Abstract

Policy interventions for tourism sustainability transitions are carried out in destinations worldwide. Yet, how decision-making processes and strategies could adversely affect communities and regions is an increasingly raised question, particularly following the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism destinations. Drawing on the transitions and justice literature, this paper explores what sustainability policies and rapid government interventions signify for impacted tourism communities. This paper uses Boracay island in the Philippines as a case study, a destination which has been subject to an extensive policy intervention ordered by the national government from 2018 onwards. The Boracay case indicates that a short and radical policy intervention did benefit the island, but that it could have been more societally beneficial if principles and policies of just transitions were more explicitly addressed. Key findings of this paper, based on an analysis of stakeholder views collected through interviews, questionnaires, and policy documents, reveal that the structural absence of dialogue and limited socio-economic support measures resulted in an island community that felt substantially ignored, unfairly treated, and sceptical about future actions. With the just transition lens, this paper offers practical and methodological guidance in reconciling tourism sustainability transitions with justice challenges. We conclude that the just transition lens provides important insights and lessons for transitioning tourism destinations towards environmentally sustainable futures in a socio-economically responsible way.

Introduction

The sustainability challenges of tourism have been discussed for decades, including the meaning of the term sustainability in the context of tourism (Sharpley, Citation2020), as well as specific environmental, social and economic impacts that tourism development brings at various spatial scales, from local to global (e.g. Gössling, Citation2000; Peeters & Landré, Citation2011). For many of these challenges, tourism cannot be considered sustainable if it is not making a positive net contribution towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including in the context of biodiversity and nature conservation, pollution prevention, greenhouse gas mitigation, and poverty alleviation (e.g. Buckley, Citation2012; Saarinen, Citation2020).

While there is increasing academic consensus on the need for sustainable transitions in the tourism system, how and with what instruments such transitions can be achieved is less clear. Since the early 2000s, new perspectives on sustainability transitions have been developed in the transition management literature (Berkhout Citation2002; Rotmans et al., Citation2001). However, systematic analysis of sustainable tourism transformations has been limited so far. While the link between the sustainable tourism and the transition management literatures was made about a decade ago (Gössling et al., Citation2012), applications of approaches on how tourism can de-lock itself from an unsustainable path of development and how contested transitions can be managed have been limited. More recently, Niewiadomski and Brouder (Citation2022) emphasised the need to address sustainability transitions in tourism more comprehensively, including the voices of local communities and the power dynamics at play.

Transitions can be defined as longer term processes in which society changes fundamentally (Rotmans et al., Citation2001), and refer to the change in dynamic equilibrium of a system, from one state of equilibrium to another, also referred to as regime change (Smith et al., Citation2005). In more recent years it has become clear that executing sustainability transitions comes with a range of challenges and trade-offs. Geels et al. (Citation2017) highlight major transition challenges, such as the multiplicity of actors and their complex social relations, the complex negotiations between various objectives and constraints, as well as the threats to existing economic business models and powerful industries. Transition challenges are often connected to socio-economic development needs, whereby transitions do not always produce desired socially just conditions. Healy and Barry (Citation2017) call for greater recognition of the politics, power dynamics and political economy of transitions, as perceived socio-economic costs can hinder support for transition policies. As scientists, policymakers and practitioners mainstream sustainable development agendas, ambiguities in the framing, justification and practice of transformative change may create tensions and implementation challenges (Blythe et al., Citation2018).

Ciplet and Harrison (Citation2019) argue that scholarship is needed on how jurisdictions are navigating equity and justice issues in sustainability transitions, including allocation and access (e.g. equity, fairness, justice) and accountability (Patterson et al., Citation2017). Studies on distinct regions and communities affected by sustainability transitions remain an underdeveloped research area (Heffron & McCauley, Citation2018; Wibeck et al., Citation2019), particularly in the Global South where additional complexities arise, such as alleviating poverty and prioritising economic development (Swilling et al., Citation2016; Wieczorek, Citation2018). Many rapidly industrialising economies (e.g South Africa, Vietnam, Philippines) want to follow earlier Asian industrialisers (e.g. South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan), but are facing a more climate and resource constrained world (Swilling & Annecke, Citation2012). Tourism is typically a significant economic sector in these rapidly industrialising countries, but there has been little attention given to the social implications of sustainability transitions in the context of tourism-dependent destinations.

Responding to the need to understand the social implications of sustainable tourism transitions, this article focuses on Boracay, an island located in the Philippines. The island is a flagship Philippine destination, generating about USD 1 billion in tourism revenues and attracting over two million tourists annually (Ordinario, Citation2019). The local community is highly dependent on tourism revenues. About 36,000 people work in the regional tourism economy, which includes direct employment on Boracay island, as well as in the wider region in food supply and services to the island. Over the last decades, Boracay has been confronted with unsustainable tourism development, including major environmental (Burgos, Citation2017; Ranada, Citation2018) and socio-economic impacts (Carter, Citation2004; Ong et al., Citation2011; Trousdale, Citation1999).

In 2018, the Philippine government intervened with drastic sustainability actions, including a six-month closure to rehabilitate the island. To mitigate the socio-economic impacts of the sustainability intervention, the Philippine government implemented several measures, including financial support programs to assist people and train workers during sustainability projects (Philippine News Agency [PNA], Citation2018).

The objective of this paper is to analyse socio-economic impacts associated with sustainability transitions in a tourism dependent island context, by conducting a comprehensive case study analysis of the impacts of the sustainability transition on Boracay. We aim to identify the socio-economic policies implemented by authorities to support local communities, workers, and businesses, and to analyse their socio-economic impacts on the communities of Boracay, through a justice and transitions lens. In the next section we explore justice theory and the just transitions literature to support our analysis, followed by the methodology and the findings. The paper closes with a discussion of results and the conclusion.

Just transitions

It has been argued that within conceptualizations of sustainability transitions, social dimensions and normative questions related to equity and justice remain largely unexplored (Blythe et al., Citation2018; Leach et al., Citation2012; Patterson et al., Citation2017; Wibeck et al., Citation2019). The term ‘just transition’ originates from the 1980s when labour unions tried to reconcile environmental imperatives with justice for workers in North American industries that were strongly affected by environmental laws (Goddard & Farrelly, Citation2018; Stevis & Felli, Citation2015). Over time, the term just transition has been applied more broadly to refer to the socio-economic implications of environmental and climate policies, implemented by national governments and international organisations that highlighted ‘just transition’ measures (e.g. Hägele et al., Citation2022; Jenkins et al., Citation2020; Morena et al., Citation2020).

There is an explicit need to study local action and consider social justice and equity in the process of shifting towards sustainability. Agyeman et al. (Citation2003) introduced the term ‘just sustainability’ to bring together the key dimensions of both environmental justice and sustainable development. They focus on distributional inequalities underpinned by good governance and emphasise purposeful involvement of citizens and stakeholders. Along similar lines Dobson (Citation1999) claimed that despite the benefits, social justice and environmental sustainability are not always compatible objectives.

Scholarly attention to just transitions has recently been increasing. Newell and Mulvaney (Citation2013) argue that a demand for just transitions ensures that the move towards a low carbon society is equitable, sustainable, and legitimate in the eyes of citizens and local communities. This includes key questions of who wins and who loses in a transition, how and why. Healy and Barry (Citation2017) call for more systematically addressing just transition by analysing the distributional impacts and the role of labour in low-carbon transitions.

In several sectors, just transition debates have spurred mass demonstrations in recent years. Francés carbon taxes caused social justice anger because of the disproportionately high burden on poorer households leading to the ‘yellow vests’ protests, while the Netherlands have seen a series of farmers’ protests against environmental policies (e.g. Morena et al., Citation2020; van der Ploeg, Citation2020).

Sustainability transitions are increasingly translated from an academic concept into a set of concrete actions. For instance, Harrahill and Douglas (Citation2019) identified a range of measures to enable policy to achieve just transition outcomes, including social dialogue, re-employment, and welfare schemes.

Conceptual framework

Just transition scholarship has been connected to justice theory, including its widely applied three-part conception of procedural justice, justice as recognition and distributive justice (e.g. Healy & Barry, Citation2017; Newell & Mulvaney, Citation2013; Schlosberg, Citation2007; Young, Citation1990). This three-part conception of social justice has been applied in the fields of energy and climate, as well as in relation to indigenous people (Agyeman et al., Citation2016; Jenkins et al., Citation2016). This paper operationalises just transition in the context of the sustainable tourism transition of Boracay island in terms of the three-part justice conception.

Issues of procedural justice cover the rules and procedures through which decisions are made and focus on participation in deliberation and decision-making (Young, Citation1990). Expanded and more authentic public participation is seen in the development of responses to climate change and are put forth by numerous non-governmental organisations (Schlosberg, Citation2007). Failures to engage in inclusive policy processes or to build strong and diverse political coalitions can contribute to inadequate policies that contradict sustainability goals (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2019). Sustainability and procedural justice are not always in conflict; highly deliberative and representative processes may result in more effective, ambitious and durable environmental policy (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2019).

Justice as recognition relates to the lack of recognition of relevant social and political actors, demonstrated by various forms of neglect, insults, degradation and devaluation at both the individual and cultural level (Schlosberg, Citation2007). Various types of misrecognition could occur, such as cultural domination, non-recognition, and disrespect (Fraser, Citation2008). Priorities, values and defined interests of the dominant social group are taken for granted and seen as reasonable and legitimate, while those of other groups could be systematically neglected (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2019).

Scholars of environmental justice extend distributive justice to concerns of various rights, goods and liberties, and how we define and regulate social and economic equality and inequality (Schlosberg, Citation2007). According to Ciplet and Harrison (Citation2019), in many cases strategies for environmental sustainability exist in tension with efforts to allocate economic and environmental resources and harms more equitably. For example, opportunities and benefits of resource distribution are typically on the side of the privileged, while burdens and harms are concentrated in marginalised communities. Justice represents a call for the even distribution of benefits and ills on all members of society regardless of class, income or race (Jenkins et al., Citation2016).

The conceptual framework of just transitions, including the three-part conceptualisation of justice as procedure, distribution and recognition, is used below to analyse the socio-economic support measures implemented in Boracay and their impacts on local tourism communities and the destination’s transition to sustainability.

Methodology

The research has an exploratory case study design, which is fitting in a research context where the intervention being evaluated has no clear, single set of outcomes (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008; Yin, Citation2003). The boundaries of the case study overlap with Boracay island, the Philippines, including its local inhabitants and tourism stakeholders. An overview of the research site, the data collection, and data analysis methods are provided below.

Research site

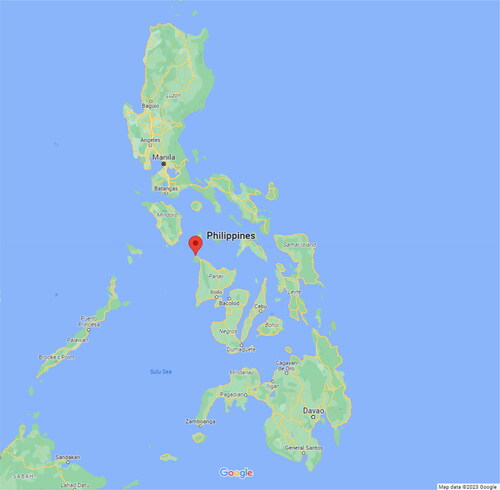

Boracay is a small tropical island of 10.3 km2, one of the more than 7000 islands in the Philippines (see ). The island is situated about 300 km south of Manila, in the Western Visayan region of the Philippines. It is under the jurisdiction of the municipality of Malay, which according to the 2015 census is home to 52,973 inhabitants and has a total land area of 67 km2.

Figure 1. Boracay island situated in the Philippines (the red pin north of Panay). Source: Map data © 2023 Google.

Boracay is important nationally as a flagship tourism destination. The tourism industry is one of the Philippines’ main sectors. In 2019, it accounted for 12.7% of the country’s GDP (Almazan, Citation2020). Tourism growth in Boracay is remarkable. In the early 2000s, Boracay attracted around 300,000 tourists yearly. This number doubled by 2008 to 634,363 tourists, generating 250 million USD for the Philippines’ economy (Ong et al., Citation2011). Less than a decade later, arrivals hit 2,001,974 with revenues surpassing 1 billion USD in 2017.

From 2018 onwards, bold sustainability projects have been implemented in the area. In a first phase, the Philippines’ president Rodrigo Duterte ordered a closure of Boracay to start large-scale projects to halt environmental degradation and initiate the transition to sustainable development on the island (Ranada, Citation2018). Non-residents and all tourists were denied access to the island for six months. The projects included the construction of new sewer systems and sewage treatment plants, carrying out beach clean-ups, removing illegal constructions in wetlands, introducing e-mobility and improving the road infrastructure. After re-opening the island, a second phase started which aimed at finishing projects and sustaining the improvements made. Stronger environmental regulations and new business practices were introduced, including a maximum visitor carrying capacity and stricter construction guidelines (PNA, Citation2018).

In the Philippines’ process report to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Boracay project is highlighted as ‘an example where the objective of leaving no one behind was integrated into making sure that economic progress does not come at the expense of environmental integrity’ (Voluntary National Review, Citation2019, p.16). Despite environmental gains, the socio-economic impacts of the transition on the Boracay community and the tourism sector have been drastic with the livelihoods of local communities highly dependent on tourism revenues.

Data collection

Primary data collection focused on community impacts regarding the sustainability intervention in two interaction modes: semi-structured interviews conducted through phone and Zoom, and an online questionnaire distributed through Qualtrics. This took place in 2020, about two years after the start of the rehabilitation, when the majority of interventions were completed. This data collection strategy was chosen to allow for a wide inclusion of stakeholders and community members in this study (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008; Boeije, Citation2009).

To understand the socio-economic impacts on the community, the target population included local tourism workers and business owners, NGOs, and government officials. Selection of respondents was based on both purposive and snowball sampling: contact details were collected through desk research, an official list of accommodation establishments on Boracay, and local social media groups. The interviews were conducted in English, while the questionnaire was available in both English and Tagalog, the two official languages of the Philippines. The average interview duration was 30 min, while the questionnaire took on average 20 min to complete.

The interview protocol and the online questionnaire included both open questions aimed at identifying key aspects of procedural justice, recognition, and distributive justice, as well as revealing what support and assistance in the sustainability projects was provided, and how. The questions were divided into three main sections: (1) communication and consultation by authorities, (2) the impact of the projects on personal life, and (3) the outcomes of the projects on Boracay and way forward.

Overall, the views of 37 respondents were collected, covering a wide range of opinions from a diversity of stakeholders (). Anonymity was assured; in discussing results a respondent code corresponding with a basic profile is used.

Table 1. Overview of respondents.

The research also included analysis of documentation, reflecting the measures implemented by the government during the rehabilitation phases of Boracay. Relevant government documents and news reports containing information on the socio-economic support provided on the island were collected. Government outputs from three Philippine government departments are included: the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA).

Data analysis

Out of the 16 oral interviews, 15 were recorded and transcribed verbatim. One interview was processed by the means of notes and converted into a summarising text. Answers to the questionnaire’s open questions were added to the transcription file. This transcription file consisted of over 40,000 words, and was analysed through thematic coding (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). The coding reflected the conceptual framework, with relevant information being categorised under the three-part conception. The primary and secondary data sources were compared and related to one another in the analysis (Denzin, Citation1978).

Just transition tensions on Boracay island

The analysis of the data resulted in a range of issues and tensions voiced by the respondents, along with gaps in government programs aimed to support affected communities. In the following paragraphs these issues are discussed, including the absence of social dialogue, tensions regarding land use, and distrust in future governance. It is also explained how they are related to the three dimensions of justice; i.e. procedural justice, recognition, and distributive justice.

Gaps in support measures and absence of social dialogue

Following the announcement of the policy intervention, authorities recognised the need to support vulnerable groups on the island and launched socio-economic support programs for local tourism workers and families. From government documents and news reports, a total of five programs have been identified (). Most of the measures were implemented during the first phase of sustainability projects which included the six-month closure of Boracay from April to October 2018.

Table 2. Overview of socio-economic policies. (numbers collected from PNA, Citation2018).

Despite the fact that the national government put in place several socio-economic policies, most respondents voiced that the distribution of the support did not sufficiently reach several vulnerable communities on the island, leading to distributive justice tensions. In addition, hotel owners emphasised they did not receive any financial compensation for their business income losses during the closure. National authorities blamed mostly the hotel industry for not following the environmental regulations and refused to provide financial assistance.

Larger hotels and resorts were generally in a better position to reopen for business, having more resources and capacity to deal with associated costs, such as seeking legal advice or investments to meet new sustainability standards. Because of this, the trend since the start of the transition has been that there is a shift from smaller businesses to larger hotels dominating the island economy. Out of the estimated over 400 accommodation establishments that operated before 2018, only 159 were able to reopen right after the closure (DENR, Citation2018).

There is frustration over large infrastructure projects being carried out on the island with little dialogue or consultation, and environmental permits becoming suddenly invalid which pushed many businesses to the edge of closing.

We criticized that they closed the island down without a big masterplan, especially a plan on how to handle all the people that are depending on Boracay […] So many local people lost their business and had to close down for good because they didn’t have the money to survive (ID12, environmental NGO).

From a distributive justice perspective, informal, small businesses and tourism workers were especially vulnerable in the process. With no formal status, this also implied that they could not count on full government support consisting of financial assistance. Further, a persistent issue is informal workers lacking access to education and training making them unable to compete with migrant workers from Manila and other major urban centres with relevant training and educational certificates. The local government is aware of the lack of education facilities and is developing a tourism college as part of the sustainability projects.

Because of qualifications it is hard for native people, they are not getting the standards of the big hotels […] You need 4 years, graduate or bachelor, but a lot of native people haven’t even finished school. So how can you work in these big companies? […] The natives, they need easy money. Go to the beach and talk to the guests and say that you will assist and guide. That’s easy money for them, but not for a lifetime. If you get in the hotel, it’s lifetime work (ID16, informal worker).

While environmental degradation has been an issue raised already in the 1990s, along with calls for strong action, the decision and start of the transition in 2018, especially the closure, came as a shock. This time pressure did not only shock the local community on Boracay, but it also implicated that government agencies themselves had a very short time to mobilise their workforce and to set up support mechanisms for the local community who lost their source of income.

In studying the socio-economic impacts of the transition on Boracay, interviews and the assessment of government policies revealed procedural justice concerns, including social dialogue and consultation being largely absent. Among tourism industry actors, there was predominantly a sense of frustration over not being consulted in planning. The interviews revealed that local knowledge was inadequately incorporated in the planning of the projects and there was limited engagement.

Consultation is NOT making decisions and then asking people to comment on them, it’s involving people in the decisions and listening to their ideas. It was also presented poorly to the community, without explanation of the impacts of any plans presented (ID19, business owner).

Land use tensions and trade-offs

Interview results revealed exacerbated tensions regarding land use on the island. A key component of the transition was to save the wetlands and the remaining forest lands. Hundreds of illegal structures have been removed which were located in these natural areas. The land use intervention on Boracay clashed with the interests of various groups, resulting into recognition tensions from a justice perspective.

The environmental measures meant that families had to relocate. The national authorities were careful regarding the indigenous tribes of Boracay, i.e. the Ati and the Tumanton. These communities have been on Boracay before settlers and expatriates came to the island. In total, 3.2 hectares of land was allocated to the tribes in 2020 (DAR, Citation2020). For decades, the tribes have been in legal disputes over land. From a recognition perspective, the developments since the government intervention from 2018 onwards is a step forward. In a government press release it was stated that ‘The government also wants social justice. We don’t just demolish the houses of people in Boracay. We make sure as well that they are given land where they can relocate’ (PNA, Citation2020).

Interviewees, however, stated that there are more land tenure issues beyond the indigenous families. The island has over the last decades become much more diverse, and many (non-indigenous) local villagers have been on the island for generations. The increase in the number of large hotels has displaced local villagers, while recent policy interventions also removed settlements in natural areas.

Here in Boracay that’s a very sensitive thing, the land ownership. There is the public land, the forest land where we do our reforestation. Then there is the private land, which is titled land […] So those sensitivities on titling, that should come first, before anything else, so that the locals can protect their properties (ID14, community organisation).

The national government focused on forest and wetlands. They declared that my village was forest land, but since I was born here I don’t see any big trees in the area. That’s why that is big bull**** of the national government. […] That was farmland, not forest land. […] I remember that land, my mother and my father planted here only root crops. They planted tobacco, cassava, or sweet potato. But there are no trees. Now the national government declared that this is forest land. What happened? (ID16, informal worker).

Connected to land use tensions is the introduced carrying capacity of the island. When Boracay reopened in October 2018, the national government imposed a daily carrying capacity of 19,215 tourists on the island, including a maximum of 6405 tourist arrivals per day. However, tourism stakeholders see this carrying capacity as problematic for running a profit and leading to economic damage, with potential impacts to small businesses again.

In my personal opinion, we are already quite over-developed. If I had the choice, we would mostly likely have to close some business. I just don’t think that the numbers that we have in any way lead to a long-term sustainable ecosystem for Boracay. (ID11, Business owner).

Because of the tensions between the number of operating hotels and the number of tourists that should be allowed to enter the island, it remains a challenge to calculate a carrying capacity that works well and accounts for the physical capacity of the island.

Distrust in authorities

Tourism businesses have declared scepticism about future developments, and the ways of engagement in decision-making. The absence of community engagement and land use trade-offs described in the previous sections created a basis of distrust in governance. Moreover, the discrepancies and disconnect between local and national governance approaches on the island have led to inconsistent policies.

Because of the timeframe, the government came in, brought in bulldozers, and said OK, well you have 48 hours to tear it down or we will tear it down. So, it was really that kind of, uh, strong wild implementation of the rules […]. And of course, as a business owner you would want to contest right, because you have a business permit. It was approved by the local government. But the national government wasn’t having anything of it (ID15, business association).

Interviews suggest that there is overall agreement about the need for intervention to save the island from further degradation and investments to push for sustainable development. However, the way that the national government intervened with minimal consultation with the local community caused many locals to voice procedural justice concerns. Furthermore, there exists distrust in how the national government will deal with land tenure in the future. A power shift from local management to the national government creates worries within the local Boracay community for being further away from decision-making processes.

Basically, the message of the president was that: you profited so much from Boracay already, you can fund yourself. That’s how they treated everyone, as everyone is so bad, you should pay for it, all of you. So, the government tried to help those who really needed the help: Workers who were displaced. But nothing, no aid was given to the businesses […]. It was very, very difficult for the establishments to survive (ID15, business association).

No one was prepared and a lot of people lost their businesses. Some people had to demolish their houses and businesses because of mistakes from the local government. Those people did not do anything wrong but lost everything and got no compensation. But as I said, the rehabilitation was really necessary so at the end we are happy that they took action (ID26, business owner).

To lead and facilitate the sustainability interventions, the national government established in 2018 the Boracay Inter-Agency Task Force (BIATF), which included various representatives from different government agencies. The responsibilities of BIATF have been extended several times and it remains in charge as of 2022 (PNA, Citation2022). Ongoing discussion remains on how sustainable development should be governed on Boracay. Plans to replace the BIATF by another authority are being made, which would similarly include representatives of government agencies, but also of local government, regional government, and the private sector.

Studies on the developmental challenges of Boracay prior to 2018 already emphasised the need for a shift in tourism planning and management, such as working towards mutual adjustments between stakeholders (Carter, Citation2004) and greater attention to social and cultural sustainability needs (Ong et al., Citation2011). Several interviewees have suggested a board with different types of stakeholders that can represent the multitude of issues on the island. This add-on to the current BIATF, or future planning authority, could include business associations, NGOs, scientists, and government agencies.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that substantial efforts are needed to overcome social justice issues and to alleviate tensions between environmental and socio-economic development goals in carrying out sustainability transitions in tourism destinations. This is in line with recent studies that argue that sustainability transitions should deliberately avoid reproducing the environmental and socio-economic injustices that are intrinsic to existing environmental resource use regimes (e.g. Agyeman et al., Citation2016; Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2019; Wang & Lo, Citation2021). For instance, the Boracay case demonstrates the demand for inclusiveness of local stakeholders in planning and implementing a long-term sustainable development path.

The Boracay case also clearly portrays the political choices in promoting sustainability in terms of whom to support and whom not, aligned with socio-political and justice-as-recognition concerns. While authorities invested in improved clean infrastructure and strengthened environmental regulations, they engaged inadequately with local stakeholders regarding knowledge, resources and capabilities. Undertaking sustainability actions with no representative decision-making of impacted constituents is what Ciplet and Harrison (Citation2019) classify as ‘sustainability exclusivity’.

Even though assessing improved environmental conditions of the policy interventions was not within the scope of this research, our paper makes it clear that to achieve a sustainability transition, Boracay still has to overcome multiple roadblocks. Tensions are seen between dealing with the carrying capacity of the island and the protection of natural areas and biodiversity, while managing livelihood impacts of the community and tourism businesses at the same time. The Boracay case underwrites the importance of systematically analysing local communities’ capacity and involvement in transition pathways and what destination power dynamics play in the pursuit of sustainable tourism (Gill & Williams, Citation2014; Niewiadomski & Brouder, Citation2022).

We argue that the six-month closure for sustainability action represented an important push for transition that will need many more years to consolidate. Transitions are long-term processes that can be stimulated with just tourism strategies integrated in interventions to support the local community and the tourism workforce. This is consistent with the views of transition researchers that sustainability transitions are typically long-term processes spanning generations (Loorbach & Rotmans, Citation2006). While government interventions and policy mixes are criticised to be merely promoting incremental change as opposed to transformative change, this does not necessarily have to be negative. Policymakers can focus on taking small steps which can contribute to creating new path-dependencies towards more desirable futures (Levin et al., Citation2012). With the sustainability interventions of the last few years, Boracay could very well have taken significant steps towards broader transformative change. It remains to be seen whether the intervention of 2018 represents a game changing event which enables the island and its community on a track for a more resilient and sustainable tourism future.

Boracay demonstrates that the radical policy intervention did result in environmental benefits to the island, but that it could have been more societally beneficial if just transition policies, land use and governance challenges were more thoroughly addressed. It could not have been foreseen that only two years later most tourism destinations had to face much longer COVID-19 related lockdowns. Globally, travel restrictions have spurred further discussions on the strategic opportunities and a reflection moment in the transition towards a more sustainable and equitable post-COVID-19 world (Barbier & Burgess, Citation2020; Benjamin et al., Citation2020: Lew et al., Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2022; Rosenbloom & Markard, Citation2020).

Introducing new innovative governance arrangements could help to address Boracay’s just transition tensions and to sustain the environmental gains for the future. A planning authority on Boracay advised by a board representing different stakeholder interests, would be a crucial step in guiding the continuation of sustainability actions on the island. It would have the potential to ensure socio-economic benefits are well-distributed and equity tensions are reduced. Boracay communities generally support sustainability measures but are concerned about being excluded from planning. An adaptive governance approach has been suggested as a way to respond to complex transition processes, with an emphasis on visioning, experiments, monitoring and evaluation, and reflexivity, in order to propose appropriate interventions (Turnheim et al., Citation2015).

Our research focused on tourism stakeholders present on the island two years after the closure of the island. The results thereby do not reflect those that had to leave the island. Future transdisciplinary research approaches could contribute to inclusion and dialogue, as it is based on inclusion of multiple academic disciplines and practice-based expertise in the knowledge production process (Lang et al., Citation2012; Polk, Citation2015). These approaches of enhanced community expertise and dialogue could aim at addressing specific tensions on Boracay over time, and improve practice-based knowledge in complex sustainability-tension areas connected to land use and governance issues.

The concepts of justice and just transition provide important considerations in implementing sustainability transitions and interventions in destinations. Moreover, the three-part justice conception of procedural justice, recognition and distributive justice (Ciplet & Harrison, Citation2019; Schlosberg, Citation2007) is a useful framework for identifying and analysing different socio-economic and governance tensions and provides an important theoretical contribution to the sustainable tourism transition literature. It offers practical and methodological guidance in reconciling sustainability transitions with justice challenges of tourism communities subject to policy action.

Conclusion

This paper analysed the impacts of a sustainability intervention on Boracay island in the Philippines from a just transition perspective. We conclude that a just transition lens proves valuable in revealing a broad range of socioeconomic impacts and tensions experienced during this sustainability intervention, and identifying lessons for future tourism planning on Boracay, as well as on other tourism dependent islands and destinations. Outcomes show that key tension areas are centred around the lack of social dialogue mechanisms, disputes regarding land use changes, and distrust in governance. In particular, procedural justice issues emerged in an island community that felt substantially ignored, unfairly treated and sceptical towards future actions in the area. Despite the fact that government programs were implemented to assist individuals, several gaps and limitations were identified, especially regarding a lack of targeted mechanisms to assist small tourism businesses. While it is not attainable to maximise support and opportunity for each single actor in the case study area, the absence of inclusivity mechanisms has limited the involvement of communities in sustainability actions and could hamper continued progress in sustainability. Designing more inclusive governance arrangements on Boracay would be a crucial step in continuing sustainability actions, in enhancing trust in authorities, and in alleviating tensions between multiple sustainable development goals.

A recommendation to policy design is to enhance assessments of just tourism transition aspects in planning, in particular on consultation and land use. The empirical results demonstrate that the focus should be broadened out beyond infrastructure and regulations, to include participation of locals in sustainability interventions and their involvement in decision-making regarding future development, to intervene with respect to the resources of individuals, and to enhance trust of local communities.

At the national level, governments have applied just transition conceptions to carbon intensive industries such as power generation, and more recently to agriculture. This study contributes to understanding the significance of incorporating just transition dimensions in the context of sustainable tourism transitions. Enhancing social dialogue, employability, and devoting resources to training and education are important elements that could drive tourism actors away from unsustainable behaviours and develop broader community support to contribute to a sustainable tourism future.

Ethical approval

According to the institutional requirements of Wageningen University & Research, no approval of an ethical committee is needed for the research conducted in this project since the research did not involve sensitive groups. Moreover, all subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

James Tops

James Tops is a Junior Policy Analyst at the Tourism Policy and Analysis unit of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 2020, he conducted research on Boracay, Philippines as a MSc student at the Environmental Policy Group of Wageningen University.

Machiel Lamers

Machiel Lamers is an Associate Professor at the Environmental Policy Group of Wageningen University in the Netherlands. His research interests are in the fields of environmental policy and governance, sustainable tourism, and nature conservation.

References

- Agyeman, J., Bullard, R. D., & Evans, B. (Eds.). (2003). Just sustainabilities: Development in an unequal world. MIT Press.

- Agyeman, J., Schlosberg, D., Craven, L., & Matthews, C. (2016). Trends and directions in environmental justice: From inequity to everyday life, community, and just sustainabilities. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41(1), 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090052

- Almazan, F. (2020, June 24). Tourism GDP contribution up 12.7% in 2019. The Manila Times. https://www.manilatimes.net/2020/06/24/business/business-top/tourism-gdp-contribution-up-12-7-in-2019/734185/

- Barbier, E. B., & Burgess, J. C. (2020). Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Development, 135, 105082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105082

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559.

- Benjamin, S., Dillette, A., & Alderman, D. H. (2020). “We can’t return to normal”: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759130

- Berkhout, F. (2002). Technological regimes, path dependency and the environment. Global Environmental Change, 12(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(01)00025-5

- Boeije, H. (2009). Analysis in qualitative research. Sage.

- Blythe, J., Silver, J., Evans, L., Armitage, D., Bennett, N. J., Moore, M., Morrison, T. H., & Brown, K. (2018). The dark side of transformation: Latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode, 50(5), 1206–1223. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12405

- Buckley, R. (2012). Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.003

- Burgos, N. P. (2017, December 18). ‘Worst flooding in Boracay’ due to ‘Urduja’ disrupts residents’ lives. INQUIRER.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/953461/urduja-boracay-flooding-evacuation-water-supply-storm

- Carter, R. W. (2004). Implications of sporadic tourism growth: Extrapolation from the case of Boracay Island, The Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 383–404.

- Ciplet, D., & Harrison, J. L. (2019). Transition tensions: Mapping conflicts in movements for a just and sustainable transition. Environmental Politics, 29(3), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1595883

- DAR. (2020, March 15). Indigenous People belonging to Tumandok and Ati Tribe in Boracay, now declared as agrarian reform beneficiaries. Retrieved from https://www.dar.gov.ph/articles/news/101462

- DENR. (2018, October 12). Cimatu lifts ECC suspension on ‘complying’ Boracay businesses. https://r6.denr.gov.ph/index.php/newsevents/press-releases?start=305

- Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Dobson, A. (Ed.). (1999). Fairness and futurity: Essays on environmental sustainability and social justice. OUP Oxford.

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fraser, N. (2008). Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, and participation." In Geographic Thought, pp. 72–89. Routledge, 2008.

- Geels, F. W., Sovacool, B. K., Schwanen, T., & Sorrell, S. (2017). The socio-technical dynamics of low-carbon transitions. Joule, 1(3), 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2017.09.018

- Goddard, G., & Farrelly, M. A. (2018). Just transition management: Balancing just outcomes with just processes in Australian renewable energy transitions. Applied Energy, 225, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.05.025

- Gössling, S. (2000). Tourism–sustainable development option? Environmental Conservation, 27(3), 223–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900000242

- Gössling, S., Hall, C. M., Ekström, F., Engeset, A. B., & Aall, C. (2012). Transition management: A tool for implementing sustainable tourism scenarios? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(6), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.699062

- Gill, A. M., & Williams, P. W. (2014). Mindful deviation in creating a governance path towards sustainability in resort destinations. Tourism Geographies, 16(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.925964

- Hägele, R., Iacobuţă, G. I., & Tops, J. (2022). Addressing climate goals and the SDGs through a just energy transition? Empirical evidence from Germany and South Africa. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 19(1), 85–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2022.2108459

- Harrahill, K., & Douglas, O. (2019). Framework development for ‘just transition’ in coal producing jurisdictions. Energy Policy, 134, 110990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110990

- Healy, N., & Barry, J. (2017). Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions: Fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy, 108, 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.06.014

- Heffron, R. J., & McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘just transition’? Geoforum, 88, 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

- Jenkins, K., McCauley, D., Heffron, R., Stephan, H., & Rehner, R. (2016). Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004

- Jenkins, K., Sovacool, B. K., Błachowicz, A., & Lauer, A. (2020). Politicising the just transition: Linking global climate policy, nationally determined contributions and targeted research agendas. Geoforum, 115, 138–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.05.012

- Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., Swilling, M., & Thomas, C. J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(S1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

- Leach, M., Rockström, J., Raskin, P., Scoones, I., Stirling, A. C., Smith, A., Thompson, J., Millstone, E., Ely, A., Arond, E., Folke, C., & Olsson, P. (2012). Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecology and Society, 17(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04933-170211

- Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45(2), 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

- Lew, A. A., Cheer, J. M., Haywood, M., Brouder, P., & Salazar, N. B. (2020). Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1770326

- Loorbach, D., & Rotmans, J. (2006). Managing transitions for sustainable development. In X. Olsthoorn & A. J. Wieczorek (Eds.). Understanding industrial transformation (pp. 187–206). Springer.

- Morena, E., Krause, D., & Stevis, D. (2020). Just transitions: Social justice in a low-carbon world. London: Pluto Press.

- Niewiadomski, P., & Brouder, P. (2022). Towards an evolutionary approach to sustainability transitions in tourism. In I. Booyens, & P. Brouder (Eds.). Handbook of innovation for sustainable tourism (pp. 82–110). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Newell, P., & Mulvaney, D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition’. The Geographical Journal, 179(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12008

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2022). OECD tourism trends and policies 2022. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en

- Ong, L. T. J., Storey, D., & Minnery, J. (2011). Beyond the beach: Balancing environmental and socio-cultural sustainability in Boracay, the Philippines. Tourism Geographies, 13(4), 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.590517

- Ordinario, C. (2019, January 3). Boracay closure cost: A high of P83 billion in business, P28 billion in wages’PIDS | Cai Ordinario. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2019/01/03/boracay-closure-cost-a-high-of-p83-billion-in-business-p28-billion-in-wages-pids/

- Patterson, J., Schulz, K., Vervoort, J., van der Hel, S., Widerberg, O., Adler, C., Hurlbert, M., Anderton, K., Sethi, M., & Barau, A. (2017). Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 24, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.09.001

- Peeters, P., & Landré, M. (2011). The emerging global tourism geography—An environmental sustainability perspective. Sustainability, 4(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4010042

- Philippine News Agency. (2018). Walkable, more livable Boracay island. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1056775

- Philippine News Agency. (2020). DENR to start restoration of another recovered wetland in Boracay. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1110409

- Philippine News Agency. (2022). Boracay task force’s term extended until June 2022. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1153540.

- Polk, M. (2015). Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures, 65, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.11.001

- Ranada, P. (2018, April 4). Duterte orders 6-month closure of Boracay. https://www.rappler.com/nation/199580-duterte-orders-closure-boracay-6-months

- Rosenbloom, D., & Markard, J. (2020). A COVID-19 recovery for climate. Science, 368(6490), 447–447.

- Rotmans, J., Kemp, R., & Van Asselt, M. (2001). More evolution than revolution: Transition management in public policy. Foresight, 3(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680110803003

- Saarinen, J. (Ed.). (2020). Tourism and sustainable development goals: Research on sustainable tourism geographies. Routledge.

- Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford University Press.

- Sharpley, R. (2020). Tourism, sustainable development and the theoretical divide: 20 years on. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1932–1946. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1779732

- Smith, A., Stirling, A., & Berkhout, F. (2005). The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Research Policy, 34(10), 1491–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.07.005

- Stevis, D., & Felli, R. (2015). Global labour unions and just transition to a green economy. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9266-1

- Swilling, M., & Annecke, E. (2012). Just transitions: Explorations of sustainability in an unfair world. Juta and Company (Pty) Ltd.

- Swilling, M., Musango, J., & Wakeford, J. (2016). Developmental states and sustainability transitions: Prospects of a just transition in South Africa. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 650–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1107716

- Trousdale, W. J. (1999). Governance in context: Boracay Island, Philippines. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 840–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00036-5

- Turnheim, B., Berkhout, F., Geels, F., Hof, A., McMeekin, A., Nykvist, B., & van Vuuren, D. (2015). Evaluating sustainability transitions pathways: Bridging analytical approaches to address governance challenges. Global Environmental Change, 35, 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.010

- Van der Ploeg, J. D. (2020). Farmers’ upheaval, climate crisis and populism. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(3), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1725490

- Voluntary National Review. (2019). The 2019 voluntary review of the Philippines. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/23366Voluntary_National_Review_2019_Philippines.pdf

- Wang, X., & Lo, K. (2021). Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291

- Wibeck, V., Linnér, B.-O., Alves, M., Asplund, T., Bohman, A., Boykoff, M. T., Feetham, P. M., Huang, Y., Nascimento, J., Rich, J., Rocha, C. Y., Vaccarino, F., & Xian, S. (2019). Stories of transformation: A cross-country focus group study on sustainable development and societal change. Sustainability, 11(8), 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082427

- Wieczorek, A. J. (2018). Sustainability transitions in developing countries: Major insights and their implications for research and policy. Environmental Science & Policy, 84, 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.08.008

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Design and methods. Case Study Research, 3(9.2), 84.

- Young, I. M. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.