ABSTRACT

In the last decade, Europe has been affected by several crises, which had and still have detrimental consequences for the life of many people, suffering from unemployment, poverty and social exclusion. The special issue seeks to explore how these crises have challenged and promoted solidarities within and between European countries. In the introductory paper, first a typology of different types of solidarity – social, political and welfare – is developed to account for the varied meanings and uses of the term. Second, the origins and scopes of the different types of solidarity and their link to crises are discussed. After introducing the special issue papers, five contributions to the understanding of crises and solidarities are highlighted, namely: the meanings of solidarity are varied and discursively contested; different types of solidarity merge and interact; crises are a necessary, but not sufficient condition for solidarity to emerge; crises alter the scope of solidarity; economic shocks can have long-term effects on solidarity. Thus, crises have led to a reconfiguration of solidarities in Europe.

Desiring to deepen the solidarity between their peoples while respecting their history, their culture and their traditions. (Preamble, Maastricht Treaty on the European Union, 1992)

Introduction

Solidarity has been understood as a key element of social integration, interest organization and the provision of collective goods from the earliest days of the discipline (Durkheim Citation1893; Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998; Weber Citation1980 [Citation1922]). In recent years, Europe has faced a series of different crises, creating both, a threat to and an opportunity for solidarity in Europe. From the financial crunch of 2008, and subsequent financial turmoil, culminating in the fiscal crises of many European states, terrorist attacks, to the so called ‘summer of migration’ of 2015, these crises challenge the organization and stability of societies triggering uncertainty and insecurity. In the aftermath of these events, many have started to question the viability of unified EuropeFootnote1 as a social and political project and the very solidarity that has been desired in the Maastricht Treaty on the European Union. In addition, increasing unemployment and poverty, austerity policies, disenchantment with politics and the rise of nationalist political movements are challenging the social bonds within and between nation states in Europe. As a result, old and new social cleavages have become ever more salient (Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde Citation2014). At the same time, the crises have opened up venues for, and helped constitute new modes of solidarity, such as help for refugees, family support, solidarity trade networks, donations to the needy as well as collective protests and strikes. After a period, in which the effect of globalization and individualization on solidarity has been the central focus of much work (Beer and Koster Citation2009; Stjernø Citation2009; Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998), current research has turned to the impact of the numerous and multifaceted crises and their resulting frictions of everyday live (Ellison Citation2011; Koos, Vihalemm and Keller Citation2017; Lahusen and Grasso Citation2018; Laitinen and Pessi Citation2014).

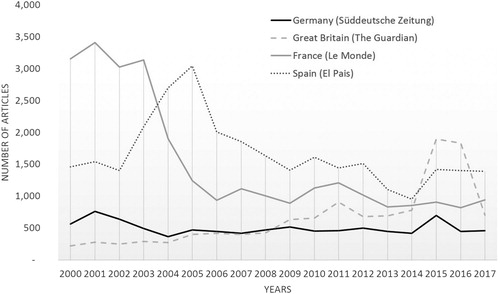

Meanings of solidarity vary extensively, ranging from understandings of some mutual interdependence, feelings of ‘we-ness’ (Durkheim Citation1893), to support for the welfare state (Arts and Gelissen Citation2001), caring for people in need (Fetchenhauer et al. Citation2006) or joint political activism (Snow and Soule Citation2010). While there is some consensus, that solidarity is an indispensable prerequisite for collective interests to be served (Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998), the variety of meanings and related different directions of research complicate a clear synthesis of the scope and origins of solidarity and the impact of crisis on both. Crises, which can be understood as unforeseen events that challenge the organization of daily life and create uncertainty (Kutak Citation1938: 66–67), seem to be inherently linked to solidarity, thus, solidarity barely becomes a salient issue without some major social problem, shock or grievance, which threatens a significant share of group members. Yet, not every social problem or crisis evokes solidarity. A brief analysis of four national newspapers from 2000 to 2017 shows remarkable differences in the frequency solidarity is mentioned in public discourse across countries and over time (see ). Yet, the financial and fiscal crises after 2008 did not result in any major peak of solidarity discourse in either country. In Germany, a reference to solidarity in newspaper articles peaks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US and during the influx of refugees in 2015 and 2016. A similar absence of solidarity discourse during the financial crises years can be found in Spain, even though heavily hit by the financial turmoil. Thus, crises seem to be a necessary, but no sufficient conditions for solidarity discourses to arise. The general question overarching this special issue, is how we can understand the link between crises and solidarity? Have the numerous crises across Europe also led to a surge of solidarity?

In the research on solidarity, two central issues stand out that are of special interest in understanding the link between crises and solidarities: the origin and the scope of solidarity. A variety of theories emphasize different roots or explanations for solidarity, ranging from social norms, long-term self-interest, personality, ritual chains, to situational, cultural and institutional aspects (Bierhoff Citation2002; Esping-Andersen Citation1990; Healy Citation2006; Hechter Citation1987; Lindenberg Citation2006; Ruiter and De Graaf Citation2006; Salamon and Anheier Citation1998; Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998; Wilson and Musick Citation1997). While different theories might explain different aspects or relate to different meanings of solidarity, here we are specifically interested in how different individual and contextual social, economic and cultural conditions provide ground for the emergence of solidarity in the face of external shocks. The second key issue is to whom solidarity relates, i.e. its scope. Solidarity produces and reproduces boundaries between members and non-members of a group and thus is a crucial mechanism of both inclusion and exclusion along with attributes, such as class, ethnicity, or nation. As membership in more particular groups seems to outrank more universal forms of belonging (Calhoun Citation2002), exclusion commonly becomes an integral part of solidarity. Thus, on its flip side, solidarity can advance a process of closure to outsiders (Weber Citation1980 [Citation1922]). The economic crisis, growing social inequality and the recent ‘migration crisis’ have the potential to shift the salience of group boundaries and hence the scope of solidarity. Both, the recent rise of populist national movements across Europe and, quite contrary, the immense wave of solidarity with refugees might serve as examples of such reconfigurations. Thus, how do crises affect the scope of solidarity?

In the following, I first discuss the varied meanings of solidarity in the existing literature and suggest a typology, distinguishing between social, political and welfare solidarity. More specifically, I argue that distinguishing between different types of solidarity will increase the analytical leverage of the concept. Next, I discuss conditions for solidarity and how crises potentially affect those conditions. After introducing the contributions of the special issue, five main contributions to the understanding of solidarities and its link to crises are discussed: first, the meanings of solidarity are varied and discursively contested; second, different (ideal-)types of solidarity mix and interact; third, crises are a necessary, but not sufficient condition for solidarity to emerge; fourth, crises have the power to change the scope of solidarity; and finally, economic shocks can have long-term effects on solidarity. Crises have thus contributed to a reconfiguration of solidarities in Europe.

What is solidarity?

Solidarity has been a central and often contested concept (Bauman Citation1999; Beck Citation1994; Stjernø Citation2009). Ever since Durkheim’s (Citation1893) classical distinction between mechanic and organic solidarity, which sets apart premodern from modern forms of integration, the meaning, conceptual usage and empirical manifestations of solidarity have been debated. According to Durkheim, mechanic solidarity refers to the fundamental bonds between members of a group or community based on similarity. Accordingly, some authors understand solidarity as an emotional tie of an individual to a specific group, a feeling of belonging and obligation (Blumer Citation1939; Melucci Citation1988). Others refer to a common identity as well as shared values and beliefs, rendering solidarity part of the overall cultural system of society (Alexander Citation2014; Bayertz Citation1999; Durkheim Citation1893). In contrast, organic solidarity refers to some mutual interdependence among the members of a group (Durkheim Citation1893). For Weber (Citation1980 [Citation1922]), solidarity signifies a specific type of relationship that is oriented towards some collective interest and differs from other forms, like atomistic market exchange or hierarchical domination. In this understanding, solidarity entails some type of action, which can be altruistic, reciprocal or collective. In short, acts that are beneficial to a group of which the individual is a member (Beer and Koster Citation2009; Fetchenhauer et al. Citation2006; Smith and Sorrell Citation2014).

Moreover, the meaning of solidarity varies by research field, relating to such different phenomena as collective political activism, charitable deeds, support for the welfare state, or simply group membership (Arts and Gelissen Citation2001; Fetchenhauer et al. Citation2006; Melucci Citation1988; Stjernø Citation2009). Acknowledging the varied meanings, Bayertz (Citation1999) and Scholz (Citation2008) distinguish between four different uses of the concept: universal solidarity of humankind, social solidarity as a cohesive force, political solidarity as jointly approaching common goals, and civic solidarity as private caring and welfare state support. These types differ in the degree to which they draw group boundaries – universal versus particularistic – in the manifestations of solidarity – either as sentiment, interest or action – and in their foundation, either based on common fate and shared belonging, or collective interest and shared utility (Hechter Citation1987; Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998).

In sum, despite useful attempts to systematize and integrate different concepts of solidarity (Bayertz Citation1999; Beer and Koster Citation2009; Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998), its usage and meaning remain diverse. To capture the variety of solidarities I suggest a typology to better determine its conceptual usage. Building on the above discussion and the existing research in sociology and political science, I distinguish between three types of solidarities, which are social solidarity, political solidarity and welfare solidarity. Rather than treating universal solidarity as a separate type, like Bayertz (Citation1999), I suggest that that the scope of solidarity (i.e. the size and constitution of the group) can vary from more particular to universal for all three types of solidarity.Footnote2 Moreover, the level of institutionalization of each type of solidarity can vary from informal, ad-hoc and voluntary manifestations, such as giving money to a homeless person on the streets, to organized, regular and obligatory forms, such as contributions to the welfare system. Nevertheless, the three types of solidarity are different in a number of dimensions, such as their manifestations, their inherent logic, institutional forms and the conditions of their emergence (see ). The manifestations refer to different types of actions (e.g. protest participation) as well as the attitudes and feelings towards these actions (e.g. attitudes about protest). By logic, I refer to the aim or outcome of a specific form of solidarity within a larger collectivity or system, such as social integration. Related to this, the three ideal types can also be distinguished according to the value sphere or system (Lepsius Citation2017; Weber Citation1980 [Citation1922]) in which they are prevalent, such as the political system. Finally, different theoretical traditions have suggested different explanations for the three types of solidarity (discussed in the next section).

Table 1. A typology of different types of solidarity.

Social solidarity can be understood as a social relationship that manifests itself in informal or formal group membership, institutionalized in the social system. The level of institutionalization ranges from informal, such as mutual knowledge and acknowledgement, to formal, as for instance manifested in a national passport. Social solidarity can either be based on rational calculus or shared fate, leading to some form of integration, such as ‘Vergemeinschaftung’ or ‘Vergesellschaftung’ (Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998; Weber Citation1980 [Citation1922]). The scope of social solidarity varies from kinship ties, such as family or clan, to beliefs about we-ness grounded in shared values, beliefs or identities, such as a nation or world society. Social solidarity is arguably the most basic form on which all other types of solidarity depend, since group membership delineates the scope of both political and welfare solidarity. Political solidarity manifests itself in collective action for interest representation, mostly within the political system. Thus, it can be highly organized, such as in union membership (Ebbinghaus, Göbel and Koos Citation2011), or spontaneous, such as in political consumption (e.g. boycotts) (Koos Citation2012). Political solidarity ultimately serves to articulate interest, by traditional or individualized collective action (Micheletti Citation2003), from local grassroots groups to organized transnational interest groups. Finally, welfare solidarity relates to all ways in which people provide tangible and intangible support for each other, either highly institutionalized as in the case of a welfare state, or private and informal, as in helping family and friends. In provisioning for people, the scope of who can be a recipient can range from local to transnational relationships. Yet, the availability of resources conditions the size of the group and thus the scope for which one can provide.

The different types of solidarity overlap and interact in manifold ways, where for instance a common identity can be a prerequisite for collective action. The most basic communality between these different forms is that they all reflect ‘a state of relations between individuals and groups enabling collective interest to be served’ (Van Oorschot and Komter Citation1998: 11). Arguably, the different types of collective interest, or logics, compose the most important aspect that distinguishes the three forms of solidarity.

Crisis and conditions for solidarity

What are the conditions under which the different collective interests are being served and how do crises affect the emergence of solidarity? The three different types of solidarity, while sharing some common conceptual roots, are characteristic of different research fields and differ by the theoretical approaches used to explain the emergence of a specific type of solidarity. While social solidarity is mainly discussed in social theory and research focusing on group boundaries, political solidarity is analyzed in political sociology and social movement studies. Finally, welfare solidarity is studied both in research on welfare states and on philanthropy. The degree to which the different fields study and acknowledge the impact of crises on solidarity varies. Before discussing the different existing explanations for solidarity, I briefly elaborate on the concept of crisis itself.

According to a classical definition, a crisis can be understood as some sudden unforeseen event that challenges the organization of a larger social group, thereby threatening everyday routines and inducing uncertainty and at times fear (Kutak Citation1938: 66–67). Such external shocks are not uniform, but differ in the degree to which they are man-made, their temporal and geographical stretch and predictability (Koos, Vihalemm and Keller Citation2017). The different types of crises might themselves provide some explanation for whether solidarity emerges or not. Thus, whether the crisis is man-made or natural might affect the deservingness perception of a group. A recent study by Genschel and Hemerijck (Citation2018) across 11 European countries indeed shows that across all countries respondents are most likely to support financial measures for countries that have been hit by a natural disaster, and least likely to help in case of fiscal debt burdens. Yet, what are common explanations of either type of solidarity and how do they relate to crisis?

The classical contributions by Durkheim, Weber and Parsons are concerned with social solidarity and the integration of society. They propose different solutions to the fundamental question of how ‘society is possible’. According to Durkheim, either a collectivity is established by certain group commonalities, such as shared values and beliefs or by an understanding of mutual interdependence. Weber (Citation1980 [Citation1922]) distinguishes between a communal and an associative type of relationship, which can be viewed as two distinct types of solidary relationships, either based on affective, traditional or on rational grounds. For Parsons ([Citation1951]Citation2013) solidarity is rooted in social norms, as the enforceable expectations for any member of a group to fulfill certain obligations towards the collectivity. A different literature, based in Sociology and Social Psychology, focuses on group membership itself, asking how group boundaries and thus group membership are established (Lamont and Molnár Citation2002). Research in this field seeks to understand the variability of belonging and the conditions for group membership. Basically, groups tend to form their identity through comparisons with out-groups, striving for a positive self-perception (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986). Distinctions are based on symbolic and social boundaries that are constructed around shared classifications and become especially rigid, when they overlap with resource distributions and thus social boundaries (Lamont and Molnár Citation2002). This in turn shapes group formation, along the lines of social class, ethnicity or nation. The social closure towards others and the construction of we-ness is the subject of much empirical research on outgroup sentiment. This research finds, that the scope of solidarity and the boundaries of a group seem especially exclusive, if people feel threatened by an outgroup (Blalock Citation1967; Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky Citation2008) and if there is little interaction with the outgroup (Allport Citation1954; Schneider Citation2007). Economic competition between different groups can be important in reinforcing group boundaries (Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet Citation2009). For instance, Kuntz et al. (Citation2017) find an increase of anti-immigrant attitudes after the economic situation of many European countries has worsened due to the economic crisis in 2008.

Political solidarity and thus collective action to reach shared goals is widely discussed in political sociology and social movements studies. Going back to the seminal study by Olson ([Citation1965] Citation2009), collective action is unlikely to emerge, if people that do not contribute to a collective good our outcome, cannot be excluded from its consumption or usage, specifically if groups are large. Ever since, the study of collective action, both within and outside of institutional arrangements, has become a large field of research (see for an overview: Snow, Soule and Kriesi Citation2008). While it is outside of the scope of this paper to review the field, three key theoretical approaches can be identified: political opportunities, mobilizing structures and framing (McAdam, McCarthy and Zald Citation1996: 3). Political opportunities are dimensions of the political environment, such as state repression or elite allies, which provide the context for mobilization (Meyer Citation2004). Mobilizing structures are existing informal and formal networks, such as neighborhood ties or non-profit organizations, which facilitate the mobilization of actors (McAdam, McCarthy and Zald Citation1996). Those networks are specifically akin to some form of social solidarity, as a precondition for collective action (Melucci Citation1988). Finally, framing refers to the deliberate attempts of meaning making by activists, thus the definition of a situation as a problem, the identification of its causes and the suggestion of potential solutions (Benford and Snow Citation2000). Older approaches also focused on grievances, strains or crises, but these have not received much attention until recently (Snow and Soule Citation2010). These latter approaches seem specifically pertinent in explaining and understanding the impact of crises on collective action (Kriesi Citation2012) and have again entered the debate on political contention in Europe (Giugni and Grasso Citation2016). Kern, Marien and Hooghe (Citation2015), for instance, show how rising unemployment triggered protest in Europe during the great recession. Moreover, Frangi, Koos and Hadziabdic (Citation2017) find that social support and solidarity with trade unions increases as a consequence of the crisis.

Finally, two different lines of literature deal with welfare solidarity, one focusing on the welfare state and the other studying private philanthropy and care giving. Research on the welfare state focuses on the acceptance and social support for government redistribution, and social policies that address individual hardship and risk (Sachweh Citation2016). Solidarity here is understood as positive attitudes towards social policies that enhance redistribution and improve life chances (Svallfors Citation2010). The roots of social solidarity thus conceived are either understood as based on (immediate or long-term) self-interest (Jæger Citation2006) or on some beliefs about the appropriateness of the welfare state, either rooted in (welfare regime specific) socialization (Svallfors Citation1997) or in a shared moral economy (Koos and Sachweh Citation2017; Mau Citation2004). Recent research has started to analyze how changing macro-economic conditions shape welfare solidarity. Most studies find that economic strain increases support for welfare solidarity (Blekesaune Citation2013; Naumann, Buss and Bähr Citation2016). However, Sachweh (Citation2018) shows that, while the perceived impact of the financial crisis increases support for redistribution, this varies across social classes and is moderated by social spending.

In the field on philanthropy and pro-social behavior, a multitude of perspectives exists. Early anthropological approaches focus on the underlying obligation of reciprocity in providing a gift and how this shapes solidary relationships (Mauss [Citation1925] Citation2002). Sahlins (Citation1972), distinguishing different types of reciprocity, points to the importance of generalized reciprocity, which does not require a direct return of a gift, but is understood as mutual responsibility to help if the need arises. Such caring for people in need has been explained by different approaches that either emphasize individual characteristics of actors, such as an altruistic personality, material resources, personal networks (Bekkers and Wiepking Citation2011) or the impact of institutional welfare state or non-profit sector arrangements (Salamon and Anheier Citation1998). Research on the impact of crisis remains scarce. Surprisingly little research has addressed how different crises trigger philanthropy.

Contributions in the special issue

The papers assembled in this special issue make several contributions to explain solidarity more generally and to understand the impact of crisis on solidarity more specifically. I discuss the papers along the lines of the different types of solidarity they address, the kind of crisis and respective conditions for the emergence of solidarity.

In their paper on symbolic struggles over solidarity Hofmann et al. (Citation2019) compare the different use, meaning and scope of social and welfare solidarity by three different collective actors in Austria during the recent crises years. They examine the far right Party FPÖ, the Austrian Trade Union Federation (ÖGB) and civil society organizations (e.g. Red Cross) active in refugee support, in a comparative case study design. Based on interviews and documents the authors analyze how the collective actors differently construe the foundation (e.g. self-interest versus universal commonality), objectives (such as common interest or belonging) and inclusiveness (i.e. scope) of solidarity. They find that all organizations differ strongly in how boundaries of solidarity are drawn, where the far right party and civil society form the two antipodes of narrow exclusive versus universal inclusive solidarity. The trade union takes a middle ground, with an ambivalent stance, oscillating between the representation of the core male workforce and the representation of labor market outsiders, such as the unemployed or migrant workers. Similar patterns also emerge in a second analysis, which traces the dynamic nature of the struggle over solidarity linked to the debate about two specific policies (needs-based minimum benefits and labor market access for refugees). Hence, the construction of group identity, and thus social solidarity, provides an important basis for welfare solidarity. The ‘migration crisis’ has intensified symbolic struggles over the very meaning and scope of solidarity and spurred its strategic usage as a ‘battle-term’ to promote fundamentally different policies. Thus, taking Austria as an example of developments in Europe at large, Hofmann et al. (Citation2019) show, that the foundations and the inclusiveness of solidarity are highly contentious and variable. The resulting question then is, under which conditions a universal or particularistic understanding of social solidarity arises.

Aschauer and Mayerl (Citation2019) provide some answers to this question studying the impact of ‘societal malaise’ on ethnocentrism or exclusive social solidarity across Europe. Societal malaise can be understood as a complex configuration of discontent with the state of society or perception of fundamental crisis. The authors argue that societal malaise is an important moderating factor in the relationship between individual, socio-demographic as well as structural factors and ethnocentrism or exclusive solidarity. Yet the effect of societal malaise is expected to vary with different welfare arrangements. Using survey data from 21 EU countries, Aschauer and Mayerl (Citation2019) first show, that the perception of crisis decreases from the Southern and Eastern European countries to the Northern European countries. Next, using multi-group structural equation models the authors illustrate how societal malaise has a strong effect on exclusive social solidarity mediating the effect of structural, individual and socio-demographic determinants. Thus, the authors show that an encompassing perception of societal malaise indeed affects the scope of solidarity. Crises and their resulting fundamental social discontent lead to a more restrictive ethnocentric social solidarity. Adding a comparative perspective, the moderating effect varies by welfare country cluster. In sum, while Hofmann et al. (Citation2019) highlight the discursive struggle over solidarity in times of crises, Aschauer and Mayerl (Citation2019) find the deteriorating effect of societal malaise on the scope of social solidarity.

Koos and Seibel (Citation2019) analyze the impact of the so called ‘refugee crisis’ on solidarity with forced migrants from a comparative European perspective. Specifically, the authors study the public support for the notion that a country should help refugees, denoting a universal form of welfare solidarity, which transcends the in-group to include distant others. On a theoretical level, Koos and Seibel borrow from the literature on outgroup sentiment and focuses on economic threat, inter-group contact and political framing theories to explain solidarity with refugees. In addition, the authors develop a welfare state argument, suggesting that more extensive welfare states render solidarity with refugees more likely, since they provide an economic buffer, convey a logic of ‘inclusion’ and decrease the importance of deservingness. Based on a 2016 Eurobarometer survey across 28 countries, the authors first show strong variation in support for refugees ranging from 23% in the Czech Republic to 93% in Sweden. Using a multilevel regression approach they find that the historical share of migrants in a country and the extensiveness of the welfare arrangements best explain country differences, lending some support to the inter-group contact theory and the welfare state argument. Neither size of the refugee influx, nor the countries’ economic conditions or the strength of right wing political parties has a statistical significant effect on solidarity with refugees across countries. Paradoxically, on the level of individual respondents, negative subjective perceptions of the own or their countries economic situation decrease outgroup solidarity. In contrast to Aschauer and Mayerl, Koos and Seibel (Citation2019) thus find that, under certain conditions, a crisis can also increase the scope of solidarity.

Graziano and Forno (Citation2019) in their study of sustainable community movement organizations (SCMOs) and political consumerism in Italy focus on how political and welfare solidarity are locally established in times of crisis. SCMOs can be understood as a form of collective activism that tries to build alternative and sustainable networks of production, exchange and consumption (Forno and Graziano Citation2014). While the emergence of traditional cooperatives was linked to the hardship brought about by industrialization, new sustainable community movement organizations are linked to the multifold crisis of modernity, such as increasing social inequality, precarization and environmental degradation. In establishing and enacting SCMOs three different forms of solidarity can be distinguished: internal solidarity within producer-consumer networks, external solidarity towards outside actors (such as international fair-trade organizations) and solidarity towards the natural environment. The authors use a case study design to analyze the role of grievances and solidarity comparing three SCMOs in Italy, drawing on a rich set of expert-interviews, documents and survey data. Specifically, they analyze solidarity in Solidarity Purchasing Groups (SPGs), an anti-mafia political consumerism initiative (Addiopizzo) aiming to reward shopkeepers and producers that refuse paying ‘protection money’ (pizzo) and the case of a worker recovered factory (Rimaflow). Each organization or network has been founded in the context of a specific crisis or grievance (environmental degradation and social inequality, organized criminal threat, and economic hardship during the financial crisis) and aims to provide an opportunity to re-create social bonds and initiate change towards the common good. Building new social ties, supporting local producers and thus establishing solidary relationships, in lieu of market relationships is at the center of the SCMOs. The networks are created and sustained by some form of collective action that tries to promote social change. Yet at the same time, they ensure the welfare of the people in the network, promoting consumer citizenship. In sum, Graziano and Forno (Citation2019) show how crises can provide the backdrop for the creative development of solidary relationships, mixing political and welfare solidarity to establish collective goods.

In a related perspective, Gómez Garrido, Carbonero and Viladrich (Citation2019) study the emergence of political and welfare solidarity with vulnerable people after the financial crisis in Spain focusing on grassroots food banks. Similar to Italy, Spain has suffered heavily from the financial crunch of 2008. Unemployment, specifically among the young, rose drastically and the number of working poor skyrocketed. In the resulting dire situation, food banks have become a last resort for the most deprived. Yet, the existing ‘traditional’ system of food banks is rather problematic. In the stigmatizing system receiving goods is conditional on a means tested referral by a social worker, as well as both, on the legal status and resident permit of the recipient. Rooted in the indignados or 15M movement (named after its foundational date on May 15, 2011), activists were seeking to develop a different way of providing for vulnerable people that promotes social inclusion, empowerment and political awareness. Based on a case study of such grassroots food banks in low and middle-income neighborhoods in Madrid, the authors study how solidarity is constructed. The grassroots food banks were developed to overcome the stigmatizing passive and dependent role of the poor and empower and activate people, while at the same time creating communal relationships and a sense of ‘we-ness’. In grass roots food banks receiving help is also not unconditional, but rather than relying on legal and economic attributes it is based on need and active participation. The authors show how grassroots movements can create solidarity as a reaction to crisis, providing emancipatory grounds for establishing full membership in a community and thus enabling political and welfare solidarity. Similar to the findings by Graziano and Forno (Citation2019) the rationale of providing for people in need is linked to collective action, which seeks to change objectionable institutional structures.

Finally, Meuleman (Citation2019) studies the long-term effects of economic contexts on welfare solidarity in Britain and the United States. Welfare solidarity in his study is understood as the normative support for income redistribution by the government, thus a highly institutionalized form of solidarity. The vast literature on attitudes towards the welfare state and redistribution has thus far neglected the economic conditions in the formative adolescent years. Thus, experiences of economic inequality during the time in which people first develop their political preferences might have a decisive long-term impact upon their general stance towards state intervention, independent of the immediate personal situation and national economic context. Using two repeated cross-sectional surveys for the US and Britain, starting in 1978 and 1986, he distinguishes age, period and cohort effects in the attitudes towards redistribution. Controlling for individual effects, such as age, gender and social class, as well as contextual effects, such as economic inequality and economic growth, economic inequality of the formative years has a statistically significant effect on attitudes towards redistribution. Interestingly though, the effect differs between the two countries. In the US, birth cohorts that grew up during a time of higher inequality show higher support for redistribution, while in Britain the reverse effect can be found. The results show that adverse economic conditions during socialization can indeed shape welfare solidarity over the life course, thus, the effects of economic shocks on institutionalized welfare solidarity might be ‘sticky’.

Conclusion and future research

Even though solidarity has always been of interest to sociology, the study of solidarity has received growing attention in recent years. While at the turn of the century, much research has focused on the impact of globalization and individualization on solidarity, in the recent decade, this focus has shifted to capture the impact of crises on solidarity, specifically in Europe. In this special issue, we seek to contribute to the understanding of the link between crises and solidarities and develop a better understanding of the origins, scope and variations of solidarity. Specifically, five contributions to the understanding of solidarity and its relationship to the crisis can be highlighted: Firstly, rather than talking about solidarity as such, it might be more useful to distinguish different types of solidarity. Acknowledging the varieties of solidarity would help to sharpen our understanding of different origins and preconditions of solidarity. Moreover, comparing and synthesizing the different theoretical approaches to the understanding and explanation of the different types of solidarity might be cross-fertilizing. Secondly, solidarity is a contested concept, whose meaning is variable, interwoven with specific interests and strategically utilized to advance political agendas (Hofmann et al., Citation2019). In social life, the three ideal types of solidarity distinguished here, are often connected and linked in solidarity projects and organizations, as nicely illustrated by Graziano and Forno (Citation2019) as well as Gómez Garrido, Carbonero and Viladrich (Citation2019). Thirdly, crises seem to be necessary, but not sufficient conditions for solidarity to emerge. Therefore, it is important to understand under which conditions crises give rise to solidarity. Genschel and Hemerijck (Citation2018) suggest that the type of crisis and the ensuing deservingness perceptions could be crucial in this respect. Fourthly, crises affect the scope of solidarity. Thus, as Aschauer and Mayerl (Citation2019) have shown societal malaise leads to more exclusionary group boundaries. More generally, the perception of some societal malaise moderates the effect of socio-economic conditions for exclusionary solidarity. Yet, as Koos and Seibel (Citation2019) show, under certain conditions, humanitarian crises can also broaden the scope of solidarity to include out-groups such as refugees. Finally, the effects of crises seem to be sticky. Thus growing up in turbulent times might shape attitudes and behavior to a larger extent than previously acknowledged (Meuleman Citation2019).

Summing up, crises arguably generate some impetus and space for solidarity projects, which foster welfare and collective action to advocate for social change. Yet, the scope of such initiatives seems often rather local, even though not necessarily exclusive. At the same time, economic crises and societal ‘ills’ more generally endanger the scope of universal social solidarity, corroborating Calhoun’s (Citation2002) argument that more particularistic group membership seems to outrank more universal forms of belonging. Populist parties seem to use crises to strategically advocate exclusive group boundaries and respective particularistic social policies. In short, crises can trigger political and welfare solidarity, but it seems, at the same time, crises also frequently limit the scope of social solidarity and therefore undermine the very basis of European welfare and political solidarity.

Certain limitations in the study of crises and solidarities remain, that need to be addressed in future research. First, more studies need to engage in a comparative perspective on solidarity and highlight national varieties, while also addressing the origin, scope and limits of transnational solidarity (but see Gerhards and Lengfeld Citation2015; Gerhards et al. Citation2018). Secondly, future studies need to improve our understanding of the role of populist movements and parties in defining and changing the scope of social solidarity and its consequences for welfare and political solidarity. Thirdly, the lasting influence of crises on social, political and welfare solidarity deserves attention. Finally, digitalization has a crucial impact on the lives and connectedness of people. Yet, how digitalization affects solidarity is largely unclear. Social movement studies show that social media can have important effects on the organization and success of collective action (Shirky Citation2011), but how this relates to group boundaries, feelings of belonging, as well as welfare solidarity remains largely unclear.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michalis Lianos and Agnes Skamballis for their major support in editing this special issue. Furthermore, thanks to all the authors and reviewers for their work and input. At different stages of this project, Patrick Sachweh and Antje Vetterlein have provided invaluable comments. The idea for this special issue arose at a research stay at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, whose support and inspiring environment I would like to acknowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Sebastian Koos is an assistant professor of corporate social responsibility at the University of Konstanz. He works on corporate social responsibility, political consumerism, industrial relations, solidarity and pro-social behavior. His research has been published in two books and multiple journals, such as Acta Sociologica, British Journal of Industrial Relations, Policy and Society or Socio-Economic Review.

ORCID

Sebastian Koos http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6739-1649

Notes

1 While the Treaty obviously is limited to the member countries of the European Union, non-members, like Switzerland or Norway arguably are also part of a more integrated Europe, formally manifested in legal agreements.

2 Yet, since the early nineteenth century the nation state seems to be the dominant frame of reference for the scope of solidarity (Beckert et al. Citation2004).

References

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. (2014) ‘Morality as a cultural system: on solidarity civil and Uncivil’, in The Palgrave Handbook of Altruism, Morality, and Social Solidarity, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 303–10.

- Allport, G. W. (1954) The Nature of Prejudice, Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Arts, W. and Gelissen, J. (2001) ‘Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: does the type really matter?’, Acta Sociologica 44(4): 283–99. doi: 10.1177/000169930104400401

- Aschauer, W. and Mayerl, J. (2019) ‘The dynamics of perceived ethnic threat in Europe. A comparison of enduring and emerging determinants of solidarity towards immigrants’, European Societies 21(5): 672–703.

- Bauman, Z. (1999) In Search of Politics, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bayertz, Kurt. (1999) ‘Four uses of “solidarity”’, in Solidarity, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 3–28.

- Beck, Ulrich. (1994) ‘The reinvention of politics: towards a theory of reflexive modernisation’, in U. Beck, A. Giddens and S. Lash (eds.), Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 1–55.

- Beckert, J., Eckert, J., Kohli, M. and Streeck, W. (2004) Transnationale Solidarität: Chancen und Grenzen, Frankfurt a. M.: Campus Verlag.

- Beer, P. d. and Koster, F. (2009) Sticking Together or Falling Apart? Solidarity in an Era of Individualization and Globalization, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Bekkers, R. and Wiepking, P. (2011) ‘A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 40(5): 924–73. doi: 10.1177/0899764010380927

- Benford, R. D. and Snow, D. A. (2000) ‘Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assesment’, Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bierhoff, H.-W. (2002) Prosocial Behaviour, New York: Taylor and Francis.

- Blalock, H. M. (1967) Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Blekesaune, M. (2013) ‘Economic strain and public support for redistribution: a comparative analysis of 28 European Countries’, Journal of Social Policy 42(1): 57–72. doi: 10.1017/S0047279412000748

- Blumer, Herbert. (1939) ‘Collective Behaviour’, in R. E. Park (ed.), An outline of the principles of sociology. New York: Barnes & Noble, pp. 221–80.

- Calhoun, C. J. (2002) ‘Imagining solidarity: cosmopolitanism, constitutional patriotism, and the public sphere’, Public Culture 14(1): 147–71. doi: 10.1215/08992363-14-1-147

- Durkheim, E. (1893) De La Division Du Travail Social, Paris: Puf 1930.

- Ebbinghaus, B., Göbel, C. and Koos, S. (2011) ‘Social capital, ‘ghent’ and workplace contexts matter: comparing union membership in Europe’, European Journal of Industrial Relations 17(2): 107–24. doi: 10.1177/0959680111400894

- Ellison, M. (2011) Reinventing Social Solidarity Across Europe, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Oxford: Polity Press.

- Fetchenhauer, D., Buunk, B., Flache, A., Buunk, A. P. and Lindenberg, S. (2006) Solidarity and Prosocial Behavior: An Integration of Sociological and Psychological Perspectives, New York: Springer.

- Forno, F. and Graziano, P. R. (2014) ‘Sustainable community movement organisations’, Journal of Consumer Culture 14(2): 139–57. doi: 10.1177/1469540514526225

- Frangi, L., Koos, S. and Hadziabdic, S. (2017) ‘In unions we trust! Analysing confidence in unions across Europe’, British Journal of Industrial Relations 55(4): 831–58. doi: 10.1111/bjir.12248

- Genschel, P. and Hemerijck, A. (2018) ‘Solidarity in Europe’, EUI Policy Brief 2018(1): 1–8.

- Gerhards, J. and Lengfeld, H. (2015) European Citizenship and Social Integration in the European Union, London/New York: Routledge.

- Gerhards, J., Lengfeld, H., Ignácz, Z. S., Kley, F. K. and Priem, M. (2018) ‘How strong is European solidarity?’, Berlin Studies on the Sociology of Europe 37: 1–34.

- Giugni, M. and Grasso, M. T. (2016) Austerity and Protest: Popular Contention in Times of Economic Crisis, London/New York: Routledge.

- Gómez Garrido, M., Carbonero, M. A. and Viladrich, A. (2019) ‘The role of grassroots food banks in Building political solidarity with vulnerable People’, European Societies 21(5): 753–73.

- Graziano, P. and Forno, F. (2019) ‘From global to glocal. Sustainable community movement organisations (SCMOs) in times of crisis’, European Societies 21(5): 729–52.

- Healy, K. (2006) Last Best Gifts: Altruism and the Market for Human Blood and Organs, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hechter, M. (1987) Principles of Group Solidarity, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hofmann, J., Altreiter, C., Flecker, J., Schindler, S. and Simsa, R. (2019) ‘Symbolic struggles over solidarity in times of crisis: trade unions, civil society actors and the political far right in Austria', European Societies 21(5): 649–71.

- Jæger, M. M. (2006) ‘Welfare regimes and attitudes towards redistribution: the regime hypothesis revisited’, European Sociological Review 22(2): 157–70. doi: 10.1093/esr/jci049

- Kern, A., Marien, S. and Hooghe, M. (2015) ‘Economic crisis and levels of political participation in Europe (2002–2010): the role of resources and grievances’, West European Politics 38(3): 465–90. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.993152

- Koos, S. (2012) ‘What drives political consumption in Europe? A multi-level analysis on individual characteristics, opportunity structures and globalization’, Acta Sociologica 55(1): 37–57. doi: 10.1177/0001699311431594

- Koos, S. and Sachweh, P. (2017) ‘The moral economies of market societies: popular attitudes towards market competition, redistribution and reciprocity in comparative perspective’, Socio-Economic Review 1–29. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwx045

- Koos, S. and Seibel, V. (2019) ‘Solidarity with refugees across Europe. A comparative analysis of public support for helping forced migrants’, European Societies 21(5): 704–28.

- Koos, S., Vihalemm, T. and Keller, M. (2017) ‘Coping with crises: consumption and social resilience on markets’, International Journal of Consumer Studies 41(4): 363–70. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12374

- Kriesi, H. (2012) ‘The political consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe: electoral punishment and popular protest’, Swiss Political Science Review 18(4): 518–22. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12006

- Kuntz, A., Davidov, E. and Semyonov, M. (2017) ‘The dynamic relations between economic conditions and anti-immigrant sentiment: a natural experiment in times of the European economic crisis’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58(5): 392–415. doi: 10.1177/0020715217690434

- Kutak, R. I. (1938) ‘The sociology of crises: the Louisville Flood of 1937’, Social Forces 17(1): 66–72. doi: 10.2307/2571151

- Lahusen, C. and Grasso, M. T. (2018) Solidarity in Europe, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Laitinen, A. and Pessi, A. B. (2014) ‘Solidarity: theory and practice. An introduction’, Solidarity: Theory and Practice 1–29.

- Lamont, M. and Molnár, V. (2002) ‘The study of boundaries in the social Sciences’, Annual Review of Sociology 28(1): 167–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107

- Lepsius, M. Rainer. (2017) ‘Interests and ideas. Max Weber’s allocation problem’, in C. Wendt (ed.), Max Weber and Institutional Theory, Cham: Springer, pp. 23–34.

- Lindenberg, Siegwart. (2006) ‘Prosocial behavior, solidarity, and framing Processes’, in Solidarity and Prosocial Behavior, New York: Springer, pp. 23–44.

- Mau, S. (2004) The Moral Economy of Welfare States: Britain and Germany Compared, London/New York: Routledge.

- Mauss, M. ([1925] 2002) The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London: Routledge.

- McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D. and Zald, M. N. (1996) Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements. Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures and Cultural Framing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Melucci, A. (1988) ‘Getting Involved: identity and mobilization in social Movements’, International Social Movement Research 1(26): 329–48.

- Meuleman, Bart. (2019) ‘The economic context of solidarity. period vs. cohort differences in support for income redistribution in Britain and the United States.' European Societies 21(5): 774–801.

- Meuleman, B., Davidov, E. and Billiet, J. (2009) ‘Changing attitudes toward Immigration in Europe, 2002–2007: a dynamic group conflict theory approach’, Social Science Research 38(2): 352–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.09.006

- Meyer, D. S. (2004) ‘Protest and political opportunities’, Annual Review of Sociology 30: 125–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110545

- Micheletti, M. (2003) Political Virtue and Shopping. Individuals, Consumerism, and Collective Action, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Naumann, E., Buss, C. and Bähr, J. (2016) ‘How unemployment experience affects support for the welfare state: a real panel approach’, European Sociological Review 32(1): 81–92. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv094

- Olson, M. ([1965] 2009) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Parsons, Talcott. ([1951] 2013) The Social System, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ruiter, S. and De Graaf, N. D. (2006) ‘National context, Religiosity, and Volunteering: results from 53 Countries’, American Sociological Review 71: 191–210. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100202

- Sachweh, P. 2016. ‘Social Justice and the welfare state: institutions, outcomes, and attitudes in comparative Perspective’, in Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research, New York: Springer, pp. 293–313.

- Sachweh, P. (2018) ‘Conditional solidarity: social class, experiences of the economic crisis, and welfare attitudes in Europe’, Social Indicators Research 139(1): 47–76. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1705-2

- Sahlins, M. D. (1972) Stone Age Economics, New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Salamon, L. M. and Anheier, H. K. 1998. ‘Social origins of civil society: explaining the nonprofit sector cross-Nationally’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 9(3): 213–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1022058200985

- Schneider, S. L. (2007) ‘Anti-Immigrant attitudes in Europe: outgroup size and perceived ethnic threat’, European Sociological Review 24(1): 53–67. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm034

- Scholz, S. J. (2008) Political Solidarity, University Park: Penn State Press.

- Semyonov, M., Raijman, R. and Gorodzeisky, A. (2008) ‘Foreigners’ impact on European societies: public views and perceptions in a cross-national comparative perspective’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49(1): 5–29. doi: 10.1177/0020715207088585

- Shirky, C. (2011) ‘The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere, and political change’, Foreign Affairs 90(1): 28–41.

- Smith, C. and Sorrell, K. (2014) ‘On social solidarity’, in The Palgrave handbook of altruism, morality, and social solidarity, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 219–47.

- Snow, D. A. and Soule, S. A. (2010) A primer on social movements, New York: WW Norton.

- Snow, D. A., Soule, S. A. and Kriesi, H. (2008) The Blackwell companion to social movements, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Stjernø, S. (2009) Solidarity in Europe: the history of an idea, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Svallfors, S. (1997) ‘Worlds of welfare and attitudes to redistribution: a comparison of eight western nations’, European Sociological Review 13(3): 283–304. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018219

- Svallfors, S. (2010) ‘Public Attitudes’, in The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tajfel, H. and J. Turner. (1986) ‘The social identity theory of Intergroup Behaviour’, in S. Worchel and W.G. Austin (eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Chicago: Nelson Hall, pp. 7–24.

- Teney, C., Lacewell, O. P. and De Wilde, P. (2014) ‘Winners and losers of globalization in Europe: attitudes and ideologies’, European Political Science Review 6(4): 575–95. doi: 10.1017/S1755773913000246

- Van Oorschot, W. and Komter, A. (1998) ‘What is it that ties … ? Theoretical perspectives on social bond’, Sociale Wetenschappen 41(3): 4–24.

- Weber, M. (1980 [1922]) Wirtschaft Und Gesellschaft. Grundriss Der Verstehenden Soziologie, Tübingen: Mohr.

- Wilson, J. and Musick, M. (1997) ‘Who cares? Towards an integrated theory of volunteer work’, American Sociological Review 62(5): 694–713. doi: 10.2307/2657355