?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article examines cross-national differences in solidarity towards immigrants in the EU. This concept of solidarity is operationalized through perceived ethnic threat vs. a positive view of multicultural society. The main argument of this article is that ‘classical’ enduring determinants (sociodemographic factors, subjective values and structural factors) are still able to explain ethnocentrism, but these factors are enriched and mediated by a cluster of five emerging explanatory factors which reflect societal malaise. These factors include dissatisfaction with society, political distrust, fear of social decline, lack of recognition, and social distrust. The thesis of societal malaise as a powerful concept to explain contemporary restrictions of macro-solidarity is tested with a Multiple-Group Structural Equation Model using data from 21 countries of the European Social Survey (wave 6 2012). A theory-guided approach is used to categorize European nations into six heterogeneous European areas. Statistical analyses reveal that new emerging factors of societal malaise indeed act as a mediator of classical explanations of ethnocentrism. From a comparative perspective, the determinants of macro-solidarity are strongly heterogeneous throughout the six European areas particularly between the East and West of the European Union.

Introduction: societal malaise and solidarity constraints in the aftermath of the economic crisis and in the context of the refugee challenge

Over the last decade, the long-lasting impact of the economic crisis in Europe and the ongoing challenges concerning refugees and migrant integration have stimulated public opinion that European institutions, as well as national politicians, are powerless actors within crucial periods of societal change. It is the aim of this article to view current public fears of societal decline, processes of political alienation and aspects of social distrust as symptoms of one central development: a rise in societal malaise. The term malaise is derived from medical science and describes general feelings of discomfort or a lack of wellbeing (see National Institute of Health Citation2016). But in recent years the concept has also been used in a societal sense, to refer to societies that are ‘afflicted with a deep cultural malaise’ (see Oxford Dictionaries Citation2018). This second connotation encompasses underlying beliefs that a society is not in good health. Certain uses of the term describe visions of decline, feelings of anomie, and a lack of both political and personal trust (see Elchardus and de Keere Citation2013: 103f.). It is notable that these restrictions in societal wellbeing are able to diminish social cohesion, increase value polarizations and strengthen populist politicians opting for renationalization and ethnic homogeneity (e.g. Elchardus and Siongers Citation2001; Elchardus and Spruyt Citation2012, Perrineau Citation2011). Thus, it is not surprising that studies on societal pessimism (Steenvorden Citation2016), new concepts of wellbeing (see Glatzer Citation2006; Harrison, Jowell, and Sibley Citation2011) and issues of solidarity are back on the agenda of cross-national research (see for instance Ellison Citation2012; Gerhards and Lengfeld Citation2015).

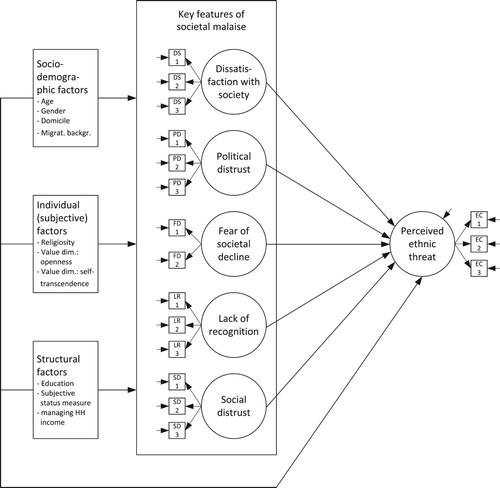

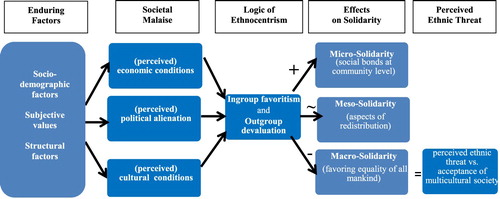

In this paper, we suggest the following model to explain solidarity constraints, particularly when it comes to immigrants (see ). Campbelĺs (Citation1965) original realistic group conflict theory (RCT) proposes that competition, with regard to scarce resources, is mainly relevant to cause conflicts and to raise hostility towards out-groups. Social Identity Theory (SIT) (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979) has successfully complemented these theoretical arguments by showing that mere perceptions and even artificially created ones are sufficient to produce intergroup conflicts (cf. Fisher Citation1993: 110f).

Figure 1. Conceptual model concerning the impact of enduring and emerging determinants on solidarity constraints.

When certain social groups in society are exposed to particular problematic economic, political or cultural conditions, it can be assumed that those specific people, experiencing societal malaise, react with ethnocentrism. This notion, originally developed by Sumner (Citation1959) [orig. 1907], refers to a kind of tunnel vision ‘in which one's own group is the center of everything’ (Sumner Citation1959: 13). This narrow focus of ingroup favoritism and outgroup devaluation exerts diverse impacts on solidarity and social cohesion. It is necessary to distinguish – in line with Denz (Citation2003) – three different scopes of solidarity, which represent a gradual extension from social ties at the community level to universal norms of equality. The first form is micro-solidarity, which is generally expressed to relatives and neighbors and is based on attachment and reciprocity (see Kriesi Citation2007). At this level, solidarity stands for social bonds and represents the still existing or, in times of crisis, even reactivated areas of social cohesion at the community level (see for instance Friedkin Citation2004). If the scope of solidarity transgresses the borders of the community, solidarity at this meso-level refers to attitudes of social support and highlights aspects of social inequality across societal groups. Here, acts of solidarity vary consistently between groups and it is not easy to propose unidirectional effects due to societal perceptions of crisis. If people maintain a cosmopolitan orientation, they generalize the principles of the common good from national borders to all mankind. This concept of macro-solidarity, which is noticeably threatened in socially turbulent times, describes the ability of the people to accept all human beings as equal and to give them fair chances in their way of living (see for instance Scherr Citation2013). We assume that ethnocentrism is a central consequence of societal malaise (e.g. Aschauer Citation2016). It directly affects macro-solidarity in a negative way because ethnocentric persons are unwilling to understand cultures that are different from their own. Following the famous conceptualization of Allport (Citation1954), who defined prejudice as an antipathy based upon inflexible generalization, our empirical strategy to explore the dynamics of macro-solidarity is through a cross-national analysis of attitudes towards immigrants. The classical items measuring perceived ethnic threat vs. acceptance of cultural diversity can be conceptualized as a proxy measurement of macro-solidarity and serve as the main dependent variable of our study (see the last column of ). The main objective of this research article is to test whether classical sociodemographic and sociostructural factors are still able to explain perceived ethnic threat or whether these factors are enriched and mediated by our new emerging explanatory factor of societal malaise. These two levels of explanation reflect the main independent variables of our study (see the first two columns of ).

Our analysis is based on the empirical data of the European Social Survey (wave 6, 2012), where we selected all 21 member states of the European Union that took part in the survey. We decided to focus solely on member states of the European Union because regional disparities and new cleavages between European areas are clearly linked with EU-policies (e.g. Beck Citation2012). Despite the central aim of the EU to reduce regional discrepancies, inequalities between European member states have started to rise particularly after the Eastern European Enlargement in 2004 (see Fredriksen Citation2012: 18). Furthermore, the financial crises and its aftermath have dramatically increased the divergence between Northern and Central European states and peripheral Southern and Eastern European countries (e.g. Heidenreich Citation2014).

Our theoretical approach is tested with a multi-group structural equation model which is the most appropriate approach for our purposes since perceived ethnic threat, as well as dimensions of societal malaise, are latent variables that are operationalized by multiple indicators. This methodological strategy has several advantages. Firstly, structural equation models are able to simultaneously analyze direct, indirect and total effects on perceived ethnic threat to provide insights into different attitudinal dynamics in certain European regions. Secondly, this method allows for estimating the relationships between latent constructs and multiple indicators while taking measurement errors into account (e.g. Kline Citation2011). And thirdly, with multi-group structural equation modeling it is possible to test for measurement invariance between groups in cross-national studies (e.g. Davidov et al. Citation2014).

Apart from this methodological strategy to assess the determinants of macro-solidarity, we also aim to focus on the diverse dynamics of macro-solidarity across major regions in the EU. Hence, we propose a typology of six European areas, based on welfare state research, to separately analyze the dynamics of perceived ethnic threat in European areas. It is thus important to form theoretically-driven distinctions of different European areas to take new cleavages across the EU more adequately into account in comparative research.

This innovative theoretical approach on European dynamics and the inclusion of new explanatory factors should provide new perspectives and offer new ways in the research on perceived ethnic threat. The rise of ethnocentrism leading to constraints in macro-solidarity is mainly viewed as a direct consequence of the citizens’ perceptions of crises and the rapid societal transformations in Europe.

Classical predictors of critical attitudes towards immigrants

Individual, sociodemographic, and structural predictors, as well as classical items to measure attitudes towards immigrants, are in the focus of important national (e.g. special modules of the survey ALLBUS in Germany) and cross-national research tools (e.g. special modules of the ESS on attitudes towards immigrants) and have thus been extensively empirically documented (for a recent review see Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010).

Evidence regarding sociostructural and sociodemographic characteristics influencing attitudes towards immigrants is quite consistent in research. It seems that a higher age reduces solidarity towards immigrants while no clear or mixed results are found regarding gender and religion (e.g. Billiet Citation1995; Chandler and Tsai Citation2001; Eisinga et al. Citation1999). The educational level is generally identified as one key determinant of ethnic prejudice (Hello, Scheepers and Gjisberts Citation2002; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003).

Meeussen, de Vroome and Hooghe (Citation2013) found out that cognitive skills seem to be relevant for coping with social complexity and for feeling more secure in different interaction settings. Thus, apart from education, a higher socioeconomic status tends to be negatively correlated with prejudice (Semyonov et al. Citation2004). Another consistent result is that people living in urban areas exhibit lower levels of prejudice (e.g. Coenders and Scheepers Citation2008).

Dating back to the 1960s, other concepts, originally developed by social psychology, focused on the effect of values on prejudice. The Schwartz (Citation1992) value model plays a central role in contemporary cross-national research. While self-transcendence values such as universalism are related to positive attitudes towards immigrants, self-enhancement values such as power increase ethnocentrism. The other higher-order dimension of Schwartz (Citation1992) is equally important, where openness to change leads to a higher approval of cultural diversity and conservative values provoke ethnocentrism (Sagiv and Schwartz Citation1995). This is not surprising, as these values are related to authoritarianism (e.g. Altemeyer Citation1998) and social dominance orientation (Sidanius and Pratto Citation1999), which reflect two established approaches in the research on prejudice. Davidov et al. (Citation2008) could recently confirm a stable influence of these value dimensions on attitudes towards immigrants in 19 European States (based on the first wave of the ESS 2002), which were also robust after controlling for several other influence factors.

Cross-national research demonstrates that, particularly in Western Europe, the aforementioned conditions considerably influence negative attitudes towards immigrants, as opposed to in Eastern Europe where often only weak explanations are found (see Zick, Pettigrew and Wagner Citation2008; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Hjerm Citation2001). Due to significant solidarity differences between European areas, it is impossible to generalize all those different dynamics under a broad European picture. Perhaps, this may account for those recent studies (e.g. Hooghe et al. Citation2009 or Biliett, Meulemann and De Witte Citation2014) that fail to achieve clear results and report a mixed picture for Europe. It seems impossible to derive stable contextual factors in multi-level models.

For this reason, we (1) have decided to focus on a new multidimensional concept to explain prejudice based on societal developments, namely societal malaise and (2) have chosen a theoretically driven strategy, which allows to address the different regional dynamics across Europe. The next section presents this theoretical conception of the heterogeneous European areas, which is followed by the theoretical background and preliminary studies on certain features of malaise.

A conception of heterogeneous European areas

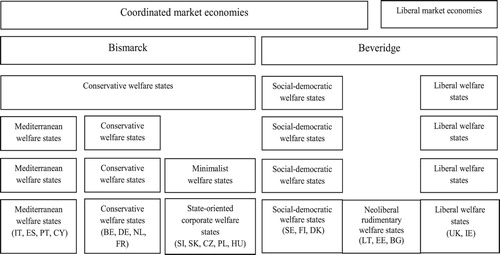

The comprehensive typology of European states is mainly based on the ideas of Schröder (Citation2013) who tries to combine the varieties of capitalism approaches with new developments in welfare research. Our differentiation of six European major regions starts with the research on different varieties of capitalism (e.g. Hall and Thelen Citation2008) (see the first line of ), by separating coordinated market economies from liberal market economies. Liberal welfare states such as Great Britain or Ireland emphasize the role of the free market, while conservative welfare states (such as Germany, Austria and France) are more based on the Bismarck model, where social security is linked to social status and employment relationship. The original intention of Beveridge to guarantee a universal security system for the whole population is more closely fulfilled in the social-democratic welfare regimes of Scandinavia (see line 2). In those states, a high level of decommodification has led to the protection of a higher number of citizens from labor-market risks. These characteristics lead to the central typology of Esping-Andersen (Citation1990), which is still predominantly used in welfare state research (see the third line). Following Esping-Andersen (Citation1990), many researchers have tried to extend his typology to accommodate more substantial distinctions between European areas. A fourth type of welfare regime has been suggested for Southern European states, which may be classified as familialistic (e.g. Ferrera Citation1996) (see forth line). In order to secure a fine-tuned and comprehensive typology of European states, it is unsuitable to consider Eastern Europe as a single area of a minimalist welfare model (see line 5). Schröder (Citation2013) highlights that varieties of capitalism and welfare structures go hand in hand with certain cultural characteristics of the nation states. For example, in Eastern Europe the different features of the welfare states are based on cultural and religious foundations. In the Central Eastern European states Catholicism maintained its influence, while the Baltic States were more strongly affected by Protestantism (cf. Kollmorgen Citation2009: 83f).

Figure 2. A typology of six European areas based on the varieties of capitalism approach and welfare-state research (modified and extended according to Schröder Citation2013: 59).

Kollmorgen (Citation2009) – with reference to Eastern Europe – opts for a further distinction of additional welfare types, arguing that the Baltic states demonstrate similarities to liberal welfare regimes, while the Visegrad countries, together with Slovenia, are best classified as minimalistic welfare states in line with the Bismarck model. These insights in contemporary welfare-state research justify a theoretically driven distinction between six European areas (see line 6 of ).

The impact of societal malaise on attitudes towards immigrants

Impressions of societal malaise are certainly interwoven with different welfare state arrangements in Europe. Perceived crises states in society are often described by the following five crucial factors which are interconnected with economic, political, and cultural conditions: EU citizens express a fear of social decline and feelings of recognition are challenged (economic level), they show increasing levels of societal dissatisfaction and political distrust (political level), and they may react with social distrust to infiltrations of their own culture (cultural/cohesive level).

Fears of social decline and feelings of recognition

Citizens in Western Europe often consider the ‘golden decades’ of the second half of the twentieth century as an era of peace-building, economic growth, political stability, and European integration (e.g. Castel Citation2000). Current middle-class fears (e.g. Burzan and Berger Citation2010) can best be attributed to changes in expectations for the future, as EU citizens seem to have the impression that European stability is illusory. It is important to distinguish expressions of social descent among the middle classes from the experiences of social groups who are clearly underprivileged. In many European states, we can observe a worsening of the lives of the poor, where restrictions of objective living conditions are clearly apparent. Feelings of recognition (e.g. from a broad theoretical perspective, Honneth Citation1992) should also be taken into account as people in the lower class of contemporary society may feel neglected because they perceive a lack of advancement opportunities in society. Fears of social decline and feelings of recognition are best reflected by relative deprivation theory (firstly developed by Stouffer et al. Citation1949) and can be linked to classical economic explanations of group conflict. Individual relative deprivation represents impressions of a disadvantaged position when compared to group members, while fraternal deprivation means that the whole situation of the ingroup is perceived negatively in comparison with outgroups (see Pettigrew et al. Citation2008: 386). Feelings of deprivation can also be measured by highlighting anticipations for the future. If people perceive their lives as getting worse and if they express a high level of future pessimism then immigrants may serve as scapegoats for rapid societal transformations. If people feel excluded from society and perceive a lack of recognition, their frustration of being underprivileged can easily be transformed into aggression towards other weak groups of society (see the frustration-aggression thesis, originally by Dollard Citation1971).

Societal dissatisfaction and political disenchantment

Although situations of structural crises are important to explain ethnocentrism, recent studies show that indicators of trust (e.g. van der Linden et al. Citation2017) are more powerful concepts to explain absence of solidarity towards immigrants. Impressions of a lack of societal functioning can be best explained by the sociological anomie theory, originally developed by Durkheim (Citation1983 [1897]). Citizens witness significant disruptions to social order (e.g. an unforeseen, influx of countless refugees), which leaves them feeling like uninvolved bystanders in a nation state with porous borders. Crises states at this level of societal functioning can be measured with indicators of societal dissatisfaction and political trust. People who no longer feel represented by their democratic institutions (see Linden and Thaa Citation2011) tend to gravitate towards questionable Internet sources and are increasingly susceptible to conspiracy theories. They accuse the elites of society for their policies of favoring cultural diversity, which is seen as the root cause for the withering of the welfare state. Interestingly, although the relations between cultural diversity and social trust (see the next section) is an emerging topic of the research on ethnic prejudice, an empirically wide-ranging examination of the links between political distrust and critical attitudes towards immigrants is more or less absent.Footnote1

Social distrust

In recent years, the impact of ethnic diversity on trust and social cohesion has become a hotly debated topic by society. Research coming out of the United States clearly confirms that trust levels tend to be lower in racially diverse cities and neighborhoods (e.g. Putnam Citation2007). Hooghe et al. (Citation2009) conducted a comprehensive study with a large variety of diversity indicators to test this thesis in a European context. But the results were mixed across Europe, with only two of the indicators (stock of foreign population and rise of the number of foreign workers) being significant. While many studies view contextual factors (e.g. proportion of immigrants) as an independent variable influencing social trust, only a few studies assume a mutual relationship and view social trust as a determining factor of a higher solidarity towards immigrants. In an interesting study, van der Linden et al. (Citation2017) found that generalized trust is a necessary precondition for embedding immigrants in the radius of ‘trusted others’ and for guaranteeing a higher level of social cohesion.

Based on this new research agenda, which gives societal developments a higher weight in the research of perceived ethnic threat across Europe, we put forward four empirical propositions. The first empirical proposition deals with the concept of societal malaise. We test the cross-cultural equivalence of the construct and prepare some descriptive results to highlight the discrepancies across European areas. We assume that societal malaise can be conceptualized as a higher order construct of five latent factors (fears of social descent, feelings of recognition, societal dissatisfaction and political and social distrust) that demonstrate at least metric invariance across different European areas. Thus, in a comparative perspective, this concept can be used as a new multi-dimensional impact factor to explain perceived ethnic threat.

The second empirical proposition refers to the added value to deal with the subordinate factors of the concept. We expect that they would vary in their predictive power but are consistent positive predictors, leading to a higher level of perceived ethnic threat.

The third main proposition refers to our central research aim of establishing societal malaise as an emerging concept for explaining perceived ethnic threat. Our empirical proposition states that in our model, the five subordinate factors of malaise function by mediating the effects of sociodemographic, individual-subjective background variables and structural factors on perceived ethnic threat.

In line with the often reported results of diverse effects across Europe especially regarding the East and West divide (see Zick, Pettigrew and Wagner Citation2008; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Hjerm Citation2001), our fourth proposition states that these perceptions of crises exert a stronger influence on perceived ethnic threat in the regions of Western Europe compared to Eastern European areas. We aim to analyze the dynamics of perceived ethnic threat in Europe with an even more sophisticated approach, theoretically distinguishing six European areas.

Empirical approach

Data and operationalization

The empirical analysis is based on the European Social Survey (wave 6, 2012) and includes 21 EU-member states, with a total sample size of n = 32,478, into our analyses. Following the typology of European countries categorized into six areas (see ), our sample consists of 5,017 cases from social-democratic welfare states (group 1; DK, SE, FI), 7,735 cases from conservative welfare states (group 2; NL, BE, DE, FR), 3,895 cases from liberal welfare states (group 3; GB, IE), 4,773 cases from Mediterranean welfare states (group 4; CY, IT, ES, PT), 6,391 cases from corporate welfare states (group 5; CZ, SK, HU, PL, SI), and 4,667 cases from neoliberal-rudimentary welfare states (group 6; EE, LT, BG). As mentioned earlier, the subsequent empirical analysis is theoretically driven and leads on to a comprehensive evaluation of enduring and emerging determinants of perceived ethnic threat. This is illustrated in , which provides an overview of all the variables of the analysis. As previously stated, the key features of societal malaise act as mediator variables, which partly explain the effects of the ‘classical’ impact factors of perceived ethnic threat.Footnote2

The selection of indicators to measure classical predictors of perceived ethnic threat takes into account several explanatory factors. Age and gender, as well as domicile, refer to important sociodemographic variables, which may influence perceived ethnic threat. Additionally, a migration background (having been born in another country or being a member of an ethnic minority) was introduced as a control variable because it is assumed that immigrants demonstrate a higher level of approval towards cultural diversity.Footnote3 The classical individual predictors of perceived ethnic threat include religiosity (measured with a five-point scale) and values. Schwartz’s (Citation1992) bipolar value dimensions were included into the model, as it has frequently been found that these higher-order values exert a stable influence on ethnocentrism (see Davidov et al. Citation2008).

The structural factors refer to classical predictors, which can be treated as resources needed for advancement in society such as education, social status and income. The decision was made to use two subjective measurements that address feelings of belonging to either the top or bottom social strata and impressions of whether it is easy or difficult to get along with one's own household income. The operationalization of perceived ethnic threat vs. acceptance of multicultural societies and the multifaceted measurement of perceptions of crisis are shown in .

Table 1. Operationalization of the latent constructs of societal malaise and perceived ethnic threat (ESS data 2012).

Our dependent variable consists of three central items of the ESS, which are often used to assess ethnic threat (e.g. Schneider Citation2007; Manevska and Achterberg Citation2013) and have also been tested for equivalence in cross-national studies (e.g. Billiet, Meuleman and De Witte Citation2014).

Societal malaise encompasses five subordinate factors which all measure various feelings of discomfort towards society. Political trust represents a classical measurement where similar items are used for several cross-national surveys (such as the European Values Study and the World Values Survey). A central measurement to capture political crises states in society is dissatisfaction with societal developments. Perceptions of economic crisis are measured by fears of social decline. The first two items refer to future pessimism, while the other three predominantly deal with individual feelings of recognition in society (see ). Impressions of cohesion are operationalized by using the concept of social distrust (again measured with three classical items). The dependent variable represents our proxy-measurement of macro-solidarity. Hence, if people follow a cosmopolitan orientation then they approve cultural diversity. However, if people perceive immigrants as a threat to Western culture then they express ethnic threat. Thus, the classical items to measure attitudes towards immigrants seem suitable for operationalizing macro-solidarity in order to analyze the dynamics of exclusionary attitudes in a comparative way across Europe.

Empirical results: construct validity of societal malaise

For a cross-regional comparative study, it is a necessary precondition that the ‘factorial invariance’ (aka ‘measurement equivalence’) of the measurement models is given (see Bachleitner et al. Citation2014; Davidov et al. Citation2014; Mayerl Citation2016). Since we are interested in differences between groups, in terms of the mechanisms that explain perceived ethnic threat, two types of invariance are most important: configural invariance and metric invariance. Configural invariance asks whether there is an equivalent structure of the measurement models in all groups, thus each latent construct has to be operationalized by the same indicators across all groups. Metric invariance is observed when the unstandardized factor loadings of the indicators are identical across all groups. In other words: metric invariance formulates the need that the weighing (‘mix’) of all indicators within each latent variable is consistent across groups to ensure the same empirical structure of the latent constructs (Mayerl Citation2016: 188).

In order to explore our first proposition, we test the cross-cultural equivalence of the concept of societal malaise. A confirmatory factor analysis of perceived ethnic threat and the five latent dimensions of societal malaise with metric measurement invariance revealed a high degree of construct validity.Footnote4 All five latent dimensions of societal malaise correlate positively with each other (p < 0.05), with a mean inter-construct correlation in a range of

= 0.29 (Mediterranean) to

= 0.39 (conservative). The mean correlations are even higher without the dimension of lack of recognition, resulting in a range of a mean correlation of

= 0.41 (Mediterranean) up to

= 0.57 (conservative).

Since most inter-construct correlations revealed medium to strong associations, we further estimated a multiple group CFA with a latent second-order factor to explore whether all five first-order constructs share a common higher order construct, which we call societal malaise. According to , there is indeed empirical evidence for a second-order structure in all six European areas. Most of the measurement paths are strong with standardized coefficients >0.5. The only exception is ‘Lack of Recognition’ that has lower but still significant standardized effects around 0.2. Additionally, the model fit of the second order CFA model is good, even under the condition of metric measurement equivalence of the first and second order paths.

Table 2. Second Order Multiple Group CFA.

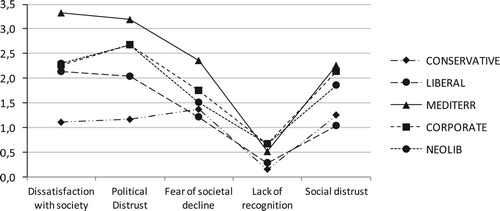

Another approach, to explore whether the five latent constructs are dimensions of a common factor, is to look at the level of latent means and to evaluate the consistency of the mean structure throughout the six major European regions. Tests of latent mean differences in multiple group models require the specification of scalar invariance. This would mean that indicator intercepts are the same across groups so any cross-group differences are the result of differences in latent means (Mayerl Citation2016: 189). By using multiple group structural equation modeling, latent means of constructs can be tested as absolute mean differences in comparison to the latent mean of the constructs in the reference group (in our case: social-democratic area). As seen in , the multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis, with metric and scalar invariance, shows an acceptable global fit. Thus, the latent mean differences can be substantively interpreted. All areas show a higher mean level of societal malaise in contrast to the social-democratic area (reference group). Public perceptions of crisis have emerged, also in conservative welfare states, but are still far more pronounced in Eastern Europe. The highest level of societal malaise can be observed in the Mediterranean area. All in all, the ranking of European areas is highly consistent for all sub-dimensions of societal malaise. The only dimension, which shows a lower mean level and low discriminance between the six areas, is lack of recognition (although notably, all latent means are higher than the mean in the reference group, p < 0.01).Footnote5 On the whole, we find a high consistency of the latent mean structure throughout all areas.

Figure 4. Latent means of the sub-dimension of societal malaise.

Notes: Model fit (metric and scalar invariance): Chi2 = 11860.302, df = 686, p = 0.000; RMSEA = .053 (C.I. 90%: .052-.054); CFI = .953; SRMR = .040; Reference group: Social-Democratic area.

Most importantly, according to the results of the second order analysis, there is empirical evidence that it is adequate to interpret all five latent constructs as sub-dimensions of one common concept.

Empirical results: explanation of perceived ethnic threat

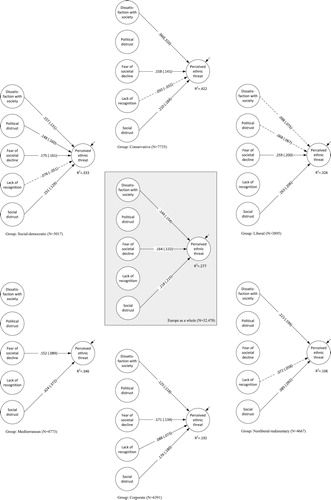

By the next step, we are interested in the question of whether the five dimensions of societal malaise differ in their predictive power towards perceived ethnic threat (second proposition), their power to act as mediator variables (third proposition) and whether there are differences between the six regional groups (fourth proposition). For these reasons, we subsequently report the results of latent path models differentiating the five dimensions without specification of a second order construct (see ).Footnote6

We test our explanation model by way of a multiple group structural equation modeling approach using ML estimator.Footnote7 The five dimensions of societal malaise are specified as mediator variables according to . The overall sample size is N = 32,478 cases. Multiple groups are defined according to the six European areas (see ).Footnote8

and report the empirical results. According to , all factor loadings are statistically significant (p < 0.001) and all standardized factor loadings are higher than 0.5 (with the exception of indicator LR3 of the construct ‘Lack of Recognition’ with factor loadings higher than 0.4 in three groups). The goodness of fit for the model (see ) with metric invariance is very good according to commonly used thresholds of CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.05 and SRMR < 0.05 (e.g. Kline Citation2011).

Table 3. Factor loadings of all latent constructs in the full structural equation model.

Table 4. The effect decomposition of background variables and societal malaise explaining perceived ethnic threat.

reports the estimated path coefficients of the explanation model shown in . According to this model, we distinguish between three groups of ‘classical’ background variables namely, sociodemographic factors, individual subjective factors, and structural factors. These affect perceived ethnic threat in two ways: (a) direct effects and (b) indirect effects, mediated by the five factors of societal malaise (dissatisfaction with society, political distrust, fear of societal decline, lack of recognition, and social distrust). Hence, reports three types of effects on perceived ethnic threat for each background variable: total effect (=sum of all direct and indirect effects), direct effect, and total indirect effect (=sum of all indirect effects, i.e. effects mediated by societal malaise). The occurrence of a mediation effect can be evaluated by looking at the significance and strength of the indirect effects and by examining the decrease of the direct effect of the predictor variable when controlling the mediator variables. Thus, comparing the total effect with the remaining direct effect, the stronger the total effect and the smaller the direct effect, the stronger is the mediation effect. Total mediation is given when no significant direct effect remains and the total effect occurs only due to indirect effects. A necessary condition for mediation is that the mediator variables significantly affect the dependent variable or in our case that the different types of societal malaise affect perceived ethnic threat.

As shown in and in line with our second proposition, all five mediators do have a significant impact on perceived ethnic threat across the six groups. However, there are remarkable differences between these groups ( illustrates these differences). The social-democratic region is the only group where all five levels of societal malaise significantly explain perceived ethnic threat (p < 0.05), with no dominant variable in terms of effect size. In the conservative region, ethnic threat is mainly affected by dissatisfaction with society, while political distrust does not play any significant role. In the liberal countries, social distrust and fear of social decline are the specific driving forces of perceived ethnic threat, while lack of recognition does not significantly affect our dependent variable. In the Mediterranean region, critical attitudes towards immigrants are only explained by two impact factors, with social distrust being the main predictor followed by fear of social decline. A different picture emerges when the Eastern European regions are taken into account. The Central Eastern European region shows four significant effects, which are in general rather weak, and there is no dominant predictor (political distrust with no impact on perceived ethnic threat). Looking at the sixth group of the rudimentary welfare states (the Baltic nations and Bulgaria), ethnic threat is mainly predicted by dissatisfaction with society, while the other dimension of societal malaise exert only a weak influence.

Figure 5. Social malaise and perceived ethnic threat in Europe: empirical results.

Notes: solid line p < 0.01; dotted line p < 0.05; no line: p > 0.05; unstandardized coefficients (standardized); Model fit (with metric invariance): see table 3; All effects controlled for gender, age, domicile, migration background, religiosity, social values openness and self-transcendence, education, social class and getting along with household income (N.B. direct and indirect effects of these background variables not shown).

On the whole, social distrust is the only dimension of societal malaise, which significantly affects critical attitudes towards immigrants in all six European areas. Accordingly, dissatisfaction with society and fear of societal decline are significant predictors in five out of six areas. Political distrust is a significant predictor variable only in conservative and liberal areas, while lack of recognition shows mixed results with two weak but significantly positive and two weak but significantly negative effects. The regional variation of the predictive power of the dimensions of societal malaise is also demonstrated by looking at the results of Europe as a whole (). Two out of five dimensions would not be significant predictors of perceived ethnic threat in this holistic view. However, this would be a misrepresentation of other European regions where these two dimensions play a significant role.

According to our third proposition, we expect that societal malaise acts as a mediator of the effects of all three types of background variables. A full mediation would be given when the direct effect of a variable is not significant and only indirect effects appear. Partial mediation appears when predictor variables show both direct and indirect effects and no mediation would be the case when indirect effects are non-significant. Looking at the full mediation effects, it can be concluded that specific variables of all three types of background variables are fully mediated in some areas: gender in the Mediterranean countries and age in the Northern welfare states, religiosity in social-democratic, conservative and liberal areas of Western Europe, self-transcendence in the neoliberal area (the Baltic states), subjective social class in all areas except for the last area of Eastern Europe and coping with income in the case of the conservative and liberal welfare states of Western Europe. In the case of all other predictor effects, some are not mediated and most of them are partly mediated.

Sociodemographic factors still show mainly direct effects on perceived ethnic threats vs. acceptance of multicultural society and there is only minor mediation through societal malaise, while the effects of structural factors are strongly mediated. In case of individual value orientations, we find stable and mediated effects across the six regions. Overall, we feel confident to state that the dimensions of societal malaise do indeed act as a mediator of classical predictors of anti-immigrant attitudes. However, there is remarkable variation in mediation power when looking at specific European areas and specific types of classical predictors.

Finally, according to our fourth proposition, the explanatory power of the model is expected to be higher in Western Europe when compared to Eastern Europe. Indeed, this is the case, since the explained variance reaches a remarkable size in the Western European regions (30% to 40%), while the model with all predictors explains only 19% in the Central Eastern European area and 11% in the neoliberal-rudimentary welfare region (Baltic states and Bulgaria). An additional comparison of the explained variance of the models, with vs. without mediator variables, underlines the importance of societal malaise for explaining perceived ethnic threat, particularly in Western Europe (the first four groups of countries). The amount of explained variance in terms of absolute percentage (R2*100) is 16%, 23%, 14%, 16%, 9% and 5% (from group 1 to group 6). It is thus higher in models including factors of societal malaise in contrast to the ‘classical’ model without these mediators.

Discussion and conclusion

This article addressed the relevance of enduring and emerging determinants on solidarity towards immigrants across European areas. It employed a sophisticated methodological approach that focused on three main research aims. Firstly, we introduced societal wellbeing vs. societal malaise as a new powerful explanatory factor of perceived ethnic threat. We conceptualized societal malaise as a cluster of five sub-dimensions namely societal dissatisfaction, political distrust, fear of social decline, social distrust and lack of recognition. Empirically, all subordinate factors loaded strongly on the higher-order concept with feelings of recognition as the only exception.Footnote9 We had the intention to provide comparable and equivalent indicators of this concept. The results of the cross-national invariance test in this study appear promising, as metric and, to a certain extent, scalar invariance could be achieved (meaning the clear acceptance of a model with equal factor loadings and fit indices fairly acceptable with equal intercepts across several European countries). It was also possible to highlight the empirical differences of societal malaise across the European areas, parallel to stable welfare state arrangements (e.g. Schröder Citation2013) and in line with economic prosperity. Societal wellbeing is widely present in Scandinavia, while in all other European regions we see signs of societal pessimism. We were able to observe a profound crisis of institutional trust, particularly when it comes to Southern Europe and some Eastern European countries. The heterogeneous results of the latent means suggest that there is no unidirectional track towards the perceptions of crisis in Europe and that welfare states play a crucial role in mitigating the effects of societal challenges on citizeńs perceptions.

In the sociology of Europe, there are notable demands to look more closely at the micro-level and highlight future challenges of social integration (see Bach Citation2008; Vobruba Citation2009). Consequently, one of the principal future challenges in comparative research is to take European citizens’ subjective perceptions into a more adequate account and to assess the dynamics of solidarity breaks across European regions. We decided to focus on the explanation of macro-solidarity where perceiving immigrants as an ethnic threat or approving a multicultural society proved to be a suitable proxy-measurement to address the solidarity constraints in a comparative perspective. The challenges of cultural diversity can be seen as one major source of dissent across Europe. Progressive groups in society may respect or even appreciate cultural heterogeneity, while those in denial of late modern transformations may shift their values in a defensive direction. In the case of the classical (enduring) determinants of anti-immigrant attitudes, the impact of sociodemographic indicators on perceived ethnic threat was rather weak in all countries but the effects turned out to be stable. Age exerted only a small influence, with elderly people being more critical toward immigrants, which confirms previous research (e.g. Chandler and Tsai Citation2001). Domicile has a marked impact on perceived ethnic threat in Western Europe, where people in big cities are more tolerant in comparison to citizens who live in the countryside. This result may also be connected to the preference of certain values in bigger cities. It was also confirmed by this study that citizens who favor openness to change and who give higher priority to equality and tolerance, demonstrate more positive opinions in relation to cultural diversity (see also Davidov et al. Citation2008). Regarding structural factors, the educational gap within anti-immigrant sentiment (e.g. Hello, Scheepers and Gjisberts Citation2002) is still clearly observable in Western Europe but, interestingly, the lowest effect of education on these sentiments was observed in the Mediterranean countries. Regarding sociostructural characteristics, there appear clear mediation effects, which are glaring evidence that ‘societal malaise’ has to be put to the fore of ethnocentrism research.

It is striking that all dimensions of societal malaise clearly exert the strongest influence on perceived ethnic threat and appear to be predominantly relevant for explaining contemporary restrictions of solidarity towards immigrants. Social trust is a particularly stable predictor in all analyzed countries of the European Union, although causality is not easy to define (see also Hooghe et al. Citation2009; van der Linden et al. Citation2017). While individual feelings of recognition are only weakly correlated with perceived ethnic threat, fears of social decline are especially relevant in the liberal welfare states but exert but exert less influence in other European areas.

It is notable that feelings of societal malaise particularly have an impact on, while the explanatory power of these factors is considerably lower in Eastern Europe. However, sociodemographic and structural predictors are not the only weak predictors for Eastern Europe (see for instance Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Hjerm Citation2001), but also economic and cultural explanations seem to play only a minor role with respect to perceived ethnic threat. According to Kunovich (Citation2004), poorer economic conditions in Eastern Europe may affect both lower and higher classes of society and therefore the differentiation of prejudice tends to be weaker. Nyiri (Citation2003) warns to view Eastern Europe as a homogenously xenophobic region and highlights that differences between Eastern European countries are as significant as between Eastern and Western European states. Economic and cultural explanations are only weak predictors of prejudice in Eastern Europe, and therefore the focus should be more on the role of politics and public discourse (see Nyiri Citation2003: 30f.). Solidarity constraints towards immigrants in the West can thus be seen as a kind of counter-movement to already existing multicultural societies, which leads to a sharper value polarization in society. It is especially the case in Western Europe that dissatisfaction with societal developments and political distrust is particularly related to perceived ethnic threat. It seems that societal groups who feel left behind blame politicians for their open-door policy concerning immigrants because they are said to be responsible for an infiltration of culture, for an exploitation of the welfare system and for a perceived increase in crime. These links highlight potential new directions in research on ethnic prejudice which should focus more directly on political climate and anti-immigrant sentiment (e.g. Semyonov et al. Citation2006), the role of the media in influencing ethnic prejudice and right-wing voting behavior (e.g. Boomgarden and Vliegenthart Citation2007), or explanations of the public view about the impact of immigrants on crime (e.g. Ceobanu Citation2011). In general, further research is needed for the explanation of such diverse effects on ethnic prejudice across Europe.

Therefore, the multidimensional model of societal wellbeing is the first major step to define new ways in comparative research on perceived ethnic threat and to give (different) societal developments in the center and on the periphery of Europe a higher value. This study provides clear insights that on one hand, the dynamics of societal malaise are highly different across Europe but, on the other hand, have crucial consequences for social cohesion of society. Hence, monitoring social change focusing on the citizens’ perceptions of crisis should therefore neither be neglected nor underestimated for future research on solidarity constraints, anti-immigrant attitudes and – in general – for political conceptions of a united Europe.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Wolfgang Aschauer is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science and Sociology at the University of Salzburg. His main research fields are quantitative methods (particularly cross-national survey research), European integration and cultural change (particularly challenges of integration and social cohesion, societal wellbeing, breaks in solidarity). In 2015, he completed his habilitation project ‘The societal malaise of EU citizens’ Causes, characteristics, consequences.’ The book was published by Springer-VS in German Language in 2017. Other journal publications: Aschauer, W. (2014) ‘Societal wellbeing in Europe. From theoretical perspectives to a multidimensional measurement’, L'Année sociologique, 64 (2): 295–329; Aschauer, W. (2016) ‘Societal malaise and ethnocentrism in the European Union: monitoring societal change by focusing on EU citizens’ perceptions of crisis’, Historical Social Research 41 (2): 307–359.

Jochen Mayerl is Professor for Sociology with a focus on Empirical Social Research at Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences, Chemnitz University of Technology, Germany. He specializes in the study of attitude-behavior relations, social context analysis, survey methodology, and Structural Equation Modeling. Selected Publications: Attitudes towards muslims and fear of terrorism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1413200, 2018 (with Andersen, H.); Social desirability and undesirability effects on survey response latencies. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology 135: 68–89, 2017 (with Andersen, H.); Environmental concern in cross-national comparison − methodological threats and measurement equivalence (pp. 182–204), in A. Telesiene and M. Groß (eds.), Green European: Environmental Behaviour and Attitudes in Europe in a Historical and Cross-Cultural Comparative Perspective, Taylor & Francis, Studies in European Sociology Series, 2016; Values, beliefs, attitudes: an empirical study on the structure of environmental concern and recycling participation. Social Science Quarterly 94(3): 691–714, 2013 (with Best, H.).

Notes

1 This is the reason why we developed this comprehensive model of societal malaise to take into account impressions of economic, social and political crises and to separately analyse their impact on perceived ethnic threat.

2 Since our data are cross-sectional, we are not able to test for causal relations but rather treat effects between independent and dependent variables as statistical associations under control of specific background variables.

3 Although immigrants are often excluded by cross-national research (e.g. Billiet, Meuleman and De Witte Citation2014), we decided to integrate them in our study, as certain immigrant groups may also express critical towards a general acceptance of multicultural societies. Cultural diversity is a reality in many European states and in a comparative perspective it is hard to judge, how to exclude ethnic minorities from a general representative population sample. The structure of immigrants (measured by foreign country of birth and self-definition of being an ethnic minority) varies considerably across Europe so it seems fruitful to consider those background variable as one independent factor in our study. Indeed effects concerning migration background are different across European areas (see ).

4 The results of a multiple group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) with configural and metric invariance show that a) both invariance assumptions can be accepted, since the model fit is good (Chi2 = 5015.590, df = 631, p = 0.000; RMSEA = .035 (C.I. 90%: .034-.035); CFI = .982; SRMR = .030), and b) that convergent validity (high factor loadings, see ), as well as discriminant validity (no cross-loadings), are given. Furthermore, the same eight error correlations had to be specified in all areas (see for the indicator labels): DS1 with PD1, FD1 and FD2; DS2 with PD1; DS3 with PD1, DS1, and DS2; and PD2 with PD3.

5 This result also seems theoretically plausible. Impressions of societal malaise vary tremendously across Europe with societal dissatisfaction, political distrust and fears of social decline being particularly high in Southern Europe. Recognition refers more specifically to the individual level of social cohesion and this level of social integration seems to be still fulfilled in most of the European countries.

6 In addition, we tested a model with societal malaise specified as second order latent construct acting as a mediator variable. In this model, there are no effects of the sub-dimensions of societal malaise on perceived ethnic threat but only an effect of the second order construct on perceived ethnic threat. Thus, the effect of the second order construct societal malaise can be interpreted as the overall aggregate effect of societal malaise on perceived ethnic threat. The model fit was acceptable with Chi2 = 15447.817, df = 1758, p = 0.000; RMSEA = .038 (C.I. 90%: .037–.038); CFI = .945; SRMR = .037 (to achieve acceptable fit, we had to specify several effects of the background variables on specific first order constructs of societal malaise in each group). As a result, the effects of societal malaise on perceived ethnic threat were statistically significant in all six groups (p < 0.01) with the following effect sizes: Group SOCDEM: unstandardized .673 (standardized .485); Group CONSERVATIVE: .718 (.567); Group LIBERAL: .573 (.385); Group MEDITERR: .599 (.344); Group CORPORATE: .337 (.259); Group NEOLIB: .333 (.280). Overall, societal malaise is a rather strong predictor in conservative and social-democratic areas, but rather weak in corporate and neoliberal areas (comparing unstandardized effects). Most important, these analyses clearly show that there is empirical evidence to treat societal malaise as a meaningful predictor of perceived ethnic threat. But since our interests are in the differences in predictive power of the sub-dimensions of societal malaise, in order to better understand the mediation function of societal malaise, we subsequently report the mediation models without specification of the second order construct.

7 ML is an appropriate estimator when the sample size is large and data are approx. normally distributed, which is the case in our study with a total sample size of N = 32,478 and acceptable values of skewness and kurtosis (all variables show a skewness of <1.5 and a kurtosis of <2.0, thus lower than the proposed rules of thumb for SEM analyzes of kurtosis < 10 and skewness < 3 according to Kline Citation2011).

8 We decided to give certain countries in the respective areas a similar weight. The use of the proportion size weight would highly overestimate the importance of larger European states (such as Germany, France or Great Britain) and would thus bias our invariance tests on the group level.

9 This low factor loading is theoretically plausible because feelings of because feelings of recognition refer more strongly to individual feelings of embeddedness. Nevertheless, recognition is an important feature of social cohesion and is still significantly correlated to the overall impressions of societal functioning.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954) The Nature of Prejudice, Oxford: Addison-Wesley.

- Altemeyer, B. (1998) ‘The other authoritarian personality’, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 30: 47–92.

- Aschauer, W. (2016) ‘Societal malaise and ethnocentrism in the European Union. monitoring societal change by focusing on EU citizenś perceptions of Crises’, Historical Social Research 41(2): 307–59.

- Bach, M. (2008) Europa ohne Gesellschaft. Politische Soziologie der europäischen Integration, Wiesbaden: Springer-VS.

- Bachleitner, R., Weichbold, M., Aschauer, W. and Pausch, M. (2014) Methodik und Methodologie interkultureller Umfrageforschung. Zur Mehrdimensionalität der funktionalen Äquivalenz, Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

- Beck, U. (2012) Das deutsche Europa. Neue Machtlandschaften im Zeichen der Krise, Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Billiet, J. (1995) ‘Church involvement, individualism, and ethnic prejudice among Flemish Roman Catholics: New evidence of a moderating effect’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 224–33. doi: 10.2307/1386767

- Billiet, J., Meuleman, B. and De Witte, H. (2014) ‘The relationship between ethnic threat and economic insecurity in times of economic crisis: analysis of European Social Survey data’, Migration Studies 2(2): 135–61. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnu023

- Boomgaarden, H. G. and Vliegenthart, R. (2007) ‘Explaining the rise of anti-immigrant parties: The role of news media content’, Electoral Studies 26(2): 404–17. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.10.018

- Burzan, N. and Berger, P. A. (ed.) (2010) Dynamiken (in) der gesellschaftlichen Mitte, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Campbell, D. T. (1965) ‘Ethnocentrism and other altruistic motives’, in D. Levine (ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 283–311.

- Castel, R. (2000) Die Metamorphosen der sozialen Frage. Eine Chronik der Lohnarbeit, Konstanz: UVK.

- Ceobanu, A. M. and Escandell, X. (2010) ‘Comparative analyses of public attitudes toward immigrants and immigration using multinational survey data: a review of theories and research’, Annual Review of Sociology 36: 309–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102651

- Ceobanu, A. M. (2011) ‘Usual suspects? Public views about immigrants’ impact on crime in European countries’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52(1–2): 114–31. doi: 10.1177/0020715210377154

- Chandler, C., and Tsai, R. and M, Y. (2001) ‘Social factors influencing immigration attitudes: an analysis of data from the General Social Survey’, The Social Science Journal 38(2): 177–88. doi: 10.1016/S0362-3319(01)00106-9

- Coenders, M. and Scheepers, P. (2003) ‘The effect of education on nationalism and ethnic exclusionism: An international comparison’, Political Psychology 24(2): 313–43. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00330

- Coenders, M. and Scheepers, P. (2008) ‘Changes in resistance to the social integration of foreigners in Germany 1980–2000: individual and contextual determinants’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34(1): 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13691830701708809

- Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Billiet, J. and Schmidt, P. (2008) ‘Values and support for immigration: a cross-country comparison’, European Sociological Review 24(5): 583–99. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcn020

- Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Cieciuch, J., Schmidt, P. and Billiet, J. (2014) ‘Measurement equivalence in cross-national Research’, Annual Review of Sociology 40: 55–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043137

- Denz, H. (2003) ‘Solidarität in Österreich. Strukturen und Trends’, SWS-Rundschau 43(3): 321–36.

- Dollard, J. (1971) Frustration und Aggression, Weinheim: Beltz.

- Durkheim, E. (1983 [1897]) Der Selbstmord, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Eisinga, R., Billiet, J. and Felling, A. (1999) ‘Christian religion and ethnic prejudice in cross-national perspective: a comparative analysis of the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium)’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology 40(3): 375–93. doi: 10.1177/002071529904000304

- Elchardus, M. and De Keere, K. (2013) ‘Social control and institutional trust: Reconsidering the effect of modernity on social malaise’, The Social Science Journal 50: 101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2012.10.004

- Elchardus, M. and Siongers, J. (2001) ‘The malaise of limitlessness’, Ethical Perspectives 8(3): 179–201. doi: 10.2143/EP.8.3.583182

- Elchardus, M. and Spruyt, B. (2012) ‘The contemporary contradictions of egalitarianism: an empirical analysis of the relationship between the old and new left/right alignments’, European Political Science Review 4(2): 217–39. doi: 10.1017/S1755773911000178

- Ellison, M. (2012) Reinventing Social Solidarity Across Europe, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Ferrera, M. (1996) ‘The Southern model of welfare in social Europe’, Journal of European Social Policy 6(1): 17–37. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600102

- Fisher, R. J. (1993) ‘Towards a social-psychological model of intergroup conflict’, in K.S. Larsen (ed.), Conflict and Social Psychology, London: Sage, pp. 109–22.

- Fredriksen, K. B. (2012) Income Inequality in the European Union, OECD Economics. Department Working Papers, No. 952. OECD Publishing, http://search.oecd.org/officialdocuments/displaydocumentpdf/?cote=ECO/WKP%282012%2929&docLanguage=En

- Friedkin, N. E. (2004) ‘Social cohesion’, Annual Review of Sociology 30: 409–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110625

- Gerhards, J. and Lengfeld, H. (2015) European Citizenship and Social Integration in the European Union, London: Routledge.

- Glatzer, W. (2006) ‘Quality of life in the European Union and the United States of America: evidence from comprehensive Indices’, Applied Research in Quality of Life 2: 169–88.

- Hall, P. A. and Thelen, K. (2008) ‘Institutional change in varieties of capitalism’, Socio-Economic Review 7(1): 7–34. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwn020

- Harrison, E., Jowell, R. and Sibley, E. (2011) ‘Developing indicators of societal Progress’, Ask Research & Methods 20(1): 59–80.

- Heidenreich, M. (ed.) (2014) Krise der europäischen Vergesellschaftung? Soziologische Perspektiven, Wiesbaden: Springer-VS.

- Hello, E., Scheepers, P. and Gijsberts, M. (2002) ‘Education and ethnic prejudice in Europe: explanations for cross-national variances in the educational effect on ethnic prejudice’, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 46(1): 5–24. doi: 10.1080/00313830120115589

- Hjerm, M. (2001) ‘Education, xenophobia and nationalism: A comparative analysis’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27(1): 37–60. doi: 10.1080/13691830124482

- Honneth, A. (1992) Kampf um Anerkennung: Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Hooghe, M., Reeskens, T., Stolle, D. and Trappers, A. (2009) ‘Ethnic Diversity and Generalized Trust in Europe’, Comparative Political Studies 42(2): 198–223. doi: 10.1177/0010414008325286

- Kline, R. B. (2011) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd Edition), New York: Guilford Press.

- Kollmorgen, R. (2009) ‘Postsozialistische Wohlfahrtsregime in Europa. Teil der “drei Welten” oder eigener Typus?’, in B. Pfau-Effinger, S. S. Magdalenic and Ch. Wolf (eds.), International vergleichende Sozialforschung. Ansätze und Messkonzepte unter den Bedingungen der Globalisierung, Wiesbaden: Springer-VS, pp. 65–92.

- Kunovich, R. M. (2004) ‘Social structural position and prejudice: an exploration of cross-national differences in regression slopes’, Social Science Research 33(1): 20–44. doi: 10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00037-1

- Kriesi, H. P. (2007) ‘Sozialkapital. Eine Einführung’, in A. Franzen and M. Freitag (eds.), Sozialkapital. Grundlagen und Anwendungen (Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Sonderheft 47), Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag, pp. 23–46.

- Linden, M. and Thaa, W. (eds.) (2011) Krise und Reform politischer Repräsentation, Baden-Baden, Nomos.

- Mayerl, J. (2016) ‘Environmental concern in cross-national comparison − methodological threats and measurement Equivalence’, in A. Telesiene and M. Groß (eds.), Green European: Environmental Behaviour and Attitudes in Europe in a Historical and Cross-Cultural Comparative Perspective, Routledge: Taylor & Francis, pp. 182–204.

- Manevska, K. and Achterberg, P. (2013) ‘Immigration and perceived ethnic threat: cultural capital and economic explanations’, European Sociological Review 29(3): 437–49. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcr085

- Meeusen, C., de Vroome, T. and Hooghe, M. (2013) ‘How does education have an impact on ethnocentrism? A structural equation analysis of cognitive, occupational status and network mechanisms’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations 37(5): 507–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.07.002

- National Institute of Health (2016) Medical Encyclopedia Medline Plus, Term Malaise, http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003089.htm

- Nyíri, P. (2003) Xenophobia in Hungary: a regional comparison. Systemic sources and possible solutions. CPS Working Paper, http://cps.ceu.edu/publications/working-papers/xenophobia-in-hungary

- Oxford Dictionaries (2018) Definition Malaise, http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/malaise

- Perrineau, P. (2011) The Extreme Right in Europe and Democratic Malaise. Institut Europeu de la Mediterrània, http://www.iemed.org/observatori-en/areesdanalisi/arxius-adjunts/anuari/med.2011/Perrineau_en.pdf

- Pettigrew, T. F., Christ, O., Wagner, U., Meertens, R. W., Van Dick, R. and Zick, A. (2008) ‘Relative deprivation and intergroup prejudice’, Journal of Social Issues 64(2): 385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00567.x

- Putnam, R. D. (2007) ‘E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture’, Scandinavian Political Studies 30(2): 137–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x

- Sagiv, L. and Schwartz, S. H. (1995) ‘Value priorities and readiness for out-group social contact’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(3): 437–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.3.437

- Scherr, A. (2013) ‘Solidarität im postmodernen Kapitalismus’, in L. Billmann and J. Held (eds.), Solidarität in der Krise? Gesellschaftliche, soziale und kulturelle Herausforderungen solidarischer Praxis, Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag, pp. 263–70.

- Schneider, S. L. (2007) ‘Anti-immigrant attitudes in Europe: outgroup size and perceived ethnic threat’, European Sociological Review 24(1): 53–67. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm034

- Semyonov, M., Raijman, R. and Gorodzeisky, A. (2006) ‘The rise of anti-foreigner sentiment in European societies, 1988–2000’, American Sociological Review 71(3): 426–49. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100304

- Semyonov, M., Raijman, R., Tov, A. Y. and Schmidt, P. (2004) ‘Population size, perceived threat, and exclusion: A multiple-indicators analysis of attitudes toward foreigners in Germany’, Social Science Research 33(4): 681–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.003

- Schröder, M. (2013) Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research. A Unified Typology of Capitalism, New York: Palgrave.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992) ‘Universals in the Content and structure of values: theoretical Advances and empirical Tests in 20 Countries’, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 1–65.

- Sidanius, J. and Pratto, F. (1999) Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Steenvoorden, E. (2016) Societal Pessimism. A Study of its Conceptualization, Causes, Correlates and Consequences, Amsterdam: Netherlands Institute for Social research.

- Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., De Vinney, L. C., Star, S. A. and Williams, R. M. J. (1949) Studies in Social Psychology in World War II: The American Soldier. Vol. 1: Adjustment During Army Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sumner, W. G. (1959 [1906]) Folkways. A Study of the Sociological Importance of Usages, Manners, Customs, Mores, and Morals, New York: Dover.

- Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. C. (1979) ‘An Integrative theory of intergroup Conflict’, in W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole, pp. 33–47.

- van der Linden, M., Hooghe, M., de Vroome, T. and Van Laar, C. (2017) ‘Extending trust to immigrants: generalized trust, cross-group friendship and anti-immigrant sentiments in 21 European societies’, PloS one 12(5), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177369.

- Vobruba, G. (2009) Die Gesellschaft der Leute. Kritik und Gestaltung der sozialen Verhältnisse, Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

- Zick, A., Pettigrew, T. F. and Wagner, U. (2008) ‘Ethnic prejudice and discrimination in Europe’, Journal of Social Issues 64(2): 233–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00559.x