Abstract

Issues with social and ecological sustainability in tourism should be seen as the result of widespread neoliberal policy making. This has led to tourism strategies that focus largely on growth of visitor numbers and spending. This paper investigates the transition to alternative strategies based on degrowth and regeneration, applying doughnut economics to urban tourism development. Action-oriented workshops were used as a research method. The workshops were offered to Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) and municipalities of seven cities in the Netherlands. Drawing from this method, this paper aims to investigate how and to what extent the doughnut economics model can be applied to an urban tourism context in order to facilitate a sustainability transition and what barriers are encountered in doing so. It also sheds light on the role academia can have in instigating change in practice. The results show that the doughnut model can be used in an urban tourism context to help DMOs and municipalities rethink their current strategies and replace them with more sustainable ones. However, even though the workshops made the majority of participating stakeholders question growth-based tourism strategies, neoliberal thinking often (unconsciously) prevails. The biggest barrier was found in the cultural dimension, underlining the argument that a sustainability transition in tourism can only happen if the mindset of the individual people in the tourism system changes (Grin et al., Citation2010; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). Future research could benefit from innovative research methods, for example by incorporating design thinking, to further facilitate such a transition in tourism.

Introduction

Growth-based strategies in tourism lead to several issues in urban destinations. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, many cities were struggling with the challenges that (growing) tourism brought. From a social perspective, issues related to excessive tourism, gentrification, touristification and the presence of short-term rentals have led to a wide range of impacts on tourist destinations (Jover & Díaz-Parra, Citation2020; Koens et al., Citation2018; Mansilla & Milano, Citation2018). Examples of this are Venice or Barcelona where the quality of life of residents and affordable/available housing cannot always be preserved. However, it is not only big tourist destinations who experience these issues. Smaller tourist destinations increasingly have to deal with challenges related to, for example, housing availability and peak pressure of high numbers of tourists in certain areas (Milano et al., Citation2019a; Peeters et al., Citation2018). In addition, the impact that travelling (to and within the destination) has on the climate and environment are highlighted often, which is mainly related to problems of global warming and air quality of destinations (Bramwell et al., Citation2017; Gössling & Peeters, Citation2015; Ruhanen et al., Citation2015).

Scholars argue that such unsustainability in tourism should be considered the result of widespread neoliberal and capitalist thinking where tourism is underpinned by politics of economic liberalization, deregulation, privatization and globalization (Fletcher, Citation2011; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Milano et al., Citation2019a; Niewiadomski, Citation2020). In practice, this mostly results in a focus on growth of visitor numbers and maximization of profit (Fletcher, Citation2011; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Milano et al., Citation2019a; Niewiadomski, Citation2020). For this reason, several scholars advocate a paradigm shift in the tourism discourse that focuses on degrowth and regenerative tourism to develop tourism more sustainably (see for example Ateljevic, Citation2020; Brouder, Citation2020; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Fletcher et al., Citation2019; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020a). This transition from developing tourism mainly based on neoliberal principles such as pro-growth-thinking and free-market capitalism, to more sustainable and conscious forms of tourism development has been going on for years, but seems to have been amplified recently by the COVID-19 pandemic (Hartman, Citation2022).

Much research has been conducted on sustainability transitions, however, little of that research has found its way into the sustainable tourism agenda (Niewiadomski & Brouder, Citation2022). In order to help address this gap, this research brings together knowledge from different disciplines about sustainability transitions to a tourism context. In fact, the paper aims to encourage a sustainability transition in tourism by using the model of doughnut economics in an urban tourism context. The doughnut economics model was developed by economist Raworth (Citation2017), and it replaces the growth of the economy as the ultimate goal of development with social and ecological objectives. As the doughnut model provides a clear visualization of all different aspects of both social and ecological sustainability, the model could aid destinations in developing holistic sustainable tourism strategies. Using doughnut economics in tourism has been suggested by several authors and is very much connected to the ideas of degrowth and regenerative tourism (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Hutchison et al., Citation2021; Sheldon, Citation2021; Torkington et al., Citation2020). A theoretical exploration has been developed by Hartman and Heslinga (Citation2022), but no empirical research has been conducted using the model in practice.

In this paper I thus aim to bridge the gap between theory and practice and shed light on the role which academia can have in instigating change in practice. In cocreation with seven Dutch destinations, I investigate the following research question: How and to what extent can the doughnut economics model be applied to an urban tourism context in practice with the aim of encouraging sustainability transitions, and what barriers are encountered in doing so? A form of participatory-action research was used by offering workshops to seven cities in the Netherlands. Participatory-action research is designed to foster action and real-world change, during which one dominant (unsustainable) worldview is replaced by a more sustainable one (Grin et al., Citation2010; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). By doing so, this research is among the first ones to apply the doughnut economics model in practice to an (urban) tourism context. With that I contribute real-life examples to a theoretical debate while simultaneously striving for a sustainability transition in practice.

In this paper I will first discuss the concepts of degrowth and regeneration in relation to a systemic change in tourism as well as the way doughnut economics can be used to facilitate sustainability transitions in tourism. Second, I will explain in detail the use of workshops as a research method, followed by the results section in which the insights gained during and after the workshops are described. The paper will finish with a discussion and conclusion section.

Degrowth and regenerative tourism require systemic change

Despite concerns about the impacts of unbridled tourism growth on cities, countering the dominant growth-oriented organisation of tourism destinations remains a challenge, especially since economic sustainability is often placed above all other forms of sustainability (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Torkington et al., Citation2020). Several strategies related to sustainable tourism have already been identified by multiple scholars. However, such strategies mostly focus on mitigating negative effects, among them diversification of the tourism product, dispersing tourism over time and space, stimulating green growth, offsetting carbon footprint and attracting the ‘quality tourist’. These strategies have been critiqued for being neoliberal in nature and considered as technical solutions or quick fixes that do not do justice to the issues at hand (Fletcher, Citation2011, Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Milano et al., Citation2019b, Torkington et al., Citation2020). These strategies are part of the current socio-technical system and unsustainability is often the result. Therefore, a radical shift to alternative systems is required (Coenen et al., Citation2012; Geels, Citation2011; Köhler et al., Citation2019). In other words, a sustainability transition, where one worldview is replaced by another, leading to large-scale societal changes with the goal of sustainability (Grin et al., Citation2010; Loorbach et al., Citation2017), needs to occur. Without a change in the tourism system, sustainable development cannot happen (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2010b).

With tourism brought to a standstill, the COVID-19 pandemic, could be considered a moment for change in which the tourism sector could move away from growth-based strategies and become sustainable (see for example Brouder, Citation2020; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020a; Ioannides & Gyimóthy, Citation2020; Niewiadomski, Citation2020). There are several ideas offered by both academics and practitioners of what this sustainability transition should look like. They advocate moving away from the current system towards one that is based on degrowing tourism and regenerative practices (see for example Ateljevic, Citation2020; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Bellato et al., Citation2022; Pollock, Citation2019).

The idea of degrowth was introduced in tourism for the first time about a decade ago by Hall (Citation2009) and Higgins-Desbiolles (Citation2010a) and has been recently picked up by several other scholars as an important strategy for countering the unsustainable development of tourism (see for example; Fletcher et al., Citation2019; Higgins-Desbiolles et al., Citation2019; Milano et al., Citation2019b). Degrowth refers to a process where society moves away from a growth-based economic paradigm and where social well-being and ecological sustainability are at the core of the development model instead (Kallis, Citation2011; Latouche, Citation2004).

Another concept in tourism that puts social and ecological values before financial gains is that of regenerative tourism. Even though it is not often discussed together with degrowth in the literature, both concepts seem to have much in common. Regenerative tourism combines several principles. Instead of minimizing negative impacts of tourism, as is often the case with sustainable tourism which has been exemplified above, the focus is on moving away from capitalist thinking. Regenerative tourism does not seek solutions in the current (neoliberal) worldview but strives for a new tourism system in which tourism growth is not the goal in itself, but instead is a means for achieving other sustainable goals (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020b). Instead, the aim is to create a net positive impact. A place is left better than it was before the visitor arrived, for example, by restoring nature through tourism (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Dredge, Citation2022; Matunga et al., Citation2020). The origins of regenerative thinking trace back to Indigenous wisdom where an ecological worldview is applied to tourism systems. This means that tourism systems are considered inseparable from nature and the well-being of a place and its people (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Matunga et al., Citation2020). Regenerative tourism holds a lot of potential to change tourism systems, however, as is often the case with newly emerging concepts, there is also the risk of misuse of the term for ‘greenwashing’ purposes (Dredge, Citation2021). One of the more extensive critiques of regenerative tourism comes from Bellato et al. (Citation2023) who have pointed out that both practitioners and academics often fail to offer a thorough understanding of the concept of regenerative tourism. The ontological roots of regenerative tourism are not always addressed and the framing of tourism development therefore remains limited to (reproducing) a Western and neoliberal approach (Bellato et al., Citation2023).

Doughnut economics as an innovative tool for facilitating sustainable transitions in tourism

It is argued that tourism needs to embrace new economic models to achieve system change (Sheldon, Citation2021, Cave & Dredge, Citation2020). Doughnut economics developed by Raworth (Citation2017) is such an alternative economic model that is considered to be part of regenerative economics (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020) and could be used to facilitate the transition to an alternative (economic) system in tourism (Sheldon, Citation2021). For this research, I chose this model because it unites the ideas of degrowth, regeneration and to some extent Indigenous knowledge. For that reason, it has been proposed by several scholars as a valuable model to be applied to tourism (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Hutchison et al., Citation2021; Sheldon, Citation2021; Torkington et al., Citation2020).

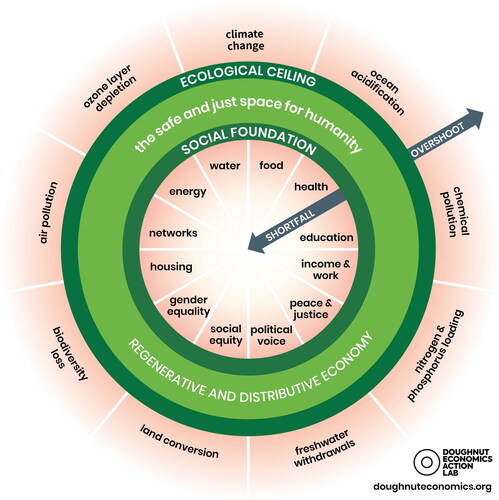

The most important premise of the doughnut model is that a neoliberal and growth-driven economy is replaced with a focus on social wellbeing and ecological sustainability represented by 21 sustainability aspects that are positioned in either the social foundation or the ecological ceiling, as can been seen in . The inner ring of the doughnut represents the social foundation, i.e. facilities that everyone should have access to, such as a fair income, a good living environment and a safe environment. On the outer part of the doughnut, the ecological ceiling can be found (). The ecological ceiling is often exceeded in our current society as a result of increasing prosperity which has consequences such as climate change and high levels of air pollution. One of the main ideas of the doughnut economics model is that a balance is struck between prosperity and the climate instead of focusing primarily on economic growth. The model shows that if a society wants to be sustainable, it should not fall short in the social foundation and at the same time should not exceed the ecological ceiling. Between these two boundaries is the safe and just space for humanity (see ).

Figure 1. The doughnut of social and planetary boundaries.

Credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier. CC-BY-SA 4.0. Source: Raworth, Citation2017.

In order for societies to move into the safe and just space, seven principles have been developed to reconfigure our current economic thinking (Raworth, Citation2017). These seven principles are: 1) Change the goal (from growing GDP to doughnut economics), 2) See the big picture (an embedded economy instead of a self-contained market), 3) Nurture human nature (considering humans as socially adaptable as opposed to rationally economic), 4) Get savvy with systems (from mechanical equilibrium to dynamic complexity), 5) Design to distribute (replacing the idea that growth will even up with being distributive by design, 6) Create to regenerate (replacing the idea that growth will clean up with being regenerative by design, and 7) Be agnostic about growth (moving from being growth-addicted to growth-agnostic). Without going into the specific details of these seven principles it is relevant here to mention that Hartman and Heslinga (Citation2022) have connected these principles to a tourism context, showing that many current lines of thinking in tourism, such as the aforementioned regenerative tourism and transitions thinking, can be connected to the principles of the doughnut.

With doughnut economics, economic importance coincides with social sustainability (as factor income and work) and is therefore seen in this model as a means and not as an end in itself. The model of doughnut economics thus differs from the well-known people, planet, profit model, in which financial interests have a separate role and therefore often weigh heavily in discussions about sustainability. Furthermore, the strength of the doughnut model lies in its clear visualization of the different sustainability aspects and the balance that needs to be sought after to maintain a sustainable equilibrium. At the same time the model has been critiqued for only focusing on limits to pollution when it comes to the ecological ceiling and not including depletion of natural resources as a factor (Bardi, Citation2017). This is a valid critique especially since it is one of the main principles of regeneration to not exploit natural resources but instead to restore them (Dredge, Citation2022). Taking this into account, I believe the doughnut economics model still provides a valuable tool in tourism to set in motion a process of rethinking the existing tourism system.

Many of the issues we find in tourist cities can be connected to the doughnut model, placing for example overcrowding, a shortage of affordable and available housing, and a loss of city culture on the shortfall side of the social foundation. Issues such as high CO2 emissions due to transportation to and within the city, as well as excessive use of water can be placed on the overshoot side of the ecological ceiling of the doughnut. While other models related to sustainability transitions, such as transition management (TM) and the Multi-Level Perspective (MLP) provide useful conceptual frameworks for analysing sustainability transitions on a broader level, the doughnut model provides a more concrete visualisation of sustainability in practice. At the same time, the doughnut economics model can also be applied to study, or in this case, facilitate change on a more local level (i.e. cities). For this reason, the doughnut model seems more suitable to use in the action-oriented workshops of this research. This also supports the endeavour of working on instigating change in practice which is considered much needed when it comes to transitions in tourism (Bellato et al., Citation2023).

Within the context of degrowth, other authors have applied doughnut economics in a conceptual manner as well, developing, for example, a theoretical framework for understanding sustainable wellbeing in cities, or evaluating local operability of the doughnut model (see for example, Cash-Gibson et al., Citation2023; Ferretto et al., Citation2022). In empirical research the doughnut model has mostly been used to map out and measure sustainability aspects from the doughnut such as inclusive mobility or social and ecological boundaries in a broader sense (see for example Roy & Pramanick, Citation2018; Virág et al., Citation2022). However, a research design that actively integrates the doughnut model as a workshop tool to facilitate a sustainability transition does not seem to exist. Using the doughnut model in a research workshop format can help shed light on the role of academia in instigating change. The lack of collaborative and interdisciplinary research between societal actors and scholars towards regenerative actions in tourism has also been identified as an existing gap in academic research by Bellato et al. (Citation2023). In this paper I address this gap by being among the first ones to apply the doughnut economics model in practice to a tourism context by making use of workshops with stakeholders from seven different tourist cities in the Netherlands. The specifics of the research design are explained in detail in the following section.

Research design

The research design aims to fulfil two roles at the same time: achieving a goal (encouraging a sustainability transition in urban tourism) and revealing new perspectives and knowledge on using the doughnut economics model in an urban tourism context. For this reason, action-oriented workshops were used as a research method (Wittmayer & Schäpke, Citation2014). The advantage of workshops as a research method is that ‘while observations provide first-hand evidence of what people do and interviews offer access to inner thoughts and the reasons for actions, workshops combine a little of both without being either’ (Ørngreen & Levinsen, Citation2017, p. 78).

As is common in explorative and qualitative research, non-probability sampling methods were used. Five cities were selected via purposeful sampling using the researcher’s professional network (Bryman, Citation2016). The two remaining cities were gathered via voluntary response sampling following a LinkedIn message posted by the researcher. In all cases the workshop was advertised as seeking to investigate the applicability of the doughnut model in sustainable tourism development. Selection criteria were limited and consisted of being a destination marketing organisation (DMO) or municipality of a city in the Netherlands with an interest in developing tourism more sustainably. No other criteria were used as it was an open call for any city in the Netherlands dealing with the topic of sustainable tourism development. Furthermore, the research ensured to include different types of urban destinations varying in size, population, geographical location, type of city (e.g. historical or modern city) and tourism maturity. As issues related to tourism are not only found in the most famous destinations anymore (e.g. Amsterdam) but also lesser known cities or small towns (Milano et al., Citation2019a; Peeters et al., Citation2018), this was deemed important for this research to generate insights from a variety of cities.

An important aspect of the workshops is its co-creative aspect, where participants are involved in the design process of the workshop and the outcomes of it. The idea behind this is that an outcome is thought off that no one would have individually come up with (Stompff, Citation2018). Before each workshop, the representatives of the city dealing with the topic of sustainability (usually one or two people) were asked what they would like to get out of the workshop and what their current challenge regarding sustainability was at that moment. This coincides with the analysis phase of cocreation where existing problems and desired solutions are investigated (Stompff, Citation2018). Based on this input, the workshop design can be divided into two categories: either workshops were offered to cities that already had a vision or strategy that included sustainability, or to cities that were still in the development phase of defining sustainable strategies. The contents of the workshops did not differ, but they did have different outcomes: either an action plan or a baseline for developing a sustainability vision.

As part of the co-creative process, who should be included in each workshop was left to the organisation itself. All the cities involved decided on doing the workshop within their own organisation first, without including external stakeholders. The number of participants ranged from four to eleven, often depending on the size of the organisation (the bigger the organisation, the more people participated in the workshop). Participants had different functions within the organisation. In the case of the DMOs there was usually a mix of (vice-) directors, online- and content marketeers, data and research analysts, and sustainability strategists. In the case of the two municipalities civil servants from different departments such as tourism, recreation, circularity and urban planning were involved. An overview of the seven involved cities and their characteristics can be found in .

Table 1. Overview of participating cities.

The workshops were offered in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, in July 2021 (one pilot workshop), November/December 2021 (five workshops) and March 2022 (one workshop delayed due to COVID-19). Action research with the aim of sustainability transitions is not value-free, therefore the researcher remained self-reflexive throughout the research period (Wittmayer & Schäpke, Citation2014). Three workshops were held at a physical location arranged by the organisations involved in the respective cities. The other four workshops were held online due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic using Microsoft Teams and the online whiteboard tool Miro. Each workshop lasted between two-and-a-half to three hours. As only one researcher was present during the workshop, all workshops were video recorded to allow for analysis afterwards. Finally, workshops were transcribed and analysed, using thematic analysis, following the general guidelines of qualitive data analysis (Bryman, Citation2016). Conversations held before the workshops, as well as the tables developed after the workshops were also included in this analysis.

Each workshop consisted of two theoretical components: 1) Introduction to doughnut economics, and 2) applicability of the doughnut model in tourism. This was followed by three brainstorming sessions using the doughnut model as a template (see ). During the plenary brainstorm session, a first exploration of the doughnut in relation to tourism was done by using one specific aspect of the doughnut (air pollution) and asking in what ways it is possible to contribute to counter this in a tourism context. This exercise was followed by the question of what the organisation (either DMO or municipality) could do in practice to contribute to this (e.g. can a DMO contribute to having more people using bikes in the city?). The aim of this first brainstorming session was to get a sense of how to connect the doughnut to a tourism context and which tasks the organisation could take on in that respect. Based on this first session, the second brainstorming round was expanded to all the different aspects of the doughnut. Before starting this session, participants were asked to jointly mention which sustainability aspects of the doughnut they would like to prioritise. Participants were then asked to individually write down as many ideas as possible as to how their organisation could contribute to any of the aspects of the doughnut model. This includes both social and ecological sustainability aspects. A final brainstorming session was done in break-out groups of three to four people, where the participants were asked to reflect on the different plans and make a list of their top three to five ambitions (depending on the number of participants). These sessions are part of the idea generation phase of cocreation (Stompff, Citation2018). These plans were then written down on post-it notes, placed on the doughnut template and presented to the other participants. In a final plenary session, these plans were discussed by the other participants. The plans were also compared to the earlier established priorities, and the researcher asked if they felt the different aspects of the doughnut were sufficiently represented or if something was still missing—the reflective phase of cocreation (Stompff, Citation2018).

Outcomes of the workshop were processed by the researcher and translated into a table with an overview of the plans for each destination, structured per theme and aspect of the doughnut. Consequently, these tables were shared with the participants who could develop further action steps to either work out a sustainability vision or some first action steps towards implementing sustainability. This means the realisation phase of cocreation is left to the individual participants of the workshop (Stompff, Citation2018).

Results & discussion

Doughnut economic workshops to stimulate regenerative and degrowth thinking in tourism

During the first plenary brainstorming session where participants were asked to come up with plans to counter the ‘air pollution’ aspect from the doughnut model, many suggestions were brought forward. These ranged from eating less meat, to using renewable energy and using fewer cars in the city. At first, many of the participants seemed slightly hesitant on how either the DMO or municipality could contribute to such suggestions, but eventually for almost all ideas a specific plan was developed (for example, stimulating partners to have meat-free options on the menu, using solar energy in their own buildings and promoting sustainable transportation options). Despite sometimes having a slow start with coming up with ideas, in the end, most cities had at least fifteen ideas on how to contribute to countering air pollution as a DMO or municipality. Realizing that this was only one of the aspects of the doughnut gave them confidence (e.g. ‘more things are possible than previously thought of’), but in some cases it also led to a feeling of overwhelm (e.g. ‘there are so many things that we have to do’). When asked which aspects of the doughnut the participants deemed most important for their city at the start of the second brainstorming session, countering climate change and air pollution were most often mentioned as aspects from the ecological ceiling. From the social foundation, contributing to work and income was most often mentioned as a priority, followed by social equity. It is interesting to notice that issues related to gentrification and housing were hardly ever mentioned, even though this is an often-cited problem in tourist cities, especially in relation to Airbnb apartments (Cocola-Gant, Citation2016; Gravari-Barbas & Guinand, Citation2017).

After the individual brainstorming session about plans to contribute to all the different aspects of the doughnut model, the third session in break-out groups was initiated. During this session it turned out that within one organisation, the receptiveness to the doughnut model and underlying ideas such as degrowth differed amongst the participants. Some participants were continuously stressing the importance of economics and arguing that sustainability measures were most likely too expensive or not realistic, whereas others were more idealistic and believed in the potential of the doughnut model to help them rethink sustainability strategies in tourism.

Based on these brainstorming sessions, post-it notes with plans were distributed over the doughnut template. It was often mentioned that one plan touched upon several aspects of the doughnut, thus combining social and ecological aspects, which is, in fact, one of the very aims of the doughnut model. This also somewhat eased the feeling of overwhelm as it became clear that one plan could contribute to multiple sustainability aspects of the doughnut model.

Even though the doughnut economics model is regenerative in its ideology, looking at the character of the plans, it turns out that many plans mostly focus on mitigating negative effects by compensating CO2, spreading tourism over the city, or attracting the ‘tourist that fits with the identity of the city’ or ‘sustainable’ tourist, which is in line with neoliberal thinking rather than being regenerative in nature (Fletcher, Citation2011, Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2018; Milano et al., Citation2019b, Torkington et al., Citation2020). This indicates that thinking about sustainable tourism mostly happens in the current socio-technical system (Köhler et al., Citation2019). At the same time, in all types of cities (but mostly in the bigger cities) there are also plans that take a more holistic approach and aim to use tourism as a tool to achieve broader city goals (such as countering climate change or increasing liveability) instead of attracting tourism mostly with the purpose of increasing tourism numbers. Examples of this are recovering nature, using tourism to develop or improve facilities and infrastructure in certain neighbourhoods or creating a fund where tourism spendings are directly invested in social projects in the city. In this case there are aspects of degrowth and regeneration such as social wellbeing and ecological sustainability that are prioritised over economic growth (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Kallis, Citation2011; Latouche, Citation2004;). Tourism is seen more as a means rather than being an end goal in itself which aligns with degrowth and regenerative thinking. However, at the same time, the projects are more or less isolated and do not necessarily demonstrate a broader strategy or net positive impacts for the destination (Bellato et al., Citation2022; Cave & Dredge, Citation2020; Matunga et al., Citation2020).

There is thus a mixture of strategies that came out of the workshop. On the one hand, there are strategies underpinned by the neoliberal ideology that aim to mitigate negative impacts, while on the other hand, some strategies indicate potential first steps to a transition in tourism into more regenerative forms of tourism.

Barriers to a sustainability transition based on doughnut economics

During the workshops, several barriers were identified which hinder the implementation of the plans based on the ideology of the doughnut model and thus are in the way of facilitating a sustainability transition in tourism. To structure these barriers, I borrow the categorization for implementing sustainability in organisations from Stewart et alia (2016). Applying it to the context of tourism, the barriers to realise the ‘doughnut plans’ are divided into external and internal. External barriers are related to the sector (Stewart et al., Citation2016). During this research the following external barriers were found in the tourism sector: the belief that other stakeholders are not always willing to cooperate towards sustainability, the belief that other stakeholders are responsible for a sustainable transition in tourism, a lack of sustainable infrastructure, and a lack of regulations that facilitate sustainable development in the tourism sector (see ). The latter three barriers were mostly identified amongst the DMOs in this research. Questions were raised about which plans related to the different aspects of the doughnut model could be implemented by the DMO, as it is ambiguous if tasks such as product development and the refusal of unsustainable activities or partners belong to the DMO. Some participants argued that the role of the DMO is to transition from having a marketing-only function to destination management that includes such tasks, but it is not always clear to what extent they can execute them. In some cases, these activities would also require support or legislation from the municipality or other governmental bodies, which lies outside the scope of the DMO.

Table 2. Internal and external barriers faced by DMOs and municipalities.

That is actually precisely always the difference between the marketing organisation and the Municipality. The Municipality actually indicates what is not possible, that is indeed based on the restrictions, which are about keeping out. And we are about encouraging and rethinking what is possible. So you could make a [web]page that stimulates sustainable options with which you immediately also keep out cars, but of course not so literally.—Employee DMO

At the same time, there are barriers that can be categorized as internal to the organisation. These internal barriers can be placed in what Stewart et alia (2016) have described as the political, human, structural, and cultural dimensions of organisations, a categorization that they distilled from organisational studies (Bolman & Deal, Citation2008). Internal barriers that were identified during the workshops that fit into the political and human dimension are: not having enough time or resources, not knowing where to start (feeling overwhelmed) or not knowing which decision would be the most sustainable option (lack of knowledge and expertise) (see ). It is important to note here that, even though these are real barriers to the implementation of more sustainable tourism developments, the abovementioned external and internal barriers can sometimes also be (unconsciously) turned into arguments to justify unsustainable choices.

Furthermore, even though the dependence of the DMO on the municipality can be considered an external barrier, it can also be placed under the structural dimension. Considering the way in which the DMO is organised and the tasks that they are assigned, one director of a DMO in this study mentioned: ‘this goes so much into how we [the DMO] are organized and what agreements lie underneath’. It is therefore also argued that the shift from DMOs as Destination Marketing Organisations should further evolve into destination management to be able to fully contribute to realizing a sustainable form of tourism based on the doughnut model.

A: (director DMO): ‘yes, product development, you must be assigned that role, or you must take on that role. I think we are at a tipping point as a DMO that we are also allowed to do that from the municipality and partners.

B: (employee DMO): ‘yes and that is much more of a role through which you can really make a difference instead of just promoting what is already there’.

A: ‘But at the moment that is not possible for us, but also [not] for many other DMOs, within your existing KPIs and agreements that you have’.

The quotes above reveal the problem of defining Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) as a barrier related to the structural dimension of DMOs. Currently, DMOs are mostly evaluated by their ability to attract (a higher number of) visitors and visitor spendings, an indicator set by the municipality. In order to fully embrace and implement the doughnut model at a destination, other KPIs would need to be set, as the current KPIs are not fit for alternative economic models that move away from growth. However, apart from their dependence on the municipality for doing this, the issue is raised of not knowing what indicators could be used, and even more so, how they could be measured.

Finally, the cultural dimension of the organisation refers to the meanings, beliefs and faith of people within the organisation and how humans make sense of this world (Stewart et al., Citation2016). This is considered to be a crucial factor in sustainability transitions (Stewart et al., Citation2016). Without a change in the way people think about tourism in relation to social wellbeing, ecological sustainability and economics, a sustainability transition to regenerative forms of tourism cannot happen (Grin et al., Citation2010; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2010b; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). In this study, neoliberal and capitalist thinking, as part of the current tourism system, has been identified as a barrier for implementing sustainability plans in tourism based on the doughnut model. This way of thinking was found throughout the workshop in several ways. As already mentioned above, the income and work aspect from the doughnut was most often prioritised when it comes to the social sustainability. Prioritising economics presented itself when discussing other choices regarding sustainability as well. In many instances sustainability was directly paired with (economic) growth.

(…) the most important thing is that more people just come to your city. But how do you do that in a way that does not violate your longer-term goals and you have more sustainability and ecological goals? And there can be tension there, (…) but how do you deal with that? - Director DMO

This way of economic thinking is also thought to be present with other stakeholders. Related to the external barriers described above, the most cited reason as to why other stakeholders would not want to engage with sustainability are financial motivations. Most cities in this research are under the impression that many visitors, entrepreneurs and even municipalities are not willing to engage with sustainability if there is no financial incentive. Furthermore, this research identified the aforementioned neoliberal strategies that mainly aim at mitigating negative effects instead of degrowth and regeneration. Finally, sustainability is often seen as a way to improve the competitive position of the destination and is used for branding purposes (e.g. Greenest city of the Netherlands). This appears to be rather common in policies that deal with the sustainable development of tourism where social and environmental objectives are often considered as being instrumental to economic goals rather than end goals in themselves (Torkington et al., Citation2020). Even though the participants consider sustainability as an important aspect, it was not always prioritised during the workshops where neoliberal thinking prevailed.

In some cases however, participants said they would consciously use the old economic rhetoric to negotiate with other stakeholders to engage them in sustainability and convince them of using the doughnut model to achieve that.

The municipality has a question with regard to water recreation. So, there will certainly be an assignment from them to make a navigation map or… we are now also holding that off a bit because I think that is a more public task (…). But we can also say we turn it around, we want to approach it from doughnut economics and so we use such a project as a distinctive value to put the city on the map. Then it suits us again. – Director DMO

Despite these negotiating tactics to put sustainability on the agenda, a bigger shift is needed as these strategies still perpetuate and reproduce neoliberal and capitalist thinking (Torkington et al., Citation2020). Using the doughnut model as a tool to convince other stakeholders to engage with sustainability could, controversially, lead to higher visitor numbers and spendings, which goes against the principles of what degrowth and regenerative tourism look like. Being instrumental to promoting ‘a new kind of capitalism’ is precisely what the doughnut model does not intend to be (DEAL, Citation2022). For a transition to happen towards degrowth and regeneration, the whole paradigm needs to shift. Using the doughnut model based on rhetoric that is part of the current economic system, might lead to short-term sustainable solutions, but will be unlikely to foster systemic change in the long run.

Conclusion

In this research I have demonstrated that the doughnut model, presented in research workshops, can serve DMOs and municipalities as a tool to envision sustainability in a more concrete and comprehensible way. After the workshops, almost all destinations had a better idea of which aspects could be included when working on sustainable tourism development. It also enabled them to develop concrete ideas that are aligned with multiple aspects of the doughnut model, combining both social and ecological sustainability. However, even though the workshop made the majority of participating stakeholders question the idea of growth as the main objective of tourism development, the principle is at the same time not easily abandoned, and neoliberal thinking often prevails.

Despite that, following the COVID-19 pandemic, there are some cities that indicate making some first steps towards more sustainable and regenerative forms of tourism based on doughnut economics, hinting at a transition to a new tourism system. However, at the same time, multiple external and internal barriers have been identified in this research that hinder the cities in doing so. Examples are the dependence on other stakeholders to take responsibility or the lack of money and knowledge. It thus seems that even though sustainability is deemed important and plans are made based on the doughnut model, in practice they might not always be implemented due to such barriers. These barriers could be overcome with a mindset that prioritises sustainability aspects as mentioned in the doughnut model. In this research I thus emphasized reflections presented in previous literature on transitions, that a sustainability transition in tourism can only happen if the tourism system itself and the mindset of people in it change (Grin et al., Citation2010; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). This research further demonstrates that only when destinations rethink their purpose and align it with the ideology behind doughnut economics, a sustainability transition in (urban) tourism can truly happen. It is also only then that changes can be made in the other dimensions, such as reserving additional money for sustainability purposes and the redefining of KPIs.

Limitations & suggestions for future research

A transition in thinking of people and organisations towards sustainability is a complicated and lengthy process (Köhler et al., Citation2019) which is not easily achieved with a one-time intervention. For that reason, the workshops offered in this research seem to be mostly beneficial for making concrete plans to contribute to aspects of the doughnut model and understanding different sustainability aspects. It was however more challenging for participants to completely adopt the ideology of doughnut economics. The workshops thus may have planted the first seed towards rethinking tourism, but a true sustainability transition remains a challenge for the future. Dredge (Citation2022) has recently argued that facilitating such a change is most effective when it starts from the individual. I thus recommend that future research also pays attention to the idea of shifting mindsets of all stakeholders involved. Furthermore, as there is no follow-up moment, one can only speculate if the realisation phase of cocreation is truly entered by the participants of the workshop. Will the involved cities go back to business as usual, or will somebody take on the responsibility and make concrete steps towards a transition? It is also important to reflect on co-creation in research and the role academia can have in sustainability transitions in practice. It needs to be questioned if it is possible to speak about cocreation when the cocreation ends after one session. Therefore, for future research I encourage a longitudinal research approach with multiple intervention moments. To integrate the abovementioned points, I do believe academia can have an important role in facilitating sustainability transitions by using more innovative research methods that for example incorporate design thinking into the research design.

Second, looking at the existing literature on sustainability transitions, it is stressed that such a transition requires multi-level change, meaning different stakeholders and levels of governance need to be involved (Geels, Citation2011; Köhler et al., Citation2019). This paper has only focused on the level of municipalities and DMOs as preferred by the participating cities. This is an interesting finding in itself as it demonstrates the lack of initial openness to collaboration for sustainability purposes, while the importance of this has been stressed in literature numerous times (see for example Bramwell & Lane, Citation2000; Graci, Citation2013). Future research could take a broader approach and include stakeholders from all levels including residents, entrepreneurs, regional and even national government representatives. In addition, regarding municipalities and other governmental bodies, I recommend to not only include representatives working on tourism directly, but also other departments such as housing, infrastructure, culture, etcetera. With regard to the role of the DMO transitioning to destination management, I suggest more research into destination governance with a focus on realising sustainable development. What is required for this structural transition? And how can it foster sustainable development of destinations?

Finally, I suggest that research on sustainability transitions in tourism could benefit from the advancements made in other disciplines, particularly those where the issue of implementing sustainability in practice has been addressed. This knowledge could then be applied to a tourism context to gain better insights into the barriers encountered when facilitating sustainability transitions and how to overcome them (see for example Álvarez Jaramillo et al., Citation2019; Elmualim et al., Citation2010). Such a sustainability transition based on doughnut economics will eventually also require setting new objectives and finding alternative metrics for what it means to be a successful tourism destination. This challenge is not unique to the tourism sector, as other industries are equally struggling with finding adapted performance measurement systems (Stewart et al., Citation2016). It is thus recommended that an exploration is made of potential metrics that could be used in an alternative economic paradigm, both in tourism and beyond.

Even though this research comes with some limitations, it has served as a first exploration into the applicability of doughnut economics in an urban tourism context as well as identifying the barriers for achieving a sustainability transition in urban tourism based on this model. As this research formed a first inventory into generating insights from different types of cities, identifying differences or drawing comparisons between the cities was complicated. This could be expanded upon by including more cities that experience higher pressures from visitor numbers, as well as other types of destinations (e.g. coastal or rural) and contrast the findings.

Ethics approval

This research meets ethical guidelines and adheres to the legal requirements of the study country. The research set-up has been approved by the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Ethics Review Board. The related ethics approval number is 19-30.

Acknowledgements

First some words of appreciation for the cities that were willing to invest time in this explorative and somewhat unconventional research project. A special thanks goes to Amanda de Nijs from Insiders for helping me connect to three of the participating cities in this study. I would also like to thank the attendees of the ATLAS SIG meeting on Urban Tourism in Helsingborg for their valuable discussions that helped shaped the final sections of this paper, as well Stefan Hartman and Jasper Heslinga for the feedback on the concept version of this paper. Finally the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on later versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shirley Nieuwland

Dr. Shirley Nieuwland obtained her PhD at Erasmus University Rotterdam in 2022. During her time at Erasmus University, she studied the complex dynamics of urban tourism and how to improve its sustainability both in a social-cultural and ecological way. Her research interests include gentrification, creative tourism, vacation rental apartments, sustainability transitions, and regenerative tourism. Currently, Shirley continues working with these topics as an independent researcher and freelance advisor from her company Paradise Found Consultancy.

References

- Álvarez Jaramillo, J., Zartha Sossa, J. W., & Orozco Mendoza, G. L. (2019). Barriers to sustainability for small and medium enterprises in the framework of sustainable development—Literature review. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(4), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2261

- Ateljevic, I. (2020). Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re) generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759134

- Bardi, U. (2017). Doughnut economics: A step forward, but not far enough. Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-06-30/doughnut-economics-a-step-forward- but-not-farenough/.

- Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Nygaard, C. A. (2022). Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tourism Geographies, 25(4), 1026–1046. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2022.2044376

- Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., Lee, E., Cheer, J. M., & Peters, A. (2023). Transformative epistemologies for regenerative tourism: Towards a decolonial paradigm in science and practice? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2023.2208310

- Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2008). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (Eds.) (2000). Tourism collaboration and partnerships: Politics, practice and sustainability. Multilingual Matters.

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

- Brouder, P. (2020). Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1760928

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Cash-Gibson, L., Isart, F. M., Martínez-Herrera, E., Herrera, J. M., & Benach, J. (2023). Towards a systemic understanding of sustainable wellbeing for all in cities: A conceptual framework. Cities, 133, 104143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104143

- Cave, J., & Dredge, D. (2020). Regenerative tourism needs diverse economic practices. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1768434

- Cocola-Gant, A. C. (2016). Holiday rentals: The new gentrification battlefront. Sociological Research Online, 21(3), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4071

- Coenen, L., Benneworth, P., & Truffer, B. (2012). Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Research Policy, 41(6), 968–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014

- DEAL - Doughnut Economics Action Lab. (2022). Guidelines and licensing Rules. Retrieved from: https://doughnuteconomics.org/license, at 28-06-2022.

- Dredge, D. (2021). Regenerative tourism. https://www.islanderway.co/post/regenerative- tourism

- Dredge, D. (2023). Diverse economies, doughnut economics and tourism. Course Introduction to Regenerative Tourism. The Tourism CoLab.

- Dredge, D. (2022). Regenerative tourism: Transforming mindsets, systems and practices. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2022-0015

- Elmualim, A., Shockley, D., Valle, R., Ludlow, G., & Shah, S. (2010). Barriers and commitment of facilities management profession to the sustainability agenda. Building and Environment, 45(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.05.002

- Ferretto, A., Matthews, R., Brooker, R., & Smith, P. (2022). Planetary Boundaries and the Doughnut frameworks: A review of their local operability. Anthropocene, 39, 100347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2022.100347

- Fletcher, R. (2011). Sustaining tourism, sustaining capitalism? The tourism industry’s role in global capitalist expansion. Tourism Geographies, 13(3), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.570372

- Fletcher, R., Murray, I., Blanco, A., & Blázquez, M. (2019). Tourism and degrowth: An emerging agenda for research and praxis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1745–1763. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1679822

- Geels, F. W. (2011). The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.002

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2015). Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900– 2050. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(5), 639–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1008500

- Graci, S. (2013). Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. Tourism Geographies, 15(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.675513

- Gravari-Barbas, M., & Guinand, S. (2017). Tourism and gentrification in contemporary metropolises: International perspectives. Taylor & Francis.

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2010). Transitions to sustainable development: New directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge.

- Hall, C. M. (2009). Degrowing tourism: Decroissance, sustainable consumption and steady- state tourism. Anatolia, 20(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2009.10518894

- Hartman, S. (2022). Success definitions of tourism impacts: Evolving perspectives and implications for destination governance. In: Stoffelen, A. & Ioannides, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Tourism Impacts: Social and Environmental Considerations. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hartman, S., & Heslinga, J. H. (2022). The Doughnut Destination: Applying Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economy perspective to rethink tourism destination management. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(2), 279–284.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2010a). The elusiveness of sustainability in tourism: The culture ideology of consumerism and its implications. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(2), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2009.31

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2010b). Justifying tourism: Justice through tourism. In S. Cole & N. Morgan (Eds.), Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects., (pp. 194–211). CABI.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2018). Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tourism Management Perspectives, 25, 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Carnicelli, S., Krolikowski, C., Wijesinghe, G., & Boluk, K. (2019). Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1926–1944. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1601732

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020a). The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1803334

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020b). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Hutchison, B., Movono, A., & Scheyvens, R. (2021). Resetting tourism post-COVID-19: Why Indigenous Peoples must be central to the conversation. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1905343

- Ioannides, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1763445

- Jover, J., & Díaz-Parra, I. (2020). Who is the city for? Overtourism, lifestyle migration and social sustainability. Tourism Geographies, 24(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1713878

- Kallis, G. (2011). In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics, 70(5), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.12.007

- Koens, K., Postma, A., & Papp, B. (2018). Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 10(12), 4384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124384

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., Boons, F., Fünfschilling, L., Hess, D., Holtz, G., Hyysalo, S., Jenkins, K., Kivimaa, P., Martiskainen, M., McMeekin, A., Mühlemeier, M. S., … Wells, P. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

- Latouche, S. (2004). Degrowth economics. Le Monde Diplomatique, 11.

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

- Mansilla, A. J., & Milano, C. (2018). Ciudad de vacaciones. Conflictos urbanos en espacios turísticos. Pol*len.

- Matunga, H., Matunga, H. P., & Urlich, S. (2020). From exploitative to regenerative tourism: Tino rangatiratanga and tourism in Aotearoa New Zealand. MAI Journal: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, 9(3), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.20507/MAIJournal.2020.9.3.10

- Milano, C., Cheer, J. M., & Novelli, M. (Eds.) (2019). Overtourism: Excesses, discontents and measures in travel and tourism. CABI.

- Milano, C., Novelli, M., & Cheer, J. M. (2019). Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(12), 1857–1875. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1650054

- Niewiadomski, P. (2020). COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757749

- Niewiadomski, P., & Brouder, P. (2022). Towards an evolutionary approach to sustainability transitions in tourism. In Booyens, I. & Brouder, P. (eds), Handbook of Innovation for Sustainable Tourism. Research Handbooks in Tourism series. Edward Elgar. Publishing. pp. 82–111.

- Ørngreen, R., & Levinsen, K. (2017). Workshops as a Research Methodology. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 15(1), 70–81.

- Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., … Postma, A. (2018). Overtourism: Impact and possible policy responses. Research for TRAN Committee,

- Pollock, A. (2019). Regenerative tourism: The natural maturation of sustainability.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Roy, A., & Pramanick, K. (2018). A comparative study of ‘safe and just operating space’for the south and south-east Asian countries. bioRxiv, 424200.

- Ruhanen, L., Weiler, B., Moyle, B. D., & McLennan, C. L. J. (2015). Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(4), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.978790

- Sheldon, P. J. (2021). The coming-of-age of tourism: Embracing new economic models. Journal of Tourism Futures, 8(2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-03-2021-0057

- Stewart, R., Bey, N., & Boks, C. (2016). Exploration of the barriers to implementing different types of sustainability approaches. Procedia CIRP, 48, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.04.063

- Stompff, G. (2018). Design thinking: Radicaal veranderen in kleine stappen. Boom.

- Torkington, K., Stanford, D., & Guiver, J. (2020). Discourse (s) of growth and sustainability in national tourism policy documents. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 1041–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1720695

- Virág, D., Wiedenhofer, D., Baumgart, A., Matej, S., Krausmann, F., Min, J., Rao, N. D., & Haberl, H. (2022). How much infrastructure is required to support decent mobility for all? An exploratory assessment. Ecological Economics, 200, 107511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107511

- Wittmayer, J. M., & Schäpke, N. (2014). Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustainability Science, 9(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0258-4