ABSTRACT

The academic literature offers different views on the strength of Ukraine’s civil society, but Ukraine’s massive civic engagement and collective action, most recently in defense against Russian aggression, offers a startling picture of grass-root activism. Based on interviews, surveys and archival research, we highlight changes and nuances to Ukrainian civil society, civic engagement and motivations over time, from Euromaidan, through the hybrid Russian aggression in the East, to the recent full-scale Russian invasion. In doing so, we explore a more inclusive understanding of civil society complemented by sense of community and community responsibility.

Introduction

This manuscript explores what motivated Ukrainians to be part of Ukraine’s civil society and identifies the ways in which they participated and engaged. It also explores this question over time, from the Euromaidan years through to the current full-scale Russian invasion.

Traditional organizational and structural civil society measurements suggest that Ukraine’s civil society is weak (for example, only 8% of citizens reported engagement in civic activities in 2019 and 90% of Ukrainians didn’t belong to civic organizations in the same years (Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation Citation2019a)). However, literally overnight, on 24 February 2022, we saw massive numbers engaging in civil resistance to the aggressor. By April 2022, up to 80% of the Ukrainians were involved in civic resistance (Rating Group Citation2022; Onuch et al Citation2022; Melchior Citation2022). This gigantic and seemingly spontaneous leap in civic engagement shaped our exploration.

To make civil society ‘analytically useful and empirically manageable, many scholars have limited their analysis to formally registered NGOs’ (Stewart and Dollbaum Citation2017: 208). NGO viability is an important indicator of civil society strength. Formal measures of NGO strength can include membership totals, financial sustainability, grants or donations received, and volunteer hours with civic organizations. Using such measures facilitates comparative study and avoids the complex social, political and cultural forces that shape it. But as Stewart and Dollbam suggested, ‘Non-formal actors have not yet found their way into civil society literature to a satisfying degree. Consequently, we argue for a broader definition of civil society’ (Citation2017: 208).

This article builds on this work by highlighting informal action (Krasynska and Martin Citation2017) as a vital component of civil society and expanding the definition of civil society anchored to motivation and action rather than organizational membership or other structural functional measures. In Ukraine, people tend not to belong to formal organizations but seem very involved in civil society-like activities. In societies dominated by informal activity (culturally, socially or politically) civil society appears unorganized, unfocused and unsustainable. In the case of Ukraine and other informal settings, not only might those formal measures miss much of the story, they may be misleading (Udovyk Citation2017; Ishkanian Citation2015; Solonenko Citation2015; Worschech Citation2017; Aliyev Citation2015; Falsini Citation2018).

Ukraine’s Euromaidan and subsequent Russian aggression in the East provides a case in point. The majority of Euromaidan participants didn’t belong to any civil society organization (Solonenko Citation2015). However, GfK Ukraine reported in 2014 that 65% of Ukrainians donated money for charity (much went to defense efforts) and 15% volunteered actively. As such, we observed a spike in civic activity during this period.

By November 2021, however, the Democratic Initiatives Foundation reported that only 4% of Ukrainians were actively involved in civil society organization activities (another 15% joined rarely). And only 7% claimed to be regular participants in community events. According to the same poll only 22% donated money to charitable or civil society organizations in the 12 months prior (USAID/ENGAGE Citation2021). In other words, we saw a decline in civic activity after the zeal of the Euromaidan years.

Then, in 2022, in the aftermath of the Russian full-scale invasion, researchers observed that 60% to 80% of Ukrainians were engaged in various kinds of civic resistance (Rating Group Citation2022; Onuch et al. Citation2022; Melchior Citation2022). The Russian full-scale invasion seemed to re-awaken that fierce sense of civic responsibility to defend community and nation.

Framed within that complex historical setting, our research questions are thus (1) What actions actually stand for civil society engagement (i.e. what is civil society); (2) What are the motivations for such actions (i.e. why do people engage) and (3) How did action and motivation change over time?

To address these questions, we asked respondents (n = 1000) about the kinds of civic activities they engaged in (both formal and informal). Building on previous survey work of this nature, we offered a distinction between membership in clubs and organizations and participation in and attitudes towards civic action more generally. We also asked what motivated them to engage in these behaviors. We asked them to define civil society and indicate whether they considered themselves part of it, and why, as we suspected a disconnect existed between the literature on civil society and the perceptions of our respondents – it also provides a check on both activities and motivation. Finally, we compare results across three periods of time, which the respondents evaluated retrospectively: after the full-scale Russian invasion (from February 24 to September 2022); in the previous years (2018–2021) and in the period of Euromaidan and the first years of the Russian aggression (2014–2017).

We found that Maidan and the full-scale Russian invasion spurred civic-mindedness, while such behaviors dropped during the relatively calm period between these two events. More intriguing, we found that sense of community (SOC) (Nowell and Boyd Citation2010) emerged powerfully, and Ukrainian civil society-like activities (formal but especially informal and membership-oriented but especially action oriented) seem to be connected to its emergence. Following researchers seeking to expand the definition of civil society, we believe SOC and the related SOCR (responsibility) may be important contributions to the civil society literature and our understanding of Ukraine.

Below, we first explore the concept of civil society and its somewhat complicated definition to frame our discussion. We then address the literature on civil society in Ukraine and in post-communist settings generally, describing the evolution of scholarly thinking on the topic. We then explain our methods, present our findings and discuss the implications of our results for definitions of both civil society and SOC. We conclude by summarizing our key findings and suggesting avenues for further research.

Defining civil society

‘Since the term “civil society” regained prominence in the late 1980s, it has been notoriously difficult to define what exactly it comprises’ (Stewart and Dollbaum Citation2017: 208). Salamon and Anheier’s (Citation1998) groundbreaking effort defined civil society and developed a mechanism for cross-national comparisons of civil society strength. They anchored their analysis to a structural and organizational definition, targeting the nonprofit sector as a proxy for civil society. Their work and the insights it spawned has dominated the field, and for good reason. It is objective and produces data comparable across nations. And it had face validity in many settings. In the first years of Ukraine’s independence, most people perceived civil society and NGOs as synonymous (Ghosh Citation2014: 2).

Lewis (Citation2004) sought more nuance, suggesting ‘Civil society is commonly understood as “the population of groups formed for collective purposes primarily outside the state and the marketplace”’, which suggests a more diverse definition. However, he added that civil society might be best considered, ‘an intermediate associational realm between the state and family populated by organizations which are separate from the state, enjoy autonomy from the state and are formed voluntarily by members of society’ (301), seemingly including organizational membership as an integral component of civil society.

There is a stream in the literature, however, that overtly seeks to expand the definition of civil society to capture informal activity. Mendel (Citation2010) grappled with the definition between civil society and the nonprofit or NGO ‘sector’, reminding us of Van Til’s (Citation2000) suggestion of a ‘third space’.

Given the fuzzy overlap in our understanding of these terms, it is not surprising that some thinkers equate the two. Elizabeth Boris, for example, has gone as far as to suggest that ‘civil society’ refers to the formal and informal associations, organizations, and the networks between individuals that are separate from, but deeply interactive with, the state and the business sectors. (Mendel Citation2010; Boris Citation1999)

Reflecting a more open and non-organizational definition, a UNDP (Citation2017) report defined civil society in Ukraine as ‘a domain/area of social/civil relations beyond the household/family, state and business, where people get together to satisfy and/or promote joint interests and to defend common values’ (2). This interpretation of civil society stands out as not referring to organizational membership as a criterion. Stewart and Dollbaum (Citation2017) would have concurred, especially in the context of Ukraine, arguing,

For the post-Soviet space, the literature on other forms of civic activities is less abundant – despite the fact that students of post-Soviet societies point to the central role of informal networks in social life and political engagement since Soviet times. … Rather than focusing on specific actors, we conceptualize civil society as an intermediate sphere that works as a transmission belt between society, business and the state. Both formally registered and informal, spontaneous coalitions of citizens can perform this task. (208)

Defining civil society in post-communist settings

According to Victor Stepanenko (Citation2006: 577),

the major problem of the post-communist (especially post-Soviet) societies lies in the substantially deformed (during the communist rule of the Soviet period) societal structures of those societies, the main deficiency of which is the weak development of the values and traditions of civicness. [italics in the original]

The Western academic literature tends to adopt an organizational approach. According to Larry Diamond, for example, ‘civil society encompasses a vast array of organizations, formal and informal’ (Diamond Citation1994: 6). Using this organizational approach, Howard (Citation2002, Citation2003) labeled post-communist civil society ‘weak’ referring to Salamon and Anheier’s World Values Survey to define civil society as membership in any of nine different types of organization (charitable, religious, recreational, labor unions, professional associations, etc.) (Howard Citation2002: 158–9).

Other studies seemed to confirm this evaluation. Allina-Pisano wrote about the ‘façade’ or ‘Potemkin’ civil society, addressing the relatively high numbers of registered CSOs in post-Orange revolution Ukraine in combination with low participation numbers (Citation2010: 238). Derogatory terms like ‘NGOisation’ of society (Ishkanian Citation2015: 59) or ‘NGO-cracy’ (‘professional leaders us[ing] access to domestic policymakers and Western donors to influence public policies, [although] they are disconnected from the public at large’ (Lutsevych Citation2013: 4)) have been coined.

Ljubownikow et al. (Citation2013) suggested instead that,

Despite the controlled and institutionalized nature of civil society arrangements, small and ‘illegal’ grass-roots networks did exist. … These networks helped Soviets to mitigate the effect of continuous scarcity of basic consumer goods and facilitated access to other necessary resources. This culture favored ‘circles of intimacy and trust among family members and close friends. (156)

Shapovalova and Burlyuk interviewed such activists in Odesa and Kharkiv in 2018, who claimed that ‘activism (or active citizenship, as some of them prefer to call it) is not a job at an NGO, but a way of life’ (Shapovalova and Burlyuk Citation2018: 33). They concluded that, while post-Soviet civil societies were ‘organizations without citizens’, after Euromaidan one could observe the phenomenon of ‘citizens without organizations’ (Shapovalova and Burlyuk Citation2018: 22). Stepaniuk (Citation2022) highlighted that ‘in environments with high degrees of informality, everything functions through personal connections, making informal networks key to “getting things done” in public and personal life’ (3).

As the Russians launched their full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022, ordinary citizens, as well as businesses, leveraged their skills and resources to support their fellow citizens, as Stepaniuk might predict, in informal ways. Private schools such as A+, Optima and the European collegium offered free online lessons to all children. Kyiv businesses Goodwine, TH Technology Trade, and Nova Poshta delivered supplies to defense and humanitarian outlets. Food vs Marketing, Sto Rokiv Tomu Vpered, Khlibnyi, and the Borysov network cooked meals. And the popular Ukrainian fashion brands ‘MUST HAVE’ and Kachorovska provided protective clothing and boots (Zarembo and Martin Citation2022). These actions all required planning, pre-existing social infrastructure, and the ability to leverage skills in organized settings. They required supplies and funding. They required leadership, power, trust, a common mission and a culture of engagement and belonging.

We believe these are examples indicative of a powerful and effective civil society. Some Ukrainian military success has even been reported to be, in part, the result of civic-minded behavior. A Wall Street Journal commentary suggested civil society was Ukraine’s ‘secret weapon’ against Russia, ‘Ukrainians have spent the past eight years strengthening their ability to govern themselves, and a vibrant civil society is proving to be a significant advantage in the war against Russia’ (Melchior Citation2022). According to USAID (Citation2022), ‘Ukraine is home to a robust civil society … [But] despite notable progress, civil society and media organizations often lack financial stability, influence, and training to effectively function’ (1).

Again, we see the influence of formality and macro-organizational concerns. If CSOs lack financial stability, influence and training, what do they believe is robust about Ukrainian civil society? We believe they are referring to what we expose in this manuscript. There is something more to civil society than the strength of CSOs which has led researchers to conclude that

a broader conceptualization of civil society – looking beyond formally established organizations and inclusive of social movements, non-registered civic groups, local, small scale and online activism as a form of collective but also individual behavior – seems to reflect better the nature of civil societies in post-communist countries, as well as the changing nature of civil society in the twenty-first century more generally. (Burlyuk et al. Citation2017: 5)

Weighing all of these perspectives, and seeking a ‘broader conceptualization of civil society’ we see civil society as voluntary, civically minded activity, beyond the household and family, and not including the state or the market. Actions, whether individual or collective, formal or informal, private or nonprofit, that are motivated by civically minded values, constitute civil society.

Support from sense of community

The Economist (16 April, Citation2022) declared, ‘Being Ukrainian is […] about the ability to come together when you feel that you need to and to get things done’. We believe SOC (Nowell and Boyd Citation2010) helps our understanding of ‘coming together to get things done’, capturing the civic, pro-social and community-minded behaviors visible in Ukraine. Their work helped interpret our findings of civic engagement in the absence of formal participation by addressing responsibility, belonging, shared values, emotional connection and civic engagement both inside and outside formal organizations. We believe this proves an important perspective to embrace in parallel to, or as a precursor to, studies of formal civil society.

Community settings evoke a sense of duty, obligation and responsibility to the communities to which one belongs. Sarason (Citation1974) described SOC as ‘the sense that one was part of a readily available mutually supportive network of relationships upon which one could depend’ (1). McMillan and Chavis (Citation1986) argued for a four-factor model of SOC that would prove central to the concept; belonging, influence, fulfillment of needs, and shared emotional connection. To feel this SOC, individuals need to feel as though they belong to a community, however defined, that they can influence that community, fulfill their own needs of support, and they do so because of their shared values and emotional attachments.

Nowell and Boyd (Citation2010) further developed that concept adding sense of community responsibility (SOCR) to the literature. While SOC correlates with affective and needs fulfillment, SOCR correlates with a host of community involvement behaviors such as political participation and community engagement in residential and geographical communities.

SOCR suggests that people enter into collective settings with pre-existing individual beliefs, norms, values, and ideologies. They also have some notion of their own needs. Those needs are then played out in a community context. If alignment is reached with others, individuals develop a sense that they are part of a community with feelings of belonging, emotional connections or togetherness. In addition, they might develop a sense of responsibility to that community, in terms of a duty or a need to care for others.

This is the heart of their model and these two concepts (SOC and community responsibility) are inter-related. First, individuals identify with the collective, although proximal relationships might differ (community as country, region, city, or friend group, for example). They then consider their responsibility to this community, the extent to which they ‘owe’ this community, or feel the need to give back to the collective. Those feelings ultimately lead to engagement and collective action.

Their model helps explain the informal spontaneous civic actions we saw unfold, at multiple times in Ukraine’s history, which seem to be aspects of civil society not captured by formal measurement. We believe SOC and SOCR might capture what civil society does not, bridging the gap between formal and informal action, collective and individual, and attitude and action by adding the important elements of pre-existing norms values and beliefs, coupled with community-related variables such as belonging, influence, fulfillment of needs, shared emotional connection that co-vary with responsibility to and influence over that community.

Methodology

Background

We began our work by examining four significant nation-wide polls to understand prevailing operationalizations of ‘civil society’ in Ukrainian data. We detail the key variables in each of these studies in Appendix. We drew insight from each of these studies.

The Monitoring, conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine yearly since 1992 (Monitorynh sotsialnykh zmin Citation2018) features questions about participation and membership in political parties and civic organizations and activities respondents engage in, including protests and demonstrations. The Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundations (DIF) was also established in 1992 and has continuously monitored civic attitudes to civil society (Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b), asking about civic activity, membership in civic organizations, unions or parties and voluntary work.

The ENGAGE project implemented by Pact in Ukraine with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (USAID/ENGAGE Citation2017, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2021) was launched in 2016 ‘to increase citizen awareness of, and engagement in, civic activities at the national, regional and local level’. These semiannual surveys measure membership in CSOs, protest moods of the citizens, charity, community activism and how respondents take part in the life of their community.

Finally, the Cedos study launched just after the invasion (Cedos Citation2022), focused on the impact of the war on civilians. This poll asks about types of volunteering including information dissemination, signing petitions, posting on social media; as well as physical assistance (weaving camouflage nets, managing shelters, preparing and delivering food and materials); coordination work (transportation, temporary housing, directing people to resources); financial support (donating to the war effort or charities); and redirecting professional activities to those in need (psychologists, translators, media workers, etc.). They also identified motivations behind these efforts, including volunteering to support their own mental state, desire to help others, a sense of patriotism, a sense of duty and the fact that they had available resources that could be of use to others.

Our instrument

We developed our initial survey by including elements of all of the surveys above. We used their definitions to provide respondents with choices and to allow us to compare our work with their previous efforts. We piloted our survey through semi-structured interviews (n = 7) conducted in July and August 2022. These interviews helped us frame our questions more effectively and led to a more developed survey instrument by adding options we hadn’t considered or weren’t included in previous polls. We talked to two entrepreneurs, a stay-at-home parent, a student, an NGO worker, a pensioner, and a university professor (three women and four men).

We then launched our national survey through an online panel, with follow-up phone interviews to complement the survey sample where representation was needed. (n = 1000). On average the survey took 14 min to complete. The survey is representative of urban residents by age, gender and location (survey, details and full results available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HX3QY).

Sampling was stratified by size (populations above and below 50,000), and geography (6 macro-regions consisting of 24 administrative oblasts and the capital, Kyiv, divided into two groups by city size). The sample covers all regions of Ukraine controlled by the Ukrainian government. We used the Voting Commission database as the official data source of electoral statistics, such as total number of eligible voters, distribution by oblast, settlement and precincts, urban-rural division, etc. Gender and age distributions were obtained from the Ukrainian State Statistical Service (1 January 2022).

Sampling procedure

The research population corresponded to the statistical distribution of the population of Ukraine (over 18 years) by region, size of town, gender and age groups. We oversampled to compensate for respondents who do not fit our criteria or refused participation. We selected the online panel sample by screening questions regarding residence, gender and age. Respondents who met the criteria were invited to participate after informed consent and guarantees of confidentiality. Sampling groups that were not sufficient after the online panel survey (mainly residents of smaller cities and older age groups) were interviewed by phone. We used a stratified random sample of mobile phones defined by the three-digit operator prefixes, followed by a random generation of the rest of the number. Mobile phone prefixes in Ukraine do not match specific territories, leaving random selection as the best solution.

Limitations

The online surveys over-represented more educated, socially active, and technically skilled respondents. We believe the higher educational level of people in the phone subsample was due to the topic of the study being of interest. Populations movements also limited the study. In July 2022, the EU estimated 3.2–3.7 million Ukrainians were in EU countries. Among the total approximately 30 million adult citizens (estimated at the time of the full-scale invasion), roughly 10% left the country, and it’s difficult to obtain reliable survey data for these citizens. Nearly 83% of our respondents reported no change in residence (6% changed countries, 9% changed oblasts, and 2% changed residences within the same oblast). We also note that those with ‘pro-Russian’ sentiments seemed more likely to end the survey or seemed insincere when they did respond. We removed these results from our findings, often based on inappropriate comments in open-ended questions.

Findings

We frame our findings below with quotes from our preliminary interviews as well as open-ended responses from the survey to contextualize the data. We coded all of the responses in a grounded fashion, then grouped sub-codes into higher order codes. It is important to distinguish this from theoretical coding. We did not impose our theoretical assumptions on this data. What emerged below is grounded theory development interpreting responses to the following questions.

What is civil society?

We wanted to learn whether respondents had the same conceptions of civil society as the literature suggests. Accordingly, we asked respondents to offer their definition of civil society. Of 897 total responses to this question, 775 were usable. Most definitions included multiple components of the coding scheme evident in Table for in the Appendix. We note the frequency of responses across coded variables, but that is of less importance than the categories that emerged from our second round of coding. Very few definitions equate in any way to the structural, functional definitions of civil society. And many seem to relate quite fittingly to SOC.

First, the definitions included a referent group. For example, respondents reported society, citizens, residents, a community, a group, collection or set of people as targets. Only 6% referred to an organization or NGO. For example, respondents reported that civil society was ‘an association of citizens for the maintenance and development of common interests and the achievement of a collective goal’ or ‘a society of active, caring and nationally conscious citizens’.

They mentioned mindsets, describing the sentiment of working together, being unified, maybe facing a common enemy. Many highlighted that civil society was not the government, business or elite. Most mentioned action, highlighting the need to help, improve or take care of certain portions of society. Others stressed the need to participate, communicate and interact with other people. Only two individuals mentioned the word ‘volunteering’.

Many referred to what we coded as a worldview, referring to statements that civil society reflects responsibility, caring and others-oriented thinking. We included the aim of having influence and fostering change, finding solutions to problems and generally being conscientious. Finally, most pointed out the goals of civil society, such as representing common interests, uniting around goals, supporting values of independence, human and legal rights, democracy and having mutual respect for difference. Some suggested ‘a group of people united by one territory, common values, rights and rules’ or ‘a set of citizens living in a certain territory, bound by ideology, values and a common set of tasks’.

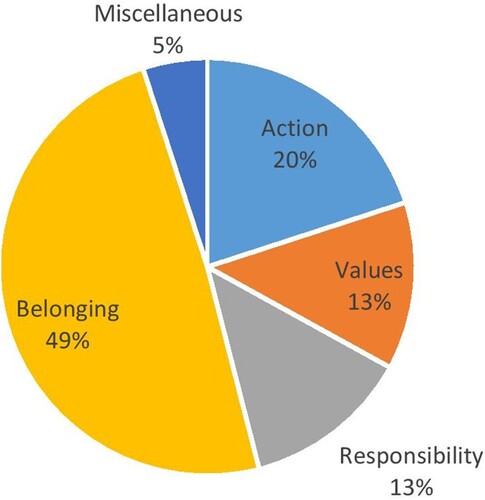

Others had more nuanced definitions, such as ‘a community of people united by certain social norms, which actively promotes their fulfillment by all members of the group and makes efforts to create favorable conditions for the life of all members of the group’ or ‘a society where people care about each other, learn the history of their people, treat state symbols with respect, are not indifferent to politics, know that they have influence and are responsible for their actions’. Our open-ended coding of all the responses resulted in five main themes displayed in (detailed coding results are available in Appendix).

Are you part of civil Society?

This question was not in previous polls, but we asked overtly whether respondents felt they were part of ‘civil society’. Surprisingly, given the clear lack of formal engagement in Ukraine discussed above, 83% of our respondents believed they were a part of civil society with only 6% disagreeing. They believed they were part of civil society, despite their answers not aligning with formal (structural organizational) definitions of the concept. They were then asked to comment more generally about why they considered themselves part of civil society (or not).

I feel that right now I am a Ukrainian, a solid part of Ukrainian society, Ukrainian civil society. Before that, I was Ukrainian simply by the fact that I was born in Ukraine, I did not feel my belonging to Ukrainians, to civil society, because I did not feel it. After February 24 – actually, after 2014, but after February 24 more sharply, I feel incredible pride for myself, for being Ukrainian, and for those people who are Ukrainian and have achieved something, even if it is not related to the war. I already look at things differently and understand that these are ours, they are Ukrainians.

It is not only a society that lives in a territory determined by borders, the Constitution, rules, but it is a society that is united by common values, a central common idea and understandings of belonging to this great community, to something greater, understanding of patriotism and understanding oneself as part of something bigger. Until February 24, I would definitely have given a different answer, but now I feel this way.

More often, responses were along the lines of,

To me civil society belongs to an active part of citizens who cannot influence the decision-making directly and so try to unite their efforts so as to influence these decisions from the bottom. So, we belong to the citizens who do not possess power but can influence the decisions of those in power and the fate of the country, how the societal issues are solved.

I consider myself a part of Ukraine's civil society. I take part in this, I inform people, communicate with them, support them. I have a pro-active civic stance. Civil society is a community of people who are active citizens of their country; who apply efforts of any kind so that this country continues to exist.

What makes an individual a part of civil society?

We believe this question offered respondents the ability to operationalize their understanding of civil society engagement. Using open-ended responses to learn how respondents reacted to these questions in their own words, we coded these 828 responses inductively, coding each aspect of the response and grouping similar findings together (detailed coding results are available in Appendix) ().

We saw four distinct orientations emerge; Action, Community, Values, and Belonging. Action oriented responses constituted responses about the desire to help, active participation, communicating and interacting with others. A very small percentage reported actual volunteering or donating money. Many also seemed to include public sector sentiments, such as paying taxes and abiding by laws. Many others responded with more of a community orientation, highlighting working together, being united, working with like-minded people and simply being together. Some also included family orientations here. Other responses were coded into values-based thinking about having common values, being conscientious, and sentiments of love and respect for others. Responses also coalesced around responsibility, highlighting that civil society implied duty, care and having influence. The largest grouping of codes, however, revolved around belonging. This ranged from all people, to citizenship, to society, to Ukraine. But most felt that by being in the country, living and working there, they were a part of civil society. Only eight respondents mentioned ‘being a member of an organization’ in any way.

These groupings reflect portions of responses. Typical responses included multiple aspects of the coding scheme above. For example: ‘My contribution is insignificant, but by starting the changes with myself, I contribute to the changes of the people around me for a better life, the defense of state values and participation in public events’ would be coded as having elements of Action and Values. This statement, ‘By supporting and helping others, you feel like a part of a great state, which means you are needed and your role is important!’ would be coded as having elements of Community and Belonging. Another commented, ‘I feel the ability to influence the decisions of my country, to change something. Because currently it is not important whether a person belongs to any organization or not, because information can be received/distributed in social networks’. Others stressed responsibility, such as, ‘I know that my actions can affect something, I need to stand up for a position, even for those who cannot do it themselves. My children live in this country’.

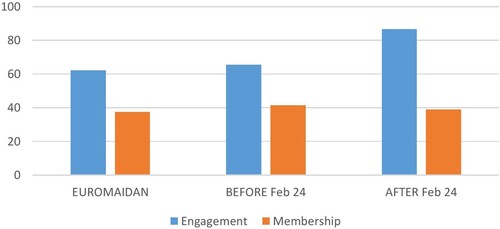

In what ways do you participate in civil society?

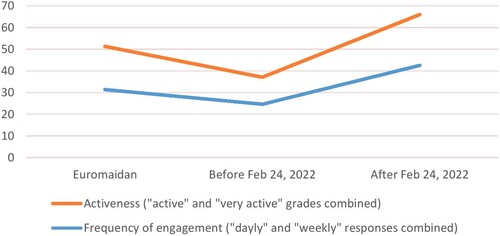

Our findings confirmed that Ukrainians engaged in ‘other’ types of civic engagement rather than organizational membership (formal or informal). There were subtle increases in participation over time for civic organizations and OSВBs, but likely due to the war, membership in trade unions, sports, youth and church groups decreased. Overall, participation as measured by memberships remains low ().

Table 1. Engagement in civic activities vs membership in organizations in Ukraine.

While trade unions, civic organizations and OSBBs are the most popular organizations (their membership constitutes 8%–12% across the periods), Ukrainians dedicated their energy to other activities. The top three types of action during the three periods differed only slightly. During the Euromaidan time and the first year of the Russian aggression the most popular activities were material donations (34%), informal volunteering (18%) and protests and signing petitions (17%). In 2021, which stands in our survey for as relatively calm period, the most popular activities remained the same but engagement differed: 34% donated things, 26.5% signed petitions and 16.3% volunteered informally. We attribute the higher share of petition-signing to the fact that since 2014, electronic petitions became more widespread and accessible. After 24 February 2022 the most popular activities remained the same but the figures skyrocketed: 70% provided material help, 39% volunteered informally and 34% signed petitions. Protests dropped to 6% since mass gathering were forbidden under martial law, however, the figures may refer to protests against the occupants. Awareness-raising activities rose from 13% in 2014 to 22.5% in 2022.

We also asked about monetary donations. Donations steadily increased over time, with nearly 80% donating in some form since the full-scale invasion. Donations in cash decreased from 52.5% in 2014 to 26% in 2022 as online banking has become a dominant way of money transfer, constituting 43.5% in 2014 and 70.5% in 2022 ().

What motivated your participation in civil society?

This question complements previous studies that highlighted motivation. Most respondents suggested that helping others and fostering change motivated their participation. Over 75% suggested these as their top motivating factors; 56.4% reported defense as a motivator. Nearly a third suggested that engaging in civil society aligned with their personal beliefs and a quarter made statements to the effect that they simply couldn’t stand by without acting ().

Table 2. What motivated or prevented engagement in civic activities.

How has civil society involvement changed over time? (Engagement fluctuations)

We expected to see spikes in activity provoked by the jolts associated with Euromaidan and the full-scale Russian aggression. This was only partially confirmed, with engagement figures during and after Euromaidan being generally comparable and at times, the ‘calmer’ period featured even more engagement (e.g. donations) than the tumultuous 2013–2014 period. However, we do see fluctuations in two variables: frequency of engagement and self-perception of one’s activeness. During both Euromaidan and the Russian full-scale invasion, we saw spikes in activity and in their own evaluation of their activeness. Also, during the full-scale invasion, in contrast to Euromaidan, considerably fewer people described themselves as passive (55% against 36%; those who self-rated as ‘1’ and ‘2’ combined). The tables include data from the three time periods for comparative purposes ().

Discussion

Our respondents, discussing and responding to questions specifically about civil society, aligned with almost all the definitions of civil society except attachment to organizations, or formal or official types of engagement. Our respondents instead anchored primarily to informal action or participation as ways to engage. Many mentioned a desire to help or having an impact. Others stressed the need to communicate and interact with others. Very few of our respondents suggest organizational outcomes in their responses. Of nearly 1000 respondents, hardly anyone conflated civil society with NGOs or formal volunteering. Instead they describe themselves as values-driven, seeking common interests, and working collectively for the common good.

They talked of mindsets of togetherness and unification and worldviews that included caring, responsibility towards others, and ability to influence and change their community. They spoke of values, common interests, common goals and mutual respect for different perspectives. And they wrote about action – helping, improving, participating, listening and getting involved. They did speak of different referents, whether society, citizens, community or small groups. But few even mentioned the words ‘organization’ or ‘NGO’.

Many highlighted the community context was indeed played out in an emergency setting, with some overtly mentioning war and defense as the setting in which their values emerged. While some referred to this as being a patriot or defending country in a time of war, others felt their responsibility or duty was to care, have opinions and express them. Others felt they had a responsibility to use their influence to make change.

As such, these responses align well with the SOC’s four main factors (McMillan and Chavis Citation1986) of belonging (to society, community or groups), influence (to change and improve), fulfillment of needs (defense, interest, being aware) and shared connections (common interests and mutual respect). They also captured Nowell and Boyd’s (Citation2010) concept of community responsibility (wanting to help, being responsible, caring for others and defending rights). The alignment of the responses with SOC is also noteworthy, since this concept was never presented to the respondents, unlike civil society, which seemed commonly and clearly understood. Interestingly, their understanding of the term ‘civil society’ is a change marker in itself, since in 2002, 40% of respondents to a similar survey had only a vague notion of what civil society was (Stepanenko Citation2006: 575). As mentioned above, community settings indeed evoke sense of duty, obligation and a feeling of responsibility to the communities to which one belongs ( Nowell and Boyd Citation2010). But we did not impose this model on our findings. Our respondents pointed out the values they espoused that led to them considering themselves part of civil society.

Implications for the field

This work provided us with an understanding of civil society in Ukraine which extends beyond many scholarly definitions – beyond the organizational approach, and beyond the formal vs informal dichotomy – by capturing values and feelings that are not typically associated with civil society operationalization. Measures of civil society, in order to facilitate comparative studies, especially for the United Nations, international development assistance agencies and NGOs, tend to focus on formal, structural and organizational data aligning with definitions offered by scholars in the tradition of Salamon and Anheier (Citation1998). These are not antithetical to our findings, they simply measure something different, formal engagement.

Our concern is that the lack of formal engagement might (misleadingly) suggest a lack of civil society. Our findings demonstrate a deep and well-understood conceptualization of civil society by our respondents. They simply do not register, become members, or consider formal organizations as ‘the’ definition of civil society. They instead point to belonging, community, responsibilities and action for the common good, which we feel aligns with the sentiment of civil society. That Ukrainians choose not to become members of formal organizations in order to act reveals the social, political and historical legacy of their country, exactly the types of variables not captured in the formal definitions. We highlighted these in our findings.

While there is a distinct and keen sense of civil society among the Ukrainian population – at least among the more active strata in our sample – the understanding of what civil society constitutes goes beyond formal member-based definitions and even some informal types of activities, like volunteering. Instead, civil society in Ukraine seemed to be understood widely not only through action, collective or individual, but also through values, responsibilities and SOC. As Matviychuk (Citation2017) points out,

When Ukraine meets new challenges, it is civil society which quickly reorganizes in order to meet those challenges. … The Maidan acted as a sort of catalyst for the development of civil society and the creation of a powerful volunteer movement. (1)

Ekiert and Kubik (Citation2014) pointed out that,

while strength and weakness are not very useful categories, we have shown that some civil societies in the region have dense and comprehensive organizational structures, operate in a friendly institutional and legal environment, and have some capacity to influence policy making on local and national levels. In other post-communist countries, especially those that have reverted to various forms of authoritarian rule, civil societies are often organizationally weak and politically irrelevant. Civil society actors are shut out of routines consultation and governance and come together to influence politics only in extraordinary moments of rage triggered by economic downtown or gross state violations of laws and constitutional provisions, as witnessed recently in Ukraine. (55)

Conclusions

Ukraine’s civil society activity has fluctuated over time. It peaked at moments, soon returning to lower levels. While there were lulls, the desire to protect country and community at various times motivated an increase in civic action. The Orange Revolution, the Maidan period, and the full-scale invasion by Russia seemed to spur this dormant civil society into mobilization through powerful and widespread examples of informal collective action to unite and face challenges.

While existing scholarship on civil society favors more instrumental variables such as membership in formal or informal organizations, we found that values and actions, and motivations for both, can be helpful to better understand civil society. Moreover, the existing SOC theoretical model captured these well. We see theoretical alignment between civil society scholarship and SOC, which we offer as a contribution to enhance both literatures.

These findings are important because aid organizations often base programming and budgets on traditional measures of formal civil society. We suspect that informal organizing anchored to SOC and SOCR may be a more accurate determinant of civil society strength or perhaps a correlated mindset operating in parallel to traditional CSOs. As a result, effective assistance might take different forms, tapping informal actors and networks. Perhaps grants should be made to individuals and small informal teams, alongside actual CSOs. Trainings, mini-grants and workshops for and by informal stakeholders might build trust between them and CSOs. More research is needed to explore whether citizens would be willing to engage with grassroots organizations, CSOs and NGOs – and importantly, under what conditions. Regardless, aid agencies need an accurate understanding of civil society, perceptions of NGOs, and trust in civic associations in order to more effectively provide assistance, especially when the war ends and rebuilding begins. This should not be based solely on formal structural organizational measures.

Our findings help make the case that SOC and SOCR are powerful forces in Ukraine and may lead to or enhance more formal civil society in the future. This force should be tapped. A theoretical coding explicitly targeting this would be a helpful direction for future research as would research examining whether SOC complements studies of civil society in other national or situational contexts, especially in more formal settings. Regardless, we believe we tapped an important field of study anchored in community psychology to enhance the civil society literature. We clearly found that, in Ukraine, SOC and SOCR serve as powerful drivers of civic mindedness, and Ukrainian civil society-like activities (formal but especially informal and membership-oriented but especially action-oriented) seem to be connected to its emergence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers, especially for pushing us to more carefully integrate Sense of Community and Civil Society. We thank the British Academy’s Program within Writing Workshops Grant WW21100027 for connecting us and supporting this work. A special thanks to Bucknell University, a private donor, and Natalia Kharchenko of the Ukrainian-based Pollster for assistance in launching the survey. A special note of thanks goes to the LOEWE initiative (Hesse, Germany) within the emergenCITY center for their support of Dr. Zarembo during this time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kateryna Zarembo

Dr. Kateryna Zarembo is a guest researcher at the Technical University Darmstadt (Germany). She is also a lecturer at the National University of 'Kyiv-Mohyla Academy' and an associate fellow at the New Europe Center (Kyiv, Ukraine). Her area of expertise is foreign and security policy as well as civil society studies, with a focus on Ukraine.

Eric Martin

Dr. Eric Martin is a Professor of Management in Bucknell University's Freeman College of Management. He has published on civil society, international development, crisis management and cross-sectoral interorganizational relationships.

References

- Aliyev, H. (2015) Post-Communist Civil Society and the Soviet Legacy: Challenges of Democratisation and Reform in the Caucasus, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Allina-Pisano, J. (2010) ‘Legitimizing facades: civil society in post-orange Ukraine’, in P. D’Anieri (ed.), Orange Revolution and Aftermath: Mobilization, Apathy, and the State in Ukraine, Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 229–53.

- Boris, E. (1999) ‘The nonprofit sector in the 1990s’, in C. T. Clotfelter and T. Ehrlich (eds.), Philanthropy and the Nonprofit Sector in a Changing America, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 1–33.

- Burlyuk, O., Shapovalova, N. and Zarembo, K. (2017) ‘Introduction to the special issue. civil society in Ukraine: building on Euromaidan legacy’, Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal 3: 1–22.

- Cedos (2022) The First Days of Full-scale War in Ukraine: Thoughts, Feelings Actions, https://cedos.org.ua/en/researches/the-first-days-of-full-scale-war-in-ukraine-thoughts-feelings-actions-analytical-note-containing-initial-research-results_/#:~:text=During%20the%20first%20days%20of%20the%20full%2Dscale%20war%2C%20the,property%2C%20and%20separation%20from%20family.

- Diamond, L. (1994) ‘Rethinking civil society: toward democratic consolidation’, Journal of Democracy 5: 3.

- The Economist (2022) Volodymyr Zelensky’s Ukraine is defined by self-organisation. 16 April, Available from: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2022/04/16/volodymyr-zelenskys-ukraine-is-defined-by-self-organisation.

- Ekiert, G. and Kubik, J. (2014) ‘Myths and realities of civil society’, Journal of Democracy 25(1): 46–58.

- Falsini, S. (2018) The Euromaidan’s Effect on Civil Society: Why and How Ukrainian Social Capital Increased after the Revolution of Dignity, Stuttgart: ibidem-Verlag.

- Foa, R. S. and Ekiert, G. (2017) ‘The weakness of postcommunist civil society reassessed’, European Journal of Political Research 56(2): 419–39.

- Gatskova, K. and Gatskov, M. (2016) ‘Third sector in Ukraine: civic engagement before and after the “Euromaidan”’, Voluntas 27(2): 673–94.

- Ghosh, M. (2014) Civil Society in Ukraine: In Search of Sustainability, Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Howard, M. (2002) ‘The weakness of postcommunist civil society’, Journal of Democracy 13(1): 157–69.

- Howard, M. (2003). The Weakness of Civil Society in Post-Communist Europe, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2018) Hromadska dumka hruden-2017: vyborni reitynhy i reitynhy doviry, 23 January. Available from: https://dif.org.ua/article/reytingijfojseojoej8567547 [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2019a) Hromadianske suspilstvo v Ukraini: pohliad hromadian, 7 October. Available from: https://dif.org.ua/en/article/gromadyanske-suspilstvo-v-ukraini-poglyad-gromadyan [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2019b) Balans doviry/nedoviry to sotsialnykh instytutsii, 30 December. Available from: https://dif.org.ua/article/balans-dovirinedoviri-do-sotsialnikh-institutsiy [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- Institute of World Policy (2012) How to Get Rid of Post-Sovietness, Kyiv: Institute of World Policy.

- Ishkanian, A. (2015) ‘Self-determined citizens? New forms of civic activism and citizenship in Armenia’, Europe-Asia Studies 67(8): 1203–27.

- Krasynska, S. and Martin, E. (2017) ‘The formality of informal civil society: Ukraine’s EuroMaidan’, Voluntas 28: 420–49.

- Lewis, D. (2004) ‘On the difficulty of studying “civil society”: reflections on NGOs, state and democracy in Bangladesh’, Contributions to Indian Sociology 38(3): 299–322.

- Ljubownikow, S., Crotty, J. and Rodgers, P. (2013) ‘The state and civil society in post-Soviet Russia: the development of a Russian-style civil society’, Progress in Development Studies 13(2): 153–66.

- Lutsevych, O. (2013) How to Finish a Revolution: Civil Society and Democracy in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.’ Briefing Paper, London: Chatham House.

- Matviychuk, O. (2017) Civil Society in Ukraine. Razom Policy Report. https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/defining-civil-society-ukraine.

- McMillan, D. and Chavis, D. (1986) ‘Sense of community: a definition and theory’, Journal of Community Psychology 14: 6–23.

- Melchior, J. (2022) ‘Civil society is Ukraine’s secret weapon against Russia’, Wall Street Journal, 4 April.

- Mendel, S. (2010) ‘Are private government, the nonprofit sector, and civil society the same thing?’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39(4): 717–33.

- Monitorynh sotsialnykh zmin (2018) Issue 6 (20). Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- Nowell, B. and Boyd, N. (2010) ‘Viewing community as a responsibility as well as resource: deconstructing the theoretical roots of psychological sense of community’, Journal of Community Psychology 38(7): 828–41.

- Onuch, O., Doyle, D., Ersanilli, E., Sasse, G., Toma, S. and Van Stekelenburg, J. (2022) MOBILISE 2022: Ukrainian Nationally Representative Survey (KIIS OMNIBUS). (N=2009). May 19–24, 2022.

- Onuch, O. and Onuch, J. (2011) Revolutionary Moments: Protest, Politics and Art, Warsaw: Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and NaUKMA Press.

- Rating Group (2022) The 8th national poll: Ukraine during the war (April 6).

- Salamon, L. and Anheier, H. (1998) ‘Social origins of civil society: explaining the nonprofit sector cross-nationally’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 9: 213–48.

- Sarason, S. (1974) The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology, San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Shapovalova, N. and Burlyuk, O. (2018) Civil Society in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: From Revolution to Consolidation, Stutgart: ibidem Verlag.

- Solonenko, I. (2015) ‘Ukraine’s civil society from the Orange Revolution to Euromaidan: striving for a new social contract’, in IFSH (ed.), OSCE Yearbook 2014, Baden-Baden, pp. 219–35.

- Stepanenko, V. (2006) ‘Civil society in post-Soviet Ukraine: civic ethos in the framework of corrupted sociality?’, East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 20(4): 571–97.

- Stepaniuk, N. (2022) ‘Wartime civilian mobilization: demographic profile, motivations, and pathways to volunteer engagement amidst the Donbas War in Ukraine’, Nationalities Papers, 1–18.

- Stewart, S. and Dollbaum, J. M. (2017) ‘Civil society development in Russia and Ukraine: Diverging paths’, Communist and Post-Communist Studies 50: 207–20.

- Udovyk, O. (2017) ‘Beyond conflict and weak civil society; stories from Ukraine: cases of grassroots initiatives for sustainable development’, East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies IV(2): 187–210.

- United Nations Development Programme (2017) Defining Civil Society for Ukraine, https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/defining-civil-society-ukraine.

- USAID (2022) Civil Society and Media: Ukraine Fact Sheet, https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/civil-society-and-media.

- USAID/ENGAGE (2017) ‘Household matters and interests motivate most Ukrainians to engage in civic life’, Civic Engagement Poll, 11 December. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/household-matters-and-interests-motivate-most-ukrainians-to-engage-in-civic-life/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2018a) ‘Citizens have high standards for those in public office but low expectations about forthcoming elections’, Civic Engagement Poll, 4 May. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/citizens-have-high-standards-for-those-in-public-office-but-low-expectations-about-forthcoming-election/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2018b) ‘The dissatisfaction of Ukrainians with the current government is growing, while trust of civil activists increases’, Civic Engagement Poll, 25 July. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/the-dissatisfaction-of-ukrainians-with-the-current-government-is-growing-while-trust-of-civil-activists-increases/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2019a) ‘Civil activism and attitudes to reform: public opinion in Ukraine’, Civic Engagement Poll, 14 May. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/civil-activism-and-attitudes-to-reform-public-opinion-in-ukraine/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2019b) ‘Public opinion survey to assess the changes in citizens’ awareness of civil society and their activities’, Civic Engagement Poll, 1 August. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/civil-activism-and-attitudes-to-reform-public-opinion-in-ukraine-2/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2020a) ‘Ukrainians are aware of civic activities but unwilling to take action’, Civic Engagement Poll, 19 March. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/ukr/ukraintsi-zalucheni-do-hromadskoi-diialnosti-ale-unykaiut-aktyvnoi-uchasti/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2020b) ‘Self-help nation: Ukrainians disappointed in reforms, but ready to support each other and their communities’, Civic Engagement Poll, 9 October. Available from: https://engage.org.ua/eng/self-help- nation-ukrainians-disappointed-in-reforms-but-ready-to-support-each-other-and-their-communities/ [Accessed 20 Oct 2020].

- USAID/ENGAGE (2021) ‘Missing out on opportunities? Despite potential benefit, citizens are skeptical about engaging in CSO activities or supporting them financially’, Civil Engagement Poll, 15 November. Available from: https://dif.org.ua/en/article/missing-out-on-opportunities-despite-potential-benefit-citizens-are-skeptical-about-engaging-in-cso-activities-or-supporting-them-financially [Accessed 30 Dec 2022].

- Van Til, J. (2000) Growing Civil Society: From Nonprofit Sector to Third Space, Bloomington.: Indiana University Press.

- Worschech, S. (2017) ‘New civic activism in Ukraine: building society from scratch?’, Kyiv-Mohyla Law and Politics Journal 3: 23–45.

- Worschech, S. (2018) ‘Is conflict a catalyst for civil society? Conflict-related civic activism and democratization in Ukraine’, in N. Shapovalova and O. Burlyuk (eds.), Civil Society in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: From Revolution to Consolidation, Stuttgart: ibidem Verlag, pp. 69–100.

- Zarembo, K. and Martin, E. (2022) ‘Did Ukraine’s civil society help turn back the Russians?’ New Eastern Europe, 4 May. Available from: https://neweasterneurope.eu/2022/05/04/did-ukraines-civil-society-help-turn-back-the-russians/.