ABSTRACT

Research on populism is more abundant than ever, but the Ukrainian case is usually neglected in the comparative literature. This article fills this gap by providing a systematic analysis of the populism of Zelensky’s Servant of the People (SN) at the time of its electoral breakthrough in 2019, and it does so by adopting a broader European perspective. We argue that the success of Zelensky’s SN in 2019 should not be interpreted as something idiosyncratic or country-specific. On the contrary, we show that Zelensky’s SN is the Ukrainian manifestation of valence populism, a populism variety typically found in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). By combining qualitative and quantitative evidence, the analysis reveals that Zelensky’s SN, like the other valence populists in the CEE region, focused its agenda on non-positional topics, such as anti-corruption appeals, political transparency and moral integrity. At the same time, similarly to the other valence populist parties, the positions of Zelensky’s SN on economic and socio-cultural issues were intentionally blurry and elusive, to reach a broader group of voters. The conceptualization of SN suggested in the article allows for a better integration of the Ukrainian case into future comparative research on populism.

Introduction

Ukraine is often overlooked in the comparative literature, and this also applies to the analysis of populism, one of the buzzwords of our times. Most notably, the Ukrainian case is neglected in the cross-national research on the topic (cf. Kuzio Citation2010; March Citation2017; Zulianello Citation2020). Among other things, this tendency is connected to the difficulty of applying the ideational approaches to populism dominant in the West (Mudde Citation2004) to Ukrainian party politics, with its limited ideological coherence (Yanchenko Citation2021). In this article, we turn to the case of Volodymyr Zelensky’s party Servant of the People (Sluha Narodu, SN) to show that these analytical tensions can be resolved within the ideational approach by examining the Ukrainian case from the perspective of valence populism (Zulianello Citation2020; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023).

Although the rise of SN in the 2019 elections is often interpreted through the lens of populism (e.g. Ash and Shapovalov Citation2022; Mashtaler Citation2021), existing research lacks a solid analytical framework capable of inserting the Ukrainian case into a pan-European context. This article combines insights from political and communication sciences to make sense of the core features of Zelensky’s SN message at the time of its breakthrough in the 2019 elections, and it does so by complementing the study of the Ukrainian case with a broader, European perspective.

The contribution is structured as follows. The first section explains why studying Zelensky’s SN matters for comparative research on populism and outlines the key concepts and methods used in the article. Then, by qualitatively analyzing programmatic documents and speeches of both Zelensky and his party, we determine what issues and positions were at the core of SN’s agenda in the early phase. Subsequently, by using data from the 2019 round of the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al. Citation2022), the case of SN is put into comparative perspective by juxtaposing the key features of its profile with those of other parties in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). Before concluding the article, we reflect on potential explanations behind the concentration of parties akin to Zelensky’s SN in the CEE region.

Studying Zelensky’s Servant of the People in a comparative perspective

On 21 April 2019, the Ukrainian producer, actor, and comedian Volodymyr Zelensky defeated the incumbent Petro Poroshenko in the second round of the Ukrainian presidential elections (73.22% versus 24.45%; The Central Election Commission of Ukraine Citation2019). Zelensky’s first political decision after the inauguration was to dissolve the Verkhovna Rada (the unicameral parliament) of the 8th convocation, which meant early parliamentary elections, hence a chance for Zelensky to ride a wave of success and secure the maximum votes for his newly created SN party. From the outset, SN was a typical personalized-centralized party (Rahat Citation2022), with Zelensky’s recognition being its main political asset. SN was also a brand-new party, which allowed it to effectively detach from the established political elites in the eyes of Ukrainian voters. In July 2019, as a result of early parliamentary elections, SN became the first political party in the history of independent Ukraine to win a majority of seats in the Verkhovna Rada.

The rise of Zelensky’s SN is usually interpreted by evoking the notion of populism (e.g. Viedrov Citation2022; Yanchenko Citation2022), so it is important to begin by defining this hotly contested concept. Despite the plurality of different perspectives available in the literature (for an overview, see Rovira Kaltwasser et al. Citation2017), the so-called ‘ideational approach’ to populism has become increasingly popular among scholars. As Cas Mudde (Citation2017: 47) underlines, ‘even though it is still far too early to speak of an emerging consensus, it is undoubtedly fair to say that the ideational approach to populism is the most broadly used in the field today’. According to this approach, populism is understood as a particular set of ideas characterized by a moral and Manichean conflict between the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ and focused on the glorification of the ‘general will of the people’ (Mudde Citation2004: 543). Populism is considered a thin-centred ideology that typically interacts with other ‘thicker’ ideological elements (Mudde Citation2017). This feature results in its ‘chameleonic’ nature (Taggart Citation2004: 275): populist actors are found across the whole political spectrum, and it is appropriate to speak of varieties of populism (e.g. Zulianello Citation2020).

As for the Ukrainian case of populism, focusing on it is particularly important considering the long-acknowledged challenges of studying populism in post-Soviet states, where the application of the ideational approach is hampered by the lack of ideologically distinct political parties (March Citation2017; Yanchenko Citation2021). As a result, research on Ukrainian populism is mainly represented by single-case studies (cf. Kuzio Citation2010). This applies equally to the recent interpretations of Zelensky’s SN, as the studies tend to be country-specific and idiosyncratic (cf. Chaisty and Whitefield Citation2022). In this respect, putting Ukrainian populism in a broader comparative context is much needed to improve our knowledge of the populist phenomenon beyond the geographical areas more typically studied by scholars (Western Europe, Northern and Latin America).

The goals of this paper are thus three-fold. First, we assess whether Zelensky’s SN was populist at the time of its electoral ascendancy in 2019 and identify the specific features of its message beyond populism; second, by adopting a broader comparative perspective, we determine if similar cases are found elsewhere in Europe; and third, we utilize the cross-national literature on populism to situate Zelensky’s SN and similar political parties in a wider historical and geographic context.

In methodological terms, these tasks are achieved by adopting a mixed-method research strategy, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches and sources. First, by means of the qualitative analysis of key primary sources such as election programmes, interviews, speeches and debates (), we determine the core ideological features of Zelensky’s SN. To carry out the qualitative analysis we adopt the so-called ‘causal chain approach’, which enables us to determine the ‘importance of the various features within the […] ideology as a whole’ (Mudde Citation2002: 23). More specifically, such an approach is aimed at ‘discovering the hierarchy of the various features […] of the ideology. This is done by following the direction of the argumentation and assessing what is the prime argument, what is the secondary argument, etc.’ (Mudde Citation2002: 23). After the qualitative analysis of the core ideological features underlying SN’s message at the time of its rise in 2019, we assess whether those features are similar to other parties in Europe. Particularly, by using data from the 2019 round of the CHES (Jolly et al. Citation2022), it is possible to complement the qualitative evidence with a broader quantitative analysis, which reveals that the key features of Zelensky’s SN are the same as in a populist variety commonly found in CEE, namely valence populism.

Table 1. Primary sources used in the analysis.

The core features of Zelensky’s Servant of the People

In the following pages we investigate whether Zelensky’s SN actually manifested the core features of populism, namely people-centrism, anti-elitism, and the general will of the people, at the time of its electoral breakthrough. Then, we determine what topics and issues dominated SN’s agenda in 2019.

The people, the elite, and the general will

People-centrism has always been an important element of Zelensky’sFootnote1 political appeal, from his party’s very name, the eloquent ‘Servant of the People’, to one of his most popular slogans – ‘Each of us is the President’ (Zelensky Citation2019b).Footnote2 Indeed, Zelensky systematically emphasized his proximity to ‘the people’ in public communication:

Could I have ever imagined that I, an ordinary guy from Kryvyi Rih, would fight for the president’s seat against the person whom we … elected as the president of Ukraine in 2014? … I myself voted for Mr. Poroshenko. But I was wrong. We were wrong. (TSN Citation2019c)

Frequent references to ‘the people’ related Zelensky’s SN to many other political parties that competed in the 2019 elections, yet there were important differences. Most notably, Zelensky’s people-centrism was emphatically inclusive while most other parties and their leaders tended to discursively exclude certain segments of the Ukrainian population from the ‘we’ in-group. For instance, political communication of The Opposition Platform – for Life (OPZZh) targeted almost exclusively the older electorate with pro-Russian sentiments and nostalgia for the USSR; in turn, Poroshenko’s European Solidarity (YeS) mainly focused on the more patriotic electorate from central and western Ukraine (Yanchenko Citation2021). The rhetoric of Yuliia Tymoshenko’s All-Ukrainian Union ‘Fatherland’ (BA) was more inclusive, yet the party failed to attract younger and more educated voters (Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation Citation2019). Therefore, compared to other political actors, SN’s people-centrism was more comprehensive.

Another pillar of Zelensky’s political message was anti-elitism. Building upon the image shaped in the Servant of the People TV series, where Zelensky’s character scolded ‘corrupted’ Ukrainian politicians, Zelensky capitalized on that image during the 2019 campaign. The targets of his anti-elitist attacks were ‘the oligarchs’, embodied in the incumbent Poroshenko – Zelensky’s main political rival and one of the wealthiest people in Ukraine: ‘Today, he [Poroshenko] is the main leader, who is in opposition to the Ukrainian people. And this is the worst’ (RBC-Ukraine Citation2019). The figure of Poroshenko was also used to more broadly criticize what Zelensky dubbed ‘the power’: ‘I am disappointed in all of today’s authorities … It’s just that he [Poroshenko] is … the leader, which means that the greatest emphasis is placed on him’ (Visiting Dmitry Gordon Citation2018, 58:25–58:33). One of Zelensky’s main promises during the presidential campaign was to ‘bring in new professional people and break the [Ukrainian political] system’ (TSN Citation2019b, 30:59–31:40). Later, the same goal was declared in SN’s manifesto, which explained Ukraine’s alleged stagnation in terms of ‘the old political system – that of corruption, lies and arbitrariness’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2019).

Closely related to anti-elitism, anti-establishment rhetoric was another key component of Zelensky’s communication. Anti-establishment rhetoric can be understood as the manifestation of scepticism towards a given political system in general, rather than to some specific political actors (Hartleb Citation2015). Thus, Zelensky’s main principle when recruiting people to his presidential team and to SN was to filter out those candidates who had any previous experience in politics, regardless of which party or faction they represented. Zelensky emphasized this rule frequently in public, including in those cases when he himself violated it: ‘Oleksandr Danyliuk. He’ll be responsible for international relations, economy, financial and banking policy. Oleksandr was a minister … this is the only drawback. But I believe such professionals are necessary to destroy the old system’ (Zelensky introduces his team during the first talk show appearance, TSN Citation2019b, 04:25–04:48). According to the survey data, anti-establishment appeals were crucial for Zelensky’s and his party’s success in 2019. The majority of Ukrainians who were going to vote for Zelensky in the first round of the presidential elections explained their choice with the following rationale: ‘He is a person outside the system, “a new face” in politics’ (Kyiv International Institute of Sociology Citation2019).

Compared to those who voted for other Ukrainian political parties, SN’s voters were significantly more likely to believe that all Ukrainian parties offered identical programmes and were essentially the same (Chaisty and Whitefield Citation2022: 123), which is a common indication of strong anti-establishment sentiments (Hartleb Citation2015: 41). The fact that such types of voters rallied around SN means that, from their perspective, Zelensky’s party was perceived as being significantly different from the others.

Another remarkable feature of SN was how it embraced the idea of popular sovereignty. Thus, the very first section of SN’s 2019 manifesto raises the issue of accountability of the authorities in Ukraine and proposes specific steps to increase people’s sovereignty:

Abolish the immunity of the people’s deputies; introduce a mechanism for recalling deputies who have lost the confidence of voters; create a mechanism of the people’s veto on the recently adopted legislation; introduce mechanisms of citizens’ impact on decision-making via referendums. (Sluha Narodu Citation2019)

The core issues of SN beyond populism

The analysis so far suggests that in 2019, Zelensky’s SN possessed all the constitutive attributes of populism as identified by the ideational approach. But what were the main features of the party beyond populism?

One of the central issues for Zelensky was a promise to eradicate corruption. Anti-corruption appeals could be found both in Zelensky’s presidential programme under the section ‘Not fighting corruption, but defeating it’ (Zelensky Citation2019a) and in SN’s manifesto, where the party pledged to ‘introduce mandatory confiscation of the corrupt officials’ property’ and ‘ensure real independence of anti-corruption bodies’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2019). At the same time, Zelensky himself was rather vague about how exactly he was going to fulfil those goals. For example, in his first big interview after the nomination announcement, Zelensky showed quite a naïve understanding of the issue:

We will clean up all corruption … And we will have one law for all. Just as I have been taught at Law school – so it will be in life … No exceptions. [Journalist: And how are you going to do it?] Very easy. We’ll set the rules, and everyone will live by those rules. [Journalist: Do you really think it’s that simple?] I don’t think – I dream of it. (Kravets and Sarakhman Citation2019)

The heightened attention of Zelensky’s SN to corruption resonated with the public sentiment in Ukraine. As a 2018 poll shows, most Ukrainians regarded corruption as the main problem hindering the country’s development (e.g. 79% in August 2018, Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation Citation2018). In 2019, such sentiments were fuelled further by the release of journalistic investigations exposing corruption in the highest echelons of power (Horbyk Citation2020). Due to the salience of the topic of political corruption in the media, the established parties tried to downgrade the issue by ignoring it in their public communication, and this especially applied to Poroshenko’s YeS.

The quest for political transparency was also among the core goals for Zelensky’s SN. The idea of Ukraine ruled by a mysterious elite club with puppets in the government was unambiguously articulated in the Servant of the People TV series (Makarychev Citation2022: 115–135). Zelensky and his team offered an alternative to such a vision – an increasing openness in politics. For example, this is how Zelensky commented on his presidential campaign strategy:

I really want an open election campaign. I want people to see everything we do in real time: Building up our team, writing our program, our congress meetings, going to the CEC [Central Election Commission]. We will broadcast and show all of this. I believe that we should have an open country with an open government. (Kravets and Sarakhman Citation2019)

Lastly, during his campaign, Zelensky paid special attention to the moral dimension of politics. He promised to bring people of high moral standards to the government and called for the moral integrity of MPs of the 8th convocation during his inaugural speech: ‘Hang pictures of your children [in your cabinets] and look them in the eye before making any decision’ (Zelensky Citation2019b). While criticizing an immoral and cynical establishment, Zelensky tended to position himself as an honest man, e.g. ‘[My parents] gave me moral pointers, they gave me intolerance to lies. That is why I always react so painfully to any lie … This is the main trait that my parents gave me’ (Visiting Dmitry Gordon Citation2018, 01:57–03:19).

The image of Zelensky as a family man and decent person was extremely important in the eyes of Ukrainians. A study based on 25 in-depth interviews with Zelensky’s voters showed that for all of them, Zelensky’s moral qualities were more important than his professional competence (Yanchenko Citation2022). Zelensky understood this well. In his parting words before the first round of the presidential election, he advised Ukrainians: ‘Just choose a candidate who is closer to you’ (Detector Media Citation2019).

The elusive economic and socio-cultural positions of SN

The conducted analysis suggests that, in addition to populism, the core topics for Zelensky’s SN were the fight against corruption and the quest for moral integrity, political transparency and political reform. Interestingly, all of them are non-positional in nature: in fact, they are valence issues that are ‘uniformly liked … or disliked among the electorate’ (Curini Citation2018: 13). And yet, what was SN’s agenda in respect to the most pressing positional issues?

In the phase of its electoral breakthrough, Zelensky’s SN attributed only limited importance to positional issues related to economic, social and cultural policy domains. Furthermore, such issues were typically discussed in a very ambiguous way. For example, Zelensky’s main economic advisor Danyliuk claimed that ‘neither the president nor the government should interfere with the development of business activities in the country’ (Korniienko Citation2019); SN, in turn, promised to ‘introduce a “Ukrainian citizen’s economic passport” that guarantees that every child obtains a share from the exploitation of natural resources’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2019). Another vivid illustration of SN’s eclectic economic position is represented by the deoligarchization law (a step towards increasing state control over Ukraine’s richest and reducing social inequalities) and the creation of a land market in Ukraine (a step towards economic liberalization), both initiated by Zelensky and his team. Furthermore, SN’s manifesto promised to introduce beneficial conditions for foreign investors, which aligns with the right-wing belief in open markets; yet on the other hand, the same document discussed the need to create a ‘National Economic Strategy’ aimed at achieving a ‘higher-than-average European income and quality of life for Ukrainians’, which reflects the left-wing belief in government intervention in the economy to improve social welfare (Sluha Narodu Citation2019). Thus, Zelensky’s SN with its economic eclecticism was different from most other Ukrainian parties, which traditionally adhered to left-wing economic agendas (Vox Ukraine Citation2019).

Zelensky was also little interested in specifying his position in regard to the socio-cultural dimension. In various interviews, he could not intelligibly answer questions about his views on the language and memory politics in Ukraine (e.g. Kravets and Sarakhman Citation2019; TSN Citation2019c, 07:36–08:28), while the section on national identity was absent from SN’s manifesto. The only manifesto section partly related to the socio-cultural policy domain was the concluding one, called ‘National Unity and Civil Accord’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2019). There, the main emphasis was again placed on the inclusive construction of ‘the people’ through the ‘humanitarian policy that will promote the cultural, civic and spiritual unification of Ukrainian citizens’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2019). Survey data shows that Zelensky’s reluctance to take a clear stance on the most sensitive socio-cultural issues did help him to attract political supporters: Zelensky’s voters were ‘more likely to hold moderately strong or neutral opinions on key [positional] issues in Ukrainian politics and to mix both Russian and Ukrainian languages in their daily lives’ (Ash and Shapovalov Citation2022: 460) than voters of other political parties. In this regard, Onuch and Hale (Citation2022: 24) argue that in 2019, established parties overestimated the narrative about the great socio-cultural divide allegedly determining Ukrainian politics and ‘obscured the middle ground into which Zelensky tapped’.

A unicum? Zelensky’s Servant of the People in a comparative perspective

The qualitative analysis of Zelensky’s SN message revealed that it manifested the core features of populism at the time of its electoral breakthrough in 2019. Furthermore, the case-study also indicated that the agenda of Zelensky’s SN emphasized non-positional issues, such as corruption, rather than focusing attention on economic or socio-cultural issues. However, a key question remains unanswered: what was the specific variety of populism embodied by Zelensky’s SN? Did it represent an idiosyncratic manifestation of the populist phenomenon tailored to the specific features of Ukrainian politics and society or, on the contrary, did it resemble other cases in Europe?

Ash and Shapovalov (Citation2022: 461) argue that the ‘theories explaining far-right, far-left or even centrist/technocratic populism would struggle to explain the rise of Zelensky and Sluha Narodu’. We agree that neither of these concepts is appropriate to account for the distinctive features of Zelensky’s SN, and yet this does not imply that we are dealing with a unicum. On the contrary, we argue that Zelensky’s SN in 2019 is best understood as a case of valence populism, which is substantially different from the other populist varieties found in contemporary Europe (Zulianello Citation2020; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023).

The literature suggests that right-wing and left-wing populists combine populism with a ‘thick’ ideological element – an exclusionary notion of the people in the former (Mudde Citation2004) and some form of socialism in the latter (Mudde Citation2017; see also Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Citation2019). Valence populists, instead, differ from both right-wing and left-wing populists in at least three respects (for details, see Zulianello Citation2020; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023). First, valence populists lack a ‘thick’ ideological element in their profile, meaning that the only core element of their ideology is a ‘thin’ one – populism itself. Second, valence populists deliberately avoid clear ideological positioning along the left–right dimension: for this reason, the use of the labels ‘left-wing’, ‘right-wing’ and even ‘centrist’ to refer to such actors is inappropriate because they are all intrinsically positional in nature. Third, valence populists primarily compete by focusing on non-positional issues, such as corruption, moral integrity, political transparency and political reform, rather than by taking more or less clear positions on the economic or socio-cultural (left–right) dimensions. Valence populism tends to be particularly common in the CEE region (Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021).

To show that the features of Zelensky’s SN in 2019 are consistent with those of valence populist partiesFootnote3 in CEE (), we use data from the extensive Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al. Citation2022). Even though Ukraine is not covered by such a dataset, by focusing on specific items of the 2019 round of the CHES (), it is possible to interpret in a comparative fashion the core features of Zelensky’s SN, as identified by the qualitative analysis carried out earlier in this paper: the predominant focus on non-positional issues, especially corruption, and its elusive economic and socio-cultural positions.

Table 2. List of valence populist parties in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) included in CHES 2019.

Table 3. Items of the 2019 CHES used in the analysis.

The core issues of valence populism in CEE

Following the conceptualization of valence populism (Zulianello Citation2020; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023), the first 2019 CHES item useful for comparing the case of Zelensky’s SN with other cases in CEE is the salience of reducing political corruption, a typical example of non-positional competition because voters hold identical positions on that issue (Stokes Citation1963). This is different from the case of positional or spatial issues, over which voters realistically take different positions, for example abortion, the European Union, immigration, taxation (Adams et al. Citation2005). Indeed, political corruption is an issue that is consistently disliked by the electorate and was considered as a paradigmatic instance of valence issues even in the original formulation of the concept by Stokes (Citation1963).

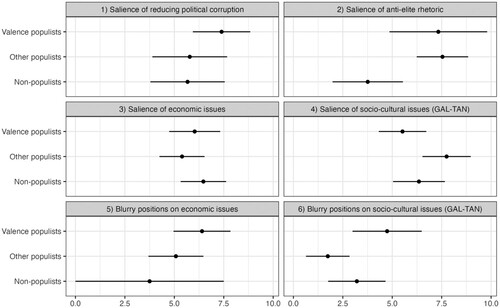

As previously discussed, Zelensky’s SN paid paramount attention to the issue of corruption, including the very ambitious goal of ‘defeating it’ (Zelensky Citation2019a), a point that makes it consistent with other valence populists in CEE. As shown in , the average values for the salience given to political corruption by valence populists (7.39) are considerably higher, not only in comparison to non-populist actors (5.67) but also in comparison to the other populistsFootnote4 in CEE (5.78).

Figure 1. Mean and standard deviations of valence populists, other populists and non-populist parties in CEE. Total number of observations N = 103. The analysis includes 9 valence populists, 17 other populist, and 77 non-populist parties.

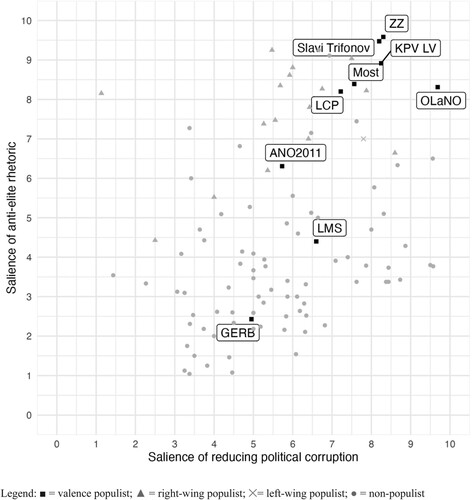

If we focus at the level of the individual valence populists, an outstanding score emerges in the case of the Slovak OLaNO (9.69); the party founded by Igor Matovič was not only the one with the highest emphasis on reducing political corruption in CEE, but also across all the 32 countries included in the CHES dataset. OLaNO is commonly described as a party whose raison d’être is an anti-corruption agenda (Petrović et al. Citation2022: 8), and whose vision is centred on a ‘radical, uninhibited political performance’ (Hloušek et al. Citation2020: 101). While, on average, valence populists tend to emphasize corruption more than the other parties, according to the CHES 2019 data, a valence populist party that significantly differed from the others is the Bulgarian GERB, with a salience of 4.95. This may be due to its long period in power (2009–2021), during which GERB ‘developed some characteristics of a clientelist party’ (Stoyanov and Lyubenov Citation2022: 98).

While valence populists clearly differ from both populist and non-populist parties in terms of their emphasis on reducing political corruption – a paradigmatic non-positional issue – they are more similar to the other varieties of populism when it comes to their stance on anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric (). In this respect, while the average value of valence populists (7.33) is more than twice the average value of the universe of non-populists (3.76), it is pretty similar to that of other populist parties (7.54). The reason for this similarity between valence populists and the other populists is two-fold. First, and more obviously, the salience of anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric is a defining feature of the populist phenomenon itself. As Mudde (Citation2010: 1177) underlines, ‘the ideological feature of populism can only be studied through its anti-elite or anti-establishment side’. Second, and less trivially, ‘the “valence content” of anti-elitism is of course not a perfect one’ (Curini Citation2020: 1418). Unlike a typical valence issue such as corruption (Stokes Citation1963), anti-elite and anti-establishment messages are characterized by ‘quasi-valence’ features because ‘anti-elitism is not a value shared by the entire electorate’ (Curini Citation2020: 1418). In other words, it could be said that although anti-establishment and anti-elite messages bear some similarities to valence issues, they are not ‘pure’ valence issues. While keeping these caveats in mind, it can nevertheless be noticed from that valence populists tend to emphasize both reducing corruption, a typical non-positional issue, and anti-elitism, a ‘quasi-valence’ issue.

Figure 2. Salience of reducing political corruption and anti-elite rhetoric (labels refer to valence populist parties). Legend: ▪ = valence populist; ▴ = right-wing populist; `× = left-wing populist; ● = non-populist.

It is important to recall that the CHES 2019 provides data on only one of the key non-positional issues that can be mobilized by valence populists (i.e. corruption), but not on the other relevant non-positional issues, such as political transparency, moral probity and democratic performance (Zulianello Citation2020). The literature suggests that two partial exceptions to the trend shown in , the Slovenian LMS and the Czech ANO 2011, indeed focused on non-positional issues that are typical of valence populism but cannot be accounted for by using the 2019 CHES data. For instance, the Slovenian LMS focused on ‘the need to fundamentally revise the political game’ (Krašovec and Deželan Citation2019: 317), while the Czech ANO 2011 concentrated its efforts on presenting itself as ‘a technocratic and competent party, successfully managing the state finances and acting to resolve people’s problems effectively’ (Hloušek et al. Citation2020: 52). More generally, it is worth underlining that valence populists in CEE often emphasize technocratic solutions (e.g. Guasti and Buštíková Citation2020; Havlík Citation2019).

The elusive economic and socio-cultural positions of valence populism in CEE

The qualitative analysis of Zelensky’s SN suggested that in the phase of its electoral breakthrough, it presented very elusive, if any, positions on economic and socio-cultural issues. suggests that positional competition, whether along economic or socio-cultural lines, is not in the primary focus of valence populists. Valence populists in CEE present, on average, a lower emphasis (5.52) on socio-cultural issues (GAL-TAN) in comparison with both other populist (7.75) and non-populist parties (6.35). However, when it comes to economic issues, valence populists present a lower emphasis (6.03) in comparison to non-populists (6.47) but higher than the other populists in the area (5.39). In that regard, it is important to stress that the salience given by valence populists to economic issues does not imply that they primarily compete by focusing on positional issues, as the emphasis given to the economy (6.03) is much lower than the emphasis they place on reducing corruption (7.39).

The key point is that even though some valence populists pay substantial attention to economic or socio-cultural issues, such a salience is often the consequence of very elusive and ambiguous positions, possibly with the goal of reaching a broad and cross-cutting group of voters. Indeed, emphasizing the economy or socio-cultural domain does not imply that a given party primarily engages in positional competition, and this point is well exemplified by the two Bulgarian parties under analysis. The already-mentioned GERB presents a considerably higher emphasis on economic issues (8.00) in comparison to the other valence populists in CEE, while ITN displays the highest emphasis on socio-cultural issues (9.00). However, despite its high emphasis on the economy, GERB ‘can be considered as a party without ideology [as it] is not based on a specific ideology or political profile, even though it is a part of the European People’s Party (EPP) and defines itself as “centre-right” and “Christian-democratic” party’ (Todorov Citation2018: 52). Similarly, despite its attention to socio-cultural issues, ITN does not have ‘a clear ideology’, as its ‘programme seem[s] to be limited to a populist agenda’ (Kanev Citation2021: 66). Both GERB and ITN are often considered by scholars to be devoid of a specific ideology because, like other valence populists, their profiles lack an apparent ideological core.

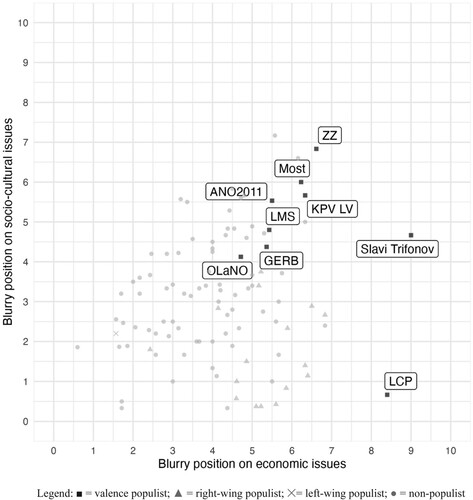

Indeed, valence populists are not constrained by the presence of a ‘thick’ ideology (such as nativism or socialism), and for this reason their positions on economic and socio-cultural issues are typically unclear and/or erratic. As the previous pages suggested, this also applied to the agenda of Zelensky’s SN in its early phase. SN’s similarity with the other cases of valence populism in the CEE can be illustrated by focusing on the 2019 CHES items measuring the blurriness of party positions on economic and socio-cultural issues. clearly indicates that valence populists have, on average, considerably more blurry positions on both economic (6.40) and socio-cultural issues (4.74), not just in comparison to non-populist parties (3.75 and 3.21, respectively), but also vis-à-vis other populists (5.08 and 1.74, respectively).Footnote5

enables a visual representation of the positional blurriness of political parties in CEE in terms of economic and socio-cultural issues. As can be seen, it suggests that valence populists have ambiguous positions on both economic and socio-cultural issues, similarly to the case of Zelensky’s SN. Most notably, while right-wing populists (the triangles in ) present blurry positions on economy but are very clear when it comes to socio-cultural issues – in line with the findings by Rovny and Polk (Citation2020), it can be seen that valence populists display a tendency towards position blurring on both the economic and the socio-cultural dimensions.

Figure 3. Blurry positions on economic and socio-cultural issues (labels refer to valence populist parties). Legend: ▪ = valence populist; ▴ = right-wing populist; ✕ = left-wing populist; ● = non-populist.

Moving to the individual cases, the Bulgarian ITN and the Lithuanian LCP emerge as the parties with the highest levels of position blurring on economic issues, not just in CEE but also across the entire CHES 2019 dataset (respectively, 9.00 and 8.40). Nevertheless, it can be noticed that the Lithuanian LCP is an outlier on socio-cultural issues, where it presents only negligible levels of position blurring (0.67). As suggests, the valence populist party with the highest levels of position blurring on socio-cultural issues is the Croatian ZZ (6.83). In fact, the ideological features of the party are described as ‘unclear’ (Albertini and Vozab Citation2017: 5), also because of its ‘syncretic scope that aim[ed] to accommodate heterogeneous demands’ (Petsinis Citation2020: 9).

Zelensky’s SN as part of the populist phenomenon in the CEE region

As can be seen from the previous section, the phenomenon of valence populism is concentrated within the CEE region, and this also holds true if we consider Zelensky’s SN to be representative of the same variety of populism. This geographic pattern is not completely novel: since the collapse of the USSR, the CEE region has seen different waves of parties belonging to this type, even though scholars use different terms when referring to the populist parties we consider to be valence populists, such as centrist populism (Učeň Citation2007) or exclusively populist parties (Havlík and Pinková Citation2012). In particular, Učeň (Citation2007: 54) observes that in the late 1990s, numerous CEE countries witnessed the emergence of populist parties that ‘shied away from ideological pledges’ and built their political appeal on promises of ‘curbing corruption, improving responsiveness, and promoting economic development’.Footnote6

When addressing the question of the regional concentration of valence populism, we should reflect on why certain populist parties in CEE choose not to attach to ‘thicker’ ideologies and instead compete along non-positional issues. Most authors link this peculiarity with the region’s communist past, which prevented CEE countries from preserving or developing ideologically distinct political parties (e.g. Tismaneanu Citation1996). According to Stanley (Citation2017: 143) ‘Central and Eastern European party politics is … ideologically “hollowed out” in comparison to its Western European counterpart, with parties competing over claims to competence and moral probity rather than distinct policy platforms’ (Stanley Citation2017: 143). This ‘ideological vacuum’ (March Citation2017) is especially typical of post-Soviet countries that were integrated into the communist regime longer and more firmly than the former USSR’s ‘satellite states’. Communist legacies thus resulted in less institutionalized, more personalized, and more opportunistic politics in CEE and generated public demand for non- or sometimes even anti-ideological parties (Učeň Citation2007). In Ukraine, Zelensky and SN managed to fill this space during the presidential and parliamentary campaigns of 2019.

The communist past shared by CEE countries not only resulted in their blurry ideological landscapes during the post-Soviet era but was also associated with a certain type of political culture. For example, Stanley (Citation2017: 143-144) argues that ‘the obligatory nature of political participation under communism … inculcated an attitude of political cynicism among the citizens of communist regimes’. It is not surprising that in most CEE countries, this attitude was converted into strong anti-ideological and anti-party sentiment after the fall of the USSR, creating fertile ground for the anti-establishment rhetoric of valence populists. Similarly, the communist era’s flawed economies, undeveloped civil societies, and prevalence of informal institutions resulted in corruption becoming a major issue in CEE (Engler Citation2016; Engler et al. Citation2019). Particularly in 2019, Ukraine, along with most other CEE countries, was considerably worse in the Corruption Perception Index than their Western European counterparts (Transparency International Citation2019), which explains why certain populist actors in the region decided to prioritize anti-corruption and other valence issues. These are just some of the potential explanations behind the tendency of valence populists to proliferate in CEE, yet they may serve as a starting point for further investigation of this phenomenon.

Conclusion

In this article we asked whether at the time of its electoral breakthrough Zelensky’s SN was an idiosyncratic manifestation of Ukrainian politics or if, instead, similar parties can be found elsewhere. First, by means of a qualitative analysis of Zelensky’s SN profile, we argued that it should be qualified as populist. Second, using data from the 2019 round of the CHES we showed that the populism embodied by Zelensky’s SN was hardly country-specific or unique. On the contrary, Zelensky’s SN can be interpreted as part of a broader phenomenon typical of CEE, namely valence populism (Zulianello Citation2020; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2021; Zulianello and Larsen Citation2023). Lastly, we also discussed some of the reasons for the disproportionate presence of valence populist parties in CEE in comparison to the rest of Europe, arguing that post-communist political landscapes and cultures play a key role here.

Our study revealed that, like other valence populist parties, Zelensky’s SN consistently focused its agenda on typically non-positional issues, most notably corruption, transparency and moral integrity, and displayed blurry and elusive economic and socio-cultural positions not by accident, but by design. This is due to the fact that the stances of valence populists in relation to economic and socio-cultural issues are not inspired by a ‘thick’ ideology, as in the case of right-wing and left-wing populism. Instead, the economic and socio-cultural positions of Zelensky’s SN are, like other valence populists, ‘primarily informed by an unadulterated conception of populism (with other ideological elements, if any, playing a marginal or secondary role), and are therefore flexible, free-floating and, often, inconsistent’ (Zulianello Citation2020: 332).

Even though our findings are based on the analysis of materials from 2019 election campaigns, they are equally applicable to the first half of Zelensky’s presidential term – up until the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, when Zelensky’s political rhetoric changed profoundly. Still, the most up-to-date official document dedicated to SN’s political profile describes the party’s ‘ideology’ as ‘Ukrainian centrism’, but in fact it manifests the same reluctance to take a clear ideological position as identified in our analysis: ‘We are neither “right” nor “left”. Neither nationalists nor separatists … We strive to build a country where peace, order and prosperity will reign – and not some utopias or ideological myths’ (Sluha Narodu Citation2020).

A broader implication of this article is that it conceptualizes SN in a way that allows for a better integration of the Ukrainian case into pan-European research on populism. Although in the past, scholars have shown interest in populism in Ukraine (e.g. Kuzio Citation2010; Makarychev Citation2022), a meaningful comparison of Ukrainian populism with the broader populist waves in other European countries has always been hindered by the lack of ideological coherence in Ukrainian party politics (Yanchenko Citation2021). This feature makes the application of an ideational approach challenging, because it typically expects populism to attach to a ‘thicker’ ideological element. Nevertheless, as we have shown in this article, if the concept of valence populism is incorporated as part of the analytical toolkit of the ideational approach, the seemingly idiosyncratic nature of many parties in the post-communist area no longer represents an analytical problem, allowing for innovative research agendas on populist politics integrating insights from both the East and West.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Erik Gahner Larsen for his help with data analysis and the two anonymous referees for their useful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kostiantyn Yanchenko

Kostiantyn Yanchenko is a research assistant at the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Hamburg (Germany). His research has been published in, among others, The International Journal of Public Opinion Research, Mass Communication and Society, and The International Journal of Press/Politics.

Mattia Zulianello

Mattia Zulianello is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Trieste (Italy). His research has been published in, among others, Electoral Studies, Government and Opposition, Quality & Quantity, and The International Journal of Press/Politics. He is the author of the book “Anti-System Parties” (Routledge, 2019).

Notes

1 Here, the distinction between Zelensky and SN is not useful due to the highly personalized nature of the latter.

2 All translations from Ukrainian and Russian languages were made by the authors.

3 Valence populist parties are identified following Zulianello and Larsen (Citation2021). The Bulgarian ITN and the Latvian KPV LV were not included in the list by Zulianello and Larsen (Citation2021) because the former did not contest the 2019 EU election, while the latter party gained less than 1% of the vote on that occasion. However, both present the defining features of valence populism and can be classified as such (see, respectively, Spirova Citation2021 and Petsinis and Wierenga Citation2021).

4 To distinguish between populist and non-populist parties, we follow the classification by Zulianello (Citation2020) and Zulianello and Larsen (Citation2021). Out of the 17 parties that fall in the category ‘other populists’, 16 belong to the category of right-wing populism and only one to that of left-wing populism (the Slovenian The Left).

5 As previously mentioned, only one case of left-wing populism was found in CEE among the parties included in the CHES 2019. For this reason, it worth underlining that the blurriness of the economic positions of the populist parties indicated in figure 1 is due to the predominant number of right-wing populists in the sample. In fact, in line with the previous findings in the literature (e.g. Rovny and Polk Citation2020), the data suggests that Slovenian The Left, the only left-wing populist included in the present analysis, is characterized by clear positions on the economy (1.57), while right-wing populists in the CEE have much more blurry positions in this dimension (5.29).

6 Učeň (Citation2007: 52) referred to such parties as, for example, the Party of Civic Understanding (SOP) in Slovakia, New Era (JL) in Latvia, Res Publica (RP) in Estonia, National Movement of Simeon II (NDSV) in Bulgaria, etc. On the shortcomings of the very term ‘centrist populism’, see Zulianello (Citation2020) and Zulianello and Larsen (Citation2021).

References

- Adams, J. F., Merrill III, S. and Grofman, B. (2005) A Unified Theory of Party Competition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Albertini, A. and Vozab, D. (2017) ‘Are “united left” and “human blockade” populist on Facebook? A comparative analysis of electoral campaigns.’, Contemporary Southeastern Europe 4(2): 1–19. doi:10.25364/02.4:2017.2.1.

- Ash, K. and Shapovalov, M. (2022) ‘Populism for the ambivalent: anti-polarization and support for Ukraine’s Sluha Narodu party’, Post-Soviet Affairs 38(6): 460–478. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2022.2082823.

- The Central Election Commission of Ukraine (2019) ‘Вибори Президента України 31 березня 2019 року’ [‘Elections of the President of Ukraine on March 31, 2019’]. https://www.cvk.gov.ua/vibory_category/vibori-prezidenta-ukraini/vibori-prezidenta-ukraini-2019.html.

- Chaisty, P. and Whitefield, S. (2022) ‘How challenger parties can win big with frozen cleavages: explaining the landslide victory of the servant of the people party in the 2019 Ukrainian parliamentary elections’, Party Politics 28(1): 115–126. doi:10.1177/1354068820965413.

- Curini, L. (2018) Corruption, Ideology, and Populism. The Rise of Valence Political Campaigning, London: Palgrave/MacMillan.

- Curini, L. (2020) ‘The spatial determinants of the prevalence of anti-elite rhetoric across parties’, West European Politics 43(7): 1415–1435. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1675122.

- Detector Media (2019) ‘“Выбирайте лицо”. Что рассказал зрителям ICTV Владимир Зеленский (расшифровка)’ [‘“Choose a Face.” What Vladimir Zelensky Told ICTV Viewers (transcript)’]. March 23. https://detector.media/medialife/article/165726/2019-03-23-vybyrayte-lytso-chto-rasskazal-zrytelyam-ictv-vladymyr-zelenskyy-rasshyfrovka/.

- Engler, S. (2016) ‘Corruption and electoral support for new political parties in Central and Eastern Europe.’, West European Politics 39(2): 278–304. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1084127.

- Engler, S., Pytlas, B. and Deegan-Krause, K. (2019) ‘Assessing the diversity of anti-establishment and populist politics in central and Eastern Europe’, West European Politics 42(6): 1310–1336. doi:10.1080/01402382.2019.1596696.

- Guasti, P. and Buštíková, L. (2020) ‘A marriage of convenience: responsive populists and responsible experts’, Politics and Governance 8(4): 468–472. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i4.3876.

- Hartleb, F. (2015) ‘Here to stay: anti-establishment parties in Europe’, European View 14(1): 39–49. doi:10.1007/s12290-015-0348-4.

- Havlík, V. (2019) ‘Technocratic populism and political illiberalism in central Europe.’, Problems of Post-Communism 66(6): 369–384. doi:10.1080/10758216.2019.1580590.

- Havlík, V. and Pinková, A. eds (2012) Populist Political Parties in East-Central Europe, Brno: Munipress.

- Hloušek, V., Kopeček, L. and Vodová, P. (2020) The Rise of Entrepreneurial Parties in European Politics, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Horbyk, R. (2020) ‘Road to the stadium: televised election debates and “Non-debates” in Ukraine: between spectacle and democratic instrument’, in J. Juárez-Gámiz, C. Holtz-Bacha and A. Schroeder (eds.), Routledge International Handbook on Electoral Debates, London: Routledge. pp. 157–165.

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2018) ‘Громадська думка населення щодо впливу на Україну інших країн’ [‘Public Opinion Regarding the Influence of Other Countries on Ukraine’]. October 24. https://dif.org.ua/article/gromadska-dumka-naselennya-shchodo-vplivu-na-ukrainu-inshikh-krain.

- Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (2019) ‘Хто за кого проголосував: демографія Національного екзит-полу на парламентських виборах−2019’ [‘Who Voted for Whom: Demographics of the National Exit Poll in the 2019 Parliamentary Elections]. July 30. https://dif.org.ua/article/khto-za-kogo-progolosuvav-demografiya-natsionalnogo-ekzit-polu-na-parlamentskikh-viborakh-2019?fbclid=IwAR3aO41HlTiPlAFF7t77_M0npcZNfQHoKEejTzp1zZsXzpV7EYfgN3XZbAU.

- Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M. and Vachudova, M. A. (2022) ‘Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2019’, Electoral Studies 75: 102420. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420.

- Kanev, D. (2021) ‘Élections parlementaires en Bulgarie, 4 avril 2021’, Blue 1(1): 64–69.

- Katsambekis, G. and Kioupkiolis, A. eds (2019) The Populist Radical Left in Europe, London; New York: Routledge.

- Korniienko, Y. (2019) ‘Що Зеленський каже про економіку: головні обіцянки “Зекоманди”’ [‘what zelensky says about the economy: The main promises of “ZeComanda”’]. Economichna Pravda, May 20. https://www.epravda.com.ua/publications/2019/05/20/647933/.

- Krašovec, A. and Deželan, T. (2019) ‘Slovenia’, in O. Eibl and M. Gregor (eds.), Thirty Years of Political Campaigning in Central and Eastern Europe. Political Campaigning and Communication, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 309–324.

- Kravets, R. and Sarakhman, E. (2019) ‘Володимир Зеленський: 1 квітня – офігенний день для перемоги клоуна’ [‘Volodymyr Zelenskyi: April 1 Is a Great Day for a Clown’s Victory’]. Ukrainska Pravda, January 21. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2019/01/21/7204341/.

- Kuzio, T. (2010) ‘Populism in Ukraine in a comparative European context’, Problems of Post-Communism 57(6): 3–18. doi:10.2753/PPC1075-8216570601.

- Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (2019) ‘Socio-Political Intentions of the Population of Ukraine: January-February 2019.’ February 14. https://www.kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=823&page=1.

- Makarychev, A. (2022) Popular biopolitics and populism at Europe’s eastern margins. Global Populisms: Volume 2, Leiden: Brill.

- Manifesto Project (2022) Corpus & Documents. https://visuals.manifesto-project.wzb.eu/mpdb-shiny/cmp_dashboard_dataset/.

- March, L. (2017) ‘Populism in post-soviet states’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo and P. Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 214–231.

- Mashtaler, O. (2021) ‘The 2019 presidential election in Ukraine: populism, the influence of the media, and the victory of the virtual candidate’, in C. Kohl, B. Christophe, H. Liebau and A. Saupe (eds.), The Politics of Authenticity and Populist Discourses, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 127-160.

- Mudde, C. (2002) The Ideology of the Extreme Right, Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2004) ‘The populist zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition 39(4): 541–563. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

- Mudde, C. (2010) ‘The populist radical right: A pathological normalcy’, West European Politics 33(6): 1167–1186. doi:10.1080/01402382.2010.508901.

- Mudde, C. (2017) ‘Populism: An ideational approach’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo and P. Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–47.

- Onuch, O. and Hale, H. E. (2022) The Zelensky Effect, London: C. Hurst & Co.

- Petrović, N., Raos, V. and Fila, F. (2022) ‘Centrist and radical right populists in central and Eastern Europe: divergent visions of history and the EU’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, doi:10.1080/14782804.2022.2051000.

- Petsinis, V. (2020) ‘Converging or diverging patterns of euroscepticism among political parties in Croatia and Serbia’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies 28(2): 139–152. doi:10.1080/14782804.2019.1686345.

- Petsinis, V. and Wierenga, L. (2021) ‘Report on Radical Right Populism in Estonia and Latvia’ (Working Paper no.7). Horizon 2020 POPREBEL. https://populism-europe.com/poprebel/poprebel-working-papers/.

- Rahat, G. (2022) ‘Party types in the age of personalized politics’, Perspectives on Politics, doi:10.1017/S1537592722000366.

- RBC-Ukraine (2019) ‘Володимир Зеленський: Нам вигідно розпустити Раду, але будемо думати і вчиняти за законом’ [‘Volodymyr Zelensky: It Is Advantageous for Us to Dissolve Verkhovna Rada, but We Will Think and Act According to the Law’]. April 18. https://www.rbc.ua/ukr/news/vladimir-zelenskiy-nam-vygodno-raspustit-1555546435.html.

- Rovira Kaltwasser, C., Taggart, P., Ochoa Espejo, P. and Ostiguy, P. eds (2017) The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rovny, J. and Polk, J. (2020) ‘Still blurry? Economic salience, position and voting for radical right parties in Western Europe’, European Journal of Political Research 59(2): 248–268. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12356.

- Sluha Narodu (2019) ‘Передвиборна програма партії “Слуга Народу”’ [‘Election Program of the “Servant of the People” Party. https://sluga-narodu.com/program/.

- Sluha Narodu (2020) ‘Ідеологія партії’ [‘Ideology of the Party’]. https://sluga-narodu.com/about/ideology/.

- Spirova, М (2021) ‘Bulgaria: political developments and data in 2020’, European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 60(1): 49–57. doi:10.1111/2047-8852.12317.

- Stanley, B. (2017) ‘Populism in central and Eastern Europe’, in C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo and P. Ostiguy (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 140–160.

- Stokes, D. E. (1963) ‘Spatial models of party competition’, American Political Science Review 57(2): 368–377.

- Stoyanov, D. and Lyubenov, M. (2022) ‘Parliamentary election in Bulgaria’, BLUE 2(1): 96–101.

- Taggart, P. (2004) ‘Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe’, Journal of Political Ideologies 9(3): 269–288. doi:10.1080/1356931042000263528.

- Tismaneanu, V. (1996) ‘The leninist debris or waiting for perón.’, East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 10(3): 504–535. doi:10.1177/0888325496010003006.

- Todorov, A. (2018) ‘The failed party system institutionalization’, in M. Lisi (ed.), Party System Change, the European Crisis and the State of Democracy, London; New York: Routledge, pp. 45–62.

- Transparency International (2019) ‘Corruption Perceptions Index.’ https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2019.

- TSN (2019a) Про Донбас, Крим, МВФ і “Слугу народу”. Велике інтерв’ю Володимира Зеленського для ТСН.Тижня’ [‘About Donbas, Crimea, IMF and “Servant of the People”. Volodymyr Zelensky’s big interview for TSN.Tyzhden’]. March 24. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7aJTzevBQ8&ab_channel=%D0%A2%D0%A1%D0%9D.

- TSN (2019b) ‘Право на владу: президентські вибори’ [‘Right to Power: Presidential Elections’]. April 18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwxYGHHjq_I&ab_channel=%D0%A2%D0%A1%D0%9D.

- TSN (2019c) ‘Дебати Зеленського та Порошенка: повний текст виступів та відповідей кандидатів’ [‘Debates between Zelensky and Poroshenko: The full transcript of the candidates’ speeches and replies’]. April 19. https://tsn.ua/politika/debati-zelenskogo-ta-poroshenka-povniy-tekst-vistupiv-ta-vidpovidey-kandidativ-1332675.html.

- Učeň, P. (2007) ‘Parties, populism, and anti-establishment politics in east central Europe’, SAIS Review of International Affairs 27(1): 49–62.

- Viedrov, O. (2022) ‘Back-to-normality outsiders: Zelensky’s technocratic populism, 2019–2021’, East European Politics, doi:10.1080/21599165.2022.2146092.

- Visiting Dmitry Gordon (2018) ‘Vladimir Zelensky. Part 1 of 3.’ December 25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P8OBR9yjgFA&ab_channel=%D0%92%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8F%D1%85%D1%83%D0%93%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0.

- Vox Ukraine (2019) ‘Between Chávez and Merkel: The Political Ideology of Ukraine’s Next President.’ https://voxukraine.org//longreads/compass-ideology/index-en.html.

- Yanchenko, K. (2021) ‘“We will not get another chance if we lose this battle now”: populism on Ukrainian television political talk shows ahead of the presidential election in 2019’, East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 8(2): 275–306.

- Yanchenko, K. (2022) ‘Making sense of populist hyperreality in the post-truth age: evidence from Volodymyr Zelensky’s voters’, Mass Communication and Society, Article 15205436.2022.2105234. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/15205436.2022.2105234.

- Zelensky, V. (2019a) ‘Передвиборча програма кандидата на пост Президента України Володимира Зеленського’ [‘Program of the Candidate for the Post of President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky’]. https://program.ze2019.com/.

- Zelensky, V. (2019b) ‘Інавгураційна промова Президента України Володимира Зеленського’ [‘Inaugural Speech of the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky’]. May 20. https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/inavguracijna-promova-prezidenta-ukrayini-volodimira-zelensk-55489.

- Zulianello, M. (2020) ‘Varieties of populist parties and party systems in Europe: from state-of-the-Art to the application of a novel classification scheme to 66 parties in 33 countries.’, Government and Opposition 55(2): 327–347. doi:10.1017/gov.2019.21.

- Zulianello, M. and Larsen, E. G. (2021) ‘Populist parties in European parliament elections: a new dataset on left, right and valence populism from 1979 to 2019.’, Electoral Studies 71: 102312. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102312.

- Zulianello, M. and Larsen, E. G. (2023) ‘Blurred positions: the ideological ambiguity of valence populist parties’, Party Politics, doi:10.1177/13540688231161205.