Abstract

In marking 400 years since the first enslaved Africans arrived to Jamestown, United States in 1619, the Ghana government through the Ghana Tourism Authority initiated the Year of Return 2019 (#YOR2019). The goal was to unite Africans in the diaspora with those on the continent, especially in Ghana, through a year-long calendar of commercial and commemorative slavery heritage tourism activities ranging from visits to slavery sites, healing ceremonies, theatre and musical performances, festivals, investment forums and relocation conferences. When a destination tourism product is rooted in a less-than-desirable past, how is ‘balance’ achieved between commercialization and commemoration? In exploring this conceptual question, we developed a methodological innovation utilizing the social media platform Twitter for data collection. Using a social media crawler coded in Python programming language, we scrapped tweets from the accounts of the Ghana Tourism Authority prior, during, and after the YOR2019 based on hashtag searches. After data cleaning, 1010 tweets were inductively analysed using NVIVO qualitative data analysis software. The findings revealed three emergent themes along a commodification-commemoration continuum: (1) the eventification and festivalisation of slavery heritage tourism, (2) celebrity co-production of YOR2019 experiences through social media and (3) pivoting from a predominantly slavery heritage destination to a destination that focuses on other touristic and business travel. Ultimately, YOR2019 marked a significant push by Ghana to move into a ‘Beyond the Return’ phase that pivots away from slavery heritage towards a more well-rounded tourism product for roots, leisure, and business travellers. The research established that commodification in slavery heritage tourism does not inherently destroy cultural meanings but provide new commemorative meanings for a new generation of Black travellers searching for more than just their roots.

Introduction

Ghana will use the year to bring together, more closely, people in Ghana and brothers and sisters in the Diaspora and establish herself as a true gateway to the Homeland for Africans in the Diaspora…We will build the knowledge that we are one African People…As every Muslim must visit Mecca at least once in their lifetime so we want to establish a pilgrimage to Ghana, one that every African in the Diaspora must undertake at least once in their life time. This pilgrimage will be the re-introduction of the Diasporan African to the homeland.

The late Jake Obetsebi-Lamptey

Former Ghanaian Minister of Tourism

At the opening of the Joseph Project in 2007

The African diaspora is constituted by a fluid unending process of being and becoming that is rooted in a collective consciousness of first origins on the African continent. Within the tourism space, this is anchored with travel back to the ‘homeland’, centered on the dispersal from the Transatlantic Slave Trade among others (Adu-Ampong & Mensah, Citation2023). This travel to a real and/or imagined ancestral homeland in search of one’s roots has been referred to as diaspora tourism, or roots tourism (Dillette, Citation2021a). Having been mobilised under terms such as Pan-Africanism, Garveyism and the Negritude movement, this type of tourism connecting Black travellers to their roots within the African continent termed as African diaspora travel, has a long existence (Zeleza, Citation2005) and varying motivation for each generation of Black travellers (Adu-Ampong & Mensah, Citation2023; Gebauer & Umscheid, Citation2021; Otoo et al., Citation2021; Yankholmes & McKercher, Citation2015). African countries, particularly those in West Africa have sought to style themselves as the true ‘homeland’ of the African diaspora due to the physical remains and traces of the slave trade in forts, castles, and dungeons. Therefore, in the case of diaspora tourism, we define a diaspora tourist as any visitor who has ancestral connections to a particular country or region, but no longer lives in the location, thereby making them a tourist (Cohen, Citation2022; Dillette, Citation2021a). Many countries have sought to attract the African diaspora to their specific tourist destinations such as the Gorée and Saint-Louis Islands in Senegal, the memorial landscape of Ouidah Museum of History, Fort of São João Batista da Ajuda, the ‘Door of No Return’ monument in Benin and the city of Badagry in Nigeria with its Heritage Museum and ‘Point of No Return’ monument. However, Ghana has been the most successful country with a long history of mobilising African diaspora roots tourism journeys (Hasty, Citation2002).

In Ghana, attempts to increase visitation from the global African diaspora can be traced from the Back-to-Africa movement in the early 1900s to the Joseph Project in 2007. More recently, following the United Nations 2013 declaration of the International Decade for People of African Descent, Ghana announced 2019 as the Year of Return (YOR2019) for global citizens of the African diaspora. Commemorating the 400th year since the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade, this YOR2019 would bring a year-long schedule of events, activities and festivals centered around slavery heritage and ancestral reconnection to attract visitors to the country. Marketed heavily towards African Americans using Social Media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, the YOR2019 would prove to be one of the country’s most successful ‘return’ movements. Speaking on the floor of the Ghana’s Parliament in early 2020, the then Minister of Tourism, Arts and Culture noted that international arrivals reached 1.13 million in the year ending 2019, representing a 27.92% change over the year 2018. Furthermore, in the 2019 Tourism Report by the Ghana Tourism Authority and the Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture, it was noted that this 1.13 million arrivals injected an estimated $3.3 billion into the economy (Ghana Tourism Authority, Citation2021). While the arrivals and receipts figures are disputed to have been overestimated (Simons, Citation2019), what is clear is that the YOR2019 generated unprecedented increase in tourist arrivals to Ghana. Nonetheless, while tourism and event-oriented heritage campaigns have been the medium of mobilising the collective consciousness and travel desires of the African diaspora, questions of the inherent tensions between commemoration and commodification come into play.

As critical scholars, we must consider whether the commemoration of such a horrific time period in history through tourism lends itself more to commodification rather than an authentic revisiting of a troubled past. Though pilgrimagesFootnote1 back to Africa have received attention in the academic literature, (Bruner, Citation1996; Dillette, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Mensah, Citation2015; Mowatt & Chancellor, Citation2011; Reed, Citation2010; Yankholmes & Akyeampong, Citation2010; Yankholmes & Timothy, Citation2017) and the role of social technologies in transatlantic Blackness has been explored (Boukhris, Citation2017) few studies have specifically explored the tensions between commemoration and commodification within slavery heritage tourism and how this is resolved. The core of this is about how much commodification is required and/or needed for meaningful commemorative practices. Thus, while tension does exist, commemoration and commodification are not mutually exclusive but can be understood as having various intersections along a continuum. Therefore, this study seeks to begin an exploration into whether or not it is possible to mourn, commemorate and celebrate an enslaved past within the marketing of the YOR2019 events and festivals. Consequently, for this paper we utilise the social media platform Twitter as an innovative approach for data collection to explore how Ghanaian tourism authorities portrayed the YOR2019 in treading the delicate balance between commemorating an enslaved past while celebrating the current reunification of African diasporas with their homeland. In line with the focus of the special issue of ‘Unpacking Black Tourism’, which this work is a part of, we extend previous research on slavery heritage tourism in Africa by adding depth and breadth to understanding the destination perspective as they provide the tourism experience for a new generation of Black travellers.

Commemoration, commodification and slavery heritage tourism in Ghana

Commemoration as the act of remembering and marking the past through memorials, events, celebrations and other ceremonies involves a selective use of history and public memory. This reifies the past through a time-space compression where certain sites continue to evoke a tangible link to the past and to contemporary issues (Foote & Azaryahu, Citation2007) through cultural (re)productions such as festivals, memorial day, regularized visitations and other tourism-oriented events. It has been argued that ‘tourism turns culture into a commodity, packaged and sold to tourists, resulting in a loss of authenticity’ (Cole, Citation2007, p. 945) and that commodification is a ‘process by which things (and activities) come to be evaluated primarily in terms of their exchange value, in a context of trade, thereby becoming goods (and services)’ (Cohen, Citation1988, p. 380). This is because to attract visitors, the public memory and sites associated with slavery heritage are packaged for touristic consumption. Thus to commemorate is to commodify since the traces of the past need to be transformed into accessible form for public engagement. This raises the issue of how much commodification is required and/or needed in commemorating the public memory of the past. The commodification process raises questions about whether or not the brutal history of the transatlantic slave trade should be sold (commemorated) in this way. While commodification has traditionally been associated with private sector and individual tourist practices (Shepherd, Citation2002), the development of slavery heritage tourism in Ghana shows the significant role of the state in institutionalizing the commodification process as it seeks for commemoration (Hannam & Offeh, Citation2012).

In pursuing visitations from African diasporas, Ghana uses various state sponsored commemorative events—i.e. institutional commodification. This is a process in which national state agencies and international development agencies directly contribute to the acceleration of the cultural (re)productions for tourist consumptions through technical, financial and marketing assistance (Hannam & Offeh, Citation2012). While a detailed overview of the general evolution of diaspora tourism and slavery heritage tourism is beyond the scope of this paper (for an overview see: Adu-Ampong & Mensah, Citation2023; Cohen, Citation2022; Yankholmes, Citation2023), what is clear is that the state plays a key role in defining this form of tourism development. Thus, the state leads in structuring the processes through which the commodification of commemoration occurs in turning the public memory of slavery heritage into replicas, imaginaries, invented or contrived places, people and events (Timothy & Boyd, Citation2003). However, commemoration and commodification are not mutually exclusive but can be seen as the ends of a continuum. As Cohen (Citation1988, p. 383) rightly notes, commodification does not destroy the meaning of cultural products, neither for the locals nor for the tourists…old meanings do not thereby necessarily disappear, but may remain salient on a different level for an internal public, despite commodification. In the current context, this process is seen in how the political underpinning of earlier African diaspora travel has shifted from wider structural politics to an individual politics of identity based on a ‘back-to-Africa’ leisure experience. This shift reflects a new generation of diasporan African whose travel motivation have undergone enormous changes (Cohen, Citation2022; Dillette, Citation2021b; Otoo et al., Citation2021; Yankholmes & McKercher, Citation2015).

The making of Ghana as the ‘Mecca’ of African diaspora travel has strong political beginnings starting with the ‘Back-to-Africa’ movement initiated by Chief Alfred Sam in 1914 followed by Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association in the early 1920s with a message of universal Black nationalism and eventual return of all people of African descent back to the African continent (Benton & Shabazz, Citation2009). These ideas found new expression during the period of Ghana’s independence in 1957 when Kwame Nkrumah’s ambition for Pan-Africanism facilitated transatlantic mobility of Black people, ideas and politics. However, the overthrow of Nkrumah’s government in 1966 marked a change in the underlying logic of Ghana’s positioning in transatlantic travel.

The political instabilities following Nkrumah’s overthrow meant reduced transatlantic travel of the African diaspora with a semi-passive role of the Ghanaian state in developing diaspora tourism (Adu-Ampong, Citation2019). Much of the longing for roots tourism during this period therefore developed internally in the United States. Unlike the earlier transatlantic travel of the ‘Back-to-Africa’ movement, this roots inspired travel was underpinned by the politics of individual identity (Dillette, Citation2021b). At the beginning of the 1980s, Ghana was rediscovered as home for African diaspora travel when tourism emerged as an effective economic diversification strategy. It was here that Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanist ideologies intersected with economic realities to necessitate the emergence of slavery heritage tourism for fostering economic development (Adu-Ampong, Citation2019; Engmann, Citation2021). The designation of former European slave castles and forts in Ghana as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1979 initiated the touristic place-making and development of these sites as memorial attractions for African diaspora travellers (Schramm, Citation2007).

After a Ministry of Tourism was established in 1993, a 15-year National Tourism Development Plan (1996–2010) was developed where the African Diaspora, in particular African Americans, were identified as a prime market for slavery heritage tourism. In the mid-1990s, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) financed the restoration of the Cape Coast and Elmina Castles enabling the marketing of Ghana’s slavery heritage through a co-constituted process of construction and meaning-making of Ghana as the homeland for African diasporas (Bruner, Citation1996). In 1998, Emancipation Day celebrations were introduced into the Ghanaian heritage tourism calendar which in combination with the already existing Pan African Historical Theatre Festival (PANAFEST) have served as the fulcrum of a tourism-oriented series of heritage tourism events organized by the state to attract the African diaspora (Adu-Ampong, Citation2019). Since the turn of the millennium, there’s been focused efforts in reframing the country as the ‘Black Star’ of Africa. As part of the 50th Independence celebrations in 2007 under the theme of ‘Championing African Excellence’, ‘The Ghana Joseph Project’ was launched by the then Ministry of Tourism and Diaspora Relations. This project framed Ghana as the natural aspiration for African pride and the gateway to the homeland drawing on Pan-Africanist discourses and the touristic place-making of slavery heritage sites. It is in this historical context that the YOR2019 Ghana initiative emerged.

The #YearofReturn 2019, Black travel and social media

On 28 September 2018, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo officially proclaimed and launched the ‘Year of Return, Ghana 2019’ (YOR2019) under the theme of ‘Celebrating 400 Years of Resilience’ at the National Press Club in Washington DC, United States. Among the audience were Pan African advocates, business leaders, political representatives, dignitaries and media representatives among others. The main purpose of this declaration was to commemorate the 400th anniversary of when the first 20 West African enslaved persons from Ghana arrived by ship in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619. While transatlantic slavery existed prior to this date and involved shipment also to Europe, South America and the Caribbean, the choice of 1619 as starting point was strategic. First, the YOR 2019 found its origin in ACT H.R. 1242 − 400 Years of African-American Experience—which was passed by the United States Congress in 2018 to commemorate the first recorded arrival of enslaved Africans. There is also a bias favouring the ‘Black Atlantic’ and the African-American experience in slavery history and heritage research (Zeleza, Citation2005). Moreover, African-Americans represents the most prominent and lucrative market-segment for Ghana’s slavery heritage tourism product. The YOR 2019 initiative involved a year-long calendar of activities ranging from visits to slavery heritage sites, healing ceremonies, theatre and musical performances, festivals, lectures, investment forums and relocation conferences aimed primarily at the African-American market. The aim was to promote Ghana as a high-profile tourism and business destination ripe for visits, investment and re-migration of African diasporas to the homeland (Nielsen & Riddle, Citation2009). The promotional efforts were spearheaded by the Office of Diaspora Affairs at the Office of the President of the Republic of Ghana and coordinated by the Ghana Tourism Authority (GTA) to ‘unite Africans on the continent with their brothers and sisters in the diaspora’ (VisitGhana, Citation2019).

In sync with this effort from the Ghana Tourism Authority, energy in the United States around the ‘Black Travel Movement’ (BTM) was growing (Dillette et al., Citation2019). Steeped in counter narratives of storytelling through social media, the BTM has provided the platform for a multitude of companies and organisations focused on Black travel to succeed. Each of these organisations have dedicated themselves to promoting and providing travel opportunities for Black people around the globe, and in many cases, opportunities for diasporic travel back to Africa, creating a safe space for African diasporas to explore their roots (Dillette, Citation2021b). This movement has served as a major supporter of West African countries like Ghana seeking to encourage more African American visitors to the country. Utilising social media platforms to create awareness and community around Black Travel, the movement has managed to gain significant momentum over the years. Arguably, the underlying motivation for African diaspora root tourism is changing (Boone et al., Citation2013; Otoo et al., Citation2021; Yankholmes & McKercher, Citation2015). While the search for identity and connection with one’s roots remains, the experiential preferences have expanded beyond simple visits to slavery related sites. The rise of the experience economy has meant that African diaspora roots tourists are also looking for engagement with wider socio-cultural heritage on the continent that can be offered through events and festivals that lend themselves to wide sharing on social media. It is this changing dynamic in Black Travel that the YOR2019 sought to tap into.

The YOR2019 relied on an intricate meshing of economic purposes of the Ghanaian state under an attendant capitalist logic of commercialisation framed by the rhetoric of Pan-African ideologies of African unity and resilience - all embedded in the historicity of the slave trade. The YOR2019 shows a clear break in terms of its underlying logic as it utilised a social media marketing campaign to publicise events. Social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram became the biggest channels of communication and marketing. African Americans who are very well represented on these platforms, were invited to be co-producers of the experiences. Social media platforms work on a follower-logic and so the YOR2019 online marketing campaign was built in part on the social media activities of African American celebrities with thousands and millions of followers travelling to Ghana and sharing their experiences across social media (Gebauer & Umscheid, Citation2021). The official Twitter profiles of the Ghana Tourism Authority, the Year of Return office and Visit Ghana Now were active throughout 2019 sharing multiple posts and (re)tweets on a daily basis. The question is to what extent their tweets reflect the Pan-Africanist ideas meshed with the commercial logics of a tourism marketing campaign that is pivoted on Ghana’s slavery heritage? And, how did the touristic marketing of slavery heritage achieve a balance between commemoration and commodification? To further explore the issues outlined above in more depth, this paper focuses on state public sector agencies’ engagement of the YOR 2019 through Twitter to answer the research question: To what extent did Ghana’s tourism agencies balance commemoration vs. commodification in the marketing and representation of the YOR 2019?

Methodology

The rise of social media has changed many facets of society including how sensitive aspects of the past are commemorated. In line with this, we utilised the social media platform Twitter for data collection. Twitter was specifically chosen above other social media platforms because it was the main platform used by the Ghana Tourism Authority to share about the Year of Return 2019. Additionally, Twitter was used as it is known metaphorically for the undefined, but very palpable online space known as Black Twitter which acts as a space to share stories and experiences of Black people globally, including the experiences of travelling while Black (Dillette et al., Citation2019). All the Twitter data used in this study are related to the Year of Return 2019 and were collected with a social media crawler coded in Python programming language, which exploits the Twitter public API. This retrieval process yielded 45,898 tweets that were based on the occurrences of specific hashtags - #yearofreturn, #yearofreturn2019, #yor, #yor2019, #beyondthereturn—and tweeted between 1 January 2018 − 31 December 2020. We then applied a filtering criteria of selecting only English language tweets which brought the total number to 39,066 tweets. On the basis of our research goal of exploring how Ghanaian tourism authorities portrayed the YOR2019, we applied another filtering criteria to the data and selected tweets from three specific handles administered by the Ghana Tourism Authority—@VisitGhanaNOW @GhanaTourismTA and @Yearofreturn. This resulted in a final dataset of 1010 tweets which was then extracted as an Excel file into NVIVO for analysis. As Highfield et al. (Citation2013, p. 322) has succinctly noted, ‘…no retrieval methods guarantee a comprehensive capture of Twitter data…such research nonetheless remains valid and important’.

Analysis of the data using NVIVO—a qualitative text mining software—followed an emergent thematic coding method through an inductive approach. Utilizing an inductive approach meant the data drove the themes that were identified, rather than a priori themes being used to fit the data (Saldana, Citation2015). Although commemoration and commodification were used as an overarching framework, they do not prescribe specific a priori themes. Each tweet within the dataset was analysed separately to establish credibility and dependability (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Based on separate analysis by each author, we developed an initial list of raw codes based on tweets within the data. After this, we discussed each code and how they related and diverged from each other, thus developing an initial list of six major themes, each encompassing multiple codes. This process led to a codebook linking themes, codes, and tweets together which helped to establish confirmability within the data (Nowell et al., Citation2017). Each theme was given a definition helping to ensure trustworthiness. This process was iterative, including many rounds of discussion and a search for confirming and disconfirming evidence. After three iterative rounds, a final decision on three major themes to represent the data was made (see below).

Table 1. Overview of themes in relation to sample tweets and sample in-vivo codes.

Findings

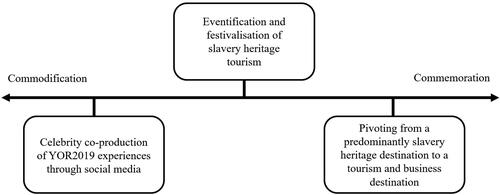

The iterative analysis of the data identified three major emergent themes: (1) the eventification and festivalisation of slavery heritage tourism, (2) celebrity co-production of YOR2019 experiences through social media and (3) pivoting from a predominantly slavery heritage destination to a destination that focuses on other touristic and business travel. In further analysing these themes, we aligned these emergent themes with the major construct of commemoration and commodification which we consider as the ends of a continuum in which our emergent themes exist in various shades of commemoration mixed with commodification and vice versa. Below is an illustration that clarifies how our emergent themes move along this continuum ().

In the following sections, we provide an overview of findings under each emergent theme.

The eventification and festivalisation of slavery heritage tourism

This theme refers to the emphasis within the YOR2019 initiative on the production, promotion and consumption of Ghana as the homeland of the African diaspora through myriad events and festivals. The YOR2019 was set up as a yearlong series of events and festivals through which visitors could commemorate the occasion of the 400-year anniversary of the first enslaved Africans from Ghana arriving in Virginia, United States. In addition to state-led initiatives, event and festival proposals were also elicited from the public, endorsed, and included in the YOR2019 calendar of events:

The steering committee of the Year of Return, Ghana 2019 has announced a call for event organizers to submit proposals for endorsement and inclusion in the calendar of events to celebrate the year-long campaign. #YearOfReturn #YearOfReturnGhana2019. - @GhanaTourismTA: 15 Nov 2018

Are you ready? This is the official list of #YearOfReturn endorsed events under the auspices of @ghanatourismGTA and @motacghana in partnership with diasporaaffairs.ghana . . Plan your holiday season in Ghana!! https://t.co/3bHDhYUxss. – @Yearofreturn: 14 Nov 2019

While the excessive eventification and festivalisation might appear as an outright commodification, analysis of the tweets shows there was a clear awareness of the deeper and lighter meanings to be associated with certain events. Events such as PANAFEST and Emancipation Day celebrations were seen as prime commemorative moments in which the deeper meanings of the YOR2019 were realised. Thus, while such events were limited in number, the tweets on these provided deeper explanations and connections to slavery heritage as exemplified below:

2019 marks the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans in #Jamestown, Virginia, USA. Ghana was a major hub during the transatlantic slave trade & to commemorate this, declared the year as "Year of Return". #yearofreturn #Ghana2019 #brafie https://t.co/RWWu8uhW4n – @GhanaTourismTA: 4 Nov 2019 ()

Today our team was in Assin Manso with the Prime Minister of #Barbados to bury the remains of an unknown enslaved #African. This is the deeper meaning when it comes to #YearOfReturn https://t.co/eumT5al1ZR – @GhanaTourismTA: 14 Nov 2019

Bakatue Festival is celebrated by the chiefs and peoples of Elmina in the Central Region. This year’s celebration marked 500 years of the festival and also celebrated as part of activities marking #YearOfReturn #Ghana2019 #Bakatue2019 #EdinaBakatueFestival https://t.co/Ig6N6RrQjg – @GhanaTourismTA: 4 July 2019

Damba festival is a thanksgiving festival and a time for families to meet and socialize as well as evaluate the past and plan for the future. Join us this weekend for the #Dambafestival2019. Photo: Douglas Frimpong #FeelGhana #YearOfReturn2019 #iLoveGhana #africa #travel #tamale https://t.co/bFW8ax1rc9 – @GhanaTourismTA: 1 Nov 2019

From where the #Volta #River meets the #Atlantic #Ocean we present to you the #Asafotufiami #festival Asafotufiami is a war Festival that commemorates the heroic achievements of our ancestors. #SeeGhana #EatGhana #WearGhana #FeelGhana #Yearofreturn #Ghana2019 #Asafotufiam2019 https://t.co/0YzV9ZJkTS – @GhanaTourismTA: 3 Aug 2019

Take part in the ongoing yoyotinzfestival @yoyotinz Ghana’s first festival that celebrates hip hop music and its This evening will be the featured film screening at @af_accra at 6pm. #yearofreturn #filmscreening… https://t.co/dupKeTuvkk – @Yearofreturn: 11 Oct 2019

Don’t miss the FIRST ever Waxprint festival in Africa, only at Wax Print Fest from 15-22 June! #YearOfReturn #Ghana2019 #Brafie #LetsGoGhana…#waxprintfest #waxprintfilm #waxprint #africanprint #africanfilm #ankara #africatotheworld – @GhanaTourismTA: 24 April 2019

Celebrity co-production of YOR2019 experiences through social media

Early on in analysing the dataset, the theme of ‘celebrity co-production of YOR2019 experiences through social media’ revealed itself. This theme references the strategy of using the status of celebrities to market YOR2019. This highlights the intersection between heritage tourism and popular culture, and utilizing celebrities as co-producers allowed YOR2019 to infiltrate a market they otherwise may not have had access to. This theme included tweets about celebrity experiences visiting Ghana, attending YOR2019 events and calling on Black people to visit Ghana.

One of the initial introductions of celebrity co-production was during the inaugural Full Circle Festival in December 2018. The ESSENCE Full Circle Festival (EFCF) is an ‘exclusive, invitation-only experience to commemorate the Year of Return, honour our common heritage and to celebrate our African ancestry, culture and achievement in the beautiful, vibrant country of Ghana’. (https://www.essencefullcirclefestival.com/, 2022). Numerous tweets highlighted this festival and the various celebrity attendees, some of whom had traditional chieftaincy titles bestowed on them, as referenced in the tweet below about African American Actor Michael Jai White.

The Full Circle Festival by the Hollywood Stars saw them visit #Akwamufie where The Real Michael Jai White was enstooled as a chief. Flashback video by Pulse Ghana. #seeghana #EatGhana #WearGhana #FeelGhana #visitghana #yearofreturn #ghana2019 https://t.co/xRs7ItLyBj @GhanaTourismTA: Jan 7 2019

Based on the data, it can be assumed that this festival, along with the focus on marketing the celebrities who attended it was highlighted to create a ‘buzz’ at the beginning of YOR2019. The fact that the festival itself was an invitation only event created a mentality of scarcity and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) around YOR2019 encouraging others in the diaspora to make the move to visit Ghana. The festival was also shared across American TV outlets such as The View ABC and The Real Daytime.

Other examples of co-produced celebrity tweets included mentions of Actor and singer Danny Glover and Actress AJ Johnson who participated in YOR activities.

Danny Glover and 250 other African Americans arrive in Ghana after calling on blacks to visit Ghana. Follow us on facebook for live coverage. #Yearofreturn #ghana2019 https://t.co/8lOtoAeAfO @GhanaTourismTA: Aug 20 2019

The Hollywood star @THEAJZONE arrived yesterday to participate in this year’s PANAFEST/EMANCIPATION celebrations. Join us at the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park at 10:30am as we lay wreaths to commemorate our #emancipation. #yearofreturn #ghana #letsgoghana #brafie #ghana2019 https://t.co/RRiYH1n5sz @GhanaTourismTA: July 24 2019

These co-produced marketing tweets created a FOMO among African Americans on social media, driving the high level of engagement with the YOR2019 online. However, there is no way to tell exactly how many visitors subsequently embarked on a trip to Ghana on the basis of this celebrity co-production.

An illustrative example of celebrity co-production was a video of Steve Harvey, a Black American Entertainer, shared by Visit Ghana. To date, this video has been viewed almost 700,000 times.

Our video of @SteveHarveyFM gained so much attention in #Ghana. Here’s more from our coverage of his visit. #yearofreturn #visitGhana #diaspora #africanculture #culture #travelnoire #heritage #tourism #blackandabroad https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pe3eJnFuV3s @Yearofreturn: Aug 16 2019

Entitled ‘Year of Return: Ghana is home—Steve Harvey’, the video itself recounts Steve’s visit to Ghana during YOR2019. He emotionally shares I don’t think people understand how it feels for a lot of African Americans to come home to a place you’ve never been. I think every African American should experience this for their own soul. The first time I came here I couldn’t stop crying because I had come to a place called home where I had never been and I felt robbed. Coming from a celebrity that connects with multiple generations of Black Americans, this endorsement by Steve Harvey reached a plethora of audiences. Towards the end of the video, he goes on to share now we’re doing some business over here, we are going to create some opportunities. This mention reflects the changing motivation of Black travellers and ties into the final theme of our findings.

Pivoting from a predominantly slavery heritage destination to a destination that focuses on other touristic and business travel

While the basis for the YOR2019 initiative was the varied geographies of slavery heritage sites in Ghana, there was very limited engagement with these sites in the dataset. The commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the arrival of enslaved Africans to Jamestown, Virginia in the United States as the principal grounding for the initiative is evident in a limited number of tweets. However, due to the low saturation of such tweets and an oversaturation of tweets on other tourism sites, it appears that a goal of YOR2019 was to shift the conversation about Ghana as a slavery heritage tourism destination towards Ghana as a widely sought after tourism destination with diverse attractive features. Analysis of the dataset shows that the YOR2019 pivoted away from an (over)emphasis on slavery heritage to showcasing the rich diversity of tourism assets of Ghana to the African diaspora. The YOR2019 was not simply about commemorating the resilience of the African diaspora but also about promoting Ghana as the prime tourism and business destination for roots pilgrimages, touristic visits, investment and re-emigration of the African diaspora to the homeland. It appears that there was an intentional effort in making the YOR2019 open to individual interpretation and co-creation of experience:

The words ‘Year of Return’ put together ignites different memories for many. From journey to the motherland, business opportunities, citizenship dream to statements like "Never Again", "We Have Returned" or even "Ghana Is Home". How has #YearOfReturn #Ghana2019 been for you? https://t.co/S6hTeBn2M6 - @GhanaTourismTA: Dec 30 2019

@AMDWIN1 #YearOfReturn marked the 400-year anniversary of the documented ship of enslaved #Africans that arrived in Virginia on Aug 20th, 1619. Next year is no longer a 400-year anniversary. But we know people have embraced returning to Africa. 2020 starts new campaign "Beyond the Return" – @Yearofreturn: Nov 27 2019

In this #YearOfReturn #Ghana2019, Opportunities for investment in #Ghana and #Africa abound as outlined by Prof. Kwame Addo in when outdooring his resource map… #Brafie #LetsGoGhana #Africa #TourAfrica #SeeGhana #FeelGhana https://t.co/lx1g45V1f2 via @VisitGhanaNOW: May 21 2019

Braxton Jones traveled to Ghana to learn more about its history. He came away with a love for the culture, warmth and rhythm of our people. In partnership with @greatbigstory @yearofreturn @VisitGhanaNOW. #BeyondTheReturn #VisitGhanaNow #YearOfReturn https://t.co/eWgqDZpFJE @GhanaTourismTA: Dec 23 2019

Tourism and @yearofreturn Ambassador @sarkodie shares his thoughts on the Year of Return, #Ghana2019 as we prepare to go #BeyondTheReturn #Ghana2020. Catch him at #TINAFest2020 #kentefestival at @LabadiBeach this evening. @tinafestival_gh . #visitGhanaNow #YearOfReturn https://t.co/EoiHoXpOdt @GhanaTourismTA: Jan 3 2020

As we prepare for #Ghana #BeyondTheReturn here’s how our team summarised the #YearOfReturn #Afrochella2019 Cultural Festival. #Ghana2020 #VisitGhanaNow #Brafie #LetsGoGhana https://t.co/8mDZn0Frb6 @GhanaTourismTA: Jan 28 2020

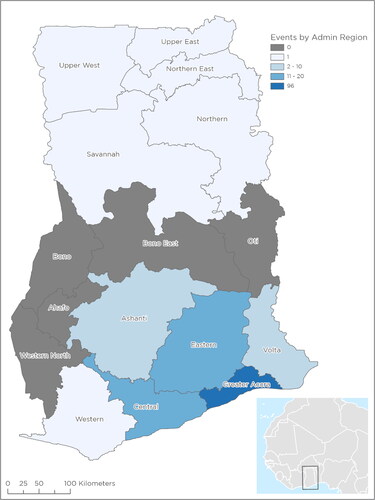

Furthermore, several tweets were framed as a travel guide providing details on the geographies of attraction sites across the country as exemplified below:

Today we explore the Bono region which is home to the Bui National park and dam site, the beautiful Nchiraa Waterfalls and the Mausoleum of late Prime Minister Prof. K.A. Busia. Learn more: https://t.co/VTcidTHDML #VisitGhanaNow #BeyondTheReturn #Ghana2020 #tuesdaythoughts - @GhanaTourismTA: Sept 15 2020

Avu -Lagoon -Xavi watery landscape is home to the world’s only #aquatic #antelope: the Sitatunga. In all of #Ghana, and the only location where these majestic creature still remains. #SeeGhana #FeelGhana #AvuLagoonXavi #YearOfReturn #Ghana2019 #Brafie https://t.co/ISbiF2ThrH - @GhanaTourismTA: May 7 2019

Discussion and conclusion

The development of tourism around slavery heritage is considered contentious because of the key questions around ethics and the risk of over commercialisation of a painful past (Bruner, Citation1996; Engmann, Citation2021). The conceptual knot here is how to commemorate a sensitive past without overly commodifying, and even trivialising this past through commercialisation that lead to a loss of meanings. In this paper we explored how the Ghanaian tourism authorities portrayed the YOR2019 in treading the delicate balance between commemorating an enslaved past while celebrating the current reunification of African diasporas with their homeland. We found that in the case of the YOR2019 campaign, it remained deeply entrenched within a capitalist structure, in particular advances in social media platforms and technologies, that is tied to a complex set of norms and meanings. Paradoxically, the commodification of slavery heritage tourism is based on a system that was historically the commodification of people through the transatlantic slave trade (Engmann, Citation2019). Thus to develop slavery heritage tourism in Ghana, the brutal history of the transatlantic slave trade had to be commodified. Visits to the forts and castles as material representation of the embodiment of enslavement, death and suppression had to be touted as ‘sellable’.

Our findings indicate that notwithstanding its inherent tensions in achieving a balance, this institutional commodification process (Hannam & Offeh, Citation2012) led by the state did not inherently destroy the meanings of slavery heritage. Instead, the multitude of events and festivals surrounding the YOR2019 provided new meanings for a new generation of Black travellers in search of more than just the commemoration of slavery. It was therefore possible to mourn, commemorate and celebrate an enslaved past within the marketing of the YOR2019. Thus, from a conceptual perspective we argue that commemoration and commodification are mutually constituted and the ends of a continuum rather than being mutually exclusive categories (Gebauer & Umscheid, Citation2021). As Cohen (Citation1988) has argued, despite commodification, old and new meanings of cultural heritage remain salient at different levels for different stakeholders. In this lens, we can see that the YOR2019 offered a range of events, festivals and activities along this continuum to cater for visitors looking for deeper engagement and those with an interest in other forms of engagement. This reflects an ongoing contemporary increase in the organisation of local festivals in Ghana as identified by Adongo and Kim (Citation2018). Thus, while the eventification and festivalisation of the YOR2019 tended toward commodification, one can also see this as a destination providing a service that caters to the range of experiences sought by the diverse and changing preferences and travel motivations of the African diaspora (Cohen, Citation2022; Otoo et al., Citation2021).

The ‘new’ African diaspora traveller have significant preferences shaped by social media and the modern Black travel movement. The Black travel movement have effected significant shifts in preferences in African diaspora travel (Dillette, Citation2021a) away from a singular focus on roots tourism to an expanded roots-inspired touristic leisure and recreation travel motivations. From a practical standpoint, within this space, organizations like Tastemakers Africa curate trips to the continent and host events like the ‘Ghana real estate tour’ to continue encouraging African diasporas to visit and invest in the continent. Black travellers are increasingly in search of more contemporary and futuristic African experiences and connections when they visit. Conceptually, we may argue that African disapora tourism to Ghana has moved away from identity formation to identity confirmation and expression for people of African descent. Identity formation revolve around traditional roots tourism of connection focused on slavery heritage while identity confirmation and expression revolve around the search for touristic experiences in line with an already affirmed Black traveller identity (Dillette, Citation2021a). Seen in this light, our findings about the eventification and festivalisation of the YOR2019 therefore represents a direct response to these changing preferences. By curating a set of events and festivals with varying degrees of connection to slavery heritage, a new pivot of destination framing was made in which the overall general social, economic, cultural and physical heritage of Ghana becomes the draw card. The YOR2019 entailed reaching back to the Pan-Africanist ideals of Nkrumah infused with modern sensibilities and the taste preferences of contemporary African diasporas. Thus, the YOR2019 can be touted as a launching off point that Ghana utilized to rebrand itself as a destination for all travellers, not just those in the diaspora or those interested in slavery heritage. Between the numerous events and offerings associated with YOR2019, Ghana was able to showcase its diverse physical landscape, cultural offerings and economic investment options. Our finding about the social media co-creation and co-curation of the YOR2019 travel experiences by African American celebrities shows how this aided the pivoting to showcase the diversity of the tourism offer in Ghana.

In drawing on the innovative use of Twitter as data source, this research investigated the conceptual question of the relationship between commemoration and commodification in slavery heritage tourism through the case of the YOR2019 initiative in Ghana. We also explored the making of Ghana as the ‘mecca’ of the African diaspora and how this relates to the changing motivations underlying the Black travel movement. By unpacking the institutional commodification of the YOR2019 through the analysis of tweets from Ghanaian tourism authorities, we identify how the changing slavery heritage tourism practices line up with the changing preferences of diaspora African. Practical implications for the Ghana Tourism Authority are grounded in the eventification and festivalisation of slavery heritage tourism as seen in the YOR2019 which point to the ways commemoration and commodification are mutually constituted without inherently destroying meanings. Moving ahead, the GTA should follow similar guidelines to ensure a fine balance is achieved when continuing to expand the Ghanaian tourism product, while memorialising its heritage. Strong linkages to history and community will be paramount in this new pivoting process.

There are however certain limitations in our study design in terms of the state-centric and supply side view we take. An analysis of tweets from diaspora Africans and/or the general public in relation to the YOR2019 on the demand side would offer additional insights worth exploring in future research. Future research can also explore through interviews the extent to which Ghana tourism policy makers are actively working towards a new pivot of destination framing as identified in our analysis. Notwithstanding the limitations, the findings from this study provides both conceptual and empirical contributions to the commemoration-commodification debate in slavery heritage tourism while outlining the emergence of new meanings of slavery heritage tourism driven by contemporary aspirations of Black travellers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong

Dr. Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong is an Assistant Professor at the Cultural Geography group at Wageningen University and Research, the Netherlands and a Senior Research Associate at the School of Tourism and Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. He currently holds a Dutch Research Council (NWO) Veni Grant (VI.Veni.201S.037) researching on the geographies of slavery heritage tourism in the Ghana-Suriname-Netherlands triangle. His other research interests are on sustainable tourism development, tourism policy and planning, cultural heritage management, and innovations in qualitative research methodologies.

Alana Dillette

Dr. Alana Dillette is the Co-Director of Tourism RESET and an Assistant Professor of Hospitality and Tourism Management at San Diego State University. Dr. Dillette conducts research that explores the intersection between tourism, race, gender & ethnicity. Her work has been published in numerous top-tier peer reviewed journals as well as in travel industry publications such as AFAR Media. More specifically, she is working on research to gain a better understanding of the Black travel experience in addition to the challenges faced by Black hospitality and tourism professionals.

Notes

1 Pilgrimage: In the case of this work, pilgrimage refers to journeys of the African diaspora to visit geographic locations they consider to be tied to their ancestral heritage.

References

- Adongo, R., & Kim, S. (2018). The ties that bind: Stakeholder collaboration and networking in local festivals. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(6), 2458–2480. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2017-0112

- Adu-Ampong, E. A. (2019). Historical trajectories of tourism development policies and planning in Ghana, 1957–2017. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1537002

- Adu-Ampong, E. A., & Mensah, I. (2023). African Diaspora Tourism: Concepts, issues and prospects beyond slavery-oriented heritage. In D. Timothy (Ed.), Cultural heritage and tourism in Africa(pp. 184-199). Routledge.

- Benton, A., & Shabazz, K. Z. (2009). “Find their Level”. African American roots tourism in Sierra Leone and Ghana. Cahiers D’études Africaines, 49(193–194), 477–511. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.18791

- Boone, K., Kline, C., Johnson, L., Milburn, L. A., & Rieder, K. (2013). Development of visitor identity through study abroad in Ghana. Tourism Geographies, 15(3), 470–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.680979

- Boukhris, L. (2017). The Black Paris project: The production and reception of a counter-hegemonic tourism narrative in postcolonial Paris. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(5), 684–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1291651

- Bruner, E. M. (1996). Tourism in Ghana: The representation of slavery and the return of the black diaspora. American Anthropologist, 98(2), 290–304. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1996.98.2.02a00060

- Cohen, E. (1988). Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 15(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X

- Cohen, R. (2022). Global diasporas: An introduction (25th Anniversary edition). Routledge.

- Cole, S. (2007). Beyond authenticity and commodification. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 943–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.05.004

- Dillette, A. (2021a). Black travel tribes: An exploration of race and travel in America. In C. Pforr, R. Dowling, & M. Volgger (Eds.), Consumer tribes in tourism(pp. 39-51). Springer.

- Dillette, A. (2021b). Roots tourism: A second wave of double consciousness for African Americans. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2–3), 412–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1727913

- Dillette, A. K., Benjamin, S., & Carpenter, C. (2019). Tweeting the black travel experience: Social media counternarrative stories as innovative insight on# TravelingWhileBlack. Journal of Travel Research, 58(8), 1357–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518802087

- Engmann, R. A. A. (2019). Ghana’s Year of Return 2019: Traveller, tourist or pilgrim? https://theconversation.com/ghanas-year-of-return-2019-traveler-tourist-or-pilgrim-121891

- Engmann, R. A. A. (2021). Coups, castles, and cultural heritage: Conversations with Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings, former President of Ghana. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16(6), 722–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1817929

- Foote, K. E., & Azaryahu, M. (2007). Toward a geography of memory: Geographical dimensions of public memory and commemoration. Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 35(1),125–144.

- Gebauer, M., & Umscheid, M. (2021). Roots tourism and the Year of Return campaign in Ghana: Moving belonging beyond the history of slavery. In J. Saarinen & J. M. Rogerson (Eds.), Tourism, change and the global south (pp. 123–134). Routledge.

- Ghana Tourism Authority. (2021). 2019 tourism report. https://visitghana.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Ghana-Tourism-Report-2019-min.pdf

- Hannam, K., & Offeh, F. (2012). The institutional commodification of heritage tourism in Ghana. Africa Insight, 42(2), 18–27.

- Hasty, J. (2002). Rites of passage, routes of redemption: Emancipation tourism and the wealth of culture. Africa Today, 49(3), 47–76. https://doi.org/10.1353/at.2003.0026

- Highfield, T., Harrington, S., & Bruns, A. (2013). Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom: The# Eurovision phenomenon. Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), 315–339.

- Mensah, I. (2015). The roots tourism experience of diaspora Africans: A focus on the Cape Coast and Elmina Castles. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 10(3), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2014.990974

- Mowatt, R. A., & Chancellor, C. H. (2011). Visiting death and life: Dark tourism and slave castles. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1410–1434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.012

- Nielsen, T. M., & Riddle, L. (2009). Investing in peace: The motivational dynamics of diaspora investment in post-conflict economies. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(S4), 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0399-z

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Otoo, F. E., Kim, S. S., & King, B. (2021). African diaspora tourism-How motivations shape experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100565

- Reed, A. (2010). Gateway to Africa: The pilgrimage tourism of diaspora Africans to Ghana [Doctoral dissertation]. Department of Anthropology, Indiana University.

- Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications.

- Schramm, K. (2007). Slave route projects: Tracing the heritage of slavery in Ghana. In F. de Jong & M. Rowlands (Eds.), Reclaiming heritage: Alternative imaginaries of memory in West Africa (1st ed., pp. 71–98). Routledge.

- Shepherd, R. (2002). Commodification, culture and tourism. Tourist Studies, 2(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879702761936653

- Simons, B. (2019). Ghana’s Year of Return is on its way to success so the government should stop using bad data. https://qz.com/africa/1772851/ghanas-year-of-return-should-avoid-bad-govt-data

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage Tourism. Pearson Education.

- VisitGhana. (2019). About Year of Return, Ghana 2019. https://visitghana.com/events/year-of-return-ghana-2019/

- Yankholmes, A. (2023). The transatlantic slave trade. In D. Timothy (Ed.), Cultural heritage and tourism in Africa (pp.170-183). Routledge.

- Yankholmes, A. K., & Akyeampong, O. A. (2010). Tourists’ perceptions of heritage tourism development in Danish-Osu, Ghana. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.781

- Yankholmes, A., & McKercher, B. (2015). Understanding visitors to slavery heritage sites in Ghana. Tourism Management, 51, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.04.003

- Yankholmes, A., & Timothy, D. J. (2017). Social distance between local residents and African–American expatriates in the context of Ghana’s slavery-based heritage tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(5), 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2121

- Zeleza, P. T. (2005). Rewriting the African diaspora: Beyond the black Atlantic. African Affairs, 104(414), 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adi001