Abstract

This paper focuses on the settler colonial landscapes of tourism in the regional city of Dubbo, Australia. Dubbo is situated on Wiradyuri Country in the Orana region of New South Wales. Focusing specifically on the heritage-listed Old Dubbo Gaol and the Dundullimal Homestead, a former pastoral station, I explicate how these tourist sites offer experiences that normalise settler dwelling and occupation of First Nations Country. The Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal occupy a broader settler colonial landscape where Dubbo is presented historically as ‘empty’ until settlers exploited the town’s ‘natural’ resources. By occluding the relationship between invasion, pastoralism, and Indigenous dispossession, the sites reproduce for visitors settler colonial metanarratives of dwelling. Using Tim Ingold’s notion of taskscape, I show how the tourist sites create taskscapes which invite visitors and consumers to engage in settler forms of dwelling that normalise a settler colonial landscape. Tourist taskscapes consist of the activities and interactions in a heritage site that encourage visitors to take an active role in experiencing place and history. By aligning these experiences and activities to settler narratives and histories, the sites interpellate visitors into the processes of autochthony that were/are used to negate First Nations sovereignties. While these taskscapes are leaky and contain the presence of First Nations in select parts of the heritage sites, the taskscapes dominate heritage tourism and normalise settler colonisation as a feature of place-making that does not require explicit explanation or education.

Introduction

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following essay contains the names of people who have died.

This paper focuses on the settler colonial landscapes of tourism in the regional city of Dubbo, Australia. Dubbo is situated on Wiradyuri Country in the Orana region of New South Wales. Focusing specifically on the heritage-listed Old Dubbo Gaol and the Dundullimal Homestead, a former pastoral station, I explicate how these tourist sites offer experiences that normalise settler dwelling and occupation of First Nations Country. The Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal occupy a broader settler colonial landscape where Dubbo is presented historically as ‘empty’ until settlers exploited the town’s ‘natural’ resources. By occluding the relationship between invasion, pastoralism, and Indigenous dispossession, the sites reproduce for visitors settler colonial metanarratives of dwelling.

Using Tim Ingold’s notion of taskscape (1993), I show how the tourist sites of Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal create taskscapes which invite visitors and consumers to engage in settler forms of dwelling that normalise a settler colonial landscape. Tourist taskscapes consist of the activities and interactions in a heritage site that encourage visitors to take an active role in experiencing place and history. By aligning these experiences and activities to settler narratives and histories, the sites interpellate visitors into the processes of autochthony that were/are used to negate First Nations sovereignties. While these taskscapes are leaky and contain the presence of First Nations in select parts of the heritage sites, they dominate heritage tourism and normalise settler colonisation as a feature of place-making that does not require explicit explanation or education. The Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal Homestead sites both focus on a component of settler autochthony—carcerality and pastoralism—that differently contributes to the metanarrative of industry and place-making worthy of a heritage record. They are also the oldest heritage sites in Dubbo. Explicating the taskscapes involved in the experiential engagement with heritage sites discloses how settler forms of autochthony are commodified and reproduced into the present.

I locate myself as a participant in the town’s metanarratives and processes of settler autochthony. I was born in Dubbo and have resided here for most of my life. My family are Irish, Scottish, and English convict descendants who settled in Dubbo, Cowra, and Coolah in central New South Wales. My mobility in being able to move through rural towns and have a sense of belonging and place, and to see the settler and English names of my father and brothers on street names, reinforced some safety for me, despite our lower socio-economic status. These spatial scripts reflect how the social and built landscapes of settler colonisation function to make white Anglo-Celtic settler descendants such as myself feel at home. In the context of tourist geographies, the personal and local stories of settlers (such as myself) form part of a collective metanarrative of settlement and settler happenings worthy of remembrance and commodification.

In the first part of the paper, I explain how tourist geographies connect the taskscapes of settler dwelling and overwriting of First Nations Country to the present. I then analyse the taskscapes of the Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal and their role in reproducing metanarratives about Dubbo’s settler colonial history. I conclude by considering how Country, and the settler disordering of Country (Kearney, Citation2020), continues to inform tourist experiences and narratives of place in the region.

Positioning settler colonial tourism

For Tracey Banivanua Mar, heritage and tourist sites in Australia are spaces ‘produced by settler-colonial happenings’ (2012, p. 177) which ratify Indigenous ‘dispossession in spatial ways, constantly affirming metanarratives of terra nullius’ (p. 177). In my previous work I have argued that tourism in settler colonial spaces is productive of an apparatus of forgetting (Randell-Moon, Citation2020)Footnote1 where place and tourist branding works to discursively and institutionally forget the violent and racist settler colonial history foundational to these spaces. Tourist sites in settler colonial spaces are underlined by what Pierre Walter describes as ‘unacknowledged settler colonial histories and geographies of violence’ (2023, p. 246). Because tourism promotes particular understandings of ‘history in place’ (Banivanua Mar, Citation2012, p. 182), it ‘is an especially potent social force through which … settler stories can be perpetuated and resisted’ (Grimwood et al., Citation2019, p. 233). Phoebe Everingham, Andrew Peters, and Freya Higgins-Desbiolles (Everingham et al., Citation2021) note that Indigenous-led tourism can create conflict with settler expectations of access to heritage and sacred sites. As a result, ‘[u]nlearning coloniality is key for promoting transformative tourism’ (Everingham et al., Citation2021, p. 1).

Indigenous epistemologies of Country recognise the land as having agency. This reveals important insights about tourist experiences (Bawaka et al., Citation2017). The land and environment play a critical role in outback and regional tourism in Australia. This is partly due to the settlement patterns of colonisation in the capital and metropolitan areas of Australia (typically very close to the coast) rendering inland tourism enticing. In their study of New South Wales’ destination tourism branding, Beverley Seiver and Amie Matthews (Seiver & Matthews, Citation2016) found that the presence or absence of Aboriginal cultures varies in relation to the planning input of Aboriginal peoples. In the two case studies examined in this paper, the Old Dubbo Gaol and the Dundullimal Homestead, First Nations participation in their marketing and branding appears to be non-existent. The Old Dubbo Gaol has featured in a study of dark tourism (Wise & Mclean, Citation2020) but the authors do not connect the repackaging of violence through this form of tourism to settler colonial practices and narratives. While Dundullimal does not appear in the literature, Nicholas Gill and Alistair Paterson (Gill & Paterson, Citation2007) highlight the complexities of acknowledging First Nations contributions to the pastoral industry in related heritage sites.

I read the Old Dubbo Gaol and Dundullimal Homestead as landscape texts of settler colonisation, materialising metanarratives of Dubbo’s and the region’s history for visitors through the activities used to facilitate engagement with the sites. I draw on ethnographic field notes and experiences from visiting the case sites in October 2022 as well as promotional material. I have visited the sites many times previously as a resident and resident-tourist of Dubbo. The discursive function of landscapes, texts, and activities distributed and displayed at the sites inform the analysis. I also contextualise the branding, presentation, and stories from the case sites within local histories of Dubbo and the metanarratives of the pastoral industry. While Wiradyuri and First Nations feature in some parts of these stories, their contribution to the land through careful custodianship and labour in building the town is almost entirely erased and displaced.

I use Tim Ingold’s (Citation1993) concept of taskscapes as a methodology to identify settler colonial metanarratives in the knowledge activities and interaction with Dubbo’s history undertaken by visitors at the sites. Although Ingold (Citation2022, p. xviii) has revised this concept, I find his original formulation of taskscape helpful in my critical point of departure, as taskscapes disclose those activities involved in the active maintenance and naturalisation of settler metanarratives and their role in Indigenous dispossession (Randell-Moon & Randell, Citation2020). For Ingold, a ‘dwelling perspective’ is materialised through ‘the landscape [which] is constituted as an enduring record of—and testimony to—the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it, and in so doing, have left there something of themselves’ (1993, p. 152). The heritage sites examined in this article reproduce settler forms of dwelling and activities that normalise settler autochthony (see also Chen, Citation2023). The record of dwelling narrated in these sites is that until settler industry and the instigation of pastoral tasks created activities, society, and law, a place did not exist previous to these taskscapes.

Because Ingold’s approach to the environment and dwelling emphasises experiential relationships to place, it has critical purchase for understanding the affective dimensions of place-making and site-specific (rather than mass) tourism. For instance, Ingold’s ideas have been applied to nature-based tourism in Iceland (Lund, Citation2013), Mallorca (Andrews, Citation2017), and canoeing in northern Canada (Mullins, Citation2009). Relatedly, David Crouch (Citation2010) discusses heritage as processually emergent and performative, related to ‘the flows of influence inherent in its continual making’ (p. 57). Fostering these kinds of site-specific experiences is strongly connected to the local qualities of place. Karine Dupre notes ‘the importance of participation in place-making to preserve local identities’ (Dupre, Citation2018, p. 116). Similarly, Alan A. Lew identifies the importance of ‘organic’ place making that is ‘not intentionally tourist oriented’ but is nevertheless ‘fundamental to the tourist attractiveness of a place’ (2017, p. 450). These connections to place are theorised as seemingly organic expressions and outcomes of inhabiting place. As tebrakunna country et al. point out however, ‘Any community may identify with a place or leverage its attributes; but the time scale of Indigenous communities’ place knowledge and place attachment is of a completely different order’ (Lee & Eversole, Citation2019, p. 1511). Because the activities and stories involved in settler dwelling are re-presented as organic manifestations of place experiences, care must be taken to avoid acritical notions of ‘organic’ and ‘indigenous place-making’ (Lew, Citation2017). Highlighting the settler colonial dimensions to such activities discloses how the erasure of Indigenous dispossession is normalised in tourist taskscapes.

Whereas Ingold theorises a form of dwelling that largely engenders positive connections to and constructions of place, Amanda Kearney discusses dwelling in an Australian context as involving competing forms of ontics as a result of the failure by non-Indigenous peoples to recognise Indigenous sovereignties. For Kearney (Citation2020), settler colonisation ‘is a destructive ontology’ (p. 189) that ‘translates to a denial of the integrity and empiricism of Indigenous land and seascapes as made up of ancestral beings’ (p. 190). Read through Kearney, settler colonial taskscapes are an active disordering of Country and its constituent cohabitants (p. 191). Tourist heritage sites provide historical information on settler dwelling and serve to reaffirm settler colonial metanarratives of the Dubbo region as ‘empty’ and ‘unproductive’ until pastoral activities took place. Rendering this history into a tourist taskscape commodifies and extends settler ontics into the present.

Discovering Dubbo’s tourism geographies

Dubbo is located on Wiradyuri Country roughly in the centre of New South Wales and is part of the Central West and Orana regions. The Wiradyuri Nation is one of the largest land territories of First Nations people in New South Wales. Other Nations from the Central West and Orana regions include Wangaibon Country, in the Ngiyampaa Nation, and the region is also home to Gamilaraay and Wayilwan peoples. Dubbo is the largest city in this region with a population of approximately 40,000 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2020a). Dubbo was initially established as a village in 1850 and was classified as a town in 1872 and then finally a city in 1966 (McBurney, Citation1993, p. 16). First Nations make up fifteen per cent of the population of Dubbo and constitute a relatively high proportion of the population in the surrounding towns, with up to a third of the population in Wellington being First Nations (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2020b). The Tubba-Gah Wiradyuri peoples and Elders are the local custodians of Dubbo. Non-Indigenous peoples have mistranslated Wiradyuri as ‘Wiradjuri’ and the latter is often used in official tourist and government documents. I follow Wiradyuri language expert Uncle Stan Grant’s spelling.Footnote2

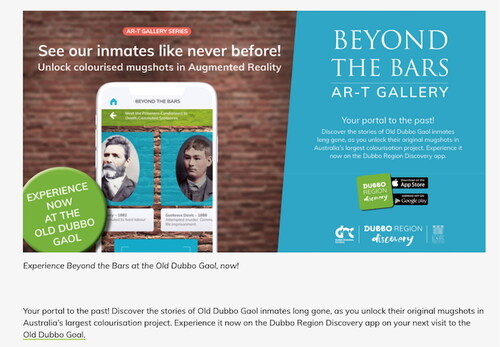

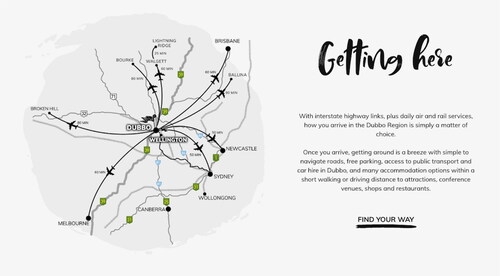

The Dubbo Regional Council manages tourism branding through the Dubbo Region Discovery App (Dubbo Regional Council, Citation2022) () and the Dubbo Region website (Dubbo Regional Council, Citation2023).

The Council has recently launched The Destination Dubbo—International Ready project which aims to make Dubbo ‘the number one inland visitor destination in NSW and Australia, both for Australian families and international visitors to NSW’ (Dubbo Regional Council, Citationn.d.). Regarding the Old Dubbo Gaol and the Dundullimal Homestead, the former has a more extensive brand and interactive consumer engagement owing in part to its location in the centre of the town and length of its operation as a tourist site. The Discovery App includes a gamified tourist experience where ‘Two inmates have escaped the Old Dubbo Gaol and hidden the Dubbo Region’s treasures throughout the CBD [central business district]’ (Dubbo Regional Council, Citation2022). In the new Destination Dubbo project, the Gaol will be the centre of the Public Heritage Plaza. While Wiradyuri heritage forms part of the new plan, for instance in the proposed Dubbo Wiradjuri Tourism Centre, Wiradyuri heritage and more broadly First Nations presence is marginal in the current branding.

The Old Dubbo Gaol

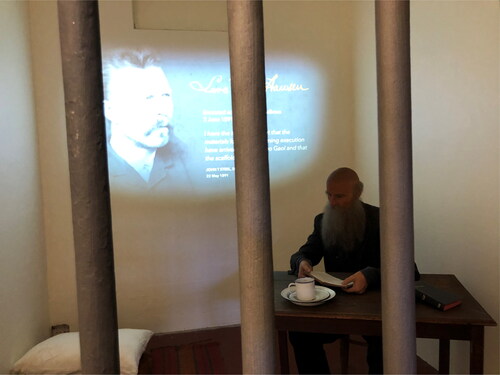

The Old Dubbo Gaol is managed by the Dubbo Regional Council and facilitates an interactive visitor experience and taskscape involving costumed demonstrations, video and multi-media, props and puzzles, gamified activities, and at one time, life-size (and terrifying to a child!) animatronic puppets of the gaolers and prisoners ().

The Old Dubbo Gaol has won a number of heritage awards throughout its operation as a tourist destination (Hornadge, Citation1978). It was the 2022 Winner of National Trust Heritage Awards: Education and Interpretation and is one of the most visited sites in Dubbo (Dubbo Regional Council, Citation2021). The National Trust is a heritage conservation organisation that plays an instrumental role in preserving what counts as history and heritage in Australia. The Old Dubbo Gaol ceased official operations in 1966 and was restored as a tourist attraction by the Gaol Restoration Committee of the Dubbo Museum and Historical Society with the support of the Dubbo Chamber of Commerce and the Dubbo City Council and opened to the public in 1974 (Hornadge, Citation1978).

The origins of Gaol are intimately connected to the development of the township of Dubbo. It was one of the first buildings established in 1847 along with a rudimentary Court and Police Station (Hornadge, Citation1982, p. 60). The town grew around this carceral infrastructure (p. 19) starting from Macquarie Street—the ‘main’ street. Country influenced the location of the gaol, and hence the town, on the eastern side of the Macquarie River or Wambuul, which has the higher bank. The street names and layout of central Dubbo are virtually the same since their foundation in the 1800s. Ironically, the decision to locate these carceral sites in Dubbo rather than nearby Wellington was due to the latter’s prosperity and desirability as a residential settlement. Wellington is now in population and business decline and was deemed suitable for a new jail serving the Orana region, the Wellington Correctional Centre. The locations of the jail and development of the town were chosen by those who took advantage of squatting, such as Robert Dulhunty and John Maughan (later owner of Dundullimal) (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 34). Squatting on unceded Wiradyuri lands was permitted as part of what Patrick Wolfe describes as the practice of allowing settlement and settler expansion so that (later) Crown possession of occupied land could occur (2006, p. 391). As a result, squatters were able to legitimise their presence and have significant involvement in settler place-making. Dubbo was named after Dulhunty’s squatter’s run (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 31).

The restoration and re-presentation of the Gaol as a heritage site focuses on the latter part of the nineteenth century, despite the Gaol operating as a remand centre for much of its operations in the twentieth century (Hornadge, Citation1982, p. 62). This temporal period is reinforced in the case studies of the prisoners presented in the cells and elsewhere on the site, the props displayed, the costumes worn by the demonstrators, and the choice to restore the gallows to the site (which was removed in sometime in the early nineteen-hundreds) (p. 63). The Gaol exists in a relatively closed off space in the centre of the city, though the prison walls are not high enough to block out views of some of the surrounding taller commercial buildings. Visitors are provided with a map of the site with descriptions of each building. The site contains a number of different prison cells, guard buildings, enclosed exercise yards, and kitchen and storage buildings. Some of the smaller buildings have been converted to modern toilets. The suggested route on the map begins with the male cellblock, moving through the female cellblock, the gallows gallery, exercise yards, and kitchen and hospital ward and the entrances and exits of these buildings generally align with the map. Within the male cellblock, there are two Dark Cells that were dedicated to solitary confinement. These cells enable visitors to viscerally experience confinement and recall the purpose of the site’s carceral taskscapes.

Whereas the site encourages an active taskscape, the portable cell (not numbered in the map and located near the outer wall) contains a static display of information. A display called ‘A Stretch in Time …’ depicts a dual timeline of carceral practices in Australia and Dubbo. The starting point is the 1788 establishment of Australia as a penal colony mirrored by Dubbo’s foundational moment in the 1846 first Courts of Petty Sessions. The timelines taper off towards the 1960s when the Dubbo Gaol closed and then there are a few items about the opening of the Gaol, and Wellington as the site for a new operating prison. Invasion, settler violence, and criminalisation of First Nations (or reference to First Nations at all) are not included in the timeline. In other words, ‘the geography of violence underlying the site, is … absent’ (Walter, Citation2023, p. 260).

The taskscapes related to First Nations profile them as criminals similarly to the non-Indigenous subjects, rendering crime an individualised act. Jack Underwood (Charlie Brown) and Albert, two of the eight prisoners executed in the Gaol, are represented in the Gallows Gallery, situated at the back of the site. Albert’s grave is marked in the prison grounds alongside two other identified prisoners in a mass grave (numbered on the map); the mass grave was located at a later time near the wall outside the male cellblock. Paddy, described as a police tracker, is also featured in the Gallows Gallery and was executed elsewhere. Police trackers were assistants to the police in forensic environmental investigation, often under coercive colonial conditions. As discussed below in relation to the pastoral industry, First Nations contributions to forensic policing are generally disregarded in historical and contemporary policing professional practices. One of the cells in the men’s block provides a case story on Billy Bogan. In the Remand Cells, positioned between the male cellblock and the Gallery (and numbered after these two sites on the map) there is a case study of Arthur Waters, a 15-year-old imprisoned for horse theft, who was discharged under the First Offenders Probation Act of 1894 (NSW) (which allowed discharge if no previous crimes had been recorded). The exhibit states that after release, Waters worked at the St. Clair Aboriginal Mission (near Mount Olive) with his mother for the rest of his life. Neither this Mission, or the two missions in the area near Dubbo (Dandaloo Aboriginal Reserve) and Wellington (Namina Aboriginal Reserve, still operating), are contextualised or mentioned further. The lack of information on missions and reserves in the site disassociates them from carceral practices.

Christina Goulding et al. discuss the ‘commercial staging of history’ as involving mutually constitutive forms of presence and absence, which ‘has consequences for how the past is experienced and understood’ (Goulding et al., 2018, p. 25). First Nations presence in the Gaol site constitutes ‘absence management’ (p. 26) in the lack of historical information provided about missions and reserves as well as Wiradyuri law and customs. This absence of information contrasts with other areas of the prison where there is a contextualised case study of mental health and poverty in the story of Albert Moss, ‘the homicidal hobo’, in the kitchen building; this is the last stop on the map before the Museum Shop.

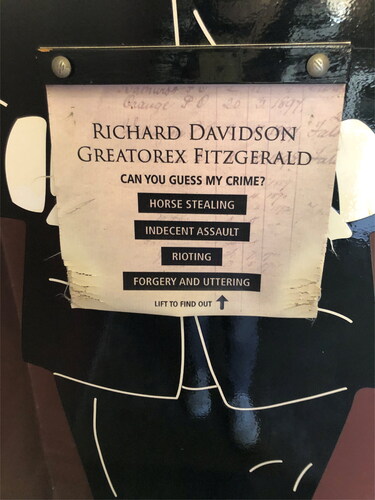

Continuing with Goulding et al., they argue that interactive heritage sites are ‘a triumph of the tactile and multi-sensorial, over the optical or contemplative experience’ whereby ‘the public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one’ (2018, p. 27). The exhibits, demonstrations, puzzles, and activities at the Gaol likewise prioritise interactivity. Visitors can experience both prisoner and gaoler roles. I have already mentioned the Dark Cells at the very beginning of the site. During the escape demonstration, we were positioned on the roll call lines outside of the male cellblock to pantomime gaol routines. To play at being a gaoler, visitors can climb the stairs to a reconstructed Watch Tower. This is numbered sequentially after the gravesite. In the Tower, a recording advises visitors how to surveil the site. After exiting the Gallow’s Gallery, visitors are then led directly into the Charge and Lodge Rooms where they can complete intake, reporting misconduct, and other forms (with pencils provided). Case studies presented in the Hospital Ward and Gaol Store (the last set of buildings on the map) consist of life-size wooden cut-outs of either female or male figures with a case file and flap of plastic that incites visitors to ‘guess’ which crime the figure has committed. During my visit, I observed both parents and children shouting their guesses—such as ‘vagrancy’ and ‘indecent assault’—in a rather confusing educative space ().

Prioritising interactivity results in visitors ostensibly experiencing carceral practices as a pleasurable form of consumption, akin to ‘dark tourism’ (Wise & McLean, Citation2020). The Gallows Gallery features prison torture instruments such as a whipping table, tawse, cat o’nine tails, iron mouth gags, truncheons, and heavy leg, hand, and neck chains. The gamification of the Gaol and the costumed demonstrations of fictionalised escapes where audience members’ names are sought and then interspersed into the stories also involve the repackaging of unpleasant and violent experiences as fun and playful. The Gaol offers After Dark Tours to capitalise on this form of consumption. Jenny Wise and Lesley McLean suggest this repackaging of violence as fun serves an educative purpose in distancing visitors from ‘the past’. In other words, such activities illustrate how ‘we as a society, have moved away from death and torture within the prison setting’ (2020, p. 566). Thus while the interactive taskscapes in heritage prison sites are immersive, they ultimately function to separate visitors from the ‘darker side of Australia’s carceral history’ (p. 571).

I would like to push Wise and McLean’s insights further to connect this history with Indigenous dispossession. Specifically, I have argued previously that despite dark tourism’s appeal being the ostensible engagement with distasteful aspects of a place’s history, this engagement is nevertheless managed within a safe tourist experience that can be terminated whenever the customer desires (Randell-Moon, Citation2020). This choice to opt out of history thereby returns the tourist to the security of the present. The ontics of security in a settler colonial landscape are supported by a metanarrative of progress entailing an understanding of violence or anachronistic attitudes as past events. Crucially, these past events are also disconnected from Indigenous dispossession as a historical and ongoing practice. The taskscapes of the Gaol exemplify absence management whereby the activities of the site are disassociated from knowledge of settler invasion, violence, and dispossession. Even though it is settler colonisation that is responsible for the laws and carceral practices of the Gaol, settler occupation is normalised—it does not require explanation or contextualisation in the exhibits as part of Dubbo’s heritage. This obfuscation of occupation’s structural connection to Indigenous dispossession (Wolfe, Citation2006) is also evident in the next case site examined.

The Dundullimal Homestead

Dundullimal is a heritage-listed site managed by the National Trust and located on the outskirts of Dubbo. The Trust describes the site as ‘Dubbo’s oldest building open to the public’ (National Trust, Citation2023) and it is dated to the middle of the nineteenth-century. It has some branding co-location with Taronga Western Plains Zoo located nearby (and portions of the property are owned by the zoo to run cattle [McBurney, Citation1993, p. 34]). The site can be used for functions and it has hosted the annual ‘Under Western Skies’ music festival, signalling the capacity of the site to be multi-sold. The site is multi-functional for taskscape gain. As with the Gaol and broader alliterative city-branding, visitors are encouraged to ‘Discover Dundullimal’ (National Trust, Citation2023) and its restored homestead, stable, and workshop, along with other buildings and artefacts that once operated in a working pastoral station. The site was first used in 1836 by Charles and Dalmahoy Campbell, squatters who operated agricultural enterprises beyond the limit of settlement. The current property was donated by descendants of the Baird family to the National Trust in 1985. With help from the NSW Bicentennial Council and the Macquarie Regional Committee of the Trust (Dargin, Citation1999, p. 4), the site was ready for presentation to the public in the year of the bicentennial, 1988 (which celebrated two hundred years of settler occupation in Australia). The Old Dubbo Gaol was also provided with a Bicentennial Grant for upgrades (Hornadge, Citation1989, p. 3). The impetus for the heritage listing of the site is due to the architectural significance of the homestead, which is ‘the most sophisticated slab building known in Australia’ (Dargin, Citation1999, p. 2).

The site contains a more passive set of taskscapes than the Gaol, possibly as a result of having less resources and its location outside of town. The exhibits are largely static and plaques are deployed to guide visitors’ interpretations. As with the Gaol, visitors are given a numbered map to orient their engagement with the site. There are four main buildings, the Homestead, stables, Timbrebongie Church (which has been moved from its original site), and a shed (which has been converted to a gift shop and tea room). The homestead is surrounded by a large working farm and operates at reduced hours. Because it is only accessible by car, the other visitors with me on a guided tour were from Sydney on a mini-holiday drive. Due to its location, the site is more integrated with the surrounding landscape and non-human visitors were more prominent. I counted and heard at least six different bird species engaging the site. The bird population was fostered by some extensive cat-trapping, according to the lady in the teashop. A National Trust advertising pamphlet enjoins visitors to ‘Immerse yourself in Dubbo’s history at this peaceful property’ (National Trust, n.d.). The tranquillity of the space is emphasised in the no. 5 exhibit of the map featuring a replication of a 1852 landscape painting by Kennedy Macintosh Baird, a friend of the Maughan family ().

This peacefulness is inextricably connected to settler occupation and framing of the landscape as ‘empty’ and requiring industry. Multi-use of the site as an events space is also premised on its secluded atmosphere.

As mentioned earlier, the dominant metanarrative of Dubbo’s history is the establishment of pastoral runs such as Dundullimal. These runs then enabled Dubbo to be positioned at a crossroads for travelling stock between Melbourne, Sydney, and Queensland (Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 16). Dubbo as the geographical meeting point for commerce, trade, and tourism, the ‘Hub of the West’ (Hornadge, Citation1982, p. 23) still features in branding of the town ().

As with the Old Dubbo Gaol, Dundullimal exemplifies how settler colonisation is itself disconnected from the carceral and criminalising practices of dispossession such as squatting, which is re-presented as necessary for the development of region. A plaque titled ‘Prosperity to the Bush through Machines’ states ‘Australia had seemingly unlimited land compared to England and the colonial government supported increased occupant and settlement activities’. This plaque connects the site’s taskscapes to English rather than First Nations antecedence.

Local historians narrate that Dubbo was ‘discovered’ by John Oxley, Surveyor General in 1818 (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 35; Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 3). When the prison was established, it and a few other buildings were described as ‘the only signs of civilisation to be found on the Macquarie Bank’ (Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 19) where ‘law was almost unknown’ (p. 21). Wiradyuri and neighbouring Nations, and their laws, are completely evacuated from this landscape even as their custodianship of land made it easy for settlers to occupy and establish runs. For instance, Oxley described the land as having ‘a pleasant, park-like appearance’ with ‘excellent soil and fit for all purposes of cultivation’ (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 35). Banivanua Mar argues that non-Indigenous infrastructure converts the landscape into a settler colonial narrative (2012, p. 191). Prior to the occupation of Dubbo, ‘The aborigine roamed about’ (Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 44; see also Dormer, Citation1987, p. 38) and this ‘Transitory nature is replaced with industrial permanence’ (Banivanua Mar, Citation2012, p. 193) by ‘people who played well their part in settling this outpost of a far flung Empire’ (Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 68). The taskscapes of Dubbo’s early settlers are preserved in the tourist exhibits of Dundullimal to exemplify and commodify the developmental trajectory of agriculture and infrastructure for not only Dubbo, but also the region, state, and nation.

A pamphlet at the site provides a timeline of the homestead, beginning in ‘Pre 1830s’ by acknowledging that ‘The property stands on the traditional lands of the people of the Wiradjuri Nation’ and ‘Archaeological evidence’ has revealed ‘areas of Aboriginal significance including a camp site, bora ground, scar trees and a burial site’. The remainder of the timeline is exclusively non-Indigenous, mentioning the run’s owners and individuals such as Walter William Brocklehurst, who has a village near Dubbo named after him. Where First Nations are rendered homogenous and undistinguished, settler happenings and history are individualised and connected to place-making (Banivanua Mar, Citation2012, p. 181).

Where Aboriginal toponymy features in the site, it is appropriated for settler autochthony. The pamphlet explains, ‘Dundullimal is a Wiradjuri word meaning ‘thunderstorm’ or ‘hailstorm’ and is the name of the local Aboriginal group.’ There is no citation for this explanation but it is repeated in several non-Indigenous history sources (McBurney, Citation1993, p. 9; Dargin, Citation1999, p. 6). Yvonne McBurney states the site was originally the land of Bulga and Wiradthuri ‘tribes’ (1993, p. 41). In Marion Dormer, ‘The Macquarie Aborigines belonged to the Wiradjurie tribe (pronounced Werathery) a subtribe of the Kawambarai’ with the main groups being ‘Dundullimal and Bumblegumbium’ (1987, p. 36). The possessive use of ‘Macquarie’ here refers to the naming of the main river in Dubbo after a colonial governor. The vagueness of this toponymy illustrates what Kearney describes as the ‘ambivalence or ‘failure to care’ for Indigenous sovereignties and custodianship (2020, p. 189). Such vagueness could easily be resolved by simply consulting Wiradyuri Elders and descendants.

The naming of Dubbo also reflects this ambivalence in the ambiguous Indigenous meanings attributed to it. As recited in local histories: ‘What does the name ‘Dubbo’ mean? There are several explanations. One is that it was the name of an old aboriginal whom Dulhunty found when he took up the station. The second is that Dulhunty wore a helmet and that the native name for a head piece was ‘Thubbo’ or ‘Dubbo’. Still another story is that the word Dubbo means ‘white clay’ (Jarvis, Citation1949, p. 92) or red earth (Dargin, Citation1999, p. 7; Hornadge, Citation1982, p. 11). Aboriginal toponymy suggests a disjuncture with the apparent fact of settler ownership, but the absence management of tourist sites such as Dundullimal works to present the settler landscape as otherwise unoccupied. For instance, in a story told by local historians: ‘It is thought that the last Aboriginal Corroboree was held at ‘Dundullimal’ on the eve of the first train’s arrival to Dubbo in 1881’ (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 100; McBurney, Citation1993, p. 31). This narrative combines both the dying race and industrial transformation myths of the region where First Nations vacate the land for non-Indigenous development.

Although not mentioned in any of the site exhibits, local historians note that Aboriginal peoples worked on the station (McBurney, Citation1993, p. 16) but unlike convicts and other labourers, they were not provided with accommodation. Because history is connected to the material presence of the buildings on the Dundullimal site, Aboriginal labour is therefore absent. Similarly broader regional and national histories of pastoralism neglect the First Nations labour that made this industry possible (Gill & Paterson, Citation2007) and it was common practice that First Nations were underpaid or not paid for their labour. The only material Aboriginal presence indicated by the tourist taskscapes in the site is a tree the tour guide identified as used for carving ‘boats’ (mentioned in the pamphlet) (). It is more likely that the trees were scarred by the removal of bark for canoes, not boats.

Tour guides also contribute to absence management based on their own knowledge of history and place. The guides during my visit appeared to be quite older, perhaps due to the roles being staffed by volunteers, and used terminology for First Nations that was anachronistic. As with the Gaol, there is space in the site for recognition and contextual information so the absence of better information on Aboriginal labour, occupation of the site, and toponymy is an active form of heritage and history management. As Banivanua Mar explains, such absences are not passive, ‘Australia did not forget its black history through absent-mindedness, but rather through an active process of repressing the full picture of the past’ (2012, p. 178). Aboriginal presence in the site is articulated through vague toponymy and select artefacts but without the historical work that could confirm, through Wiradyuri expertise of Elders in Dubbo, the language, occupation, and law of First Nations on the site of Dundullimal.

I have argued so far that the Old Dubbo Gaol and the Dundullimal Homestead are situated in a broader settler colonial landscape where Dubbo is presented historically as ‘empty’ until settlers exploited and developed the town’s ‘natural’ resources. The heritage sites constitute taskscapes of settler colonial metanarratives in the knowledge activities and interaction with Dubbo’s history undertaken by visitors. Articulating this metanarrative of settler colonisation as a taskscape draws attention to the active ways settler dwelling is normalised. Part of this normalisation of settler dwelling is the concomitant normalisation of the disordering of Wiradyuri Country through settler occupation and the pastoral industry. The violence of this disordering is obfuscated and the transformation of Wiradyuri Country presented as inevitable and necessary for progress and development.

Tourism geographies are part of this disordering and the continuation of settler colonial taskscapes (see e.g. Grimwood & Johnson, Citation2021; Walter, Citation2023). The renewed emphasis on tourism in the region and Dubbo occurs because a decades-long drought has severely impacted the regional pastoral economy and landscape (Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology, Citationn.d.). Dominant representations of Australian pastoral landscapes found in the Dubbo region, such as Dundullimal, feature yellow-white grass and wheat, and the exhibit mentioned earlier () folds this aesthetic into the taskscape of the pastoral industry. Such an aesthetic is illustrated in James Bentley’s visual book, The Golden West (Bentley, Citation1984), and late nineteenth century descriptions of Dubbo as ‘that gate of great pastures’ (Hornadge, Citation1982, p. 23). Eris Fleming’s painting, City on the Plains, displayed at the Dubbo Airport, is typical of non-Indigenous Australian landscape art where the golden hues and lighting emphasise agricultural production. While the painting implies agricultural fecundity, ‘The scene reflects how soon settlers upset Australia’s grasses’ (Gammage, Citation2011, p. 34). Paintings such as Fleming’s, as well as Arthur Streeton’s Near Heidelberg (1890) and Tom Robert’s A break away! (1981), have created a representational regime featuring creams and whites as the prototypical colour scheme of Australian landscapes. These artists are nationally significant in their promotion of what Australian landscapes look like. The colours included in these works reflect introduced grasses. Native summer grasses are tan or tan-purple. The latter flourish in summer compared to non-native grasses which are winter or spring perennials. The ‘golden creams are colours of death’ (Gammage, Citation2011, p. 34) and indicate that Wiradyuri Country is sick. The colours reveal the unacknowledged violence to flora and fauna bought about by settler colonisation (see also Walter, Citation2023).

The ‘peaceful’ site of Dundullimal and its use for social events and community festivals belies the violent disordering of Country occasioned by the pastoral industry and its securitisation through carceral practices, exemplified in the Gaol. As explained earlier, the metanarrative of the heritage sites reproduces myths of an ‘empty’ landscape and more troublingly, the ‘peaceful settlement of the Macquarie between Wellington and Warren’ (Dormer, Citation1987, p. 36). Despite having a profile in the Gaol’s Gallows Gallery, the execution of Jack Underwood in 1901 does not mention his participation in the 1900 Breelong massacre, along with Jimmy and Joe Governor, which took place near Gilgandra on a station owned by John Mawbey. This massacre is infamous for being one of the few recorded attacks on settlers by First Nations, rather than the reverse, and is the basis of book and film The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1972, 1978). Both the book and film are considered classics in Australian literature and cinema. While records of the attack and the enormous manhunt for Underwood and the Governors exist through news reporting and court archives, the motivations for the violence are often portrayed as unknown or fictionalised in the case of Thomas Keneally’s book. Most historians suggest the treatment of Jimmy Governor’s wife (who was white) by Mrs Mawbey was the instigation for the attack (Hornadge, Citation1978, p. 34; Moore & Williams, Citation2001). An early twentieth century poem with unidentified provenance illustrates the economy of violence that underpropped First Nations labour in the region: ‘But people who live on Black labour/And start cheating the Blacks,/May be sure they’ll wipe out the debt,/If they do it with gudgeon and axe’ (Hornadge, Citation1978, p. 39).

Within settler metanarratives, the massacre forms part of what Banivanua Mar identifies as ‘a distant, hazy, indeterminate violence’ (2012, p. 187) where the ‘lack of solidity empties’ memories of the event from ‘responsibility in the present’ (p. 189) to position colonial tourism geographies as benevolent. The disruption of Country through pastoral economies, the violence associated with pastoral labour, and the vague and confusing local histories regarding the origins of Aboriginal toponymy create ambivalence in historical accounts of First Nations in the Dubbo region that serves to displace an engagement with Indigenous occupation and dispossession.

Conclusion

Combining the insights of Banivanua Mar, Kearney, and Ingold, I have argued that contemporary tourist experiences in settler colonial places such as Dubbo are facilitated through taskscapes for visitors that normalise settler dwelling, settler colonial metanarratives and settler geographies. The conceptual and methodological approach deployed in the paper aims to ‘demonstrate how tourism is contributing to the settler colonial present’ (Grimwood, Muldoon & Stevens, Citation2019, p. 244). While the Old Dubbo Gaol has a more interactive series of carceral taskscapes than Dundullimal, which features static displays of pastoral taskscapes, both sites take for granted settler dwelling and metanarratives of development in ways that assume no pre-existing First Nations laws or custodianship. Indeed, both reify a tourism geography of coloniality to elide First Nations histories (see also Chen, Citation2023; Grimwood & Johnson, Citation2021; Walter, Citation2023). First Nations do have presence in these sites in some of the exhibits at the Gaol and through toponymy and the carved tree at Dundullimal. I suggest this presence constitutes a form of absence management that obscures the violent disordering of Country in the creation of a pastoral industry and its securitisation through non-Indigenous law. Such practices are fundamentally connected to Indigenous dispossession as well as missions and reserves, whose taskscapes are integral to the operation of settler colonisation but remain obscured in the heritage record of settler dwelling in Dubbo. More so, these taskscapes are resistant to multiple and lengthy First Nations histories that re-draw tourism geographies towards place-centric views of Country rather than colonial boundary, scope, and practice.

Without an understanding of Wiradyuri history and First Nations presence in the region, visitors’ understanding of place is refracted through the taskscapes of settler dwelling. Using taskscapes is a conceptual method for de-naturalising settler occupation through reflective ethnographic analysis of tourist heritage sites. This is because taskscapes draw attention to active experiences and practices that mimic settler autochthony. It is important to explicate dwelling and the taskscapes involved in constituting settler colonisation in order to critique how settler forms of autochthony are materialised in tourist experiences. Without this de-naturalisation, acritical notions of locality, organic communities, and ‘truly indigenous place-making’ (Lew, Citation2017, p. 461) used in tourism geography analyses can also normalise settler occupation. Within place-based tourism, active remembrance of settler colonisation and accurate information regarding First Nations should become a normalised part of the taskscapes involved in visiting and experiencing Dubbo and other places with settler colonial histories. This remembrance needs to be exercised by non-Indigenous peoples so that First Nations are not solely burdened with the transformation and decolonisation of tourist heritage sites.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Holly Eva Katherine Randell-Moon

Holly Eva Katherine Randell-Moon is a non-Indigenous Associate Professor in the School of Indigenous Australian Studies, Charles Sturt University, Dubbo, Australia. She has published on settler colonialism, cultural geography, and digital infrastructure in Media International Australia, Policy & Internet and Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture. Along with Ryan Tippet, she is the editor of Security, Race, Biopower: Essays on Technology and Corporeality (2016). She is the editor of the journal Somatechnics.

Notes

1 Via Michel Foucault (Citation1980).

2 I use the term First Nations to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the lands now known as Australia and Indigenous to refer to Indigenous peoples more generally. While the lands now known as Dubbo are home to the Wiradyuri peoples, other Nations have also resided in these lands and so First Nations is used to be inclusive of these Nations. I hope to balance the specificity of Wiradyuri with the broader negation of First Nations sovereignties foundational to carceral, pastoral, and tourist practices. Some sources refer specifically to Aboriginal peoples and this terminology is used for source fidelity.

References

- Andrews, H. (2017). Becoming through tourism: Imagination in practice. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finish Anthropological Society, 42(1), 31–44.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. (2020a, October 30). 2016 Census QuickStats – Dubbo. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SS- C11296?opendocument.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. (2020b, October 30). 2016 Census QuickStats – Wellington. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC14221.

- Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology. (n.d). Previous droughts. http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/drought/knowledge-centre/previous-droughts.shtml#2017_2019_drought.

- Banivanua Mar, T. (2012). Settler-colonial landscapes and narratives of possession. Arena Journal, 37/38, 176–198.

- Bawaka, C., Wright, S., Lloyd, K., Suchet-Pearson, S., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D., & Tofa, M. (2017). Meaningful tourist transformations with Country at Bawaka, North East Arnhem Land, northern Australia. Tourist Studies, 17(4), 443–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797616682134

- Bentley, J. (1984). The Golden West. Robert Brown & Associates.

- Chen, I. (2023). Confronting historical narratives at the Castillo de San Marcos, Saint Augustine, Florida. Tourism Geographies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2023.2278119

- Crouch, D. (2010). The perpetual performance and emergence of heritage. In E. Waterton & S. Watson (Eds.), Culture, heritage and representation: Perspective on visuality and the past (pp. 57–71). Ashgate.

- Dargin, P. (1999). Dundullimal: Held in trust. Development and Advisory Publications Australia.

- Dormer, M. (1987). Dubbo to the turn of the century: An illustrated history of Dubbo and districts – 1818–1900. Macquarie Publications.

- Dubbo Regional Council. (2021). Old Dubbo Gaol. https://www.olddubbogaol.com.au/.

- Dubbo Regional Council. (2022). Dubbo Region Discovery App. https://dubbo.com.au/discoveryapp.

- Dubbo Regional Council. (2023). The Dubbo Region. https://dubbo.com.au/

- Dubbo Regional Council. (n.d). Destination Dubbo. https://www.dubbo.nsw.gov.au/Our-Region-Environment/Major-Projects/destination-dubbo.

- Dupre, K. (2018). Trends and gaps in place-making in the context of urban development and tourism: 25 Years of literature review. Journal of Place Management and Development, 12(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-07-2017-0072

- Everingham, P., Peters, A., & Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2021). The (im)possibilities of doing tourism otherwise: The case of settler colonial Australia and the closure of the climb at Uluru. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103178

- Foucault, M. (1980). The confession of the flesh. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977. The Harvester Press.

- Gammage, B. (2011). The biggest estate on earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin.

- Gill, N., & Paterson, A. (2007). A work in progress: Aboriginal people and pastoral cultural heritage in Australia. In R. Jones & B. J. Shaw (Eds.), Geographies of Australian heritages: Loving a sunburnt country? (pp 113–132). Ashgate.

- Goulding, C., Saren, M., & Pressey, A. (2020). ‘Presence’ and ‘absence’ in themed heritage. Annals of Tourism Research, 71, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.05.001

- Grimwood, B. S. R., & Johnson, C. W. (2021). Collective memory work as an unsettling methodology in tourism. Tourism Geographies, 23(1–2), 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1619823

- Grimwood, B. S. R., Muldoon, M., & Stevens, Z. M. (2019). Indigenous cultures and settler stories within the tourism promotional landscape of Ontario, Canada. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 14(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2018.1527845

- Hornadge, B. (1978). Old Dubbo Gaol. Gaol Restoration Committee of the Dubbo Museum and Historical Society.

- Hornadge, B. (1982). Dubbo. Macquarie Publications.

- Hornadage, B. (1989). Old Dubbo Gaol. Gaol Restoration Committee of the Dubbo Museum and Historical Society.

- Ingold, T. (1993, October) The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeology, 25(2), 152–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

- Ingold, T. (2022). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Jarvis, J. (1949). History of Dubbo: 1818 to 1949. Dubbo Municipal Council.

- Kearney, A. (2020). Order and disorder: Indigenous Australian cultural heritages and the case of settler-colonial ambivalence. In V. Apaydin (Ed.), Critical perspectives on cultural memory and heritage (pp. 189–208). UCL Press.

- Lee, E., & Eversole, R, Tebrakunna Country. (2019). Rethinking the regions: Indigenous peoples and regional development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1509–1519. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1587159

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: Place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007

- Lund, K. A. (2013). Experiencing nature in nature-based tourism. Tourist Studies, 13(2), 156–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797613490373

- McBurney, Y. (1993). Life at Dundullimal.

- Moore, L., & Williams, S. (2001). The true story of Jimmy Governor. Allen & Unwin.

- Mullins, P. M. (2009). Living stories of the landscape: Perception of place through canoeing in Canada’s North. Tourism Geographies, 11(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680902827191

- National Trust. (2023). Dundullimal Homestead. https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/places/dundullimal-homestead/.

- National Trust. (n.d). Dundullimal Homestead [Pamphlet],

- Randell-Moon, H. (2020). Coloniality, tourism, and city-branding as an apparatus of forgetting in Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand. In D. Linehan, I. D. Clark & P. F. Xie (Eds.), Colonialism, tourism and place: Global transformations in tourist destinations (pp. 163–179). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Randell-Moon, H., & Randell, A. J. (2020). Bureaucracy as politics in action in parks and recreation. New Formations, 100(100), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.3898/neWF:100-101.11.2020

- Seiver, B., & Matthews, A. (2016). Beyond whiteness: A comparative analysis of representations of Aboriginality in tourism destination images in New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(8-9), 1298–1314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1182537

- Tripura, K., Butler, G., Szili, G., & Hannam, K. (2023). Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism: Tourism stories from the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Tourism Geographies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2023.2231424

- Walter, P. (2023). Settler colonialism and the violent geographies of tourism in the California redwoods. Tourism Geographies, 25(1), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1867888

- Wise, J., & McLean, L. (2020). “Pack of thieves?”: The visual representation of prisoners and convicts in dark tourist sites. In M. Harmes, M. Harmes & B. Harmes (eds.), The Palgrave handbook of incarceration in popular culture (pp. 555–573). Springer.

- Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native. Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240