ABSTRACT

From the outset of the coronavirus crisis, Sweden has been heavyily criticized for its exceptional pandemic mitigation policy. Sweden is often accused pursuing an abnormal and ‘disastrous strategy' that puts its citizens’ lives at risk. In this article, we analyze the most widespread criticisms of Swedish ‘exceptionalism’, in order to identify and describe the prevailing implicit norms on which the criticisms are based. While the explicitly proclaimed norms assert that the anti-pandemic measures are aimed at keeping the number of infections below the maximum capacities of the national health systems, the implicit norms turn out to be significantly different, i.e. primarily about the number of coronavirus-related deaths. Moreover, we point out that this norm is not about protecting lives in general, but only about protecting people from dying with a coronavirus infection. We argue that this implicit norm is asymmetric and therefore not tenable, because it implies that a death from the coronavirus is considered more important than a death from another infection. Against this backdrop, we conclude by discussing possible future developments of this norm and call for an international public debate about how much protection against infectious diseases society should provide in general – not only against one particular disease.

Introduction

In the first months of the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, Sweden was broadly criticized, particularly by European media, health experts, and scientists, for its exceptional pandemic mitigation policy. Beginning in early 2020, a novel coronavirus began to spread around the world, resulting in a worldwide pandemic. Most European countries began to become affected in February or March and, from then onwards, experienced a sharp increase of infection numbers, triggering the employment of anti-pandemic measures (The Local Citation2020). Unlike most other European countries which temporarily imposed wide-ranging lockdowns and other strict measures, Sweden chose a less restrictive strategy for dealing with this novel coronavirus by opting for softer measures, such as voluntary social distancing, rather than extensive closures and lockdowns (Irwin Citation2020). Critics condemned this Swedish strategy as a ‘historic mistake’ (Baker Citation2020), a ‘fatal error’ (Pieper Citation2020), and a ‘mad experiment’ (Marcus Carlsson cited in Henley Citation2020a), commonly accusing Sweden of needlessly risking the lives of its citizens and urging a radical course correction. Although, prima facie, the reasons for these criticisms may seem self-evident, we believe that it is worth scrutinizing the underlying norms.

Social norms pertain to expectations about acceptable behaviors or actions (Goffman Citation1971; Luhmann Citation2020). Large societal crises usually challenge and transform existing norms and bring about new ones (Andreotti et al. Citation2013; Grasso and Giugni Citation2019; Zambarloukou Citation2015). Correspondingly, the current COVID-19 crisis has already changed social norms by the time we finish writing this article. In this article, we analyze critical norms at stake, as well as potential norm changes that occurred in the first months of the crisis until July 2020.

In scrutinizing the criticisms of Swedish ‘exceptionalism’ (Palm Citation2020) as expressed by health professionals, scientists, and mass media representatives, we detect a significant divergence between officially proclaimed norms (which we call ‘norm texts’) and the underlying norm concepts that have emerged in the course of the crisis.Footnote1 Whereas the official main goal of the pandemic mitigation interventions has been to keep the health system from getting overburdened, we observe the emergence of an implicit norm actually focused on the prevention of deaths related to a coronavirus infection. We point out that this norm is thereby not about protecting lives per se, but merely about preventing people from dying from or with a coronavirus infection. Hence, we argue that this implicit norm is asymmetric and thus not tenable, because it implies that a death from the novel coronavirus is more important than a death from another infection, such as influenza. Against this backdrop, we conclude by discussing possible future developments of this norm and call for an international debate about how much protection against infectious diseases our society should provide in general – not only against one particular infectious disease.

Implicit social norms

The prevailing norms of a society or other social systems are often hard to define. Even though there is a wealth of explicit expectations of socially desirable behaviors or situations, these official ‘norm texts’ (Luhmann Citation2000: 29) often have little to do with the actual prevailing norms (Valentinov Citation2019; Roth et al. Citation2019). Many norms that guide actual behavior remain implicit (Luetzelberger Citation2014). They emerge and are sustained by ‘unspoken’ or taken-for-granted, self-evident social processes (Garfinkel Citation1967; Revilla et al. Citation2018) and are always supported by the possibility of sanctioning (Goffman Citation1971). Hence, implicit norms surface when sanctions of ‘deviant’ behaviors occur.

In sociology, it is therefore a well-established strategy to search for violations or breaches, in order to identify valid implicit norms (e.g. Garfinkel Citation1967; Goffman Citation1971; Luhmann Citation2000). Norm violations are often easily recognized, as they are readily observable when violators face explicit criticism or even outrage in the face of the alleged misconduct or unacceptable situation. Such criticism commonly expresses what is wrong and why, which facilitates the reconstruction of the actual norms underlying the criticism. For that reason, Niklas Luhmann (Citation2000) even went so far as to assert not only that violation makes the norm visible, but that ‘the norm is actually only generated through the violation’ (29).

In the case of the 2020 coronavirus crisis, the widespread criticism of Sweden’s response seems to indicate its ‘exceptionalism’ violated a norm. Many countries have explicitly codified norms regarding socially correct behavior, such as mandatory face masks in certain situations. The case of Sweden, by contrast, allows us to gain initial insights into some of the implicit norms that have emerged.

Analyzing the criticism of the Swedish strategy

To explore the criteria against which the Swedish strategy is measured, we need to first take a look at the explicit evaluation criteria and, thus, the official ‘norm texts’. These are broadly unambiguous. The media and politicians in many European countries pretty much everywhere agree that the main goal of the pandemic interventions has been ‘to ensure hospitals and medical staff are not overwhelmed’ (Beall Citation2020; see also: Berres and Evers Citation2020; Bidder et al. Citation2020; Edwards Citation2020; Gallagher Citation2020; Roberts Citation2020; The Brussels Times Citation2020). For instance, German Chancellor Angela Merkel (Citation2020) declared

The goal is to design the measures in a way that our health care system will not be overwhelmed.Footnote2 (see also: Bennhold and Eddy Citation2020)

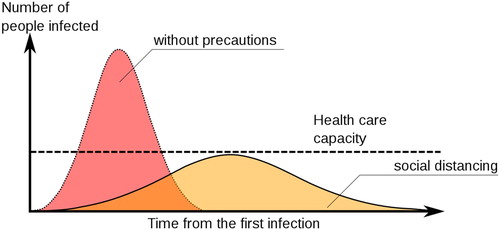

Figure 1. ‘COVID-19 health care limit’ by Johannes Kalliauer; https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:COVID-19_Health_care_limit.svg; License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

‘Flattening the curve’ of coronavirus infections to levels below the maximum capacities and thus avoiding an overburdening of the national health systems can thus be seen as the stated major goal of the anti-pandemic strategies – the official ‘norm text’ – throughout Europe.

However, in the case of criticisms of Sweden, it is apparent that this official ‘norm text’ is incongruent with the factual norms at stake for many European news media, health professionals, and scientists. In fact, from the outset, Sweden has been successful in pursuing precisely this strategy: At no time has the Swedish health system been overburdened (Löfgren Citation2020; Ringstrom Citation2020; Savage Citation2020b). At no time has Sweden been comparable to Northern Italy. Rather, Sweden has always contained the spread of the coronavirus to such an extent that the numbers of COVID-19 cases have always been below the maximum capacity of its health system – exactly as shown in (Kavaliunas et al. Citation2020). Therefore, if we measure the Swedish strategy against the official ‘norm text’, then we find that Sweden has actually been very successful in complying with the ostensible norm.

Nevertheless, in an empirical study published in July 2020, Irwin (Citation2020) declared that the claim that ‘the Swedish approach is failing’ (1) is broadly present in international media coverage. Whereas there have been some media articles or expert statements appraising the Swedish approach positively (e.g. Erixon Citation2020; Karlson et al. Citation2020; Orange Citation2020a; Salo Citation2020), strong negative criticism by news media, medical professionals, and scientists around the world seems to have been much more widespread so far (Jha Citation2020). Therefore, the sharp contrast between Sweden’s positive performance and negative evaluation shows that the official ‘norm text’ does not reflect the norms on which the criticism of Sweden is actually based.

In order to identify the actual norms at stake among the critics, we need to review the arguments advanced to criticize the Swedish strategy. To do so, we systematically collected news media articles reporting, discussing, or commenting on the Swedish strategy. To account for a diversity of sources, we selected English-language, non-tabloid digital news outlets from the three most populous European countries, as well as outlets with a particular European focus. We selected ‘The Telegraph’ (telegraph.co.uk) and ‘The Guardian’ (theguardian.com) as reputable outlets in the United Kingdom, ‘Spiegel International’ (the English edition of the German outlet ‘Der Spiegel’; www.spiegel.de/international/) and ‘Deutsche Welle’ (dw.com) for Germany, and ‘France 24’ (france24.com) for France. In addition, we selected ‘Euronews’ (euronews.com) and ‘The Local’ in the ‘Europe Edition’ (thelocal.com) as specifically European outlets. For each website, we searched for articles using the combination of the terms ‘Sweden’ and ‘coronavirus’. We then downloaded every article published between March and July 2020 reporting, discussing, or commenting on the Swedish coronavirus response strategy. In addition, we unsystematically searched the internet search engine ‘Google’ with several combinations of terms to find related articles from other international news media. Finally, both authors had already started collecting news articles before conducting the systematic search, and those articles were also included in our analysis. In sum, we collected some 158 articles from these sources. These account for a large portion of the English-language international news coverage with special attention devoted to European media, including leading national media outlets in the English language from the three most populous European countries.

After reading the collected articles, we first found that many directly criticized the Swedish mitigation strategy and/or reported on such critiques, thereby confirming previous research results (Jha Citation2020; Irwin Citation2020).Footnote3 After closely examining the critical articles, we realized that almost all critics of the Swedish strategy were consistently concerned, in the first place, with one central issue – the number of corona-related deaths – which appears to be comparatively high. Indeed, the arguments behind the criticism also often include issues such as the general number of infections, lack of testing, the number of deaths in elderly care homes, and the economic impacts of the absence of controls. However, the sheer number of coronavirus-related deaths turned out to be the most crucial issue. In fact, we could not find even one critique published after April 2020 that did not specifically criticize the Swedish authorities in connection with the number of coronavirus-related deaths. Examples of such statements include the followingFootnote4:

Sweden’s liberal pandemic strategy questioned as Stockholm death toll mounts. (Ahlander and O’Connor Citation2020)

given that the country has a much higher death toll per million than its Nordic neighbours, many observers have suggested that the Swedish approach has failed. (Wheeldon Citation2020)

Was Stockholm right to respond to the pandemic with only a gentle, mostly voluntary lockdown? The country now has one of the highest death rates in the world. (Pieper Citation2020)

high death rate raises tough questions over lack of lockdown (Orange Citation2020b)

As the country’s Covid-19 death toll has spiralled, support for the government’s unique approach has frayed. (Savage Citation2020a)

Sweden touts the success of its controversial lockdown-free coronavirus strategy, but the country still has one of the highest mortality rates in the world. (Perper Citation2020)

Therefore, we may infer that the death tolls or rates seem to be the measure of all things: ‘it is the death rate that reveals the true impact of Sweden’s no-lockdown approach’ (Cuthbertson Citation2020). Hence, the corresponding norm we may identify is that deaths from or with coronavirus must be prevented. This norm is strongly prevalent amongst the critics, which include many European journalists, health professionals, and scientists.

A problematic norm

We argue that this actual norm behind the persistent criticism of the Swedish strategy is not unproblematic. If the matter at stake is not the prevention of overburdened health systems and thus the best-possible healthcare for every patient, but rather the prevention, or minimization of the number, of deaths, then it remains unclear why cases of coronavirus-related death should receive such special treatment. In fact, the implicit norm that societies should do everything to avoid coronavirus-related deaths implies a dangerous ranking of death risks, and raises the question of why the hundreds of thousands of deaths from influenza (World Health Organization Citation2018) or millions of deaths from hepatitis or tuberculosis (Chan Citation2017: 66) annually do not deserve the same attention and prevention as deaths from the coronavirus. Why would a potential or actual death from the coronavirus be more problematic than a death from influenza?

One might object that what actually counts are the estimated death numbers and that, in the case of the new coronavirus, there is reason to fear that these numbers will be in the millions. However, even then, the question remains regarding the threshold at which societies should flip the switch from acceptance to the prevention of death cases now and in the future. In the past, obviously, neither half a million influenza-related deaths nor over one million hepatitis-related deaths annually has been enough to flip this switch. Yet, for the persons concerned, a death from or with influenza is probably as bad as a death from or with the coronavirus.

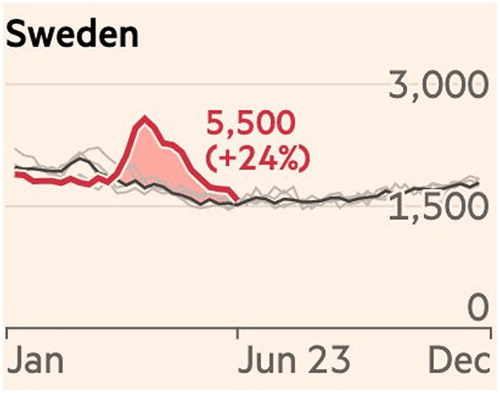

Moreover, Swedish death rates keep on declining. There has been no excess mortality in Sweden in the last week of May 2020 compared to the average of the last five years (Ahlander Citation2020). According to analyses of the European Mortality Monitoring Project, as of 25 May 2020, there has been no ‘substantial increase’ in Sweden’s mortality compared to the ‘baseline’ of how many people would be expected to die under normal circumstances.Footnote5 This development is well-known not only among researchers, but also among a broader public, due to mass media reports. For instance, analyses of mortality rates in Sweden published by both the ‘Financial Times’ (Citation2020) and the ‘New York Times’ (Wu et al. Citation2020) clearly show that mortality rates in Sweden had returned to normal levels by June 2020 ().

Figure 2. Source: FT Visual & Data Journalism team 2020: Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as countries fight Covid-19 resurgence; Financial Times / FT.com; 13 July 2020. Used under license from the Financial Times. All Rights Reserved. Reuse not permitted! Graph by John Burn-Murdoch. Graph shows the excess mortality related to the coronavirus, as illustrated by the Financial Times on July 13, 2020. The red line shows Sweden’s mortality rate for 2020, gray lines show mortalities for recent years, and the black line shows the historical average mortality rate. Graph is available under https://www.ft.com/content/a2901ce8-5eb7-4633-b89c-cbdf5b386938 (last accessed on August 20, 2020).

Despite the fact that this and similar global media coverage date back to 8 June 2020 (Ahlander Citation2020), many mass media organizations, health professionals, and academics have remained on the beaten track and have continued their harsh criticism of the Swedish ‘exceptionalism’ strategy (Palm Citation2020; Milne Citation2020; Payne Citation2020; Savage Citation2020a). This includes constant appeals to the Swedish government to radically change its strategy (e.g. Bergmann et al. Citation2020; Goodman Citation2020; Pieper Citation2020; Porterfield Citation2020; Rees Citation2020; Rolander Citation2020). Hence, we conclude that, to those critics, the problem seems to continue to be that people keep on dying from or with the coronavirus, even if these deaths no longer translate into a significant increase in mortality rates.

Thus, the underlying norm seems to be not to protect people from death in general, but to protect them from death from or with the coronavirus. In a nutshell, this implicit normative statement boils down to the idea that dying from another disease or cause is normal, whereas dying from or with the coronavirus is abnormal.

This skewed set of norms is particularly relevant in the context of previous and current debates on the value of human life and its assumed precedence over all other values, such as freedom or prosperity (Friedman Citation2020; Frakt Citation2020; Gak Citation2020; Huggler Citation2020; Rogers Citation2020). In fact, our findings suggest that the proponents of restrictive pandemic mitigation measures do not seek to subordinate everything to the value of human life per se, but rather only to maximize the prevention of death from one particular virus.

Such a reductionist set of norms, however, can hardly be sustained in the long-term. It is asymmetric as it implies that a death from or with, for instance, influenza, counts for less or is otherwise less problematic than a death from the coronavirus. We believe that such a biased, asymmetric set of norms can currently only exist at all because it is largely implicit and hardly ever explicitly reflected upon.

Possible future developments

There are two main options for the further development of this asymmetric set of norms. The first option is that, in the future, near or far, the coronavirus is going to lose its special status, and protection from death from or with the coronavirus will be given no higher priority than protection from a death from or with any other infection. Alternatively, our norms would have to develop to a point where we place as high a value on the prevention of deaths from other infections as we currently do for coronavirus-related deaths. It is an open question which position will become dominant in European societies in the near future.

Indeed, there are vaccinations for some other infections; and yet, if we believe in the general effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical pandemic interventions, then we must conclude that these interventions can save a considerable number of additional lives during the next influenza or any other ‘wave’. In this respect, recent statistics show that in many countries the number of influenza infections has dropped remarkably during the past months, presumably because of the anti-coronavirus measures (Cadell Citation2020). Therefore, if these interventions have proven effective, then why should they not become the new-normal standards for an ‘infinite mobilization’ (Sloterdijk Citation2020) for and by permanent pandemic interventions and preventions? The announcement of British Health Secretary Matt Hancock in August 2020 that millions of combined tests for the novel coronavirus and influenza will be released to ‘break chains of transmission’ for both (Kennedy Citation2020), might or might not turn out to be a step toward such a future.

Against the backdrop of these considerations, we ought to engage in an explicit debate about how much protection against disease we are expecting and what sacrifices we are willing to make in return. One might, for instance, argue that so far, it has been tragic when someone died from influenza, but it has not made us call for, agree with, or even consider mandatory face masks in shopping malls, large-scale lockdowns, or the disenfranchisement of infected voter populations (Allen Citation2020). The question for the future is whether things should stay like this.

Many are already expecting a ‘new normal’ (The Economist Citation2020), urging for a ‘Great Reset’ of the world and a future in which crucial norms should be considerably different from what they used to be (Levin et al. Citation2020). In such a ‘new normal’, society’s perception of health-related hazards would be different and would include the construction of corresponding accountabilities for minimizing the new risks (cf. Luhmann Citation2008). These would also imply changes in the degrees and forms of social control, for example, with respect to the permanent enforcement of new normal measures. Hence, norms might stabilize or change again very soon. In this respect, this article offers insights on crucial implicit norms in their intermediate state as of mid-2020. Our explication of these norms might be useful in the debates and initiatives to come. Our results will also allow further research to make comparisons with critiques of pandemic mitigation strategies in other countries, as well as with future states of the concerned norms with the intermediate state we have identified.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editors of this Special Issue and the three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable suggestions. We also wish to thank Svenja Hammer for her feedback on a prior version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Grothe-Hammer

Michael Grothe-Hammer is Associate Professor of Sociology at the Department of Sociology and Political Science of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway. His research interests include sociological theory, organizations, societal differentiation, as well as emergencies and disasters. His works have been published in journals such as Current Sociology, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Systems Research and Behavioral Science, and Public Administration.

Steffen Roth

Steffen Roth is Full Professor of Management at the La Rochelle Business School, France, and Adjunct Professor of Economic Sociology at the University of Turku, Finland. He holds a Habilitation in Economic and Environmental Sociology awarded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research; a PhD in Sociology from the University of Geneva; and a PhD in Management from the Chemnitz University of Technology. He is the field editor for social systems theory of Systems Research and Behavioral Science. The journals his research has been published in include Journal of Business Ethics, Ecological Economics, Administration and Society, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Journal of Organizational Change Management, European Management Journal, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Futures.

Notes

1 We are aware that other countries have also faced harsh criticisms. However, for this article, we have wanted to concentrate on West European democracies. Among those, Sweden has exhibited a relatively stable strategy and hence persistent criticism – in contrast to other countries such as the United Kingdom.

2 Translated from German by the authors.

3 There are, of course, differences between the different media outlets. For instance, while most outlets published predominately negative articles, The Telegraph exhibited a more balanced variety of negative and positive articles. The Guardian, on the other hand, reported mainly negative news till the end of June, but virtually stopped discussing the Swedish strategy in July. However, overall, we can identify a wide-ranging negative news coverage.

4 For more examples, see Baker (Citation2020), Brolin (Citation2020), Godin (Citation2020), Henley (Citation2020b), Milne (Citation2020), Orange (Citation2020c), Palm (Citation2020), Robertson (Citation2020), Savage (Citation2020a), Ward (Citation2020), Wheeldon (Citation2020).

5 According to the z-score graph for Sweden, as generated in the week 2020-30, z-Scores for weeks 22–29 in 2020 show no ‘substantial increase’ in mortality. Accessed on July 24, 2020 on https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/#z-scores-by-country.

References

- Ahlander, J. (2020) Sweden records first week with no excess mortality since pandemic struck. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-sweden-mortality/sweden-records-first-week-with-no-excess-mortality-since-pandemic-struck-idUSKBN23F1WK.

- Ahlander, J. and O'Connor, P. (2020) Sweden’s liberal pandemic strategy questioned as Stockholm death toll mounts. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-sweden/swedens-liberal-pandemic-strategy-questioned-as-stockholm-death-toll-mounts-idUSKBN21L23R.

- Allen, N. (2020) Hundreds barred from voting in Spanish regional elections due to COVID-19. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-spain-politics-basque-election/hundreds-barred-from-voting-in-spanish-regional-elections-due-to-covid-19-idUSKBN24B2HI.

- Andreotti, A., Mingione, E. and Pratschke, J. (2013) ‘Female employment and the economic crisis’, European Societies 15: 617–35.

- Baker, S. (2020) Skeptical experts in Sweden say its decision to have no lockdown is a terrible mistake that no other nation should copy. https://www.businessinsider.com/sweden-coronavirus-plan-is-a-cruel-mistake-skeptical-experts-say-2020-5?r=DE&IR=T.

- Baue, B. and Thurm, R. (2020) What’s at stake: Flatten the curve to respect carrying capacity. https://medium.com/@r3dot0/whats-at-stake-flatten-the-curve-to-respect-carrying-capacity-c22cb9ce17c1.

- Beall, A. (2020) Why social distancing might last for some time. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200324-covid-19-how-social-distancing-can-beat-coronavirus.

- Bennhold, K. and Eddy, M. (2020) Merkel gives germans a hard truth about the coronavirus. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/world/europe/coronavirus-merkel-germany.html.

- Bergmann, S., Bjermer, L., Caracciolo, B., Carlsson, M. and Einhorn, L. (2020) Sweden hoped herd immunity would curb COVID-19. Don’t do what we did. It’s not working. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/07/21/coronavirus-swedish-herd-immunity-drove-up-death-toll-column/5472100002/.

- Berres, I. and Evers, M. (2020) A threat to everyone: Is Germany ready for the corona pandemic? https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/coronavirus-are-we-ready-for-this-pandemic-a-47ee1cde-c5b1-4c61-8a70-8e00ddc50cc0.

- Bidder, B., Bohr, F., Clauß, A., Dahlkamp, J. and Fichtner, U. (2020) What next? Attention slowly turns to the mother of all coronavirus questions. https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/what-next-attention-slowly-turns-to-the-mother-of-all-coronavirus-questions-a-853a559e-d454-41e2-b8f2-e8f2c8d5ca18.

- Black, A., Liu, D. and Mitchell, L. (2020) How to flatten the curve of coronavirus, a mathematician explains. https://theconversation.com/how-to-flatten-the-curve-of-coronavirus-a-mathematician-explains-133514.

- Brolin, M. (2020) The coronavirus fiasco is serving as a wake-up call for many betrayed Swedes. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2020/06/09/coronavirus-fiasco-serving-wake-up-call-many-betrayed-swedes/.

- Cadell, C. (2020) Seasonal flu reports hit record lows amid global social distancing. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-influenza/seasonal-flu-reports-hit-record-lows-amid-global-social-distancing-idUSKCN24W0F8.

- Chan, M. (2017) Ten Years in Public Health, 2007–2017, Geneva: World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255355/1/9789241512442-eng.pdf.

- Chow, D. and Abbruzzese, J. (2020) What is ‘flatten the curve’? The chart that shows how critical it is for everyone to fight coronavirus spread. https://www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/what-flatten-curve-chart-shows-how-critical-it-everyone-fight-n1155636.

- Cuthbertson, A. (2020) Coronavirus tracked: Charting Sweden’s disastrous no-lockdown strategy. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/coronavirus-lockdown-sweden-death-rate-worst-country-covid-19-a9539206.html.

- Edwards, C. (2020) What's missing from Sweden's coronavirus strategy? Clear communication. https://www.thelocal.se/20200325/whats-missing-from-swedens-coronavirus-strategy-communication.

- Erixon, F. (2020) The Swedish experiment looks like it’s paying off. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-swedish-experiment-looks-like-it-s-paying-off.

- Financial Times (2020) Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as countries start to reopen. https://www.ft.com/content/a26fbf7e-48f8-11ea-aeb3-955839e06441.

- Frakt, A. (2020) Putting a dollar value on life? Governments already do. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/upshot/virus-price-human-life.html.

- Friedman, H. (2020) Impossible coronavirus decisions and the price tag on human life. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/29/magazine/impossible-coronavirus-decisions-price-tag-human-life/.

- Gak, M. (2020) Opinion: Economy vs. human life is not a moral dilemma. https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-economy-vs-human-life-is-not-a-moral-dilemma/a-52942552.

- Gallagher, J. (2020) Coronavirus: When will the outbreak end and life get back to normal? https://www.bbc.com/news/health-51963486.

- Garfinkel, H. (1967) Studies in Ethnomethodology, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Godin, M. (2020) Sweden’s relaxed approach to the coronavirus could already be backfiring. https://time.com/5817412/sweden-coronavirus/.

- Goffman, E. (1971) Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order, New York: Basic Books.

- Goodman, P. S. (2020) Sweden has become the world’s cautionary tale, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/07/business/sweden-economy-coronavirus.html.

- Grasso, M. and Giugni, M. (2019) ‘European citizens in times of crisis’, European Societies 21: 183–89.

- Henley, J. (2020a) Swedish PM warned over ‘Russian roulette-style’ Covid-19 strategy. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/swedish-pm-warned-russian-roulette-covid-19-strategy-herd-immunity.

- Henley, J. (2020b) We should have done more, admits architect of Sweden’s Covid-19 strategy. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/03/architect-of-sweden-coronavirus-strategy-admits-too-many-died-anders-tegnell.

- Huggler, J. (2020) Over 100 protestors held amid lockdown backlash in Germany. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/04/27/100-protestors-held-amid-lockdown-backlash-germany/.

- Irwin, R. E. (2020) ‘Misinformation and de-contextualization: international media reporting on Sweden and COVID-19’, Globalization and Health 16: 62.

- Jha, R. (2020) Sweden’s ‘Soft’ COVID19 strategy: An appraisal: observer research foundation, ORF occasional paper no 258. https://www.orfonline.org/research/swedens-soft-covid19-strategy-an-appraisal-69291/.

- Johnson, B. (2020) Mother’s delay this mother’s day the best present we can give to those who gave us life is sparing them the risk of coronavirus. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/11226522/mothers-day-best-present-risk-coronavirus/.

- Karlson, N., Stern, C. and Klein, D. B. (2020) Sweden’s coronavirus strategy will soon be the world’s. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/sweden/2020-05-12/swedens-coronavirus-strategy-will-soon-be-worlds.

- Kavaliunas, A., Ocaya, P., Mumper, J., Lindfeldt, I. and Kyhlstedt, M. (2020) 'Swedish policy analysis for Covid-19', Health Policy and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.009.

- Kennedy, R. (2020) Everything you need to know about the UK’s new 90-minute coronavirus test | Euronews answers. https://www.euronews.com/2020/08/03/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-uk-s-new-90-minute-coronavirus-test-euronews-answers.

- Levin, M., Sivaramakrishnan, S. and Shakour, S. (2020) How we’re resetting our future state. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/08/young-global-leaders-ygl-summit-2020-resetting-future-state-great-reset-covid19-crisis/.

- Löfgren, E. (2020) ‘The biggest challenge of our time’: How Sweden doubled intensive care capacity amid Covid-19 pandemic. https://www.thelocal.com/20200623/how-sweden-doubled-intensive-care-capacity-to-treat-coronavirus-patients.

- Luetzelberger, T. (2014) ‘Independence or interdependence’, European Societies 16: 28–47.

- Luhmann, N. (2000) The Reality of the Mass Media, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Luhmann, N. (2008) Risk: A Sociological Theory, New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Luhmann, N. (2020) ‘Organization, membership and the formalization of behavioural expectations’, Systems Research and Behavioral Science 37: 425–49.

- Macron, E. (2020) Adresse aux Français. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/03/12/adresse-aux-francais.

- Merkel, A. (2020) G20 und Europäischer Rat: Statement und Pressekonferenz der Bundeskanzlerin. https://www.bundeskanzlerin.de/bkin-de/mediathek/videos/statement-und-pressekonferenz-der-bundeskanzlerin-1739656.

- Milman, O. (2020) Covid-19 outbreak: what do health experts mean by ‘flattening the curve’? https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/10/covid-19-coronavirus-flattening-the-curve.

- Milne, R. (2020) Coronavirus: Sweden starts to debate its public health experiment. https://www.ft.com/content/7ecd5ded-9b90-4052-b849-0e153f701e1f.

- Orange, R. (2020a) Inside the Swedish city that may prove the country’s strategy was right all along. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/06/14/inside-swedish-city-may-prove-countrys-strategy-right-along/.

- Orange, R. (2020b) Mood darkens in Sweden as high death rate raises tough questions over lack of lockdown. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/06/08/mood-darkens-sweden-pm-lofven-criticised-severely-political/.

- Orange, R. (2020c) Sweden starts to doubt its outlier coronavirus strategy. https://www.dw.com/en/sweden-starts-to-doubt-its-outlier-coronavirus-strategy/a-53696565.

- Palm, E. A. (2020) Swedish exceptionalism has been ended by coronavirus. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/26/swedish-exceptionalism-coronavirus-covid19-death-toll.

- Payne, A. (2020) Sweden’s prime minister orders an inquiry into the failure of the country’s no-lockdown coronavirus strategy. https://www.businessinsider.com/sweden-opens-inquiry-into-coronavirus-strategy-of-no-lockdown-2020-7?r=DE&IR=T.

- Perper, R. (2020) Sweden touts the success of its controversial lockdown-free coronavirus strategy, but the country still has one of the highest mortality rates in the world. https://www.businessinsider.com/sweden-praises-coronavirus-strategy-despite-high-death-rate-2020-5?r=DE&IR=T.

- Pieper, D. (2020) A fatal error: Approval wanes for Sweden's lax coronavirus policies. https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/sweden-public-approval-of-lax-coronavirus-policies-is-waning-a-9fada573-26da-4bfc-89b9-50062197cf99.

- Porterfield, C. (2020) Sweden, under fire for coronavirus strategy, pushes back on WHO criticism. https://www.forbes.com/sites/carlieporterfield/2020/06/26/sweden-under-fire-for-coronavirus-strategy-pushes-back-on-who-criticism/.

- Rees, T. (2020) Sweden suffers record plunge despite lighter lockdown. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2020/08/05/sweden-suffers-record-plunge-despite-lighter-lockdown/.

- Revilla, J. C., Martín, P. and Castro, C. (2018) ‘The reconstruction of resilience as a social and collective phenomenon: poverty and coping capacity during the economic crisis’, European Societies 20: 89–110.

- Ringstrom, A. (2020) Stockholm shuts field hospital as pandemic slowly eases grip on capital. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-sweden-field-hospi/stockholm-shuts-field-hospital-as-pandemic-slowly-eases-grip-on-capital-idUSKBN23B1U1.

- Roberts, S. (2020) Flattening the coronavirus curve: One chart explains why slowing the spread of the infection is nearly as important as stopping it. https://www.nytimes.com/article/flatten-curve-coronavirus.html.

- Robertson, D. (2020) They are leading us to catastrophe: Sweden’s coronavirus stoicism begins to jar. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/catastrophe-sweden-coronavirus-stoicism-lockdown-europe.

- Rogers, A. (2020) How much is a human life actually worth? https://www.wired.com/story/how-much-is-human-life-worth-in-dollars/.

- Rolander, N. (2020) Swedish PM defends covid plan as immunity fails to catch on. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-15/sweden-says-latest-covid-immunity-not-enough-to-protect-citizens.

- Roth, S., Valentinov, V. and Clausen, L. (2019) ‘Dissecting the empirical-normative divide in business ethics: The contribution of systems theory’, Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 11: 679–94.

- Salo, J. (2020) WHO lauds lockdown-ignoring Sweden as a ‘model’ for countries going forward. https://nypost.com/2020/04/29/who-lauds-sweden-as-model-for-resisting-coronavirus-lockdown.

- Savage, J. (2020a) How Sweden’s herd immunity strategy has backfired. https://www.newstatesman.com/world/europe/2020/06/how-sweden-s-herd-immunity-strategy-has-backfired.

- Savage, M. (2020b) Coronavirus: Has Sweden got its science right? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52395866.

- Sloterdijk, P. (2020) Infinite Mobilization, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- The Brussels Times (2020) Coronavirus: ECDC warns against health care systems being overwhelmed. https://www.brusselstimes.com/all-news/eu-affairs/123098/european-parliament-threatens-to-block-approved-eu-long-term-budget/.

- The Economist (2020) The new normal: Covid-19 is here to stay. The world is working out how to live with it. https://www.economist.com/international/2020/07/04/covid-19-is-here-to-stay-the-world-is-working-out-how-to-live-with-it.

- The Local (2020) Coronavirus across Europe: An inside view into the developing crisis in different countries. https://www.thelocal.com/20200327/coronavirus-across-europe-an-inside-view-into-the-changing-situation-in-different-countries.

- Valentinov, V. (2019) ‘The ethics of functional differentiation: reclaiming morality in Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory’, Journal of Business Ethics 155: 105–14.

- Ward, A. (2020) Sweden’s government has tried a risky coronavirus strategy. It could backfire. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/9/21213472/coronavirus-sweden-herd-immunity-cases-death.

- Weber, N. (2020) Ausbreitung von Covid-19: Jeder Tag zählt. https://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/medizin/coronavirus-kampf-gegen-ausbreitung-von-covid-19-jeder-tag-zaehlt-a-9c56b511-a31a-4bc8-bf0f-5a6e58b33bbc.

- Wheeldon, T. (2020) Sweden’s Covid-19 strategy has caused an ‘amplification of the epidemic’. https://www.france24.com/en/20200517-sweden-s-covid-19-strategy-has-caused-an-amplification-of-the-epidemic.

- World Health Organization (2018) Influenza (Seasonal). https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal).

- Wu, J., McCann, A., Katz, J. and Peltier, E. (2020) 153,000 Missing deaths: Tracking the true toll of the coronavirus outbreak. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/21/world/coronavirus-missing-deaths.html.

- Zambarloukou, S. (2015) ‘Greece after the crisis: still a south European welfare model?’, European Societies 17: 653–7.