plastic or path-as-process perspectives (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017; Benner, Citation2022). Such critical junctures open up possibilities for pathway transformations, however different forms of agency play a key role in shaping the direction of industry trajectories (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Our subsequent research question seeks to understand the role of funding as a reactive policy device to disruptive moments and as an active trigger for pathway alterations itself. Specifically, we focus on how funding bodies utilize financial instruments to create or respond to critical pathway junctures. This aspect also considers what kind of trigger events are institutionally recognised and why. Empirically, we unearth these issues through semi-structured interviews with institutional experts in addition to policy document analysis.

The third pillar of our framework draws on concepts derived from GPE, an appraoch frequently employed as an explanatory layer for the evolution of economic trajectories under capitalism (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019; Pike et al., Citation2016). A key concern for GPE is the examination of uneven development, emerging through multi-scalar relations between places in conjunction with biophysical, economic, political, and socio-cultural dynamics (Sheppard, Citation2011). From this angle, the legacies of past development paths, sociospatial relations, and the prevailing rationality that underpins economic development are constitutive of destination evolution (Mellon & Bramwell, Citation2018). Moreover, GPE emphasizes the links of local pathways to global economic trajectories (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Especially in export-oriented destinations, transformation rests frequently on importing extra-regional sources of knowledge and commercial networks (Brouder, Citation2017) while institutions function as gatekeepers for actors to connect local assets to global markets. Herein lies the political component of evolutionary economy. In our case, regional administrations’ and funding agencies’ time and space specific economic strategies and decision-making for diminishing (or unintendedly aggravating) uneven development constitutes a political act (Ladner & Sagner, Citation2022). Our third research question, thus, examines how public funding strategies reinforce or mitigate uneven development, and what factors grounded in broader political priorities and global processes of capital accumulation might explain these dynamics. We also pay attention to how funding is employed as a spatio-temporal fix to trigger events, market failure, and capitalist crises in general (Harvey, Citation2020). Mapping out funds allocation over time provides us with empirical evidence of spatially uneven development and the interviews offer complementary explanations of institutional practices.

Summing up, we depart from the notion that evolution in destinations is an incremental process in which institutions mitigate the crisis proneness of capitalism and define the opportunity spaces for actors (Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017). We look into the particular role of public funding - a policy instrument that has remained empirically under-researched in tourism. Through a spatial analysis of fund allocation, we examine how development policy becomes inscribed into destination paths and the geography of regions. This also advances our understanding of institutions’ mediating structure-agency functions in economic evolution (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020).

Public funding for tourism and regional development

EU governance of tourism materializes principally in form of meta-policies for regional, economic, and transport development, which are firmly embedded in the Commission’s Structural Funds programmes (Halkier, Citation2010). Finland and Sweden are eligible for the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF), the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFR), and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF). These funds are pooled with national resources for the receiving regions and represent ‘the most significant impact of the EU’ in Finland’s and Sweden’s northernmost counties (Lidström, Citation2020, p. 146). With Sweden and Finland joining the EU in 1995, new regional institutions developed to administer funding in line with national, regional, and EU policies. However, funding responsibilities are dispersed among numerous organizations and levels, especially in Sweden (Appendix 1).

In NSPAs, tourism development is promoted within EU funding programmes as a means ‘to exploit geographical specificities as ‘assets’’ (Giordano, Citation2017, p. 876) for endogenous growth and to enhance cross-border regional development (Shepherd & Ioannides, Citation2020). The global financial crisis in 2008/2009, widely considered as a key disruptive moment for tourism, accelerated the transformation of regional policy and funding strategies from redistributive state intervention to strategies prioritizing smart specialization and regional competitiveness spurred by small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) (Romão, Citation2020). Yet, this shift has gained uneven foothold, and Northern Sweden is a particular case where the social democratic idea of economic redistribution to lagging peripheries still persists.

Respective research on funding programmes has discussed the effects of different EU-funded projects, particularly INTERREG projects (cross-border development initiatives co-financed by ERDF), on destination and regional development. Shepherd and Ioannides (Citation2020) found that INTERREG projects are appreciated for offering considerable financial incentives for chronically underfunded tourism organizations in locations outside major tourism hotspots. Yet, the projects’ development objectives often remain unaccomplished due to the short-lived nature of these initiatives and an isolated top-down institutional setup (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017). After the funding period ceases, there are frequently no functional public–private partnerships or tourism firms in place to convert the project work into viable commercial paths (Prokkola, Citation2011). This ‘administrative short-termism’ hampers strategic long-term planning for sustainable regional development (Sjöblom, Citation2009). Furthermore, an over-reliance on external funding bears the danger that organizations focus more on grant-writing and meeting funders’ requirements instead of supporting locally-grounded initiatives (Shepherd & Ioannides, Citation2020). While managing authorities might profit economically from tourism projects, multiplier effects on industries and communities remain marginal (Prokkola, Citation2011).

Micro-sized businesses and SMEs can obtain EU funds pooled with national financing, but empirical research on the path-making effects of tourism development and investment grants for private actors is very limited, partly because of the lack of comprehensive and comparable funding data (Tirado Ballesteros & Hernández Hernández, Citation2017). One notable exception is the study by Almstedt et al. (Citation2016), which found that rural development funding in Sweden, despite providing support for tourism marketing, accommodation and activities, added little to the restructuring of the rural economy due to relatively small amounts of funding within overall fund allocations. Hence, knowledge gaps exist with respect to how regional development funding is employed by institutional actors and tourism entrepreneurs over time. This study makes an important methodological and empirical contribution to this field by mapping out and examining fund allocation in a comparative and longitudinal manner. We visualize the geography of tourism funding for firms and projects in NSPAs and, thus, offer micro-level insights into the interface between structure and agency (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), which is nonetheless connected to macro-level political economy.

Methods

The case regions for this research were Finnish Lapland and Northern Sweden. Finnish Lapland is both an administrative region and a formal regional tourism destination. As there is no single equivalent Lapland region on the Swedish side, the combined region ‘Northern Sweden’, including the two counties of Västerbotten and Norrbotten, was selected as a Swedish comparison. Together, these two counties officially constitute Sweden’s part of the Arctic and comprise the majority of regional destinations using various definitions of Lapland for place marketing. While we draw comparisons between the two countries, our analysis also identified important differences between the two Swedish counties, as illustrated in the findings.

Our empirical material comprises fund allocation data, semi-structured interviews, and policy documents. The first part of the research involved mapping out fund allocation to visualize the tourism pathway characteristics supported through public funding and to compare the differences and similarities in uneven development between Lapland and the two Swedish counties. We obtained ERDF, INTERREG and national funding data for Finnish Lapland and Northern Sweden from publicly accessible databases for the period 2007-2021 (Appendix 2). Private firm funding data in Västerbotten and Norrbotten was acquired from the county councils and the county administrative boards. For Norrbotten, we only received detailed funding amounts for each firm until 2017 and regional aggregates for 2017 to 2021, so we assigned averages to each funded firm. We converted the Swedish data, expressed in SEK, into Euro according to the annual currency exchange rates reported by the Swedish Central Bank (Riksbank, n.d.). All funding data were adjusted to 2021 constant prices, in accordance with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) values stated by Statistics Sweden (Citation2023) and Statistics Finland (Citation2022). The dataset was split into funds for private firms and funds for public projects. The presentation of our findings follows this distinction due to the different objectives and actors involved in utilizing funding for public projects and private business development.

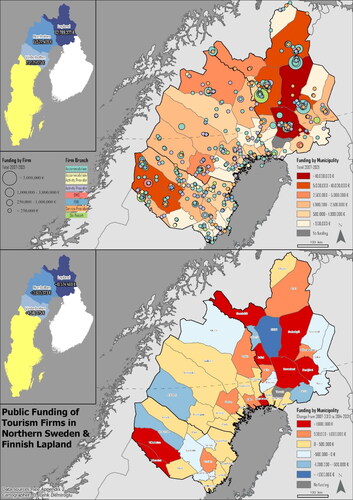

Firm data were condensed into firm name, start year of funding, and amount of funds used. We manually added the geolocation as well as a branch categorization of the firms, but some limitations exist due to the lack of information on the exact physical location of the funds in some cases. Firms that were granted funding but did not use the money were excluded from the final dataset, which was mapped out with ArcGIS Pro 3.1 to identify the spatial distribution of firm investments. Both the firm-specific total funding information and the funding differences between the major funding periods (2007-2013 and 2014-2021) were aggregated at the municipal and county/region levels and displayed on different maps ().

Data on public projects were processed to quantify the money spent for tourism and to identify the key actors for tourism projects in each region. Given the heterogeneity of the data, it was not possible to access detailed information on each project’s focus area, which would have allowed for a deeper analysis. Moreover, due to the incomplete information in some years on firms and projects, we might have missed some funded public and private tourism initiatives. In the Swedish case, funding over 25 million SEK (∼ 2.5 million EUR) is handled by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket) and we could not obtain information on these larger investments in Norrbotten and Västerbotten. The provided funding amounts should therefore be seen as trends instead of absolute numbers.

The second part of the research consists of semi-structured expert interviews and the analysis of policy documents related to funding and regional development (Appendix 2). These empirical materials add an explanatory layer to the spatial mapping results and offer a deeper understanding of funding procedures, policy priorities, global-local market forces, and the role of funding as a reactive or proactive institutional instrument. We conducted seven interviews (two in Finnish Lapland, two in Norrbotten, one in Västerbotten, and two at supranational level) with representatives of organisations responsible for regional development and tourism. For confidentiality reasons, we categorize the interviewed experts only according to the type of organizations they represent.

I1: regional funding agency

I2: Interreg tourism project

I3 and I4: European Union regional office

I5 and I6: destination management organization

I7: regional planning administration

Interview questions broadly covered regional tourism development trends, tourism funding objectives in relation to regional development, the perceived impacts of funding for tourism firms, destinations, and public-private organizations, funding in response to particular shocks, as well as the possibilities and challenges of project-based development. The interviews were conducted in English, lasted between 40-90 minutes, and were transcribed verbatim. We analysed the interviews and documents together in a thematic content analysis, with codes mainly deducted from the conceptual framework and the research questions.

Tourism pathways in Northern Sweden and Finnish Lapland

Tourism across Northern Sweden and Finnish Lapland has historically been about outdoor recreation and nature-based activities (e.g. hiking, cross-country skiing, camping, fishing). This type of leisure has traditionally attracted domestic or cross-border tourists, often from within the northern regions, along with high rates of second home ownership, a largely self-contained form of travel, and ultimately a small and dispersed tourism sector dominated by micro-sized businesses. While summer has been the main tourist season for much of the North, the increasing popularity of downhill skiing during the 1970s and 1980s triggered the construction of numerous winter sports resorts. Even though the winter season became more profitable and commercialised, the resulting infrastructure and business development remained highly localised (Byström, Citation2019; Kauppila, Citation2011). Despite these broad similarities, tourism development was pursued divergently in the three counties leading to markedly different destination pathways and spatial patterns. The reasons for this may also lie in different economic histories. Resource extraction and mining declined more rapidly in Finnish Lapland than in Northern Sweden, and tourism was harnessed as a substitute export industry underpinned by political hopes for economic revival (Müller & Jansson, Citation2007). In addition, Lapland adopted spatial industry planning for tourism already from the 1970s and strategic planning from the mid-1990s onwards, while no comprehensive tourism development scheme exists at the regional level in Northern Sweden due to different administrative devolution.

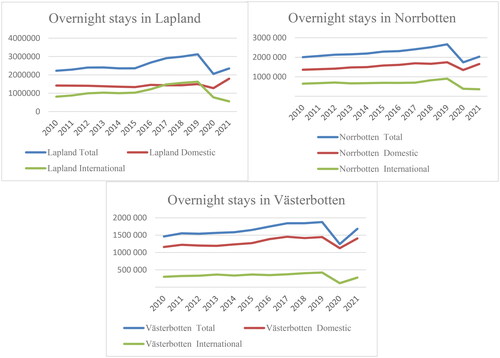

As illustrated in , Västerbotten is the least developed in terms of export-oriented tourism, attracting mostly domestic and cross-border visitors during summer for business reasons, shopping, and visiting friends and relatives (Lundmark et al., Citation2020). Tourism hotspots are predominantly located along the urban coast (Umeå and Skellefteå) and in a few small mountain destinations and ski resorts. The remaining inland largely lacks outstanding attractions, amenities, and tourism clusters. Nevertheless, small-scale firms specializing in nature-based activities and camping exist, along with a few dispersed entrepreneurs targeting international markets.

Figure 1. Overnight stays in Lapland, Norrbotten and Västerbotten. Sources: Statistics Finland (Citation2022) and Tillväxtverket (Citation2022).

International tourists play a larger role in Norrbotten, where export-focused tourism clusters have emerged across the inland (Kiruna, Jokkmokk, Arjeplog, Arvidsjaur) and the municipalities bordering Finland (Lundmark et al., Citation2020). Particularly the famous Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi/Kiruna, which opened up a new path for winter tourism beyond traditional skiing, is a hotspot for international travellers (Lundmark et al., Citation2020; Stihl, Citation2022). Several local DMOs alongside the Swedish Lapland Visitors Board (the regional DMO comprising Norrbotten and parts of Västerbotten) promote northernmost Sweden as an Arctic destination to a global audience. This spatial production process of the North as part of the Arctic is termed ‘Arctification’ and rests upon representations of the region as an exotic snowy wilderness, where tourists purchase highly commodified soft winter experiences, including snowmobile excursions, aurora borealis tours, and reindeer or husky safaris (Bohn & Varnajot, Citation2021; Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022).

Arctification as a destination pathway is most strongly established in Finnish Lapland. As shows, international tourism, peaking during the winter season, has outnumbered domestic visitation since 2017 up until the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to Lapland’s centre-based development strategy, which governed regional tourism planning for decades, sectoral activity is highly polarised around the ski resorts Levi, Ylläs, Saariselkä, Pyhä-Luosto, and Salla in addition to the regional centre Rovaniemi (Kauppila, Citation2011). More recently, in sparsely populated municipalities where tourism used to be small-scale and directed towards domestic markets, hospitality and activity infrastructure for larger volumes and international visitors has been growing remarkably. Again, products mostly coalesce around Arctic-themed nature activities coupled with an increase in micro-enclave resorts targeting well-off traveller segments. Arctification has also opened up new tourism paths in the established winter sport resorts, thus diversifying and internationalizing the more traditional skiing market (Rantala et al., Citation2018). Another prominent export tourism pathway in Finnish Lapland relying on images of winter wonderlands has revolved around Christmas tourism. In the mid-1980s, Rovaniemi was declared the official hometown of Santa Claus, followed by the creation of the Santa Claus Village attraction. Ever since, short-stay charter trips from November until January are popular products sold by numerous international tour operators.

Findings

The findings are divided into funding for public projects and private firms due to their different dynamics and impacts on destinations. While public projects are implemented by institutional networks aiming at social innovation and the preconditions for economic development, private firm funding supports business development directly.

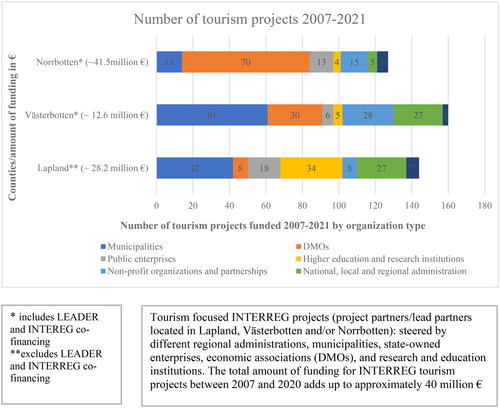

Funding for public tourism projects

outlines fund receiving organisations and spending for public tourism projects between 2007 and 2021, showing significant differences between the three regions. While municipalities in Västerbotten and Lapland are strongly involved in tourism projects, the Swedish Lapland Visitors Board alongside local DMOs are the most dominant actors in Norrbotten. Higher education and research institutions play a major role in implementing tourism projects in Lapland compared to Västerbotten and Norrbotten. In Västerbotten, non-profit organizations, including local interest groups, are more active in steering tourism-related initiatives than in the other two regions.

Figure 2. Organizations receiving funding for tourism projects between 2007 and 2021. Sources: Eura2007 (Citationn.d.), Eura2014 (Citationn.d.), Keep.eu (Citationn.d.) and Tillväxtverket (Citationn.d.).

The stated key objective for funding of public projects is to create or strengthen a path in a specific place or sector and, thus, to generate added economic and socio-cultural value and growth for the whole region, country, and the EU (Europaforum Norra Sverige, Citation2017). The majority of public initiatives sets destination development and sustainability through tourism entrepreneurship as the overarching goal. The funded projects can be broadly classified into destination infrastructure development, tourism product development, and institutional capacity building. Specific project themes respond mostly to global trends and dominant economic ideas, such as digitalization and experience technology or nature-based wellness tourism. An example of a project theme that got funding in all three regions is the marketization of Sámi culture and handicrafts. This underscores tourism’s role as a commercial outlet for Indigenous entrepreneurs to branch into new service activities. Moreover, Indigenous tourism products diversify a destination’s experiences and contribute to its ‘exotic’ image, particularly for international markets (Viken & Müller, Citation2017).

The interviewees considered infrastructural investment projects, such as airport enlargements or new hiking trails, as particularly important for destinations. Such inputs to a destination’s commons generate ‘opportunity spaces’ for local entrepreneurs, even if they are primarily consolidating and strengthening existing products and markets rather than fostering radically new pathways. Nevertheless, these are seen as crucial in regions characterized by small-scale and dispersed industry actors (Halkier & Therkelsen, Citation2013). Another dimension of the consolidative place-based leadership function of tourism projects mentioned in the interviews pertains to the creation of social networks. Cooperation and interaction between actors ‘who would otherwise never meet’ (I7) are seen as the key benefits of project work, outweighing the frequent lack of directly measurable economic growth effects. As noted by I4, ‘it is not really about the money but it’s more about the methodology and what it creates in the long-term [referring to soft and hard infrastructure]’. Projects mobilize social capital and institutional entrepreneurship in a path plastic manner and help to stabilize networked opportunity spaces, even if immediate tangible outcomes are limited.

Several interviewees conceded that these networks build up rather slowly and lasting cooperation is oftentimes limited to organizations and actors of similar status and power. This echoes previous research (Shepherd & Ioannides, Citation2020), which found that tourism organizations favour collaboration within existing (e.g. national or regional) boundaries instead of larger cross-border projects with new network partners. Furthermore, the bureaucratic and prescriptive guidelines for accessing EU and regional funding create uneven opportunity spaces by posing substantial difficulties and constraints for local stakeholders. Each EU funding period contains distinct aims that applicants must adhere to, and regional strategic planning and national-level goals further determine the scope of themes eligible for funding. Such top-down prescription sometimes clashes with local ideas, realities and conditions, thus hampering place-based and endogenous innovation. For instance, I7 specified that there occur mismatches between local industry needs, which are oftentimes simple material inputs to the tourism production process, but higher-level strategies prescribe projects on abstract themes that do not concern small and micro-sized tourism enterprises at all. In contrast, I4 emphasized the path-creating potential of EU programme requirements by fostering change agency because it forces actors to ‘renew [their] thinking …you have to be quite creative…it forces you to put yourself into a larger context. You have to work with others’.

The greatest challenge for public projects to profoundly impact destination paths regarding novelty and retention lies in the temporal limitation of projects. For the interviewees, crafting a substantial new path and a long-term development vision is difficult if funding is limited to two years, meaning that projects often result in ‘isolated activities’ without much coherence or continuity. Follow-up projects are difficult to obtain because new proposals formally require a different theme, thus constraining the sorts of reproductive actions and stability required to consolidate pathway development. Nonetheless, some projects have been able to create lasting effects. I7 mentioned a sustainable tourism certification scheme in Västerbotten that was not only successfully institutionalized after the funding period ended but prompted new market relations by attracting international tour operators. This example underscores the crucial role of scaling-up and coupling emerging local paths with global and competitive tourism markets (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019).

All interviewees agreed that public project funding is not well suited to respond to sudden shocks. Bureaucratic lock-in prevents spontaneous changes to project plans amidst a crisis and creates a time-lag between funding needs and disbursement. Especially ERDF funds are not designed for immediate crisis response, although they might facilitate post-crisis recovery or pre-crisis resilience strategies.

The interviewees also identified an inherent structural bias in public funding mechanisms towards larger and established actors, who possess the resources and know-how to write grant applications. Oftentimes ‘money goes where money already is’ (I4), but this dynamic sets a threshold for smaller organizations and reinforces paths that are already well established. In contrast, more substantial changes in pathways would require investments in emerging organizations with divergent ideas as I2 remarked. This situation highlights that strategic selectivity of institutions is tied to cultural conventions and these might constrain change agency and paths that are outside of endorsed development ideas and accumulation regimes (Berard-Chenu et al., Citation2022; Stihl, Citation2022; Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). It also points to the weight of financial power in contemporary capitalism and how it perpetuates uneven development even with policy interventions aiming to mitigate exactly that.

The cross-border INTERREG project ‘Visit Arctic Europe’ (VAE) exemplifies these issues. I2 noted that this initiative obtained an unparalleled amount of funds because the lead applicants were all well-known within the tourism business field, thus gaining the trust and support from financiers and participating businesses. VAE significantly reinforced Arctification in tourism across Norrbotten and Lapland, and to some extent Västerbotten, due to its marketing and development focus on the European Arctic as a seamless destination product, which became a unique selling point for global tour operators. The project consolidated the Arctification pathway also by making local tourism firms more attuned to the demands of international industry players. Moreover, the project’s success is also attributed to political-economic conditions beyond local control. I2 told that it was easy for VAE to promote Arctic tourism to the global travel sector because in the aftermath of terrorist attacks in other regions of the world, airlines rerouted their flight capacity to Nordic countries, which were perceived to offer safer destinations.

Funding for tourism firms

Small and micro-sized tourism firms can receive ERDF and national grants (Appendix 1) that cover around 50% of investment costs for new facilities and equipment, opening up new markets, or purchasing consultancy services. shows the spatial distribution of firm funding in Västerbotten, Norrbotten, and Lapland.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of funding for tourism firms in Finnish Lapland, Västerbotten and Norrbotten 2007–2021.

In Lapland, the Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY) grants financial support exclusively to export-oriented firms, with tourism and manufacturing being the prevailing sectors. Grants are primarily given to tourism companies targeting international travelers. Public investments (∼ 62,789,377 EUR) agglomerate around areas specifically planned for tourism. Companies in Rovaniemi municipality, followed by Sodankylä, received the lion’s share, but also businesses in the municipalities of Kittilä, Inari, Kolari, Pelkosenniemi with large tourist resorts secured between five and ten million Euro. Other municipalities with an increase in funding of more than one million Euro between 2014 and 2021 were Enontekiö, Kolari, Rovaniemi, Sodankylä, and Kemijärvi in Finland, and Haparanda, Vilhelmina, and Dorotea in Sweden. A single firm in Sodankylä, operating a glass igloo micro-resort and soft nature-based activities, was granted approximately 8.5% (∼8,413,966 EUR) of the total funding (98,888,511 EUR) issued in all three counties together. Several other companies in Lapland received financial assistance for the same type of Arctic-themed micro-resort product. Hence, funding clearly supported replicative entrepreneurship, which in turn strengthened the Arctic tourism pathway.

I2 explained that the reasoning behind these funding decisions is that by responding to global tourist market demands, fast returns on public investments with a minimal risk of failure can be expected. Additionally, a prerequisite for grant approval is the prospect of a business to grow. The system favours generally established firms over inexperienced industry newcomers, and guidelines mandating that companies have neither legal nor financial troubles in order to obtain funding. Financial support for accommodation projects in Lapland necessitates that applicants already possess contacts to tour operators, signifying sector-specific business expertise and export-readiness as I1 highlighted. The ELY centers also invite grant-seeking firms to consult with the institution prior to applying to ensure compliance with funding requirements. Currently, funding seeks to strategically foster the development of year-round tourism in Lapland and seasonal diversification away from the dominant winter tourism pathway, to enhance the sustainability of the tourism sector and to create more year-round employment. There are also attempts to encourage firm diversification, specifically when previous funding recipients apply again. ELY centers direct companies towards complementary products or new markets in line with EU and regional development objectives. Overall, Lapland’s funding strategy consolidates the dominant export-oriented destination path. Apart from aforementioned diversification efforts, there is little support for ‘no-growth’ business models or less commodified destination pathways. With respect to the geographical manifestation of fund allocation, the legacies of Lapland’s center-based tourism strategy are still dominant. Decades of investment and infrastructure development in the resort centers have created an uneven polarisation of tourism, which is only slowly dispersing.

The county councils of Västerbotten and Norrbotten pursue a different funding strategy. As illustrated in , funds are more evenly distributed across both Swedish counties than in Lapland. This can be partly explained by the absence of a comprehensive regional planning regime in addition to the traditional domestic (or regional) market focus and the small-scale structure of the tourism sector. Tourism in Northern Sweden has generally received less political support than in Lapland due to the greater economic weight of natural resource industries and manufacturing as I6 remarked. However, the counties’ regional development agencies prioritize funding for companies in the economically lagging inland areas over those in the coastal cities (Region Västerbotten, Citation2021). Another difference is that larger funds (above 25 million SEK) are handled by the national Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth and the regional administration hands out only lower amounts. Particularly Västerbotten grants many smaller funds, without a clear thematic product or market focus, to tourism firms scattered across the inland. There are only a few funding clusters around the largest tourist resort Hemavan-Tärnaby, and the smaller mountain destinations on the remote western fringe. Funding for Arctic tourism is not particularly apparent, and businesses invest mostly in expanding their existing operations, such as fishing tourism, nature-based activities, and camping grounds, catering typically to local and domestic customers. Around 40 to 50 percent of the funded companies receive grants in a repeated manner (Region Västerbotten, Citation2021), which reduces the risk of market failure and large misinvestments as firms expand their businesses incrementally but persistently. This funding strategy supports path plastic development in sparsely populated places and seems to be guided by social democratic principles of redistribution.

In Norrbotten, the number of Arctic soft nature-based activity providers and micro-resorts is clearly increasing, with funding agglomerating around the main winter tourism hotspots (Kiruna, Luleå, Arjeplog, and Arvidsjaur). A few growth-oriented and path-making entrepreneurs have emerged in some of these hotspots, prompting smaller actors around them to enlarge their tourism operations too. Together, they co-benefit from firm agglomeration and the resulting expansion of Arctic tourism paths.

In contrast, the interviewees also emphasized that new product or market innovations are often driven by highly entrepreneurial firms that are not dependent on public funding, operate largely outside of institutional frameworks, and rely on their own external (rather than local) business networks. These firms often generate successful localised paths but with limited spin-offs for broader regional industry learning and changing overall destination pathways. An exception is the place-based leadership of the Icehotel in Kiruna. Stihl (Citation2022) explains that the change agency of a single entrepreneur induced a shift in the whole local tourism sector from a rather marginal activity focused in the summer-season to a well-established and networked industry that provides high-quality winter products for wealthier market segments. At first, local tourism authorities did neither believe in nor support the Icehotel but success came about through commercial links to extra-regional actors (Stihl, Citation2022). The Icehotel paved the way for innovations in Arctic tourism and its product idea has been copied in many places across the region, oftentimes supported by public funding.

The relative in-/dependence on public sector support surfaced as well in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to international mobility restrictions, many tourism firms halted their project implementation plans in Lapland, also because banks withdrew loan approvals. Nevertheless, firm investments recommenced in late 2021 when tourism rebounded, meaning that the pandemic signified a short break before reverting to previous funding plans and development paths. In 2020, predominantly larger tourism firms in Lapland received a total of 24.5 million EUR in state COVID-relief subsidies (Finland’s second highest amount after the metropolitan area) for developing resilience strategies (Antikainen et al., Citation2022), but this has done little so far to change the focus on recovering export-oriented tourism. Similarly, in Northern Sweden, the pandemic disrupted the operations of micro-businesses targeting international tourists, but no noticeable post-COVID pathway alterations or plans for industry transformations have occurred since. Micro-sized firms in Västerbotten’s inland managed to get through the crisis relatively well, as many small owner-managers and part-time business owners could rely on other livelihoods without the need for external financial aid. In addition, the absence of large loan payment obligations provided entrepreneurs the freedom to temporarily shut down their companies. Others handled the crisis by targeting the traditionally strong domestic and regional markets. As observed by Bækkelund (Citation2021), the global pandemic has had relatively little impact on triggering strategic changes in destination pathways through redirecting public funding towards new development priorities. With respect to the effects of regional development funding as active bifurcation points, the interviewees could not pinpoint any concrete moments where radical changes in pathways were set in motion.

Discussion and conclusions

This study adopted a conceptual framework consisting of path plasticity, moments of change, and uneven development derived from GPE to examine the role of structural development funding in shaping destination pathways, both as an active policy instrument triggering change and a reactive response mitigating disruptive moments. The underlying premise of this viewpoint is that institutions mediate between structure and agency and thereby set the context in which actors develop destination paths.

In response to our first research question seeking to illuminate the path-making propensity of funding, the findings suggest that public investments in a destination’s common infrastructure are crucial for consolidative tourism development in NSPAs (Antikainen et al., Citation2022) but public tourism projects often fail to stimulate noticeable pathway changes due to their temporal limitations restricting long-term destination planning. The absence of lasting impacts is also attributed to the institutional isolation of implementing organizations and their inability to establish functional business networks and private sector buy-ins that continue the project work without reliance on public funding (Prokkola, Citation2011). Indeed, results suggest that commercial networks to extra-regional actors are a prerequisite for successful path extension. The prescriptive nature of EU, national, and regional policies and funding requirements also risks project theme isomorphism, limiting visions for pathways beyond conservative development. A corollary of the necessity to minimize chancy expenditures and to generate fast returns on investments are uneven opportunity spaces if established powerholders, who already possess financial and knowledge capital, are favoured over newcomers.

This same pattern evidences also regarding firm funding in Lapland, where financial support is exclusively given to export- and growth-oriented companies, predominantly located in the traditional tourism hotspots. Funding allocations have mainly reinforced these clusters without spilling much into the hinterland until recently and overall, funding seems to bolster particularly replicative entrepreneurship within the framework of Arctification. As such, the goal is to strengthen a strongly growing and export-focused tourism sector that can absorb capital and labour and contributes to regional economic growth also through the multiplier effect. In the long run, this funding strategy might amplify uneven development rather than mitigate it. Fostering a tourism industry of scale makes the sector volatile to market shocks and crises, as experienced during the pandemic in Finland where the larger and export-oriented tourism firms relied on state bailouts and ad-hoc rescue packages (Antikainen et al., Citation2022). Business as usual, based on the same pre-Corona tourism pathways, resumed as soon as the COVID-19 travel restrictions were lifted. In turn, the more redistributive and social democratic approach in Northern Sweden nurtures slow and incremental firm formation, especially in the economically lagging inland areas. Small-scale tourism entrepreneurs in Northern Sweden with a domestic customer base and a foothold in other livelihoods, demonstrated a greater business resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional development funding in NSPAs should therefore not just focus on diversifying the regional economy but on promoting firms’ branching into other business activities. Such organic development strategies help to spur local pathways that are able to better cope with shocks impeding international tourist flows.

Answering our second research question, dealing with the relation of funding to trigger events and moments of change, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that ERDF and national regional development funds for firms are not designed as immediate response tools to disruptive moments due the bureaucratic nature of these instruments. Moreover, public funding is rather reactive to disruptive events than an active agent for triggering change in destination pathways. In addition to its bureaucratic inertia, funding displays a general lock-in into the forces of contemporary capitalism tied to growth-based thinking (more strongly in Lapland than in Northern Sweden) and global market forces (Harvey, Citation2020). Arctification in Nordic tourism illustrates the key aspect of such a pathway well. This form of narrow thematic touristic production (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022) risks that creativity and innovation are channelled in such a way that tourism agents become creative ‘in the same direction’ and path consolidation might turn into dependence. Berard-Chenu et al. (Citation2022) share a similar observation in the case of snowmaking deployment in the ski tourism industry where overspecialization in an industry niche may prompt short-term capital accumulation but jeopardizes long-term sustainable regional development, including diversification and branching of path.

Regarding our third research question, addressing funding approaches in relation to uneven development, the analysis revealed that Northern Sweden and Lapland pursue different strategies for firm financing. These diverging approaches are (partly) shaped by the economic and institutional histories of Finland and Sweden and persist even though both countries are EU member states. Access to funding generates opportunity spaces that are formed by organizational culture and the respective economic reasoning of political bodies and the administration. In our case, funding for firms in Lapland seeks development of scale and fast returns on public investments. Uneven development occurs with respect to prioritizing only export-oriented businesses and oftentimes already well-established actors. In Northern Sweden, smaller regional grants support the organic growth of a wider variety of tourism firms, particularly in the inland, while larger national grants facilitate the creation of export-oriented tourist enterprises with a focus on international competition. Whether this will result in similar uneven hotspot-periphery dynamics remains to be seen.

Overall, GPE conceptualizations underscore that trigger events and moments of change in destination development always occur in and are mediated by institutional contexts and landscapes of contemporary capitalism (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). It is therefore difficult to isolate these bifurcation points at the local level from wider capitalist accumulation rationalities and global market dynamics that inform institutional practices if the goal is to explain the emergence of a particular economic pathway. In this study, a GPE lens proved useful with respect to illustrating that a destination ‘pathway’ is not simply a metaphor in the vocabulary of EEG but inscribed into the material geography of regions and holds impacts on future development trajectories. This perspective also revealed that these geographical-economic patters emerge out of the administration’s political reasoning on what regional development should look like and how it is supported by public funding (Ladner & Sagner, Citation2022). Further tourism research with GPE and EEG underpinnings could delve deeper into the financial geographies of tourism pathway evolution and the evaluation of sustainability issues surrounding different destination development strategies, particularly regarding slow and incremental development versus fast export-oriented growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dorothee Bohn

Dorothee Bohn is a PhD candidate in human geography at Umeå University, Sweden. In addition to political economy analyses of tourism development and governance, her research interests revolve around financial geography, policy evaluation and human-nature interactions.

Doris A. Carson

Doris A. Carson is a researcher and docent in human geography at Umeå University in Sweden. Her research focuses on understanding tourism development pathways in remote and sparsely populated areas, as well as the role of tourism mobilities in facilitating economic and demographic change in small village settlements.

O. Cenk Demiroglu

O. Cenk Demiroglu is a researcher at the Department of Geography and the Arctic Centre at Umeå University. His research is mainly focused on the interrelationships of climate change and ski tourism. Besides, he has served as an expert to several destination development projects and teaches courses on tourism and geographical information systems.

Linda Lundmark

Linda Lundmark is an associate professor (Docent) at the Department of Geography, Umeå University, Sweden. Her main research interests are within the topics of tourism, mobility and migration, climate change, and natural resources as part of contemporary and future development prospects in the rural and sparsely populated Arctic.

References

- Antikainen, J., Heikkinen, B., Nyman, J., Rannanpää, S., Hakkarainen, M., & Harju-Myllyaho, A. (2022). Julkinen tuki matkailuhankkeisiin Suomessa 2014–2020. Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriön julkaisuja 2022:7. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-327-614-7

- Anton Clavé, S., & Wilson, J. (2017). The evolution of coastal tourism destinations: A path plasticity perspective on tourism urbanisation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177063

- Almstedt, A., Lundmark, L., & Pettersson, Ö. (2016). Public spending on rural tourism in Sweden. Fennia, 194(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.11143/46265

- Benner, M. (2022). Revisiting path-as-process: Agency in a discontinuity-development model. European Planning Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2061309

- Berard-Chenu, L., François, H., Morin, S., & George, E. (2022). The deployment of snowmaking in the French ski tourism industry: A path development approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2151876

- Bohn, D., & Varnajot, A. (2021). A geopolitical outlook on Arctification in Northern Europe: Insights from tourism, regional branding, and higher education institutions. In L. Heininen, H. Exner-Pirot & J. Barnes (Eds.), The Arctic Yearbook 2021. Defining and mapping the Arctic. Sovereignties, policies and perceptions. https://arcticyearbook.com/

- Brouder, P. (2017). Evolutionary economic geography: Reflections from a sustainable tourism perspective. Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2016.1274774

- Brouder, P., Clavé, S. A., Gill, A., & Ioannides, D. (Eds.) (2017). Tourism destination evolution. Routledge.

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. H. (2013). Tourism evolution: On the synergies of tourism studies and evolutionary economic geography. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.001

- Byström, J. (2019). Tourism development in resource peripheries. Conflicting and unifying spaces in northern Sweden. Umeå University.

- Bækkelund, N. G. (2021). Change agency and reproductive agency in the course of industrial path evolution. Regional Studies, 55(4), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291

- Carson, D. A., & Carson, D. B. (2017). Path dependence in remote area tourism development: why institutional legacies matter. In P. Brouder, S.A. Clavé, A. Gill & D. Ioannides (Eds). Tourism Destination Evolution (pp. 103–122). Routledge.

- Eura2007. (n.d.). Structural fund information service ERDF and ESF projects in Finland during the 2007–2013 programme period.

- Eura2014. (n.d.). Structural fund information service ERDF and ESF projects in Finland during the 2014–2020 programme period. Retrieved from: https://www.eura2014.fi/rrtiepa/?lang=en

- Europaforum Norra Sverige (2017). Added value of the EU Cohesion Policy in Northern Sweden. http://www.europaforum.nu/wpcontent/uploads/2018/01/added-value-of-the-eu-cohesion-policy-in-northern-sweden.pdf

- Giordano, B. (2017). Exploring the role of the ERDF in regions with specific geographical features: Islands, mountainous and sparsely populated areas. Regional Studies, 51(6), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1197387

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2014). Mindful deviation in creating a governance path towards sustainability in resort destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925964

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Halkier, H. (2010). EU and tourism development: Bark or bite? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903561952

- Halkier, H., & Therkelsen, A. (2013). Exploring tourism destination path plasticity: The case of coastal tourism in North Jutland, Denmark. Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 57(1–2), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2013.0004

- Harvey, D. (2020). The anti-capitalist chronicles. Pluto Press.

- James, L., & Halkier, H. (2016). Regional development platforms and related variety: Exploring the changing practices of food tourism in North Jutland, Denmark. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), 831–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414557293

- Kauppila, P. (2011). Cores and peripheries in a northern periphery: A case study in Finland. Fennia, 189(1), 20–31.

- Keep.eu. (n.d.). Projects and documents. https://keep.eu/projects/

- Ladner, A., & Sagner, F. (Eds.) (2022). Handbook on the politics of public administration. Edward Elgar.

- Lidström, A. (2020). Subnational Sweden, the national state and the EU. Regional & Federal Studies, 30(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1500907

- Lundmark, L., & Carson, D. A., et al. (2020). Who travels to the north? Challenges and opportunities for tourism. In L. Lundmark (Eds.), Dipping in to the north: Living, working and travelling in sparsely populated areas (pp. 265–284). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lundmark, L., Müller, D. K., Bohn, D., et al. (2020). Arctification and the paradox of overtourism in sparsely populated areas. In L. Lundmark (Eds.), Dipping in to the north: Living, working and travelling in sparsely populated areas (pp. 349–372). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ma, M., & Hassink, R. (2014). Path dependence and tourism area development: The case of Guilin. China. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 580–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925966

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R. (2009). Roepke lecture in economic geography—Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Mellon, V., & Bramwell, B. (2018). The temporal evolution of tourism institutions. Annals of Tourism Research, 69, 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.12.008

- Müller, D. K., & Jansson, B. (2007). The difficult business of making pleasure peripheries prosperous: Perspectives on space, place and environment. In D. K. Müller & B. Jansson (Eds.), Tourism in peripheries. Perspectives from the far north and south (pp.3–18). CABI.

- Pike, A., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Dawley, S., & McMaster, R. (2016). Doing evolution in economic geography. Economic Geography, 92(2), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1108830

- Prokkola, E. K. (2011). Regionalization, tourism development and partnership: The European Union’s North Calotte Sub-programme of INTERREG III A North. Tourism Geographies, 13(4), 507–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.570371

- Rantala, O., Hallikainen, V., Ilola, H., & Tuulentie, S. (2018). The softening of adventure tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522725

- Region Västerbotten. (2021). Sammanställning 2021 - beviljade företagsstöd, stöd till kommersiell service och projektmedel. https://www.regionvasterbotten.se/VLL/Filer/Sammansta%CC%88llning%202021%20%20-%20beviljade%20fo%CC%88retagssto%CC%88d%20sto%CC%88d%20till%20kommersiell%20service%20och%20projektmedel.pdf

- Riksbank. (n.d). Search interest & exchange rates. https://www.riksbank.se/en-gb/statistics/search-interest–exchange-rates/?g130-SEKEURPMI=on&from=13%2F02%2F2006&to=13%2F03%2F2023&f=Year&c=cAverage&s=Comma

- Romão, J. (2020). Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102995

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C., Wilson, J., & Anton Clavé, S. (2017). Moments as catalysts for change in tourism destinations’ evolutionary paths. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, and D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 81–102), Routledge.

- Shepherd, J., & Ioannides, D. (2020). Useful funds, disappointing framework: Tourism stakeholder experiences of INTERREG. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 20(5), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1792339

- Sheppard, E. (2011). Geographical political economy. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(2), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq049

- Finland, S. (n.d). Consumer price index. https://pxdata.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__khi/statfin_khi_pxt_11xg.px/

- Statistics Finland. (2022). Yearly nights spent and arrivals by country of residence, 1995–2022. https://pxweb2.stat.fi/PxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__matk/statfin_matk_pxt_11j1.px/

- Stihl, L. (2022). Challenging the set mining path: Agency and diversification in the case of Kiruna. The Extractive Industries and Society, 11, 101064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101064

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Strambach, S. (2010). Path dependence and path plasticity. The co-evolution of institutions and innovation. The German customized business software industry. In R.A. Boschma & R.L. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 406–431). Edward Elgar.

- Strambach, S., & Halkier, H. (2013). Editorial. Reconceptualizing change. Path Dependency, Path Plasticity and Knowledge Combination, 57(1–2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2013.0001

- Statistics Sweden. (2023). CPI. https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/prices-and-consumption/consumer-price-index/consumer-price-index-cpi/pong/tables-and-graphs/consumer-price-index-cpi/cpi-fixed-index-numbers-1980100/

- Sjöblom, S. (2009). Administrative short-termism—A non-issue in environmental and regional governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 11(3), 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080903033747

- Tillväxtverket. (n.d.). Projektbank. https://projektbank.tillvaxtverket.se/projektbanken2020#page=abe6e0ba-8cac-43ae-9022-9d34560cf5b6

- Tillväxtverket. (2022). Turismstatistik. https://tillvaxtdata.tillvaxtverket.se/statistikportal#page=72b01aa0-1d4a-425c-8684-dbce0319b39e

- Tirado Ballesteros, J. G., & Hernández Hernández, M. (2017). Assessing the impact of EU rural development programs on tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2016.1192059

- Varnajot, A., & Saarinen, J. (2022). Emerging post-Arctic tourism in the age of Anthropocene: Case Finnish Lapland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2022.2134204

- Viken. A., & Müller, D.K. (Eds.). (2017). Tourism and indigeneity in the Arctic. Channel View Publications.