?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In response to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Union has launched one of the largest assistance packages in EU history, where all 27 EU member states are asked to jointly borrow 500 billion Euros to finance grants to areas hardest hit by the crises. Despite the unprecedented size of this package, we know less about citizens’ support for such a common EU response to the crises. Using unique data from a representative survey in Germany, Italy and Romania, this study shows that while average levels of public support for cross-border financial assistance varies across countries, individual-level determinants are generally unrelated to perceptions of the crises as such. Instead, slow moving factors unrelated to the crises, including general value orientation, cosmopolitanism and trust determine expressions of cross-border social solidarity. We discuss implications for understanding public responses to major crises and long-term support for a common EU response.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has plagued all European nations without exception. The pandemic has caused multiple crises simultaneously, from major health crises to universal shutdowns and economic recessions. Moreover, we witnessed for the first time since the inception of the common market, widespread national border closings and trade restrictions. It is thus not surprising that German Chancellor Angela Merkel has asserted that ‘the European Union is facing its greatest test since its creation’. In the face of this, key leaders in the EU have argued for increased economic solidarity to aid areas of the Union most affected by COVID-19. Indeed, both Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron proposed that all 27 Member States (MS) borrow 500 billion Euros in common, EU public debt to finance grants to areas hardest hit by the crisis (Rueters, May 2020). Despite some opposition from the leaders of the ‘frugal five’ (Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, Sweden and Finland) the largest economic aid package in EU history was agreed upon by the 27 Member States for e750 billion, with e390 billion allocated as grants (New York Times, July 2020). Yet while this top-down approach may be motivated by a will to strengthen the EU, we know little about how EU citizens think about this unprecedented level of economic redistribution across national borders within the EU.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing economic bailouts to affected Eurozone countries, a wave of empirical research has investigated factors that explain patterns of economic solidarity among EU citizens (Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014; Daniele and Geys Citation2015). Building on models of support for EU integration in general (see Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016), most scholars have tested theoretical models that are based on utilitarian factors, such as individual or macro-level economic conditions (Vasilopoulou and Talving Citation2020), identification with Europe (Verhaegen Citation2018; Nicoli et al. Citation2020; Brasili et al. Citation2020; Bauhr and Charron Citation2020b), political ideology (Kleider and Stoeckel Citation2019) or perception of corruption and quality of government (Bauhr and Charron Citation2018; Bauhr and Charron Citation2020a). Building on this recent empirical work, this study investigates the determinants of citizens’ support for EU financial aid directed towards the areas hardest hit by the crisis. Our study suggests that support for such financial assistance is less effected by short term personal economic or health concerns and more predicted by longer standing ‘soft’ factors, such as socio-cultural attitudes, perceptions of corruption and trust.

We employ newly collected survey data that includes a host of questions on perceptions of political institutions, trust, partisan and ideological preferences along with a battery of questions on citizens’ attitudes concerning the Covid-19 virus and one’s home country’s response to the crisis. The survey was administered in May and June of 2020, and thus provides a highly relevant and contemporary insight into citizens’ attitudes towards multilevel economic governance during the crisis while the political debate for closer European integration is ongoing. The sample consists of a survey of three EU member states, Germany, Italy and Romania, from a pilot survey from the European Quality of Government Index survey (Charron et al. Citation2014). Our findings show that citizens who feel personally concerned about the effects of the crises, in terms of health or economic risks for themselves or their families are not more likely to support EU aid than others. Instead, we find that ideological indicators on the socio-cultural ‘gal-tan’ dimensionFootnote1 (Hooghe et al. Citation2002) are associated with support for EU. Much in line with studies on the importance of cosmoplitan values, we fiind that higher ‘gal' values are associated with significantly more support for EU aid packages. Furthermore, we find that perceptions of how well or badly domestic governments handled this specific crises show no association to support for EU aid, while more slow moving factors such as general perceptions of corruption and lack of institutional trust is associated with weaker support for EU aid.

This study thereby adds to the growing literature on the determinants of public support for EU aid in times of crises. This is one of the first studies that empirically investigates public support for EU aid in response to the Covid-19 pandemic (with some exceptions, see for example, Bobzien and Kalleitner Citation2021; Cicchi et al. Citation2020; Beetsma et al. Citation2020). It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in the midst of the pandemic, and it, therefore, provides knowledge on the more short-term effects of the pandemic on support for EU aid. However, given that aid packages are motivated to alleviate health and economic concerns among European citizens, the fact that perceptions of such personal concerns are unrelated to support for EU aid in the contexts we study is interesting. This indicates a potential disconnect between the stated intention and perceptions of benefits it brings to people most concerned about the effects of the crises. Similar findings have been shown regarding support for foreign aid during Covid-19 in the United States (Kobayashi et al. Citation2020). While investigating why this is so is beyond the scope of this study our theorized mechanisms include that citizens who feel affected by the crises may not expect to personally benefit from the funds, at least not in the short-term, and that the direct benefits of financial transfers may therefore be perceived as rather opaque to most citizens. Instead, concern, anxiety and perceived threat may result in personal preventive behavior over which citizens may feel they exercise more control. This is also in line with previous research finding that suggests that public support for EU aid is based less on material concerns or utilitarian factors and more on ideological and value orientation (i.e. Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Daniele and Geys Citation2015).

Furthermore, apart from its political relevance, our study constitutes an excellent test case for some of the theories developed to explain support for EU solidarity more broadly. Our study shows that several factors identified in previous studies as being important to explain public support for within EU fiscal redistribution can also explain support for financial assistance in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. If the concrete and heightened risks associated with the Covid-19 pandemic does not shift the importance of the GAL-TAN dimension, this strengthens previous findings on the importance of the socio-cultural dimension in explaining public support for within EU fiscal redistribution, not the least since our study also controls for factors such as the left-right ideological dimension, traditionally seen to structure redistributive preferences. Our study also brings new evidence on the intricate link between perceptions of corruption, institutional trust and public support for cross-border redistribution (Bauhr and Charron Citation2018). A growing body of work suggests that perceptions of government performance (including perceptions of corruption and institutional trust) will have implications for public support for EU aid, either increasing it (if the EU is seen to compensate for deficient institutions) or by decreasing it (if levels of trust and distrust simply travels across the multilevel governance system). While we find support here for the idea that perceptions of corruption and distrust travels across the multilevel governance system, effects are driven by general perceptions of corruption and institutional trust, rather than perceptions of how governments handled the crises as such, at least in the short term.

Explaining citizens’ support for EU aid

In a speech to the European parliament on March 26 2020, Ursula van der Leyen, president of the European Commission encouraged Europe to ‘do the right thing together with one big heart, not 27 small ones’.Footnote2 While the focus of the work has arguably been on facilitating elite level agreement on a common response to the Covid-19 pandemic, we know little about to what extent citizens support such large-scale transfers between countries. While the literature explaining public preferences for EU integration is ever growing (for a review see i.e Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016), studies increasingly point to the multidimensionality of public support for the EU. For example, (Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011) argue that a single latent idea of EU support or skepticism is too broad, and they find that there are several different dimensions of EU support. One such distinct dimension is support for within EU economic redistribution.

In recent years, studies have begun to focus their attention more directly on if citizens broadly support fiscal redistribution within the EU, and if so, what determines such support. Thus, while the vast majority of studies that investigate public support for the EU do not investigate support for fiscal redistribution, there is a growing literature that seeks to explain public support for within EU fiscal redistribution, including intra EU financial assistance, bailouts or cohesion policy (see i.e. Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Bauhr and Charron Citation2018; Bauhr and Charron Citation2020a; Charron and Bauhr Citation2020; Daniele and Geys Citation2015; Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014; Kleider and Stoeckel Citation2019; Stoeckel and Kuhn Citation2018). Studies note that the determinants of fiscal redistribution may be different from the determinants of general support for the EU both since the costs of these reforms are more concrete (i.e. can more easily be expressed in euros or dollars) and general EU support may be more related to support for a common market than financial solidarity and preferences for redistribution (Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014). Aid in response to a particular crises, with a concrete price tag, such as in the case of the Covid-19 response may, in turn, also be more concrete than asking about support for fiscal redistribution through citizens support for cohesion or regional policies, since this is a policy that many Europeans may not even have heard of before.Footnote3 Understanding what factors determine public support for massive cross-border transfers is important for anyone interested in the future of common European responses, not least in times of crises, as public opinion can have a constraining effect on policy-makers (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009).

Studies that investigate the territorial reach of solidarity, show that citizens oftentimes express stronger solidarity within the boundaries of the nation state. This is perhaps not surprising, given that welfare state redistribution has in many European contexts been organized around the boundaries of the nation state. Studies have therefore directed attention to if and when citizen express social solidarity beyond national borders in the form of foreign aid (Fenger and Paridon Citation2012; Heinrich et al. Citation2016; Paxton and Knack Citation2012). A common crises such as the Covid-19 crises can have divergent implications for the level of cross-border solidarity. A perceived crises or threat could on the one hand make citizens turn to national authorities to alleviate concerns and uncertainty. However, perceptions of common threats, shared across diverse countries, may also illicit a sense of shared responsibility and commonality that may lead to greater cross-border solidarity. The extent to which citizens turn to national or supranational institutions in times of crises is likely to vary across segments of the population.

Important insights into the determinants of preferences for national vs international responses on support for cross-border financial redistribution can be found in the emerging literature on public support for within EU financial redistribution. The literature seeking to explain public support for fiscal redistribution and social solidarity within the EU focus on three broad types of determinants: values and identity, utilitarian factors and ‘cue’-taking’ – including from political and media elites or perceptions of institutional performance and trust (Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). The broader literature on both domestic and international redistribution point to the importance of utilitarian factors, i.e. that support for redistribution should be stronger among citizens and countries that benefit from it the most (i.e Alesina and La Ferrara Citation2005; Beramendi and Anderson Citation2008). Yet, the literature on European economic integration also point to the importance of more ideational factors including values, institutional trust, identity and cosmopolitanism (Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014 Daniele and Geys Citation2015; Baute et al. Citation2019; Kleider and Stoeckel Citation2019; Kuhn et al. Citation2018), and that such factors can be more important to explain public support for financial redistribution. This means that the determinants of support for fiscal redistribution can be different from other dimensions of support for the EU. For instance, Hobolt and Wratil (Citation2015) find that citizen’s support for the euro were driven more by utilitarian as opposed to identity concerns among citizens in euro countries during the financial crises.

Building on these findings, we suggest that the socio-cultural dimension of ideology or the ‘GALTAN’ dimension will have important implications for public support for EU aid in response to the Covid 19 pandemic. Traditionally, the ideological left-right dimension has been seen to structure redistributive preferences, where the economic left is more pro redistribution than the economic right (Feldman and Zaller Citation1992). However, the economic left-right dimension may be less important for determining preferences for cross-border redistribution. Building on recent studies on important ideological and value dimensions that structure national vs international re-distributive preferences we suggest that the most important value and ideological cleavage determining levels of cross-border solidarity can be found in what is sometimes referred to as the socio-cultural dimension of ideology, or the GAL –TAN dimension (Hooghe et al. Citation2002). A person on the green-alternative and libertarian end of this scale will hold values that are more cosmopolitan and may therefore be more likely to the see the benefits of common international responses to crises such as the Covid-19 crises (Kuhn et al. Citation2018). On the other hand, those adhering to a more traditional, authoritarian and nationalist ideological stance will prefer national level responses and be skeptical towards any common European response and not least massive fiscal transfers. Several studies show that the GAL TAN division structures party competition, and public support for parties may provide cues for citizens to either support or oppose EU integration (see i.e Brigevich Citation2018; Van der Brug and Van Spanje Citation2009). It is also possible that ideological, trust based and more utilitarian explanatory factors are somewhat interrelated in the sense that those that place themselves on the GAL end of the GAL-TAN scale may also be more likely to trust international institutions and perceive that their country would benefit, at least in the long run, from more fiscal redistribution, solidarity and economic development throughout the EU. This leads us to our first expectation:

H1. (ideological values) Citizens’ who hold greater degrees of GAL (TAN) ideology will hold a stronger (weaker) support for a common EU response to the Covid-19 crisis

Furthermore, several studies suggest that citizens use cues about the performance of their own domestic institutions to determine their support for EU integration (De Vries Citation2018). This ‘benchmarking’ idea can be traced back to Hoffmann (Citation1966) that argued that perceptions of national legitimacy could be an obstacle to future EU integration. Studies disagree, however, about whether citizens actually compare levels of performance across institutional levels or if they, instead, simply base their assessment of the trustworthiness of supranational institutions on cues about the performance of domestic institutions. An active comparison across institutional levels would require a high level of political sophistication and citizens may not have sufficient knowledge about the performance of EU institutions (see i.e. Anderson Citation1998). If citizens use their own domestic institutions as cues to assess the performance of supranational level institutions, trust (and distrust) are reproduce across governance levels, what has sometimes been called the ‘equal assessment’ hypotheses (Kritzinger Citation2003, see also Muñoz et al. Citation2011). Several recent studies suggest that individuals that trust national level institutions also tend to trust the EU (Armingeon and Ceka Citation2014), including the EU Parliament (Muñoz et al. Citation2011) and EU democracy (Rohrschneider Citation2002), although some studies suggest that patterns are not necessarily consistent before and after the financial crises (Serricchio et al. Citation2013; Arpino and Obydenkova Citation2020). Conversely, citizens may also potentially compare the relative performance of institutions across levels in a multilevel governance structure, which leads to very different expectations of the effect of dissatisfaction with domestic institutions. If citizens more or less actively compare the performance of national vs supranational institutions, dissatisfaction with domestic institutions could make citizens place their hopes in EU institutions and increase their support for EU integration (Kritzinger Citation2003; Sánchez-Cuenca Citation2000). This means that citizens are able to evaluate national and supranational institutions independently from, and in comparison with, each other, what has been termed the ‘different assessment’ hypothesis (Kritzinger Citation2003), or the ‘compensation’ hypothesis (Muñoz et al. Citation2011). While both perspectives are plausible, recent studies have shown empirical support for the equal assessment idea – that due to the complex nature of European economic integration, citizens rely on perceptions of domestic institutions and corruption as heuristics in assessing such policies (Bauhr and Charron Citation2020a; De Vries Citation2018). From this literature, we derive the following:

H2.(institutional cues) Citizens’ who hold more positive assessments of national political institutions, such as higher trust in government and lower perceptions of corruption, will show greater support for a common EU response to the Covid-19 crisis

Earlier studies on public support for EU integration found robust support for utilitarian factors, such as occupation, education or income – with higher skilled, more educated workers that benefited most from the common market being more supportive overall (Gabel Citation1998). In subsequent years, utilitarian factors were often out-weighted by other factors, such as identity, or political/institutional cues when investigating overall support for EU integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2005; Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). However, the determinants of support for large amounts of inter-EU fiscal transfers may differ from factors that explain overall support for EU integration, including the common market and trade liberalization (Kuhn and Stoeckel Citation2014; Kanthak and Spies Citation2018). While previous studies investigating public support for within EU fiscal redistribution often find limited support for the importance of utilitarian factors, investigating this in the context of the pandemic is important since threats to occupation and income may become more acute and visible to many citizens and they may also be more frequently reminded about the threat that the pandemic poses to national level economic performance. Thus, while studies on support for within EU fiscal redistribution suggest that utilitarian factors such as occupation and income are of limited importance, it is quite possible that the importance of these determinants may shift during an acute pandemic. In particular, occupational and economic security may make citizens more likely to perceive that it is a viable option to share resources with distant others. To the degree that utilitarian factors play a role at the individual level, we anticipate the following:

H3. (utilitarian factors) Citizens with higher socio-economic status will show greater support for a common EU response to the Covid-19 crisis

While the theoretical expectations outlined in H1–H3 build on slow moving factors, such as ideology, institutional trust and utilitarian factors, public support for rescue packages and responses to a common economic crisis could be expected to at least partly be influenced by citizens’ perceptions of the severity of the crises, in terms of i.e. health and economic risks. In addition, a crisis most definitely puts domestic institutions to test and the perceived performance and effectiveness of these institutions in responding to the crises could potentially be expected to influence support for common responses and fiscal rescue packages. While a number of studies investigate other forms of crises, such as the 2008 financial crises, we know less about how pandemics affect such expressions of EU solidarity. However, studies across a range of crises, including the Ebola outbreak (Yang and Chu Citation2018), the SARS and Avian influenza epidemics (Leppin and Aro Citation2009), the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 2009 (Prati et al. Citation2011) and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic (Dryhurst et al. Citation2020; Van Bavel et al. Citation2020), point to the importance of understanding risk perceptions (see also Slovic Citation2010). Perceptions of risks and threat has been found to be an important determinants of protective behavior in different settings, including such things as physical distancing, hand washing and wearing face masks (Dryhurst et al. Citation2020), much in line with protection-motivation theory (see i.e. Rogers Citation1975). However, being motivated to participate in health protective behavior is very different from supporting international redistribution or expressing solidarity across borders. Research suggests that citizens’ support for i.e. collective institutions such as the welfare state is partly motivated by perceptions of risks, such as the risk of being unemployed or becoming ill, yet such support can potentially be seen more as a form of insurance against future risks, and not necessarily risks that affect you here and now. Possibly, those that do not feel immediately threatened by the pandemic would be more likely to think in terms of more long-term solutions to the problem, whether through investing in domestic welfare states or supporting international cooperation and financial transfers from international organizations such as the EU.

A crisis may also have implications for how citizens evaluate the performance of domestic institutions. It is yet unclear to what extent, or when, citizens ‘update’ their preferences for EU integration due to short-term events. Some research suggests that citizens are guided much more by their deep rooted values and trust rather than recent experiences and perceptions of current policies when expressing support for the EU (Harteveld et al. Citation2013). Yet others show that as contemporary material economic conditions change, so does public opinion on the EU on whole (Foster and Frieden Citation2017). For example, in the aftermath of the 2009 financial crisis in Iceland, politicians and citizens became rapidly more pro-EU integration, and the country followed with immediate closer integration with the EU (Thorhallsson and Rebhan Citation2011). Others suggest that the financial crises lead to a decline in trust in both national and international institutions (Armingeon and Ceka Citation2014). Specifically, in regard to how Covid-19 affects European preferences of EU fiscal governance, Beetsma et al. (Citation2020) find that Dutch citizens’ support for EU economic integration does not change when comparing samples before and after Covid-19, although some stipulations (such as more spending on health care) are larger drivers of support post-pandemic. Moreover, Bobzien and Kalleitner (Citation2021) show that sociotropic economic concerns reduced support among Austrians for EU Covid-19 aid. However, since this pandemic has created a level of crisis many Europeans have never experienced, we do not have much a precedent on which to base whether or not contemporary attitudes towards Covid-19, such as perceptions of how one’s authorities have handled the virus, or the degree of personal or economic worry citizens perceive for themselves or their immediate family, will affect support for a common EU economic aid package.

H4. More positive perceptions of experiences of the Covid-19 crises and its management is associated with support for a common European financial response to the crisis

Sample, data and design

Our survey data comes from a recently collected pilot survey within the European Quality of Government Index project (Charron et al. Citation2014; Charron et al. Citation2019), where respondents are asked a battery of questions about the quality, impartiality and degree of corruption (perceived and experienced) with their public services, inter alia. Three countries – Germany, Italy and Romania – are included as they represent three different geographic areas of the EU (West, South and former-East respectively), as well as having significant variation in experience with the Covid-19 crisis.Footnote4 The sample from each country is roughly 1000, with a total of 3035 respondents in the pooled dataset. The survey employs a mixed method of administration to best reach out to all demographics and to thus maximize representativeness. 50% of our respondents are randomly selected via telephone interview randomly-dialed, computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI), and the other 50% are taken via online interviews via a quota method based on gender, age and education categories, which were taken a priori from Eurostat.

Due to the unique circumstances of the Covid-19 crisis, an additional set of questions was added to gauge citizen attitudes and opinions regarding the crisis. Prior to the launch of the survey, the proposal on inter-EU grants was put forth by leaders of key EU Member States, and thus a question on this particular issue was included.

The outcome variable of interest seeks to capture citizens’ EU-level solidarity in the face of the current crisis, and the degree to which people are willing to have their country (and thus their taxes) contribute to a pan-EU response to Covid-19 for the most afflicted areas. Rather than simply asking one’s support for an overall EU response (which might simply induce a high degree of acquiescence bias, see for example Bradburn Citation1983), we present a non-technical trade-off between an EU-wide response versus a national one; whereby we present a scenario closely tied to a current debate that imposes a choice of one’s preference within a multi-level governance framework. Note that we do not go into details about the parameters of the aid package, nor do we inquire about which body (EU Commission, member states, etc) will oversee the aid package. Our main concern is to avoid overly technical language and to simply measure the degree of economic solidarity within Europe, vis-a-vis an exclusively national response. The use of the horizontal rating scale is employed here to reduce acquiescence bias (De Vaus Citation2013). The question posed to respondents is the following:

In response to the COVID 19/corona pandemic, people have different opinions on how to deal with the crises. On 1–7 scale, with ‘1’ being in full agreement with the 1st statement and ‘7’ in full agreement with the 2nd statement, where do you place yourself on this issue?

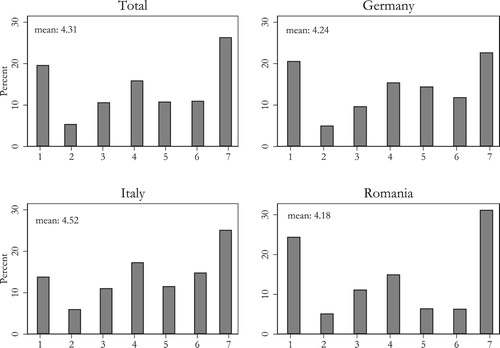

We reverse the scale so that higher values indicate more EU-wide economic solidarity. shows the distribution of the pooled responses (’total’) and for each country. Overall, we find that the respondents are generally supportive of the EU financial aid – the mean is 4.31.Footnote5 Yet there is considerable variation throughout the sample, over 35% leaned toward a national response (e.g. lower than ‘4’), and nearly 20% responded ‘7’ (reversed to ‘1’), indicating a strong preference for each EU Member to handle their own response to the crisis independently. We also observe that Italians are generally most supportive, while Germans and Romanians somewhat less so. Romanians also tend to be more polarized at the extreme ends of the distribution compared with the other two countries.

Figure 1. Citizen preferences for EU versus national response to corona crisis.

Note: Total number of observations = 3035, unweighted. The scale is reversed from original question, with ‘1’ preferring national only to ‘7’ preferring EU aid.

To explain this variation we test several potential theoretical models with the variables available to us from the survey. As per the findings of several recent studies on the effects of ideological and partisan divides in explaining support for EU economic integration (Bechtel et al. Citation2014; Van Elsas and Van Der Brug Citation2015; Stoeckel and Kuhn Citation2018), we proxy one’s ideological views on several dimensions in two ways. First, we take a measure of preferences for domestic redistribution as a proxy for left-right placement. On the socio-cultural dimension (GAL-TAN), we build on the work of the Chapel Hill expert survey data on political parties (Bakker et al. Citation2020) and include support for gay marriage (Gay and lesbians should be allowed to marry legally) the importance of Christianity in one’s society (Christianity is an essential part of (COUNTRY’s) national identity) and preferences for more traditional’ societal values (We would be better off in (COUNTRY) if we went back to protecting our traditional values). We construct a ‘gal-tan’ index using these three items.Footnote6 Second, as respondents were asked about which party they would support if the election were held today, we then take this preference and match it with the latest round of the Chapel Hill expert survey data (Bakker et al. Citation2020); coding the left-right and gal-tan dimensions of each respondent based on their party choice. This variable serves as a possible proxy for ideological preferences as well as ‘cue taking’ from political elites (Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). Greater degrees of ‘left’ and ‘gal’ may be associated with greater support for pooled, EU-aid to struggling member states. As the party data leaves us with fewer observations due to the fact that roughly 20% of the respondents not expressing support for any party, we report the proxies of ideological values from the survey and use the party proxies in robustness checks.

To test H2, we rely on survey questions about political trust in national and local institutions, as well as generalized trust in others, since trust in institutions is often an important determinant of EU support (Muñoz et al. Citation2011). To proxy for perceptions of domestic corruption, we take a survey question on the degree to which respondents believe others must use bribery to obtain public services. For the utilitarian hypothesis (H3), the survey provides us with several proxies, including occupation, education, income and one’s satisfaction with the national economy on whole, the latter of which serves as a proxy for socio-tropic perceptions (Gabel and Palmer Citation1995). While we do not have a sufficient number of countries to do empirical tests with country- level GDP or unemployment variables, there are of course economic distinctions between the three, and thus Germany is used as a proxy for higher economic development compared with Italy and particularly, Romania, thus we anticipate German supporters will be least supportive on whole of a common EU aid package.

To test whether short-term attitudes of the crisis itself affect support for an EU aid package (H4), we include three specific variables that capture citizen attitudes to the crisis. The first is a measure of satisfaction with one’s local authority’s handling of the Corona virus. The second and third are the degree of personal health and economic worry that a respondent perceives for him/herself and his/her family.

Finally, we include age, gender, type of interview administration (online or CATI) and country fixed effects. Unfortunately, we do not have a proxy for ‘exclusive national identity’, which is often a powerful explanatory variable in EU support models (Hooghe and Marks Citation2005). An alternative is the party choice and the degree of Euroskepticism vis-a-vis pro-Europeanness from the Chapel Hill data. We envision respondents who support more Euroskeptic parties to be a suitable proxy for national identity. We employ this as a control variable in several models. In terms of comparing the magnitude of effects of the variables, several of the non-binary survey questions are on different scales. We, therefore, standardize (z-score) all such variables to make the magnitude of the effects more comparable. A further description and summary statistics of all variables as well as question formulation are provided in appendix 1.

Our estimation strategy is straight-forward. Our dependent variable is on a seven point scale (reversed so that higher values equal more EU solidarity), our main estimates rely on standard ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation.

(1)

(1)

Where an individuali in countryj expresses support for EU-wide aid (Support) or not as a function of our k number of main explanatory variables, γ, such as corruption perceptions, ideology, party cues, geographical identity/trust and utilitarian factors. θ represents the effect of the battery of k number of individual level demographic controls and control variable attitudes on Corona virus (Z). As individuals and municipalities are also nested in three Member State countries (MSp), which differ in terms of support for a common EU economic response and the relevant theoretical explanatory factors, we include country dummy variables as fixed effects to account for this unexplained variance. is our error term. All models include survey post-stratification weights to provide more representative estimates.

Empirical results

We begin with a step-wise approach shown in , beginning with a baseline model of only control variables, and then proceeding to test each of the hypotheses separately with the control variables. Model 6 combines them into a final model. Model 1 elucidates the effects of the control variables. We observe that neither age nor gender play a significant role in explaining support for an EU response vis-a-vis a national one. Yet support is greater among higher educated respondents, as well as Italian respondents (compared with German ones), both findings are in line with expectations from previous research.

Table 1. Test of support for EU economic Covid-19 cooperation.

Model 2 explores the effects of the respondents’ attitudes on gal-tan and left-right political dimensions. While these variables also work in opposite directions (more ‘tan’ equates with a stronger preferences for national response, while more ‘right’ equates with stronger EU response), the left–right variable is statistically indistinguishable from ‘0’. The gal-tan variable however has a sizable effect on the outcome variable, with a one-standard deviation increase leading to a roughly 0.4 decrease, and a total effects change resulting in a nearly two-thirds standard deviation decrease in support for an EU-wide response. Thus, as anticipated from previous works where the two dimensions have been compared directly, we find that the socio-cultural dimension of political values trumps the economic dimension (Hooghe et al. Citation2002; Bechtel et al. Citation2014).

Model 3 tests H2, and investigates how one’s level of trust in institutions, social trust and perceptions of corruption is associated with support for an EU common response, since such institutional cues could drive support for EU economic integration. Here, we find that all trust variables are statistically distinguishable from ‘0’, with social trust and national political trust being positively associated with greater support for European cooperation, while local trust and perceptions of corruption, holding all factors constant, are associated with preferences for a more national-level response. In this case, we might be able to infer that differences in trust for the two levels of governance (national and regional) provide us insights into a respondent’s geographic identity, which work in conflicting ways in terms of support for European economic cooperation. The negative association between higher levels of regional trust and support for a common EU response, is consistent with previous evidence that suggest that greater regional identity equates with lower support for EU integration (Brigevich Citation2018). We also find that higher social and political trust corresponds with higher levels of support for EU economic integration, which is also consistent with several previous studies (Bauhr and Charron Citation2018; Kanthak and Spies Citation2018).

Model 4 test the proxies for utilitarian-type arguments at the micro level – such as occupation, income, or perceptions of one’s national economic performance – and if these explain support for EU economic cooperation. In none of these cases do we find that higher socio-economic status, type of occupation or even one’s own perceptions of the national economy affect one’s stance on an EU versus national response to the crisis.Footnote7 Moreover, we observe that even education drops from significance when accounting for H1, H2 or H3. On the other hand, there is some macro-level evidence for a utilitarian case in that Germans on whole (which are and will be net contributors) are the least supportive, while Italians in particular (who are expected to be the greatest net beneficiary) exhibit the highest levels of support for an EU-level response.

In model 5, we test whether the short-term attitudes regarding Covid-19 affect one’s position on an EU-wide economic response. Surprisingly, there is no relationship between how respondents perceive the performance of their authorities in handling the crisis and their preference for more EU governance. However, this could perhaps partly be explained by the fact that this type of economic integration is specific to this pandemic in particular, and based on need, thus less likely to serve as a ‘lifebuoy’ (Harteveld et al. Citation2013) for all citizens in EU countries that have relatively poorer performing institutions. Nor do we find that one’s own personal worry about the health of themselves and their family affect our outcome significantly. We do however see some evidence that personal concern about one’s own economic situation drives down support for an EU aid package compared with a national response. However, in model 6, where the full model is estimated, this effect drops from significance. This lack of significance of personal worry is in line with other recent research on support for foreign aid in the US (Kobayashi et al. Citation2020). In this final model, we observe that the other effects on models 2–4 are largely robust. In terms of the magnitude of effects, the final model also shows that the gal-tan scale has the greatest impact on one’s preferred response-EU or national to the economic crisis caused by the Covid-19,Footnote8 yet that the effect is statistically indistinguishable from trust in national political institutions (p = 0.77). In addition, we also find significant and mainly robust country-level effects. German respondents are consistently the least supportive on an EU aid package and lean towards a more national response on average, while Italians and Romanians express considerably more support.

As regards the control variables on whole, several findings are noteworthy. One, age and education tend to be positive predictors of greater support for and EU-wide response, yet are only statistically significant in some models, while a respondent’s sex and whether they were an online or CATI respondent are negligible factors. In terms of country level effects, several models (2, 3 and 6) show evidence that Romanians and Italians on whole are consistently more supportive than Germans. Model 6 demonstrates that when individual-level effects are controlled for, Romania is significantly higher than Italy in supporting EU aid (p = 0.01). That the country-level effects vary across models is indicative of the fact that gal-tan, levels of trust and perceptions of corruption vary significantly across countries.

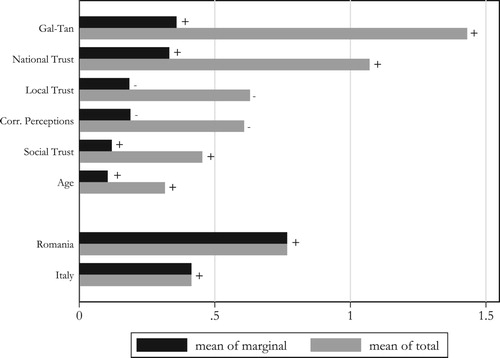

provides a summary of all significant predictors and the magnitude of their relative effects in terms of a standard deviation (black) and total change (grey), with positive (+) and negative (−) effects indicated. As noted, the effects with the greatest magnitude are the socio-cultural, ‘gal-tan’ dimension, followed by trust in political institutions and perceptions of corruption. While the total effects of gal-tan and national trust are quite sizable (roughly 0.66 and 0.5 standard deviations of the dependent variable respectively), the average marginal effects of the significant predictors are more modest; ranging from 0.05 standard deviation change in support for EU aid (age) to 0.16 (gal-tan).Footnote9

Figure 2. Summary of significant predictors.

Note: Results from full model 6, weighted. Black bars represent the expected change in the dependent variable from a one standard deviation increase of the variable shown, while the grey bars show the total effects. +/− represent the sign of the effect. Effects of Romania and Italy are in relation to Germany.

Robustness Checks

In appendix section 2, we provide several checks of robustness of the results presented in . First, we re-run the full model one country at a time. Overall, the direction of the effects are largely consistent with the pooled model, yet some effects fall below significance levels in certain countries, which could reflect contextual heterogeneity of effects, or simply lower statistical power due to fewer observations per model. The findings here demonstrate that the effect of the gal-tan scale is robust across all three countries, with varying magnitude. We also see that national political trust is significant in Germany and Italy, and in the expected direction in Romania (p=0.19). Social trust is also positively associated to support for an common EU response across all three countries, yet just under significance in Germany. The effect of corruption perception are clearly most salient in Italy, while the negative effects of local trust are most pronounced in Romania. We also observe some counter-acting gender effects – while females in Italy are less supportive of a common EU response, females are more supportive than males in Romania. In addition, while the left-right is negligible in both Germany and Romania, it is a salient explanatory factor in Italy. Despite some country deviations, the main message of the pooled analysis remains, however, in that long-standing values and attitudes are the primary explanatory factors rather than utilitarian or short-term concerns regarding the pandemic.

Second, we re-run the test of H1 using party support as a proxy for ideological position. For this, we code each country’s party according to the Chapel Hill expert survey data along the gal-tan and left-right dimensions. Similarly to our survey questions which proxy for these dimensions, we find that the party-level data produce very similar results – respondents who support more ‘tan’ leaning’ parties show lower support on average for an EU aid package, while the left-right dimension at the party level is negligible. Third, without a clear indicator of exclusive national identity’, we re-run the models with a party-level proxy for this. Again, we employ the Chapel Hill data and code each party along the ‘European Integration’ dimension, with the idea that respondents who support parties who favor less integration most likely overlap to a significant degree with having an exclusively national identity. We find that this variable is significant in several models in the expected direction, yet does not alter our main findings.

Discussion

This study offers an early investigation of the determinants of public support for a common EU fiscal response in times of crises. Using the case of the Covid-19 pandemic the paper suggests that public support for fiscal redistribution in times of crisis is less guided by public perceptions and perceived threats related to the crises as such, including satisfaction or dissatisfaction with domestic institutional responses to the cries, but rather more longstanding, ‘sticky’ values, ideological orientations and trust. Using a unique and to the best of our knowledge one of the first cross-country comparative dataset asking about citizens preferences for an EU vs national response to the Covid-19 pandemic, we find support for these propositions. We show that citizens that score high on the GAL end of the GAL-TAN dimension and citizens that express a high level of trust in national level domestic institutions support a common EU fiscal response to the crises, while those holding more nationalist values are likely to oppose all such efforts. We also find that higher levels of social trust and lower perceptions of corruption are associated with greater support for an EU response versus a national one to the pandemic. Thus we find support for H1 and H2. Regarding H3, we do not find any evidence that utilitarian factors explain variation in our outcome variable, thus citizens do not appear to be responding to cost–benefit calculations based on income, occupation or perceptions of the national economy. However, there are clear national level effects that could represent utilitarian-type logic in that citizens from the wealthiest, net-contributing country, Germany are the least supportive of an EU aid response and are most likely to prefer a national response. This implies that possible utilitarian motivations are more likely to be sociotropic rather than based on concerns about individual level well being. However, more countries would be needed to check whether this is a systematic trend, or an idiosyncratic finding germane to these three countries in particular. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, perceptions of the crises as such, as captured by perceived economic and health threats as well as perceptions of domestic handling of the crises does not determine support for a common EU response. Thus we do not find support for H4.

Understanding the determinants of public support for the largest financial package in EU history is important in its own right. In light of the large literature on support for the EU in general, the literature on the determinants of support for EU financial assistance is rather limited in scope. In light of massive cross-border transfer, through EU cohesion policy, bailouts and assistance packages launched in response to economic and most recently health crises warrants a closer attention to citizens support for cross-border transfers.

However, there are several caveats that should be highlighted in this research. First, our data is cross-sectional and observational, thus we caution readers to draw causal inferences from our findings. Second, the timing of our study could affect the results. As the survey was launched in the summer, many opposition actors might not have had sufficient time to craft a narrative against the aid package, and thus there could be lower overall public support in the later months of 2020 when national debates had better developed. Third, with only three member states in our sample, one should be cautious in generalizing our findings to the EU public on whole. Forth, while our dependent variable has several strengths, there are of course trade-offs with our approach. One, the variable might be capturing multiple dimensions of solidarity; where we offer a trade-off between both EU vs national solidarity, there is also a possible trade-off between solidarity and non-solidarity. However, we assume that the percentage of people who would prefer their government to not distribute resources to some degree (e.g. non solidarity) in response to this particular crisis would be a small minority, and most likely affect our findings minimally. Two, it should be clear that when discussing solidarity, broadly speaking, in this case, we imply sociotropic solidarity, and not that of individuals (poorer, those who become personally affected by Covid-19, etc.). As the EU does not target aid to individuals (e.g. the poor, the elderly, etc.) but instead to regions or countries, this is an inherent feature of any EU redistributive or aid package. Third, the general framing of the question could be influenced by elite cues, which we do not measure directly.

Nevertheless, this study makes several important contributions towards increasing our understanding of the determinants of public support for cross-border financial assistance in times of crises. First, it shows that the ideological dimension that most strongly predict support or opposition is the GAL–TAN dimension (Hooghe et al. Citation2002; Kuhn et al. Citation2018). While the left-right ideological dimension is oftentimes characterized as structuring preferences on the economic re-distributive dimension, where left-wing supporters are more likely to support government lead redistribution and reductions in economic inequality, this ideological dimension is less relevant to explain support for international redistribution. Here, values such as cosmopolitanism and internationalism vs nationalism cut across the left–right divide and is much more important to explain support for within EU redistribution. Thus, studies that emphasize the effects of the left-right dimension on attitudes towards EU integration could yield misleading inferences without controlling for the GAL-TAN dimension.

Second, trust and perceptions of corruption are other notoriously slow moving factors that structure preferences for EU vs national responses to the Covid-19 crises. Much in line with the ‘congruence’ or ‘equal assessment’ hypothesis (see Kritzinger Citation2003; Muñoz et al. Citation2011) we find that citizens rely heavily on domestic institutional cues – higher levels of trust in national level institutions lead to a greater willingness to share resources across borders. However, under control for national level political trust, we find that local political trust corresponds with preferences for a national economic response to the virus rather than an EU one. Also, interesting, we find evidence that perceptions of corruption negatively affect redistributive preferences to the crises. All things being equal, people who believe that others must engage in bribery to obtain public services could also believe that EU aid money would be siphoned off by local corrupt actors, instead of going to actually aiding citizens most in need (Bauhr and Charron Citation2018).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, our results suggest that support for EU economic integration in times of crisis is driven far more by long-standing values and beliefs than short-term reactions to the crisis. Surprisingly, perceptions of the Covid-19 crises as such has very little to do with preferences for a common EU response to the crisis versus a national response. This implies that many Europeans’ attitudes toward EU economic integration are hard to move in the short run. Thus, while the common financial package is motivated as a response to alleviate the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, those that worry the most about their personal economy (or health) in the wake of the crises are not more supportive of the package. We can only speculate why perceptions of personal threat neither pushes citizens towards preferring a strong national response or a strong international response. Whether this can be explained by these citizens never expecting to benefit from the funds or other factors is beyond the scope of this study, but it does indicate that motivating the package to assist the ones most in need might clearly resonate better with citizens that do not feel personally threatened by the crises.

REUS-2020-0257-File002.docx

Download MS Word (20.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Monika Bauhr

Monika Bauhr is an Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg and a Research Fellow at the Quality of Government (QoG) Institute. Her research focuses on public support for international aid and redistribution, democracy and the causes and consequences of different forms of corruption.

Notes

1 Green, alternative and libertarian (GAL), traditional, authoritarian, national (TAN).

3 Eurobarometer data on ‘Awareness of Regional Policy in the EU’ show that almost two third of respondents have not even heard of this policy. Also, some studies use EES data from 2014 that asks citizens a more general question: ‘In times of crisis, it is desirable for (OUR COUNTRY) to give financial help to another EU Member State facing severe economic and financial difficulties’. This question is helpful but not available for this year. The benefit of our own collected data on this is that it is posed in relation to a very concrete common crises and also that it seeks to avoid some of the social desirability issues introduced in the ESS question.

4 Initially, the fourth round of the pan-EU survey was scheduled to go into the field in April of 2020, yet due to the uncertainty of the pandemic, the main launch was delayed until fall 2020 and the smaller pilot was launched instead to assess the questions overall and to gauge the effects of Covid-19 on perceptions of institutional quality in general.

5 Although the question is presented in a format more common in an online survey, the mean (reversed) responses are 4.38 and 4.25 for the CATI and online responses respectively; a difference of means test shows the difference is not significant at the 0.05 level of confidence (p = 0.10).

6 Based on a principle component factor (PCF) analysis test, the three variables loaded onto a single in factor (Eigenvalue 1.59, proportion explained 0.62) All items re-scaled so higher values = more ’tan’. Weights from the PCF were used to aggregate the three measures into a single GAL-TAN index.

7 In addition to 3-level category of income, we test the effects using a decile measures (incomes bracketed into ten groups, relative to country income). We find no significant effects with this measure either.

8 Post-regression t-test shows the coefficient of gal-tan is statistically larger than either local, social trust (p = 0.000) or corruption perceptions (p = 0.000).

9 The standard deviation of the dependent variable is 2.2, and thus the marginal effect shown in for gal-tan for instance would be −0.36/2.2., or a (negative) 0.16. Standard deviation change in the dependent variable.

References

- Alesina, A. and La Ferrara, E. (2005) ‘Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities’, Journal of Public Economics 89(5–6): 897–931.

- Anderson, C. J. (1998) ‘When in doubt, use proxies: attitudes toward domestic politics and support for European integration’, Comparative Political Studies 31(5): 569–601.

- Armingeon, K. and Ceka, B. (2014) ‘The loss of trust in the European Union during the great recession since 2007: The role of heuristics from the national political system’, European Union Politics 15(1): 82–107.

- Arpino, B., & Obydenkova, A. V. (2020). Democracy and political trust before and after the great recession 2008: The European Union and the United Nations. Social Indicators Research 148: 395–415.

- Bakker, R. (2020) Who Opposes the EU? Continuity and Change in Party Euroscepticism Between 2014 and 2019, London, UK: LSE-The London School of Economics and Political Science – EUROPP.

- Bauhr, M. and Charron, N. (2018) ‘Why support International redistribution? Corruption and public support for aid in the Eurozone’, European Union Politics 19(2): 233–254.

- Bauhr, M. and Charron, N. (2020a) ‘The EU as a savior and a saint? Corruption and public support for redistribution’, Journal of European Public Policy 27(4): 509–527.

- Bauhr, M., and Charron, N. (2020b) ‘In God we trust? Identity, institutions and international solidarity in Europe', JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58: 1124–1143. doi:10.1111/jcms.13020.

- Baute, S., Abts, K. and Meuleman, B. (2019) ‘Public support for European solidarity: Between Euroscepticism and EU agenda preferences?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57(3): 533–550.

- Bechtel, M. M., Hainmueller, J. and Margalit, Y. (2014) ‘Preferences for international redistribution: The divide over the Eurozone bailouts’, American Journal of Political Science 58(4): 835–856.

- Beetsma, R. M. (2020) ‘What kind of EU fiscal capacity? Evidence from a randomized survey experiment in five European countries in times of corona’. In: Evidence From a Randomized Survey Experiment in Five European Countries in Times of Corona (July 26, 2020). Amsterdam Centre for European Studies Research Paper.

- Beramendi, P. and Anderson, C. J. (2008) Democracy, Inequality, and Representation in Comparative Perspective, New York City, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bobzien, L. and Kalleitner, F. (2021) ‘Attitudes towards European financial solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a net-contributor country’, European Societies 23 (1): S791–S804.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., et al. (2011) ‘Mapping EU attitudes: conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support’, European Union Politics 12(2): 241–266. doi:10.1177/1465116510395411.

- Bradburn, N. M. (1983) ‘Response effects’, Handbook of Survey Research 1: 289–328.

- Brasili, C., Calia, P. and Monasterolo, I. (2020) ‘Profiling identification with Europe and the EU project in the European regions’, Investigaciones Regionales = Journal of Regional Research 46: 71–91.

- Brigevich, A. (2018) ‘Regional identity and support for integration: An EU-wide comparison of parochialists, inclusive regionalist, and pseudo-exclusivists’, European Union Politics 19(4): 639–662.

- Charron, N. and Bauhr, M. (2020) ‘Do citizens support EU cohesion policy? Measuring European support for redistribution within the EU and its correlates', Investigaciones Regionales - Journal of Regional Research 46: 11–26.

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L. and Lapuente, V. (2014) ‘Regional governance matters: quality of government within European Union member states’, Regional Studies 48(1): 68–90.

- Charron, N., Lapuente, V. and Annoni, P. (2019) ‘Measuring quality of government in EU regions across space and time’, Papers in Regional Science 98(5): 1925–1953.

- Cicchi, L. (2020) ‘EU solidarity in times of Covid-19’.

- Daniele, G. and Geys, B. (2015) ‘Public support for European fiscal integration in times of crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy 22(5): 650–670.

- De Vaus, D. (2013) Surveys in Social Research, London, UK: Routledge.

- De Vries, C. E. (2018) Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dryhurst, S., Schneider, C. R., Kerr, J., Freeman, A. L., Recchia, G., Van Der Bles, A. M., Spiegelhalter, D. and van der Linden, S. (2020) ‘Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world', Journal of Risk Research 23(7–8): 994–1006.

- Feldman, S. and Zaller, J. (1992) ‘The political culture of ambivalence: Ideological responses to the welfare state', American Journal of Political Science 36 (1): 268–307.

- Fenger, M. and van Paridon, K. (2012) ‘Towards a globalisation of solidarity', in Reinventing Social Solidarity Across Europe, Bristol, UK: The Policy Press, pp. 49–70.

- Foster, C. and Frieden, J. (2017) ‘Crisis of trust: socio-economic determinants of Europeans’ confidence in government’, European Union Politics 18(4): 511–535.

- Gabel, M. (1998) ‘Public support for European integration: An empirical test of five theories’, The Journal of Politics 60(2): 333–354.

- Gabel, M. and Palmer, H. D. (1995) ‘Understanding variation in public support for European integration’, European Journal of Political Research 27(1): 3–19.

- Harteveld, E., van der Meer, T. and De Vries, C. E. (2013) ‘In Europe we trust? Exploring three logics of trust in the European Union’, European Union Politics 14(4): 542–565.

- Heinrich, T., Kobayashi, Y. and Bryant, K. A. (2016) ‘Public opinion and foreign aid cuts in economic crises’, World Development 77: 66–79.

- Hobolt, S. B. and De Vries, C. E. (2016) ‘Public support for European integration’, Annual Review of Political Science 19: 413–432.

- Hobolt, S. B. and Wratil, C. (2015) ‘Public opinion and the crisis: the dynamics of support for the euro’, Journal of European Public Policy 22(2): 238–256.

- Hoffmann, S. (1966) 'Obstinate or obsolete? The fate of the nation-state and the case of Western Europe', Daedalus 95 (3): 862–915.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2005) ‘Calculation, community and cues: public opinion on European integration’, European Union Politics 6(4): 419–443.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009) ‘A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining', British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1–23.

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G. and Wilson, C. J. (2002) ‘Does left/right structure party positions on European integration?’, Comparative Political Studies 35(8): 965–989.

- Kanthak, L. and Spies, D. C. (2018) ‘Public support for European Union economic policies’, European Union Politics 19(1): 97–118.

- Kleider, H. and Stoeckel, F. (2019) ‘The politics of international redistribution: explaining public support for fiscal transfers in the EU’, European Journal of Political Research 58(1): 4–29.

- Kobayashi, Y., Heinrich, T. and Bryant, K. A. (2020) ‘Public support for development aid during the COVID-19 pandemic’. Available at SSRN 3613320.

- Kritzinger, S. (2003) ‘The influence of the nation-state on individual support for the European Union’, European Union Politics 4(2): 219–241.

- Kuhn, T., Solaz, H. and van Elsas, E. J. (2018) ‘Practising what you preach: how cosmopolitanism promotes willingness to redistribute across the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(12): 1759–1778.

- Kuhn, T. and Stoeckel, F. (2014) ‘When European integration becomes costly: the euro crisis and public support for European economic governance’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(4): 624–641.

- Leppin, A. and Aro, A. R. (2009) ‘Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: theoretical foundations of current empirical research’, International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16(1): 7–29.

- Muñoz, J., Torcal, M. and Bonet, E. (2011) ‘Institutional trust and multilevel government in the European Union: congruence or compensation?’, European Union Politics 12(4): 551–574.

- Nicoli, F., Kuhn, T. and Burgoon, B. (2020) ‘Collective identities, European solidarity: identification patterns and preferences for European social insurance’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 58(1): 76–95.

- Paxton, P. and Knack, S. (2012) ‘Individual and country-level factors affecting support for foreign aid’, International Political Science Review 33(2): 171–192.

- Prati, G., Pietrantoni, L. and Zani, B. (2011) ‘Compliance with recommendations for pandemic influenza H1N1 2009: the role of trust and personal beliefs’, Health Education Research 26(5): 761–769.

- Rogers, R. W. (1975) ‘A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1’, The Journal of Psychology 91(1): 93–114.

- Rohrschneider, R. (2002) 'The democracy deficit and mass support for an EU-wide government', American Journal of Political Science 46(2): 463–475.

- Sánchez-Cuenca, I. (2000) ‘The political basis of support for European integration’, European Union Politics 1(2): 147–171.

- Serricchio, F., Tsakatika, M. and Quaglia, L. (2013) ‘Euroscepticism and the global financial crisis’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51(1): 51–64.

- Slovic, P. (2010) The Feeling of Risk: New Perspectives on Risk Perception, London, UK: Routledge.

- Stoeckel, F. and Kuhn, T. (2018) ‘Mobilizing citizens for costly policies: the conditional effect of party cues on support for international bailouts in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56(2): 446–461.

- Thorhallsson, B. and Rebhan, C. (2011) ‘Iceland’s economic crash and integration takeoff: an end to European Union scepticism?’, Scandinavian Political Studies 34(1): 53–73.

- Van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Kitayama, S., Mobbs, D., Napper, L. E., Packer, D. J., Pennycook, G., Peters, E., Petty, R. E., Rand, D. G., Reicher, S. D., Schnall, S., Shariff, A., Skitka, L. J., Smith, S. S., Sunstein, C. R., Tabri, N., Tucker, J. A., van der Linden, S., van Lange, P., Weeden, K. A., Wohl, M. J. A., Zaki, J., Zion, S. R. and Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5): 460–471.

- Van der Brug, W. and Van Spanje, J. (2009) ‘Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’ cultural dimension’, European Journal of Political Research 48(3): 309–334.

- Van Elsas, E. and Van Der Brug, W. (2015) ‘The changing relationship between left–right ideology and euroscepticism, 1973–2010’, European Union Politics 16(2): 194–215.

- Vasilopoulou, S. and Talving, L. (2020) ‘Poor versus rich countries: a gap in public attitudes towards fiscal solidarity in the EU’, West European Politics 43(4): 919–943.

- Verhaegen, S. (2018) ‘What to expect from European identity? Explaining support for solidarity in times of crisis’, Comparative European Politics 16(5): 871–904.

- Yang, J. Z. and Chu, H. (2018) ‘Who is afraid of the Ebola outbreak? The influence of discrete emotions on risk perception’, Journal of Risk Research 21(7): 834–853.