ABSTRACT

In today’s increasingly diverse societies, a key question is how to foster the structural integration of immigrants and their descendants. While research indicates that migrant educational underachievement is a serious issue, relatively little is known about achievement gaps at younger ages and in relatively new immigration countries. The current study sets out to estimate the size of disparities by migration background at age five (i.e. when they start school) and explores the causes of these gaps. It does so in a context that offers a compelling but under-researched case: the Republic of Ireland. It draws on the Growing Up in Ireland (GUI) data, a national longitudinal study of children in Ireland. The results suggest that some disparities by migration background already existed at the start of primary school, but also that gaps were limited to verbal skills and differed widely across groups. Moreover, social background only played a relatively minor role in explaining the differences, whereas the child’s first language was a powerful predictor of disadvantages by migration background in verbal skills.

EDITED BY:

Since the 1960s immigration has increased substantially (Castles, de Haas and Miller, Citation2014) and as a result many European countries have become much more diverse. The increased demographic diversity has brought up questions about the integration of immigrants and their descendants. One of these questions is how to facilitate the integration of students of migrant descent into the education system and to ensure that they have equal chances to succeed. Unsurprisingly, there is a large body of literature on the educational performance of students from minority groups and of migrant origin, which typically indicates that children with a migration background may be at risk of underperforming: students with a migration background tend to have poorer primary and secondary school grades, are less likely to complete secondary school, and attend shorter and less demanding school careers (e.g. Heath and Brinbaum, Citation2014).

Nevertheless, there seems to be quite a lot of variation with regards to achievement gaps by migration background. Several studies have found that such educational inequalities vary across countries. For example, looking at achievement disparities in several OECD countries, Dustmann, Frattini and Lanzara (Citation2012) showed that the average gap in test scores between children of immigrants and natives differed widely across countries. Similarly, there is evidence that such gaps vary within countries, differing across groups and conditions. For instance, exploiting three large international datasets, Andon, Thompson and Becker (Citation2014) found that the immigrant achievement gap is a very complex phenomenon and varies by grade and type of content (i.e. academic subject) assessed.

The variation in achievement gaps draws attention to the importance of considering the country context and looking less researched settings. Of particular interest are more recent countries of immigration that long remained understudied because their number of second-generation students was long too small to warrant systematic research (e.g. Heath, Rothon and Kilpi, Citation2008). More recently, researchers have started to fill this gap, investigating the achievement of students of migrant origin in contexts like Italy (e.g. Gabrielli, Longobardi and Strozza, Citation2021; Triventi, Vlach and Pini, Citation2021) and Spain (Vaquera and Kao, Citation2012; Zinovyeva, Felgueroso and Vazquez, Citation2014; e.g. Fierro et al., Citation2021). Such studies offer new insights into the processes that determine the educational disparities by migration background. For example, one interesting finding is that in new destination countries in Southern Europe the educational background of the parents seems to explain a smaller part of the educational disadvantages than in more established countries of immigration (Schnell and Azzolini, Citation2014).

The heterogeneity in achievement gaps also begs for studying a wider variety of age groups. While studies on educational inequality for older children and teenagers with a migration background are gaining momentum, research on the period prior to school and the early school years remains relatively scarce. In particular, based on school assessment data, such as PISA, it remains empirically unclear whether and to which extent gaps by migration background emerge in school or already exist at school entry. Moreover, as pointed out by Washbrook and colleagues (Citation2012, p. 1592) looking at achievement gaps by migration background in early childhood is helpful in assessing the effect of parental background. Besides, it is during this period early in the life course that interventions are likely most powerful and effective (Heckman, Citation2006).

This paper adds to the literature by investigating the existence of gaps by migration background and some of the causes of these gaps in early childhood in the Republic of Ireland (hereafter, Ireland). Drawing on the Growing Up in Ireland (GUI) data, a national longitudinal study of children in Ireland, this study sets out to answer the following questions:

Can differences in educational achievement between children with and without a migration background be observed at age five?

How important are differences in family social background and other theoretically relevant factors in explaining disparities by migration background in age five achievement?

The Irish context

Ireland provides an interesting context for studying immigrants and their children. The speed and scale of recent migration as well as the characteristics of its immigrant population make it different from many other Western countries. Most importantly, migration to Ireland is a relatively new phenomenon. For most of its history, Ireland was a country of emigration rather than of immigration. It was only during the economic boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s that Ireland turned into a country of net immigration. Many of those who moved to Ireland were young people looking to take advantage of the job opportunities offered by the thriving economy (Röder, Citation2014). As a result, there are relatively many young families with a migration background. The Irish Central Statistics Office estimated that, in 2017, only 77.3 per cent of the mothers of new-born babies were Irish nationals (CSO, Citation2018b). Furthermore, immigrants are, on average, higher educated than Irish natives (CSO, Citation2017), with 61.7% of the immigrants over 15 years of age having a third-level qualification (CSO, Citation2018a).

Evidence from Ireland

Research is still grappling with Ireland’s newly acquired status as a destination country. While there now is a considerable body of research that focuses on the experiences of children with a migration background in Ireland (e.g. Darmody et al., Citation2012), research looking at the academic performance of these children is still in its infancy, although steadily increasing.

Many of these studies indicate that Irish students with a migration background may fare relatively well. For example, Irish students with a migration background seem to resemble their Irish-born peers in educational outcomes (Taguma et al., Citation2009), rates of early school leaving (McGinnity et al., Citation2017), and their attitudes towards school and teachers (Smyth, Citation2017). In terms of achievement there are also some positive signs. McGinnity, Darmody and Murray (Citation2015) found some initial disadvantages for children of Eastern European, Western European and Asian mothers, but reported relatively modest differences in academic performance between Irish-born and immigrant children at age nine after accounting for background characteristics. Moreover, some country-comparative studies found that first and 1.5 generation students may even outperform their native counterparts in Ireland (Levels and Dronkers, Citation2008; Levels, Dronkers and Jencks, Citation2017). However, there are also some reasons for concern: children with a migration background in Ireland are more likely to live in specific urban areas (Devine, Citation2011, Citation2013) and to be concentrated in schools serving socioeconomically disadvantaged groups (Byrne et al., Citation2010).

While the existing evidence from the Irish context suggests that achievement gaps by migration background may be relatively modest, it is important to note that this is largely based on qualitative evidence, older and first-generation children as well as generations of children born before the accession of new EU member states in 2004, which significantly altered the immigrant population in Ireland (Röder, Citation2014; Devitt, Citation2016). Thus, in many regards, much remains unknown about the Irish situation. Hence, for our expectations we predominantly draw on findings from other, more traditional countries of immigration.

Evidence from other countries

Despite significant variation (Dustmann, Frattini and Lanzara, Citation2012; Andon, Thompson and Becker, Citation2014), many studies on the educational performance of students of migrant origin indicate that these children and young people face disadvantages and that their academic achievement is typically lower than that of their peers without a migration background (Levels and Dronkers, Citation2008; e.g. Alba, Sloan and Sperling, Citation2011; Heath and Brinbaum, Citation2014; Schnell and Azzolini, Citation2014). Following the notion that earlier achievement is highly predictive of later achievement (Duncan et al., Citation2007), we may expect such differences to be present in early childhood as well. Indeed, there is some evidence that migration-achievement gaps already manifest themselves in early in life (Magnuson, Lahaie and Waldfogel, Citation2006; Washbrook et al., Citation2012; e.g. Becker, Klein and Biedinger, Citation2013; Hahn and Schöps, Citation2019; Becker and Klein, Citation2021). Therefore, we expect that, on average, Irish 5-year-olds with a migration background will have lower test scores than their counterparts born to native parents, i.e. a raw gap (H1a).

However, considering the diversity in the Irish immigrant population, these gaps may not be the same across all migrant groups. Importantly, children with a parent from the Anglosphere may be more similar to children with Irish-born parents due to the shared historical and cultural ties of these countries. Moreover, due to restricted non-EU immigration into Ireland, some non-EU migrant groups may be more positively selected than those that could move to Ireland more easily, such as immigrant from recently acceded EU countries. This is relevant because for more positively selected immigrant groups the educational disadvantages of the second generation tend to be smaller (e.g. van de Werfhorst and Heath, Citation2019). Thus, we expect that disadvantages will be the smallest for children with a parent from the Anglosphere and largest for those with a Polish or other Eastern European parent (H1b).

Arguably the most important migration-specific factor related to achievement is language. Children whose parents do not speak the majority language at home have fewer opportunities to master it and their lower language proficiency might hamper them in their schoolwork (Schnell and Azzolini, Citation2014). Moreover, speaking the majority language at home may be an indication of integration or cultural proximity, and not being fluent in the majority language may form a barrier to parental involvement at school (Turney and Kao, Citation2009). Correspondingly, studies looking at achievement in early childhood have sometimes found that gaps exist for verbal skills but not for non-verbal skills (Washbrook et al., Citation2012; Becker, Klein and Biedinger, Citation2013). Thus, we expect achievement gaps by migration background to be larger for verbal than for non-verbal skills (H1c). Additionally, we expect that the language spoken at home will largely explain these gaps (H2).

Compositional factors

Sociologists have long highlighted the association between social background and educational outcomes (e.g. Breen and Jonsson, Citation2005) and family investment theory highlights the role of socioeconomic resources such as income or education for differences in parents’ capacity to invest into children’s development (e.g. Conger and Donnellan, Citation2006). Since immigrants frequently occupy the lower socioeconomic strata in host societies, it may be the socioeconomic resources available to migrant parents and not their migrant status per se, which shape their offspring’s educational opportunities (e.g. Heath and Brinbaum, Citation2007). Therefore, we hypothesise that accounting for parental education and the household income will reduce any existing achievement gaps by migration background (H3a and H3b).

Additionally, it may be useful to consider a wider range of resources and investments than parental education and income. Coleman (Citation1988) already pointed to the idea that the mere presence of resources (in his case human capital) does not automatically translate into the transmission to the offspring but that this requires specific investments and behaviour. Many researchers have since shown that parenting styles and practices are important in explaining learning and school success of children, and that they may be one of the main mechanisms through which the background of the parents affects children’s educational success (e.g. Lareau, Citation2011). Therefore, we hypothesise that any disparities between children with and without a migration background can further be explained by non-monetary forms of parental resources and investments, such as educational activities (H4).

Moreover, immigrant parents may be disadvantaged in terms of mental health and social support. The migration process may be stressful and disruptive, which in line with the family stress model (Conger and Conger, Citation2002) could negatively affect parenting and consequently the child’s academic achievement. Relatedly, moving to and settling in a new country means leaving one’s home country, including one’s existing social networks, which makes that, unlike native parents, immigrant parents cannot easily rely on old kinship networks for support in child rearing. Therefore, we expect that accounting for maternal mental well-being and perceived social support will further reduce any disparities by migration background (H5a and 5b).

Finally, in addition to the home environment, environments outside of the household are likely relevant to child development. A large body of literature demonstrates the positive effects of early childhood education and care (ECEC) participation on child development (For reviews see for example Burger, Citation2010; Kulic et al., Citation2019). ECEC participation might be particularly beneficial to children of immigrants because it provides them with the opportunity to come in contact with the majority culture and the language (Magnuson and Waldfogel, Citation2005). However, research suggests that maternal work and childcare decisions differ by migration status in Ireland (Röder, Ward and Frese, Citation2017) and children with a migration background may be less likely to be in non-parental care. Hence, we expect that accounting for preschool attendance will reduce disparities by migration background (H6).

Data and methods

The Growing Up in Ireland study

To test our hypotheses, we drew on the GUI Infant Cohort data. We primarily focused on the third data wave of data collection, conducted when the study children were five years of age (Williams et al., Citation2019). This is a crucial age because primary school is commonly started at age four or five in Ireland. Moreover, the GUI study was nationally representative, drawn from the Irish Child Benefit Register, and, thus, there was a representative number of children with a migration background in the sample.

The children in the Infant Cohort were born between December 2007 and June 2008. Of the 11.134 families that were surveyed in Wave 1 (9 months), 9793 participated in Wave 2 (age three), and 9001 in Wave 3 (age five). In early 2013, detailed interviews for Wave 3 were conducted with the primary caregiver who, in nearly all cases, was the mother, and the secondary caregiver if resident in the household. The questionnaire included measures on children’s achievement as well as a wide range of measures on their circumstances and detailed information from their caregivers.

Measures

Naming vocabulary and picture similarity tests

Our dependent variables were the study child’s verbal and non-verbal skills at age five (Wave 3). They were assessed using two of the core scales from the Early Years Battery of the British Ability Scales (Elliott, Smith & McCullough, Citation1996): the Naming Vocabulary and Picture Similarity test. These tests have also been used in other large cohort studies, such as the Millennium Cohort Study, and were extensively tested in the Irish context before being used in the GUI study (Murray, McCrory and Williams, Citation2014; Thornton and Williams, Citation2016).

Both tests were administered in the family home at the same time as the interview with the primary caregiver. In the Naming Vocabulary test, the child was shown a series of pictures of objects and was asked to name them. This served as a measure of expressive English language vocabulary (i.e. verbal skills). In the Pictures Similarities test, the child was shown a row of pictures and was asked to identify a further congruent picture. This process served as measured for non-verbal reasoning capacity and problem-solving skills (i.e. non-verbal skills).

The raw scores (i.e. the number of correct items for each test) were converted into ability scores, considering the difficulty of the items and the ability of the child. Based on tables provided by the test authors (Elliott, Smith and McCulloch, Citation1996), these were then transformed into age-adjusted standardised test scores, with a mean of 50, a standard deviation of 10, and bounded between 20 and 80.

Parental region of origin

Our indicator of migration background was the parents’ region of origin. Parents were asked to indicate their country of birth at Wave 1. To reduce missing values, responses to this question from later waves were used if the information was missing in Wave 1 and the respondent in the later wave was listed as a parent.

Using this information, we then created a region of origin variable for the study child. If the study child had one foreign-born parent residing in the household, the birthplace of the migrant parent was taken. If the child had two foreign-born parents that were both living in the household, the mother’s birthplace was used. For anonymisation purposes, we collapsed birth countries so that ten categories remained: (1) Republic of Ireland; (2) United Kingdom (including Northern Ireland); (3) Poland; (4) Other EU – Western; (5) Other EU – Eastern; (6) Africa; (7) Indian Subcontinent; (8) Other Asia; (9) North-America, Australia, Oceania; and (10) Rest of the world.

Parental education level

A dominance approach was used to assess the highest level of parental education, recorded in Wave 3: (1) Degree or higher; (0) Non-degree or below.

Household income

Because the household income may fluctuate over time, we used the log-transformed equivalised annual household income (in euros), averaged across the three waves. This was based on the self-reported disposable household income (i.e. the total gross household income less statutory deductions of income tax and social insurance contributions) divided by the equivalised household size. We log-transformed the variable because the data were right-skewed.

Frequency educational activities

As one aspect of other parental resources and investments, we included a measure of the frequency educational activities. In Wave 2, parents indicated how many days per week they or anyone else did certain activities with the child, such as reading to the child or helping them learn the ABC. We combined the seven items by taking the average, meaning that scores ranged from 0 to 7 with higher scores indicating a greater frequency.

Number of books

As a second aspect of other parental resources and investments, we included a measure on the number of books the child had access to in their home at Wave 2: (1) Up to 20; (2) 21-30; (3) 30 or more.

Hours in preschool

As a measure of ECEC attendance, we included the number of hours children spent in preschool under the Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) Scheme of the Irish government, recorded in Wave 2.

Child’s first language

The primary caregiver reported the first language of the child at Wave 2: (0) English; (1) Other language than English (including Irish).Footnote1

Maternal mental health

For the mental well-being of the parents, we included the depression score of the primary caregiver at Wave 2, with a higher score indicating worse mental health.

Perceived social support

In Wave 2, the primary caregiver reported the overall level of support they received from family or friends outside of the household. Based on this, we created a dummy indicating whether they felt like they received (1) enough support or (0) not.

Control variables

We controlled for the age and sex of the study child, whether the study child had started school at the time of the test, the age of the mother, whether the study child lived in a single-parent household, the number of siblings in the household, and the region of residence.

Sample

After drawing on information from later waves as far as possible, information on the parental region of birth was missing for 481 children of the total sample of 9001. To avoid uncertainty in our groups of children with and without a migration background, we conditioned the sample on those children for whom we had information on their parents’ region of birth (N = 8520).

The children in our final sample were between 60 and 68 months old (M = 62.03, SD = 0.96) and 49.18% was female. There was a meaningful and relatively diverse proportion of children with a migration background in our sample. More than one in four (30.72%) students had at least one parent that was foreign-born. The UK (35.58%), Africa (13.76%), and Poland (13.60%) were among the most common birth regions of foreign-born parents. A small number of children (N = 74) were born abroad themselves but moved to Ireland before they were nine months old. Most of them (N = 43) had Irish-born parents, while 31 of them had at least one parent that was also foreign-born. Detailed descriptive statistics for the key variables by parental region of birth are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the main explanatory variables by parental region of origin.

Method of analysis

We performed our analyses in three steps. In a first step, we estimated the unconditional means in verbal and non-verbal skills to assess raw gaps by parental region of birth. In a second step, we employed multiple linear regression models in a stepwise fashion. We started with regressing verbal and non-verbal skill scores on the child’s migration background and the control variables, and step by step, added the other sets of variables. In a final step, we used structural equation modelling (SEM) to gauge what part of the disparities could be explained by the variables. We estimated how much of the differences by parental region of birth (i.e. the total effects) could be attributed to our explanatory variables (i.e. the indirect effects), conditioning on the study child’s age and sex and the region of residence.

To deal with potential bias from attrition and sample design, we conducted all our analyses on weighted samples, using the weighting factor provided in the GUI dataset for the most complete 5-year sample of 9,001 families. This factor considered key socio-demographic and other dimensions, as well as inter-wave attrition.

Missing data were relatively limited and varied from 0.09% for the control variable indicating whether the child was already in school to 3.19% for the perceived social support variable. At 16.09%, the only variable with more missing values was the average equivalised household income, which was because it had between 408 and 675 missing values in each wave. To account for missing data, we performed multiple imputation to create 20 additional datasets with plausible values for missing values, using the Multivariate Imputation using Chained Equations (MICE) procedure in Stata 15 (Royston and White, Citation2011) with the option augment (White, Daniel and Royston, Citation2010). The imputation model included all variables included in the regression models as well as four auxiliary variables. In the SEM, we used Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). Results from the analyses using MICE and FIML were nearly identical. A replication package is available on the journal’s website.

Results

Raw achievement gaps

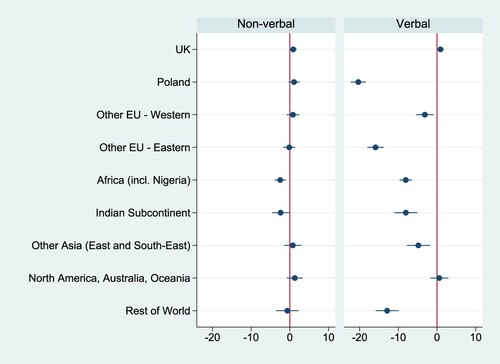

Contrary to our expectations, raw (i.e. unadjusted) achievement gaps between children with Irish-born and the groups of children with foreign-born parents generally did not occur for non-verbal skills (see ). There were three exceptions to this. Children with a parent from Africa or the Indian subcontinent scored about a quarter of a standard deviation lower than children with parents that were born in Ireland, whereas children with a parent from the United Kingdom scored about a tenth of a standard deviation above them.

Figure 1. Estimated unadjusted mean differences in verbal and non-verbal skills at age 5 by parental region of birth. Note. Reference group is Ireland. Weighted data, M = 20 imputations.

Unadjusted group differences in verbal skills were more pronounced. On average, most groups of children with a migration background had lower scores than their peers with native parents, although there were considerable differences by the birth region of the parents. Perhaps unsurprisingly, children who had a parent from a primarily English-speaking area (i.e. the UK and North America, Australia and Oceania) tended to have scores close to or slightly higher than the average. Lower than average achievement scores, on the other hand, could be observed for all other regions. Disadvantages were most severe for children with a Polish or other Eastern European background; their scores were close to two and one-and-a-half standard deviations below the mean of children with an Irish parent, respectively.

Thus, in partial support of our first hypothesis, we found raw gaps in verbal skills for most groups. As expected, the test scores of children with a parent from an Anglosphere core country were similar to children with Irish-born parents. For all other origin groups the average verbal skill scores were lower than those of children without a migration background and, as hypothesised, they were the largest for those with an Polish or Eastern European parent. Finally, in line with expectations, differences were more pronounced for verbal than non-verbal skills. In fact, there were barely any gaps by migration background in non-verbal skills. With few observed differences in non-verbal skills, there were also fewer gaps to explain, but it could be that that any migrant-specific advantages appear after taking into account theoretically relevant factors. We investigated this in the section below.

Adjusted gaps by migration background

To the base model ( and , M1), which only included the parental region of birth and the control variables, we added the first language of the child (M2). Having another first language than English was significantly and negatively related to verbal skills, though not to non-verbal skills. The penalty for not having English as a first language was rather large at −11.43 points, and verbal skill disadvantages were significantly reduced once differences in the child’s first language were taken into account. In some cases, the remaining gaps were only around half of their initial size. This was, for example, the case for children with a parent from Poland and other Eastern European countries. For children with a parent from Western Europe, the Indian subcontinent and other parts of Asia, the initial gap was even no longer significant.

Table 2a. Stepwise regression models for verbal skills at age five.

Table 2b. Stepwise regression models for non-verbal skills at age five.

In the subsequent model, we included the parental education variable (M3) followed by the household income (M4). As expected, children born to parents with higher levels of education and in more affluent households tended to do better than children whose parents held lower levels of education and whose household income was lower. However, including these variables generally did not reduce the existing achievement gaps by migration background, even not when using less crude measures of social background.Footnote2 If anything, considering parental education might even have enlarged some of the gaps. This was, for example, the case for children with a parent from Poland and other Western and Eastern European countries.

In the next model (M5), we entered the indicators of other parental resources and investments. Including these measures slightly decreased the existing gaps by migration background. For example, for children with an Eastern European background the gap in verbal skills reduced from −8.16 to −7.40, and for children with an African background from −5.32 to −4.55. However, the reduction in the gaps was generally small. Thus, while other familial resources and investments seemed to matter for children’s achievement, they did not seem to play a major role in explaining disparities by migration background.

In the final model (M6), we added perceived social support, maternal mental health, and preschool hours. The latter two were not associated with verbal nor non-verbal skills. However, support of social networks seemed to matter, and accounting for the level of reported support reduced some of the initially observed disparities by migration background, though changes were again modest. For example, the disadvantage of children with a Polish parent only reduced from −10.62 to −10.50.

All in all, we found mixed support for our hypotheses. The child’s first language had the most explanatory power, but this only held true for verbal skills. The household income and parents’ educational credentials were associated with both verbal and non-verbal skills but typically only accounted for small parts of the differences by parental region of birth. Similarly, other resources and investments as well as perceived social support mattered but they only mildly reduced existing disparities in achievement by migration background. The number of preschool hours and maternal mental health were not related to achievement at all.

Relative importance of the explanatory variables

To further understand the role of our explanatory variables, we ran an additional analysis in which we used SEM to estimate what part of the effect of each parental region of birth could be explained by the included variables (see Table S2 in the supplementary materials). This allowed us to estimate what part of the disparities by migration background could be explained by the variables in our model more precisely.

The results of the SEM analysis underlined the relatively different role of social background in explaining any disadvantages by migration background compared to other countries of immigration. The household income only explained relatively small parts of the relatively large disadvantages experienced by some groups. For example, children with a Polish parent had verbal skill scores that were, on average, nearly two standard deviations below those of their peers with native Irish parents. However, only about 2% of this disadvantage could be explained by the household income. Similarly, children with an Indian background had scores that were roughly four-fifths of a standard deviation lower but only 4% of this difference was explained by the household income. Parental education, in some cases, even suppressed some of the disadvantages, suggesting that the migrant gap would be slightly larger if immigrant parents had educational credentials comparable to the Irish population. For instance, for children with a Western European parent, the disadvantage would likely have been about 11% larger if their parents had not been as highly educated.

Finally, the SEM results also highlighted the important role of language. The child’s first language was by far the most important contributor to any disadvantages (or advantages) by migration background. Overall, this variable explained between 23 and 91 per cent of the significant differences in verbal skills, with it appearing to be most important for children of Indian and Western European origin. However, it is critical to note again that for non-verbal skills there were no substantial disparities to start with and they were not affected by the child’s first language.

Discussion

Research is still catching up with Ireland’s newly acquired position as a country of immigration. This study used a nationally representative sample of 5-year-olds to add to the growing literature on the educational achievement of children with a migration background in Ireland, and relatively new countries of destination more generally. It also added to the knowledge of achievement gaps by migration background at younger ages, and extended the literature, which has largely relied on cross-sectional data, by using lagged measures for several explanatory variables.

Our results indicated that disparities existed for children from some groups at the start of school in Ireland but also that they were mostly limited to verbal skills. At age five there were virtually no disparities in non-verbal skills, although there were modest disadvantages for children with a caregiver from Africa and the Indian subcontinent. For verbal skills, the picture was less rosy. At the start of primary school, children from several immigrant groups had achievement scores that were substantially below those of their peers with native parents, albeit these differences varied markedly by the parental region of origin. In line with our expectations, the disadvantages were largest for students with a parent from Poland or another Eastern European country, while differences were non-existent for children from the Anglosphere.

The difference in disparities by migration background between verbal and non-verbal skills is noteworthy and hints at the fact that it is mainly the more culturally and context-dependent skills that are of concern in early childhood. In line with findings in other Anglo-Saxon countries (Washbrook et al., Citation2012), Irish children with a migration background may perform on par with children without a migration background in terms of more general skills. However, they might be outperformed in terms of skills that are more specific to Ireland. This may be particularly true if a language other than English is spoken at home, which, as predicted, was found to be the most important predictor of disparities by migration background at age five in Ireland.

Considering that verbal skill gaps could already be detected at the start of primary school, increasing or expanding ECEC attendance might be a likely policy intervention, especially as it may be particularly beneficial to children who do not speak English at home (Burger, Citation2012; Klein and Becker, Citation2017). However, the current study found no support for a general effect of the time spent in preschool during the free preschool year in Ireland. This might be because the free ECEC programme started too late or was too short to have an effect on language skills. Another explanation may be that the quality of the ECEC provided through the free preschool year in Ireland was not high enough, which was not adequately captured in the relatively crude measures used in the current study. Future research should therefore include more detailed measures of ECEC attendance and explore these and other possible explanations to understand whether ECEC could function as an equaliser.

Furthermore, differences by parental birth region were pronounced and rather persistent for some groups. Notably, even after including a range of theoretically relevant factors, children with a Polish caregiver had verbal skill scores that quite were far below the average. One potential explanation could be that some immigrant groups choose not to assimilate into Irish society as a whole but into a particular segment where they can preserve culture and values and utilise their ethnic capital (Portes and Zhou, Citation1993; Portes and Rumbaut, Citation2001). In such a case, the child would likely be less exposed to the majority language. While beyond the scope of the current study, it would be worthwhile to investigate the possible causes of group differences in more detail. Fruitful avenues for future research may be exploring the effect of the level of interethnic contact and the parents’ level of integration on children’s educational performance, as has been done in the German context (Becker, Klein and Biedinger, Citation2013) as well as exploring the effects of bilingualism. Furthermore, it would be useful to consider the role of educational selectivity of the migrant population, which may be an important potential source of differences among immigrant groups and has been shown to be related to educational outcomes of the second generation (e.g. van de Werfhorst and Heath, Citation2019).

The current results underline findings by earlier studies that the role of socio-economic factors varies markedly across countries (Marks, Citation2005), while also highlighting the distinctive role that parental background may play in relatively new countries of immigration. Social background only accounted for a relatively small part of the lower performance of Irish children of some migrant groups. Particularly parental education was a weak predictor of the disadvantages by migration background. In fact, if Irish migrant parents would have had the same levels of education as Irish-born parents, the gaps may have been larger. While the household income had some more predictive power, it could still only explain a modest part of the gaps by migration background. This is at odds with most of the existing literature from more established countries of immigrant as well as the findings of Schnell and Azzolini (Citation2014) from Southern Europe which highlighted the relative importance of ‘economic’ family resources. More research on role of social background in the achievement of students of migrant descent in newer countries of immigration is thus warranted.

Finally, while the present study added an important early childhood perspective to the literature, it only offered a snapshot of achievement at age five and was limited to two outcome measures. The findings suggested that language-related gaps found by studies in other European contexts at later ages might find their roots in early childhood. However, as Heath, Rothon and Kilpi (Citation2008, p. 229) noted, patterns of disadvantage differ at various stages of the educational career and tend to be most evident with test scores early in the school career. It remains an open question how these gaps will develop and what patterns look like for other outcomes.

Conclusion

This study offered insights into early disparities by migration background in a unique study context. From a country of emigration, Ireland has become a country of immigration and the resulting diversity is reflected in its schools. Our results suggest that some achievement differences by migration background already exist at the start of primary school, although they might be limited to verbal skills and differ widely by the group under study. Moreover, social background only seems to explain a relatively minor part of these differences, which is at variance with much of the existing literature. Further research looking at the educational trajectory of these children is needed to better understand why these gaps exist, how they develop, and if they might be prevented.

REUS-2021-0144-File003.pdf

Download PDF (300.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stefanie Sprong

Stefanie Sprong is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Trinity College Dublin. Her primary research interests lie in the field of interdisciplinary and comparative studies of the integration of immigrants and their descendants.

Jan Skopek

Dr. Jan Skopek is assistant professor at the Department of Sociology of Trinity College Dublin. His research activities are located in social stratification research, family research, social demography, quantitative social research methodology, longitudinal and cross-national research, as well as digital social research.

Notes

1 While Irish and English are both official languages of Ireland, English is by far the most commonly spoken language. Moreover, the test assessing the study child’s verbal skills is conducted in English. Therefore, we have included Irish in other language spoken at home.

2 Because this is an important finding, which is at odds with much of the existing literature, we must be confident in it and make sure it is not driven by our choice to operationalise parental educational as a binary variable. Thus, we ran two additional models: One with a more detailed measure of parental education, and one with a measure of social class in addition to the more detailed parental education measure. Results were very similar to the results from the main analyses and can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1a and S1b).

References

- Alba, R., Sloan, J. and Sperling, J. (2011) ‘The integration imperative: the children of Low-status immigrants in the schools of wealthy societies', Annual Review of Sociology 37: 395–415. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150219.

- Andon, A., Thompson, C. G. and Becker, B. J. (2014) ‘A quantitative synthesis of the immigrant achievement gap across OECD countries', Large-scale Assessments in Education 2(1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40536-014-0007-2.

- Becker, B. and Klein, O. (2021) ‘The primary effect of ethnic origin – rooted in early childhood? An analysis of the educational disadvantages of Turkish-origin children during the transition to secondary education in Germany', Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 75: 100639. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100639.

- Becker, B., Klein, O. and Biedinger, N. (2013) ‘The development of cognitive, language, and cultural skills from age 3 to 6', American Educational Research Journal 50(3): 616–649. doi:10.3102/0002831213480825.

- Breen, R. and Jonsson, J. O. (2005) ‘Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: recent research on educational attainment and social mobility', Annual Review of Sociology. Annual Reviews 31(1): 223–243. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122232.

- Burger, K. (2010) ‘How does early childhood care and education affect cognitive development? An international review of the effects of early interventions for children from different social backgrounds', Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25(2): 140–165. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.11.001.

- Burger, K. (2012) ‘Do effects of center-based care and education on vocabulary and mathematical skills vary with children’s sociocultural background? disparities in the use of and effects of early childhood services.’', International Research in Early Childhood Education. ERIC 3(1): 17–40.

- Byrne, D., McGinnity, F., Smyth, E. and Darmody, M. (2010) ‘Immigration and school composition in Ireland', Irish Educational Studies 29(3): 271–288. doi:10.1080/03323315.2010.498567.

- Castles, S., de Haas, H. and Miller, M. J. (2014) The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 5th ed, 5th editio, New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988) ‘Social capital in the creation of human capital', American Journal of Sociology. The University of Chicago Press 94: S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943.

- Conger, R. D. and Conger, K. J. (2002) ‘Resilience in midwestern families: selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal Study', Journal of Marriage and Family. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 64(2): 361–373. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x.

- Conger, R. D. and Donnellan, M. B. (2006) ‘An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development', Annual Review of Psychology. Annual Reviews 58(1): 175–199. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551.

- CSO (2017) ‘Census of Population 2016 – Profile 7 Migration and Diversity’. Dublin, Ireland: Central Statistics Offce (CSO). Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp7md/p7md/p7se/.

- CSO (2018a) ‘Population and Migration Estimates April 2018’. Dublin: Central Statistics Offce (CSO). Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/er/pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2018/.

- CSO (2018b) ‘Vital Statistics Yearly Summary 2017’. Dublin: Central Statistics Offce (CSO). Available at: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-vsys/vitalstatisticsyearlysummary2017/.

- Darmody, M., Smyth, E., Byrne, D. and McGinnity, F. (2012) 'New school, new system: The experiences of immigrant students in Irish schools BT - International handbook of migration, minorities and education: Understanding cultural and social differences in processes of Learning', in Z. Bekerman and T. Geisen (eds.), Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 283–299.

- Devine, D. (2011) Securing Migrant Children’s Educational Well-Being, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Sense, pp. 71–87.

- Devine, D. (2013) ‘‘Value’ing children differently? migrant children in education', Children & Society. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111) 27(4): 282–294. doi:10.1111/chso.12034.

- Devitt, C. (2016) ‘Mothers or migrants? labor supply policies in Ireland 1997–2007', Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 23(2): 214–238. doi:10.1093/sp/jxv034.

- Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., Pagani, L. S., Feinstein, L., Engel, M., Brooks-Gunn, J. and Sexton, H. (2007) ‘School readiness and later achievement', Developmental Psychology. American Psychological Association 43(6): 1428–1446. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428.

- Dustmann, C., Frattini, T. and Lanzara, G. (2012) ‘Educational achievement of second-generation immigrants: an international comparison*', Economic Policy 27(69): 143–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00275.x.

- Elliott, C. D., Smith, P. and McCulloch, K. (1996) The British Ability Scales II, Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON.

- Fierro, J., Parella, S., Güell, B. and Petroff, A. (2021) ‘Educational achievement among children of latin American immigrants in Spain', Journal of International Migration and Integration, doi:10.1007/s12134-021-00918-x.

- Gabrielli, G., Longobardi, S. and Strozza, S. (2021) ‘The academic resilience of native and immigrant-origin students in selected European countries', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Routledge, 1–22. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1935657.

- Hahn, I. and Schöps, K. (2019) ‘Bildungsunterschiede von anfang an?', Frühe Bildung. Hogrefe Verlag 8(1): 3–12. doi:10.1026/2191-9186/a000405.

- Heath, A. and Brinbaum, Y. (2014) Unequal Attainments: Ethnic Educational Inequalities in ten Western Countries, Proceedings of the British Academy, Oxford: Oxford University Press for the British Academy.

- Heath, A. and Brinbaum, Y. (2007) ‘Guest editorial: explaining ethnic inequalities in educational attainment', Ethnicities. SAGE Publications 7(3): 291–304. doi:10.1177/1468796807080230.

- Heath, A., Rothon, C. and Kilpi, E. (2008) ‘The second generation in Western Europe: education, unemployment, and occupational attainment', Annual Review of Sociology. Annual Reviews 34(1): 211–235. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728.

- Heckman, J. J. (2006) ‘Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children', Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science 312(5782): 1900–1902. doi:10.1126/science.1128898.

- Klein, O. and Becker, B. (2017) ‘Preschools as language learning environments for children of immigrants. differential effects by familial language use across different preschool contexts', Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Elsevier 48: 20–31. doi:10.1016/J.RSSM.2017.01.001.

- Kulic, N., Skopek, J., Triventi, M. and Blossfeld, H. P. (2019) ‘Social background and children’s cognitive skills: the role of early childhood education and care in a cross-national Perspective', Annual Review of Sociology 45(1): 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022401.

- Lareau, A. (2011) Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

- Levels, M. and Dronkers, J. (2008) ‘Educational performance of native and immigrant children from various countries of origin', Ethnic and Racial Studies 31(8): 1404–1425. doi:10.1080/01419870701682238.

- Levels, M., Dronkers, J. and Jencks, C. (2017) ‘Contextual explanations for numeracy and literacy skill disparities between native and foreign-born adults in western countries', PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science 12(3): e0172087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172087.

- Magnuson, K., Lahaie, C. and Waldfogel, J. (2006) ‘Preschool and school readiness of children of immigrants', Social Science Quarterly. Wiley Online Library 87(5): 1241–1262. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00426.x.

- Magnuson, K. and Waldfogel, J. (2005) ‘Early Childhood care and education: effects on ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness', The Future of Children. Princeton University 15(1): 169–196. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1602667.

- Marks, G. N. (2005) ‘Accounting for immigrant non-immigrant differences in reading and mathematics in twenty countries', Ethnic and Racial Studies. Routledge 28(5): 925–946. doi: 10.1080/01419870500158943.

- McGinnity, F., et al. (2017) Monitoring report on integration 2016. Edited by A. Barrett, F. McGinnity, and E. Quinn. Dublin.

- McGinnity, F., Darmody, M. and Murray, A. (2015) Academic achievement among immigrant children in Irish primary schools. 512. Dublin. Available at: www.econstor.eu.

- Murray, A., McCrory, C. and Williams, J. (2014) Report on pre-pilot, pilot and dress rehearsal exercises for phase 2 of the infant cohort at age three years. Dublin. Available at: https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/BKMNEXT312.pdf.

- Portes, A. and Rumbaut, R. G. (2001) Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation, Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

- Portes, A. and Zhou, M. (1993) ‘The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants', The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. SAGE Publications Inc 530(1): 74–96. doi:10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Röder, A. (2014) ‘The emergence of a second generation in Ireland: some trends and open Questions', Irish Journal of Sociology. SAGE Publications Ltd 22(1): 155–158. doi:10.7227/IJS.22.1.11.

- Röder, A., Ward, M. and Frese, C.-A. (2017) ‘From labour migrant to stay-at-home mother? childcare and return to work among migrant mothers from the EU accession countries in Ireland', Work, Employment and Society. SAGE Publications Ltd 32(5): 850–867. doi:10.1177/0950017017713953.

- Royston, P. and White, I. R. (2011) ‘Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE): implementation in Stata', Journal of Statistical Software 45(4): 1–20.

- Schnell, P. and Azzolini, D. (2014) ‘The academic achievements of immigrant youths in new destination countries: evidence from Southern Europe', Migration Studies 3(2): 217–240. doi:10.1093/migration/mnu040.

- Smyth, E. (2017) Off to a good start? Primary school experiences and the transition to second-level education | ESRI. Dublin. Available at: https://www.esri.ie/publications/off-to-a-good-start-primary-school-experiences-and-the-transition-to-second-level (Accessed: 20 August 2019).

- Taguma, M., Kim, M., Wurzburg, G. and Kelly, F. (2009) OECD Reviews of Migrant Education, Ireland, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Thornton, M. (ESRI) and Williams, J. (ESRI) (2016) Report on the Pilot Phase of Wave Three, Infant Cohort (at 5 Years of Age). Dublin. Available at: https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/BKMNEXT331.pdf.

- Triventi, M., Vlach, E. and Pini, E. (2021) ‘Understanding why immigrant children underperform: evidence from Italian compulsory education', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Routledge, 1–23. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1935656.

- Turney, K. and Kao, G. (2009) ‘Barriers to school involvement: are immigrant parents disadvantaged?', The Journal of Educational Research. Routledge 102(4): 257–271. doi:10.3200/JOER.102.4.257-271.

- Vaquera, E. and Kao, G. (2012) ‘Educational achievement of immigrant adolescents in Spain: do gender and region of origin matter?', Child Development. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 83(5): 1560–1576. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01791.x.

- Washbrook, E., Waldfogel, J., Bradbury, B., Corak, M. and Ghanghro, A. A. (2012) ‘The development of young children of immigrants in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States', Child Development. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 83(5): 1591–1607. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01796.x.

- van de Werfhorst, H. G. and Heath, A. (2019) ‘Selectivity of migration and the educational disadvantages of second-generation immigrants in Ten host Societies', European Journal of Population. Springer Netherlands 35(2): 347–378. doi:10.1007/s10680-018-9484-2.

- White, I. R., Daniel, R. and Royston, P. (2010) ‘Avoiding bias due to perfect prediction in multiple imputation of incomplete categorical variables', Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 54(10): 2267–2275. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2010.04.005.

- Williams, J., Thornton, M., Murray, A. and Quail, A. (2019) Design, Instrumentation and Procedures for Cohort ‘08 at Wave 3 (5 Years). Dublin. Available at: https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/20190404-Cohort-08-at-5years-design-instrumentation-and-procedures.pdf.

- Zinovyeva, N., Felgueroso, F. and Vazquez, P. (2014) ‘Immigration and student achievement in Spain: evidence from PISA', SERIES 5(1): 25–60. doi:10.1007/s13209-013-0101-7.