ABSTRACT

An online survey was conducted in Germany during the lockdown period to assess its psycho-social consequences. A convenience sample N = 2009 (comparable representation of former GDR and West Germany, 71% females) took part in the survey. The results show a negative impact of the corona pandemic on subjective well-being, health and life satisfaction. We also found a lower sense of security and an increase in anxiety. Additional strains follow a social gradient: Most apparent are negative effects on people with low educational background whose general life satisfaction particularly decreased and gender-specific differences in coping with everyday life challenges, this involves in particular mothers, who have to organise childcare and home schooling more often than fathers. Again, while parents generally felt constrained by social consequences of the pandemic, mothers were particularly affected, feeling more often exhausted, nervous and insecure than fathers. However, the crisis had some positives, too: the experience of stress and exhaustion was reduced; the crisis also revealed resources, such as adaptability in dealing with the changed time situation and new opportunities for self-care. The results illustrate that in this time of crisis, the family can be both a place of resilience and retreat as well as a stress factor.

1. Introduction

Society is under tension. Only recently, buzzwords such as social inequality, globalisation or acceleration were used to describe this phenomenon. It is a new experience that the field of health, of all areas of action and policy, demonstrates how much tension societies are under. The coronavirus pandemic led to a historical caesura and is currently developing into a focal point and proving ground for late modern societies. Lines of tension, such as social, gender, generational and regional inequalities (Hans-Böckler-Stiftung Citation2020), but also the revival of the idea of solidarity or the growing criticism of the austerity policy in the health sector are being discussed anew. The coronavirus pandemic is becoming a much-discussed seismograph for questions of social justice, gender equality, health and social policy. When lines of social tension are examined, the health sociology view is particularly worthwhile: ‘Since health and society are so closely linked, we learn more about health when we study society and more about society when we study health’. (Wilkinson Citation2001: 18).

At the same time, opportunities can also arise from the radical break in everyday life: Breaks in routine and the end of an ‘always-on’ life offer new room for manoeuvre and make it possible to make thought experiments of a successful lifestyle come true, whether in the home office, in the time with friends and family or (again) to pursue hobbies more intensively, free from private or professional deadline pressure. But who is it that reinterprets this time in a positive way, uses the opportunity to practise self-care and reflect on everyday routines? What is the social status or educational background of those who emerge stronger from a crisis that is sometimes understood as ‘global’, all-encompassing and affecting everyone?

We assume that the period of the coronavirus-induced lockdownFootnote1 and its consequences, such as the closure of schools or greatly reduced contact with friends and family, had an impact on the subjective, psychosocial health of individuals in late modern societies. Factors such as socio-economic status and gender moderate the strength of the impact on subjective, psychosocial health.

2. State of research

The coronavirus pandemic is a new, unprecedented event, which is now the subject of intensive research in many scientific disciplines, whether it be the major players in virology and infectiology in university hospitals or state-affiliated institutions for disease prevention and monitoring, or the many social science and humanities research projects focusing on the social, cultural and economic impact of the pandemic.

Large quantitative panels and various institutions, such as SOEP (Socio economic panel), WSI (Institute for Economic and Social Research), WZB (Social Science Research Centre Berlin) and DIW (German Institute for Economic Research), are currently investigating the effects of the coronavirus pandemic in Germany, which, despite a general problem of comparability, often come to similar conclusions: the crisis is acting as an amplifier of social and gender inequality. However, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and the lockdown on psychosocial well-being and subjective health need to be discussed. The state of research on this is currently limited; initial results for Germany can be outlined as follows:

The respondents of the SOEP-COV Panel are more satisfied with their general health and are less concerned about it. However, the authors note that these statements were made in the light of the threat scenario of the pandemic. Although slight increases in anxiety and depression symptoms have been observed since the coronavirus pandemic, the increase in symptoms does not exceed the results of previous surveys by the same panel in 2016. However, a significant increase can be seen in the feeling of loneliness during the lockdown period. On the other hand, life satisfaction does not seem to have decreased significantly. The authors state that socioeconomic differences do not have an impact on health (Entringer et al. Citation2020).

In Germany, a representative online cross-sectional study examines health literacy in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. The participants felt well informed about the coronavirus, but 47.8% reported that they had difficulties in assessing whether they could trust the media information about COVID-19 (Orkan et al. Citation2020). Health literacy empowers people to make informed health choices and to adopt healthy and protective behaviours during the time of the coronavirus pandemic (ibid.).

Another survey shows that there is a clear link between household income, financial worries and income losses, and people with lower household incomes are much more affected by the consequences of the pandemic (Hövermann Citation2020). Moreover, during the lockdown period, people with completed vocational training were more likely to not be working at all than academics. The same applies to people without a completed vocational education and training compared to academics (Bünning et al. Citation2020). People with higher education qualifications were better able to cope with the crisis due to their resources (Schröder et al. Citation2020). Among the people who can do home office work there are many people with higher education who can better protect themselves against infection through the home office and have had less severe income losses. For example, employees with a lower level of education are affected by short-time work much more frequently (ibid.). This indicates at least a short – or medium-term increase in social inequality due to the coronavirus pandemic (Hövermann Citation2020).

The intensification of gender-specific differences has already been demonstrated in various studies in Germany. A significant difference between men and women in terms of financial worries and burdens as well as salary losses can be identified; not only do women have to increasingly bear the burden of childcare (Blom et al. Citation2020), they are also affected by salary losses and once again exposed to a double burden (Hövermann Citation2020). It was also more often mothers who adjusted their working hours for childcare during the pandemic (Bünning et al. Citation2020).

The coronavirus pandemic also put to the test the trust in governmental institutions, science, etc. as well as solidarity and social cohesion. Previous research results paint a positive picture here. Although the coronavirus pandemic created new needs for help, it also created support arrangements that helped to support risk groups such as older people (Bertogg and Koos Citation2020). Research results also show that people's trust in each other has increased and that there is general satisfaction with government crisis management (Kühne et al. Citation2020). Orkan et al. (Citation2020) point to feelings of being overburdened, even an ‘infodemic’ in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic; this refers to an overabundance of valid and invalid information, which makes it difficult for the people to distinguish between reliable and unreliable information and to practise protective behaviour (ibid.).

3. Theoretical framework

The concept of subjective health has proven itself in previous health science research, as it takes into account self-assessed health and thus takes subjective well-being into account. There is often a gap between objective medical findings and personal experience. Despite a diagnosis of illness, people can feel well and their social participation may be hardly effected. Conversely, people without objective illnesses or with apparently less serious diagnoses can feel heavily burdened and their well-being impaired. The self-assessment of one's own state of health has been used internationally for years to record subjective health in population studies (Robert-Koch-Institut [RKI] Citation2009) and is also considered a suitable indicator for the objective state of health of the respondents and has proven to be meaningful for the use of health services in longitudinal studies (RKI Citation2009).

It is assumed that health self-assessment also moderates the motivation for changing health-risk behaviour styles. The self-perceived state of health also allows conclusions to be drawn about active participation and the chances of participation in social life and provides an impression of how stress is processed and experienced (Idler and Benyamini Citation1997; DeSalvo et al. Citation2006).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) highlights the central importance of the distinction between objective and subjective well-being in its studies (WHO Citation2012: 121). Objective well-being refers first and foremost to the living conditions of people and their chances of achieving their greatest possible potential for health. Subjective well-being, on the other hand, is linked to actual life experiences and, building on this, to the factual ideas of a successful life. With this distinction, the WHO implicitly follows the capability approach developed by Amartya Sen and Marta Nussbaum at the end of the 1980s. Within the framework of this approach, instead of material wealth (e.g. income), benefits (joys, wishes fulfilment) or basic goods, the positive freedoms and abilities of a person to actually be able to lead the ‘life he or she values with good reasons’ (Sen Citation2005: 94) are placed in the centre of attention. Sen understands abilities as ‘modes of functioning’ — more precisely: as the ability of an actor to be able to do the things he/she likes for good reasons and to be the person he/she would like to be (Sen Citation2005: 95). Thus, the focus is not on life support, but on the actual ‘chances of realisation’, which in the eyes of the WHO includes the chance of a health-promoting lifestyle. Within the framework of the capability approach, health thus represents a ‘basic capability’ (Nussbaum Citation1998: 57). This tradition also includes the concept of health as developed by Hurrelmann in the tradition of Antonovsky's (Citation1987) salutogenesis, according to which health is a stage in the balance of risk and protective factors which occurs when a person succeeds in coping with both internal (physical and psychological) and external (social and material) demands. Health is then a state that allows a person to feel and experience well-being and joy in life (Hurrelmann and Richter Citation2013). To put it in a nutshell, health is ‘the ability to adapt and self-manage, in the face of social and emotional challenges’ (Huber et al. Citation2001: 62).

Thus, subjective and objective well-being and subjective health are central indicators for investigating the chances of realisation and life satisfaction and for finding out how well individuals manage to deal with stressors and burdens. In this regard, we understand health as a central indicator for the study of social centrifugal forces. This focus is therefore particularly suitable for empirically investigating the stresses and strains of social distancing and distant socialising.

In the present survey, however, subjective health represents only one – albeit central – starting point for tracing the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, which are manifested in the lack of contact, in the rules of distance, the possible fears of illness and infection, the radical change in everyday life, etc., and for capturing a mood of the situation (for further factors, see Schedule 1). Previous research shows that respondents from the upper educational groups assess their health much more positively than those from the lower educational groups; this educational gradient is even more pronounced among women than among men and the positive assessment of health decreases with increasing age (RKI Citation2009: 51).

4. Methods

In a quantitative-explorative, non-representative online survey based on a convenience sample, 2,009 participants were included in the analysis after data cleansing. Although the sampling strategy does not allow us to provide information on the population, the questionnaire received 2797 hits. The survey covered relevant topics in the research field of subjective health (see ). The questionnaireFootnote2 could be accessed from 14.04.-03.05.2020. The survey took place at a time during the lockdown in Germany.

Table 1. Subjects of the online survey.

The focus was on the participants’ subjective self-assessment before and during the pandemic. The respondents were surveyed at one point in time. The survey was disseminated in local newspapers, homepages, social networks and email distribution lists and it was carried out by the Chair of General Sociology/Microsociology at the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg; support in the methodological implementation was provided by the Chair of Higher Education Research and Professionalisation of Academic Teaching at the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg.

5. Sample

The sample includes 2,009 participants (71% female, 28.1% male and 0.8% diverse). Persons under 30 and 30 to 40 years of age are most frequently represented in the sample, each by about one third. Of those respondents, 23% are 40-55 years old and 15% are over 55 years old.

Almost all respondents (94.5%) were born in Germany. The percentage of births in the new Laender (former GDR) was 54.0% and 40.6% in the old Laender (former West Germany). The survey mainly reached participants with primary residence in Saxony-Anhalt (Federal State, 46.6%). Subsequently, about 10% of the participants stated that they lived in North Rhine-Westphalia, about 10% in Berlin and 7.4% in Lower Saxony. All other federal states are in the low single-digit percentage range.

A large proportion of the participants have the A-Level or University of Applied Sciences entrance qualification (82.4%), 11% have completed vocational training. A total of 6.3% of participants have no or a different qualification or an elementary or lower secondary school leaving certificate.

The majority of respondents are employed (79.2%), whereas 20.8% are not employed. The sample includes 20% students and about 5% each of pensioners and self-employed persons. Around one third of the participants in the study live in a household with children under 18 years of age. About 27.5% of the respondents are affected by at least one chronic disease. Approximately one fifth of the participants belong to the risk group in case of infection with SARS-CoV-2.

The results of the study make it possible to draw a mood picture on selected aspects in connection with the coronavirus pandemic. Potentially stressful situations, such as childcare, home schooling and loneliness or the threat of losing one's job, were surveyed and their effects considered, and the resources for dealing with these demands were questioned. At the same time, the social consequences of the pandemic in terms of social cohesion and the demand for support and solidarity are discussed. The aim is to sketch a first mood picture regarding the connection between health and crisis, knowing that an online survey using convenience samples has clear limitations with regard to the generalisability of the results. More than 65% of the respondents have agreed to a follow-up survey, so that the results of a future second survey can clearly show a process flow. Further qualitative surveys (e.g. interviews) will deepen the descriptive-quantitative data and show whether the coronavirus crisis will be inscribed in the collective memory in Germany.

6. Selected key findings

Starting from the consideration that the coronavirus-induced lockdown and its consequences had an impact on the subjective, psychosocial health of individuals in late modern societies, we will discuss the self-assessment of stress potentials and subjective health of respondents, comparing the descriptive results from before and during the pandemic. In addition, gender and education-specific inequalities show that the crisis has not affected all individuals in the sample equally intensively and that the resource situation also shows structural differences. Questions of social cohesion, trust and solidarity are just as central.

6.1. Subjective health and well-Being

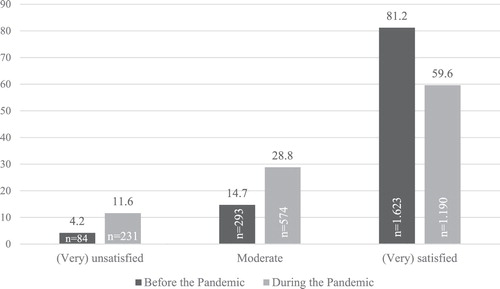

The results show that the assessment of the respondents’ subjective health status has decreased since the coronavirus pandemic. Of those surveyed, 88% stated that they assessed the state of health before the pandemic as good or very good (question wording: How do you rate your health status before the pandemic? Scale: 1) very poor 2) poor 3) moderate 4) good 5) very good 6) no response). During the lockdown, this was the case in only 79% (Question wording: How do you assess your current state of health? Scale: 1) very poor 2) poor 3) moderate 4) good 5) very good 6) no response). Compared to the situation before the pandemic, respondents indicated that symptoms of stress and exhaustion decreased (exhaustion decreases very slightly) while loneliness, anxiety (the feeling of anxiety doubled) and existential worries increased. Feelings of happiness (see Table A1) and satisfaction decreased in the sample during the lockdown (see ).

Figure 1. Life satisfaction of study participants at the time of the lockdown in Germany; Percentage figures. Question: How satisfied were you with your life as a whole before the corona pandemic?; How satisfied are you currently with your life in general? Reply formats: 1) very unsatisfied 2) unsatisfied 3) moderate 4) satisfied 5) very satisfied 6) not specified Categories 1 and 2 as well as 4 and 5 have been merged.

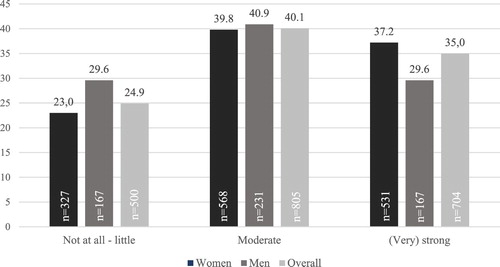

The survey inquired about relevant emotions and their intensity. At the time of the survey, we asked the participants to classify their emotions in relation to the situation during the lockdown and to do so retrospectively for the time before the pandemic. It is noticeable that the feeling of security in particular is decreasing in our sample. According to 72%, they often or very often felt safe from the pandemic. But only 47% have felt safe (often and very often) since the outbreak of the pandemic, and 20% have never or rarely felt safe since the pandemic. (see Table A1 for detailed results, question wording and scales). These factors have a strong influence on psychosocial health and well-being and are reflected in their experience of stress. The participants felt that the general level of strain was high during the lockdown (see ).

Figure 2. Perceptions of stress during the pandemic; Percentage figures. Question: When you look back on the lockdown so far, how much strain did you feel? Reply formats: 1) not at all 2) a little 3) moderate 4) strong 5) very strong. Categories 1 and 2 as well as 4 and 5 have been merged.

For women, the proportion of those suffering from intense to very intense stress is 9% higher than men. The experience of stress corresponds to marital status and is estimated to be higher among respondents with children under 18 than among respondents without children.

6.2. Gender inequality and family life

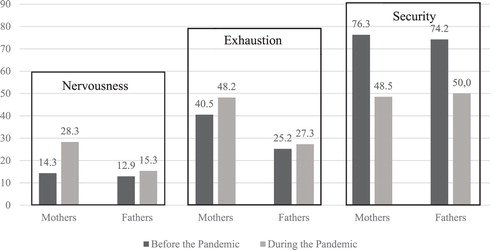

The mothers we surveyed were more likely to provide childcare during the lockdown and were responsible for home schooling. Two-thirds of the parents in the sample had to take over the care of their underage children themselves after day-care centre and school closures. Half of them were working from home offices. The care (73% of the mothers and 51% of the fathers) and schooling (39% of the mothers and 13% of the fathers) of the children was mostly taken over by the mothers (Question wording: To what extent do the following possible situations or life circumstances apply to you in the course of the corona pandemic? a) I am increasingly responsible for the care of underage persons due to the closure of facilities (day care centre, school, etc.). b) I have to provide schooling for my children predominantly on my own. c) I work in a home office. Scale: 1) not applicable at all 2) rather not applicable 3) moderate 4) rather applicable 5) fully applicable 6) not applicable to me). For the respondents who are parents, a decrease in the feeling of stress and exhaustion during coronavirus-related contact restrictions was not observed. Fathers felt more satisfied, more relaxed and more secure than the mothers surveyed (see ).

Figure 3. Comparison of feelings of nervousness, exhaustion and security between fathers and mothers. Questions: How often did you experience the following feelings before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? How often did you experience the following feelings after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? Reply formats: 1) never 2) rarely 3) sometimes 4) often 5) very often Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been merged.

During the pandemic, 72% of respondents who are parents felt restricted in their everyday life. In further detail, they felt restricted in pursuing hobbies (72%), in maintaining social and friendly relationships (92%), in contact with the family (86%) and in voluntary or political activities (52%) but not as much in their professional activities (47%). The gender difference is also evident, as mothers felt more restricted in these aspects than fathers. (To what extent do you feel limited in the following activities due to the contact restrictions imposed by the corona pandemic? Scale: 1) not restricted at all 2) little restricted 3) restricted 4) very restricted 5) no response).

6.3. Differences according to educational attainment

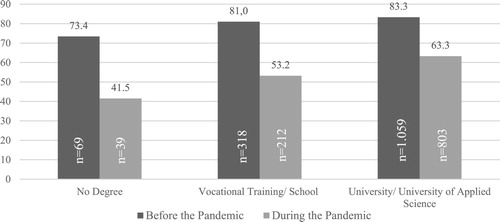

Comparing the time before and during the pandemic, the results show that satisfaction with the work situation has fallen among the respondents. Satisfaction decreases most among those with the lowest level of education (question wording: To what extent do you feel limited in the following activities due to the contact restrictions imposed by the corona pandemic? Scale: 1) not restricted at all 2) little restricted 3) restricted 4) very restricted 5) no response). A similar picture can be seen in the clear decrease of life satisfaction along educational qualifications. In our sample, life satisfaction fell by around 20% among academics, whereas the losses among people without an educational qualification are particularly serious at over 30% (see ).

Figure 4. General subjective life satisfaction before and during the coronavirus pandemic on the basis of educational attainment. Question: How satisfied are you currently with your life in general? Reply formats: 1) very unsatisfied 2) unsatisfied 3) moderate 4) satisfied 5) very satisfied 6) not specified. Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been merged.

Assessments of the psychosocial situation and emotions are important for well-being and mental health. Of those with high educational capital, 7.1% of the respondents felt lonely before the pandemic and 19% during the lockdown. In comparison, 21% of people with low educational capital felt lonely before the pandemic and 32% during the lockdown. The items on fears, happiness, satisfaction, nervousness and sadness show a social gradient, i.e. with decreasing education nervousness, sadness and fears increase and the sense of security and happiness decreases. Interestingly, exhaustion and stress hardly diverge between educational levels, and respondents with lower educational qualifications tend to report less stress and exhaustion since the coronavirus pandemic (question wording and scale as in ).

6.4. Solidarity and trust

In our survey, 29.6% of the respondents assume that German citizens have shown more solidarity with each other during the coronavirus pandemic. Slightly more than half (51%) of the participants only partially agree with an observed increase in solidarity and 19.4% disagree or strongly disagree with an increased solidarity at all. Furthermore, 16.1% of respondents are in favour of isolating the at-risk groups (especially the elderly and people with pre-existing conditions); however, 62.8% disagree or strongly disagree with the isolation of the at-risk groups and only 21.1% say that they partly agree with the statement (question wording: We ask you to assess the following points: a) Since the outbreak of the corona pandemic, people in Germany have shown more solidarity with each other. b) I am in favour of isolating the risk groups (e.g. older people or people with previous illnesses) and allowing the others to move freely again. Scale: 1) do not agree at all 2) rather disagree 3) partly/partly 4) agree 5) agree fully 6) not specified).

When asked about trust in the reporting on the coronavirus pandemic, our survey shows that there is a high level of trust in science in particular: Among the respondents, 34% fully trust science and 44% by an overwhelming majority, the second highest level of trust is in politics with 8% fully and 42% by an overwhelming majority. Social media are the least trusted in terms of reporting (1% trust them fully and 6% trust them overwhelmingly). With the pandemic, interpretative frameworks that view the pandemic as a (mostly global) conspiracy have become louder. For example, 22.1% of respondents believe that the population is being deprived of important information about the coronavirus (question wording: We ask you to assess the following points: a) I think that the population is being deprived of important information about the corona virus. b) I trust in alternative sources of information that report honestly about the virus. Scale: 1) do not agree at all 2) rather disagree 3) partly/partly 4) agree 5) agree fully 6) no response).

6.5. Resources in the crisis

In addition to examining changes in well-being and the experience of stress, our focus was on resilience factors and positive experiences, which were collected via open questions and analysed with the help of a coding system. To this end, three open questions were asked in the survey: ‘What helps you to get through the pandemic period in a healthy and psychologically stable way?’, ‘If you now look back at the time of the lockdown and the coronavirus pandemic so far, what has caused your stress?’ In addition, the 62% of respondents who also had positive experiences during the period of the lockdown gave a brief account of them: ‘Please describe briefly the positive aspects you experienced’.

Respondents cited the change in the use and perception of time as the greatest positive effect of the lockdown. Many respondents experienced the lockdown as a sudden and unexpected gift of time. This was true in both the quantitative and qualitative sense. Time became a resource that was suddenly experienced on a larger scale; it was available and thought about to a greater extent than before the contact restrictions. In the open answers, the participants discussed the opportunity created by the coronavirus to rethink their work-life balance, to question previous work routines and to look for a new balance between work, family and self-care. Typical answers were the desire to ‘reflect on the essentials such as my partner, family and friends’, ‘find peace and quiet and time for oneself’ and to experience a form of ‘deceleration’. In this context, a part of the respondents described that the compatibility of family and work is better achieved by switching to a home office and that the ‘quality time’ is enjoyed with the family. The younger and more educated the participants in the study were, the more often reflections were made regarding the different ways they sought a new relationship between private/family and working time. Topics were mentioned that were experienced more intensively during the lockdown, such as a new experience of nature, a more intensive occupation with their children, and the pursuit of hobbies. These positive experiences during the lockdown period were reported less frequently by respondents with lower education. Both quantitatively and qualitatively, people with high educational capital can benefit more from the time gains and experiences.

When asked what was helpful in coping with the lockdown period, the social environment and, in particular, social support from friends, family and partners were frequently mentioned. However, family and partnership are both a resource and a risk at the same time: on the one hand, the social environment enables social contact and thus a way out of social isolation and, on the other hand, concerns about close relatives and the changed intensity of the relationship with them were frequently expressed as problem contexts. A second central resource area was self-care (including mental strategies of relaxation, self-optimisation and conscious body practices) in order to get through the period of strict lockdown in a healthy and psychologically stable way. This form of self-care applies particularly to women in general (74%), academics (68%) and the younger generation of 17-29 year olds (35%). In comparison, only 25% of men pay attention to self-care.

7. Discussion

The corona pandemic has a strong impact on social life of the people we surveyed. For the sample presented here, it can be shown that the effects of isolation and social distancing lead to an increase in stress and a decrease in life satisfaction comparing to the situation before the pandemic. The corona pandemic has a negative effect on the subjective health of the respondents.

The corona pandemic reproduces and reinforces social and gender inequality in regard to the people we survey. Health is no longer taken for granted by the participants, but experienced as threatened. At the same time, the coronavirus pandemic represents a kind of social laboratory. Central social tension lines along gender-, generation – and education-specific boundaries become clear through the effects of the coronavirus pandemic in our non-representative study. The results of the study can be linked to the state of research on the effects of the pandemic.

We see clear differences between our results and those of SOEP in terms of life satisfaction. In SOEP, life satisfaction has not decreased significantly, satisfaction with the general state of health has increased, and concern for one's own health has decreased. For the participants in our study, we find different results: the participants perceived that life satisfaction has decreased and that subjective health has deteriorated.

We suspect there are several reasons for this: on the one hand, the argument of non-representativeness of course still remains. On the other hand, the data collection on subjective health and life satisfaction in our study was based on a comparison between the time before the pandemic and during the lockdown at a certain point in time. This means that the respondents can immediately assess the time of the lockdown. However, their assessment before the time of the pandemic is only a retrospective view. We have therefore focussed the subjective self-assessment before this comparative horizon more strongly and placed more emphasis on the subjective perception of the participants.

The study has clear limitations, it is a non-representative study, typically used for online surveys, more likely to be used by younger people with higher education. Furthermore, the results must be related to methodological issues in quantitative health research: The Healthy User Bias (see e.g. Shrank et al. Citation2011) assumes that it is primarily healthier people who participate in health or disease surveys and therefore a generalisation of the results to the potentially less healthy population can be problematic.

8. Conclusion

The study revealed that respondents reported a deterioration in their subjective state of health during the survey period. Regarding the sample presented, the general level of strain during the lockdown was considered high and general life satisfaction decreased. For the sample in general, however, stress and exhaustion symptoms decreased in comparison to their subjective assessment of the situation before the pandemic, while loneliness, fear and existential worries increased. In comparison, parents in our sample, especially mothers, reported increased exhaustion and stress. Participants reported that feelings of happiness and satisfaction decreased during the lockdown.

It is not surprising, however, that different social living conditions are also reflected in the management of the coronavirus crisis and have led to states of tension. These different material, cultural and social resources have a decisive influence on how we deal with the crisis.

In addition, the results, in line with other research, show that there are particular burdens on families and especially on mothers, who have had to bear the main load of family care during the lockdown.

As the convenience sample shows a positive selection in the sense of more highly educated, younger people who generally have better (subjective) health, it can be assumed that the trend of deterioration in well-being and health and the increase in burdens reported here is even more widespread in the general population in Germany.

In the context of this study it is remarkable that not only strains but also resources are seen by the participants. The newly gained time for family, hobbies or other activities besides work is seen positively by the respondents. Issues such as self-care and work-life balance also play a major role in the open questions.

Like any disease, the coronavirus pandemic is not only a medical and biological fact but also a collective, social and individual phenomenon (Morris Citation2000; Ohlbrecht Citation2021). Coronavirus is not locally limited and does not only affect a region, a country or a continent but is a global issue. Within a country, coronavirus affects the social milieus in different ways. For the sample surveyed, the results of the online study indicate that low social milieus show greater losses in life satisfaction, are more affected by emotional stress and benefit less from time gains.

It is still too early to answer the question whether a re-traditionalisation of gender relations will take place, or whether resonance experiences (Rosa Citation2016) will be lasting and lead to a readjustment of the balance between work and life. The coronavirus pandemic is not the first global disease to afflict mankind (Herzlich and Pierret Citation1991), but unlike its historical predecessors, it affects late modern societies at a time when disease seemed to have been eradicated, at least in Europe, and health was increasingly considered to be producible and secure. The break with previous routines of everyday life in the wake of the pandemic, e.g. to keep one's distance and refrain from contact, was a massive intervention in the social interaction order of society. This puts people under stress and produces new states of tension in dealing with each other and with themselves. The increase in fears, worries and loneliness recorded in this survey points in this direction.

It was also noticeable that the need to rethink strategies for the good life and to question previous routines was also addressed by the respondents. It remains to be seen to what extent the pandemic will be anchored in collective memory and whether the Covid-19-pandemic will further increase the implied social disruption.

REUS-2020-0155-File008.jpg

Download JPEG Image (720.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 By lockdown, we refer to the intensified measures for infection control by means of social distancing etc., which began in Germany on 22.3.2020 and were loosened again in early May.

2 Access to the questionnaire was provided online via the survey portal of the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg.

References

- Antonovsky, A. (1987) Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Orkan, O., Bollweg, M., Berens, E. et al. (2020) ‘Coronavirus-related health literacy: A cross-sectional study in adults during the COVID-19 infodemic in Germany’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(15): 5503.

- Bertogg, A. and Koos, S. (2020) Lokale Solidarität während der Corona-Krise: Wer gibt und wer erhält informelle Hilfe in Deutschland?, https://kops.uni-konstanz.de/handle/123456789/49942.

- Blom, A., Cornesse, C., Fikel, M. et al. (2020) Die Mannheimer Corona-Studie: Schwerpunktbericht zu Erwerbstätigkeit und Kinderbetreuung, https://www.uni-mannheim.de/gip/corona-studie/.

- Bünning, M., Hipp, L. and Munnes, S. (2020) Erwerbsarbeit in Zeiten von Corona, Berlin: WZB Ergebnisbericht, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K. et al. (2006) ‘Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis', Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(3): 267–275.

- Entringer, T., Kröger, H., Schupp, J. et al. (2020) Psychische Krise durch Covid-19? Sorgen sinken, Einsamkeit steigt, Lebenszufriedenheit bleibt stabil, https://www.diw.de/sixcms/detail.php?id=diw_02.c.298578.de.

- Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (2020) Neue Umfrage. Corona-Krise: 14 Prozent in Kurzarbeit - 40 Prozent können finanziell maximal drei Monate durchhalten-Pandemie vergrößert Ungleichheit, https://www.boeckler.de/de/pressemitteilungen-2675-23098.htm.

- Herzlich, C. and Pierret, J. (1991) Kranke gestern, Kranke heute, München: Beck.

- Hövermann, A. (2020) Soziale Lebenslagen, soziale Ungleichheit und Corona - Auswirkungen für Erwerbstätige. Eine Auswertung der HBS-Erwerbstätigenbefragung im April 2020', Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (ed.), Policy Brief WSI 6/2020.

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L. et al. (2001) ‘how we should define health?', The British Medical Journal 343(7817): 41–63.

- Hurrelmann, K. and Richter, M. (2013) Gesundheits- und Medizinsoziologie, Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

- Idler, E. and Benyamini, Y. (1997) ‘Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies', Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38(1): 21–37.

- Kühne, S., Kroh, M., Liebig, S. et al. (2020) Gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt in Zeiten von Corona: Eine Chance in der Krise?, https://www.diw.de/sixcms/detail.php?id=diw_02.c.298578.de.

- Morris, D. (2000) Krankheit und Kultur, München: Kunstmann.

- Nussbaum, M. (1998) Gerechtigkeit oder Das gute Leben, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Ohlbrecht, H. (2021) ‘Modelle von Gesundheit und Krankheit', in T. Meyer, J. Bengel and M. Antonius (ed.), Lehrbuch der Rehabilitationswissenschaften, Bern: Hogrefe-Verlag.

- Robert-Koch-Institut [RKI] (2009) Subjektive Gesundheit. GEDA 2009, pp. 51–53. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Gesundheitsberichterstattung/Faktenblaetter/GEDA09/geda09_fb_node.html.

- Rosa, H. (2016) Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung, Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Schröder, C. et al. (2020) Erwerbstätige sind vor dem Covid-19-Virus nicht alle gleich, https://www.diw.de/sixcms/detail.php?id=diw_02.c.298578.de.

- Sen, A. (2005) Ökonomie für den Menschen: Wege zu Gerechtigkeit und Solidarität in der Marktwirtschaft, München: dtv-Verlag.

- Shrank, W. H., Patrick, A. R. and Brookhart, M. A. (2011) ‘Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians', Journal of General Internal Medicine 26: 546–50.

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2012) Der Europäische Gesundheitsbericht 2012: Ein Wegweiser zu mehr Wohlbefinden, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/250399/EHR2012-Ger.pdf.

- Wilkinson, R. G. (2001) Kranke Gesellschaften. Soziales Gleichgewicht und Gesundheit, Wiesbaden: Springer.