There is a strange passive consensus on the social significance of work. It often seems that the less we need it for production, the more we depend on it for social integration, belonging and identity. In fact, work appears to be the only way towards an adequate socioeconomic status, to the point that its perception has completely changed. Over the history of the species it was almost exclusively a necessity to ensure subsistence, an obligation. In the last decades in capitalist societies it has become a right. This is a shocking development because it establishes a universal consensus – even among otherwise rival actors (e.g. employers, trade unions, the unemployed) – that social belonging is not an automatic effect of mere physical existence; henceforth, the capacity to prove one's use for some system or another is indispensable for any postindustrial human being. Even when decent income support is available for those who do not work, they remain “excluded”, a neologism indicating that there is something fundamentally “inclusive” about holding a job and bringing home some wages, however meagre.

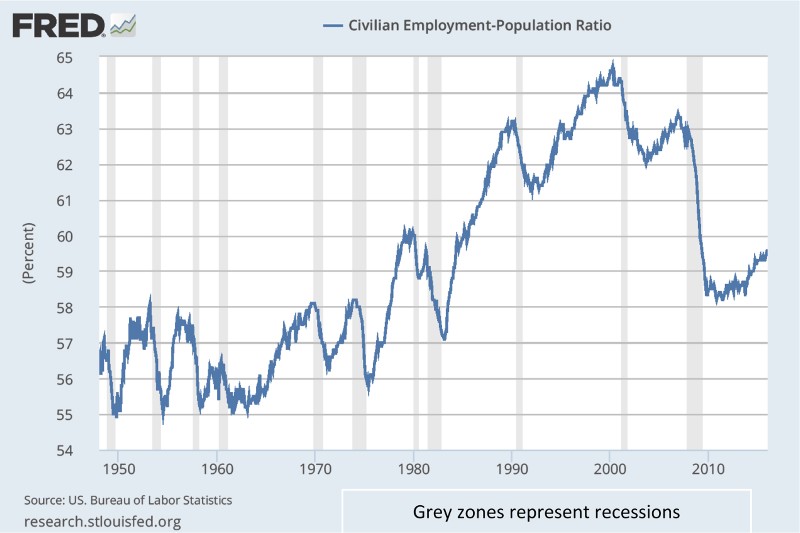

We must ask ourselves why people need two salaries to maintain a household in societies that after the Second World War had an employment rate of about 55%, as the graph below shows for the US. For, it is not unreasonable to think that if half of the active population suffices to maintain abundance for everyone and if intelligent machines increasingly reduce the need for work, work is more of a problem than of a solution towards social well-being.

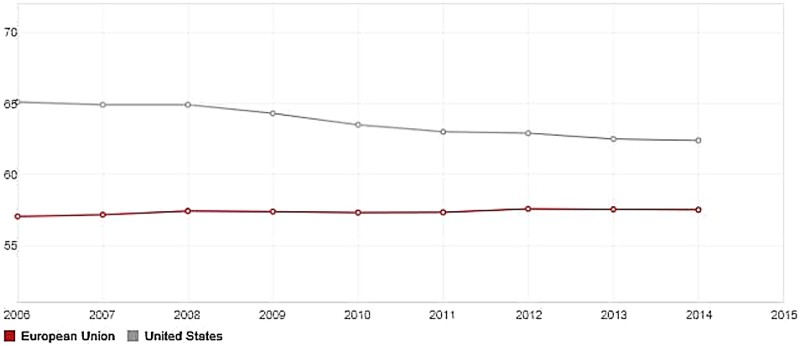

Perhaps now is the time to stop considering unemployment as a deficient condition and start thinking seriously about a society where ever fewer people work ever less. From a sociological point of view, this should be much more obvious than it currently appears. Not only successive spectacular reductions of working hours have taken place in recent history, but simultaneously the very same societies have succeeded in integrating women into the labour force. Sociology is probably the discipline to know best that social competition does not operate because of consumption, accumulation, and unequal income distribution. It is merely expressed in these areas today and will move to other areas if these disappear. So to speak, wealth is not a cause but an outcome of social competition. As a result, pursuing economic “growth” in order to “create jobs” becomes today both socially unnecessary and environmentally deleterious. From that angle, our problem is not the obscene and senseless concentration of capital in the hands of the few, it is that we still tightly condition income and socioeconomic participation for the many upon work. We are probably destined to live in a global society where work is less needed. This is already so in postindustrial societies whose employment rates increasingly converge as the graph below shows.

World Bank, Labour force participation rate (% of total population ages 15+) (modelled ILO estimate).

The political question that sociology could help to address is that of the best transition towards new conduits of social participation, cooperation, emulation and competition. As the financial markets prove every day, value can be generated on sheer belief, provided that some tenuous link with “reality” can still be defended from time to time. Other social obligations – less rare than work – can take over and lead us to societies where human utility will not be in question.

However, for such transitions to take place peacefully, trust in institutions and in other people is essential. As Saravia argues, trust across European societies depends on a balanced combination of heterogeneous factors; namely, a solid normative framework, a capacity for free individual action and a high degree of social cohesion and equality. This means that our collective appreciation of others is much more complex than usually thought and that any market configuration, including that of the labour market, is not highly trusted if it does not deliver both social cohesion and individual prosperity. In fact, even solidarity for those who struggle to secure an income is selective. Emery points out that family and friends tend to help financially those who receive ‘active’ public support and are seen by institutions as likely to get a job and achieve an adequate social status. On the contrary, those who receive ‘passive’ public assistance, such as the unemployed, do not receive additional support from friends and family. It is really striking that we seem to select even the needy close to us, on their prospects of success in the ‘labour market’. It is obvious that major decisions are being made on the basis of getting a “steady” job, but it is less obvious that such decisions have strong intergenerational effects that impact family planning as Riise, Dommermuth & Lyngstad point out. Another important issue is that access to work determines social roles, including gender roles. For example, even in affluent welfare societies, childcare becomes an alternative to ‘unemployment’ instead of being a valued equivalent to work. As a result, the choice that Nordic cash-for-childcare schemes aimed to provide, largely turns to a lack of alternatives for the parent that is less likely to obtain paid employment (Duvander & Ellingsæter). Women are of course strongly overrepresented in that ‘choice’. This is one of the many invisible perverse effects of using work as the primary domain of social integration. Another one is the gender pay gap. Grönlund & Magnusson address the great force and complexity that governs the link between work remuneration and gender, which cannot be entirely explained by the effects of childbearing and the trade-off hypothesis. Probably, in becoming the main sphere of social existence, work carries all the markers of symbolic social struggles and concentrates competition beyond work-related skills and performance. There is no personal adequacy without work, therefore no masculine personal adequacy either. Any risk must and will be undertaken and any means will be used in order to prove one's primacy and reach the top. Which takes us to the relation between elites and society at large. One of the most attractive forms of power is unpunished abuse, which today takes a systemic, “soft”, networked form. Unaccountable elites (Pawlak, book review) are in the position to exploit obsolete political systems and social participants fearful of social and professional falling. Structural manipulation increasingly replaces precise deviant acts. Complexity shields that manipulation from clear comprehension and that is why intentional democratic change is now less a matter of revolutionary violent conflict and more a matter of politically redesigning our own societies. The role of work and its increasing scarcity seems to be at the certain of that new design.