ABSTRACT

Like many European countries, the Netherlands locked down in March 2020 to combat the spread of COVID-19. Although government officials called for solidarity, the lockdown measures made it more difficult to help fellow citizens. In this study, we examine whether informal helping declined during the first lockdown in the Netherlands and to what extent changes depended on people’s resources (time/health), motivation (solidarity/COVID concerns) and opportunities (social contact). In general, we expected an overall decline of informal helping, and this decline was expected to be smaller for people with more resources, motivation, and opportunities. We used data from the SOCON COVID-19 Panel survey that were collected through internet and telephone interviews before (February 2019/2020) and shortly after the first lockdown in the Netherlands (July 2020) (N = 522). We examine the impact of resources, motivation and opportunities for informal help provided to relatives, friends and neighbors separately. Indeed, results showed that people overall helped less during the lockdown than before. The decline in helping relatives was smaller among those who lost work, were worried about relatives, experienced solidarity with others or had more contact with relatives during the lockdown. People who contacted more with neighbors during the lockdown period provided more informal help to them during the lockdown than before.

Introduction

Like many European countries, the Netherlands faced a widespread outbreak of COVID-19 in March 2020. To prevent a fast spread of the virus, the Dutch government closed schools, restaurants, bars, and gyms on March 15 and urged citizens to work from home. The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown thus severely limited people’s ability to meet the demands of daily life; some suddenly found grocery shopping dangerous, others had to balance taking care and homeschooling children and working from home. People struggled to keep in touch with friends, relatives and colleagues and had to deal with insecurity surrounding one’s safety and income during these early stages of the pandemic (Engbersen et al. Citation2020; Kuyper and Putters Citation2020). Hence, media, politicians and various civil society actors called for solidarity and encouraged people to help those in need (Elzendoorn Citation2020; Rijksoverheid Citation2020; Van de Wiel Citation2020). Such a call for solidarity is not uncommon in times of crisis. However, it remains unclear whether individuals actually respond to these calls. Although some studies report spikes in solidarity behaviors, such as (informal) helping, during rapid economic declines, terrorist attacks or natural disasters (Penner et al. Citation2005; Rotolo et al. Citation2015; Chambré Citation2020), others suggest that solidarity behaviors decline during such crises (Lim and Laurence Citation2015; Cameron Citation2021).

In addition to these mixed findings, there is another reason why calls for solidarity may not have worked during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 crisis. After all, the call to help each other largely opposed actual lockdown measures at that time. People were implored to limit their social interactions as much as possible. Informal helping, that is helping people that do not live in the same household without the coordination of formal organizations (Einolf et al. Citation2016), generally relies on face-to-face social interactions (Koolen-Maas and De Wit Citation2022). Thus, regular forms of informal help, such as helping with housework, providing transport, and watching children were seriously discouraged.

Studies that investigated the impact of the first lockdown of the COVID-19 crisis present an ambiguous picture regarding changes in informal help. Some suggest an increase (Engbersen et al. Citation2020; Bertogg and Koos Citation2021b), whereas others indicate that informal helping decreased (Katz and Feit Citation2021), or that people simply expected less help from each other (Borkowska and Laurence Citation2020). Hence, the current study aims to clarify some of this ambiguity by not only describing how informal helping changed during the lockdown in the Netherlands, but also by theorizing which groups are expected to report a larger or smaller change.

To theorize on the differences between groups, we rely on a general theoretical framework that explains informal helping. This framework distinguishes between resources, motivations, and opportunities to help, sometimes also referred to as human, cultural and social capital (Brady et al. Citation1995; Verba et al. Citation1995; Wilson and Musick Citation1997; Lee and Brudney Citation2012; Lim and Laurence Citation2015). We expect that those with fewer resources during (time) or at the start of the lockdown (health), fewer motivations (concerns about COVID-19 and solidarity) or opportunities (social contact) were more likely to reduce their informal helping, whereas people with more resources, motivations or opportunities were more likely to increase their help.

By examining exactly which people changed their informal helping during the lockdown and how, we provide new insights into the conditions under which informal helping changes. This improves on earlier research that largely disregarded the impact of major societal changes (for an exception, see Lim and Laurence (Citation2015)). Our focus on changes in informal helping allows us to test to what extent the aforementioned general theoretical framework is suitable to predict changes in informal helping and to differentiate reactions to crises, such as a lockdown. Determining which people reduced their informal helping (more strongly) may inform governments which groups and communities have lacked help during the COVID-19 lockdown. This supports local governments and volunteering organizations to assess where formal help may be required during future lockdowns or crises.

Hence, this study answers the following research questions: How did informal helping change during the first lockdown in the Netherlands? To what extent did this change depend on individuals’ resources, motivation, and opportunities for helping?

To answer these questions, we used a unique panel dataset that combines survey data collected before the corona crisis in the Netherlands (either in February 2019 (51%) or in 2020 (49%)), and survey data collected shortly after the first lockdown (July 2020), creating a pre–post comparison study. The data thus include questions about informal helping before (wave 1) and during the lockdown (wave 2). To analyze these data, we performed fixed-effects regression models in which we interacted time with measures of people’s resources, motivation, and opportunities.

Dutch context

We here shortly discuss the COVID-19 situation in the Netherlands until the end of the data collection (end of July 2020) to place our expectations in perspective. As discussed in the introduction, the Netherlands went into lockdown on 15 March 2020. This was done after the introduction and rapid spread of the virus since the end of February. Lockdown measures entailed that most public places (including but not limited to schools, restaurants, and gyms) were closed and that occupations that required contact between people (e.g. hairdressers, dentists, and physical therapists) were not allowed to be practiced. Childcare facilities were only available for workers in essential jobs. People were told to stay at home as much as possible, keep 1.5 meters distance between members of different households and were not allowed to convene in public. Working from home was strongly encouraged, but not mandatory. Masking was not advised at all.

These measures were slowly relaxed from May 11th onwards. First, primary schools partially reopened, and contact occupations were allowed again. From June 1st, most public spaces reopened with restrictions on the number of visitors and the distance between them. The same applied to groups assembling in public. On this date, widespread testing became available as well. From July 1st, events, such as fairs and sports games, were allowed again, with similar restrictions on the number of visitors and the distance between them.

During the lockdown in the Netherlands, people had to adjust their daily lives, which likely increased the demand for informal help. For example, not all non-essential workers were allowed to work from home. In combination with the shutdown of childcare facilities, this likely resulted in an increased demand for help with childcare. People indeed reported that they received more help during the lockdown than before (Engbersen et al. Citation2020).

Theory and hypotheses

Resources, motivations, and opportunities are the three main antecedents of helping according to the general theoretical framework that is regularly used to explain helping behavior such as formal volunteering and informal helping (Brady et al. Citation1995; Verba et al. Citation1995; Wilson and Musick Citation1997; Lee and Brudney Citation2012). According to this framework, resources refer to the knowledge, financial means and physical and mental capabilities that foster helping. Particularly available time and health have been found to be consistent predictors of people’s informal helping (Wilson and Musick Citation1997; Egerton and Mullan Citation2008; Plagnol and Huppert Citation2009). Motivations refer to feelings and values that motivate a person to provide help. Examples of important motivations for informal helping are valuing helpfulness and religiosity (Finkelstein and Brannick Citation2007; Van Tienen et al. Citation2011). Opportunities refer to the number of situations a person faces in which help can be provided. In prior research, it has been assumed that the more people a person is associated with, the more likely it is that they face an opportunity to help (Wilson and Musick Citation1997; Lee and Brudney Citation2012; Wang et al. Citation2017).

With respect to the first lockdown in the Netherlands, we could expect both an increase and a decrease in informal helping based on this framework. As studies have documented, crises, such as a lockdown, can motivate people to take up helping. For example, people who provided help during terrorist attacks, natural disasters and economic crises in the US seem to be motivated by a sense of shared fate and solidarity (Chambré Citation2020). Crises also often result in an increased demand for help, which offers people more helping opportunities (Lim and Laurence Citation2015). These arguments are in line with the findings by Bertogg and Koos (Citation2022) about the COVID-19 crisis in Germany.

Yet, a decline can be expected as well. First, crises may leave individuals with fewer financial resources and less mental space for helping (Lim and Laurence Citation2015). Second, in this specific COVID-19 crisis, motivation to help may have declined, despite people’s feelings of solidarity. After all, people were concerned about contracting the virus and they likely avoided situations that required interactions with others in person, including informal helping. Additionally, people may have had fewer opportunities for helping if they wanted to adhere to social distancing measures or because help requesters felt uncomfortable receiving help. Because of the pressing nature of the COVID-19 crisis, we believe these COVID-specific arguments to be decisive. Hence, we expect that in general informal helping declined during the first lockdown of the corona crisis in the Netherlands (H1).

Prior studies suggest that not everyone experiences the same change in helping behavior during a crisis (e.g. Lim and Laurence Citation2015; Rotolo et al. Citation2015; Cameron Citation2021). We assume that this applies to the first lockdown of the COVID-19 crisis as well. We will use the framework of resources, motivations, and opportunities to derive expectations on which people decreased their informal help more (or less) strongly. The resources we discuss below refer to stable characteristics that did not change before and during the lockdown (e.g. having young children or age) as well as to characteristics specifically related to lockdown experiences (e.g. working from home). The motivations and opportunities we discuss all refer to lockdown experiences (e.g. worries over contracting COVID-19 or changing contact with neighbors). Yet, we should note that in the end all our hypotheses refer to differences between people who differ in resources, motivations, or opportunities in their individual change in informal helping.

Resources

We consider five factors that refer to a person’s resources to provide informal help, namely health, age, being a parent of young children, losing work and working from home.Footnote1 First, both people with poor health and people over 65 faced more severe consequences of contracting COVID-19 (Zheng et al. Citation2020). Because they would benefit most from avoiding in-person contact, it is expected that people with poor health and people over the age of 65 adhered more strongly to the lockdown measures than others. Hence, their availability for informal helping declined relatively strongly. We expect that people with poor health (H2) and people over the age of 65 (H3) reduced their informal helping more strongly during the first lockdown than others.

Second, the first COVID-19 lockdown may have especially affected the available time of parents of young children. During the lockdown, day care centers closed, and schools were forced to educate pupils online. As a result of these measures, parents of (pre-) primary school children, substantially increased time spent on childcare (Sevilla and Smith Citation2020; Lee and Tipoe Citation2021; Van Kesteren et al. Citation2021), and on home schooling (Adams-Prassl et al. Citation2020; Huls et al. Citation2022). Assuming that requirements of paid work and housework remained rather similar, less time remained available for informal helping during the first lockdown (Yerkes et al. Citation2020; Huls et al. Citation2022). As a result, it can be expected that people with young children reduced their informal helping more strongly during the first lockdown than others (H4).

The opposite may have happened to people who lost their job or could not work during the first lockdown. Various theories cover the relationship between becoming unemployed and helping others (e.g. Musick and Wilson Citation2008; Piatak Citation2016). These theories predict both a positive and negative relationship, which is also reflected in prior empirical research (for an overview see Musick and Wilson Citation2008). The mechanisms that are suggested to underlie a negative relationship between unemployment and informal helping include a reduction of social integration, a lack of self-esteem due to stigmas on unemployment (Piatak Citation2016) and a lack of financial and mental resources (Lim and Laurence Citation2015). Mechanisms, such as an increase in available time (Piatak Citation2016) and a coping mechanism for dealing with unemployment (Musick and Wilson Citation2008), are expected to result in a positive relationship.

Here, we focus specifically on individuals who could not work during the first lockdown. Because everyone had to stay at home during this time, the stigma on unemployment may have been smaller. Additionally, not all individuals who could not work lost their job or their income, likely reducing the impact of lack of financial resources and reduction in social integration. On the other hand, these individuals did have more time available and since the options for spending this time were limited, informal helping was likely an attractive alternative to work activities. Hence, it is expected that people who lost work during the lockdown reduced their informal helping less strongly during the first lockdown than others (H5).

People who worked from home may also have experienced more available time during the first lockdown. Working from home saves commuting time that could be spent on informal helping. Moreover, working from home allows for more flexibility; one can alternate paid work tasks with other tasks, such as housework, childcare, or informal help. Therefore, we expect that people who worked from home reduced their informal helping less strongly during the first lockdown than others (H6).

Motivations

We consider three factors that may have affected a person’s motivation to provide informal help, namely concerns about contracting COVID-19, concerns about others contracting COVID-19 and changes in their feelings of solidarity. First, individuals who were concerned about contracting COVID-19 may have developed a less positive or even negative attitude towards helping others. Informal helping likely required them to be in close contact with others, potentially exposing themselves to the risk to get infected. As a result, they may have felt more hesitant to provide informal help than people who were less concerned. Thus, it can be expected that the more concerned people were about contracting COVID-19, the more strongly they reduced their informal helping during the first lockdown (H7).

The opposite may apply to people who were concerned about others contracting COVID-19. These individuals did not necessarily worry about their own well-being, but about that of others. On the one hand, it could be expected that these people were more hesitant to provide help to those they worried about, as it would increase the risk of exposing them to the virus. On the other hand, people who were concerned about others contracting COVID-19 could also have been more motivated to help these people; they more often wanted to support people they considered at risk by providing informal help (Verbakel et al. Citation2021). Moreover, informal helping can replace services by third parties, thereby limiting social interactions of the person helped and reducing their risk of exposure to COVID-19. Following this line of reasoning, we expect that the more concerned people were about others contracting COVID-19, the less strongly they reduced their informal helping during the first lockdown (H8).

People whose feelings of solidarity increased during the lockdown may also have been more motivated to provide informal help. Prior research has shown that people generally experience higher levels of solidarity during crises (Lau et al. Citation2008; Putnam Citation2002, yet for an opposite finding about the COVID-19 crisis, see Borkowska and Laurence Citation2020). However, some people may have experienced larger increases in feelings of solidarity than others. It is likely that people who felt more connected with others also developed a more positive attitude towards helping and thus provided more help. Hence, it can be expected that the more people’s feelings of solidarity increased, the less strongly they reduced their informal helping during the first lockdown (H9).

Opportunities

Finally, we consider a person’s opportunities to provide informal help, namely the changes in the number of social contacts during the first lockdown. Although government measures urged people to avoid social contact as much as possible, not everyone did this to the same extent (Latsuzbaia et al. Citation2020; Safi et al. Citation2020; Bertogg and Koos Citation2021a). Moreover, some people replaced in-person social contact with safe online social contact (Safi et al. Citation2020). As a result, people widely varied in how they changed their social behaviors; some people dramatically reduced their total social contacts, whereas others increased their total social contacts (Bertogg and Koos Citation2021a), likely through online communication (Safi et al. Citation2020).

From the general theoretical framework on volunteering, it follows that people with more social contacts are more often asked for help (Wang et al. Citation2017). Applied to the lockdown period, we argue that, despite a general hesitancy to ask for help, people with more social contacts during the lockdown than before were more likely to be asked for help than those with similar or fewer social contacts during the first lockdown. Hence, it can be expected that people who increased their social contact reduced their informal helping less than people who did not change (H10a) and that people who decreased their social contact during the first lockdown reduced their informal helping more than people who did not change (H10b).

shows an overview of all our expectations. Although our hypotheses refer to informal helping in general, we will test them for informally helping relatives, friends, and neighbors separately. Theories on social distance and social proximity suggest that people approach helping kin and non-kin differently (Cialdini et al. Citation1997; Curry et al. Citation2013). Following prior research (e.g. Lim and Laurence Citation2015; Einolf et al. Citation2016; Ramaekers et al. Citation2022), we thus consider relatives as a distinct recipient group. Additionally, we distinguish between friends and neighbors within the non-kin category, because barriers for helping neighbors were likely lower during the lockdown than they were for helping friends, as neighbors were spatially closer to people’s homes.

Table 1. Overview of expectations regarding the influence of resources, motivations and opportunities.

Data

To test our expectations, we used data from the Social and Cultural Developments in the Netherlands (SOCON) COVID-19 Panel Survey (Ramaekers et al. Citation2021).Footnote2 The SOCON data consist of two waves; one collected before the first lockdown in the Netherlands and one shortly after the first lockdown, creating a pre–post comparison study. The first SOCON wave was collected in two parts with two independent samples but with virtually identical questionnaires. One part was collected in February 2019 (51.4%) and the other part in February 2020 (48.6%), either through an internet survey or phone interview. In total, 2,762 respondents participated in the first wave. Of the first wave respondents, 1320 indicated they would be willing to participate in a follow-up study by e-mail and registered contact information.Footnote3 In July 2020, these respondents were approached by e-mail for a COVID-19 themed follow-up SOCON study. 663 respondents (50.2%) participated in this second wave (53% female; age = 20–72).Footnote4 People with lower educational attainment were overrepresented among those who dropped out (Ramaekers et al. Citation2021), exacerbating the underrepresentation of lower educated people from the first wave (Savelkoul et al. Citation2019; Savelkoul et al. Citation2020). Since we were interested in the changes between waves, we only used respondents that participated in both SOCON waves.

We performed multiple imputation in STATA, using chained equations (mice), to substitute missing values (N = 64; 9.7%) regarding contact with friends and neighbors, COVID-19-related concerns about friends and neighbors, and feelings of solidarity.Footnote5 Respondents with remaining missing values and those with missing values on other (predictor) variables were excluded (N = 73; 11%). Our final sample consisted of (at least) 522 respondents, depending on the number of missing values on the dependent variable. Respondents with an invalid score on a certain dependent variable were removed for that particular analysis but were included in the other analyses.

Dependent variables

To assess changes in informal helping, we measured informal helping in both wave 1 and wave 2. Respondents were asked how often they provided help to relatives, friends, and neighbors respectively. Several examples of informal help were given, such as chores, childcare, grocery shopping, lending things and giving advice. In the first wave, respondents were asked about the entire previous year. In the second wave, respondents were asked about their helping during the lockdown period (15th of March until 1st of June). Response options were identical and were recoded to the number of times a respondent helped per month; ‘every day’ (30), ‘multiple times a week’ (16), ‘once a week’ (4), ‘multiples times a month’ (3), ‘once a month’ (1), ‘less often’ (0.5), ‘never’ (0). Respondents could also answer they did not know; 24 (3.6%), 41 (6.2%), and 34 (5.1%) respondents had a missing score on informal helping of relatives, friends, and neighbors respectively in the first wave, and 57 (8.6%), 76 (11.5%) and 66 (10.0%) had a missing score on informal helping of relatives, friends, and neighbors respectively in the second wave.

Independent variables

All independent variables were time constant and measured in the second wave. Poor health was measured by asking respondents how they would describe their health (1 = excellent to 5 = poor). The answers were recoded into a dichotomous variable measuring whether respondents described their health as poor (not very good or poor) (1) or not (good to excellent) (0). To measure being over 65 years old, we constructed a dichotomous variable of respondents up to 64 years old (0) and being 65 years or older (1). We determined whether respondents were parents of young children with two questions. First, respondents were asked whether they had children living in their home. People who did not have children living with them were coded to be no parents of young children (0). Those who had children living with them were asked in which stage of education their children were. Respondents could give multiple answers. Respondents who had children that were too young to go to school or in primary education were considered as parents of young children (1). Respondents who reported only to have older children were coded to be no parents of young children (0).

Having lost work was measured by asking respondents about their work situation before and during the lockdown. Their work situation before the lockdown could be either employment, self-employment or not working. If they were not working, they could not lose work and were thus not considered as having lost work (0). Also, (self-) employed respondents who did not experience any change or could do their work from home were considered as not having lost work during the lockdown (0). (Self-) employed respondents who could not do any work or lost their (self-)employment were considered as having lost work (1). Working from home was measured with a question asking how often respondents worked from home (1 = always, 4 = never). Response options were reversed; a higher score thus represented working from home more often. Our hypothesis regarding working from home relies on the argument that those working from home had more available time and flexibility. We assume that non-employed respondents share these experiences, which is why we assigned them the highest score on the working from home variable.

Concerns about COVID-19 for own well-being were measured by asking respondents how concerned they were that they would contract the virus and how concerned they were that they would become seriously ill when infected (1 = not worried at all to 5 = very much worried). The two items were combined by calculating the average score. To measure concerns about COVID-19 for others’ well-being, respondents were asked the same questions for concerns about relatives, friends, and neighbors. We combined scores for each target group by calculating the average score. This resulted in three measures: concerns for relatives, concerns for friends and concerns for neighbors. Increased feelings of solidarity towards other people in the Netherlands were measured by asking respondents to what extent their feelings about being connected to other people in the Netherlands had changed during the first lockdown (1 = a lot more [connected] to 5 = a lot less [connected]). Scores were reversed, meaning that a higher score represented a larger increase in feelings of solidarity.

Respondents were also asked how they changed the intensity of social contact with relatives, friends, and neighbors during the first lockdown (1 = a lot more, 5 = a lot less). Social contact included both online and offline contact. For each group, scores were divided in three categories: ‘decrease in contact’ (0), ‘no change in contact’ (1) and ‘increase in contact’ (2). Respondents who answered ‘not applicable’ were regarded as ‘no change in contact’.

We controlled for gender (0 = female, 1 = male), education in years (6 = no education completed to 18 = PhD), born outside of the Netherlands (0 = no, 1 = yes), year participated in SOCON-wave 1 (0 = 2019, 1 = 2020)Footnote6 and baseline informal helping (i.e. score in wave 1). The latter is done to account for bottom and ceiling effects. presents the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (Total N = 661).

Analytical strategy

For descriptive purposes, we first present average scores for informal helping for the three recipient groups. Next, we calculated within-person change in informal helping during the first lockdown in the Netherlands by comparing scores on informal helping in the first wave to scores on informal helping in the second wave within individuals. We report the percentage of people that reduced, increased, or did not change their informal helping during the lockdown. To present a more representative picture of the Netherlands during this period, we weighted the data to the national distribution for education and age for this description (Statistics Netherlands Citation2021); we divided the percentage based on the national statistic by the percentage in our data. Hence, underrepresented groups in our data were given more weight that the overrepresented groups. We did not include gender in our re-weighting because the sample was representative for the Dutch population in that regard (Ramaekers et al. Citation2021).

To test our hypotheses, we transformed the data from a wide format to a long format. This means that we included two observations for each respondent, one for each wave of data. We included a dummy variable that indicated whether the observation was done in the first or second wave. Because independent variables were measured once, they did not differ between the two observations of a respondent. The dependent variable was measured twice, which is why these scores did differ over a respondent’s observations.

We performed fixed-effects panel regression models (Allison Citation2009) to control for all unobserved heterogeneity between persons, thus analyzing within-person change only. The analyses were performed in STATA. The frequency of helping served as the dependent variable.Footnote7 We first estimated models that only include time (0 = wave 1, 1 = wave 2) showing the average change in helping (shown in Appendix A). Because the goal of the paper is to test to what extent this change in informal helping was different between groups, we interacted this time variable with individuals’ resources, motivations, and opportunities. The same was done for the control variables. Note that no ‘main effects’ of the independent and control variables are reported, as they are time invariant. We ran separate regression models for help given to relatives, to friends, and to neighbors.

Results

Descriptive results

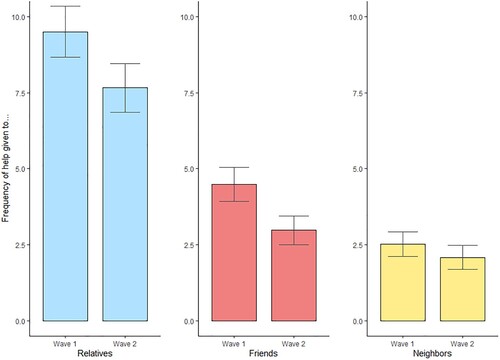

Informal helping before (i.e. wave 1) and during the lockdown (i.e. wave 2) were positively correlated: 0.33 for helping relatives, 0.25 for helping friends, and 0.40 for helping neighbors. This implies stability in helping behavior, but at the same time suggests that many respondents have changed the amount of informal helping. This is also visible in , which reports on average levels of informal helping in wave 1 and wave 2. It shows that, for each recipient group, levels of informal helping depend on the level of help provided before the lockdown. Yet, initial levels of informal helping were clearly higher than the levels during the lockdown. This suggests a decline in the amount of informal helping. However, for some people change will have been in the direction of less helping, while for others it may have been in the direction of more helping.

Figure 1. Frequency of help given to relatives, friends and neighbors before (wave 1) and during the lockdown (wave 2).

Note: 95% confidence intervals; weighed data. Source: SOCON COVID-19 Panel Study.

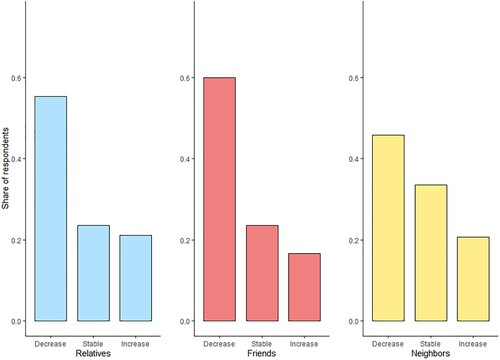

shows that the majority of respondents reduced their informal helping during the lockdown. Approximately 54% of all respondents reduced their informal help given to relatives during the lockdown, whereas 25.1% remained stable and 20.9% increased their informal helping to relatives. This pattern is observed for informally helping friends as well: 58.8% provided help less frequently during the lockdown than before, whereas 24.1% remained stable and 17.1% increased their informal helping. A smaller share reduced their informal helping for neighbors, yet the group that reduced their help is still the largest (46.9%). This is interesting as shows that informally helping neighbors is less prevalent than helping relatives and friends. Furthermore, 32.7% maintained their informal help given to neighbors, whereas 20.3% increased it.

Multivariate results

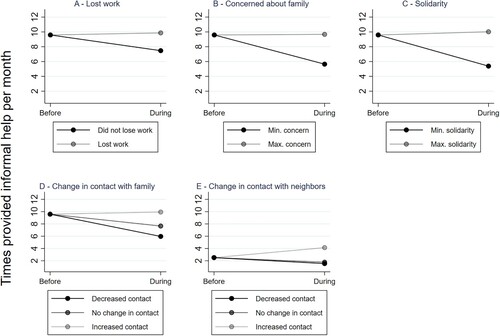

Table A.1 (Appendix A) reports the results of the fixed effects analyses that only include time. In accordance with our descriptive results, these analyses show a negative effect of time, indicating that informal helping for all three groups declined during the lockdown. This is in line with hypothesis 1, which predicted a decline in informal helping. reports the results of the fixed effects analyses including all interactions (with time). With respect to resources for helping, we only found a statistically significant interaction between having lost work during the lockdown and the change in informally helping relatives (Model 1: b = 2.397, p = 0.040). This effect is in line with our expectation that people who lost work during the lockdown reduced their informal helping less strongly. visualizes the significant differences between groups from as marginal effects. Panel A shows that people who did not lose work during the lockdown reduced their informal help to relatives from approximately 10 times per month to 7.5 times per month. People who lost work did not decrease their informal helping for relatives but slightly increased it instead. We did not find evidence for an impact of the other types of resources on the change in helping relatives, nor for an impact of any of the resources on changes in helping non-kin.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of determinants with significant effects in fixed effects regression analyses.

Note 1: Panels A to D report the impact on informally helping relatives, panel E reports the impact on informally helping neighbors. Note 2: Confidence intervals not reported due to bias in degrees of freedom used in case of multiple imputation. Source: SOCON COVID-19 Panel Study.

Table 3. B-coefficients and standard errors of fixed effects regression analysis.

Results regarding the motivations for providing informal help show that strong concerns about relatives’ well-being significantly affected the change in informal help to relatives. The coefficient of the interaction term (b = 1.007, p = 0.048) was in line with what we expected, namely that stronger concerns about others would lower the tendency of people to reduce their helping behavior during the lockdown. The same applies to increased feelings of solidarity (b = 1.160, p = 0.047); people who felt more strongly connected to other Dutch people decreased their informal helping for relatives less during the lockdown, in line with our expectation. Both effects are visualized in (panels B and C). These panels show that people who felt least concerned about relatives and experienced the largest decrease in solidarity reduced their informal helping for relatives from approximately 10 times per month to less than 6 times per month. People who experienced the most concern about relatives were stable in their helping behavior, whereas those who experienced the most solidarity even slightly increased their informal helping.

Finally, reports a significant impact of the opportunity structure on changes in informal helping. People who increased the amount of contact they had with relatives reduced the informal help they gave to relatives less during the lockdown than those whose contacts with relatives did not change (model 1: b = 2.281, p = 0.021). A similar pattern is visible for informally helping neighbors (model 3: b = 2.370, p = 0.000). As shows, both people who did not change contact with relatives or neighbors and those who reduced contact provided less help during the lockdown. Those who increased contact with relatives and neighbors remained relatively stable (relatives) or increased their informal helping for this group as well (neighbors; from 2.5 times to 4 times per month). In sum, the reduction in help provided to relatives and neighbors during the lockdown was smaller for people who increased their contact frequency with them.

Robustness analyses

We performed various additional analyses to check the robustness of our results. First, we checked whether we were possibly overcontrolling by including all three factors (resources, motivations, and opportunities) simultaneously. Analyzing the factors separately produced very similar results (Appendix B). The only difference was that there was no significant result of concerns about relatives without controlling for resources and opportunities, and that concerns about one’s own well-being exacerbated the decline in informally helping friends.

Second, we considered to what extent our results on the change in helping between waves 1 and 2 were in line with respondents’ perceptions of the change in their helping (Appendix C).Footnote8 For these analyses, we used respondent information collected in wave 2 on perceived changes in informal helping behavior during the first lockdown. The analyses did not show an effect of having lost work during the lockdown on the change in informally helping relatives, but the other factors we found to be significant in our fixed effects analyses were confirmed. Additionally, the analyses revealed several significant associations that were not present in the fixed effects analyses. Regarding resources, we found for example that people older than 65 were more likely to believe they decreased their informal help (to all groups) than others. We also found that the stronger a person’s sense of solidarity was during the lockdown, the lower the likelihood that they believed they reduced their help to any of the groups. Finally, with respect to opportunities, we found that those who increased contact with friends (and not only with relatives and neighbors) had a higher likelihood to believe that they increased informal help towards these friends. In addition, for all three groups, we found that those with decreased contact had a higher likelihood to believe to have decreased informal help towards them. Thus, the perceptions people have about changes in their informal helping behavior more strongly followed patterns in resources, motivations and, especially, opportunities than their reported behavioral changes in informal helping.

Discussion and conclusion

During the first lockdown of the corona crisis in the Netherlands, government officials and civil society actors called for solidarity and urged people to help each other deal with its consequences. At the same time, lockdown measures discouraged social interactions, which made providing help more difficult. Hence, this study examined how informal helping changed during the lockdown and to what extent this depended on the resources, motivations and opportunities people had for helping during the lockdown. We first expected a general decline in informal helping. Using data from the SOCON COVID-19 Panel Study, we indeed found that the majority of the Dutch reduced their informal help given to relatives (54%), friends (58.8%) and neighbors (46.9%) during the lockdown. We thus conclude that governmental calls for solidarity, in this particular crisis, did not result in a widespread increase in informal helping. This study is thus in line with the notion that social cohesion declined during the first lockdown, which supports findings from studies on feelings of solidarity (Borkowska and Laurence Citation2020), informal helping (Katz and Feit Citation2021) and formal volunteering (Dederichs Citation2022; Mak and Fancourt Citation2022). It thereby opposes earlier studies that report increases in solidarity behaviors such as neighborhood involvement (Jones et al. Citation2020) and informal support (Carlsen et al. Citation2021; Bertogg and Koos Citation2022).

The general tendency to reduce informal helping was however (partly) counterbalanced by several compensating factors. We hypothesized and found evidence for compensating effects of resources, motivations, and opportunities. The decline in informal helping of relatives was smaller among those who lost work during the lockdown compared to those who remained (self-)employed, probably because they had more (flexible) time available; among those who had stronger concerns about their relatives’ well-being and experienced an increased in feelings of solidarity with other Dutch people, because they presumably felt more strongly motivated to help; and among those who increased contact with their relatives, because they likely had more opportunities to help. The compensating effect of opportunities also emerged with respect to informal help to neighbors: the decline in help was lower if social interactions with neighbors increased.

This study’s results underscore the usefulness of a theoretical framework that considers resources, motivations, and opportunities as determinants of informal helping in two ways. First, our results corroborate existing research on informal helping. We extended the evidence that not in all crises informal helping rises (Lim and Laurence Citation2015; Cameron Citation2021). In line with research on informal care (Verbakel et al. Citation2021), we found that especially concerns about relatives’ well-being result in a smaller decline in informal help given to them. Finally, our results on social contacts mirrored prior studies reporting that opportunities are important for informal helping (Lee and Brudney Citation2012; Wang et al. Citation2017). Second, our study suggests that changes in resources, motivations and opportunities to some extent explain changes in informal helping. Our study therefore shows that the general theoretical framework of resources, motivations and opportunities is not only applicable to understand between-person differences in informal helping, but also within-person change in informal helping.

It is important to note that not all indicators that we tested appeared to significantly affect change in informal helping. This was especially the case with respect to various resources. This may seem unsurprising because prior research has not reported a strong relationship between resources and informal helping (Einolf et al. Citation2016; Wang Citation2021). Yet, we focused specifically on resources, such as health, available time, and flexibility to spend it, that have been linked to informal helping (e.g. Wilson and Musick Citation1997; Egerton and Mullan Citation2008). Although prior research suggest that they are predictors of differences between people in their informal helping, our study indicates that they have less explanatory power regarding changes in informal helping. An exception is the finding that people who became non-working during the lockdown reduced their informal helping less. Given the lack of support for other indicators of available time, such as having young children or working from home, it is likely that people who could not work used informal helping as a coping strategy (Musick and Wilson Citation2008). That is, they provided help to relatives to deal with the fact that they lost work and thereby created new self-fulfillment.

Another consideration is that our theoretical framework seemed particularly helpful to understand change in helping relatives, but less so with respect to helping friends and neighbors. We know from prior research that people are more willing to give help to relatives (Kahn et al. Citation2011; Curry et al. Citation2013) and that motivations, such as expecting help in return (Stewart-Williams Citation2007; Curry et al. Citation2013), play a smaller role in the decision to help them. This suggest that help to family members is given regardless of one’s exact resources, (personal) motivations or opportunities. Our findings contrast these studies, as changes in informally helping relatives seemed more strongly driven by resources, motivations, and opportunities than changes in informally helping friends and neighbors. We cannot determine exactly why this is the case. Yet, it is possible that the lower importance ascribed to informally helping friends and neighbors has led to more uniform effects. When it became too difficult to maintain all types of helping behavior, people may have prioritized to maintain help provided to relatives over help provided to non-kin. However, given the lockdown measures and according stress, only those with the most resources, motivations and opportunities succeeded in this. Future research should delve deeper into the differences between helpers of relatives, friends, and neighbors.

Certainly, our study is not without drawbacks. A first limitation concerns the interpretation of the associations for intensity of social contacts. These estimates should be interpreted cautiously because causality is rather unclear for this aspect. It is possible that those who increased their social contacts during the lockdown indeed gave more informal help as a result of this increase (as theorized). However, it is also possible that the reported informal help was a part of this increased social contact, or that social contact increased as a result of the demand for informal help. Hence, with the current data, we only conclude that changes in informal helping and changes in social contact were interrelated, but do not draw conclusions on the direction of the influence. Future research should investigate this relationship longitudinally to better disentangle the causality structure.

A second limitation concerns the sample size. Due to attrition in the SOCON panel the sample was relatively small and less representative, especially regarding age and education. Fortunately, we do not believe that this has biased the effects of resources, motivations, and opportunities for helping, because we do not expect these effects to differ largely by age or education. However, in our study, effects could not be estimated with great statistical power. Hence, it is important that future research on the changes in informal helping is based on larger samples, so differences over time and between groups can be better distinguished.

Future research preferably also extends the scope of this research topic to the demand for informal help in one’s core social network. The current study only considers factors that may have affected people’s resources, motivations, and opportunities to provide informal help. So, it did not consider that some network members may have needed more help during the lockdown, as shown by Bertogg and Koos (Citation2022). We consider the need for help in one’s network as an often-overlooked aspect in the informal helping literature, and our data unfortunately could not shed light on this issue. Hence, we invite future research to follow the study by Bertogg and Koos (Citation2022) and pay more attention to the demand side of informal helping, particularly whether demand side changes affect the level of help provided.

Our results show a decrease in informal help during the first lockdown in the Netherlands. However, the lockdown also had some silver linings. First, informal helping declined less among those who lost work during the lockdown, suggesting that they may have used their extra time for the greater good. Second, the lockdown created opportunities for (re)connecting with neighbors increasing cohesion in local communities. Our study suggests that this (re)connection is not limited to social contact but spills over to giving informal help. That is likely why informal helping decreased less among neighbors than among family and friends. These results underscore that increased availability in combination with increased contact with others fosters informal helping, even in a pandemic.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (640.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the four anonymous reviewers of our paper for their valuable comments. Their feedback and suggestions have substantially improved the paper. Ramaekers wrote the main part of the manuscript and conducted the analyses. Verbakel and Kraaykamp substantially contributed to the manuscript, The authors jointly developed the idea and the design for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlou J. M. Ramaekers

Marlou Ramaekers is a PhD candidate at the Sociology department at Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research concerns the sustainability of informal helping, or direct person-to-person helping without interference of formal organizations. She is particularly interested in the role that families and local communities play in informal helping.

Ellen Verbakel

Ellen Verbakel is a full professor General and Theoretical Sociology at Radboud University Nijmegen. She is particularly interested in family, work, and well-being, with a special focus on partner relationships, partner effects, and informal care provision.

Gerbert Kraaykamp

Gerbert Kraaykamp is a full professor Empirical Sociology at Radboud University Nijmegen. His main research interests lie with issues of social inequality and intergenerational transmission. He has published on this topic widely in international journals.

Notes

1 We do not consider income as a resource in this study. Although it is often suggested as a predictor of helping behavior (especially formal volunteering), empirical evidence for informal helping is ambiguous (Einolf et al. Citation2016; Wang 2021). Moreover, the theoretical explanation of the association between income and informal helping is unclear and data regarding income was only collected in wave 1 and contains a substantial amount of missing. Given the small sample and the theoretical unclarity, we decided to exclude it from our models.

2 Social and Cultural Developments in the Netherlands (SOCON) is a collection of representative cross-sectional datasets collected from 1979 to 2020 among the Dutch population. For more information, see https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:210154. Replication files are available at Open Science Framework (OSF): doi:10.17605/OSF.IO.

3 Approximately 250 respondents showed interest in participation by providing their phone number. Yet, because of financial reasons, it was not possible to contact these respondents for a follow-up in July 2020.

4 In our sample, 53.9% of the respondents first participated in 2019 and 46.1% of the respondents first participated in 2020.

5 The variables used in the imputation procedure were: having poor health, being over 65, having young children, losing work during the lockdown, working from home, being concerned about COVID-19 for one’s own well-being, being concerned about COVID-19 for relatives’ well-being, change in contact with family members, gender, educational attainment in years, year participated in wave 1, subjective well-being, satisfaction with COVID measures, having a partner, having children in the household, wanting to vote if elections were today, being religious, political interest, social trust, age, number of COVID cases in municipality, number of COVID hospitalizations in municipality, number of COVID deaths in municipality, being a migrant and income. The method of imputation was predictive mean score matching. To achieve reliable results, we performed 5 imputations, for which we constrained the number of iterations to 10. For the analyses, we pooled all 5 imputations. We also performed our analyses without imputations (see Appendix D). We found identical effects regarding resources and opportunities. We did not find significant effects of motivations (concerns for relatives and feelings of solidarity).

6 In addition to controlling for the year that a respondent participated in the first wave, we also checked to what extent the effects were different for the 2019 and 2020 cohort. These analyses (Appendix E) showed that in the 2020 cohort, the effects of concerns about relatives and feelings of solidarity were not present. Given that these referred to lockdown-specific experiences, this likely indicates a difference in selection into the second wave between the 2019 and the 2020 cohort. Reversely, in the 2019 cohort, the effects of contact with relatives and losing work were not present. Yet, because there was more time between waves, it is possible that these differences can be attributed to other events that occurred between the two measurements.

7 We treated our dependent variable as an interval variable. To ensure that this decision did not affect our results, we performed fixed effects ordered logit regression (Appendix F). The results of these analyses were very similar in terms of opportunities to the fixed effects linear regression results. Losing work, concern about relatives and feelings of solidarity had similar effects on informally helping relatives but were not significant. This is likely because ordered logit models require more degrees of freedom, reducing the power to find significant estimates. Given our small sample size, we thus prefer the linear model over the ordered logit models. Additionally, we log transformed our dependent variable and performed our analyses again (Appendix G). This did not lead to substantially different conclusions.

8 The perceived change in informal helping was measured by asking respondents whether they had changed the amount of informal help they provided to relatives, friends, and neighbors during the first lockdown (15 March to 1 June), citing the same examples as was done for the questions on the frequency of informal helping. Response options were ‘a lot more help’ (1), ‘a bit more help’ (2), ‘about the same amount of help’ (3), ‘a bit less help’ (4) and ‘a lot less help’ (5). These options were recoded into three categories, namely ‘decrease in help’, ‘no change in help’ and ‘increase in help’. Missing scores amounted to 47 (7.1%; relatives), 73 (11.0%; friends) and 61 (9.2%; neighbors). To analyze these data, we ran multinomial logistic regression analyses with ‘no change in help’ as the reference category.

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M. and Rauh, C. (2020) ‘Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: evidence from real time surveys’, Journal of Public Economics 189: 104245.

- Allison, P. D. (2009) Fixed Effects Regression Models, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Bertogg, A. and Koos, S. (2021a) Changes of Social Networks During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Who Is Affected and What Are Its Consequences for Psychological Strain. Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’. University of Konstanz.

- Bertogg, A. and Koos, S. (2021b) ‘Socio-economic position and local solidarity in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of informal helping arrangements in Germany’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 74: 100612.

- Bertogg, A. and Koos, S. (2022) ‘Who received informal social support during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Germany, and who did not? The role of social networks, life course and pandemic-specific risks’, Social Indicators Research 163: 585–607.

- Borkowska, M. and Laurence, J. (2020) ‘Coming together or coming apart? Changes in social cohesion during the COVID-19 pandemic in England’, European Societies 23: 618–36.

- Brady, H. E., Verba, S. and Scholzman, K. L. (1995) ‘Beyond SES: a resource model of political participation’, American Political Science Review 89: 271–94.

- Cameron, S. (2021) ‘Civic engagement in times of economic crisis: cross-national comparative study of voluntary association membership’, European Political Science Review 13: 265–83.

- Carlsen, H. B., Toubøl, J. and Brinckner, B. (2021) ‘On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: the impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support’, European Societies 23: S122–S140.

- Chambré, S. M. (2020) ‘Has volunteering changed in the United States? Trends, styles and motivations in historical perspective’, Social Science Review 94: 373–421.

- Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C. and Neuberg, S. L. (1997) ‘Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: when one into one equals oneness’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 481–94.

- Curry, O., Roberts, S. G. B. and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2013) ‘Altruism in social networks: evidence for a “kinship premium”’, British Journal of Psychology 104: 283–95.

- Dederichs, K. (2022) ‘Volunteering in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic: who started and who quit?’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 1–17. doi:10.1177/08997640221122814.

- Egerton, M. and Mullan, K. (2008) ‘Being a pretty good citizen: an analysis and monetary valuation of formal and informal voluntary work by gender and educational attainment’, British Journal of Sociology 59: 145–64.

- Einolf, C. J., Prouteau, L., Nezhina, T. and Ibrayeva, A. R. (2016) ‘Informal, unorganized volunteering’, in D. H. Smith, R. A. Stebbins and J. Grotz (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Volunteering, Civic Participation and Nonprofit Associations (pp. 223–241), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elzendoorn, B. (2020) ‘“Brabant helpt elkaar”, Facebookgroep voro mensen die willen helpen en mensen die hulp nodig hebben’, Omroep Brabant, 16 March. Available from: https://www.omroepbrabant.nl/nieuws/3172308/brabant-helpt-elkaar-facebookgroep-voor-mensen-die-willen-helpen-en-mensen-die-hulp-nodig-hebben.

- Engbersen, G., Van Bochove, M., De Boom, J., Burgers, J., Etienne, T., Krouwel, A., Van Lindert, J., Rusinovic, K., Snel, E., Weltevrede, A., Van Wensveen, P. and Wentink, T. (2020) De heropening van de samenleving, Rotterdam: Kenniswerkplaats Leefbare Wijken.

- Finkelstein, M. A. and Brannick, M. T. (2007) ‘Applying theories of institutional helping to informal volunteering: motives, role identity, and prosocial Personality’, Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal 35: 101–14.

- Huls, S. P. I., Sajjad, A., Kanters, T. A., Hakkaart-Van Roijen, L., Brouwer, W. B. F. and Van Exel, J. (2022) ‘Productivity of working at home and time allocation between paid work, unpaid work and leisure activities during a pandemic’, PharmacoEconomics 40: 77–90.

- Jones, M., Beardmore, A., Biddle, M., Gibson, A., Ismail, S. U., McClean, S. and White, J. (2020). ‘Apart but not alone? A cross-sectional study of neighbour support in a major UK urban area during the COVID-19 lockdown’, Emerald Open Research 2: doi:10.35241/emeraldopenres.13731.1

- Kahn, J. R., Mcgill, B. S. and Bianchi, S. M. (2011) ‘Help to family and friends: are there gender differences at older ages’, Journal of Marriage and Family 73: 77–92.

- Katz, H. and Feit, G. (2021) ‘Generosity in times of crisis’, in P. Wiepking, C. M. Chapman and L. H. Mchugh (eds.), Global Generosity Research, Tel Aviv: The Institute for Law and Philanthropy.

- Koolen-Maas, S. and De Wit, A. (2022) ‘Geven van tijd’, in R. Bekkers, B. Gouwenberg, S. Koolen-Maas and T. Schuyt (eds.), Geven in Nederland. Maatschappelijke betrokkenheid in kaart gebracht (pp. 231–258), Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kuyper, L. and Putters, K. (2020) Zicht op de samenleving in coronatijd. Eerste analyse van de mogelijke maatschappelijke gevolgen en implicaties voor beleid, The Hague: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

- Latsuzbaia, A., Herold, M., Bertemes, J.-P. and Mossong, J. (2020) ‘Evolving social contact patterns during the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg’, PLoS One 15: e0237128.

- Lau, A. L. D., Chi, I., Cummins, R. A., Lee, T. M. C., Chou, K.-L. and Chung, L. W. M. (2008) ‘The SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) pandemic in Hong Kong: effects on the subjective wellbeing of elderly and younger people’, Aging and Mental Health 12: 746–60.

- Lee, Y.-J. and Brudney, J. L. (2012) ‘Participation in formal and informal volunteering: implications for volunteer recruitment’, Nonprofit Management and Leadership 23: 159–80.

- Lee, I. and Tipoe, E. (2021) ‘Changes in the quantity and quality of time: use during the COVID-19 lockdowns in the UK: who is the most affected?’, PLoS One 16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258917.

- Lim, C. and Laurence, J. (2015) ‘Doing good when times are bad: volunteering behaviour in economic hard times’, British Journal of Sociology 66: 319–44.

- Mak, H. W. and Fancourt, D. (2022) ‘Predictors of engaging in voluntary work during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyses of data from 31,890 adults in the UK’, Perspectives in Public Health 142: 287–96.

- Musick, M. A. and Wilson, J. (2008) Volunteers. A Social Profile, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Penner, L. A., Brannick, M. T., Webb, S. and Connell, P. (2005) ‘Effects on volunteering of the September 11, 2001, attacks: an archival analysis’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35: 1333–60.

- Piatak, J. S. (2016) ‘Time is on my side: a framework to examine when unemployed individuals volunteer’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45: 1169–90.

- Plagnol, A. C. and Huppert, F. A. (2009) ‘Happy to help? Exploring the factors associated with variations in rates of volunteering across Europe’, Social Indicators Research 97: 157–76.

- Putnam, R. D. (2002) ‘Bowling together’, The American Prospect 13: 20–2.

- Ramaekers, M., Savelkoul, M., Van Groenestijn, P., Scheepers, P. and Verbakel, E. (2021) Social and Cultural Developments in the Netherlands COVID-19 Panel Survey, The Hague: Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS).

- Ramaekers, M. J. M., Verbakel, E. and Kraaykamp, G. (2022) ‘Informal volunteering and socialization effects: examining modelling and encouragement by parents and partner’, Voluntas 33: 347–61.

- Rijksoverheid (2020) TV-toespraak van minister-president Mark Rutte. Available from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/regering/bewindspersonen/mark-rutte/documenten/toespraken/2020/03/16/tv-toespraak-van-minister-president-mark-rutte.

- Rotolo, T., Wilson, J. and Dietz, N. (2015) ‘Volunteering in the United States in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44: 924–44.

- Safi, M., Coulangeon, P., Godechot, O., Ferragina, E., Helmeid, E., Pauly, S., Recchi, E., Sauger, N. and Schradie, J. (2020) When Life Revolves Around the Home: Work and Sociability During the Lockdown. 2. Coping with Covid-19: Social Distancing, Cohesion and Inequality in 2020 France, Paris: Sciences Po – Observatoire sociologique du changement.

- Savelkoul, M., Van Groenestijn, P., Scheepers, P., Cobussen, M., Van Hek, M. and Eisinga, R. (2020) Social and Cultural Developments in the Netherlands. Documentation of a National Survey on Social Cohesion and Modernization, The Hague: Data Archiving and Network Services (DANS).

- Savelkoul, M., Van Groenestijn, P., Scheepers, P., Lubbers, M., Van Der Vleuten, M. and Eisinga, R. (2019) Social and Cultural Developments in the Netherlands. Documentation of a National Survey on Social Cohesion and Modernization, The Hague: Data Archiving and Networked Services.

- Sevilla, A. and Smith, S. (2020) ‘Baby steps: the gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36: S169–S186.

- Statistics Netherlands (2021) Statline – Bevolking; onderwijs en migratieachtergrond 2003–2021. Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82275NED/table.

- Stewart-Williams, S. (2007) ‘Altruism among kin vs. nonkin: effects of cost of help and reciprocal exchange’, Evolution and Human Behavior 28: 193–8.

- Van de Wiel, M. (2020) ‘Haagse hangjongeren maken voedselpakketten, “Waarom ook niet”’, Nationale Omroep Stichting, 7 April. Available from: https://nos.nl/collectie/13839/artikel/2329664-haagse-hangjongeren-maken-voedselpakketten-waarom-ook-niet.

- Van Kesteren, J., Bussink, H. and Van der Werff, S. (2021) ‘Zorg voor kinderen ook tijdens lockdown vooral bij moeders’, Tijdschrift Voor Arbeidsvraagstukken 37: 79–89.

- Van Tienen, M., Scheepers, P., Reitsma, J. and Schilderman, H. (2011) ‘The role of religiosity for formal and informal volunteering in the Netherlands’, Voluntas 22: 365–89.

- Verba, S., Scholzman, K. L. and Brady, H. E. (1995) Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Verbakel, E., Raiber, K. and de Boer, A. (2021) ‘Changes in informal care provision during the first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 in the Netherlands’, Mens en Maatschappij 96: 411–39.

- Wang, L. (2021). ‘Informal volunteering', in K. Holmes, L. Lockstone-Binney, K. A. Smith & R. Shipway (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Volunteering in Events, Sport and Tourism (pp. 473–484). London: Routledge.

- Wang, L., Mook, L. and Handy, F. (2017) ‘An empirical examination of formal and informal volunteering in Canada’, Voluntas 28: 139–61.

- Wilson, J. and Musick, M. (1997) ‘Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work’, American Sociological Review 62: 694–713.

- Yerkes, M. A., André, S. C. H., Besamusca, J. W., Kruyen, P. M., Remery, C. L. H. S., Van der Zwan, R., Beckers, D. G. J. and Geurts, S. A. E. (2020) ‘“Intelligent” lockdown, intelligent effects? Results from a survey on gender (in)equality in paid work, the division of childcare and household work, and quality of life among parents in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 lockdown’, PLoS One 15: e0242249.

- Zheng, Z., Peng, F., Xu, B., Zhao, J., Liu, H., Peng, J., Li, Q., Jiang, C., Zhou, Y., Liu, S., Ye, C., Zhang, P., Xing, Y., Guo, H. and Tang, W. (2020) ‘Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Infection 81: e16–e25.