ABSTRACT

Despite the potential importance of kin to divorced parents in particular, prior research rarely studied how kinship patterns vary between married and divorced parents, nor within-group variations depending upon postdivorce residence arrangements and repartnering. We estimated mixed-effects logistic regression models using data from samples of Dutch married (N = 1,336) and divorced parents (N = 3,464) to predict the extent to which parents considered various blood relatives and (former) in-laws kin (i.e. parents, siblings, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews, and cousins) and investigated differences within the divorced group per residence arrangements and repartnering. We found that married and divorced parents barely differed in the extent to which they considered blood relatives kin, but differences were large for (former) in-laws, and particularly great when parents did not reside with their biological child. Repartnered divorced parents were less likely to consider their former in-laws kin than single divorced parents but considered their new in-laws kin to high extents. For both blood relatives and (former) in-laws, parents were most often, and cousins least often considered kin. These results indicate that kinship patterns only differ for in-laws between married and divorced parents. Resident children may lead parents to consider former in-laws kin, whereas repartnering leads to exclusion of former in-laws.

Kin are important for parents and children: they form a latent network that can provide crucial emotional and practical support in times of need (Chiteji and Hamilton Citation2005; Riley Citation1983). Particularly divorced parents and their children may need the support of their kin to compensate for the partial loss of the socioeconomic resources of the partner (Gerstel Citation1988). Divorced parents’ ties with their kin may, however, be disrupted compared to married parents’ (Curran et al. Citation2003; Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou Citation2005), which can hamper access to kin-based resources, leading to potentially negative consequences for these parents and their children, such as lowered well-being (Curran et al. Citation2003; Hughes Citation1988; Milardo Citation1987). In this study, we investigate how married or cohabiting (in short: married) and divorced or separated (in short: divorced) parents differ in whom they consider kin, focusing on blood relatives and in-laws.

Studying such subjective perceptions of kinship is vital for several reasons. From an individual perspective, kin matter for people’s construction of a sense of self and constitute a safety net for times of need (Riley Citation1983). Understanding whom parents consider kin and the role that divorce plays therein could uncover groups of parents that are especially at risk of losing a substantial part of their support system following divorce or who might suffer psychologically from (potentially radical) changes to their family or kinship boundaries (Coleman et al. Citation2022). From a sociological perspective, little is known about what exactly people understand to be their family or kin in this era of unprecedented family diversity and how and why divorce and cultural norms attached to (postdivorce) family relationships influence such perceptions of kinship (Jensen Citation2021; Lück and Castrén Citation2018; Lück and Ruckdeschel Citation2018). Understanding these issues in greater detail is vital for understanding how cultural norms and family structure transitions shape individual kinship perceptions, what patterns of intergenerational solidarity among married and divorced parents nowadays look like (Bengtson Citation2001), and for informing how researchers conceptualize one of the key units of analysis of sociological research (Lück and Castrén Citation2018; Schwartz Citation1993).

There are, to our knowledge, only a few studies that directly compare married and divorced parents’ conceptualizations of kinship (e.g. Johnson Citation1989; Milardo Citation1987; Rands Citation1988; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Widmer Citation2006). Most studies comparing married and divorced parents consider (differences in) kin behavior between both groups, for example in terms of contact frequency with various relatives (e.g. Ambert Citation1988; Anspach Citation1976; Brown Citation1982; Gerstel Citation1988; Gürmen et al. Citation2021; Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou Citation2005), but such differences may not equate to differences in people’s perceptions about who is kin. Kin relationships are often latent, meaning that someone can be considered kin without much contact with them (Riley Citation1983). Per this argument, it might not be so much (close) contact with kin that is important for getting support in time of need, but rather that one has people one considers kin in the first place. The few studies making such explicit comparisons between married and divorced parents’ conceptualizations of kinship mostly date from the previous century, are often situated in the American context, rely on non-probabilistic convenience samples, and usually focus only on blood relatives (e.g. Johnson Citation1989; Milardo Citation1987; Rands Citation1988; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Widmer Citation2006). Findings from these studies might thus not translate to present times or the Western European context and paint an incomplete picture of kin relationships.

In this study, we contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we consider differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider blood relatives and in-laws kin. Considering in-laws is crucial as bonds with in-laws are more negotiable than those with blood relatives (i.e. ‘blood is thicker than water’; Neyer and Lang Citation2003). It might be, thus, especially the extent to which in-laws are considered kin that differs between married and divorced people (e.g. Ambert Citation1988; Duran-Aydintug Citation1993; Serovich et al. Citation1992). Such a ‘loss’ of in-law bonds can be problematic, as it is assumed that in-laws provide considerable support to married couples and their children (Goetting Citation1990).

Second, we contribute by considering the present-day diversity among divorced parents. In addition to divorce being less stigmatized and family values having become more liberal (Kalmijn and Saraceno Citation2008), there is greater diversity among postdivorce families than in previous decades. Divorced parents may be repartnered (see e.g. Castrén and Widmer Citation2015) and their children can follow various residence arrangements after divorce, with a marked prevalence of shared residence arrangements. Such diversity has rarely been considered vis-à-vis who is considered kin but doing so is important from a practical and theoretical perspective. From a practical perspective, investigating postdivorce heterogeneity could identify parents who consider only a few relatives kin, which can make these parents and their children especially vulnerable due to potentially limited access to kin-based resources. From a theoretical perspective, investigating heterogeneities allows for testing theoretical concepts that are used to explain why people consider their relatives kin in greater detail than was possible before, such as the idea that parents might ‘swap families’ after repartnering (i.e. parents might substitute the new in-laws for the former in-laws) or that having children residing in one’s household facilitates relationships with relatives in general and in-laws, in particular, (e.g. Ambert Citation1988).

Therefore, this study specifically considers how married and divorced parents differ in the extent to which they consider their blood relatives and (former) in-laws kin. Second, we consider postdivorce heterogeneity by distinguishing between different postdivorce residence arrangements (i.e. residential parents, non-residential parents, and shared residential parents (i.e. joint physical custody)) and repartnering. For divorced parents who repartnered, we also investigate the extent to which they consider their ‘new’ in-laws kin. Third, we investigate how married and divorced parents differ concerning which specific relatives they consider kin: parents (in-law), siblings (in-law), aunts and uncles (in-law), nieces and nephews (in-law), and cousins (in-law). Investigating differences between married and divorced parents in such detail yields insights into which specific parts of the latent kin network of divorced parents differ from that of married parents.

Our study is situated in the Netherlands: an in the European context more individualistic than familialistic society (Kalmijn and Saraceno Citation2008). As Dutch people are – on average – less ‘family-minded’ (particularly when it comes to the inclusion of more distant family members in their kinship networks) and may take a more individualistic approach to whom they consider kin, differences between married and divorced parents in whom they consider kin might be especially pronounced, with potentially negative ramifications for Dutch parents and their children. We analyzed data from the second wave of the New Families in the Netherlands survey (NFN; 2015/16; Poortman and van Gaalen Citation2019). NFN comprises two subsamples: one among married or cohabiting parents (N = 1,336) and another among parents who dissolved their marital or cohabitation relationship in 2009/2010 (N = 3,464). Both samples provided information about kin perceptions of various blood relatives and (former) in-laws, offering the unique opportunity to examine kinship in detail.

Background

We base our theoretical arguments on two factors that influence the extent to which relatives are considered kin: kinship norms (i.e. societal norms prescribing who should be considered kin) and behavioral aspects of kin relationships, such as contact frequency and exchanged help (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Schneider Citation1980; Thomson Citation2017). Norms are stronger and more clearly defined for blood relatives than in-laws, particularly during marriage (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Schneider Citation1980), which may lead to differences in the extent to which they are considered kin by married and divorced people. The same applies to behavioral aspects of kin relationships: divorced parents typically have less contact with their (former) in-laws than married parents (Anspach Citation1976), which may lead to differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider them kin.

Differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider blood relatives and in-laws kin

Blood relatives are a key part of the social network of married and divorced parents (Neyer and Lang Citation2003). Whether married and divorced parents differ regarding the extent to which they consider their blood relatives kin is uncertain. Kinship norms about whether blood relatives are kin might be unaffected by divorce (Neyer and Lang Citation2003). Ties to certain blood relatives – chiefly parents and siblings – may be more intense for divorced people (Anspach Citation1976; Gürmen et al. Citation2021; Johnson Citation1988), which might be a consequence of divorcees requiring emotional or practical support. High(er) postdivorce contact or closeness, however, probably does not substantially affect whether parents consider their blood relatives kin given that it is the norm to consider them kin irrespective of actual contact (Schneider Citation1980). Divorce might cause friction among blood relatives (Agllias Citation2016; Carr et al. Citation2015), though it is, based on such previous research, not clear if this also influences the extent to which blood relatives are considered kin. We, thus, do not hypothesize about differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider blood relatives kin.

As for in-laws, spouses are expected to consider them as much their kin as their blood relatives, which has been referred to as the ‘principle of equity’ (Jallinoja Citation2011; Johnson Citation1989; Lopata Citation1999; Moore Citation1990). After divorce, the principle of equity no longer applies. Relationships with the then ‘former’ or ‘ex-’ in-laws become ambiguous and, overall, ‘voluntary’ (Duran-Aydintug Citation1993; Finch and Mason Citation1990; Santos and Levitt Citation2007): in-law ties are ‘thinner’ than blood ties and thus more prone to disruption (Neyer and Lang Citation2003). Only a few parents seem to consider their former in-laws kin (Finch and Mason Citation1990). One possible reason is that, especially in the case of conflictual divorces, parents might feel hurt by their ex-partner and proceed to also cut ties with the former in-laws (Ambert Citation1988; Duran-Aydintug Citation1993). Additionally, parents’ former in-laws might feel forced to ‘side’ with the ex-partner (Castrén Citation2008), and may cut ties with the parent. Ultimately, both divorced parents and their former in-laws may minimize contact with each other, which could lead to estrangement and, ultimately, them no longer considering one another kin. We, thus, hypothesize that:

H1: Married parents are more likely to consider their in-laws kin than divorced parents are to consider their former in-laws kin.

Postdivorce heterogeneity: residence arrangements

Children facilitate contact between parents and their relatives: much contact between parents and their relatives centers around children, such as birthdays or Christmas celebrations (Baxter and Braithwaite Citation2006). As postdivorce residence arrangements determine where the child lives after a divorce it is plausible that the extent to which divorced parents consider their relatives kin may differ by residence arrangement. In the Netherlands, the most common residence arrangements include mother residence (about two-thirds), shared residence (i.e. joint physical custody; about one quarter), and sole father residence (Poortman and van Gaalen Citation2017). So, any divorced parent might either be residential, shared residential, or nonresidential.

Residential parents might be the ones who are primarily responsible for hosting such child-related family events, which necessitates them maintaining contact with their blood relatives. Though (shared) residential parents may have more contact with blood relatives than nonresidential parents, it is – as elaborated – questionable whether differences in contact frequency translate to different perceptions about whether they are kin.

Regarding in-laws, however, ‘having the child’ is often the most important reason to maintain contact with them (Ambert Citation1988). Parents’ former in-laws are still their children’s relatives. These in-laws are often involved in the child’s life: they may be present at family events such as the child’s birthday and children may visit them regularly. If parents are residential, they might, thus, be intermittently in touch with their former in-laws to plan such activities. This is presumably less so in the case of shared residence, an arrangement where both former partners divide childcare tasks more equitably and where the child resides part-time in both parental households. In the case of shared residence, both parents might host family events separately, which gives them less reason to maintain contact with their former in-laws. Non-residential parents might have even less reason to maintain contact with their former in-laws, which, as explained, can negatively affect the extent to which they consider them kin. We hypothesize that:

H2: Sole residential parents are most likely to consider their former in-laws kin, followed by shared-residential and, lastly, nonresidential parents.

Postdivorce heterogeneity: repartnering and new in-laws

Postdivorce repartnering might affect the extent to which parents consider their blood relatives and former in-laws kin (Duran-Aydintug Citation1993). As outlined above, blood relatives might be important sources of emotional and practical support for divorced parents. This need for support might be attenuated following repartnering, as parents can get support from their new partners instead, which might weaken bonds with their blood relatives. Additionally, conflict could arise between parents and their blood relatives if their blood relatives disapprove of the new partner, but it is not clear if this would reduce the extent to which parents consider their blood relatives kin.

Upon repartnering, parents gain ‘new’ in-laws, which they are expected to consider kin (Johnson Citation1989). Concurrently, relationships with the former in-laws may become even more complex and may deteriorate following repartnering. For once, repartnered parents may minimize involvement with their former in-laws and instead focus on being involved with their new in-laws to signal to their new partner and new in-laws that they are their family now (Gerstel and Sarkisian Citation2006; Prentice Citation2008). Additionally, the former in-laws might also distance themselves from the divorced parent, which may further strengthen parents’ not considering them kin. Overall, we hypothesize that:

H3a: Repartnered divorced parents are less likely to consider their former in-laws kin than are single divorced parents.

H3b: Repartnered divorced parents are more likely to consider their new in-laws kin than their former in-laws.

Differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider blood relatives and in-laws of varying genealogical distance kin

Kinship structures in Western societies are hierarchical (Firth et al. Citation1970; Lee et al. Citation2003; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990, 172–185; Schneider Citation1980). This implies that whom parents consider kin may differ greatly among blood relatives and in-laws (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Schneider Citation1980). Kin relationships are commonly classified based on genealogical distance, meaning the number of ‘steps’ one (or, in the case of in-laws, the partner) is removed from the relative in question (Kalmijn Citation2010; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Thomson Citation2017). From a perspective of evolutionary biology, the ‘steps’ indicate the proportion of shared genes with a relative (Dunbar Citation2008). The genealogical distance to one’s parents is one – due to the direct biological link with one’s parents – that to siblings is two (i.e. distance one from self to parent + distance one from parent to sibling), that to aunts/uncles and nieces/nephews three, and, lastly, that to cousins is four (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990).

Kinship norms are strongest for relatives with the shortest genealogical distances (Kalmijn Citation2010; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990; Thomson Citation2017). For example, people give the most help to and expect the most help from their parents, children, and siblings (Höllinger and Haller Citation1990; Kivett Citation1985; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990), feel closest to them and have the most contact with them (e.g. Caplow Citation1982; Leigh Citation1982; Neyer and Lang Citation2003). Collectively, these factors can influence whether someone is considered kin (Thomson Citation2017). We thus hypothesize that:

H4a: The greater the genealogical distance, the less likely that married and divorced parents consider a blood relative or in-law kin.

As we previously outlined, it is uncertain whether married and divorced parents differ in the extent to which they consider blood relatives kin. Whether potential differences between married and divorced parents would be especially strong for certain relatives is equally unclear. Due to stronger and more clearly defined kinship norms, parents might be more loyal to closely related blood relatives even in the presence of divorce-related conflict. Ties to distant blood relatives might be relatively more affected, given that they were likely less strong to begin with. As these arguments are rather speculative, we refrain from giving a hypothesis about whether differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider their blood relatives kin differ by genealogical distance.

In contrast, differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider their in-laws kin might be especially strong for distant in-laws. Parents may facilitate their children’s relationships with their former in-laws, but this is likely particularly (and perhaps exclusively) so for the child’s closest relatives (e.g. the child’s grandparents). Parents might have little to no contact with distant former in-laws, which makes these relatives particularly likely to no longer be considered kin. We hypothesize that:

H4b: The difference in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider their (former) in-laws kin increases with genealogical distance.

Note that, in this step, we do not consider differences within the group of divorced parents according to repartnering and residence arrangements to not distract from the main topic of this study and due to the complexity of the resulting analysis.

Method

Data & sample

We used the survey New Families in the Netherlands (NFN; Poortman and van Gaalen Citation2019). Because questions about kinship were not asked in Wave 1 (2012/13), we only used Wave 2 (2015/2016).Footnote1 For Wave 1 Statistics Netherlands, based on population registers, drew two random samples: one among married or cohabiting parents (in the following: married sample) and a second one among parents who divorced or separated from a cohabiting partner in 2009/2010 (in the following: divorced sample) (Poortman et al. Citation2014). For both samples, both (former) partners were approached via mail and invited to complete a web version of the survey. The final reminder included a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The response rate of the married sample for Wave 1 was 45% on the individual level and 56% on the household level, totaling 2,173 responses. Note that for 62% of households both partners responded. For the divorced sample, the response rate was 39% on the individual level and 58% on the former couple level, totaling 4,481 individual responses. For 30% of households, both former partners responded. Despite the mainly online mode and potentially difficult-to-reach target group, these response rates are comparable to similar surveys in the Netherlands, where survey participation rates are low and declining (de Leeuw et al. Citation2018).

For Wave 2, all participants of Wave 1 from both samples were invited to complete a follow-up survey in 2015/2016 (Poortman et al. Citation2018). Of those who permitted to be contacted again and were eligible to be approached, 61% did so, yielding 1,336 responses (response rate on the level of the household 67%). For the divorced sample, 63% of participants who permitted to be contacted again and who were eligible responded, yielding 2,544 responses (response rate on the level of the former couples 69%). An additional random sample among divorced parents (drawn identically as for Wave 1) was also approached to participate in the second wave to compensate for panel attrition. The response rate for this ‘refreshment sample’ was 32% on the individual and 52% on the former couple level, yielding 920 responses. Combined, Wave 2 contains 1,336 responses from married/cohabiting parents and 3,464 responses from formerly married/cohabiting parents in the Netherlands. For 49% of households of the married sample and 17% of households of the divorced sample, both (former) partners responded.

Compared to the respective populations of interest, the samples are selective on several criteria. In the married sample, like in Wave 1, men, non-native Dutch, and those with relatively low incomes are underrepresented. Furthermore, cohabiting people and those with young children were oversampled and are, thus, somewhat overrepresented. The divorced sample is relatively more select than the married sample. Most notably, men, non-native Dutch, respondents with low incomes and welfare recipients, formerly cohabiting partners, and younger people are underrepresented. Note the selective panel attrition in both samples. In the divorced sample, women, older respondents, those who reported high life satisfaction, and those with high socioeconomic status (highly educated and with paid work) were more likely to respond again. In the married sample, higher educated, older, and female respondents were more likely to participate again.

We excluded respondents who had answered ‘not applicable’ on all dependent variables (N = 18; 0.38%). We excluded respondents in the married sample who were not first married (N = 140; 2.92%), respondents in the divorced sample who divorced earlier (i.e. for whom this was not the first divorce) (N = 418; 8.71%), divorced respondents who specified the child’s main residence as ‘other’ (N = 249; 5.19%), and respondents with missing values on the covariates (N = 88, 1.8%). In total, we analyzed data from 3,887 respondents from 3,175 (former) households.

Measures of dependent variables

All respondents were presented a list of five relatives: ‘your parent(s)’, ‘your brothers/sisters’, ‘your nephews/nieces’, ‘your uncles/aunts’, and ‘your cousins’. Respondents in the married sample were, furthermore, asked about their current partners’ parents, brothers/sisters, nieces/nephews, aunts/uncles, and cousins (i.e. their in-laws), and respondents in the divorced sample were presented a comparable list of their ex-partners’ parents, brothers/sisters, etc. (i.e. their former in-laws). Repartnered divorced respondents were, additionally, presented a comparable list of their respective current partner’s relatives (i.e. their current partner’s parents, siblings, etc.).

For each potential relative, respondents were asked: ‘When you think of “your family” (in Dutch: “gezin”) and “your relatives” (in Dutch: “familie”), do you consider [relative] to be part of your immediate family, your relatives (outside of your immediate family) or neither?’. Answer options were: 1 Family, 2 Relatives, 3 Neither, or Not applicable (e.g. deceased). Note that the option Family was only rarely chosen (in total N = 913 times). The answers are recorded in separate variables. We dichotomized the answer (0 = Neither, 1 = Family/Relatives, i.e., kin) and assigned respondents who answered Not applicable as missing on the respective variable. By restructuring the data from wide to long, these up to fifteen variables per respondent were collated into a single dependent variable representing whether someone is considered kin. This yielded two new variables (‘blood relative’ and ‘type of relative’). Blood relative is a dummy variable classifying whether an observation concerns a blood relative (0) or in-law (1). Type of relative is a categorical variable classifying whether an observation concerns a parent (0), sibling (1), aunt or uncle (2), niece or nephew (3), or cousin (4). These two variables allowed us to select observations about either blood relatives or in-laws or different types of relatives. As these variables are only used to select observations and not used as predictors, they are not discussed in the following.

Measures of independent variables

Divorced. This dichotomous variable indicates whether the respondent belongs to the married (coded as 0) or divorced sample (1).

Repartnered. This dichotomous variable indicates whether divorced respondents have a new cohabiting or married partner (yes = 1).

Type of in-law. This variable, used in the analyses of parents considering their in-laws as their kin (see Analytical Strategy), indicates whether an observation refers to a single divorced parent reporting on his/her former in-laws (0), a repartnered divorced parent reporting on his/her former in-laws (1), or a repartnered divorced parent reporting on his/her new in-laws (2). Note that this implies that descriptive statistics such as means for this variable have no substantive meaning.

Residence arrangement. Divorced respondents were asked where the focal child (see Data & Sample) resided most of the time: ‘with me’, ‘with my ex-partner’, or ‘with both (approximately) equal’. We coded these responses into dichotomous variables measuring whether the respondent was a nonresidental parent (1) or a shared residental parent (2), with residental parent as the reference group (0).

Measures of control variables

We control for basic social-demographic characteristics (e.g. age and gender). In addition, we control for whether the current union (for the married sample) or the previous union (for the divorced sample) was cohabitation or marriage. Note that because the focus of this study is on the differences according to divorce, residence, and repartnering, we do not theorize about differences within the groups of married and divorced parents based on whether their (previous) relationship was cohabitation or marriage. Such distinctions would be based on different theoretical reasoning and are beyond the scope of this study.

Respondent’s Gender. We control for respondent's gender (0 = man, 1 = woman) as women typically are more family-minded than men, and gender relates to differences vis-à-vis, amongst others, becoming the resident parent and repartnering choices. Age respondent and age child, respectively, indicate the age of the respondents and the focal child measured in years and were included because older respondents and those with younger children might be relatively less likely to, e.g. divorce and might more frequently be in contact with their relatives and might, thus, more likely consider them kin. Education respondent and education (ex-)partner measure, respectively, the respondents’ and their (ex-)partners’ highest obtained level of education (1 = incomplete elementary school to 10 = post-graduate). Education levels are both related to central independent variables, such as divorce and choosing residence arrangements, as well as to the propensity to rely on kin for support and thus potentially also for considering relatives kin. We treated these variables as continuous, as using separate dummy variables yielded similar results in the analyses. Note that the ages of the respondent and the child, and the education level of the respondent and the (ex)partner, are moderately correlated with each other (education levels: r = .46, p < .001; ages: r = 0.68, p < .001), but that the VIFs for these variables in no model exceeded the value of 2. Married is a dummy variable referring to whether respondents’ (previous) union was 0 ‘cohabitation’ or 1 ‘marriage/registered partnership’. We control for union status as marriage carries stronger family norms than cohabitation, meaning that union status can influence the propensity to divorce or repartner and to consider relatives kin (married parents might be more likely to consider their relatives kin than those who cohabit). Religious indicates whether respondents identify as belonging to a religious denomination (1). We control for religiosity as religiosity both negatively affects, e.g. the propensity to divorce and positively affects the propensity to consider relatives kin, due to religious family norms. Employed indicates whether the respondent is currently in paid employment (1). We account for employment as it relates to divorce and repartnering and employed respondents might rely less on kin support than unemployed respondents, wherefore they might be less likely to consider their relatives kin. Note that for some relatively time-invariant control variables we used information from wave 1 as these questions were no longer asked in Wave 2 (i.e. parent’s education, former union type, and religion). gives an overview of the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analyses.

Table 1. Summary of descriptive statistics of independent and control variables used in the analyses.

Analytical strategy

We grand-mean centered the continuous variables and estimated several multilevel logistic regression models. We used multilevel models as some observations are from both (former) partners, which implies that these observations might be dependent. Of the various techniques for controlling for such dependencies, multilevel models are generally preferred for data that is nested by design (as is the case with the NFN data) (Aarts et al. Citation2014).

Models 1A and 1B estimate how married and divorced parents differ in how far they consider their blood relatives (1A) and (former) in-laws kin (1B). Model 1A includes all blood relatives (i.e. parents, siblings, nieces/nephews, aunts/uncles, and cousins), whereas Model 1B includes all (former) in-laws (i.e. (former) parents-in-law etc.). Models 1C-1F consider divorced respondents only and estimate how different residence arrangements affect the extent to which blood relatives (Model 1C) and former in-laws (Model 1D) are considered kin, and how single and repartnered parents differ in the extent to which they consider blood relatives (Model 1E) and former and new in-laws kin (Model 1F). All these models, thus, include multiple observations per respondent (i.e. multiple blood relatives or (former) in-laws). Models 2A-2E show how married and divorced people differ in the extent to which blood relatives they consider kin (model 2A: parents, 2B: siblings, 2C: aunts and uncles; 2D: nieces and nephews; 2E: cousins). Models 3A-3E, similarly show the extent to which the various (former) in-laws are considered kin (3A: parents-in-law; 3B: siblings-in-law; 3C: aunts/uncles in-law; 3D: nieces/nephews in-law; 3E: cousins-in-law). As some observations are from both (former) partners (see above), all models include random intercept terms on the (former) household level. Therefore, the variance of all models is partitioned between the level of the individual respondents and the (former) household levels, allowing for unbiased estimates of the person-level parameters. Models 1A-F, which include multiple observations per respondent, additionally include a random intercept term on the level of the individual.

Instead of interpreting the regression coefficients, we calculated and plotted predicted probabilities and their respective significance levels (see , full overview in Appendix Tables A4–A6) as we are interested in the differences between the probabilities of married and divorced parents considering relatives kin, rather than the (more obscure) raw effects themselves or the effects of covariates (see Appendix Tables A1–A3 for the full mixed effects models). Predicted probabilities are average marginal effects of categorical variables. Besides being intuitive to interpret, predicted probabilities can be compared across models as they occur in the natural metric of the dependent variable and are unaffected by the identification problem inherent in logistic regression (Mize et al. Citation2019). We calculated the predicted probabilities (i.e. average marginal effects) and computed standard errors and p-values (Mize et al. Citation2019; Williams Citation2012), meaning that one can test for statistically significant differences between predicted probabilities from the same or different models, with these differences being ‘average discrete changes’ (ADC, see Mize et al. Citation2019, 182–184).

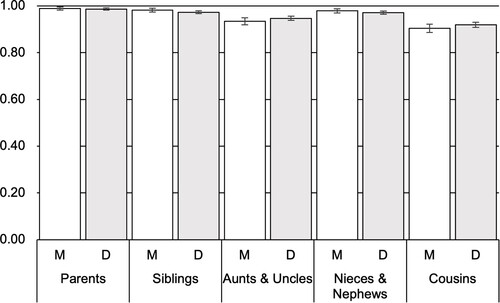

Figure 1. Considering blood relatives kin.

Note: Whiskers represent 95% Confidence Intervals for the predicted probabilities

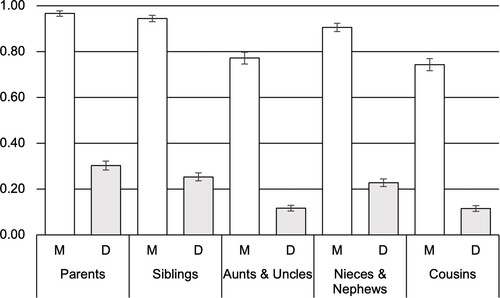

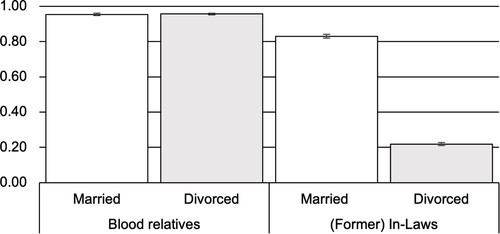

Figure 2. Considering blood relatives and former in-laws kin, by residence arrangement.

Note: Whiskers represent 95% Confidence Intervals for the predicted probabilities

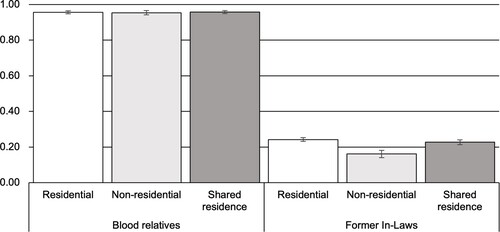

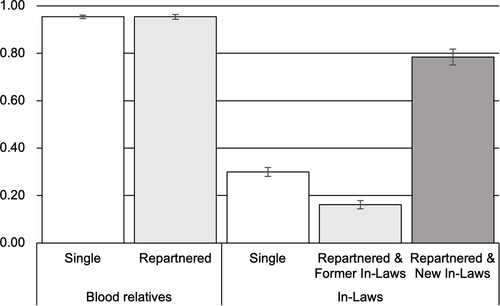

Figure 3. Considering blood relatives and former in-laws kin, by repartnering.

Note: Whiskers represent 95% Confidence Intervals for the predicted probabilities

Results

shows the predicted probabilities of married and divorced parents considering their blood relatives and in-laws kin. This figure is based on Models 1A and 1B (see ; the corresponding predicted probabilities are summarized in Appendix Table A4). The figure shows that there appears to be no difference between married and divorced parents in the extent to which they consider their blood relatives kin – the respective predicted probabilities were equally high (0.96) and did not statistically significantly differ from one another (ADC: 0.00, p > .05) . , furthermore, shows that the predicted probabilities of (former) in-laws being considered kin were lower than those for blood relatives. More importantly, married parents had a statistically significantly higher predicted probability (0.83) than divorced parents (0.22) of considering their (former) in-laws kin (ADC: −0.61, p < .001) which is in line with our hypothesis (see H1). While the difference between these predicted probabilities were large, the results indicate that a substantial minority of divorced parents still considered their former in-laws kin.

shows differences in the extent to which divorced parents consider their blood relatives and former in-laws kin, per postdivorce residence arrangement. This figure is based on Models 1C and 1D (see Appendix Table A1; see Appendix Table A4 for the corresponding predicted probabilities). As the figure shows, there was no difference between the three residence arrangements vis-à-vis considering blood relatives kin (ADCs all 0.01 and p > 0.5). In comparison, there were statistically significant differences between the three residence arrangements vis-à-vis considering former in-laws kin. Contrary to our hypothesis H2, residential (not shared-residential) parents were most likely to consider their former in-laws kin (0.24), followed by shared residential (0.23), and, lastly, non-residential parents (0.16), with the differences between non-residential and residential/shared residence being statistically significant (see Appendix Table A4).

shows differences in the extent to which divorced parents consider their blood relatives and former and new in-laws kin, by repartnering. These predicted probabilities shown in this figure were calculated from Models 1E and 1F (see Appendix Table A1; see Appendix Table A4 for the predicted probabilities). The left part of shows that single and repartnered divorced parents were about equally likely to consider their blood relatives kin (predicted probabilities 0.96, and 0.95, respectively, ADC: 0.01, p > .05). As the right part of shows, the differences for in-laws were bigger. First, in line with hypothesis 3b, repartnered parents were less likely to consider their former in-laws kin than single divorced parents (predicted probabilities 0.16 and 0.30, respectively, ADC: 0.14, p < .001). Furthermore, repartnered parents were more likely to consider their new in-laws than their former in-laws kin (predicted probabilities 0.78 and 0.16, respectively, ADC: −0.62, p < .001), which aligns with our expectations (see H3c). Additionally, although not hypothesized, there was a difference between the extents to which married parents consider their in-laws and repartnered parents considered their new in-laws kin (predicted probabilities 0.83 and 0.78, ADC: 0.05, p < .001, analyses not shown).

shows the predicted probabilities of married and divorced parents considering their various blood relatives their kin (see Appendix Table A2 for the full regression models and Appendix Table A5 for the predicted probabilities and differences between them). As the figure shows, married and divorced parents considered their parents most often kin, followed by siblings, nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, and, lastly, cousins. All blood relatives were considered kin to high extents (ranging from 0.99 for parents to 0.91 for cousins). The differences in the extent to which blood relatives are considered kin all differed statistically significantly from one another, except for the difference between siblings and nieces/nephews (see Appendix Table A5). Siblings and nieces/nephews were considered kin to about equally high extents. Nevertheless, these findings generally align with our hypothesis that genealogically distant relatives are less likely to be considered kin than closer relatives (see H4a). However, per our hypothesis, there should only be differences between degrees of relatedness, but not between relatives of the same degree of relatedness. Our results, though, show that nieces/nephews were more likely to be considered kin than aunts/uncles. The differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents considered their blood relatives kin were not statistically significant, and the differences in the extent to which married and divorced parents consider their blood relatives kin did not substantially vary with genealogical distance (see Appendix Table A5).

shows the predicted probabilities of married and divorced parents considering their (former) in-laws kin (see Appendix Table A3 for the regression models and Appendix Table A6 for the predicted probabilities and the differences between them). As the figure shows, parents and siblings-in-law (of married parents) were considered kin to relatively high extents (predicted probability 0.97 and 0.95 respectively), but this was less so for aunts and uncles (0.77), nieces and nephews (0.91), and cousins (0.74). The predicted probabilities for former in-laws followed the same order, though they were much lower in absolute terms. For example, the predicted probability of former parents-in-law being considered kin was 0.30, while those of former aunts and uncles-in-law and former cousins-in-law were only 0.12. As Appendix Table A6 shows, these decreases along genealogical distance were statistically significant for married and divorced parents, which is in line with our hypothesis 4a. Furthermore, all differences between married and divorced parents were statistically significant and generally of the same magnitude: the difference was largest for siblings (−0.69), followed by nieces and nephews (−0.68), parents and aunts/uncles (both −0.66), and, lastly, cousins (−0.62). We did not observe a clear pattern regarding whether these differences varied with genealogical distance, let alone increase (as we hypothesized). Only some of the differences were statistically significant (see Appendix Table A6). This leads us to conclude that our hypothesis regarding differences between married and divorced parents along genealogical distance (see H4c) is, overall, not supported.

Additional analyses

As women often have stronger ties to their relatives, we fully interacted all models with parents’ gender to test for gender differences. We only found (small) gender differences in the extent to which divorced parents considered their former in-laws kin. For reasons of parsimony, we do not show the full regression models and instead only present those predicted probabilities where we observed gender differences (see Appendix Table A7). Women were more likely to consider their former in-laws kin than men, with the gender differences being largest for former nieces/nephews in-law (women had a 0.09 higher probability of considering them kin than men) and smallest for aunts/uncles and cousins (difference in probabilities 0.04). This finding is in line with the results of related studies reporting that women maintained more contact with their former in-laws than men (e.g. Ambert Citation1988; Serovich et al. Citation1992).

Discussion and conclusion

Married and divorced parents differ in whom they consider kin. With this study, we extended the literature on kinship in several ways, namely by making direct comparisons between whom married and divorced parents consider kin, by focussing on both blood relatives and (former) in-laws, by focusing on the heterogeneity among divorced parents regarding residence arrangements and repartnering, and by examining different types of blood relatives and (former) in-laws (i.e. parents, siblings, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews, and cousins). To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating kinship in the context of divorce so comprehensively. The results of our study lead to several conclusions.

First, married and divorced parents consider their blood relatives kin to equally high extents. Thus, whereas divorced parents’ kin behavior might be different from that of married parents (Kalmijn and Broese van Groenou Citation2005), our results suggest that this does not translate to different perceptions about blood relatives being kin. Blood relatives form a robust latent kin network also for divorced parents (Riley Citation1983), which can benefit themselves and their children.

Second, we found that whereas almost all married parents considered their in-laws kin, the probability of divorced parents considering former in-laws kin was low (0.22). This aligns with the principle of equity: married parents generally consider their in-laws kin, but this ends with divorce (Jallinoja Citation2011). So, it is not just contact with the in-laws that is often lower for divorced parents (Duran-Aydintug Citation1993): divorced parents also have different perceptions about whether they are kin in the first place (Castrén and Widmer Citation2015). This might imply that parents could become reluctant to facilitate contact between their child and former in-laws, which may entail a loss of latent resources for the child if the ex-partner does not sufficiently maintain contact with his/her relatives (Serovich et al. Citation1992).

Third, we found considerable differences among divorced parents in the extent to which former in-laws are considered kin. Specifically, non-resident parents were less likely to consider their former in-laws kin than resident or shared resident parents. This aligns with contentions from previous research that ties to former in-laws are oftentimes maintained for the sake of the children (Ambert Citation1988): in the absence of a resident child connecting the relatives, ties to former in-laws are depreciated more readily. Moreover, repartnered parents were less likely to consider their former in-laws kin than single parents, but they did consider their new in-laws kin to high extents (0.78). This suggests substitution between former and new in-laws: the former in-laws come to be no longer considered kin following repartnering (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990), and the new in-laws may – to an extent – take their place. Repartnered parents, though, were less likely to consider their new in-laws kin than married parents were to consider their in-laws kin. These findings indicate that non-residential and single parents might have the smallest latent kin network, which implies that they might be in an especially vulnerable position after divorce. On the flip side, residential parents – who have the most childcare responsibilities – also have the largest latent kin network, which means that they can also count on the most support from their kin.

Fourth, we found that the principle of genealogical distance (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990) structures the extent to which blood relatives and (former) in-laws are considered kin, though different from what previous studies described. For both blood relatives and in-laws, parents were most likely to be considered kin, followed by siblings, nieces/nephews, aunts/uncles, and, lastly, cousins. This is somewhat in contrast with previous prior research, which argued that nieces and nephews are considered kin to the same extent as aunts and uncles, as they are of the same degree of relatedness (Kalmijn Citation2010; Rossi and Rossi Citation1990). A possible explanation is that our sample concerned only parents, and their children might have contact with the parents’ nieces and nephews (in-law) (i.e. the child’s cousins of likely equal age), which might be facilitated by the respondent and, thus, lead to parents to consider them kin more readily than their aunts and uncles. We generally found no or only negligible differences in the extent to which the differences between married and divorced parents differed for different blood relatives and in-laws.

Naturally, our study comes with limitations. First, our results only reflect parents’ views, which might diverge from those of their children. Children might consider the ex-partner’s (i.e. their other biological parents’) relatives kin to much higher extents than their parents. Second, we used cross-sectional data. A longitudinal design would be necessary for concrete causal inferences about the effect of divorce on who is considered kin. For example, parents who eventually divorce might have been less ‘family-minded’ to begin with (i.e. selection effects). We suggest future researchers make use of longitudinal data but, to our knowledge, such data, especially containing information on repartnering and residence arrangements, is unavailable. Third, background information on the various relatives is not available in NFN, meaning that we could not control for factors such as the different relatives’ age, gender, physical distance from the respondent, or relationship quality, which may influence whether they are considered kin. Some of our theoretical arguments were based on interpersonal factors like contact or conflict, but these are impossible to explicitly test using this dataset (or any dataset known to us). Fourth, the sample used is selective according to several criteria, such as country of origin and socioeconomic status, with the divorced sample being more selective than the married sample. Though the direction of potential bias arising from this selectivity is difficult to ascertain, inferences about the population should be made with care. Lastly, all divorced respondents were divorced in 2009/2010, meaning that the results pertaining to divorced parents presented in this paper only reflect kin perceptions about five to six years after divorce.

Overall, our findings indicate that divorce appears relevant for how parents make sense of kinship and might cause parents to substantially reframe relationships with people they once considered kin. In general, considerations of who is kin appear to be substantially informed by rather rigid notions of biological relatedness and appear to be rooted in the nuclear family ideology. This can be most clearly seen in divorced parents’ tendency to ‘swap’ former in-laws with new in-laws when they repartner. In other words: blood and legal bonds are still ‘thicker than water’ (Neyer and Lang Citation2003). However, our findings also reveal (limited) flexibility and continuity in who is considered kin after divorce: a substantial share of divorced parents still considered their former in-laws – especially former parents-in-law – kin without having a concrete normative obligation to do so. Clearly, ties to former in-laws are to an extent continued on a voluntary basis after divorce. These findings beg the question in how far societal norms and definitions of kinship based on blood or law are still appropriate in this era of unprecedented family diversity and whether they are perhaps too limiting or inappropriate for divorced families in particular (see e.g. Zartler Citation2014). More embracive kinship conceptualizations based on – for example – shared children instead of blood or marital bonds are common among various non-Western populations and could serve as a useful starting point for informing more appropriate kinship conceptualizations among postdivorce families (e.g. Clark et al. Citation2015; Crosbie-Burnett and Lewis Citation1993; Taylor et al. Citation2022). Efforts could also be made to stimulate more embracive conceptualizations of kinship that rely on individuals’ own accounts of who their kin are instead of relying on scholarly definitions of kinship, for example when designing family surveys (Sanner et al. Citation2020).

REUS-2022-0062-File008.pdf

Download PDF (278.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Utrecht University (FETC20-089).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christian Fang

Christian Fang (he/him) is a PhD candidate at the Department of Sociology of Utrecht University and affiliated with the Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology (ICS). His research involves using large-scale survey data to understand how family is “done” in postdivorce families.

Anne-Rigt Poortman

Anne-Rigt Poortman is professor at the Dept. of Sociology (Chair: Family diversity and life course outcomes). She has specialized in family sociology and social demography. She is particularly interested in divorce and repartnering, postdivorce residence arrangements for children, new relationship types, and legal aspects of partner relationships.

Notes

1 For purposes of scientific research, the New Families in the Netherlands (NFN) data is available at DANS: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-24y-n8s4. The replication package containing the code to replicate the findings presented in this article can be found on OSF: https://osf.io/j3d6e/.

References

- Aarts, E., Verhage, M., Veenvliet, J. V., Dolan, C. V. and van der Sluis, S. (2014) ‘A solution to dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data’, Nature Neuroscience 17(4): 491–96. doi:10.1038/nn.3648.

- Agllias, K. (2016) Family Estrangement: A Matter of Perspective, London: Taylor & Francis.

- Ambert, A.-M. (1988) ‘Relationships with former In-laws after divorce: A research note’, Journal of Marriage and Family 50(3): 679–86. doi:10.2307/352637.

- Anspach, D. F. (1976) ‘Kinship and Divorce’, Journal of Marriage and Family 38(2): 323–30. doi:10.2307/350391.

- Baxter, L. A., & Braithwaite, D. O. (2006). ‘Rituals as communication constituting families’, In L. Turner and R. West (eds.), The Family Communication Sourcebook, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 259–80.

- Bengtson, V. L. (2001) ‘Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds’, Journal of Marriage and Family 63(1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x.

- Brown, E. M. (1982) ‘Divorce and the extended family: A consideration of services’, Journal of Divorce 5(1–2): 159–71. doi:10.1300/J279v05n01_12.

- Caplow, T. (1982) ‘Christmas gifts and kin networks’, American Sociological Review 47(3): 383–92. doi:10.2307/2094994.

- Carr, K., Holman, A., Abetz, J., Kellas, J. K. and Vagnoni, E. (2015) ‘Giving voice to the silence of family estrangement: comparing reasons of estranged parents and adult children in a nonmatched sample’, Journal of Family Communication 15(2): 130–40. doi:10.1080/15267431.2015.1013106.

- Castrén, A. M. (2008) ‘Post-divorce family configurations’, in E. D. Widmer and R. Jallinoja (eds.), Beyond the Nuclear Family: Families in a Configurational Perspective, Bern: Peter Lang, Vol. 9, pp. 233–54.

- Castrén, A. M. and Widmer, E. D. (2015) ‘Insiders and outsiders in stepfamilies: Adults’ and children’s views on family boundaries’, Current Sociology 63(1): 35–56. doi:10.1177/0011392114551650.

- Chiteji, N. and Hamilton, D. (2005) ‘Family matters: Kin networks and asset accumulation’, in M. W. Sherraden (ed.), Inclusion in the American Dream: Assets, Poverty, and Public Policy, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–111.

- Clark, S., Cotton, C. and Marteleto, L. J. (2015) ‘Family ties and young fathers’ engagement in Cape Town’, South Africa. Journal of Marriage and Family 77(2): 575–89. doi:10.1111/jomf.12179.

- Coleman, M., Ganong, L., D’Amore, S., Browning, S., DiNardo, D. and Methikalam, B. (2022) ‘Boundary ambiguity: A focus on stepfamilies, queer families, families with adolescent children, and multigenerational families’, in Treating Contemporary Families: Toward a More Inclusive Clinical Practice, American Psychological Association, pp. 157–86. doi:10.1037/0000280-007

- Crosbie-Burnett, M. and Lewis, E. A. (1993) ‘Use of African-American family structures and functioning to address the challenges of European-American postdivorce families’, Family Relations 42(3): 243. doi:10.2307/585552.

- Curran, S. R., McLanahan, S. and Knab, J. (2003) ‘Does remarriage expand perceptions of kinship support among the elderly?’ Social Science Research 32(2): 171–90. doi:10.1016/S0049-089X(02)00046-7.

- de Leeuw, E., Hox, J. and Luiten, A. (2018) ‘International nonresponse trends across countries and years: An analysis of 36 years of labour force survey data’, Survey Insights: Methods from the Field 11. doi:10.13094/SMIF-2018-00008.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (2008) ‘Kinship in biological perspective’, in W. James, N. J. Allen, H. Callan and R. I. M. Dunbar (eds.), Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, Chichester: Blackwell, pp. 131–50.

- Duran-Aydintug, C. (1993) ‘Relationships with former in-laws: Normative guidelines and actual behavior’, Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 19(3–4): 69–82. doi:10.1300/J087v19n03_05.

- Finch, J. and Mason, J. (1990) ‘Divorce, remarriage and family obligations’, The Sociological Review 38(2): 219–46. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1990.tb00910.x.

- Firth, R., Hubert, J. and Forge, A. (1970) Families and Their Relatives, London: Routledge.

- Gerstel, N. (1988) ‘Divorce and kin ties: The importance of gender’, Journal of Marriage and Family 50(1): 209–19. doi:10.2307/352440.

- Gerstel, N. and Sarkisian, N. (2006) ‘Marriage: The good, the bad, and the greedy’, Contexts 5(4): 16–21. doi:10.1525/ctx.2006.5.4.16.

- Goetting, A. (1990) ‘Patterns of support among in-laws in the United States: A review of research’, Journal of Family Issues 11(1): 67–90. doi:10.1177/019251390011001005.

- Gürmen, M. S., Anderson, S. R. and Brown, E. (2021) ‘Relationship with extended family following divorce: A closer look at contemporary times’, Journal of Family Studies 27(1): 48–62. doi:10.1080/13229400.2018.1498369.

- Höllinger, F. and Haller, M. (1990) ‘Kinship and social networks in modern societies: A cross-cultural comparison among seven nations’, European Sociological Review 6(2): 103–24. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036553.

- Hughes, R. (1988) ‘Divorce and social support: A review’, Journal of Divorce 11(3–4): 123–45. doi:10.1300/J279v11n03_10.

- Jallinoja, R. (2011) ‘Obituaries as family assemblages’, in R. Jallinoja and E. D. Widmer (eds.), Families and Kinship in Contemporary Europe, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 78–91.

- Jensen, T. M. (2021) ‘Theorizing ambiguous gain: Opportunities for family scholarship’, Journal of Family Theory & Review. doi:10.1111/jftr.12401.

- Johnson, C. L. (1988) ‘Postdivorce reorganization of relationships between divorcing children and their parents’, Journal of Marriage and Family 50(1): 221–31. doi:10.2307/352441.

- Johnson, C. L. (1989) ‘In-law relationships in the American kinship system: The impact of divorce and remarriage’, American Ethnologist 16(1): 87–99. doi:10.1525/ae.1989.16.1.02a00060.

- Kalmijn, M. (2010) ‘Verklaringen van intergenerationele solidariteit—Een overzicht van concurrerende theorieën en hun onderzoeksbevindingen’, Mens En Maatschappij 85(1): 70–98. doi:10.5117/MEM2010.1.KALM.

- Kalmijn, M. and Broese van Groenou, M. (2005) ‘Differential effects of divorce on social integration’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 22(4): 455–76. doi:10.1177/0265407505054516.

- Kalmijn, M. and Saraceno, C. (2008) ‘A comparatiev perspective on intergenerational support: Responsiveness to parental needs in individualistic and familialistic countries’, European Societies 10(3): 479–508. doi:10.1080/14616690701744364.

- Kivett, V. R. (1985) ‘Consanguinity and kin level: Their relative importance to the helping network of older Adults’, Journal of Gerontology 40(2): 228–34. doi:10.1093/geronj/40.2.228.

- Lee, E., Spitze, G. and Logan, J. R. (2003) ‘Social support to parents-in-law: The interplay of gender and kin hierarchies’, Journal of Marriage and Family 65(2): 396–403. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00396.x.

- Leigh, G. K. (1982) ‘Kinship interaction over the family life span’, Journal of Marriage and Family 44(1): 197–208. doi:10.2307/351273.

- Lopata, H. Z. (1999) ‘In-laws and the concept of family’, Marriage & Family Review 28(3–4): 161–72. doi:10.1300/J002v28n03_13.

- Lück, D. and Castrén, A.-M. (2018) ‘Personal understandings and cultural conceptions of family in European societies’, European Societies 20(5): 699–714. doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1487989.

- Lück, D. and Ruckdeschel, K. (2018) ‘Clear in its core, blurred in the outer contours: Culturally normative conceptions of the family in Germany’, European Societies 20(5): 715–42. doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1473624.

- Milardo, R. M. (1987) ‘Changes in social networks of women and men following divorce: A review’, Journal of Family Issues 8(1): 78–96. doi:10.1177/019251387008001004.

- Mize, T. D., Doan, L. and Long, J. S. (2019) ‘A general framework for comparing predictions and marginal effects across models’, Sociological Methodology 49(1): 152–89. doi:10.1177/0081175019852763.

- Moore, G. (1990) ‘Structural determinants of men’s and women’s personal networks’, American Sociological Review 55(5): 726–35. doi:10.2307/2095868.

- Neyer, F. J. and Lang, F. R. (2003) ‘Blood is thicker than water: Kinship orientation across adulthood’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84(2): 310–21. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.310.

- Poortman, A.-R., Stienstra, K., & De Bruijn, S. (2018). Codebook of the Survey New Families in the Netherlands (NFN). Second Wave, Utrecht: Utrecht University, p. 195.

- Poortman, A.-R., van der Lippe, T., & Boele-Woelki, K. (2014). Codebook of the Survey New Families in the Netherlands (NFN). First Wave, Utrecht: Utrecht University, p. 166.

- Poortman, A.-R. and van Gaalen, R. (2017) ‘Shared residence after separation: A review and new findings from the Netherlands’, Family Court Review 55(4): 531–44. doi:10.1111/fcre.12302.

- Poortman, A.-R. and van Gaalen, R. (2019) New families in the Netherlands (NFN): Wave 2. DANS.

- Prentice, C. M. (2008) ‘The assimilation of in-laws: The impact of newcomers on the communication routines of families’, Journal of Applied Communication Research 36(1): 74–97.

- Rands, M. (1988) ‘Changes in social networks following marital separation and divorce’, in R. M. Milardo (ed.), Families and Social Networks, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Limited, pp. 127–46.

- Riley, M. W. (1983) ‘The family in an aging society: A matrix of latent relationships’, Journal of Family Issues. doi:10.1177/019251383004003002.

- Rossi, A. S., & Rossi, P. H. (1990). Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life Course. De Gruyter. doi:10.4324/9781351328920

- Sanner, C., Ganong, L. and Coleman, M. (2020) ‘Families are socially constructed: pragmatic implications for researchers’, Journal of Family Issues. doi:10.1177/0192513X20905334.

- Santos, J. D. and Levitt, M. J. (2007) ‘Intergenerational relations with In-laws in the context of the social convoy: theoretical and practical implications’, Journal of Social Issues 63(4): 827–43. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00539.x.

- Schneider, D. M. (1980) American Kinship. A Cultural Account, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Schwartz, L. L. (1993) ‘What is a family? A contemporary view’, Contemporary Family Therapy 15(6): 429–42. doi:10.1007/BF00892290.

- Serovich, J. M., Chapman, S. F. and Price, S. J. (1992) ‘Former in-laws as a source of support’, Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 17(1–2): 17–26. doi:10.1300/J087v17n01_02.

- Taylor, R., Chatters, L., Cross, C. J. and Mouzon, D. (2022) ‘Fictive kin networks among African Americans, Black Caribbeans, and Non-Latino Whites’, Journal of Family Issues 43(1): 20–46. doi:10.1177/0192513X21993188.

- Thomson, E. (2017) ‘Family complexity and kinship’, in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, American Cancer Society, pp. 1–14. doi:10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0437

- Widmer, E. D. (2006) ‘Who are my family members? Bridging and binding social capital in family configurations’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 23(6): 979–98. doi:10.1177/0265407506070482.

- Williams, R. (2012) ‘Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal Effects’, The Stata Journal 12(2): 308–31. doi:10.1177/1536867X1201200209.

- Zartler, U. (2014) ‘How to deal With moral tales: Constructions and strategies of single-parent Families’, Journal of Marriage and Family 76(3): 604–19. doi:10.1111/jomf.12116.