ABSTRACT

Some participants of the public debate have argued that the world before and after the coronavirus crisis will look fundamentally different. An underlying assumption is that this crisis will alter public opinion in such a way that it leads to profound societal and political change. Scholarship suggests that while some policy preferences are quite volatile and prone to change under the influence of crises, core values formed during childhood are likely to remain stable. In this article, we test stability or change of a well-selected set of opinions and values before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We rely on a unique longitudinal panel study whereby the Dutch fieldwork of the European Values Study 2017 web survey serves as a baseline; respondents were re-approached in May 2020. The findings indicate that values remain largely stable. However, there is an increase in political support, confirming the so-called rally effect. We conclude our manuscript with a response to the futurists expecting changes in public opinion because of the coronavirus crisis.

1. Introduction

‘Never let a good crisis go to waste,’ Winston Churchill once said. The coronavirus crisis, which affected all corners of the world, made influential thinkers contemplate about what the future might bring for European societies. To give but one example, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, futurist Yuval Noah Harari (Citation2020) saw governments confronted with two main dilemmas: one between totalitarian surveillance and citizen empowerment, and another between nationalist isolation and global solidarity. Because public policy requires broad public support (Burnstein Citation2003), such political choices would require a clear shift in public opinion in the direction of one of the two options. The first dilemma, for instance, would require a preference change towards either less focus on privacy or more focus on individual responsibility. However, there is lack of evidence about whether the current pandemic has the potential to change public opinion en masse. The aim of this contribution is to verify empirically which opinions and values have shifted amidst the coronavirus crisis.

Empirical research on public opinion in crisis times, including after terrorist attacks (Dinesen and Jaeger Citation2013; Hetherington and Nelson Citation2003), natural disasters (Malhotra and Kuo Citation2006), and during economic downturns (van Erkel and van der Meer Citation2016; Margalit Citation2013; Reeskens and Vandecasteele Citation2017), confirm that the exposure to insecurity causes a conservative reflex. It has been shown for instance that populations give more support to governments or display negative sentiments towards outgroups. At the same time, such effects are often short-lived (Dinesen and Jaeger Citation2013; Margalit Citation2013), suggesting that public opinion moves back to its initial position when the source of the insecurity has been removed. Yet, COVID-19 poses a novel challenge, where immediate medical insecurity about the virus goes hand in hand with financial insecurity posed by the economic fallout caused by social distancing measures. The fact that the present crisis is a context unfamiliar to European societies proposes a unique opportunity to study the stability or change of public opinion, contributing to scholarly knowledge by separating values, attitudes and preferences.

In this contribution, we depart from seminal insights on the stability and volatility of public opinion (Converse Citation1964; Inglehart Citation1977; Uslaner Citation2002). These suggest that values socialized at a young age are stable within individuals over time; by contrast, opinions are expected to be more volatile as they are a reflection of current conditions. In this contribution, we empirically verify which values and opinions change and which remain stable amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

For our test, we rely on unique data gathered as part of the most recent Dutch data collection of the European Values Study (2020). The mixed mode design of the 2017 survey allowed for re-approaching web survey participants (LISS Panel) in May 2020. By exploring concordant response patterns among individuals between 2017 and 2020, as well as within-individual changes between these waves, we respond to questions about the extent to which the present crisis has shaken up public opinion, or whether it has remained invariant to current challenges posed by COVID-19.

2. Theory

Existing literature on the stability of public opinion distinguishes between ‘core values’, and ‘mere preferences’, i.e. attitudes (Uslaner Citation2002: 57). Values are usually enduring, whereas preferences might change over time, sometimes even from day to day. Values, broadly understood as ‘concepts or beliefs about desirable end states or behaviors that transcend specific situations, guide selection or evaluation of behavior and events, and are ordered by relative importance’ (Schwartz & Bilsky Citation1987: 551), are thought to be stable, because they largely result from socialization processes at a young age (Inglehart Citation1977). Our parents have taught us certain values that got anchored in our belief systems, and also the circumstances which we grew up in influence the attachment to certain values over others. Such values are at the core of our belief system, and the more central a value is within this system, the more stable it is over time (Converse Citation1964). This does not mean that values never change, but they do so far less often than preferences, which make them inherent to our identity (Uslaner Citation2002).

Scholarship often highlights the stability of religious values,Footnote1 as they are imprinted during ones upbringing (Markides Citation1983). Also values that relate to the core of a belief system tend to be very stable, as they form the basis for one’s morality and have become part of the personal identity (Converse Citation1964; Inglehart Citation1985; Uslaner Citation2002). After religious values, also political affiliation tends to be stable (Carmines and Stimson Citation1980; Converse Citation1964; Inglehart Citation1985; Uslaner Citation2002). Being more left- or right-wing oriented is an identity individuals regularly express throughout their lives, for example in political discussions or through voting. This identity is also fundamental for other beliefs. Finally, in terms of core values, Inglehart (Citation1977; Citation1985) propagates that the extent to which an individual holds more materialistic or post-materialistic values depends on the socio-economic position during childhood socialization.

For opinions, we rely on the definitions of an attitude, which is defined as ‘a disposition to respond favorably or unfavorably to an object, person, institution or event’ (Ajzen, Citation2005: 3). Preferences that result from them, are based on an assessment of the current state of affairs, rather than on ingrained norms or ideals. They often entail cognitive evaluations of current (political) actors, institutions, or policies (Converse Citation1964; Uslaner Citation2002). Attitudes and preferences change quite easily when people find themselves in a different condition, when they are provided with convincing information, or when actors or institutions change their policies (Uslaner Citation2002). A typical example of an unstable preference is political trust (Mishler and Rose Citation2001). It largely depends on the performance of incumbent politicians and current policies: when people feel like the government is performing well, they are politically trusting and vice versa, making political trust volatile.

Political preferences are, however, not homogenous. To distinguish between political issues, Carmines and Stimson (Citation1980: 78) distinguish between ‘easy issues’ and ‘hard issues’, whereby the former originate from long-standing principles socialized at an early age and are addressed with ‘gut responses’, while the latter are more situational and require sophisticated evaluation and contextual information. The distinction between both is based on three criteria: ‘1) the easy issue would be symbolic rather than technical, 2) it would more likely deal with policy ends than means, 3) it would be an issue long on the political agenda’ (Carmines and Stimson Citation1980: 80). In our study, this distinction is of utmost importance. Uslaner (Citation2002), for instance, categorizes attitudes on gender equality as volatile, because they were in flux in the 1970s. However, based on Carmine and Stimson’s (Citation1980) criteria, we would consider attitudes towards gender equality as an ‘easy issue’ and hence more stable: it is symbolic, it deals with policy ends, and it has been on the political agenda for a long time (see also Inglehart and Norris Citation2016).

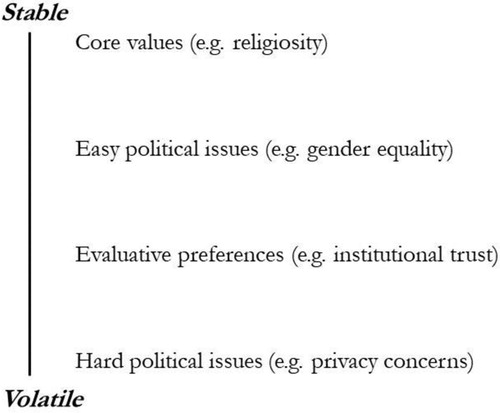

summarizes the ranking of discussed values, attitudes and preferences along the continuum of stable versus volatile. In this list, values socialized at a young age are proposed as most stable, whereas hard issues that typically prompt evaluations in a specific context are below the list presented as most volatile.

Figure 1. The Expected Stability of Values Before and During the Coronavirus Crisis.

Note: Ranking is based on Converse (Citation1964, 46).

This brief review highlights that the influence of the current coronavirus crisis might differ along the type of values, attitude or preference. The stability or change of values and opinions is to some extent conditional to external circumstances, proposing expectations about how the current COVID-19 pandemic may affect the rank order. First of all, (temporal) economic drawbacks or physical insecurities could cause short-term value change, even for values that are usually highly stable due to childhood socialization, such as (post-)materialism (Inglehart Citation1985). Secondly, the way information is presented to the public strongly influences the extent to which people perceive an issue as ‘easy’ or ‘hard’, and thus the extent to which the underlying values are likely to change (Carmine and Stimson Citation1980; Converse Citation1964). If non-pharmaceutical interventions, including a nation-wide lockdown, are perceived as a simple ‘freedom or no freedom’ or ‘healthy or ill’-issue – an easy issue – people are less likely to (temporarily) change their values than when the complexities of the issue, context, and interventions are presented, which makes it a hard issue in the framework of Carmines and Stimson (Citation1980).Footnote2

In sum, for our study of the influence of present crisis on stability or change of public opinion, we expect that highest stability is present among the core values that are shaped during childhood socialization and are known for being highly stable over the lifespan, including religiosity, political ideology, social trust, and post-material value orientations. Most volatile will be preferences about ‘hard’ political issues, e.g. topics like privacy, which have been politicized during the current pandemic because of discussions over e.g. a coronavirus tracking smartphone application, storing customer contact details in restaurants and contact tracing. Also expressions of institutional trust are expected to be rather volatile, as they depend upon government functioning and populations might ‘rally’ around incumbent governments. For ‘easy’ policy preferences, for instance gender role attitudes or redistributive preferences, the expectation is that they are more volatile than core values, but more stable than hard issues.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

For this study, unique panel data was gathered for which ethical approval was granted by the Ethical Review Board of the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences. As a baseline, we use the Dutch part of the European Values Study 2017 (EVS Citation2020). For its data collection, a mixed mode strategy was applied, combining face-to-face CAPI data collection with a CAWI web survey. We only consider the latter, as we have been able to re-approach these respondents over time. From the LISS Panel (CentERdata Citation2020), a probability-based household panel study, drawn from population registers, consisting of approx. 5000 households and approx. 7500 individuals, a sample of 2515 respondents was drawn. FieldworkFootnote3 took place between 1 September 2017 and 31 January 2018, realizing a sample of 2053 respondents (approx. 80 percent response rate). In May 2020, the same respondents that participated in the initial data collection and continued to be LISS panel members were re-approached with a strongly reduced questionnaire to test stability and change of a well-considered set of items. Due to panel attrition and survey nonresponse, 1281 respondents remain, allowing for within-individual over-time comparisons.Footnote4 Nonresponse analyses indicate that over the course of time, we lost particularly women as well as the active part of the population.Footnote5 Because of the idea that particularly younger cohorts are prone to volatile responses, value and attitude stability might be overestimated. Post-stratification weights are applied to correct for the Dutch population’s distribution with regard to sex, age, education, and region.

3.2. Measuring values, attitudes and preferences

We test the stability or change of all items collected in both 2017 and 2020. For precise question wordings, we refer to the EVS Master Questionnaire, which can be retrieved from GESIS (EVS Citation2020), or to online Appendix 1, which clarifies the response categories as used for the analysis in this contribution.Footnote6 Here, we present the items in the theoretically based rank order from most stable to most volatile.

Religiosity, in the questionnaire restricted to the item asking the frequency of praying, is expected to be most stable. We also consider political ideology, broadly defined and measured with the left-right self-placement scale, as quite stable, as well as social trust, asked with the item whether most people can be trusted or whether you cannot be too careful. We further include post-materialism as a stable value, measured using the Inglehart index, which asks about the two most important political aims from this list of four, i.e. (a) ‘maintaining order in the nation’, (b) ‘giving people more say in important government decisions’, (c) ‘fighting rising prices’, and (d) ‘protecting freedom of speech’, with (b) and (d) as post-material aims, and (a) and (c) as material ones. Morality items ought to be stable too. Here we include legal permissiveness, which is a scale averaged over the items whether claiming state benefits even if one is not entitled to it, and cheating on taxes if one has the chance is acceptable behavior. Moral permissiveness, then, is about whether euthanasia, suicide, and having casual sex are permissible. We also consider diffuse political norms that flow from post-materialism as relatively stable, i.e. national pride, as well as items about good ways of governing the country, in our survey asked by whether it would be good or bad to have respectively a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections, and experts making decisions according to what they think is best for the country.

Less stable are so-called easy political issues which appeal to an emotional ‘gut’ response. Gender equality is measured by the item whether families suffer when women work full-time. Further, we include prejudice towards immigrants, as averaged over three items whether immigrants take away jobs, make crime problems worse, and are a strain on the welfare system. Furthermore, we examine EU scepticism using the item whether European integration has gone too far. We also consider social solidarity, by creating a scale of the extent to which respondents are concerned about the living conditions of elderly people, the unemployed, immigrants, and the sick and disabled. Related are two items measuring redistribution preferences, namely whether incomes should be made more equal and the extent to which individuals or the state should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for.

More volatile, then, are the perceptions that trigger an evaluative response. Here, we consider institutional trust, following the distinction (e.g. Rothstein and Stolle Citation2008) between trust in representative institutions (a scale averaged over two items regarding confidence in respectively government and parliament) and trust in societal institutions (averaged over two items regarding confidence in respectively the education system and the health care system). Satisfaction with the functioning of the political system is also covered. In addition, items about the importance of work, family, friends and leisure are included.Footnote7

Most volatile are ‘hard’ political issues that require more elaborate evaluation of social issues. One example might be a scale measuring concerns over privacy infringes by the government, averaged over three items if the government may keep people under video surveillance in public areas, monitor all emails and any other information on the internet, and collect information about their citizens without their knowledge.

3.3. Assessing stability and change

To assess stability or change in values, attitudes and preferences, we perform two tests. First, we look at the Kendall’s tau-b coefficient, which is based on the number of concordant and discordant responses over time (Uslaner Citation2002: 59).Footnote8 This coefficient reads as a correlation coefficient but is based on the ranks of the data, with higher values indicating a higher similarity between 2017 and 2020, and thus more stability.

Second, we calculate individual difference scores by subtracting the 2017 score from the 2020 score. The implication is that a higher difference score indicates a stronger preference for the listed values or opinions in 2020 than in 2017. We perform one-sample t-tests; the sign of the test-value indicates whether on the whole, preferences for this item increased or decreased; the significance of the test indicates whether this increase or decrease differs from zero, hence, whether values changed or are stable.

4. Results

presents the results of our analyses, distinguishing stability in the rank order (column ‘tau-b’), and the direction of change (column ‘t-value’), as well as whether the rank order in individual stability confirms the theoretical expectations (column ‘confirm’), i.e. whether a high stability was expected (top position in the table) or low stability was expected (bottom position in the table). For 18 of the 23 studied values, the rank order in individual value stability is in line with theoretical assumptions.

Table 1. Values Stability and Change, 2017–2020.

Most stable is religiosity, expressed by praying, which is deeply ingrained at a young age and relatively stable over the lifespan (Markides Citation1983). Apparently religiosity is unaffected by a crisis of the present magnitude. The same holds for political ideology in terms of left-right self-placement (see also Miller and Shanks Citation1996; Sears and Funk Citation1999): there is a large overlap in respondents’ positioning in 2017 and 2020, and no change in average values between the two waves. Confirming Uslaner (Citation2002), people do not readily change in social trust either. However, at the aggregate, social trust increased between 2017 and 2020, implying that those who changed scores moved in the direction of more social trust. In combination with solidarity, which remains largely stable between the two waves, our findings suggest that while people might not have become overwhelmingly more pro-social amidst the crisis, at least no harsher stances were adopted.

The bottom of , where most volatility was found, shows some patterns that follow the theoretical assumptions, and others that are more surprising but might be understood given the particularities of the current COVID-19 pandemic. According to the literature, we expected that complex policy preferences, in particular, are susceptible to change (Carmines and Stimson Citation1980). We indeed see that concern over privacy infringes, theorized as a ‘hard issue’, is quite unstable and increase over time, which might be a direct response to discussions over contact tracing measures. On the other hand, the preference for state intervention is volatile and decreased slightly although we expected stability in this item. Similar is the reliance on expert involvement in policy making and preference for strong leadership, which increased since 2017. These latter findings can be understood given that state interventions and the role of expertise for policy decisions have been more salient in the pandemic response to a new virus than usual. Finally, Inglehart’s post-materialism index was also subject to volatility between 2017 and 2020. While the theory expects that these dispositions ought to be stable, here, the corona crisis induced a politically antidemocratic ‘rally effect’ (cf. Mueller Citation1973).

This brings us to a related unexpected finding. Based on the literature, institutional trust is supposed to be quite volatile, as it reflects institutional performance. Here, we see that while more trust is given to both representative and societal institutions amidst the corona crisis, confirming the ‘rally effect’ (see also Bol et al. Citation2020), most respondents actually did not change positions. However, all and all, apart from some extraordinary but plausible positions, it doesn’t seem like the coronavirus crisis has shaken up values tremendously.

5. Conclusion

For political and societal reform to take place, public opinion should provide a clear window of opportunity by taking sides in particular debates. The results of our analysis indicate, however, that this prospect of change of values, attitudes and preferences amidst the corona crisis is rather sobering. The rank order of the items studied in terms of their relative stability follows most seminal studies that investigated over-time stability in the absence of a crisis as the world in general and European societies in particular are currently facing (Converse Citation1964; Uslaner Citation2002). From that perspective, futurists who thought that the world before and after COVID-19 would look vastly different have overlooked how persistent values actually are in the face of exogenous shocks.

In terms of political opportunities, values undergirding democratic governance are quite volatile amidst the coronavirus crisis. As Inglehart (Citation1985) already suggested, these normally deeply rooted values may temporarily change in response to external threats. By comparison, institutional trust, which ought to be volatile as it is a reflection of government functioning, shows quite some concordant responses, although public opinion is more supportive of actors relevant for handling the COVID-19 pandemic. The interpretation is therefore a clear ‘rally effect’ (Mueller, Citation1973): more an emotional than a rational response to institutional functioning (see also Bol et al., Citation2020).

This finding of a ‘rally effect’ does, however, not indicate that governments can implement any measure to contain the virus: people do, for instance, show more concerns over privacy infringements by the government. People seem to be extremely sceptical about how contact tracing measures to fight the pandemic like coronavirus tracking apps affect their personal realm. This shows that concerns over privacy are ‘hard’ political issues; it is a technical discussion on a relatively new issue with practical policy means. This finding shows how multifaceted political support amidst the corona crisis actually is, and how it requires intense scrutiny in the near future.

Evidently, there are limitations in our study. Our findings confirm that values and opinions for the most part react to this crisis as can be expected according to public opinion research. Nevertheless, the most important liability is the selected case. With its self-proclaimed ‘intelligent lockdown’, the Dutch government addressed Dutch culture, with an emphasis on individual responsibility, potentially producing more institutional trust. In addition, economic aid measures might have remedied immediate economic hardship, leaving some values unaffected. This begs the question whether the present findings can be paralleled in other countries, or whether they are unique for the Netherlands. Secondly, the present study did not provide a detailed overview of which segments of the population are more prone for change. Studies document that particularly the young and the most vulnerable groups would report change (Inglehart Citation1997). Given the particular research question of the present article, we aimed for breadth in terms of items rather than depth in terms of understanding the socio-demographics. Several changes over time (e.g. the increase in social trust and decrease in prejudice towards immigrants) require more scrutiny; future studies can provide a more segmented analysis. An additional limitation is the limited timespan of the current study. The stability and volatility discovered amidst this ‘intelligent lockdown’ might be temporary and not long-lasting, making that additional rounds of data collection are necessary. Responding to the COVID-19 special issue of present journal, our study presented the findings of a first round of data collection. With a second wave to be fielded in October 2020, we hope to give a more comprehensive overview of how public opinion has shifted or remained stable over the course of the coronavirus crisis.

Acknowledgment

We thank Miquelle Marchand and colleagues from CentERdata for their prompt implementation of this survey as part of the LISS Panel, as well as Giovanni Borghesan for calculating the post-stratification weights. We are also indebted to the guest editor, Martina Klicperová, and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tim Reeskens

Tim Reeskens is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at Tilburg University and holds the Jean Monnet Chair on Identities and Cohesion in a Changing European Union. He is the Program Director of the European Values Study Netherlands. His research interest regard the social consequences of immigration and diversity, with a particular focus on values and attitudes, social capital and generalized trust, national identity, and attitudes towards the welfare state. His research appeared in the European Sociological Review, the Journal of European Social Policy, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, and Comparative Political Studies.

Quita Muis

Quita Muis is a PhD researcher at the Department of Sociology at Tilburg University, affiliated with the European Values Study and Tilburg University's Impact Program. For her dissertation, she investigates polarization, particularly between educational groups. Her broader research interest includes (changes in) public opinion, polarization, and identity. She is currently a member of the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences Faculty Council.

Inge Sieben

Inge Sieben is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at Tilburg University. Her research interests are comparative research on religion, morality and family values, and social stratification research, mainly about inequalities in educational opportunities. She is co-author of the Atlas of European Values (Brill, 2011) and coordinator of the KA2 Erasmus+ project European Values in Education (EVALUE). She published her work in Work, Employment and Society, European Sociological Review, Acta Sociologica, and European Societies.

Leen Vandecasteele

Leen Vandecasteele is Associate Professor at the Institute for Social Sciences at the University of Lausanne. She is affiliated with the NCCR LIVES – Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives. Her research interests are in the area of social inequality, poverty and social policy in the life course. Her research appeared in, among others, the European Sociological Review, European Societies, the Review of Income and Wealth and Urban Studies.

Ruud Luijkx

Ruud Luijkx is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology at Tilburg University, Associate Member of Nuffield College (Oxford) and Visiting Professor at the Department of Sociology and Social Research at the University of Trento (Italy). He is the Chair of the Methodology Group and Member of the Executive Committee of the European Values Study. His research interests are social inequality and mobility, and the methodology of survey research. He published among others in the American Journal of Sociology, the European Sociological Review, Social Science Research, and Research in Social Stratification and Mobility.

Loek Halman

Loek Halman is an Associate Professor at Department of Sociology at Tilburg University and co-author of the Atlas of European Values (Brill Publishers, 2011). He is involved in the European Values Study as Chair of the Executive Committee and member of the EVS Theory Group. He was also involved in the Comenius project (2009-2012) on European Values Education (EVE) and currently involved in its successor EVALUE. He teaches on values, civil society, and national and regional identity. His research interests are on the international and longitudinal comparative study of values and norms. He published numerous books and edited volumes related to these topics, as well as articles in high-ranked, peer-reviewed journals such as British Journal of Sociology, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, European Sociological Review, European Societies, and Social Compass.

Notes

1 An important disclaimer, here, is that most of this scholarship is US-based, where the religion and secularization take a different position than in Europe (Casanova Citation2007).

2 See Carmines and Stimson (Citation1980: 80–81) for a similar example regarding the Vietnam War.

3 The fieldwork was cut in two phases (first phase between September 11 and October 31, 2017; second phase between January 1 and 31, 2018) because the web survey of the EVS was administered in a matrix design. This design implied that the EVS Master Questionnaire was split in a core and four remaining blocks. Respondents of the first phase were asked to fill in the core module and two randomly selected blocks. In the second phase, respondents were asked to complete the matrix as they were asked to complete the two remaining blocks of items that they were not offered in the first phase; 1722 of the original 2053 did so. For more information, check https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/survey-2017/methodology/

4 To increase statistical power, 326 additional (that were not part of the 2017 questioning) respondents have been surveyed. However, because of the specificity of stability or volatility of values, attitudes and preferences, these respondents are not considered, here. For this round of data collection, the response rate was 78 percent.

5 Detailed analyses, which can be retrieved from the online Appendix 2, indicate that dropout in the panel was most likely among the younger respondents (18–29 years old), while particularly those aged 50–79 years retained in the panel. Also women were more likely to abstain from participating in the 2020 panel.

6 Additional information, such as syntax files, can be retrieved from the corresponding author.

7 Admittedly, these items are harder to categorize, since their nature is somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, they could be viewed as an evaluation of one’s current, context dependent capability to divide time between family, friends, work and leisure, which would indicate an attitude. On the other hand, they could refer to the extent to which respondents generally value these aspects in their life, which would indicate a rather stable value. With some uncertainty, we therefore expect these issues to take a place in the middle of the stability ranking.

8 In case of social trust, which is dichotomous, the phi-coefficient is calculated (see Uslaner Citation2002: 59).

References

- Ajzen, I. (2005) Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed., Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A. and Loewen, P. J. (2020) ‘The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: some good news for democracy?’, European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12401

- Burnstein, P. (2003) ‘The impact of public opinion on public policy: A review and an agenda’, Political Research Quarterly 56(1): 29–40.

- Carmines, E. G. and Stimson, J. A. (1980) ‘The two faces of issue voting’, American Political Science Review 47(1): 78–91.

- Casanova, J. (2007) ‘Rethinking secularization: A global comparative perspective’, in P. Beyer and L. Beaman (eds.), Religion, Globalization, and Culture, Leiden: Brill, pp. 101-120.

- CentERdata. (2020). LISS Panel Data Archive, Database, https://www.lissdata.nl/.

- Converse, P. E. (1964) ‘The Nature of belief systems in Mass Publics’, in D. E. Apter (ed.), Ideology and Discontent, New York: Free Press of Glencoe, pp. 206-261.

- Dinesen, P. T. and Jaeger, M. M. (2013) ‘The effect of terror on institutional trust: New evidence from the 3/11 Madrid terrorist attack’, Political Psychology 34(6): 917–926.

- EVS (2020). European Values Study 2017: Integrated Dataset (EVS 2017). ZA7500 Data file Version 3.0.0 [dataset] GESIS Data Archive. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13511 [Accessed 6 June 2020].

- Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Harari, Y. N. (2020) ‘The world after coronavirus’, Financial Times (March 20).

- Hetherington, M. J. and Nelson, M. (2003) ‘Anatomy of a rally effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism’, PS: Political Science & Politics 36: 37–42.

- Inglehart, R. (1977) The Silent Revolution. Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. (1985) ‘Aggregate stability and individual-level flux in mass belief systems: The level of analysis paradox’, American Political Science Review 79(1): 97–116.

- Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. and Norris, P. (2016) Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have- nots and cultural backlash, Harvard Kennedy School, Working Paper No. RWP16-026.

- Malhotra, N. and Kuo, A. G. (2006) ‘Attributing blame: The public’s response to hurricane Katrina’, Journal of Politics 70: 120–135.

- Margalit, Y. (2013) ‘Explaining social policy preferences: evidence from the Great Recession’, American Political Science Review 107: 80–103.

- Markides, K. S. (1983) ‘Aging, religiosity, and adjustment: A longitudinal analysis’, Journal of Gerontology 38: 621–625.

- Miller, W. E. and Shanks, J. M. (1996) The New American Voter, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Mishler, W. and Rose, R. (2001) ‘What are the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and cultural theories in post-communist societies’, Comparative Political Studies 34: 30–62.

- Mueller, J. E. (1973) War, Presidents and Public Opinion, New York: Wiley.

- Reeskens, T. and Vandecasteele, L. (2017) ‘Hard times and European youth. The effect of economic insecurity on human values, social attitudes and well-being’, International Journal of Psychology 52: 19–27.

- Rothstein, B. and Stolle, D. (2008) ‘The state and social capital: An institutional theory of generalized trust’, Comparative Politics 40: 441–459.

- Schwartz, S. H. and Bilsky, W. (1987) ‘Toward a universal psychological structure of human values’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53: 550–562.

- Sears, D. O. and Funk, C. L. (1999) ‘Evidence of long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions’, Journal of Politics 61: 1–28.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2002) The Moral Foundations of Trust, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- van Erkel, P. F. A. and van der Meer, T. W. G. (2016) ‘Macroeconomic performance, political trust and the Great Recession: A multilevel analysis of the effects of within-country fluctuations in macroeconomic performance on political trust in 15 EU countries, 1999-2011’, European Journal of Political Research 55: 177–197.

Appendices

A1: Question Wordings and Response Categories

A2. Nonresponse Analysis of Participation in the 2020 Corona Questionnaire

Over the course of time, 772 respondents dropped out. While the 2017 data collection consisted of 2053 respondents, 1281 of these 2053 respondents participated in the 2020 data collection (i.e. a dropout of 38 per cent). We cannot assume that this nonresponse is random; certain stages in life and eventually also certain dispositions make that some respondents are more likely to stay engaged in the LISS Panel, while others increase the likelihood to drop out.

In this nonresponse analysis, we briefly review what basic sociodemographic respondent characteristics explain dropout in the 2020 wave. To do so, we categorize age in decades, i.e. respondents in 2017 being 18–29 years old (N = 259), 30–39 years old (N = 301), 40–49 years old (N = 310), 50–59 years old (N = 329), 60–69 years old (N = 434), 70–79 years old (N = 332), and respondents from 80–99 years old (N = 88). We further distinguish between men (N = 912) and woman (N = 1141). Also levels of education is included, which is ISCED-coded from 1 (primary education or less) to 7 (Master’s degree or higher). Last but not least, we also include trust in partisan institutions in 2017, measured by the average of trust in government and trust in parliament.

Table A2. Explaining Nonresponse in the Second Wave.

The results of the regression analysis shows that particularly the active population and the oldest cohort was most likely to drop out. Compared with the oldest cohort (80-99 years old; chosen because medical conditions hinder continuous participation in the LISS Panel), the youngest cohorts is 71 percent more likely to drop out, while there is no significant difference with the age groups of 30–49 years old. By contrast, those 50–79 years old are less likely to drop out. In addition, woman are 30 percent more likely to drop out than men. While we could have expected that the lower educated and those low on trust would be more likely to drop out, the analysis does not support this finding, as significant effects are absent.