Abstract

This study addresses the gap opened up by the increasing attention in evolutionary economic geography (EEG) studies on the role of the state in economic path creation. The study links the path creation notion of trigger events with political economy perspectives to investigate the role of the state in destination emergence. We offer insights into understanding how the state utilises trigger events for new path development through the case study of Unity Park in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A qualitative research approach is adopted that involves key informant interviews, analysis of policy documents and observations. The findings reveal that the idea formation for this destination developed along incremental changes in public policies until a state official seized a political transition event as an opportunity to cause a decisive shift in its trajectory. This incident triggered more real-time opportunities for the state to influence the development of this tourism destination through the application of power and agentic processes. Thus conceptually, we found that while public policies shape destination development visions, it often takes trigger events and strong state involvement to broker new destination pathways. The study contributes to broadening the current understanding of the state’s role in path creation and the significance of trigger events as well as offering empirical evidence on the political-economic mechanisms involved in destination development processes.

Introduction

At the heart of much of tourism geography research is the question of how regional tourism economies emerge and grow over time (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013; Brouder, Citation2014). Destinations do not emerge in a vacuum but are the result of complex processes leading to attractive economic novelty over time (Brouder & Ioannides, Citation2014). Evolutionary Economic Geography (EEG) has offered a framework for exploring the drivers of change in this process. Notwithstanding the progress made in understanding change agents in a new path development, there are significant research gaps such as the role of political events in transforming state intervention for destination emergence. Existing tourism path creation concepts have so far largely drawn upon insights from the Global North such as British Columbia, Canada (Gill & Williams, Citation2011, Citation2014), Niagara Region, Canada (Brouder & Fullerton, Citation2015), Fryslân Province, Netherlands (Meekes et al., Citation2017) and Denmark (Halkier & James, Citation2017) where the occurrence of certain events are treated as path shaping moments that effect a stable and subtle incremental change to an already established destination (Halkier & Therkelsen, Citation2013; Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017). Thus, the question of how specific political transition moments trigger actors, particularly the state, to bring radical changes to the development of an entirely new destination path remains unanswered. It is this lacuna that serves as the objective of this paper.

More and more EEG studies recently have begun to focus on the state as vital agent of change in destination path development (Halkier et al., Citation2019; Deng et al., Citation2021). However, studies that have explicitly investigated how the state seizes a political transition event to drive the emergence of a tourist destination are almost non-existent. The issue is a lack of empirical studies especially on regions where the state is still a significant actor in economic restructuring processes amidst recurring turbulent political events (Breul & Pruß, Citation2022; Adu-Ampong, Citation2017). On the theoretical level, the role of political transitions as triggers in path creation is less understood in current EEG theorization. In addressing this gap, this study complements earlier calls on unpacking the ‘role of power and politics in structuring economic adaption’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009: 139) which can be fully captured through combining EEG with a political economy perspective (Brouder & Ioannides, Citation2014; Hassink et al., Citation2014).

This paper aims to contribute to ongoing debates of expanding EEG theorization by focusing on the role and significance of political transition events in triggering radical change in state intervention for a new destination path. Drawing on a path creation lens focused on trigger events, together with insights from political economy perspective we follow the processes leading to the emergence of a new regional tourism economy on Unity Park in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as a case study. Our study makes three main contributions to the extant literature. First, the conceptual finding shows how trigger events are decisive in reinforcing state intervention mechanisms for the emergence of a tourism destination. Second, we make a contribution to the conceptual enrichment of EEG by offering empirical evidence on destination development process through a case in an understudied region of the Global South. Third, by focusing specifically on a political transition moment, we offer a better account of everyday state politics and power for new path creation processes in tourism (Ioannides et al., Citation2014).

The rest of the manuscript is structured as follows: after this introduction, we review the literature on path creation in EEG with a particular focus on triggering events as an analytical framework followed by a political economy perspective on state power. Next, we present our case study and methods before the sections on our findings and discussion. We then conclude the paper by highlighting the contribution of our study to tourism EEG studies.

Path creation and EEG in tourism

Path creation is a central paradigm in EEG that has been widely applied to understand evolutionary changes of regions and industries (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). The framework is developed as a critique to EEG’s path dependence model which has a constraining view on trigger events as forces of economic change (Martin, Citation2010; Garud et al., Citation2010). Social actors are seen as passive observers in path dependence with little or no power to influence events as they actually unfold (Taylor et al., Citation2019). But, path creation pays a concerted effort to the role of human agency and the ability of actors taking advantage of events that potentially lead to the formation of a new path. From this perspective, the occurrence of unexpected events is seen as real-time opportunity for entrepreneurs to unleash a new economic initiative (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). This way of theorizing a path development is increasingly gaining traction in tourism geography research as it offers among others, the explanatory power to understand the forces of transformation and change in the emergence of a destination economy (Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2019).

Following Binz et al. (Citation2016), path creation is operationalized as containing a set of functionally related firms and institutions that are established and experiences an early stages of growth. Even though tourism EEG studies (e.g. Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017) have argued that new destination paths can spring out either from the adoption of long-term incremental and adaptation processes or trigger events, research on how the specific occurrence of events catalyze a radically new path is relatively rare in the field. This is confirmed by Butler (Citation2014: 218) who claimed that triggers represent ‘a major area that has not been dealt with to any extent’ in tourism research. An exception is the recent work by Sanz-Ibáñez et al. (Citation2017) who in the context of the Costa Daurada region in Catalonia, Spain introduced the concept of moments to investigate path-shaping inflection points that forced destination paths to shift direction over time. They however focus on a more mature destination and hence there is great value in the possibility of identifying and anticipating events which might act as triggers to orchestrate change in growth paths in different context of emerging destinations (Butler, Citation2014).

Trigger events can be seen as unexpected shocks, such as a political change, natural or humanmade disasters and economic downturns, that induce a new course of action for the development of new path through the strategic actions of actors. Such events are different from longer-term processes of path creation mechanisms in that they disrupt existing systems from their steady-state condition which finally create windows of opportunities for actors to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Russell & Faulkner, Citation2004; Battilana et al., Citation2009). As events occur, actors may intervene to shape unfolding processes of an economic path through the exercise of their conscious agency in real-time (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Hence, agency is a key element of trigger events which has temporal dimensions. As Steen (Citation2016) notes, agency is a temporally embedded process where the past, the present and the future are constituted together to stimulate actions in real-time. To capture this dimension, Garud et al. (Citation2010) underlined the significance of understanding actors’ aspirations of the future, sensemaking of the past, and conceptualizations of what is transpiring in the present.

Nevertheless, not all agents and social groups have the same capabilities and power to act and effect change on a destination path (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). Consequently, taking advantage of trigger events to stimulate a change will partly depend on the socio-political position and interests of certain influential groups who are better placed to mobilize path creation resources (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). As such, this paper suggests that, besides unequal opportunities for agency, event-centered path creation processes can be influenced by power relations and (political) authority. The impact of power and political authority directs attention to the role of the state since these are typically considered as its legitimate resources (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). A deeper understanding of power relations in event provoked path creation therefore needs to ‘examine the strategic decisions made by policy-makers, including the nation-state’ (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006: 426). The following section turns to this issue in more detail.

The political economy of state power in path creation

A political economy approach is adopted to disentangle the power and influence of the state as it seeks to engage or enrol other actors in destination development process (Ioannides & Brouder, Citation2017). The term political economy broadly refers to how politics affects the economy and how the economy affects politics. In this research it has been narrowly defined as a concept with an explicit concern of the state and its power structures in shaping the process and direction of economic changes (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015). While this concept have been integrated into recent EEG studies to deal with the state’s role, much of the debate is centred on long-term policy and investment interventions (Dawley, Citation2014; Dawley et al., Citation2015; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019; Hassink et al., Citation2019). Yet the instruments of the state in path development are not confined to policy interventions and financial instruments. The state can also exert power directly although this has not been given much attention in the current literature with the exception of few prescriptive works (Hassink et al., Citation2014). We argue this is mainly due to the geographical focus of extant studies on industrialized countries of Europe (Sanz-Ibáñez et al., Citation2017; Meekes et al., Citation2017) and North America (Gill & Williams, Citation2011, Citation2014; Brouder & Fullerton, Citation2015) where the overt role of the state is limited.

The state is used here in reference to mainly the national government, particularly in the context of Ethiopia, which is in control of and orchestrate the mechanisms for overall national development including the emergence of tourism destination paths. One of the core ideas of political economy is the strategic allocation and coupling of resources, thereby creating winners and losers as existing arrangements are moulded to adapt a certain economic path (Bianchi, Citation2018; Britton, Citation1982). This raises questions of power relations in terms of the ability of such actors who have more influence over others to mobilize resources to establish a path and construct rational for its promotion (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). In this respect, for example, Bramwell (Citation2011) contends that political structures and authority provide governments with a leverage to exercise much power than any non-state actors. This is specifically true in some regions of the Global South where the state is powerful and a primary influence in restructuring the evolution of the economic landscape (Routley, Citation2014). Often discussed under the notion of developmental state (Wade, Citation2018), state power in this geographic context has brought the successful development of new economic pathways (Breul & Pruß, Citation2022). The state itself does not exercise power; it is rather politicians and state officials who activate the state’s powers (Jessop, Citation2010). This exercise of power can be manifested through different modes of application such as authority, coercion, charisma, leadership and persuasion (Hassink et al., Citation2014). Jessop (Citation2010) argues that state actors exercise these powers at a particular time and conjuncture to achieve their goals. The timing of when state personnel select a specific circumstance or event as an opportunity to apply state powers has a significant implication for trigger events (Bramwell, Citation2011). Thus, a key question for research on destination path development would be to analyze the decisions and motivations of powerful state personnel in response to certain critical events (Brouder et al., Citation2017).

Overall, we claim that a broad engagement with politics in EEG can provide the potential to closely understand the identity of key individuals and the power relations that underpin event-led path creation processes.

Case study and method

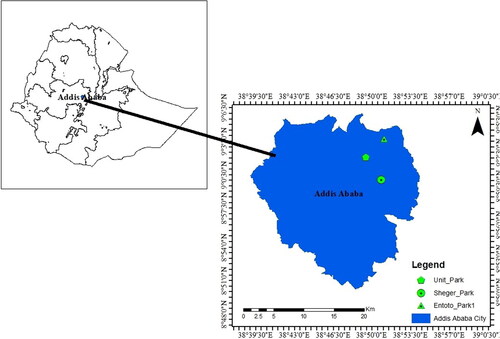

The tourism sector in Ethiopia has long been positioned as a marginal sector despite its recognition as a significant economic activity going back to early 1960s. Over the years, due attention had been invariably given to other economic activities, such as agriculture, as the key engine of development (Ethiopian Economic Association, 2004/5). In the last couple of years, however, as new paths to support the national economy were sought, tourism emerged as an important area that can be integrated into the country’s development priorities (National Planning Commission, Citation2016). Tourism holds a significant position in current socio-economic reforms with ambitious targets set to build a sustainable and competitive tourism market (Gebeyaw & Lovelock, Citation2019). This is further supplemented by extensive destination development projects with the direct involvement of the national government that came to power in 2018. After years of lock-in situations, the current government has been able to open three destinations for the public since 2019, namely: Unity Park, Entoto Park and Sheger Park (). These destinations are part of a megaproject called Beautifying Sheger that intends to bolster urban tourism in the capital Addis Ababa (Biruk, Citation2020).

Unity Park attracts the attention of this study for three reasons: first, the destination’s locational context has a conceptual relevance for path creation. In the past, the exact location of this site was a highly guarded Imperial Palace and a strictly prohibited ‘no photography zone’ with no access to the public. Thus, path creation concepts of agency and power offer a lens to interrogate the intentional transformation of this place from ‘a no photography zone’ to a tourism space for the public. Second, the case exemplifies the phenomenon of state intervention (Deng et al., Citation2021). Previous studies show that breaking lock-in situations to include tourism into the economy of an area can never be a linear process as it usually requires new capabilities and adjustments (Brouder & Eriksson, Citation2013). As economies in some regions continue (re)structuring processes to include tourism, the question of how and why this happens is important (Halkier & James, Citation2017). As mentioned earlier, it is the national government who took the lead in instigating and realizing this destination. The government was involved in developing project plan, mobilizing funds, providing land for investors, offering tax relief and exemption, and creating networks between firms and convincing the private sector to invest. The third reason relates to case reputation. Three years on from its opening, this destination is now seen as a success especially in motivating the country’s domestic tourism by the state.

In order to achieve the aim of the study, a qualitative case study design is applied involving document analysis, interviews and observations. Steen (Citation2016) argues that qualitative methods in EEG studies has potential in providing new insights given the complex processes involved in path creation. The case study analysis allows a deeper understanding of how the destination emerged and the mechanisms that drive the creation of this tourism product (Binz et al., Citation2016) at a time of political transition in the country. In terms of data collection, a number of national level policies and plans from the immediate previous government were collected based on their relevance for the research question (). These documents were mainly used to get a detailed account of the policy process and the degree of state involvement in the pre-trigger event period. This clearly laid the background context for state intervention before its eventual transformation following a change in the political landscape.

Table 1. Analyzed national level policy documents and their source organization.

In addition, a total of thirteen in-depth semi-structured interviews that sought to capture the changing role of the government following the 2018 political transition were conducted with informants between February-April 2021 (). Emphasis was given to identify reasons why this specific moment dislodged the state from its previous steady-state form in pursuit of a more active role. The informants were selected purposefully from both public and private sectors based on their direct involvement in the process. The limited involvement from non-Ethiopian actors in the project led the interview to focus more on domestic actors that had a dominant role. Two separate interview guides, one for government representatives and the other for the private sector, were prepared in English and later translated into Amharic which is the local language used in the interview session. On one hand, the interview guide for government representatives focused on the actions taken by state officials (specifically by the Prime Minister), how these actions differ from those undertaken in the previous regime, how the state approached other involved actors and the impact of the political change in triggering a strong state involvement. On the other hand, the interview questions for private institutions mainly explored the process of how and why actors joined the project (particularly following the political change), their relation with state personnel at the time of construction and contribution in the project. All the interviews were carried out by the first author at the place of work of interviewees with duration of 35–55 min. Twelve of the interviews were face-to-face with one being a telephone interview. It is worth noting the possibility that interviewees (mainly from nonstate actors) may have felt restricted in what they are able to share during the interviews given the nature of the topic.

Table 2. Composition of interviewees.

Content analysis was used for the policy documents in order to extract relevant data and examine in-depth how the changing contexts in policies paved the way to the current destination path. Thematic analysis following the six-step outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) was used for the interviews through: becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and finally producing the report. First, the eleven interviews for which consent was given to be recorded was transcribed in Amharic before translation into English by the first author who is a native speaker. During transcription and translation, an overview of the range and diversity of the data was examined. The data from both the policy documents and interviews was coded, and while some of the codes were developed based on concept exploration (a priori), others were in-vivo codes that emerged out from the actual data. The analysis from policy documents is used to trace the background context of destination development plans while interview data helped to explain the real-time scenario and fresh developments following the trigger event.

Research findings

This section presents the findings of the study structured around two main themes. In so doing, it shows where the conception of this particular destination originally comes from and the subsequent political event that sparked massive changes in the path creation process.

From lock-in to path creation in destination development

The emergence of Unity Park has a strong relation with policy visions and claims made by the previous regime as an effort to create new economic opportunities in the country. Although the 1993 long-term Agricultural Development-Led Industrialization (ADLI) strategy had less emphasis on the development of tourism, towards the early 2000s the pressure to diversify the economic base began to build on the government by donor organizations, policy advisors and academics (Cramer et al., Citation2004; Mitchell & Font, Citation2017). This led to a gradual shift in policy discourses recognizing the need for broadening the economy towards tourism. Hence, the Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction Program (2002/03–2004/05) which was formulated thereafter as a medium-term plan underlined that ‘it is not possible to ensure accelerated growth and sustainable development’ unless the service sector, where tourism is a part, grows in conjunction with other areas of the economy (MoFED, 2002: iii). Later, the Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (2005/06–2009/10) made clearer the government’s intention to achieve a ‘step-change’ in the tourism industry by assuming a key gap-filling role due to the private sector’s formative stage of development (MoFED, 2006). Moreover, the development of new destinations had been explicitly included as a priority area of the tourism sector. As a result, the plan noted that ‘the state will both initiate and encourage selected imaginative projects that accelerate growth in the [tourism] sector’ (MoFED, 2006: 144). This plan identified Addis Ababa as an area where new destination development projects need to be carried out.

In November 2010, the government adopted the Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP I) (2010/11–2014/15) to carry forward the important strategic directions pursued in the previous years. By emphasizing on the socio-economic and political significance of tourism, the GTP I aimed to develop new products and services in terms of both quality and quantity. Above all, this plan created a relative sense of urgency for the government to be involved in tourism development programs. As a matter of sectoral priority, the government was urged to go beyond policy rhetoric and to practically engage in the development of new destinations. This offered an opportunity to break from the lock-in situation of old paths of governmental ambivalence in destination development. In the second year of the plan period, an initiative arose from the government to open a portion of the Imperial Palace for tourism. A former government official explained that:

A project aimed at renovating our national palaces for tourism had already been launched when I came to office in 2012. The project had phases where the National Palace, the Grand Palace [where Unity Park is located] and the Palace of Emperor Yohanes at Mekele constituted its first phase. It then took us seven years to restore the cultural heritages that are found in today’s Unity Park. (Interview with Unity Park administration 2, April, 2021)

Political transition as a defining trigger moment

After three years of political crisis in the country that resulted in inertia in many development projects, a new government came to power in April 2018 (Amare, Citation2020) with renewed intervention strategies. This transfer of political power from one set of state officials to another represents the defining trigger event for the following reasons. First, for the first time in national economic history, tourism is identified as a development priority area in the new government’s Homegrown Economic Reform Agenda (Plan & Development Commission, Citation2021). Second, the political transition brought a particular individual into the prime minister position whose role was instrumental in the development, expansion and eventual opening of the destination in its current form. In the old plan by the previous regime, the destination product was limited to the mere restoration of existing heritage resources. But, a new plan introduced in early 2019 were in accordance with the personal and political preferences of the Prime Minister and included the modification and expansion of the recreational destination products. The Prime Minister using his political position created a much needed momentum in mobilizing financial and material support from a coalition of actors. He primarily secured the required finance of about US$170 million from the United Arab Emirates to realize this project. Subsequently, the government made an open call to the private sector as an invitation to participate in the construction of the park. Although a number of private organizations accepted this call, only few of them were selected by the Prime Minister based on their record of excellence in their areas of specialization and their proven capacity for project delivery. Public institutions were also recruited mainly to help the state overcome higher financial expenditure that would be incurred if the entire project was given to a private enterprise (Interview with Unity Park administration 1, April, 2021). This direct engagement of the Prime Minister eventually gave the project publicity and due government attention priority than previously (Interview with Unity Park administration 2, April, 2021).

Besides economic diversification, the Prime Minister’s motives in the development of this destination area was driven by political considerations. In the past, government-led projects were often considered as dead at birth because of the number of uncompleted projects. Having just assumed office after a political turmoil, there was a political imperative for him to complete projects on time to show the new government as a break from past legacies of inefficiencies (Interview with Unity Park administration 1, April, 2021). Thus, although a project leader with direct reporting line to the Prime Minister was assigned to oversee day-to-day operations, the Prime Minister himself was active in project supervision. An interviewee from public construction enterprises revealed that ‘…besides the project leader, the Prime Minister often came to see our progress. Even our immediate bosses who had no any previous experience of visiting a project supervised this work closely’ (Interview with Public Construction Enterprise 1, February, 2021). Aside from his supervisory role, the Prime Minister was a significant player in creating a network of actors most of whom he personally contacted either at their place of work or at his own office to persuade them to join the project. For instance, a respondent from Zoma Museum shared that:

One day the Prime Minister suddenly came to our Museum. We were not informed in advance about the visit. Then he came in and visited the museum facilities. Because he was so satisfied with the works here, he asked us to participate at Unity Park project. (Interview with Zoma Museum, February, 2021)

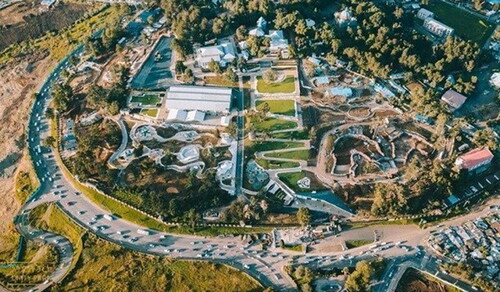

The political transition of 2018 that brought in a new Prime Minister therefore represent a key triggering moment in the rapid turn of evolution in the path creation process. In the political economy context of Ethiopia, the opening of Unity Park in October 2019 carries important political implications in that it represents the shift in path for the area that had been traditionally known as an exclusive seat of the government. Set on a 13-hectare land on the premise of the Grand Palace of Emperor Menelik II () which was built in the late 1880s (Seble & Biruk, Citation2021), this place has since been the seat of the central government and, hence a high security zone not accessible to the general public.

The Park accommodates the history of Ethiopian Emperors along with a number of buildings such as the Throne House and Banquet Hall which have enormous historical significances. In addition, it also features a state-of-the-art gallery with several installations, a zoo and children playground which are all recent additions to this historic site. Opening up this particular site to the public is therefore of significant symbolic and material importance as it speaks to the making of the state accessible to all citizens and in the process creating a new sense of shared national unity. Currently, Unity Park is considered as one of the high-profile tourist destinations in the city. In the time immediately before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the site had been attracting over 3000 visitors per day, mostly domestic tourists. Due to the growing economic significance from the destination, it only took a six months respite for the government to re-open the park even during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion: policy, power and the politics of the state in destination emergence and development

The analysis provides a relevant context within which to explore the changing role of the state in destination pathway triggered by a political incident. Public policies are one mechanism that can help orchestrate the emergence of a new path by identifying emerging opportunities (Dawley et al., Citation2015). Similarly, public policies in the current case allow the state to gradually make a break from established structures and practices by taking deliberate and conscious actions in favour of a new path (Gill & Williams, Citation2014). This is evident when the country’s policies has long stressed the importance of developing new destinations, thereby highlighting the typical feature of (policy) entrepreneurs who strive to create new paths (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). Step-by-step, these policies were operationalizing the visions and expectations of the tourism sector to be acted on by the state as a means to break lock-in situations (Steen, Citation2016). Specifically in the Growth and Transformation Plan (2010/11–2014/15) period a decisive shift was made when the Grand Palace was identified as a tourism resource to be developed. The state through this plan made a break with the past in recognizing the site as a tourism asset for creating new economic pathways in the city (Taylor et al., Citation2019). This is in line with earlier research findings on how policy actions can support destination path reorientation processes (Sanz-Ibáñez & Anton Clavé, Citation2014; Anton Clavé & Wilson, Citation2017). However, in the present case the policies go a step further to furnish the introduction of an entirely new destination. But, this finding also clearly show that the progress of policy-driven path creation was slow and lacked the capacity to deliver intended outcomes.

The April 2018 political transition therefore appeared as a significant event that created more opportunities for the state to actively intervene. This moment certainly served as a triggering event that radically shifted the state’s course of action in making Unity Park a reality. It further demonstrates the role of state power in shaping emerging situations in real-time. From a political economy perspective, the evolution of tourism policies in general and the completion of the Unity Park project in particular were strongly affected by the change in the political field (Bramwell, Citation2011). The new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, effectively used his political power to liberate the dormant path creation process of the past. As a politician, his motives were not only economic objectives as opposed to regular entrepreneurs, but also a political one that aimed to gain public acceptance through his achievement of government projects. Again politically, the opening of the park symbolizes a clear break from a closed militarised no-go zone during past political regimes. Moreover, government efforts went even further to utilize the area as a showcase to its ‘openness’ and ‘closeness’ to the general public. This reaffirms recent claims that political transitions are key explanatory variable for changes of a destination. Particularly in the Global South context, political transitions are moments of flux and possibilities open to the shaping role of the most powerful actor-usually the state- in destination development (see Seyfi & Hall, Citation2020).

In path creation, time is a resource that offers actors options to strike at the right time and right place (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). As head of government, the Prime Minister took advantage of this time to act and alter how this destination should be developed and opened to visitors. The new project plan was highly impacted by him in a way that could diversify the product offer, which would otherwise have been different without this interference. Moreover, new path development relies upon the resources generated from different distributed actors and the process needs the strategic ability of agents to mobilize a collective (Binz et al., Citation2016). Thus, the formation of key resources such as financial capital and competence is always challenging for actors driving a change (Karnøe & Garud, Citation2012). In Unity Park’s case, the state widely utilized various forms of power such as charisma, soft coercion, persuasion and leadership to mobilize actors in contributing resources for the development of the destination. By using the Prime Minister’s persuasive interpersonal skills and political authority, the state was able to draw finance from a foreign country, and skills mainly from a network of domestic actors—some of whom may have had unvoiced reservations in participating. This indicates that besides agency, path creation in time of trigger events is influenced by power relations, a finding also confirmed by Kulusjärvi (Citation2017).

Furthermore, state power as exercised by the Prime Minister helped to generate a momentum among involved actors who were committed to satisfy his interests. This commitment in turn made these actors to rally their resources in support of current state actions, taking into account their future aspirations in terms of exploiting the tourism potential of the country. This action of the actors is consistent with previous findings on construction of temporal agency in path creation (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020; Steen, Citation2016). While these collective agency supports Garud and Karnøe (Citation2001) observation that the emergence of a path cannot be attributed to any one individual actor, the intervention especially from the Prime Minister also highlights the influential role of an individual in leadership capacity that generated an irreversible impetus for the emergence of this destination (Taylor et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

The article combined the path creation concept of trigger events with political economy to better understand the role of the state in destination development. Through the case of Unity Park in Ethiopia, we contribute theoretical and empirical insights to understand in depth trigger events in EEG. Although the occurrence of events are often associated with their negative impacts (Hall, Citation2010), this study focuses on the less-researched positive sides of events in EEG as an opportunity for a new destination development. The study offers three significant insights:

Firstly, regarding early path creation processes, it depicted that policy actions can be vital in allowing the state to strategically drive changes in destination development. The state makes use of policies to self-reflect on escaping its tourism lock-in path which is an analogue to Garud and Karnøe (Citation2001) boundary spanning concept. The boundary spanning ideas for Unity Park developed incrementally through economic policies until a political transition in 2018 brought transformative change in its trajectory. In addition, our study reveals that political transition as a significant trigger event that effectively set the state towards rapid destination path creation. The findings show how the state successfully seized the 2018 political change to scale up its intervention strategies. The final insight we provide is that state power is a crucial instrument in constructing networks of actors that can generate the momentum needed to develop a break from lock-in situation onto destination path creation trajectory. The key player in this case was the Prime Minister who acted as a path creation entrepreneur and advocate (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Although his individual agency was central to create path creation momentum, the involvement of other non-state actors was also necessary to support and realize the development of the new path (Gill & Williams, Citation2017). What remains unclear is the extent of coercive force vis-a-vis free choice felt by those who make up the collective human agency through which new paths are realised.

In addition to the case-specific insights, our study adds to knowledge on EEG-inspired tourism geographies research in several ways. First, it responds to calls to unravel how power and politics underpin economic adaptation (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). Secondly, the study explores the emergence of a tourist destination in the context of a trigger event. We specifically find that the state and key political actors can emerge as powerful during a political transition event to orchestrate a new economic pathway (Dawley et al., Citation2015; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). In addition, the study made modest contributions to the inter-temporal nature of agentic processes despite this not being its primary objective (Steen, Citation2016). The actions of engaged actors in real-time was fairly stimulated by their future aspirations of the tourism sector as a potential economic activity that had not been fully utilized previously. Finally, we offer an empirical case of the emergence, evolution and changing paths of tourism destination development in less matured destinations of the Global South. The extant literature tends to overly focus on Global North destinations where policies have strong path-creation abilities. In contrast, as our case shows, Global South destinations experience slow, and often ineffective, policy-led path-creation processes. It takes the strong actions of political actors to directly liberate and establish new paths and it is this insight that highlights the geographical dimension of our contribution to EEG studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Melese Kebede Belay

Melese Kebede Belay is a former Lecturer at the Department of History and Heritage Management, Dire Dawa University, Ethiopia. He completed an MA in Tourism and Development in 2013 from Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia and most recently graduated with an MSc Tourism, Society and Environment degree from Wageningen University, the Netherlands in 2021. His research interest includes destination development, tourist experiences, and well-being in cultural events context.

Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong

Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong is an Assistant Professor in the Cultural Geography Chair Group, Wageningen University and Research, the Netherlands, and a Senior Research Associate at the School of Tourism and Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He holds a Dutch Research Council (NWO) Veni Grant (VI.Veni.201S.037) researching on the geographies of slavery heritage tourism in the Ghana-Suriname-Netherlands triangle. His other research interests are on sustainable tourism development, tourism policy and planning, and innovations in qualitative research methodologies.

References

- Adu-Ampong, E. A. (2017). State of the nation address and tourism priorities in Ghana-a contextual analysis. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(1), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1101392

- Amare, K. A. (2020). Challenges of Ethiopian transition: Breakthrough or brink of collapse? African Journal of Governance and Development, 9(2), 648–665.

- Anton Clavé, S., & Wilson, J. (2017). The evolution of coastal tourism destinations: A path plasticity perspective on tourism urbanization. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177063

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Bianchi, R. (2018). The political economy of tourism development: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.08.005

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Biruk, T. (2020). Urban layers of political rupture: The ‘new’ politics of Addis Ababa’s megaprojects. Journal of East African Studies, 14(3), 375–395.

- Bramwell, B. (2011). Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.576765

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breul, M., & Pruß, F. (2022). Applying evolutionary economic geography beyond case studies in the Global North: Regional diversification in Vietnam. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 43(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12412

- Britton, S. G. (1982). The political economy of tourism in the Third World. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(3), 331–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(82)90018-4

- Brouder, P. (2014). Evolutionary economic geography: A new path for tourism studies? Tourism Geographies, 16(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.864323

- Brouder, P., Anton Clavé, S., Gill, A., Ioannides, D., Clavé, A., & Gill, D. (2017). Why is tourism not an evolutionary science? Understanding the past, present and future of destination evolution. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Brouder, P., & Eriksson, R. (2013). Tourism evolution: On the synergies of tourism studies and evolutionary economic geography. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.07.001

- Brouder, P., & Fullerton, C. (2015). Exploring heterogeneous tourism development paths: Cascade effect or co-evolution in Niagara? Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1–2), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1014182

- Brouder, P., & Ioannides, D. (2014). Urban tourism and evolutionary economic geography: Complexity and co-evolution in contested spaces. Urban Forum, 25(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-014-9239-z

- Butler, R. (2014). Coastal tourist resorts: History, development and models. ACE: Architecture, City and Environment, 9(25), 203–228. https://doi.org/10.5821/ace.9.25.3626

- Cramer, C., Demeke, M., Geda, A., Weeks, J., Abdela, A., & Getachew, D. (2004). Concretization of ADLI and analysis of policy institutional challenges for an Ethiopian diversification strategy. Center for Development Policy and Research EPPD/MOFED.

- Dawley, S. (2014). Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography, 90(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12028

- Dawley, S., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Deng, A., Lu, J., & Zhao, Z. (2021). Rural destination revitalization in China: Applying evolutionary economic geography in tourism governance. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26(2), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1789682

- Ethiopian Economic Association. (2004/5). Report on the Ethiopian Economy. Transformation of the Ethiopian agriculture: Potentials, constraints and suggested intervention measures. Volume IV.

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2001). Path creation as a process of mindful deviation. In R. Garud & P. Karnøe (Eds.). Path dependence and creation (pp. 1–40). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., & Karnøe, P. (2010). Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x

- Gebeyaw, A., & Lovelock, B. (2019). Sustainable tourism development and food security in Ethiopia: Policy-making and planning. Tourism Planning and Development, 16(2), 142–160.

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2011). Rethinking resort growth: Understanding evolving governance strategies in Whistler, British Colombia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.558626

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2014). Mindful deviation in creating a governance path towards sustainability in resort destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925964

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2017). Contested pathways towards tourism-destination sustainability in Whistler, British Colombia. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 43–64). Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Halkier, H., & James, L. (2017). Destination dynamics, path dependency and resilience: Regaining momentum in Danish coastal tourism destinations? In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 19–42). Routledge.

- Halkier, H., Müller, D., Goncharova, N., Kiriyanova, L., Kolupanova, I., Yumatov, K., & Yakimova, N. (2019). Destination development in Western Siberia: Tourism governance and evolutionary economic geography. Tourism Geographies, 21(2), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2018.1490808

- Halkier, H., & Therkelsen, A. (2013). Exploring tourism destination path plasticity. The case of coastal tourism in North Jutland, Denmark. Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 57(1–2), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2013.0004

- Hall, M., C. (2010). Crises events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2010.491900

- Hassink, R., Klaerding, C., & Marques, P. (2014). Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Regional Studies, 48(7), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Ioannides, D., & Brouder, P. (2017). Tourism and economic geography redux: Evolutionary economic geography’s role in scholarship bridge construction. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 183–193). Routledge.

- Ioannides, D., Halkier, H., & Lew, A. (2014). Evolutionary economic geography and the economies of tourism destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 535–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.947315

- Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2017). Exogenously led and policy-supported new path development in peripheral regions: Analytical and synthetic routes. Economic Geography, 93(5), 436–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Jessop, B. (2010). Redesigning the state, reorienting state power, and rethinking the state. In K. T. Leicht & J. C. Jenkins (Eds.), Handbook of politics: State and society in global perspective (pp. 41–61). Springer.

- Karnøe, P., & Garud, R. (2012). Path creation: Co-creation of heterogeneous resources in the emergence of Danish wind turbine cluster. European Planning Studies, 20(5), 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.667923

- Kulusjärvi, O. (2017). Sustainable destination development in northern peripheries: A focus on alternative tourism paths. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 12(2/3), 41–58.

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K., & McMaster, R. (2009). Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography, 85(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R. (2010). Reopke lecture in economic geography-rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography. Regional Studies, 49(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.899431

- Meekes, J., Buda, D., & Roo, G. (2017). Adaptation, interaction and urgency: A complex evolutionary economic geography approach to leisure. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1320582

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2002). Sustainable development and poverty reduction programme (SDPRP) (2002/03-2004/05). Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2006). Ethiopia: Building progress a plan for accelerated and sustained development to end poverty (2005/2006-2009/10). Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2010). Growth and transformation plan (2010-2015). Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation.

- Ministry of Planning & Economic Development. (1993). An economic development strategy (ADLI) for Ethiopia. A comprehensive guidance & a development strategy for the future. Addis Ababa Ethiopia: Ministry of Agriculture.

- Mitchell, J., & Font, X. (2017). Evidence-based policy in Ethiopia: A diagnosis of failure. Development Southern Africa, 34(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2016.1231056

- National Planning Commission. (2016). Growth and transformation plan II (GTP II) (2015/16-2019/20). Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation.

- Plan and Development Commission. (2021). Ten-year development plan. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Planning and Development Commission.

- Routley, L. (2014). Developmental states in Africa? A review of ongoing debates and buzzwords. Development Policy Review, 32(2), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12049

- Russell, R., & Faulkner, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship, chaos and the tourism area lifecycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 556–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.008

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C., & Anton Clavé, S. (2014). The evolution of destinations: Towards an evolutionary and relational economic geography approach. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925965

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C., Wilson, J., & Anton Clavé, S. (2017). Moments as catalysts for change in the evolutionary paths of tourism destinations. In P. Brouder, S. Anton Clavé, A. Gill, & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Tourism destination evolution (pp. 81–102). Routledge.

- Seble, S., & Biruk, T. (2021). Can Addis Ababa stop its architectural gems being hidden under high-rises? Available https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/feb/10/can-addis-ababa-stop-its-architectural-gems-being-hidden-under-high-rises (Accessed on 15 March 2021)

- Seyfi, S., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Political transitions and transition events in a tourism destination. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2351

- Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: Aspects of agency, temporality and methods. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1605–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Taylor, P., Frost, W., & Laing, J. (2019). Path creation and the role of entrepreneurial actors: The case of the Otago Central Rail trail. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.06.001

- Wade, R. H. (2018). The developmental state: Dead or alive? Development and Change, 49(2), 518–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12381