ABSTRACT

Whilst the Covid-19 pandemic affects all European countries, the ways in which these countries are prepared for the health and subsequent economic crisis varies considerably. Financial solidarity within the European Union (EU) could mitigate some of these inequalities but depends upon the support of the citizens of individual member states for such policies. This paper studies attitudes of the Austrian population – a net-contributor to the European budget – towards financial solidarity using two waves of the Austrian Corona Panel Project collected in May and June 2020. We find that individuals (i) who are less likely to consider the Covid-19 pandemic as a national economic threat, (ii) who believe that Austria benefits from supporting other countries, and (iii) who prefer the crisis to be organized more centrally at EU-level show higher support for European financial solidarity. Using fixed effects models, we further show that perceiving economic threats and preferring central crisis management also explain attitude dynamics within individuals over time. We conclude that cost–benefit perceptions are important determinants for individual support of European financial solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The Covid-19 crisis – such as the global financial crisis or the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis – is a major shock spreading unevenly and with varying intensity in different parts of Europe. Similarly, the ways in which countries, regions, and individuals prepare for and respond to this health and subsequent economic crisis varied. Pre-existing economic and social inequalities between countries in the European Union are considered to be an important reason for this strong variation in countries’ ability to cope with this crisis. Such pre-existing inequalities may be reinforced or even widened by the Covid-19 pandemic. To reduce such inequalities, the 27 EU member states agreed upon a 750 billion Euro recovery fund consisting of loans as well as grants to jointly combat the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic (European Council Citation2020).

This recovery fund is based on a number of proposals. Among these, a Franco-German proposal (Bundesregierung Citation2020) which was considered ground-breaking since it included a proposal for joint debt-issuing and proposed that large parts of the fund should not be provided as loans but rather as grants. Such measures towards a stronger Europeanization of financial solidarity have so far been rejected by Germany and other financially well-positioned member states. Unlike Germany and France, the so-called ‘frugal four’ consisting of Austria, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, (later joined by Finland) continue to advocate for loans instead of grants and strong conditionality on the provision of funds.

As past research has shown, public opinion is a potentially important factor to be considered when studying EU politics (Hix Citation2018; Mühlböck and Tosun Citation2018). Hence, whether a recovery fund will succeed in fostering European economic solidarity in the long run, depends on the question to what extent the citizens of the individual member states support instruments of financial solidarity. In this context, Austria as a net-contributor country and member of the ‘frugal four’ is a crucial case since the political debates across Europe were structured along the new cleavage of advocates and adversaries of further economic integration within net-contributor countries. This paper studies attitudes of the Austrian population towards three instruments of financial solidarity, namely (1) issuing joint EU-debt, (2) higher member state contributions, and (3) a joint fund to issue loans. To do so, we utilize data of the Austrian Corona Panel Project fielded ahead of the start of the debate in early May and after the publication of the main policy proposals end of June.

The paper is structured as follows: We first review related research and develop our theoretical argument. Then, we describe the empirical data and method. In the following section, we provide descriptive as well as regression results. The paper closes with a short discussion and conclusion.

Reviewing existing literature: attitudes towards European financial solidarity

Determinants of citizen’s attitudes towards EU integration are studied from a variety of perspectives. Three major explanatory approaches can be differentiated in explaining varying support for European financial solidarity (cf. Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016). First, research focusing on material self-interest argues that support for European financial solidarity depends on perceived cost–benefit analyzes (Gabel and Palmer Citation1995). Second, identity arguments claim that a national sense of belonging (Hooghe and Marks Citation2004; Banducci et al. Citation2009) and cultural values such as cosmopolitanism (Bechtel et al. Citation2014) are crucial. A third strand focusses on elite (e.g. party) or institutional (perceived levels of corruption or institutional quality) cues and states that voters often follow examples of others in their decision regarding support for financial assistance (Bauhr and Charron Citation2018, Citation2020; Stoeckel and Kuhn Citation2018).

Previous empirical results have shown that all three mechanisms matter – albeit in varying degrees depending on factors such as the national context (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016) or the saliency of EU topics (Garry and Tilly Citation2009; Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Hix Citation2018). Recently, the economic crisis increased public visibility of the European economic integration which resulted in an increasingly important role of public opinion for EU-level policy making (Grande and Kriesi Citation2015). Hobolt and Wratil (Citation2015) show that, in such a high-saliency context, variables following a cost–benefit argumentation are better equipped than identity concerns to explain support for European economic integration. They interpret this result as an important indicator that economic crises may prime citizens to employ a ‘self-interest logic’ rather than an ‘identity logic’. Similar in reasoning, we argue that the Covid-19 crisis and subsequent debates about financial solidarity may prime citizens to adapt a self-interest logic. Hence, we focus on the question to what extent cost–benefit concerns explain attitudes towards financial solidarity during the Covid-19 crisis. However, we try to account for alternative explanations by controlling for national identity and political partisanship.

Several studies have shown that national economic performance is a prominent predictor of citizens’ attitudes towards European integration and EU support (Magni-Berton et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2020) show that individuals in countries that perform less well economically, are less likely to support financial assistance to other member states. As the Covid-19-crisis highlights the limitations of financial and economic resources, we argue that not only differences in attitudes to financial solidarity across countries but also within a country depend on national cost–benefit considerations. As individuals differ in their perceptions of the potential economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on national economies, so should their attitudes regarding the affordability of financial assistance. Hence, we expect:

(H1) Individuals who are less likely to consider the Covid-19 pandemic as a national economic threat show higher support for European financial solidarity.

Considerations of self-interest should not only depend on the context of national affordability but also on individual perceived cost–benefit evaluations of European financial solidarity itself. Recent research has shown that this perspective seems to be especially productive in explaining integration in trade (McLaren Citation2002, Citation2006), monetary integration (Banducci et al. Citation2009) or support for the Euro (Gabel and Hix Citation2005; Walter Citation2013). Using a survey experiment, Baccaro et al. (Citation2020) show that exposing Italians to information about the conditionality associated with a bailout package increases preferences for exiting the Euro. Their results suggest that support for the Euro relies heavily on the perception of having benefited from it providing evidence that individuals follow weak reciprocity norms (Bowles and Gintis Citation2000). Following these findings, we hypothesize that individuals grant financial solidarity conditional on expected long-term benefits:

H2: Individuals who believe that Austria benefits from helping other countries are more likely to support European financial solidarity.

H3: Individuals who prefer the crisis to be organized more centrally at the level of the European Union tend to show higher support for European financial solidarity.

We test these hypotheses on three potential instruments of European financial solidarity: (1) higher member state contributions, (2) issuing joint EU-debts, and (3) a joint fund to issue loans. To study the determinants of financial solidarity, we utilize panel survey data before and after the announcement of all major policy proposals on financial solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic at the EU-level. This enables us to study potential causal mechanisms as we are not only looking at citizens’ preferences at one point in time but investigate how changes in attitudes affect participants’ attitudes in times of ongoing political debates.

Data and method

As data source, we use two waves of the Austrian Corona Panel Project (ACPP): A weekly online panel survey with a sample size of approximately 1,500 respondents per wave (Kittel et al. Citation2020a). The sample drawn from a commercial open access panel closely resembles Austrian population in the distribution of gender, age, education employment status, migration background and region (for further details on design, accuracy, content, and data access see (Kittel et al. Citation2020b)). We use a question module which was first fielded between 8 and 13 May 2020, before the Franco-German proposal started major debates on the European crisis management during the Covid-19 pandemic. Data for the second wave was collected between 26 June and 1 July 2020, after all major proposals on potential instruments for a European response had been published.

To measure support for EU financial solidarity we utilize a question battery that asked respondents to state their support for three different crisis financing instruments: (1) higher member state contributions, (2) issuing joint EU-debts, (3) joint fund to issue loans.Footnote1 The exact wording of the question can be found in the appendix.

To study the impact of utility considerations, we analyze individuals with different attitudes towards (i) the economic impact of Covid-19 on Austria’s economy, (ii) the potential profits of helping others in dealing with this economic crisis, and (iii) the role of the EU in crisis management. We operationalize the potential profits of helping others by agreement to the statement ‘Austria benefits in the long term from providing financial support to other EU-countries.’ and crisis management on EU level by the agreement to the following statement: ‘In the future, the fight against transnational crises should be managed more centrally by the EU.’ To study the effect of different perceptions of the economic impact of Covid-19 on Austria’s economy we utilize the question: ‘How great do you estimate the economic danger posed by the coronavirus to the Austrian population?’. All items are answered on a 5-point-Likert scale. We further control for fairness norms (need, equity, equality) (e.g. Hülle et al. Citation2018), attachment towards Europe vs. Austria as a proxy for the degree of national identity, employment status, gender, age, level of education, respondent’s perceived financial satisfaction, and party vote in the 2019 national election (see Appendix with a list of the specific items and the respective question wording).

We employ listwise deletion for missing values. To test whether this distorted our dataset, we provide comparisons between the full sample of respondents in May and the reduced sample of those who participated in both waves (in May and June) in in the appendix. Using chi-squared tests we do not find significant differences in any of the wave/variable pairs of the dependent variables. We estimate pooled ordinary least squares (POLS) as well as fixed effects (FE) regression models which eliminate potential biases due to omitted, time-invariant factors by focusing on variation within individuals (Allison Citation2009).

Table 1. POLS and FE on three instruments for financial solidarity.

Analysis

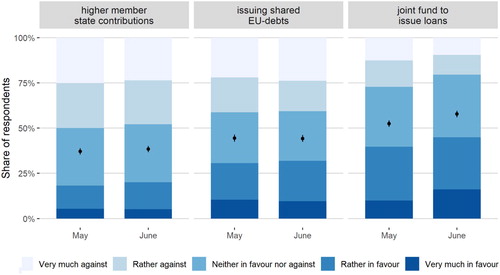

shows support of the Austrian population for three different instruments of financial solidarity for two time periods (mid of May and end of June 2020). In May, on average, the Austrian population supports the proposal of higher member state contributions the least (18% very much or rather in favor). Around 31% support issuing joint EU-debts and around 40% support a joint fund to issue loans.Footnote2 Hence, none of the instruments is supported by a majority of the respondents. A large portion of the respondents, however, avoided stating a distinct position by neither favoring nor opposing the different instruments for European financial solidarity. These results are in line with other studies that report high rates of neutral or avoiding answers in the context of support for programs of European fiscal solidarity (Beetsma et al. Citation2020) or support for the Euro in general (Baccaro et al. Citation2020). However, questions for support for different programs for financial solidarity could produce different patterns of missing or neutral answers depending on the exact wording. We test these patterns with regard to respondents’ socio-economic characteristics in the appendix. While we find that older, more educated, and male individuals are more likely to avoid missing or indecisive answers, these patterns are quite similar across all items measuring financial solidarity.Footnote3

Figure 1. Attitudes towards different financial solidarity instruments.

Source: Austrian Corona Panel Project (including voluntary fund without payment obligation and voluntary in-kind donations).

Though several proposals – such as the Franco-German proposal, the response of the ‘frugal four/five’, and the proposal of the European Commission – have been published between the two waves and were also widely covered in the Austrian media, we do find, on average, very little variation across time. Only the support for the proposal for a joint fund to issue loans increased significantly (t = 4.82, p < .001) between May and June 2020. This limited variation over time is also resembled within individuals as about half of the respondents choose similar answers in both survey waves (refer to appendix Table 3 for specific estimates on within individual variation).

shows the regression analyzes for our three dependent variables, namely, issuing joint EU-debts, higher member state contributions to the EU-budget, and a joint fund to issue loans. In the POLS models, all three utility indicators are significantly associated with the financial solidarity proposals studied here. These associations are in line with our hypotheses. Individuals who prefer EU-centralized crisis management report on average between 0.14 and 0.21 points (p < .001) higher support for joint debt-issuing, higher state contributions, or a fund that issues loans. Individuals who believe that Austria benefits from helping others report an on average between 0.17 and 0.34 points (p < .001) higher support for these financial solidarity instruments. Perceiving Covid-19 as an economic threat, is negatively associated with proposals of financial solidarity, although its effect is smaller with coefficients varying between −.04 and −.11 and is not always statistically significant. The POLS model further controls for identity and partisanship to avoid confounding from other explanations of support for European financial solidarity. We provide stepwise regression models in the appendix (Table 5). These models indicate that partisanship can only explain a limited amount of variation. In contrast, having a strong Austrian national identity is clearly detrimental to the amount of support for European financial solidarity. However, all these variables did not strongly influence the power of self-interest variables analyzed here.

Our data has a panel structure which we exploit by looking at changes over time in model (2), (4), and (6). Individuals who report a change in attitudes towards a higher preference for centralized crisis management at EU-level over time also report a higher agreement with financial solidarity in forms of joint debts or increased member state contributions. However, we do not find that the belief that Austria benefits from supporting other countries explains within-individual variation in support for financial solidarity. On the contrary, threat perceptions seem to perform well in explaining the dynamics of attitudes towards financial support especially with regard to member state contributions and a joint fund. Thus, the fixed effects results show that changes in attitudes on centralized EU crisis management and in perceived threats of the Covid-19 pandemic for the Austrian economy translate into changes in attitudes towards financial solidarity.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper studied attitudes towards European financial solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic in Austria. Utilizing POLS regressions, we find that individuals (i) who are less likely to consider the Covid-19 pandemic as an economic threat, (ii) who believe that Austria benefits from supporting other countries, and (iii) who prefer the crisis to be organized more centrally at EU-level, show higher support for European financial solidarity. Using fixed effects models, we further show that perceiving economic threats and preferring central crisis management also explain attitude dynamics within individuals between May and June 2020.

While we try to control for confounding variables by either including variables on political partisanship, identity, and fairness norms (POLS) or relying on within-individual variation (FE) only, further research is needed to better understand the exact causal mechanisms in which utility perceptions relate to financial solidarity. This relates to the challenge to operationalize cost–benefit considerations. Especially our measure for a preference to organize the crisis management more centrally at EU-level may depend upon whether individuals think the EU is a legitimate or normatively desirable actor to deal with such transnational issues. That is, it may proxy cost–benefit considerations but may further capture factors such as trust in national or European institutions or identity norms (Harteveld et al. Citation2013).

Focusing on variation over time, we find an increase in support for the joint fund solution between May and June 2020. This may be the result of a feedback effect (Steenbergen et al. Citation2007) since this proposal most closely resembles the financial solidarity instrument endorsed by the Austrian government. However, further analyzes are needed to identify the exact mechanisms at work.

Similar to results on the impact of past economic crises, such as the Euro crisis (e.g. Hobolt and Wratil Citation2015), we find that utility considerations do play a role when it comes to financial solidarity attitudes during the pandemic. Specifically, our results indicate that Austrian citizens’ support for European financial solidarity and thus further economic and fiscal integration depends on perceived cost–benefit considerations of these policies. The heightened saliency of such cost–benefit considerations and the effects of perceived economic performance on support for financial solidarity suggest that individuals living in a net-contributor country might consider financial solidarity as a form of trade-off one can only afford if one's national economy is performing well. This could potentially hinder further European economic integration if this cost–benefit framing continues to dominate debates about future European economic integration.

Country-specific contexts may be crucial. Beetsma et al. (Citation2020) show that general support for European financial solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic is substantial and argue that some cross-national variation in public support mirrors differences in the positions of governments. Especially differentiating between net-contributor and net-receiver countries may be relevant. While we find that perceived economic threats due to the Covid-19 pandemic decrease support for financial solidarity in Austria, we would argue that perceiving economic threats could increase support for financial solidarity in net-receiver countries. This also relates to issues regarding the relationship between identity and cost–benefit arguments. If we consider that both mechanisms should affect fiscal solidarity, different national contexts may shift their relative importance. For instance, identity issues may be in line with self-interest considerations in some countries while in others not: In the context of fiscal solidarity, individual concerns for self-interest might be in line with identity concerns in net-contributor countries while the opposite should be true for net-receiver countries. Thus, identity issues might stratify support for fiscal solidarity in wealthier countries (or in countries less heavily hit by Covid-19) more strongly than in less wealthier countries (Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014). Future research should thus investigate the ways in which potential determinants of individual support for European financial solidarity vary across and within countries.

REUS-2020-0152-File004.docx

Download MS Word (112.9 KB)Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, as well as Monika Mühlbock and Roland Verwiebe for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Licia Bobzien

Licia Bobzien is a is doctoral researcher at the Hertie School, Berlin and the Chair of Social Inequality and Social Structure Analysis, University of Potsdam. She is interested in the ways in which economic inequalities affect political preferences and attitudes.

Fabian Kalleitner

Fabian Kalleitner is a doctoral researcher at the Department of Economic Sociology at the University of Vienna. His current research focuses on tax preferences, biased perceptions, fairness attitudes, and work values.

Notes

1 The question further asked for attitudes towards a ‘voluntary fund without repayment obligation’, and ‘voluntary in-kind donations to EU member states’. We do not integrate these variables in the main analyses since these instruments were not publicly discussed during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, we provide results on similar calculations to those in the following section on these variables in the appendix (figure 1 and table 4).

2 This financing instrument comes closest to the position of the Austrian government.

3 For details on missing values and patterns of missing depending on sociodemographic characteristics refer to tables 1 and 2 in the appendix).

References

- Allison, P. D. (2009) Fixed Effects Regression Models, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Baccaro, L., Bremer, B. and Neimanns, E. (2020) ‘Is the Euro Up for Grabs ? Evidence from a Survey Experiment Lucio Baccaro.’ MPIfG Discussion paper 20/10.

- Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A. and Loedel, P. H. (2009) ‘Economic interests and public support for the Euro’, Journal of European Public Policy 16(4): 564–81.

- Bauhr, M. and Charron, N. (2018) ‘Why support international redistribution? Corruption and public support for aid in the Eurozone’, European Union Politics 19(2): 233–54.

- Bauhr, M. and Charron, N. (2020) ‘The EU as a savior and a saint? corruption and public support for redistribution’, Journal of European Public Policy 27(4): 509–27.

- Bechtel, M. M., Hainmueller, J. and Margalit, Y. (2014) ‘Preferences for international redistribution: the divide over the Eurozone bailouts’, American Journal of Political Science 58(4): 835–56.

- Beetsma, R., Burgoon, B., Nicoli, F., de Ruijter, A. and Vandenbroucke, F. (2020) What Kind of EU Fiscal Capacity ? Evidence from a Randomized Survey Experiment in Five European Countries in Times of Corona.

- Bobzien, L. (2020) ‘Polarized perceptions, polarized preferences? Understanding the relationship between inequality and preferences for redistribution’, Journal of European Social Policy 30(2): 206–24.

- Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (2000) ‘Reciprocity, self-interest and the welfare state’, Nordic Journal of Political Economy 26(1): 33–53.

- Bundesregierung (2020) ‘A French-German initiative for the European recovery from the coronavirus crisis’, Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung 173(20): 1–5.

- European Council (2020) Special Meeting of the European Council (17, 18, 19, 20 and 21 July 2020). Conclusions. EUCO 10/20. Brussels.

- Gabel, M. and Hix, S. (2005) ‘Understanding public support for British membership of the single currency’, Political Studies 53(1): 65–81.

- Gabel, M. and Palmer, H. D. (1995) ‘Understanding variation in public support for European integration’, European Journal of Political Research 27(1): 3–19.

- Garry, J. and Tilley, J. (2009) ‘The macroeconomic factors conditioning the impact of identity on attitudes towards the EU’, European Union Politics 10(3): 361–79.

- Grande, E. and Kriesi, H. (2015) ‘Die Eurokrise: Ein Quantensprung in Der Politisierung Des Europäischen Integrationsprozesses?’, PVS Politische Vierteljahresschrift 56(3): 479–505.

- Harteveld, E., van der Meer, T. and de Vries, C. E. (2013) ‘In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European union’, European Union Politics 14(4): 542–65.

- Hix, S. (2018) ‘When optimism fails: Liberal inter governmentalism and citizen representation*’, Journal of Common Market Studies 56(7): 1595–613.

- Hobolt, S. B. and de Vries, C. E. (2016) ‘Public support for European integration’, Annual Review of Political Science 19(1): 413–32.

- Hobolt, S. B. and Wratil, C. (2015) ‘Public opinion and the crisis: The dynamics of support for the Euro’, Journal of European Public Policy 22(2): 238–56.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2004) ‘Does identity or economic rationality drive public opinion on European integration?’, PS – Political Science and Politics 37(3): 415–20.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009) ‘A post functionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1–23.

- Hülle, S., Liebig, S. and May, M. J. (2018) ‘Measuring attitudes toward distributive justice: the basic social justice orientations scale’, Social Indicators Research 136(2): 663–92.

- Kittel, B., Kritzinger, S., Boomgaarden, H., Prainsack, B., Eberl, J.-M., Kalleitner, F., Lebernegg, N. S., Partheymüller, J., Plescia, C., Schiestl, D. W., and Schlogl, L. (2020a) ‘Austrian corona panel project (SUF Edition)’, doi:10.11587/28KQNS.

- Kittel, B., Kritzinger, S., Boomgaarden, H., Prainsack, B., Eberl, J.-M., Kalleitner, F., Lebernegg, N. S., Partheymüller, J., Plescia, C., Schiestl, D. W. and Schlogl, L. (2020b) ‘The Austrian corona panel project: monitoring individual and societal dynamics amidst the COVID-19 crisis’, SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.1057/s41304-020-00294-7.

- Kuhn, T. and Stoeckel, F. (2014) ‘When European integration becomes costly: the Euro crisis and public support for European economic governance’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(4): 624–41.

- Magni-Berton, R., François, A. and Le Gall, C. (2020) ‘Is the EU held accountable for economic performances? Assessing vote and popularity functions before and after membership’, European Journal of Political Research, 1–23.

- McLaren, L. M. (2002) ‘Public support for the European Union: cost/benefit analysis or perceived cultural threat?’, Journal of Politics, Research Notes 64(2): 551–66.

- McLaren, L. M. (2006) ‘Identity, interests and attitudes to European integration’, Identity, Interests and Attitudes to European Integration, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mühlböck, M. and Tosun, J. (2018) ‘Responsiveness to different national interests: voting behaviour on genetically modified organisms in the council of the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 56(2): 385–402.

- Steenbergen, M. R., Edwards, E. E. and de Vries, C. E. (2007) ‘Who’s cueing whom?: Mass-elite linkages and the future of European integration’, European Union Politics 8(1): 13–35.

- Stoeckel, F. and Kuhn, T. (2018) ‘Mobilizing citizens for costly policies: the conditional effect of party cues on support for international bailouts in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 56(2): 446–61.

- Vasilopoulou, S. and Talving, L. (2020) ‘Poor versus rich countries: a gap in public attitudes towards fiscal solidarity in the EU’, West European Politics 43(4): 919–43.

- Walter, S. (2013) Financial Crises and the Politics of Macroeconomic Adjustments, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.