Abstract

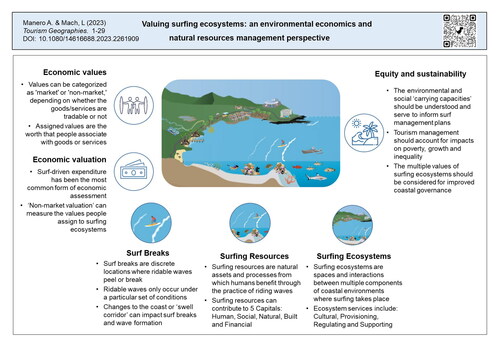

Surfing ecosystems—surf breaks and their surrounding areas—can provide multifaceted benefits, including support for tourism industries, personal and social wellbeing and shoreline protection. Previous research has predominantly concentrated on quantifying direct expenditures, sidelining non-market values, and failing to consider the interactions between multiple ecosystem components. To address these gaps, this paper provides a review of key principles of environmental economics and natural resource management in relation to surfing ecosystems. We examine how the value of surfing ecosystems can affect (and be affected by) factors related to environmental sustainability, tourism demands and economic development. We propose a novel framework for characterizing the values of surfing ecosystems and conducting economic assessments, based on six main features: (i) surf breaks, (ii) surfing resources, (iii) surfing ecosystems, (iv) economic values, (v) economic valuation, (vi) equity and sustainability. This structured approach may serve to improve decision-making processes concerning environmental changes that impact surfing ecosystems, including tourism management plans and environmental regulations. Our study aligns with broader global initiatives to better account for ocean-based values and support sustainable, nature-based tourism.

Introduction

In 2017, coastal and marine tourism accounted for a quarter of the US$1.5 trillion-dollar ocean-based resource economy, making it the fastest growing value-added segment (Brumbaugh, Citation2017). According to an estimate of international surf tourism expenditures (US$65 billion per year), surf tourism may account for as much as 17% of all coastal and marine tourism (Mach & Ponting, Citation2021). The particular coastal spaces around the world that provide the bathometric and geographical conditions for quality surf breaks tend to attract most of the visitors, capital and development, leading to significant pressures from a human geography perspective (McGregor & Wills, Citation2017). Natural surf assets have long been seen as overlooked in global discussions on coastal recreation, but several case studies have quantified values derived from surf participation and travel (e.g. Bosquetti & de Souza, Citation2019; Hodges, Citation2015; Lazarow et al., Citation2008; Mills & Cummins, Citation2015; Wright et al., Citation2014). Some of these studies are aligned with a growing effort to advocate for surf-based values to be considered in coastal planning policies, especially when competing interests emerge, e.g. construction of marina where a surf break exists (Development, Citation2022).

Several surf-specific evaluation and management frameworks exist seeking to improve management and protection of surfing resources. For example, the Surf Resource Sustainability Index (SRSI), proposed by Martin and Assenov (Citation2014) includes economic and environmental targets, as part of a suite of 27 indicators, which are ranked to obtain a composite sustainability score. The transdisciplinary framework put forward by Arroyo et al. (Citation2019) also calls for the consideration of pressures and impacts associated with socio-economics and bio-physical components of surfing ecosystems. In a more straightforward approach, Lazarow (Citation2010) offers four key strategies to manage user impact and resource base at surf locations: (1) do nothing; (2) legislate/regulate; (3) modify the resource base; and (4) educate/advocate.

Despite recent advances, we see two important questions that need to be addressed as inquiries progress into the value of surfing, both for lifestyle and tourism reasons. First, the predominant approach for the economic assessment of surf-related activities resides in the quantification of market expenditure (e.g. gear and travel), as this is generally regarded as a desirable outcome, feeding into local economies through job creation and capital growth (e.g. Mills & Cummins, Citation2015). Conversely, non-market values, such as participants’ welfare, have only been quantified by a small number of studies (e.g. Nelsen, Citation2012; Ramos et al., Citation2019; Scorse et al., Citation2015).

A second issue, is that most surf resource valuations have failed to account for the negative impacts resulting from surfing activities, occurring in a particular geographical context. For example, expanding the local tourism industry, from its natural state to support surf-related infrastructure (e.g. roads or hotels) can result in environmental degradation, the cost of which is often unaccounted for. Many researchers have criticized surf tourism for colonizing remote areas, while ushering in rapid and unplanned development (Krause, Citation2012; Ponting, Citation2009; Ruttenberg & Brosius, Citation2017). This can aggravate social and environmental issues, and even impact the integrity of surf breaks (Haro, Citation2021; Valencia et al., Citation2021) or cleanliness of the water (Mach, Citation2021; Tantamjarik, Citation2004). To our knowledge, no study has to date attempted to quantify the overall environmental and social costs associated with growing surfing pressures. Critical surf scholarship seems to discourage any use of economic tools or frameworks of analysis, while economic surf research tends to omit discussion of externalities.

This paper has two key aims: i) to provide an overview of key concepts of environmental economics and natural resource management in relation to surfing ecosystems; and ii) develop a novel framework for characterizing and measuring values associated with surfing ecosystems. The first section of this paper consists of a review of the literature, guided by seminal works, best-practice and recent advances in environmental economics and natural resource management. Frameworks discussed in this review include: ‘ecosystems services’ (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Citation2005), ‘Five Capitals’ (Viederman, Citation1994), ‘Total Economic Value’ (Segerson, Citation2017), and Non-Market-Valuation (NMV) (Freeman et al., Citation2014). The second section of the paper consists of a step-by-step framework for the systematic valuation of surfing ecosystems. We arrive to this holistic guidance by applying a surfing lens to the existing literature, with a focus on the interconnectedness and trade-offs between multiple values (Segerson, Citation2017).

Our study contributes to the broader tourism literature by generating a new conceptual framework that is at the intersection of cultural ecosystem services and placemaking (Cheer et al., Citation2022). We draw on a broad suite of case studies from global surf destinations, to examine how local and regional dynamics (e.g. social, cultural, environmental and economics) can shape and be shaped by growing demands for surf tourism. As surf travel continues to grow, including motivations towards greater ethics of care, we highlight the dichotomy faced by tourism and coastal planners in balancing financial gains and long-term sustainability. Overall, our review helps to understand the complex interactions occurring within surfing ecosystems and the broader geographies they are part of. Our framework for the valuation of surfing ecosystems can assist policymakers, planners, and businesses involved in surf tourism to make informed decisions that take into account multiple values in a holistic and adaptable way to different geographical contexts.

Beyond local management considerations, an accurate understanding of the value of surfing ecosystems, as part of complex coastal areas, is fundamental for natural capital accounting, which allows the measurement of a country’s or region’s natural resources and ecosystems in economic terms (Farrell et al., Citation2022). This ties to international efforts to better account for ocean-based values, including the United Nations 2021–2030 ‘Oceans Decade’ (United Nations, Citation2020) and Sustainable Development Goal 17, which calls for a sustainable ‘blue economy’ (United Nations, Citation2022).

Environmental economics and natural resource management through a surfing lens

Surf breaks

For the practice of surfing to occur, at a minimum, a wave is required that can be ridden. Ground swells (groups of long-period waves) form out at sea through the wind blowing into the surface of the water, but it is only when they reach shallow areas and travel over certain features (such as a sand bar, coral reef or rock formation) that waves ‘peel’ or ‘break’ (Butt & Russell, Citation2004). However, waves are not necessarily rideable everywhere they break, as this requires particular combinations of wave period, speed, peel angle and size (Thompson et al., Citation2021). For example, across California—one of the most wave-rich areas in the world—quality surfing waves only occur over a small fraction of the coastline, and at particular times of the year (Reineman, Citation2016). Thus, the discrete locations were waves break and become ridable are referred to as ‘surf breaks’ (Scarfe et al., Citation2003). To reach a surf break, ocean swells travel through large areas, seaward of the break, known as the ‘swell corridor’(Atkin & Greer, Citation2019).

Surf breaks are part of the natural infrastructure and provide recreation opportunities for a variety of sports, including surfing, stand-up paddling, body-boarding and body surfing, among others (Monteferri et al., Citation2020). Because each surf break is reliant upon a unique composition of geographical features, they attract migration and visitation from surfers seeking experiences that match their ability and preferred style (e.g. long point breaks, barreling reef and beach-breaks, and soft rolling cobblestone rock breaks) (Reineman, Citation2016). Any changes occurring along the coast or within the swell corridor can affect the frequency, quality or consistency of the waves, which, in turn, may impact the appeal and desirability of the surf location (Hume et al., Citation2019).

Surfing resources

Natural resources are the assets (stocks and flows) that are naturally occurring in the environment and from which humans benefit, either directly or through few modifications (Graham et al., Citation2017; Keith et al., Citation2017). Common examples include water, minerals, fuels or food. More recently, ‘surfing resources’ have been defined as surf breaks and the associated physical processes that enable the practice of the sport (Atkin et al., Citation2019; Scorse & Hodges, Citation2017).

A well-established framework for accounting for natural resources is the ‘Five Capitals’ model, which conceptualizes ‘capital’ as all forms of wealth and resources, which are interconnected and categorized in five forms: human, natural, socio-cultural, financial and built (Viederman, Citation1994). The ‘Five Capitals’ framework has been criticized for being excessively human-centric, with a focus on providing environmental goods and services to people (Clark, Citation2018). Critics argue the framework does not adequately account for dynamic changes and complex feedback loops (Parker, Citation2018). It remains, nonetheless, a foundational model for sustainability assessment in both research and business contexts, given its structured and readily applicable approach (Grafton et al., Citation2023). In this section, we discuss some of surfing’s contributions to the ‘five capitals’, both from the perspective of the practice itself, as well as the associated social and physical developments. Our explanation is not exhaustive, but aims to provide a broad overview and key examples.

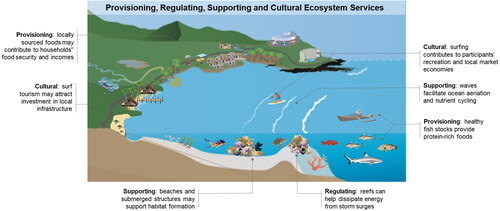

Figure 1. Surfing ecosystem representation depicting examples of cultural, provisioning, regulating and supporting ecosystem services. Diagram created with icons by Dieter Tracey (Diponegoro University Indonesia, University of Queensland), Kim Kraeer, Lucy Van Essen-Fishman, Tracey Saxby, Jane Hawkey, Max Hermanson, Christine Thurber (Integration and Application Network) (ian.umces.edu/media-library).

Human

The human capital refers to people’s skills, knowledge, capabilities and health. From a surfing’s perspective, this can be accrued by individuals and communities where surf tourism takes place, as well as to surf participants themselves. In many surf tourism destinations, both dimensions overlap, with members of local communities engaging in surf-derived livelihood activities, but also practicing the sport for leisure.

Surf-driven tourism can foster skill development and capacity building (Earhart, Citation2015), as seen in Lobitos, Peru, where locals benefited from surf training programs, improving their income opportunities and reducing the need for migration (Mach, Citation2019). In communities with paternalistic norms, it has been noted that women found greater prospects for deviating from conventional personal and professional roles through surf-related activities (Britton, Citation2015; Burtscher & Britton, Citation2022; Comer, Citation2010; Mach, Citation2019). Across the world, many surf-specific NGOs now exist (see comprehensive list at surfinghistorian.com/NGOs) offering training in various areas, such as swimming, surfing, English language, board repair, photography, and business administration (Mach, Citation2019).

A growing body of health literature has documented the therapeutic potential of surfing, as part of ‘blue spaces’, i.e. health-enabling places where water is at the center of the natural environment (BlueHealth, Citation2021; Britton et al., Citation2020; White et al., Citation2013). Positive mental health outcomes have been found among surf-therapy participants, including veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (Caddick et al., Citation2015), at-risk youth (Godfrey et al., Citation2015; McKenzie et al., Citation2021) and children with special needs (Armitano et al., Citation2015; Clapham et al., Citation2014). While fewer studies exist across the general population, qualitative evidence gathered in Victoria, Australia, revealed positive impacts on lifestyles, happiness and wellbeing among 90% of surveyed participants (Suendermann, Citation2015). The practice of surfing can also entail significant risks, including drowning, concussion, lacerations, shark attacks and fatal injuries (Mixon & Sankaran, Citation2019; Nathanson et al., Citation2002; Pikora et al., Citation2012). In Southern California, elevated risks of bacterial infections have been found after post-storm events, as urban pollutants enter ocean waters through stormwater runoff (Tseng & Jiang, Citation2012).

Social

The social capital encompasses the relationships, networks and institutions that allow individuals and societies to cooperate and thrive, as well as cultural and ethical norms (Goodwin, Citation2003; Tinch et al., Citation2015). Sport participation has been shown as an important contributor to creating, developing and maintaining social capital—albeit with instances of diminution too (Nicholson & Hoye, Citation2008).

In many iconic locations, surfing is an intrinsic part of the local ancestral culture and heritage, providing a sense of identify and belonging, which are still present today, for example, among Māori wave-riders (Kaihekengaru) of Aotearoa New Zealand (Aramoana Waiti & Awatere, Citation2019; Olive & Wheaton, Citation2021; Preston-Whyte, Citation2002; Wheaton et al., Citation2021). Qualitative interviews with Australian surfers revealed enhanced community cohesion and stronger connections with family, friends and extended professional networks (Suendermann, Citation2015). Community organizations such as ‘Surfing Mums’ (surfingmums.com) and boardriders’ clubs illustrate how social capital is built into surfer-based institutions, through mutual help and support (Booth, Citation2016; Koevska Kharoufeh, Citation2022). Surfers can also play key roles within their broader communities, e.g. beach clean-ups and ocean resources (Attard et al., Citation2015; Surfrider Foundation, Citation2021). In Aotearoa New Zealand, surfing organizations were instrumental in informing groundbreaking provisions for the legal protection of surf breaks (Atkin et al., Citation2019)

The increasing popularity of surfing has also lead to social tensions. Under the access and competition lens, waves have been framed as ‘common-pool-resources’ (Rider, Citation1998), because they are typically non-excludable (it is difficult or impossible to prevent people from accessing waves), and rivalrous (the use of the wave by one person reduces its availability to others). In an application of Ostrom’s (Citation1990) foundational framework for managing ‘the commons’, Rider (Citation1998) argued for surfers’ etiquette as a principle for optimal outcomes (by creating an orderly socialization process for dictating who ought to ride which wave and when). In practice, it is observed that many participants in surf destinations persist in adopting more confrontational forms of localism for restricting surf-break access to outsiders and newcomers (Towner & Lemarié, Citation2020). This type of neo-tribal localism is highly problematic and can effectively diminish social capital, particularly when coercion is racialized, gendered or leading to verbal abuse, physical violence or property damage (Mach & Ponting, Citation2018; Olive, Citation2016). Localism, however, has also been seen as a legitimate community response to issues related to crowding and the intrusive nature of over-tourism (Towner & Lemarié, Citation2020). Protectionist attitudes among local residents have been regarded as a counterweight against external pressures and towards preservation of existing values and identities (Hjalager, Citation2020). Recent scholarly advances in surf tourism destination governance examine how different regimes (e.g. sovereign, disciplinary, and neoliberal) can potentially aid in effectively handling access at small spatial scales (Mach & Ponting, Citation2018).

Importantly, the negative impact on social capital can expand beyond surfers themselves and affect other social groups (see further discussion in the Section on Equity and sustainability). Regrettably, in certain tourism destinations, such as across the Indo-pacific and Central-America regions, the expansion of the surfing industry and high visitor numbers have clashed with and eroded native, traditional values and forms of life held by local communities (Buckley, Citation2002; Earhart, Citation2015; Ponting & O’Brien, Citation2014).

Natural

The natural capital can be understood as the goods and services provided by natural ecosystems (Costanza et al., Citation1997). Surf-rich areas can harbor multiple forms of natural capital, such as rich biodiversity (Shuman & Hodgeson, Citation2009; Touron-Gardic & Failler, Citation2022). Through complex interactions across coastal spaces, surfers can play a role in both preserving and eroding the natural capital.

Following many hours of observation and participation, regular surfers can acquire a unique knowledge of their local areas, which can contribute to ocean stewardship and citizen’s science (Reineman et al., Citation2021). In particular, surfers’ observations can provide insights into environmental change, where sea-level rise and severe storms affects natural assets, sometimes covering spatial and temporal data gaps where no records exist (Hoffman, Citation2013; Sadrpour & Reineman, Citation2023).

Surfers have also been categorized as an environment-friendly tourist segment, with more than 90% of the surveyed population in a global study reporting being willing to pay more for surf tourism offerings that are demonstrably more sustainable than others (Mach & Ponting, Citation2021). An example of local environmental action can be found in the Nosara area in Costa Rica, which was heavily ranched for cattle production, prior to surf tourism growth. As a result of restoration and recycling efforts by NGOs staffed by surfer environmentalists, land that was once cleared 200 meters from the high-tide mark was being actively reforested (Leyh, Citation2018).

Surf participation has been shown to encourage environmental conservation behaviors and greater ethics of care for coastal landscapes (Booth, Citation2020; Lazarow, Citation2010; Nelsen, Citation2012). In addition to individual and small community initiatives, many large surf-based organizations exist that are dedicated to environmental conservation, e.g. Surfrider Foundation (surfrider.org.au), Surfers Against Sewage (sas.org.uk), Surfbreak Protection Society (surfbreak.org.nz), Save The Waves Coalition (savethewaves.org) and Surfers for Climate (surfersforclimate.org.au).

Surf-driven tourism and migration can also create adverse impacts on the natural ecosystems, including, land clearing, biodiversity loss, plastic waste, water pollution and degradation of reefs and marine ecosystems from sewerage discharge (Buckley, Citation2002). It is increasingly recognized that surf-driven coastal developments are often the primary cause of damage to environmental features that make surf destinations desirable in the first place (Martin & O’Brien, Citation2017; Reineman, Citation2016). This issue is particularly acute in areas already suffering from environmental stress, such as groundwater depletion, which can be exacerbated by rising water demands to satisfy a growing surf tourism population (LaVanchy et al., Citation2017).

Two studies in Mexico found that surf-driven developments (mostly hotels) on the coastlines or atop of dunes changed the sand flow dynamics, hydrological cycle, and wind patterns in ways that negatively impacted surf quality (Hough-Snee & Eastman, Citation2017; Valencia et al., Citation2021). Mach (Citation2021) found that tree and land clearing for a large surf resort and road development on a hillside in Bocas del Toro (Panama) led to muddy runoff entering the break during frequent high rain events. Similarly, in the Maldives, Haro (Citation2021) reported that reinforcement works to fortify a breakwall—to protect a nearby road and hotel—deteriorated wave quality, as increased refraction from waves bouncing back off the rock walls interfered with the reef breaks surfers were trying to ride. Furthermore, research suggests that as sea-levels rise, coastal areas that allow for managed retreat inland will fare better and likely be able to continue to provide surf-related benefits, while areas with imposing coastal infrastructure might be less likely to facilitate wave riding (Sadrpour & Reineman, Citation2023). Island countries, like Vanuatu (McDonnell, Citation2021) or Fiji (Neef et al., Citation2018), are especially vulnerable to climate impacts, which threaten traditional livelihoods, such as fishing and agriculture. Across these surf-rich areas, sustainable sport tourism may offer opportunities for economic diversification, as part of broader climate adaptation strategies (Wood et al., Citation2013).

Built

The built (or manufactured) capital includes the materials, goods and infrastructure produced by humans (Viederman, Citation1994). One of the largest inputs of surfing into the built capital is by driving infrastructure development, such as transportation, real estate and public services (Machado et al., Citation2018). This is most prominent in highly sought tourism destinations, where the demand for surfing has triggered the creation (or expansion) of the hospitality industry. In turn, the population influx fuels private investments in infrastructure such as hotels and restaurants, but also public assets such as roads and water networks (Earhart, Citation2015). Surf-driven charities such as SurfAid (surfaid.org), A Liquid Future (aliquidfuture.org), Waves for Water (wavesforwater.org), Surf For Life (surfforlife.org) or Surfing Doctors (surfingdoctors.com), also help establish and manage critical infrastructure in remote locations, including schools, clean water facilities and health centers (Thorpe & Rinehart, Citation2013).

The effect of surfing on the built capital can also be felt in high density areas, for example through increased real estate demand (Scorse & Hodges, Citation2017). As reported by Mach (Citation2021), property demand in surf zones has been fueled by travelers seeking to spend extended periods of time, whilst also profiting from peer-to-peer accommodation sector, which is also changing ownership dynamics in many remote coastal communities and driving up prices. While rising real estate prices may be favorable, for example, for local councils through higher revenue from property taxes, important equity questions are raised from a housing affordably perspective, which has been commented upon in the media, but has yet to be researched specifically (Heagney & Redman, Citation2022).

Surfing demand can also erode the built capital by encroaching on the exiting public infrastructure, to the point where current services become dysfunctional (e.g. sewage overflows or uncontrolled rubbish disposal) (Earhart, Citation2015). The fishing and ranching town of Tamarindo, Costa Rica, began to experience rapid coastal development, after the release of the Endless Summer II surf film in 1994, but the infrastructure never kept pace with the population growth. With particular challenges regarding storm and untreated wastewater from newly built hotels, the area was stripped of its blue flag status in 2004 and 2007, and has never regained it (Valverde, Citation2019). While this issue is not unique to Costa Rica, the extent of this problem has not been well codified, as few areas systematically collect this type of data.

Financial

The financial capital includes monetary assets and resources, which typically enable business and societies to operate (Tinch et al., Citation2015). The presence of surfing resources has been associated with increased economic growth and contributions to the market economy, attracting investments and enhancing employment opportunities for local residents (Earhart, Citation2015; Machado et al., Citation2018). The most common metric of surfing’s input into the financial capital is through direct expenditure in items such as gear and travel.

In 2022, the global surfing equipment market (surfboards, apparel and accessories) was calculated at US$4.43 billion, and expect to grow to US$5.48 billion by 2028 (EMR, Citation2022). Pre-pandemic, global expenditure on international surf tourism was estimated to be between US$31.5 to US$64.9 billion per year (Mach & Ponting, Citation2021). In the United Kingdom, the overall impact of surfing on the national economy has been estimated to UK£4.95 billion per year (in 2013 prices) (Mills & Cummins, Citation2015). In Australia’s Gold Coast, surfer’s estimated expenditure were found to contribute up to A$233 million per year to the local market economy (in 2008 prices) (Lazarow, Citation2009). A recent study of surfers at the Noosa World Surf Reserve (Queensland, Australia) estimates annual expenditure in the order of AUD 3,350 per person per year, including gear and travel (Manero & Leon, Citation2021). Across surf tourism destinations like Peru, Indonesia and Brazil, a number of studies have estimated visitors’ expenditure, which typically ranges between US$45 and US$170 per surfer per day (Tilley, Citation2001). See for details.

Table 2. Summary of surfing direct expenditure studies.

Besides direct expenditures, other measures of economic impact have been proposed. For example, McGregor and Wills McGregor and Wills (Citation2017), used changes in measurable night lights as a proxy for local economic activity. This global study found that the presence of high quality surfing waves was associated with higher economic activity within a 5 km radius, and spillover effects were detectable up to 50 km away. Further, the study found that the discovery of and access to new surf breaks was associated with faster economic growth. Vice-versa, the disappearance of good quality waves—as observed in Maderia, Portugal, and Mundaka, Spain—preceded a slowdown in economic activity. The authors note the paradox that the road construction and sand degrading works that caused the waves to disappear were put in place, precisely, to generate gains for the local economy (McGregor & Wills, Citation2017).

Financial capital can also come in the form of rights to surf resources, whereby permit-holders are granted exclusive access to certain surf breaks under government-controlled quota systems. This occurred, for example, in Fiji, where traditional fishing grounds (qoliqoli) served as management instruments to regulate access to surf breaks before a national decree ended this resource management regime (Ponting & O’Brien, Citation2014). To access restricted areas, as it was in Fiji and remains in certain areas of the Maldives (Buckley et al. (Citation2017), tourists and operators must pay a fee to the license holder—making the license, in effect, a financial asset.

Surfing ecosystems

While the concept of ‘resources’ typically frames natural assets as inputs for human use or consumption (Bateman & Mace, Citation2020), recent surfing scholarship has broadened the perspective to consider surf breaks as part of connective seascapes, referred to as ‘surfing ecosystems’ (Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Manero, Citation2023; Reineman et al., Citation2021). Here, we define ‘surfing ecosystems’ the spaces and complex interactions between the multiple living and non-living components of ocean and coastal environments were surfing takes place. These may include elements like waves, reefs, currents, sediment, flora and fauna, as well as surfers themselves and other stakeholders who utilize these spaces. Thus, while ‘surfing resources’ and ‘surfing ecosystems’ are related concepts, they differ in similar ways to other environmental features, such as ‘marine resources’ and ‘marine ecosystems’ (Alexander, Citation1993). While surfing resources are an integral part of surfing ecosystems, the study and management of ecosystems extend beyond the use of specific assets, to deepen the understanding of functions and interconnections within the system.

When assessing the relevance of natural ecosystems from a human-centric perspective, a commonly used term is ‘ecosystem service’ (Costanza et al., Citation1997). We acknowledge this is only one construct, and others exist, namely those conceptualized through Indigenous ontologies (Redvers et al., Citation2022). The ‘ecosystem services’ concept refers to any ecosystem function that is beneficial to humans, directly or indirectly, and classifies such functions in four categories: cultural, provisioning, regulating and supporting (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Citation2005). See for definitions and examples and for a graphical illustration.

Table 1. Summary of four categories of ecosystem services with examples Relevant to surfing ecosystems.

Most conceptualizations of surfing ecosystems are focused on their contributions to cultural ecosystem services (CES), given the associated recreational and lifestyle values (Reineman, Citation2016; Román et al., Citation2022; Scheske et al., Citation2019). Across coastal tourism destinations, CES have been identified as useful framework to understand visitor perceptions and experiences, across diverse seaside and land-based tourism destinations (Ram & Kay Smith, Citation2022). A recent literature review of CES associated with surfing identified social benefits as the most prevalent theme, including improvements in quality of life, general well-being, self-esteem, physical conditioning, social interactions and community engagement, among many others (Román et al., Citation2022). The systematic review also identified negative interactions, such as conflicts among users and inter-cultural tensions.

Surfing ecosystems, particularly those comprising tropical coral reefs, are often co-located with rich biodiversity hotspots, harboring high abundance and diversity of fish species (Reineman, Citation2016). Thus, for their contribution to subsistence and commercial fishing (Olds et al., Citation2018), surfing ecosystems can play a role in provisioning ecosystem services (PES). It is, therefore, fundamental that marine protection strategies account for synergies and trade-offs in protecting multiple conservation targets (Touron-Gardic & Failler, Citation2022).

Regulating services of surfing ecosystems can be those provided by submerged natural features and land vegetation (e.g. mangroves) acting as natural buffers in the protection against storms and tsunamis (Marois & Mitsch, Citation2015; Thran et al., Citation2021). Notably, healthy coral structures have been found to be twice as effective in tsunamis protection compared to dead reefs, given the higher energy dissipation through rough surfaces (Kunkel et al., Citation2006). Across the world, climatic and anthropogenic pressures are resulting in the significant loss of mangrove and coral reefs, which call for greater protection and restoration of coastal ecosystems (Carugati et al., Citation2018).

Submerged and land-based components of surfing ecosystems contribute to supporting ecosystem services through a number of functions, such as sediment transport and storage, habitat formation, feeding and nursery areas for a variety of fish species (Olds et al., Citation2018). Further, breaking waves play an important role in the ocean aeriation process, whereby oxygen, nitrogen and carbon dioxide are transferred between the water and the atmosphere (Mori et al., Citation2009).

Understanding the multiple services provided by surfing ecosystems, as well as their inter-relations and trade-offs, is fundamental for adequate management and policy (Chen & Teng, Citation2016). For example, as demand for recreational surfing grows, planning authorities may allow expansion of beach access and other tourism infrastructure, in order to increase gains from ‘cultural’ ecosystem services, such as direct expenditure. However, when land and vegetation are cleared to accommodate coastal developments, ‘regulating’ and ‘supporting’ functions may be negatively impacted (Arroyo et al., Citation2019; Buckley, Citation2002; Scheske et al., Citation2019) (see Natural section above). Examples also exist where multiple services are balanced, such in the case of the ‘Superbank’ at Snapper Rocks in north-east Australia, which forms as a result of Tweed Sand Bypassing Project (Castelle et al., Citation2009). As sand is dredged from the Tweed River entrance to ensure its navigability, sediment is relocated to purposely nourish southern Gold Coast beaches, which helps the formation of the world-renowned wave.

Economic values

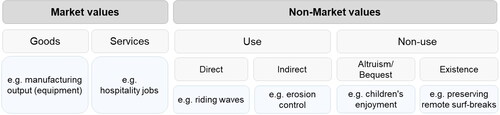

So far, we have reviewed the ‘five capitals’ and ‘ecosystem services’ frameworks, which can be applied to understand the outputs and processes for which surf-rich areas may be deemed important or valuable. Subsequently, ‘values’ and ‘valuation’ approaches can be used to quantify the magnitude of that worth and changes in it (Baldwin, Citation2000). An important distinction exists between a person’s ‘values’ and the economic concept of ‘value’ (Segerson, Citation2017). Individuals’ ideas about what is good or preferable can be framed as their held values, whilst the worth people associate with a particular good or service is referred to as assigned value (Brown, Citation1984). Economic valuation seeks to measure assigned values, which can be grouped into ‘market’ and ‘non-market’ values (Segerson, Citation2017).

‘Market values’ are those derived from goods and services that are traded in markets (Di Maio et al., Citation2017; Maack & Davidsdottir, Citation2015), such as surf equipment or hospitality services (Wheaton, Citation2020). Given the ease of measurement, market values have been the focus of a large proportion of surfing economics studies, typically accounting for visitors’ direct expenditure (see ). Such studies provide important data related to the market economy, but they do not inform about the true value people place on surfing resources or the broader benefits derived from practicing the activity.

‘Non-market values are those associated with goods or services that cannot be bought or sold in markets (Champ et al., Citation2017). ‘Non-market values’ are often conceptualized under the total economic value (TEV) framework, which distinguishes between ‘use’ and ‘non-use values’ (Segerson, Citation2017). ‘Use values’ arise from the use or interaction with the environment, and can be ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’. ‘Direct use values’ include amenity services, like recreation, scenic views or nature observation (Freeman, Citation2003). Spectators who contemplate surfers and waves also engage in a form of direct use, which is becoming dominant in places such as Nazaré, Portugal, where thousands of visitors witness professional big wave contests every year (Azevedo, Citation2023). ‘Indirect use’ values from surfing resources comprise benefits derived in an indirect manner, for example healthy coral reefs supporting biodiversity (see Surf breaks section).

Surfing ecosystems can also provide ‘passive’ or ‘non-use values’, whereby a person derives benefit from the mere existence of a resource (e.g. bioethics) or from knowing others are benefiting from the use of the resource (Segerson, Citation2017). For instance, parents may derive benefit from the children’s enjoyment of surfing, even if they don’t practice the activity themselves (i.e. altruistic value) (Oram & Valverde, Citation1994). Other forms of ‘non-use’ value include ‘bequest values’— i.e. people’s appreciation for the enjoyment by future generations (Nelsen, Citation2012; Silva & Ferreira, Citation2014) ().

Economic valuation

The economic impacts of tourism have been examined by a large body of literature (Liu et al., Citation2022). Within the specific context of surf-tourism, the most common approach has been to record surf-related expenses among a sample of the surfing population (e.g. Lazarow, Citation2009). However, issues of representativeness may arise, given that non-random sampling (e.g. snowball or purposeful) is often required to survey hard-to-reach populations (Parsons, Citation2017). Once expenditures have been recorded, tourism and manufacturing multiplying factors can be applied to account for the overall increase in output, labor and employment in the local economy (Frechtling & Horváth, Citation1999).

To quantify the subjective values that people place the environment, a set of techniques exist known as non-market valuation or NMV (Freeman et al., Citation2014). While NMV allows us to associate monetary figures to certain environmental features, these are not prices, but instead a measure of value. Information obtained though NMV has been used over the last three decades to evaluate trade-offs and inform environmental decision-making (Champ et al., Citation1997). Two main approaches exist in NMV: revealed and stated preferences. Revealed preferences methods estimate values by observing people’s actual behavior associated to an environmental feature (Segerson, Citation2017). The most common approach in surf NMV is the travel cost method, which infers values of the benefits perceived by the users (referred to as ‘consumer surplus’), based on the sacrifices made to visit the site, including travel time and expenses (Parsons, Citation2017). One limitation of the travel cost approach is that it underestimates the true efforts people make to access the site, given that many surfers aspire to live close to the surf breaks, thus minimizing their travel costs (Wright et al., Citation2014). To overcome this limitation, in a study of house prices in Santa Cruz (California), Scorse et al. (Citation2015) employed the hedonic pricing approach, which estimates values that are capitalized in observable prices. The study found that—controlling for other factors—a home next to the surf was worth US$106,000 more than an equivalent house located one mile (1.6 km) away.

Stated preferences NMV methods are based on surveys where participants are presented with a hypothetical scenario and asked to choose among a set of management options, often involving a form of payment (Segerson, Citation2017). For example, participants may be presented with a scenario in which their local beaches could be affected by an oil spill, and then asked how much would they be willing to pay for a program that would avoid or mitigate the impact (Egan et al., Citation2022). While stated preferences are common in the valuation of tourism and recreational values (e.g. Prayaga et al., Citation2010; Rathnayake, Citation2016; Zimmerhackel et al., Citation2018), this technique remains under-applied in the valuation of surf recreation (see ).

Table 3. Summary of non-market valuation surf studies.

A separate set of economic valuation techniques exist that relates to impacts on participants’ health and well-being (Whitehead & Ali, Citation2010). These include, among others, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), two-step transfer functions and direct correlations with quantifiable parameters, which have been applied to other nature-based activities, such as visits to national parks (Buckley et al., Citation2019). Quantifying exercise-induced benefits in monetary terms can be important for employers, healthcare providers and insurers, to whom economic benefits may accrue from reduced stress, higher productivity and lower medical costs (Buckley & Chauvenet, Citation2022; van den Bosch & Ode Sang, Citation2017; Wolf & Robbins, Citation2015).

Equity and sustainability

As it occurs across other forms of environmental and economic assessments, a comprehensive understanding of the value of surfing ecosystems requires accounting for negative externalities, both in the short and long term (Freeman et al., Citation2014). In particular, excessive surfing pressures can deteriorate natural, social or human capitals, which warrants careful consideration of overall gains and losses. In tourism destinations, such pressures typically grow over time, as the demand for environmental goods and services (e.g. waves and clean water) reaches the carrying capacity, i.e. the maximum number of people who can visit the area without affecting the tourism experience or residents’ quality of life, and which can be supported by the natural environment in a sustainable manner (Loverio et al., Citation2023). While other forms of beach tourism can also place undue pressures on the environment (Ong et al., Citation2011), the desire for (and subsequent overcrowding) of good quality waves presents a remarkable case of competition for rare natural resources and their surrounding spaces. Many of the world’s good quality waves are located in peripheral areas, i.e. locations beyond large metropolitan centers, including small islands and remote rural areas, which may struggle to accommodate pressures from tourist and new residents (Cheer et al., Citation2022).

Previous research has found evidence that, once the recreational carrying capacity of surf breaks is reached, the use value and local quality of life benefits might diminish (Mach & Ponting, Citation2018; Nazer, Citation2004). Highly concentrated demands for tourism have led to the creation of so-called surf slums or surf ghettos (Barilotti, Citation2008). Alternative models exist where hotel operators are able to cap the number of surfers staying in the area at any given time, with some being able to charge between US$6,000 and US$10,000 per person per week for these exclusive experiences (Buckley et al., Citation2017; Mach & Ponting, Citation2018). While visitation numbers have not been systematically analyzed, it has been theoretically posed that surfers with lower spending capacity and higher crowding thresholds will continue to visit areas with high levels of crowding, while those with higher purchasing power and lower crowding thresholds will seek other places to visit (Mach & Ponting, Citation2018).

Within the context of fast-growing surf destinations, there is ongoing debate about the impact of tourism on sustainable economic development (Mach, Citation2019). This particularly concerns the complex interconnections between poverty, growth and inequality, which are well studied in the macroeconomics literature (Bourguignon, Citation2004). On the one hand, surf-driven growth is often claimed to benefit foreign investors the most, with disproportionately little ‘trickle-down’ effects on local communities (Ponting & O’Brien, Citation2014). On the other hand, sustainable development approaches have been observed as effective catalysts for capacity building and poverty alleviation (O’Brien & Ponting, Citation2013; Usher & Kerstetter, Citation2014).

The relationship between per capita incomes and income inequality (as well as per capita income and environmental degradation) has been proposed to follow an inverted U-curve, whereby adverse outcomes rise during the first stages of economic development, to then star dropping past a tipping point. This is known as the (environmental) Kuznet’s Curve (Dinda, Citation2004; Kuznets, Citation1955). While the actual occurrence of such relationship is much debated, and dependent on a myriad of factors, it is nonetheless a helpful framework to conceptualize trajectories for sustainable development, inducing within the context of growing tourism industries (Arbulú et al., Citation2015; Ozturk et al., Citation2016).

Within the surfing literature, there is evidence indicating that the initial phase of rapid development may overwhelm infrastructure and lead to near term pollution and disproportionate use of natural resources (e.g. Earhart, Citation2015). However, overtime and through greater awareness and investment capacity, it is likely that stakeholders choose to protect and restore a sustainable equilibrium. The costs required to implement these changes, however, has also not be researched in studies related to surf resource valuations. Further, no studies have yet investigated the existence of a Kuznets’s curve for income inequality or environmental impacts associated with surf tourism. Understanding such impacts, at various stages of the Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle (Butler, Citation2006), could help stakeholders in the tourism industry understand the destination’s current situation, anticipate future trends, and plan for sustainable management of the area.

Adequate governance also plays a key role in management of surfing ecosystems, with a growing number of jurisdictions adopting frameworks for the protection of surfing resources. As Monteferri et al. (Citation2020) explain ‘Surf breaks have historically been ‘invisible’ for legal frameworks and have only recently started to be recognized as concrete legal subject matter’ (p. 151). Existing forms of regulation and protection range from national-wide legislation (in Peru and Aotearoa New Zealand) to non-statutory reserves (e.g. Spain and Portugal) (Mead & Atkin, Citation2019; Touron-Gardic & Failler, Citation2022). Given the significant overlap and interaction of surfing resources with other coastal values (e.g. marine biodiversity), there is an opportunity for coastal regulations to promote preservation of both cultural and natural heritage. As more attention is driven towards the justice and equity dimesons of access to surfing resources, lessons can be learnt from other contested recreational spaces, such as river watersheds, where natural resources (e.g. water) are disputed by extractive (e.g. irrigation) and recreational (e.g. boating) activities (Scruggs et al., Citation2023).

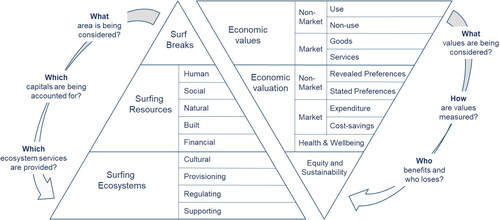

Surfing values and valuation framework

Following our review of surf-related principles in environmental management and economics, we propose a six-step framework () for the systematic understanding of surfing ecosystems and quantification of their values, following six guiding questions:

What area is being considered?

Which capitals are being accounted for?

Which ecosystem services are provided?

What values are being considered?

How are values measured?

Who benefits and who loses?

A useful first step is to identify the area of study, including the break or break(s) that are to be assessed. Many surf-rich areas host a suite of breaks with often varying characteristics, which will respond differently to environmental changes and peoples’ preferences. For example, deep reefs can generate consistent big waves suitable for advanced surfers, while near-shore breaks often create smaller waves over sandy seafloors).

Second, a framing around ‘surfing resources’ can assist in recognizing which forms of capital are generated (or eroded), including human, social, natural, built and financial. While surfing’s impacts are typically visible in the form of built or financial capitals, effects on human, social and natural capitals may take time to emerge and typically require closer qualitative analyses to uncover their extent and ramifications.

Third, a broader perspective can help recognize how the surfing resources in question are part of, and contribute to local ecosystem. Here, it can be suitable to identify which of the four types of ecosystem services (provision, regulating, supporting and provisioning) are present and how they are interconnected to each other. Understanding such interlinkages is fundamental for later stages of valuation, where flow-on effects and externalities of coastal changes are likely to affect the existing land and seascapes, beyond immediate, readily observable impacts. e.g. shifts in sediment transport can cause ecological damages to beach habitats (Hanley et al., Citation2014).

Further, it is useful to classify what kind of values are to be assessed, to avoid omitting and double-counting benefits. Market values, which are observable through market transactions, may include surf-driven goods or services. Conversely, non-market values, including use and non-use, capture welfare benefits such as recreation, enjoyment and altruism.

For monetary quantification, different valuation methods will be warranted, depending on the values to be assessed. Choosing how values are measured will also depend on the purpose of the valuation and whose values are accounted for. Changes to peoples’ welfare can be estimated through non-market methods, while gains (or losses) in terms of revenues and costs may be quantified through market-based methods. Methods derived from health economics can assist in quantifying changes to participants’ health and wellbeing.

Finally, assessments and valuation of surfing ecosystems should be underpinned by sustainability and equity considerations, including recognition of winners and losers. We contend that externalities should be accounted for in a way that reflects the overall impact of surf-driven changes, including those occurring further away from the surf break and later in time. This is true in two directions, i.e. when examining pressures exerted by surfing demands on the environment, as well as external pressures impacting the value of surfing ecosystems.

The framework proposed in this study can serve to guide assessments of surfing ecosystems and their associated values, which can subsequently inform decision-making processes aimed at coastal management. Future research could apply the newly presented framework to specific case studies for surfing ecosystem analysis and valuation. This could be done for already modified systems that have well established management plans, such as the Gold Coast of Australia, with its sand bypass and nourishment system, in order to evaluate costs and benefits of different management options (City of Gold Coast, Citation2020). The framework could also be applied to locations where surfing ecosystems are rapidly changing, so as to effectively plan for the desired outcomes. Beyond localized surf management, holistic valuation of surfing resources has the potential to fit into the broader goal of accurate natural capital accounting (Farrell et al., Citation2022). In particular, understanding the functions and values of surfing ecosystems can help inform ocean accounts for improved ocean governance (Perkiss et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

Amidst a wide range of sustainability topics, management of surfing resources is emerging as a question of significance across surf-rich areas, particularly tourism destinations. Indeed, surfing resources can be a driver for social and economic growth, as well as favoring synergies with other marine and coastal ecological values (Touron-Gardic & Failler, Citation2022). From this perspective, it is fundamental that surfing resources, and the ecosystems they are part of, are protected from climatic and anthropogenic changes (e.g. erosion or coastal developments), which can severely damage the multiple values emerging from them. At the same time, surf-driven demand can result in exacerbated pressures beyond the carrying capacity of the local area, which in turn can result in irreversible environmental degradation and adverse socio-cultural outcomes (Ponting, Citation2009; Ruttenberg & Brosius, Citation2017). Thus, the pressure-impact relationship between surf breaks and their surrounding environments is bi-directional—in some cases surfing resources being the cause and others the recipient of adverse effects.

As social and environmental concerns become a higher priority for peripheral travelers (Cooper, Citation2023), including surfers (Mach & Ponting, Citation2021), decision-makers involved in tourism planning and development ought to account for the growing impacts and possible mitigation strategies. For example, management plans of surf and marine tourism destinations could consider limiting the use of boat anchors to sandy ocean bottoms (thus avoiding damage to live reefs) or restricting car access onto beaches that serve as nesting grounds for local fauna (Monteferri et al., Citation2020). Voluntary (or mandatory) levies could be examined as financing mechanism for environmental conservation initiatives, as it occurs in marine parks catering for diving tourists (Depondt & Green, Citation2006; White et al., Citation2022).

It is fundamental that the benefits and costs associated with surfing ecosystems be considered in a holistic manner, taking into account multiple forms of value and carefully reflecting on equity implications for humans and the environment. Understanding the value of surfing ecosystems is not only important for management policies that affect users, but fits with global efforts towards improved assessments of nature’s diverse values (Pascual et al., Citation2023). New information on surf-related values could be integrated into well-established approaches, such as the United Nations’ System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA), which aims to integrate different sources of environmental information, and increase its use by governments, businesses and other decision-makers (Vardon et al., Citation2018).

To this aim, the surfing ecosystems valuation framework can assist tourism scholars by providing a systematic approach for assessing the impacts of surf-visitation over time and across regions. Further, the framework can be applied to set strategic goals regarding sustainability and development of surf-rich destinations, and, accordingly, define policies and regulations that consider the array of complex and interconnected values derived from surfing ecosystems. A step-by-step approach, may reduce the risk of omitting (or double-counting) key values, which could result in over or under-estimation of benefits and impacts, leading to flawed decision-making. Furthermore, demonstrating the value of surfing ecosystems can support their recognition as legal subject matters, and hence contribute to their protection through formal provisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ana Manero

Dr. Ana Manero is an environmental economist, focusing on sustainable management of natural resources, including water, agriculture and mining. Besides her primary work on water management and policy, Dr Manero is advancing surf research in Australia, by building a better understanding of the values associated with surfing resources and identifying mechanisms to improve their management and protection. As of 2023, Dr Manero works as a research fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy (Australian National University) and holds an adjunct position at the University of Western Australia. URL: https://researchprofiles.anu.edu.au/en/persons/ana-manero; https://www.surfingeconomics.org/

Leon Mach

Dr. Leon Mach is an Associate Professor of Environmental Policy and Socioeconomic Values at the School for Field Studies in Bocas del Toro, Panama. His research focuses on the human dimensions of natural resource governance and sustainable tourism. He has implemented community development and resource conservation initiatives in many coastal communities, including a USAID funded sustainable surf tourism destination certification program in El Salvador. Leon was a 2021/2022 Fulbright Scholar Award recipient and co-founder of both the International Association for Surfing Researchers and SeaState Educational Travel. He is also on the Foster the Earth board of directors.

References

- Alexander, L. M. (1993). Large marine ecosystems: A new focus for marine resources management. Marine Policy, 17(3), 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-597X(93)90076-F

- Aramoana Waiti, J. T., & Awatere, S. (2019). Kaihekengaru: Māori surfers’ and a sense of place. Journal of Coastal Research, 87(sp1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI87-004.1

- Arbulú, I., Lozano, J., & Rey-Maquieira, J. (2015). Tourism and solid waste generation in Europe: A panel data assessment of the environmental Kuznets curve. Waste Management (New York, N.Y.), 46, 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2015.04.014

- Armitano, C. N., Clapham, E. D., Lamont, L. S., & Audette, J. G. (2015). Benefits of surfing for children with disabilities: A pilot study. Palaestra, 29(3), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.18666/PALAESTRA-2015-V29-I3-6912

- Arroyo, M., Levine, A., Brenner, L., Seingier, G., Leyva, C., & Espejel, I. (2020). Indicators to measure pressure, state, impact and responses of surf breaks: The case of Bahía de Todos Santos World Surfing Reserve. Ocean & Coastal Management, 194, 105252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105252

- Arroyo, M., Levine, A., & Espejel, I. (2019). A transdisciplinary framework proposal for surf break conservation and management: Bahía de Todos Santos World Surfing Reserve. Ocean & Coastal Management, 168, 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.10.022

- Atkin, E., Bryan, K., Hume, T., Mead, S. T., & Waiti, J. (2019). Management Guidelines for Surfing Resources. Aotearoa New Zealand Association for Surfing Research. www.surfbreakresearch.org

- Atkin, E. A., & Greer, D. (2019). A comparison of methods for defining a surf break’s swell corridor. Journal of Coastal Research, 87(sp1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI87-007.1

- Attard, A., Brander, R. W., & Shaw, W. S. (2015). Rescues conducted by surfers on Australian beaches. Accident; Analysis and Prevention, 82, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.05.017

- Azevedo, A. (2023). Pull and push drivers of giant-wave spectators in Nazare, Portugal: A cultural ecosystem services assessment based on geo-tagged photos. Land, 12(2), 360. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020360

- Baldwin, J. (2000). Tourism development, wetland degradation and beach erosion in Antigua, West Indies. Tourism Geographies, 2(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680050027897

- Barbier, E. B., Hacker, S. D., Kennedy, C., Koch, E. W., Stier, A. C., & Silliman, B. R. (2011). The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological Monographs, 81(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-1510.1

- Barilotti, S. (2008). Lost horizons: Surfer colonialism in the 21st century. In P. Moser (Ed.), Pacific Passages: An Anthology of Surf Writing (pp. 258–268). University of Hawai'i Press. https://doi.org/10.21313/9780824863838-065

- Bateman, I. J., & Mace, G. M. (2020). The natural capital framework for sustainably efficient and equitable decision making. Nature Sustainability, 3(10), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0552-3

- BlueHealth. (2021). Living environment, climate & health. https://bluehealth2020.eu/research/

- Booth, D. (2016). The bondi surfer: An underdeveloped history. Journal of Sport History, 43(3), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.43.3.0272

- Booth, D. (2020). Nature sports: Ontology, embodied being, politics. Annals of Leisure Research, 23(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2018.1524306

- Bosquetti, M. A., & de Souza, M. A. (2019). Surfonomics. Guarda do Embaú, Brazil. The economic impact of surf tourism on the local economy. S. t. W. Coalition. https://www.savethewaves.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/GuardaDoEmbau_SurfonomicsStudy.pdf

- Bourguignon, F. (2004). The poverty-growth-inequality triangle. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, New Delhi. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/449711468762020101/pdf/28102.pdf

- Britton, E. (2015). Just add surf: The power of surfing as a medium to challenge and transform gender inequalities. In Sustainable stoke: Transitions to sustainability in the surfing world. Plymouth University Press.

- Britton, E., Kindermann, G., Domegan, C., & Carlin, C. (2020). Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promotion International, 35(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day103

- Brown, T. C. (1984). The concept of value in resource allocation. Land Economics, 60(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.2307/3146184

- Brumbaugh, R. (2017). The nature conservancy. https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/protecting-million-dollar-reefs-key-sustaining-global-tourism

- Buckley, R. (2002). Surf tourism and sustainable development in Indo-Pacific islands. I. The industry and the islands. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(5), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667176

- Buckley, R., Brough, P., Hague, L., Chauvenet, A., Fleming, C., Roche, E., Sofija, E., & Harris, N. (2019). Economic value of protected areas via visitor mental health. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5005. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12631-6

- Buckley, R. C., & Chauvenet, A. L. M. (2022). Economic value of nature via healthcare savings and productivity increases. Biological Conservation, 272, 109665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109665

- Buckley, R. C., Guitart, D., & Shakeela, A. (2017). Contested surf tourism resources in the Maldives. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.03.005

- Burtscher, M., & Britton, E. (2022). There was some kind of energy coming into my heart: Creating safe spaces for Sri Lankan women and girls to enjoy the wellbeing benefits of the ocean. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342

- Butler, R. (Ed.). (2006). The tourism area life cycle (Vol. 1). In Applications and modifications. Channel View Publications.

- Butt, T., & Russell, P. (2004). Surf science. Alison Hodge.

- Caddick, N., Smith, B., & Phoenix, C. (2015). The effects of surfing and the natural environment on the well-being of combat veterans. Qualitative Health Research, 25(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314549477

- Carugati, L., Gatto, B., Rastelli, E., Lo Martire, M., Coral, C., Greco, S., & Danovaro, R. (2018). Impact of mangrove forests degradation on biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 13298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31683-0

- Castelle, B., Turner, I. L., Bertin, X., & Tomlinson, R. (2009). Beach nourishments at Coolangatta Bay over the period 1987–2005: Impacts and lessons. Coastal Engineering, 56(9), 940–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2009.05.005

- Champ, P. A., Bishop, R. C., Brown, T. C., & McCollum, D. W. (1997). Using donation mechanisms to value nonuse benefits from public goods. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 33(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1997.0988

- Champ, P. A., Boyle, K., & Brown, T. C. (Eds.). (2017). A primer on nonmarket valuation (2nd ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7104-8.

- Cheer, J. M., Mostafanezhad, M., & Lew, A. A. (2022). Cultural ecosystem services and placemaking in peripheral areas: A tourism geographies agenda. Tourism Geographies, 24(4–5), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.2118826

- Chen, C.-L., & Teng, N. (2016). Management priorities and carrying capacity at a high-use beach from tourists’ perspectives: A way towards sustainable beach tourism. Marine Policy, 74, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.09.030

- City of Gold Coast. (2020). Gold coast surf management plan. https://www.goldcoast.qld.gov.au/Council-region/Future-plans-budget/Plans-policies-strategies/Our-plans/Gold-Coast-Surf-Management-Plan#:∼:text=The%20economic%20contribution%20of%20surfing,in%20the%20Gold%20Coast%20economy.

- Clapham, E. D., Armitano, C. N., Lamont, L. S., & Audette, J. G. (2014). The ocean as a unique therapeutic environment: Developing a surfing program. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 85(4), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2014.884424

- Clark, R. (2018). Natural capital: The risks of losing sight of nature. In V. Anderson (Ed.), Debating Nature’s Value: The Concept of ‘Natural Capital’ (pp. 61–67). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99244-0_8

- Coffman, M., & Burnett, K. (2009). The value of a wave. An analysis of the mavericks region and an analysis of the mavericks wave from an ecotourism perspective. S. t. W. Coalition. https://www.savethewaves.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/SaveTheWaves_Mavericks_SurfonomicsStudy.pdf

- Comer, K. (2010). Surfer girls in the New World Order. Duke University Press.

- Cooper, E. (2023). Making sense of sustainable tourism on the periphery: Perspectives from Greenland. Tourism Geographies, 25(5), 1303–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.2152955

- Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., & van den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387(6630), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

- Depondt, F., & Green, E. (2006). Diving user fees and the financial sustainability of marine protected areas: Opportunities and impediments. Ocean & Coastal Management, 49(3–4), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2006.02.003

- Development, W. A. (2022). Ocean Reef Marina. https://developmentwa.com.au/projects/industrial-and-commercial/ocean-reef-marina/overview

- Di Maio, F., Rem, P. C., Baldé, K., & Polder, M. (2017). Measuring resource efficiency and circular economy: A market value approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 122, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.02.009

- Dinda, S. (2004). Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecological Economics, 49(4), 431–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.02.011

- Earhart, N. H. W. (2015). The effects of surf-driven development on the local population of Playa Gigante, Nicaragua (Publication Number 10017883) Thesis. University of Denver. ProQuest One Academic. Denver. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1397/

- Egan, A. L., Rolfe, J., Cassells, S., & Chilvers, B. L. (2022). Potential changes in the recreational use value for Coastal Bay of Plenty, New Zealand due to oil spills: A combined approach of the travel cost and contingent behaviour methods. Ocean & Coastal Management, 228, 106306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106306

- EMR. (2022). Global surfing equipment market share, size, growth, analysis, trends, forecast. https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/surfing-equipment-market

- Farrell, C. A., Aronson, J., Daily, G. C., Hein, L., Obst, C., Woodworth, P., & Stout, J. C. (2022). Natural capital approaches: Shifting the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration from aspiration to reality. Restoration Ecology, 30(7), e13613. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13613

- Frechtling, D. C., & Horváth, E. (1999). Estimating the multiplier effects of tourism expenditures on a local economy through a regional input-output model. Journal of Travel Research, 37(4), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903700402

- Freeman, A. M. (2003). Economic valuation: What and why. In P. A. Champ, K. J. Boyle, & T. C. Brown (Eds.), A primer on nonmarket valuation (pp. 1–25). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0826-6_1

- Freeman, A. M., Herriges, J. A., & Kling, C. L. (2014). The measurement of environmental and resource values: Theory and methods (3rd ed.). RFF Press. http://econdse.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Freeman-Herriges-Kling-2014.pdf

- Godfrey, C., Devine-Wright, H., & Taylor, J. (2015). The positive impact of structured surfing courses on the wellbeing of vulnerable young people. Community Practitioner, 88(1), 26–29.

- Goodwin, N. R. (2003). Five kinds of capital: Useful concepts for sustainable development. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/7051857.pdf

- Grafton, Q., Manero, A., Chu, L., & Wyrwoll, P. (2023). The price and value of water: An economic review. Cambridge Prisms: Water, 1, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2023.2

- Graham, S., Lukasiewicz, A., Dovers, S., Robin, L., McKay, J., & Schilizzi, S. (2017). Natural resources and environmental justice: Australian perspectives. CSIRO Publishing. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/anu/detail.action?docID=4826497

- Hanley, M. E., Hoggart, S. P. G., Simmonds, D. J., Bichot, A., Colangelo, M. A., Bozzeda, F., Heurtefeux, H., Ondiviela, B., Ostrowski, R., Recio, M., Trude, R., Zawadzka-Kahlau, E., & Thompson, R. C. (2014). Shifting sands? Coastal protection by sand banks, beaches and dunes. Coastal Engineering, 87, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2013.10.020

- Haro, A. (2021). Maldives surf breaks are in danger from rampant coastal development. The Inertia. https://www.theinertia.com/surf/maldives-surf-breaks-are-in-danger-from-rampant-coastal-development/

- Heagney, M., & Redman, E. (2022). Regional house prices surge as Melburnians flood coastal and tree-change hotspots. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/property/news/regional-house-prices-surge-as-melburnians-flood-coastal-and-tree-change-hotspots-20220127-p59rpu.html

- Hjalager, A.-M. (2020). Land-use conflicts in coastal tourism and the quest for governance innovations. Land Use Policy, 94, 104566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104566

- Hodges, T. (2014). Impacto Económico del Surf en la Bahía de Todos Santos, Baja California, México. S. t. W. Coalition. https://savethewaves.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Surfonomics_SanMiguelBaja_2014.pdf

- Hodges, T. (2015). The economic impact of surfing in Huanchaco World Surfing Reserve. S. t. W. Coalition. https://www.savethewaves.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/HuanchacoSurfonomicsStudy_SaveTheWaves.pdf

- Hoffman, J. (2013). Q&A: Surfing scientist. Nature, 503(7476), 341–341. https://doi.org/10.1038/503341a

- Hough-Snee, D. Z., & Eastman, A. S. (2017). Consolidation, creativity, and (de) colonization in the state of modern surfing. In D. Z. Hough-Snee & A. S. Eastman (Eds.), The critical surf reader (pp. 84–108). Duke University Press.

- Hume, T. M., Mulcahy, N., & Mead, S. T. (2019). An overview of changing usage and management issues in New Zealand’s surf zone environment. Journal of Coastal Research, 87(sp1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI87-001.1

- Keith, H., Vardon, M., Stein, J. A., Stein, J. L., & Lindenmayer, D. (2017). Ecosystem accounts define explicit and spatial trade-offs for managing natural resources. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(11), 1683–1692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0309-1

- Koevska Kharoufeh, N. (2022). Aussie mums with a shared passion create unique mothers’ group. nine.com.au. https://honey.nine.com.au/parenting/aussie-mums-with-a-passion-for-surfing-create-unique-mothers-group/8f0601be-e70a-4acf-b68f-83b044d74466

- Kosanic, A., & Petzold, J. (2020). A systematic review of cultural ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Ecosystem Services, 45, 101168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101168

- Krause, S. (2012). Pilgrimage to the Playas: Surf tourism in Costa Rica. Anthropology in Action, 19(3), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.3167/aia.2012.190304

- Kunkel, C. M., Hallberg, R. W., & Oppenheimer, M. (2006). Coral reefs reduce tsunami impact in model simulations. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(23), L23612. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027892

- Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review, 45(1), 1–28.

- LaVanchy, G. T., Romano, S. T., & Taylor, M. J. (2017). Challenges to water security along the “Emerald Coast”: A political ecology of local water governance in Nicaragua. Water, 9(9), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9090655

- Lazarow, N. (2007). The value of coastal recreational resources: A case study approach to examine the value of recreational surfing to specific locales. Journal of Coastal Research, (Special Issue 50), 12–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26481547

- Lazarow, N. (2009). Using observed market expenditure to estimate the value of recreational surfing to the Gold Coast, Australia. Journal of Coastal Research, 56(Special Issue 56), 1130–1134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25737963

- Lazarow, N. (2010). Managing and valuing coastal resources: An examination of the importance of local knowledge and surf breaks to coastal communities [PhD Thesis]. The Australian National University. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/150598

- Lazarow, N., Miller, M., & Blackwell, B. (2008). The value of recreational surfing to society. Tourism in Marine Environments, 5(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427308787716749

- Leyh, J. (2018). Resisting mass tourism: Local strategies and challenges to maintain sustainable development in Nosara, Costa Rica [Masters’ Thesis]. California State University, Fullerton. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12680/n583xv94b

- Liu, A., Kim, Y. R., & Song, H. (2022). Toward an accurate assessment of tourism economic impact: A systematic literature review. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 3(2), 100054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2022.100054

- Loverio, J. P., Chen, L.-H., & Shen, C.-C. (2023). Stakeholder collaboration, a solution to overtourism? A case study on Sagada, the Philippines. Tourism Geographies, 25(4), 947–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2021.2023209

- Maack, M., & Davidsdottir, B. (2015). Five capital impact assessment: Appraisal framework based on theory of sustainable well-being. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 50, 1338–1351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.04.132

- Mach, L. (2019). Surf-for-development: An exploration of program recipient perspectives in Lobitos, Peru. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 43(6), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519850875

- Mach, L. (2021). Surf tourism in uncertain times: Resident perspectives on the sustainability implications of COVID-19. Societies, 11(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030075

- Mach, L., & Ponting, J. (2018). Governmentality and surf tourism destination governance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(11), 1845–1862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1513008

- Mach, L., & Ponting, J. (2021). Establishing a pre-COVID-19 baseline for surf tourism: Trip expenditure and attitudes, behaviors and willingness to pay for sustainability. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 2(1), 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annale.2021.100011

- Machado, V., Carrasco, P., Contreiras, J. P., Duarte, A. P., & Gouveia, D. (2018). Governing locally for sustainability: Public and private organizations’ perspective in surf tourism at Aljezur, Costa Vicentina, Portugal. Tourism Planning & Development, 15(6), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2017.1415958

- Manero, A. (2023). A case for protecting the value of ‘surfing ecosystems’. NPJ Ocean Sustainability, 2(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-023-00014-w

- Manero, A., & Leon, J. (2021). The surfing historian in Surfonomics and the Noosa World Surfing Reserve with Ana Manero and Javier Leon. https://thesurfinghistorian.simplecast.com/episodes/surfonomics-and-the-noosa-world-surfing-reserve

- Margules, T., Ponting, J., Lovett, E., Mustika, P., & Pardee Wright, J. (2014). Assessing direct expenditure associated with ecosystem services in the local economy of Uluwatu, Bali, Indonesia. S. t. W. Coallition. https://www.savethewaves.org/wp-content/uploads/Bali_Surfonomics_Final%20Report_14_11_28_nm.pdf

- Marois, D. E., & Mitsch, W. J. (2015). Coastal protection from tsunamis and cyclones provided by mangrove wetlands – A review. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 11(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2014.997292

- Martin, S., & O’Brien, D. (2017). Surf resource system boundaries. In G. Borne & J. Ponting (Eds.), Sustainable Surfing (pp. 23–39). Routledge.

- Martin, S. A., & Assenov, I. (2014). Developing a surf resource sustainability index as a global model for surf beach conservation and tourism research. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(7), 760–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2013.806942

- McDonnell, S. (2021). The importance of attention to customary tenure solutions: Slow onset risks and the limits of Vanuatu’s climate change and resettlement policy. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 50, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.06.008

- McGregor, T., & Wills, S. (2017). Surfing a wave of economic growth (2206-0332). CAMA Working Papers, Issue. https://crawford.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publication/cama_crawford_anu_edu_au/2017-04/31_2017_mcgregor_wills.pdf

- McKenzie, R. J., Chambers, T. P., Nicholson-Perry, K., Pilgrim, J., & Ward, P. B. (2021). Feels good to get wet: The unique affordances of surf therapy among Australian youth. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 721238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.721238

- Mead, S. T., & Atkin, E. A. (2019). Managing issues at Aotearoa New Zealand’s surf breaks. Journal of Coastal Research, 87(sp1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI87-002.1

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends (Vol. 1). Island Press. https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.766.aspx.pdf