ABSTRACT

Drawing on three waves of survey data from a non-probability sample from Germany, this paper examines two opposing expectations about the pandemic’s impacts on gender equality: The optimistic view suggests that gender equality has increased, as essential workers in Germany have been predominantly female and as fathers have had more time for childcare. The pessimistic view posits that lockdowns have also negatively affected women’s jobs and that mothers had to shoulder the additional care responsibilities. Overall, our exploratory analyses provide more evidence supporting the latter view. Parents were more likely than non-parents to work fewer hours during the pandemic than before, and mothers were more likely than fathers to work fewer hours once lockdowns were lifted. Moreover, even though parents tended to divide childcare more evenly, at least temporarily, mothers still shouldered more childcare work than fathers. The division of housework remained largely unchanged. It is therefore unsurprising that women, in particular mothers, reported lower satisfaction during the observation period. Essential workers experienced fewer changes in their working lives than respondents in other occupations.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed the lives of people around the globe and has led to increases in social inequalities with regard to health (van Dorn et al. Citation2020 for the US and Hoenig and Wenz Citation2020 for Germany) and economic opportunities. Gender inequalities seem to have also risen as a consequence of the pandemic. For the US, for example, Collins et al. (Citation2020) found that women were more likely to reduce their working hours than men. In a cross-country comparison of Germany, the US, and Singapore, Reichelt et al. (Citation2020) reached similar conclusion but also found some variation in the pandemic’s gendered impact for the countries under study.

In this study, we explored the social and economic implications of the pandemic for gender inequality in Germany by examining changes in paid and unpaid work and in subjective well-being in response to the nationwide lockdown. People’s working and family lives were fundamentally altered when the German government ordered the closure of schools, day-care centres, restaurants, cultural facilities, and much of the retail sector in mid-March 2020. Many businesses affected by social distancing measures and declining customer demand cut their employees’ working hours or asked employees to work from home.

During the lockdown, Germany’s tradition as a ‘subsidiary’ welfare state (Esping-Andersen Citation1990), in which the family is a major provider of social welfare, was reinvigorated (after a period of decline following major policy changes in recent years; see, e.g. Blome Citation2016). As a general recommendation was to minimize contact between children and elderly people, most parents of young children in Germany (all those not considered ‘essential workers’) were left to arrange childcare and provide home schooling on their own.

In light of the lack of support for parents during the pandemic, the persistent gender segregation of Germany’s labour market (Rosenfeld et al. Citation2004; EIGE Citation2018), and the continued gendered division of paid and unpaid work (Altintas and Sullivan Citation2016; Hipp and Leuze Citation2015), we expected the pandemic to have had different effects on men’s and women’s – in particular, mothers’ and fathers’ – involvement in employment, housework, and childcare responsibilities, and thereby also on their subjective well-being.

Initial empirical evidence on the pandemic’s short-term consequences in Germany lent support to this suspicion. Data collected shortly after the lockdown went into effect suggested that women in Germany were indeed more likely to quit working or to reduce their hours than men (Hammerschmid et al. Citation2020; Möhring et al. Citation2020 and Kohlrausch and Zucco Citation2020 for March/April 2020; Reichelt et al. Citation2020 for May/June 2020). When childcare facilities and schools were closed in Spring and early summer in Germany, parents – in particular mothers – had to shoulder additional care responsibilities (Möhring et al. Citation2020, Kreyenfeld et al. Citation2020; Hank and Steinbach Citation2020). The question that hence arises is whether these increases in inequalities during the initial lockdown period persisted.

To answer this question, we drew on three waves of an online survey that were collected between March 23, 2020 and August 2, 2020. The survey asked a broad array of questions on individuals’ everyday experiences during the lockdown. Around 4,400 respondents aged between 25 and 54 years volunteered to participate in all three waves, including more than 2,000 respondents with children. Women were overrepresented among the respondents, along with the highly educated and individuals living in Berlin.

Our exploratory analyses of these data show that women were slightly more likely than men to either be working reduced hours or not to be working at all during the pandemic, but that parenthood was a much more important predictor. While the division of childcare was more equal in the early stages of the lockdown, mothers still carried out considerably more unpaid work than fathers. These inequalities between men and women – in particular, between mothers and fathers – may explain why we also observed greater temporary decreases in satisfaction with work, family life, and life in general among women, parents, and especially mothers. For essential workers, who are predominantly female in Germany (Koebe et al., Citation2020), we found a lower likelihood of working less during the pandemic than for employees in other occupations, whereas we found no differences in work satisfaction.

Although our data do not allow for generalizations to Germany’s entire prime-age working population, it supplements existing studies on gender and the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany that have predominantly focused on only one point in time (e.g. Kreyenfeld et al. Citation2020, Kohlrausch and Zucco Citation2020; Hank and Steinbach Citation2020). By following respondents over time and having information about their work and family life, our study focused on the dynamic development of men’s and women’s unequal involvement in paid and unpaid work during the lockdown and its successive lifting.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender inequalities in Germany

Germany, like many other countries, is characterized by a gendered division of paid and unpaid work (Altintas and Sullivan Citation2016; Hipp and Leuze Citation2015) as well as gendered occupations and economic sectors (Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2016). While differences in labour force participation rates between men and women have declined by around 10 percentage points since the 1990s, the working hours gap has remained consistently high (Hobler et al. Citation2020, p. 26). Similar inequalities exist with regard to unpaid work. Although gender differences have declined substantially over time, a recent study showed that women in Germany spend on average 100 minutes more per day on household-related tasks than men (Altintas and Sullivan Citation2016); this gap is even wider among parents (Kühhirt Citation2011). Germany’s labour market is also highly segregated by gender. Men and women are only equally represented in one third of all occupations (Dämmrich and Blossfeld Citation2016).

It was within this cultural and institutional context that COVID-19 arrived in Germany. The first case of the virus in the country was officially reported at the end of January 2020. Following a rapid increase in daily infections about a month later, a state-wide lockdown went into effect in Bavaria on 20 March and a nationwide lockdown followed two days later (Buthe et al. Citation2020; Dostal Citation2020). After 16 March, schools and day-care centres were only open to children of essential workers. Starting in mid-May, states began to gradually reopen schools and day-care centres, but when the school year came to an end, most facilities had still not resumed their regular schedules (The Local Citation2020; Unterberg Citation2020). The number of people with reduced working hours (on ‘short-time work’) peaked at 6 million in April and was still 5.4 million in June (Bundesagentur für Arbeit Citation2020). Given the gender-segregated labour market and the gendered division of paid and unpaid work, we expect that the pandemic’s social and economic consequences in Germany differ by gender. We expect that men and women differ in their likelihood of being laid off, of working reduced hours, and of having temporarily stopping working, as they tend to work in different occupations and economic sectors and may have been impacted differently by additional childcare and household duties. As the latter applies mainly to parents, inequalities between parents and non-parents may have emerged as well, and parents may be more affected by changes in gender inequalities than non-parents.

The two aforementioned scenarios of opposing gender effects of the pandemic – more gender equality vs. less gender equality – are both theoretically plausible. In theory, the pandemic may have affected male- and female-dominated economic sectors and occupations differently. Furthermore, different theoretical approaches, such as those focusing on time availability, economic exchange, and ‘doing gender’, vary in their predictions of how parents may have distributed the additional childcare and home-schooling responsibilities during nationwide lockdowns.

Arguments positing that the pandemic would lead to more gender equality build on the observation that women are overrepresented in jobs that have been less affected by the crisis. In Germany, women make up around 60 percent of ‘essential workers’ (Koebe et al. Citation2020) but only around one third of self-employed people (Hobler et al. Citation2020). While ‘essential workers’ tend to have more job security than workers in other occupations due to their importance in providing basic social services, self-employed people have been hit particularly hard by the crisis (Bünning et al. Citation2020). Moreover, when men have additional time available (Coverman Citation1985) – as they have had during the pandemic due to working from home and reduced working hours – they may take on a greater share of unpaid work. This effect may be especially salient among parents who have to shoulder additional childcare.

Arguments positing that the pandemic would lead to less gender equality rely on the evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic – in contrast to previous economic crises – has severely affected female-dominated sectors such as hospitality and retail (Hammerschmid et al. Citation2020); they also hypothesize that women may have taken on the majority of the additional childcare responsibilities. Economic exchange approaches (Becker Citation1993; Blood and Wolfe Citation1978) suggest that couples may follow a traditional gendered division of labour when deciding on who focuses on paid work and who takes on the additional childcare burden because men in Germany tend to earn higher wages than women. ‘Doing gender’ approaches (West and Zimmerman Citation1987) suggest that even in instances where women earn as much as or more than their male partners, they may still take on a greater share of childcare and household duties to enact and maintain gender identities. We therefore may not observe greater gender equality in unpaid work in cases where women took on the role of main breadwinner during the pandemic, or where the male partner was working from home. Given the deeply gendered cultural norms of motherhood and fatherhood, parents may be affected more severely than non-parents.

To examine the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for gender inequalities in Germany, we first explore differences in the likelihood of working less (which includes working reduced hours and taking temporary leaves of absence) and working from home by gender, parenthood status, and being an essential worker. In a second step, we examine how the additional childcare burden during lockdown affected the gendered division of both housework and childcare tasks. Third, as changes in paid and unpaid work were likely to have been accompanied by changes in subjective well-being, we examine changes in satisfaction with work, family life, and life in general.

Data and methods

In our empirical analyses, we drew on three waves of a non-probability online survey dealing with individuals’ everyday experiences during the COVID-19 lockdown period in Germany. Participants in the study were recruited through email lists, newspaper announcements, and instant messenger services. The first wave of data collection (t1) took place from 23 March to 10 May 2020 (N = 14,754); this first survey also included questions assessing respondents’ pre-pandemic living and working situations and subjective well-being (t0).Footnote1 The launch of survey waves 2 (t2) (N = 7573, 20 April 2020 to 14 June 2020) and wave 3 (t3) (N = 6397, 3 June 2020 to 2 August 2020) coincided with the gradual lifting of lockdown restrictions.Footnote2

Our analytical sample included respondents aged 25 to 54 who participated in all three survey waves. Of the 4,429 respondents in our sample, 3391 were female, 2,265 had at least one child living with them in the same household in wave 1; 3,577 had a tertiary degree, 3928 had a paid job before lockdown; and 1191 lived in Berlin, where the survey was initially launched. Due to the selectivity of our sample, the findings are of limited generalizability (Kohler et al. Citation2019).

To assess gender inequality during the pandemic, we examined several outcomes: (a) working-time reductions in response to the pandemic (‘yes’ if the respondent was working less than before the pandemic or was temporarily not working at all but had not been laid off),Footnote3 (b) working from home among those who were still working (yes/no), (c) the division of housework and childcare tasks in couples (two 5-point ordinal variables drawn from the German Panel Analysis of Intimate Relationships and Family Dynamics, which distinguish among the categories ‘I do all/most of the work’, ‘equal sharing between partners’, and ‘my partner does all/most of the work’), and (d) satisfaction with work, family life, and life in general (adapted from the German Socio-Economic Panel, measured on a 7-point Likert scale).

In our exploratory analyses, we applied different regression analyses to the pooled sample and interacted all covariates with time point. The panel structure of our data allows us to explore changes in all of our four outcome variables over time and thus enables comparisons between the time before (t0) and shortly after the lockdowns (t1), as well as after a certain adaptation period and an increasing loosening of the lockdowns (t2, t3). We employed logistic regressions to assess reductions in working time and in the likelihood of working from home, and OLS regressions to analyse the division of housework/childcare and satisfaction variables (see Nitsche and Grunow (Citation2018) for a similar approach on the division of labour in couples, and Treas et al. (Citation2011) for analyses of satisfaction). Robust, clustered standard errors were estimated in all regressions.

To account for the fact that our data stem from a non-probability sample, we focused on differences by gender, parenthood, and partner constellations after adjusting for a broad range of covariates. In the current analyses, we also refrain from using calibration weights for two reasons. First, the covariate adjustment in our multivariate regressions already reduces the bias in the distribution of socio-demographic characteristics in our sample. Second, weights cannot account for the respondents’ self-selection into our survey, which may be related to their time, motivation, and network affiliations and would therefore potentially and unnecessarily lead to a less cautious interpretation of our findings.

The main independent variables in our analyses were the respondent’s gender (male (reference), female), their family situation (childless with partner (reference); childless single; partnered parent; single parent), and for employment-related outcomes employment as an essential workers (yes/no).Footnote4 In addition, we included the following covariates: age (25–34, 35–44, 45–54 years), migration background (none, first generation, second generation), education (tertiary vs. non-tertiary education), subjective assessment of the household’s financial situation (living comfortably, getting by, difficulties getting by/barely coping), apartment size relative to household size (overcrowded, adequate, more than adequate), geographic region (North, South, East, West), community size (50,000 inhabitants or more, less than 50,000 inhabitants).

When analysing working time reductions, working from home, and work satisfaction, we also included some additional covariates: employment as an essential worker (yes/no),Footnote5 economic sector (seven groups), pre-pandemic working hours (part-time (<=37 hours/week), full-time (>37 hours/week)), and contract situation (permanent contract, fixed-term contract, self-employed). When we analysed the division of both housework and childcare – which we only did for partnered respondents with children – we also included information about the partner’s education, the couple’s work situation (7 categories distinguishing employment situation and work location), and same-sex relationships. In the analyses of satisfaction with family life and life in general, respondents’ employment status (yes/no) was included as an additional covariate. Appendix A provides an overview of all variables used in the analyses and the sample distributions.

Findings

To assess gender differences in paid work in response to the pandemic and whether parenthood and working in essential occupations might explain such differences, we first examined individuals’ likelihood of working less. shows that women in our sample were slightly more likely than men to report reduced working hours over the entire observation period (3–4 percentage points). Essential workers were less likely to work less than workers in other occupations. Both partnered and single parents were considerably more likely to work less than childless respondents, although the difference declined slightly over time (from 18 to 9 percentage points for partnered parents and from 13 to 6 percentage points for single parents). When we restricted the sample to parents, we found that mothers had a higher likelihood than fathers of working less, and this likelihood increased over time (from 4 to 7 percentage points, see Appendix B). Although reductions in working hours during the lockdown could be attributed to many factors, this result provides some initial evidence of the pandemic’s unequal effects on men and women and underscores the importance of parenthood as a key driver of increased inequality (for similar findings see Kohlrausch and Zucco Citation2020; Möhring et al. Citation2020 on the early lockdown period).

Table 1. Probability of working less during the pandemic.

Regarding the likelihood of working from home, it appears that workplace and job characteristics were more decisive than childcare needs (see Möhring et al. Citation2020 for similar findings). While essential workers were considerably less likely than other workers to work from home (), we only observe slight differences by gender and family status. Even when we restricted the sample to parents, we still found no considerable differences between mothers and fathers (Appendix C).

Table 2. Probability of working from home during the pandemic.

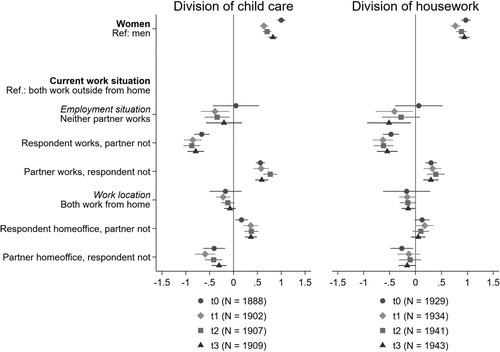

The results of our analyses of the division of childcare and housework between parents are presented in . Values on the right-hand side of the coefficient plot indicate that respondents in the specified category spent more time on childcare or housework than the reference category and vice versa for values on the left-hand side. The figure shows that women spent more time on both housework and childcare before and during the pandemic than men. While respondents reported a more equal sharing of childcare tasks during the early lockdown period (t1), this trend towards more equality decreased again over time (t2 and t3). Moreover, the unequal pre-pandemic distribution of housework (shown by Stenpaß and Kley Citation2020, for example) remained largely unchanged. These findings align closely with those of other studies on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for couples’ division of unpaid work (Kohlrausch and Zucco Citation2020; Hank and Steinbach Citation2020; Kreyenfeld et al. Citation2020 for Germany and Fodor et al. Citation2020 for Hungary) and lend support to doing-gender approaches (West and Zimmerman Citation1987) rather than to time availability approaches (e.g. Coverman Citation1985).

Figure 1. The figure presents coefficients of OLS regressions with clustered, robust standard errors. The dependent variables are division of child care and division of housework measured in all three waves (t1 to t3). In the first wave, respondents also retrospectively assessed their division of unpaid labour before the pandemic (t0). The variable is measured on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘(Almost) exclusively my partner’ to ‘(Almost) exclusively me’. The following covariates were included in the analyses: age, migration background, respondent’s and partners’ education, household income, apartment size, community size and same-sex relationship. All models were fully interacted with the time point of the survey. Stata’s coefplot command (Jann 2014) was used to generate the figure. The number of observations slightly vary from wave to wave due to item-nonresponse.

also differentiates among different work constellations and indicates that the unequal distribution of childcare and housework varied according to partners’ current working status and work location. If only one partner was in paid work, that partner performed less unpaid work than the partner who was not working. Furthermore, if one partner worked from home and the other partner outside the home, the partner working from home did slightly more unpaid work. Additional analyses (Appendix D) show that these patterns were similar for both genders. In contrast to what is stated above, this finding speaks in favour of time availability (Coverman Citation1985) and household specialization/bargaining approaches (Becker Citation1993; Blood and Wolfe Citation1978).

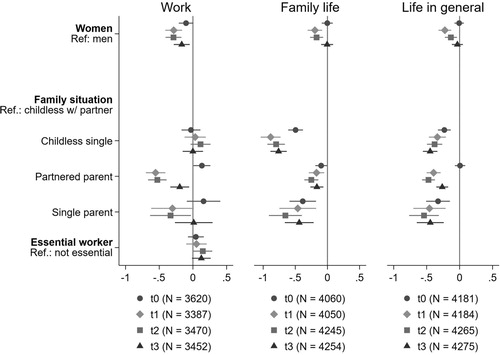

We now turn to the findings on satisfaction with work, family life, and life in general. As the pandemic and the associated lockdown have been found to have different consequences by gender and parenthood, it is likely that the subjective well-being among these groups also developed differently during the lockdown (e.g. see Czymara et al. Citation2020 on women’s increased mental load during the pandemic or Minello et al. Citation2020 on the professional worries of female academics). shows the differences in satisfaction by gender and family situation. When asked to assess their satisfaction retrospectively, women indicated that they were slightly less satisfied with their work than men before the pandemic (t0); there were no gender differences in men’s and women’s satisfaction with family life and life in general in the pre-pandemic period. Particularly during the early lockdown period (t1), women’s satisfaction with their work, their family life, and life in general was considerably lower than men’s. With the gradual lifting of the lockdown, however, men’s and women’s satisfaction with family life and life in general converged again (t2 and t3). Women’s satisfaction with work, however, remained lower than men’s even in the last survey wave (June to August 2020). We observe no differences in work satisfaction between respondents in essential occupations and those in other occupations.

Figure 2. The figure presents coefficients of OLS regressions with clustered, robust standard errors. The dependent variables are satisfaction with work, family life and life in general on a 7-point scale measured in all three waves (t1 to t3). In the first wave, respondents also retrospectively assessed their satisfaction in all three domains before the pandemic (t0). The following covariates were included in the analyses: age, migration background, respondent’s education, household income, apartment size and community size; the analyses for satisfaction with work further included contract type, pre-pandemic working hours, home office and industry; the analyses of family life and life in general also included employment status as an additional covariate. All models were fully interacted with the time point of the survey. Stata’s coefplot command (Jann 2014) was used to generate the figure. The number of observations slightly vary from wave to wave due to item-nonresponse.

For the pre-pandemic period, both partnered and single parents reported higher levels of work satisfaction, lower family satisfaction, and similar levels (partnered parents) or lower levels (single parents) of life satisfaction compared to partnered, childless individuals. During the pandemic, however, their satisfaction with all three domains was considerably lower than that of childless partnered people, although differences decreased to some extent towards the end of the lockdown period (t3) and the coefficients for single parents have large confidence intervals (presumably due to small case numbers). Singles without children also experienced greater decreases in satisfaction with family life and life in general than partnered, childless individuals.

Additional analyses (Appendix E) show no substantial differences in mothers’ vs. fathers’ satisfaction with work, family life, or life in general prior to the pandemic (t0). Mothers reported lower levels of satisfaction with all three life domains at the outset of the lockdown (t1). While they continued to report lower work satisfaction than fathers throughout the observation period, their family satisfaction and life satisfaction converged to pre-pandemic levels towards t3.

Conclusions

To explore the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for gender inequality, this paper drew on data collected from around 4,400 participants in an online survey in Germany, which asked about individuals’ working and family lives at the beginning, middle, and end of the lockdown. Our analyses show that women had a slightly higher likelihood of working less throughout the lockdown period. Yet, essential workers, who are predominantly female (Koebe et al. Citation2020) had a lower likelihood than employees in other occupations to be working less than before the lockdown. During lockdown, parents were considerably more likely than childless people to be working less than before, with differences between mothers and fathers widening towards the end of lockdown. The likelihood of working from home was only weakly related to gender and parenthood, whereas respondents in essential occupations were considerably less likely to work from than those in other occupations.

Moreover, we found that, despite slight changes in how parents divided the additional childcare, mothers still did considerably more unpaid work during the lockdown than fathers. The division of housework appears not to have changed over the course of the crisis. This might be one reason for our observation that women, in particular mothers, were less satisfied with work, family life, and life in general than men at the beginning and middle of the lockdown period, and why lower satisfaction with work remained even towards the end of the lockdown.

In conclusion, our analyses suggest an increase rather than a reduction in gender inequalities in Germany during the pandemic but we also see considerable temporal dynamics. Parenthood seems to have been driving these increases in inequalities. We need to underscore, however, that our findings are based on an online non-probability survey, which means that our respondents deviate from the German population in observable characteristics (e.g. age, education, and gender) but also in unobservable characteristics (e.g. time and the motivation to participate in a survey). Our exploratory analyses can therefore only provide a first impression and should be used in combination with studies that are based on probability samples, such as the German Socio-Economic Panel (Kreyenfeld et al. Citation2020) or the pairfam family panel (Hank and Steinbach Citation2020). The combination of ‘representative’ data and data that capture changes over time in detail, as is the case in our survey, may be useful in assessing the dynamic development of gender inequalities over the course of the pandemic.

REUS-2020-0096-File007.docx

Download MS Word (227 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Stefan Munnes, Armin Sauermann, Editor Yuliya Kosyakova, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lena Hipp

Lena Hipp is head of the research group ‘Work & Care’ at WZB Berlin Social Science Center and Professor of Sociology at the University of Potsdam. Her research focuses on different aspects of social inequality, in particular work, family, gender, and organizations. Her work has been published in Social Forces, European Sociological Review, Socio-Economic Review, Journal of Marriage and Family, and Work and Occupations.

Mareike Bünning

Mareike Bünning is senior researcher in the research group ‘Work & Care’ at WZB Berlin Social Science Center. She is interested in social inequalities in paid and unpaid work and how these are shaped by workplace organizations and public policies. Her work has appeared in European Sociological Review, Journal of Marriage and Family, and Work, Employment and Society.

Notes

1 We acknowledge that retrospective questions risk inaccurate response behaviors, but have sought to reduce such biases by providing respondents with short and easy-to-understand questions that referred to a time around a specific anchor point (the pre-pandemic period) shortly (2-6 weeks) before data collection (Hipp, Bünning, et al., 2020).

2 Data, codebook, and syntax for data cleaning are available at https://doi.org/10.7802/2042. The replication files for this paper are available at https://osf.io/wye69/.

3 We could not analyze gendered risks of job loss, as the number of cases who had lost their job due to the pandemic was too small (n = 28 across all three waves).

4 Respondents in the survey were asked whether they worked in a job that was classified as ‘essential’. The answering categories for this question contained the seven occupational groups that have been listed by Germany’s governing authorities as occupations that qualified for access to emergency childcare (e.g., police, fire brigade, public transport, utilities, waste disposal, healthcare, nursing, childcare, groceries, and drugstores).

5 Respondents chose from a list of sectors that were deemed to be essential by state governments. The list was compiled using guidelines for emergency childcare that were published by the states in March (see Koebe et al. Citation2020).

References

- Altintas, E. and Sullivan, O. (2016) ‘Fifty years of change updated: cross-national gender convergence in housework’, Demographic Research 35: 455–470.

- Becker, G. S. (1993) A Treatise on the Family, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Blome, A. (2016) The Politics of Work-Family Policy Reforms in Germany and Italy, London/New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Ltd.

- Blood, R. O. and Wolfe, D. M. (1978) Husbands & Wives: The Dynamics of Married Living, Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2020) Auswirkungen der Corona-Krise auf den Arbeits- und Ausbildungsmarkt.

- Bünning, M., Hipp, L. and Munnes, S. (2020) Erwerbsarbeit in Zeiten von Corona. WZB Ergebnisbericht, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Buthe, T., Messerschmidt, L. and Cheng, C. (2020) Policy responses to the coronavirus in Germany. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L. and Scarborough, W. J. (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours’, Gender, Work & Organization 7 Early View: 1–12.

- Coverman, S. (1985) ‘Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor’, Sociological Quarterly 26: 81–97.

- Czymara, S., Langenkamp, A. and Cano, T. (2020) ‘Cause for concerns: gender inequality in experiencing the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany’, European Societies Early View: 1–14.

- Dämmrich, J. and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2016) ‘Women’s disadvantage in holding supervisory positions. Variations among European countries and the role of horizontal gender segregation’, Acta Sociologica 60: 262–282.

- Dostal, J. M. (2020) ‘Governing under pressure: German policy making during the coronavirus crisis’, The Political Quarterly 91: 542–552.

- EIGE (2018) Study and Work in the EU Set Apart by Gender, Vilnius: European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fodor, É, Gregor, A. and Koltai, J. (2020) ‘The impact of COVID – 19 on the gender division of childcare work in Hungary’, European Societies Early View: 1–16.

- Hammerschmid, A., Schmieder, J. and Wrohlich, K. (2020) ‘Frauen in Corona-Krise stärker am Arbeitsmarkt betroffen als Männer’, DIW Aktuell 42: 5.

- Hank, K. and Steinbach, A. (2020) ‘The virus changed everything, didn’t it? Couples’ division of housework and childcare before and during the Corona crisis’, Journal of Family Research Early View: 1–16.

- Hipp, L., Bünning, M., Munnes, S. and Sauermann, A. (2020) ‘Problems and pitfalls of retrospective survey questions in COVID-19 studies’, Survey Research Methods 4: 2.

- Hipp, L. and Leuze, K. (2015) ‘Institutionelle Determinanten einer partnerschaftlichen Aufteilung von Erwerbsarbeit in Europa und den USA’, KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 67: 659–684.

- Hobler, D., Lott, Y., Pfahl, S. and Buschoff, K. S. (2020) Stand der Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern in Deutschland, Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut WSI Report 56: 1–50.

- Hoenig, K. and Wenz, S. E. (2020) ‘Education, health behavior, and working conditions during the pandemic: evidence from a German sample’, European Societies Early View: 1–14.

- Koebe, J., Samtleben, C., Schrenker, A. and Zucco, A. (2020) ‘System relevant, aber dennoch kaum anerkannt: Entlohnung unverzichtbarer Berufe in der Corona-Krise unterdurchschnittlich’, DIW Aktuell 48: 6.

- Kohler, U., Kreuter, F. and Stuart, E. A. (2019) ‘Nonprobability sampling and causal analysis’, Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 6: 149–172.

- Kohlrausch, B. and Zucco, A. (2020) Die Corona-Krise trifft Frauen doppelt. Weniger Erwerbseinkommen und mehr Sorgearbeit. Policy Brief WSI, 5: 40.

- Kreyenfeld, M., et al. (2020) Coronavirus & care: how the coronavirus crisis affected fathers’ involvement in Germany. SOEP papers 1096.

- Kühhirt, M. (2011) ‘Childbirth and the Long-term division of labour within couples: how do substitution, bargaining power, and norms affect parents\textquotesingle time allocation in West Germany?’, European Sociological Review 28: 565–582.

- Minello, A., Martucci, S. and Manzo, L. K. C. (2020) ‘The pandemic and the academic mothers: present hardships and future perspectives’, European Societies Early View: 1–13.

- Möhring, K., et al. (2020) Die Mannheimer Corona-Studie: Schwerpunktbericht zu Erwerbstätigkeit und Kinderbetreuung, Universität Mannheim, Working Paper: Mannheim.

- Nitsche, N. and Grunow, D. (2018) ‘Do economic resources play a role in bargaining child care in couples? Parental investment in cases of matching and mismatching gender ideologies in Germany’, European Societies 20: 785–815.

- Reichelt, M., Makovi, K. and Sargsyan, A. (2020) ‘The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes’, European Societies Early View: 1–27.

- Rosenfeld, R. A., Trappe, H. and Gornick, J. C. (2004) ‘Gender and work in Germany: before and after Reunification’, Annual Review of Sociology 30: 103–124.

- Stenpaß, A. and Kley, S. (2020) ‘It’s getting late today, please do the laundry: the influence of long-distance commuting on the division of domestic labor’, Journal of Family Research 32: 274–306.

- The Local (2020) State by state: when are schools and Kitas around Germany reopening?

- Treas, J., van der Lippe, T. and ChloeTai, T.-O. (2011) ‘The happy homemaker? Married women’s well-being in cross-national perspective’, Social Forces 90: 111–132.

- Unterberg, S. (2020) German States Move To Close Educational and Daycare Facilities, Spiegel International, Hamburg.

- van Dorn, A., Cooney, R. E. and Sabin, M. L. (2020) ‘COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US’, The Lancet 395: 1243–1244.

- West, C. and Zimmerman, D. H. (1987) ‘Doing gender’, Gender and Society 1: 125–151.