Abstract

Melting glaciers and snow fields have become one of the strongest symbols of global climate change, instigating last-chance tourism and rallying cries for climate action from activists. In this sense, retreating glaciers act as charismatic entities, appealing to the public’s feelings and imaginations. The melting cryosphere is also a subject for scientific enquiry, providing the knowledge needed to establish the rates at which glaciers are declining and how they interlink and interact with other natural and human systems. Here, by applying a relational ontology rooted in human geography and science and technology studies, we show how melting glaciers and snow fields serve as charismatic boundary objects that enable tourism actors to raise awareness about climate change and push for action. Specifically, we conducted interviews and surveys with mountain guides and other actors involved in glacier tourism in local communities surrounding two of the major ice caps in Norway, Jostedalsbreen and Folgefonna, and found that the melting glaciers serve to reconcile different knowledge systems, allowing for the coexistence of affect, imaginaries, and scientific rationality. Thus, with mountain guides as the catalysts, melting glaciers contribute to a shift from a discourse of fear to one of care.

1. Introduction

Glacial retreat is one of the most salient indicators of climate change, and glaciers and ice caps are losing mass in all global regions (IPCC, Citation2019). While there are well-known direct impacts of this development on sea level rise, freshwater supply, hydropower generation, and tourism, there are also less visible subjective and relational dimensions of glacier retreat (Allison, Citation2015; Sherry et al., Citation2018). The loss of ice and snow from culturally significant mountains can affect religious beliefs and place identities (Orlove et al., Citation2008). Glaciers and ice caps are also often important for place identity and symbolically and culturally significant for mountain communities (Allison, Citation2015; Gagné et al., Citation2014; Jurt et al., Citation2015; Orlove et al., Citation2008; Sherry et al., Citation2018).

Glaciers have become a powerful symbol of climate change precisely because they trigger our imagination and emotions (Allison, Citation2015; Carey, Citation2007), as well as offer ‘sublime’ qualities to tourists (Furunes & Mykletun, Citation2012). In contrast, climate change is a phenomenon that has been notoriously difficult for people to connect with emotionally because it is a fundamentally abstract concept rooted in mathematical models (Hulme, Citation2008, Citation2009; Jasanoff, Citation2010; Latour, Citation2014). This underscores the nature–human divide that underpins modernity, which is at the root of the climate and environmental crisis (Beck, Citation1992; West et al., Citation2020). Hence, there is a need for approaches to climate action that are rooted in relational, deliberative, and caring ontologies (Beck et al., Citation2021; Stirling, Citation2019; West et al., Citation2020).

Over the last decade, the ‘vanishing glacier’ narrative used in the media has triggered a new rise in glacier tourism and the ‘last-chance tourism’ (LCT) trend (Groulx et al., Citation2016; Lam & Tegelberg, Citation2019). In this context, LCT is occurring as a result of societal angst over climate change prompting tourists to visit and experience ‘endangered’ glaciers and associated natural environments before they ultimately vanish (Abrahams et al., Citation2022). Polar bears, snow, and sea ice are other typical LCT attractions (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2022), and the origin of the LCT concept is found in Arctic and Antarctic tourism studies (Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010; Lemelin et al., Citation2010).

Although LCT is being criticised for ignoring visitors’ greenhouse gas emissions, which further threaten vulnerable natural elements (Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010; Lemelin et al., Citation2010), the LCT tourists’ motivations to visit glaciers and other threatened natural elements are linked to their connections to nature and place attachment (Groulx et al., Citation2016). The place attachment experienced by LCT tourists is based on their emotional connections to nature and can provoke intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviour, which can be defined as ‘an action by an individual or group that promotes or results in the sustainable use of natural resources’ (Groulx et al., Citation2016; Lemieux et al., Citation2018; Salim et al., Citation2023; Salim & Ravanel, Citation2023).

The LCT phenomenon is also tied to the status of melting glaciers as a powerful symbol of climate change: ‘By the early twenty-first century, glaciers had reached celebrity status, with almost all popular writers who discussed global warming making glacier retreat a key component of their story’ (Carey, Citation2007, p. 498). In 2019, activists and scientists in Iceland held a funeral for the vanished Okjökull, the first Icelandic glacier lost to climate change (Árnason & Hafsteinsson, Citation2020; Magnason, Citation2020). For several years, the Presenna glacier in the Austrian Alps has been covered in UV blankets during summertime to prevent melting (Bruns, Citation2021). These activities point to an affective relationship between humans and glaciers that warrants greater study.

The meaning and cultural significance of glaciers also manifest as a salient component of place attachment (Allison, Citation2015; Sherry et al., Citation2018). Place attachment to a specific place encompasses both physical and social connections that individuals form with their surroundings and that are established through a multifaceted process of meaning-making (Halpenny, Citation2010; Sebastien, Citation2020). These connections develop into a sense of self and identity; in other words, an individual’s environmental surroundings shape their understanding of themselves. Consequently, environmental events that alter these surroundings or necessitate relocation can pose a threat to the individual’s personal and social identities (Amundsen, Citation2015; Heyd, Citation2014) and spur engagement of those affected (Groulx et al., Citation2016; Lewicka, Citation2005).

In our context, work in the human geography and sociology of knowledge fields on nonhuman agency and relational ontologies that seek to bridge the divide between society and nature is particularly relevant. This work points to the need for different ontologies that allow for experimental and embodied ways of knowing and recognising affective and emotional relations to more than the human world as an important precondition for climate action (Huijbens, Citation2021; Nightingale et al., Citation2022; O’Brien, Citation2016; Stirling, Citation2019; West et al., Citation2020). Such perspectives can also inform tourism geographic scholarship that focuses on sustainability and climate action. Recognising the relational nature of nonhuman agency in a web of humans and practices, this article show how nonhuman actants can catalyse pro-environmental behavior (e.g Contesse et al., Citation2021; Wadham, Citation2021).

Much of the public discourse on climate change feeds and reinforces a narrative of fear, sadness, and despair (Arora, Citation2019; O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Citation2009). The idea of arousing fear to promote precautionary motivation and self-protective action is strongly linked to individuals’ threat perceptions and thoughts of self-efficacy (Ruiter et al., Citation2001). However, this has been found to be an ineffective, even counterproductive, tool for motivating true personal engagement (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Citation2009). While these emotions are likely to pique an individual’s attention, they ultimately result in distancing and disengagement as individuals are left feeling helpless and overwhelmed with the issue at hand (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Citation2009). Recently, there has been a call for relational engagement with transformation that draws on care, hopefulness, and other positive affections (Arora, Citation2019; Head, Citation2016; Puig de La Bellacasa, Citation2017). For example, recognising a ‘climate icon’s’ intrinsic value and feeling connected to it through emotions, such as pride and identity can lead to the development of empathy for nature and a desire to protect the environment (Curnock et al., Citation2019). Positive feelings, such as hope and custodianship are more likely to encourage and motivate individual actions (Curnock et al., Citation2019). In this context, hope must be disentangled from optimism and instead associated with the imagining of alternative possibilities and futures (Head, Citation2016).

Undertaking outdoor recreational activities in challenging natural environments can lead to experiences of awe, which have the potential to be transformative personal experiences and result in attachment to nature (Løvoll & Sæther, Citation2022). This corroborates with studies on LCT in relation to glaciers that have found that place attachment influences pro-environmental behaviour (Groulx et al., Citation2016; Salim et al., Citation2023). There is, however, a lack of knowledge about how tourism actors can deliberately harness the power of affective relations and place attachment to reinforce behavioural change.

By drawing on two case studies conducted in mountainous regions in Norway, we demonstrate how melting snow and ice have become charismatic boundary objects, which enables mountain guides and other tourism actors to undertake caring practices towards climate action and thus instigate pro-environmental behaviour among glacier tourists.

2. Non-human charisma and boundary objects

For several decades, how the material world interacts with the social world has been of interest to geographers and science and technology scholars. Human geographers, such as Sarah Whatmore and Nigel Thrift, have deconstructed the subject–object dichotomy between humans and nature and have thereby decentred human agency and shown how notions of wilderness are constituted by hybrid and heterogenous social relationships (Thrift, Citation2004; Whatmore, Citation2002).

We drew on two theoretical concepts to conduct the analysis presented in this article: boundary objects and nonhuman charisma. We also rely on an understanding of wilderness that acknowledge the construction of the glacier as a hybrid entity, which again entails the redistribution of social agency to that of the agency of things (Whatmore, Citation2002). This form of nonhuman agency can also manifest through charisma (Lorimer, Citation2007). The charisma of nonhuman entities has primarily been studied in conservation biology as a property of ‘flagship’ species, which serve to aid environmental protection and thus display nonhuman agency. Nonhuman charisma can be defined ‘as the distinguishing properties of a nonhuman entity or process that determine its perception by humans and its subsequent evaluation’ (Lorimer, Citation2007, p. 915) and as ‘affective enchantment’ (Barua, Citation2020, p. 679). In particular, Lorimer’s ‘feral charisma’ is relevant to the study of glacier–human relationships. Feral charisma is grounded in ‘a sense of respect for the other and for its complexity, autonomy and wildness’ (Lorimer, Citation2007, p. 920). In contrast to the anthropomorphic ‘cuddly charisma’ that is associated with panda bears and other flagship species, feral charisma is expressed through wildness and chaotic characteristics. Thus, we argue that feral charisma can be a property of non-living entities that exhibit such characteristics.

Charisma can be seen as the relational qualities between the social and natural worlds that manifest through affect and an ethical relationship (Lorimer, Citation2007). Affect is understood as a collection of shared and interconnected forces that operate between bodies and, thus, it is not entirely the same as emotions, which, in a relational perspective, could be seen as the subjective encoding of the experience of these forces (Anderson, Citation2006). Affect is both being ‘attached’ and being ‘moved’ (Latimer & Miele, Citation2013), and Lorimer (Citation2007) argued that, in terms of conservation, affect is the force that drives people to get involved. In addition, Nightingale et al. showed that ‘It is precisely at this interface where the boundary is made between the ‘we’, the ‘I’, and the ‘more than human’, that affects flow, and where possibilities for transformation open up or close down’ (Nightingale et al., Citation2022, p. 7). Thus, affect that occurs as a response to the ‘agency’ of events and changes in the more-than-human world can inspire transformative changes in values and practices.

The affective dimension of charisma is strongly tied to care. Care is simultaneously a practice, an affection, and an ethic (Puig de La Bellacasa, Citation2017) and can be extended to nonhuman entities (Barua, Citation2020; Lorimer, Citation2007). Caring for nonhuman objects creates the opportunity for intersubjective, mutual relations that transcend the modernist duality between the social and natural worlds (Huijbens, Citation2021; Jackson & Palmer, Citation2015; Stirling, Citation2019; West et al., Citation2018). There is a growing call for caring practices that enable the transformation to sustainability, which can be understood as ‘affective, ethical dispositions in looking after damaged and neglected ecologies (of humans and nonhumans) (…)’ (Arora, Citation2019, p. 1575). However, the challenge is to identify the venues where such caring practices can have a tangible impact on broader sustainability transformations.

Charismatic entities can also serve as boundary objects that connect different realms or epistemic communities, such as science and the public (Lorimer, Citation2007; Star, Citation2010; Star & Griesemer, Citation1989). Boundary objects ‘have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognisable, a means of translation’ (Star & Griesemer, Citation1989, p. 393). Therefore, boundary objects enable translations of meaning and significance across boundaries between different social realms. Melting ice means different things to different epistemic communities. For the tourist community, glaciers are a material venue for bodily experiences and extraordinary sensory impressions, and awareness of melting ice may spur tourists to undertake LCT. For the public, melting ice has become a symbol and indicator of global climate change through the ‘endangered glacier narrative’ (Carey, Citation2007; Moulton et al., Citation2021). As Mahony (Citation2013) has shown, glaciers feature prominently in the scientific discourse of climate change. Quantitative records of glacial-front retreats and ice cores are used as proxies for the impact of climate change and for understanding the historic and current physical dynamics of climate change. The power and effectiveness of boundary objects also depend on the performances of boundary work—deliberate attempts to connect different epistemic communities through mediation and learning (Clark et al., Citation2016; Dannevig et al., Citation2020). Glacier tourism actors, science communicators, and others may perform such work, drawing on, funnelling, and enforcing glacial charisma. In glacier tourism and other types of nature-based tourism, the tourist’s experience—and thus the effectiveness of boundary work—is influenced by the social relationship between the guide and client (Løvoll & Sæther, Citation2022). This relationship is formed by the trust and care that are established when venturing into a challenging environment.

3. Methods

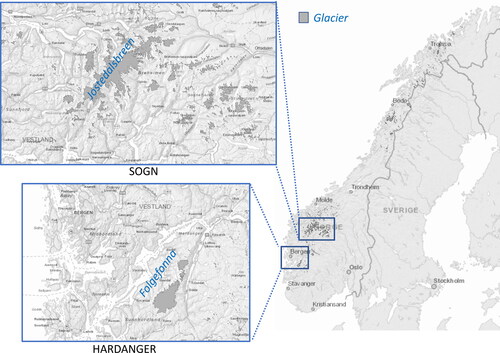

Two case studies were conducted in the regions of Sogn and Hardanger in Western Norway (see ). The study utilised a mix of qualitative methods, combining semi-structured interviews, group interviews, and an open-ended survey.

Guide companies and tourism operators were mapped via online searches and through cooperation with regional and local destination marketing companies, such as FjordNorway (https://www.fjordnorway.com/), the Visitor Centre for the Breheimen National Park (https://www.jostedal.com/) and the Norwegian Glacier Museum & Ulltveit-Moe Climate Centre (https://www.bre.museum.no/).

One of the authors, Dannevig, is a certified mountain guide and has been guiding in the Sogn area for 15 years. Thus, he has an extensive network in the industry, which we utilised for the informant selection. We interviewed guides who worked for different companies and who had worked for a minimum of 10 years in the area.

A meeting was held with the selected guides and guide company managers to present the study and refine the research question. Next, to obtain a general overview of the guides’ use of mountains and glaciers and their perceptions of climate change, the mountain and glacier guides completed an open-ended questionnaire (n = 40). Finally, to understand the guides’ personal experiences in nature, emotional connections to the glacier, perceptions of change, and motivations to convey messages of sustainability and pro-environmental behaviour, 13 semi-structured interviews were conducted with guides (n = 8), guide company managers (n = 2) and accommodation managers (n = 3). The semi-structured interviews were conducted using a loosely formatted interview guide, which allowed for the addition of new questions and elaboration on specific topics; thus, each interview had the potential to resemble a conversation (Bryman, Citation2016). Due to Dannevig’s intimate knowledge of the guiding profession, he shared many of the informants’ experiences of engaging in dialogues with clients about climate change when encountering shrinking glaciers or the loss of snow.

The interview transcripts and survey statements were coded using the analytical programme NVivo, and codes were used for the following categories: observed changes in both climate and industry, attempts to influence tourists towards pro-environmental behaviour, charisma of the glacier (characteristics of aesthetics, attraction), emotional connection, awareness creation and knowledge dissemination about glacier retreat and climate change, and reactions to glacier retreat.

3.1. Glacier retreat and glacier tourism in Norway

With 1282 glaciers spanning 2692 km2, Norway has the largest area of glaciers in mainland Europe (Andreassen et al., Citation2012). Throughout the centuries, glaciers have been an integral part of the identity of Norwegian communities because they provide water for agriculture and communities and, more recently, hydropower. They are also an important resource for tourism in many rural areas. Glacier tourism is a major tourism category in Norway and, along with the Norwegian fjords, is one of the key pulling factors for tourists to visit Norway (Innovation Norway, Citation2018). A large number of tourists travel to glacier areas to view glaciers and take part in glacier adventure activities, such as glacier hiking and ice climbing, snowshoeing, glacier lake kayaking, skiing, and mountaineering. Most tour operators are small, locally owned businesses located in rural areas with seasonal operations.

Since the mid-1990s, the Norwegian glaciers have been steadily receding (NVE, Citation2022). Some of the glacier arms vital to tourism have receded by as much as 275 m in a single year, such as Briksdalsbreen in Olden (NVE, Citation2022). In terms of the development of perennial snow fields, there is a lack of systematic mapping. As the glaciers recede, they are increasingly covered with debris and become less accessible and more hazardous, with longer approaches and a higher risk of rockfall, flash floods, and ice avalanches. This makes glacier tourism more challenging, and one of the few studies on Norwegian glacier tourism (Furunes & Mykletun, Citation2012) found that the glacier tourism market declined from 2003 to 2009. However, this decline might not have been directly due to glacier retreat; Welling et al. (Citation2020) argued that, although glaciers are retreating, visitors are still willing to visit glacier areas.

4. The agency of melting snow and ice

4.1. Caring for melting snow and ice

Glaciers are alien, beautiful, dangerous, and intriguing. Viewed from a distance, they create a striking white-blue contrast to the brown-grey barren rocks and boulders of the surrounding mountain (see ). When up close, visitors can gaze at the mesmerising turquoise blue glacier ice, the abyss-like crevasses hidden under treacherous bridges of snow, and the bizarre towers, mazes, and meandering gullies carved out by surface streams. The sound of running water is accompanied by occasional creaks caused by minor movements in the ice and, more rarely, by thunder resulting from collapsing towers of ice. For adventurous tourists, glaciers offer the challenges of traversing slippery ice using crampons and ice axes slippery ice and climbing and scrambling over ridges and crevasses. Glacier hiking offers a unique combination of bodily and sensory experiences.

Mountain guides and other tourism actors (notably accommodation managers) with a decade or more of experience have witnessed the mountain landscape change during their careers as glaciers and snow fields recede. In our interviews, the guides expressed strong emotional connections to the mountain areas, which they regarded as their ‘home mountains’. These emotions were tied to having had powerful experiences and mastering risks and difficulties, as shown by the following quote: ‘It’s a personal connection from when I was younger. I have had a lot of really powerful experiences, of mastery, and also experiences from trips where we failed but still learned a lot’ (Guide #5). This statement alludes to nostalgic and intimate relations with the mountain landscape and also signifies the temporal dimension of landscapes and place attachment, where landscapes are a product of affect, imaginations, and memories (Brace & Geoghegan, Citation2011). Another informant also connected the sense of belonging and connection with the place, stating: ‘I know the area really, really, well—I feel that I master this terrain’ (Guide #4). Some also articulated affections tied to their memories of mountain landscapes, with statements, such as ‘I realise that I have become really fond of, what they [the mountains] have been, and my memory of them’ (Guide #1). Here, the guide recalled memories of specific mountains that bear meaning to him—signalling a lived experience, kinship, and an affective relation (Brace & Geoghegan, Citation2011). The feelings, perceptions and sensory input created by powerful experiences in the mountain landscapes construct an imagined landscape from a particular point in time, which then becomes the reference point for perceiving climate change-induced change in mountains and glaciers, as observed by Brace and Geoghegan: ‘(.)landscape becomes a possible means with which to organize the immediate and future, spatially and temporally intimate relations between people, flora, fauna, topography, environment and, crucially, weather.’ (Brace & Geoghegan, Citation2011, p. 289).

Other informants shared that they live in the community near the glacier in Sogn because of the surrounding nature, with one stating: ‘I feel a certain calmness and connectedness when in nature here. I could have lived anywhere in the world but I chose to live here [community near the glacier]’ (Accommodation manager #1); and another: ‘a landscape with green forests and white mountaintops is very beautiful. It is an important element of the area to make people thrive. It creates a willingness to live here’ (Guide #7).

Here, the aesthetic dimensions of place attachment appear to be salient and contribute to well-being and a sense of belonging. The emotional and affective relations between the informants and the glaciated landscapes signified in these quotes were also identified by Salim et al. (Citation2021) in their study conducted in the Alps. The statements further illustrate the embodied human–non-human engagement that co-produces place attachment and care (Barua, Citation2020; Huijbens, Citation2021).

Although they recognised that the loss of snow and ice may not affect the demand for guided mountain tours, the guides expressed agitation and sadness when discussing the disappearance of perennial snow and ice. Expressions, such as ‘scary’ mountains becoming ‘uglier’, ‘terrible to look at’ and ‘it is making me sad’ were recurring among all the informants:

I can clearly see that the glacier is changing (…). I can see it with my own eyes, and when I compare it to older pictures, it affects me. I’m saddened. I’m not personally scared of climate change, I don’t feel fear, but as a professional I know that climate change is happening. (Guide #6)

In addition to the visual appeal of snow-covered peaks, Guide #4 also noted the attractive feeling of walking on snow: ‘I really enjoy hiking on snow, it makes it easier on the way down (…). And I think it is great to look at peaks with perennial snow’ (Guide #4). Guide #4 went on to point out that the sensory experience and satisfaction gained from being in and on the mountains is being affected by the loss of the glaciers and perennial snow and ice, as it makes mountain climbs harder, less attractive, and more hazardous: ‘Where there used to be a glacier, is now just a hill of gravel, it’s not nice to walk there, it’s riskier, these steep slopes of gravel’ (Guide #3).

Thus, the loss of snow and ice affects more than just the gaze (i.e. the visual dimension of the mountain–guide relation), it impacts all the senses involved in climbing and hiking. Freshly exposed ground where ice has melted tends to be covered with gravel and loose rock, making it challenging and dangerous for mountaineers to cross. It is a qualitatively different experience to hike and climb on rocks and gravel than on snow and ice. The statements above thus highlight the embodied, sensory engagement that lies at the heart of the guides’ affective relations and care for the mountains’ snow and ice.

In the open-ended questionnaire, emotional reactions to the disappearance of the snow and ice were also expressed, and the following are some examples of such reactions: ‘It’s not nice. It’s becoming ugly’, ‘It worries me that the glaciers are disappearing’, and ‘I want the mountains that I love, particularly the glaciers, to remain as little affected as possible. You want to keep what you hold dear’.

The abovementioned statements that were provided in the interviews and questionnaires show the emotional and affective relationships between the guides and the mountains, which in turn shape how they react to cryosphere change. There are expressions of sadness and grief, but also of care, signifying the value and meaning attributed to the glaciated mountains. In particular, the last quote implies a caring affection (e.g. Curnock et al., Citation2019). The charisma of glaciers and snow-clad mountains seems particularly tied to their aesthetic appeal and the lived and embodied experiences that people have had when venturing on and among them. The attributes of feral charisma, wildness, and chaos (Lorimer, Citation2007) can also explain the attraction of wilderness in general. However, these properties are vested in glaciers and mountain landscapes through their affective relationship with humans, constituting ‘heterogenous social networks which are performed in and through multiple places and fluid ecologies’ (Whatmore, Citation2002, p. 14).

In the following section, we present how affective relations contribute to different degrees of activism among guides and tourism actors.

4.2. Melting snow and ice as boundary objects: awareness creation and instigation of pro-environmental behaviour

A caring relationship compels an individual to act to preserve what they hold dear, and in this way, melting glaciers exercise agency (Whatmore, Citation2002). The guides and other tourism actors who participated in this study were found to display care by conveying information about melting glaciers and disappearing snow fields to create awareness among tourist groups. All the interviewed guides stated that when they encountered retreating glaciers or part of a mountain where a snow field had disappeared, they used the opportunity to talk about climate change and its impact on glaciers and perennial snow. Through these actions, the tourists’ gaze and relations with glaciers and perennial snow and ice are reconfigured from an aesthetic appraisal to climate change awareness, as alluded to in the following quote:

It feels natural to bring it up when we are walking in the glacial landscape, when we can see the moraines, how the glacier has changed. I do that on almost every trip.

(…) I do think it varies a lot, the extent to which clients are able to absorb this. But I think it gradually sinks in. (…) I think it’s those who usually care, who also care about this. (…) But to discuss this and to highlight it, I have a duty and a right to do so. (Guide #2).

We discuss internally what we want to convey to the clients and a minimum level of what to bring up during our trips. Often, we are met with the topic of nature and change when we are out, for example, seeing a hydropower station and a calving glacier, a perfect example of man vs. nature. (…) We talk of how this impacts nature in the area. Then, we talk about our operations in terms of sustainability (…), of how we repair and buy used equipment, to stay as low-impact as possible. Guests are very aware of this when they consider tour operators, to compensate for a potentially long journey with high emissions. (Guide company manager #1)

The hybrid nature of the glaciers and melting snow was also revealed by how some of the guides felt compelled to raise with their clients the need to combat climate change and reduce consumption, for example:

I think there is a need for a joint front. What I want is a kind of revolution. Someone should say, ‘We have been talking for years. Now it’s time for drastic action. We will put demands on ourselves, and we will place demand on our clients and our partners to the authorities’. We should announce our demands as a king’s herald in the old times. It is extremely important that such an initiative does not end up as just another example of greenwashing. (Guide #1)

I try to increase my knowledge of sustainability to do things better. To analyse actual climate measures and which ones really make a difference. We use electric cars, buy used equipment (kayaks, rafts, video-equipment, paddles, etc.), and I spend time teaching my staff how to fix our equipment instead of buying something new. We try to fix all that is reparable. It doesn’t necessarily save us a lot of money, but it saves the environment, and we are able to set an example of how it can be done for our guests as well. (Guide company manager #1)

Nevertheless, there is an inherent tension between the commodification of nature that is implicit in tourism and the relational values expressed in most of the statements above. The charisma of glaciers is obviously in a symbiotic relationship with their value as a commodity, as tourists are willing to pay to access them (Young & Markham, Citation2020). Tourism inevitably leads to commodification of nature, which is a necessary consequence of capitalism according to Lefebvre (Citation1976) and other geographers drawing on Marxian value theory (Castree, Citation2008; Young & Markham, Citation2020). However, this understanding of the relationship between tourism and nature misses the immaterial and relational values exchanged in tourism and mountain guiding, as indicated in the interview statements above. Despite the inherent commodification associated with mountain and glacier guiding, our interviews with guides and other tourism actors indicate that they are motivated by more than purely economic factors, namely affective relations with the places in which they live and work. These caring relations with the mountains have inspired the adoption of sustainable practices, and this finding aligns with the insights revealed by Contesse et al. (Citation2021), Lorimer (Citation2007), Walker and Moscardo (Citation2016), and others into how nonhuman agency can inspire changes towards sustainability.

5. Conclusion

Until the recent climate change-related heat waves and disasters, most people perceived climate change as an abstract phenomenon, one defined by science and complex mathematical models (Hulme, Citation2009; Jasanoff, Citation2010). Melting glaciers are one of the most visual impacts of climate change. This enables them to serve as boundary objects, connecting the social worlds, or epistemic communities, of tourism and climate change science. This property can be regarded as a form of nonhuman agency that is vested in glaciers and perennial snow due to their feral charisma tied to their wildness, aesthetic appearance (Lorimer, Citation2007), fame, and iconic status in art and tourist marketing materials. The occurrence of funerals for glaciers and the motives that drive LCT are also indicative of this affective relationship and agency. We thus argue that applying the quality of charisma, although it is an anthropocentric property, to inanimate objects elicits awareness of the potential for agency to be exercised by nonhuman entities—which we have shown here can be mobilised for sustainability transformation.

In this study, the guides’ affective relations to the glaciers were found to compel them to raise awareness about climate and environmental change, and thereby they bridge the boundary between science and tourism as boundary workers (Dannevig et al., Citation2020). Through this action, the guides and other tourism professionals bring up their concerns about climate change and sustainability and evoke affect and emotions, such as care and concern. Although the increasing volume of literature on LCT is an indicator of the affective power of vanishing glaciers on tourists (Dawson et al., Citation2011; Lemelin et al., Citation2013; Salim et al., Citation2023), there is still limited knowledge on how tourism actors and others can consciously employ it to instigate pro-environmental behaviour. The notion that spending time in nature will make you care for it is a core persuasion from deep ecology (Faarlund, Citation1993; Naess, Citation1973), which, more recently, has been supported by environmental psychology and outdoor recreation sociologists (Gifford, Citation2014; Løvoll & Sæther, Citation2022; Varley & Semple, Citation2015). In addition, we have no knowledge about whether the clients’ post-trip impressions and convictions mentioned by the participants were translated into lasting pro-environmental behaviour. Furthermore, it is unclear how and to what extent a client’s behaviour must change to outweigh the carbon footprint associated with their guided travel, an issue also discussed in the LCT literature (e.g. Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010) and ecotourism literature (Das & Chatterjee, Citation2015).

Nevertheless, our results show that relational ontologies and caring approaches can offer new insights for tourism geography into how deliberate attempts to harness the charisma and affective power of a changing natural environment can contribute to the instigation of pro-environmental sentiments and, ultimately, a transformation towards sustainability.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the valuable discussions that we had on this topic and the input we received into an earlier version of this paper at the Ice in a Sustainable Society Conference in Bilbao June 5–10 2022. We also want to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly helped to improve the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Halvor Dannevig

Halvor Dannevig is research director and research professor at Western Norway Research Institute in Sogndal, Norway. He is a human geographer focusing on environmental governance, nature based tourism and climate change, and other issues tied to sustainability and human-nature interactions.

Tone Rusdal

Tone Rusdal held a position as a researcher at Western Norway Research Institute, but has currently taken on a position as climate advisor in Sandnes municipality, Norway.

References

- Abrahams, Z., Hoogendoorn, G., & Fitchett, J. M. (2022). Glacier tourism and tourist reviews: An experiential engagement with the concept of “last chance tourism”. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1974545

- Allison, E. A. (2015). The spiritual significance of glaciers in an age of climate change. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(5), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.354

- Amundsen, H. (2015). Place attachment as a driver of adaptation in coastal communities in Northern Norway. Local Environment, 20(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.838751

- Anderson, B. (2006). Becoming and being hopeful: Towards a theory of affect. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 24(5), 733–752. https://doi.org/10.1068/d393t

- Andreassen, L. M., Winsvold, S. H., Paul, F., & Hausberg, J. E. (2012). Inventory of Norwegian glaciers. In NVE Rapport (Vol. 38). Norges Vassdrags-og energidirektorat.

- Árnason, A., & Hafsteinsson, S. B. (2020). A funeral for a glacier: Mourning the more-than-human on the edges of modernity. Thanatos, 9(2), 46–71.

- Arora, S. (2019). Admitting uncertainty, transforming engagement: Towards caring practices for sustainability beyond climate change. Regional Environmental Change, 19(6), 1571–1584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01528-1

- Barua, M. (2020). Affective economies, pandas, and the atmospheric politics of lively capital. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(3), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12361

- Beck, S., Jasanoff, S., Stirling, A., & Polzin, C. (2021). The governance of sociotechnical transformations to sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 49, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.04.010

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage publications.

- Brace, C., & Geoghegan, H. (2011). Human geographies of climate change: Landscape, temporality, and lay knowledges. Progress in Human Geography, 35(3), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510376259

- Bruns, C. J. (2021). 8 Grieving Okjökull. In H. Bødker & H. E. Morris (Eds.), Climate change and journalism: Negotiating rifts of time (pp. 121–135). Routhledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books/about/Climate_Change_and_Journalism.html?hl=no&id=IFYzEAAAQBAJ

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Carey, M. (2007). The history of ice: How glaciers became an endangered species. Environmental History, 12(3), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/12.3.497

- Castree, N. (2008). Neoliberalising nature: Processes, effects, and evaluations. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 40(1), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39100

- Clark, W. C., Tomich, T. P., van Noordwijk, M., Guston, D., Catacutan, D., Dickson, N. M., & McNie, E. (2016). Boundary work for sustainable development: Natural resource management at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(17), 4615–4622. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900231108

- Contesse, M., Duncan, J., Legun, K., & Klerkx, L. (2021). Unravelling non-human agency in sustainability transitions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120634

- Curnock, M. I., Marshall, N. A., Thiault, L., Heron, S. F., Hoey, J., Williams, G., Taylor, B., Pert, P. L., & Goldberg, J. (2019). Shifts in tourists’ sentiments and climate risk perceptions following mass coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. Nature Climate Change, 9(7), 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0504-y

- Dannevig, H., Hovelsrud, G. K., Hermansen, E. A. T., & Karlsson, M. (2020). Culturally sensitive boundary work: A framework for linking knowledge to climate action. Environmental Science & Policy, 112, 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.07.002

- Das, M., & Chatterjee, B. (2015). Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tourism Management Perspectives, 14, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.01.002

- Dawson, J., Johnston, M. J., Stewart, E. J., Lemieux, C. J., Lemelin, R. H., Maher, P. T., & Grimwood, B. S. R. (2011). Ethical considerations of last chance tourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 10(3), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2011.617449

- Eijgelaar, E., Thaper, C., & Peeters, P. (2010). Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship, “last chance tourism” and greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653534

- Furunes, T., & Mykletun, R. J. (2012). Frozen adventure at risk? A 7-year follow-up study of Norwegian glacier tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(4), 324–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.748507

- Faarlund, N. (1993). Friluftsliv – A way home. In P. Reed & D. Rothenberg (Eds.), Wisdom in the open air (pp. 155–175). University of Minnesota Press.

- Gagné, K., Rasmussen, M. B., & Orlove, B. (2014). Glaciers and society: Attributions, perceptions, and valuations. WIREs Climate Change, 5(6), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.315

- Gifford, R. (2014). Environmental psychology matters. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 541–579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115048

- Groulx, M., Lemieux, C., Dawson, J., Stewart, E., & Yudina, O. (2016). Motivations to engage in last chance tourism in the Churchill Wildlife Management Area and Wapusk National Park: The role of place identity and nature relatedness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(11), 1523–1540. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1134556

- Halpenny, E. A. (2010). Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

- Head, L. (2016). Hope and grief in the anthropocene re-conceptualising human–nature relations. Routhledge.

- Heyd, T. (2014). Symbolically laden sites in the landscape and climate change. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 17(3), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2014.955313

- Huijbens, E. H. (2021). Developing earthly attachments in the anthropocene. In Developing earthly attachments in the anthropocene (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003098782

- Hulme, M. (2008). The conquering of climate: Discourses of fear and their dissolution. The Geographical Journal, 174(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2008.00266.x

- Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change. Understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge University Press.

- Innovation Norway (2018). Key figures for Norwegian travel and tourism 2018. In Innovation Norway report. Author.

- IPCC (2019). Special report: The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate (H. O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, & N. W. J. Petzold, B. Rama, Eds.; Issue September). Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/srocc/

- Jackson, S., & Palmer, L. R. (2015). Reconceptualizing ecosystem services. Progress in Human Geography, 39(2), 122–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514540016

- Jasanoff, S. (2010). A new climate for society. Theory, Culture & Society, 27(2–3), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409361497

- Jurt, C., Brugger, J., Dunbar, K. W., Milch, K., & Orlove, B. (2015). Cultural values of glaciers. In The high-mountain cryosphere: Environmental changes and human risks (pp. 90–106). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107588653.006

- Lam, A., & Tegelberg, M. (2019). Witnessing glaciers melt: Climate change and transmedia storytelling. Journal of Science Communication, 18(2), A05. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.18020205

- Latimer, J., & Miele, M. (2013). Naturecultures? Science, affect and the non-human. Theory, Culture & Society, 30(7–8), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413502088

- Latour, B. (2014). Agency at the time of the anthropocene. New Literary History, 45(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2014.0003

- Lefebvre, H. (1976). The survival of capitalism. Allison and Busby.

- Lemelin, H., Dawson, J., Stewart, E. J., Maher, P., & Lueck, M. (2010). Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 477–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903406367

- Lemelin, R. H., Stewart, E., & Dawson, J. (2013). An introduction to last chance tourism. In R. H. Lemelin, E. Stewart, & J. Dawson (Eds.), Last chance tourism adapting tourism opportunities in a changing world (pp. 21–27). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203828939-8

- Lemieux, C. J., Groulx, M., Halpenny, E., Stager, H., Dawson, J., Stewart, E. J., & Hvenegaard, G. T. (2018). “The end of the ice age?”: Disappearing world heritage and the climate change communication imperative. Environmental Communication, 12(5), 653–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2017.1400454

- Lewicka, M. (2005). Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.10.004

- Lorimer, J. (2007). Nonhuman Charisma. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 25(5), 911–932. https://doi.org/10.1068/d71j

- Løvoll, H. S., & Sæther, K. W. (2022). Awe experiences, the sublime, and spiritual well-being in Arctic wilderness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(August), 973922. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.973922

- Magnason, A. S. (2020). On time and water. Serpent’s Tail.

- Mahony, M. (2013). Boundary spaces: Science, politics and the epistemic geographies of climate change in Copenhagen, 2009. Geoforum, 49, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.05.005

- Moulton, H., Carey, M., Huggel, C., & Motschmann, A. (2021). Narratives of ice loss: New approaches to shrinking glaciers and climate change adaptation. Geoforum, 125, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.06.011

- Naess, A. (1973). The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: a summary. Inquiry, 16(1–4), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747308601682

- Nightingale, A. J., Gonda, N., & Eriksen, S. H. (2022). Affective adaptation = Effective transformation? Shifting the politics of climate change adaptation and transformation from the status quo. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 13(1), e740. https://doi.org/10.1002/WCC.740

- NVE (2022). Klimaprodukter bre. NVE. Retrieved from http://glacier.nve.no/glacier/viewer/ci/no/

- O’Brien, K. L. (2016). Climate change and social transformations: Is it time for a quantum leap? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.413

- O’Neill, S., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear won’t do it” promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

- Orlove, B., Wiegandt, E., & Luckman, B. (2008). The place of glaciers in natural and cultural landscapes. In B. Orlove, E. Wiegandt, & B. H. Luckman (Eds.), Darkening peaks: Glacier retreat, science, and society (pp. 3–22). University of California Press.

- Puig de La Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds (Vol. 41). University of Minnesota Press.

- Ruiter, R. A. C., Abraham, C., & Kok, G. (2001). Scary warnings and rational precautions: A review of the psychology of fear appeals. Psychology & Health, 16(6), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440108405863

- Salim, E., & Ravanel, L. (2023). Last chance to see the ice: Visitor motivation at Montenvers-Mer-de-Glace, French Alps. Tourism Geographies, 25(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1833971

- Salim, E., Ravanel, L., & Deline, P. (2023). Does witnessing the effects of climate change on glacial landscapes increase pro-environmental behaviour intentions? An empirical study of a last-chance destination. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(6), 922–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2044291

- Salim, E., Ravanel, L., & Gauchon, C. (2021). Aesthetic perceptions of the landscape of a shrinking glacier: Evidence from the Mont Blanc massif. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 35, 100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100411

- Sebastien, L. (2020). The power of place in understanding place attachments and meanings. Geoforum, 108, 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.001

- Sherry, J., Curtis, A., Mendham, E., & Toman, E. (2018). Cultural landscapes at risk: Exploring the meaning of place in a sacred valley of Nepal. Global Environmental Change, 52, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.07.007

- Star, S. L. (2010). This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origin of a concept. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(5), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Stirling, A. (2019). Sustainability and the politics of transformations: From control to care in moving beyond modernity. In J. Meadcroft, D. Banister, E. Holden, O. Langhelle, K. Linnerud, & G. Gilpin (Eds.), What next for sustainable development? (pp. 218–238). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Thrift, N. (2004). Intensities of feeling: Towards a spatial politics of affect. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x

- van Zyl, A., & van Etteger, R. (2021). Aesthetic creation theory applied: A tribute to a glacier. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 16(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2021.1948193

- Varley, P., & Semple, T. (2015). Nordic slow adventure: Explorations in time and nature. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 15(1–2), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1028142

- Varnajot, A., & Saarinen, J. (2022). Emerging post-Arctic tourism in the age of Anthropocene: Case Finnish Lapland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 22(4–5), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2022.2134204

- Wadham, H. (2021). Relations of power and nonhuman agency: Critical theory, clever hans, and other stories of horses and humans. Sociological Perspectives, 64(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121420921897

- Walker, K., & Moscardo, G. (2016). Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: The role of Indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists’ place images and personal values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8–9), 1243–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1177064

- Welling, J., Árnason, Þ., & Ólafsdóttir, R. (2020). Implications of climate change on nature-based tourism demand: A segmentation analysis of glacier site visitors in southeast Iceland. Sustainability, 12(13), 5338. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135338

- West, S., Haider, L. J., Masterson, V., Enqvist, J. P., Svedin, U., & Tengö, M. (2018). Stewardship, care and relational values. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.008

- West, S., Haider, L. J., Stålhammar, S., & Woroniecki, S. (2020). A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosystems and People, 16(1), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417

- Whatmore, S. (2002). Hybrid geographies: Natures cultures spaces bewildering spaces. SAGE Publications Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/Hybrid-Geographies-Natures-Cultures-Spaces/dp/076196567X

- Young, M., & Markham, F. (2020). Tourism, capital, and the commodification of place. Progress in Human Geography, 44(2), 276–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519826679